ABSTRACT

OX40 (CD134) is a co-stimulatory molecule mostly expressed on activated T lymphocytes. Previous reports have shown that OX40 can be an immuno-oncology target and a clinical biomarker for cancers of various organs. In this study, we collected formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples from 124 patients with small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) who had undergone surgery. We analyzed the expression profiles of OX40 and other relevant molecules, such as CD4, CD8, and Foxp3, in tumor stroma and cancer nest using immunohistochemistry and investigated their association with survival. High infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes (OX40high) in tumor stroma was positively associated with relapse-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) compared with low infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes (OX40low) (RFS, median, 26.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI), not reached (NR)–NR] vs 13.2 months [9.1–17.2], p = .024; OS, NR [95% CI, NR–NR] vs 29.8 months [21.3–38.2], p = .049). Multivariate analysis revealed that OX40high in tumor stroma was an independent indicator of prolonged RFS. Moreover, RFS of patients with OX40high/CD4high in tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of patients with OX40low/CD4low. The RFS of patients with tumor stroma with OX40high/CD8high was significantly longer than that of patients with tumor stroma with OX40low/CD8high, OX40high/CD8low, or OX40low/CD8low. These findings suggest that OX40+ lymphocytes in tumor stroma play a complementary role in regulating the relapse of early-stage SCLC. Reinforcing immunity by coordinating the recruitment of OX40+ lymphocytes with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma may constitute a potential immunotherapeutic strategy for patients with SCLC.

KEYWORDS: Small-cell lung cancer, OX40, CD4, CD8, survival

Introduction

Small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) accounts for approximately 13–15% of all lung cancers.1,2 SCLC has high mitotic rate and shows early metastasis; therefore, it requires early intervention, including chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Recently, the addition of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) to platinum-based chemotherapy significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) in extensive stage SCLC, and this practice has since become a standard first line treatment.3,4 However, three recent phase III trials3–5 conducted in different countries have revealed that only a subset of patients benefits from ICIs. Thus, thorough investigation of treatment strategies including other immunological targets is urgently required.

OX40, also known as CD134, is a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily. It resides on the surface of various immunological cells such as activated T lymphocytes and regulatory T cells (Tregs). OX40 engagement via the OX40 ligand (OX40L) mediates antitumor immunity via anti-apoptotic protein induction, effector T cell stimulation, and Treg suppression.6 However, conflicting clinical observations have been reported in this regard. Specifically, the infiltration of OX40+ T cells in tumors was related to better survival in patients with colon cancer7 and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC),8 but worse survival was observed in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.9 Investigators, including us, have attempted to enhance OX40 signaling using OX40L fusion proteins and anti-OX40 agonistic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) either individually or in combination with ICIs, other immunotherapy, or radiotherapy to establish a novel immunotherapeutic strategy in pre-clinical and clinical settings.6,10–12 However, the OX40 expression profile in SCLC remains relatively unknown. In addition, searching ClinicalTrials.gov using the terms “SCLC” and “OX40” revealed just one ongoing clinical trial and another completed clinical trial that included patients with advanced solid tumors including SCLC who were administered agonistic anti-OX40 monoclonal antibodies (NCT02554812 and NCT03241173, respectively as of August 1st, 2021). The findings of these trials are yet to be reported.

In the light of these observations, in this study, we aimed at identifying the association between OX40 protein expression within the SCLC tumor microenvironment and patient survival to investigate if OX40 expression could be a prognostic biomarker of SCLC, and to validate if it can be an immunological target in SCLC. Further, we sought to examine the association between the expression levels of OX40 in SCLC and those of other relevant immunological molecules, including CD4, CD8, and Foxp3, which is expressed predominantly in Tregs, to determine whether OX40 has a complementary or superior role in the precise evaluation of survival.

Methods

Patient information

We used previously described eligibility criteria.13 Briefly, in this study, we included patients with primary SCLC who had undergone complete surgical resection of the primary lung tumor between January 2003 and January 2013 at 17 participating institutions, which included the Fukushima Investigative Group for Healing Thoracic Malignancy (FIGHT) and the Hokkaido Lung Cancer Clinical Study Group Trial (HOT). Written informed consent was obtained only from patients who were still alive at the time of data accrual (from February 2013 to January 2014).

This retrospective observational study was registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry with the Identification Number UMIN000010117. This study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the respective participating institutions. All individual data were obtained from medical records and de-identified. Each tissue sample was anonymized by assigning a randomized code number. Tumor stages were determined or reclassified according to the seventh edition of the tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) staging system.14

Sample preparation

All the cases included in the present study met the following criteria: a complete surgical resection of primary tumors and confirmation of a pathological diagnosis of SCLC or combined SCLC according to the 2004 World Health Organization classification15 after a central re-review. The formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were cut into 4–5 μm sections, and each section was mounted on a glass slide for immunohistochemistry (IHC). The central pathological review and IHC were performed at the Department of Translational Pathology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine (Sapporo, Japan). The reviewers were blinded to the sample grouping and assessment. Generally, the number of SCLC patients who undergo surgery is limited. Thus, we did not set any limit on the sample size for this study. Instead, we attempted to collect as many samples with annotated clinical data from the respective institutions as possible. The total number of samples finalized for analysis was 124.

IHC

Rabbit polyclonal anti-human OX40 antibody (1:1000; ab119904, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), mouse anti-human CD4 mAb (1:100; 4B12, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK), mouse anti-human CD8 mAb, (1:150; C8/144B, M710301, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and mouse anti-human Foxp3 mAb (1:200; 236A/E7, ab20034, Abcam) were used as primary antibodies. For antigen retrieval, the slides were placed in a water bath for 30 min in 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, pH 9.0). Subsequently, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by treatment with 3% hydrogen peroxide in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min. The sections were then washed in water. After blocking nonspecific binding with the addition of 10% porcine serum in PBS for 10 min, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies in a humid chamber at 4 °C overnight. After washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with a labeled polymer (Histofine Simple stain MAX-PO, Nichirei Bioscience, Tokyo, Japan) for 30 min at 25 °C. The slides were washed with PBS and water. Then, 3, 3-diaminobenzidine was added and the sample was incubated for 5 min, and the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 1 min. We sought to detect OX40L during IHC; however, no reliable primary antibody was available. Two specimens stained for CD4 could not be evaluated due to insufficient quantity. All slides were digitally scanned at 100× or 400× using a scanner (NanoZoomer S210, Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Hamamatsu, Japan) to obtain high-resolution digital images. The images were visualized using a software program, NanoZoomer Digital Pathology (NDP. view2 U12388-01, Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.).

