Abstract

A seminested PCR assay, based on the amplification of the pneumococcal pbp1A gene, was developed for the detection of penicillin resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. The assay was able to differentiate between intermediate (MICs = 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml) and higher-level (MICs = ≥1 μg/ml) resistance. Two species-specific primers, 1A-1 and 1A-2, which amplified a 1,043-bp region of the pbp1A penicillin-binding region, were used for pneumococcal detection. Two resistance primers, 1A-R1 and 1A-R2, were designed to bind to altered areas of the pbp1A gene which, together with the downstream primer 1A-2, amplify DNA from isolates with penicillin MICs of ≥0.25 and ≥1 μg/ml, respectively. A total of 183 clinical isolates were tested with the pbp1A assay. For 98.3% (180 of 183) of these isolates, the PCR results obtained were in agreement with the MIC data. The positive and negative predictive values of the assay were 100 and 91%, respectively, for detecting strains for which the MICs were ≥0.25 μg/ml and were both 100% for strains for which the MICs were ≥1 μg/ml.

The targets for β-lactam antibiotics are cell wall-synthesizing enzymes known as penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). β-Lactam resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae is due to extensive alterations in their PBPs that lead to decreased affinities for these drugs. Pneumococci produce five high-molecular-weight PBPs (1A, 1B, 2A, 2B, and 2X) and the low-molecular-weight PBP 3 (5). Resistance to penicillin has been shown to involve four of the five high-molecular-weight PBPs, namely, 1A, 2A, 2B, and 2X (5, 9, 10, 12). Studies have shown that alterations in PBP 2X result in low-level penicillin resistance, whereas high-level penicillin resistance requires alterations in PBPs 2B and 1A (2, 21). A recent study by Smith and Klugman (22) demonstrates the significant role PBP 1A plays in mediating high-level penicillin resistance. They showed that in isolates for which penicillin MICs were 0.125 to 1 μg/ml, nucleotide and amino acid alterations were confined to an area surrounding the Lys-557–Thr–Gly motif. As the MICs increased above 1 μg/ml, the number of nucleotide and amino acid alterations also increased, such that the entire penicillin-binding domain was included. Only high-level resistant isolates (MICs of ≥2 μg/ml) were found to have alterations within the area of the Ser-370–Thr–Met–Lys and Ser-428–Arg–Asn motifs of pbp1A.

Due to the high morbidity and mortality associated with meningitis, early implementation of appropriate therapy requires prompt identification of the pathogen and, more importantly, its antimicrobial susceptibility pattern. Presently, susceptibility testing can only be carried out once an organism has been cultured, and this requires an additional 24 h before a result is available. Empirical combination therapy of a cephalosporin plus vancomycin is often the only choice that many clinicians have and yet one would like to avoid the extensive and sometimes inappropriate use of drugs such as vancomycin (7). Due to the development of molecular techniques, it is now possible to detect pathogens in clinical specimens by using PCR (6, 11, 20). The PCR is a rapid, specific, and sensitive method, and since it does not depend on the presence of viable organisms, it may be applicable in cases of prior antibiotic treatment. In our previous study we used a seminested PCR strategy, one based on the amplification of the pneumococcal pbp2B gene, to detect intermediately penicillin resistant pneumococci (MICs of ≥0.125 μg/ml) in cerebrospinal fluid specimens (6). Our present study describes an assay, based on amplification of the pbp1A gene, that is able to differentiate between isolates with intermediate resistance (MICs of 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml) and those with higher-level penicillin resistance (MICs of ≥1 μg/ml) by using a similar PCR strategy. Two species-specific primers were designed to bind to and amplify the pneumococcal pbp1A gene. Two additional internal primers were designed to bind to altered areas of the pbp1A gene, as identified in penicillin-resistant pneumococci isolated worldwide (1, 12, 16, 22). These altered areas occur internal to the species-specific primer binding sites. Together with the downstream primer, the upstream resistance primers amplify resistance products.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Clinical isolates were obtained from the South African Institute for Medical Research, a reference center for pneumococci in South Africa. A total of 159 South African S. pneumoniae strains were used in the study, together with R6 (an unencapsulated laboratory strain), S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619, and 24 S. pneumoniae strains from France, Hungary, China, and The United States. Penicillin MICs were determined by the agar dilution method in Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 3% lysed horse blood (17). Organisms were routinely cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 on Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco) supplemented with 5% lysed horse blood. Sixteen nonpneumococcal organisms were included in the study for specificity testing. These were Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, Streptococcus pyogenes, Streptococcus faecium, Streptococcus sanguis, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus milleri, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus bovis, Streptococcus mitior, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, Listeria monocytogenes, and Moraxella catarrhalis. These organisms were isolated from clinical specimens and identified by standard laboratory methods (13).

