Abstract

Background: Somatization is a common symptom among patients with comorbid anxiety and depression. It is associated with poorer outcome, long-term evolution, worse sleep patterns and an overall lower quality of life. Previous studies suggest that sleep disturbances exacerbate somatization, which in turn negatively affects sleep. The purpose of this study was to determine the correlation between anxiety/depression and somatization/sleep quality in hospitalized psychiatric patients.

Methods:Participants comprised 103 hospitalized patients with somatic symptoms disorder as major diagnosis and anxiety and depression disorders as comorbid diagnoses. All subjects were given SOMS-2 and SOMS-7 (Screening for Somatoform Symptoms) for somatization symptoms, HAM-A (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale) for anxiety, HAM-D 17 (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) for depression and PSQI (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) for sleep quality. The Somatic Symptom Disorder-B criteria scale (SSD-12) has been also used for the psychological impact of somatization. The same scales were administered to a control group of 77 participants by trained physicians.

Results:There was a negative correlation between the scores of HAM-A/HAM-D scales and those of SSD-12. Also, positive associations between the scores of anxiety and depression scales in patients with sleep disturbances were found. Sleep scores being assessed with PSQI were significantly higher after hospitalization in 80% of participants and did not correlate with neither anxiety/depression nor somatization. In the participant group, SOMS-2 results were not correlated with any social and demographic variables. All scales scores were worse in the study group than the control group.

Conclusion:Anxiety and depression symptoms may be associated with higher somatization symptoms but not with the psychological impact of somatization. Also, somatization may not directly impact sleep quality scores. Further approaches are needed to better understand the relationship between sleep quality and somatization, on one hand, and its modulation by comorbid psychiatric disorders, on the other hand.

Keywords:somatization, sleep quality, depression, anxiety, somatoform.

INTRODUCTION

The concomitance of sleep disturbances and somatization can contribute to extensive social, professional and familial impairment. In combination with economic and social burden, this can lead to both an increased perception of overall dysfunction and higher medical addressability. This relationship can be mediated among psychiatric patients by comorbid disorders such as depression and anxiety. Given that sleep disturbances and other sleep disorders can be addressed via psychosocial and/or pharmacological interventions, it is critical to understand their prevalence, correlations, comorbidities and predictors in order to elucidate their contribution to somatization and improve the current standards of somatization treatment. Somatization and sleep disturbances are two conditions commonly encountered in the general population. Previous studies estimated that somatization affected 14-17% of the general population (1-4), while the prevalence of sleep disturbances was found to be about 10-15%. When discussing the comorbidity between somatization and insomnia, this has been reported in 24-32% of all subjects, nearly double than in the general population (5, 6).

A wide variety of sleep disturbances in chronic pain patients ranged from 40-80% (7, 8). Also, 25-50% of the symptoms that patients present to their general practitioner (GP) remain unexplained (9), although about 20-30% of these patients develop persisting symptoms, with 71% presenting low QOL (quality of life) scores and extreme social burden (10, 11). This highlights a critical need to understand the possible role of sleep quality on the evolution and exacerbation of somatization among patients with SSD as well as the possible bidirectional relationship between somatization and sleep disturbances (potentially mediated by psychiatric comorbidities such as depression and anxiety).

Our study aimed to investigate whether sleep disturbances were correlated with somatization and its psychological impact, and to find the degree to which comorbid psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety mediate the relationship between them. This study analyzed patients' sleep quality, the relationships between sleep disturbances, somatization, anxiety/depression, and the psychological impact of somatization, so that new approaches could be developed to improve somatization patients' clinical symptoms and overall quality of life.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Participants were selected from patients hospitalized in the Psychiatry Department of the Clinical Psychiatry Hospital of Bucharest between January 2018 and June 2020. All subjects met the inclusion criteria of diagnosed somatic symptom disorder as major diagnosis and generalized anxiety disorder and depressive disorder as secondary diagnoses, according to The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) criteria (12). The exclusion criteria were the presence of any psychotic disorder, any cognitive impairmentrelated disorder, any somatic conditions that could lead to sleep disturbances or somatic symptoms (sleep apnea syndrome, asthma, epilepsy, any cardiac or gastroenterological disorder and so on), presence of substance use disorder that could lead to sleep disturbances, IQ < 70, and any visual/ hearing disorders. For the control group, the inclusion criteria consisted in lack of any diagnosed psychiatric condition and current sleep disturbances based on self-reported history and matching for age, sex and educational level with subjects from the study group.

Our study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Clinical Psychiatry Hospital of Bucharest and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

METHODS

Questionnaires

The questionnaires used in our study included instruments collecting information about demographic characteristics and somatization symptoms, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Screening for Somatoform Symptoms (SOMS-2 and SOMS-7), Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A), Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D), and Somatic Symptom Disorder-B criteria Scale (SSD-12).

