Abstract

Aim and objectives

This review analysed the implementation and integration into healthcare systems of maternal and newborn healthcare interventions in Africa that include community health workers to reduce maternal and newborn deaths.

Background

Most neonatal deaths (99%) occur in low‐ and middle‐income countries, with approximately half happening at home. In resource‐constrained settings, community‐based maternal and newborn care is regarded as a sound programme for improving newborn survival. Health workers can play an important role in supporting families to adopt sound health practices, encourage delivery in healthcare facilities and ensure timeous referral. Maternal and newborn mortality is a major public health problem, particularly in sub‐Saharan Africa, where the Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6 were not achieved at the end of 2015.

Methods

The review includes quantitative, qualitative and mixed‐method studies, with a data‐based convergent synthesis design being used, and the results grouped into categories and trends. The review took into account the participants, interventions, context and outcome frameworks (PICO), and followed the adapted PRISMA format for reporting systematic reviews of the qualitative and quantitative evidence guide checklist.

Results

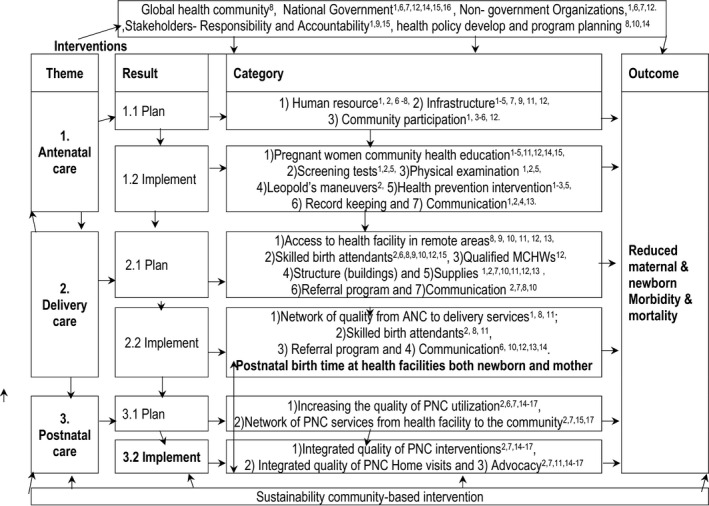

The results from the 17 included studies focused on three themes: antenatal, delivery and postnatal care interventions as a continuum. The main components of the interventions were inadequate, highlighting the need for improved planning before each stage of implementation. A conceptual framework of planning and implementation was elaborated to improve maternal and newborn health.

Conclusion

The systematic review highlight the importance of thoroughly planning before any programme implementation, and ensuring that measures are in place to enable continuity of services.

Relevant to the clinical practice

Conceptual framework of planning and implementation of maternal and newborn healthcare interventions by maternal community health workers.

Keywords: Africa, maternal community health workers, maternal/ newborn healthcare, nurse/ midwifery primary health care, program planning and implementation, systematic review

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Planning before implementing interventions is essential to strengthen maternal and newborn health program policies and practices.

The findings can update clinical practice, maternal community health workers roles and responsibilities, and guide a policy review in an effort to improve health systems and reduce maternal and newborn mortality using best practices.

Integrated community‐based interventions are essential to ensure that the quality of antenatal, delivery and postnatal care interventions can be put into effect and effectively sustained.

1. INTRODUCTION

Most neonatal deaths (99%) occur in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC), with approximately half happening at home (Bell & Marais, 2015). Many LMIC employ community health workers as part of their primary healthcare strategies, their roles and responsibilities varying across and even within countries (Okuga et al., 2015). In resource‐constrained settings, extension and community health workers (CHWs) can play an important role in supporting families to adopt sound health practices, encourage delivery in healthcare facilities and ensure timeous referral of mothers and newborns (Black et al., 2016). Maternal and newborn mortality is a major public health problem, particularly in sub‐Saharan Africa (SSA), where the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 4, 5 and 6 were not achieved by the end of 2015, with little reduction in mother and child mortality (Garenne, 2015). Reducing neonatal mortality in SSA is therefore an important public health priority (Okawa et al., 2015).

Community‐based maternal and newborn care is regarded as a sound programme for improving newborn survival (Guta et al., 2018). Mother and newborn access to and utilisation of quality antenatal and postnatal care are essential to save the lives of newborns (Khatri et al., 2016). The following challenges therefore need to be addressed to ensure effective coverage of newborn interventions in resource‐constrained settings: inadequate skills to prevent, identify and manage newborn complications; inadequate infrastructure; unfavourable working environments; inadequate supply of essential newborn commodities; ineffective clinical supervisors and a lack of mentorship for services providers (Khatri et al., 2016).

1.1. Background

An estimated 2.5 million newborns died in the first month of life in 2017 (approximately 7,000 babies per day), the majority being in the first week after birth (WHO, 2019). Of these, 38% occurred in South Asia and 41% in SSA, with 23% in West and Central Africa, and 18% in East and Southern Africa (World Health Organization, 2018a). The WHO estimates that 35% of all neonatal deaths are due to complications related to preterm birth, 24% to intrapartum events (e.g. birth asphyxia), 14% to sepsis or meningitis, and 11% to congenital anomalies (Hug et al., 2019). Regarding the high morbidity and mortality rates, the overall maternal mortality ratio in developing countries in 2015 was 239 per 100,000 live births and 12 per 100,000 live births in developed countries (World Health Organization, 2018b).

While SSA has achieved substantive progress in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality rates, they remain very high, with marked variations between countries. Many are not close to achieving their Sustainable Development Goal (SDGs) targets of less than 70 maternal mortalities per 100,000 live births, and less than 12 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births by 2030 (Hug et al., 2019). In Benin, the maternal mortality decreased from 576 to 335 per 100,000 live births between 1990 and 2013, while neonatal mortality rates declined from 108 to 64 deaths per 1,000 live births between 1990 and 2015 (Hodin et al., 2016). In Cameroon, maternal mortality rates fell from 728 to 596 per 100,000 live births between 1990 and 2015, while neonatal deaths decreased from 86 to 57 per 1000 live births (Hodin et al., 2016). In Rwanda, the maternal mortality rate decreased from 1300 to 290 per 100,000 live births between 1990 and 2015, while the neonatal mortality rate fell from 41 to 17 between 1990 and 2016 (Gurusamy & Janagaraj, 2018). However, South Africa's maternal mortality ratio increased from 150 to 269 per 100 000 live births between 1990 and 2015 (MDGs5 target was 38 per 100000), while the neonatal mortality rate was 14 per 1000 live births (MGDs 4 target was 7 per 1000), with the MDG targets having not been achieved (Mmusi‐Phetoe, 2016).

Most maternal deaths (99%) occur in developing countries, particularly among women living in rural areas and impoverished communities (World Health Organization, 2018a). The primary complications that account for nearly 75% of all maternal deaths are high blood pressure during pregnancy, severe bleeding (mainly after delivery), infection, complications from childbirth and unsafe abortions (Keskin et al., 2018). Furthermore, 25% of the deaths during pregnancy are caused by or associated with diseases such as acquired immunodeficiency syndromes (AIDS) and malaria (Keskin et al., 2018).

Following the establishment of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, the WHO recommended the use of CHWs to help improve access to and the quality of maternal and child health (MCH) services (WHO, 2017). CHWs are an essential cadre of healthcare workers in low‐income countries, where human resources for rural healthcare infrastructure are often limited (Maru et al., 2018). In Africa, CHWs have been involved, to varying extent, in delivering primary level maternal and newborn health (MNH) services for many years, mainly in the roles of surveillance, reporting births and deaths, home visits to pregnant women to encourage them to seek skilled antenatal and delivery care, as well as during postpartum periods to provide education and screening for illnesses (World Health Organization, 2017). However, the agenda promoted by the WHO in recent years is to integrate CHWs more thoroughly into national MNH programs, and to broaden and deepen their roles (World Health Organization, 2018b).