All slides were reviewed by two pathologists who were blinded to the clinical information. For enumerating OX40+ lymphocytes, CD8+ T cells, and Foxp3+ lymphocytes, whole fields per slide at 200× were evaluated to determine the number of stained cells. OX40 is expressed on neutrophils, as described in a previous report.16 However, in this study, we examined the expression level of OX40 only on lymphocytes. For evaluating CD4+ T cells, we performed a semi-quantitative analysis for the precise evaluation of the positive signal, since large deviations indicative of biological heterogeneity in SCLC were observed across staining fields within the same individual specimens. Whole fields per slide (200× magnification) were evaluated to semi-quantify the stained cells. The numbers of cells stained for CD4 were graded as follows; 0 (less than or equal to 1 cell per field in both cancer nest and tumor stroma), 1+ (more than 1 to 2 cells per field in cancer nest, and more than 2 to 5 cells per field in tumor stroma), 2+ (more than 2 to 5 cells per field in cancer nest, and more than 5 to 10 cells per field in tumor stroma), 3+ (more than 5 to 10 cells per field in cancer nest, and more than 10 to 15 cells per field in tumor stroma), and 4+ (more than 10 cells per field in cancer nest, and more than 15 cells per field in tumor stroma).

The pathologists repeated the evaluation five times in random fields spanning the tumor compartment and calculated the average number of cells positively stained for OX40, CD8, and Foxp3. They also semi-quantified the tissues positively stained for CD4. The cutoff values to define high expression levels of immunological markers in tumor stroma were as follows: OX40+ lymphocytes, ≥60 per field; CD8+ T cells, ≥50 per field; and Foxp3+ lymphocytes, ≥1.7 per field. Their respective values in the cancer nest were ≥25, ≥10, and ≥1 per field. Considering that CD4 expression was evaluated semi-quantitatively, the 2+, 3+, and 4+ values were regarded as high expression. We determined these cutoff values in accordance with the distribution of the expression levels stratified by each histogram (Figure S1).

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard model analyses were performed to examine the association between clinical variables, IHC scores, and survival. The association between factors considered significant in univariate analysis was confirmed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Rho) analysis; the entering of multiple variables was avoided with Rho ≥ 0.6 and similar significance levels. We included variables from the univariate analysis with p < .05 in the multivariate analysis. OS was calculated from the date of surgery to the date of death. Patients who had survived through the observation period were censored for the date at which the last status information was available. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in survival distributions were evaluated using the log-rank test. Association between OX40 expression in the tumor stroma and the clinical variables in special interest cases, including stage and administration of adjuvant chemotherapy, was analyzed by either Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Results with p < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

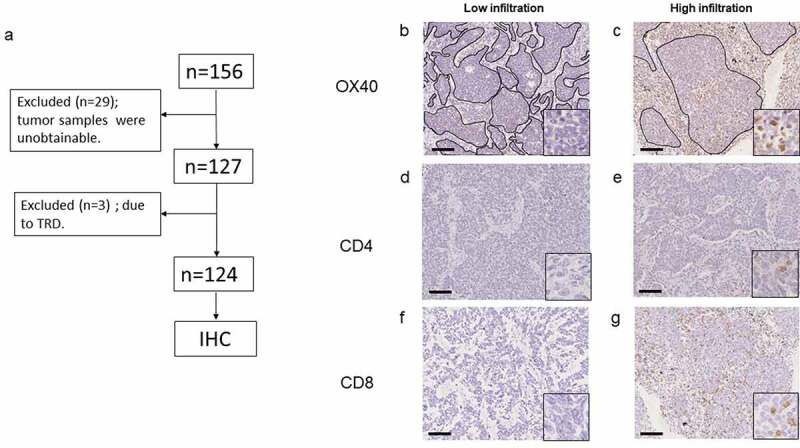

Between January 2003 and January 2013, 156 patients with SCLC who had undergone surgery were enrolled from 17 institutions. We collected formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor samples from 127 patients. However, three patients were excluded because they died due to post-surgery complications (Figure 1(a)). Of the three, two patients died of acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonitis at 14 and 33 days after surgery, respectively. The third patient died of hemorrhagic shock due to anastomotic trachea-pulmonary artery fistula three days after surgery. The baseline characteristics of the remaining 124 patients, who were either alive at the end of the study period or had died due to SCLC, are listed in (Table 1 and Table S1). The median age of participants was 70 years; 30 (24.2%) patients were female, and 10 (8.1%) were never-smokers. Eighty-seven (70.2%) patients had Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status 0. Twenty-one (16.9%) and 39 patients (31.5%) had a history or presence of interstitial pneumonitis and other types of cancer, respectively. The numbers of patients with SCLC and combined SCLC were 88 (71.0%) and 36 (29.0%), respectively. The clinical stages (TNM version 7) were IA (n = 78, 62.9%), IB (n = 13, 10.5%), IIA (n = 12, 9.7%), IIB (n = 7, 5.6%), IIIA (n = 12, 9.7%), and IIIB (n = 2, 1.6%). Most of the patients had undergone lobectomy (71.8%) along with regional hilar–mediastinal lymph node dissection (62.9%). Adjuvant chemotherapy was conducted in 76 (61.3%) patients, including 69 patients who received platinum-containing regimens (Table S2), eight who received chemoradiotherapy, and two who received neo-adjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy. Prophylactic cranial irradiation was performed in eight (6.5%) patients.

Figure 1.

