Abstract

Objective

Partners of patients with RA often take on supportive roles given the debilitating nature of RA. Our objective was to explore the perspectives, attitudes and experiences of partners of female patients with RA regarding reproductive experiences and decision-making.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative study involving semi-structured interviews with partners of female patients with RA. We defined a partner as an individual within a romantic relationship. Constructivist grounded theory was applied to interview transcripts to identify and conceptualize themes.

Results

We interviewed 10 partners of female patients with RA (10 males; mean age, 35 [23–56] years), of whom 40% had at least one child with a female patient with RA and did not desire additional children. We identified four themes representing stages of reproductive decision-making: (1) developing an understanding of RA, (2) contemplating future family decision-making, (3) initiating reproductive decision-making with partner, and (4) reflecting on past reproductive experiences. Participants contemplated their attitudes and perspectives regarding pregnancy and used available information to support their partner’s medication decisions. When reflecting on their reproductive experiences, participants shared the impacts of past reproductive decisions on their romantic relationship and their mental health and wellbeing.

Conclusion

Our study highlights the need for comprehensive support for both female patients with RA and their partners at all stages of reproductive decision-making. Health-care providers can identify opportunities for intervention that involves female patients with RA and their partners to minimize stress and its negative impacts on the family.

Keywords: RA, partners, pregnancy, medication use, qualitative study

Key messages

Partners of female patients with RA supported their reproductive decision-making.

Participants underscored the impacts their reproductive experiences had on their romantic relationship and mental health.

Partners of female patients with RA require support from health-care professionals when making reproductive decisions.

Introduction

RA, a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease, disproportionately affects females [1] and often during their childbearing years [2]. Despite pregnancy historically being associated with disease remission [3, 4], recent evidence shows that ∼20% of patients with RA experience moderate to severe disease activity during pregnancy, and 40% encounter at least one post-partum flare [5, 6]. Female patients with RA face complex reproductive decisions related to fertility, timing of pregnancy and medication management. The daily impacts of RA, such as RA-related pain, functional limitations and disability, in addition to fear and anxiety related to perinatal medication use, further complicate reproductive decision-making [7]. However, recent evidence suggests that treatment of RA during pregnancy has improved considerably in the past decade, because a greater proportion of women are now able to reach low disease activity or remission by the third trimester with the use of medications such as TNF inhibitors [8]. Despite the advances in RA treatment, qualitative studies exploring pregnancy experiences of patients with inflammatory arthritis, including RA, have demonstrated additional barriers related to limited pregnancy planning support, information availability and care coordination among patients’ health-care teams [9].

Partners of female patients with RA play an important role in making reproductive decisions. A recent study by Rebic et al. [10] has highlighted the supportive role of partners of female patients with RA when making reproductive decisions. Recent research has discussed the need to understand the complex factors that influence a couple’s pregnancy decision-making as they set reproductive goals together [11]. Nonetheless, no research to date has explored the role of partners in reproductive decision-making with female partners with RA. In order to inform optimal care for both patients with RA and their partners, we aimed to explore the perspectives, attitudes and experiences of partners of female patients with RA when making reproductive decisions.

Methods

Design

We undertook semi-structured interviews, guided by a constructive grounded theory approach, to explore the reproductive decision-making perspectives and experiences of partners of female patients with RA. This approach aims to generate theory to explain social and human phenomena [12], for an in-depth understanding of the participant’s lived experiences. This study was approved by the University of Columbia Behavioral Research Ethics Board.

Recruitment

Our study is an extension of a current qualitative study exploring the reproductive and disease management decisions of female patients with RA (MOTHERS study) [10]. We used snowball sampling to recruit participants through female patients with RA who completed their participation in the MOTHERS study, were ≥18 years of age and able to communicate in English. For the purposes of our study, we defined a partner as an individual within a romantic/intimate relationship.

Data collection

We collected data through semi-structured video/telephone one-to-one interviews, which aimed to explore participant’s experiences, perspectives and attitudes related to making reproductive decisions alongside their partner with RA, in addition to accessing support and information related to RA and pregnancy. No changes were made to the interview guide during data collection. All interviews were conducted by the first author (R.G.), digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data collection and analysis were carried out simultaneously.