Somatization symptoms

In their first day of hospitalization, patients with somatization were asked about common symptoms of somatization such as headaches, joint and member pain, nausea, palpitations, vomiting, chest pain, with questions about a total number of 53 symptoms being asked. Symptoms were divided into the following sub-categories: musculoskeletal symptoms, digestive symptoms, cardiac and respiratory symptoms, sexual symptoms and neurological symptoms (13, 14). The SOMS-2 scale was administered in order to count the number of symptoms and their distribution during a two-year period prior to hospitalization. Higher scores in SOMS-2 indicated a higher severity of somatization. The same symptoms were reviewed after seven days of hospitalization using SOMS-7, which was rated on a four-point Likert scale regarding intensity, with patients being asked to describe the degree of their symptom intensity.

PSQI

The PSQI was used to evaluate the sleep quality of patients with somatization. This scale consists of 18 self-reported items that are divided into seven subcategories, including subjective sleep quality, time to fall asleep, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction with proven efficiency and consistency (15-17). The score ranges from 0 to 3 for each category, with higher total scores indicating a lower sleep quality from 5 to 23. The scale was administered before hospitalization and after seven days in order to observe symptom evolution.

HAM-A and HAM-D

Anxiety and depression were measured using HAM-A and HAM-D, respectively. Both scales bare commonly used tools to evaluate the severity of anxiety and depression, and their liability and validity have been well established (18-20). Patients who scored higher than 17 were recognized to be suffering from severe anxiety as well as scores over 19 in HAM-D reporting moderate depression.

SSD-12

SSD is a self-report questionnaire used to assess the B criteria of DSM-V somatic symptom disorder and measures patients' perceptions of their symptom-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (21). It comprises 12 items that are divided into three subscales, including cognitive, affective and behavioral aspects, with a total score of 48. SSD-12 was used for the first time in Romania after being officially translated by the authors of the present study, with the permission of the creators of the scale, with good internal consistency.

Control group

The control group received all questionnaires but SOMS-7 and PSQI after seven days. Participants with PSQI scores higher than 5 were reported as having sleep disturbances.

Statistical analysis

After the data collection stage, they were registered as variables of interest and analysis using the statistical program R, version 4.0.2 (2020-06-22) Copyright (C) 2020 The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, R Core Team (2020). A: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org. In addition to the standard packages, the psych package Revelle W. (2020) psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois, USA, was used https://CRAN.Rproject. org/package=psych Version=2.0.7. The statistical tests used by us were carefully selected, taking into account the type of variables, distribution of the values taken by the variables and, last but not least, questions to be answered through statistical analysis. To signal a significant effect, indicators of the effect size produced were reported (d, η 2, η 2 partially), statistical significance (p value), analysis of the consistency of Alpha Cronbach questionnaire scores (together with 95% CI), correlation plot together with distributions, the Pearson correlation indices. Statistical significance was set at P-value less than 0.05 and P-value less than 0.01 was regarded as significant difference. The comparative analysis of scores on scales followed in the study included the study group and the control group. Given the number of patients in both groups, a Welch T bidirectional test was used for comparison of two independent samples (test from the family of parametric tests). The possibility of correlations/associations between the scores on the scales used by us was studied using the Pearson correlation index.

RESULTS

Demographic data

One hundred and three adult inpatients with somatization disorder were selected to participate in our study group. Among them, 74 reported sleep disturbances and 29 normal sleep. The ratio of patients with sleep disturbances was 71.84%. (74/103). Subjects had a mean age of 52.88 ± 11.29, and the male to female ratio was 1:18.39. Out of all the subjects in the study group, 56.32 were living in a rural area, with only 16.51% reporting higher education background.

In the control group, subjects had a mean age of 41.00, and 87.01% of them reported an urban area as living place. There were no statistically differences in the demographic characteristics of the two groups (all Ps > 0.05).