1.2. Aims

The aim of this review was to critically analyse the implementation and integration of maternal and newborn healthcare interventions into African health systems that include CHWs to reduce maternal and newborn death. The main review question is as follows: What is involved in the implementation and integration into health systems in Africa of maternal and newborn healthcare programs that are carried out by maternal CHWs during antenatal, delivery and postnatal care?

2. METHOD

2.1. Protocol and registration

Maternal and newborn healthcare program implementation and integration by maternal community health workers, Africa. An integrative review. This systematic review is based on a review protocol formulated as per the requirements of PROSPERO, which was submitted for a prospective international register of systematic reviews (Registration number ID: CRD42018108322; available at http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018108322 ).

2.2. Justification

As the systematic review was anticipated to include quantitative, qualitative and mixed‐method studies (Creswell, 2014), a data‐based convergent synthesis design was used, with the results being grouped into categories and trends (Creswell & Clark, 2011), which resulted in a common basis for analysis and synthesis (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The participant, intervention, context and outcome (PICO) framework was therefore used to guide the identification of relevant literature (Appendix S1) and define the type of information extracted (Smith et al., 2011).

The general criteria for inclusion of the literature were English language primary research studies conducted in Africa covering CHWs involved in MNH antenatal, delivery and postnatal care service delivery, with secondary data‐based studies being excluded. The review was restricted to studies published from 2012 to 2016, the earlier date ensuring the inclusion of those conducted when CHWs were becoming part of MNH care programs (i.e. from 2008/9). The rationale for using 2016 as a cut‐off date was that this would allow for the inclusion of studies conducted in the context of interventions oriented to achieving MDGs 4 and 5.

The following stages were adapted from Godfrey and Harrison (2015) and guided the systematic review: (1) develop a protocol; (2) state the review questions; (3) identify the criteria to select the literature; (4) detail a strategy to identify all relevant literature; (5) establish how the quality of primary studies could be assessed; (6) detail the data extraction; and (7) synthesis and summaries.

2.3. Participant, intervention, context and outcome criteria

Specific criteria were identified in terms of the participants, interventions, context and outcome (PICO) framework. The participants consisted of pregnant women, those with newborn infants, and whose husbands and other family members accompanied them to health facilities to access relevant services. It also included CHWs who were involved in delivering antenatal care (ANC), birth delivery, postnatal care (PNC) and neonatal services, as well as nurses and midwives, skilled birth attendants, medical doctors, gynaecologists and obstetricians. The exclusion criteria were studies including women who were not pregnant; those with infants older than 28 days, as well as family members, health professionals and community health workers not involved in MNH care services. Interventions referred to a substantive focus on maternal health and neonatal care services that involved community‐based services. Context criterion were community‐based services related to MNH care programs conducted in Africa, and Outcome referred to the interventions to improve MNH.

2.4. Information sources, search and study selection

The English databases searched were Academic Search Complete via Elton B. Stephens Co. (EBSCO) Host, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition. The following search terms were used: maternal, newborn, healthcare, program, implementation, integration, community health workers, Africa, systematic review and nurses/midwives. An iterative approach was used to locate additional published studies through Google Scholar, the last date searched being 8 September 2018. All articles searched were kept in EndNote referencing software, with duplicate articles being removed from the full downloaded list, which was then cross‐checked by reviewers independently when scanning the article titles. The study selection was guided by PICO and made by searching each included article to observe its title, abstract and full text, with a consensus of two reviewers being required for inclusion, a third reviewer resolving any disagreements.

2.5. Appraisal and synthesis

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the quality of each study (Hong et al., 2018), and the general principles recommended in the adapted Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) for reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence guidance checklist (Appendix S2) were used to present the findings (Moher et al., 2009). A critical appraisal was done according to the data extraction tool for the specific category of study designs: qualitative, quantitative non‐randomised, quantitative descriptive and mixed methods, and establishing if it served the study aim. In addition, all included studies were screened to establish whether there were clear research questions and the collected data allowed the research questions to be addressed in terms of ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘can't tell’, and ended with comments to discuss to determine whether the study could be included according to its quality (Appendix S3).

In synthesising the material, the data extracted from the included studies were analysed by noting patterns and themes, identifying plausibility, clustering, counting, making contrasts and comparisons, discerning common and unusual patterns, subsuming particulars into general, noting relationships between variability, finding intervening factors, and building a logical chain of evidence (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

2.6. Data collection process

The general types of data extracted were author, African country, purpose, study design with participants, settings, duration, and the pre‐intervention and intervention components (for antenatal, delivery and postnatal services). Specific types of intervention that were delineated in terms of whether or not the studies focused on ‘pre‐intervention’ (planning of interventions before its implementations), ‘interventions’ (implementation of interventions) or both were extracted (Table 1). The data collection was done in October and November 2018. The data that support the findings of this study are available in Table 1 of this study.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| No/More than one theme | Authors; Pub date; Country | Purpose | Study design, participant, setting and period | Process before interventions | Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal care (ANC) | |||||

| 1. PNC |

Ahumuza et al. (2016) Uganda |

To explore the challenges faced in providing antenatal/postnatal care services and HIV |

Qualitative approach, descriptive cross‐sectional qualitative. District health team members, healthcare providers and services users at 2 district hospitals (1 from each of the study districts) and 3 health centres level IV (1 in Kitakwi and 2 in Mubende). General hospital and level IV health centres in Kitakwi and Mubende Districts May to June 2014 |

Human resources Government, stakeholders and NGOs. Staffing levels to match the workload. Remuneration of health workers. Refresher or targeted training to address gaps as additional services are integrated. Community Participation Home visitation by the village health team. Coordination, leadership and advocacy. Effective communication. Infrastructure Structure Integration of ANC, PNC, HIV and FP requires: Infrastructure. Supplies Sufficient supplies such as HIV test kits, drugs and gloves. |

Record‐keeping and communication. Networks of quality from ANC to delivery service. Integrative HIV, ANC and PNC services: Too many papers to record, including ANC, PNC, FP, HIV and immunisation registers Physical examination. Weight‐taking for both mothers and newborns Pregnant women community education. Health prevention intervention. Contact HIV counselling and Screening tests pregnant. testing for mothers’ services. |

| 2. Delivery PNC |

Byrne et al. (2016) Kenya |

To better understand practice and perceptions of TBAs and SBAs providing maternal care in remote pastoralist community in Kenya |

Qualitative approach, descriptive qualitative study, Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). Communities semi‐nomadic 5 groups ranches in Laikipia (Chumvi, Morupusi, Makururia, Naibor and Tiamamut) and three in Samburu (Kirimon, Kisima and Longewan). Dispensaries, health centres and sub‐district hospitals October 2013 to March 2014. |

Infrastructure (ANC). Structure. Antenatal care interventions: Provide laboratory services at dispensary level Increase the integrated quality of PNC utilisation. Network of integrated quality PNC interventions from health facility to the community. Supplies. Delivery interventions: Provide partograph at dispensary level. Human resources. Access to Health facility in remote areas (Delivery). Skilled birth attendants. Increase the proportion of SBA‐assisted deliveries. Refer program and communication Refer obstetrical complications. Improve obstetrical outcome. Prevent mistreatment of women during facility‐based childbirth. |

