ABSTRACT

SARS-CoV-2 has been the causative pathogen of the pandemic of COVID-19, resulting in catastrophic health issues globally. It is important to develop human-like animal models for investigating the mechanisms that SARS-CoV-2 uses to infect humans and cause COVID-19. Several studies demonstrated that the non-human primate (NHP) is permissive for SARS-CoV-2 infection to cause typical clinical symptoms including fever, cough, breathing difficulty, and other diagnostic abnormalities such as immunopathogenesis and hyperplastic lesions in the lung. These NHP models have been used for investigating the potential infection route and host immune response to SARS-CoV-2, as well as testing vaccines and drugs. This review aims to summarize the benefits and caveats of NHP models currently available for SARS-CoV-2, and to discuss key topics including model optimization, extended application, and clinical translation.

KEYWORDS: SARS-CoV-2, non-human primates, severe acute respiratory syndrome, immunopathogenesis, vaccine and drug discovery

Introduction

Following the past two pandemics of beta-coronavirus infection, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 and middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012, a third pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has been affecting more than 200 countries with more than 200 million cases and over 4 million deaths. Most SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals exhibit mild to moderate symptoms, but approximately 20% of cases progress to severe pneumonia with respiratory distress, septic shock and/or multiple organ failures [1,2]. Currently approved clinical treatments cannot fully suppress viral replication and inflammation to rescue organ failure [3]. Despite having high genomic homology with SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 is much more contagious with an R0 of 5.1∼5.7 [4] than SARS-CoV with an R0 of 3.1 [5]. Therefore, it is imminent to obtain drugs against SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, many fundamental questions of SARS-CoV-2 biology and pathology remain unanswered. For example, how does SARS-CoV-2 infection cause complicated immunopathogenesis and hyperplastic lesions in the respiratory system? What are the potential routes for SARS-CoV-2 infection and what does determine tissue tropism among digestive, cardiovascular, urinary, reproductive, and central nervous systems? Moreover, the imbalanced and complicated host immune responses might drive different outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection [6], which may impose a challenge for the development of vaccine and immunotherapy. All the above-mentioned biological aspects need an appropriate animal model to investigate.

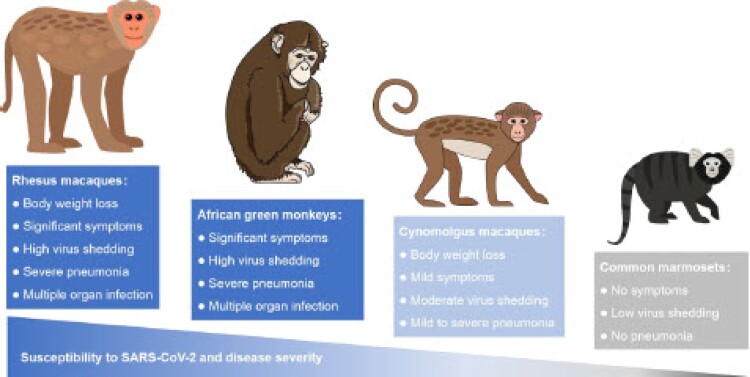

An appropriate animal model is essential for pre-clinical evaluation of the safety and effect of drugs or vaccines [7]. The evolutional, anatomical, physiological, and immunological similarities of NHP to humans make the NHP an ideal model to study the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans. Recently, four old- and new-world monkeys including rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus), and African green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus) have been demonstrated permissive for infection of SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 1). Typical clinical symptoms, virus shedding, tissue lesions, and host immune responses that are similar to human patients were observed in these NHP models. Although the disease severity varies among species and individuals, the NHP models are important for both the fundamental research, vaccine, and drug discovery of SARS-CoV-2. Here, we will discuss the critical findings and implications that might guide the fundamental studies, clinical management, urgent treatment, and future public health strategy for SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1.

Summary of SARS-CoV-2 infection in four NHP models. SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and disease severity of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), cynomolgus macaques (Macaca fascicularis), common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus), and African green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus).

Infection route and tissue tropism of SARS-CoV-2 in NHP

The receptor-mediated entry is the first step of a viral infection in the host cell [8]. Human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (hACE2) has been demonstrated to be the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 [9]. It was revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing that hACE2 is highly expressed not only in respiratory tract and lung [10], but also in other tissues and organs such as testis, liver, kidney, pancreas, small intestine, and bladder [11], implying that many organs are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, cholangiocytes [12], T-lymphocytes [13], small intestine enterocytes [14], and nasal epithelial cells [15] were reported to be permissive for direct SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, many of these claims were made based on the experiments using clinical samples, or cellular and organoid models and need to be confirmed in the animal models. Because hACE2 has many important physiological functions, it is not appropriate to choose hACE2 as a candidate molecule for the development of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine or therapeutics.

