Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has resulted in considerable morbidity and mortality worldwide. COVID-19 incidence, severity, and mortality rates differ greatly between populations, genders, ABO blood groups, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes, ethnic groups, and geographic backgrounds. This highly heterogeneous SARS-CoV-2 infection is multifactorial. Host genetic factors such as variants in the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene (ACE), the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene (ACE2), the transmembrane protease serine 2 gene (TMPRSS2), along with HLA genotype, and ABO blood group help to explain individual susceptibility, severity, and outcomes of COVID-19. This review is focused on COVID-19 clinical and viral characteristics, pathogenesis, and genetic findings, with particular attention on genetic diversity and variants. The human genetic basis could provide scientific bases for disease prediction and targeted therapy to address the COVID-19 scourge.

Subject terms: Infectious diseases, Predictive markers, Medical genetics

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is this century’s third plague and was declared as the sixth international concerned public health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 30 January 2020.1,2 The responsible pathogen is a previously unknown RNA coronavirus.1,3,4 It was designated as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.5 As of 17 May 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in 162,494,817 cases and 3,494,424 deaths worldwide (https://covid19.who.int/). COVID-19 is highly heterogeneous and its severity may relate to multiple factors including health care, quarantine effectiveness, governmental policies, societal norms of behavior, economics, cultural practices, climate, pollution, and viral characteristics, as well as host-associated factors.6–10 In the aspect of host-associated factors, in addition to age (>60 years), initial health status, pre-existing diseases, smoking history, and previous vaccinations, individual genetic basis contributes to individual susceptibility, severity, and outcomes of COVID-19.7,11,12 Classical twin studies indicated 31% heritability for predicted COVID-19.13 Human genetic basis may implicate in significant diversities of COVID-19 among populations with different genders, ABO blood groups, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes, ethnic groups, and geographic backgrounds.6,14–16 Several gene variants related to gene expression and protein function changes were reported as explaining the individual susceptibility, severity, and outcomes.12,17

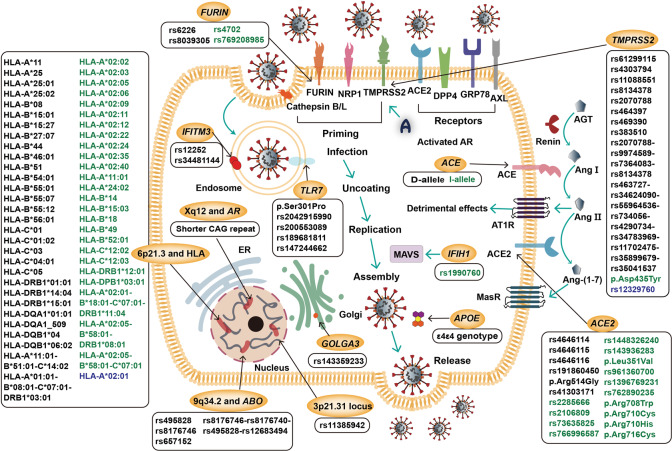

In this review, clinical and viral characteristics, pathogenesis, and the human genetic basis associated with COVID-19 are investigated. Focus is on the protective and risk effects of variants in related genes such as the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene (ACE), the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene (ACE2), the transmembrane protease serine 2 gene (TMPRSS2), and ABO blood groups and HLA genotypes (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Summary of human genes associated with COVID-19

| Locus | Gene(s) or genotype | Variant(s) or allele(s) or haplotype(s) | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Protective | Uncertain | |||

| 2q24.2 | IFIH1 | / | rs1990760 | / | 102,103 |

| 3p21.31 | SLC6A20 | / | / | / | 104–108 |

| LZTFL1 | rs11385942 | / | / | ||

| FYCO1 | / | / | / | ||

| CXCR6 | / | / | / | ||

| XCR1 | / | / | / | ||

| CCR9 | / | / | / | ||

| 6p21.3 | HLA | HLA-A*11 | HLA-A*02:02 | HLA-A*02:01 | 9,15,16,18,97,115,117–127,130 |

| HLA-A*25 | HLA-A*02:03 | ||||

| HLA-A*25:01 | HLA-A*02:05 | ||||

| HLA-A*25:02 | HLA-A*02:06 | ||||

| HLA-B*08 | HLA-A*02:09 | ||||

| HLA-B*15:01 | HLA-A*02:11 | ||||

| HLA-B*15:27 | HLA-A*02:12 | ||||

| HLA-B*27:07 | HLA-A*02:22 | ||||

| HLA-B*44 | HLA-A*02:24 | ||||

| HLA-B*46:01 | HLA-A*02:35 | ||||

| HLA-B*51 | HLA-A*02:40 | ||||

| HLA-B*54:01 | HLA-A*11:01 | ||||

| HLA-B*55:01 | HLA-A*24:02 | ||||

| HLA-B*55:07 | HLA-B*14 | ||||

| HLA-B*55:12 | HLA-B*15:03 | ||||

| HLA-B*56:01 | HLA-B*18 | ||||

| HLA-C*01 | HLA-B*49 | ||||

| HLA-C*01:02 | HLA-B*52:01 | ||||

| HLA-C*03 | HLA-C*12:02 | ||||

| HLA-C*04:01 | HLA-C*12:03 | ||||

| HLA-C*05 | HLA-DRB1*12:01 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1*01:01 | HLA-DPB1*03:01 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1*14:04 | HLA-A*02:01-B*18:01-C*07:01-DRB1*11:04 | ||||

| HLA-DRB1*15:01 | HLA-A*02:05-B*58:01-DRB1*08:01 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1*01:01 | HLA-A*02:05-B*58:01-C*07:01 | ||||

| HLA-DQA1_509 | |||||

| HLA-DQB1*04 | |||||

| HLA-DQB1*06:02 | |||||

| HLA-A*11:01-B*51:01-C*14:02 | |||||

| HLA-A*01:01-B*08:01-C*07:01-DRB1*03:01 | |||||

| 9q34.2 | ABO | rs495828 | / | / | 104,135,137–139 |

| rs8176746 | |||||

| rs657152 | |||||

| rs8176746–rs8176740–rs495828–rs12683493 | |||||

| 9q34.3 | DPP7 | 1-bp insertion | / | / | 106 |

| 11p15.5 | IFITM3 | rs12252 | / | / | 141–146 |

| rs34481144 | |||||

| 12q24.33 | GOLGA3 | rs143359233 | / | / | 106 |

| 13q12.3 | HMGB1 | / | / | / | 149,150 |

| 15q26.1 | FURIN | rs6226 | rs4702 | / | 20,70,151 |

| rs8039305 | rs769208985 | ||||

| 17q23.3 | ACE | D-allele | I-allele | / | 80,86,154–158 |

| 19q13.32 | APOE | ε4ε4 genotype | / | / | 160–163 |

| 21q22.3 | TMPRSS2 | rs61299115 | p.Asp435Tyr | rs12329760 | 106,165–171 |

| rs4303794 | |||||

| rs11088551 | |||||

| rs8134378 | |||||

| rs2070788 | |||||

| rs464397 | |||||

| rs469390 | |||||

| rs383510 | |||||

| rs2070788–rs9974589–rs7364083–rs8134378 | |||||

| rs463727–rs34624090–rs55964536–rs734056–rs4290734–-rs34783969–rs11702475–rs35899679–rs35041537 | |||||

| Xp22.2 | TLR7 | p.Ser301Pro | / | / | 181,182 |

| rs2042915990 | |||||

| rs200553089 | |||||

| rs189681811 | |||||

| rs147244662 | |||||

| Xp22.22 | ACE2 | rs4646114 | rs2285666 | / | 4,8,17,151,152,165,166,168,171,183,184,191–197 |

| rs4646115 | rs2106809 | ||||

| rs4646116 | rs73635825 | ||||

| rs191860450 | rs766996587 | ||||

| p.Arg514Gly | rs1448326240 | ||||

| rs41303171 | rs143936283 | ||||

| p.Leu351Val | |||||

| rs961360700 | |||||

| rs1396769231 | |||||

| rs762890235 | |||||

| p.Arg708Trp | |||||

| p.Arg710Cys | |||||

| p.Arg710His | |||||

| p.Arg716Cys | |||||

| Xq12 | AR | Shorter CAG repeat | / | / | 101,176,200–203 |

IFIH1 the interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 gene, SLC6A20 the solute carrier protein family 6 member 20 gene, LZTFL1 the leucine zipper transcription factor like 1 gene, FYCO1 the FYVE and coiled-coil domain autophagy adaptor 1 gene, CXCR6 the C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 6 gene, XCR1 the X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 gene, CCR9 the C-C motif chemokine receptor 9 gene, HLA human leukocyte antigen, ABO the ABO, alpha 1–3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and alpha 1–3-galactosyltransferase gene, DPP7 the dipeptidyl peptidase 7 gene, IFITM3 the interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 gene, GOLGA3 the golgin A3 gene, HMGB1 the high-mobility group box 1 gene, FURIN the furin, paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme gene, ACE the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene, APOE the apolipoprotein E gene, TMPRSS2 the transmembrane protease serine 2 gene, TLR7 the Toll-like receptor 7 gene, ACE2 the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 gene, AR the androgen receptor gene.