Physical examination and Leopold's maneouvers. Skilled birth attendants. Antenatal care intervention: Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) provide a range of services for pregnant women including: Assessment of maternal weight, blood pressure, fundal height, foetal heart rate and foetal positioning; Record‐keeping communication Mothers issued with an antenatal record card, Health prevention intervention given iron–folic acid supplements and got immunisation of tetanus, and birth preparedness, expected delivery date is calculated. Screening tests pregnant Full check‐up of pregnant woman, comprise urinalysis, ultrasound, blood grouping, haemoglobin and HIV testing. Pregnant women community health education Qualified health providers teach the pregnant women to consume a balanced diet and sufficient meals; advise them to avoid the hard work, which could harm the baby. Improve the time spare and use mosquito net during night. Skilled birth attendants SBAs involving traditional birth attendants in antenatal care (remote areas). Delivery health facility in remotes areas: provide healthcare services delivered by SBA to women at time of delivery‐evaluate mother and baby; define the stage of labour and status of baby at health facilities, write the women's identification and previous history and keeping their records. Reassure pregnant women during the various stage of labour; persuade women to deliver in the lithotomy position. Partographs known, but are not accessible health facilities in remote areas. Network from health facility to house Postnatal care by qualified health providers: After birth, Qualified birth attendant usually examine the newborn; At the same time seen by her mother. Wash the mother. Normally, a woman after delivery should stay at health facility 24 hours. SBA performed the check‐up for mother and newborn before discharging; assess the women for postpartum bleeding, provide breastfeeding information, and advise her about family planning, clarify the vaginal tears care or episiotomy wound. The underweight mothers were given flour and beans to complement their daily diet. Visiting hour's schedule for family members limited, except there is a problem, in this situation the family is permitted more visits. Home visits and advocacy Some SBA organise CHWs to provide home visits for postpartum woman. |

| 3. |

Haddad et al. (2016) South Africa |

To explore the barriers encountered by women for ANC in an environment of changing healthcare policy To understand the barriers delaying early ANC in South Africa |

Mixed‐method approach, interview‐saturation, quantitative survey 21 women at prenatal care: black African females aged 21–39 years; 204 postpartum women aged 18–42 years. Phomolong clinic near Kalofong Hospital in Pretoria. November to December 2013. |

Community Participation Human resources Early attendance for antenatal care. Promote pregnancy‐planning options, including contraception. Improve maternal and newborn outcomes. Invest in adequate contraception education and implementation. Infrastructure Encourage the women to attend antenatal care services early. |

Pregnancy women community education. Counselling to improve early prenatal care attendance. Addressing cultural concerns and fears regarding pregnancy were imperative in promoting early attendance. Health prevention intervention. Early antenatal care intervention: HIV testing, psychological distress, protection benefits of ART, primary health care. |

| 4. |

Hagey et al. (2014) Rwanda |

Categorise barriers and solutions; affect timely initiation of ANC as perceived by health facility professional. |

Qualitative approach, interviews with facility professionals. Muhima Health Centre in Kigali Rwanda. June and July 2011. |

Community Participation Standardising health education and areas of education and sensitisation by health facility and community health workers. Facilitate in couple HIV testing to warrant pregnant women to attend antenatal care early. Infrastructure Structure and supplies Set a schedule for antenatal care services outside of health facility during normal working hours or give transport money for pregnant women coming from far away to decrease cost barriers. Make sure women are educated on the timing and structure of antenatal care before they become pregnant and providing right tracking of visits across health facility. |

Pregnancy women community education. Record‐keeping and communication. Maternal education and services focus on mothers who delivered their babies at home. Community‐based promotion program that would enhance awareness of pregnancy and PNC health services. |

| 5. | Kyei et al. (2012) Zambia |

To describe the level of ANC service provision. Assess various quality of care dimensions for ANC facilities in Zambia |

Quantitative approach; National surveys: Zambia 2005 Health Facility Census, Zambia 2007 Demographic and Health Survey. 4148 births used to describe the characteristics of antenatal care received by expectant mothers. 1299 antenatal facilities in 2015 Quality of antenatal care received by 4148 mothers between 2002 and 2007. |

Community Participation Evaluation level of ANC prerequisite; health censuses could be adapted for continuous monitoring and provide actionable data in selected community with reasonable period that is cheaper than survey (collecting data upstream at health facilities); good quality fulfilled the standard criteria of ANC offered to the pregnant women. Improvement should focus on the services offered during ANC services. Infrastructure Facilities and their accessibility, ANC for delivering effective interventions to improve maternal and newborn health. |

ANC function (ANC screening test): haemoglobin, syphilis, urine protein, urine sugar and blood group plus rhesus factors. Physical examination Interventions provide: Weight, height measurements, blood pressure, Health prevention intervention folate/iron supplementation, tetanus vaccination, Pregnant women community health education Antimalaria drug provided for IPT, blood sample taken to VCT analysis and prevent transmissions of HIV from mother to child, drugs for intestinal parasites, integrated VCT and PMTCT in ANC; WHO recommended four ANC visits, by skilled health workers. |

| Delivery | |||||

| 6. ANC |

Tomedi et al. (2015) Kenya |

To assess the effectiveness of traditional birth attendant (TBA) transfer program on increasing health facility delivery to be done by skilled birth attendants (SBAs) in rural Kenyan health facilities before and after the implementation of a free maternity care policy. |

Quantitative approach, non‐randomised controlled trial investigation. Women's exposure to TBA referrals and community education program, TBAs. Pregnant women receiving ANC; women who delivered at home compare with the percentages of ANC women who delivery at rural control facilities, before and after the transfer program was implemented, and before and after Kenyan government implemented a policy of free maternity care. Data from Ministry of Public health and Sanitation (MOPHSO) facilities archives were used to verify ANC visits and pregnant women who delivered at a rural health facility with or without a TBA. In selected rural areas in Kenya. The window period of study: from July 2011 to September 2013 with a Traditional Birth Attendant transfer intervention conducted from March to September 2013. |

Human resources. Community Participation (ANC). Access to health facility in remote areas. Skilled birth attendants. Increase the integrated quality of PNC utilisation. Qualified MCHWs. Multidisciplinary team (Government and Non‐government Organisations) to pay CHWs for community work Community participation (Family planning, preparedness, health insurance) |

Referral program and communication Community education program Referral program Free maternal halfway through the post intervention period. |

| 7. |

Molla et al. (2015) Ethiopia |

Explore the far‐reaching consequences of maternal deaths on families and newborns. Demonstrated the extensive impact of maternal mortality on newborns. Demonstrated the extensive impact of maternal mortality on orphaned newborns |

Qualitative approach, in‐depth qualitative interviews. Relatives of 28 women who dies from maternal causes. 13 stakeholders (government officials, civic society, and a UN agency) and 87 community members Butajiri and Marko districts Kabeles (villages) services by the Butajiri Rural health Program (Bati, Dirama, MisrakMeskan, Dobena and Butajiri town K04. August to October 2013 |

Human resources. Increase the integrated quality of PNC utilisation. Network of integrated quality of PNC interventions from health facility to the community. Critical evaluation among health and social welfare is needed. Call on ministries, NGOs, health facilities and community health facilities to improve quality to prevent maternal death in the first place. Combat maternal death, support community protection schedules to assist the vulnerable families in their households. Maternal mortality could be prevented by Infrastructure Structure and supplies availability of emergency obstetric and neonatal care, enhanced use of family planning methods and qualified birth attendance; Well equipped the health facility in remote areas; Refer program and communication improve mother's perception of health facility delivery. |

Network from health facility to house Effort targeting maternal mortality must address by availability of a skilled birth attendant and equipment needed to facilitate accessibility to care at the community, facility and policy levels; Home visit and advocacy standardising support system for families caring for vulnerable newborn; nutrition; access needed to health care; advocacy for newborns who lose their mothers; and access for maternal health. |

| 8. ANC |

Bensaid et al. (2016) Niger |

Verbal and Social Autopsy study measured 3 levels of determinants containing health system factors that affect access to and utilisation of curative and disease preventive and health promotive interventions and community (social) family (culture) and biological causes of deaths. |

