Key summary points

Aim

The aim of the study is to determine the factors influencing the outcomes of older ventilated medical patients in a large tertiary medical center.

Findings

Of 554 older patients (mean age 79 years) who underwent mechanical ventilation for the first time during the study period in-hospital mortality was 64.1% and overall 6-months survival was 26%. A combination of age 85 years and older, poor functional status prior to ventilation, and associated morbidity were the strongest negative predictors of survival after discharge from the hospital.

Message

The identification of factors predicting poor survival of mechanical ventilation will assist policy makers in clinical decision-making particularly at times of limited health resources.

Keywords: Aging, Mechanical ventilation, Internal medicine, Survival

Abstract

Background

The development of technologies for the prolongation of life has resulted in an increase in the number of older ventilated patients in internal medicine and chronic care wards. Our study aimed to determine the factors influencing the outcomes of older ventilated medical patients in a large tertiary medical center.

Methods

We performed a prospective observational cohort study including all newly ventilated medical patients aged 65 years and older over a period of 18 months. Data were acquired from computerized medical records and from an interview of the medical personnel initiating mechanical ventilation.

Results

A total of 554 patients underwent mechanical ventilation for the first time during the study period. The average age was 79 years, and 80% resided at home. Following mechanical ventilation, 8% died in the emergency room, and the majority of patients (351; 63%) were hospitalized in internal medicine wards. In-hospital mortality was 64.1%, with 48% dying during the first week of hospitalization. Overall 6-months survival was 26%. We found that a combination of age 85 years and older, functional status prior to ventilation, and associated morbidity (diabetes with target organ injury and/or oncological solid organ disease) were the strongest negative predictors of survival after discharge from the hospital.

Conclusion

Mechanical ventilation at older age is associated with poor survival and it is possible to identify factors predicting survival. In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings of this study may help in the decision-making process regarding mechanical ventilation for older people.

Introduction

Technological developments have made an important impact on improving health care and prolonging life. Mechanical ventilation for advanced respiratory support is now widely available. The growing number of acute patients requiring mechanical ventilation places an increasing burden on limited high-cost Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds. Although the age structure in Israel is still relatively young, there is a marked increase in the number of people of more advanced old age [1]. As a result, Israel has witnessed a rise in the number of older ventilated patients which has greatly surpassed the availability of ICU beds, the consequence of which is that the majority of ventilated patients are now treated in special units within Internal Medicine wards.

Many studies have sought to examine the causative factors resulting in mechanical ventilation, and to determine the outcomes of this intervention. The majority of these studies were conducted in the ICU setting [2–7]. Many studies show higher mortality and poorer outcomes in older patients [8]. Nevertheless, several studies found that age was not an independent predictor of mortality [9]. It has been suggested that it is not advanced age per se that determines prognosis in older patients but rather other age-related factors, such as comorbidities and physical and cognitive function [10–12].

Relatively few studies have included patients treated by mechanical ventilation outside the ICU [13–16]. These studies were largely designed to compare the outcomes of those treated in ICUs with those who were not managed in ICU to determine which patients are likely to most benefit from ICU admission [3].

The decision to proceed to mechanical ventilation for older critically ill patients has important ramifications not only for patients and their families, but also for the health care system. This is of particular interest in the legal, religious and cultural milieu of Israel. The religious principle of the holiness of life in Judaism and Islam makes many patients and family decision makers request ventilation at all cost, and legal requirements forbid the discontinuation of life-maintaining interventions such as mechanical ventilation. These factors have resulted in an increase in the number of people treated by chronic mechanical ventilation in special long-term units. Obviously, better clinical prognostication for critically ill older patients is required prior to mechanical ventilation and advanced life support. Apart from the personal unfavorable consequences of mechanical ventilation in older patients with underlying untreatable disease, the economic demands placed on a health system that is battling to finance current needs have major implications on both acute and chronic care settings.

The scope of our study was to investigate the decision-making process at the initiation of mechanical ventilation and the natural history of a study population comprising all mechanically ventilated older medical patients in a large acute tertiary care medical center.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

This was a prospective, observational cohort study performed at the Rambam Health Care Campus, a 1000-bed tertiary hospital in Haifa, Israel. We included all medical patients aged 65 years and older who underwent tracheal intubation with mechanical ventilation during the study period for indications unrelated to trauma and/or surgical interventions. For those patients who were successfully weaned from the initial mechanical ventilation and who then underwent a repeat tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation during the study period, the second event was excluded from the study. Patients who had a permanent tracheostomy were included in the study if they were mechanically ventilated during hospitalization. We also included patients who underwent tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation during the course of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the emergency medicine unit or in the internal medicine wards and who died soon after the event. The investigators were not involved in the decision to ventilate the patients. Survival was determined for up to 2 years following the initiation of ventilation. The study was approved by the Committee for Research in Human Subjects (the Helsinki Committee) of the Rambam Health Care Campus, and the need for informed patient consent was waived for this study.

Questionnaire and data collection

Data were collected from computerized hospital records and from a questionnaire administered by a study nurse to the physician or paramedic who was directly involved in the decision to intubate and ventilate the patient. The collected data included age, gender, Charlson comorbidity index, main diagnoses (based on ICD-9 classification), place of residence prior to admission (home, assisted living, nursing home, geriatric hospital or other in-patient facility), baseline functional status (independent, frail, nursing care), laboratory investigations (hemoglobin, hematocrit, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, albumin, sodium, potassium, calcium) and the Norton Pressure Ulcer Prediction Scale [17].

With regard to the initiation of mechanical ventilation, we determined when the ventilation was commenced, who had made the decision to ventilate (physician or paramedic) and where the decision was made (patient’s home, nursing home, geriatric hospital, emergency medicine unit or in-patient unit). The presence of advanced directives was ascertained, and the physician or paramedic was asked whether the decision to ventilate had been made following a prior discussion with the patient and/or family members.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate analysis of factors associated with in-hospital mortality was performed by logistic regression, followed by multivariate stepwise logistic regression to determine factors predicting outcome. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the independent (adjusted) effects of patients’ characteristics on the in-hospital mortality. Bivariate analysis of factors associated with post-discharge survival was performed by Cox regression, followed by multivariate Cox regression. The SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software (Version 21.0) was used for data processing and statistical analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 throughout.

