Abstract

Airway sensory nerves detect a wide variety of chemical and mechanical stimuli, and relay signals to circuits within the brainstem that regulate breathing, cough, and bronchoconstriction. Recent advances in histological methods, single cell PCR analysis and transgenic mouse models have illuminated a remarkable degree of sensory nerve heterogeneity and have enabled an unprecedented ability to test the functional role of specific neuronal populations in healthy and diseased lungs. This review focuses on how neuronal plasticity contributes to development of two of the most common airway diseases, asthma and chronic cough, and discusses the therapeutic implications of emerging treatments that target airway sensory nerves.

Keywords: asthma, cough, nerve, neurotrophin, eosinophil, P2X3, neurokinin

Introduction

Airway sensory nerves have essential roles in maintaining lung health and regulating airway physiology. Sensory nerves express a wide variety of receptors to detect inhaled and endogenous chemical and mechanical stimuli, and relay their input to second order neurons in the brainstem (McGovern and Mazzone, 2014). Brainstem neurons subsequently provide input to higher cortical pathways and to brainstem motor neurons that regulate reflexes such as breathing, cough, and bronchoconstriction. Sensory nerves also release neuropeptides, which have antimicrobial and immune modifying functions (McGovern et al., 2018). Recent advances have uncovered a host of homeostatic and adaptive sensory neuronal processes that maintain lung health or alternatively, contribute to the pathogenesis of disease. In this review, we discuss sensory nerve function in healthy lungs and explore how neuronal plasticity contributes to development of two of the most common airway diseases, asthma and chronic cough. Recent advances in therapies that target sensory nerves and new experimental techniques for studying nerve function will also be addressed.

Sensory Nerve Structure and Function in Healthy Airways

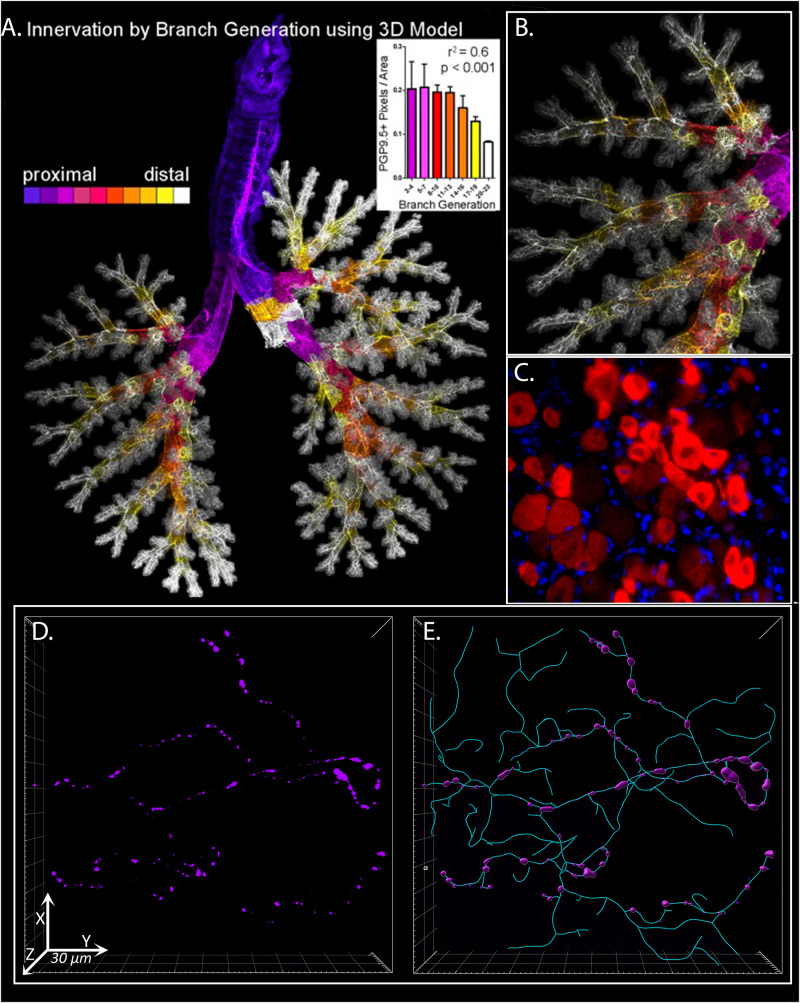

Airway sensory nerves primarily originate in vagal ganglia at the base of the skull, with a small portion also supplied by dorsal root ganglia along the spine. Sensory axons terminate at all levels of airways, including in primary and secondary bronchi below and within the airway epithelium, smooth muscle, glands, and autonomic ganglia (Belvisi, 2002), and within the alveolar airspace distal to airways where they surround the capillary bed (Watanabe et al., 2006; Figure 1). Clusters of sensory nerve endings are particularly dense at branch points and in the dorsal aspects of airways (Scott et al., 2013).

FIGURE 1.

3D Analysis of Sensory Innervation of the Lung. Mouse and human airway nerves are labeled and imaged using immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. (A) Flattened image of mouse lungs with nerves identified using antibodies against the pan-neuronal protein PGP9.5. Color-coding is based on airway generation from proximal (purple) to distal (white). Nerve density in each generation was calculated (inset). (B) Higher magnification image of airway shown in (A). (C) Mouse vagal ganglion with purinergic P2X3 receptor expression in red. (D) Human airway neuronal substance P expression (purple) in bronchoscopic airway biopsy from a patient with chronic cough. (E) Computer modeling and morphometric analysis of total sensory innervation based on PGP9.5 (cyan) and distribution of substance P (purple) in image from (D). (A,B) Scott et al. (2014) reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright© 2021 American Thoracic Society. All rights reserved. The American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society. (D,E) From ref. Shapiro et al. (2021) adapted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright© 2021 American Thoracic Society. All rights reserved. The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine is an official journal of the American Thoracic Society. Readers are encouraged to read the entire article for the correct context at https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/full/10.1164/rccm.201912-2347OC. The authors, editors, and The American Thoracic Society are not responsible for errors or omissions in adaptations.

Sensory neurons can be classified in a variety of ways based on their primary function, conduction speed, protein and peptide expression, or airway location. However, it is important to note that no single classification scheme fully encapsulates all these variables and that considerable overlap exists between the sensory properties of many nerves (Mazzone and Undem, 2016). Most commonly, sensory nerves are subdivided based on their ability to detect mechanical or chemical stimuli, termed mechanoreceptors or chemoreceptors, respectively. Mechanoreceptor are typically myelinated Aδ nerve fibers that are exquisitely sensitive to touch. Chemoreceptors (also termed nociceptors) are mostly unmyelinated fibers that are generally quiescent in healthy lungs, but express a wide array of receptors and ion channels capable of detecting inhaled or endogenous noxious compounds (Mazzone and Undem, 2016). Other airway afferent nerves include slowly adapting and rapidly adapting intrapulmonary mechanoreceptors that do not evoke cough directly, but can modify the function of cough pathways. Collectively, these sensory afferents contribute to the coordination of normal physiologic activity such as regulation of bronchoconstriction, breathing, and expulsion of foreign materials by stimulation of cough.

