Summary

Introduction

Psychometric evaluation of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12), a well-used scale for measuring health-related quality of life (HrQoL), has not been done in general populations in Indonesia. This study assessed the validity and reliability of the SF-12 in middle-aged and older adults.

Methods

Participants self-completed the SF-12 and SF-36. Scaling assumptions, internal consistency reliability, and 1-week test-retest reliability were assessed for the SF-12. Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess its construct validity. Correlations between SF-12 and SF-36 component scores were computed to assess convergent and divergent validity. Effect size differences were calculated between SF-12 and SF-36 component scores for assessing criterion validity.

Results

In total, 161 adults aged 46-81 years (70% female) participated in this study. Scaling assumptions were satisfactory. Internal consistency for the SF-12 Physical Component Summary (PCS-12) and the Mental Component Summary (MCS-12) were acceptable (a = 0.72 and 0.73, respectively) and test-retest reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.88 and 0.75, respectively). A moderate fit of the original two-latent structure to the data was found (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.08). Allowing a correlation between physical and emotional role limitation subscales improved fit (RMSEA = 0.04). Correlations between SF-12 and SF-36 component summary scores support convergent and divergent validity although a medium effect size difference between PCS-12 and PCS-36 (Cohen’s d = 0.61) was found.

Conclusions

This study provides the first evidence that SF-12 is a reliable and valid measure of HrQoL in Indonesian middle-aged and older adults. The algorithm for computing SF-12 and its association with SF-36 in the Indonesian population warrant further investigation.

Keywords: Internal consistency, Test-retest reliability, Factor analysis, Validity

Introduction

Indonesia’s population is ageing [1]. Currently, one in four Indonesians is aged over 45 years, and by 2035, more than 100 million Indonesians are expected to be aged over 45 years with 30 million of these aged over 65 years [2]. As morbidity increases with age, there is a growing interest in instruments that measure health-related quality of life (HrQoL), a multidimensional concept that includes physical, psychological, and social domains of health [3, 4]. HrQoL is increasingly being accepted as an important patient-reported outcome measure in health care, including among middle and older adult populations [5].

Generic and disease-specific instruments are used for measuring HrQoL [4]. The Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) is one of the most widely used generic instrument. It consists of 36 items, 35 of which are divided into eight subscales that can be summarised into two component summary scores, one for physical health (PCS-36) and the other for mental health (MCS-36) [6]. The SF-36 has been shown to have high internal consistency reliability and high convergent and discriminant validity in Indonesian middle-aged and older adults [7].

The 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) was developed from the SF-36 as a shorter instrument that would reproduce physical and mental health component summary scores (PCS-12 and MCS-12) [8]. Having fewer items, the SF-12 can be completed by most participants in less than a third of the time needed to complete the SF-36 [8]. Thus, it can be used by researchers and practitioners wanting to reduce participant burden.

The reliability and validity of the SF-12 have been widely documented worldwide. The scale has been validated in general populations in many countries including Tunisia [9], Iran [10], China [11], Greece [12], Australia [13], Israel [14] and European countries [15]. It has been found to valid and reliable in older adults in Sweden [16], Israel [17], the US [18-20], the UK [21] and China [22, 23]. Furthermore, SF-12 component summary scores have been shown to be valid measures of HrQoL in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [24], immune deficiencies [25], mental health disorders [26], low back pain [27], retinal diseases [28], osteoarthritis [29], obesity [30], diabetes [31], stroke [32] and coronary heart disease [33]. The SF-12 has not been validated in general populations of middle-aged and older Indonesians.

In the initial development of the SF-12 and SF-36 in the US, the scales were found to be highly correlated, and scores on PCS-12 and MCS-12 each explained about 90% of the variation in the corresponding SF-36 component summary score [8]. Findings from subsequent studies suggest that the factor structure of the SF-12 in some countries many not follow the scale’s initial structure [17, 20, 27]. Thus, it is unclear whether these scales can be used interchangeably in Indonesia.

In Indonesia, the SF-12 has been used minimally, in only two studies as a patient-reported outcome measure [34, 35]. The limited use of the SF-12 is partly due to the lack of its validation in the Indonesian general population as it has only been validated in Indonesian patients with cardiovascular disease [33] and rheumatoid arthritis [36]. The validation of the SF 12 in the general population would likely increase its use more broadly to community settings throughout Indonesia. After validation, it is expected to be used to assess the burden of disease in communities and monitor progress in achieving the nation’s health objectives [37]. As a short HrQoL instrument, it is also expected to be used in clinical settings to supplement objective clinical or biological measures of disease for assessing the quality of services, the need for health care, and the effectiveness of interventions, as well as for cost utility analysis [38]. Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the SF-12 in Indonesia middle-aged and older adults. We assessed scaling assumptions, internal consistency and test-retest reliabilities, and construct validity. We also assessed criterion validity with the SF-36 serving as the criterion, to justify the use of the SF-12, particularly as an alternative to the more time-consuming SF-36, in Indonesia.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND STUDY SAMPLE

This study assessed the psychometric properties of the Indonesian version of the SF-12 using guidelines from the International Quality of Life Project [15, 39]. The sample size calculation followed the recommendation of Jackson [40], who indicated a sample of at least 10 participants per item or parameter. As the SF12 contains 12 items, at least 120 participants were required for this study. To achieve this number, we invited 200 members of two organisations that offered educational and health services to middle-aged and older adults in the City of Yogyakarta through the organisations’ community leaders. We expected a response rate of 60%. Members with mental or physical impairments that hindered participation were excluded. Participants provided written informed consent.

DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES AND MEASURES

All data collection took place in the community halls of the two organisations. At an initial visit and a follow-up visit 1 week later, participants self-completed a paper-based questionnaire that included the SF-12, the SF-36 and socio-demographic questions.

Short-form 12 (SF-12)

The SF-12 consists of 12 items within eight subscales [8, 41]. As shown in Table I, six items from four subscales are used to generate a physical component summary score (PCS-12). These subscales measure general health perception (GH), physical functioning (PF), role limitation due to physical health (RP) and bodily pain (BP). Another six items from another four subscales are used to create a mental component summary score (MCS-12) [41]. These subscales measure role limitations due to emotional problems (RE), vitality (VT), mental health (MH), and social functioning (SF) [8]. Higher scores on PCS indicate better physical HrQoL, and higher scores on MCS indicate better mental HrQoL.

Tab. I.

The Indonesian SF-12 factor structure and number of response options.

| Component | Subscales | Item code | Number of response options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical component score (PCS-12) |

General health | Item 1 | 5 |

| Physical health | Item 2 and 3 | 3 | |

| Role-physical | Item 4 and 5 | 2 | |

| Bodily pain | Item 8 | 5 | |

| Mental component score (MCS-12) |

Role-emotional | Item 6 and 7 | 2 |

| Mental health | Item 9 and 11 | 6 | |

| Vitality | Item 10 | 6 | |

| Social function | Item 12 | 5 |

Four items were reversed scored: the General health item (item 1), the Bodily pain item (item 8), one Mental health item (item 9; ‘Felt calm and peaceful’) and the Vitality item (item 10).

Raw item scores were transformed into a 0 (the worst) to 100 (the best) scale [41]. The mean score of the transformed items within a subscale was computed to obtain the subscale score. Item and subscale scores were not standardised. This summated rating method of scoring assumes that item and subscale scores can be transformed without standardisation of scores or item weighting [8, 41, 42]. To calculate PCS-12 and MCS-12 scores, a norm-based scoring algorithm empirically derived from US population data was used, as suggested by Ware [41] because no algorithm has been developed for the Indonesian population. The US algorithm has been validated in other countries where country-specific algorithms are absence [8].

Short-form 36 (SF-36)

The SF-36 [6], administered as a separate scale from the SF-12 in this study, was used to validate the SF-12. It contains 36 items, 35 of which are within the same eight subscales as in the SF-12. Likewise, two component summaries (PCS-36 and MCS-36) can be created. These were created using a summated method suggested by Hays [6]. The summary scores then were transformed into standardized T scores [6].

SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

Participants were asked about socio-demographic characteristics, which included age, sex, marital status, and two measures of socio-economic status: education and employment.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To assess whether the assumptions for creating subscales and the summated scoring from the items were justified, we used data collected from the initial visits with participants. Four assessments were conducted, as suggested by Leung [43]. First, we assessed whether there was equality in item variance. All subscale items should have similar standard deviations and means; otherwise, the computation of subscale scores would require standardisation. Second, we assessed the equality of item-subscale correlations. Subscale items should have similar corrected item-subscale correlations that are ≥ 0.40. Third, we assessed the floor and ceiling effects of subscales and component summaries. The percentage of participants with scores at the minimum value (floor) and maximum value (ceiling) should be < 20% to ensure scores capture the full range of responses in the population and that changes can be detected over time. Last, we assessed item discriminant validity, by determining whether the correlation between each item and its corresponding component summary score was significantly higher than its correlation with the other component summary score. Spearman correlation coefficients were computed for this analysis.

We then conducted tests of reliability. Internal consistency reliability was assessed by calculating Cronbach’s alpha for each subscale and component summary. A Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70 signified acceptable reliability [44]. The 1-week test-retest reliability of each component summary was assessed by calculating the intra-class correlation (ICC) of items within the component summary (1-way average model). An ICC > 0.60 was considered good, and an ICC > 0.75 was judged excellent [45].

For construct validity, we first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess whether the hypothetical factor structure, using the maximum likelihood estimation [8, 41] fit the observed data. The hypothetical structure allowed for correlations between PCS and MCS but not between subscales [8, 41]. Model modification indices were generated to guide model specification if the fit was not good. A good fit required a χ2/df ratio of < 3.00 [46]. A root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of < 0.08 indicated a good fit whereas a value between 0.08 and 0.10 indicated moderate fit [47]. Values > 0.90 for the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) and values < 0.08 for the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) indicated an adequate fit [48]. We also assessed factor loadings of subscales onto composite summaries. As suggested by Shevlin [49], factor loadings of 0.30 to < 0.50 were considered low, 0.50 to < 0.70 as medium, and ≥ 0.70 as high.

