Abstract

Background

Single group data present unique challenges for synthesises of evidence. Proportional meta-analysis is becoming an increasingly common technique employed for the synthesis of single group data. Proportional meta-analysis shares many similarities with the conduct and reporting of comparative, or pairwise, meta-analysis. While robust and comprehensive methods exist detailing how researchers can conduct a meta-analysis that compares two (or more) groups against a common intervention, there is a scarcity of methodological guidance available to assist synthesisers of evidence in the conduct, interpretation, and importance of proportional meta-analysis in systematic reviews.

Main body

This paper presents an overview targeted to synthesisers of evidence and systematic review authors that details the methods, importance, and interpretation of a proportional meta-analysis. We provide worked examples of how proportional meta-analyses have been conducted in research syntheses previously and consider the methods, statistical considerations, and presentation of this technique.

Conclusion

This overview is designed to serve as practical guidance for synthesisers of evidence in the conduct of proportional meta-analyses.

Keywords: Research synthesis, meta-analysis, Proportional meta-analysis, Systematic reviews

Background

Meta-analysis is a common method of synthesis of quantitative data from two or more independent yet comparable studies included in a systematic review [1–3]. The majority of meta-analyses reported in the medical literature are comparative pairwise (two group) analyses and are largely used to establish the effect of an intervention (or exposure) compared with a comparator to generate a pooled estimate of effect, expressed as a risk ratio, odds ratio, incidence rate ratio or weighted mean difference (among many others) [4]. There are also approaches for multiple group meta-analysis (i.e network meta-analysis) and for single group meta-analysis (proportional meta-analysis, meta-analysis of means, correlation coefficients, incidence rates etc).

As with pairwise meta-analysis (where data for two unique groups are synthesised to produce a pooled estimate of effect), the goal of the meta-analysis of proportions is the generation of a single summary estimate and its variance. Termed ‘proportional meta-analysis’, this method of data synthesis allows for calculation of a pooled, overall proportion from a number of individual proportions. Any dichotomous data or data that can be reported as a percentage can be included in a proportional meta-analysis. These meta-analyses are most commonly used to quantify disease occurrence in populations to answer questions related to both the prevalence and incidence of disease and are typically presented in systematic reviews dealing with prevalence and cumulative incidence data. However, proportional meta-analysis may also be used for review types other than prevalence, including when trying to identify evidence regarding the effectiveness of treatments or interventions, overall prognosis or baseline risk [5, 6]. The purpose of this paper is to introduce the concepts of proportional meta-analysis, practical guidance for systematic reviewers including a proportional meta-analysis in their review, the statistical considerations specific to this analysis and how this format of synthesis can be utilised by systematic reviewers across different review types with different questions and indications.

Main body

Systematic reviews of prevalence and cumulative incidence

In terms of systematic reviews, the most common usage for a proportional meta-analysis is to assist in answering a question related to the prevalence or the incidence of disease in a population. There has been a 10-fold increase in the number of systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence published from 2007 to 2017 with the terms “systematic review” and “prevalence” in the title, with 64.7% of these reviews performing a proportional meta-analysis to synthesise prevalence estimates [7]. There are several measures of disease frequency: point-prevalence is an indicator of who has a disease at a certain point in time; period-prevalence indicates who has the disease within a given time frame; and cumulative incidence is an indicator of how often the disease develops (i.e. new cases of a disease among a population) over a certain period [8, 9]. These metrics are reported in the literature in terms of their proportions, that is the number of cases divided by the total population number [4]. Lifetime prevalence (a commonly reported period-prevalence), is the proportion of a population who has ever had the disease of interest. Given the nature of the estimates and that they are all have temporal dependence, for any condition, lifetime prevalence is expected to be higher than either point or a more restricted period prevalence. Prevalence and cumulative incidence estimates are normally generated through observational studies and proportions are the typical format in which data is likely to take when conducting a systematic review of prevalence or cumulative incidence [8, 9]. Prevalence and incidence reviews may not only address the prevalence or incidence of disease itself, but may also answer questions related to many other types of variables. For instance, systematic reviews of prevalence with associated proportional meta-analyses have been conducted when investigating the symptoms of a disease [10]; pre-existing conditions [11], events [12] and cultural practices or behaviours [13]. Proportional-meta analyses can also provide quantitative descriptions regarding specific covariates of disease frequency, such as the geographical distribution of a variable [14] or the difference in frequency of a particular disease between males and females [15].