Analysis

Our coding procedure included the following three steps: initial coding, focused coding and theoretical coding. Coding using grounded theory allows for the establishment of a framework for analysis and the construction of theory for describing novel phenomena [11], a method that members of our team have used successfully to describe behaviours in rheumatology patients previously [13]. We used line-by-line coding to conceptualize initial codes. Next, we used focused coding to develop emerging categories and themes from significant and/or frequently identified codes. Lastly, we used theoretical coding to interpret relationships between constructed themes and categories [12]. Throughout the analysis, we applied constant comparative method and memo-writing to ensure the reliability of our results. Data analysis was conducted by the first author (R.G.). The findings and any discordance were discussed among the research team, and themes were refined to reach consensus when necessary. Data saturation was identified after eight participants were interviewed. Two additional participants were then interviewed to confirm saturation, indicated by a lack of new insights into the constructed themes and categories. Data analysis was preformed using NVivo 12 (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia).

Results

We interviewed 10 male participants with a mean participant age of 35 [23–56] years (see Table 1). Fifty per cent were married to their partner with RA, 40% had at least one child with their partner with RA, and 40% did not desire additional children. Disease characteristics of participants’ partners with RA are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), years | 35 (23–56) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 10 (100) |

| Canadian province of residence, n (%) | |

| British Columbia | 4 (40) |

| Ontario | 3 (30) |

| Other (i.e. Alberta, New Brunswick or Nova Scotia) | 3 (30) |

| Geographical residence, n (%) | |

| Rurala | 1 (10) |

| Urbanb | 9 (90) |

| Ancestry, n (%) | |

| White | 6 (60) |

| Asian | 2 (20) |

| Hispanic | 1 (10) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (10) |

| Highest level of education attained, n (%) | |

| Post-secondary (university, college, technical school, etc.) | 9 (90) |

| Secondary or high school | 1 (10) |

| Current employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed full time (≥40 h/week) | 8 (80) |

| Self-employed | 2 (20) |

| Household income, n (%) | |

| Lowc | 1 (10) |

| Moderated | 2 (20) |

| Highe | 7 (70) |

| Current members of household, median (interquartile range) | 4 (2–4) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 5 (50) |

| Common-law or co-habiting | 2 (20) |

| Single, never married | 2 (20) |

| Separated | 1 (10) |

| Duration of current intimate partner relationship, n (%), years | |

| ≥10 | 5 (50) |

| 5–10 | 0 0 |

| ≤5 | 5 (50) |

| Plans to have future children, n (%) | 6 (60) |

| Future reproductive options considered, n (%)f | |

| Childbearing | 5 (83) |

| Adoption | 2 (33) |

| Other (i.e. surrogacy or assisted fertilization) | 1 (17) |

| Previously had children with current partner, n (%) | 4 (40) |

| Number of children with current partner, median (range) | 2 (1–2) |

Fewer than 400 people/km2. bMore than 400 people/km2. cA total annual household income of ≤50% of the area median income. dA total annual household income of >50% and <80% of the area median income. eA total annual household income of ≥80% of the area median income. fCumulative percentage can be >100, because multiple categories can be relevant to each participant.

Table 2.

Partners’ disease characteristics

| Characteristic | Statistic |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range), years | 32 (21–42) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 10 (100) |

| Years diagnosed with RA, median (interquartile range) | 7 (4–17) |

| Parity, n (%) | |

| Multiparous | 5 (50) |

| Nulliparous | 5 (50) |

| Current medications taken for RA, n (%)a,b | |

| Conventional synthetic DMARDs | |

| Antimalarials (i.e. HCQ, chloroquine) | 8 (80) |

| MTX | 9 (90) |

| SSZ | 5 (50) |

| LEF | 2 (20) |

| Biologic and targeted synthetic DMARDs | |

| Anti-TNF agents | 7 (70) |

| Others (e.g. abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab, tofacitinib) | 4 (40) |

| Used medication for RA during pregnancy, n (%) | 3 (60) |

Cumulative percentage can be >100, because multiple categories can be relevant to each participant. bMedications taken for RA by female patients at the time of their demographics survey.