Next, divergent validity was assessed by evaluating the correlations (i) among subscales, (ii) between a subscale and the composite summary that does not include that subscale and (iii) between PCS-12 and MCS-12. Divergent validity was demonstrated if correlations were weak (r < 0.40). Convergent validity was assessed by evaluating the correlations (i) between each subscale and the composite summary that includes that subscale and (ii) between PCS-12 and PCS-36 and between MCS-12 and MCS-36. The convergent validity was demonstrated if correlations were strong (r > 0.60). Correlations between 0.40 to 0.60 were considered moderate [10, 22]. Spearman correlation coefficients were computed for these analyses.

Last, criterion validity was assessed by calculating effect size differences between SF-12 and SF-36 component summary scores. The effect size difference was calculated by dividing the difference in scores by the pooled standard deviation. It has been suggested that an effect size of < 0.20 I very small; 0.20 to 0.49 is small; 0.50-0.79 is medium; and ≥ 0.80 is large [50]. Effect size < 0.20 demonstrated acceptable criterion validity.

Data were analysed using SPSS® version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), except for CFA, for which Stata 15 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, US) was used. For all tests, statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS

In total, 161 participants (response rate = 80.5%) completed the first data collection, above the minimal sample size required for the analysis. They were aged 46 to 81 years with a mean age of 62.7 ± 7.9 years and were predominantly female, married, with no tertiary education, and unemployed/retired. The 70 participants who returned to complete the test-retest reliability assessment (43%) did not differ significantly on any of these characteristics from the 91 participants who did not return for this assessment (p > 0.05) (Tab. II).

Tab. II.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristics | Total sample (n = 161) n (%) |

Test-Retest sample (n = 70) n (%) |

P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.14 | ||

| < 65 | 82(51) | 31(44) | |

| ≥ 65 | 79(49) | 39(56) | |

| Sex | 0.81 | ||

| Female | 112(70) | 48(69) | |

| Male | 49(30) | 22(31) | |

| Marital status | 0.31 | ||

| Married | 117(73) | 48(69) | |

| Not married/widowed | 44(27) | 22(31) | |

| Education levels | 0.81 | ||

| Primary/secondary | 92(57) | 38(54) | |

| Tertiary | 69(43) | 32(46) | |

| Employment status | 0.84 | ||

| Employed | 17(11) | 7(10) | |

| Unemployed/retired | 144(89) | 63(90) |

* Tested differences between participants who returned for the test-retest reliability and those who did not.

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND SCALING ASSUMPTIONS

The descriptive statistics for assessing the scaling assumptions for the SF-12 item, subscale, and component summary scores are presented in Table III. For each subscale, the means and standard deviations of the items were similar, except for the PF subscale, for which Item 2 had a higher mean than Item 3. The standard deviations of those two items, however, were similar. These results show that there was equality in item variance within subscales. The corrected item-subscale correlations were acceptable (r ≥ 0.40), except for the BP item (r = 0.39) and the first RE item (RE1; r = 0.38). The percentage of participants with subscale scores at the minimum or maximum values was > 20% for all subscales except GH and MH, showing that most subscales had floor or ceiling effects. However, no floor and ceiling effects were found for PCS-12 or MCS-12. The item discriminant validity assessment indicated that the correlation between each item and its corresponding composite summary was higher than the correlation between the item and the other composite summary score. Therefore, each item demonstrated item discriminant validity.

Tab. III.

Summary of assessments of item, subscale and component score assumptions (n = 161).

| Mean | SD | Floor % |

Ceiling % |

Corrected item -subscale | Item - PCS-12 |

Item- MCS-12 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Health Component * | 44.40 | 8.29 | 0.62 | 0.62 | - | - | - |

| General Health (GH): health rating | 44.72 | 19.85 | 1.86 | 3.73 | 0.40 | 0.63 | 0.31 |

| Physical Function (PF) ^ | 75.93 | 23.37 | 1.86 | 36.65 | - | ||

| Limited in moderate activities (PF1) | 86.02 | 24.50 | 1.86 | 73.91 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.06 |

| Limited in climbing several stairs (PF2) | 65.84 | 29.80 | 6.83 | 38.51 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.24 |

| Physical Role Limitation (RP) ^ | 63.98 | 41.16 | 23.60 | 51.61 | - | ||

| Accomplished less due to physical health (RP1) | 63.35 | 48.33 | 36.65 | 63.35 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 0.29 |

| Limited in kind of work (RP2) | 64.60 | 47.97 | 35.40 | 64.60 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.17 |

| Bodily Pain (BP): Pain interferes with work | 64.44 | 27.62 | 23.60 | 76.40 | 0.39& | 0.62 | 0.17 |

| Mental Health Component * | 49.51 | 9.48 | 0.62 | 0.62 | - | ||

| Emotional Role Limitation (RE) ^ | 72.67 | 37.89 | 16.14 | 61.49 | - | ||

| Accomplished less due to emotional health (RE1) | 76.40 | 42.60 | 31.06 | 68.94 | 0.38 & | 0.24 | 0.41 |

| Not work as carefully (RE2) | 68.94 | 46.42 | 4.97 | 22.36 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.53 |

| Vitality (VT): have a lot of energy (VT) | 68.32 | 19.31 | 0.62 | 19.88 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.58 |

| Mental Health (MH)^ | 68.01 | 20.03 | 0.62 | 8.69 | - | ||

| Felt calm and peaceful (MH1) | 70.43 | 22.03 | 0.62 | 13.66 | 0.68 | 0.26 | 0.74 |

| Felt downhearted and blue (MH2) | 65.59 | 22.27 | 0.62 | 14.29 | 0.52 | 0.32 | 0.67 |

| Social Function: physical/emotional interfere with social | 76.24 | 23.68 | 0.62 | 36.65 | 0.47 | 0.18 | 0.58 |

