Abstract

Background

Patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma have poor overall survival after platinum-containing chemotherapy and programmed cell death protein-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/L1) inhibitor treatment.

Methods

EV-301 is a global, open-label, phase 3 trial of enfortumab vedotin in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who had previously received a platinum-containing chemotherapy and experienced disease progression during or following treatment with a PD-1/L1 inhibitor. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive enfortumab vedotin 1.25 mg/kg on Days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle, or investigator-chosen standard docetaxel, paclitaxel, or vinflunine. The primary endpoint was overall survival.

Results

Overall, 608 patients were randomized to enfortumab vedotin (n=301) or chemotherapy (n=307). As of July 15, 2020, a total of 301 deaths (enfortumab vedotin, n=134; chemotherapy, n=167) had occurred. At the prespecified interim analysis, the median follow-up was 11.1 months. Overall survival was prolonged with enfortumab vedotin compared with chemotherapy (HR=0.70 [95% CI: 0.56–0.89]; P=0.00142; median overall survival: 12.88 vs 8.97 months, respectively). Progression-free survival was also longer in the enfortumab vedotin group compared with the chemotherapy group (HR=0.62 [95% CI: 0.51–0.75]; P<0.00001; median progression-free survival: 5.55 vs 3.71 months, respectively). Rates of treatment-related adverse events were comparable between enfortumab vedotin (93.9%) and chemotherapy (91.8%) groups; events of grade ≥3 severity were also comparable (51.4% and 49.8%, respectively).

Conclusions

Enfortumab vedotin significantly prolonged survival over standard chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma who previously received platinum-based treatment and a PD-1/L1 inhibitor.

(ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03474107)

INTRODUCTION

Platinum-based chemotherapy sequenced with programmed cell death protein-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/L1) inhibitors is the standard of care for patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma.1–4 Despite treatment advances, this disease remains aggressive and generally incurable.5–7 Unfortunately, urothelial cancers are associated with intrinsic and acquired resistance to chemotherapy.8,9 While immunotherapy is better tolerated and associated with an improved duration of response versus chemotherapy, a minority of patients attain a durable response.5,6,8,10–12 Median overall survival with these therapies is only 10–14 months.5,6,13,14

Nectin-4 is a cell adhesion molecule highly expressed in urothelial carcinoma that may contribute to tumor cell growth and proliferation.15–19 Enfortumab vedotin, an antibody-drug conjugate directed against Nectin-4, is comprised of a fully human monoclonal antibody specific for Nectin-4 and monomethyl auristatin E, a microtubule-disrupting agent.16 Targeted delivery of this agent results in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.16,17

EV-301 (NCT03474107) is a global, open-label, phase 3 trial evaluating enfortumab vedotin versus chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma previously treated with a platinum agent and PD-1/L1 inhibitor. In prior single-arm clinical studies, enfortumab vedotin demonstrated objective response rates >40% in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma who had progressed after previous treatment.16,17 This trial was designed to confirm the clinical benefit of enfortumab vedotin over standard chemotherapy by comparing the overall survival in patients with previously treated advanced urothelial carcinoma.

METHODS

Trial Participants

Patients aged ≥18 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed urothelial carcinoma, including those with squamous cell differentiation or mixed cell types, and radiologically documented metastatic or unresectable locally advanced disease at baseline and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0 or 1 (graded 0–4 where higher numbers reflect greater disability), were eligible. Patients must have experienced radiographic progression or relapse during or after PD-1/L1 inhibitor treatment. Additionally, patients must have received a platinum-containing regimen. For patients treated with platinum chemotherapy in the neoadjuvant or adjuvant setting, progression must have occurred within 12 months of completion.

Patients were excluded from the trial if they had a preexisting grade ≥2 sensory or motor neuropathy or ongoing clinically significant toxicity associated with prior treatment; active central nervous system metastases; uncontrolled diabetes; active keratitis or corneal ulcerations; or if they had received >1 prior chemotherapy regimen for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma, including for adjuvant or neoadjuvant disease. Full eligibility criteria are available in the trial protocol available at NEJM.org.

Randomization and Treatments

Enrolled patients were randomized 1:1 to receive enfortumab vedotin or chemotherapy. Randomization was stratified based on ECOG performance-status score, geographic region, and liver metastasis at baseline. Enfortumab vedotin 1.25 mg/kg was given via intravenous (IV) infusion over 30 minutes on Days 1, 8, and 15 of each 28-day cycle. Chemotherapy was investigator-preselected before randomization from docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV over 60 minutes, paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 IV over 3 hours, or vinflunine 320 mg/m2 IV over 20 minutes (in regions where it is approved for urothelial carcinoma; capped at 35% of patients) on Day 1 of each 21-day cycle. Patients receiving enfortumab vedotin or vinflunine required no premedication, whereas all patients receiving paclitaxel or docetaxel were premedicated to prevent hypersensitivity reactions and/or fluid retention. Dose modifications and interruptions were permitted to manage adverse events based on prespecified criteria (Table S1).

Trial Oversight

This trial was designed by the sponsors (Astellas Pharma US, Inc. and Seagen Inc.) in collaboration with an advisory committee. Data were collected by investigators, analyzed by statisticians employed by Astellas Pharma US, Inc., and interpreted by all authors. This trial received Institutional Review Board/Independent Ethics Committee approval and was conducted in accordance with the trial protocol, International Council for Harmonisation guidelines, and applicable regulations and guidelines per the Declaration of Helsinki. Written and signed informed consent was obtained from each patient before trial entry.

