Abstract

The present study aimed at exploring the relationship between parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour in the families of 99 children aged 8–11 years. Parenting stress was assessed by parents, using the Parenting Stress Index, and children's problematic behaviour was assessed by teachers, using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. A moderation regression analysis showed a conditioning effect of paternal parenting stress in the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour. In the presence of high levels of paternal parenting stress, the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour was significant and strong (p = .01). When paternal parenting stress levels were low, the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour was not significant (p = .49). The results underlined that paternal parenting stress may buffer the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour. Clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Parenting stress, Paternal stress, Father, Behaviour problems, School‐age children

Parenting stress has been defined as a psychological burden resulting from parents' perceived discrepancy between their needs related to parenting and their own parental resources (Deater‐Deckard & Panneton, 2017). It arises in response to the difficulties of being a parent and is directed towards the self and the child. Parenting stress may negatively affect children's outcomes, both directly and indirectly (Crnic & Ross, 2017). In particular, research suggests that high levels of parenting stress may negatively influence parents' perceptions of and responses to their children, affecting children's skills development (Costa et al., 2006).

Most research in this area has focused on the impact of maternal parenting stress on children, finding maternal parenting to be a major predictor of children's well‐being. In contrast, a meta‐analysis revealed that few studies have investigated the role of fathers in the relationship between parenting stress and children's outcomes (Pinquart, 2017). The greater attention paid to mothers in the literature may be explained by their primary caregiving responsibilities, relative to fathers. However, in recent years, the increase in dual earner families and greater egalitarianism in parental roles have made fathers more involved in children's lives. Recent studies have shown that stress affects paternal warmth and the quality of father–child interactions (Deater‐Deckard & Panneton, 2017). In fact, paternal parenting stress has been found to be associated with less involvement from fathers, with long‐term adverse effects for children, lasting into adulthood (Wilson & Durbin, 2010). Despite the continuous expansion of research on parenthood, little is known about the effect of the possible interaction between maternal and paternal parenting stress on children's problematic behaviour. This is because much of the literature presents comparative studies on the influence of maternal versus paternal parenting stress on children's development, analysing mothers and fathers in separate models (Crnic & Ross, 2017).

According to family systems theory (Cox & Paley, 2003), the mother, the father and the child constitute a family system, with each member exerting a reciprocal influence. The implication of this is that, when considered in isolation, parents' behaviours cannot be fully understood. To date, most research on parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour has focused on the association between paternal involvement and maternal distress. For example, Kim and Park (2017) found that the parenting participation of fathers moderated the effects of maternal parenting stress on children's depression and anxiety. These results are aligned with other findings underlining the protective role of fathers on children's psychosocial adjustment. Specifically, the involvement of fathers may moderate the mother–child relation, reducing the damaging effects of maternal parenting behaviour on children's well‐being in high‐risk situations, including those involving maternal depression, maternal distress during stressful conditions (Vakrat et al., 2018) and maternal rejection (Papadaki & Giovazolias, 2013).

Based on the aforementioned studies and the theoretical model suggested by Goodman and Gotlib (1999) analysing the interaction effects of maternal and paternal parenting stress on children, in the current research, we considered fathers as a moderating variable. According to Goodman and Gotlib (1999), the degree of depressive symptoms in fathers may moderate the relationship between depressive symptoms in mothers and children. In particular, the authors hypothesised that healthy fathers may buffer the effects of maternal depressive symptoms on children by: (a) serving as a healthy role model; (b) providing necessary care; or (c) supporting depressed mothers in their caregiving tasks.

To our knowledge, the present study was the first to explore the moderating effect of paternal parenting stress in the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour (as reported by teachers).