Sensory nerve afferents transmit information centrally to the solitary nucleus and paratrigeminal tract in the brainstem, which then relay signals to higher order neurons involved in cognition and sensation in the cerebral cortex, as well as other brainstem centers involved in unconscious processing of airway stimulation, including the respiratory central pattern generator and the nucleus ambiguus (Canning, 2009). Sensory input into the respiratory central pattern generator coordinates involuntary coughing, whereas sensory input to pre-ganglionic cholinergic parasympathetic nerves in the nucleus ambiguus triggers reflex bronchoconstriction (Costello et al., 1999). Reflex bronchoconstriction occurs when parasympathetic efferent axons contained within the vagal nerves stimulate release of acetylcholine from post-ganglionic parasympathetic nerves in the trachea and primary bronchi. Acetylcholine activates M3 muscarinic receptors on airway smooth muscle to trigger contraction and airway narrowing. Acetylcholine also activates prejunctional inhibitory M2 muscarinic receptors on airway parasympathetic nerves, which limit further acetylcholine release. This inhibitory feedback mechanism, coupled with inhibition of sensory reflexes by input from slow adapting mechanoreceptor neurons, helps regulate the degree of bronchoconstriction (Minette and Barnes, 1988; Fryer and Jacoby, 1992). Reflex bronchoconstriction occurs in response to a variety of stimuli, such as inhaled methacholine (Wagner and Jacoby, 1999), histamine (Boushey et al., 1980), cold air (Sheppard et al., 1982), allergens (Gold, 1973), and exercise (Simonsson et al., 1972), and is highly conserved in both humans and animal models.

In addition to the cholinergic nerve reflex, bronchodilatory efferent non-cholinergic parasympathetic and sympathetic neurons are also activated by sensory nerves, however, both their structure and function vary greatly between species. In humans, non-cholinergic parasympathetic nerves release peptides and neurotransmitters, including nitric oxide and vaso-intestinal peptide (VIP), which induce airway relaxation to counterbalance acetylcholine’s contractile effects (Richardson and Beland, 1976; Ward et al., 1995; Kesler et al., 2002). In contrast, airway sympathetic nerves are largely absent in humans, but present in many other animal species including dogs and guinea pigs (Richardson and Beland, 1976; Kummer et al., 1992). Sympathetic nerves induce airway relaxation via release of norepinephrine that activates beta receptors on smooth muscle. In humans, beta receptor activation occurs through effects of systemic norepinephrine rather than through airway sympathetic nerves specifically.

Sensory activation also leads to direct release of mediators locally within tissues via an axon reflex (Mazzone, 2005). Axon reflexes take place within a single sensory neuron, do not require central input, and involve direct release of small signaling peptides that are synthesized and secreted by sensory nerves. These neuropeptides comprise a large class of biologically active small proteins, including substance P, CGRP, and VIP among others, that modify nerve function, stimulate production of neuronal growth factors, and recruit inflammatory cells to airways (McGovern et al., 2018).

Neurobiological Origins of Chronic Cough

Cough is a protective response that maintains healthy lungs by clearing pathogens, mucus, and environmental particles from the airways. Cough is also a common feature of over 100 different diseases, including most commonly, asthma, gastroesophageal reflux, rhinitis/upper airway cough syndrome, and during respiratory viral infections. In some cases, cough persists, lasting months or even years and no longer serves a physiologic role (Morice et al., 2020). Chronic cough is defined as any cough lasting more than 8 weeks. A common feature of patients with chronic cough is enhanced sensitivity to both tussive and non-tussive stimuli that develops via multiple mechanisms that contribute to neuronal sensitization, including increased sensitivity and expression of specific nociceptors on neurons, de novo expression of nociceptors by non-nociceptor neurons, increased epithelial nerve density, and increased release of endogenous cough-triggering molecules in airways. A variety of inflammatory mediators contribute to nerve sensitization, including leukotrienes, bradykinin, neurokinins, prostanoids, lipid mediators, and adenosine triphosphate, among others (Chung et al., 2013). Exposure to allergens, virus infection, cigarette smoke, ozone, and other insults, stimulates production and release of these mediators, sensitizing nerves and increasing cough frequency. Neuronal sensitization is one part of a spectrum of airway remodeling in chronic cough that includes airway epithelial damage, basement membrane thickening and in some cases, an influx of inflammatory cells such as mast cells or eosinophils (Morice et al., 2007). Just as inciting events and inflammatory mediators differ between diseases, so too does an individual’s response to various tussive agents. As a recent study demonstrated, patients with COPD and chronic idiopathic cough had similar cough sensitivity to inhaled capsaicin, but drastically differed in their sensitivity to inhaled prostaglandin E2 (Belvisi et al., 2016). Thus, different diseases exhibit unique cough neurophenotypes that manifest collectively as cough hypersensitivity. The following sections focus on specific features of neuronal sensitization.

Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) Channels

TRP channels are calcium-permeable ion channels that trigger sensory nerve activation and are considered canonical cough receptors due to their ability to trigger cough in response to a diverse set of tussive stimuli. Foremost among these receptors are TRPV1, whose ligands include the active ingredient in chili powder, capsaicin, and citric acid; TRPA1, which responds to noxious compounds such as cinnamaldehyde, acrolein, and formalin; and TRPV4 which is activated by arachidonic acid and hypotonic solutions. Changes in both TRP expression and activity have been documented in chronic cough. For example, TRPV1 expression is increased in bronchial biopsies from patients with chronic cough (Groneberg et al., 2004; Mitchell et al., 2005), while de novo TRPV1 expression occurs in low-threshold mechanoreceptors after allergen exposure and virus infection in guinea pigs (Lieu et al., 2012; Zaccone et al., 2016) and after allergen exposure in rats (Zhang et al., 2008b, a). Similar changes in neuronal TRPV1 expression are induced by exposing isolated tracheas to the neurotrophin brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Lieu et al., 2012). Tobacco smokers, patients with asthma, and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have increased responsiveness to TRPV1 agonists citric acid and capsaicin (Belvisi et al., 2016), supporting a role for TRP channels in cough hypersensitivity.

Several TRP channel antagonists have been developed for treatment of chronic cough and have proved quite effective at blocking cough responses to specific tussive agents (Khalid et al., 2014; Preti et al., 2015; Bonvini et al., 2016; Belvisi et al., 2017). However, these antagonists against TRPV1, TRPV4, TRPA1, and others have uniformly failed to improve spontaneous cough frequency or inhibit the urge to cough in chronic cough patients in clinical trials. These discordant outcomes suggest that changes in specific TRP receptors do not fully explain the neuronal mechanisms underlying cough hypersensitivity.

Sensory Neuropeptides

Neurokinins, of which substance P is the most studied, are a large group of neuroactive peptides that have been associated with cough in several animal models, most notably in guinea pigs. Substance P, in particular, is constitutively expressed by small diameter nociceptive sensory nerves and is released via an axon reflex, causing both bronchoconstriction and potentiation of citric acid-induced cough (Moreaux et al., 2000; Otsuka et al., 2011; McGovern and Mazzone, 2014). Substance P expression can be induced de novo in larger diameter mechanoreceptors after allergen exposure and virus infection in guinea pigs (Carr et al., 2002; Myers et al., 2002), suggesting changes in neuropeptide content may contribute to nerve sensitization in chronic cough. Furthermore, blocking substance P receptors, termed neurokinin receptors, attenuates cough in guinea pigs (Girard et al., 1995).