Symptoms of anxiety and depression in the somatization group

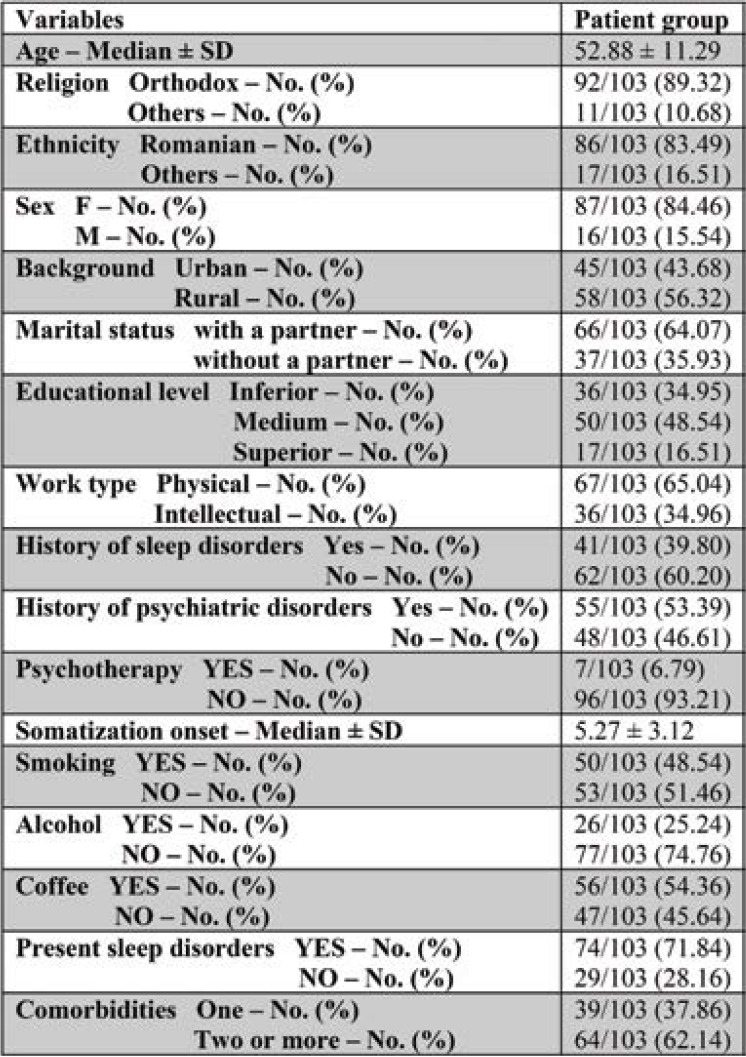

Patients reported high scores on the anxiety scale; 8.73% of them had scores under the cut-off point for severe anxiety, with "anxious mood", "phobias", "vegetative symptoms" and "focus deficiency" scoring higher than all the other items, as shown in Figure 1. Also, there were 20% percent higher scores on HAM-A among patients reporting normal sleep (p < .01).

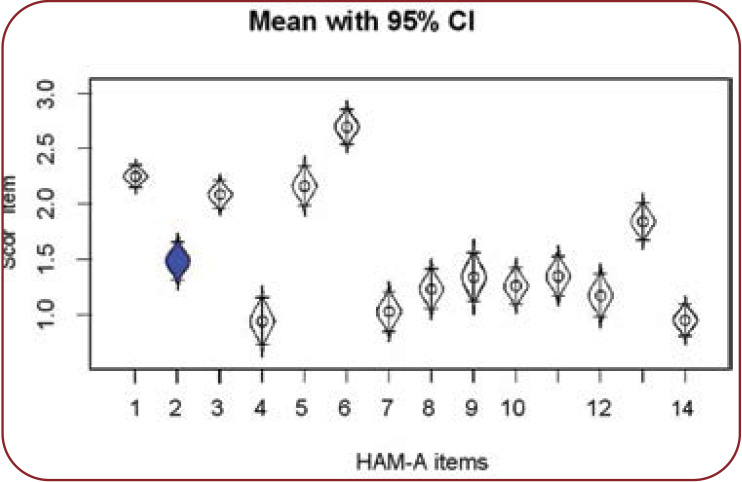

In the subscale of "Mental Anxiety" there were two negative correlations between "depressive mood" and "focus deficiency". Regarding the "Somatic Anxiety", there were only positive correlations between items and total score, as shown in Figure 2. Also, the mean scores on HAM-A reported by the somatization group were four times higher than the control group (p < .01).