Results

Table 1 provides the baseline patient characteristics and their influence on in-hospital mortality. The study group consisted of 554 patients who underwent mechanical ventilation for the first time during the 18 months of recruitment (from 1 March 2015 to 30 September 2016). The mean age was 79 years (65–100). Seventy-five percent of the patients were in their eighth and ninth decade of life, while 7% were above the age of 90. The vast majority (443; 80%) of patients lived at home prior to hospitalization, 225 (51%) lived with a spouse and 59 (13%) were cared for by a live-in foreign worker. Other sources of referral were assisted living facilities (14; 2.5%), nursing homes (71; 1.8%) and geriatric hospitals (17; 3.1%).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and bivariate analysis of factors associated with in-hospital mortality

| Characteristic | Patients groups | All patients | In-hospital mortality (Number and % of all patients) | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Number | % | P value | OR | Lower | Upper | ||

| Total | 554 | 355 | 64.1 | – | – | – | – | |

| Age groups (years) | 65–69 | 96 | 54 | 56.3 | 0.012 | 1.00 | ||

| 70–79 | 228 | 136 | 59.6 | 0.571 | 1.15 | 0.71 | 1.86 | |

| 80–89 | 189 | 133 | 70.4 | 0.018 | 1.85 | 1.11 | 3.08 | |

| 90 + | 41 | 32 | 78.0 | 0.018 | 2.77 | 1.19 | 6.42 | |

| Age groups (years) | < 85 | 424 | 259 | 61.1 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| ≥ 85 | 130 | 96 | 73.8 | 0.008 | 1.80 | 1.16 | 2.79 | |

| Gender | Female | 282 | 182 | 64.5 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Male | 272 | 173 | 63.6 | 0.818 | 0.96 | 0.68 | 1.36 | |

| Place of living | Home | 443 | 275 | 62.1 | 0.238 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Assisted living | 14 | 9 | 64.3 | 0.867 | 1.10 | 0.36 | 3.34 | |

| Nursing home | 71 | 53 | 74.6 | 0.043 | 1.80 | 1.02 | 3.18 | |

| Geriatric hospital | 17 | 13 | 76.5 | 0.237 | 1.99 | 0.64 | 6.19 | |

| Other | 9 | 5 | 55.6 | 0.691 | 0.76 | 0.20 | 2.88 | |

| First place of hospitalization | Internal medicine | 351 | 224 | 63.8 | 0.247 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Neurology | 30 | 14 | 46.7 | 0.067 | 0.50 | 0.23 | 1.05 | |

| ICU | 58 | 29 | 50.0 | 0.047 | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.99 | |

| ICCU | 41 | 25 | 61.0 | 0.721 | 0.89 | 0.46 | 1.72 | |

| Emergency room | 44 | 44 | 100.0 | 0.997 | – | 0.37 | 0.00 | |

| Other | 30 | 19 | 63.3 | 0.958 | 0.98 | 0.45 | 2.12 | |

| Performance (functional) status before admission | Independent | 240 | 132 | 55.0 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Frail* | 105 | 66 | 62.9 | 0.175 | 1.39 | 0.87 | 2.22 | |

| Nursing care** | 204 | 153 | 75.0 | < 0.001 | 2.46 | 1.64 | 3.69 | |

| Missing | 5 | 4 | 80.0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Mentally frail | No | 438 | 272 | 62.1 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 116 | 83 | 71.6 | 0.060 | 1.54 | 0.98 | 2.40 | |

| Oncologic disease | No | 442 | 282 | 63.8 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 112 | 73 | 65.2 | 0.786 | 1.06 | 0.69 | 1.64 | |

| Place of initiation of mechanical ventilation | Hospital physician | 391 | 260 | 66.5 | 0.014 | 1.64 | 1.10 | 2.44 |

| Out of hospital physician | 25 | 20 | 80.0 | 0.024 | 3.31 | 1.17 | 9.32 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Home/ambulance | 122 | 66 | 54.1 | 0.077 | 1.00 | – | – | |

| Nursing home/geriatric hospital | 3 | 2 | 66.7 | 0.669 | 1.70 | 0.15 | 19.21 | |

| Emergency room | 202 | 134 | 66.3 | 0.029 | 1.67 | 1.06 | 2.65 | |

| Hospital departments | 172 | 119 | 69.2 | 0.009 | 1.91 | 1.18 | 3.08 | |

| Other hospital | 26 | 19 | 73.1 | 0.081 | 2.30 | 0.90 | 5.88 | |

| Missing | 29 | 15 | 51.7 | – | – | – | – | |

| Tracheostomy during hospitalization | No | 415 | 285 | 68.7 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 138 | 70 | 50.7 | < 0.001 | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.70 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Weaning attempt from mechanical ventilation | No | 356 | 324 | 91.0 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 198 | 31 | 15.7 | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| Decision-making initiation mechanical ventilation | Team discussion | 175 | 123 | 70.3 | 0.097 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Single hospital physician | 356 | 216 | 60.7 | 0.031 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.96 | |

| Ambulance physician | 1 | 1 | 100.0 | 1.000 | – | 4.21 | 0.00 | |

| Missing | 22 | 15 | 68.2 | – | – | – | – | |

| Discussion with family before initiation of mechanical ventilation | No | 242 | 134 | 55.4 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 186 | 133 | 71.5 | 0.001 | 2.02 | 1.35 | 3.04 | |

| Family not present | 103 | 72 | 69.9 | 0.012 | 1.87 | 1.15 | 3.06 | |

| Missing | 23 | 16 | 69.6 | – | – | – | – | |

| Patient has advance directive | No | 275 | 178 | 64.7 | 0.876 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 11 | 7 | 63.6 | 0.941 | 0.95 | 0.27 | 3.34 | |

