Abstract

There is compelling evidence that racial discrimination is a risk factor for illness and disease. But what are health scientists measuring–and what do they think they are measuring–when they include measures of racial discrimination in health research? We synthesize theoretical conceptualizations of racial discrimination in health research and critically assess whether and how these concepts correspond (or not) to widely used measures of racial discrimination. In doing so, we show that while researchers often use terms such as ‘self-reported discrimination’, ‘perceptions of discrimination’, and ‘exposure to discrimination’ interchangeably, these concepts are indeed unique, with each holding a distinct epistemological position and theoretical and methodological capacity to uncover the impact of racial discrimination on health and health disparities. Importantly, we argue that commonly used measures of self-reported or perceived racial discrimination are just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in terms of revealing the ways in which discrimination shapes health inequities. Scientists and practitioners must be cognizant of and intentional in their measurement choices and language, as the framing of these processes will inform policy and intervention efforts aimed at eliminating discrimination.

Keywords: Harassment/discrimination, Racial, ethnic and cultural factors in health, Biological mechanisms of stress

Research on the health effects on racial discrimination has burgeoned over the last 30 years. A 2015 meta-analysis of nearly 300 studies provided convincing evidence of a link between racial discrimination and a range of poor mental and physical health outcomes, including psychological distress, depression, obesity, and hypertension (Y. Paradies et al., 2015). A recent review of 32 systematic and meta-analyses (that together included over 2100 studies) provided similar evidence of a robust association between discrimination and a variety of health outcomes (D. R. Williams et al., 2019). Still, as this area of research inquiry continues to grow, we as researchers need to ask: What are we measuring–or what do we think we are measuring–when we use indicators of ‘racial discrimination’ in health research?

In studies of health, researchers most often measure racial discrimination by asking study participants about their experiences with and perceptions of racial discrimination. Researchers then use respondents’ responses to these questions to capture racial discrimination and assess the links between discrimination and health. Still, while such measures of racial discrimination reflect particular–and important–dimensions of discrimination, these measures do not capture the totality of the effect of racial discrimination on individual and population health. In addition, while studies often use terms such as ‘self-reported discrimination (or experiences of discrimination)’, ‘perceived discrimination’, and ‘exposure to discrimination’ interchangeably, each of these concepts holds a distinct epistemological position and, in turn, possesses unique theoretical and methodological capacity to uncover the impact of racial discrimination on health and health disparities.

This commentary aims to provide theoretical and epistemological clarity to the conceptualization and measurement of racial discrimination in health research. In doing so, we hold that defining and delimiting commonly used measures and terms can assist researchers in more effectively measuring, labelling, examining, and redressing racial discrimination and its effects on health. To start, we draw from a vast interdisciplinary body of scholarly work to define racial discrimination, paying attention to theoretical conceptualizations of racial discrimination and hypothesized mechanisms for understanding how discrimination shapes individual health and population-level health disparities. In doing so, we show that researchers often use terms such as ‘self-reported discrimination’, ‘perceptions of discrimination’, and ‘exposure to discrimination’ interchangeably. In our discussion, however, we argue that these concepts are distinct. Each term holds a unique capacity for theorizing, measuring, and uncovering the role of racial discrimination in shaping individual health and producing health disparities. Finally, we close by arguing that widely used measures of racial discrimination in health research provide a rather limited and narrow view of the role of discrimination in producing population-level health disparities that largely mask the totality of ways that racism, as a system of discrimination, works to pattern population health across domains of social, economic, and political life. By recognizing and acknowledging the utility and limitations of various measures, researchers can better characterize the dimensions of discrimination that they are studying; provide a better match between their theoretical conceptualizations and empirical operationalizations; and, in turn, refine study and intervention designs. Importantly, this paper does not attempt to explicate the health sequalae associated with different forms of racial discrimination, but rather draws attention to how researchers’ language and labels can better match their theories and measures of racial discrimination in ways that can both better specify the role of racial discrimination in shaping health and inform actions aimed at reducing racial discrimination and improving health.