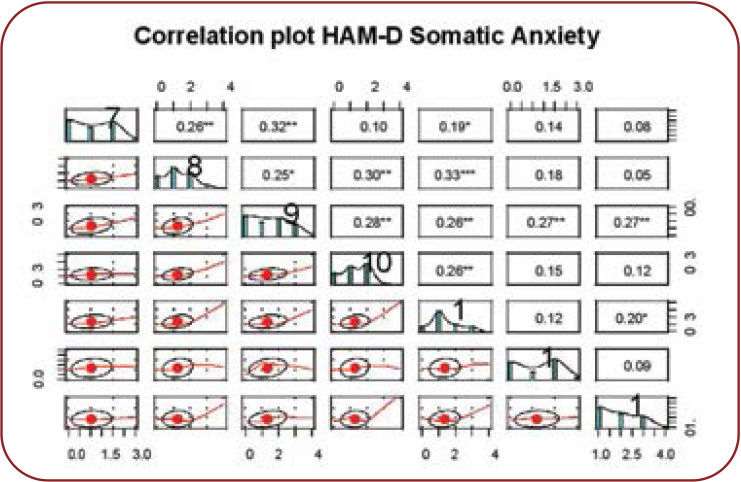

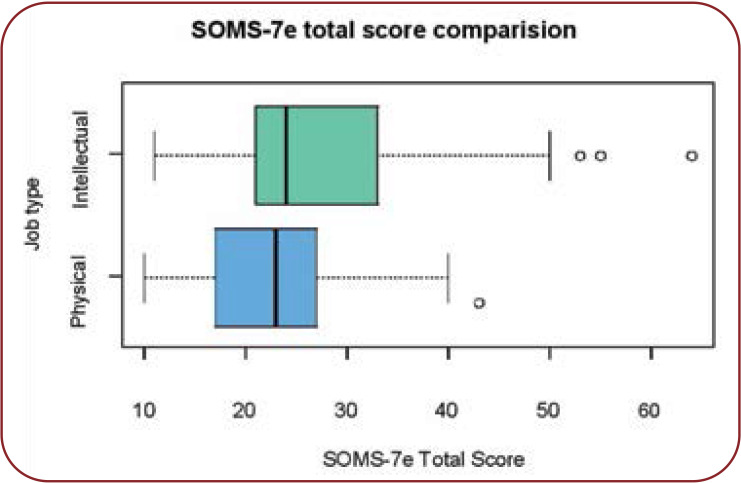

From the total of 103 patients, 7.76% of scores were included in "moderate depression", 32.03% in "severe depression", while the remaining scores fell into the "very severe depression" cut-off point. We should mention that patients were hospitalized for both depressive and somatization symptoms with the pharmacological treatment targeting depressive symptoms. Also, significant higher scores were reported for "depressive mood", "feelings of guilt" and "work and hobbies" items with very low values for "suicide ideation", "insight" and "psychomotor retardation", as shown in Figure 3. Also, scores reported by women were 10% higher on the scale (p < .05), and "physical work" scored 7% higher than "intellectual work" (p < .05). Mean HAM-D scores reported by the somatization group were five times higher than those reported by the control group (p < .01).

Somatization scores in the study group

The average time from onset of somatization disorder was 5.2 years, with depressive disorder having an average time of onset of 7.2 years, and the mean age of diagnosis of somatization being 46.5 years. The total SOMS-7 score was 20% higher in patients reporting "intellectual work" (p < .05). The influence of social and demographic variables on SOMS-2 had no statistical significance (p > .05).

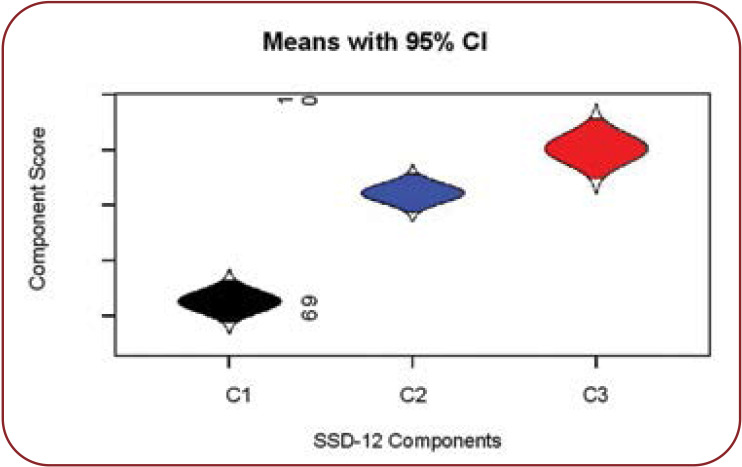

Psychological impact of somatization in the study group

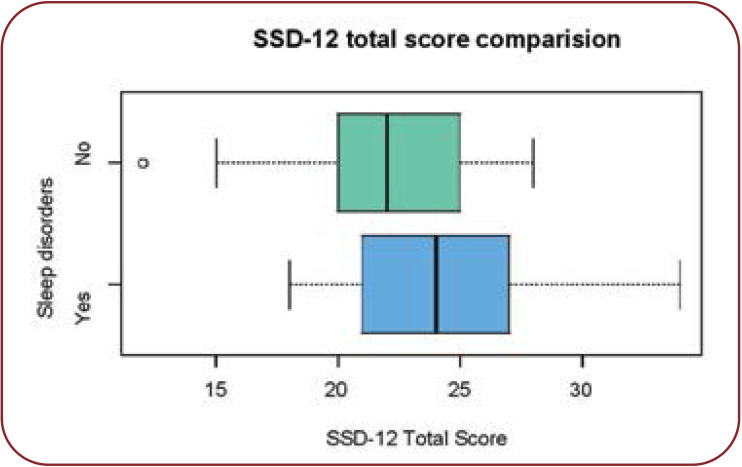

Item C1 was negatively correlated with both the other two items and the overall SSD-12 score, with the highest scores being reported for C3, "Behavioral aspect", as shown in Figure 4. The mean score for SSD-12 was 10% higher in patients reporting sleep disturbances (p < .05).