Aim and hypotheses

Starting from the above considerations, in accordance with family system theory (Cox & Paley, 2003) we aimed at investigating whether fathers might moderate the mother–child relation, even in situations of parenting stress. In doing so, we sought to explore the relationship between parenting stress and children's difficulties in a triadic perspective, considering both maternal and paternal parenting stress through a multi‐informant approach integrating the perspectives of both parents and teachers. We expected paternal parenting stress to moderate the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour, after controlling for children's age and gender. Specifically, we expected that low levels of paternal parenting stress would buffer the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour, in line with the findings of Kim and Park (2017).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedure

An a priori power analysis was conducted to determine the necessary sample size, with alpha fixed to .05 and power to .80. A small effect size was hypothesised (r = .20). The power analysis resulted in a required sample size of 194 individuals. The present study involved 99 mothers, 99 fathers and eight teachers of 99 children aged 8–11 years (M age = 9.45; SD age = 0.6; 46 girls, 46.5%). Questionnaires were administered to mothers (M age = 40.90; SD age = 4.88; age range: 28–55 years), fathers (M age = 44.30; SD age = 5.25; age range: 28–57 years) and each child's main teacher (the teacher who spent the most hours with the child). Parents had a medium‐high level of education: 46% of the mothers and 29% of the fathers had a university degree and 36.2% of the mothers and 47.3% of the fathers had a high school qualification. Parents belonged to the Italian middle socio‐economic status.

Parents independently completed measures of parenting stress, while teachers evaluated children's problematic behaviours. All participants were recruited from public schools based in central Italy, and written consent from all participants was collected prior to the data collection. The study procedure was fully compliant with APA standards, the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethics Code of the Italian Board of Psychology—the regulatory authority that determines the national research guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measures

Parenting stress

The short form of the Parenting Stress Index (Abidin, 1995), comprised of 36 items, was used to assess parents' stress levels. For this measure, parents rate each item on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Items are designed to determine parents' perceived level of anxiety in interaction with their children (sample item: “My child rarely does things for me that make me feel very good”) and parental stress related to their children's temperament and behaviour (sample item: “My child makes more demands on me than most children”). In the present study, we used the mother's total score of parenting stress and father's total score of parenting stress, which showed good reliability (Cronbach's alphas of .83 and .89, respectively). Both scores were calculated by subtracting mothers' and fathers' scores (respectively) on the Defence Response subscale, which evaluates the tendency to minimise problems related to stress in the parent–child relationship, from the total score.

Children's problematic behaviour

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire—teacher version (Goodman, 1997), which evaluates teachers' perceptions of students' behaviours, was used to assess children's mental health (sample items: “Many worries, often he/she seems worried”; “Often he/she has temper tantrums or hot tempers”). Each of the 25 items is rated on a 3‐point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 3 (completely true). In the present study, the total score of child problematic behaviours (calculated by adding the Emotional Symptoms, Conduct Problems, Hyperactivity/Inattention and Peer Relationship Problems subscale scores), produced a Cronbach's alpha of .86.

Socio‐demographic data

Socio‐demographic information (e.g., age and gender) for children and parents was collected.

Data analysis

Correlations among variables were determined. Subsequently, a moderation regression analysis was run to test whether paternal parenting stress moderated the relation between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour. All variables were standardised in advance (in the form of z‐scores) to determine a complete standardised solution. The standardised scores of maternal and paternal parenting stress were multiplied to form the interaction term. The moderation effect was tested using hierarchical regression analysis. First, children's gender and age were included as covariates. Second, the criterion was regressed on maternal and paternal parenting stress. Finally, the interaction term was included in the regression equation.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports the intercorrelations among variables and descriptives.

TABLE 1.