SARS-CoV-2 successfully infects the NHP through the ocular conjunctival, intratracheal, intranasal, and olfactory routes [16–19]. SARS-CoV-2 infection causes relatively severe symptoms in the rhesus macaque and the African green monkey among the four NHP models. In the rhesus macaque model, combined inoculation of SARS-CoV-2 intranasally, intratracheally, and orally results in more severe diseases than those with a single inoculation route [17]. Approximately 10% body weight loss was detected from 5 to 10 days post-infection (dpi) [17,20]. Generally, the rhesus macaque and the African green monkey are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection as compared to the cynomolgus macaque and the common marmoset (Figure 1). Although varied degrees of symptoms were observed and different viral loads were detected among different ages and genders, larger group size is needed to draw a certain conclusion. In addition to the different strains of SARS-CoV-2, the infection doses or routes of viruses and ages of the NHP might also lead to the variations of viral shedding, tissue viral load, and symptoms (Table 1). Similar to those in humans, symptoms including fever, cough, irregular respiration, and abnormal chest radiography were observed in the NHPs with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Virus shedding was detectable in nose, throat, and anal swabs, bronchi-alveolar lavages [21], blood [17], as well as hand and drinking nipple swabs [22]. Viral RNA was detected in the nose, pharynx, respiratory tract, lung, gut (duodenum, jejunum, ileum, caecum, and colon), and lymphatic system [18,19]. Furthermore, viral antigens were positive in nasal turbinate, lung, stomach, gut, and mediastinal lymph node. However, no SARS-CoV-2 RNA or antigen is identified in bone marrow, the reproductive tract, and the central nervous system up to date [21]. Taken together, this information suggested a productive SARS-CoV-2 infection in NHPs. Future studies need to demonstrate whether asymptomatic infection, viral rebound, close-contact, and fecal-oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 are possible using the NHP models.

Table 1.

Detailed information of representative NHP models for SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis.

| Research Groups and NHP species | Deng et al. | Deng et al. | Shan et al. | Munster et al. | Rockx et al. | Lu et al. | Woolsey et al. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhesus macaques | Cynomolgus macaques | Rhesus macaques | Cynomolgus macaques | Common marmosets | African green monkeys | ||||

| Age | 3∼5 years | 3∼5 years | 6∼12 years | Adult | Young (4∼5); Old (15∼20) | Young; Adult; Old | Adult | Adult | Adult |

| Amount | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 12 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Gender | Male | – | Male (3); Female (3) | Male (4); Female (4) | – | Male (6); Female (6) | Male (3); Female (3) | Male (3); Female (3) | Male (2); Female (4) |

| Viral strain | SARS-CoV-2/WH-09/human/2020/CHN (Wuhan, China) | IVCAS 6.7512 (Wuhan, China) | nCoV-WA1-2020 (USA) | Isolation from a German traveller returning from China | Local isolation (Guangdong, China) | Local isolation (Guangdong, China) | Local isolation (Guangdong, China) | Isolation from an Italy traveller returning from China | |

| Infection dose | 1 × 10E6 TCID50 | 7 × 10E6 TCID50 | 2.5 × 10E6 TCID50 | – | 4.75 × 10E6 PFU for adult and old; Half dosage for young | 4.75 × 10E6 PFU | 1 × 10E6 PFU | 4.6 × 10E5 PFU | |

| Infection route | Ocular conjunctival (2) or intratracheal (1) | Intratracheal | Intratracheal | Combination of intranasal (0.5 mL per nostril), intratracheal (4 mL), oral (1 mL) and ocular (0.25 mL per eye) | Combined intratracheal and intranasal | Combination of intranasal (0.5 mL), intratracheal (4 mL) and oral (0.25 mL) for adult and old | Combination of intranasal (0.5 mL), intratracheal (4 mL) and oral (0.25 mL) | Intranasal | Combination of intratracheal and intranasal routes |

| Positive swabs and biological samples | Nose, throat and anal (1∼7 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼14 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼14 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼20 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼8 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼14 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼14 dpi) | Nose, throat and anal (1∼12 dpi) | Nose (0∼12 dpi; 35∼40 dpi), oral (0∼7 dpi;), rectal (0∼15 dpi), bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (0∼7 dpi) |