The mean score for SSD-12 was 10% higher in patients reporting sleep disturbances (p<.05), as shown in Figure 5. Also, the mean score for SSD-12 in somatization group is seven times higher than in the control group (p < .01).

Sleep quality in the somatization group

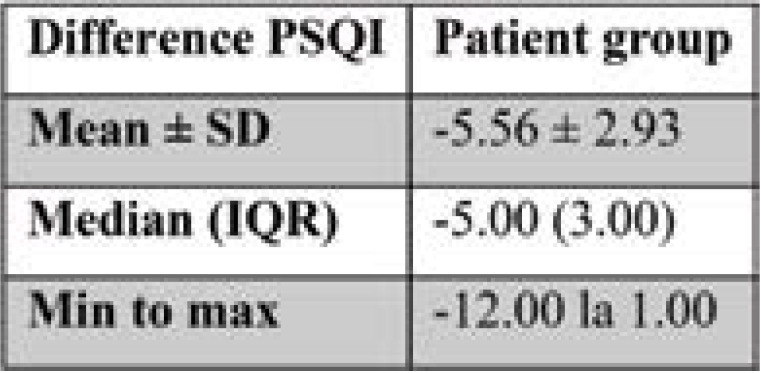

Every patient reported scores over 5 on PSQI, indicating an overall poor sleep quality. The mean total sleep time was 5.63 hours per night, with sleep onset latency being 36.55 min. Out of all patients, 71.84% reported the use of sleep medication during the past month and only 40.77% reported daytime dysfunction three or more times each week. Only six out of 103 subjects scored high for the "sleep disturbances" item, with overall PSQI score indicating severe difficulties. After a mean period of hospitalization, PSQI was administered again and that time, the scores improved with a mean of six units, the biggest improvement being as much as 12 units, as shown in Table 1. Also, PSQI score was 20% higher in the somatization group than in control one (p < .01). Higher PSQI scores were associated with reported behaviour of smoking (p < .01).

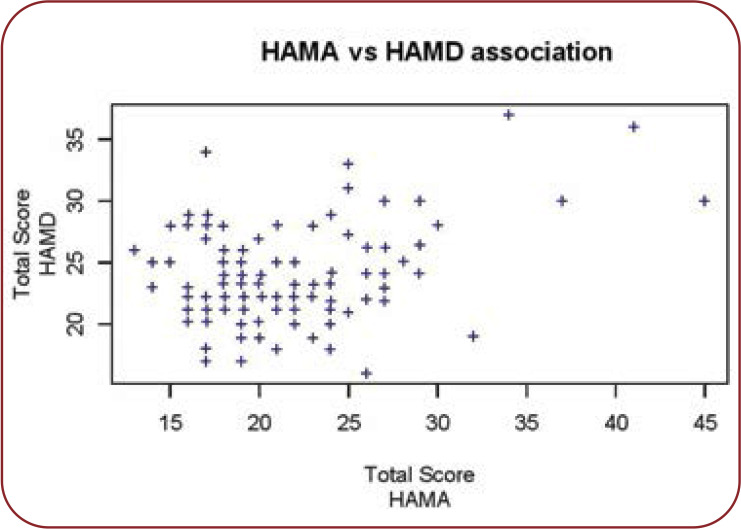

Association of anxiety and depression symptoms with somatization and sleep disturbances

Firstly, there is a positive average correlation between HAM-A and HAM-D scores, as shown in Figure 7.

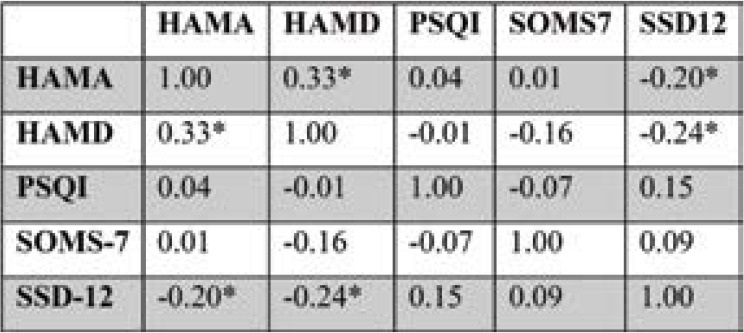

There are negative correlations between HAM-A and SSD-12 scores as well as between HAM-D and SSD-12 scores, as shown in Table 2. Also, SOMS-7 and PSQI do not present statistically significant correlations in the somatization group, as seen in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Sleep disturbances and their correlation with somatization