| Missing | 243 | 152 | 62.6 | 0.607 | 0.91 | 0.64 | 1.30 | |

| Asked about advance directive | No | 25 | 18 | 72.0 | – | – | – | – |

| Yes | 507 | 321 | 63.3 | – | 1.00 | – | – | |

| Missing | 23 | 17 | 73.9 | 0.305 | 1.64 | 0.64 | 4.24 | |

| Main ward/unit of hospitalization | ICU | 86 | 44 | 51.2 | 0.202 | 1.00 | – | – |

| ICCU | 50 | 29 | 58.0 | 0.441 | 1.32 | 0.65 | 2.66 | |

| Internal Medicine | 330 | 212 | 64.2 | 0.027 | 1.72 | 1.06 | 2.77 | |

| Recovery room | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 1.000 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Other | 34 | 18 | 52.9 | 0.861 | 1.07 | 0.49 | 2.38 | |

| Missing | 53 | 52 | 98.1 | – | – | – | – | |

| Timing (day from admission) of mechanical ventilation | Before admission to hospital | 15 | 8 | 53.3 | 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – |

| 0 + 1 | 123 | 62 | 50.4 | 0.831 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 2.60 | |

| 2 + | 415 | 285 | 68.7 | 0.218 | 1.92 | 0.68 | 5.40 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0.0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Application for admission to ICU | Approved by ICU | 3 | 1 | 33.3 | 0.592 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Rejected by ICU | 400 | 250 | 62.5 | 0.327 | 3.33 | 0.30 | 37.08 | |

| No application to ICU | 127 | 81 | 63.8 | 0.309 | 3.52 | 0.31 | 39.91 | |

| Missing | 24 | 23 | 95.8 | – | – | – | – | |

| First albumin (< = 4 days from admission) | 3.5 + | 29 | 13 | 44.8 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – |

| 3–3.4 | 89 | 45 | 50.6 | 0.592 | 1.26 | 0.54 | 2.92 | |

| 2.5–2.9 | 137 | 74 | 54.0 | 0.370 | 1.45 | 0.65 | 3.23 | |

| < 2.5 | 152 | 101 | 66.4 | 0.030 | 2.44 | 1.09 | 5.46 | |

| Missing | 147 | 122 | 83.0 | < 0.001 | 6.01 | 2.57 | 14.04 | |

| First blood urea nitrogen (< = 3 days from admission) | ≤ 30 | 271 | 148 | 54.6 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 30.01–40 | 78 | 49 | 62.8 | 0.199 | 1.40 | 0.84 | 2.36 | |

| 40.01–60 | 68 | 52 | 76.5 | < 0.001 | 2.70 | 1.47 | 4.97 | |

| > 60 | 74 | 59 | 79.7 | < 0.001 | 3.27 | 1.77 | 6.05 | |

| Missing | 63 | 47 | 74.6 | 0.004 | 2.44 | 1.32 | 4.52 | |

| Recurrent mechanical ventilation during hospitalization | No | 464 | 305 | 65.7 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Yes | 88 | 49 | 55.7 | 0.073 | 0.66 | 0.41 | 1.04 | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 50.0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Pneumonia | No | 482 | 310 | 64.3 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Pneumonia | 72 | 45 | 62.5 | 0.765 | 0.93 | 0.55 | 1.54 | |

| Myocardial infarction (MI) | No | 365 | 230 | 63.0 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| MI | 189 | 125 | 66.1 | 0.468 | 1.15 | 0.79 | 1.66 | |

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) | No | 404 | 268 | 66.3 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| CHF | 150 | 87 | 58.0 | 0.070 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 1.03 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) | NO | 518 | 329 | 63.5 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| PVD | 36 | 26 | 72.2 | 0.295 | 1.49 | 0.71 | 3.17 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | No | 385 | 243 | 63.1 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Cerebrovascular | 169 | 112 | 66.3 | 0.476 | 1.15 | 0.79 | 1.68 | |

| Dementia | No | 524 | 336 | 64.1 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Dementia | 30 | 19 | 63.3 | 0.930 | 0.97 | 0.45 | 2.07 | |

| Pulmonary disease | No | 381 | 257 | 67.5 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Pulmonary disease | 173 | 98 | 56.6 | 0.014 | 0.63 | 0.44 | 0.91 | |

| Connective tissue disease (CTD) | No | 546 | 349 | 63.9 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| CTD | 8 | 6 | 75.0 | 0.521 | 1.69 | 0.34 | 8.47 | |

| Ulcer | No | 544 | 351 | 64.5 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Ulcer | 10 | 4 | 40.0 | 0.124 | 0.37 | 0.10 | 1.32 | |

| Mild liver dysfunction | No | 534 | 342 | 64.0 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Mild liver dysfunction | 20 | 13 | 65.0 | 0.930 | 1.04 | 0.41 | 2.66 | |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | No | 408 | 256 | 62.7 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| DM | 146 | 99 | 67.8 | 0.274 | 1.25 | 0.84 | 1.87 | |

| Hemiplegia | No | 548 | 354 | 64.6 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Hemiplegia | 6 | 1 | 16.7 | 0.044 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.95 | |

| Moderate/severe renal failure | No | 300 | 170 | 56.7 | . | 1.00 | – | – |

| Moderate/severe renal failure | 254 | 185 | 72.8 | 0.000 | 2.05 | 1.43 | 2.94 | |

| DM with TOD (target organ disease) | No | 448 | 286 | 63.8 | . | 1.00 | – | – |

| DM with TOD | 106 | 69 | 65.1 | 0.809 | 1.06 | 0.68 | 1.65 | |

| Any tumor | No | 459 | 290 | 63.2 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Any tumor | 95 | 65 | 68.4 | 0.333 | 1.26 | 0.79 | 2.03 | |

| Moderate liver dysfunction | No | 551 | 354 | 64.2 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Moderate liver dysfunction | 3 | 1 | 33.3 | 0.298 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 3.09 | |

| Malignant solid tumor | No | 526 | 333 | 63.3 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Solid tumor | 28 | 22 | 78.6 | 0.108 | 2.13 | 0.85 | 5.33 | |

| Malignant lymphoma | No | 546 | 349 | 63.9 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Malignant lymphoma | 8 | 6 | 75.0 | 0.521 | 1.69 | 0.34 | 8.47 | |