Fig. 1.

Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and genetic variants associated with COVID-19. After the recognition of ACE2, DPP4, GRP78, and AXL receptors and the priming by TMPRSS2, FURIN, and NRP1, as well as cathepsin B/L, SARS-CoV-2 enters cells and starts the replication process to assemble and release. Activated AR induces TMPRSS2 expression. ACE/Ang II/AT1R and ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/MasR axes regulate RAAS to involve in COVID-19. The risk (black), protective (green), and uncertain (blue) variants or alleles or haplotypes for COVID-19 are highlighted. SARS-CoV-2 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, ACE2 angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, DPP4 dipeptidyl peptidase 4, GRP78 glucose-regulated protein-78, AXL anexelekto, TMPRSS2 transmembrane protease serine 2, FURIN furin, paired basic amino acid-cleaving enzyme, NRP1 neuropilin-1, AR androgen receptor, AGT angiotensinogen, Ang angiotensin, ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme, AT1R angiotensin II type 1 receptor, MasR Mas receptor, TLR7 the Toll-like receptor 7 gene, IFITM3 the interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 gene, HLA human leukocyte antigen, GOLGA3 the golgin A3 gene, ABO the ABO, alpha 1–3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and alpha 1–3-galactosyltransferase gene, APOE the apolipoprotein E gene, IFIH1 the interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 gene, MAVS mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein, ER endoplasmic reticulum

Clinical characteristics

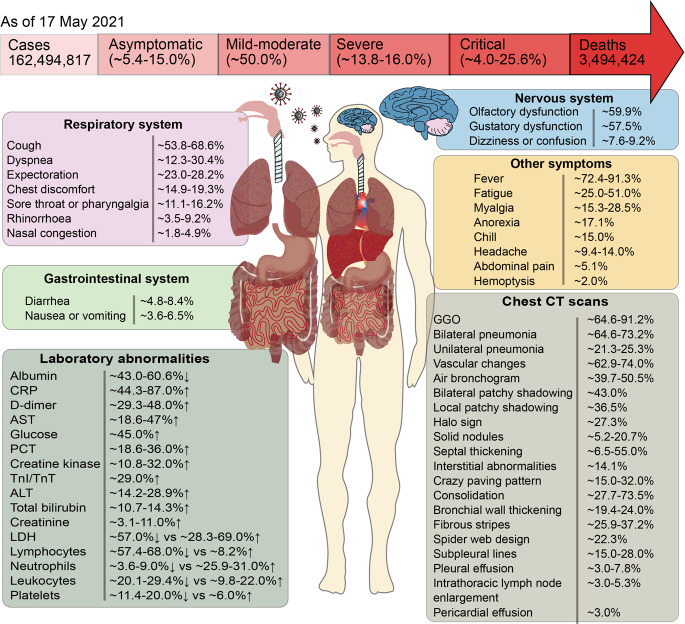

The COVID-19 clinical spectrum is heterogeneous (Fig. 2) and ranges from asymptomatic (∼5.4–15.0%), mild–moderate (∼50.0%), severe (∼13.8–16.0%) to critical (∼4.0–25.6%) status.18–22 Typical symptoms in most patients are mild and nonspecific, including fever (∼72.4–91.3%), cough (∼53.8–68.6%), smell dysfunction (∼59.9%), taste dysfunction (∼57.5%), fatigue (∼25.0–51.0%), dyspnea (∼12.3–30.4%), myalgia (∼15.3–28.5%), expectoration (∼23.0–28.2%), chest discomfort (∼14.9–19.3%), anorexia (∼17.1%), sore throat or pharyngalgia (∼11.1–16.2%), chill (∼15.0%), headache (∼9.4–14.0%), dizziness or confusion (∼7.6–9.2%), rhinorrhoea (∼3.5–9.2%), diarrhea (∼4.8–8.4%), nausea or vomiting (∼3.6–6.5%), abdominal pain (∼5.1%), nasal congestion (∼1.8–4.9%), and hemoptysis (∼2.0%).2,3,19,21–31 Some patients (usually those with advanced age and comorbidities) may rapidly progress to viral pneumonia, life-threatening acute respiratory distress syndrome, or multiple organ failures.32,33 In addition to the respiratory tract and lungs being primarily affected, other organs and systems such as the heart, blood vessels, gastrointestinal tract, liver, kidneys, skin, and nervous systems, can be adversely involved.34,35 Common laboratory abnormalities in COVID-19 patients are decreased albumin (∼43.0–60.6%), increased C-reactive protein (∼44.3–87.0%), D-dimer (∼29.3–48.0%), aspartate aminotransferase (∼18.6–47.0%), glucose (∼45.0%), procalcitonin (∼18.6–36.0%), creatine kinase (∼10.8–32.0%), troponin I/troponin T (∼29.0%), alanine aminotransferase (∼14.2–28.9%), total bilirubin (∼10.7–14.3%), and creatinine (∼3.1–11.0%), and decreased or increased lactate dehydrogenase (∼57.0% ↓ vs ∼28.3–69.0% ↑), lymphocytes (∼57.4–68.0% ↓ vs ∼8.2% ↑), neutrophils (∼3.6–9.0% ↓ vs ∼25.9–31.0% ↑), leukocytes (∼20.1–29.4% ↓ vs ∼9.8–22.0% ↑), and platelets (∼11.4–20.0% ↓ vs ∼6.0% ↑).25,28,29,36 Chest computed tomography (CT) scans revealed ground-glass opacity (∼64.6–91.2%), lesions consistent with bilateral (∼64.6–73.2%) or unilateral (∼21.3–25.3%) pneumonia, vascular changes (∼62.9–74.0%), air bronchogram (∼39.7–50.5%), bilateral or local patchy shadowing (∼43.0%, ~36.5%), halo sign (∼27.3%), solid nodules (∼5.2–20.7%), septal thickening (∼6.5–55.0%), interstitial abnormalities (∼14.1%), crazy paving pattern (∼15.0–32.0%), consolidation (∼27.7–73.5%), bronchial wall thickening (∼19.4–24.0%), fibrous stripes (∼25.9–37.2%), spider web design (∼22.3%), subpleural lines (∼15.0–28.0%), pleural effusion (∼3.0–7.8%), intrathoracic lymph node enlargement (∼3.0–5.3%), and pericardial effusion (∼3.0%).21,22,25,37–40

Fig. 2.

