Abstract

Objective: The main objective of this study was to review aspects of the current situation and structure of the integrated mental health care services for planning a reform. Aspects of the newly designed infrastructure, along with specification of duties of the various human resources, and its relation with Iran’s Comprehensive Mental and Social Health Services (the SERAJ Program), will also be presented

Method: This is a study on service design and three methods of literature review, deep interview with stakeholders, and focused group discussions. In the literature review, national and international official documents, including official reports of the World Health Organization (WHO) and consultant field visits, were reviewed. Deep semi-structured interviews with 9 stakeholders were performed and results were gathered and categorized into 3 main questions were analyzed using the responsibility and effectiveness matrix method. The Final results were discussed with experts, during which the main five-domain questions were asked and the experts’ opinions were observed.

Results: In this study, the main gaps of the public mental health care (PHC) services in Iran were identified, which included reduction of risk factors for mental disorders, training the general population, early recognition and treatment of patients with mental disorders, educating patients and their families, and rehabilitation services. The new model was then proposed to fill these gaps focusing on increasing access, continuity of care, coordination in service delivery, and comprehensiveness of care. A mental health worker was placed besides general healthcare workers and general practitioners (GPs). Services were prioritized and the master flowchart for mental health service delivery was designed.

Conclusion: A reform was indeed necessary in the integrated mental health services in Iran, but regarding the infrastructure needed for this reform, including human and financial resources, support of the senior authorities of the Ministry of Health (MOH) is necessary for the continuity and enhancement of services. In this model, attention has been given to the principles of integrating mental health services into primary health care. Current experience shows that the primary health care system has been facing many executive challenges, and mental health services are not exclusion to this issue. Monitoring and evaluation of this model of service and efforts for maintaining sustainable financial resources is recommended to make a reform in this system and to stabilize it.

Key Words: Iran, Mental Health Services, Mental Disorders, Primary Health Care, Risk Factors

The Iranian National Mental Health Survey reported the prevalence of any mental disorder among the population aged 15 to 64 years in the given past 12 months of the survey to be 23.6% (1). This figure was 20.8% in men and 26.5% in women, showing a higher prevalence of mental disorders in women (1).

According to results of this survey, the prevalence of major depressive disorder was 12.7%, being considered as the most prevalent psychiatric disorder reported among the sample population (2).

In addition, higher rates were also seen in the unemployed compared to the employed, those divorced/separated/widowed compared to singles, urban residents compared to residents of rural areas, those with lower education compared to those with academic education, and people with low socioeconomic status compared to those with a higher socioeconomic status (3).

Before the implementation of the Iran Health Transformation Plan (HTP) in 2014, mental health services used to only be consisted of integrated mental health services into the primary health care system, inpatient psychiatric public or private facilities in general and psychiatric hospitals, some public outpatient psychiatry clinics, private offices of psychiatrists in mainly larger cities, and a number of counselling centers delivering mental health care in the public and private sectors (4). The majority of inpatient services were offered in mental hospitals and the minority were in psychiatric wards of general hospitals (5).

Integration of Mental Health Services into the Primary Healthcare System

The integration of mental health services into primary care in Iran was mentioned for the first time in the mid-1980s by a team of mental health professionals with experience in public health issues and approved of by senior authorities in the Ministry of Health (MOH). It started to be launched in the late-1980s (6). The integration process is considered as one of the major turning points in the flourishing and development of mental health services in Iran. The initial goals of the integration of mental health services into the primary health care system, mainly sought by delivering primary mental health care by general practitioners and multipurpose community health workers named "behvarz” in rural areas (7, 8), was as follows: increasing population access to basic mental health services with a focus on vulnerable target groups, promoting mental health services according to the local culture and social structures along with encouraging community participation, increasing public mental health awareness leading to an increased quality of life, and providing services for those severely traumatized (9).

Shahr-e Kord County, in the province of Chaharmahal-o Bakhtiari was selected along with Shahreza county of Isfahan as initial sites for implementing the pilot project. All health providers, mainly general practitioners and behvarzes (community health workers), were trained according to a routine basis on issues related to providing primary mental health services. Findings were analyzed in comparison to a control group. Results of studies published over a year showed trained behvarzes had been able to identify 63% of the mentally ill in their sample population. Evidence have shown only a small proportion of those identified were in need of specialized psychiatric services and 83% of their families had also reported to be satisfied with the services received. More positive attitudes toward mental illness had also been detected among trained health providers of the pilot intervention group (7, 8).