Proportional meta-analysis in these review types provides a single summary estimate of the prevalence or incidence of a condition across the included studies. The appropriateness of conducting meta-analysis of this type of data is contentious, as the individual studies contributing to such a meta-analysis commonly have been conducted in different contexts and the prevalence and cumulative incidence estimates produced from these studies are reflective of unique population characteristics [16].

This raises some concerns when proportional meta-analysis assumes homogeneity, and an average estimate across many different populations may be of little clinical use [4]. However, for a systematic review with the goal of estimating global disease burden, a proportional meta-analysis is argued to still be an appropriate and effective method of data synthesis [17]. For example, if there is interest in investigating the likely disease burden for a certain population and if no primary studies have been conducted in that population of interest, then it may be prudent to find studies that are similar to the population of interest that report proportional data, and synthesise the data with proportional meta-analysis [18].

Review Example 1

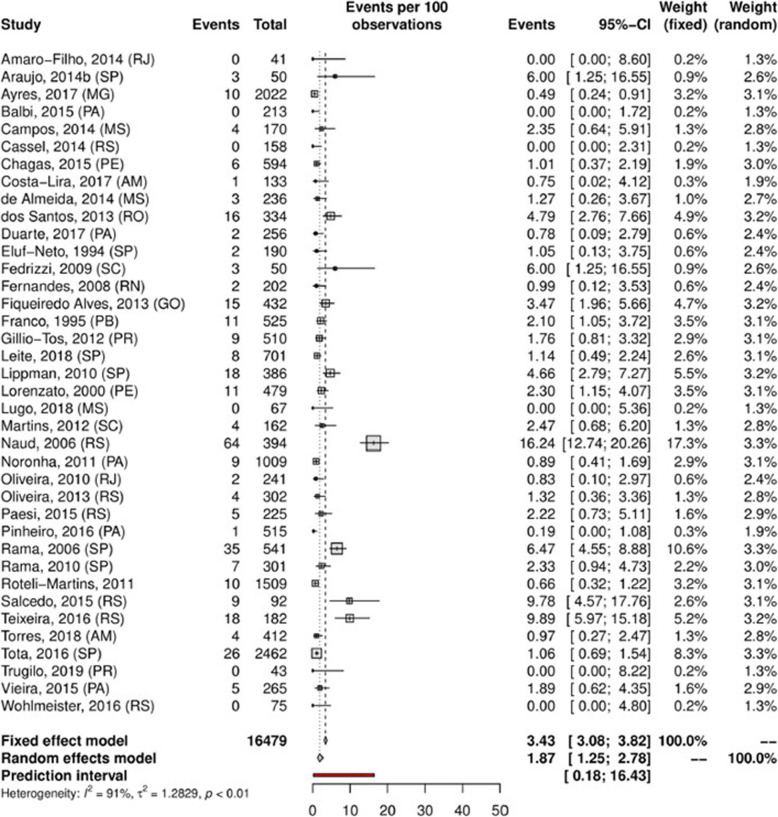

Understanding and estimating the prevalence of a condition or practice can also be beneficial during the planning and development of new health resources on a societal scale. When governments are required to allocate resources to health expenditure, they must undertake significant investigation or “strategic purchasing” of any new decision made [19]. One of the first considerations for any new decision made is the assessment of population needs [19]. By providing a pooled proportional estimate for a prevalence variable over a designated time period, the results of a proportional meta-analysis (as a component of a well conducted and rigorous systematic review of prevalence and incidence) [9], can enable governments, policy makers and health professionals to make informed decisions regarding the development and delivery of health services [8, 9, 16]. For example, a systematic review was conducted to assess the prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in Brazil to assist health service policy and planning [20]. The authors identified 139 eligible studies comprising more than 50,000 people and were able to conduct a number of proportional meta-analyses by region, population and anatomical site. Figure 1 below is an example forest plot and proportional meta-analysis reporting the prevalence of cervical infection by HPV-18 as 1.87% (Random effects model, 95% CI 1.25–2.78). Based on this research, the authors suggested that public health efforts could be targeted towards specific regions and populations that experience higher HPV prevalence. Furthermore, by conducting individual proportional meta-analyses based on anatomical regions, the authors concluded that HPV (in terms of health policy) should not be approached as a problem restricted to cervical cancer [20].