Overview of clinical characteristics of COVID-19. CRP C-reactive protein, AST aspartate aminotransferase, PCT procalcitonin, TnI/TnT troponin I/troponin T, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CT computed tomography, GGO ground-glass opacity

The causative pathogen, SARS-CoV-2

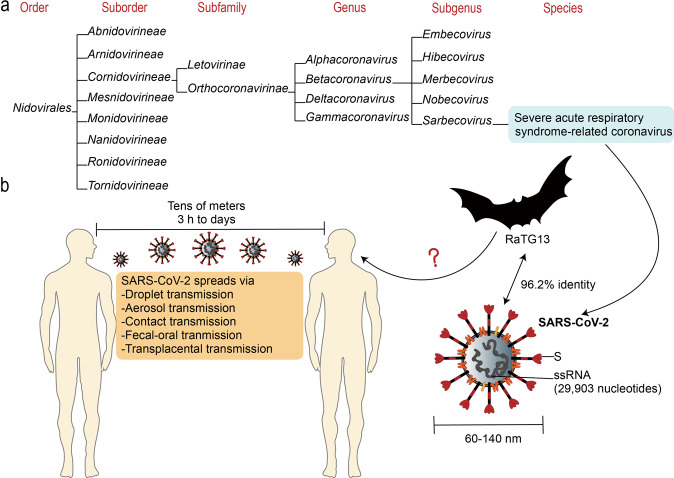

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, non-segmented, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus with 29,903 nucleotides in its genome sequence containing 5′ capped and 3′ polyadenylated.41–43 The 5′ two-thirds region of the genome is occupied by two large open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, that encodes 15–16 nonstructural proteins.44 Other functional ORFs encode structural and accessory proteins.45 The structural proteins include the distinctive spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, among which the S, E, and M proteins compose the envelope structure, while the N protein encapsulates the viral genome.46 SARS-CoV-2 is generally spherical with some pleomorphism and a diameter of ∼60–140 nm.3 The viral-enveloped lipid bilayer consists of cholesterols and phospholipids, which makes the virus susceptible to dry heat, detergents, and organic solvents.46 This novel coronavirus was assigned to the genus Betacoronavirus in the family Coronaviridae of the order Nidovirales (Fig. 3).18,42,47 SARS-CoV-2 has a 96.2% identity throughout the genome to RaTG13, a bat-borne coronavirus in Rhinolophus affinis.48 Droplet, aerosol, contact, fecal–oral and transplacental transmissions are documented human-to-human transmission routes.49–53 Small droplets with SARS-CoV-2 can travel tens of meters in favorable atmospheric conditions and remain viable and infectious from 3 h to days.32,54,55 Patients mildly affected and asymptomatic carriers constituting the majority of COVID-19 cases are thought to be primarily responsible for the spread of SARS-CoV-2.10,56

Fig. 3.

The causative pathogen, SARS-CoV-2. a The taxonomy of SARS-CoV-2 is shown (from https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy/). b SARS-CoV-2 is ssRNA virus with a diameter of ~60–140 nm and whole viral genome sequence of 29,903 nucleotides, and possesses distinctive S protein; 96.2% identity is shown between SARS-CoV-2 and a bat-borne coronavirus, RaTG13. SARS-CoV-2 spreads from human to human via droplet, aerosol, contact, fecal–oral, and transplacental transmissions. Droplets with SARS-CoV-2 can spread up to tens of meters and remain viable and infectious for 3 h to days. SARS-CoV-2 severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2, S spike protein, ssRNA single-strand RNA

As of 17 May 2021, the worldwide circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants mainly include the B.1.1.7 (63%), B.1.617.2 (22%), P.1 (6%), B.1.526 (2%), and others (https://covid19dashboard.regeneron.com). Lineage B.1.1.7 first detected in the United Kingdom in September 2020 has 21 characteristic mutations and exists in comparative transmission effectivity.57 Among the S protein mutations, the N501Y substitution would change the receptor-binding domain conformation and may slightly increase 18% of fatality risk. Mutation del69–70, considered to be responsible for stronger viral transmissibility, may cause S-gene target failure and produce a positive result for other targets at real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assays, which could be a proxy for diagnosing B.1.1.7 infections.58,59 Other two S protein substitutions, E484K in some strains of B.1.1.7 and L452R in B.1.617.2, may lead to much poorer effectivity of specific monoclonal antibody treatment in the corresponding infected cases (https://www.cdc.gov).

Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2

Entry and replication of SARS-CoV-2

Cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 depends on two determinants: (1) the viral S protein recognizes ACE2 receptor and (2) TMPRSS2 primes S protein.60,61 The S1 subunit of the envelope-embedded S glycoprotein attaches to the cellular ACE2 receptor via the polar contacts of hydrophilic residues.60,62 TMPRSS2 may trigger a proteolytic cleavage at the S1/S2 multibasic cleavage site.63,64 Other than ACE2, some studies reported that the human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), the cell-surface glucose-regulated protein-78, and the receptor tyrosine kinase anexelekto may also be conducive to viral entry and infection.65–68 Cathepsin B/L and furin, paired basic amino acid cleaving enzyme (FURIN) may also catalyze S protein proteolytic cleavage.64,69 As the S protein is cleaved to the S1 and the S2 domain, the cell surface receptor neuropilin-1 (NRP1) may bind to the C-terminal functional furin-cleavage sequence of the S1 domain more strongly in some cases and help the S2 isolating from the S1 domain.70,71 After S1 detachment, the S2 subunit undergoes a conformational change and mediates the fusion between the virus and the host membranes to mediate viral infection.71,72 The virus enters the cytoplasm and starts the replication process to assemble new viral particles and amplify its viral load.69,73 During the viral entry and replication process, cyclophilin A is essential for viral replication and its interaction with CD147 may mediate SARS-CoV-2 entering the host cells.65

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS)

RAAS is a complex system involved in multiple biological processes that are responsible for inducing a cascade of vasoactive peptides, which regulate vascular and renal functions.54,74,75 In the blood, the precursor angiotensinogen (AGT) is hydrolyzed to angiotensin I (Ang I) by the active renin.76,77 In the lungs, ACE removes the C-terminal dipeptide of Ang I to produce a potent vasoconstrictor, Ang II, which promotes detrimental effects by acting on Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R).78–80 ACE2 removes a single C-terminal amino acid from Ang I and Ang II to generate Ang-(1–9) and Ang-(1–7), of which the former is in turn converted to Ang-(1–7) by ACE.81 Ang-(1–7) counters Ang II cellular and molecular effects by binding and activating the G-protein-coupled Mas receptor (MasR).79,82,83 ACE2 catalytic efficiency with Ang II as a substrate is 400-fold higher than with Ang I.83,84 Accordingly, ACE2, an ACE homolog, is a key negative regulator antagonizing the activation of the classical RAAS by counterbalancing ACE actions.82,85 ACE and ACE2 maintain the homeostasis via the “adverse” ACE/Ang II/AT1R axis and the “protective” ACE2/Ang-(1–7)/MasR axis. In general, ACE/ACE2 imbalance contributes to RAAS overactivation and pulmonary shutdown, and a high ACE activity and a reduced ACE2 expression would increase the risk of pulmonary and cardiovascular diseases.86 ACE2 mainly binds to cell membranes and rarely exists in a circulating soluble form.72 Continued viral infection and replication markedly downregulate ACE2 receptors, leading to the loss of the catalytic effect of membrane ACE2, and thus results in unopposed acute Ang II aggregation and local RAAS activation.74 During ACE2 downregulation, an accentuating RAAS imbalance may further exacerbate pathophysiological alteration in COVID-19.85,87

Immunopathogenesis

SARS-CoV-2 activates innate and acquired immune response, and further impairs the immune system and causes cytokine storm, which is an uncontrolled inflammatory response with elevations of circulating cytokine levels.73,88,89 The initial antiviral responses are promoted by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) detecting pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).90 Retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) is an interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene (ISG), and RIG-I-mediated signaling could promote induction of antiviral IFN responses.90,91 Recognition of virus promotes downstream transduction in nuclear factor-κB, IFN regulatory factor-3, and Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathways.92 Innate immune cells, such as parenchymal cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and macrophages, are stimulated to secrete inflammatory mediators.93 SARS-CoV-2 disturbs the immune system with its immune evasion strategies, in which viral PAMPs escape from the detection of cytosolic PRRs efficiently.94 The virus weakens the antiviral effects of ISG products through dysregulating IFN signaling and IFN generation.94,95 In acquired immunity, SARS-CoV-2 may target the CD147 spike protein of T lymphocytes.96 Viral peptides are presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) Class-I molecules to CD8+ T cells (cytotoxic T cells) to kill the virus directly, while by MHC Class-II molecules to CD4+ T cells (helper T cells).96,97 CD4+ T cells generate proinflammatory cytokines and mediators to facilitate other immune cells.88 B lymphocytes are directly stimulated by SARS-CoV-2 and interact with CD4+ T cells to produce substantial immunoglobulin G antibodies, which lead to the disruption of the virus and increased proinflammatory cytokines.14,96 Complement activation through classical or alternative pathways generates a number of chemotactic/inflammatory mediators.91 The release of proinflammatory cytokines also could be induced by increased A disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17 activity due to viral invasion.82 The cytokine storm, which is characterized by a radical rise in the number of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-6, IL-7, IL-10, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, IFN-γ-inducible protein 10, tumor necrosis factor-α, macrophage inflammatory protein-1α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, C–X–C motif ligand 9 (CXCL9), CXCL10, and CXCL11, triggers extensive tissue injury and body dysfunction and is considered as the primary contribution to mortality in COVID-19.32,33,97,98 Among these inflammatory cytokines/chemokines, IL-6 was reported to play a key role in COVID-19 cytokine storm development.89 However, a study found that only one cytokine, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, was significantly higher in COVID-19 patients than healthy controls. In addition, elevations of IL-6 were only found in some severe/critical patients and much less than patients with other cytokine storm syndrome-associated diseases.99 These controversial results pointed that SARS-CoV-2 causes a chemokine storm, not a cytokine storm, providing an interesting insight into COVID-19 immunopathogenesis.99 Genetically determined individual differences in immunity may relate to both variants in the immune-related genes and the inherent differences in the X- and Y-chromosome gene expressions.100,101