*: using US algorithm to create a standardised score on a 0 to 100 scale;

^: mean of the two subscale items; all other subscales are composed of one item;

Bold: highest correlation Item-PCS-12 an Item-MCS-12 are item-scale correlations (using Spearman correlation);

#: floor and ceiling % was the proportion of participant with lowest and highest responses;

&: A correlation < 0.40 indicates that the assumption of equality of item-subscale correlations was not supported.

INTERNAL CONSISTENCY AND TEST AND RETEST RELIABILITIES

The Cronbach alphas for PCS-12 (a = 0.72) and MCS-12 (a = 0.73) indicated acceptable internal consistency reliability. The ICC of items within PCS-12 (ICC = 0.88; 95% CI: 0.81-0.92) and within MCS-12 (0.75; 95% CI: 0.62-0.84) demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability of both composite summaries.

CONFIRMATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS

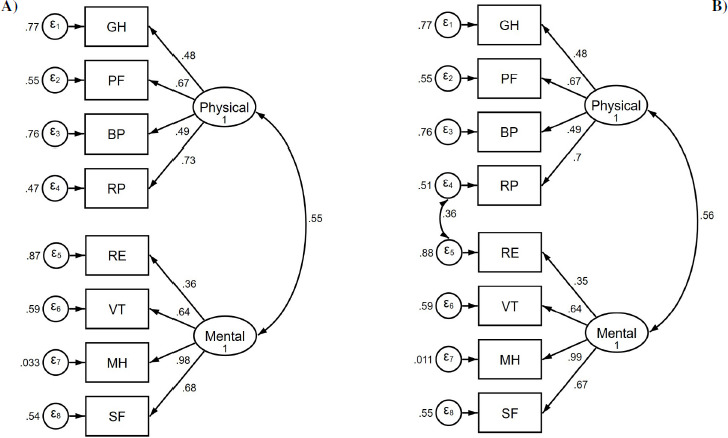

Figure 1 illustrates the factor loadings for both the original (Fig. 1a) and a modified factor structure (Fig. 1b), and Table IV summarises the structures’ fit statistics. All fit indices except one (RMSEA = 0.08) indicated a moderate fit of the original structure to the data. The model specification suggested a correlation between RP and RE, and thus, in the modified structure, RP and RP were allowed to correlate. As a result, all fit indices indicated a good fit including RMSEA (= 0.04). In both structures, only RE, GH and BP loaded poorly into their composite summary (factor loadings < 0.50).

Fig. 1.

The original structure (1A) and the modified structure (1B) of the Indonesian version of the SF-12 in a sample of middle-aged to older Indonesians. Each abbreviation is a separate subscale of the SF-12.

Tab. IV.

Goodness-of-fit statistics of the original and the modified SF-12 structure (n = 161).

| Hypothesised structure | Modified structure | |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | 2.04 | 1.26 |

| RMSEA (90% CI) | 0.08 (0.04-0.12) | 0.04 (0.00-0.09) |

| CFI | 0.94 | 0.99 |

| TLI | 0.92 | 0.98 |

| SMSR | 0.07 | 0.05 |

df: degree of freedom; RMSEA: root mean square approximation; CFI: comparative fit index; TLI: Tucker Lewis index; SMSR: standardised root mean square residual.

CONVERGENT AND DIVERGENT VALIDITY

As shown in Table V, divergent validity of the subscales was partially supported with weak inter-subscale correlations (r < 0.40), except for correlations between RP and PF (r = 0.46), RR and RE (r = 0.43), MH and SF (r = 0.66), and MH and VT (r = 0.60) Divergent validity was supported by weak correlations between MCS-12 and each subscale of PCS-12 and between PCS-12 and each subscale of MCS-12 (r < 0.40) and by a weak correlation between PCS-12 and MCS-12 (r = 0.17). There was support for convergent validity as there were strong correlations between subscales and their corresponding composite summary (r > 0.60), except for the correlations between MCS-12 and three subscales, RE (r = 0.57), VT (r = 0.58) and SF (r = 0.58), which were slightly below the threshold. Convergent validity was also supported by strong correlations between MCS-12 and MCS-36 and between PCS-12 and PCS-36 (r > 0.60).

Tab. V.

Correlations among subscales and composite summaries computed for assessing convergent and divergent validity.

| GH | PF | RP | BP | RE | VT | MH | SF | PCS-12 | MCS-12 | PCS-36 | MCS-36 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GH | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| PF | 0.30 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| RP | 0.39 | 0.46 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| BP | 0.25 | 0.31 | 0.31 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| RE | 0.28 | 0.21 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 1.00 | |||||||

| VT | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 1.00 | ||||||

| MH | 0.23 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.60 | 1.00 | |||||

| SF | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.66 | 1.00 | ||||

| PCS-12 | 0.63 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 1.00 | |||

| MCS-12 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 1.00 | ||

| PCS-36 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.46 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 1.00 | |

| MCS-36 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 1.00 |

GH: general health; PF: physical function; RP: role-physical; BP: bodily pain; VT: vitality; RE: role-emotional; MH: mental health; SF: social functioning; PCS: physical component summary; MCS: mental component summary; Note: Statistics in the table are Spearman correlation coefficients.