Despite these promising results, substance P’s role in human cough remains unclear. Substance P was increased in peripheral blood of adults with chronic cough (Otsuka et al., 2011), but not in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from children with cough (Chang et al., 2007). In bronchial biopsy specimens from adults with chronic cough, airway sensory nerve substance P expression was similar between chronic cough and healthy patients (O’Connell et al., 1995; Shapiro et al., 2021). Moreover, initial clinical trials of substance P receptor antagonists failed to improve cough frequency in patients with chronic cough (Fahy et al., 1995), adding to doubts that neuropeptides and substance P in particular are important for sensory nerve-mediated tussive responses. However, recent studies using newer neurokinin receptor antagonists that block receptors in both the central and peripheral nervous system reported a reduction in cough frequency in chronic cough patients (Smith J. et al., 2020), leading to renewed interest in this approach. Indeed, these findings suggest that substance P’s role in cough involves modulation of central neurotransmission between peripheral sensory nerves and second order brainstem neurons. This possibility, and the potential for targeting central effects of substance P using brain penetrant compounds, is the focus on ongoing studies.

Neurotrophins

Neurotrophins encompass a large family of neuroactive molecules that influence sensory nerve development and acutely alter neuronal activity. Two of the most studied are nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which are released by inflammatory cells and by airway epithelium in the setting of allergen exposure, virus infection, and other insults (Prakash and Martin, 2014; Skaper, 2017). Both NGF and BDNF sensitize cough responses to TRPV1 agonists in vivo by increasing neuronal TRPV1 expression and by acutely enhancing TRPV1 channel activity (Ji et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2005; Zhu and Oxford, 2007). NGF also enhances TRPA1 signaling (Clarke et al., 2017) and stimulates neuropeptide expression in sensory neurons (Hunter et al., 2000; Dinh et al., 2004). Moreover, mice that produce elevated levels of nerve growth factor from airway epithelium exhibit increased sensory nerve density (Hoyle et al., 1998). Increased nerve density is also present in mice exposed to allergen in early life due to production of another neurotrophin, neurotrophin-4 (Patel et al., 2016). Thus, a variety of neurotrophins may influence nerve phenotype, growth and function in the setting of airway inflammation. In adults with chronic cough, increased airway epithelial innervation is observed (Shapiro et al., 2021), although whether these changes occur during specific time periods of development and whether neurotrophins are involved has not been established.

Purinergic Receptors

A subset of vagal sensory neurons express the purinergic receptor P2X3 (Wang et al., 2014). P2X3 binds ATP, an important endogenous alarmin released by both structural and inflammatory cells at times of cell stress, and triggers cough in humans and animals (Belvisi and Smith, 2017; Turner and Birring, 2019). Patients with chronic cough exhibit increased cough sensitivity to inhaled ATP (Fowles et al., 2017), suggesting receptor sensitization and/or changes in expression may occur. Increased extracellular ATP has also been reported in lung diseases that are associated with cough hypersensitivity, including asthma and COPD (Idzko et al., 2007; Lommatzsch et al., 2010), suggesting that increased P2X3 activation contributes to excessive cough in these disorders. Interestingly, a recent study also reported that TRPV4 stimulates neuronal ATP release (Bonvini et al., 2016). Thus, different cough receptors may work synergistically to increase cough frequency, although the clinical importance of this synergism is unclear given that a TRPV4 antagonist failed to improve cough frequency in a recent clinical trial (Ludbrook et al., 2019).

Clinical interest in P2X3 as a therapeutic target has recently risen due to trials showing the P2X3 antagonist gefapixant significantly reduced spontaneous cough frequency in patients with refractory or unexplained chronic cough (Abdulqawi et al., 2015; Morice et al., 2019; Smith J. A. et al., 2020). While this approach clearly offers the most promising treatment opportunity for chronic cough to date, it is notable that not all patients responded to gefapixant, suggesting there remains a need for improved neurophenotyping to better identify subsets of patients who are likely to respond to treatment. Indeed, gefapixant did not prevent cough provoked by inhaled capsaicin, indicating that TRPV1 and P2X3 induced coughing represent distinct mechanisms that need additional clinical characterization.

Neuro-Immune Interactions in Asthma

Asthma is an inflammatory airway disease characterized by increased bronchoconstriction and airway hyperreactivity, where inhaled irritants provoke excessive airway contractions (Busse, 2010). Both increased bronchoconstriction and airway hyperreactivity are manifestations of sensory nerve dysfunction. Thus, like chronic cough, asthma can be viewed as neuropathic disease. Airway inflammatory cells in asthma, of which eosinophils are the most common in approximately two-thirds of patients, increase sensory nerve activation by altering nerve phenotype and increasing nerve density, and by provoking release of mediators that stimulate nerves directly, such as prostaglandins, histamine, thromboxanes, and tachykinins (Drake et al., 2018a). Eosinophils preferentially migrate to nerves due to neuronal expression of eosinophil chemoattractant factors, such as eotaxin-1, which binds to CCR3 to stimulate eosinophil chemotaxis (Griffiths-Johnson et al., 1993). In guinea pigs, neuronal eotaxin-1 expression is increased after allergen challenge and eosinophil migration to nerves and nerve-mediated airway hyperreactivity is blocked by CCR3 antagonists (Fryer et al., 2006) and by corticosteroids (Nie et al., 2007). Eosinophils also cause dysfunction of parasympathetic nerves after exposure to the environmental pollutant ozone (Yost et al., 2005) and after respiratory virus infections (Nie et al., 2009), both of which are common triggers for asthma exacerbations. In guinea pigs, blocking TNF-α after ozone exposure or virus infections prevents eosinophil recruitment to nerves and nerve-mediated airway hyperreactivity (Nie et al., 2011; Wicher et al., 2017). Thus, physical interactions between eosinophils and airway nerves are critical for development of nerve dysfunction in multiple models of asthma.

Epithelial Sensory Nerve Density

Airway remodeling is a hallmark of longstanding asthma. Changes include airway smooth muscle hypertrophy, mucus gland hypersecretion, thickening of the basement membrane and epithelial metaplasia. Sensory nerves are no exception. Recently, airway epithelial sensory nerves were imaged using confocal microscopy in bronchial biopsies from patients with asthma (Drake et al., 2018b). In asthmatic samples, sensory nerves density was significantly increased compared to patients without airway disease. These changes were particularly apparent in patients with higher eosinophil counts and were associated with worse lung function and increased sensitivity to environmental irritants, suggesting nerve density contributes to classic features of the asthma phenotype. Similar increases in nerve density were present in transgenic mice with airway eosinophilia due to over-expression of interleukin-5 (IL-5), which promotes eosinophil recruitment and survival, and increased nerve density potentiated reflex bronchoconstriction triggered by inhaled serotonin (Drake et al., 2018b). Mice that were eosinophil-deficient did not develop airway hyperinnervation nor airway hyperreactivity, highlighting the important role for eosinophils in sensory neuronal remodeling.