1 |. DEFINING RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

Discrimination is the differential treatment of individuals on the grounds of group or social category membership (Reskin, 2012; D. R. Williams et al., 2019). In 1971 the US Supreme Court expanded the definition of discrimination to include seemingly neutral practices that produce differential impacts (Griggs vs. Duke PowerCo., 1971). The focus of this commentary is on racial discrimination, but discrimination can occur and co-occur along and between multiple axes of social stratification, including, but not limited to, skin colour, gender, sexuality, and religious affiliation. Importantly, racial discrimination stems from and serves to reinforce structural racism. As an ideology and system of domination, racism assigns value and rank to socially constructed racial groups and racialized individuals through the development and propagation of race-based beliefs and attitudes and the differential treatment of racialized persons by both individuals and institutions (Bonilla-Silva, 1997). Racial discrimination can take the form of explicit differential treatment based on race that, as a result, limits a racial group or a member of a racialized group from having equal opportunity or access to goods and resources (Hebl et al., 2002; D. R. Williams & Mohammed, 2009). Racial discrimination can also result from differential treatment based on other factors (e.g., socioeconomic status or criminal justice history) that produces differential effects or impacts by race (National Research Council, 2004; Reskin, 2012). A growing body of research demonstrates that racial discrimination can also take the form of subtle, ambiguous, or ‘lower-intensity’ transgressions (e.g., racist humour or passive aggression) that can produce differential outcomes and further exclude and alienate marginalized and oppressed groups in the workplace and other social contexts (Cortina et al., 2013; Hebl et al., 2002). As Goosby et al. (2018) suggests each of these dimensions of racism are interdependent and simultaneously contribute to health inequities.

There is striking evidence of racial discrimination across social, political, and economic spheres. Although discrimination is often framed as an individual- and interpersonal-level phenomenon, organizations, institutions, and institutional actors play a central role in maintaining structural racism by explicitly and/or covertly legitimizing the unequal distribution of resources, opportunities, and risks by race through both formal and informal discriminatory policies and practices (Ray, 2019). Audit studies provide some of the most widely cited, compelling, and explicit evidence of racial discrimination. For example, the groundbreaking study by the late Devah Pager illustrated that White job applicants with criminal convictions were more likely to receive a callback compared to Black applicants with an otherwise identical resume whose criminal records were clean (Pager et al., 2009). A meta-analysis of audit studies found no change in the levels of discrimination against African Americans over the past 25 years and only modest reductions in discrimination against Latinos (Quillian et al., 2017). Other audit studies reveal racial discrimination in purchasing property, renting apartments, obtaining mortgages, and applying for insurance and credit (Pager & Shepherd, 2008). In the clinician’s office, for example, research finds that physicians are more verbally dominant and engage in less patient-centred communication with Black patients than with White patients (Shen et al., 2018). Taken together, these studies provide clear and convincing evidence of widespread racial discrimination across institutional, organizational, and social spheres.

2 |. MEASURING RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN HEALTH RESEARCH

A variety of empirical tools exists to measure racial discrimination. In health studies, researchers most often rely on survey respondents to relay information about racial discrimination (Krieger, 2012). In general, these studies attempt to ascertain information about direct exposure to racial discrimination by asking respondents about discriminatory experiences (Krieger, 2010). Survey reports of discrimination–which reflect events or instances of unfair treatment that individuals report experiencing–are typically measured through two domains: major life events and daily hassles. Measures of major discrimination attempt to capture acute and observable discriminatory experiences that may impede one’s life chances (e.g., being denied a bank loan, having a promotion withheld; Kessler et al., 1999). Measures of everyday discrimination try to capture the chronicity of more subtle forms of biased and discriminatory interpersonal interactions (D. R. Williams et al., 1997). Unsurprisingly, evidence from survey research shows that people of colour report higher levels of major and everyday discrimination compared to Whites (Boen, 2020; National Public Radio [NPR] et al., 2018). Compared to White individuals, Black, Latino, and Native American individuals report higher levels of discrimination when applying to jobs, in wages and promotions, in interacting with police, and in a doctor’s office or health clinic (Findling et al., 2019; NPR et al., 2018). People of colour also report higher levels of everyday discrimination than Whites, including being treated with less courtesy than others and receiving poorer service than other people at restaurants or stores (Boen, 2020). A large body of the discrimination and health literature provides compelling evidence that survey reports of discrimination is adversely related to a host of mental and physical health outcomes, as well as a variety of health-related behaviours, including health care utilization, adherence to treatment regimens, and engagement in risky coping behaviours like smoking and overeating (D. R. Williams et al., 2019). A burgeoning area of research also shows that people report experiencing an array of more subtle forms of discrimination–sometimes labelled ‘microaggressions’–that increase risks of mental and physical health problems (Ong, 2021; M. T. Williams, 2020; Wong et al., 2014). In general, these studies using survey reports of discrimination typically draw on psychosocial theories of health to show how discrimination functions as a salient chronic and acute stressor in individuals’ lives that affects health both directly and indirectly through a number of psychological, physiological, emotional, and behavioural pathways (D. R. Williams & Mohammed, 2013).