Quantitative approach, Verbal and Social Autopsy (VSA) by Niger National Mortality survey (NNMS). 2012 to2013. National representative sample of 605 neonatal deaths (0–27 days) that occurred between 2007 and 2010. National level survey, Niger. |

Human resources Advocacy for support from global health community. Health data policy development and program planning. Skilled birth attendants Refer program and communication Evidence‐based decision‐making. Extended health promotion and diseases preventions. Increase to quality health care (Antenatal care, Skilled Birth Attendants). Access to the health facility in remote areas Reorienting and reorganising health and health services. Interventions for better quality care of pregnant women and delivery: maternal and newborn. |

Networks of quality from ANC to delivery care services Skilled birth attendants Qualified birth attendant interventions. Normal newborn care. Improved access to basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric and neonatal care. |

| 9. |

Oduro‐Mensah et al. (2013) Ghana |

To explore the how and why of care decision‐making by frontline providers of maternal and newborn services in the Greater Accra region, and to determine appropriate interventions required to maintain its quality and outcomes related maternal and neonatal. |

Mixed‐method approach, exploratory cross‐sectional and descriptive case study. Community health officers, public and community health nurses, midwives, medical assistants, doctors and district managers. Frontline health providers (doctors, clinical public and community health nurses and midwives) Great Accra region including the city Accra. July to December 2011 |

Skilled birth attendants Care decision‐making by specialist providers of maternal and newborn health services, tacit knowledge in pre‐services and in services. Training experience and skilled acquired on the job Evidence guidelines, protocols and tools, clients’ line, Qualified MCHWs Community leaders (ex‐pastors), Expert opinion, Peers ask opinions by phone calls and text message, face to face meeting and discussion. Access to the health facility in remote areas Infrastructure. Structure and supplies Accessibility of medicine staffs; provisions such as oxygen and equipment management issues; interpersonal and leadership relations among specialist and team of peers’ health group. |

Policymaking by specialist providers of maternal and newborn health services: Referral /emergency/complicated cases to support care decision‐making Communication between specialist providers, peers and experts can be facilitated by telephone. As everyone can be quickly reached to provide input into decision‐making. |

| 10 |

De Allegri et al. (2015) Burkina Faso |

To understand what made it possible households to overcome barriers and not others. |

Mixed‐method approach, quantitative household survey on decision to deliver at home. Qualitative in depth interviews to explore knowledge, and practice about labour and delivery. Women with a recent history of delivery, community leaders of villages. Noun Health Districts (NHD) north‐western Burkina Faso. 2011 |

Access to the health facility in remote areas Skilled birth attendants Political entrepreneur: Set a new policy for giving birth in health facilities. Relationship between the health providers and Qualified MCHWs Referral program and communication Community involved in shaping decision regarding delivery Abolish all fees for delivery. Structure and supplies Maternity wait home or transport vouchers (availability ambulance transport). Community participation |

Referral program and communication Decision to deliver at home vs in healthcare facility. Use fee reduction to help reduce the number of home deliveries. During ANC consultation insist on return to the facility to ensure a safe delivery Sensitisation campaign, referrals enable women to get the health facility in due time. |

| 11. ANC, PNC |

Ntambue et al. (2016) Democratic Republic of the Congo |

To assess the relationship between the MNCH package as currently implemented and perinatal mortality in Lubumbashi District, DRC |

Quantitative approach, prospective cohort study, Women who had delivered in one of the study facilities and had received various levels of ANC with women who had delivered in the same facilities but had not received ANC. 2823 pregnant women were recruited into the group; 5 (0.2%) women had miscarriage during follow‐up, 424 (15%) were not found even at home. At delivery, the remaining 2394 women were compared with those who had not attended ANC. All women included in the study followed until 50 days after delivery Lubumbashi health zone hospitals; urban and rural (health facilities, general reference hospitals, provincial reference hospital. health centre or private clinic urban and in a rural setting) October 2010 to February 2011 |

Access to the health facility in remote areas. Infrastructure. Structure and supplies. Availability of consumables materials, medicines and training of health workers, Availability of protocol for the management of complications in deliveries. |

Networks of quality from ANC to delivery service. Skilled birth attendants. Home visits and advocacy. Pregnant women community education Continuity—Antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care ANC screening and interventions Induction of labour (in case of intra uterine growth retardation) Glycaemia control intervention to reduce respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) Prenatal corticosteroid (cerebroventricular haemorrhage and neonatal death) Induction of labour (for pregnancies past 41 weeks of gestation) Aspiration of meconium Signal function intervention of EmONC: Emergency caesarean (delivery complications) Assisted vaginal delivery by ventouse (delivery complications) During delivery and postnatal period: Partogram for surveillance skilled birth attendance During neonatal period: Prevention of hyperthermia, management RDS, pneumonia, infection. |

| 12. ANC |

Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo (2013) Tanzania |

Improving access to and strengthening the health system to guarantee delivery skilled delivery by personnel, and bridging the gaps between communities and the formal health sector through community‐based counselling and health education, which is given by well informed and supervised maternal community health workers who inform community about maternal and newborn health care as well as prevention and promotive health services. |

Mixed‐method approach, retrospective and focus group discussions, participants’ observation and informal conversations. Women who had delivered in a health facility and at home women with support of a traditional birth attendant (TBA); in the past 2 months; TBAs& community members. Urban–rural similarities and differences, Masasi District, and Mtwara region August to November 2010 |

Access to the health facility in remote areas NGOs and government organisation collaboration: Establishing a cadre of Qualified MCHWs Community health worker on standard training and paid by the system. Formal health system in rural areas System for referral of mothers Psychosocial support, Community participation empowering teenagers, Skilled birth attendants. Infrastructure. Structure and supplies. Adequate workforce, well‐equipped health facilities Training in maternal and neonatal health (danger signs, clean delivery standards, HIV/AIDS) Shared responsibility (treatment free) |

Pregnant women community health education Referral program and communication Community‐based intervention. Sensitise and inform both women and men about maternal and newborn risks: why services are crucial Community‐based program Community‐based counselling and health education to inform villagers about promotive and preventive health services in general and related maternal and neonatal services in particular |

| Postnatal care (PNC) | |||||

| 13. ANC Delivery |

Wells et al. (2016) Ethiopia, Ghana and Nigeria |

Recognising the potential that Misoprostol could have reducing maternal mortality in these countries Advance distribution of misoprostol to pregnant women. |

Qualitative approach, 100 key informants and 216 focus group participants Women giving birth at home. Misoprostol was administered to only 351 of the 1251 women who delivered during the 5‐month project period.10 districts and 100 rural wards, West Gojjan and North Gondar, Administrative Zone of Amjara, Ethiopia June and November 2014 Challenges of using misoprostol at home (Ghana) through primary health clinics 2008 Pilot study in Nigeria (2009 to 2019) for pregnant women. |

Access to the health facility in remote areas supplies Increase in uterotonic coverage of home delivery. |

Referral program and communication. Record‐keeping and communication. Registration of pregnant women, noting their probably delivery date, and education about postpartum haemorrhage and misoprostol to pregnant women, community leaders and family members. All was done by youth mentors. Pregnant women were reminded to attend antenatal care services. Where they were receiving misoprostol and teach them how to use it for postpartum haemorrhage, safe delivery education and facility delivery advice (Ghana). Women access of misoprostol through the community agent (Nigeria). Extend the distribution of misoprostol directly to the women in advanced during ANC and at delivery, in Zaria communities. Distribution done by cadres of community‐based workers. |

| 14. Delivery |

Kante et al. (2015) Tanzania |

To determine the extent to which mothers with recent pregnancies received the WHO recommended PNC services at a health facility or at a community with a TBA or a village health worker (service utilisation rate). To identify individual characteristic and contextual factors associated with utilisation of PNC among mothers with recently pregnancies. |