(a) Flowchart depicting this study. TRD, treatment-related death; IHC, immunohistochemistry. (b, c) Representative images of IHC stained tumor sections showing either low or high infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes in both tumor stroma and cancer nest. (original magnification: 100×; inset: 400×). Areas surrounded by black lines show cancer nests. (d, e) Representative images of IHC stained sections showing either low or high CD4+ T cells and (f, g) CD8+ T cells in both tumor stroma and cancer nest (original magnification: 100×; inset: 400×). Scale bars represent 100 µm

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients included in this study

| Patients (n = 124) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. | % | |

| Age, median (range in years) | 70 (44–85) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 30 | 24.2 | |

| Male | 94 | 75.8 | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never-smoker | 10 | 8.1 | |

| Smoker (current or former) | 107 | 86.3 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 5.6 | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| 0 | 87 | 70.2 | |

| 1 | 30 | 24.2 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 5.6 | |

| Maximum tumor diameter, median (mm) | 20.5 (8–95) | ||

| Histology | |||

| SCLC | 88 | 71.0 | |

| Combined SCLC | 36 | 29.0 | |

| Clinical stage (TNM, version 7 · 0) | |||

| IA | 78 | 62.9 | |

| IB | 13 | 10.5 | |

| IIA | 12 | 9.7 | |

| IIB | 7 | 5.6 | |

| IIIA | 12 | 9.7 | |

| IIIB | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

| Yes | 76 | 61.3 | |

| No | 45 | 36.3 | |

| Unknown | 3 | 2.4 | |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis

OX40, CD4, and CD8 expression profiles by IHC

The expressions of OX40, CD4, and CD8 were observed on the membrane of lymphocytes, while the expression of Foxp3 was detected in the nucleus of lymphocytes, either in tumor stroma or the cancer nest of SCLC samples (Figure 1(b-g) and Figures S2(a,b)). The number of cells stained with the anti-OX40 antibody in the tumor stroma was 0–511.6 (median 26.8) per slide, and that in the cancer nest was 0–195.2 (median 13.4) (Figure S1(a,e)). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Rho) indicated a moderate correlation between the OX40+ lymphocytes in the tumor stroma and those in the cancer nest (Rho: 0.500, p < .001), and the CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma (Rho: 0.627, p < .001). Weak correlations were observed between the OX40+ lymphocytes in the tumor stroma and the CD8+ T cells in the cancer nest (Rho: 0.379, p < .001), the Foxp3+ lymphocytes in either the tumor stroma or the cancer nest (Rho: 0.195, p = .028, and Rho: 0.263, p = .003, respectively), and the CD4+ T cells in either the tumor stroma or cancer nest (Rho: 0.228, p = .012, and Rho: 0.288, p = .001, respectively) (Table S3).

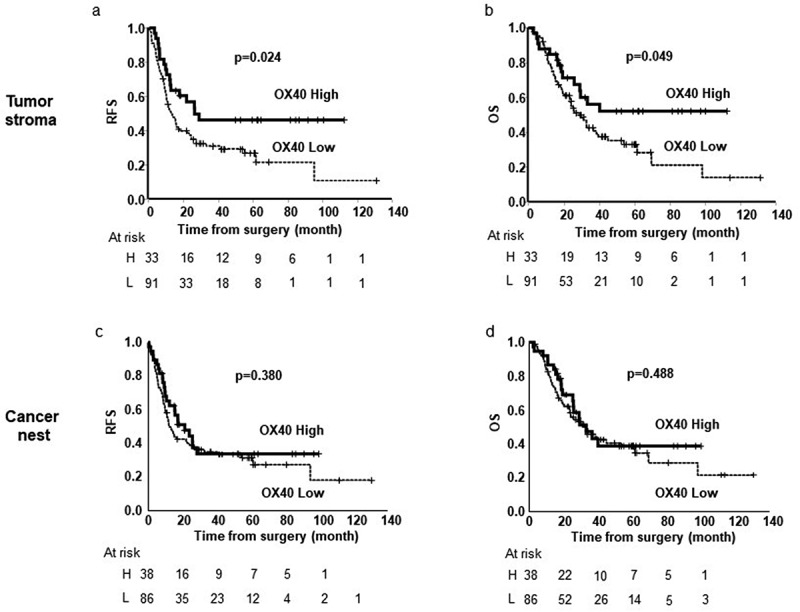

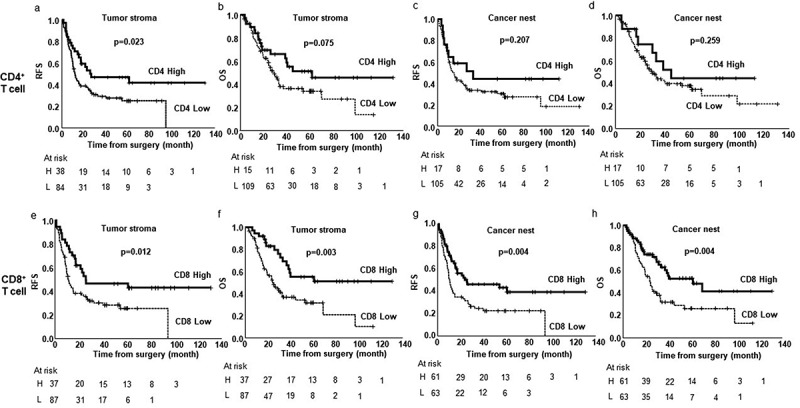

Association between expression of OX40 and other immunological molecules and survival

The median survival follow-up time was 27.2 months (range, 2.2–130.9). The Kaplan–Meier and log-rank tests demonstrated that high infiltration of the OX40+ lymphocytes (OX40high) in tumor stroma was positively associated with relapse-free survival (RFS) and OS, compared with the low expression of OX40 (OX40low) in the tumor stroma (p = .024, p = .049; Figure 2(a,b)); however, similar results were not observed in the cancer nest (Figure 2(c,d)). High infiltration of CD4+ T cells (CD4high) in the tumor stroma was significantly associated with RFS (p = .023; Figure 3(a)), but not with OS (Figure 3(b)) compared with low infiltration of CD4+ T cells (CD4low). The extent of CD4 T+ cell infiltration in the cancer nest did not associate with either RFS or OS (Figure 3(c,d)). High infiltration of CD8+ T cells (CD8high) in both the tumor stroma and the cancer nest was associated with RFS (p = .012, p = .004; Figure 3(e,g)) and OS (p = .003, p = .004; (Figure 3(f,h)), compared with low infiltration of CD8+ T cells (CD8low). The expression levels of Foxp3 in both the tumor stroma and the cancer nest did not associate with either RFS or OS (Figure S2(c-f)).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of relapse-free survival (RFS) (a) and overall survival (OS) (b) of the patients with tumors stratified by the infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes in tumor stroma. Kaplan–Meier estimates of RFS (c) and OS (d) of the patients with tumors stratified by the expression of OX40+ lymphocytes in cancer nest. Vertical bars indicate the censored cases at the data cutoff point