All authors attest that the trial was conducted in accordance with the protocol and the standards of Good Clinical Practice. All authors had access to data used for manuscript preparation. The authors, with writing and editorial support funded by the study sponsors, developed and approved the manuscript.

Endpoints and Assessments

The primary endpoint was overall survival. Key secondary efficacy endpoints, based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1, included investigator-assessed progression-free survival and clinical response. Safety/tolerability was also a secondary endpoint; investigator-assessed adverse events were graded per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03.

Radiographic imaging was performed at baseline and every 8 weeks. All patients had bone scintigraphy performed at screening/baseline and those with a positive scan received repeated scans at least every 8 weeks. Brain scans were performed, if clinically indicated, at baseline and throughout the trial. Patients were followed until radiographic disease progression, discontinuation criteria were met (available in the protocol), or trial completion. Patients discontinuing treatment before disease progression continued with imaging assessments every 8 weeks until documented disease progression or initiation of another anticancer treatment, whichever occurred earlier. Following radiographic disease progression, patients entered the long-term follow-up phase and were followed no less than every 3 months from the date of the follow-up visit for survival status until death, loss to follow-up, withdrawal of trial consent, or trial termination. Quality of life, patient-reported outcomes, and additional exploratory efficacy endpoints were assessed, but are not reported here.

Statistical Analyses

Overall and progression-free survival were estimated for each treatment group using Kaplan-Meier methodology and comparisons between arms were conducted using the stratified log-rank test. Sensitivity analyses were also planned. Stratified Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Overall and progression-free survival analyses were evaluated in all randomized patients. Response rates and disease control rate (defined as the proportion of patients who achieved a best overall response of complete response, partial response, or stable disease per RECIST v1.1) were compared using a stratified Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test to estimate differences between groups. Duration of response was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Overall response and disease control rates were assessed in all randomized patients with measurable disease at baseline. The randomization stratification factors were applied to all stratified efficacy analyses.

Safety analyses were performed for patients receiving any amount of study drug and evaluated using descriptive statistics. Prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted using demographic and baseline disease characteristics. All analyses were performed using SAS® Version 9.2 or higher.

EV-301 was a group-sequential design with two planned analyses (interim and final). The primary endpoint and selected key secondary endpoints (progression-free survival, overall response rate, and disease control rate) were tested following the hierarchical gatekeeping procedure (Supplement). Prespecified multiplicity adjustment methods were used to control the overall type I error rate at 0.025. Efficacy boundaries were calculated based on the information fraction at the time of analysis. The 95% CIs presented herein describe the precision of the point estimates and may not correspond to the significance of the test. Assuming an HR of 0.75 with median overall survival of 8 months for chemotherapy, 10% dropout rate, final analysis to be conducted at 439 death events, and one interim analysis conducted at 65% of death events, a sample size of ~600 patients would provide 85% power to detect a statistically significant difference at an overall one-sided 0.025 type I error rate. The interim analysis was conducted by the Independent Data Analysis Center and reviewed by an Independent Data Monitoring Committee also chartered to oversee safety. If the interim analysis demonstrated statistically significant improvement in efficacy with enfortumab vedotin, the study would be stopped and concluded.

At the interim analysis, overall survival was tested at a one-sided significance level of 0.00541 (adjusted to 0.00679 based on 301 observed deaths) for efficacy according to the O’Brien-Fleming stopping boundary, as implemented by Lan-DeMets alpha spending function. Based on the interim outcomes, our study met the superiority threshold and these results are reported here. As outcomes were determined from tests associated with stopping rules, data are presented with one-sided P-values. Full statistical methodology is available in the statistical analysis plan.