3 |. LABELLING DISCRIMINATION AS ‘SELF-REPORTED’ VS. ‘PERCEIVED’

Despite using similar survey-based measures of racial discrimination in health research, studies vary in their description of what it is they are actually measuring when they include markers of racial discrimination. While the measures derived from survey reports of racial discrimination are largely the same (e.g., markers of everyday and major life discrimination), how scholars label and describe these measures varies. A sweeping read of this literature reveals that scholars waver in their use of the terms ‘self-reported discrimination’, ‘perceived discrimination’, and ‘exposure to discrimination’,–sometimes using them interchangeably. In part, the slippage in language reflects the desire for studies of racial discrimination and health to capture both social exposures and perceptions that affect disclosure, attribution, and response (Krieger, 2010). Further, given that not all instances of racial discrimination are perceived–or even perceivable–and/or disclosed in survey responses, qualifying discrimination as ‘perceived’ or ‘self-reported’ can be useful or necessary. However, we want to emphasize that these constructs–’self-reported discrimination’, ‘perceived discrimination’, and ‘exposure to discrimination’–are not equivalent. Each carries a unique set of assumptions, limitations, and, perhaps unsurprisingly, critics.

Researchers sometimes choose to label responses to survey measures of discrimination–including the widely used major life and everyday discrimination measures–’perceived discrimination’. Still, others argue against the use of ‘perceived’ discrimination in favour of more affirming and objective language, arguing that labelling discrimination as ‘perceived’ legitimizes colour-blind racial ideology and can serve to deny or doubt experiences of discrimination and racism (Banks, 2014). These critics hold that qualifying discrimination as perceived can dismiss and/or minimize the historical and contemporary interactions, events, policies, and institutional practices that have shaped and continue to shape the lived experiences and life chances of racially marginalized groups. As Banks (2014) states, use of ‘perceived discrimination’ allows ‘more room to suggest that the act of discrimination was misunderstood, that it was unintended, or that the perpetrator did not mean to offend’ (p. 312). It follows that labelling discrimination as ‘perceived’ can imply that the experience is imagined and ‘all in one’s head’ taken further, this labelling can disregard the role of structures and institutions in patterning exposure to discrimination. In turn, critics argue, the use of the term ‘perceived discrimination’ places the burden of responsibility on the targets of discrimination to perceive, report, and respond to the experience. The concern is that even the most well-intentioned researcher starting from this epistemological stand–point may be more inclined to suggest individual-level interventions (e.g., stress management techniques) to cope with discrimination-related stressors, while simultaneously undervaluing the target’s experienced reality and ignoring the social structures and institutional arrangements that create those realities. For instance, Black patients report experiencing racial discrimination within different social contexts of the healthcare system (e.g., waiting room, doctor’s office, in scheduling appointments, etc.; Cuevas et al., 2016; Hausmann et al., 2011). While the Institute of Medicine Report, ‘Unequal Treatment’, has provided compelling evidence of bias and differential treatment that support patients’ reports of racial discrimination (Smedley et al., 2003), it still would have been short-sighted for clinicians or social scientists to suggest individual-level interventions to address patients’ perceptions of racial healthcare discrimination in lieu of structural- and institutional-level changes. For these reasons, some researchers prefer to use the term ‘self-reported’ discrimination, a term that can validate and disambiguate a person’s experience with discrimination. In using the term ‘self-reported’, researchers aim to place the burden of responsibility on the actors and social structures discriminating rather than the individual who is the target of discrimination. Nevertheless, both ‘perceived’ and ‘self-reported’ discrimination map themselves at the individual-level and, therefore, are subject to the study of intrapersonal and interpersonal dynamics.

