Summary:

In the wake of the death toll resulting from coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19), in addition to the economic turmoil and strain on our health care systems, plastic surgeons are taking a hard look at their role in crisis preparedness and how they can contribute to crisis response policies in their own health care teams. Leaders in the specialty are charged with developing new clinical policies, identifying weaknesses in crisis preparation, and ensuring survival of private practices that face untenable financial challenges. It is critical that plastic surgery builds on the lessons learned over the past tumultuous year to emerge stronger and more prepared for subsequent waves of COVID-19. In addition, this global health crisis presents a timely opportunity to reexamine how plastic surgeons can display effective leadership during times of uncertainty and stress. Some may choose to emulate the traits and policies of leaders who are navigating the COVID-19 crisis effectively. Specifically, the national leaders who offer empathy, transparent communication, and decisive action have maintained high public approval throughout the COVID-19 crisis, while aggressively controlling viral spread. Crises are an inevitable aspect of modern society and medicine. Plastic surgeons can learn from this pandemic to better prepare for future turmoil.

CRISIS: HERE TO STAY

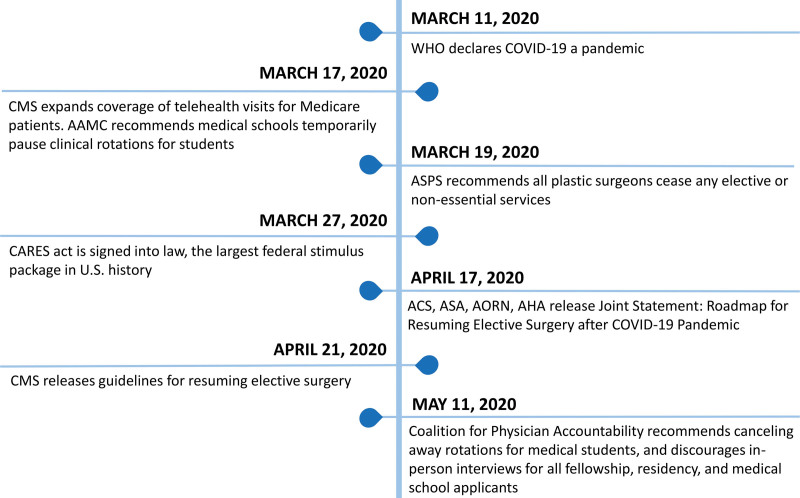

In a matter of weeks, coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) swept across the United States and disrupted nearly every aspect of health care delivery.1 By the time the virus received its official name, SARS-CoV-2, on February 11, 2020,2 community spread in the United States was well underway.3 By March 18, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services declared that all nonemergent surgical, medical, and dental procedures should be suspended until further notice; the American Society of Plastic Surgeons issued similar recommendations the following day (Fig. 1).4 Amid shortages of personal protective equipment and unclear COVID-19 testing guidelines, health care leaders grappled with the transition to telemedicine and the transformation of operating rooms into intensive care beds.5 With evidence pointing toward subsequent waves of the illness in the coming months,6 it is clear that the COVID-19 crisis will continue to bring new challenges that test the strength of leaders across all medical disciplines.

Fig. 1.

Timeline of COVID-19 events relevant to plastic surgeons. WHO, World Health Organization; AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; ASPS, American Society of Plastic Surgeons; CARES, Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act; ACS, American College of Surgeons; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; AORN, American Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses; AHA, American Hospital Association.

As the pandemic unfolds, industries and organizations find themselves scrambling to mitigate economic losses, adopt new business models, and protect employee safety.7 These challenges are particularly evident in the field of plastic surgery, where private practices are experiencing financial hardship and logistical challenges.8 After nonemergent case volume plummeted in March, the resulting economic losses left private practice surgeons in a dilemma; they could furlough valued team members or face unsustainable overhead costs.8 Some plastic surgeons have compared this bleak climate to that seen in the 2008 economic recession. Others fear it may be worse, given the added component of medical supply shortages, the increased cost of protective equipment, and a more immediate drop in revenue.9 There is further concern about the unprecedented backlog of nonemergent surgical procedures that were postponed following the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recommendations.5,9 With restrictions slowly lifting, plastic surgery leaders have the responsibility to develop more robust surge capacity protocols in anticipation of future waves of COVID-19. Ethical considerations are necessary not only to determine which patients should receive care first, but also to weigh the risks and benefits of potential COVID-19 exposure in the clinical setting.5 In addition, new protocols must be developed to guide surgeons on how and when to safely deescalate these surge capacity measures.5 As leaders in health care, plastic surgeons are certainly being put to the test.