| Peak tissue viral load | > 1 × 10E7 viral RNA copies in upper left lung at 7 dpi (intratracheal) | > 1 × 10E8 viral RNA copies in nose turbinate at 7 dpi | > 1 × 10E7 viral RNA copies in lower right lung at 3 dpi | > 1 × 10E8 viral RNA copies in right and left lung at 3 dpi | 1 × 10E4 TCID50eq in lung at 4 dpi | > 1 × 10E7 viral RNA copies in rectum at 7 dpi | > 1 × 10E3 viral RNA copies in spleen at 13 dpi | Undetectable (13 dpi) | > 1 × 10E7 viral RNA copies in lung at 5 dpi |

| Clinical illness | Increased body temperature (1/3) | 200∼400 g weight loss from 5∼15 dpi; reduced appetite, increased respiration rate, and hunched posture were transient after the initial challenge; Chest X-ray at 7 dpi showed that the upper lobe of the right lung had varying degrees of the localized infiltration and interstitial markings | 7∼8% weight loss at 14 dpi in two animals; Chest X-ray at 7 dpi showed signs of interstitial infiltrates and pneumonia; A variable degree of consolidation, oedema, haemorrhage, and congestion in bright red lesions throughout the lower respiratory tract and right lung at 6 dpi | 5∼10% weight loss from 5∼15 dpi in two animals; Reduced appetite, hunched posture, pale appearance, dehydration and irregular respiration patterns; Chest X-ray showed pulmonary infiltrates in one animal in 1∼12 dpi; Multifocal and random hilar consolidation and hypaeremia at 3 and 21 dpi | Two animals had foci of pulmonary consolidation in lung at 4 dpi; a serous nasal discharge in one aged animal at 14 dpi | Increased body temperature (12/12); Chest X-ray abnormality; > 10% weight loss at 10 dpi (8/12); severe pneumonia; inflammation in liver and heart | Increased body temperature (2/6); Chest X-ray abnormality; one animal showed 10% weight loss at 10 dpi; mild to severe pneumonia; inflammation in liver and heart | No symptoms | Fever, decreased appetite, and nasal exudate from 0 to 7 dpi; intermittent symptoms were observed from 8 to 57 dpi |

Immunopathology and hyperplastic lesions in the target organs of SARS-CoV-2-infected NHPs

Diverse degrees of trachea and lung lesions were observed in SARS-CoV-2-infected NHPs. The lesions were multifocal, from mild-to-moderate, interstitial pneumonia that frequently centred on terminal bronchioles [22,23]. The pneumonia was characterized by diffusive haemorrhage, inflammatory infiltration, consolidation, and hyperaemia. The normal alveolar structure was impaired with thickening of alveolar septate. The alveoli were filled with cell debris, inflammatory cells including neutrophils, erythrocytes and macrophages, oedema fluid and fibrin with formation of hyaline membranes [22]. Remarkably, epithelial cell originated syncytium was observed in the alveolar lumen [22]. Ultrastructural analysis of lungs further confirmed the abnormality of lung cells after SARS-CoV-2 infection [17,21]. In addition, macrophages, type I (flat), and type II (cuboidal) pneumocytes in the affected lung tissues were demonstrated positive for SARS-CoV-2 antigens [21,22]. Interstitial pneumonia was presented in all the four NHP models but the diffusive alveolitis and more severe lung injury were seen only in the rhesus macaque and the African green monkey. Meanwhile, SARS-CoV-2 antigen expression, inflammatory infiltration, tissue impair, and hyperplasia were also detectable in the nasal turbinate and respiratory tract. Although lesions were confirmed in the heart (pericardial effusion), liver, kidney, spleen, and lymph nodes, direct evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among these tissues was not observed [17]. These findings implied that immunopathology may be more important than local infection in the roles of multiple organ failures.