Still, research shows that experiences of discrimination–regardless of whether the terms ‘perceived’ or ‘self-reported’ is used–depend on a host of intrapersonal and interpersonal factors, including immigration status, socioeconomic factors, mood, personality, and past exposure to traumatic events (Assari & Caldwell, 2018; Sechrist et al., 2003, Sutin et al., 2016). This does not negate the occurrence of discrimination nor should it lead researchers to doubt to veracity of people’s reports, but rather suggests that an individual’s interpretation of and response to exposures depend on a variety of factors, including personality, coping strategies, connections with members of one’s ingroup, attitudes, self-esteem, emotional regulation, decision-making, and structural positions within a variety of social systems. Studies show increased stressor-evoked activity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex when individuals are exposed to discriminatory events. Chronic alterations in these regions are known to affect attention allocation, emotional regulation, and decision-making and increase the risk of disease (Lockwood et al., 2018). As such, ‘perceived’ or ‘self-reported’ discrimination–as well as the effects of that discrimination on health–vary depending on past exposure to discrimination and other forms of acute and chronic social stress. The recognition of the importance of perception is not limited to psychology or neurobiology. The stress process model, developed by sociologists including Leonard Pearlin, also acknowledges the critical role of stress perception and appraisal and the mediating and moderating effects of coping resources and social supports in linking social stressors to health (Pearlin et al., 1981). Taken together, this work indicates that perception, indeed, matters in linking discrimination to health. There remains a limited understanding of the intrapersonal and interpersonal factors that influence perception or self-reports of discrimination. Future research could strengthen our understanding of how people process this social stressor.

Though less studied in health research, there is also a large and growing number of White Americans reporting anti-White discrimination (NPR et al., 2018; Norton & Sommers, 2011). Lower- and moderate-income Whites are especially likely to report that White Americans face racial discrimination, particularly when applying for a job, raise or promotion, or in the college-admissions process (NPR et al., 2018). Importantly, these reports of discrimination are inconsistent with the plethora of evidence showing tremendous White advantage across social, economic, and political spheres. So how do we reconcile this? The lack of evidence of anti-White discrimination suggests that these reports reflect the group’s perceptions of threat, including their fears of and anxieties about the nation’s changing demographic composition, rather than any experience of institutional oppression or exclusion (Versey et al., 2019). Decades of scholarship document how Whites have garnered tremendous social and material benefits through formal and informal, explicit and more covert discriminatory institutional policies and practices that have favoured Whites and excluded people of colour (Mendez et al., 2014; Roithmayr, 2014; Rothstein, 2017). To suggest that anti-White discrimination is indicative of systemic anti-White racism defies scientific evidence and logic. Yet, the perception of discrimination by Whites may still be consequential. These perceptions serve as psychosocial stressors that can have deleterious health effects on individuals (Cuevas & Williams, 2018; D. R. Williams & Mohammed, 2009). These perceptions may shape out-group behaviours in important–and potentially dangerous–ways that are relevant to population health. As such, research examining anti-White discrimination can lay bare the geopolitical, social, and economic circumstances that cultivate perceptions of anti-White discrimination among Whites.

Further, knowledge deriving from multidisciplinary studies of stress mediators and moderators can augment our understanding of how discrimination contributes to existing health disparities through neurobiological, psychological, and social pathways that shape perception. In these ways, the term ‘perceived discrimination’ may be applicable, as the epistemological underpinning of the term is that the meanings of social truths change according to social context and that past and contemporary social contexts can affect future interpretations of events. Individual-level interventions within this scope (e.g., promoting positive racial identity attitudes, elevating moods, improving decision-making) may not reduce perceptions or reports of discrimination but may help buffer the effects of discrimination on health. Indeed, effectual individual-level interventions have been developed to help individuals cope with the stress of racial discriminatory encounters. For example, the Engaging, Managing, and Bonding through Race (EMBRace) intervention aims at mitigating the mental and physical effects of racial discrimination exposure by bolstering racial socialization in Black children through the promotion of racial self-efficacy and self-worth, strengthening family bonding and relationships, and teaching stress-management techniques (e.g., journaling and relaxation methods; Anderson et al., 2019). Values affirmation interventions have shown effectiveness in tempering the deleterious health effects of discriminatory experiences by reinforcing an individual’s self-worth and enhancing their psychological resilience (Lewis et al., 2015). Together with structural interventions aimed at reducing discrimination, this line of research may provide insights into the development of interventions that identify vulnerable populations and mitigate the effects of discrimination exposure on health.