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of either relapse-free survival (RFS) or overall survival (OS) of the patients with tumors stratified by the infiltration of CD4+ T cells in tumor stroma (a, b), CD4+ T cells in cancer nest (c, d), CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma (e, f), and CD8+ T cells in cancer nest (g, h). Vertical bars indicate the censored cases at the data cutoff point

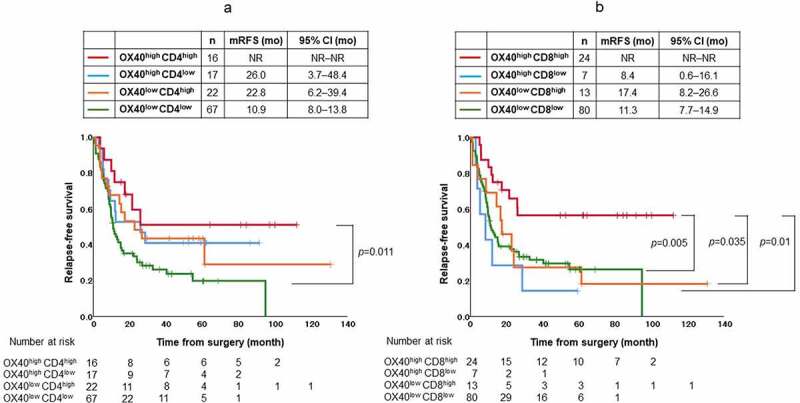

The RFS of patients with OX40high/CD4high in the tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of those with OX40low/CD4low (p = .011) (Figure 4(a)). The RFS of patients with OX40high/CD8high in the tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of patients with either OX40low/CD8high, OX40high/CD8low, or OX40low/CD8low in the tumor stroma (p = .035, 0.01, and 0.005, respectively) (Figure 4(b)).

Figure 4.

(a) Kaplan–Meier estimates of relapse-free survival (RFS) of the patients with stratified by OX40+ lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells in tumor stroma. RFS of patients with high infiltration of both OX40+ lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells in tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of patients with low infiltration of both OX40+ lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells in tumor stroma (p = .011). (b) Kaplan–Meier estimates of RFS of the patients with stratified by OX40+ lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma. RFS of patients with high infiltration of both OX40+ lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of patients with low infiltration of both OX40+ lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma (p = .005), that of patients with low infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes and high infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma (p = .035), and that of patients with high infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes and low infiltration of CD8+ T cells in tumor stroma (p = .01). Vertical bars indicate the censored cases at the data cutoff point. NR, not reported

The primary goal of this study was to examine the association between the expression of OX40 on lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment and clinical variables, including survival. Thus, we included both the expression parameters of OX40 in the tumor stroma and clinical variables such as serum level of lactate dehydrogenase within the normal range, clinical stage I and II SCLC, lobectomy, hilar–mediastinal lymph node dissection, and adjuvant chemotherapy in the multivariate analysis. All of these showed statistically significant association with RFS in the univariate analysis (Table S4). The multivariate analysis revealed that OX40 expression in tumor stroma was an independent factor for prolonged RFS (hazard ratio: 0.53, 95% CI: 0.30–0.93, p = .027) (Table 2). However, in the univariate and multivariate analyses, OX40 expression in the tumor stroma was not associated with OS (Table S5 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of the association between the explanatory variables and RFS

| Variables | HR | 95%CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum level of LDH < ULN | 1.00 | 0.61–1.64 | 0.990 |

| Lobectomy | 0.46 | 0.27–0.79 | 0.005 |

| Hilar-mediastinal lymph node dissection | 0.64 | 0.37–1.09 | 0.100 |

| c-stage I and II | 0.34 | 0.17–0.67 | 0.002 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.49 | 0.30–0.81 | 0.005 |

| High OX40 in tumor stroma | 0.53 | 0.30–0.93 | 0.027 |

RFS, relapse-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; ULN, upper limit of normal; c-stage, clinical stage; Cox proportional hazard model analysis was used to obtain the p values.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the association between the explanatory variables and OS

| Variables | HR | 95%CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without history or presence of other types of cancer | 0.54 | 0.31–0.95 | 0.034 |

| c-stage I and II | 0.25 | 0.13–0.50 | < 0.001 |

| Lobectomy | 0.60 | 0.33–1.10 | 0.099 |

| Hilar-mediastinal lymph node dissection | 0.63 | 0.34–1.16 | 0.137 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.61 | 0.36–1.02 | 0.061 |

| High OX40 in tumor stroma | 0.56 | 0.30–1.05 | 0.071 |

OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; c-stage, clinical stage; Cox proportional hazard model analysis was used to obtain the p values.

In this study, we selected patients who had undergone adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy and examined the association between OX40 expression and response to the therapy in terms of RFS and OS using a log-rank test. There was no significant association between OX40 expression in the tumor stroma and either RFS or OS (RFS, p = .507; OS, p = .733, Figure S3).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the association between OX40 expression on lymphocytes and survival in patients with SCLC. Previous studies have suggested that tumor compartments such as the tumor stroma and the cancer nest have differential patterns of cytokine or chemokine secretion in breast cancer.17 Further, in solid tumors, distinct phenotypes and quantitative differences in various immunological properties, including among effector immune cells and tumor-associated macrophages, are observed.18 Previous clinical reports have underscored the importance of these differences by showing that these differences are associated with survival in human cancers.19,20 Moreover, these differences hint at distinct therapeutic targets.18 In the vast majority of SCLC cases, the tumor stroma and cancer nest can be clearly distinguished from each other, as can be seen in (Figure 1(b,c)). Thus, we considered it plausible to assess immunological profiles, including OX40 expression, at these two tumor locations in this study.