Despite the tragedy and turmoil, the COVID-19 pandemic presents opportunities for growth and reflection. This is a wake-up call for leaders of all backgrounds not only to reexamine their ability to prepare for and respond to crisis, but also to accept crisis as an unavoidable aspect of society. Effective leadership will be a critical determinant in curtailing the damage, disruption, and loss of life across the world. This will place an even greater spotlight on those leaders who have what it takes to mitigate the many downstream consequences of COVID-19. Therefore, we compiled this article to review the central challenges that leaders face during crisis. We also discuss effective leadership traits and examine the connection between leadership style and crisis outcome by drawing on real-world examples. We wish to impart relevant and engaging leadership principles that facilitate crisis management across plastic surgery subspecialties and practice settings.

LEADERSHIP PRINCIPLES FOR EFFECTIVE CRISIS RESPONSE

A crisis creates a series of conditions that test the limits of teams and organizations, often forcing leaders to reexamine their core values.10 The word “crisis” broadly describes a low-probability event that has high potential for serious consequences.11 Crises are time-sensitive, and as the clock ticks, the window to achieve a successful outcome closes. To make matters more challenging, the unexpected and often unprecedented nature of a crisis means that reliable information to assist decision-making is scarce.11 Leaders must grapple with uncertainty surrounding the cause and the solution to the crisis. Considered together, these elements create a tumultuous storm through which leaders must navigate.

To lead effectively during a crisis, it is beneficial to examine how a crisis impacts team dynamics.12 Given the high degree of uncertainty surrounding a crisis, leaders may feel that they are losing control. Therefore, some may reflexively overcompensate for this loss and attempt to control as many facets of the team as possible.12 However, this overreliance on centralizing decisions and tasks, instead of delegating, can produce massive inefficiencies in crisis response.13 Simply put, micromanaging may restore the leader’s sense of control at the expense of the team’s efficiency, which delays implementation of effective strategies. Leaders may also be tempted to switch to a survival mode.14 In this scenario, all energy and focus are directed toward minimizing the immediate threat, protecting reputation, and cutting costs.14 Although this leadership mentality can be necessary in the short-term response to crisis, it may marginalize the emotional needs of the team and the public, who are experiencing panic, isolation, anxiety, and helplessness.14 In addition, a persistent survival mentality can undermine the team’s sense of purpose and long-term mission.

Modern crises unfold in front of a worldwide audience because of the rise of the 24-hour news cycle and increased access to media.15 Therefore, today’s leaders must not only contend with the crisis itself, but also navigate scrutiny in real time; minute-to-minute updates can make or break public trust.15 This intense spotlight might tempt leaders to avoid blame and escape accountability for a crisis. These self-interested tendencies can foster an “every man for himself” mentality that sows mistrust among team members.16 Consequently, the leader’s communication style and degree of consistency shape the team’s morale and guide public perception of the leader’s response.17,18 Crisis researchers recognize that leaders who routinely deliver honest and empathetic communication are most effective during crisis.19 Although it is challenging to remain transparent about bad news and setbacks as a crisis develops, the payoff is that the team and the public perceive the leader as authentic.19 Thus, it is necessary that leaders avoid downplaying credible threats and overpromising positive outcomes that they know to be unrealistic. In addition, displays of genuine empathy for those affected by the crisis reflect self-awareness and acknowledgement of peripheral stakeholders (Table 1),20,21 not just their immediate organization. Table 2 offers a summary of the leadership principles that are linked with successful crisis response.12

Table 1.