PCR primers.

The sequences of primers used in the amplification of the pbp1A gene are shown in Table 1. The sequences of the pbp2B gene primers are described by du Plessis et al. (6).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers used in the amplification of the pbp1A gene

| Primera | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Position in pbp1A geneb | Product length (bp) after amplification with downstream primer 1A-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A-R1 | AAGAACACTGGTTATGTA | 2662–2679 | 224 |

| 1A-R2 | AGCATGCATTATGCAAAC | 2317–2334 | 569 |

| 1A-1 | ACAAATGTAGACCAAGAAGCTCAA | 1843–1866 | 1,043 |

| 1A-2 | TACGAATTCTCCATTTCTGTAGAG | 2863–2886 |

Primers 1A-1 and 1A-2 are specific for pneumococci. Primers 1A-R1 and 1A-R2 specifically amplify pneumococcal isolates for which the penicillin MICs are ≥0.25 and ≥1 μg/ml, respectively.

According to the sequence data of Smith and Klugman (22).

Preparation of genomic DNA.

Pure genomic DNA was extracted from pneumococcal strains by previously described methods (21). For nonpneumococcal organisms, a swab of cells from a plate of growth was resuspended in 50 μl of H2O and boiled for 10 min, and after centrifugation a supernatant containing a crude preparation of DNA was obtained.

PCR conditions for S. pneumoniae.

A seminested PCR strategy was used. Each assay required two reactions containing primers 1A-1, 1A-2, and 1A-R1 and primers 1A-1, 1A-2, and 1A-R2, respectively. All PCR amplifications were carried out with a Hybaid Omnigene Thermal Cycler (Middlesex, United Kingdom). The 50-μl reaction mixture consisted of 50 ng of genomic DNA, 2 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleotide triphosphates (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), a 1.0 μM concentration of each primer, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.). The PCR process included an initial 3-min incubation at 93°C, followed by 30 cycles of 93°C for 1 min, 50°C (when primer 1A-R1 was included) or 55°C (when primer 1A-R2 was included) for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min. A 5-min extension at 72°C was included at the end of the final cycle. Amplified DNA fragments were analyzed by gel electrophoresis with 2% agarose.

PCR conditions for nonpneumococcal organisms.

Conditions were exactly as described above except that 3 μl of boiled cells was used per PCR as opposed to genomic DNA. S. pneumoniae ATCC 49619 and R6 were used as positive controls. These organisms were further tested with previously described universal 16S rRNA primers (8) to ensure that there were no false-negatives results.

DNA sequencing.

Pneumococcal pbp1A and pbp2B genes were amplified by PCR, with the forward primer biotinylated at its 5′ end. Amplified PCR products were cleaned by using a 0.6 volume of 20% polyethylene glycol–2.5 M NaCl as previously described (18). The biotinylated and nonbiotinylated strands were separated with streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Boehringer Mannheim). The DNA strands were sequenced by using the Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (U.S. Biochemicals, Cleveland, Ohio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