RESULTS

Disposition, Demographics, and Baseline Disease Characteristics

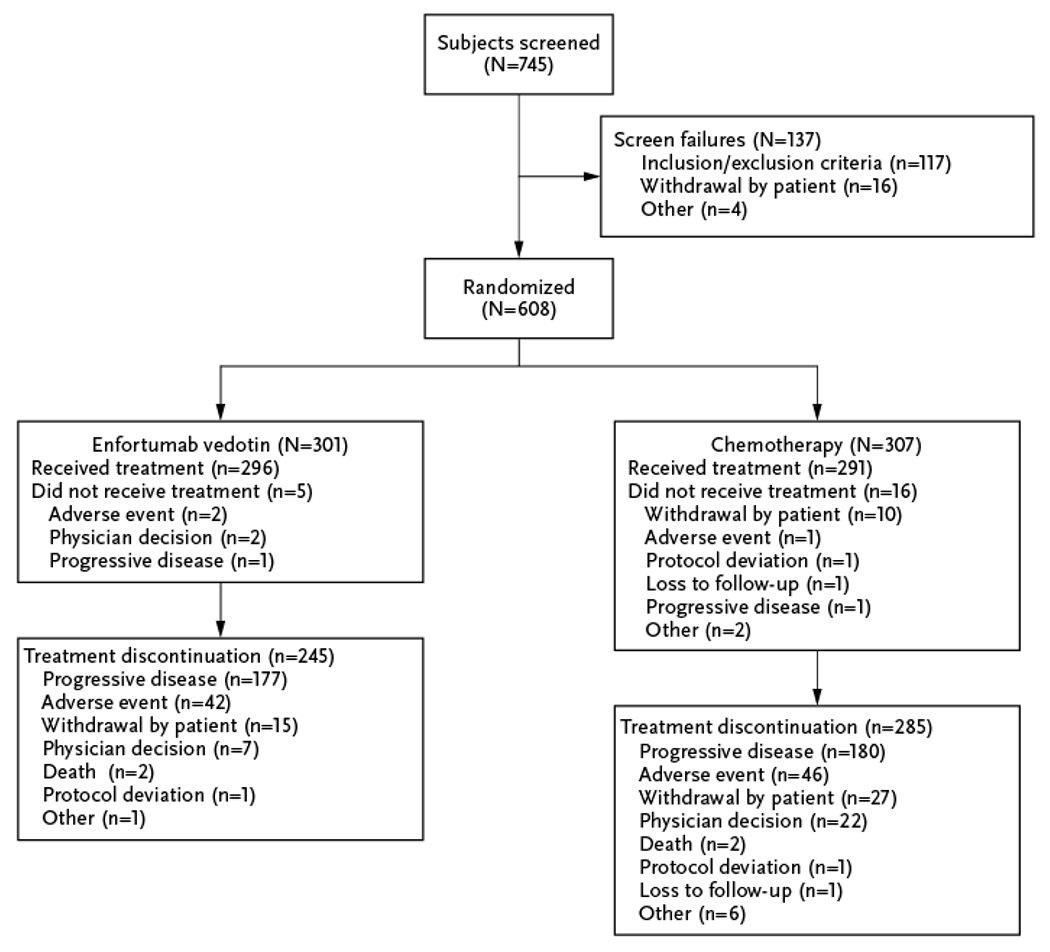

A total of 608 patients from 191 centers in 19 countries were randomized to receive enfortumab vedotin (n=301) or investigator-preselected chemotherapy (n=307) (Fig. 1). In those randomized to chemotherapy, 117, 112, and 78 patients were to receive docetaxel, paclitaxel, and vinflunine, respectively. A total of 296 patients in the enfortumab vedotin group and 291 patients in the chemotherapy group received treatment.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram.

Baseline characteristics were generally balanced between arms (Table 1). The median age was 68 years (range: 30–88) and most patients (77.3%) were male. Visceral disease was present in 77.7% and 81.7% of patients in the enfortumab vedotin and chemotherapy groups, respectively; the proportion of patients with liver metastasis was the same in both groups. At the July 15, 2020 data cutoff, median duration of treatment was 5.0 months (range: 0.5–19.4) for enfortumab vedotin and 3.5 months (range: 0.2–15.0) for chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients at Baseline (Intention-to-Treat Population).

| Parameter, n (%)* | Enfortumab Vedotin (N=301) | Chemotherapy (N=307) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (range) | 68.0 (34.0–85.0) | 68.0 (30.0–88.0) |

| ≥75 years | 52 (17.3) | 68 (22.1) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 238 (79.1) | 232 (75.6) |

| Female | 63 (20.9) | 75 (24.4) |

| Geographic region | ||

| Western Europe | 126 (41.9) | 129 (42.0) |

| United States | 43 (14.3) | 44 (14.3) |

| Rest of the world | 132 (43.9) | 134 (43.6) |

| Tobacco history | ||

| Former user | 167 (55.5) | 164 (53.4) |

| Current user | 29 (9.6) | 31 (10.1) |

| Never used | 91 (30.2) | 102 (33.2) |

| Not reported/unknown | 14 (4.7) | 10 (3.3) |

| History of diabetes or hyperglycemia | 56 (18.6) | 58 (18.9) |

| ECOG performance-status score | ||

| 0 | 120 (39.9) | 124 (40.4) |

| 1 | 181 (60.1) | 183 (59.6) |

| Bellmunt risk score | ||

| 0-1 | 201 (66.8) | 208 (67.8) |

| ≥2 | 90 (29.9) | 96 (31.3) |

| Not reported | 10 (3.3) | 3 (1.0) |

| Primary disease site of origin | ||

| Upper tract | 98 (32.6) | 107 (34.9) |

| Bladder or other | 203 (67.4) | 200 (65.1) |

| Histology type at initial diagnosis | ||

| Urothelial carcinoma/transitional cell | 229 (76.1) | 230 (75.4) |

| Urothelial carcinoma mixed | 45 (15.0) | 42 (13.8) |

| Otherꝉ | 27 (9.0) | 33 (10.8) |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 (0.7) |

| Metastatic sites | ||

| Lymph node only | 34 (11.3) | 28 (9.2) |

| Visceral disease | 234 (77.7) | 250 (81.7) |

| Liver metastasis | 93 (30.9) | 95 (30.9) |

| Prior lines of systemic therapy | ||

| 1-2 | 262 (87.0) | 270 (87.9) |

| ≥3 | 39 (13.0) | 37 (12.1) |

| Best response to prior CPI | ||

| Responder | 61 (20.3) | 50 (16.3) |

| Non-responder | 207 (68.8) | 215 (70.0) |

| Time since metastatic or locally advanced disease diagnosis (months), median (range) | 14.8 (0.2–114.1) | 13.2 (0.3–118.4) |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise noted.

Other histologies include adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and pseudosarcomatic differentiation.