Fig. 1.

Example prevalence proportional meta-analysis investigating overall prevalence of cervical infection by HPV-18 in Brazil. Created in R, package meta. Reproduced under Creative Commons from: Colpani, V et al. “Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in Brazil: A systematic review and meta-analysis”. PloS one 15.2 (2020): e0229154 [20]

This exemplar proportional meta-analysis (Fig. 1) includes all the familiar hallmarks expected when conducting and reporting a pairwise meta-analysis and serves as a benchmark for the characteristics required when presenting the results of a proportional meta-analysis. The analysis clearly presents the individual study estimates, the individual weight that each study is contributing to the pooled estimate, the pooled estimates with associated 95% confidence intervals, and the statistical tests for heterogeneity. The authors have also provided the pooled estimates using both the fixed and random effects model.

Review Example 2

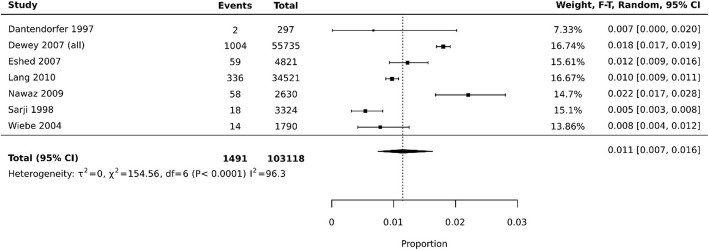

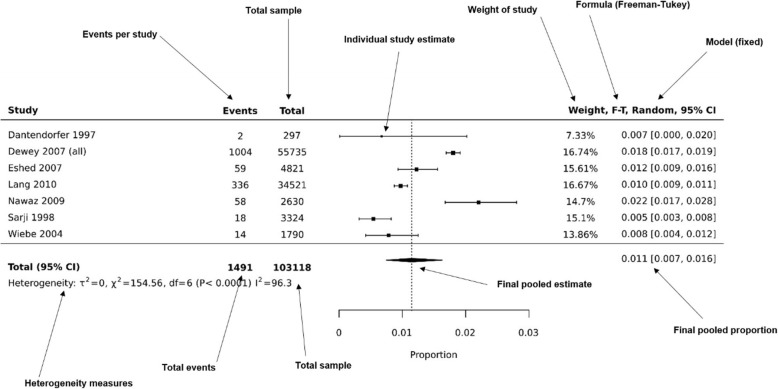

Another example of a forest-plot presenting a proportional meta-analysis can be seen in Fig. 2. This forest-plot has been recreated in JBI SUMARI [21] using data from a systematic review investigating premature scan termination or refusal due to claustrophobia in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [12]. This review included 18 studies (7 studies included in synthesis) and data from more than 100,000 MRI scans.

Fig. 2.

Example prevalence proportional meta-analysis of events, assessing MRI scan terminations or refusals due to claustrophobia. Recreated in JBI SUMARI software using data from: Munn, Z et al. “Claustrophobia in magnetic resonance imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. Radiography 21.2 (2015): e59-e63 [12]

Each black square represents the proportion of premature scan terminations reported in each study. The pooled prevalence is 0.011, or 1.1% (95% CI 0.007–0.016), indicating that of all MRI scans conducted in the synthesised studies, 1.1% of them were terminated prematurely due to claustrophobia. The authors summarised this data by stating that health professionals working in MRI departments need to be prepared to encounter claustrophobic patients and that alternative MRI scanners (wide bore MRI scanners or open MRI systems) may be an appropriate treatment option for claustrophobic patients. The data synthesised using this proportional meta-analysis may be useful for MRI departments, funders, and clinicians to inform the efficient planning of services.