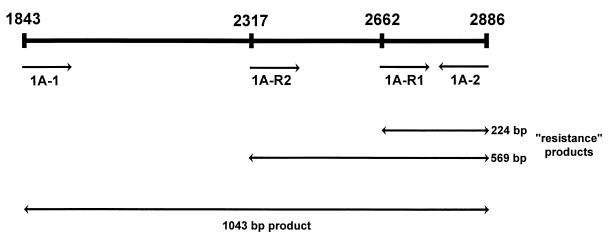

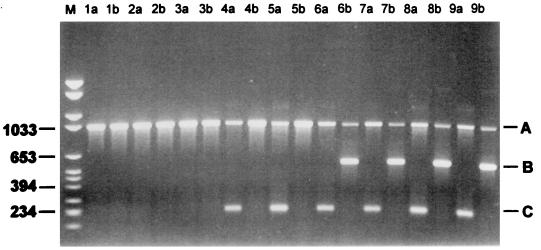

The design of the resistance primers used in the present pbp1A seminested PCR assay is based on the published sequence data of Smith and Klugman (22). They showed that in the pneumococcal pbp1A gene, nucleotide alterations resulting in four amino acid substitutions (Thr-574→Asn, Ser-575→Thr, Gln-576→Gly, and Phe-577→Tyr) are common to all penicillin-resistant isolates for which the MICs are ≥0.25 μg/ml. The design of resistance primer 1A-R1 (Table 1) is based on these four consecutive mutations. In principle, this primer will anneal to the genomic DNA and result in the synthesis of an amplification product only for resistant isolates for which the MICs are ≥0.25 μg/ml. Resistance primer 1A-R2 (Table 1) is designed to bind to an area slightly downstream of the Ser-428–Arg–Asn motif. Mutations in this area of the pbp1A gene, resulting in the amino acid substitutions Ile-459→Met and Ser-462→Ala, only occur in isolates for which the MICs are ≥1 μg/ml (22); therefore, amplification with this primer should only occur for higher-level resistant isolates (MICs of ≥1 μg/ml). The positions of primer binding to the pbp1A gene are indicated in Fig. 1. A universal reverse primer 1A-2 amplifies, together with the forward primers 1A-R1 and 1A-R2, to generate 224- and 569-bp resistance products, respectively. The forward primer 1A-1 and the universal reverse primer 1A-2 are pneumococcus specific and generate a 1,043-bp product. To determine the effectiveness of this pbp1A assay in identifying penicillin-resistant pneumococci, 183 pneumococcal isolates, with penicillin MICs ranging from 0.03 to 16 μg/ml, were analyzed. The results are summarized in Tables 2 and 3. An excellent correlation was found between PCR products and the MIC data. For 98.3% (180 of 183) of the isolates tested, the PCR results obtained were in agreement with the MIC data. The results in Table 2 and Fig. 2 indicate that among those isolates for which the penicillin MICs are 0.03 to 0.06 μg/ml, only one PCR product was observed, the 1,043-bp species-specific product. No resistance products were observed. Isolates with intermediate levels of resistance (MICs of 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml) produce an additional amplification product of 224-bp resulting from amplification with primers 1A-R1 and 1A-2, whereas isolates for which the MICs were ≥1 μg/ml produce two additional amplification products of 244-bp (primers 1A-R1 and 1A-2) and 569-bp (primers 1A-R2 and 1A-2). The 569-bp product is thus indicative of higher-level penicillin resistance. Isolates for which the MICs are 0.125 μg/ml are considered “borderline” and 50% of the time are PCR positive for the assay. For comparative purposes, the 183 isolates were also analyzed with our previously described pbp2B assay (6). According to this pbp2B assay, 96.7% (177 of 183) of the PCR results were in agreement with the MIC data.

FIG. 1.

Primer binding sites in the S. pneumoniae pbp1A gene. 1A-1 and 1A-2 represent pneumococcal specific primers. 1A-R1 and 1A-R2 represent resistance primers which amplify DNA from isolates with penicillin MICs of ≥0.25 and ≥1 μg/ml, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Results showing correlation between the pbp1A PCR assay and penicillin MICs

| Penicillin MIC (μg/ml) | No. of isolates | PCR productsa

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A-R1+1A-2 | 1A-R2+1A-2 | ||

| 0.03 | 24 | − | − |

| 0.06 | 6 | − | − |

| 0.125 | 6 | − | − |

| 0.125 | 6 | + | − |

| 0.25 | 51 | + | − |

| 0.5 | 20 | + | − |

| 1 | 8 | + | + |

| 2 | 24 | + | + |

| 4 | 22 | + | + |

| 8 | 4 | + | + |

| 16 | 6 | + | + |

+, PCR product observed; −, PCR product not observed.

TABLE 3.

Pneumococcal isolates showing discrepant pbp1A and pbp2B results compared with their MIC dataa

| Isolate no. | Penicillin MIC (μg/ml) |

pbp2B

|

pbp1A

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCR (resistance) productb | Nucleotide sequence data compared to strain R6c | PCR (resistance) product

|

Nucleotide sequence data compared to strain R6c | |||

| 1A-R1 | 1A-R2 | |||||

| 29 | 0.125 | − | Identical to R6 | + | − | Mutations |

| 36 | 0.25 | − | Identical to R6 | + | − | Mutations |

| 89 | 0.125 | − | Identical to R6 | + | − | Mutations |

| 129 | 0.5 | − | Mutations | − | − | Mutations |

| 139 | 0.12 | − | Mutations | − | − | Mutations |

| 143 | 0.25 | − | Identical to R6 | − | − | Mutations |

Isolates were sequenced through the penicillin-binding domain encoding regions.

The pbp2B PCR assay was done as previously described by du Plessis et al. (6).

R6 is a penicillin-susceptible strain.