CPI denotes checkpoint inhibitor, and ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Overall Survival

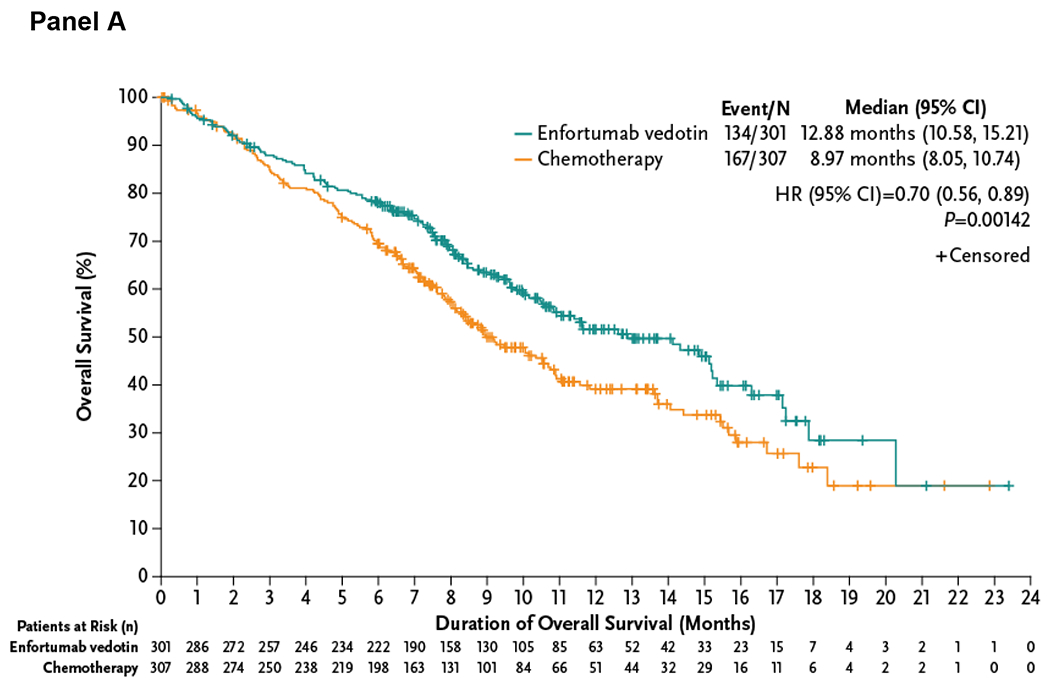

At the data cutoff, a total of 301 deaths (enfortumab vedotin, n=134; chemotherapy, n=167) were reported. Compared with chemotherapy, enfortumab vedotin reduced the risk of death by 30% (HR=0.70 [95% CI: 0.56–0.89]; P=0.00142), resulting in a statistically significant improvement in overall survival. Results of sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analysis (Table S2). The median overall survival was 12.88 months (95% CI: 10.58–15.21 months) with enfortumab vedotin and 8.97 months (95% CI: 8.05–10.74 months) with chemotherapy (Fig. 2A). Estimated 12-month survival rates (95% CI) were 51.5% (44.6–58.0) and 39.2% (32.6–45.6) with enfortumab vedotin and chemotherapy, respectively. The overall survival benefit of enfortumab vedotin was retained in most subgroups (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Overall Survival in the Intention-to-Treat Population and Analysis in Key Subgroups.

The primary endpoint of overall survival was defined as the time from randomization to the date of death, analyzed in the intention-to-treat population that included all patients randomized to treatment. The Kaplan-Meier estimate of overall survival according to treatment group is shown in Panel A. A forest plot displays the subgroup analyses, shown in Panel B, of prespecified key subgroups also examined in the intention-to-treat population. In all subjects, the hazard ratio is reported for all patients based on stratified analysis with the following factors: ECOG performance-status score, geographic region, and presence of liver metastasis recorded at randomization. In each subgroup, the hazard ratio was estimated using unstratified Cox proportional hazards model with treatment. Assuming proportional hazards, a hazard ratio of <1 indicates reduction in the hazard ratio favoring enfortumab vedotin treatment.

CI denotes confidence interval, and HR hazard ratio.

CI denotes confidence interval, CPI checkpoint inhibitor, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance-Status Score, HR hazard ratio, US United States, and W western.