Quantitative approach, cross‐sectional household survey 889 mothers who had completed a pregnancy within the two years preceding the survey Rural and semi‐urban: Rufigi, Kilombero and Ulanga District. May to July 2011 |

Increase the integrated quality of PNC utilisation Collaboration of Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Formulate policies and program to increase PNC utilisation rate. Advocacy: project cadre training CHWs. The trained CHWs to provide PNC care during routine home visits. Promote routine prevention care PNC. |

Referral program and communication. Network from health facility to house. Compliance with WHO recommended frequency of PNC services. Home visits and advocacy PNC visit at home. Provide PNC through the community‐based primary care. Pregnant women community health education Provide the quality of maternal health services (counselling and education) during postnatal period. |

| 15. ANC delivery |

Agho et al. (2016) Nigeria |

To determine population attributable risks (PARs) estimates for factors associated with non‐use of postnatal care (PNC) Nigeria |

Quantitative approach, recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS,2013) Interview 20467 mothers aged 15–49 years Generalised to the entire country 2013 |

Increase the integrated quality of postnatal care utilisation Government and stakeholders need to make maternal health services affordable to low‐income mothers. Implement community‐based newborn programs to focus on providing home‐based PNC services to mothers. Minimise inequitable access to pregnancy care. Skilled Birth attendants. Network of integrated quality of PNC interventions from health facility to the community. Delivery health care with trained healthcare personnel. Information via television, radio. Affordable to women, especially in rural areas. Home visits by professional health workers to ensure that those living in remote areas are not further disadvantaged. Involving community leaders including religious leaders in health program. |

Pregnant women community health education. Network from health facility to house. Home visits and advocacy. Maternal education and services focus on mothers who delivered their babies at home Community‐based promotion program that would enhance awareness of pregnancy and PNC health services. |

| 16. |

Tesfahum et al. (2014) Ethiopia |

Decreasing maternal and child mortality |

Mixed‐method approach, quantitative and community based, cross‐sectional qualitative study 15–49‐year‐old mothers who gave birth during the last year, 3 FGDs: 16 mothers, 3 HEWs, and 3 CHWs participants Gondar Zuria District April to August 2011 |

Increase the integrated quality of PNC utilisation Information on when postnatal services are offered and for whom. Government could strengthen the health system to provide quality postnatal care. Using skilled birth attendance at birth; emergency obstetrical care through a functional referral system All levels of health system from health post to referral hospitals have a team of skilled health workers and emergency obstetrical care services. |

Network from health facility to house. Immunisation, family planning, counselling on PNC, counselling on breastfeeding and physical examination are known by mothers as interventions during PNC Home visits and advocacy HEWs and Community health agent informed the mothers about existence of PNC services. |

| 17. |

Hill et al. (2015) Ghana |

To explore women's knowledge of what happens to the baby after delivery. Women's understanding of terms and question phrasing related to postnatal care, and problems with recall periods. |

Qualitative approach, qualitative interviews and groups discussions, saturation sampling. Mothers and Health workers in rural Ghana: three districts in the Brong Ahafo region of Ghana. Over 2 months period in 2010. |

Increase the integrated quality of PNC utilisation. Network of integrated quality of PNC interventions from Health facility to the community. Ensure that check in delivery is considered PNC. Service providers to provide explanation and communication to the mothers during interventions being delivered. |

Network from health facility to house. Home visits and advocacy. Mothers: Bleeding surveillance, temperature, blood pressure cuff, test blood, urine and faeces. Newborn: birth weight, cord check, unwrapping the baby. Both postnatal visits by community health workers. |

3. RESULTS

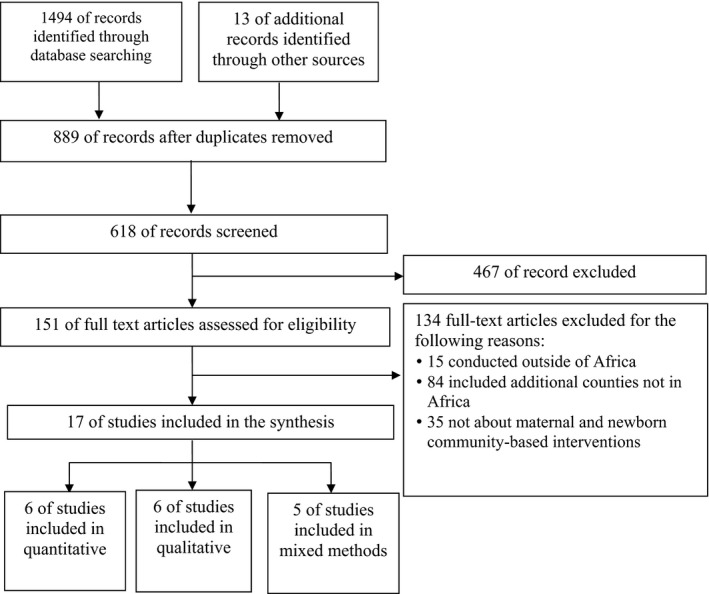

3.1. Study selection

The initial identification through the database search yielded 1494 abstracts, which were reduced to 605 after removing 889 duplicates, and increased to 618 after including 13 records identified through other sources. Of the 618 abstracts, 457 were excluded, as they did not address MNH care program interventions. The full text of the remaining 151 articles was assessed for eligibility, of which 134 were excluded as they were performed outside Africa, in one or two countries in Africa combined with other countries from other continents, or were not about maternal and newborn community‐based interventions. The remaining 17 studies were included in the synthesis, of which six were quantitative, six were qualitative and five were mixed methods (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study selection: PRISMA flow diagram adapted from: (Moher et al., 2009)

3.2. Study characteristics

The 17 studies were conducted in 12 countries in Africa, these being grouped as following: one conducted in three countries (Ethiopia, Ghana and Nigeria)(Wells et al., 2016), two in Ethiopia (Molla et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014), two in Ghana (Hill et al., 2015; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013) and one in Nigeria (Agho et al., 2016). Two were conducted in Kenya (Byrne et al., 2016; Tomedi et al., 2015), two in Tanzania (Kanté et al., 2015; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013) and one each in Burkina‐Faso (De Allegri et al., 2015), DRC/Congo (Ntambue et al., 2016), Niger (Bensaïd et al., 2016), Rwanda (Hagey et al., 2014), South Africa (Haddad et al., 2016), Uganda (Ahumuza et al., 2016) and Zambia (Kyei et al., 2012) (Table 1). As indicated in Table S3, the appraisal of the 17 studies confirmed that they could all be used in the review, as the methods sections provided sufficient detail to extract the type of information required to effectively use the MMAT tool.

3.3. Ethical clearance

As this is a review, ethical approval was not required.

3.4. Results synthesising

In the Africa context, the three themes of care identified for inclusion in this review were antenatal care, delivery care and postnatal care interventions requiring planning before implementation.

3.4.1. Antenatal care interventions

The 34 findings on planning antenatal care interventions were placed under three categories, while their implementation had 38 findings that were grouped into seven categories.

Planning antenatal care interventions

There were 34 findings on planning antenatal care interventions that were placed under three categories: 1) human resources, 2) infrastructure and 3) community participation. The review highlighted the scale and depth of 1) human resource planning required in the design of MNH programs, particularly with regard to antenatal care interventions. Firstly, it indicated the necessary involvement of a wide range of stakeholders in conceiving and planning MNH programmes that incorporate CHWs. Stakeholders included international health agencies and funders, government ministries (e.g. health, social welfare), as well as international and local non‐government organisations (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012).