Host innate and adaptive immune responses

Clinically, the host immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection are imbalanced, complicated, and varied over time [6,24,25]. Some severe cases showed strengthened inflammatory responses and uncontrolled cytokine release, indicating a high risk of cytokine storm and robust tissue injury not only in lung, but also systematically [24]. However, numbers of natural killer cells, T- and B-lymphocytes, as well as the percentage of monocytes, eosinophils, and basophils were drastically reduced in other severe cases. These cases usually have higher viral shedding, disease severity, and poor clinical outcome [26]. Recently, the SARS-CoV-2 receptor, ACE2, was demonstrated as an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells [27]. After SARS-CoV-2 infection, the expression of ACE2 was up-regulated by excessive expressed interferons [27]. In a recent clinical investigation of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection [28], the investigators compared the patients’ symptoms to those of their first infection and found that 68.8% of the convalescent patients had similar severity, 18.8% had worse symptoms, and 12.5% had milder symptoms, suggesting a risk of infection enhancement and more complicated virus-host interplay. As for adaptive immunity, a significant production of IgM and IgG antibodies is observed in patients. However, two clinical studies reported that the severe cases had an increased IgG response and a higher titre of total antibodies than the mild cases [29,30]. Meanwhile, a recent study showed an infectivity-enhancing site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein targeted by antibodies [31]. Collectively, these findings revealed a potential antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). Therefore, whether the antibody response is protective or pathogenic needs to be determined in NHP models.

In the rhesus and cynomolgus macaques of SARS-CoV-2 infection, swollen mesenteric lymph nodes, increased number of T- and B-lymphocytes, and proinflammatory cytokines were detected [17], suggesting a robust host immune response. Meanwhile, significant hematological changes including neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, haematocrits, red blood cells, haemoglobin, and reticulocytes were observed in another rhesus macaque’s study [21]. Importantly, the functional neutralizing antibody (NAb) was detectable from 10 to 12 dpi [17,21] and spike-specific NAb can be detected at 14 dpi [18]. Re-challenge of SARS-CoV-2 failed to cause diseases in three rhesus macaques recovered from initial infection [18], suggesting that vaccine or antibody-based therapy might be effective. Although ADE was not observed in the three re-infected rhesus macaques, this needs to be further assessed in more NHP models with a larger number, as well as large-scale randomized controlled clinical trials. Therefore, functional analysis and quantification of serum antibody by ELISA and cell-based functional tests [30,32–34] are essential for evaluating the ADE.

In summary, three points are extracted here from the studies of the interaction between the NHPs and SARS-CoV-2. First, anomalous host immune responses may lead to tissue damage, locally or systemically. Secondly, host factors including cellular receptor (ACE2), cytokines, chemokines, and interferons may play important roles to enhance or suppress infection and pathogenesis. Finally, high NAb titre in serum is adequate to prevent transmission.

Evaluating vaccines and drugs in NHPs

After the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2, more than one hundred vaccines and drugs are currently under development worldwide [35]. An appropriate animal study is necessary to test the in vivo safety and effect of vaccines and drugs. The NHP model has been used for testing the efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines generated by different technologies including inactivation [36–38], expression of subunits such as spike protein or receptor-binding site (RBD) [39,40], DNA [41,42], mRNA [43–45], attenuated viral carrier [46–48], as well as drugs with different mechanisms [49–52]. The details of the preclinical NHP studies on some representative SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were summarized in Table 2. In the early stage of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the inactivated vaccines have been rapidly developed and evaluated in rhesus macaques. In contrast to the placebo and control groups, viral RNA was over 100-fold lower in the throat and anal swabs, and undetectable in the lung of the high-dose vaccinated rhesus macaques [36]. Furthermore, no significant lung pathogenesis was observed in the vaccinated rhesus macaques, suggesting an adequate protection effect [36]. The ratio of T-lymphocytes in peripheral blood and concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-2 were stable throughout the vaccination and virus challenge course for 30 days, revealing an absent of ADE [36]. The efficient protective immunity of mRNA vaccines was also well-demonstrated in NHP models [43–45]. In a rhesus macaque model of SARS-CoV-2 infection, mRNA-1273 vaccine candidate induced high NAb level, type 1 helper T cell (Th1) biased CD4-positive T cell responses and low or undetectable Th2 or CD8-positive T cell responses [44]. Viral replication was not detectable in lung tissues at 2 dpi [44]. Collectively, it was demonstrated by the NHP model that the inactivated vaccines and the mRNA vaccines are safe and effective in protecting NHPs from SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe pneumonia.

Table 2.

