Abstract

Purpose of review

To provide the latest evidence and treatment advances of multiple sclerosis in women of childbearing age prior to conception, during pregnancy and postpartum.

Recent findings

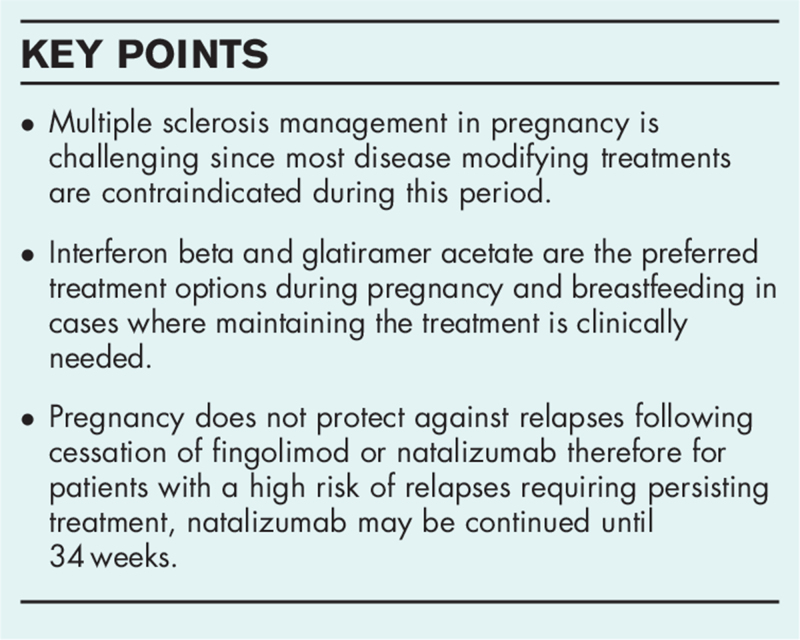

Recent changes permitting interferon beta (IFN-β) use in pregnancy and breastfeeding has broadened the choices of disease modifying treatments (DMTs) for patients with high relapse rates. Natalizumab may also be continued until 34 weeks of pregnancy for patients requiring persisting treatment. Drugs with a known potential of teratogenicity such as fingolimod or teriflunomide should be avoided and recommended wash-out times for medications such as cladribine, alemtuzumab or ocrelizumab should be considered. Teriflunomide and fingolimod are not recommended during breastfeeding, however, glatiramer acetate and IFN-β are considered to be safe.

Summary

The evidence of potential fetotoxicities and adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with DMTs is increasing, although more research is needed to evaluate the safety of drugs and to track long-term health outcomes for the mother and the child.

Keywords: breastfeeding, disease modifying treatment, multiple sclerosis, pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is defined as a degenerative and chronic autoimmune disease affecting the central nervous system (CNS) in which demyelination, inflammation, and axonal damage develops in the early stages of the disease. Typically, MS presents as an active intermittent disease (relapsing-remitting MS), however in around 15% of patients MS presents in a progressive course (primary progressive MS) [1]. MS mostly affects females of childbearing age (20–40 years). Evidence from a landmark Pregnancy in MS (PRIMS) study decades ago turned down beliefs that pregnancy was harmful for women with MS. The PRIMS study also demonstrated the increased risk of MS relapses within the first 3–4 months after delivery, especially for patients with very active MS prior to conception [2]. Over the recent decades, MS treatment has extremely progressed. Various disease modifying treatments (DMTs) have been approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These medications now represent a first-line treatment option for women diagnosed with MS due to its effectiveness in lowering MS severity and relapses, and reducing the progression of new CNS lesions. In terms of the pregnancy in women diagnosed with MS, pharmaceutical management is challenging [4]. Scientific literature provides evidence mainly for pregnant patients administered with either glatiramer acetate (GA) or interferon beta (IFN-β), whilst evidence on highly effective DMTs that has recently been released to the market is still lacking [3]. With the creation of new and effective DMTs, new considerations have arisen for the wash-out needs of these medications prior to conception, safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Premarketing data precludes recommendations concerning DMTs safety in pregnancy due to the limited numbers of pregnancies occurring during clinical trials. Consequently, mostly all DMTs are not recommended in pregnancy except when the treatment of the disease outweighs the potential risks to the fetus.

The aim of this narrative review is to focus on the pharmacotherapeutic considerations for women with MS during pregnancy and to provide the latest evidence regarding the safety of DMTs in this setting.