CRITERION VALIDITY

The effect size difference between PCS-12 and PCS-36 was 0.61, a medium effect size. The difference between MCS-12 and MCS-36 was 0.05, a very small effect size. Thus, criterion validity was demonstrated for MCS-12 but not for PCS-12.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate the psychometric properties of the SF-12 in a general Indonesian population. The overall findings provide satisfactorily evidence that the Indonesian version of SF-12 is a reliable and valid scale that can be used in monitoring and measuring HrQoL in middle-aged and older adults in Indonesia. These results thus add Indonesia and the Indonesian language to the growing list of cultures and languages for which the SF-12 is valid.

The mean scores for PCS-12 and MCS-12 in our study were 44.4 and 49.5, respectively. The lower PCS-12 score was also reported in studies of adults aged ≥ 60 years residing in community and nursing home settings in Guangzhou, China (39.9 and 49.1 for PCS-12 and MCS-12, respectively) [23], of Swedes aged ≥ 75 years (37.5 and 50.3, respectively) [16], and of community-dwelling African Americans aged ≥ 60 years (42.7 and 51.9, respectively). Similarly, community-dwelling adults aged ≥ 70 years in Israel had lower raw scores on subscales within PCS-12 than on subscales within MCS-12 [17]. The lower PCS-12 than MCS-12 scores seen in our study and in these previous studies were not seen in a validation study of adults of all ages (e.g., aged ≥ 18 years) in nine European countries and the US [15]. In that study, mean scores were approximately 50.0 for both PCS-12 and MCS-12 [15]. The findings of our study and of these studies together suggest that physical HRQoL is negatively affected more than mental HRQoL as we age.

We also found that the mean and standard deviation was equivalent for all SF-12 items except for Items 2 and 3. Item 2 asks about physical function in conducting moderate activities, and Item 3 asks about physical function in conducting vigorous activities. Given our population was composed of middle-aged and older adults, it was not surprising that Item 2 would have a higher mean than Item 3. This finding has been shown in other studies [17, 22]. The standard deviations, however, were comparable between these items, supporting the summation of these items into a subscale.

Although most subscales showed floor or ceiling effects, no floor or ceiling effects were observed for the SF-12 composite summaries, indicating the ability of PCS-12 and MCS-12 to capture a full range of health states in our study population. Our findings were similar to the findings in a general population in Iran [10]. In that study the percentage of participants who scored at the lowest level (i.e., floor effect) and highest level (i.e. ceiling effect) was less than 1% for PCS-12 and for MCS- 12. Our findings do not, however, support findings from two Israeli studies, one of a general adult population [14] and the other of an older adult population [17]. Those studies showed minimal floor and ceiling effects in items with more than three response options. We found acceptable corrected item-scale correlations for all but two items for which correlations were slightly below the threshold for acceptable. Consistently high correlations between items and their corresponding component summary score were also found in two previous studies of older adults in China [22, 23]. Although we found acceptable items’ equivalency and discriminant validity as well minimal floor and ceiling effects for PCS-12 and MCS-12, the considerable ceiling or floor effects were found for most subscales, thus, the assumptions for creating subscales for summated scoring the items in our study population warrant further investigation.

Internal consistency reliability of the component summaries was supported. Internal consistency values were similar to those reported previously for a sample of Indonesian patients with cardiovascular disease (PCS-12: a = 0.79; MCS-12: a = 0.77) [33] and from a sample of adults from the Iranian general population (PCS-12: a = 0.73; MCS-12 a = 0.72) [10]. However, higher values have been reported for other populations including for older adults in Israel (PCS-12: a = 0.86; MCS-12: a = 0.71 [17]) and for a general population in Sweden (PCS-12: a = 0.85; MCS-12: a = 0.76) [16], and for a general population in China (PCS-12: a = 0.81; MCS-12: a = 0.83) [23]. Nonetheless, all these findings support the internal consistency reliability of SF-12 across different populations including in our study population.

Our study showed that the component summaries have good 1-week test-retest reliability (PCS-12: ICC = 0.88; MCS-12: ICC = 0.75) in middle-aged and older Indonesians. Other studies have shown acceptable test-retest reliability of the SF-12 in different populations, such as in a general population in Israel (PCS-12: ICC = 0.92; MCS-12: ICC = 0.85) [14] and in a general US population (PCS-12: ICC = 0.89; MCS-12: ICC = 0.76 [8]. Our findings thus support those of previous studies.