Examples of Empathy and Emotional Intelligence in Crisis Response

| Tylenol Crisis (1982): Seven deaths in Chicago linked to Tylenol capsules laced with cyanide |

| Leadership spotlight: Johnson & Johnson |

| Response |

| • Ordered a nationwide recall of all 31 million bottles of Tylenol, a $100 million loss. |

| • Arranged counseling and financial compensation for families of the victims. |

| • Partnered with the FBI and Chicago Police, and offered a $100,000 reward for identifying the suspect. |

| • Established a hotline for consumers who had safety concerns. |

| • Tylenol is relaunched with the first tamper-evident packaging in the industry. |

| Boston Marathon Bombings (2013): Terrorist attack at the finish line of the Boston Marathon left three dead and over 260 injured |

| Leadership spotlight: Mayor Thomas Menino |

| Response |

| • Using Twitter, Menino leveraged inclusive language and messages of solidarity to unite the public in the effort to bring the suspects to justice. The hashtags #OneBoston and #BostonStrong created a shared sense of identity. |

| • Menino coordinated counseling services for victims. |

| • Following apprehension of the suspects, Menino’s communication style emphasized the need for community healing and forgiveness. |

FBI, Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Table 2.

Summary of Leadership Pearls and Pitfalls for an Effective Response to Crisis*

| Topic | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Anticipate | Predict what lies ahead |

| Pearl: Look for signs that announce possibility of a crisis; prepare for action | |

| Pitfall: Narrow-mindedness; consider all possibilities and consequences | |

| Navigate | Change direction as needed |

| Pearl: Be flexible and adapt the approach to manage the crisis | |

| Pitfall: Holding on to a plan that is not working | |

| Communicate | Communicate with honesty |

| Pearl: Communicate regularly and candidly | |

| Pitfall: Avoiding the delivery of bad news | |

| Pearl: Acknowledge new information and appreciate the messenger | |

| Pitfall: Assume people already know certain information | |

| Listen | Listen actively |

| Pearl: Show empathy and willingness to listen | |

| Pitfall: Avoid listening to news regarding setbacks or failures | |

| Learn and grow | Apply lessons learned |

| Pearl: Examine how the crisis was managed and identify areas for improvement | |

| Pitfall: Think that crisis will never happen again | |

| Pearl: Incorporate lessons learned, and use these to generate innovation | |

| Pitfall: Become complacent and hesitate to make changes |

*Adapted from Burnison G, Korn Ferry. A word from the CEO: Leading in a crisis. Available at: https://www.kornferry.com/insights/articles/burnison-coronavirus-leadership-crisis. Accessed May 30, 2020.

THE PAST INFORMS THE PRESENT

Research on crisis management and response will prove instrumental to inform future health care policies and business models in the aftermath of COVID-19. However, the field of crisis management research is relatively young and will likely evolve throughout the pandemic. The initial interest in formally studying crisis management was sparked by a series of man-made disasters in the 1980s, including the Chernobyl and Three Mile Island nuclear disasters.10 Around this time, crisis researchers argued that the incidence of crises was steadily multiplying as societies became increasingly industrialized, interdependent, and technologically advanced.10,15 In plastic surgery, this decade was marked by the first of many crises in the breast implant industry.

Case reports of women developing autoimmune diseases following breast augmentation with silicone implants were first documented in 1982.22 In the decade that followed, increased publicity and a growing number of women reporting adverse outcomes culminated in a class action lawsuit against implant manufacturer Dow Corning.22 Although the claims lacked robust scientific evidence, the leadership at Dow Corning handled the crisis poorly by delaying their disclosure of product safety information and failing to assume responsibility early on.23 This poor communication with the public exacerbated the negative media coverage of silicone breast implants, incited panic, and spurred further litigation amid insufficient safety data from implant manufacturers.24 In 1992, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a voluntary moratorium on silicone breast implants, a ban that was opposed by the American Medical Association and other professional societies.25