Autosomal loci and genes associated with COVID-19

2q24.2 and the interferon induced with helicase C domain 1 gene (IFIH1)

The IFIH1 protein is a primary PRR that first senses the coronavirus RNA and then triggers innate immunity and activates mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein.102 The variant rs1990760 (p.Ala946Thr) of the IFIH1 gene has been reported to be positively related to increased expression of the viral resistance gene IFIH1 and IFN-induced gene.103 This polymorphic variant in various ethnic populations is correlated with population migration and originated from the European and Asian populations. It is expected that rs1990760 T-allele confers carriers more resistance to COVID-19, e.g., Africans and African-Americans with low-frequency ranging from 0.06 to 0.35 have a more vulnerable risk for COVID-19 than Caucasians and Indians with an overall frequency of 0.56.102

3p21.31

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) conducted in Italy and Spain revealed that a 3p21.31 gene cluster comprised of the solute carrier protein family 6 member 20 gene (SLC6A20), the leucine zipper transcription factor like 1 gene (LZTFL1), the FYVE and coiled-coil domain autophagy adaptor 1 gene (FYCO1), the C–X–C motif chemokine receptor 6 gene (CXCR6), the X–C motif chemokine receptor 1 gene (XCR1), and the C-C motif chemokine receptor 9 gene (CCR9) is a genetically susceptible locus in severe COVID-19 patients with respiratory failure.104,105 The SLC6A20 gene encodes a transporter, signaling threshold regulating transmembrane adaptor, which functionally interacts with ACE2.105 The CXCR6 gene and the CCR9 gene encoding chemokine receptors are implicated in T cell differentiation and recruitment.95 Rs11385942 in the LZTFL1 gene associated with increased SLC6A20 expression and reduced CXCR6 expression is a risk variant and is common in Europeans, Africans, and South Asians, but almost absent in the East Asians.106

Another study suggests that a 49.4 kb haplotype in high linkage disequilibrium (LD) on 3p21.31 is the most highly correlated to severe COVID-19, and this core haplotype is thought to have entered the human population from the Neanderthals, an extinct hominin ~40,000 to 60,000 years ago.107,108 Neanderthal-derived core haplotype frequency varies significantly among populations that 63% of the Bengalese, ~30% of the South Asians, 8% of the Europeans, 4% of the Americans, a lower frequency of the East Asians, and almost none of the Africans carry this risk haplotype.109 This could explain that Briton-originated studies showed higher mortality in COVID-19 patients of Bangladeshi ethnicity (~2 times higher) and of South Asian descent.108,110 Correspondingly, mortality rates reported on 14 July 2020 in South Africa, Japan, South Korea, and China were substantially lower than the Western countries (in North America and West Europe).111 However, black individuals were at higher risk compared with white people in England and the United States.112–114 This paradoxical fact may be explained by the impacts of other genetic and environmental factors.

6p21.3 and HLA genotype

The HLA system containing nearly 27,000 alleles in classes I, II, and III is an exceedingly polymorphic region.115,116 Genetic variations across the HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DR, HLA-DP, and HLA-DQ genes, which encode MHC molecules, might change the process of viral infection by differentially mediating antiviral immunity.109,117 Several studies suggest that there may be specific risk and protective HLA alleles or haplotypes for COVID-19 incidence and mortality.9.

HLA-A and HLA-C were reported to have the relatively greatest and least capacities for presenting SARS-CoV-2, respectively, and HLA-B preferentially involves susceptibility to COVID-19.16,118 HLA-A*25:01, HLA-A*25:02, HLA-B*46:01, HLA-C*01:02, and HLA-B22 serotype, including HLA-B*54:01, HLA-B*55:01, HLA-B*55:07, HLA-B*55:12, and HLA-B*56:01, are weak presenters, and thus individuals with these alleles may be COVID-19 susceptible.118–120 HLA-A*02 subtypes such as HLA-A*02:02, HLA-A*02:03, HLA-A*02:05, HLA-A*02:06, HLA-A*02:09, HLA-A*02:11, HLA-A*02:12, HLA-A*02:22, HLA-A*02:24, HLA-A*02:35, and HLA-A*02:40, as well as HLA-A*24:02, HLA-B*15:03, HLA-B*52:01, HLA-C*12:02, and HLA-C*12:03, are strong presenters for SARS-CoV-2 epitopes and predicted to be protective.119,121,122 SARS-CoV-2 peptides presented by HLA-B*15:03 are common among human coronaviruses and enable cross-protective T cell-based immunity.120 HLA-A*02:01 has varying capacities for presenting SARS-CoV-2 antigens in different studies.15,117

Several studies concluded that HLA-A*25, HLA-B*08, HLA-B*15:01, HLA-B*15:27, HLA-B*27:07, HLA-B*44, HLA-B*51, HLA-C*01, HLA-C*03, HLA-C*04:01, HLA-DRB1*15:01, HLA-DQA1_509, HLA-DQB1*04, and HLA-DQB1*06:02 were associated with higher occurrence and mortality, while HLA-B*14, HLA-B*18, and HLA-B*49 showed an inverse log-linear relationship with COVID-19.123–127 HLA-A*11 was positively associated with COVID-19 mortality, but another analysis suggested that HLA-A*11:01 could generate efficient antiviral responses.115,117 HLA-DRB1*01:01 (severe 2.2% vs mild 0.5%), HLA-DRB1*14:04 (severe 2.0% vs mild 0.5%), and HLA-DQA1*01:01 (severe 2.9% vs mild 0.9%) are risk alleles for severe COVID-19, while HLA-DRB1*12:01 (severe 2.2% vs mild 3.7%) and HLA-DPB1*03:01 (severe 0.7% vs mild 4.5%) were protective.106 HLA-C*05 is significantly correlated to increased COVID-19 death risk and each increase of 1% in HLA-C*05 frequency is followed by an increase of 44 deaths/million. Its receptor KIR2DS4fl is located on natural killer (NK) cells and recognizes viral peptides bound to HLA-C*05 to generate a potent activation signal, leading to NK cell-induced hyperactive antiviral immunity jointly with HLA-C*05.9 Several South-East Asian and Oceania regions seem to correspond to higher predicted protective allele frequencies than other global regions based on data from the Allele Frequency Net Database (http://www.allelefrequencies.net/hla.asp; Supplementary Fig. S1, 2). HLA-A*24:02 was found to bind the peptide VYIGDPAQL, which is a virus helicase fragment shared between SARS-CoV-2 and two common cold coronaviruses, human coronavirus OC43 and HKU1. Thus, it was assumed that the anti-VYIGDPAQL T cells primed by previous OC43 or HKU1 infections could be restimulated after SARS-CoV-2 infection.128 HLA-A*24:02 allele carried by 25.5–98.0% of Chinese may partly explain the better epidemic prevention effect in China.