FIG. 2.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR amplified fragments of the pbp1A gene from S. pneumoniae. Lane M, molecular weight marker. Primer combinations are as follows: 1A-R1+1A-1+1A-2 (lanes a); 1A-R2+1A-1+1A-2 (lanes b). The penicillin MICs for the isolates are as follows: 0.03 μg/ml (lanes 1), 0.06 μg/ml (lanes 2), 0.125 μg/ml (lanes 3), 0.25 μg/ml (lanes 4), 0.5 μg/ml (lanes 5), 1 μg/ml (lanes 6), 2 μg/ml (lanes 7), 4 μg/ml (lanes 8), and 8 μg/ml (lanes 9). A, a 1,043-bp product arising from amplification with primers 1A-1 and 1A-2; B, a 569-bp product arising from amplification with primers 1A-R2 and 1A-2; C, a 224-bp product arising from amplification with primers 1A-R1 and 1A-2.

Table 3 shows those 6 of 183 (3.3%) isolates that exhibited discrepant PCR results when compared with their MIC data. This table shows the results obtained for the present pbp1A assay and our previously described pbp2B assay (6). For these six isolates, the penicillin-binding domains of pbp1A and pbp2B were also sequenced and compared to that of the penicillin-susceptible strain R6. Table 4 shows the amino acid substitutions present in the penicillin-binding domains of the pbp1A and pbp2B genes of these isolates. Isolates 29, 36, and 89 revealed MICs of 0.125 to 0.25 μg/ml; therefore, positive PCRs were expected for both their pbp1A and pbp2B genes. However, only the pbp1A assay gave resistance amplification products. The negative pbp2B assay was supported by DNA sequencing, which revealed an unaltered gene. These results were unexpected, considering that previous data have shown that the development of penicillin resistance occurs in a stepwise manner with an alteration of pbp2B occurring before an alteration of pbp1A (15, 22, 23). This uncommon situation was found at the intermediate level of resistance. At a higher level of penicillin resistance an altered pbp2B would probably be required. For isolates 129, 139, and 143 (MICs of 0.125 to 0.5 μg/ml), both PCR assays failed in the detection of penicillin resistance. Sequencing of the genes revealed altered areas with mutations not matching our resistance primers. These results indicate that 3.6% (3 of 83) of the intermediate isolates may be misclassified as susceptible when this PCR assay is used. A successful PCR assay for resistance would therefore require a continuous monitoring of new sequence data from resistant isolates which could lead to the addition of new resistance primers. Coffey and coworkers showed that a single amino acid substitution (Thr-550 by Ala) in PBP 2X decreased the penicillin MIC for a pneumococcal isolate from 4 to 0.25 μg/ml (4). This amino acid substitution also increased the cefotaxime MIC for the isolate from 8 to 32 μg/ml. This occurred in the background of similarly altered pbp1A genes. Therefore, in this situation of high-level cephalosporin resistance and intermediate penicillin resistance, our pbp1A assay, with primer 1A-R2, could erroneously indicate higher-level penicillin resistance. The positive predictive and negative predictive values for our PBP 1A assay were 100 and 91%, respectively, for detecting strains for which the MICs are ≥0.25 μg/ml and were both 100% for strains for which the MICs are ≥1 μg/ml.

TABLE 4.

Amino acid substitutions in the penicillin-binding domains of the PBP 1A and 2B proteins of isolates 29, 36, 89, 129, 139, and 143

| Isolate no(s) | Amino acid substitutions in:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PBP 1A | PBP 2B | |

| 29, 36, 89 | Asp-533→Glu | None |

| Thr-574→Glu | ||

| Gln-576→Gly | ||

| Phe-577→Tyr | ||

| Leu-583→Arg | ||

| Leu-606→Ile | ||

| Val-607→Met | ||

| Asn-609→Asp | ||

| 129, 139 | Asn-443→Asp | Thr-252→Ala |

| Thr-447→Asn | Glu-282→Gly | |

| Ser-458→His | Thr-295→Ser | |

| Ile-459→Met | Glu-312→Asp | |

| Asp-473→Asn | ||

| Lys-475→Gln | ||

| Tyr-487→Phe | ||

| Thr-495→Ile | ||

| Tyr-497→His | ||

| His-503→Asn | ||

| Val-505→Ile | ||

| Asn-517→Asp | ||

| Val-518→Ala | ||

| Asp-533→Glu | ||

| 143 | Glu-388→Asp | None |

| Ser-540→Thr | ||

The specificity of the pbp1A assay was demonstrated by its inability to amplify DNAs from 14 of 16 nonpneumococcal organisms. A 333-bp 16S rRNA amplification product was detected in all of these organisms, indicating that the absence of a pneumococcus-specific product was due to absence of the pbp1A and pbp2B genes rather than to an inadequate genomic DNA supply. Amplification products identical to the 1,043-bp pneumococcus-specific product were detected in two of the organisms tested, namely, S. sanguis and S. mitior. These amplification products were weak compared to the pneumococcal products (data not shown). Previous work has demonstrated that the viridans group streptococci, in particular S. sanguis, have the potential to transfer resistance genes to pneumococci and vice versa (3, 19). We do not expect the viridans group streptococci to cause significant misdiagnosis in the setting of meningitis.