To reassure the reliability of the preliminary findings of the first pilot project (the integration of mental health into primary care), it was once again conducted as a pilot project in the Hashtgerd county of Tehran province (10). The results of the second pilot project gave the research team and the Ministry of Health officials the necessary experience and rationale for the countrywide extension of the integration process. The first international evaluation of this countrywide project was performed in 1995-1996, whose results along with other findings from the 2009 evaluation and the conclusive annual reports of two decades of the medical universities (1990-2010) clearly portrayed a successful integration process of mental health services into the primary health care setting with respect to service delivery and coverage in rural areas (11, 12, 13).

Integration of mental health services into the primary health care system has been an ongoing program. As mentioned previously, achievements were significant in rural areas (14) mainly due to infrastructures and well-organized human resources, but not as significant in urban areas, particularly in marginal urban zones (15). Consequently, although the integration of mental health services into the primary health care system was successful (12, 14), the need for upscaling in the program and bringing change to the infrastructures and settings was felt.

The major shift in the distribution of the Iranian population due to gradual migration from rural to urban areas throughout the past 4 decades, and the increase of the urban population proportion from 47% to more than 74% was one of the main reasons for the necessity of further modification of the program (16). This population shift has led to the rapid and disproportionate growth of small cities, transformation of rural areas into cities, and also marginal suburban space formation around larger cities (16, 17) in the absence of sufficient primary health care infrastructure and inadequate health care coverage.

Another major change that has taken place during the last decades is the shift of disease pattern from communicable diseases to noncommunicable diseases, including mental disorders, which has resulted in a significant change in the burden of diseases (18). According to the findings of the Global Burden Study, burden of mental disorders is prominent in Iran and unipolar depressive disorder shares 6.2% of the total DALYs (19). On the other hand, the National Mental Health Survey revealed that significant proportion of people with a reported mental disorder had not received any health services during the last 12 months of the study, revealing significant unmet needs (3).

The main objective of this study is to review the aspects of the current integrated public mental health services structure for the aim of planning for a reform. In this study, the different aspects of the newly designed infrastructure providing mental health services in urban and suburban areas along with clarification of duties of various human resources and workflows are presented and some implementation challenges are discussed.

Materials and Methods

This was a study on service design and three methods of literature review, deep interview with stakeholders, and focused group discussion were used.

a) Literature Review: The official reports of the World Health Organization were mainly used for this service development. In addition, the official report of the World Health Organization (WHO) field visit of PHC in Iran and other studies published in national and international journals were used as a source.

b) Semi-structured deep interview with nine stakeholders were performed (Table 1). The questionnaire consisted of three items and was sent before the interviews. After getting the interviews down on paper with help of thematic analysis, the results were compiled into 3 questions. The informants were chosen according to their position. The results were analyzed using the responsibility and effectiveness matrix.

Table 1.

List of the Stakeholders Interviewed

| Position | Number | Code |

|---|---|---|

| Director General of the Department for Mental Health and Substance Abuse of the MOH |

1 | 1 |

| Heads of the offices of the Department for Mental Health and Substance Abuse |

2 | 2 |

| Representatives of the related non-governmental scientific associations | 3 | 3 |

| Deputies for Health of two medical universities |

2 | 4 |

| Representative of the State Welfare Organization (SWO) |

1 | 5 |

c) Focused Group Discussions: The results obtained from the interviews were discussed in three consecutive meetings with experts and the 5 domains mentioned in Table 2 were finalized. The questions of the group discussion were sent for the experts along with the literature review results. In the beginning of the meeting, the objective of the meeting and the process was elaborated and each of the 5-domain questions were asked as one of the group discussion questions by the meeting coordinator and the experts all provided their opinions. The meeting coordinator kept minutes of the items proposed and completed it with listening to the voice recording of the discussion afterwards. The mean number of participants in the meeting were eight people in three meetings and each meeting lasted about 150 minutes. The composition of the experts was considered independent of their position; they consisted of 2 psychiatrists and two clinical psychologists and experts in designing the PHC system who were either community medicine specialists or epidemiologists, and two general practitioners with enough experience in this field.

Table 2.