Box 1.

no caption available

INTERFERON BETA

IFN-β is a polypeptide with a molecular weight ranging from 18.5 to 22.5 kDA, therefore due to its high molecular weight, IFN-β does not cross the placenta [6]. In September 2019, the EMA released an update allowing its use to be considered prior to conception, in pregnancy and while breastfeeding. The revised recommendation was centered on recent safety data from two large cohort studies investigating pregnant women exposed to IFN-β. The European IFN-β Pregnancy Registry evaluated 948 pregnancies in 26 countries and detected no significant differences of inborn abnormalities or spontaneous abortions rates in women exposed to IFN-β prior or during pregnancy compared to the general population [7▪]. A few months later, a similar Nordic cohort study was published presenting the results of 232 Finnish and 411 Swedish pregnancies exposed to IFN-β. Compared to the unexposed group, no differences in birth weight, length and head circumferences were detected in infants exposed to IFN-β during pregnancy [8▪].

In regard to breastfeeding, because of its high molecular weight, only low amounts of IFN-β (around 0.006% of the maternal dose) passes into breast milk [9]. A very recent study done by Ciplea et al. investigated 39 women breastfeeding under IFN-β. Potential infant exposure to IFN-β (median duration 8.5 months) resulted in no adverse outcomes in the first year of life [10].

GLATIRAMER ACETATE

GA is a complex polypeptide with a similar molecular weight to IFN-β, thus due to its large size, it is not likely to be able to cross the placental barrier. Data from a large study analyzing Teva's global pharmacovigilance database including 7000 pregnancies collected over a 20-year period have provided significant information on the safety of GA in pregnancy. In total there were 5042 pregnancies with known outcomes, including 4034 live births (2366 healthy infants, 1557 newborns with no inborn abnormalities and 111 newborns with congenital and/or perinatal disruptions); 138 elective abortions; 53 extrauterine pregnancies; 49 stillbirths; 9 not specified pregnancy terminations and 6 hydatidiform moles. The most frequent inborn anomalies were 21st chromosome trisomy (n = 13), congenital heart defects (n = 9), congenital talipes equinovarus (n = 8) and hip dysplasia (n = 7). After comparing these outcomes to the general population, the study reported that pregnancies exposed to GA were not at an increased risk for inborn abnormalities [11]. This data provided significant evidence regarding GA exposure in pregnancy, which appears to be safe and with no teratogenic events.

In terms of breastfeeding, GA by most experts is considered to be safe, but the evidence on safety is scarce. In the previously mentioned study by Ciplea et al. 34 breastfeeding women who received GA daily were followed for 1 year. No conditions associated with potential infant exposure to GA were detected [10].

DIMETHYL FUMARATE

Dimethyl fumarate is a low molecular weight molecule (144 Da) and has a terminal half-life of one hour [11]. In 2019, Hellwig et al. presented an analysis of pregnancy outcomes in women with MS treated with dimethyl fumarate. An international register enrolled 194 pregnancies with known outcomes including 177 live births and 17 lost pregnancies. 7 birth defects were documented in this prospective study: 2 newborns with a ventricular septal defect, 1 with transposition of the great arteries, 1 with pyloric stenosis, 1 with hydronephrosis and 1 with unilateral developmental hip dysplasia. The rates of premature births, spontaneous abortions, birth weight and inborn defects in pregnancies exposed to dimethyl fumarate did not differ from the general population [12]. Even though no potential risks or fetotoxicities were reported, current evidence is too scarce to draw any conclusions. At this stage, dimethyl fumarate is not recommended during pregnancy and should be avoided unless it is clearly necessary and the potential treatment benefits outweigh the risk to the fetus.