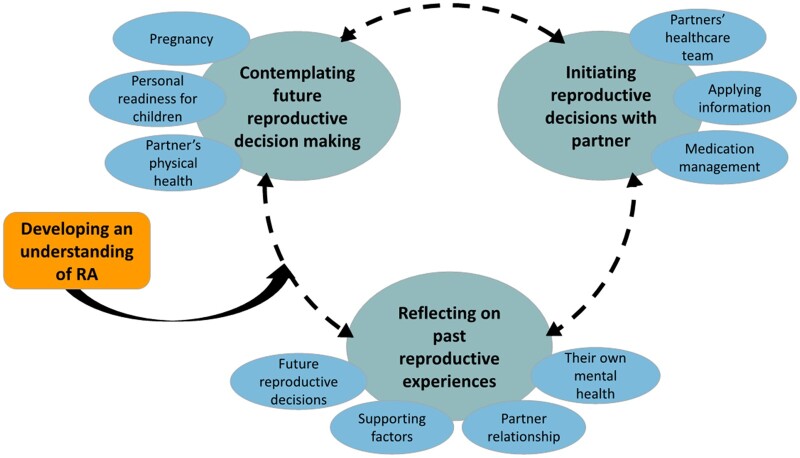

We identified four dynamic stages of reproductive decision-making experienced by partners of female patients with RA: (1) developing an understanding of RA, (2) contemplating future family decision-making, (3) initiating reproductive decision-making with partner, and (4) reflecting on past reproductive experiences. Representative quotations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Illustrative quotes for stages of reproductive decision-making experienced by partners of women with RA

| Category | Representative quotations |

|---|---|

| Stage 1: developing an understanding of RA | |

| “I don’t feel like I am worried about it, then I haven't really thought of those things, because it's the kind of thing that it's tough to imagine, the sort of things that may come up until it comes up.” (Participant 1, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) | |

| “My knowledge of it pre [partner with RA] was, was almost to the point that I thought arthritis was what old people get; I was one of those people.” (Participant 2, does not have children, intends to have children in the future) | |

| Stage 2: contemplating future reproductive decisions | |

| Impacts on child development | “From my understanding, I could be 100% wrong, but I mean what could we pass, what could be passed on to children as well?” (Participant 5, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) |

| “We thought that just having family as well close by that could help, you know, with the baby, and knowing that it would be harder for [name] to do certain tasks as well, I think that was a big part of our discussions.” (Participant 7, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Impacts on partner’s physical health | “I think that is sort of the worry, because I saw what the first flare-up was like and how tough that was, so to be able to see her go through something that like but trying to, you know, enjoy, enjoy what kind of cultivating a life is supposed to be.” (Participant 9, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) |

| “So, I was trying to understand what is the likelihood of, like, the negatives that are involved, so what's the likelihood of, of her flaring up, what, from a statistical basis, how many people went through, you know, symptomatic issues during pregnancy which didn’t.” (Participant 2, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) | |

| Gathering information about RA and pregnancy | “The first source would be her [partner], her rheumatologist or one of the specialists. And then I would go take a look at WebMD and a bunch of other websites to see and just see what other people's opinions are and, and forums.” (Participant 8, has children with current partner, finished growing family) |

| “I know there's a lot out there but it's, I guess, finding it is, it's a bit tough. And yeah, because it's not a very, very, very common disease … what are the risks and what are the chances of bad things happening and stuff like that.” (Participant 6, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Personal readiness for children | “Our relationship in itself is complicated without the factor of rheumatoid arthritis, ‘cause we are in a long-distance relationship, so I’m based in Australia, she's Canadian.” (Participant 2, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) |

| “So the same thing we’re going through now, where maybe not being able to father again, and I’m now ‘as much a man as I used to be’. I guess as you get into your 50s you feel like, ‘Okay, is this midlife? Am I just wanting to have a child because I want to prove I’m still man?’ That was my concern, like, ‘Why am I really getting involved in this?’.” (Participant 3, has children from previous relationship, intends to have children in the future) | |