Questions of the Deep Interview and Focused Group Discussions

| Deep Interview Questions |

|---|

| - How necessary is the integration of mental and social health and substance use prevention services into primary healthcare services? - From a technical point of view, how acceptable is this integration and how feasible is the budget allocation? - Among all mental health services, which one of them is the most necessary service? |

| Focused Group Discussion Questions |

| - What should be the main objective of the integration of mental and social health and substance use prevention services into primary healthcare services? - For reaching this objective, among all mental health services, which one of them is the most necessary services, how should this service be delivered and in other words, what is the core process of this service delivery? - Who should provide these new services? Is there a need for new service providers? Do the new service providers have the necessary capabilities for offering this service? - What are the duties of the new service providers or the new duties of the current service providers? In other words, what are the procedures followed by each service provider for any one client? - What are the necessities of this service provision, including infrastructure, financial resources, training modality and data management? |

Results

According to the evidence extracted from the literature review, increasing the access of the general population to mental health services, especially in marginal zones of urban areas, is an inevitable necessity. Based on the results of the interviews and focused group discussions on the subject of the current status of mental health services in Iran, there are gaps regarding 4 aspects of mental services as listed below:

Reducing environmental and social risk factors for mental disorders

Training the general population to receive service at public health centers to be empowered with skills that prevent mental disorders

Early recognition, referral, treatment and monitoring care for patients with mental disorders

Educating patients and providing social support for their families and rehabilitation services

Regarding the relatively high prevalence of mental disorders, the WHO stepwise approach to integrated mental health care services was adopted, cost management issues were considered, and referral points inside the PHC setting itself and to other settings were all determined.

In designing this model, the main objective of integration of mental health services into primary health care was to reduce risk factors, increase mental health literacy, empower the general population, detect and mange mental disorders, and increase satisfaction among service consumers.

Throughout the past three decades, the number of service providers needed in the field of physical health have been completed, but a scarcity in the number of human resources for providing mental health services existed. To fulfill this need at the primary healthcare level, 2 approaches were considered:

Using the existing human resources in the primary health care services to provide mental health care according to timing principles.

Employing new specialized human resources to provide mental health services at the primary healthcare level

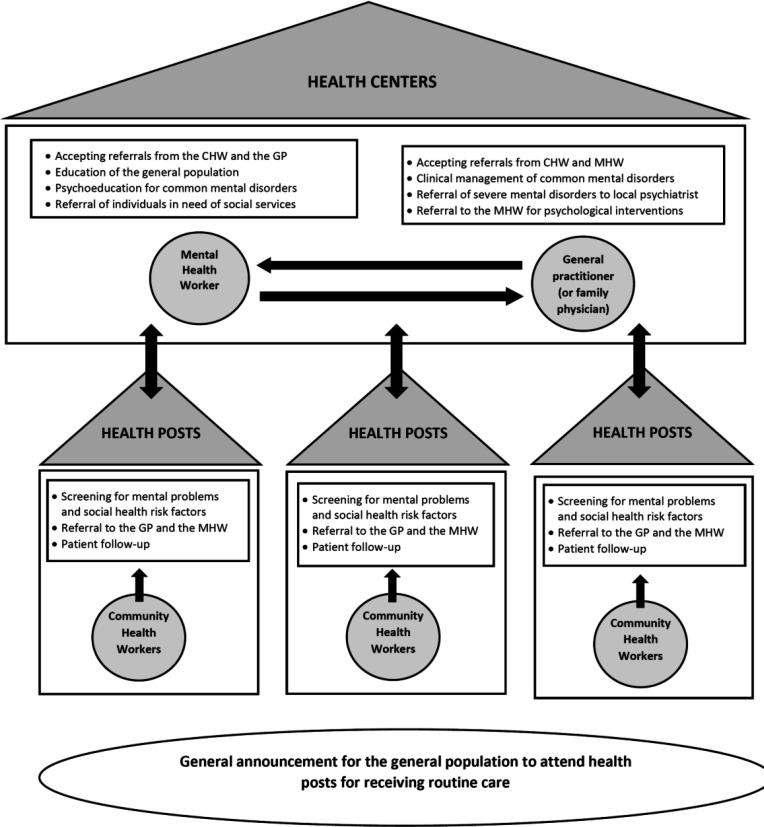

This model became a part of Iran’s Comprehensive Mental and Social Health Services (the SERAJ Program), which is under pilot implementation in some districts. In the initial model, the core service providers are the multipurpose community health care workers (Moragheb-e Salamat), the mental health care workers, and the general practitioners (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mental Health Service Providers in the PHC