The findings showed that in the general hospitals and level IV health centres in Kitakwi and Mubende Districts (Uganda), there was a need for staffing levels to match the workload. During ANC services, some mothers missed laboratory investigations and therefore did not received the expected interventions. Some health facilities were supported by volunteers who provided HIV counselling and testing services, this being facilitated by Baylor in Uganda, but experienced nurse shortages to perform routine activities (Ahumuza et al., 2016). In Kenya, the health system provided skilled birth attendants (SBAs) in semi‐nomadic pastoralist communities, at dispensaries, health centres and sub‐district hospitals for maternal health. Mothers were encouraged to attend SBAs and discouraged from making use of Traditional Birth Attendant (TBAs) who are lay community members. Mothers’ use of TBAs remains higher than SBAs in remote areas that have few health facilities and where mobile populations have limited access to static health services (Byrne et al., 2016). TBAs were too far away from health centres to improve the transfer of mother to the SBAs in rural Kenyan health facilities both before and after the implementation of a free maternity care policy in 2013 (Tomedi et al., 2015). The finding showed that at Phomolong clinic near Kalafong Hospital in peri‐urban Pretoria (South Africa), pregnant women delayed their attendance of ANC visits until late in their pregnancy, making intervention planning difficult (Haddad et al., 2016).

In Rwanda, there was a need for health facility staff and CHWs to work together to improve compliance of ANC attendance (Hagey et al., 2014). Regarding ANC facilities in Zambia, ongoing monitoring and quality services were offered in some community (Kyei et al., 2012), highlighting the need for appropriate estimations of staff workloads and facilities requirements in different locations. To provide optimal services, the health systems required multidisciplinary teams, clearly delineated responsibilities, accountability of both professional and CHWs, and appropriate training for all staff (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Kanté et al., 2015; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015).

In addition to the human resources, the review findings drew attention to the importance of physical planning to determine 2) what infrastructure would be required to facilitate the sound provision of antenatal care services (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016). Studies drew attention to taking into account the accessibility of health facilities for the populations they are supposed to serve (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012). Some authors highlighted the importance of procurement planning, for example, estimating medicinal supplies and HIV test kits (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Molla et al., 2015; Ntambue et al., 2016; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013).

The review findings recorded the need for considering 3) community participation during the planning stages regarding how people could be served, such as by home visits from nurses and/or MCHWs outside normal working hours, and standardised preventive health education campaigns in towns and villages. They also reported on the mechanisms needed to ensure that people obtain the necessary services, for example, pregnant women using health cards to track their visits to health facilities and agreements to adhere to scheduled visits to facilities (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012).

Implementing antenatal care interventions

There were 38 findings for implementing integrating quality antenatal care (ANC) interventions that were grouped as follows: 1) pregnant women community health education, 2) screening tests, 3) pregnant physical examination, 4) Leopold's manoeuvres, 5) health prevention, 6) record‐keeping and 7) communication.

The findings highlighted the need in some countries for 1) pregnant women community health education to implement antenatal care interventions by discussing counselling and education sessions to increase their awareness. These are generally implemented by CHWs and qualified health providers in communities and health facilities. In Nigeria, the community‐based newborn programs focus on mothers who deliver their babies at home and minimising inequitable access to pregnancy care (Agho et al., 2016). In Rwanda, CHWs promote the uptake of pregnancy health service programs (Hagey et al., 2014). In Tanzania, CHWs are provided with standard training maternal and are paid by the health system, their role being to sensitise and inform both women and men about why services are important, and to provide community‐based programs and counselling. They also provide health education to inform villagers about promotive and preventive health services in general, and related maternal and neonatal services in particular (Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013). In Tanzania, the trained CHWs conduct routine home visits to improve the quality of maternal health services (Kanté et al., 2015). In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), health workers inform inhabitants about the continuity of care services available, these being antenatal, perinatal and postnatal care, ANC screening and interventions (Ntambue et al., 2016). In South Africa, the findings showed that there is a need for early attendance by pregnant women for antenatal care to identify problems and provide appropriate advice (Haddad et al., 2016).

In Tanzania, pregnant women health education focused on community‐based interventions for sensitising and informing villagers about maternal and newborn risks as well as essential related services for both men and women (Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013). The review focused on contact HIV counselling and psychological distress for pregnant women and their families (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014). In Kenya and Zambia, pregnant women are advised to consume a balanced healthy diet, avoid hard work that could harm the baby, increase their leisure time and use mosquito nets at night (Byrne et al., 2016; Kyei et al., 2012).

The review findings showed that 2) screening tests for pregnant women are a part of implementing an ANC intervention comprehensive package, with tests needing to be accessible at all levels of the health system and affordable. Pregnant women cannot always afford the complete analysis package, such as haemoglobin, blood grouping plus Rhesus factor and HIV testing, nor can they afford urinalysis, urine protein, urine sugar, syphilis and ultrasound tests (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012). The review showed that in some countries, the screening tests were not done to mothers due to a shortage of staffs, critical supplies, such as HIV tests kits, drugs and gloves (Ahumuza et al., 2016).

The review findings emphasised the need for a comprehensive package that consisted of 3) a pregnant physical examination and 4) Leopold's manoeuvres, which is a part of ANC interventions, with examinations such as weight, height and blood pressure (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Kyei et al., 2012). Leopold's manoeuvre is conducted to assess the foetal position, heart rate and fundal height, these being beneficial interventions for pregnant women (Byrne et al., 2016). However, some countries offered inadequate ANC services, with insufficient staff and resources being provided to attend to and educate the women on how to appropriately care for themselves and the baby both before and after the birth (Kyei et al., 2012).

The review indicated that 5) health prevention interventions are a part of ANC services required by pregnant women, and include folate/iron supplementation, tetanus vaccinations and general primary health care (Byrne et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Kyei et al., 2012). Intermittent Preventive Treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) of malaria and drugs for intestinal parasites were also part of some antenatal interventions (Kyei et al., 2012). All countries included in this study provided integrated HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) and prevention of mother‐to‐child transmission (PMTCT) advocacy for HIV, and promoted the protective benefits of antiretroviral therapy (ART) when necessary (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Kyei et al., 2012).

The review findings reported on the important of 6) record‐keeping and 7) communication in ANC intervention implementations. It highlighted the need to accept proof of the husband's information brought by a pregnant woman to be able to register for the first consultation. This prevents problems that arise when the husband is not available to accompany a women to a health facility (Rwanda) to be registered and attend consultations (Hagey et al., 2014). The study highlighted the need for registers to record interventions, HIV testing and immunisation of pregnant women in Uganda (Ahumuza et al., 2016). Some interventions entail pregnant women being reminded to attend antenatal care services (Wells et al., 2016) and complete the visits, as recommended by the WHO (Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012). Birth planning included preparedness done by SBA and CHWs in collaboration with the mothers, who are given a record card to complete the birth plan (Byrne et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012).

3.4.2. Delivery care interventions

The 25 findings on planning delivery care interventions were divided into seven categories: 1) access to a health facility in remote areas, 2) skilled birth attendants, 3) qualified maternal community health workers, 4) structure, 5) supplies, 6) referral program and 7) communication. The 25 findings on implementing delivery care intervention were grouped as follows: 1) network of quality care intervention from antenatal care to the delivery service, 2) skilled birth attendants, 3) referral program and 4) communication.

Planning delivery care interventions

The review findings highlighted that 1) access to health facilities in remote areas required planning, especially regarding the delivery of care interventions to facilitate access to services, such as the formal health system in rural areas, health facilities and maternity waiting homes. Delivery care interventions need to be planned to ensure the availability of staff, medicine and oxygen for improving health systems, and that deliveries are performed by skilled personnel in remote areas (Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; De Allegri et al., 2015; Ntambue et al., 2016; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2016).