We showed that the original two-factor structure of the SF-12 moderately fitted our data (RMSEA = 0.08). The fit of data to this structure has varied across studies. A study from Iran [10] showed a moderate fit (RMSEA = 0.09), as we did. In contrast, in samples of older adults in China [23] the structure fit the data fit well (RMSEA < 0.08) whereas in a general Danish population [51] the fit was poor (RMSEA = 0.12). Our findings along with these previous findings suggest that the algorithms used for creating component summary scores may need to be modified for different populations. Furthermore, we found a low factor loading for the RE subscale. The modification indices suggested that RE and RP be correlated. The wordings and response options of these subscales were almost identical. They only differed in whether limitations were caused by physical or emotional problems; thus, adding a correlation between these subscales appears to be plausible. Adding the correlation improved model fit (RMSEA = 0.04). This evidence further suggests that specific scoring algorithms for specific populations may be required.

As expected, the correlations between the subscales that compose PCS-12 (PF, RP, BP and GH) and PCS-12 were stronger than the correlations between these subscales and MCS-12. Likewise, the correlations between the subscales that compose MCS-12 (VT, SF, RE and MH) and MCS-12 were stronger than the correlations between these subscales and PCS-12. These findings support the convergent and divergent validity of the subscales, as shown in previous studies of older adults in China [22].

We also found moderate correlations between PCS-12 and PCS-36 (r = 0.64) and between MCS-12 and MCS-36 (r = 0.62), findings that support the component summaries’ convergent validity. Moderate correlations were also found in the study of older adults in China [22]. Our estimates, however, were lower than those reported in the initial validation study of the US general population [8], in a study of the Australia general population (r ≥ 0.95) [13], and in a study in the general Hong Kong population (r ≥ 0.94). One explanation for the difference in findings between our study and findings of these previous studies was the difference in the administration of the SF-12. The researchers in the earlier studies administered the SF-36 only and then selected out the items used in the SF-12 for validating the SF-12. We administered the SF-12 separately from the administration of the SF-36, which could have resulted in lower correlations between SF-12 and SF-36 component summaries. Our lower correlations consequently decreased the total variance of the SF-36 that could be explained by the SF-12. Additional studies are required to explore further whether the SF-12 adequately replicates the SF-36 in the Indonesian context. As the previous studies’ estimates were derived from general populations with wider age spans and with relatively large sample sizes [8, 13], exploration of the convergent validity in Indonesia likewise may require a more heterogenous and larger sample.

Last, we found a considerable effect size difference between PCS-36 and PCS-12 (Cohen’s d = 0.60) although a negligible effect size difference between MCS-36 and MCS-12 (Cohen’s d = 0.05). The responses to SF-12 items were weighted using a US-standard algorithm, and so our findings raise a question about the appropriate algorithms used for weighing items within PCS-12 in our population. Therefore, further investigation into appropriate regression weights for the Indonesian version of PCS-12 is needed. Finally, although the component summary scores of the SF-12 may not fully capture those in the SF-36, the overall evidence suggests that the Indonesian version of the SF-12 possesses adequate reliability and validity for use in populations of healthy, community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults in Indonesia.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATION

A major strength of our study was that we thoroughly investigated the psychometric properties of the Indonesian SF-12 using well-used guidelines [15, 39]. Another strength was that we gave participants the SF-12 and SF-36 as separate surveys. In most other validation studies of the SF-12 the SF-36 was administered, and the 12 relevant items were selected from the SF-36 to create the SF-12. Our approach better replicates what would be expected when the SF-12 is used as an alternative to the SF-36. Another strength was that we used the US norm-based scoring algorithms commonly used in studies worldwide for calculating PCS-12 and MCS-12 [41]; therefore, our results can be used for cross-cultural HrQoL comparisons with other studies that use the same algorithms. However, caution is warranted in making comparisons to studies that use version 2 of SF-12 (we used version 1), that recruit participants with dissimilar characteristic to our participants (ours were generally healthy, community-dwelling adults), or that administer the SF-12 using other modes (in this study the SF-12 was self-administered and was separately measured from the SF-36).

Limitations of the study also need to be acknowledged. First, although the packet of surveys was self-administered, staff supervised the process and asked participants to complete the surveys. Our findings might not be replicated if surveys were self-administered without supervision. Second, the ratio of participants to number of items/parameters in this study was above 10:1, an acceptable sample size for CFA analysis, as suggested by Jackson [40]; however, the ratio was below the sample size for CFA of at least 200 participants that is recommended by Myers [52]. Third, the study was conducted in a community-dwelling setting, thereby limiting the generalizability to other populations including adults in residential care and younger adults.

Conclusions

This study provides the first evidence that the SF-12 is a reliable and valid measure of HrQoL in Indonesian middle-aged and older adults. The study also provides preliminary evidence that the MCS-12 can be used instead of the MCS-36, the gold standard measure of mental HRQoL, but that a more appropriate algorithm for computing PCS-12 scores for the Indonesian middle-aged and older populations is warranted. To further establish the validity of the Indonesian version of the SF-12, psychometric testing of the scale in younger populations is warranted, to assess whether our findings apply to younger age groups. In addition, studies of responsiveness to change over time are warranted, to determine whether the scale is sensitive to time-related changes in health status, critical for use in health care settings.

Figures and tables

Acknowledgements

Funding sources: this study was funded by a Post-Doctoral Research Grant 2019 from Yogyakarta State University Indonesia No 10/Penelitian/Pasca Doktor/UN34.21/2019.