The results showed that patients with OX40high in the tumor stroma but not in the cancer nest had better RFS and non-independently better OS than patients with OX40low. To address the possibility of an association between OX40 expression in the tumor stroma and either the stage or history of adjuvant chemotherapy, which may affect prolonged RFS in patients with OX40high, we performed either Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. However, no association was found (Table S6).

We observed CD8high in both the tumor stroma or the cancer nest, which was associated with prolonged RFS and OS (Figure 3(e-h)); this confirmed that CD8+ T cells were potentiated as effector T cells. Moreover, this finding was consistent with those of previous studies.21,22 OX40 is not expressed on naïve T cells but is strongly expressed on activated T cells, such as CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells, after antigen stimulation and subsequent T cell receptor signaling.23 Thus, the variable findings regarding the association between RFS and OX40 expression at different locations may be due to plausible partial expression of OX40 on antigen-encountered CD8+ T cells with effector function in the tumor stroma but not in the cancer nest. (Figure 4(b)) demonstrates that the RFS of patients with OX40high/CD8high in the tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of patients with OX40low/CD8high. A previous study demonstrated that some of the CD8+ T cells detected in the tumor may be non-antigen-specific T cells called bystander CD8+ T cells, which lack CD39 expression and contribute less to anti-tumor immunity.24 Our results suggest that OX40+ expression may play a complementary role, along with effector CD8+ T cells, in the accurate prediction of the RFS of patients with SCLC, as reported in patients with colorectal cancer.7

Another reason behind this diversity could be the role played by CD4+ T cells in the tumor stroma and the cancer nest in specific individuals whose tumors are infiltrated with OX40+ lymphocytes. It has been reported that CD4+ T cells augment the recruitment of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells into tumors, which facilitates tumor elimination.25 A previous study26 showed that the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules was not detected in SCLC cell lines or in tumor cells from tissue specimen, but was observed in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), although the expression level in TILs was lower than that in NSCLC TILs. Another study27 demonstrated that MHC class II-restricted tumor derived antigens are required to reject tumors, suggesting that activation of CD4+ T cells should occur in tumor microenvironment for tumor elimination. As shown in (Figure 3), the RFS of patients with CD4high in the tumor stroma was significantly longer than that of patients with CD4low. In addition, (Figure 4(a,b)) demonstrated that the longest RFS was observed in patients with coexistence of OX40+ lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells in the tumor stroma, and in those with the localization of both OX40+ lymphocytes and CD8+ T cells in the tumor stroma. These results indicate that antitumor immunity in SCLC may be induced by following steps: i) accumulation of antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that may express MHC class II molecules and neoantigens, ii) recruitment of OX40+ lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells or OX40+ CD4+ T cells to the tumor stroma, and iii) production of cytokines by APCs and T cells. These processes may eventually assist in the activation of CD8+ T cells and in their penetration into the cancer nest.

While OX40 functions as a suppressor of Tregs,6 it is constitutively expressed on Tregs, including on Foxp3+ T cells, particularly on those isolated from tumor sites.28–30 In our study, significant but weak correlation was found between the OX40+ and Foxp3+ lymphocytes in the cancer nest (Rho: 0.285, p = .001, data not shown). We cannot exclude the possibility that some of the OX40+ lymphocytes in the cancer nest in our SCLC cohort may have been Foxp3+ lymphocytes, or other regulatory T cells31 on which the expression of specific immune-checkpoint molecules such as T-cell immunoglobulin, mucin domain 3 (Tim-3),32 programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1),22 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4)33 may be upregulated. Alternatively, effector function of OX40+ lymphocytes in the cancer nest might be impaired by immune suppressive cytokines from cancer cells34 with the expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and poliovirus receptor (PVR).32 Further studies evaluating these differential expression profiles of OX40+ lymphocytes in tumor stroma and cancer nest are required. Various spatial relationship analyses using multiplex IHC and image cytometry35 may further investigate these differences.