Overall prognosis

Proportional meta-analysis can be a useful tool for providing estimates of overall prognosis, such as the expected mortality from a particular disease. These questions are very similar to prevalence/incidence questions, and many of the methods and ideas underpinning overall prognosis crossover with those of prevalence and incidence systematic reviews. For example, the Centre for Evidence-based Medicine have produced a proportional meta-analysis on mortality from COVID-19 [22].

Systematic reviews of interventions and therapies

Although not common, proportional meta-analyses can also be used in systematic reviews addressing the effectiveness of treatment or interventions. Whilst unable to provide causal information regarding the effectiveness of a treatment, in fields where rigorous comparative studies are lacking, proportional meta-analysis may be useful to summarise the impact of a treatment on a particular condition [23]. This type of information may come from pre-test post-test studies, case series, or a single arm of a randomised controlled trial or other comparative study. Although this type of estimate will likely provide lower certainty than if coming from a comparative meta-analysis, it may still be useful to inform decision making particularly in the absence of higher quality evidence, especially in fields such as surgery where randomised controlled trials are rare [24] (amongst others) (Review Example 3). This principle is true also for pre-clinical studies where investigations may have been performed on a single group in the treatment discovery and testing phase [25, 26].

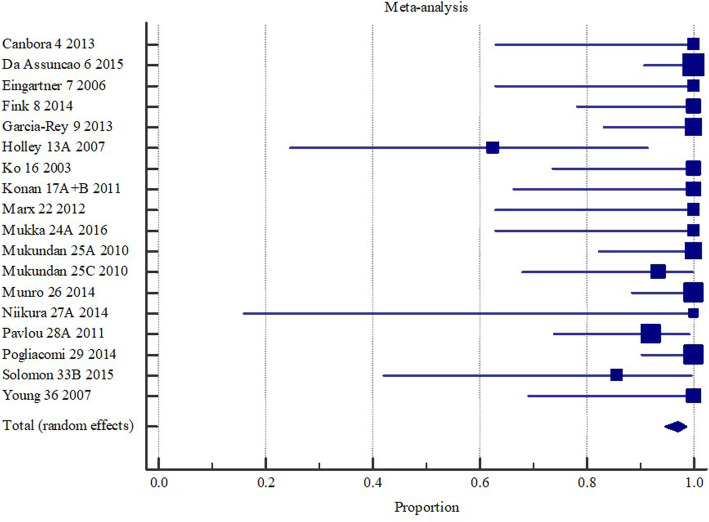

Review Example 3

In an unpublished systematic review assessing the effectiveness of operative interventions in individuals with a hemi or total hip arthroplasty who had sustained a peri-prosthetic fracture, revision surgery was found to achieve union in 97% of the sampled patients (Fig. 3) [27].

Fig. 3.

Union (overall) with revision surgery with or without wires/ cerclage/ cables following hemi or total hip arthroplasty. Created in MedCalc software from: Ianunzio, I et al. “Effectiveness of operative interventions in individuals with a hemi or total hip arthroplasty who sustain a Vancouver B2 peri-prosthetic femoral fracture” [Thesis] The University of Adelaide (2018) [27]