Evidence demonstrates that crises are becoming more common in modern society.10,15 Therefore, experts recommend that crises be reframed as continuous, compounding events, instead of singular entities.11,15,24 With this mindset, we can recognize the “incubation period” of a crisis.25 In this critical window, subtle signals and warnings provide leaders with opportunities for early intervention to avoid disaster.25 Therefore, leaders who declare “we never could have predicted this” or “no one saw this coming” may find themselves facing greater scrutiny, particularly if the leader failed to recognize or heed the warning signs. Effective crisis management requires proactive surveillance strategies to prevent crisis, in addition to mitigation efforts once a crisis arrives.11

Recent studies suggest that overhauling our approach to crisis response is long overdue. In 2018, consulting firm Deloitte conducted a global survey of over 500 corporate crisis managers.26 Although the study found that 90 percent of surveyed corporations were confident they could navigate a crisis, only 17 percent of these organizations had conducted a simulation to evaluate their preparedness.26 Similarly, an international crisis management consultant firm surveyed 200 organizations and found that approximately 40 percent lacked a crisis management plan.27 Of the companies that did have a plan in place, nearly 50 percent reported that the plan was not up to date.27 Although leaders and administrators invest in crisis management plans to maximize their preparedness, these contingency efforts frequently fall short of their goals, and few appear to be robust.28

When leaders fail to learn from past mistakes, or fail to act on warning signs, the results can be catastrophic. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services staged a series of exercises simulating a severe viral pandemic.29 The simulation, named “Crimson Contagion,” presented a scenario where tourists caught a respiratory virus while traveling in China and subsequently returned to the United States.29 Crimson Contagion was conducted to determine the capability of multiple levels of government to respond to a global health crisis and provide an opportunity to practice response actions.29,30 The exercise forecasted that over 110 million Americans would contract the virus, resulting in 7.7 million hospitalizations and 586,000 deaths.29 The exercise ultimately revealed the limited capacity of the government to respond to such an event. Key findings demonstrated that federal agencies lacked the funds, coordination, and resources to facilitate an effective response to a viral pandemic.29 Crimson Contagion concluded several months before the COVID-19 outbreak and accurately predicted many of the problems the United States is currently facing. Simply conducting an exercise to identify gaps in crisis preparedness is not enough; leaders must be resolute in taking steps to prevent the crisis from occurring and embrace decisiveness.

Perhaps the most underappreciated aspect of effective crisis response is how leaders handle the aftermath, and the extent to which they capitalize on the lessons learned.30 Although the breast implant industry has faced numerous crises, improvements in regulatory and quality control practices have lagged behind.22 Following the Dow Corning breast implant scandal in the 1980s, the second major crisis in the industry surfaced in 2011, when cheap, nonmedical grade silicone gel breast implants manufactured by Poly Implant Prothèse were linked to high rates of premature rupture.31 Although European regulatory agencies were aware as early as 2001 that these adverse events were taking place, it was not until 2010 that the United Kingdom and France suspended the sale of Poly Implant Prothèse silicone gel breast implants.22 It is estimated that breast augmentations using Poly Implant Prothèse silicone gel implants were performed in over 300,000 women across 65 countries.22 From this and other crises, it is clear that identifying our weaknesses is only half the battle. Translating new knowledge into targeted actions is critical to close the loop and minimize the chance that a similar crisis will arise again.30

The Poly Implant Prothèse breast implant crisis resulted in the establishment of opt-out breast implant registries that are supported by international collaborations.22 As some are concerned that the next crisis in this industry may be breast-implant associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), efforts to maintain breast implant registries will produce reliable data surrounding the risk and incidence of this disease. Textured implants and those with high surface areas have been implicated in cases of BIA-ALCL.22 Prospective data collection on BIA-ALCL demonstrates that plastic surgery leaders are leveraging the lessons learned from past crises to anticipate rather than to react to these potential threats.32 In 2012, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons partnered with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the Plastic Surgery Foundation to develop the Patient Registry and Outcomes for Breast Implants and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Etiology and Epidemiology (PROFILE).32 Although arguments have been made for banning textured implants, the availability of high-quality, prospective data has provided regulatory agencies with reliable evidence to dismiss these calls.22 Data generated from the Plastic Surgery Foundation to develop PROFILE show that the estimated risk of developing BIA-ALCL for women with implants is one to three per 1 million per year.33 Painful as it may be, a crisis is a wake-up call for leaders to spring into action and initiate growth.