The review showed that the Niger health system needs to reorientate and reorganise its health services, and that interventions are required to ensure good quality care of pregnant women and newborns, the challenges being home deliveries that occur due to transport problems and distances to the formal services (Bensaïd et al., 2016). The findings revealed that in Kenya, to improve access in remote areas, the health system needs to increase the number of SBA‐assisted deliveries and prevent the mistreatment of women during facility‐based childbirth (Byrne et al., 2016). In Burkina‐Faso, a new policy was developed for giving birth in health facilities, which included making provision for addressing the relationship between the health provider and community in shaping decision regarding delivery, as well as eliminated fees for delivery (De Allegri et al., 2015). The review showed that in the DRC, there was a need in remote areas for a protocol to manage complications that arose during deliveries (Ntambue et al., 2016).

In remote areas in Ghana, access at health facilities is need to specialist and various member of the health team (Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013). The review showed that for access in remote areas in Tanzania, there was a need for NGOs and government organisation to collaborate to establish a cadre of community health worker who was trained on standard maternals and paid by the public health system (Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013). In Kenya, a review highlighted the need for various roll players (government and non‐government organisations) to pay CHWs for community work to facilitate health facility access (Tomedi et al., 2015). In remote Nigerian areas, the trained youth mentors distributed uterotonic to the women who delivered at home and refer them to health facilities (Wells et al., 2016).

In Burkina‐Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria and Tanzania, the health systems reviews focused on evidence‐based decision‐making, such as the appropriate number of 2) skilled birth attendants to assist deliveries, according to the number of mothers in the catchment areas and the integration of services (Agho et al., 2016; Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; De Allegri et al., 2015; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015). Their health system needs to plan the use of CHWs and implement community‐based newborn programs to focus on providing home‐based PNC services to mothers (Agho et al., 2016). It also needs support and advocacy from the global health community (Bensaïd et al., 2016) to understand the perceptions and practice of TBAs and SBAs who provide maternal care in remote pastoralist community to enable it to improve the transfer of mothers to formal health services, and provide them with free maternity care (Byrne et al., 2016; Tomedi et al., 2015). The review highlighted the desire of community leaders to be invited to participate in decisions regarding delivery and the need to eliminate fees (De Allegri et al., 2015).

Health systems in Ghana use community leaders (e.g. ex‐pastors) to convince mothers regarding referral decisions (Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013). Health systems bridge the gaps between communities and the formal health sector by providing community‐based counselling and health education. This is given by well informed and supervised maternal community health workers who inform them about maternal and newborn health care as well as the available prevention and promotive health services (Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013). The review findings reported the need to have 3) qualified MCHWs with recognised, standardised qualifications who were remunerated by the health system for working in the MNH care program (Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015). It was reported that managing interpersonal relationships among staff and providing leadership for communities are important for shaping decisions regarding service delivery (De Allegri et al., 2015; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015).

The review findings focused on the 4) structure (buildings) and 5) supplies required while planning delivery interventions. The following items were cited as needing to be available: materials, medicines and equipment, guidelines, protocols and tools, and as well as partographs to manage delivery interventions. The review highlighted the need for suitable structures (buildings) and supplies at all levels of the health system, such as at dispensaries and health facility in remote areas (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Molla et al., 2015; Ntambue et al., 2016; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013).

An important issue in planning the implementation of delivery care services was the need for the MNH care programs to accommodate local community conditions, such as the high number of home births, and the cost constraints for women to get to health facilities in time before delivering. This accommodation includes the uterotonic coverage of home delivery by community health workers (Wells et al., 2016); adequate ambulance transport (or provision of money to pregnant women for transport to health facilities), and maternity ‘wait for homes/shelters’ adjacent to health facilities (De Allegri et al., 2015; Hagey et al., 2014). The review reported the need for the adequate availability of emergency obstetrical and neonatal care, as well as family planning methods to prevent unwanted pregnancies and allow the women to control the spacing of their pregnancies (Molla et al., 2015).

The review emphasised the need to plan 6) referral programs and ensure 7) communication for delivery, and to improve the mother's perception of health facility deliveries during sensitisation of maternity care, which will improve referral during obstetrical complications and the outcomes (Molla et al., 2015). Political decision‐makers are responsible for setting the communication policies and train health workers, providing career development opportunities, ensuring effective decisions by frontline providers, encouraging women to give birth in health facilities, offering extensive health promotion disease prevention advice and quality health care (Bensaïd et al., 2016; De Allegri et al., 2015).

Implementing delivery care interventions

The review findings highlighted the importance of the link between the various services that are offered, such as 1) the network of quality care interventions, from antenatal to delivery care services. The networks of quality care interventions at ANC services included aspects such as screening and physical examination (Leopold's manoeuvre) reports (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Bensaïd et al., 2016; Ntambue et al., 2016), sensitising mothers to the importance of returning to the facility to ensure a safe delivery, and the need for prenatal corticosteroids intervention on foetal maturity, which was revealed during ANC services (De Allegri et al., 2015; Ntambue et al., 2016).

The review reported on 2) skilled birth attendants during the implementation of delivery care interventions, with women in labour who presented at the health facility being received by qualified birth attendants who evaluate mother and baby, identified the stage of labour and status of the baby, and record the women's demographic details and history of previous births. Skilled birth attendants also saw it as part of their responsibilities to be with the mother during labour and delivery. A common emphasis in the findings was the need for MNH care programs to ensure the availability of qualified birth attendants and to persuade women to deliver in the lithotomy position (Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Ntambue et al., 2016). The review also reported on surveillance done by SBA using partograph during labour who were able to use and interpret the results (Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Ntambue et al., 2016). The studies reported on the induction of labour in cases of intrauterine growth retardation for pregnancies past 41 weeks of gestation and on the aspiration of meconium. They also outlined delivery complications, such as emergency caesarean, assisted vaginal delivery by ventouse, and signal function of Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care (EmONC) with high impact interventions (Ntambue et al., 2016).

The findings indicated the importance of 3) referral program and 4) communication for delivery implementation, with the CHWs referring pregnant women to health facility for delivery, or any complications, and distributing misoprostol during home births (De Allegri et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2016). Community education programs were reviewed, as well as sensitising and informing both women and men about the maternal and neonatal health program, including the preventive and promotive health services. The community education programs enable pregnant women to attend health facilities at the right time (De Allegri et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2016). The review reported on frontline providers using phone communication to access more specialised care decisions at higher levels of care related to maternal newborn health services (De Allegri et al., 2015). It highlighted the need for delivery care to be provided by qualified birth attendants who were competent and could take decision at the right time based on the EmONC signal functions (Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Ntambue et al., 2016).

3.4.3. Postnatal care interventions

Regarding planning postnatal care interventions, the 15 findings were divided into two categories: 1) increasing the quality of PNC utilisation and 2) networks of PNC services from health facility to the community. The implementation postnatal care interventions had 14 findings that were grouped in three categories: 1) integrated quality of PNC interventions, 2) integrated quality of PNC home visits and 3) advocacy.

Planning postnatal care interventions

Regarding 1) increasing the quality of PNC utilisation, the review studies emphasised planning the development of policy guidelines and program utilisation, and indicated the need for programs to strengthen the health system and provide skilled birth attendants for such services (Agho et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Molla et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014; Tomedi et al., 2015). The emphasis was also on training community health workers, providing information about when clinical services are offered and for whom, and involving community leaders, including religious elders (Agho et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014; Tomedi et al., 2015). The findings reported that to increase the quality of PNC utilisation requires addressing the inequitable access for pregnant women. In addition, the inclusion of services, such as EmONC packages, was highlighted, and the need for respectful maternity care in remote areas (Agho et al., 2016; Molla et al., 2015).