HLA is codominant and expresses all the alleles in the high gene density, complex LD, and homology regions.109,116 This suggests studying complete HLA genotypes for each individual rather than being limited to a few protective or harmful alleles as a wiser course.129 Haplotype HLA-A*11:01-B*51:01-C*14:02 was more common in severe COVID-19 patients than in mild ones.106 An Italian study found that haplotype HLA-A*01:01-B*08:01-C*07:01-DRB1*03:01 contributed to COVD-19 higher occurrence and mortality in northern Italy, while haplotype HLA-A*02:01-B*18:01-C*07:01-DRB1*11:04 closely linked to lower occurrence and mortality in central-southern Italy.130 A Sardinian study identified two haplotypes HLA-A*02:05-B*58:01-DRB1*08:01 and HLA-A*02:05-B*58:01-C*07:01 as being protective against severe COVID-19.123

Since COVID-19 vaccines may have variable binding affinities with different HLA genotypes in different populations, predicting good binders across certain HLA alleles may contribute to design an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine with corresponding epitope targets.131

9q34.2 and the ABO, alpha 1–3-N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase and alpha 1–3-galactosyltransferase gene (ABO)

A, B, and O blood groups possess A-antigen, B-antigen, and the biosynthetic precursor H-antigen, respectively.132,133 The antigen-encoding gene comprises A, B, and O alleles and is expressed in four genetic phenotypes.132 SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and survival following infection may relate to ABO blood groups. Individuals carrying blood group A have a higher COVID-19 risk, while blood group O exerts a relatively protective effect.132,134 In the blood group A, A-antigen causes more P-selectin and intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 attached to endothelial cells to increase cardiovascular disease likelihood. Blood group O individuals with ~25% decreased levels of von Willebrand factor might have lower thrombotic disease risk.134–136 In the blood group B, natural anti-A antibodies might exert a neutralizing activity blocking adhesion between S proteins and ACE2.133,134

The GATC haplotype rs8176746–rs8176740–rs495828–rs12683493, of which position is coincident with ABO locus, is common in people with non-O blood groups and positively correlated to ACE activity, while blood group O is characterized by intermediate ACE activity.135,137 Variants account for 15% of ACE activity variance, of which rs8176746 and rs495828 may independently reckon 2.8% and 4.9%, respectively.137–139 The ABO variant rs657152 was considered as a significant signal associating with severe COVID-19 in Italian and Spanish cohorts.104

9q34.3 and the dipeptidyl peptidase 7 gene (DPP7)

A 1-base pair (bp) insertion in the DPP7 gene destroying DPP7 transcription may have a potential monogenic effect for asymptomatic COVID-19 in a Chinese family analysis.106 DPP7 known as a survival factor to maintain lymphocytes quiescently may potentially involve in COVID-19 immunopathogenesis.140 The specific functional effects of the DPP7 gene in COVID-19 still need further clarification.

11p15.5 and the interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 gene (IFITM3)

The rs12252 C-allele homozygosity in the IFITM3 gene relates to COVID-19 patient disease severity, and CC-homozygote patients have a 6.37 times higher risk of severity after a SARS-CoV-2 infection.141–143 This association is not thought to stem directly from rs12252, but from a functional variant existing LD with rs12252 of IFITM3 or a nearby gene.144 Rs34481144 A-allele (38–56% in Europeans, 2–14% in Africans, and 1–2% in Chinese) might increase COVID-19 susceptibility by triggering methylation of the IFITM3 promoter to decrease IFITM3 mRNA expression in CD8+ T cells and depressing surrounding gene transcription.145,146

12q24.33 and the golgin A3 gene (GOLGA3)

Pedigree analysis of Chinese suggested the splice acceptor variant rs143359233 in the GOLGA3 gene potentially implicated in critically ill COVID-19 patients as a monogenic factor.106 The GOLGA3 gene encodes a Golgi complex-associated protein, which participates in protein transportation, cell apoptosis, Golgi positioning, and spermatogenesis.147 Its defect was proved to lead to male infertility previously, but the reliable relationship between the GOLGA3 gene and COVID-19 remains uncertain.147 GOLGA3 may implicate COVID-19 severity by influencing the interaction of SARS-CoV-2 to innate immune pathways.148

13q12.3 and the high mobility group box 1 gene (HMGB1)

The HMGB1 gene encodes a DNA-binding protein, which is a critical damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) and probably regulates a proviral gene expression program. HMGB1 may interact with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the advanced glycosylation end-product specific receptor to induce cytokine storm in immune cells and ACE2 expression in alveolar epithelial cells, further increasing COVID-19 susceptibility.149,150

15q26.1 and the FURIN gene

The FURIN gene encodes a ubiquitous membrane-bound pro-protein convertase that cleaves the SARS-CoV-2 S protein into the S1 and S2 subunits. Two highly frequent FURIN variants relating to upregulated FURIN in Africans, rs6226 (93%) and rs8039305 (81%), are associated with increased hypertension risk and SARS-CoV-2 infection.151 A common variant, rs4702, may directly reduce SARS-CoV-2 infection. The variant rs769208985 (p.Arg298Gln), representing glutamine residue by replacing arginine in a highly conserved position (R298), might influence FURIN recognition of the SARS-CoV-2 S protein.20,70

17q23.3 and the ACE gene

The insertion of an Alu repeat element into ACE intron 16 may result in alternative splicing in which the ACE I-allele leads to protein shortening and the loss of a catalytically active protein domain, while the ACE D-allele still maintains two active protein domains catalyzing Ang I to Ang II.152,153 Approximately 60% of ACE level variability in general populations is likely to be determined by the ACE I/D variant.154,155 The I/D variant is associated with ACE circulating and tissue concentrations, which means that ACE activity levels in I/I carriers are about half of that of D/D carriers.87,156 COVID-19 variable recovery and prevalence rates correlate to the ratio of the ACE I/D allele frequency and the geographical variations of the ACE I/D variant.157,158

The racial difference in the ACE gene polymorphism is well understood. According to the “thrifty genotype” hypothesis put forward by J.V. Neel, after modern human ancestors expanded out of Africa ~200,000 years ago, genetic variation of the D-allele occurred as the D-allele favoring the retention of salt and water became detrimental.159 Middle Eastern populations, particularly those in Lebanon with a relatively low I-allele frequency, are believed to be the ancestor of the ACE variant.86 I/I genotype increases westwards and eastwards from the Middle East. The distribution of D-allele is characterized by the highest frequency of D-allele in Africa and Arab regions, medium frequencies in Europe, Australia, and America, and the lowest frequency in East Asia.159 Therefore, the higher recovery rate in East Asians and disproportionately higher fatality rate in African Americans are unsurprising.155,158

19q13.32 and the apolipoprotein E gene (APOE)

The APOE gene has three common alleles, ε2, ε3, and ε4, which are haplotypes of rs429358 and rs7412.160,161 Compared to the most common APOE ε3ε3 genotype, individuals who are homozygous for APOE ε4 have twice the risk of severe COVID-19, although mortalities between APOE ε3ε4 and ε3ε3 COVID-19-positive subjects have no significant difference.162,163 The APOE ε4ε4 homozygous genotype might have a higher risk of severe COVID-19 due to regulating proinflammatory pathways and lipoprotein function being affected.161,163 An African-American ε4-allele frequency of 29.5% compared to a Caucasian rate of 12.1% may explain the diverse mortalities.162

21q22.3 and the TMPRSS2 gene

The TMPRSS2 gene variants may play a significant role in the interindividual differences particularly in the gender-related bias of COVID-19 susceptibility and severity.164 Rs61299115, rs4303794, and rs11088551 have relatively high frequencies in the general populations (25–36%), but much lower, 2%, in East Asian populations. They potentially enhance TMPRSS2 transcription, and thus the rarity of these three single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) among the East Asians results in lower TMPRSS2 expression levels.165 Rs12329760 (p.Val197Met) located at the exonic splicing enhancer site might considerably increase the TMPRSS2 faulty expression, weaken TMPRSS2 stability, and inhibit S protein and ACE2 interaction, which may contribute to asymptomatic and mild patients in Chinese with higher variant frequency.166 However, in Italian populations, rs12329760, as well as a haplotype rs2070788–rs9974589–rs7364083–rs8134378, trigger increased TMPRSS2 expression and may explain the higher mortality rate among the Italians with higher variant frequency.167 Rs8134378 close to an androgen-responsive enhancer possibly increases the TMPRSS2 gene expression in males in an androgen-specific manner and is co-regulated with a “European” haplotype rs463727–rs34624090–rs55964536–rs734056–rs4290734–rs34783969–rs11702475–rs35899679–rs35041537.168 The variants rs2070788, rs464397, rs469390 (p.Val379Ile), and rs383510 could upregulate TMPRSS2 expression in lung tissue and have lower frequencies in East Asians than Africans, Europeans, and Americans, which might explain the different COVID-19 susceptibilities in different populations.169,170 Conversely, p.Asp435Tyr only presenting at a low frequency in Europeans leads to the lack of a key residue catalyzing substrate binding.171

X- or Y-linked loci and genes associated with COVID-19

Consistent with Lyon’s theory, X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), which occurs in females in the late blastocyst stage, is a fundamental event in the epigenetic gene regulation that one of the X chromosomes is stochastically inactivated to equal X-linked gene dosage between genders.167,172–174 Two noncoding RNAs control this complex inactivation process, which condenses one X chromosome into a compact structure, Barr body, and maintains an active X chromosome simultaneously. Approximately 15–30% of X-linked genes, most are on the short arm (p), can escape from the XCI.172,175 Interestingly, XCI is cell-specific such that some cells express the maternal copy, while others express the paternal copy, and escape from XCI can be variable between individuals, among cells in a tissue, and during growth and aging.176,177 The skewed XCI may bypass the deleterious X-linked variants in females, while any abnormal gene variants on the X chromosome of males are more likely to express phenotypically and to cause more pronounced consequences due to hemizygosity.160,175,178,179 This appears to explain SARS-CoV-2 infection rate gender bias.