| Leukemia | No | 547 | 349 | 63.8 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Leukemia | 7 | 6 | 85.7 | 0.258 | 3.40 | 0.41 | 28.48 | |

| Charlson index | 0–1 | 110 | 64 | 58.2 | 0.034 | 1.00 | – | – |

| 2–3 | 170 | 100 | 58.8 | 0.915 | 1.03 | 0.63 | 1.67 | |

| 4–5 | 119 | 72 | 60.5 | 0.721 | 1.10 | 0.65 | 1.87 | |

| 6 + | 135 | 99 | 73.3 | 0.013 | 1.98 | 1.16 | 3.38 | |

| Missing | 20 | 20 | 100.0 | – | – | – | – | |

| Performance (functional) status before admission | All other | 245 | 136 | 55.5 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Dependent | 309 | 219 | 70.9 | < 0.001 | 1.95 | 1.37 | 2.77 | |

| Gender and performance status | Female and independent | 245 | 136 | 55.5 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Other | 175 | 128 | 73.1 | < 0.001 | 2.18 | 1.44 | 3.32 | |

| Male and dependent | 134 | 91 | 67.9 | 0.019 | 1.70 | 1.09 | 2.64 | |

| Age and performance status | Age < 85y and independent | 212 | 115 | 54.2 | – | 1.00 | – | – |

| Age ≥ 85y or dependent | 342 | 240 | 70.2 | < 0.001 | 1.99 | 1.39 | 2.83 | |

| Age and performance status and comorbidity (at least one of the following: moderate/severe renal failure; cerebrovascular; malignant solid tumor; malignant lymphoma; leukemia) | Age < 85y and independent and w/o comorbidity | 72 | 27 | 37.5 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – |

| Age < 85y and independent and with comorbidity | 140 | 88 | 62.9 | < 0.001 | 2.82 | 1.57 | 5.08 | |

| Age ≥ 85y or dependent and w/o comorbidity | 119 | 74 | 62.2 | < 0.001 | 2.74 | 1.50 | 5.01 | |

| Age ≥ 85y or dependent and with comorbidity | 223 | 166 | 74.4 | < 0.001 | 4.85 | 2.76 | 8.53 | |

| Pneumonia | 71 | 45 | 63.4 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | – | – | |

| Infectious diseases (excluding pneumonia) | 58 | 43 | 74.1 | 0.194 | 1.66 | 0.77 | 3.54 | |

| Main diagnosis | Lung diseases (excluding pneumonia) | 121 | 59 | 48.8 | 0.051 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 1.00 |

| Cardiac diseases | 96 | 60 | 62.5 | 0.907 | 0.96 | 0.51 | 1.82 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 63 | 41 | 65.1 | 0.838 | 1.08 | 0.53 | 2.19 | |

| Coma and metabolic disease | 31 | 19 | 61.3 | 0.841 | 0.92 | 0.38 | 2.18 | |

| Other | 64 | 39 | 60.9 | 0.770 | 0.90 | 0.45 | 1.81 | |

| Missing | 50 | 49 | 98.0 | < 0.001 | 28.31 | 3.69 | 217 | |

OR odds ratio, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

*Frail refers to those who are mobile and require help in bathing and/or dressing and/or toileting

**Nursing care refers to those who are not mobile and require help in the majority of the basic activities of daily living

While 240 (43.7%) had been functionally independent prior to the initiation of mechanical ventilation, the majority of patients were functionally impaired prior to the event, with 105 (19.1%) classified as frail and 204 (37.2%) as requiring nursing care. As expected, comorbidities were common. The most frequent conditions were moderate or severe renal failure in 254 patients (46%), myocardial infarction in 189 (34%), chronic pulmonary disease (31%), cerebrovascular disease (30.5%), heart failure (27%), and diabetes mellitus (26%) (Table 1).

Ninety-eight percent of study patients were admitted to the emergency room urgently. Of the 544 subjects in the study cohort, 44 (7.9%) died in the emergency room following intubation and mechanical ventilation. A total of 351 (63%) were transferred directly to internal medicine wards, 58 (10.4%) were transferred to the medical ICU and 41 (7.4%) to the Coronary Care Unit. The remaining 30 (5.4%) patients were admitted to other in-patient wards.

Decision-making process: mechanical ventilation

The findings relating to the decision-making process regarding mechanical ventilation are presented in Table 1. Paramedics performed intubation and initiated mechanical ventilation in 137 (24.6%) patients prior to arrival at the hospital, with 25 (4.5%) patients being ventilated by physicians in referring hospitals. The decision to perform mechanical ventilation was made by a physician in the emergency room in 202 (36.5%) cases, and in one of the hospital wards in 172 (31%) instances. The decision to intubate and ventilate the patient was usually made urgently by a single physician (356; 91%) in the 391 in-hospital events. Family members of the patient were present in the vicinity in 428 (77.2%) of all cases (both prior to acute hospitalization and in the hospital), and in 186 (33.6%) cases the decision was shared with the family. In only 11 instances were advanced directives available at the time of the decision to commence mechanical ventilation.

General outcomes of treatment

The findings relating to the outcomes following mechanical ventilation are presented in Table 1 (in-hospital mortality) and Table 2 (post-discharge survival). Mortality was high and 355 (64.1%) ventilated patients died during hospitalization, with 172 (48.4%) of the deaths occurring during the first week of hospitalization. Of those patients who survived the hospitalization, 30 (14.1%) remained on chronic mechanical ventilation, and for those who were weaned from mechanical ventilation, 29 (13.6%) remained with tracheostomy. Seventy-eight (36.6%) patients were discharged to their homes, 49 (23%) to a rehabilitation framework, and 45 (21.1%) were transferred to nursing care institutions, including institutions for chronically ventilated patients. Overall survival at 6 months was 26% for the entire cohort. Most patients who died after the acute hospitalization did so in the first 6 months following hospital discharge. Overall survival for patients 85 years and older was 14% at 6 months and 11% at 2-years follow-up. It is interesting to note that for those discharged from hospital the survival rate did not change significantly over time (69% survived 6 months, 63% survived a year, and 57% survived 18 months). The best outcome of successful weaning from the ventilator during hospitalization, discharge home and survival at 6 months was found in 59 (10.6%) patients.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and bivariate analysis of factors associated with post-discharge