Sensory Neuropeptides

Sensory neuropeptides are increased in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with asthma (Nieber et al., 1992), and increased substance P-expressing sensory fibers are present in airway epithelium in bronchial biopsies from eosinophilic asthmatics (Drake et al., 2018b). In animal models, airway inflammation, and eosinophils in particular, stimulate neuropeptide expression in airways. For example, neuronal substance P expression is increased after allergen (Fischer et al., 1996) and ozone exposure (Wu et al., 2001) and in the setting of respiratory virus infections in guinea pigs (Carr et al., 2002). While these changes are clearly a consequence of inflammation, evidence suggests neuropeptides promote inflammation as well. Eosinophils migrate along a neuropeptide concentration gradient in vitro (Dunzendorfer et al., 1998), which may contribute to disproportionate numbers of eosinophils found clustered around airway nerves in asthmatics who suffered from fatal bronchoconstriction (Costello et al., 1997). Neuropeptides stimulate eosinophil entry into tissue by upregulating the adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and E-selectin on vascular endothelium (Smith et al., 1993; Nakagawa et al., 1995; Quinlan et al., 1999), resulting in enhanced eosinophil migration into airway parenchyma, and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on nerves (Sawatzky et al., 2002), enabling eosinophil binding directly to nerves via their cognate receptors, VLA-4 and CD11b, respectively. In turn, blocking VLA-4 prevents eosinophil-mediated nerve dysfunction after allergen inhalation in guinea pigs (Fryer et al., 1997). Ligation of adhesion molecules on eosinophils has multiple effects on eosinophil function including release of leukotrienes and highly charged granule proteins eosinophil cationic protein and eosinophil peroxidase, which activate nerves directly and lower their activation threshold for other stimuli (Gu et al., 2008, 2009). Thus, neuropeptides and eosinophils interact to form a positive feedback loop, where neuropeptides and eosinophils cooperatively increase each other’s expression and activity, resulting in increased nerve sensitivity.

TRP Channels

TRP channel agonists, such as capsaicin, induce bronchoconstriction in the absence of airway inflammation (Lalloo et al., 1995). In severe asthma, TRPV1 expression is increased (McGarvey et al., 2014) and TRPV1 responses are potentiated (Belvisi et al., 2016). In guinea pigs, exposure to ovalbumin antigen acutely sensitizes sensory nerve responsiveness to capsaicin while also decreasing the force necessary to activate mechanoreceptor neurons (Lieu et al., 2012). Inhalation of inflammatory mediators such as bradykinin and prostaglandin E2 similarly sensitized responses to capsaicin in healthy volunteers (Choudry et al., 1989), while eosinophil-derived cationic granule proteins increased isolated sensory nerve responses to capsaicin in vitro (Gu et al., 2008, 2009).

Like neuropeptides, TRP channels may also be involved in airway inflammation. Genetic silencing of TRPV1-expressing neurons in mice attenuated antigen-induced airway hyperreactivity, while stimulation of TRPV1-expressing neurons potentiated antigen-induced airway hyperreactivity in vivo (Trankner et al., 2014). Similar results were observed with TRPA1, where loss of TRPA1 function due to genetic knockdown or pharmacologic inhibition attenuated neuropeptide release and prevented airway hyperreactivity in mice (Caceres et al., 2009). Therefore, TRP channels may serve a key role in the interactions between neurons and airway inflammation that leads to hyperreactive asthmatic airway responses.

Neurotrophins

Neurotrophins, including NGF, BDNF, and neurotrophin 3, are increased in asthma and these factors may have important roles in neuroplasticity (Bonini et al., 1996; Virchow et al., 1998; Olgart Hoglund et al., 2002; Watanabe et al., 2015). A variety of structural cells release neurotrophins, including airway neurons, smooth muscle and epithelium (Kistemaker and Prakash, 2019), which is a rich source of neurotrophins and is also the site of sensory nerve remodeling in both cough and asthma (Drake et al., 2018b; Shapiro et al., 2021). Inflammatory cells, such as mast cells and eosinophils also release neurotrophins, and in the case of allergic asthma, eosinophil-specific NGF release is increased (Raap et al., 2008b).

Neurotrophins activate tropomyosin-related tyrosine kinase (Trk) receptors on sensory nerves to induce structural, phenotypic and functional changes in nerve signaling. Specifically, NGF over-expression in transgenic mice increases airway nerve density (Hoyle et al., 1993), increases substance P expression in sensory ganglia (Dinh et al., 2004) and stimulates phenotypic switching in non-nociceptive fibers toward a nociceptor phenotype (Hunter et al., 2000). NGF also prolongs eosinophil survival (Raap et al., 2008a) and causes airway hyperreactivity in vivo (Verbout et al., 2007). In turn, blocking NGF, either with pharmacologic antagonists or by genetic silencing, attenuates airway hyperreactivity (Verbout et al., 2007; Verhein et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2014). Similarly, BDNF induces TRPV1 expression de novo in sensory neurons and increases their responsiveness to TRPV1 agonists (Lieu et al., 2012), while genetic modification of the BDNF receptor, TrkB, attenuates airway hyperreactivity and reduces nerve density (Aven et al., 2014). The effects of blocking these neurotrophins and receptors await further testing in humans.

Sensory Neuronal Plasticity During Development

There is increasing evidence that critical developmental time-periods exist where sensory nerves are particularly vulnerable to the effects of various exposures. For example, exposure in very early life to ozone or allergen increased airway epithelial sensory innervation in rhesus monkeys (Kajekar et al., 2007), while ozone exposure in the early post-natal period in rats similarly produced increased epithelial nerve density (Hunter et al., 2010). Infections in early life by viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are also implicated in alternations in nerve development. RSV increases airway hyperreactivity in children and has been shown experimentally to alter neuronal control of bronchoconstriction in ferrets (Larsen and Colasurdo, 1999). RSV increases NGF, which may initiate the developmental effects on airway nerves that have long-lasting implications for airway function.

The prenatal period, during which exposures can influence airway nerve development in the fetus, poses another important time period for asthma risk. Evidence of these effects includes the observations that airway hyperreactivity can be detected at birth (Haland et al., 2006) and that children born to parents with asthma are at increased risk of developing asthma (Paaso et al., 2014). Furthermore, maternal asthma confers greater risk than paternal asthma (Kelly et al., 1995), supporting the concept that asthma risk is related in part to in utero exposures and not solely due to shared genetics or environmental exposures after birth.

Recently, Lebold et al. (2019) demonstrated that wild-type offspring of interleukin-5 (IL-5) transgenic mice, who are exposed to high levels of the eosinophil maturation cytokine IL-5 in utero, exhibit increased airway sensory innervation and reflex bronchoconstriction in later life. These effects are mediated by IL5’s induction of fetal eosinophilia. Importantly, these mice also have an exaggerated inflammatory response to allergen exposure in adulthood that results in airway hyperreactivity so severe that inhaled serotonin provokes lethal bronchoconstriction. Similar exposure to IL-5 and other asthma-related cytokines may occur in human fetuses born to asthmatic mothers as well. Thus, prenatal programming due to exposures in utero may create a unique trajectory that influences neuronal development and inflammatory responses to allergen in later life.

Novel Methods for Studying Airway Nerves

Recent studies have illuminated a remarkable degree of heterogeneity in airway sensory nerve expression, structure and function. For example, Kupari et al. (2019) demonstrated using single cell RNA sequencing that 18 transcriptionally distinct sensory nerve subtypes exist within the vagal ganglia. Individual receptors and neuropeptides were often expressed by multiple subtypes despite each subset having fundamentally different functions in the airway. These results highlight the limitations of categorization efforts that grouped nerves based solely on protein expression and underscore the need for linking comprehensive expression profiling to nerve function. Indeed, even relatively rare nerve subtypes may provide prominent input for control of airway function, as is the case with MrgprC11 expressing nerves, which despite comprising only 2–6% of sensory neurons, contribute to control of cholinergic bronchoconstriction (Han et al., 2018). In total, these studies reinforce the need for advanced experimental techniques that allow targeted, specific analysis of infrequent or rare nerve subtypes and their receptors.