| Stage 3: initiating reproductive decisions with partner | |

| Applying information about pregnancy and RA | “When you start reading all the experiences online, then your expectation or anticipation is guided by what you’re reading and you’re expecting, you know? That’s the problem with self-learning and especially when you’re doing the population. There’s a distribution. Which side are you on of the curve?” (Participant 3, has children from previous relationship, intends to have children in the future) |

| “It definitely gives you more information, but I guess it doesn't make it extremely easy to make the decision. It's more of a what risks are you comfortable making sort of thing.” (Participant 6, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Interacting with partner’s health-care team | “So, I know she had her previous immunologist, she did not have a good relationship with him, and it seemed that the doctor seemed to push her regimen for medications that she believed everyone should be taking. So, methotrexate.” (Participant 3, has children from previous relationship, intends to have children in the future) |

| “They coulda looked it up and they coulda seen the safety, they didn't have to take you off all the drugs, and if they called us, they coulda told us you didn't have to suffer all that pain. As a result of that, her fingers are now permanently like, like this, a lot of ‘em, they’re like twisted and you know? So that made me a little upset because it was mishandled.” (Participant 8, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Supporting partner’s RA medication management decisions | “[Partner with RA] was going through some bad flare-ups and so we were trying to kind of make the right decisions and obviously mostly with [the rheumatologist] trying to figure out how her medication management would affect kind of family planning.” (Participant 7, has children with current partner, finished growing family) |

| “I would say but definitely we had worries about, about that medication plus pregnancy, so I think we decided to play it safe, and I think she stopped the medication. I mean she stopped everything but at that point.” (Participant 10, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Stage 4: reflecting on past reproductive experiences | |

| Making future reproductive decisions | “After [partner with RA] went through that experience that we essentially kind of decided that we would likely not go through that again, that it would be too hard for [partner with RA] to get back to a state where she felt good enough again to do day-to-day and then only just to say okay, well now you have to get off medication for 6 months before we can even try to have another baby.” (Participant 7, has children with current partner, finished growing family) |

| “We did want to have two kids, and I think her RA was not at a point where the pain would, you know, prevent us from having another kid.” (Participant 10, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Factors that supported their past reproductive experiences | “We've found, like, the information that we needed out of them and again through, I think having again that professional that can bridge that gap is really important as well, like, so … [the rheumatologist has] been able to really kind of synthesize and put it all together for us.” (Partner 7, has children with current partner, finished growing family) |

| “I think we've always been on the same page to be honest, it's ‘cause we’ve been, yeah, just throughout the years it's been, like I said, it's been a lot, like a lot of little conversations throughout the years and that's helped.” (Partner 4, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) | |

| Impacts on their individual mental health | “There were definitely times that it's, you know, when you really, really think about it, it, it is emotionally draining and does affect you mentally because, you know, naturally, we always focus on the negatives.” (Participant 2, no previous children, intends to have children in the future) |

| “Absolutely, it has. I'm not as stable as I used to be. I lose control every now and then.” (Participant 8, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

| Impacts on their intimate partner relationship | “I think the fact that we can talk about these things makes anything else not taboo, in a sense. If we can talk about conceiving and all of the options, I think it does allow us to open up about other things.” (Participant 3, has children from previous relationship, intends to have children in the future) |

| “I can’t have you be at home and then you’re cursing me the rest of your life saying that I took away the one thing that you like doing because I wanted to have kids. Right? So that’s the thing, so that’s why it was a tough pill to swallow, but we both did.” (Participant 8, has children with current partner, finished growing family) | |

Stage 1: developing an understanding of RA

Before meeting their current partner, many participants expressed a lack of awareness regarding RA, particularly the challenges and limitations it might pose on their partner’s daily life. As one participant stated, ‘I was ignorant of how RA would affect individuals’ (Participant 3). Predominantly, participants received education surrounding the burden of RA spanning pain and functional limitations from their partner, which allowed participants to gain an understanding of the impacts of RA on various aspects of their partner’s life. Additionally, many participants had been informed that pregnancy might require extensive planning owing to RA disease and medication management by their partner during the early stages of their romantic relationship. At this stage, participants did not consider the implications that RA and pregnancy might impose on both their partner and themselves, because participants felt that barriers related to pregnancy and RA would be addressed better once the couple was ready to have children. For example, one participant stated, ‘It’s tough to imagine the sort of things that may come up until it comes up’ (Participant 1).