DISCUSSION

“Crisis in Plastic Surgery” is the title of a 1967 editorial published in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery.34 The article details the author’s concern that a surge in scientific discovery was creating a disconnect between the academic and practicing plastic surgeon.34 In short, the busy practitioner could not keep up with the pace of academic research. Today, plastic surgery faces a new crisis that makes its prior dilemmas pale in comparison; the COVID-19 pandemic may be the largest test of plastic surgery leadership witnessed in recent memory.

During the current pandemic, the responses of leaders have varied. The U.S. response to COVID-19 has been plagued by confusion and shortcomings identified in the Crimson Contagion simulation 1 year ago.35 Federal, state, and local officials delivered conflicting messages, hampering a coordinated national response.36 On the other side of the world, leaders in New Zealand have received acclaim for aggressively flattening the curve.37 On March 21, 2020, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern unveiled plans for a four-level COVID-19 alert system.38 This strategy was adapted from the wildfire risk system that was already well known to New Zealanders, creating a familiar model for the population to understand. The four-level alert system clearly illustrated how the nation’s response would escalate,39 and provided citizens with an understanding of the potential policy changes.38 When the number of New Zealand’s cases quadrupled in the span of 4 days, the alert system was raised to the highest level, activating a nationwide shelter-in-place.39 In addition, Ardern effectively communicated the importance of tough restrictions that the public understood and accepted, and her displays of empathy have been credited with bringing the nation together during the COVID-19 crisis.37 The prime minister was routinely visible to the public on Facebook Live chats, where she made efforts to recognize the strain that social distancing was placing on families.37

Ardern’s ability to act decisively, demonstrate empathy, communicate effectively, and instill solidarity has been cited as instrumental in controlling COVID-19 transmission in New Zealand.37 It is inspiring to see that these characteristics are also visible in the response of plastic surgery leaders to this crisis. Shortly after the World Health Organization officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons partnered with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to set up supply chains for plastic surgeons to donate ventilators and personal protective equipment from private practices to support hospitals in need.40 By March 26, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons had procured 6 million N95 masks and over 20,000 surgical masks for medical centers in New York City, a region that faced dire personal protective equipment supply shortages early in the pandemic’s course.8 State and local governments in Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey, and New York also directly collaborated with American Society of Plastic Surgeons leadership to allocate ventilator and medical supply donations to hospitals with the greatest need. These swift decisions enabled rapid mobilization of supplies and put plastic surgeons in a position to stand united in responding to the COVID-19 threat. In addition, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons has remained transparent about the economic hardships and drastic changes that its members will face in the coming months and has routinely communicated strategies to guide its members through this tumultuous time. A wealth of online resources from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons is available to assist with core issues that plastic surgeons must confront: recommendations for safely resuming elective procedures, options for private practices to maintain financial solvency, and strategies for maximizing the potential of telemedicine.40

Information surrounding SARS-CoV-2 is constantly evolving and proliferating. This pandemic exemplifies the need for health care leaders to consistently deliver the facts during a crisis, particularly in the face of emerging COVID-19 misinformation campaigns that engender fear and confusion. Health care leadership must routinely and openly communicate with their teams and the public, and provide recommendations and policy updates that are specific and clear. Furthermore, health care leaders should acknowledge the emotional toll this crisis has taken on their workforce and offer an outlet for colleagues to express themselves. Recognition and empathy for feelings of anxiety and isolation among health care teams is particularly relevant, considering the ongoing social distancing requirements and persistent fear of bringing the virus home to family members. Certain hospitals have responded by implementing weekly social hours and scheduled time for virtual interaction among team members. To assist hospital workers with childcare needs, the University of Washington developed a registry of medical students, family, and friends who are available to help.41 These initiatives reflect leadership that effectively used emotional intelligence in times of crisis.