Xp22.2 and the TLR7 gene

The TLR7 gene encodes a Toll-like receptor that could recognize SARS-CoV-2 RNA and trigger the antiviral response.180 An analysis performed on two young brother pairs with severe COVID-19 identified a maternally inherited variant rs2042915990 (p.Gln710Argfs*18) and a missense variant rs200553089 (p.Val795Phe) as rare loss-of-function (LOF) variants in the TLR7 gene, which result in immunodeficiencies in type I and II interferon responses.181 Further, a nested case–control study identified the TLR7 gene variants p.Ser301Pro, rs189681811 (p.Arg920Lys), and rs147244662 (p.Ala1032Thr) as LOF variants, which in young, male, severe COVID-19 patients were considered to account for COVID-19 susceptibility in up to 2% cases.182

Xp22.22 and the ACE2 gene

The ACE2 gene encoding a dipeptidyl carboxydipeptidase with 805 amino acids is a putative risk factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection.72,183 ACE2 contains a potential N-terminal signal peptide, a peptidase domain, and a C-terminal collectrin-like domain, which ends with the single transmembrane helix. A ferredoxin-like fold “Neck” domain is between the peptidase domain and transmembrane helix. The crucial roles of the peptidase and neck domains (residues 19–726) in the ACE2 homodimerization allow for positing that variants affecting these amino acid residues may influence viral infection.184–187

Up to the date of this writing, no genetically monogenic, naturally resistant ACE2 mutations which counter S protein binding have been reported.188 However, a number of ACE2 variants may influence COVID-19 susceptibility and outcomes via three primary routines: (1) alterations of ACE2-binding properties to sirtuin 1, which regulates transcriptional and post-translational modifications of the ACE2 gene, (2) alteration of the soluble ACE2 levels in circulation and the affinity and density of ACE2 for the S protein, and (3) alteration of circulating Ang-(1–7), which causes a greater marked RAAS imbalance and greater disease severity.80,87,185,189

Among the most significant variants for ACE2 activity and levels, the most frequent is the transition rs2285666 (G8790A).152,190 The A-allele carriers may have higher serum ACE2 levels than the G-allele carriers, of which A/A genotype had almost 50% higher ACE2 expression levels than the G/G genotype.191,192 Rs2285666 located in the intronic-consensus splice site region might theoretically affect the processing of total RNA to mRNA with alternative splicing mechanisms and further the amount of protein.193 The transition G8790A was predicted to lead to ~9.2% increased strength of the splice site and further elevated ACE2 serum levels.192 Accordingly, rs2285666 is suggested to be a protective variant to COVID-19, and lower morbidity and mortality in Indians could be explained by the A-allele of rs2285666.193 The variant rs2106809 reported in Indians and Saudi Arabians may primarily influence serum ACE2 levels, and that the C/C or C/T genotype has comparatively higher levels than the T/T genotype.166

Rs4646114 and rs4646115, which are more prevalent in African descent populations with frequencies of 5.0–7.2% and 1.4–1.8%, could accelerate viral infection and spread, and thus may associate with higher COVID-19 susceptibility.165 Rs4646116 (p.Lys26Arg), which is quite frequent in Caucasians, but has not yet been detected in the East-Asian populations, activates ACE2 and boosts binding to S protein, while rs191860450 (p.Ile468Val), which is more prevalent in Asians, may alter the ACE2–S protein interaction characteristics, but the significance of this is unclear.183,194 The variant p.Arg514Gly, located in the AGT–ACE2 interaction surface, was predicted to increase COVID-19 risk by altering RAAS function.171 The higher COVID-19 mortality in Italy may be partly explained by the role of rs41303171 (p.Asn720Asp), which is more prevalently carried by Italians, in promoting TMPRSS2 cleaving and viral intake.195

The variants rs73635825 (p.Ser19Pro) and rs766996587 (p.Met82Ile) exclusively presented in Africans may reduce encoded protein stability and binding affinity to S protein binding sites.4,8,196 The European-specific variant rs1448326240 (p.Glu239His) is thought to be an interaction-inhibiting variant and lead to a lower SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility.184 Rs143936283 (p.Glu329Gly) has a lower binding affinity for the S protein, implying that rs143936283 may confer a lower probability of viral attachment and some level of resistance against infection.195 The variants p.Leu351Val and rs762890235 (p.Pro389His), which occur in the ACE2–S protein interaction region, are predicted to interfere with the internalization process.197 Rs961360700 (p.Asp355Asn) and rs1396769231 (p.Met383Thr) were also predicted to adversely affect ACE2 stability.196 The four variants located in the ACE2 dimeric interface, p.Arg708Trp, p.Arg710Cys, p.Arg710His, and p.Arg716Cys, could affect ACE2 cleavage by TMPRSS2 and change the dimer formation, which may be responsible for the milder COVID-19 symptoms in Europeans having these four variants.171

Heterogeneous ACE2 expression in different ethnic groups might be a measure of differential population reactions to COVID-19. For example, Asians have a higher ACE2 expression than African Americans and Caucasians. The expression quantitative loci for upregulating ACE2 can be up to almost 100% in East Asians, which are over 30% higher than other racial groups.185,198 The prevalence of ACE2-downregulating variants is 54% in non-Finnish Europeans, 39% in Africans/African Americans, and 2–10% in Latinos/admixed Americans, East Asians, Finns, and South Asians, while Amish and Ashkenazi Jewish populations seem to carry none of such variants.171 Highly penetrant dominant trait presenting in the ACE2 gene probably affects familial clusters.10 Approximately 320–365 out of every 100,000 humans possess SNVs decreasing spike binding, while 4–12 of every 100,000 humans possess SNVs increasing spike binding. Specific SNVs affecting S protein binding are more abundant in individuals of a certain ancestry, and this frequency may vary six-fold between different ancestries.199

Furthermore, the ACE2 gene, mapped at the pseudoautosomal regions of X-chromosome, could escape XCI more probably, which likely confers females a double ACE2 dosage to compensate for the loss of membrane ACE2 due to SARS-CoV-2.175,178 One study showed that, in the hemizygous state, >50% of the variants probably influence the binding of the human ACE2 and the viral S1 protein.184 ACE2 interaction-booster and interaction-inhibitor variants can be more significant in males and the former may result in a higher mortality rate in males than females.100 The fact that the ACE2 gene expression could be elevated in females due to a skewed XCI, providing a larger ACE2 pool to maintain the fundamental balance of RAAS-regulatory axis in multiple organs after viral infection, could partly explain the lower frequency of severe COVID-19 in females than males.17,172

Xq12 and the androgen receptor gene (AR)

The 15-bp AR binding element is the critical part of the TMPRSS2 promoter for androgen’s binding and its transcription regulation.200,201 This AR element is a polymorphic unit with CAG trinucleotide repeat length variations in the AR gene’s first exon.202 Length variation can determine both transcriptional activity and androgen resistance strength that shorter CAG repeat polymorphism may lead to TMPRSS2 overexpression and link to androgen sensitivity, as well as more severe COVID-19.176 The variation of greater COVID-19 mortality in males than females or infants of either gender may be explained by androgen-mediated ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expressions.101,200,203 Ethnicity-based vulnerability may be explained by the AR gene polymorphisms that African-American males with shorter CAG repeat lengths have a disproportionate mortality rate than non-Hispanic white males.201,202

Conclusions and perspectives

The world is still suffering from the COVID-19 outbreak and the ultimate outcomes are, so far, unmeasurable, but the global economic, social, and political disruptions caused by this pandemic are poised to worsen in the foreseeable future.11,204 Therefore, understanding the causal relationships between host genetic basis and COVID-19 is urgently needed to identify biomarkers for individuals at high risk, which might also provide potential targets for therapy.6,98 Focusing on these variants, which relate to disease susceptibility and severity through viral trafficking pathways or drug curative effect, could better identify risk subjects and effectively control the disease. Large data consortiums are organizing to produce, share, and analyze data, such as the COVID19 Host Genetics Initiative and the COVID Human Genetic Effort.12,205 As more host genetic factors associated with COVID-19 are identified, it should become possible to create tests that would predict the susceptible populations and allow for classifying and safeguarding them.190 In summary, we extract and review positive results from vast reported papers. However, for a certain variant, large-scale meta-analyses combining data from multiple consistent studies with reliable statistical significance would be helpful to find therapy targets.