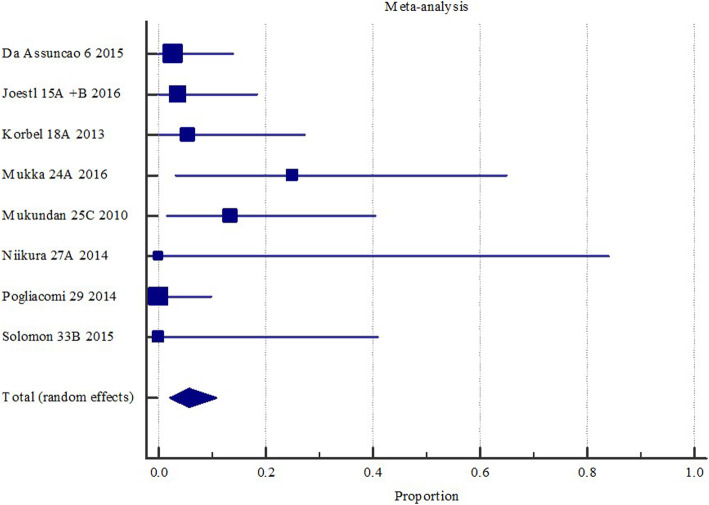

Benefits from these types of analyses include support of decision aids and shared decision making to enable the patient to know what they can expect following surgery [28]. For example, the same review as discussed above identified a 5.7% chance of deep surgical site infection following revision hip replacement surgery, as shown in Fig. 4 [27].

Fig. 4.

Deep surgical site infection with revision surgery with or without wires/ cerclage/ cables following hemi or total hip arthroplasty. Created in MedCalc software from: Ianunzio, I et al. “Effectiveness of operative interventions in individuals with a hemi or total hip arthroplasty who sustain a Vancouver B2 peri-prosthetic femoral fracture” [Thesis] The University of Adelaide (2018) [27]

Diagnostic test accuracy reviews

Although not common and strongly advised against, proportional meta-analysis has been applied in certain diagnostic test accuracy reviews for producing summary estimates of sensitivity and specificity, in a coupled proportional meta-analysis. This has historically been justified as appropriate when the same diagnostic threshold is used across all studies included in the analysis and there is little statistical heterogeneity observed [22, 29, 30]. When diagnostic thresholds vary, diagnostic test accuracy across studies should be analysed using a summary receiver operating characteristic curve. However, this separate pooling of sensitivity and specificity via proportional meta-analysis does not account for the relationship between specificity and sensitivity, which can lead to inaccurate estimates of test accuracy [31]. Bivariate models or hierarchical approaches are necessary for this type of analysis [32–34]. As such, despite proportional meta-analysis being technically possible in this scenario, we advise systematic reviewers conducting reviews of diagnostic test accuracy to avoid proportional meta-analysis. When reading a review of diagnostic test accuracy where pooled estimates have been provided in a coupled meta-analysis of sensitivity and specificity, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Models and formula

Incidence and prevalence are reported in terms of their proportions (discussed above). As described by Barendregt, Doi [4] this implies two important statistical considerations. The first, is that prevalence/incidence will always fall between the values of zero and one. The second, is that the sum of the prevalence/incidence over different categories should always equal one [4]. These rules are important when considering the pooling of proportional data to include in a proportional meta-analysis. Without transformation of the included proportional data the accompanying meta-analyses experience two threats to statistical conclusion validity [35–37]. Firstly, the confidence limits fall outside of the established zero to one range [4]; this may impact on the readability and presentation of the pooled data as a forest-plot. The second concern, and by far the most prudent, is that the variance from studies contributing proportional data at the extreme ends of the zero to one range tends toward zero [4]. This in turn, artificially inflates the weight that these studies contribute towards the pooled-prevalence estimate. Transformation of that data is therefore required during the meta-analysis process to deal with these problems [4, 16]. The two most common methods for performing this transformation are the double arcsine transformation (Freeman-Tukey transformation) and the logit transformation [4]. Both of these transformations calculate a pooled prevalence estimate with a 95% confidence interval under both the fixed and random-effects model. While the logit transformation solves the problem of confidence interval estimates falling outside the zero to one range, it does not necessarily resolve the issues regarding variance from extreme proportional datasets. As the double arcsine transformation addresses both problems listed above it is the preferred transformation method when performing proportional meta-analysis. Once the meta-analysis has been performed on the transformed proportions, a back-transformation is required. For log, logit, and arcsine methods, the back-transformation is straightforward. However, for the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine method there is still no consensus about which back-transformation method should be used [38]. A detailed breakdown and review of transformation and back-transformation methods can be found in the seminal prevalence meta-analysis work from Barendregt, Doi [4]. It is important to note that transformation methods may be dispensable when proportions for studies are close to 50%, for example, situations in which an effect or event is expected to be normally distributed.