TERIFLUNOMIDE

Teriflunomide is a small molecule with a molecular weight of 270 Da and has a mean half-life of 15–18 days. However, due to its extensive enterohepatic recycling it may take 8–24 months to reach negligible serum concentrations after the discontinuation of teriflunomide [13]. Teriflunomide is contraindicated for MS patients planning to conceive due to teratogenicity and embryotoxicity being demonstrated in animal studies [14]. Despite the various guidelines recommending efficient contraception, pregnancies exposed to teriflunomide have been recorded. In June 2020, Vukusic et al. published a study analyzing the outcomes of 222 pregnancies occurring during treatment with teriflunomide. The study reported 107 live births, 63 elective and 47 spontaneous abortions, 3 extrauterine pregnancies, 1 stillbirth and 1 maternal death. Among the known pregnancy outcomes, the study reported 5 birth defects (cystic hygroma, ureteropyeloectasia, foot valgus deformity, congenital heart defect and hydrocephalus). The authors concluded that the outcomes of the pregnancies exposed to teriflunomide were conforming with the general population [15]. More recently, in August 2020, similar results were reported by Henson et al. After analyzing 587 pregnancies occurring while being treated with leflunomide (the parent compound of teriflunomide), the study concluded that the outcomes did not differ from the general population and did not indicate embryofetal toxicities with leflunomide [16]. Likewise, the outcomes of pregnancies in female partners of males with MS treated with leflunomide or teriflunomide have been studied as both of these drugs are detectable in the semen at very low levels. A study by Vukusic et al. analyzed 105 pregnancy outcomes and no detectable signals of teratogenicity were noticed in women with male partners receiving teriflunomide or leflunomide [17].

Even though the most recent data does not demonstrate teratogenic effects in teriflunomide or leflunomide exposed pregnancies, the numbers are still too low to draw any conclusions. Also, there is no evidence regarding the safety of exposure to these drugs in the second and third trimesters. In the event of an unexpected pregnancy or desired conception, MS patients should be recommended to stop the treatment with teriflunomide or use an accelerated elimination procedure with activated charcoal or cholestyramine. Teriflunomide is a small molecular weight drug and is likely to be excreted into breast milk so for that reason, breastfeeding is contraindicated [14].

ALEMTUZUMAB

Alemtuzumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to lymphocytes CD52 surface receptor. It has a molecular weight of 150 kDa, a 4–5-day half-life and is fully eliminated in a 30-day period [18]. The major concern with alemtuzumab use in pregnancy is an increased risk of autoimmune thyroiditis and the fetal risks related to it, including premature birth, preeclampsia, reduced birth weight and neurocognitive impairment [19,20]. Like other monoclonal antibodies, alemtuzumab does not cross the placental barrier during the first trimester. Regardless, drug labels advise to use effective birth control for women with reproductive potential during and at least 4 months after finishing the treatment with alemtuzumab [18]. In May 2020, Oh et al. published a study investigating 264 pregnancies exposed to alemtuzumab. Among all pregnancies, 67% were live births with no inborn defects, 22% were spontaneous and 11% were elective abortions while 1 pregnancy ended as a stillbirth. This study did not detect a significant difference between women conceiving before or after the recommended 4-month post alemtuzumab exposure contraception window, and spontaneous abortion rates were comparable with the rates in the general population [21]. Like most monoclonal antibodies, alemtuzumab is excreted into breast milk, therefore breastfeeding is not recommended [18].

FINGOLIMOD

Fingolimod is a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonist and has a low molecular weight of 307 Da enabling the drug to cross the placental barrier [22]. In July 2019, the EMA updated restrictions for fingolimod use in pregnancy and recommended to stop fingolimod at least 2 months prior to conception. In case of unplanned pregnancy while being treated with fingolimod, the treatment must be stopped and the pregnancy closely monitored [23]. These updated restrictions were triggered by previous reports of the risk of birth defects (heart, muscles and bones) being twice as high for infants exposed to fingolimod in pregnancy [24]. However, later studies by Geissbühler et al.[25] and Pauliat et al.[26] investigating pregnancy outcomes in women with MS exposed to fingolimod did not detect any significant increase in the risk of major congenital anomalies. The updated results of pregnancy outcomes exposed to fingolimod during pregnancy or for up 2 months before conception have been reported at the European Committee for Treatment and Research in MS (ECTRIMS) congress in September, 2019. After analyzing 1586 prospective cases of maternal exposure to fingolimod, researchers concluded that the estimated risk of major congenital malformations was between 2.04 and 5.3% which was similar to the estimated risk in the general population (2.04–4.5%) [27].

Pregnancy does not protect against MS relapses, and some women experience severe MS relapses as early as 1–4 months after cessation of fingolimod [28]. To avoid disease reactivation in women desiring pregnancy and receiving fingolimod, treatment could be switched to natalizumab prior to pregnancy [29]. Patients should be informed that fingolimod can be identified in breast milk, therefore breastfeeding is not recommended [30].