Likewise, 2) networks of PNC services from the health facility to the community were reported in planning postnatal care interventions, with the review findings indicating that plans should consider check‐ups for mothers and newborns shortly after delivery as part of postnatal care services (Hill et al., 2015). The network/continuum of interventions from health facility to home‐visits services for both mothers and newborns are provided by trained CHWs and health professionals (Agho et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016). Some authors advices the increased use of contraceptive methods to avoid maternal mortality as being the part of planning for PNC interventions (Molla et al., 2015).

3.4.4. Implementing postnatal care interventions

The 14 postnatal care interventions were grouped into three categories: 1) integrated quality PNC interventions, 2) integrated quality of PNC home visits and 3) advocacy. The review findings indicated that there needs to be a network of 1) integrated quality PNC interventions from health facility to the households. The studies reported on interventions for both mothers and newborns, where the services start with delivery at the health facility and continue to the households (Agho et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Molla et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014). The review highlighted that at the time of birth, the newborn should be examined for cord check and unwrapping, shown to the mother and weighed. Measures to manage Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) and prevent pneumonia, infections and hyperthermia/hypothermia are essential (Byrne et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2015). Similarly, it is noted that at the time of birth, the mother should receive the following care procedures: a physical examination, monitor for bleeding, how to care for episiotomy wounds or vaginal tears, breastfeeding advice, taking a temperature, blood pressure, and testing of blood, urine and faeces (Byrne et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014).

The review underlined that family planning counselling should be provided, and a discussion had about the need for scheduled family visits for both mother and newborn at health facilities and the importance of check‐ups before discharge, with a focus on immunisation for newborns (Byrne et al., 2016; Tesfahun et al., 2014). Studies highlighted the need for mothers to be included in the services, and for their improved awareness of the existence of pregnancy services resulting in those who access them benefiting from the continuum of services between ANC, delivery and PNC (Agho et al., 2016; Kanté et al., 2015).

The review findings reported on the 2) integrated quality of PNC home visits and 3) advocacy as part of PNC implementation, which included routine visits, counselling and education for mothers who delivered their babies at home on the desired frequency and compliance required for the recommended services (Agho et al., 2016; Kanté et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014). The continuity of services and home visits in the community were highlighted, with the findings indicating that these must be performed by trained CHWs in collaboration with SBAs (Agho et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Hill et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Ntambue et al., 2016; Tesfahun et al., 2014). The review findings reported that during such visits, discussions need to be held on nutrition advice for the mothers, with advice, advocacy and support being essential for underweight mothers and families caring for vulnerable newborns (who have lost their mother) (Byrne et al., 2016; Molla et al., 2015; Tesfahun et al., 2014).

4. DISCUSSION

This review analysed the implementation and integration into healthcare systems of maternal and newborn healthcare interventions in Africa that include community health workers to reduce maternal and newborn deaths. Three themes related to interventions were explored, the first being antenatal care interventions, which are essential to reduce maternal and newborn mortality. In 10 countries (Burkina‐Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia), the health systems indicated the importance of community‐based maternal and newborn healthcare interventions to reduce their mortality and morbidity (Agho et al., 2016; Ahumuza et al., 2016; De Allegri et al., 2015; Haddad et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kyei et al., 2012; Molla et al., 2015; Oduro‐Mensah et al., 2013; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2016). This requires national governments, as well as national and international partners, to adopt a new approach by supporting a skills mix, and connecting the potential of both CHWs and health facility staff in inter‐professional primary healthcare teams (WHO, 2018). The authors in Ethiopia, Kenya, Niger and Uganda indicated that when planning ANC services, before any implementation, there needs to be provision for sufficient and adequately qualified human resources, such as SBAs and trained maternal CHWs in remote areas (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Molla et al., 2015; Tomedi et al., 2015).

The findings indicate the need to support health systems in Africa by ensuring the appropriate distributing of sufficient staff in maternal and newborn health care (Murphy et al., 2015). Studies from Burkina‐Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia also indicated the need for appropriate infrastructures, including health facility building that are well equipped and resourced, with sufficient supplies and accessible services. ANC interventions require continuous monitoring and evaluation (Kyei et al., 2012) as well as community participation to ensure that an appropriate quality of integrated services is offered, as indicated in six countries (Kenya, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia) (Ahumuza et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; Haddad et al., 2016; Hagey et al., 2014; Kanté et al., 2015; Kyei et al., 2012; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013). These findings are supported by Moller et al., (2017), who highlighted that efforts should be made to collect and report on the coverage of early ANC visits for ongoing monitoring and evaluation. Health outcomes of pregnancy‐related indicators were reported to differ according to the regions in which the women lived (Kwak et al., 2019).

Well‐planned, integrated ANC services will ensure that their implementation provides a comprehensive package that meets the needs of the people they are designed to serve. The interventions where pregnant women are provided with community health education, screening tests, pregnant physical examination, Leopold's manoeuvres, health prevention, record‐keeping and communication (Burkina‐Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia) are presented in Table 1. Comprehensive ANC interventions should be accessible in rural areas and need to be standardised across countries, as should the responsibilities of SBAs and trained CHWs, to ensure minimum standards of care. The lack of access to services in rural areas was evidenced by mothers who did not take advantage of the available interventions, which means missing the chance to achieve a better pregnancy outcome (Hodgins & D'Agostino, 2014).

Comprehensive ANC packages could be achieved in Africa, with support being required from stakeholders that include international health agencies and funders, government ministries (e.g. health, social welfare) advocacy groups, as well as international and local non‐government organisations (Agho et al., 2016; Ahumuza et al., 2016; Bensaïd et al., 2016; De Allegri et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Molla et al., 2015; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tesfahun et al., 2014; Tomedi et al., 2015). This is similar to the WHO recommendation that in rural areas with low access to health services, community mobilisation, household and antenatal home visit interventions are recommended to increase ANC utilisation and improve perinatal health outcomes (WHO, 2018). The suggestion is that ANC interventions must be well planning before implementation to enable mothers to benefit from the full package when attending the services at health facilities, the findings showing that some interventions are not provided during this time (Shibanuma et al., 2018).

The second theme was delivery care interventions, which requires a network of ANC services. The level of planning of ANC interventions and their implementation influence the offer of the intended services (De Allegri et al., 2015). During ANC consultations, the staff need to insist that the women returns to the facility to ensure a safe delivery, with the required continuity of antenatal care to delivery often not being followed by mothers (Shibanuma et al., 2018). Furthermore, implementing delivery care interventions need regular communication between MCHWs and the women during their pregnancies, as well as with their family members, particularly their husbands, for effective service delivery (Takahashi et al., 2017). Communication also needs to take place between MCHWs and professional health facility staffs, this being an essential platform for effective referral mechanisms (Bensaïd et al., 2016; Byrne et al., 2016; De Allegri et al., 2015; Kanté et al., 2015; Molla et al., 2015; Pfeiffer & Mwaipopo, 2013; Tomedi et al., 2015; Wells et al., 2016). This was highlighted in a study by Bhutta (2017), which indicated the need to reduce healthcare inequalities and reach marginalised populations to improve maternal and neonatal survival and wellbeing.

The third theme related to PNC interventions that increase service utilisation, their planning requiring a continuum of services, from integrated quality ANC to delivery care at health facilities. Integrating PNC interventions also require a network of services, from the health facility to the household and home visits, as well as advocacy. PNC implementation needs to start at the health facility shortly after delivery and continue at home thereafter, with services being required by health professionals and trained CHWs for both mothers and newborns. It is essential to maintain home visits to follow‐up the mothers and newborns living in remote areas to ensure that they are not disadvantaged (Guenther et al., 2019). This needs to be done with the collaboration of CHWs, community leaders, including religious leaders, who need to be involved in maternal and newborn healthcare programs (Agho et al., 2016).