As with traditional comparative methods of meta-analysis, there are different options in terms of model choice when performing a proportional meta-analysis (discussed above) [39]. When considering that epidemiological factors typically measured using proportional data are well-known to vary between population characteristics, it has been previously recommended that proportional meta-analyses are performed using the random-effects model [40]. When considering that the fixed-effect model assumes that there is one true estimate measured across studies, this is unlikely to hold true for proportional data synthesised from multiple independent studies. While performing a proportional meta-analysis using the fixed-effect model is possible, authors should be aware of the assumptions this model has on the data and the subsequent inferences that can be made from the final pooled-prevalence estimate [16].

Subgroups and multiple categories

In some instances, proportional meta-analysis, like comparative meta-analysis, can facilitate the presentation of subgroups, or multiple categories (e.g. health status can be expressed as mild, moderate or severe). These cases provide further complications regarding the mode of transformation required [4, 16]. For a detailed statistical breakdown of these transformations we again direct you to the seminal paper on proportional meta-analysis from Barendregt, Doi [4] . Differences between subgroups can be compared and contrasted using the Chi2 test, and an example of how this can be facilitated in practice can be observed in the work of Righy, Rosa [41]. and is discussed in detail below.

Heterogeneity

Since there are no specific tests to assess heterogeneity in proportional meta-analysis, we currently suggest the judicious use of the I2 statistic, noting that there are some issues with its application with these types of data. This statistic describes the variability between proportions between each subgroup expressed as a percentage [42]. Although I2 was developed in the context of comparative data, it is commonly applied to estimate heterogeneity for proportional meta-analysis [43, 44]. In this type of analysis, I2 is usually high. This can be due to the nature of proportional data, where little variance is observed even in studies with small sample size. Moreover, true heterogeneity is expected in prevalence and incidence estimates due to differences in the time and place where included studies were conducted. Therefore, high I2 in the context of proportional meta-analysis does not necessarily mean that data is inconsistent. As such, the results of this test should be interpreted conservatively. The chi squared test and Tau squared can also be used to investigate heterogeneity.

Prediction intervals vs confidence intervals

In a proportional meta-analysis, confidence intervals represent the expected average estimate of all possible studies. There are different methods to estimate the confidence interval for binomial proportions, such as Wald, Wilson-Score, and Clopper Pearson [45]. Whilst the Wald method is frequently used, it may not always be appropriate, particularly in cases with small numbers of patients or extreme estimates. In these cases the Wilson-Score and Clopper Pearson are better options [45]. Further statistical guidance and discussion about these methods can be found in the foundational work by Newcombe [46] and Brown, Cai [47].

The prediction interval estimates the true treatment effects that can be expected in future analysis, considering different settings [48]. As discussed before, we expect different point estimates for proportional data, especially for incidence and prevalence. With high heterogeneity, prediction intervals will be wider than confidence intervals, and can be considered a more conservative way to incorporate uncertainty in the analysis. Where possible, we suggest the estimation of prediction intervals alongside with confidence intervals, especially for prevalence and incidence estimates.

Publication Bias and funnel plots

Tests to evaluate publication bias, such as Egger’s test [49], Begg’s test [50] and funnel plots, were developed in the context of comparative data. They assume studies with positive results are more frequently published than studies with negative results.

Even though it is possible to conduct these tests for proportional meta-analysis, there is no evidence that proportional data adequately adjusts for these tests. Moreover, the assumption of positive results being more often published is not necessarily true for proportional studies, since there is no clear definition or consensus about what a positive result in a meta-analysis of proportion is. Therefore, we do not recommend these analyses for proportional meta-analyses and advise that publication bias be assessed qualitatively.

Software and packages

There are a number of software packages available to support systematic reviewers aiming to conduct a proportional meta-analysis, including JBI SUMARI [21], MedCalc, StatsDirect, MetaXL [4], STATA and R packages. In terms of selecting a particular program, systematic review authors should consider the learning curve associated with some packages, formulas and methods available in the various packages and financial constraints.