NATALIZUMAB

Natalizumab is an IgG4 humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the lymphocyte α4-integrin receptor. Natalizumab is a large molecule with a molecular weight of 150 kDa and is believed not to cross the placental barrier until the second trimester [31]. Cessation of natalizumab prior or during pregnancy may result in severe MS reactivation starting from the second month after the last infusion [32]. According to the recent Italian multicenter cohort study, cessation of natalizumab early in pregnancy instead of prior to conception, significantly reduces MS relapses [33]. The strategy of continuing natalizumab after conception has become more used in clinical practice therefore current research is focusing on how long natalizumab should be used in pregnancy. Data analysis of 92 completed pregnancies exposed to natalizumab collected from 19 Italian MS centers was presented in the 2019 ECTRIMS congress. Women with MS were divided into 3 groups with respect to the last infusion of natalizumab: the first group was prior to conceiving, the second group was in the middle of the first trimester of pregnancy while the third group continued natalizumab into the third trimester. This study concluded that natalizumab continuation later into pregnancy resulted in lower annualized relapse rates compared to cessation prior or early in pregnancy. Also, this study detected no alarming adverse events for the infants exposed to natalizumab [34]. These recommendations were incorporated into the updated guidelines of the Association of British Neurologists on pregnancy management in MS in January 2019. It is now suggested to continue natalizumab until 34 weeks of gestation for women with high MS activity requiring persisting treatment and to resume the treatment postpartum in 8–12 weeks after the last dose. To reduce the exposure, instead of 4-weekly infusions, natalizumab infusions can be reduced to 8-weekly [35]. The latest research investigating pregnancy outcomes of MS women with third-trimester natalizumab use was published by Triplett et al. in January 2020. In this study, 15 live births occurred in 13 females treated with natalizumab during the second and third trimesters. Hematological alterations were confirmed in 5 newborns, which included anemia (n = 2) and thrombocytopenia (n = 3) [36▪▪].

In terms of breastfeeding, the latest studies show that the concentration of natalizumab in the serum of newborns and breast milk is low [37], therefore breastfeeding under natalizumab is likely to be safe and outweighs risks of potential newborn exposure [38].

OCRELIZUMAB

Ocrelizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal immunoglobulin G that selectively targets the CD20 B-lymphocytes. Preliminary data from a study investigating 267 pregnancies of MS women exposed to ocrelizumab was presented in the 2019 ECTRIMS congress. Administration to the drug was considered if the pregnancy occurred within three months after the last ocrelizumab infusion. The study did not reveal an increased risk of negative pregnancy outcomes, including spontaneous abortions or congenital anomalies [39]. However, female patients of childbearing age are advised to use effective birth control while receiving ocrelizumab up to 12 months (an EMA recommendation) or for at least 6 months (an FDA recommendation) after the last infusion [40,41]. Breastfeeding is not suggested for at least 6 months after the last infusion of ocrelizumab. B-cells should be monitored in the infant and in the case of B-cell depletion, vaccination should be postponed until the B-cell count returns to normal (which usually takes 6–10 months) [5].

CLADRIBINE

Cladribine is a purine nucleoside analog that inhibits DNA synthesis and causes the suppression of rapidly dividing cells. Cladribine is a small molecule with a low molecular weight of 285 Da allowing placental transfer during pregnancy [42]. Cladribine has demonstrated teratogenicity and embryonic lethality in animal studies and therefore women with reproductive potential are advised to use effective contraception for at least 6 months after the last dose of cladribine [43]. Although contraception is advised during cladribine treatment, some pregnancies do occur. In May 2020 Giovannoni et al. published an analysis of pregnancy outcomes in the cladribine clinical development program. There were 70 pregnancies in total: 49 in the cladribine group and 21 in the control group. Pregnancy outcomes in women exposed to cladribine during the ‘at-risk’ period were consistent with epidemiological data of pregnancy outcomes for the general population [44]. Regardless of this data, the current evidence surrounding cladribine remains very limited and for that reason, women receiving cladribine should avoid pregnancy and breastfeeding.