Today’s leaders cannot afford to ignore the lessons learned from crisis. Surviving the crisis should no longer be viewed as the finish line. Instead, we must identify avenues for change, invest in new preventive strategies, and commit to following through on our goals. Although crises may appear to occur out of nowhere, this is rarely the case; signs and signals are typically present long before the crisis manifests. Our leaders must not only prepare for how to act when crisis occurs, but pledge to actively surveil, detect red flags, and sound the alarm for future crises. In addition, leaders must communicate with candor, as public trust is crucial to positive outcomes. The most effective leaders display empathy and maintain transparency at all costs, even if this means admitting setbacks or breaking difficult news.

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Chung receives funding from the National Institutes of Health and book royalties from Wolters Kluwer and Elsevier and is a consultant for Axogen. He is a consultant for Axogen and Integra. The remaining authors have no financial interest to disclose. No funding was received for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Woolliscroft JO. Innovation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Acad Med. 2020;95:1140–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang S, Shi Z, Shu Y, et al. A distinct name is needed for the new coronavirus. Lancet 2020;395:949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorden MA, Rudman SL, Villarino E, et al. Evidence for limited early spread of COVID-19 within the United States, January–February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:680–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. CMS releases recommendations on adult elective surgeries, non-essential medical, surgical, and dental procedures during COVID-19 response. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-releases-recommendations-adult-elective-surgeries-non-essential-medical-surgical-and-dental. Accessed June 2, 2020.

- 5.Squitieri L, Chung KC. Surviving the COVID-19 pandemic: Surge capacity planning for nonemergent surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu S, Li Y. Beware of the second wave of COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1321–1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicola M, Alsafi Z, Sohrabi C, et al. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int J Surg. 2020;78:185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snyder P; American Society of Plastic Surgeons. ‘Nightmare stuff’: Members brace for COVID-19 battle, uncertainty. Available at: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/publications/psn-extra/news/nightmare-stuff-members-brace-for-covid19-battle-uncertainty. Accessed June 2, 2020.

- 9.Mims KY. Uncharted territory: Plastic surgeons in private practice navigate financial uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic. Available at: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/publications/psn-extra/news/uncharted-territory. Accessed June 2, 2020.

- 10.Shrivastava P, Mitroff II, Miller D, Miglani A. Understanding industrial crises. J Manage Stud. 1988;25:285–303. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaques T. Reshaping crisis management: The challenge for organizational design. Organ Dev J. 2010;28:9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnison G; Korn Ferry. A word from the CEO: Leading in a crisis. Available at: https://www.kornferry.com/insights/articles/burnison-coronavirus-leadership-crisis. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 13.Hart P, Rosenthal U, Kouzmin A. Crisis decision-making: The centralization thesis revisited. Admin Soc. 1993;25:12–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korn Ferry Institute. The COVID-19 leadership guide: Strategies for managing through the crisis. Available at: https://www.kornferry.com/content/dam/kornferry/special-project-images/coronavirus/docs/KF_Leadership_Playbook_Global_MH_V14.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 15.Hart P, Heyse L, Boin A. New trends in crisis management practice and crisis management research. J Contingencies Crisis Manage. 2002;9:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnison G; Korn Ferry. Mission first, people always. Available at: https://www.kornferry.com/insights/articles/mission-first-people-always-leadership. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 17.Brändström A. Crisis, Accountability and Blame Management: Strategies and Survival of Political Office-Holders (dissertation). Utrecht, The Netherlands: Swedish Defence University, Department of Security, Strategy and Leadership (ISSL), CRISMART (National Center for Crisis Management Research and Training). Utrecht University;2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnison G; Korn Ferry. The opposite of fear. Available at: https://www.kfadvance.com/articles/opposite-of-fear. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 19.Seeger MW. Best practices in crisis communication: An expert panel process. J Appl Commun Res. 2006;34:232–244. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams GA, Woods CL, Staricek NC. Restorative rhetoric and social media: An examination of the Boston Marathon bombing. Commun Stud. 2017;68:385–402. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Tylenol and the legacy of J&J’s James Burke. Available at: https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/tylenol-and-the-legacy-of-jjs-james-burke/. Accessed August 28, 2020.