Stage 2: contemplating future reproductive decisions

Once participants began to consider the prospect of having children with their partner, they described contemplating the implications of RA and pregnancy for both their partner and themselves. To support this process, participants might also gather information regarding RA and pregnancy.

Initially, participants considered how RA and pregnancy might impact their partner’s physical health. For example, one participant expressed concern for the potential that their partner becomes physically ‘disabled’ (Participant 6) secondary to DMARD discontinuation for pregnancy purposes. Many attributed their concerns to uncertainty regarding disease severity during pregnancy, fluctuation of RA symptoms perinatally, and the probability of achieving disease remission during pregnancy. Relatedly, participants questioned the discontinuation of DMARDs before pregnancy, because they worried that this might lead to their partner experiencing perinatal RA flares. As an alternative to pregnancy, three participants considered adoption, because they believed adoption would allow their partner to forego physical challenges secondary to pregnancy and/or medication discontinuation.

Next, participants considered the implications of RA on a pregnancy. A primary concern was the risk of birth defects secondary to use of DMARDs during pregnancy. Participants expressed discomfort with the use of biologics owing to the lack of consensus regarding effects on fetal development. One participant stated, ‘The biologics is still fairly new, and we don’t know what the long-term effects are’ (Participant 4). Of the four participants who previously had children with their partner with RA, two supported their partner’s use of perinatal DMARDs, because they perceived RA disease activity to be unmanageable without the use of DMARDs. Other participants were concerned that RA might be hereditary, and some considered the impacts of their partner’s RA on a child’s upbringing. Consequently, participants worried about their capability to care for both their child and their partner, particularly during periods of RA flares. As a result, many couples sought support from their extended family and considered moving closer to their own parents to ensure access to childcare support.

Finally, participants considered their personal readiness for children and expressed concerns related to financial security, career trajectory and pre-existing health conditions when considering future reproductive decisions. Ensuring financial security before having their first child was a priority for many participants. Some considered their current career and whether they would have the flexibility at work to provide care and support to both their partner and their child. For example, one participant stated, ‘Freedom to not be kinda like locked into a set schedule or again like that I have to decide oh … she [partner] can't really move today … but I have to go to work’ (Participant 9). One participant, who had a pre-existing health condition, expressed needing to take into account his own health in addition to that of his partner when considering their future reproductive decisions.

At this stage, participants might also gather information to aid their future reproductive decision-making. Most participants relied on their partner to share and discuss information and resources with them. Participants acted as a ‘sounding board’ (Participant 6) for their partner, through consoling their concerns and providing support as they sorted through new information. At times, participants turned to online resources to search for research articles regarding specific questions, such as the frequency of RA flares during pregnancy and the effects of perinatal medication use on fetal development. Some participants expressed a desire to consult their partner’s rheumatologist once their partner became pregnant, because they foresaw having additional questions and did not want to receive ‘third party’ (Participant 5) information through their partner.

Stage 3: initiating reproductive decisions with partner

Once participants initiated reproductive decision-making, they described their experiences supporting their partner’s medication decisions, applying available information regarding pregnancy and RA and interacting with their partner’s health-care team.

Participants described supporting their partner’s medication decisions, as their partner navigated decisions related to perinatal medication use. Couples engaged in conversations related to their reproductive options, and participants contributed their opinions and concerns regarding perinatal medication use, such as RA symptom management and the risk of fetal side effects. If couples anticipated RA symptoms to be well managed without DMARDs or were hopeful for disease remission while pregnant, participants supported their partner’s decision to discontinue DMARDs, because they opted to ‘play it safe’ (Participant 10) rather than risk fetal harms secondary to medication use. Conversely, if couples anticipated RA activity while pregnant, participants supported use of perinatal DMARDs. Many participants worried that perinatal discontinuation of medication might cause their partner to experience RA flares and/or functional limitations, which might subsequently impact their partner’s ability to perform self-care and parenting activities independently.