The correlation between sleep disturbances and somatization touches psychological, genetical, psychiatric, daily functioning and neurophysiological areas, with many studies reviewing their possible bidirectional relationship. Le Blanc highlighted that the new onset of sleep disturbances at one year follow-up was associated with a higher level of bodily pain and somatization, among other psychological variables (22). Additionally, Zhang reported that the severity of sleep disturbances was correlated with the severity of somatization and available evidence suggested that sleep disturbances was serving as a predisposing cause for future physical complaints and problems (23). Furthermore, Zhang conducted a follow-up study on a five-year duration that suggests that baseline sleep disturbances are a predictor of several somatic symptoms and physical disorders (24). Aigner et al. (25) suggest the existence of a bidirectional relationship between sleep disturbances and somatization; more specifically, they claim that sleep disturbances may be a factor in the persistence and aggravation of already-present somatic symptoms as well as in enhancing the somatic symptoms-derived psychosocial disability.

Our study showed that overall scores were worse for sleep and higher for somatization in the study group. Also, the mean score for SSD-12 was 10% higher among patients reporting sleep disturbances (p < .05), but there was no correlation between PSQI and somatization scores. However, the scores for sleep improved with an average of six units after seven days of hospitalization, during which subjective somatization was also improved among patients. The results suggest a significant difference between scale scores and subjective perception of sleep patterns and somatization during a period of hospitalization. This may explain the lack of correlation regarding the scores. Also, the psychological impact of somatization identified a negative correlation between the C1 item of SSD-12, "cognitive aspects", and the overall score, meaning that patients did not score high on questions regarding either the self-perception of severity of their own symptoms or the likelihood of a severe somatic illness. In the study of Toussaint et al., patients with a higher SSD-12 psychological symptom burden reported higher general physical and mental health impairment and a significantly higher health care use (21). Our findings underline the need for future differentiation between psychological aspects of somatization and anxiety symptoms associated in many patients, which could lead to the same reported symptomatology.

Comorbid anxiety/depression and somatization

Yu et al. reported that people with depression were more likely to have multiple medically unexplained symptoms, insomnia and fatigue (26). Also, Stapleton suggested that higher somatization scores were significantly positively associated with reported depression and anxiety (27). Other two studies reported higher somatization scores with higher reported depression scores and self-reported depressed mood (28-30).

On the other hand, Hagnell reported that only 10-30% of patients with depression had somatic symptoms/somatization (31). More consistent with oru results are those reported by Jones, who found that 20% of patients with depression reported somatic symptoms (32), and by Gillespie et al., who noted that somatic symptoms, although correlated, are independent of anxiety and depression (CC=0.99-0.70) (33).

Our study reported no correlations between anxiety/depression scores and overall scores in SOMS-7 and only weak negative correlations between HAM-A and HAM-D scores and SSD-12. These results suggest that anxiety/depressive symptoms might not be well associated with somatization, but they may have an influence on the psychological impact of somatization. Also, there was a positive correlation between HAM-A and HAM-D scores, confirming the relationship between depression and anxiety as often associated factors.

Regarding sleep quality, there are a number of studies which reported that sleep disturbances were correlated with somatic symptoms in depressive patients and that depression and anxiety were associated with somatic complaints and low sleep quality (28, 34-36).

Our results showed that patients reporting sleep disturbances had 20% higher scores on HAM-A, which confirms a possible relationship between anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbances. However, our study showed no significant correlation between depression scores and PSQI scores, despite PSQI scores improvement with an average of six units after antidepressant and anxiolytic medication during hospital stay. Overall, there is no significant result concerning a causal relationship between somatization and sleep disturbances. The role of depression and anxiety might consist of modulating the symptoms of somatization and sleep disturbances, as well as overlapping symptomatology, with important genetical, biological and psychological links.

Limitations

Although we have come up with some important results, there were several limitations in our study that should be mentioned. First, we conducted a cross-sectional study, with a small number of participants. Instead of objectively examining sleep disturbances and somatization by electrophysiological techniques, actigraphy or polysomnography, we used self-report questionnaires to evaluate clinical manifestations. Hence, recall and self-report bias were difficult to be avoided. Secondly, patients included in our study came from a single hospital, and most of them lived in a particular area of Southern Romania. As a result, our findings may be different from those of studies exploring populations from different regions and different levels of hospitals as well as different numbers of participants. Thirdly, basic and clinical research is further required to check the relationship of somatization and sleep disturbances, anxiety and depression. Finally, the bidirectional relationship between somatization and sleep disturbances in comorbid psychiatric patients is still needed to be evaluated carefully and followed-up on a significant duration.