Intercorrelations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender (0 = female; 1 = male) | 1 | |||||

| 2. Maternal parenting stress | −.02 | 1 | 52.61 | 11.13 | ||

| 3. Paternal parenting stress | −.07 | .42** | 1 | 53.69 | 12.74 | |

| 4. Children's problematic behaviour | .34** | .26* | .31** | 1 | 5.44 | 5.30 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Regarding the moderation analysis, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted following the previously described procedure. In the first step, age and gender were entered as covariates, accounting for 11.6% of the variance, R = .34, p = .003. Only gender emerged as a significant predictor, with boys showing more problematic behaviour than girls, as reported by teachers. In the second step, maternal and paternal parenting stress were added to the equation and found to account for 24.4% of the variance, R = .49, contributing a significant increment of 12.8% to the explained variance, ΔF(2, 94) = 7.97, p = .001. Only paternal parenting stress emerged as a significant predictor of children's problematic behaviour. Finally, the interaction term between maternal and paternal parenting stress was added to the model and found to contribute a further significant 3.7% to the explained variance, ΔF(1, 93) = 4.81, p = .031. The final model explained 28.1% of the variance, R = .53, p = .031. Table 2 reports the full statistics. The interaction term between maternal and paternal parenting stress was significant, suggesting a conditioning effect of paternal parenting stress.

TABLE 2.

Moderation analysis (Step 3)

| Children's problematic behaviour | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE |

| Gender (0 = female; 1 = male) | .70*** | .18 |

| Age | −.03 | .09 |

| Maternal parenting stress | .11 | .10 |

| Paternal parenting stress | .27* | .09 |

| Maternal parenting stress × paternal parenting stress | .21* | .09 |

| Total R 2 | .28* | |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

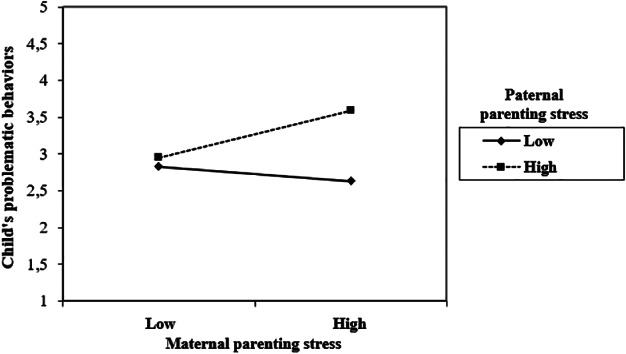

To interpret the direction of the interaction, a simple slope analysis was conducted by plotting the predicted values of children's problematic behaviour as a function of maternal parenting stress and two levels of paternal parenting stress (see Figure 1): low (i.e., 1 SD below the mean) and high (i.e., 1 SD above the mean). When paternal parenting stress levels were high, there was a significant positive relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour, B = .33, SE = .13, t = 2.49, p = .01. In contrast, when paternal parenting stress levels were low, the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour was not significant, B = −.11, SE = .16, t = − .69, p = 0.49. Therefore, low paternal parenting stress emerged as a protective factor in the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour.

Figure 1.

Slope analysis.

DISCUSSION

Parenting stress may represent an important environmental risk factor with several adverse outcomes, including less effective parenting (Crnic & Ross, 2017) and increased child problematic behaviours (Neece et al., 2012). However, few studies have considered parenting stress levels in both parents to understand how they might interact (Pinquart, 2017). In line with Pinquart's (2017) theory that the effects of one parent's psychological problems on children might be compensated for by the behaviour of the other parent, we aimed at exploring the relationship between maternal and paternal parenting stress and children's difficulties in a triadic perspective, using a multi‐informant approach integrating the perspectives of both parents and teachers. The results showed that teachers reported boys to show more problematic behaviours than girls, in line with prior findings that male children are more likely to present externalising behaviours and problematic conduct (Boeldt et al., 2012). The present results did not find any age difference in children's behavioural difficulties, consistent with the results of a recent meta‐analysis (De Los Reyes et al., 2015) showing that gender—but not age—affects raters' assessments of behaviour problems in younger and older children.