- 22.Deva AK, Cuss A, Magnusson M, Cooter R. The “game of implants”: A perspective on the crisis-prone history of breast implants. Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(Suppl 1):S55–S65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schleiter KE. Silicone breast implant litigation. AMA Journal of Ethics. . Available at: https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/silicone-breast-implant-litigation/2010-05. Accessed August 28, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sands P. Outbreak readiness and business impact protecting lives and livelihoods across the global economy. World Economic Forum. January2019. Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF%20HGHI_Outbreak_Readiness_Business_Impact.pdf. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 25.Jaques T. Embedding issue management as a strategic element of crisis prevention. Disaster Prev Manag. 2010;19:469–482. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travers W; Deloitte. Despite rising crises, Deloitte study finds organizations’ confidence exceeds crisis preparedness. Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/about-deloitte/press-releases/deloitte-study-finds-organizations-confidence-exceeds-crisis-preparedness.html. Accessed May 12, 2020.

- 27.Arenstein S. 62% have crisis plans, but few update them or practice scenarios. PR News. February52020. Available at: https://www.prnewsonline.com/crisis-survey-CSA-practice. Accessed May 12, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vittoria A. Corporate boards slammed by coronavirus rethink risk planning. Bloomberg Law. April292020. Available at: https://news.bloomberglaw.com/corporate-governance/corporate-boards-slammed-by-coronavirus-rethink-risk-planning. Accessed May 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanger DE, Lipton E, Sullivan E, Crowley M. Before virus outbreak, a cascade of warnings went unheeded. The New York Times. March192020. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/19/us/politics/trump-coronavirus-outbreak.html. Accessed June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaques T; Managing Outcomes. Why hold a crisis exercise then ignore the lessons? Issue outcomes. Available at: https://us1.campaign-archive.com/?u=12234fd351f8df7c1f43248ea&id=397590ec67. Accessed May 30, 2020.

- 31.Greco C. The Poly Implant Prothèse breast prostheses scandal: Embodied risk and social suffering. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCarthy CM, Loyo-Berrios N, Qureshi AA, et al. Patient Registry and Outcomes for Breast Implants and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma Etiology and Epidemiology (PROFILE): Initial report of findings, 2012-2018. Plast Reconstr Surg.2019;143(A Review of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma):65S–73S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones JL, Hanby AM, Wells C, et al.; National Co-ordinating Committee of Breast Pathology. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL): An overview of presentation and pathogenesis and guidelines for pathological diagnosis and management. Histopathology 2019;75:787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffen WO. Crisis in plastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40:291–293. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abutaleb Y, Dawsey J, Nakashima E, Miller G. The U.S. was beset by denial and dysfunction as the coronavirus raged. The Washington Post. April42020. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2020/04/04/coronavirus-government-dysfunction/?arc404=true. Accessed June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Science News Staff. The United States leads in coronavirus cases, but not pandemic response. Science. April12020. Available at: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/united-states-leads-coronavirus-cases-not-pandemic-response. Accessed June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarthy J. Praised for curbing COVID-19, New Zealand’s leader eases country’s strict lockdown. NPR. April252020. Available at: https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/25/844720581/praised-for-curbing-covid-19-new-zealands-leader-eases-country-s-strict-lockdown. Accessed June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerrissey MJ, Edmondson AC. What good leadership looks like during this pandemic. Harvard Business Review. April132020. Available at: https://hbr.org/2020/04/what-good-leadership-looks-like-during-this-pandemic. Accessed June 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39.New Zealand Ministry of Health. New Zealand COVID-19 alert levels. Unite against COVID-19 Web site. Available at: https://covid19.govt.nz/assets/resources/tables/COVID-19-alert-levels-detailed.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2020.

- 40.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. ASPS coordinates state-level COVID-19 efforts. Available at: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/for-medical-professionals/advocacy/advocacy-news/asps-coordinates-state-level-covid19-efforts. Accessed June 2, 2020.

- 41.Cho DY, Yu JL, Um GT, Beck CM, Vedder NB, Friedrich JB. The early effects of COVID-19 on plastic surgery residency training: The University of Washington experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]