Ongoing investigations into COVID-19 and individual genetic makeup are fueling global research to develop vaccines, prioritize individuals for treatment, and discover potential drug target candidates.95 The antiviral drug Veklury (remdesivir) is the first and the only treatment for COVID-19 approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (https://www.fda.gov). Given that remdesivir is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug, better direct-target-based antiviral therapies that intervene in SARS-CoV-2-infected pathways are anticipated.206 Human genetic basis of COVID-19, which is well known to impact disease susceptibility and severity, may offer novel insights into COVID-19 therapies and controls through identifying particular genes and pathways. Large-scale screening of potential targeted drugs and experimental therapeutic studies would be helpful to develop new drugs or discover repurposing opportunities for existing drugs.148 In order to end this century nightmare early, when it comes to ethical considerations and/or societal questions, further investigations should pay attention to (1) ensuring the validity and usefulness of the reported studies, (2) not undermining the necessity of solidarity in the public health action, (3) not affecting individuals’ action ability or making them be discrimination targets, and (4) perfecting genetic information-related legislation.207

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all the participants of our study. This work was supported by the Special Emergency Project for Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia from the Science and Technology Department of Hunan Province (2020SK3032).

Author contributions

H.D., X.Y., and L.Y. contributed equally to researching data for the article, discussions of the content, and writing the manuscript. H.D. and L.Y. contributed to reviewing and editing the manuscript before submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Hao Deng, Xue Yan.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41392-021-00736-8.

References

- 1.Yoo JH. The fight against the 2019-nCoV outbreak: an arduous march has just begun. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020;35:e56. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020;55:105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ravaioli S, et al. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 potential involvement in genetic susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 in cancer patients. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:963689720968749. doi: 10.1177/0963689720968749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorbalenya AE, et al. The species severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu J, Li C, Wang S, Li T, Zhang H. Genetic variants are identified to increase risk of COVID-19 related mortality from UK biobank data. Hum. Genomics. 2021;15:10. doi: 10.1186/s40246-021-00306-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zbinden-Foncea H, Francaux M, Deldicque L, Hawley JA. Does high cardiorespiratory fitness confer some protection against proinflammatory responses after infection by SARS-CoV-2? Obesity. 2020;28:1378–1381. doi: 10.1002/oby.22849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calcagnile M, et al. Molecular docking simulation reveals ACE2 polymorphisms that may increase the affinity of ACE2 with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Biochimie. 2021;180:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sakuraba A, Haider H, Sato T. Population difference in allele frequency of HLA-C*05 and its correlation with COVID-19 mortality. Viruses. 2020;12:1333. doi: 10.3390/v12111333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ikitimur H, et al. Determining host factors contributing to disease severity in a family cluster of 29 hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 patients: could genetic factors be relevant in the clinical course of COVID-19? J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:357–365. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rajarshi K, et al. Essential functional molecules associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection: potential therapeutic targets for COVID-19. Gene. 2021;768:145313. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ovsyannikova IG, Haralambieva IH, Crooke SN, Poland GA, Kennedy RB. The role of host genetics in the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 susceptibility and severity. Immunol. Rev. 2020;296:205–219. doi: 10.1111/imr.12897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams FMK, et al. Self-reported symptoms of COVID-19, including symptoms most predictive of SARS-CoV-2 infection, are heritable. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2020;23:316–321. doi: 10.1017/thg.2020.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal H, et al. An assessment on impact of COVID-19 infection in a gender specific manner. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2021;17:94–112. doi: 10.1007/s12015-020-10048-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao J, et al. Relationship between the ABO blood group and the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) susceptibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021;73:328–331. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen, A. et al. Human leukocyte antigen susceptibility map for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. J. Virol. 94 e00510–20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Gómez J, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzymes (ACE, ACE2) gene variants and COVID-19 outcome. Gene. 2020;762:145102. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.145102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahimi A, Mirzazadeh A, Tavakolpour S. Genetics and genomics of SARS-CoV-2: a review of the literature with the special focus on genetic diversity and SARS-CoV-2 genome detection. Genomics. 2021;113:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nascimento VAD, et al. Genomic and phylogenetic characterisation of an imported case of SARS-CoV-2 in Amazonas State, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2020;115:e200310. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760200310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobrindt K, et al. Common genetic variation in humans impacts in vitro susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16:505–518. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jutzeler CR, et al. Comorbidities, clinical signs and symptoms, laboratory findings, imaging features, treatment strategies, and outcomes in adult and pediatric patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;37:101825. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pormohammad A, et al. Clinical characteristics, laboratory findings, radiographic signs and outcomes of 61,742 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microb. Pathog. 2020;147:104390. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shu T, et al. Plasma proteomics identify biomarkers and pathogenesis of COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;53:1108–1122.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu L, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020;80:656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong CKH, Wong JYH, Tang EHM, Au CH, Wai AKC. Clinical presentations, laboratory and radiological findings, and treatments for 11,028 COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:19765. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74988-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;94:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li LQ, et al. COVID-19 patients’ clinical characteristics, discharge rate, and fatality rate of meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:577–583. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghayda RA, et al. Correlations of clinical and laboratory characteristics of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:5026. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17145026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chua TH, Xu Z, King NKK. Neurological manifestations in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Inj. 2020;34:1549–1568. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2020.1831606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makhoul K, Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease after COVID-19. J. Neurol. Sci. 2021;422:117331. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J. Pediatr. 2020;87:281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harrison AG, Lin T, Wang P. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 transmission and pathogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2020;41:1100–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hossain MF, et al. COVID-19 outbreak: pathogenesis, current therapies, and potentials for future management. Front. Pharm. 2020;11:563478. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.563478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simoneau CR, Ott M. Modeling multi-organ infection by SARS-CoV-2 using stem cell technology. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:859–868. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu J, Wang Y. The clinical characteristics and risk factors of severe COVID-19. Gerontology. 2021;6:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000513400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kronbichler A, et al. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;98:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan S, et al. CT manifestations and clinical characteristics of 1115 patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Radiol. 2020;27:910–921. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang H, Lan Y, Yao X, Lin S, Xie B. The chest CT features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a meta-analysis of 19 retrospective studies. Virol. J. 2020;17:159. doi: 10.1186/s12985-020-01432-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muhammad SZ, et al. Chest computed tomography findings in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infez. Med. 2020;28:295–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu F, et al. A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020;579:265–269. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Khomari F, Nabi-Afjadi M, Yarahmadi S, Eskandari H, Bahreini E. Effects of cell proteostasis network on the survival of SARS-CoV-2. Biol. Proced. Online. 2021;23:8. doi: 10.1186/s12575-021-00145-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.V’kovski P, Kratzel A, Steiner S, Stalder H, Thiel V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19:155–170. doi: 10.1038/s41579-020-00468-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bzówka M, et al. Structural and evolutionary analysis indicate that the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is a challenging target for small-molecule inhibitor design. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3099. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adedokun KA, Olarinmoye AO, Mustapha JO, Kamorudeen RT. A close look at the biology of SARS-CoV-2, and the potential influence of weather conditions and seasons on COVID-19 case spread. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2020;9:77. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00688-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen L, et al. RNA based mNGS approach identifies a novel human coronavirus from two individual pneumonia cases in 2019 Wuhan outbreak. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:313–319. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1725399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou P, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shereen MA, Khan S, Kazmi A, Bashir N, Siddique R. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res. 2020;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morawska L, Milton DK. It is time to address airborne transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;71:2311–2313. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jin YH, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil. Med. Res. 2020;7:4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, et al. Transmission and prevention of SARS-CoV-2. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2020;48:2307–2316. doi: 10.1042/BST20200693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vivanti AJ, et al. Transplacental transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:3572. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17436-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khalaf K, et al. SARS-CoV-2: pathogenesis, and advancements in diagnostics and treatment. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:570927. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.570927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morawska L, Cao J. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: the world should face the reality. Environ. Int. 2020;139:105730. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bai Y, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frampton, D. et al. Genomic characteristics and clinical effect of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage in London, UK: a whole-genome sequencing and hospital-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 1246–1256 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Zhao S, et al. Inferring the association between the risk of COVID-19 case fatality and N501Y substitution in SARS-CoV-2. Viruses. 2021;13:638. doi: 10.3390/v13040638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Galloway SE, et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 lineage-United States, December 29, 2020-January 12, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021;70:95–99. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7003e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Q, et al. Structural and functional basis of SARS-CoV-2 entry by using human ACE2. Cell. 2020;181:894–904.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hoffmann M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zipeto D, Palmeira JDF, Argañaraz GA, Argañaraz ER. ACE2/ADAM17/TMPRSS2 interplay may be the main risk factor for COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:576745. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.576745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smatti MK, Al-Sarraj YA, Albagha O, Yassine HM. Host genetic variants potentially associated with SARS-CoV-2: a multi-population analysis. Front. Genet. 2020;11:578523. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.578523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu C, von Brunn A, Zhu D. Cyclophilin A and CD147: novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of COVID-19. Med. Drug Discov. 2020;7:100056. doi: 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang S, et al. AXL is a candidate receptor for SARS-CoV-2 that promotes infection of pulmonary and bronchial epithelial cells. Cell Res. 2021;31:126–140. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00460-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ibrahim IM, Abdelmalek DH, Elshahat ME, Elfiky AA. COVID-19 spike-host cell receptor GRP78 binding site prediction. J. Infect. 2020;80:554–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vankadari N, Wilce JA. Emerging COVID-19 coronavirus: glycan shield and structure prediction of spike glycoprotein and its interaction with human CD26. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020;9:601–604. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1739565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Daniloski Z, et al. Identification of required host factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection in human cells. Cell. 2021;184:92–105.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Latini A, et al. COVID-19 and genetic variants of protein involved in the SARS-CoV-2 entry into the host cells. Genes. 2020;11:1010. doi: 10.3390/genes11091010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li ZL, Buck M. Neuropilin-1 assists SARS-CoV-2 infection by stimulating the separation of spike protein domains S1 and S2. Biophys. J. 2021;120:2828–2837. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2021.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verdecchia P, Cavallini C, Spanevello A, Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rodríguez C, et al. Pulmonary endothelial dysfunction and thrombotic complications in COVID-19 patients. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020;64:407–415. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2020-0359PS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vaduganathan M, et al. Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1653–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr2005760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Medina-Enríquez MM, et al. ACE2: the molecular doorway to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:148. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00519-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Warner FJ, Smith AI, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme-2: a molecular and cellular perspective. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2004;61:2704–2713. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4240-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bader M, Ganten D. Update on tissue renin-angiotensin systems. J. Mol. Med. 2008;86:615–621. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Donoghue M, et al. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) converts angiotensin I to angiotensin 1-9. Circ. Res. 2000;87:e1–e9. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Patel VB, Zhong JC, Grant MB, Oudit GY. Role of the ACE2/angiotensin 1-7 axis of the renin-angiotensin system in heart failure. Circ. Res. 2016;118:1313–1326. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.307708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sieńko J, et al. COVID-19: the influence of ACE genotype and ACE-I and ARBs on the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in elderly patients. Clin. Inter. Aging. 2020;15:1231–1240. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S261516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hamming I, et al. The emerging role of ACE2 in physiology and disease. J. Pathol. 2007;212:1–11. doi: 10.1002/path.2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haitao T, et al. COVID-19 and sex differences: mechanisms and biomarkers. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020;95:2189–2203. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burrell LM, Johnston CI, Tikellis C, Cooper ME. ACE2, a new regulator of the renin-angiotensin system. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004;15:166–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vickers C, et al. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:14838–14843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200581200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cheng H, Wang Y, Wang GQ. Organ-protective effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 and its effect on the prognosis of COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:726–730. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yamamoto N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 mortalities strongly correlate with ACE1 I/D genotype. Gene. 2020;758:144944. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Arnold RH. COVID-19-does this disease kill due to imbalance of the renin angiotensin system (RAS) caused by genetic and gender differences in the response to viral ACE2 attack? Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:964–972. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mangalmurti N, Hunter CA. Cytokine storms: understanding COVID-19. Immunity. 2020;53:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang L, et al. COVID-19: immunopathogenesis and immunotherapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:128. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Molaei S, Dadkhah M, Asghariazar V, Karami C, Safarzadeh E. The immune response and immune evasion characteristics in SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2: vaccine design strategies. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021;92:107051. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mohamed Khosroshahi L, Rokni M, Mokhtari T, Noorbakhsh F. Immunology, immunopathogenesis and immunotherapeutics of COVID-19; an overview. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021;93:107364. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Catanzaro M, et al. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020;5:84. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ebrahimi N, et al. Recent findings on the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19); immunopathogenesis and immunotherapeutics. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020;89:107082. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kumar, S., Nyodu, R., Maurya, V. K. & Saxena, S. K. in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Therapeutics (ed. Saxena, S. K.) Ch. 5 (Springer Singapore, 2020).