(GP: general practitioner; MHW: mental health worker; CHW: community health worker)

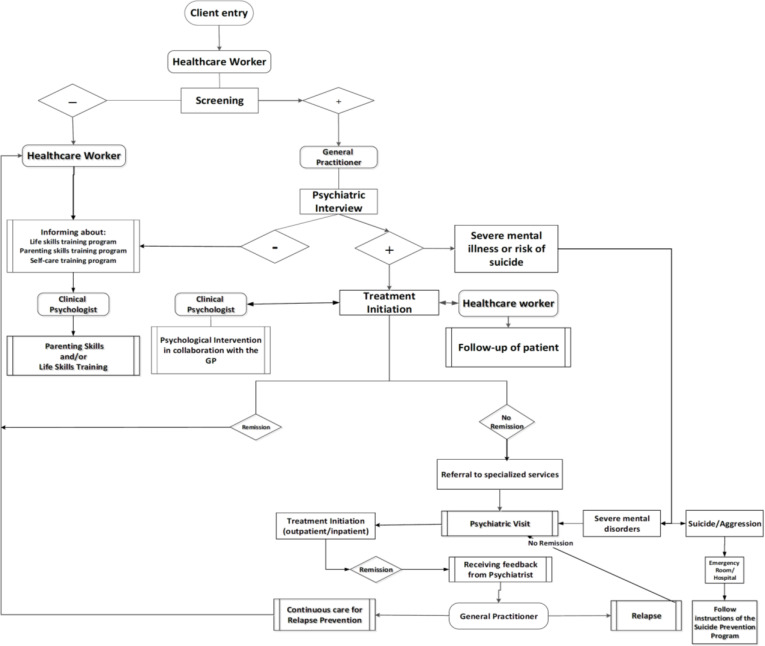

Community Health Workers are members of the health staff graduated with a bachelor’s degree of general health, family health, nursing, or midwifery. Community health workers, counterpart to the “Behvarzes” in rural areas, receive preservice training courses for elaboration of their duties, and are certified with the 12-hour training module for providing mental and social health and substance use services. Community health workers provide service at health posts located in urban and marginal zone urban areas; and according to the latest regulations, there is one health protector for every 2500 residents of an urban catchment area. One of the main duties that they are trained for is initial screening for mental health, substance use, and social health risk factors. According to results of the initial screening, services will be provided according to the master flowchart (Figure 2). Another duty of the community health worker is referring those in need to the mental health workers and general practitioners. They also have two more duties which is the follow-up of clients entering the service cycle according to the protocols or the GP orders, and informing clients and their families about the mental health services provided at health centers and health posts.

Figure 2.

Master Chart for Providing Mental Health Services in the PHC System

Mental Health Workers are the other newly-employed service providers in the HTP. They have been placed in the health team to monitor the shift of disease pattern and the increase in prevalence of mental disorders. With the support of senior authorities, one mental health worker now exists in the primary healthcare team for every 30000 -40000 residents of an urban catchment area. Mental health workers provide service at health centers located in urban and marginal zone urban areas.

Mental health workers are psychologists with a master’s degree in clinical psychology and are obligated to go through 150 hours of preservice training. Mental health workers have three main duties:

Educating the general population to empower target groups for primary prevention of mental disorders and mental health promotion: Programs include parenting skills training, life skills training, and self-care training.

Educating patients and at-risk individuals: Psychoeducation for those diagnosed with a common mental disorder, such as a depressive or anxiety disorder, empowering women and children who are victims of domestic violence. Brief psychological interventions for suicidal patients and telephone follow-up is also one of their duties.

Referral of individuals in need of social services is another duty of the mental health workers: This service was initially not completely structured but after the pilot implementation of Iran’s Comprehensive Mental and Social Health Services (the SERAJ Program), it was designed and conducted as one of the essential services for completing this service cycle. In this service, a social worker is placed among the human resources who interviews referred individuals and refers them for receiving social support form governmental and nongovernmental social service providers.