We would like to thank Prijo Sudibjo, Cerika Rismayanthy, Krisnanda Apriyanto and students in the Sports Science Faculty Yogyakarta State University for their assistance with the data collection.

Footnotes

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Gadjah Mada University (approval No. KE/0142/02/2019).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: NIA. Data curation: NIA. Formal analysis: NIA, KCH. Funding acquisition: NIA. Methodology: NIA, KCH. Project administration: NIA. Visualization: NIA: Writing - original draft: NIA, KCH. Writing - review & editing: NIA, KCH.

References

- [1].Adioetomo SM, Mujahid G. Indonesia on the threshold of population ageing. https://indonesia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/BUKU_Monograph_No1_Ageing_03_Low-res.pdf (accessed on 27/11/2020).

- [2].Jones GW. Indonesia population projection 2010-2035. https://indonesia.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/Policy_brief_on_The_2010_%E2%80%93_2035_Indonesian_Population_Projection.pdf (accessed on 25/11/2020).

- [3].Sajid M, Tonsi A, Baig M. Health-related quality of life measurement. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2008. https://doi.org/10.4103/0975-1483.93568 10.4103/0975-1483.93568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lin X-J, Lin I-M, Fan S-Y. Methodological issues in measuring health-related quality of life. TCMJ 2013;25:8-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tcmj.2012.09.002 10.1016/j.tcmj.2012.09.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bottomley A, Reijneveld JC, Koller M, Flechtner H, Tomaszewski KA, Greimel E, Ganz PA, Ringash J, O’connor D, Kluetz PG. Current state of quality of life and patient-reported outcomes research. Eur J Cancer 2019;121:55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.016 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Mazel RM. The Rand 36-item Health Survey 1.0. Health Econ 1993;2:217-227. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.4730020305 10.1002/hec.4730020305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Arovah NI, Heesch KC. Verification of the reliability and validity of the Short Form 36 Scale in Indonesian middle-aged and older adults. J Prev Med Public Health 2020;53:180-188. https://doi.org/10.3961/jpmph.19.324 10.3961/jpmph.19.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996:220-233. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Younsi M. Health-related quality-of-life measures: evidence from Tunisian population using the SF-12 health survey. Value Health Reg Issues 2015;7:54-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2015.07.004 10.1016/j.vhri.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Mousavi SJ, Omidvari S. The Iranian version of 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12): factor structure, internal consistency and construct validity. BMC Public Health 2009;9:341. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-341 10.1186/1471-2458-9-341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lam CL, Eileen Y, Gandek B. Is the standard SF-12 Health Survey valid and equivalent for a Chinese population? Qual Life Res 2005;14:539-547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-0704-3 10.1007/s11136-004-0704-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Kontodimopoulos N, Pappa E, Niakas D, Tountas Y. Validity of SF-12 summary scores in a Greek general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-55 10.1186/1477-7525-5-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sanderson K, Andrews G. The SF-12 in the Australian population: cross-validation of item selection. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002;26:343-345. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00182.x 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2002.tb00182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Amir M, Lewin-Epstein N, Becker G, Buskila D. Psychometric properties of the SF-12 (Hebrew version) in a primary care population in Israel. Med Care 2002;40:918-928. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200210000-00009 10.1097/00005650-200210000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplege A, Prieto L. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1171-1178. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00109-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jakobsson U. Using the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) to measure quality of life among older people. Aging Clin Exp Res 2007;19:457-464. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324731 10.1007/BF03324731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bentur N, King Y. The challenge of validating SF-12 for its use with community-dwelling elderly in Israel. Qual Life Res 2010;19:91-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9562-3 10.1007/s11136-009-9562-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Resnick B, Nahm ES. Reliability and validity testing of the revised 12-item Short-Form Health Survey in older adults. J Nurs Meas 2001;9:151-161. https://doi.org/1061-3749.9.2.151 10.1891/1061-3749.9.2.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cernin PA, Cresci K, Jankowski TB, Lichtenberg PA. Reliability and validity testing of the Short-Form Health Survey in a sample of community-dwelling African American older adults. J Nurs Meas 2010;18:49-59. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.18.1.49 10.1891/1061-3749.18.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Resnick B, Parker R. Simplified scoring and psychometrics of the revised 12-item Short-Form Health Survey. Outcomes Manag Nurs Pract 2001;5:161-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pettit T, Livingston G, Manela M, Kitchen G, Katona C, Bowling A. Validation and normative data of health status measures in older people: the Islington study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16:1061-1070. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.479 10.1002/gps.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shou J, Ren L, Wang H, Yan F, Cao X, Wang H, Wang Z, Zhu S, Liu Y. Reliability and validity of 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) for the health status of Chinese community elderly population in Xujiahui district of Shanghai. Aging Clin Exp Res 2016;28:339-346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-015-0401-9 10.1007/s40520-015-0401-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shu-Wen S, Dong W. The reliability and validity of Short Form-12 Health Survey version 2 for Chinese older adults. Iran J Public Health 2019;48:1014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Islam N, Khan IH, Ferdous N, Rasker JJ. Translation, cultural adaptation and validation of the English “Short Form SF 12v2” into Bengali in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0683-z 10.1186/s12955-017-0683-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chariyalertsak S, Wansom T, Kawichai S, Ruangyuttikarna C, Kemerer VF, Wu AW. Reliability and validity of Thai versions of the MOS-HIV and SF-12 quality of life questionnaires in people living with HIV/AIDS. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-15 10.1186/1477-7525-9-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Salyers MP, Bosworth HB, Swanson JW, Lamb-Pagone J, Osher FC. Reliability and validity of the SF-12 Health Survey among people with severe mental illness. Med Care 2000;38:1141-1150. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-200011000-00008 10.1097/00005650-200011000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ibrahim AA, Akindele MO, Ganiyu SO, Kaka B, Abdullahi BB, Sulaiman SK, Fatoye F. The Hausa 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12): translation, cross-cultural adaptation and validation in mixed urban and rural Nigerian populations with chronic low back pain. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232223. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232223 10.1371/journal.pone.0232223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Globe DR, Levin S, Chang TS, Mackenzie PJ, Azen S. Validity of the SF-12 quality of life instrument in patients with retinal diseases. Ophthalmology 2002;109:1793-1798. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01124-7 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01124-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Webster KE, Feller JA. Comparison of the Short Form-12 (SF-12) health status questionnaire with the SF-36 in patients with knee osteoarthritis who have replacement surgery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016;24:2620-2626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3904-1 10.1007/s00167-015-3904-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wee CC, Davis RB, Hamel MB. Comparing the SF-12 and SF-36 health status questionnaires in patients with and without obesity. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-11 10.1186/1477-7525-6-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kathe N, Hayes CJ, Bhandari NR, Payakachat N. Assessment of reliability and validity of SF-12v2 among a diabetic population. Value Health 2018;21:432-440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.007 10.1016/j.jval.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Okonkwo OC, Roth DL, Pulley L, Howard G. Confirmatory factor analysis of the validity of the SF-12 for persons with and without a history of stroke. Qual Life Res 2010;19:1323-1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9691-8 10.1007/s11136-010-9691-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wicaksana AL, Maharani E, Hertanti NS. The Indonesian version of the Medical Outcome Survey-Short Form 12 version 2 among patients with cardiovascular diseases. Int J Nurs Pract 2020;26:e12804. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12804 10.1111/ijn.12804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jumayanti J, Wicaksana AL, Sunaryo EYAB. Quality of life in patients with cardiovascular in Yogyakarta. Jurnal Kesehatan 2020;13:1-12. https://doi.org/10.23917/jk.v13i1.11096 10.23917/jk.v13i1.11096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Widhowati FI, Farmawati A, Dewi FST. Factors influencing quality of life among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Sleman Yogyakarta: an analysis from the HDSS data 2015-2017. VISIKES;19:98-108. http://publikasi.dinus.ac.id/index.php/visikes/article/view/3765 (accessed on 10/11/2020). [Google Scholar]