CONCLUSION

The pharmacotherapeutic considerations in patients with MS considering pregnancy are complex as the treatment continuation and/or interruption affects both the mother and the fetus. Recent changes permitting IFN-β use in pregnancy and breastfeeding has broadened the choices of DMTs for patients with high relapse rates. Natalizumab may be also continued until 34 weeks of pregnancy for patients requiring persisting treatment. Healthcare providers should avoid prescribing drugs with known potential teratogenicity like fingolimod or teriflunomide and recommended wash-out times for medications such as cladribine, alemtuzumab or ocrelizumab should be considered. Teriflunomide and fingolimod are not recommended during breastfeeding, while GA and IFN-β are considered to be safe. Thanks to large observational studies and data from pregnancy registries, the evidence of potential fetotoxicities and adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with DMTs is increasing. However, more research is needed to evaluate the safety of drugs and to track long-term health outcomes for the mother and the child.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Vidal-Jordana A, Montalban X. Multiple sclerosis: epidemiologic, clinical, and therapeutic aspects. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2017; 27:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Confavreux C, Hutchinson M, Hours MM, et al. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zanghì A, D’Amico E, Callari G, et al. Pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treated with old and new disease-modifying treatments: a real-world multicenter experience. Front Neurol 2020; 11:105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Añaños-Urrea M, J. Modrego P. Interactions between multiple sclerosis and pregnancy. Current landscape of approved treatments. Clin Res Trial 2020; 6: Available from: https://www.oatext.com/interactions-between-multiple-sclerosis-and-pregnancy-current-landscape-of-approved-treatments.php. [Accessed 12 March 2021]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canibaño B, Deleu D, Mesraoua B, Melikyan G, et al. Pregnancy-related issues in women with multiple sclerosis: an evidence-based review with practical recommendations. J Drug Assess 2020; 9:20–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neuhaus O, Kieseier BC, Hartung H-P. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the interferon-betas, glatiramer acetate, and mitoxantrone in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2007; 259:27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7▪.Hellwig K, Geissbuehler Y, Sabidó M, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in interferon-beta-exposed patients with multiple sclerosis: results from the European Interferon-beta Pregnancy Registry. J Neurol 2020; 267:1715–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cohort study investigating pregnant women exposed to IFN-β.

- 8▪.Hakkarainen KM, Juuti R, Burkill S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after exposure to interferon beta: a register-based cohort study among women with MS in Finland and Sweden. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2020; 13:1756286420951072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cohort study investigating pregnant women exposed to IFN-β.