In the PCR-based diagnosis of penicillin-resistant pneumococci, the present pbp1A assay is an improvement on our previously described pbp2B assay. Two resistance primers are used in the pbp1A assay compared to the four used in the pbp2B assay. In addition, the pbp1A assay can also differentiate between intermediate (MICs of 0.25 to 0.5 μg/ml) and higher-level (MICs of ≥1 μg/ml) resistance. PCR-based diagnosis of penicillin resistance is complicated by the participation of multiple PBPs in the development of resistance. Further research will determine which PBPs will serve best as a target in a PCR-based diagnostic kit aimed at the identification of all pneumococci with resistance to penicillin and other β-lactams.

REFERENCES

- 1.Asahi Y, Ubukata K. Association of a Thr-371 substitution in a conserved amino acid motif of penicillin-binding protein 1A with penicillin resistance of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;42:2267–2273. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcus V A, Ghanekar K, Yeo M, Coffey T J, Dowson C G. Genetics of high-level penicillin resistance in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;126:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chalkley L J, Koornhof H J. Intra- and interspecific transformation of S. pneumoniae to penicillin resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;26:21–28. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffey T J, Daniels M, McDougal L K, Dowson C G, Tenover F C, Spratt B G. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1306–1313. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coffey T J, Dowson C G, Daniels M, Spratt B G. Genetics and molecular biology of β-lactam-resistant pneumococci. Microb Drug Resist. 1995;1:29–34. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1995.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.du Plessis M, Smith A M, Klugman K P. Rapid detection of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in cerebrospinal fluid by a seminested-PCR strategy. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:453–457. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.453-457.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedland I R, McCracken G H. Management of infections caused by antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. N Engl J Med. 1994;31:377–382. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408113310607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greisen K, Loeffelholz M, Purohit A, Leong D. PCR primers and probes for the 16S rRNA gene of most species of pathogenic bacteria, including bacteria found in cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:335–351. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.335-351.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hakenbeck R, Tarpay M, Tomasz A. Multiple changes in penicillin-binding proteins in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:364–371. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handwerger S, Tomasz A. Alterations in kinetic properties of penicillin-binding proteins of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;30:57–63. doi: 10.1128/aac.30.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassan-King M, Baldeh I, Secka O, Falade A, Greenwood B. Detection of Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA in blood cultures by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1721–1724. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.7.1721-1724.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kell C M, Jordens J Z, Daniels M, Coffey T J, Bates J, Paul J, Gilks C, Spratt B G. Molecular epidemiology of penicillin-resistant pneumococci isolated in Nairobi, Kenya. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4382–4391. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.10.4382-4391.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koneman E W, Allen S D, Janda W N, Schreckenberger P C, Winn W C., Jr . Color atlas and textbook of diagnostic microbiology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laible G, Spratt B G, Hakenbeck R. Interspecies recombinational events during the evolution of altered PBP 2X genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1993–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markiewicz Z, Tomasz A. Variation in penicillin-binding protein patterns of penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of pneumococci. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:405–410. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.3.405-410.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin C, Sibold C, Hakenbeck R. Relatedness of penicillin-binding protein 1a genes from different clones of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae isolated in South Africa and Spain. EMBO J. 1992;11:3831–3836. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A3. 3rd ed. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical laboratory Standards; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paithankar K R, Prasad K S N. Precipitation of DNA by polyethylene glycol and ethanol. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:1346. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.6.1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Potgieter E, Chalkley L J. Reciprocal transfer of penicillin resistance genes between Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus mitior and Streptococcus sanguis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;28:463–465. doi: 10.1093/jac/28.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rådstrom P, Backman N, Qian N, Kragsbjerg P, Pahlson C, Olcen P. Detection of bacterial DNA in cerebrospinal fluid by an assay for simultaneous detection of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae and streptococci using a seminested PCR strategy. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2738-2744.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith A M, Klugman K P, Coffey T J, Spratt B G. Genetic diversity of penicillin-binding protein 2B and 2X genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae in South Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1938–1944. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.9.1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith A M, Klugman K P. Alterations in PBP 1A essential for high-level penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1329–1333. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.6.1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zighelboim S, Tomasz A. Penicillin-binding proteins of multiply antibiotic resistant South African strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:434–442. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.3.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]