CONCLUSION

Our results highlighted the relationship between sleep quality and the psychological impact of somatization more than the somatization symptoms themselves. Also, there were no significant correlations between anxiety/ depression and sleep quality, although overall post-hospitalization subjective symptoms regarding sleep and somatization improved. Generally speaking, somatization may influence sleep quality regarding onset and prognosis but their relationship might be modulated by comorbid depression and anxiety. Patients' subjective perception may differ from their reported scores for various individual reasons. Therefore, we recommend careful identification and diagnosis of overlapping somatization and sleep disturbances with anxiety and depression symptoms, so that each patient should benefit of overall more qualitative management and better prognosis. Besides psychotropic treatment for anxiety and depression as well as sleep disturbances and somatization there is a need for combined psychotherapeutic approach regarding somatization and sleep. To sum up, patients' overall mental state and overlapping symptoms should be comprehensively evaluated before treatment, and afterwards individualized therapy should be provided so that patients could benefit more in the future.

Conflict of interests: none declared.

Financial support: none declared.

Authors’ contributions: This work was conducted in collaboration with all authors. CI was the primary investigator. IB supervised the overall research project. All authors performed the clinical investigation (diagnosis, treatment, and assessment). All authors approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements: We want to thank Corina Manescu and Eugen Popescu for the writing assistance, technical support, statistical analysis, language editing and proofreading. We also like to express our very great appreciation for Dr. Raluca Papacocea, Dr. Silvia Constantinescu and Dr. Oana Buscu for thier constructive suggestions, enthusiastic encouragement and overall support for our work and ideas.

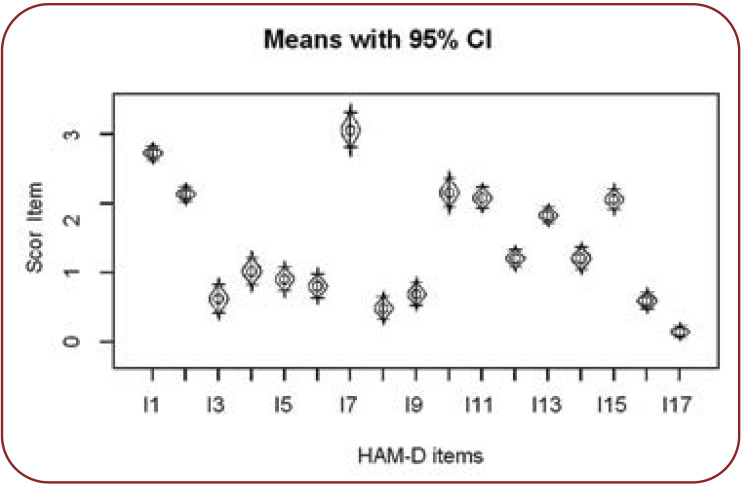

TABLE 1.

Demographic data of the study group

FIGURE 1.

Mean score for each item of HAM-A

FIGURE 2.

Correlation plot for ,,Somatic Anxiety” subscale of HAM-A

FIGURE 3.

Mean scores for each item of HAM-D

FIGURE 4.

Total SOMS-7 score related to job type

FIGURE 5.

Mean scores for SSD-12 aspects

FIGURE 6.

Total SSD-12 related to sleep disturbances

FIGURE 7.

Correlation between HAM-D and HAM-A scores

TABLE 2.

Distribution of PSQI scores before and after discharge

TABLE 3.

Correlation indices r Pearson for scales used in the somatization group

Contributor Information

Claudiu G. IONESCU, “Carol Davila“ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Physiology Department, Bucharest, Romania

Ana A. TALASMAN, “Carol Davila“ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Psychiatry Department, Bucharest, Romania

Ioana A. BADARAU, “Carol Davila“ University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Physiology Department, Bucharest, Romania