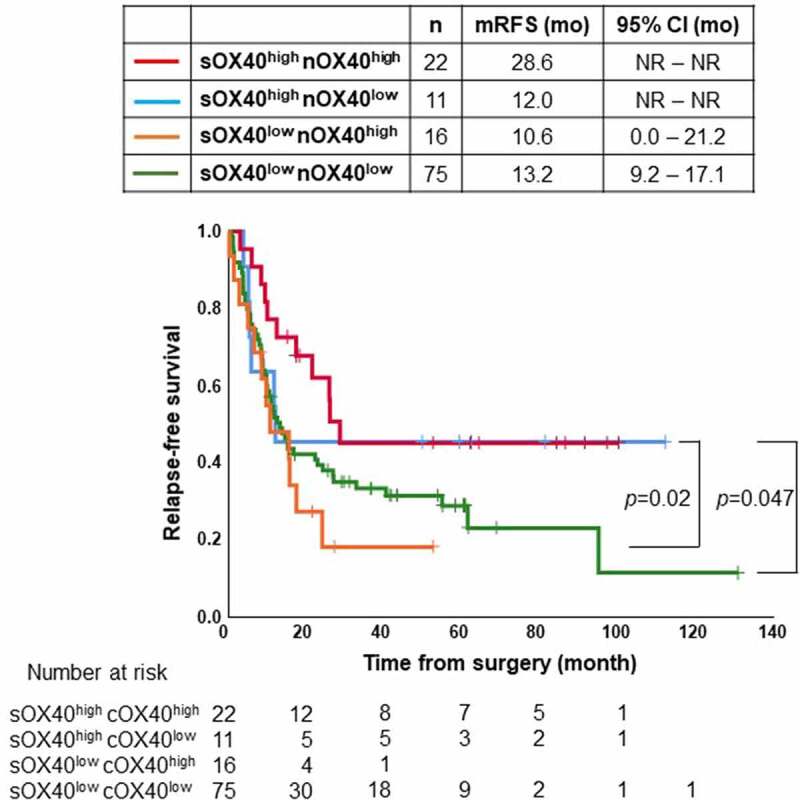

Emerging evidence from clinical trials has shown that neo-adjuvant immunotherapy for early-stage cancers is efficacious, which has been confirmed by pathological observations of TIL and less viable tumor cell accumulation in resected specimens of melanoma36 and NSCLC.37,38 This neo-adjuvant chemotherapy is based on the hypothesis that both the primary tumor and subclinical micrometastatic disease are eliminated through the generation of systemic anti-tumor immunity, leading to augmentation of the clinical curative rate and complete molecular remission in peripheral blood.39,40 The differences between the infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes into the tumor stroma and the cancer nest in our SCLC cohort, and the differences in its association with survival, may be due to the surgeries that the patients underwent. OX40+ lymphocytes in both the cancer nest and tumor stroma were removed by lobectomy (in 71.8% of the patients in our cohort); however, more effector T cells, present in residual lung parenchyma or circulating in peripheral blood, probably existed in patients with OX40high in the resected tumor stroma. This speculation is partly supported by the results presented in (Figure 5), in which more durable benefits are represented as high plateaus in the tails of the RFS curves of patients with OX40high in the tumor stroma, compared with those in patients with OX40low in the tumor stroma, irrespective of the infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes in the cancer nest. A previous study demonstrated that certain gene signatures of circulating T cells matched with those of clonally expanded tumor-infiltrating T cells with effector functions in melanoma patients.41 Other investigators found that the cytotoxicity of a subset of tumor-infiltrated CD8+ T cells closely correlates with that of peripheral CD8+ T cells in patients with NSCLC.42 Thus, investigating the relationship between the infiltrated OX40+ lymphocytes in the tumor stroma and the OX40+ lymphocytes, or other specific types of T cells, in peripheral blood is important to validate whether this can be used to predict survival or to monitor longitudinal anti-tumor immunity in patients with SCLC.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of relapse-free survival (RFS) of the patients with tumor specimen stratified by infiltration levels of OX40+ lymphocytes in tumor stroma (sOX40) and OX40+ lymphocytes in cancer nest (nOX40). The RFS of patients with high infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes in both tumor stroma and cancer nest was significantly longer than that of patients with low infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes in tumor stroma and high or low infiltration of OX40+ lymphocytes in cancer nest (p = .02 and 0.047, respectively). Vertical bars indicate the censored cases at the data cutoff point. NR, not reported

The antitumor effect of agonistic OX40 antibody monotherapy is modest in patients with advanced solid tumors.29 Thus, thorough exploration of elaborate strategies targeting OX40 is required. Our results support the notion that the development of therapies targeting OX40 should be accompanied with trafficking CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the tumor stroma for patients with immune-cold tumors, which includes the vast majority of SCLC.32,43 It can be safely assumed that the induction of chemotaxis in APCs and T cells passing tumor vasculature by the manipulation of cognate cytokines or chemokines might be the first step, followed by the administration of OX40 agonists with or without anti-CTLA-4 mAb, anti-PD-1/ PD-ligand 1 mAb, and other immune checkpoint inhibitors.

This study involved one of the largest cohorts of SCLC patients who had undergone complete resection. Biological heterogeneity for various protein markers and gene expressions is well documented in both cancerous and normal tissues. A massive effort to map the heterogeneity in human tissues, including lung tissue, has been undertaken, as documented in the Human Atlas studies using single-cell RNA sequencing.44 The use of surgical specimens, but not biopsy samples, can avoid this heterogeneity.45,46 Thus, we could overlook the distribution of OX40 and other molecules within differential tumor compartments, including the tumor stroma and cancer nest. In addition, the present study collected various clinical variables available in daily practice, which could exclude potential confounding factors associated with OX40 expression.

We performed a single-plex IHC assay of OX40 and other molecules. Further, we presumed correlation between OX40+ lymphocytes and CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and Foxp3+ lymphocytes based on Spearman’s correlation analysis results. Thus, we could not specify the exact lymphocytes that expressed OX40.

In our multivariate analysis, we eliminated CD8+ T cells to avoid multicollinearity and to more concisely address the primary objective of this study, which was to explore the potentiation of OX40 for survival. Further, in a previous report which addressed the association between OX40 expression and survival in patients with NSCLC, the investigators had omitted CD3, CD8, and various chemokines, and had included only OX40 expression and clinical variables in the subsequent multivariate analysis.8

However, the presence of CD8+ T cell in the tumor stroma and cancer nest was a strong indicator of RFS and OS as shown in (Figure 3(e–h). Thus, we cannot deny the possibility that CD8 was a more predominant indicator of RFS than OX40, and that OX40 might play a complementary role in prolonging RFS with CD8+ T cells in SCLC.

Our study was retrospective and non-global in nature and there was a limited number of deaths (n = 53, 49.5%). Various cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens were used as adjuvant therapies in a heterogeneous patient population, and this could introduce another bias. A large-scale prospective study using the IHC data of OX40 with a complete follow-up is required to investigate the prolonged RFS and OS of SCLC patients who had undergone surgery to confirm our results. Another limitation of our study is that the patients in our cohort did not undergo immunotherapy at post-operative recurrence; thus, we could not examine the relationship between OX40 expression in tumors and the effect of immunotherapy. It would be valuable to study the impact of OX40 expression on patient responses to immune checkpoint inhibitors. In addition, we analyzed patients with relatively early-stage SCLC, which may not reflect the tumor biology and host immune response seen in in patients with extensive-stage SCLC whom we usually treat in day-to-day clinical practice.

In conclusion, OX40 expression in the tumor stroma could be a biomarker of relapse in patients with early-stage SCLC. Clarification of the phenotypic difference of OX40+ lymphocytes in the tumor stroma and cancer nest, and the selection of a treatment modality that can modulate the tumor stroma by stimulation and the coordinated recruitment of OX40+ lymphocytes with CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are necessary for the establishment of novel treatment strategies for patients with SCLC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients and families who provided written consent and participated in this study. The authors also thank Dr. Yasuhiro Chikaishi (University of Occupational Environmental Health) for participating in this study and collecting data for use in this study.