Interpreting a proportional meta-analysis forest plot

Depending on the software or package used, each proportional meta-analysis forest plot may appear somewhat differently. However, all good packages should provide the summary estimates from each study (and their confidence interval), the final pooled proportional estimate and the associated confidence interval, measures of heterogeneity, the formula and model used, the weight of each study and ideally, the actual numbers of events and total group sizes. In Fig. 5 below, we highlight these key features in an example meta-analysis produced using JBI SUMARI. To assist in interpretation of the pooled estimate of proportions, it is perhaps simplest to communicate these results as a percentage, such as in the example below where the pooled prevalence is 0.011 (95% CI 0.007–0.016), indicating that 1.1% of population experience the event of interest.

Fig. 5.

Example prevalence proportional meta-analysis of events, assessing MRI scan terminations or refusals due to claustrophobia. Annotated labels highlight key features that should be presented in a proportional meta-analysis and illustrative forest plot. Figure recreated in JBI SUMARI software using data from: Munn, Z et al. “Claustrophobia in magnetic resonance imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis”. Radiography 21.2 (2015): e59-e63 [12]

Conclusion

Proportional meta-analysis is a useful method for pooling data in evidence synthesis. This method is encouraged in the conduct of systematic reviews of prevalence and incidence and also interventions and therapies where appropriate. This paper has provided a high-level overview as to the methods and requirements for conducting and presenting proportional meta-analyses. When performed and interpreted correctly, proportional meta-analyses can provide systematic reviewers and evidence synthesisers answers to questions that have previously been under-investigated.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- HPV

Human Papillomavirus

- MRI

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

- CI

Confidence Interval

Authors’ contributions

THB contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, writing, review and editing of subsequent. Drafts. CBM contributed to the methodology, writing, review and editing of subsequent drafts. CS contributed to the methodology, writing, review and editing of subsequent drafts. VC contributed to the methodology, writing, review and editing of subsequent drafts. MF contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, writing, review and editing of subsequent drafts. EA contributed to the writing, review and editing of subsequent drafts. ZM contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, writing, review and editing of subsequent drafts. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests and no funding was received for this work.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rao SR, Graubard BI, Schmid CH, Morton SC, Louis TA, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Meta-analysis of survey data: application to health services research. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2008;8(2):98–114. doi: 10.1007/s10742-008-0032-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Card NA. Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015.

- 3.Kahn SK. Systematic reviews to support evidence-based medicine: how to review and apply findings of healthcare research. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2003.

- 4.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2013;67(11):974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley RD, Moons KG, Snell KI, Ensor J, Hooft L, Altman DG, et al. A guide to systematic review and meta-analysis of prognostic factor studies. BMJ. 2019;364:k4597. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iorio A, Spencer FA, Falavigna M, Alba C, Lang E, Burnand B, et al. Use of GRADE for assessment of evidence about prognosis: rating confidence in estimates of event rates in broad categories of patients. BMJ. 2015;350:h870. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges Migliavaca C, Stein C, Colpani V, Barker TH, Munn Z, Falavigna M, et al. How are systematic reviews of prevalence conducted? A methodological study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12874-020-00975-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munn Z, Stern C, Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Jordan Z. What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12874-017-0468-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2014;3(3):123–128. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Q-F, Tan L, Wang H-F, Jiang T, Tan M-S, Tan L, et al. The prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Escobar-Morreale HF, Santacruz E, Luque-Ramírez M, Botella Carretero JI. Prevalence of ‘obesity-associated gonadal dysfunction’in severely obese men and women and its resolution after bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(4):390–408. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Murphy F. Claustrophobia in magnetic resonance imaging: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiography. 2015;21(2):e59–e63. doi: 10.1016/j.radi.2014.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parola V, Coelho A, Cardoso D, Sandgren A, Apóstolo J. Prevalence of burnout in health professionals working in palliative care: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2017;15(7):1905–1933. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tham Y-C, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng C-Y. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(11):2081–2090. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, Hirst JA, O’Callaghan CA, Lasserson DS, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease–a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2016;11(7):e0158765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–153. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jablensky A. The epidemiological horizon. Schizophrenia. 2003:203–31.