Progression-Free Survival

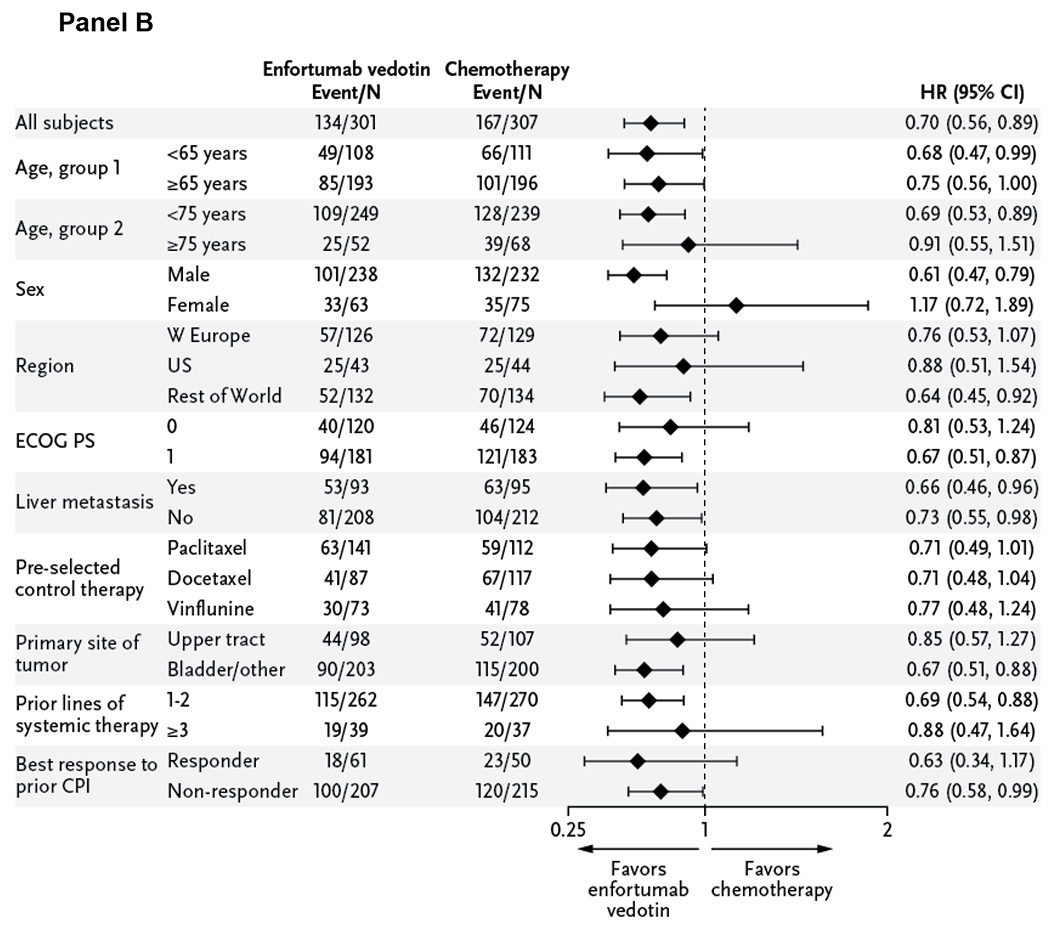

Enfortumab vedotin significantly improved progression-free survival, with a 38% reduction in the risk of progression or death (HR=0.62 [95% CI: 0.51–0.75]; P<0.00001). Median progression-free survival with enfortumab vedotin was 5.55 months (95% CI: 5.32–5.82) and 3.71 months (95% CI: 3.52–3.94) with chemotherapy (Fig. 3). Subgroup analyses (Fig. S1) show a progression-free survival benefit from enfortumab vedotin was present across multiple subgroups.

Figure 3. Progression-Free Survival in the Intention-to-Treat Population.

The Kaplan-Meier estimate of progression-free survival according to treatment group is shown. The secondary endpoint of investigator-assessed progression-free survival was defined as the time from randomization until the date of radiological disease progression (per RECIST v1.1) or until death due to any cause, analyzed in the intention-to-treat population that included all patients randomized to treatment. If the patient neither progressed nor died, the patient was censored at the date of last radiological assessment. Patients who received any further anticancer therapy for urothelial carcinoma before radiological progression were censored at the date of the last radiological assessment before the anticancer therapy started.

CI denotes confidence interval, and HR hazard ratio.

Clinical Response

The confirmed overall response rate was higher for patients treated with enfortumab vedotin (40.6% [95% CI: 34.9–46.5]) than for those treated with chemotherapy (17.9% [95% CI: 13.7–22.8]; P<0.001) (Table S3). Results were consistent among subgroups (Fig. S2). Complete response was achieved in 4.9% (n=14/288) and 2.7% (n=8/296) of the enfortumab vedotin and chemotherapy groups, respectively; disease control rate was 71.9% (95% CI: 66.3–77.0) and 53.4% (95% CI: 47.5–59.2; P<0.001), respectively. In patients with overall response, the duration of response was 7.39 and 8.11 months, respectively (Fig. S3).

Safety and Tolerability

Overall, the frequency of treatment-related adverse events was high, but rates were similar between patients receiving enfortumab vedotin (93.9%) and chemotherapy (91.8%) (Table 2). Treatment-related adverse events of grade ≥3 severity occurred in ~50% of patients in both groups and when adjusted for treatment exposure, were 2.4 and 4.3 events per patient-year for enfortumab vedotin and chemotherapy, respectively (Table S4). Grade ≥3 severity treatment-related adverse events occurring in ≥5% of patients treated with enfortumab vedotin included maculopapular rash (7.4%), fatigue (6.4%), and decreased neutrophil count (6.1%) versus decreased neutrophil count (13.4%), anemia (7.6%), decreased white blood cell count (6.9%), neutropenia (6.2%), and febrile neutropenia (5.5%) for patients treated with chemotherapy. Treatment-related adverse events leading to dose reduction, interruption, or withdrawal for enfortumab vedotin versus chemotherapy occurred in 32.4% versus 27.5%, 51.0% versus 18.9%, and 13.5% versus 11.3%, respectively (Table S5); exposure-adjusted rates are also reported (Table S4). Treatment-emergent adverse event rates are reported in Table S6.

Table 2.

Treatment-Related Adverse Events* (Safety Analysis Population).

| Enfortumab Vedotin Group (N=296) | Chemotherapy Group (N=291) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse event, n (%) | All Grade | Grade ≥3 | All Grade | Grade ≥3 |

| Any adverse event | 278 (93.9) | 152 (51.4) | 267 (91.8) | 145 (49.8) |

|

| ||||

| Alopecia | 134 (45.3) | 0 | 106 (36.4) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Peripheral sensory neuropathyꝉ | 100 (33.8) | 9 (3.0) | 62 (21.3) | 6 (2.1) |

|

| ||||

| Pruritus | 95 (32.1) | 4 (1.4) | 13 (4.5) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Fatigue | 92 (31.1) | 19 (6.4) | 66 (22.7) | 13 (4.5) |