References

- 1.Faravelli C, Salvatori S, Galassi F, et al. Epidemiology of somatoform disorders: a community survey in Florence. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1997;32:24–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00800664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilderink PH, et al. Prevalence of somatoform disorders and medically unexplained symptoms in old age populations in comparison with younger age groups: a systematic re-view. Ageing Research Reviews. 2013;12:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiller W, Rief W, Brähler E. Somatization in the population: from mild bodily misperceptions to disabling symptoms. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41:704–712. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0082-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Creed F, Barsky A. A systematic review of the epidemiology of somatization disorder and hypochondriasis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;4:391–408. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00622-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Power JD, Perruccio AV, Badley EM. Pain as a mediator of sleep problems in arthritis and other chronic conditions. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;6:911–919. doi: 10.1002/art.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roizenblatt S, Souza AL, Palombini L, et al. Musculoskeletal pain as a marker of health quality. Findings from the Epidemiological Sleep Study among the adult population of Sao Paulo City. PLoS One. 2015;11:e0142726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tang NK, Wright KJ, Salkovskis PM. Prevalence and correlates of clinical insomnia co-occurring with chronic back pain. J Sleep Res. 2007;1:85–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Artner J, Cakir B, Spiekermann J-A, et al. Prevalence of sleep deprivation in patients with chronic neck and back pain: A retrospective evaluation of 1016 patients. J Pain Res. 2013;6:1–6. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S36386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barsky A, Borus J. Somatization and medicalization in the era of managed care. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;24:1931–1934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verhaak PFM, Meijer SA, Visser AP, Wolters G . Persistent presentation of medically unexplained symptoms in general practice. Fam Pract. 2006;4:414–420. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson JL, Passamonti M. The outcomes among patients presenting in primary care with a physical symptom at 5 years, J Gen Intern Med. 2005;11:1032–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed, Arlington. 2013.

- 14.Fabião C, Silva M, Barbosa A, et al. Assessing medically unexplained symptoms: evaluation of a shortened version of the SOMS for use in primary care. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;1:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;2:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pilz LK, Keller LK, Lenssen D, Roenneberg T. Time to rethink sleep quality: PSQI scores reflect sleep quality on workdays. Sleep. 2018;5 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buysse D, Hall M, Strollo PJ, et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;6:563–571. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohan KJ, Rough JN, Evans M, et al. A protocol for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: Item scoring rules, Rater training, and outcome accuracy with data on its application in a clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;200:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.01.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.López-Pina JA, Sánhez-Meca J, Rosa-Alcázar AI. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression:a meta analytic reliability generalization study. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2009;1:143–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, Heuser I. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1988;1:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(88)90072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toussaint A, Murray AM, Voigt K, et al. Development and Validation of the Somatic Symptom Disorder–B Criteria Scale (SSD-12). Psychosomatic Medicine. 2016;1:5–12. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBlanc M, Mérette C, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Insomnia in a Population-Based Sample. Sleep. 2009;8:1027–1037. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.8.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Lam S-P, Li SX, et al. Insomnia, sleep quality, pain, and somatic symptoms: Sex differences and shared genetic components. Pain. 2012;3:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Lam SP, Li SX, et al. Long-term outcomes and predictors of chronic insomnia: a prospective study in Hong Kong Chinese adults. Sleep Med. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Aigner M, Graf A, Freidl M, et al. Sleep Disturbances in Somatoform Pain Disorder. Psychopathology. 2003;6:324–328. doi: 10.1159/000075833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu DSF, Lee DTF. Do medically unexplained somatic symptoms predict depression in older Chinese? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;2:119–126. doi: 10.1002/gps.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stapleton PB, Brunetti M. The effects of somatisation, depression, and anxiety on eating habits among university students. International Journal of Healing and Caring. 2013;3:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartz A, Ross JJ, Noyes R, Williams P. Somatic symptoms and psychological characteristics associated with insomnia in postmenopausal women. Sleep Medicine. 2013;1:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mol AJJ, Gorgels WJMJ, Oude Voshaar RC, et al. Associations of benzodiazepine craving with other clinical variables in a population of general practice patients. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2005;5:353–360. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Annagür BB, Uguz F, Apiliogullari S, et al. Psychiatric Disorders and Association with Quality of Sleep and Quality of Life in Patients with Chronic Pain: A SCID-Based Study. Pain Medicine. 2014;5:772–781. doi: 10.1111/pme.12390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hagnell O. Rorsman B. Suicide and endogenous depression with somatic symptoms in the Lundby study. Neuropsychobiology. 1978;4:180–187. doi: 10.1159/000117631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones 0, Hall SB. Significance of somatic complaints in patients suffering from psychotic depression. Acta Psychotherapeutica. 1963;11:193–199. doi: 10.1159/000285676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gillespie N, Kirk KM, Heath AC, et al. Somatic distress as a distinct psychological dimension. S. ocial Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1999;9:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s001270050219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davidson J, Krishnan R, France R, Pelton S. Neurovegetative Symptoms in Chronic Pain and Depression. Journal of Affectwe Disorders. 1985;9:213–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bekhuis E, Schoevers RA, van Borkulo CD, et al. The network structure of major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder and somatic symptomatology. Psychological Medicine. 2016;14:2989–2998. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lankes F, Schiekofer S, Eichhammer P, Busch V. The effect of alexithymia and depressive feelings on pain perception in somatoform pain disorder. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2020;133:110101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]