Also consistent with prior research (Lee et al., 2018), the present study found a correlation between parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour. Specifically, the hierarchical regression analysis demonstrated that paternal parenting stress—but not maternal parenting stress—was significantly related to children's behavioural difficulties. This result is inconsistent with prior studies finding that the mother, compared to the father, represents the strongest predictor of children's behavioural manifestations (Pinquart, 2017). A possible interpretation of this result may refer to the age of the children in the present sample. Younger children (i.e., preschool‐age) tend to spend more time with the mother than the father; thus, the mother is often the main reference figure at this age. However, in the case of older children (i.e., school‐age), fathers are often more engaged in caregiving and play, because they may be more strongly identified with their paternal role. Thus, it is possible that school‐age children may elicit their father's parental identity, influencing the quality of the father–child interaction. Nevertheless, the present findings are in line with prior studies showing that, in the case of older children, paternal parenting stress (but not maternal parenting stress) is significantly related to children's development (Harewood et al., 2017). However, among the studies that have explored the associations between paternal parenting stress and child behaviours, only few have also included maternal parenting stress.

The innovative finding of the present study is that paternal parenting stress appeared to moderate the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour, suggesting a possible buffering effect of low levels of paternal parenting stress. When paternal parenting stress levels were high, there was a significant positive and strong association between maternal parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour. Overall, these findings suggest that low paternal parenting stress may play a protective role for children's adjustment in the presence of high levels of maternal parenting stress. To our knowledge, no prior research has explored the moderating effect of paternal parenting stress; thus, a comparison of the present results with previous studies is difficult. Nevertheless, the results accord with the existing literature suggesting a strong relationship between maternal and paternal psychopathology, emphasising fathers' role as a moderator in the mother–child relationship. For example, Gere et al. (2013) found that the strength of the relationship between depressive symptoms in mothers and children depended on the level of paternal symptoms. In addition, the present findings align with those of a recent study highlighting that fathers' involvement in childcare represents a protective factor in the relationship between maternal parenting stress and children's anxiety and depression (Kim & Park, 2017).

The current study comprises a meaningful contribution to the body of knowledge on the possible role of low paternal parenting stress on family well‐being. Paternal parenting stress is associated with children's well‐being both directly and indirectly, providing an important moderating and buffering effect on maternal parenting stress. The present findings did not enable a conclusion to be drawn with respect to the processes underlying this association. However, following Gere et al. (2013), several explanations may be proposed: (a) the father may provide a positive role model alternative to the maternal one; (b) he may supply necessary childcare; or (c) he may provide a support function for the distressed mother. As the existing data do not point conclusively to an explanation, future research should investigate the mechanisms through which paternal mental health might influence the mother–child relationship, also considering other variables that might interact with paternal parenting stress, in order to develop and implement more focused interventions.

The relationship between child adjustment and parental stress may differ on the basis of child, parent and contextual characteristics. This may be considered a limitation of our study, and thus future research should explore the associations between parenting stress and children's problematic behaviour, controlling for these factors. Three other limitations of the present research are important to note. First, the small sample size may have reduced the generalisability of the findings. Second, the cross‐sectional nature of the study prevented causal conclusions to be drawn with respect to the relationships between variables. Finally, the assessment of parenting stress was based exclusively on self‐report questionnaires, which may have been affected by a social desirability bias. However, we were interested in measuring each parent's perception of his/her levels of parenting stress, and the best way to measure this variable was through self‐report, consistent with the methodology used in previous studies (e.g., Morelli et al., 2020).

Despite these limitations, the current research contributes to our knowledge of the relation between parenting distress (as reported by parents) and children's problematic behaviour (as assessed by teachers, who represent important informants of children's well‐being at school—a very significant context in child development). In particular, the multi‐informant approach represented a key strength of the study. Moreover, the findings may have relevant clinical implications. Clinicians and educators should adopt a systemic approach when managing children's problematic behaviour, addressing the parenting stress of both parents. If the entire family—and specifically fathers—are not involved in the intervention, the level of stress within the family will likely remain high, potentially resulting in negative outcomes for children. The present findings suggest that reducing paternal parenting stress might result in increasing fathers' support for mothers. In a family‐centred approach (reflecting the father–mother–child triadic interaction), healthcare professionals should consider the influence of both mothers and fathers and address both parents' stress management skills. Additionally, mindfulness interventions for parents could be considered, with the aim of decreasing parenting stress; this would likely result in positive outcomes for children (Burgdorf et al., 2019).