| Characteristic | Description | Number | Post-discharge survival | P value | HR | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months (%) | 1 year (%) | 1.5 years (%) | 2 years (%) | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Total | 199 | 69 | 63 | 57 | 51 | |||||

| Age groups (years) | 65–69 | 42 | 79 | 76 | 69 | 66 | 0.164 | 1.00 | ||

| 70–79 | 92 | 70 | 61 | 55 | 50 | 0.088 | 1.69 | 0.93 | 3.07 | |

| 80–89 | 56 | 64 | 55 | 52 | 42 | 0.024 | 2.06 | 1.10 | 3.87 | |

| 90 + | 9 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 0.362 | 1.68 | 0.55 | 5.10 | |

| Age groups (years) | < 85 | 165 | 73 | 66 | 60 | 54 | 1.00 | |||

| 85 + | 34 | 53 | 50 | 44 | 36 | 0.027 | 1.73 | |||

| Gender | Women | 100 | 77 | 68 | 67 | 59 | 1.00 | |||

| Men | 99 | 62 | 58 | 48 | 43 | 0.022 | 1.61 | 1.07 | 2.42 | |

| Place of living | Home | 168 | 74 | 67 | 63 | 56 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Assisted living | 5 | 60 | 0.889 | 1.11 | 0.27 | 4.51 | ||||

| Nursing home | 18 | 39 | 28 | 11 | 11 | < 0.001 | 3.34 | 1.93 | 5.78 | |

| Geriatric hospital | 4 | 0.472 | 1.67 | 0.41 | 6.83 | |||||

| Other | 4 | 25 | 0.185 | 2.19 | 0.69 | 6.95 | ||||

| Initial treatment unit | Internal medicine | 127 | 66 | 61 | 53 | 47 | 0.234 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Neurology | 16 | 69 | 56 | 56 | 56 | 0.548 | 0.79 | 0.36 | 1.72 | |

| Intensive care unit | 29 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 56 | 0.418 | 0.78 | 0.42 | 1.43 | |

| Coronary care unit | 16 | 88 | 88 | 88 | 79 | 0.029 | 0.28 | 0.09 | 0.87 | |

| Emergency room | 11 | 82 | 64 | 55 | 29 | 0.821 | 1.09 | 0.50 | 2.39 | |

| Performance (functional) status before admission | Independent | 108 | 80 | 74 | 71 | 62 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Frail* | 39 | 64 | 51 | 46 | 43 | 0.016 | 1.90 | 1.13 | 3.20 | |

| Nursing care** | 51 | 51 | 49 | 37 | 35 | < 0.001 | 2.47 | 1.55 | 3.92 | |

| Missing | 1 | |||||||||

| Mentally frail | No | 166 | 72 | 65 | 61 | 54 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 33 | 58 | 52 | 39 | 36 | 0.046 | 1.64 | 1.01 | 2.66 | |

| Oncological disease | No | 160 | 72 | 66 | 61 | 55 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 39 | 59 | 51 | 41 | 35 | 0.015 | 1.77 | 1.12 | 2.79 | |

| Decision-making about initiation of mechanical ventilation | Paramedic | 62 | 71 | 63 | 58 | 56 | 0.083 | 1.00 | ||

| Hospital physician | 131 | 71 | 65 | 59 | 50 | 0.684 | 1.10 | 0.70 | 1.71 | |

| Out of hospital physician | 5 | 20 | 0.027 | 3.28 | 1.15 | 9.41 | ||||

| Missing | 1 | |||||||||

| Tracheostomy status on discharge | No | 130 | 72 | 65 | 59 | 52 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 68 | 65 | 59 | 53 | 48 | 0.465 | 1.17 | 0.77 | 1.77 | |

| Missing | 1 | |||||||||

| Pneumonia | No | 172 | 68 | 62 | 57 | 50 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 27 | 78 | 67 | 59 | 54 | 0.715 | 0.89 | 0.49 | 1.64 | |

| Myocardial infarction (MI) | No | 135 | 68 | 63 | 56 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| MI | 64 | 72 | 63 | 61 | 52 | 0.795 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 1.45 | |

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) | No | 136 | 69 | 62 | 56 | 50 | 1.00 | |||

| CHF | 63 | 70 | 65 | 60 | 54 | 0.684 | 0.91 | 0.59 | 1.41 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) | NO | 189 | 69 | 63 | 57 | 52 | 1.00 | |||

| PVD | 10 | 60 | 50 | 50 | 33 | 0.535 | 1.30 | 0.57 | 2.97 | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | No | 142 | 71 | 66 | 61 | 54 | 1.00 | |||

| Cerebrovascular | 57 | 65 | 56 | 49 | 43 | 0.191 | 1.33 | 0.87 | 2.03 | |

| Dementia | No | 188 | 71 | 64 | 60 | 53 | 1.00 | |||

| Dementia | 11 | 46 | 36 | 18 | 18 | 0.006 | 2.62 | 1.32 | 5.22 | |

| Pulmonary disease | No | 124 | 66 | 60 | 56 | 50 | 1.00 | |||

| Pulmonary disease | 75 | 75 | 68 | 60 | 52 | 0.435 | 0.85 | 0.56 | 1.29 | |

| Connective tissue disease (CTD) | No | 197 | 70 | 63 | 57 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| CTD | 2 | 0.746 | 1.39 | 0.19 | 9.95 | |||||

| Ulcer | No | 193 | 69 | 63 | 58 | 52 | 1.00 | |||

| Ulcer | 6 | 33 | 33 | 0.232 | 1.85 | 0.68 | 5.03 | |||

| Mild liver dysfunction | No | 192 | 70 | 63 | 58 | 52 | 1.00 | |||

| Mild liver dysfunction | 7 | 29 | 29 | 0.162 | 1.90 | 0.77 | 4.69 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | No | 152 | 66 | 61 | 57 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| DM | 47 | 81 | 68 | 60 | 50 | 0.757 | 0.93 | 0.58 | 1.48 | |