|

| ||||

| Decreased appetite | 91 (30.7) | 9 (3.0) | 68 (23.4) | 5 (1.7) |

|

| ||||

| Diarrhea | 72 (24.3) | 10 (3.4) | 48 (16.5) | 5 (1.7) |

|

| ||||

| Dysgeusia | 72 (24.3) | 0 | 21 (7.2) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Nausea | 67 (22.6) | 3 (1.0) | 63 (21.6) | 4 (1.4) |

|

| ||||

| Rash maculopapular | 48 (16.2) | 22 (7.4) | 5 (1.7) | 0 |

|

| ||||

| Anemia | 34 (11.5) | 8 (2.7) | 59 (20.3) | 22 (7.6) |

|

| ||||

| Neutrophil count decreased | 30 (10.1) | 18 (6.1) | 49 (16.8) | 39 (13.4) |

|

| ||||

| Neutropenia | 20 (6.8) | 14 (4.7) | 24 (8.2) | 18 (6.2) |

|

| ||||

| WBC decreased | 16 (5.4) | 4 (1.4) | 31 (10.7) | 20 (6.9) |

|

| ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) | 16 (5.5) | 16 (5.5) |

Treatment-related adverse events occurring in ≥20% of patients in either treatment group or grade ≥3 treatment-related adverse events occurring in ≥5% of patients in either treatment group. “Treatment-related adverse event” indicates reasonable possibility that the event may have been caused by the study treatment as assessed by the investigator. If the relationship is missing, then the adverse event is considered to be treatment-related.

A total of 113 patients (enfortumab vedotin, n=55; chemotherapy, n=58) had pre-existing peripheral neuropathy.

WBC denotes white blood cell.

Skin reactions and peripheral neuropathy were the most frequent treatment-related adverse events of special interest for enfortumab vedotin (Table S7). Treatment-related rash occurred in 43.9% of enfortumab vedotin–treated patients (grade [G]1: 13.9%; G2: 15.5%; G3: 14.2%; G4: 0.3%) and 9.6% of chemotherapy-treated patients (G1: 7.2%; G2: 2.1%; G3: 0.3%). Treatment-related peripheral neuropathy, presenting predominantly as sensory events, occurred in 46.3% and 30.6% of patients in enfortumab vedotin and chemotherapy groups, respectively; grade 1, 2, and 3 peripheral sensory neuropathy occurred in 14.5%, 25.7.1%, and 3.7% of patients treated with enfortumab vedotin and 15.1%, 12.0%, and 2.4% of patients treated with chemotherapy. Peripheral sensory neuropathy was the most common treatment-related adverse event leading to dose reduction (7.1%), interruption (15.5%), and withdrawal (2.4%) in the enfortumab vedotin group (Table S5).

Treatment-related hyperglycemia occurred in 6.4% (n=19) of the enfortumab vedotin and 0.3% (n=1) of the chemotherapy groups. In the enfortumab vedotin group, seven patients had grade 1 or 2 hyperglycemia, 11 patients had grade 3 hyperglycemia, and one fatal event occurred. Hyperglycemia occurred more frequently in patients with baseline hyperglycemia or BMI ≥30 kg/m2. Time to adverse event onset, incidence of peripheral neuropathy and hyperglycemia by baseline status, and management of selected adverse events are reported in Tables S7–9.

Overall, treatment-emergent adverse events leading to death, excluding disease progression, occurred in 11 patients in each group (Table S6); the incidence remained the same after adjusting for treatment exposure (Table S4). Investigator-assessed treatment-related adverse events leading to death occurred in seven (2.4%) patients treated with enfortumab vedotin (multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, n=2; abnormal hepatic function, hyperglycemia, pelvic abscess, pneumonia, septic shock, n=1 each) and three (1.0%) patients treated with chemotherapy (neutropenic sepsis, sepsis, and pancytopenia, n=1 each). Patient demographics for deaths in the enfortumab vedotin group are described in Table S10.

DISCUSSION

Enfortumab vedotin demonstrated superior efficacy over chemotherapy in patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and PD-1/L1 inhibitors. After disease progression with platinum chemotherapy and PD-1/L1 inhibitors, patients have limited and largely ineffective treatment options. Single-agent chemotherapy has been the de facto standard of care despite limited prospective data and modest outcomes.7,20–24

Enfortumab vedotin reduced the risk of death by 30% compared with chemotherapy, resulting in a statistically significant improvement in overall survival. The benefit of enfortumab vedotin was observed across most subgroups, including patients with liver metastasis. While female patients did not show an advantage in subgroup analyses, women represented only 22.7% of patients in the trial, which itself is a function of the demographics of this disease. Future work would be needed to explore this further.

Progression-free survival, overall response rates, and disease control rates were also superior for enfortumab vedotin compared with chemotherapy. Outcomes for the chemotherapy group were as expected for patients with platinum-refractory disease5–7,24 and outcomes for the enfortumab vedotin group were consistent with survival and response rates from phase 1 and 2 studies.16,17 Although tissue samples were obtained for exploratory outcomes, Nectin-4 expression was not required for EV-301 trial entry, as high expression was observed in the vast majority of patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma in prior studies.16,17