Carmen Trumello, Alessandra Babore: conception and design; collection; drafting the article. Marika Cofini: drafting the article. Mara Morelli and Antonio Chirumbolo: analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the article. Roberto Baiocco: revising the article. All authors gave the final approval of the version to be published.

Contributor Information

Carmen Trumello, Email: c.trumello@unich.it.

Mara Morelli, Email: mara.morelli@uniroma1.it.

REFERENCES

- Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting stress index: Professional manual (3rd ed.). Odessa, Fla: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Boeldt, D. L., Rhee, S. H., DiLalla, L. F., Mullineaux, P. Y., SchulzHeik, R. J., Corley, R. P., & Hewitt, J. K. (2012). The association between positive parenting and externalizing behavior. Infant and Child Development, 21, 85–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgdorf, V. L., Szabo, M., & Abbott, M. (2019). The effect of mindful interventions for parents on parenting stress and youth psychological outcomes: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, N., Weems, C., Pellerin, K., & Dalton, R. (2006). Parenting stress and childhood psychopathology: An examination of specificity to internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 28, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic, K., & Ross, E. (2017). Parenting stress and parental efficacy. In Deater‐Deckard K. & Panneton R. (Eds.), Parental stress and early child development: Adaptive and maladaptive outcomes (pp. 263–284). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes, A., Augenstein, T. M., Wang, M., Thomas, S. A., Drabick, D. A., Burgers, D. E., & Rabinowitz, J. (2015). The validity of the multi‐informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater‐Deckard, K., & Panneton, R. (2017). Unearthing the developmental and intergenerational dynamics of stress in parent and child functioning. In Deater‐Deckard K. & Panneton R. (Eds.), Parental stress and early child development: Adaptive and maladaptive outcomes (pp. 1–11). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gere, M. K., Hagen, K. A., Villabø, M. A., Arnberg, K., Neumer, S. P., & Torgersen, S. (2013). Fathers' mental health as a protective factor in the relationship between maternal and child depressive symptoms. Depression and Anxiety, 30(1), 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review, 106(3), 458–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harewood, T., Vallotton, C. D., & Brophy‐Herb, H. (2017). More than just the breadwinner: The effects of fathers' parenting stress on children's language and cognitive development. Infant and Child Development, 26(2), e1984. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E. D., & Park, C. S. (2017). The effects of mother's parenting stress on children's problematic behavior in the times of convergence: The moderating effects of father's parenting participation. Journal of Convergence Information Technology, 7(6), 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S. J., Pace, G. T., Lee, J. Y., & Knauer, H. (2018). The association of fathers' parental warmth and parenting stress to child behavior problems. Children and Youth Services Review, 91, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morelli, M., Cattelino, E., Baiocco, R., Trumello, C., Babore, A., Candelori, C., & Chirumbolo, A. (2020). Parents and children during the COVID‐19 lockdown: The influence of parenting distress and parenting self‐efficacy on children's emotional well‐being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(2020), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neece, C. L., Green, S. A., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117, 48–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki, E., & Giovazolias, T. (2013). The protective role of father acceptance in the relationship between maternal rejection and bullying: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(2), 330–340. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart, M. (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta‐analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 873–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vakrat, A., Apter‐Levy, Y., & Feldman, R. (2018). Sensitive fathering buffers the effects of chronic maternal depression on child psychopathology. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49, 779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S., & Durbin, C. E. (2010). Effects of paternal depression on fathers' parenting behaviors: A meta‐analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]