To this end, several studies recently demonstrated the utility of optogenetics for testing effects of specific pulmonary nerve subtype activation. Optogenetics is a technique where the light-activated ion channel, channelrhodopsin, is expressed in specific neurons using cre-lox recombination, enabling activation of neuronal subtypes using pulsed light. This technique has been applied to test airway contractions induced by cholinergic airway neurons (Pincus et al., 2020), to differentiate vagal neurons involved in control of breathing (Chang et al., 2015; Nonomura et al., 2017), to show that light activate TRPV1-S1PR3 expressing neurons are involved in airway hyperresponsiveness after antigen challenge (Trankner et al., 2014), and to identify a rare subset of P2RY1-expressing laryngeal sensory nerves that coordinate upper airway responses to protect against aspiration (Prescott et al., 2020). Optogenetic techniques have potential to greatly advance our understanding of neuronal subtype function in vivo in future studies.

Until recently, studies of nerve morphology have been limited by conventional 2 dimensional histological assessments of tissue section that has led to an underappreciation of the rich neural supply lungs receive. Sensory nerves form complex, three-dimensional branching structures in airway epithelium that can span 100’s of histologic tissue sections yet comprising only a small percentage of the total airway surface area (West et al., 2015). Individual nerves frequently innervate multiple, spatially distinct receptive fields (Yu and Zhang, 2004). Moreover, nerve density is not uniform across the airways, but rather, is increased at airway branch points (i.e., carina, bifurcation of major bronchi) and in the posterior large airways (Scott et al., 2013). The sporadic nature of neuronal features, further accentuated by the non-uniform expression of neuropeptides and other proteins by nerves, make 2 dimensional tissue section analyses prone to large sampling error. To overcome these limitations, our group has recently used tissue optical clearing and confocal microscopy to perform detailed quantitative analyses of nerve structure and expression in whole mount airway samples (Figure 1; Scott et al., 2014). Indeed, our studies have demonstrated both an remarkable degree of structural complexity in airway epithelial nerves and identified a significant increase in nerve density in airway of patients with eosinophilic asthma (Drake et al., 2018b) as well as patients with idiopathic chronic cough (Shapiro et al., 2021).

Combining targeted functional assessments with high resolution 3D microscopy offers exciting new opportunities for studying the structure and function of specific nerve subtypes. Interactions between immune cells and airway nerves, as is seen in eosinophilic asthma, can also be quantified. Thus, these techniques may provide new mechanistic insights into the role of airway nerves in disease that can be translated into new therapeutic targets and may lead to improved disease phenotyping.

Conclusion

Airway sensory afferents have a central role in regulation of airway physiology and maintenance of lung health. Recent advancements in 3D confocal imaging, single cell PCR, and cre-lox techniques for testing specific nerve subtype activation have potential to provide new mechanistic insights into nerve function in health and disease. These studies may be harnessed to identify or refine disease phenotypes and to identify new therapeutic opportunities for patients. These advancements, coupled with the recent success of neuronally-targeted therapies such as P2X3 and NK1 receptor antagonists, suggest sensory nerves will have a prominent position in therapeutic development in the years ahead.

Author Contributions

MD wrote the manuscript. MC, AF, DJ, and GS provided critical input and revisions to the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

MD reports consulting fees for Astra Zeneca and GSK. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding

This work was supported by the NIH NHLBI: HL155623 (MD), AI152498 and HL144008 (DJ), and HL131525 (AF).