Research details for preclinical NHP studies of representative SARS-CoV-2 vaccines derived from different technology roadmaps.

| Research groups and NHP study of vaccines | Corbett et al. | Yang et al. | Yu et al. | Gao et al. | Wang et al. | Yang et al. | Sanchez-Felipe et al. | Mercado et al. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA vaccine | DNA vaccine | Inactivated vaccine | Subunit vaccine | Attenuated viral carrier vaccine | ||||

| Identifier and targets | mRNA-1273 (spike) | SW0123 (spike) | S(spike)/S.dCT/S.dTM/S1/RBD | PiCoVacc (mix) | BBIBP-CorV (mix) | RBD (aa319–545) | YF-S0 (yellow fever virus 17D vectored spike) | Ad26.COV2.S (adenovirus serotype 26 vectored spike) |

| Species | Rhesus macaques | Rhesus macaques | Rhesus macaques | Rhesus macaques | Cynomolgus macaques | Rhesus macaques | ||

| Gender and age and amount | 12 of each sex; age range; 3–6 years | 4 (sex and age were unknown) | 35 male and female (6-12 years) | 20 (sex not clear; 3–4 years) | 10 (sex not clear; 3–4 years) | 12 (sex not clear; 5–9 years) | 12 mature male | 52 male and female (6-12 years) |

| Vaccination dose | 10/100 μg two doses | 200 μg three doses | 5 mg two doses | 3/6 mg three doses | 2/8 mg two doses | 20/40 μg two doses | 1×10E5 PFU two doses | 1×10E11 viral particles one dose |

| Infection dose | 7.5 × 10E6 PFU | 1 × 10E6 PFU | 1.1 × 10E4 PFU | 1 × 10E6 TCID50 | 5 × 10E5 PFU | 1.5 × 10E4 TCID50 | 1.1 × 10E4 PFU | |

| Infection route | Intratracheal and intranasal | Intratracheal and intranasal | Intratracheal | Intranasal | Intratracheal and intranasal | |||

| Protective effect | Viral shedding in respiratory tract, viral replication and inflammation in lung are rarely detectable by 2 dpi | Viral RNA is undetectable in respiratory tract and lung tissues at 7 dpi; SARS-CoV-2 induced lung pathological lesions were restored | Viral shedding in respiratory tract is suppressed by the five vaccines in varied degrees from 0 to 14 dpi | Viral shedding in respiratory tract, viral replication and inflammation in lung are suppressed from 0 to 7 dpi with a dose-dependent manner | Viral shedding in respiratory tract, viral replication and inflammation in lung are suppressed from 0 to 7 dpi | Viral shedding in respiratory tract was suppressed from 0 to 4 dpi | Viral shedding in respiratory tract is suppressed by the Ad26.COV2.S from 0 to 10 dpi | |

| Clinical translation | Approved | Preclinical study | Preclinical study | Approved (over 16 billion shots applied) | Clinical trail | Preclinical study | Clinical trail | |

In order to inhibit viral replication and restore lung injury in the patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, drugs were developed and evaluated in animal models. Remdesivir (GS5734), a broad spectrum antiviral nucleotide prodrug, showed anti-MERS-CoV activity in cell culture study, mice, and rhesus macaques [53,54], and was further tested on rhesus macaques with SARS-CoV-2 infection [55]. Intravenous remdesivir treatment significantly reduced clinical symptom and chest X-ray scores, decreased virus titres in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and restored severe pneumonia in rhesus macaques. The lipoglyco-peptide antibiotic Dalbavancin can block the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and host receptor ACE2, suppress viral replication and alleviate severe pneumonia in both hACE2 transgenic mice and rhesus macaques [49]. The (β-gal)-activated prodrug SSK1 restores severe pneumonia in rhesus macaques by down-regulating the SARS-CoV-2-induced proinflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 [50]. The NAb targets RBD on the spike protein showed prominent efficiency of preventing and treating SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques [51,52].