The overall incidence of treatment-related adverse events was comparable between groups, including exposure-adjusted rates and those of grade ≥3 severity. Skin reactions, frequently characterized as maculopapular rash, are likely related to Nectin-4 expression in the skin.15,16 Peripheral neuropathy occurred at a higher rate with enfortumab vedotin, similar to prior studies.16,17 In phase 1 and 2 studies, peripheral neuropathy occurred in 49–50% of patients.16,17 Of the 50% of patients receiving enfortumab vedotin in EV-201 with treatment-related peripheral neuropathy, 76% of patients had resolution or grade 1 symptoms at the last follow-up.17 Hyperglycemia, observed in previous studies,16,17 occurred in a higher percentage of patients in the enfortumab vedotin group, although the precise mechanism remains unidentified. While most adverse events were mild-to-moderate in severity, some patients receiving enfortumab vedotin may experience serious adverse events and should be monitored for rash, peripheral neuropathy, and hyperglycemia. Rates of treatment-related death in the enfortumab vedotin group were in line with those seen in other recent trials for advanced, platinum-refractory urothelial carcinoma.6,25,26 Disease characteristics, preexisting conditions, comorbidities, and poor prognostic factors were potential confounders among patients who died in both groups. Due to the superior overall survival benefit observed at the planned interim analysis, EV-301 was stopped early. Future analyses of EV-301 quality-of-life data will further contextualize the efficacy and safety results.

The efficacy data from this trial suggest that enfortumab vedotin may play a role in the treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma. With recent data supporting maintenance treatment with the PD-L1 inhibitor avelumab after platinum-containing chemotherapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma, enfortumab vedotin may be considered at first relapse following maintenance immunotherapy.27 Phase 2 data for enfortumab vedotin in combination with pembrolizumab as first-line treatment for metastatic disease have led to a Food and Drug Administration Breakthrough Therapy designation28 based on high response rates and response duration.29 Additional evaluations of regimens containing enfortumab vedotin in the first-line (NCT04223856, NCT03288545) and perioperative (NCT03924895) settings are ongoing.

Patients with advanced urothelial carcinoma whose disease relapsed following platinum-containing chemotherapy and PD-1/L1 inhibitor treatment had significantly prolonged overall survival, progression-free survival, and a higher overall response rate after receiving enfortumab vedotin compared with chemotherapy. While skin reactions, peripheral neuropathy, and hyperglycemia toxicities can occur with enfortumab vedotin, these events were commonly mild-to-moderate in severity. Enfortumab vedotin therefore has the potential to become a global standard in the treatment of advanced urothelial carcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Stephanie Phan, PharmD, Regina Switzer, PhD, and Elizabeth Hermans, PhD (OPEN Health Medical Communications, Chicago, IL), and funded by Astellas Pharma, Inc. and Seagen Inc.

Author Disclosure and Conflicts of Interest

Thomas Powles reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Eisai, Exelixis, Incyte, Ipsen, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Merck Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Seagen; grants from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Eisai, Exelixis, Ipsen, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Merck Serono, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and Seagen; and other from AstraZeneca, Ipsen, MSD, Pfizer, and Roche.

Jonathan E Rosenberg reports personal fees from Adicet Bio, Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, BioClin, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai Pharma, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono/Pfizer, Fortress Biotech, GSK, Janssen Oncology, Merck, Mirati, QED Therapeutics, Roche/Genentech, Seagen, and Western Oncolytics; non-financial support from Astellas Pharma, Inc. and Seagen; and other from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novartis, Roche/Genentech, and Seagen.

Guru P Sonpavde reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bicycle Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Dava Oncology, Eisai, EMD Serono/Pfizer, Elsevier Practice Update, Exelixis, Genentech, Janssen, Medscape, Merck, Onclive, Physicians Education Resource, Research to Practice, Sanofi, Seagen, and Uptodate; other from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bavarian Nordic, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Debiopharm, QED, and Seagen; and grants from AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Sanofi.

Yohann Loriot reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Immunomedics, Janssen, Merck, MSD, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and Seagen; grants from Janssen and MSD; non-financial support from Janssen, MSD, and Roche.

Ignacio Durán reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Debiopharm, Immunomedics, Inc., Ipsen, Janssen, MSD, NCCN, Pharmacyclics, Roche Genentech, and Seagen; grants from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, and Roche Genentech; non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Ipsen, and Roche Genentech.

Jae-Lyun Lee reports personal fees from Astellas Korea, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS) Korea, Ipsen Korea, MSD Korea, Novartis Korea, Pfizer Korea, and Sanofi Aventis; grants from Ipsen Korea and Pfizer Korea; other from Astellas Korea, BMS Korea, Ipsen Korea, MSD Korea, Myovant Science Pfizer Korea, and Sanofi Aventis.

Nobuaki Matsubara reports personal fees from Chugai, Janssen, MSD, and Sanofi; and grants from Astellas Pharma, Inc., Chugai, Eli Lilly Taiho, Janssen, MSD, and Pfizer; and non-financial support from Astellas Pharma, Inc.

Christof Vulsteke reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), GSK, Ipsen, Merck, MSD, and Roche; grants from Leo Pharma.

Daniel Castellano reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), GSK, Ipsen, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche.

Chunzhang Wu is an employee of Astellas Pharma, Inc.

Mary Campbell is an employee of Seagen.

Maria Matsangou is an employee of Astellas Pharma, Inc.

Daniel P Petrylak reports personal fees from Ada Cap (Advanced Accelerator Applications), Amgen, Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bicycle Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Clovis Oncology, Exelixis, Incyte, Johnson & Johnson/Janssen, Lilly, Mirati, Monopteros, Pharmacyclics, Roche, Seagen, and Urogen; grants from Ada Cap (Advanced Accelerator Applications), Agensys, Astellas Pharma, Inc., AstraZeneca, Bayer, BioXcel Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers-Squibb (BMS), Clovis Oncology, Endocyte, Eisai, Genentech, Innocrin Pharma, Lilly, MedImmune, Medivation, Merck, Millennium, Mirati, Novartis, Pfizer, Progenics, Replimune, Roche, Sanofi, and Seagen; other from Bellicum Pharmaceuticals, Celgene, Sanofi, and TYME.