Next, participants shared their struggles with applying information regarding pregnancy and RA to their own reproductive decisions with their partner. Couples made decisions concerning medication based on the rheumatologist’s guidance and their own assessment of the perceived risk to both mother and fetus as a result of medication continuation/discontinuation. However, many participants desired a definitive answer for whether their partner should continue or discontinue perinatal use of DMARDs and expressed that their final decision was based on a ‘guess’ (Participant 4). Participants found ‘research articles’ (Participant 9) to be inconclusive and believed that topics such as impacts of medication use during pregnancy require further research. Although some participants indicated that information gathered from other people’s experiences provided reassurance, they also struggled to use this information because they were uncertain how it might apply to their own situation. For example, one participant stated, ‘It's not for a lack of information; it's really just trying to find the most relevant one … the situations that you're trying to address’ (Participant 7).

Participants also described their experience of interacting with their partner’s health-care team, which might include a rheumatologist, an obstetrician and a family doctor. Although several participants expressed gratitude for the support provided by their health-care team, some expressed concern regarding their partner’s unmet care needs. Two of the 10 participants desired greater support from their rheumatologist when trying to conceive; for example, one participant stated, ‘We were told by doctors that you're never gonna have kids’ (Participant 8), reporting feelings of frustration as they felt that their female partner’s ability to conceive was not prioritized by their rheumatologist. Additionally, participants were often frustrated by the lack of communication between their partner’s many health-care providers, which they believed caused a ‘lag in care’ (Participant 3). Three participants also described feeling ‘disappointed’ (Participant 8) by the care their partner received from non-rheumatologist providers. Notably, two participants described instances of abrupt discontinuation of medication by non-rheumatologist providers during pregnancy. Consequently, in most cases, once a rheumatologist was consulted the medications discontinued by a non-rheumatologist were later found to be compatible with pregnancy. In cases of wrongful discontinuation of medication, participants believed their partner was caused unnecessary harm.

Stage 4: reflecting on past reproductive experiences

While supporting their partner’s reproductive journey, participants reflected on their past reproductive experiences. Specifically, they described supporting factors and how their past experiences impacted their future decision-making, their relationship with their romantic partner and their own mental health.

When engaging in reproductive decision-making with their partner, participants identified supporting factors such as a proactive rheumatologist, access to diverse sources of information, insight gained from their partner’s previous pregnancy experience(s), and honest communication with their partner. Many participants emphasized the importance of an attentive rheumatologist, who maintains focus on their partner’s quality of life and is able to synthesize medical information in a patient-friendly manner. Additionally, access to multiple sources of information, such as the opinion of a secondary care provider, research articles and the lived experience of other female patients with RA, provided participants with reassurance that they had assessed all available literature before making a decision. For example, one participant stated, ‘Once we have all the information and we can judge for ourself’ (Participant 10). Lastly, all participants highlighted the importance of honest communication with their partner. Many described how open discussions regarding their perspectives and expectations allowed couples to remain ‘on the same page’ (Participant 4), which relieved anxiety related to reproductive decision-making.

Often, participant’s perspectives were shaped by their past reproductive experiences. Participants who witnessed their partner undergo a painful previous pregnancy secondary to perinatal RA flares decided to have fewer children than desired initially. For many participants, the relationship between their partner’s RA medication management and pregnancy became evident after a reproductive experience was shared with their partner. They described learning about the complicated process of adjusting RA medication before pregnancy and the need for RA management and their reproductive decisions to ‘intersect’ (Participant 7). However, one participant shared that his partner’s disease activity before and during pregnancy remained stable. As a result, his partner did not require DMARDs perinatally, and the couple’s reproductive decisions were not influenced by RA.

Some participants shared the impact that reproductive decision-making had on their relationship with the romantic partner. A majority of participants expressed feeling closer to their partner after starting a family together, as they embarked on an ‘intimate’ (Participant 3) journey. However, other participants feared that this process might cause a strain on their romantic relationship. One participant was concerned he might experience feelings of frustration owing to the physical limitations his partner might face once she changes her DMARDs for pregnancy purposes. Another participant feared that his desire for children might cause his partner to develop feelings of resentment towards him and that she might blame him for any functional limitations experienced after pregnancy.