Discussion

The worldwide COVID-19 pandemic has been persisting for more than one year. However, many fundamental questions regarding SARS-CoV-2 infection and its pathogenesis are still unclear. Present studies have demonstrated that the NHP is a state-of-art animal model for investigating SARS-CoV-2 infection and its pathogenesis. Although the NHP models are available to mimic SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans and to exhibit typical symptoms and disease progress, some important potential effectors including age, gender, species, and host immune statues need to be tested in a larger sample size so that a statistical evaluation can be performed to draw a robust conclusion. Moreover, some obstacles exist in the translation of preclinical NHP studies to clinical trials. First, the experimental results from NHP models cannot always predict clinical outcomes. For instance, the antiviral drug remdesivir showed well-demonstrated therapeutic efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in the rhesus macaques [55] but a limited clinical benefit for COVID-19 patients [56]. However, the mRNA vaccine is demonstrated to establish protective immunity in both the NHP models [44] and humans [57]. These varying results are caused by many factors. The mRNA vaccine can induce neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific T cells to eliminate the infectious viral particles directly, which were also recognized as indicators of disease severity [58]. In brief, the humans and NHPs with high NAb and robust T cell responses showed stronger immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection and milder disease progress. Additionally, dynamic changes of these two indicators were detectable and similar in both the NHP models and humans. However, remdesivir cannot directly reduce the infectious viral particles. Furthermore, the lack of a clinical indicator limits its translation from NHP models to clinical trials. Secondly, the new emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants may cause breakthrough infection in vaccinated populations and enhanced disease, which necessitates an urgent development of optimized vaccines and drugs. Unique mutations can impact the infectivity, transmission capacity, and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 variants [59–61]. The new emerging variants showed enhanced infectivity and transmission capacity [62–64], as well as strong resistance to the convalescent serum and vaccine-induced NAb [65–67]. These findings revealed that the protection efficiency of RBD-derived vaccines might be decreased by the emerging of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Therefore, a systematic evaluation of typical SARS-CoV-2 variants in NHP and other animal models will be helpful to understand viral evolution and find out the critical mutation sites. More importantly, to know the “off-target” effect of current vaccine and drugs on the new emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants, a rapid efficiency analysis in an animal model is urgently in need. Thirdly, several unique clinical symptoms such as asymptomatic infection [68,69], vomiting, diarrhoea and gastrointestinal infection [70,71], venous thromboembolism, lymphopenia [72], and sepsis were recently reported in human patients. However, these symptoms were rarely observed in NHP studies. In addition, patients with diseases such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and chronic virus infections showed a higher severity and mortality after SARS-CoV-2 infection [6]. Therefore, the evaluation of combined therapy strategies that combat both SARS-CoV-2 and these diseases in animal models are necessary for clinical therapy of these high-risk populations.

Although the NHPs have been recognized as ideal animal models to study human infectious diseases, their application was largely limited by several drawbacks. For instance, strong ethic restrictions, high costs, relatively low breeding efficiency, long-term maturation, large body size, complicated operations and individual variation among NHPs make it difficult to conduct research in a large sample size. Moreover, the NHP models for pathogens with highly infectivity (such as SARS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2, and MERS-CoV) should be operated in ABSL-3 laboratory and isolation devices throughout the whole infection course. The NHP models and facilities at hand are inadequate to meet the huge demand, which might impede our further understanding of the mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 pathology, protective immunology, and drug therapy, and limit further translation of vaccines and drugs. Indeed, the development of many vaccines and drugs was blocked in the stage of preclinical animal study.

Fortunately, advances in technologies include scalable NHP clones, stable gene modification, rapid passage, and maturation provide efficient approaches to optimize SARS-CoV-2-infected NHP models. Liu et al. recently reported the accelerated passage of gene-modified cynomolgus macaques by hormone-induced precocious puberty [73]. By using the NHP cloning technology, the investigators can rapidly achieve a scalable production of standardized laboratory NHP strains with relatively low individual diversity than the NHPs generated by traditional methods. Moreover, the gene modification technology is useful to identify and verify the roles of host genes in the process of SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis. For instance, the NHP modified with genes that enhance SARS-CoV-2 infection and pathogenesis might better resemble human patients with high viral load and severe respiratory symptoms. Collectively, the optimization of NHP models will expand their application and translation in the future studies of SARS-CoV-2 and new emerged pathogens. Overall, we should keep the high experimental standards and strict operation to ensure that the safety and effectiveness of each tested vaccine or antiviral (anti-inflammatory) agent are accurately displayed in the experimental animals.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [Grant Numbers 2020M682092, 2020T130362]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number 82002139]; National Science Key Research and Development Project [Grant Number 2020YFC0842600]; CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences [Grant Number 2019RU022].

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of covid-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang T, Du Z, Zhu F, et al. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of covid-19. Lancet. 2020;395:e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poon LLM, Peiris M.. Emergence of a novel human coronavirus threatening human health. Nat Med. 2020;26:317–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen E, Koopmans M, Go U, et al. Comparing sars-cov-2 with sars-cov and influenza pandemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:e238–e244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanco-Melo D, Nilsson-Payant BE, Liu WC, et al. Imbalanced host response to sars-cov-2 drives development of covid-19. Cell. 2020;181:1036–1045. e1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan L, Tang Q, Cheng T, et al. Animal models for emerging coronavirus: progress and new insights. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:949–961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marsh M, Helenius A.. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell. 2006;124:729–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Wang Y, et al. Single-cell rna expression profiling of ace2, the receptor of sars-cov-2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:756–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou X, Chen K, Zou JW, et al. Single-cell rna-seq data analysis on the receptor ace2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-ncov infection. Front Med-Prc. 2020;14:185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao B, Ni C, Gao R, et al. Recapitulation of sars-cov-2 infection and cholangiocyte damage with human liver ductal organoids. Protein Cell. 2020;11:771–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontelli MC, Castro IA, Martins RB, et al. Infection of human lymphomononuclear cells by sars-cov-2. bioRxiv: the preprint server for biology; 2020.