4 |. DISCRIMINATION OFTEN REMAINS LARGELY HIDDEN FROM INDIVIDUAL VIEW

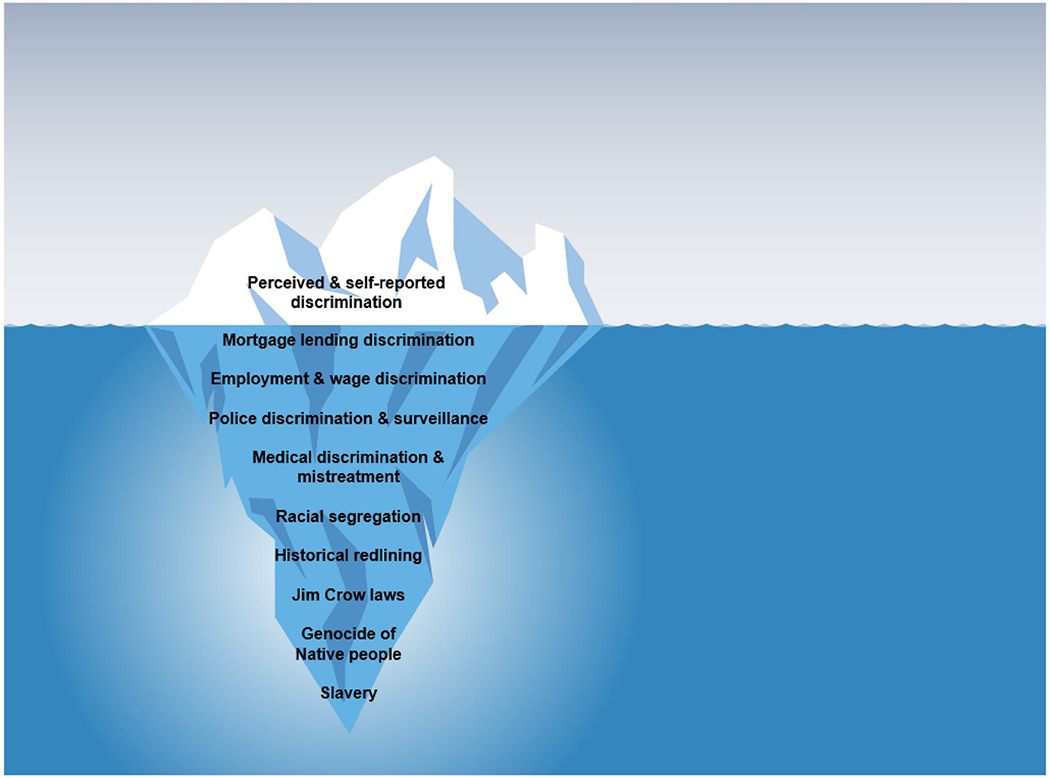

Importantly, it is essential for scholars, researchers, and practitioners to recognize that measures of self-reported and perceived discrimination do not comprehensively measure exposure to racial discrimination, specially, or racism, more broadly, nor do these measures identify the specific perpetrators or mechanisms of discrimination, which is essential from a policy and intervention perspective. For one, survey measures ask about discriminatory experiences across a limited set of domains and are thus unable to capture the full range of discriminatory experiences individuals and groups encounter. Additionally, respondent reports of racial discrimination fail to capture the times and places when discrimination occurs but is hidden, covert, or outside of the respondents’ view. As Figure 1 illustrates, widely used measures of self-reported and perceived discrimination tend to preference interpersonal discrimination while largely ignoring more macro-level forms of discrimination, including discrimination in the institutional, cultural, and structural spheres. Racial discrimination can be explicit, but it is also covert and largely invisible, operating in nuanced ways to produce differential treatment and outcomes within and between racialized populations. For example, individuals may not always be able to know that an employer or lender discriminated against them. Y. C. Paradies (2006) suggests that these and other systemic forms of racism are frequently not perceived by individuals who experience these phenomena. Further, discrimination that occurred in the past also has consequences for the present and future, shaping individuals’ lives and well-being and perpetuating and exacerbating racial inequality in health and other outcomes in ways that may not be easily perceptible to individuals. The systematic erasure of Native Americans through genocidal and colonial policies and enduring invalidation, invisibilization, and assault on tribal sovereignty and human rights are key drivers of existing morbidity and mortality disparities in American Indian and Alaska Native populations (Evans-Campbell, 2008; Findling et al., 2019; Glauner, 2001; Indian Health Service, 2013; Leavitt et al., 2015). Redlining practices by the Home Owner’s Lending Corporation, the racially restrictive lending policies of the Federal Housing Authority in the years following World War II, and felon disenfranchisement laws–which were designed in part to erode Black voting power–are also a few examples of historic discrimination that has cotemporary consequences on the socioeconomic standing and health of Black Americans (Small & Pager, 2020). For instance, studies have used the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act database to develop indices of racial bias in mortgage lending and redlining and found that racial bias in mortgage lending, in particular, was associated with poorer colorectal and breast cancer survival among Black women, but not among White women (Beyer et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2017). Racialized disparities in policing and incarceration–which stem from structural discrimination across institutional spheres–are linked to racial inequities in health and mortality (Boen, 2020; Edwards et al., 2019; Sewell, 2017) in ways that do not depend on individual reports or perceptions of discrimination. In these ways, responses to survey questions of racial discrimination are just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in terms of revealing the ways in which discrimination shapes outcomes like health and how we design interventions.

FIGURE 1.

Depiction of self-reported/perceived discrimination being a small, noticeable part of a much larger, more complex system of racism