- 18.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D. The systematic review of prevalence and incidence data. Adelaide: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2014. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization . Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colpani V, Soares Falcetta F, Bacelo Bidinotto A, Kops NL, Falavigna M, Serpa Hammes L, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0229154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Munn Z, Aromataris E, Tufanaru C, Stern C, Porritt K, Farrow J, et al. The development of software to support multiple systematic review types: the Joanna Briggs institute system for the unified management, assessment and review of information (JBI SUMARI) Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2019;17(1):36–43. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macaskill P, Gatsonis C, Deeks J, Harbord R, Takwoingi Y. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy. Version 09. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23(2):60–63. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook JA. The challenges faced in the design, conduct and analysis of surgical randomised controlled trials. Trials. 2009;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schizas D, Frountzas M, Sgouromallis E, Spartalis E, Mylonas KS, Papaioannou TG, et al. Esophageal defect repair by artificial scaffolds: a systematic review of experimental studies and proportional meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2020;34(3):doaa104. doi: 10.1093/dote/doaa104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Legatti SAM, El Dib R, Legatti E, Botan AG, Camargo SEA, Agarwal A, et al. Acute kidney injury in cats and dogs: a proportional meta-analysis of case series studies. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ianunzio JR. Effectiveness of operative interventions in individuals with a hemi or total hip arthroplasty who sustain a Vancouver B2 peri-prosthetic femoral fracture [thesis] Adelaide: The University of Adelaide; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pham C, Lizarondo L, Karnon J, Aromataris E, Munn Z, Gibb C, et al. Strategies for implementing shared decision making in elective surgery by health care practitioners: a systematic review. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(2):582–601. doi: 10.1111/jep.13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee J, Kim KW, Choi SH, Huh J, Park SH. Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating diagnostic test accuracy: a practical review for clinical researchers-part II. Statistical methods of meta-analysis. Korean J Radiol. 2015;16(6):1188–1196. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.6.1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell JM, Klugar M, Ding S, Carmody DP, Hakonsen SJ, Jadotte YT, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy: methods for systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):154–162. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Decks JJ. Systematic reviews in health care: systematic reviews of evaluations of diagnostic and screening tests. BMJ. 2001;323(7305):157–162. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7305.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harbord RM, Deeks JJ, Egger M, Whiting P, Sterne JA. A unification of models for meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy studies. Biostatistics. 2007;8(2):239–251. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reitsma JB, Glas AS, Rutjes AW, Scholten RJ, Bossuyt PM, Zwinderman AH. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58(10):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rutter CM, Gatsonis CA. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat Med. 2001;20(19):2865–2884. doi: 10.1002/sim.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.García-Pérez MA. Statistical conclusion validity: some common threats and simple remedies. Front Psychol. 2012;3:325. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bland M. An introduction to medical statistics. UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirkwood BR. In: Essential medical statistics. 2. Sterne JA, Kirkwood BR, editors. Malden: Blackwell Science; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarzer G, Chemaitelly H, Abu-Raddad LJ, Rücker G. Seriously misleading results using inverse of freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10(3):476–483. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Stephenson M, Aromataris E. Fixed or random effects meta-analysis? Common methodological issues in systematic reviews of effectiveness. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):196–207. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saha S, Chant D, Mcgrath J. Meta-analyses of the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia: conceptual and methodological issues. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17(1):55–61. doi: 10.1002/mpr.240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Righy C, Rosa RG, da Silva RTA, Kochhann R, Migliavaca CB, Robinson CC, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in adult critical care survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2489-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2021.

- 43.Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Munn Z, Falavigna M. Quality assessment of prevalence studies: a systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;127:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dunnigan K. Confidence interval calculation for binomial proportions. Indianapolis: MWSUG Conference; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newcombe RG. Interval estimation for the difference between independent proportions: comparison of eleven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17(8):873–890. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<873::AID-SIM779>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci. 2001;16(2):101–133. doi: 10.1214/ss/1009213286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Spiegelhalter DJ. A re-evaluation of random-effects meta-analysis. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2009;172(1):137–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2008.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Increase in studies of publication bias coincided with increasing use of meta-analysis. Br Med J. 1997;316:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994:1088–101. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.