General Practitioners (GPs) are the other group of service providers of the primary health care system who provide mental and social health and substance use prevention services. The GPs deliver service mainly at health centers in urban and rural areas. In urban areas, there is a GP for every 10000 residents and in rural areas there is a GP for every 2500 residents. Although GPs receive two months of training in the medical student curriculum (one month as an extern and one month as an intern), 20 hours of preservice training and also in-service booster training sessions are provided for them. The Mental Health Guide for management of mental disorders for the general practitioners, which has been published by WHO, is used for this training. The GPs are trained to provide mental health care for psychiatric patients and to be develop awareness about the routine process of mental health services in the PHC, including referral for specialized services and routine follow-up services provided by other members of the health team.

In a routine situation, service provision starts from the point that a client enters the system after a public recall. This recall can be done via local health volunteers, local announcements, or text messages. The health care staff performs initial screening according to the clients’ age group and in parallel with the assessment in other health fields (Figure 2).

If the screening result is negative at this stage, the client will be given self-care training packages and also inform them about the group life skills, parenting skills, or self-care training sessions that they can sign up for.

If the screening result is positive, the client shall be referred to the GP for psychiatric interview.

If no mental disorder is detected by the GP, the client is sent back to the health care staff to be given exclusive training services for their age group and to be informed about the group life skills or parenting skills training sessions that they can sign up for (as above).

If the GP detects a common mental disorder, treatment is initiated according to the Mental Health Guide for management of mental disorders in the PHC by the GPs. In this case, all patients should be referred to the clinical psychologists in health centers for receiving concurrent psychoeducation and/or brief psychological interventions and to the healthcare staff for active follow-up.

Most of the cases go into remission after receiving a primary care treatment package and are then followed up by health care staff.

Some cases do not go into remission although treatment is initiated and are referred to the local/nearest psychiatrist with a referral form. The psychiatrist starts treatment until the patient goes into remission, which then can be referred back to the GPs for continuity of care and relapse prevention. During the continued care if the GPs face the relapse, they can refer the patient to the psychiatrist again.

If the GP detects psychosis, bipolar disorder or other severe mental illness, the patient shall be referred to the local/nearest psychiatrist with a referral form, because as a rule, all severe mental disorders should be confirmed by a psychiatrist for the first time and also the treatment should be initiated by psychiatrist; then, GPs can follow up the treatment.

If a severe aggression or a high risk for suicide is detected, the patient shall be referred to the nearest hospital with emergency services with a referral form.

Discussion

According to the findings of this study, a reform was necessary in the integrated mental health services in Iran and the main targets of this reform were reducing risk factors for mental disorders, increasing the mental health literacy in various population groups, early recognition and treatment of patients with mental disorders, increasing service coverage for this group of patients, and increasing satisfaction among service consumers. This need was met by keeping up with the WHO principles of integration of mental health services into the PHC and the experience of the Islamic Republic of Iran. A mental health worker was added as a new service provider to the health team and other essential and basic mental health services were placed as duties of the multipurpose general health care workers and general practitioners. One of the main necessities of reaching these objectives was access to specialized mental health service and social services for reducing risk factors for mental disorders and all of this was used in designing the three service packages of Iran’s Comprehensive Mental and Social Health Services (the SERAJ Program) (20).

The development of the new model of integration of mental health services into the primary health care system has expanded the diversity and access to these services in urban areas, especially marginal zones of urban areas (21). This was an effective response to one of the main concerns in this field, because before HTP, one of the main challenges of the primary health care system was poor population access to the basic and integrated mental health care provided in the existing PHC system (15).

According to WHO recommendations and definitions, the first structured level of care for patients, their families and the community is the primary health care system (22); therefore, the services described in this study have all been integrated into the primary health care system. Primary health care services have 4 functions: access to care, continuity of care, coordination of services, and comprehensiveness of services (23).

Access is an aspect of care which can be measured as an indicator of the functioning of a system. One of the indicators, which is usually used for the measurement of access to care, is access to a frontline health care worker, which is defined by the facilitation of setting an appointment with a service provider in the PHC (24). Evidence has validated the increase in access to care (21, 25).