In developing strategies for redressing the impacts of racial discrimination on population health, we can draw parallels with the three levels of disease prevention strategies: primary prevention, secondary prevention, and tertiary prevention. Primary prevention strategies seek to limit the development of a disease or disability in healthy individuals. Correspondingly, structural-level interventions–including legal, policy, and institutional changes–can be used as primary prevention strategies to shift social norms, alter institutional structures and organizational practices, and, ultimately, reduce exposure to risk factors and ensure population-wide health and protection. Primary prevention strategies targeting structural racism and racial discrimination operate similarly in that they seek to protect and improve the health and social well-being of historically marginalized and oppressed groups through large-scale structural-level initiatives. These initiatives can aim to eliminate existing discriminatory policies and practices, redress the harms caused by historical forms of discrimination, dispel cultural racism, and ultimately uplift the social, economic, and environmental conditions of the population by tending specifically to the needs of racially marginalized groups. Importantly, studies on the health impacts of structural racism can inform policy and intervention efforts in pursuit of these goals. Secondary prevention strategies aim to identify at-risk populations and implement strategies that can help mitigate the onset of sickness and disease. While researchers work to execute effective primary prevention interventions aimed at eliminating structural racism and pursuing racial equity, it is also imperative to identify those who are currently at high-risk of discrimination and implement targeted intervention efforts to reduce the burden of these risks. A secondary prevention strategy targeting racial discrimination could focus on fostering positive racial identity and self-esteem among children of racially marginalized groups. Tertiary prevention strategies seek to help individuals manage disease to slow or halt disease progression. In the context of discrimination, this could include interventions that help individuals cope with the stress of racial discrimination. Both macro-level and survey studies of racial discrimination can inform both secondary and tertiary prevention efforts by identifying at-risk or vulnerable groups and develop tailored intervention to prevent, decelerate, or stop the progression of disease. While developing interventions aimed at dismantling structural racism is the best prevention strategy, a multi-pronged and coordinated approach is needed to comprehensively address the multiple pathways linking discrimination to health.

5 |. CONCLUSION

It is difficult to firmly determine or parameterize the associations between self-reported or perceived discrimination and actual exposure to discrimination. Instead, scholars must acknowledge the limitations of measures of discrimination, both self-reported experiences and perceptions, in reflecting how racism–as a system of racial domination and oppression–differentially shapes access to opportunities, resources, and risks in both explicit and more covert ways. Responses to questions about discrimination experiences or perceptions, laboratory experiments involving exposure to racially hostile stimuli, and field experiments like audit studies each provides a glimpse into the role of discrimination in producing racial health inequities, but none is sufficient to fully capture what is a complex system of race discrimination, as shown in Figure 1 (Reskin, 2012). All measures of self-report discrimination, perceived discrimination, or discrimination within specific institutions or domains of life produce gross underestimates of the totality of ways that discrimination produces racial health inequities.