Footnotes

Data Sharing Statement

Researchers may request access to anonymized participant level data, trial level data and protocols from Astellas sponsored clinical trials at www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com.

For the Astellas criteria on data sharing see: https://clinicalstudydatarequest.com/Study-Sponsors/Study-Sponsors-Astellas.aspx

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamat AM, Bellmunt J, Galsky MD, et al. Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer consensus statement on immunotherapy for the treatment of bladder carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren M, Kolinsky M, Canil CM, et al. Canadian Urological Association/Genitourinary Medical Oncologists of Canada consensus statement: Management of unresectable locally advanced and metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Can Urol Assoc J 2019:318–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellmunt J, Orsola A, Leow JJ, et al. Bladder cancer: ESMO Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2014;25Suppl 3:iii40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bladder Cancer (Version 6.2020). National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (Accessed October 16, 2020, at https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/bladder.pdf.)

- 5.Bellmunt J, de Wit R, Vaughn DJ, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1015–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powles T, Duran I, van der Heijden MS, et al. Atezolizumab versus chemotherapy in patients with platinum-treated locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (IMvigor211): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391:748–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellmunt J, Theodore C, Demkov T, et al. Phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care compared with best supportive care alone after a platinum-containing regimen in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4454–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kersten K, Salvagno C, de Visser KE. Exploiting the immunomodulatory properties of chemotherapeutic drugs to improve the success of cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol 2015;6:516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bambury RM, Rosenberg JE. Advanced urothelial carcinoma: overcoming treatment resistance through novel treatment approaches. Front Pharmacol 2013;4:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dijk N, Funt SA, Blank CU, Powles T, Rosenberg JE, van der Heijden MS. The cancer immunogram as a framework for personalized immunotherapy in urothelial cancer. Eur Urol 2019;75:435–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu J, Armstrong AJ, Friedlander TW, et al. Biomarkers of immunotherapy in urothelial and renal cell carcinoma: PD-L1, tumor mutational burden, and beyond. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fradet Y, Bellmunt J, Vaughn DJ, et al. Randomized phase III KEYNOTE-045 trial of pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel, docetaxel, or vinflunine in recurrent advanced urothelial cancer: results of >2 years of follow-up. Ann Oncol 2019;30:970–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black PC, Alimohamed NS, Berman D, et al. Optimizing management of advanced urothelial carcinoma: A review of emerging therapies and biomarker-driven patient selection. Can Urol Assoc J 2020;14:E373–E82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadal R, Bellmunt J. Management of metastatic bladder cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2019;76:10–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Challita-Eid PM, Satpayev D, Yang P, et al. Enfortumab vedotin antibody-drug conjugate targeting Nectin-4 is a highly potent therapeutic agent in multiple preclinical cancer models. Cancer Res 2016;76:3003–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg J, Sridhar SS, Zhang J, et al. EV-101: A phase I study of single-agent enfortumab vedotin in patients with Nectin-4-positive solid tumors, including metastatic urothelial carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:1041–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg JE, O'Donnell PH, Balar AV, et al. Pivotal trial of enfortumab vedotin in urothelial carcinoma after platinum and anti-programmed death 1/programmed death ligand 1 therapy. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:2592–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Liu S, Wang L, et al. A novel PI3K/AKT signaling axis mediates Nectin-4-induced gallbladder cancer cell proliferation, metastasis and tumor growth. Cancer Lett 2016;375:179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Zhang J, Shen Q, et al. High expression of Nectin-4 is associated with unfavorable prognosis in gastric cancer. Oncol Lett 2018;15:8789–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bellmunt J, Fougeray R, Rosenberg JE, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized phase III trial of vinflunine plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in advanced urothelial carcinoma patients after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 2013;24:1466–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dreicer R, Manola J, Schneider DJ, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine and docetaxel in patients with advanced carcinoma of the urothelium: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Cancer 2003;97:2743–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCaffrey JA, Hilton S, Mazumdar M, et al. Phase II trial of docetaxel in patients with advanced or metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:1853–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaughn DJ, Broome CM, Hussain M, Gutheil JC, Markowitz AB. Phase II trial of weekly paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced urothelial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:937–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sridhar SS, Blais N, Tran B, et al. Efficacy and safety of nab-paclitaxel vs paclitaxel on survival in patients with platinum-refractory metastatic urothelial cancer: The Canadian Cancer Trials Group BL.12 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6:1751–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrylak DP, de Wit R, Chi KN, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum-based therapy (RANGE): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017;390:2266–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrylak DP, de Wit R, Chi KN, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel in patients with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum-based therapy (RANGE): overall survival and updated results of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:105–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powles T, Park SH, Voog E, et al. Avelumab maintenance therapy for advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1218–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Astellas and Seattle Genetics receive FDA Breakthrough Therapy designation for PADCEV™ (enfortumab vedotin-ejfv) in combination with pembrolizumab in first-line advanced bladder cancer. (Accessed December 18, 2020, at https://www.astellas.com/system/files/news/2020-02/20200220_en_1.pdf.)

- 29.Rosenberg JE, Flaig TW, Friedlander TW, et al. Study EV-103: Preliminary durability results of enfortumab vedotin plus pembrolizumab for locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. American Society of Clinical Oncology - Genitourinary Cancers Symposium; February14, 2020. Virtual Location, Abstract 441. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.