Funding Statement

The analysis in this work was supported by research funding from the Department of Translational Pathology, Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine; the Center for Respiratory Diseases, JCHO Hokkaido Hospital; the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Fukushima Medical University; and the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Hokkaido Cancer Center. The study sponsors did not have any role in the study design, data collection, interpretation of data, writing of the report, and decision to submit this paper for publication. Assistance in English proofreading was paid for by the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Hokkaido Cancer Center.

Authors’ contributions

Hiroshi Yokouchi contributed to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the samples and assembly of the clinical data, analysis and interpretation of the data, and writing of the manuscript.

Hiroshi Nishihara contributed to the conception and design of the study, performed the analysis and interpretation of the data, provided scientific feedback, and revised the manuscript critically.

Toshiyuki Harada, Shigeo Yamazaki, Hajime Kikuchi, Hidetaka Uramoto, Masao Harada, Kenji Akie, Fumiko Sugaya, Yuka Fujita, Kei Takamura, Tetsuya Kojima, Mitsunori Higuchi, Osamu Honjo, Yoshinori Minami, and Naomi Watanabe contributed to sample collection and assembly of the clinical data

Toraji Amano contributed to the study design, statistical analysis, and data interpretation.

Takayuki Ohkuri contributed to the conception and design of the study and the interpretation of the data, provided scientific feedback, and revised the manuscript.

Satoshi Oizumi, Fumihiro Tanaka, Masaharu Nishimura, Hiroyuki Suzuki, Hirotoshi Dosaka-Akita, and Hiroshi Isobe provided scientific feedback and contributed to critical revision of the manuscript.

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript submitted to OncoImmunology.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

Dr. Hiroshi Yokouchi received grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Chugai Pharmaceutical, in addition to honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca and Chugai Pharmaceutical.

Dr. Satoshi Oizumi received grants from AstraZeneca and Chugai Pharmaceutical, in addition to honoraria for lectures from AstraZeneca, Chugai Pharmaceutical, and Nippon Kayaku.

Dr. Fumihiro Tanaka received grants from Chugai Pharmaceutical, in addition to payment for lectures from AstraZeneca and Chugai Pharmaceutical.

Dr. Masao Harada received grants from AstraZeneca and Chugai Pharmaceutical.