Racial categories (including White, Black, Latino, etc.) are socially and politically constructed–created and used to justify and maintain racism–which means that the racial disparities observed across domains of life reflect differential exposures to social, economic, and political conditions–as well as differential effects of exposures–by race. In these ways, racial disparities in health reflect not only individuals’ differential exposure to conditions across the life course, but also the historical and intergenerational transmission of racial advantage and disadvantage. Discrimination is not limited to particular points in time or experiences within single institutions or domains. Instead, discrimination accumulates within and between domains and across individual life spans, generations, and historical time to produce racial health disparities. As such, documentation of racial disparities–in and of itself–provides evidence of racism and discrimination, even if indirectly (Krieger, 2010).

Our goal is not to discount previous studies of discrimination and health that have used these terms interchangeably (we ourselves have committed these actions) or to give preference to one set of measures or terms over another. Rather, we want to draw much needed attention to the epistemological assumptions, meanings, and limitations underlying these terms and concepts. Each approach to measuring discrimination holds great utility in illuminating the impact of discrimination on health and health disparities. Each offers valuable insights into how discrimination operates as a psychosocial stressor and material mechanism underlying racial disparities in health. Still, no approach to measuring discrimination can fully capture how discrimination works to produce racial disparities in health across time, space, and domains. Scientists and practitioners must be cognizant of and intentional in their measurement choices and language, as our framing of these processes will inform policy and intervention efforts aimed at eliminating discrimination.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No data were generated or analysed for this commentary.

REFERENCES

- Anderson RE, McKenny MC, & Stevenson HC (2019). EMBRace: Developing a racial socialization intervention to reduce racial stress and enhance racial coping among black parents and adolescents. Family Process, 58(1), 53–67. 10.1111/famp.12412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assari S, & Caldwell C (2018). Social determinants of perceived discrimination among black youth: Intersection of ethnicity and gender. Children, 5(2), 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks KH (2014). “Perceived” discrimination as an example of color-blind racial ideology’s influence on psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer KMM, Zhou Y, Matthews K, Bemanian A, Laud PW, & Nattinger AB (2016). New spatially continuous indices of redlining and racial bias in mortgage lending: Links to survival after breast cancer diagnosis and implications for health disparities research. Health & Place, 40, 34–43. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boen C (2020). Death by a thousand cuts: Stress exposure and black–white disparities in physiological functioning in late life. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 75(9), 1937–1950. 10.1093/geronb/gbz068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boen CE (2020). Criminal justice contacts and psychophysiological functioning in early adulthood: Health inequality in the carceral state. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 61(3), 290–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E (1997). Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review, 62, 465–480. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina LM, Kabat-Farr D, Leskinen EA, Huerta M, & Magley VJ (2013). Selective incivility as modern discrimination in organizations. Journal of Management, 39(6), 1579–1605. [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, O’Brien K, & Saha S (2016). African American experiences in healthcare: “I always feel like I’m getting skipped over”. Health Psychology, 35(9), 987–995. 10.1037/hea0000368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas AG, & Williams DR (2018). Perceived discrimination and health: Integrative findings. In The Oxford Handbook of integrative health science. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards F, Lee H, & Esposito M (2019). Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Vol. 116, No. 34, pp. 16793–16798). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T (2008). Historical trauma in American Indian/native Alaska communities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(3), 316–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findling MG, Casey LS, Fryberg SA, Hafner S, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Sayde JM, & Miller C (2019). Discrimination in the United States: Experiences of native Americans. Health Services Research, 54, 1431–1441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauner L (2001). The need for accountability and reparations: 1830-1976 the United States government’s role in the promotion, implementation, and execution of the crime of genocide against native Americans. DePaul Law Review, 51, 911. [Google Scholar]