References

- Abdulqawi R., Dockry R., Holt K., Layton G., McCarthy B. G., Ford A. P., et al. (2015). P2X3 receptor antagonist (AF-219) in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet 385 1198–1205. 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61255-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aven L., Paez-Cortez J., Achey R., Krishnan R., Ram-Mohan S., Cruikshank W. W., et al. (2014). An NT4/TrkB-dependent increase in innervation links early-life allergen exposure to persistent airway hyperreactivity. FASEB J. 28 897–907. 10.1096/fj.13-238212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi M. G. (2002). Overview of the innervation of the lung. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2 211–215. 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00145-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi M. G., Birrell M. A., Khalid S., Wortley M. A., Dockry R., Coote J., et al. (2016). Neurophenotypes in Airway Diseases. Insights from Translational Cough Studies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 193 1364–1372. 10.1164/rccm.201508-1602oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi M. G., Birrell M. A., Wortley M. A., Maher S. A., Satia I., Badri H., et al. (2017). XEN-D0501, a Novel Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 1 Antagonist, Does Not Reduce Cough in Patients with Refractory Cough. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196 1255–1263. 10.1164/rccm.201704-0769oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvisi M. G., Smith J. A. (2017). ATP and cough reflex hypersensitivity: a confusion of goals? Eur. Respir. J. 50:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonini S., Lambiase A., Bonini S., Angelucci F., Magrini L., Manni L., et al. (1996). Circulating nerve growth factor levels are increased in humans with allergic diseases and asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 93 10955–10960. 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonvini S. J., Birrell M. A., Grace M. S., Maher S. A., Adcock J. J., Wortley M. A., et al. (2016). Transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily V, member 4 and airway sensory afferent activation: Role of adenosine triphosphate. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138 249–61e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boushey H. A., Holtzman M. J., Sheller J. R., Nadel J. A. (1980). Bronchial hyperreactivity. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 121 389–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse W. W. (2010). The relationship of airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation: Airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma: its measurement and clinical significance. Chest 138(2 Suppl.), 4S–10S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres A. I., Brackmann M., Elia M. D., Bessac B. F., del Camino D., D’Amours M., et al. (2009). A sensory neuronal ion channel essential for airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 106 9099–9104. 10.1073/pnas.0900591106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canning B. J. (2009). Central regulation of the cough reflex: therapeutic implications. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 22 75–81. 10.1016/j.pupt.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr M. J., Hunter D. D., Jacoby D. B., Undem B. J. (2002). Expression of tachykinins in nonnociceptive vagal afferent neurons during respiratory viral infection in guinea pigs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165 1071–1075. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.8.2108065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A. B., Gibson P. G., Ardill J., McGarvey L. P. (2007). Calcitonin gene-related peptide relates to cough sensitivity in children with chronic cough. Eur. Respir. J. 30 66–72. 10.1183/09031936.00150006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang R. B., Strochlic D. E., Williams E. K., Umans B. D., Liberles S. D. (2015). Vagal Sensory Neuron Subtypes that Differentially Control Breathing. Cell 161 622–633. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. L., Huang H. Y., Lee C. C., Chiang B. L. (2014). Small interfering RNA targeting nerve growth factor alleviates allergic airway hyperresponsiveness. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 3:e158. 10.1038/mtna.2014.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudry N. B., Fuller R. W., Pride N. B. (1989). Sensitivity of the human cough reflex: effect of inflammatory mediators prostaglandin E2, bradykinin, and histamine. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 140 137–141. 10.1164/ajrccm/140.1.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K. F., McGarvey L., Mazzone S. B. (2013). Chronic cough as a neuropathic disorder. Lancet Respir. Med. 1 414–422. 10.1016/s2213-2600(13)70043-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R., Monaghan K., About I., Griffin C. S., Sergeant G. P., El Karim I., et al. (2017). TRPA1 activation in a human sensory neuronal model: relevance to cough hypersensitivity? Eur. Respir. J. 50:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello R. W., Evans C. M., Yost B. L., Belmonte K. E., Gleich G. J., Jacoby D. B., et al. (1999). Antigen-induced hyperreactivity to histamine: role of the vagus nerves and eosinophils. Am. J. Physiol. 276(5 Pt 1), L709–L714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello R. W., Schofield B. H., Kephart G. M., Gleich G. J., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (1997). Localization of eosinophils to airway nerves and effect on neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor function. Am. J. Physiol. 273(1 Pt 1), L93–L103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh Q. T., Groneberg D. A., Peiser C., Springer J., Joachim R. A., Arck P. C., et al. (2004). Nerve growth factor-induced substance P in capsaicin-insensitive vagal neurons innervating the lower mouse airway. Clin. Exp. Allergy 34 1474–1479. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake M. G., Lebold K. M., Roth-Carter Q. R., Pincus A. B., Blum, Proskocil B. J., et al. (2018a). Eosinophil and airway nerve interactions in asthma. J. Leukoc. Biol. 104 61–67. 10.1002/jlb.3mr1117-426r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake M. G., Scott G. D., Blum, Lebold K. M., Nie Z., Lee J. J., et al. (2018b). Eosinophils increase airway sensory nerve density in mice and in human asthma. Sci. Transl. Med. 10:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunzendorfer S., Meierhofer C., Wiedermann C. J. (1998). Signaling in neuropeptide-induced migration of human eosinophils. J. Leukoc Biol. 64 828–834. 10.1002/jlb.64.6.828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy J. V., Wong H. H., Geppetti P., Reis J. M., Harris S. C., Maclean D. B., et al. (1995). Effect of an NK1 receptor antagonist (CP-99,994) on hypertonic saline-induced bronchoconstriction and cough in male asthmatic subjects. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 152 879–884. 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer A., McGregor G. P., Saria A., Philippin B., Kummer W. (1996). Induction of tachykinin gene and peptide expression in guinea pig nodose primary afferent neurons by allergic airway inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 98 2284–2291. 10.1172/jci119039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles H. E., Rowland T., Wright C., Morice A. (2017). Tussive challenge with ATP and AMP: does it reveal cough hypersensitivity? Eur. Respir. J. 49:2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer A. D., Costello R. W., Yost B. L., Lobb R. R., Tedder T. F., Steeber D. A., et al. (1997). Antibody to VLA-4, but not to L-selectin, protects neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pig airways. J. Clin. Invest. 99 2036–2044. 10.1172/jci119372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B. (1992). Function of pulmonary M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs is restored by heparin and poly-L-glutamate. J. Clin. Invest. 90 2292–2298. 10.1172/jci116116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer A. D., Stein L. H., Nie Z., Curtis D. E., Evans C. M., Hodgson S. T., et al. (2006). Neuronal eotaxin and the effects of CCR3 antagonist on airway hyperreactivity and M2 receptor dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 116 228–236. 10.1172/jci25423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard V., Naline E., Vilain P., Emonds-Alt X., Advenier C. (1995). Effect of the two tachykinin antagonists, SR 48968 and SR 140333, on cough induced by citric acid in the unanaesthetized guinea pig. Eur. Respir. J. 8 1110–1114. 10.1183/09031936.95.08071110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold W. M. (1973). Vagally-mediated reflex bronchoconstriction in allergic asthma. Chest 1973(Suppl 11S):63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Johnson D. A., Collins P. D., Rossi A. G., Jose P. J., Williams T. J. (1993). The chemokine, eotaxin, activates guinea-pig eosinophils in vitro and causes their accumulation into the lung in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 197 1167–1172. 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groneberg D. A., Niimi A., Dinh Q. T., Cosio B., Hew M., Fischer A., et al. (2004). Increased expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 in airway nerves of chronic cough. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 170 1276–1280. 10.1164/rccm.200402-174oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Lim M. E., Gleich G. J., Lee L. Y. (2009). Mechanisms of eosinophil major basic protein-induced hyperexcitability of vagal pulmonary chemosensitive neurons. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 296 L453–L461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Wiggers M. E., Gleich G. J., Lee L. Y. (2008). Sensitization of isolated rat vagal pulmonary sensory neurons by eosinophil-derived cationic proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 294 L544–L552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haland G., Carlsen K. C., Sandvik L., Devulapalli C. S., Munthe-Kaas M. C., Pettersen M., et al. (2006). Reduced lung function at birth and the risk of asthma at 10 years of age. N. Engl. J. Med. 355 1682–1689. 10.1056/nejmoa052885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L., Limjunyawong N., Ru F., Li Z., Hall O. J., Steele H., et al. (2018). Mrgprs on vagal sensory neurons contribute to bronchoconstriction and airway hyper-responsiveness. Nat. Neurosci. 21 324–328. 10.1038/s41593-018-0074-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle G. W., Graham R. M., Finkelstein J. B., Nguyen K. P., Gozal D., Friedman M. (1998). Hyperinnervation of the airways in transgenic mice overexpressing nerve growth factor. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 18 149–157. 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.2.2803m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle G. W., Mercer E. H., Palmiter R. D., Brinster R. L. (1993). Expression of NGF in sympathetic neurons leads to excessive axon outgrowth from ganglia but decreased terminal innervation within tissues. Neuron 10 1019–1034. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90051-r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. D., Myers A. C., Undem B. J. (2000). Nerve growth factor-induced phenotypic switch in guinea pig airway sensory neurons. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161 1985–1990. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9908051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. D., Wu Z., Dey R. D. (2010). Sensory neural responses to ozone exposure during early postnatal development in rat airways. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 43 750–757. 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0191oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idzko M., Hammad H., van Nimwegen M., Kool M., Willart M. A., Muskens F., et al. (2007). Extracellular ATP triggers and maintains asthmatic airway inflammation by activating dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 13 913–919. 10.1038/nm1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji R. R., Samad T. A., Jin S. X., Schmoll R., Woolf C. J. (2002). p38 MAPK activation by NGF in primary sensory neurons after inflammation increases TRPV1 levels and maintains heat hyperalgesia. Neuron 36 57–68. 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00908-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajekar R., Pieczarka E. M., Smiley-Jewell S. M., Schelegle E. S., Fanucchi M. V., Plopper C. G. (2007). Early postnatal exposure to allergen and ozone leads to hyperinnervation of the pulmonary epithelium. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 155 55–63. 10.1016/j.resp.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly Y. J., Brabin B. J., Milligan P., Heaf D. P., Reid J., Pearson M. G. (1995). Maternal asthma, premature birth, and the risk of respiratory morbidity in schoolchildren in Merseyside. Thorax 50 525–530. 10.1136/thx.50.5.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesler B. S., Mazzone S. B., Canning B. J. (2002). Nitric oxide-dependent modulation of smooth-muscle tone by airway parasympathetic nerves. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 165 481–488. 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.2004005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalid S., Murdoch R., Newlands A., Smart K., Kelsall A., Holt K., et al. (2014). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) antagonism in patients with refractory chronic cough: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134 56–62. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistemaker L. E. M., Prakash Y. S. (2019). Airway Innervation and Plasticity in Asthma. Physiology 34 283–298. 10.1152/physiol.00050.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer W., Fischer A., Kurkowski R., Heym C. (1992). The sensory and sympathetic innervation of guinea-pig lung and trachea as studied by retrograde neuronal tracing and double-labelling immunohistochemistry. Neuroscience 49 715–737. 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90239-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupari J., Haring M., Agirre E., Castelo-Branco G., Ernfors P. (2019). An Atlas of Vagal Sensory Neurons and Their Molecular Specialization. Cell Rep. 27 2508–2523.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalloo U. G., Fox A. J., Belvisi M. G., Chung K. F., Barnes P. J. (1995). Capsazepine inhibits cough induced by capsaicin and citric acid but not by hypertonic saline in guinea pigs. J. Appl. Physiol. 79 1082–1087. 10.1152/jappl.1995.79.4.1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen G. L., Colasurdo G. N. (1999). Neural control mechanisms within airways: disruption by respiratory syncytial virus. J. Pediatr. 135(2 Pt 2), 21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebold K. M., Drake M. G., Hales-Beck L. B., Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B. (2019). IL-5 Exposure in utero Increases Lung Nerve Density and Causes Airway Reactivity in Adult Offspring. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 62 493–502. 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0214oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu T. M., Myers A. C., Meeker S., Undem B. J. (2012). TRPV1 induction in airway vagal low-threshold mechanosensory neurons by allergen challenge and neurotrophic factors. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 302 L941–L948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lommatzsch M., Cicko S., Muller T., Lucattelli M., Bratke K., Stoll P., et al. (2010). Extracellular adenosine triphosphate and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 181 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludbrook V., Hanrott K., Marks-Konczalik J., Kreindler J., Bird N., Hewens D., et al. (2019). S27 A placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomised, crossover study to assess the efficacy, safety and tolerability of TRPV4 inhibitor GSK2798745 in participants with chronic cough. Thorax 74(Suppl. 2):A18. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B. (2005). An overview of the sensory receptors regulating cough. Cough 1:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzone S. B., Undem B. J. (2016). Vagal Afferent Innervation of the Airways in Health and Disease. Physiol. Rev. 96 975–1024. 10.1152/physrev.00039.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey L. P., Butler C. A., Stokesberry S., Polley L., McQuaid S., Abdullah H., et al. (2014). Increased expression of bronchial epithelial transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 channels in patients with severe asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern A. E., Mazzone S. B. (2014). Neural regulation of inflammation in the airways and lungs. Auton. Neurosci. 182 95–101. 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern A. E., Short K. R., Kywe Moe A. A., Mazzone S. B. (2018). Translational review: Neuroimmune mechanisms in cough and emerging therapeutic targets. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142 1392–1402. 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minette P. A., Barnes P. J. (1988). Prejunctional inhibitory muscarinic receptors on cholinergic nerves in human and guinea pig airways. J. Appl. Physiol. 64 2532–2537. 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.6.2532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. E., Campbell A. P., New N. E., Sadofsky L. R., Kastelik J. A., Mulrennan S. A., et al. (2005). Expression and characterization of the intracellular vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) in bronchi from patients with chronic cough. Exp. Lung Res. 31 295–306. 10.1080/01902140590918803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreaux B., Nemmar A., Vincke G., Halloy D., Beerens D., Advenier C., et al. (2000). Role of substance P and tachykinin receptor antagonists in citric acid-induced cough in pigs. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 408 305–312. 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00763-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice A. H., Fontana G. A., Belvisi M. G., Birring S. S., Chung K. F., Dicpinigaitis P. V., et al. (2007). ERS guidelines on the assessment of cough. Eur. Respir. J. 29 1256–1276. 10.1183/09031936.00101006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice A. H., Kitt M. M., Ford A. P., Tershakovec A. M., Wu W. C., Brindle K., et al. (2019). The effect of gefapixant, a P2X3 antagonist, on cough reflex sensitivity: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Eur. Respir. J. 54:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice A. H., Millqvist E., Bieksiene K., Birring S. S., Dicpinigaitis P., Domingo Ribas C., et al. (2020). ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur. Respir. J. 55:1. 10.1007/978-981-33-4029-9_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. C., Kajekar R., Undem B. J. (2002). Allergic inflammation-induced neuropeptide production in rapidly adapting afferent nerves in guinea pig airways. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 282 L775–L781. 10.1155/2017/2953930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa N., Sano H., Iwamoto I. (1995). Substance P induces the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on vascular endothelial cells and enhances neutrophil transendothelial migration. Peptides. 16 721–725. 10.1016/0196-9781(95)00037-k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2009). Etanercept prevents airway hyperresponsiveness by protecting neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in antigen-challenged guinea pigs. Br J Pharmacol. 156 201–210. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00045.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Nelson C. S., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2007). Expression and regulation of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on airway parasympathetic nerves. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 119 1415–1422. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Scott G. D., Weis P. D., Itakura A., Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B. (2011). Role of TNF-alpha in virus-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and neuronal M(2) muscarinic receptor dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol. 164 444–452. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01393.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieber K., Baumgarten C. R., Rathsack R., Furkert J., Oehme P., Kunkel G. (1992). Substance P and beta-endorphin-like immunoreactivity in lavage fluids of subjects with and without allergic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 90(4 Pt 1), 646–652. 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90138-r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura K., Woo S. H., Chang R. B., Gillich A., Qiu Z., Francisco A. G., et al. (2017). Piezo2 senses airway stretch and mediates lung inflation-induced apnoea. Nature 541 176–181. 10.1038/nature20793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell F., Springall D. R., Moradoghli-Haftvani A., Krausz T., Price D., Fuller R. W., et al. (1995). Abnormal intraepithelial airway nerves in persistent unexplained cough? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 152(6 Pt 1), 2068–2075. 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olgart Hoglund C., de Blay F., Oster J. P., Duvernelle C., Kassel O., Pauli G., et al. (2002). Nerve growth factor levels and localisation in human asthmatic bronchi. Eur. Respir. J. 20 1110–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka K., Niimi A., Matsumoto H., Ito I., Yamaguchi M., Matsuoka H., et al. (2011). Plasma substance P levels in patients with persistent cough. Respiration 82 431–438. 