Continuity of care and coordination of services are 2 other specifiers of a primary health care system, which has been considered in the new model of integrated mental health care. According to the service workflow (Figure 2), mechanisms for continuity of care and follow-up have been designed to preserve service and coordination of services. This is especially important in cases where a patient is diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder and enters the cycle of care. Jeannie et al (2008) in their study conducted in the Quebec province of Canada found that both specifiers of access to care and continuity of care can exist in an established service. Continuity of care consists of the continuity of care between a patient and the family physician and also between the family physician and the specialist. This latter is called coordinated continuity (26). Coordination of care means that the PHC has to integrate the referral pathways of the PHC in other services when a patient needs to receive specialized services. On average, between 13 to 20 percent of the clients of the PHC need to be referred for specialized services annually, and the burden of neglecting this portion of clients is quite significant. Studies show that coordinated continuity between the general practitioners and specialists will result in a reduction in hospital admissions and reduction in resource consumption (23, 27, 28). Efforts have been made to add the specialized service package for completion of the integrated mental health care in the designing of Iran’s Comprehensive Mental and Social Health Services (the SERAJ Program).

One important aspect of primary health care is its comprehensiveness. This is significant in countries that possess a sophisticated primary health care system. Comprehensiveness of care points out to the extent that the general practitioners can manage clinical issues without referral to a specialist and also how much the general practitioner is family-oriented and can provide services for all members of the family (29). This has been of utmost importance in the process of designing the new integrated model of mental health care. Efforts have been made to empower general practitioners to manage clinical issues without referral to a specialist and to enhance the family-oriented approach of the GP by filing medical records for a whole family under the supervision of a single GP.

Limitation

The integration of mental health care services in the PHC described in this study has been also facing limitations and challenges. One of these challenges is reaching an operational method to preserve the trained human resources of the system and preventing their drop-out after they have finished their mandatory service period. In other words, the heath system in some provinces has been largely dependent on temporary working human resources that bring about problems to the system when leaving the system. Our experience shows that one of the main pillars of success in service delivery to target groups that can be counted on for future planning is permanent human resources. The challenge of drop-out of trained and experienced human resources is one of the previously detected challenges of the primary health care system, mainly related to the general practitioners (15), which has extended to the employment of mental health workers after HTP (21).

Another challenge is the determination of the workload of mental health workers. Estimations had predicted that one mental health worker is needed for every 12500 residents of an urban catchment area (30). Budget shortage issues led to the employment of one mental health worker for every 30000 to 40000 residents of an urban catchment area. This challenge was initially managed by cancelling some of the duties of the mental health workers. However, following the increase in service coverage and the need for adding back some of the services that had previously been cancelled, more mental health workers should be employed in the future to deliver the necessary services previously planned for.

Another serious challenge that can threaten the sustainability and stability of this new mental health care model is poor access to sustainable financial resources. To overcome this challenge, efforts have been made to advocate for more financial resources that rely on evidence such as cost-effectiveness studies and this issue can be dealt with effectively upon the approval of senior authorities.