- 95.Schurr TG. Host genetic factors and susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2020;32:e23497. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.23497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Azkur AK, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75:1564–1581. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dhama K, et al. An update on SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 with particular reference to its clinical pathology, pathogenesis, immunopathology and mitigation strategies. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020;37:101755. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ramos-Lopez O, et al. Exploring host genetic polymorphisms involved in SARS-CoV infection outcomes: implications for personalized medicine in COVID-19. Int. J. Genomics. 2020;2020:6901217. doi: 10.1155/2020/6901217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Syed F, et al. Excessive matrix metalloproteinase-1 and hyperactivation of endothelial cells occurred in COVID-19 patients and were associated with the severity of COVID-19. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;224:60–69. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.von der Thüsen J, van der Eerden M. Histopathology and genetic susceptibility in COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2020;50:e13259. doi: 10.1111/eci.13259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020;11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Maiti AK. The African-American population with a low allele frequency of SNP rs1990760 (T allele) in IFIH1 predicts less IFN-beta expression and potential vulnerability to COVID-19 infection. Immunogenetics. 2020;72:387–391. doi: 10.1007/s00251-020-01174-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Molineros JE, et al. Admixture mapping in lupus identifies multiple functional variants within IFIH1 associated with apoptosis, inflammation, and autoantibody production. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003222. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ellinghaus D, et al. Genomewide association study of severe COVID-19 with respiratory failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1522–1534. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ellinghaus, D. et al. The ABO blood group locus and a chromosome 3 gene cluster associate with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory failure in an Italian-Spanish genome-wide association analysis. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/early/2020/06/02/2020.05.31.20114991 (2020).

- 106.Wang F, et al. Initial whole-genome sequencing and analysis of the host genetic contribution to COVID-19 severity and susceptibility. Cell Discov. 2020;6:83. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00231-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zeberg H, Pääbo S. The major genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 is inherited from Neanderthals. Nature. 2020;587:610–612. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2818-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nelson R. Risk variant for severe COVID-19 inherited from Neanderthals. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2020;182:2203–2204. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kwok AJ, Mentzer A, Knight JC. Host genetics and infectious disease: new tools, insights and translational opportunities. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021;22:137–153. doi: 10.1038/s41576-020-00297-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Patel P, Hiam L, Sowemimo A, Devakumar D, McKee M. Ethnicity and covid-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m2282. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sornette D, Mearns E, Schatz M, Wu K, Darcet D. Interpreting, analysing and modelling COVID-19 mortality data. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020;101:1751–1776. doi: 10.1007/s11071-020-05966-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Williamson EJ, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rentsch CT, et al. Patterns of COVID-19 testing and mortality by race and ethnicity among United States veterans: a nationwide cohort study. PLoS Med. 2020;17:e1003379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323:2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lorente L, et al. HLA genetic polymorphisms and prognosis of patients with COVID-19. Med. Intens. 2021;45:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.La Porta CAM, Zapperi S. Estimating the binding of SARS-CoV-2 peptides to HLA class I in human subpopulations using artificial neural networks. Cell Syst. 2020;11:412–417. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]