10.1159/000330419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaso E. M., Jaakkola M. S., Rantala A. K., Hugg T. T., Jaakkola J. J. (2014). Allergic diseases and asthma in the family predict the persistence and onset-age of asthma: a prospective cohort study. Respir. Res. 15:152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel K. R., Aven L., Shao F., Krishnamoorthy N., Duvall M. G., Levy B. D., et al. (2016). Mast cell-derived neurotrophin 4 mediates allergen-induced airway hyperinnervation in early life. Mucosal. Immunol. 9 1466–1476. 10.1038/mi.2016.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus A. B., Adhikary S., Lebold K. M., Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B. (2020). Optogenetic Control of Airway Cholinergic Neurons In Vivo. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 62 423–429. 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0378ma [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash Y. S., Martin R. J. (2014). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the airways. Pharmacol. Ther. 143 74–86. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott S. L., Umans B. D., Williams E. K., Brust R. D., Liberles S. D. (2020). An Airway Protection Program Revealed by Sweeping Genetic Control of Vagal Afferents. Cell 181 574–89e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti D., Saponaro G., Szallasi A. (2015). Transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) antagonists. Pharm. Pat. Anal. 4 75–94. 10.4155/ppa.14.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan K. L., Song I. S., Naik S. M., Letran E. L., Olerud J. E., Bunnett N. W., et al. (1999). VCAM-1 expression on human dermal microvascular endothelial cells is directly and specifically up-regulated by substance P. J. Immunol. 162 1656–1661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raap U., Deneka N., Bruder M., Kapp A., Wedi B. (2008a). Differential up-regulation of neurotrophin receptors and functional activity of neurotrophins on peripheral blood eosinophils of patients with allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis and nonatopic subjects. Clin. Exp. Allergy 38 1493–1498. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03035.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raap U., Fokkens W., Bruder M., Hoogsteden H., Kapp A., Braunstahl G. J. (2008b). Modulation of neurotrophin and neurotrophin receptor expression in nasal mucosa after nasal allergen provocation in allergic rhinitis. Allergy 63 468–475. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01626.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson J., Beland J. (1976). Nonadrenergic inhibitory nervous system in human airways. J. Appl. Physiol. 41(5 Pt. 1), 764–771. 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.5.764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawatzky D. A., Kingham P. J., Court E., Kumaravel B., Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B., et al. (2002). Eosinophil adhesion to cholinergic nerves via ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 and associated eosinophil degranulation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 282 L1279–L1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. D., Blum E. D., Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B. (2014). Tissue optical clearing, three-dimensional imaging, and computer morphometry in whole mouse lungs and human airways. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 51 43–55. 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0284oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott G. D., Fryer A. D., Jacoby D. B. (2013). Quantifying nerve architecture in murine and human airways using three-dimensional computational mapping. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 48 10–16. 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0290ma [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro C. O., Proskocil B. J., Oppegard L. J., Blum, Kappel N. L., Chang C. H., et al. (2021). Airway Sensory Nerve Density Is Increased in Chronic Cough. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 203 348–355. 10.1164/rccm.201912-2347oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard D., Epstein J., Holtzman M. J., Nadel J. A., Boushey H. A. (1982). Dose-dependent inhibition of cold air-induced bronchoconstriction by atropine. J. Appl. Physiol. Respir. Environ. Exerc. Physiol. 53 169–174. 10.1152/jappl.1982.53.1.169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsson B. G., Skoogh B. E., Ekstrom-Jodal B. (1972). Exercise-induced airways constriction. Thorax 27 169–180. 10.1136/thx.27.2.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaper S. D. (2017). Nerve growth factor: a neuroimmune crosstalk mediator for all seasons. Immunology 151 1–15. 10.1111/imm.12717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. H., Barker J. N., Morris R. W., MacDonald D. M., Lee T. H. (1993). Neuropeptides induce rapid expression of endothelial cell adhesion molecules and elicit granulocytic infiltration in human skin. J. Immunol. 151 3274–3282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J., Allman D., Badri H., Miller R., Morris J., Satia I., et al. (2020). The Neurokinin-1 Receptor Antagonist Orvepitant Is a Novel Antitussive Therapy for Chronic Refractory Cough: Results From a Phase 2 Pilot Study (VOLCANO-1). Chest 157 111–118. 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. A., Kitt M. M., Morice A. H., Birring S. S., McGarvey L. P., Sher M. R., et al. (2020). Gefapixant, a P2X3 receptor antagonist, for the treatment of refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, controlled, parallel-group, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 8 775–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trankner D., Hahne N., Sugino K., Hoon M. A., Zuker C. (2014). Population of sensory neurons essential for asthmatic hyperreactivity of inflamed airways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111 11515–11520. 10.1073/pnas.1411032111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. D., Birring S. S. (2019). Chronic cough: ATP, afferent pathways and hypersensitivity. Eur. Respir. J. 54:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbout N. G., Lorton J. K., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2007). Atropine pretreatment enhances airway hyperreactivity in antigen-challenged guinea pigs through an eosinophil-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 292 L1126–L1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhein K. C., Hazari M. S., Moulton B. C., Jacoby I. W., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2011). Three days after a single exposure to ozone, the mechanism of airway hyperreactivity is dependent on substance P and nerve growth factor. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 300 L176–L184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virchow J. C., Julius P., Lommatzsch M., Luttmann W., Renz H., Braun A. (1998). Neurotrophins are increased in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid after segmental allergen provocation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 158 2002–2005. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.6.9803023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. M., Jacoby D. B. (1999). Methacholine causes reflex bronchoconstriction. J. Appl. Physiol. 86 294–297. 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.1.294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Feng D., Yan H., Wang Z., Pei L. (2014). Comparative analysis of P2X1, P2X2, P2X3, and P2X4 receptor subunits in rat nodose ganglion neurons. PLoS One 9:e96699. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. K., Barnes P. J., Springall D. R., Abelli L., Tadjkarimi S., Yacoub M. H., et al. (1995). Distribution of human i-NANC bronchodilator and nitric oxide-immunoreactive nerves. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 13 175–184. 10.1165/ajrcmb.13.2.7542897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe N., Horie S., Michael G. J., Keir S., Spina D., Page C. P., et al. (2006). Immunohistochemical co-localization of transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV)1 and sensory neuropeptides in the guinea-pig respiratory system. Neuroscience 141 1533–1543. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Fajt M. L., Trudeau J. B., Voraphani N., Hu H., Zhou X., et al. (2015). Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Expression in Asthma. Association with Severity and Type 2 Inflammatory Processes. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 53 844–852. 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0015oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West P. W., Canning B. J., Merlo-Pich E., Woodcock A. A., Smith J. A. (2015). Morphologic Characterization of Nerves in Whole-Mount Airway Biopsies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 192 30–39. 10.1164/rccm.201412-2293oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicher S. A., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2017). Newly divided eosinophils limit ozone-induced airway hyperreactivity in nonsensitized guinea pigs. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 312 L969–L982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. X., Maize D. F., Jr., Satterfield B. E., Frazer D. G., Fedan J. S., Dey R. D. (2001). Role of intrinsic airway neurons in ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in ferret trachea. J. Appl. Physiol. 91 371–378. 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost B. L., Gleich G. J., Jacoby D. B., Fryer A. D. (2005). The changing role of eosinophils in long-term hyperreactivity following a single ozone exposure. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 289 L627–L635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Zhang J. (2004). A single pulmonary mechano-sensory unit possesses multiple encoders in rabbits. Neurosci. Lett. 362 171–175. 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.01.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaccone E. J., Lieu T., Muroi Y., Potenzieri C., Undem B. E., Gao P., et al. (2016). Parainfluenza 3-Induced Cough Hypersensitivity in the Guinea Pig Airways. PLoS One 11:e0155526. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Lin R. L., Wiggers M., Snow D. M., Lee L. Y. (2008a). Altered expression of TRPV1 and sensitivity to capsaicin in pulmonary myelinated afferents following chronic airway inflammation in the rat. J. Physiol. 586 5771–5786. 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.161042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang G., Lin R. L., Wiggers M. E., Lee L. Y. (2008b). Sensitizing effects of chronic exposure and acute inhalation of ovalbumin aerosol on pulmonary C fibers in rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 105 128–138. 10.1152/japplphysiol.01367.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Huang J., McNaughton P. A. (2005). NGF rapidly increases membrane expression of TRPV1 heat-gated ion channels. EMBO J. 24 4211–4223. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Oxford G. S. (2007). Phosphoinositide-3-kinase and mitogen activated protein kinase signaling pathways mediate acute NGF sensitization of TRPV1. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 34 689–700. 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]