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website

References

- 1.Van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK.. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1741–11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalemkerian GP, Akerley W, Bogner P, Borghaei H, Chow LQ, Downey RJ, Gandhi L, Ganti AKP, Govindan R, Grecula JC, et al. Small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(1):78–98. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horn L, Mansfield AS, Szczęsna A, Havel L, Krzakowski M, Hochmair MJ, Huemer F, Losonczy G, Johnson ML, Nishio M, et al. First-line atezolizumab plus chemotherapy in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(23):2220–2229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paz-Ares L, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, Statsenko G, Hochmair MJ, Özgüroğlu M, Ji JH, et al. Durvalumab plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (Caspian): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10212):1929–1939. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudin CM, Awad MM, Navarro A, Gottfried M, Peters S, Csőszi T, Cheema PK, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Wollner M, Yang JCH, et al. Pembrolizumab or placebo plus etoposide and platinum as first-line therapy for extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: randomized, double-blind, phase III KEYNOTE-604 study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(21):2369–2379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva CAC, Facchinetti F, Routy B, Derosa L. New pathways in immune stimulation: targeting OX40. ESMO Open. 2020;5(1):e000573. doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2019-000573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weixler B, Cremonesi E, Sorge R, Muraro MG, Delko T, Nebiker CA, Däster S, Governa V, Amicarella F, Soysal SD, et al. OX40 expression enhances the prognostic significance of CD8 positive lymphocyte infiltration in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(35):37588–37599. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massarelli E, Lam VK, Parra ER, Rodriguez-Canales J, Behrens C, Diao L, Wang J, Blando J, Byers LA, Yanamandra N, et al. High OX-40 expression in the tumor immune infiltrate is a favorable prognostic factor of overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):351. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0827-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xie K, Xu L, Wu H, Liao H, Luo L, Liao M, Gong J, Deng Y, Yuan K, Wu H, et al. OX40 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with a distinct immune microenvironment, specific mutation signature, and poor prognosis. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(4):e1404214. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1404214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yokouchi H, Yamazaki K, Chamoto K, Kikuchi E, Shinagawa N, Oizumi S, Hommura F, Nishimura T, Nishimura M. Anti-OX40 monoclonal antibody therapy in combination with radiotherapy results in therapeutic antitumor immunity to murine lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(2):361–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linch SN, McNamara MJ, Redmond WL. OX40 agonists and combination immunotherapy: putting the pedal to the metal. Front Oncol. 2015;5:34. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aspeslagh S, Postel-Vinay S, Rusakiewicz S, Soria J-C, Zitvogel L, Marabelle A. Rationale for anti-OX40 cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;52:50–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yokouchi H, Ishida T, Yamazaki S, Kikuchi H, Oizumi S, Uramoto H, Tanaka F, Harada M, Akie K, Sugaya F, et al. Prognostic impact of clinical variables on surgically resected small-cell lung cancer: results of a retrospective multicenter analysis (FIGHT002A and HOT1301A). Lung Cancer. 2015;90(3):548–553. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, Postmus PE, Rusch V, Sobin L. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2(8):706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wd T, Brambilla E, HK M-H, Cc H, edited by. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. 3rd ed. Lyon: IARC Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willoughby J, Griffiths J, Tews I, Cragg MS. OX40: structure and function - what questions remain? Mol Immunol. 2017;83:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sgroi DC. Preinvasive breast cancer. Ann Rev Pathol. 2010;5(1):193–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valkenburg KC, de Groot AE, Pienta KJ. Targeting the tumour stroma to improve cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(6):366–381. doi: 10.1038/s41571-018-0007-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang W, Liu K, Guo Q, Cheng J, Shen L, Cao Y, Wu J, Shi J, Cao H, Liu B, et al. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells and prognosis in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(37):62312–62329. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang M, McKay D, Pollard JW, Lewis CE. Diverse functions of macrophages in different tumor microenvironments. Cancer Res. 2018;78(19):5492–5503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eerola AK, Soini Y, Pääkkö P. A high number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with a small tumor size, low tumor stage, and a favorable prognosis in operated small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1875–1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun C, Zhang L, Zhang W, Liu Y, Chen B, Zhao S, Li W, Wang L, Ye L, Jia K, et al. Expression of PD-1 and PD-L1 on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes predicts prognosis in patients with small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:6475–6483. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S252031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bansal-Pakala P, Halteman BS, Cheng MH, Croft M. Costimulation of CD8 T cell responses by OX40. J Immunol. 2004;172(8):4821–4825. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simoni Y, Becht E, Fehlings M, Loh CY, Koo S-L, Teng KWW, Yeong JPS, Nahar R, Zhang T, Kared H, et al. Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature. 2018;557(7706):575–579. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borst J, Ahrends T, Bąbała N, Melief CJM, Kastenmüller W. CD4+ T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(10):635–647. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y, Rozeboom L, Rivard CJ, Ellison K, Dziadziuszko R, Yu H, Zhou C, Hirsch FR. MHC class II expression in lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2017;112:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alspach E, Lussier DM, Miceli AP, Kizhvatov I, DuPage M, Luoma AM, Meng W, Lichti CF, Esaulova E, Vomund AN, et al. MHC-II neoantigens shape tumour immunity and response to immunotherapy. Nature. 2019;574(7780):696–701. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1671-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montler R, Bell RB, Thalhofer C, Leidner R, Feng Z, Fox BA, Cheng AC, Bui TG, Tucker C, Hoen H, et al. OX40, PD-1 and CTLA-4 are selectively expressed on tumor-infiltrating T cells in head and neck cancer. Clin Transl Immunol. 2016;5(4):e70. doi: 10.1038/cti.2016.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curti BD, Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Morris N, Walker E, Chisholm L, Floyd K, Walker J, Gonzalez I, Meeuwsen T, Fox BA, et al. OX40 is a potent immune- stimulating target in late-stage cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2013;73(24):7189–7198. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Zhang J, Dranoff G, Wilson NS, Brogdon JL. OX40 engagement depletes intratumoral Tregs via activating FcγRs, leading to antitumor efficacy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92(6):475–480. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt A, Oberle N, Krammer PH. Molecular mechanisms of treg-mediated T cell suppression. Front Immunol. 2012;3:51. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dora D, Rivard C, Yu H, Bunn P, Suda K, Ren S, Lueke Pickard S, Laszlo V, Harko T, Megyesfalvi Z, et al. Neuroendocrine subtypes of small cell lung cancer differ in terms of immune microenvironment and checkpoint molecule distribution. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(9):1947–1965. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.12741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Regzedmaa O, Li Y, Li Y, Zhang H, Wang J, Gong H, Yuan Y, Li W, Liu H, Chen J. Prevalence of DLL3, CTLA-4 and MSTN expression in patients with small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:10043–10055. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S216362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K, Arihiro K. Tumor-driven evolution of immunosuppressive networks during malignant progression. Cancer Res. 2006;66(11):5527–5536. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsujikawa T, Mitsuda J, Ogi H, Miyagawa‐Hayashino A, Konishi E, Itoh K, Hirano S. Prognostic significance of spatial immune profiles in human solid cancers. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(10):3426–3434. doi: 10.1111/cas.14591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amaria RN, Reddy SM, Tawbi HA, Davies MA, Ross MI, Glitza IC, Cormier JN, Lewis C, Hwu W-J, Hanna E, et al. Neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in high-risk resectable melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1649–1654. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forde PM, Chaft JE, Smith KN, Anagnostou V, Cottrell TR, Hellmann MD, Zahurak M, Yang SC, Jones DR, Broderick S, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-1 blockade in resectable lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(21):1976–1986. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cascone T, William WN Jr., Weissferdt A, Leung CH, Lin HY, Pataer A, Godoy MCB, Carter BW, Federico L, Reuben A, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab in operable non-small cell lung cancer: the phase 2 randomized NEOSTAR trial. Nat Med. 2021;27(3):504–514. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01224-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robert C. Is earlier better for melanoma checkpoint blockade? Nat Med. 2018;24(11):1645–1648. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uprety D, Mandrekar SJ, Wigle D, Roden AC, Adjei AA. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy for NSCLC: current concepts and future approaches. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(8):1281–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucca LE, Axisa PP, Lu B, Harnett B, Jessel S, Zhang L, Raddassi K, Zhang L, Olino K, Clune J, et al. Circulating clonally expanded T cells reflect functions of tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Exp Med. 2021;218(4):e20200921. doi: 10.1084/jem.20200921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwahori K, Shintani Y, Funaki S, Yamamoto Y, Matsumoto M, Yoshida T, Morimoto-Okazawa A, Kawashima A, Sato E, Gottschalk S, et al. Peripheral T cell cytotoxicity predicts T cell function in the tumor microenvironment. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2636. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39345-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Guan XY, Jiang P. Cytokine and chemokine signals of T-cell exclusion in tumors. Front Immunol. 2020;11:594609. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.594609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Travaglini KJ, Nabhan AN, Penland L, Sinha R, Gillich A, Sit RV, Chang S, Conley SD, Mori Y, Seita J, et al. A molecular cell atlas of the human lung from single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature. 2020;587(7835):619–625. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2922-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munari E, Zamboni G, Lunardi G, Marchionni L, Marconi M, Sommaggio M, Brunelli M, Martignoni G, Netto GJ, Hoque MO, et al. PD-L1 Expression heterogeneity in non-small cell lung cancer: defining criteria for harmonization between biopsy specimens and whole sections. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(8):1113–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sharma A, Merritt E, Hu X, Cruz A, Jiang C, Sarkodie H, Zhou Z, Malhotra J, Riedlinger GM, De S, et al. Non-genetic intra-tumor heterogeneity is a major predictor of phenotypic heterogeneity and ongoing evolutionary dynamics in lung tumors. Cell Rep. 2019;29(8):2164–2174.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.