- 14.Zang R, Castro MF G, McCune BT, et al. Tmprss2 and tmprss4 promote sars-cov-2 infection of human small intestinal enterocytes. Sci Immunol. 2020;5: eabc3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sungnak W, Huang N, Becavin C, et al. Sars-cov-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. 2020;26:681–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiao L, Yang Y, Yu W, et al. The olfactory route is a potential way for sars-cov-2 to invade the central nervous system of rhesus monkeys. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu S, Zhao Y, Yu W, et al. Comparison of nonhuman primates identified the suitable model for covid-19. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng W, Bao L, Liu J, et al. Primary exposure to sars-cov-2 protects against reinfection in rhesus macaques. Science. 2020;369:818–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng W, Bao L, Gao H, et al. Ocular conjunctival inoculation of sars-cov-2 can cause mild covid-19 in rhesus macaques. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woolsey C, Borisevich V, Prasad AN, et al. Establishment of an african green monkey model for covid-19 and protection against re-infection. Nat Immunol. 2021;22:86–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munster VJ, Feldmann F, Williamson BN, et al. Respiratory disease in rhesus macaques inoculated with sars-cov-2. Nature. 2020;585:268–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rockx B, Kuiken T, Herfst S, et al. Comparative pathogenesis of covid-19, mers, and sars in a nonhuman primate model. Science. 2020;368:1012–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shan C, Yao YF, Yang XL, et al. Infection with novel coronavirus (sars-cov-2) causes pneumonia in rhesus macaques. Cell Res. 2020;30:670–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Z, Ren L, Zhang L, et al. Heightened innate immune responses in the respiratory tract of covid-19 patients. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:883–890. e882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Netea MG, Rovina N, et al. Complex immune dysregulation in covid-19 patients with severe respiratory failure. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:992–1000. e1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao X.Covid-19: Immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:269–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziegler CGK, Allon SJ, Nyquist SK, et al. Sars-cov-2 receptor ace2 is an interferon-stimulated gene in human airway epithelial cells and is detected in specific cell subsets across tissues. Cell. 2020;181:1016–1035. e1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Kaperak C, Sato T, et al. Covid-19 reinfection: a rapid systematic review of case reports and case series. J Investig Med: the Official Publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 2021;69:1253–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang B, Zhou X, Zhu C, et al. Immune phenotyping based on the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and igg level predicts disease severity and outcome for patients with covid-19. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao J, Yuan Q, Wang H, et al. Antibody responses to sars-cov-2 in patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis: an Official Publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020;71:2027–2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WTS YL, Kishikawa J-i, Hirose M, et al. An infectivity-enhancing site on the sars-cov-2 spike protein targeted by antibodies. Cell. 2021;184(13):3452-3466 e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nie J, Li Q, Wu J, et al. Establishment and validation of a pseudovirus neutralization assay for sars-cov-2. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of sars-cov-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with sars-cov. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Wang S, Wu Y, et al. Virus-free and live-cell visualizing sars-cov-2 cell entry for studies of neutralizing antibodies and compound inhibitors. Small Meth. 2021;5:2001031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu C, Zhou Q, Li Y, et al. Research and development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for covid-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Cent Sci. 2020;6:315–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Q, Bao L, Mao H, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for sars-cov-2. Science. 2020;369:77–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yadav PD, Ella R, Kumar S, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of inactivated sars-cov-2 vaccine candidate, bbv152 in rhesus macaques. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H, Zhang Y, Huang B, et al. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate, bbibp-corv, with potent protection against sars-cov-2. Cell. 2020;182:713–721. e719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J, Wang W, Chen Z, et al. A vaccine targeting the rbd of the s protein of sars-cov-2 induces protective immunity. Nature. 2020;586:572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang JG, Su D, Song TZ, et al. S-trimer, a covid-19 subunit vaccine candidate, induces protective immunity in nonhuman primates. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu J, Tostanoski LH, Peter L, et al. DNA vaccine protection against sars-cov-2 in rhesus macaques. Science. 2020;369:806–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Bi Y, Xiao H, et al. A novel DNA and protein combination covid-19 vaccine formulation provides full protection against sars-cov-2 in rhesus macaques. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021;10:342–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang R, Deng Y, Huang B, et al. A core-shell structured covid-19 mrna vaccine with favorable biodistribution pattern and promising immunity. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbett KS, Flynn B, Foulds KE, et al. Evaluation of the mrna-1273 vaccine against sars-cov-2 in nonhuman primates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1544–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang NN, Li XF, Deng YQ, et al. A thermostable mrna vaccine against covid-19. Cell. 2020;182:1271–1283. e1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanchez-Felipe L, Vercruysse T, Sharma S, et al. A single-dose live-attenuated yf17d-vectored sars-cov-2 vaccine candidate. Nature. 2021;590:320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mercado NB, Zahn R, Wegmann F, et al. Single-shot ad26 vaccine protects against sars-cov-2 in rhesus macaques. Nature. 2020;586:583–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng L, Wang Q, Shan C, et al. An adenovirus-vectored covid-19 vaccine confers protection from sars-cov-2 challenge in rhesus macaques. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang G, Yang ML, Duan ZL, et al. Dalbavancin binds ace2 to block its interaction with sars-cov-2 spike protein and is effective in inhibiting sars-cov-2 infection in animal models. Cell Res. 2021;31:17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu S, Zhao J, Dong J, et al. Effective treatment of sars-cov-2-infected rhesus macaques by attenuating inflammation. Cell Res. 2021;31:229–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baum A, Ajithdoss D, Copin R, et al. Regn-cov2 antibodies prevent and treat sars-cov-2 infection in rhesus macaques and hamsters. Science. 2020;370:1110–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi R, Shan C, Duan X, et al. A human neutralizing antibody targets the receptor-binding site of sars-cov-2. Nature. 2020;584:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Wit E, Feldmann F, Cronin J, et al. Prophylactic and therapeutic remdesivir (gs-5734) treatment in the rhesus macaque model of mers-cov infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(12):6771–6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lo MK, Feldmann F, Gary JM, et al. Remdesivir (gs-5734) protects African Green monkeys from nipah virus challenge. Sci Trans Med. 2019;11(494):eaau9242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williamson BN, Feldmann F, Schwarz B, et al. Clinical benefit of remdesivir in rhesus macaques infected with sars-cov-2. Nature. 2020;585(7824):273–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Zhang D, Du G, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe covid-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Prevention and attenuation of covid-19 with the bnt162b2 and mrna-1273 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sahin U, Muik A, Vogler I, et al. Bnt162b2 vaccine induces neutralizing antibodies and poly-specific t cells in humans. Nature. 2021;595:572–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia-Beltran WF, Lam EC, St Denis K, et al. Multiple sars-cov-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell. 2021;184:2372–2383. e2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kupferschmidt K.Fast-spreading U.K. virus variant raises alarms. Science. 2021;371:9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kemp SA, Collier DA, Datir RP, et al. Sars-cov-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature. 2021;592:277–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hou YJ, Chiba S, Halfmann P, et al. Sars-cov-2 d614 g variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo. Science. 2020;370:1464–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Plante JA, Liu Y, Liu J, et al. Spike mutation d614 g alters sars-cov-2 fitness. Nature. 2021;592:116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weissman D, Alameh MG, de Silva T, et al. D614 g spike mutation increases sars cov-2 susceptibility to neutralization. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:23–31. e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang P, Nair MS, Liu L, et al. Antibody resistance of sars-cov-2 variants b.1.351 and b.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu Y, Liu J, Xia H, et al. Neutralizing activity of bnt162b2-elicited serum. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:1466–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou D, Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, et al. Evidence of escape of sars-cov-2 variant b.1.351 from natural and vaccine-induced sera. Cell. 2021;184:2348–2361. e2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with covid-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63:706–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of covid-19. Jama. 2020;323:1406–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of sars-cov-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1831–1833. e1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gu J, Han B, Wang J.. Covid-19: gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1518–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang T, Chen R, Liu C, et al. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of covid-19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e362–e363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu Z, Li K, Cai Y, et al. Accelerated passage of gene-modified monkeys by hormone-induced precocious puberty. Natl Sci Rev. 2021;8(7):nwab083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]