- [36].Falah NM, Putranto R, Setyohadi B, Rinaldi I. Reliability and validity test of Indonesian version Short Form 12 quality of life questionnaire in rheumatoid arthritis patients. J Penyakit Dalam Indones 2017;4:105-111. https://doi.org/10.7454/jpdi.v4i3.129 10.7454/jpdi.v4i3.129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Measuring healthy days: population assessment of health-related quality of life. https://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/pdfs/mhd.pdf (accessed on 15/11/2020).

- [38].Carr AJ, Higginson IJ. Are quality of life measures patient centred? BMJ 2001;322:1357-1360. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1357 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ware JE, Jr, Gandek B. Overview of the SF-36 Health Survey and the International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:903-912. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00081-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Jackson DL. Revisiting sample size and number of parameter estimates: some support for the N:q hypothesis. Struct Equ Modeling 2003;10:128-141. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_6 10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: how to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 2nd ed. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lim LL, Seubsman S-a, Sleigh A. Thai SF-36 Health Survey: tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, reliability and validity in healthy men and women. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008;6:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-6-52 10.1186/1477-7525-6-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Leung YY, Ho KW, Zhu TY, Tam LS, Kun EW-L, Li EK-M. Testing scaling assumptions, reliability and validity of Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 Health Survey in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology 2010;49:1495-501. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq112 10.1093/rheumatology/keq112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sharma B. A focus on reliability in developmental research through Cronbach’s alpha among medical, dental and paramedical professionals. Asian Pac J Health Sci 2016;3:271-278. https://doi.org/10.21276/apjhs.2016.3.4.43 10.21276/apjhs.2016.3.4.43 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994;6:284. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 10.1037/1040-3590.6.4.284 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Schreiber JB, Nora A, Stage FK, Barlow EA, King J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: a review. J Educ Res 2006;99:323-338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338 10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods 1996;1:130. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6:1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Shevlin M, Miles JN. Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Pers Individ Dif 1998;25:85-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00055-5 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00055-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1992;112:155. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Christensen LN, Ehlers L, Larsen FB, Jensen MB. Validation of the 12 item Short Form Health Survey in a sample from region Central Jutland. Soc Indic Res 2013;114:513-521. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-15 10.1186/1477-7525-9-15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Myers ND, Ahn S, Jin Y. Sample size and power estimates for a confirmatory factor analytic model in exercise and sport: a Monte Carlo approach. Res Q Exerc Sport 2011;82:412-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]