| Hemiplegia | No | 194 | 70 | 63 | 58 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| Hemiplegia | 5 | 40 | 40 | 0.577 | 1.39 | 0.44 | 4.38 | |||

| Moderate/severe renal failure (RF) | No | 130 | 72 | 65 | 59 | 54 | 1.00 | |||

| RF | 69 | 65 | 58 | 54 | 44 | 0.189 | 1.32 | 0.87 | 1.99 | |

| DM with TOD (target organ disease) | No | 162 | 72 | 67 | 60 | 55 | 1.00 | |||

| DM with TOD | 37 | 60 | 46 | 43 | 33 | 0.028 | 1.68 | 1.06 | 2.67 | |

| Any tumor | No | 169 | 70 | 64 | 59 | 53 | 1.00 | |||

| Any tumor | 30 | 67 | 57 | 47 | 39 | 0.174 | 1.43 | 0.86 | 2.39 | |

| Moderate liver dysfunction | No | 197 | 70 | 63 | 57 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| Liver dysfunction (mod) | 2 | 0.116 | 3.09 | 0.76 | 12.55 | |||||

| Malignant solid tumor | No | 193 | 70 | 63 | 58 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| Solid tumor | 6 | 33 | 33 | 0.265 | 1.77 | 0.65 | 4.82 | |||

| Malignant lymphoma | No | 197 | 70 | 63 | 57 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| Malignant lymphoma | 2 | 0.602 | 1.69 | 0.24 | 12.14 | |||||

| Leukemia | No | 198 | 70 | 63 | 58 | 51 | 1.00 | |||

| Leukemia | 1 | 0.141 | 4.44 | 0.61 | 32.27 | |||||

| Charlson index | 0–1 | 46 | 78 | 74 | 67 | 65 | 0.036 | 1.00 | ||

| 2–3 | 70 | 73 | 69 | 61 | 57 | 0.377 | 1.31 | 0.72 | 2.40 | |

| 4–5 | 47 | 57 | 49 | 47 | 41 | 0.016 | 2.14 | 1.15 | 3.98 | |

| 6 + | 36 | 67 | 56 | 50 | 32 | 0.026 | 2.09 | 1.09 | 3.97 | |

| Age and performance status | Age < 85y and independent | 97 | 83 | 76 | 73 | 63 | 1.00 | |||

| Age ≥ 85 years or dependent | 102 | 57 | 50 | 42 | 40 | < 0.001 | 2.25 | 1.49 | 3.42 | |

| Age and performance status and comorbidity (DM with target organ failure/malignant solid tumor) | Age < 85 years and independent and w/o comorbidity | 45 | 82 | 80 | 75 | 68 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Age < 85 years and independent and with comorbidity | 52 | 83 | 73 | 71 | 59 | 0.638 | 1.17 | 0.60 | 2.29 | |

| Age ≥ 85 years or dependent and w/o comorbidity | 45 | 69 | 60 | 51 | 48 | 0.074 | 1.81 | 0.94 | 3.47 | |

| Age ≥ 85 years or dependent and with disease | 57 | 47 | 42 | 35 | 33 | < 0.001 | 3.16 | 1.73 | 5.76 | |

| Discharge to | Home | 78 | 80 | 74 | 68 | 63 | 0.004 | 1.00 | ||

| Rehabilitation | 49 | 69 | 61 | 59 | 51 | 0.207 | 1.42 | 0.82 | 2.46 | |

| Complex nursing care/chronic mechanical ventilation | 45 | 62 | 56 | 49 | 44 | 0.030 | 1.81 | 1.06 | 3.09 | |

| Other general hospital/other/missing | 27 | 52 | 44 | 37 | 28 | < 0.001 | 2.83 | 1.58 | 5.05 | |

| Ventilation status on discharge | Spontaneous breathing | 140 | 71 | 65 | 60 | 54 | 0.048 | 1.00 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation | 30 | 77 | 70 | 63 | 55 | 0.745 | 0.91 | 0.50 | 1.65 | |

| Spontaneous breathing and tracheostomy | 29 | 52 | 45 | 38 | 34 | 0.020 | 1.84 | 1.10 | 3.08 | |

| Outcome | Best: spontaneous breathing + discharge to home + survival > 6 m | 59 | 100 | 93 | 86 | 74 | < 0.001 | 1.00 | ||

| Spontaneous breathing + discharge to home + survival < 6 m | 15 | < 0.001 | 18.73 | 8.41 | 41.69 | |||||

| Spontaneous breathing + discharge other than home | 66 | 62 | 55 | 50 | 42 | < 0.001 | 4.09 | 2.13 | 7.85 | |

| Mechanical ventilation on discharge | 59 | 64 | 58 | 51 | 45 | < 0.001 | 3.84 | 1.98 | 7.46 | |

OR odds ratio, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval

*Frail refers to those who are mobile and require help in bathing and/or dressing and/or toileting

**Nursing care refers to those who are not mobile and require help in the majority of the basic activities of daily living

Factors affecting in-hospital mortality and post-discharge survival

We identified a number of predictors of in-hospital mortality. These included age, functional status, initiation of mechanical ventilation by a paramedic out of the hospital as compared to that performed by a physician in the hospital, performing ventilation in the emergency room rather than in an in-patient ward, laboratory results (a decreased albumin or hematocrit and an elevated blood urea nitrogen), lung disease, heart failure, renal failure, and a Charlson comorbidity index score above 6 (Table 1). We found the interaction of age, functional status, and concomitant morbidity to be a strong predictor of in-hospital mortality (Table 1).