- 9.Hale TW, Siddiqui AA, Baker TE. Transfer of Interferon β-1a into human breastmilk. Breastfeeding Med 2011; 7:123–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciplea AI, Langer-Gould A, Stahl A, et al. Safety of potential breast milk exposure to IFN-β or glatiramer acetate: one-year infant outcomes. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2020; 7:e757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. EMA. Tecfidera (dimethyl fumarate) – EPAR summary of product characteristics 2014. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_ Product_Information/human/002601/WC500162069.pdf. [Accessed 12 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hellwig K, Rog D, McGuigan C, et al. An international registry tracking pregnancy outcome in women treated with dimethyl fumarate [Internet]. 2019. P1147. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.ectrims-congress.eu/ectrims/2019/stockholm/278349/kerstin.hellwig.an.international.registry.tracking.pregnancy.outcomes.in.women.html?f=listing%3D0%2Abrowseby%3D8%2Asortby%3D1%2Asearch%3Ddimethyl+fumarate. [Accessed 12 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiese MD, Rowland A, Polasek TM, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of teriflunomide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2013; 9:1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. FDA. Aubagio [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Genzyme Corporation. [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/202992s000lbl.pdf. [Accessed 12 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vukusic S, Coyle PK, Jurgensen S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with teriflunomide: clinical study data and 5 years of postmarketing experience. Mult Scler 2020; 26:829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henson LJ, Afsar S, Davenport L, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients treated with leflunomide, the parent compound of the multiple sclerosis drug teriflunomide. Reproduct Toxicol 2020; 95:45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vukusic S, Hellwig K, Truffinet P, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in female partners of male patients treated with teriflunomide or leflunomide (an in vivo precursor of teriflunomide). Abstract (P1146) at the ECTRIMS 2019 congress. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.ectrims-congress.eu/ectrims/2019/stockholm/278348/sandra.vukusic.pregnancy.outcomes.in.female.partners.of.male.patients.treated.html. [Accessed 12 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lemtrada SPC. European Medicines Agency. 2019. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/lemtrada-epar-product-information_en.pdf. [Accessed 12 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decallonne B, Bartholomé E, Delvaux V, et al. Thyroid disorders in alemtuzumab-treated multiple sclerosis patients: a Belgian consensus on diagnosis and management. Acta Neurol Belg 2018; 118:153–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galofre JC, Davies TF. Autoimmune thyroid disease in pregnancy: a review. J Womens Health 2009; 18:1847–1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh J, Achiron A, Celius EG, et al. CAMMS223, CARE-MS I, CARE-MS II, CAMMS03409, and TOPAZ Investigators. Pregnancy outcomes and postpartum relapse rates in women with RRMS treated with alemtuzumab in the phase 2 and 3 clinical development program over 16 years. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020; 43:102146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gilenya (fingolimod) prescribing information FDA. 2019 Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/022527s009lbl.pdf. [Accessed 13 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Multiple Sclerosis Awareness. 2019. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/press-release/updated-restrictions-gilenya-multiple-sclerosismedicine- not-be-used-pregnancy_en.pdf. [Accessed 13 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karlsson G, Francis G, Koren G, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in the clinical development program of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2014; 82:674–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geissbühler Y, Vile J, Koren G, et al. Evaluation of pregnancy outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis after fingolimod exposure. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018; 11.Nov 3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6236588/ [Accessed 13 March 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pauliat E, Onken M, Weber-Schoendorfer C, et al. Pregnancy outcome following first-trimester exposure to fingolimod: a collaborative ENTIS study. Mult Scler 2021; 27:475–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leon Lopez S, Geissbuehler Y, Moore A, et al. Effect of fingolimod on pregnancy outcomes in patients with multiple sclerosis. ECTRIMS Online Library 2019; 278772:P411. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meinl I, Havla J, Hohlfeld R, et al. Recurrence of disease activity during pregnancy after cessation of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2018; 24:991–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alroughani R, Inshasi J, Al-Asmi A, et al. Disease-modifying drugs and family planning in people with multiple sclerosis: a consensus narrative review from the Gulf Region. Neurol Ther 2020; 9:265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alroughani R, Altintas A, Al Jumah M, et al. Pregnancy and the use of disease-modifying therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis: benefits versus risks. Mult Scler Int 2016; 2016:1034912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tysabri (natalizumab) European Summary of product Characteristics. 2019. Available from https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/222. [Accessed 14 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plavina T, Muralidharan KK, Kuesters G, et al. Reversibility of the effects of natalizumab on peripheral immune cell dynamics in MS patients. Neurology 2017; 89:1584–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portaccio E, Moiola L, Martinelli V, et al. Pregnancy decision-making in women with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: II: Maternal risks. Neurology 2018; 90:e832–e839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landi D, Portaccio E, Bovis F, et al. Continuation of natalizumab versus interruption is associated with lower risk of relapses during pregnancy and postpartum in women with MS. ECTRIMS Online Libr 2019; 338:279583. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobson R, Dassan P, Roberts M, et al. UK consensus on pregnancy in multiple sclerosis: ‘Association of British Neurologists’ guidelines. Pract Neurol 2019; 19:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36▪▪.Triplett JD, Vijayan S, Rajanayagam S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes amongst multiple sclerosis females with third trimester natalizumab use. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2020; 40:101961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Newest research of pregnancies outcomes of natalizumab exposure in the last trimester.

- 37.Ciplea AI, Langer-Gould A, de Vries A, et al. Monoclonal antibody treatment during pregnancy and/or lactation in women with MS or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2020; 7:e723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ciplea AI, Hellwig K. Exposure to natalizumab during pregnancy and lactation is safe – commentary. Mult Scler 2020; 26:892–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oreja-Guevara C, Wray S, Buffels R, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients treated with ocrelizumab. ECTRIMS Online Library 2019; 279140:780. [Google Scholar]

- 40. U.S. FDA Registration. 2019. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/761053lbl.pdf. [Accessed 15 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 41. European Medicines Agency. 2019. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/ocrevus-epar-product-information_en.pdf. [Accessed 15 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cladribine prescribing information FDA. 2019. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_ docs/label/2019/022561s000lbl.pdf. [Accessed 17 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 43. EMA. EMA Mavenclad [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information /mavenclad-epar-product-information_en.pdf. [Accessed 17 March 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giovannoni G, Galazka A, Schick R, et al. Pregnancy outcomes during the clinical development program of cladribine in multiple sclerosis: an integrated analysis of safety. Drug Saf 2020; 43:635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]