Conclusion

The reform of the integrated mental health services in the primary health care system is technically feasible, but support is needed to develop and sustain the trained human resources, financial resources, and software infrastructure to reach previously-planned objectives. In this model, attention has been given to the principles of integrating mental health services into primary health care services. Current experience shows that the primary health care system has been facing many executive challenges and mental health services are not an exclusion to this issue. Considering the circumstances, monitoring and evaluation should be done and service costs and sustainable budgets should be planned to improve this model of service.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all those who helped us in the various stages of this study.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Sharifi V, Amin-Esmaeili M, Hajebi A, Motevalian A, Radgoodarzi R, Hefazi M, et al. Twelve-month prevalence and correlates of psychiatric disorders in Iran: the Iranian Mental Health Survey, 2011. Arch Iran Med. 2015;18(2):76–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amin-Esmaeili M, Motevalian A, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Hajebi A, Sharifi V, Mojtabai R, et al. Bipolar features in major depressive disorder: Results from the Iranian mental health survey (IranMHS) J Affect Disord. 2018;241:319–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahimi-Movaghar A, Sharifi V, Motevalian A, Amin-Esmaeili M, Hajebi A, Radgoodarzi R, et al. National Mental Health Survey-2011. First Edition. Tehran: Ministry of Health & Medical Education of the Islamic Republic of Iran; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Islamic Republic of Iran. Tehran: Ministry of Health & Medical Education; 2004. Department for Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Situational Analysis of Mental Health Services in Iran. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Islamic Republic of Iran. Deputy for Therapeutic Affairs. Psychiatric Beds in the Health System of Iran. Tehran: Ministry of Health & Medical Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abhari M. Descriptive Report on Mental Health Services and Integration of Mental Health into the Primary Health Care in Savojbalagh. IJPCP. 2000;4(3):29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassanzadeh M. Investigating the Integration of Mental Health Services into the primary Health Care System of Shahreza. Darou va Darman Monthly. 1992;10(110):23–27. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shahmohammadi D. Comprehensive Report on Mental Health Integration into PHC in Rural Areas of Shahrekord. Tehran: Center for Disease Control & Prevention of the Ministry of Health & Medical Education of the Islamic Republic of Iran; 1992. . (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahmohammadi D, Bagheri Yazdi SA, Palahang H. Nationwide Integration of Mental Health into Primary Health Care in Iran: Case Summary for WHO. Tehran: Majd Publications; 1994. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolhari J, Mohit A. Integration of mental health into primary health care in Hashtgerd. IJPCP. 1995;2(1&2):16–24. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohit A, Shahmohammadi D, Bolhari J. Independent evaluation of Iranian National Mental Health Program. IJPCP. 1995;3(3):4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolhari J, Ahmadkhaniha H, Hajebi A, Yazdi SAB, Naserbakht M, Karimi-Kisomi I, et al. Evaluation of mental health program integration into the primary health care system of iran. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology. 2012;17(4):271–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bagheri Yazdi, SA Bashti S Islamic Republic of Iran. Comprehensive report of national mental health programs of Iran after 20 years of experiences. Tehran: Ministry of Health & Medical Education; (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohit A, Shahmohammadi D, Bolhari J. Independent evaluation of Iranian National Mental Health Program. IJPCP. 1995;3(3):4–16. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization; World Organization of Family Doctors. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Planning and Budget Organization. Analysis of Population and Housing Census Results. Deputy of Economic Affairs and Coordination. Tehran: 2017. (Persian) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karimi A. An Analysis on the spatial pattern, dimensions and related factors to urbanism growth of contemporary in Iran (Emphasizing on development and livelihood indexes) 2018;6(3):605–27. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forouzanfar MH, Sepanlou SG, Shahraz S, Dicker D, Naghavi P, Pourmalek F, et al. Evaluating causes of death and morbidity in Iran, global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2010. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(5):304–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forouzanfar MH, Sepanlou SG, Shahraz S, Dicker D, Naghavi P, Pourmalek F, et al. Evaluating causes of death and morbidity in Iran, global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors study 2010. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17(5):304–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Damari B, Alikhani S, Riazi-Isfahani S, Hajebi A. Transition of Mental Health to a More Responsible Service in Iran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(1):36–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naserbakht M, Taban M. Evaluation of integration of mental health services into the primary healthcare system. Tehran: Ministry of Health & Medical Education; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. International Conference on Primary Health Care; 1978-09-06. Alma-Ata: USSR; 1978. Declaration of Alma-Ata. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haggerty J, Burge F, Lévesque JF, Gass D, Pineault R, Beaulieu MD, et al. Operational definitions of attributes of primary health care: consensus among Canadian experts. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5(4):336–44. doi: 10.1370/afm.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammadi E, Oliaeemanesh AR, Majd-Zade R, Kabir MJ, Atri m, Asgari K, et al. Effects of the Health Transformation Plan (HTP) on implementation process, rules and regulations of basic health insurance organizations in Iran. Hakim Health system research. 2019;21(4):255–65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haggerty JL, Pineault R, Beaulieu MD, Brunelle Y, Gauthier J, Goulet F, et al. Practice features associated with patient-reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(2):116–23. doi: 10.1370/afm.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talbot-Smith A, Gnani S, Pollock AM, Gray DP. Questioning the claims from Kaiser. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(503):415–21. discussion 22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feachem RG, Sekhri NK, White KL. Getting more for their dollar: a comparison of the NHS with California's Kaiser Permanente. Bmj. 2002;324(7330):135–41. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7330.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Or Z. Exploring the Effects of Health Care on Mortality across OECD Countries. Labour Market and Social Policy Occasional Papers no. 46. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Damari B, Alikhani S, Riazi-Isfahani S, Hajebi A. Transition of Mental Health to a More Responsible Service in Iran. Iran J Psychiatry. 2017;12(1):36–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]