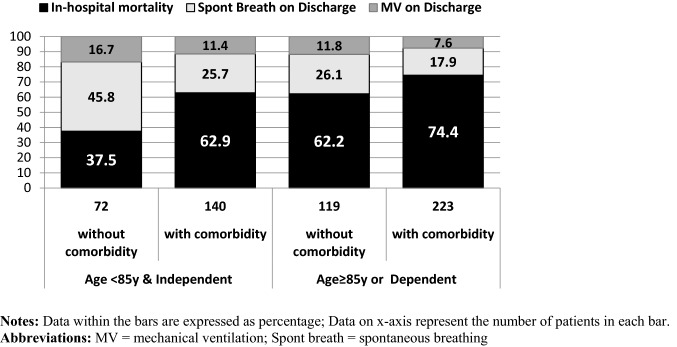

Table 3 presents the results of a model based on a multivariate logistic regression analysis of the factors predicting in-hospital mortality. Four independent variables were associated with the risk for in-hospital mortality, namely age over 85 years, poor functional status prior to hospitalization, comorbidities (moderate to severe renal insufficiency, cerebrovascular disease, solid tumors, lymphoma, leukemia) and elevated blood urea nitrogen. The in-hospital mortality and respiratory outcomes (breathing spontaneously or ongoing mechanical ventilation) at discharge according to the variables of this model are presented in Fig. 1. With regard to post-discharge mortality, a multivariate cox regression model found that age ≥ 85 years, gender and performance status, a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus with target organ involvement, as well as malignancy due to solid tumor, were significant predictors of poorer survival (Table 4).

Table 3.

Factors predicting in-hospital mortality: multivariate logistic regression model

| Patient groups | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age < 85 years and independent | Without comorbidity | 1 [Reference] |

| With comorbidity | 2.54 (1.40–4.61)* | |

| Age ≥ 85 years or dependent | Without comorbidity | 2.54 (1.38–4.67)* |

| With comorbidity | 3.84 (2.15–6.86)** | |

| BUN > 40 mg/dl | 2.13 (1.43–3.19)** | |

Comorbidity includes the following diseases: moderate to severe chronic renal failure, cerebrovascular disease, solid tumors, lymphoma, and leukemia

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, BUN blood urea nitrogen

AUCROC0.702 (95% CI 0.66–0.75); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001

Fig. 1.

In-hospital mortality and respiratory outcomes at discharge: illustration of multivariate logistic regression model (Table 3)

Table 4.

Factors predicting post-discharge mortality: multivariate Cox regression model†

| Patient groups | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Gender and functional status | |

| Female independent | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 1.02 (0.51–2.01) |

| Male dependent | 2.92 (1.78–4.80)** |

| Age ≥ 85 years | |

| No | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 1.92 (1.16–3.19)* |

| Diabetes mellitus with target organ involvement | |

| No | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2.05 (1.29–3.27)* |

| Malignant solid tumor | |

| No | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 2.88 (1.03–8.08)* |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

†For XBeta 0.72 (95% CI 0.65–0.79); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001

Discussion

We found that mechanical ventilation of older medical patients in the acute care setting has a poor outcome with high mortality. Our finding of 64.1% in-hospital mortality closely resembles that of 68.2% found in a previous study of similar design performed in a tertiary medical center in southern Israel [12, 18]. In most instances, the decision to initiate mechanical ventilation was made urgently by a single physician or paramedic.

It is of great importance for clinicians to have a better understanding of the factors influencing the survival of older people requiring mechanical ventilation, in order enable them to identify those with better prognosis according to the “choosing wisely” concept. We demonstrated a gradual increase of in-hospital mortality with advancing age (from “young old” to “oldest old”). Although advanced age is associated with increased mortality in intensive care unit patients, some studies have shown that older age of mechanically ventilated patients is not necessarily associated with mortality [19]. While these studies were conducted in the ICU, most of the patients in our study were treated in Internal Medicine wards, and the difference in our findings may be due to differences in patient selection. Due to the limited availability of ICU beds, patient selection to the ICU is much stricter and treatment outcomes are often better. Since only a small number of patients in our study were treated initially in the ICU, we could not demonstrate significant differences in outcomes between ICU and the high care units in Internal Medicine wards.

Clearly chronological age is no longer a barrier to intensive treatment and invasive interventions for stable older patients [20, 21]. Our finding that patients aged 85 years and older had a poorer prognosis for all measured outcomes, and this should be considered in the context of the acute and critical nature of their condition that resulted in intubation and mechanical ventilation. In our study, almost all patients were ventilated as an urgent procedure due to an acute respiratory failure, often with associated multi-organ failure. However, in all our models, advanced age remained an independent predictor of poorer survival, most probably related to the limited physiological reserves of people of this age group. Not surprisingly, poor functional status prior to hospitalization as well as a higher comorbidity burden, were also independent predictors for both in-hospital and post-discharge mortality.

Apart from the issue of survival, the quality of life of survivors is particularly relevant. Of those who survived the hospitalization, 30 (15.1%) patients required chronic mechanical ventilation. We did not identify previous studies relating to long-term mechanical ventilation following intubation for acute illness in older patients). This finding is of particular importance in the context of the Israeli health care system. As mentioned previously, religious, cultural and legal considerations in Israel have resulted in an increasing number of chronically ventilated patients in special units within long-term care institutions. To date there are 770 beds for chronically ventilated patients in Israel, and additional ventilated patients in acute care hospitals are “waiting” for transfer to these units.

Indeed, the “chronic critical illness” syndrome is present in up to 10% of those patients who survive a severe insult and require prolonged mechanical ventilation [22, 23]. These patients tend to suffer recurrent infections, organ dysfunction, profound weakness and delirium, and as many as half have died by 1 year. Among those who survive, readmission rates are high, most require long-term institutional care, and less than 12% are at home and functionally independent a year after their acute illness [18].

A limitation of our study is that although we had access to data regarding post-discharge mortality for up to 2 years, we do not have follow-up details regarding the post-discharge clinical and functional status of the patients. The number of patients discharged with permanent tracheostomy, as well as those needing institutional care, suggest a deterioration in quality of life for many of the patients [4, 24–27].