- Goosby BJ, Cheadle JE, & Mitchell C (2018). Stress-related biosocial mechanisms of discrimination and African American health inequities. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 319–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann LRM, Hannon MJ, Kresevic DM, Hanusa BH, Kwoh CK, & Ibrahim SA (2011). Impact of perceived discrimination in healthcare on patient-provider communication. Medical Care, 49(7), 626–633. psyh 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318215d93c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebl MR, Foster JB, Mannix LM, & Dovidio JF (2002). Formal and interpersonal discrimination: A field study of bias toward homosexual applicants. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(6), 815–825. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. (2013, January 1). Disparities | Fact Sheets. News room. Retrieved from https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/ [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, & Williams DR (1999). The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 40(3), 208–230. 10.2307/2676349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2010). 11 the science and epidemiology of racism and health: Racial/ethnic categories, biological expressions of racism, and the embodiment of inequality–an ecosocial perspective. WHAT’S the use OF race?, p. 225. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger N (2012). Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: An ecosocial approach. American Journal of Public Health, 102(5), 936–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt PA, Covarrubias R, Perez YA, & Fryberg SA (2015). “Frozen in time”: The impact of native American media representations on identity and self-understanding. Journal of Social Issues, 71(1), 39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis TT, Cogburn CD, & Williams DR (2015). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11(1), 407–440. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood KG, Marsland AL, Matthews KA, & Gianaros PJ (2018). Perceived discrimination and cardiovascular health disparities: A multisystem review and health neuroscience perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1428(1), 170–207. 10.1111/nyas.13939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez DD, Hogan VK, & Culhane JF (2014). Institutional racism, neighborhood factors, stress, and preterm birth. Ethnicity and Health, 19(5), 479–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Public Radio (NPR). (2018). The robert wood Johnson foundation, & Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health. Discrimination in America: Final Summary. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (2004). Measuring racial discrimination. National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norton MI, & Sommers SR (2011). Whites see racism as a zero-sum game that they are now losing. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(3), 215–218. 10.1177/1745691611406922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD (2021). Racial microaggressions and daily experience: A conceptual framework for linking process, person, and context. Perspectives on Psychological Science. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, Bonikowski B, & Western B (2009). Discrimination in a low wage labor market. American Sociological Review, 74(5), 777–799. 10.1177/000312240907400505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager D, & Shepherd H (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 181–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies YC (2006). Defining, conceptualizing and characterizing racism in health research. Critical Public Health, 16(2), 143–157. 10.1080/09581590600828881 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M, & Gee G (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One, 10(9), e0138511. 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, & Mullan JT (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L, Pager D, Hexel O, & Midtbøen AH (2017). Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 201706255. 10.1073/pnas.1706255114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray V (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26–53. [Google Scholar]

- Reskin B (2012). The race discrimination system. Annual Review of Sociology, 38(1), 17–35. 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roithmayr D (2014). Reproducing racism: How everyday choices lock in white advantage. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein R (2017). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. Liveright Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sechrist GB, Swim JK, & Mark MM (2003). Mood as information in making attributions to discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(4), 524–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sewell AA (2017). The illness associations of police violence: Differential relationships by ethnoracial composition. Sociological Forum, 32, 975–997. [Google Scholar]

- Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, Hernandez MH, Jewell ST, Matsoukas K, & Bylund CL (2018). The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: A systematic review of the literature. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(1), 117–140. 10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small ML, & Pager D (2020). Sociological perspectives on racial discrimination. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(2), 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, & Nelson AR (2003). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version). National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, & Terracciano A (2016). Perceived discrimination and personality development in adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 52(1), 155–163. 10.1037/dev0000069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versey HS, Cogburn CC, Wilkins CL, & Joseph N (2019). Appropriated racial oppression: Implications for mental health in Whites and Blacks. Social Science & Medicine, 230, 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams MT (2020). Microaggressions: Clarification, evidence, and impact. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, & Vu C (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Services Research, 54, 1374–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2009). Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 32(1), 20. 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Mohammed SA (2013). Racism and health I: Pathways and scientific evidence. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8). 10.1177/0002764213487340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yan Yu, Jackson JS, & Anderson NB (1997). Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology, 2(3), 335–351. 10.1177/135910539700200305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G, Derthick AO, David EJR, Saw A, & Okazaki S (2014). The what, the why, and the how: A review of racial microaggressions research in psychology. Race Soc Probl, 6(2), 181–200. 10.1007/s12552-013-9107-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Bemanian A, & Beyer KMM (2017). Housing discrimination, residential racial segregation, and colorectal cancer survival in southeastern Wisconsin. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 26(4), 561–568. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were generated or analysed for this commentary.