Endotracheal intubation may be delayed or traumatic in older patients and may thus be associated with poorer outcomes. We must emphasize that in our Center endotracheal intubation is usually performed by skilled and highly trained staff and is generally not delayed or traumatic. In addition, those who were intubated prior to arrival at hospital were intubated by experienced paramedics. All paramedics and physicians who were responsible for the initiation of mechanical ventilation were interviewed regarding the circumstances at the time of intubation and none reported events resulting in delayed or traumatic intubation. With respect to the decision regarding the initiation of mechanical ventilation, most of the decisions to ventilate were made by a single physician urgently in the hospital. Although families were present in the vicinity in many instances, they were seldom asked regarding the existence of advanced directives. In fact, in very few instances had patients prepared their preferences as advanced directives. The importance of autonomy and respecting the wishes of patients at the time of critical medical decision-making should encourage a much wider use of advanced directives for the older population.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that mechanical ventilation has limited value when used for very old, frail and chronically ill patients with acute medical conditions. This study is published in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, where ICU resources are stretched to their limits. In normal circumstances, Israel is unique in the developed world in that most ventilated patients are not admitted to the intensive care unit but rather to dedicated high care units in medical wards. As such, the care of older ventilated patients in medical wards may present a reasonable alternative. In addition, the question regarding the initiation of mechanical ventilation for older frail patients is raising difficult, painful questions for the providers of health care at a time of crisis. Although this study does not relate specifically to the severe respiratory complications of Covid-19 infections, the findings of this study make an important contribution to the decision-making process regarding mechanical ventilation for older people.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Lea Vugman for collecting the data and interviewing the physicians and paramedics who initiated mechanical ventilation for the study patients. We also thank Mr Elad Rubin for collating and organizing the data for analysis.

Author contributions

BS, AR-P and TD designed the study and submitted for ethics committee approval and funding. All the authors were involved in conducting the study and writing the manuscript. TM performed the statistical analysis. All the authors approved the submitted manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant provided by the Israel National Institute for Health Policy Research (Grant Number 2014/85).

Availability of data and material

Data and study materials are available from the authors on request.

Code availability

Not relevant.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Committee for Research in Human Subjects (the Helsinki Committee) of the Rambam Health Care Campus, and the need for informed patient consent was waived for this study.

Consent to participate

Waived in accordance with Ethics Committee decision.

Consent for publication

Waived in accordance with Ethics Committee decision.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bella Smolin and Ayelet Raz-Pasteur contributed equally as first authors.

References

- 1.Dwolatzky T, Brodsky J, Azaiza F, et al. Coming of age: health-care challenges of an ageing population in Israel. Lancet. 2017;389:2542–2550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Den Noortgate N, Vogelaers D, Afschrift M, Colardyn F. Intensive care for very elderly patients: outcome and risk factors for in-hospital mortality. Age Ageing. 1999;28:253–256. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ely EW, Evans GW, Haponik EF. Mechanical ventilation in a cohort of elderly patients admitted to an intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:96–104. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-2-199907200-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montuclard L, Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, et al. Outcome, functional autonomy, and quality of life of elderly patients with a long-term intensive care unit stay. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3389–3395. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chelluri L, Im KA, Belle SH, et al. Long-term mortality and quality of life after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:61–69. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098029.65347.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simchen E, Sprung CL, Galai N, et al. Survival of critically ill patients hospitalized in and out of intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:449–457. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253407.89594.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boumendil A, Aegerter P, Guidet B. Treatment intensity and outcome of patients aged 80 and older in intensive care units: a multicenter matched-cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:88–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Rooij SE, Abu-Hanna A, Levi M, de Jonge E. Factors that predict outcome of intensive care treatment in very elderly patients: a review. Crit Care. 2005;9:307–314. doi: 10.1186/cc3536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bo M, Massaia M, Raspo S, et al. Predictive factors of in-hospital mortality in older patients admitted to a medical intensive care unit. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:529–533. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagon JY. Acute respiratory failure in the elderly. Crit Care. 2006;10:3–5. doi: 10.1186/cc4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demoule A, Cracco C, Lefort Y, et al. Patients aged 90 years or older in the intensive care unit. J Gerontol. 2005;60:129–132. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieberman D, Nachshon L, Miloslavsky O, et al. Elderly patients undergoing mechanical ventilation in and out of intensive care units: a comparative, prospective study of 579 ventilations. Crit Care. 2010 doi: 10.1186/cc8935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hersch M, Sonnenblick M, Karlic A, et al. Mechanical ventilation of patients hospitalized in medical wards vs the intensive care unit-an observational, comparative study. J Crit Care. 2007;22:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen IL, Lambrinos J. Investigating the impact of age on outcome of mechanical ventilation using a population of 41,848 patients from a statewide database. Chest. 1995;107:1673–1680. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.6.1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolin B, Levy Y, Sabbach-Cohen E, et al. Predicting mortality of elderly patients acutely admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine. Int J Clin Pract. 2015 doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Carlet J. Predicting whether the ICU can help older patients: score needed. Crit Care. 2005;9:331–332. doi: 10.1186/cc3750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perneger TV, Gaspoz JM, Raë AC, et al. Contribution of individual items to the performance of the Norton pressure ulcer prediction scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:1282–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieberman D, Nachshon L, Miloslavsky O, et al. How do older ventilated patients fare? A survival/functional analysis of 641 ventilations. J Crit Care. 2009;24:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zingone B, Gatti G, Rauber E, et al. Early and late outcomes of cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engoren M, Arslanian-Engoren C, Steckel D, et al. Cost, outcome, and functional status in octogenarians and septuagenarians after cardiac surgery. Chest. 2002;122:1309–1315. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cox CE, Carson SS, Holmes GM, et al. Increase in tracheostomy for prolonged mechanical ventilation in North Carolina, 1993–2002. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2219–2226. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000145232.46143.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheinhorn DJ, Hassenpflug MS, Votto JJ, et al. Ventilator-dependent survivors of catastrophic illness transferred to 23 long-term care hospitals for weaning from prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2007;131:76–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson JE, Cox CE, Hope AA, Carson SS. Chronic critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:446–454. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0210CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Endeman H, Heeffer L, Holleman F, et al. Influence of old age on survival after prolonged mechanical ventilation. Eur J Intern Med. 2005;16:116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garland A, Dawson NV, Altmann I, et al. Outcomes up to 5 years after severe, acute respiratory failure. Chest. 2004;126:1897–1904. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnato AE, Albert SM, Angus DC, et al. Disability among elderly survivors of mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1037–1042. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0301OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD. The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020;323(18):1771–1772. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and study materials are available from the authors on request.

Not relevant.