Finally, many participants acknowledged the impact that supporting their partner’s reproductive decisions had on their own mental health and wellbeing. Participants expressed feelings of constant worry for their partner’s physical health and wellbeing, as one participant shared, ‘It takes up extra real-estate in my mind’ (Participant 9). Others shared how they struggled initially to accept that they might not have additional children with their partner. Although the decision not to have additional children was made in agreement between participants and their partners, because they did not want to risk negative impacts of pregnancy on their partner’s health, participants still required time to process this decision, as one participant stated, ‘It was a tough pill to swallow’ (Participant 8). However, despite the added labour of caring for their partner, all participants expressed gratitude for their romantic relationship, their children, and the ability to explore alternative childrearing options with their partner.

Relationship between the themes

Partners of female patients with RA may encounter four dynamic stages of reproductive decision-making, as represented in Fig. 1. Near the beginning of the relationship with their romantic partner, participants developed an understanding of the limitations and challenges that RA might pose on their partner’s daily life (stage 1). As couples began to consider the prospect of having children, participants contemplated the implications of pregnancy and RA (stage 2) on their partner and themselves. Subsequently, they initiated reproductive decision-making with their partner (stage 3). At various points throughout the reproductive decision-making process, participants reflected on their past reproductive experiences (stage 4). The process of reproductive decision-making is dynamic, and participants can move back and forth between stages as they contemplate various aspects of decision-making, initiate decisions and reflect on their past reproductive experiences.

Fig. 1.

Complex stages of reproductive decision-making encountered by partners of female patients with RA

Discussion

In this constructivist grounded theory study, we used semi-structured interviews to understand the experiences of partners of female patients with RA while making reproductive decisions. Our analysis led to the development of a conceptual framework represented by four stages of reproductive decision-making: (a) developing an understanding of RA, (b) contemplating future reproductive decisions, (c) initiating reproductive decisions with a partner, and (d) reflecting on past reproductive experiences. Participants contemplated factors related to pregnancy and RA and attempted to use available information to support their partner’s medication taking. When reflecting on past reproductive experiences, participants shared the impacts of reproductive decision-making on their romantic relationship and mental health and wellbeing.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that has explored the role of partners of female patients with RA in making reproductive decisions, in addition to their perspectives, attitudes and experiences of supporting their partner’s reproductive journey. Prior qualitative research has focused on the partner’s perceptions of their spouse’s pain, fatigue and limitations related to RA [11], the impact of caregiving for a partner with RA [9], and unmet support needs among partners of patients with RA [13]. Additionally, previous work by Mann et al. [14] has highlighted the presence of heterogeneity related a couple’s approach to RA management. Although some couples chose to engage in shared decision-making related to RA management, others decided that the individual with RA would lead disease management decisions [14]. However, some couples experienced conflicts when the partner without RA felt that they were unable to provide input to their partner’s RA management [14]. Our study also contributes to the literature by addressing how couples approach RA management in the context of making reproductive decisions.

Our results suggest a need for comprehensive supports for both female patients with RA and their partners as they make reproductive decisions. Health-care providers, including rheumatologists, can play an important role in supporting female patients with RA and their partners by engaging in shared decision-making and dissemination of available information. For example, health-care professionals can provide partners of female patients with RA information and resources regarding medication use during pregnancy, in addition to facilitating discussions regarding the current evidence surrounding RA and pregnancy to aid the couple’s abilities to make informed decisions. Moreover, developing community groups for partners of patients with RA might help to support their wellbeing and information needs, such as extended learning sessions for partners to provide further education regarding RA and its management.

The strengths and limitations of our study also warrant discussion. Our collaboration with rheumatologists and patient research partners informed the design, procedures and interpretation of research findings. Recruitment of study participants through their partners, who were themselves participants in the MOTHERS study [12], facilitated linkage to female partner’s RA disease characteristics. However, given our interest in the partner’s perspective, we did not collect specific information on the female partner’s pregnancy, such as the time since pregnancy, medication use during pregnancy and fertility status. We conducted telephone and video interviews, which allowed us to capture perspectives from geographically diverse locations, although this also limited recruitment to individuals with access to those technologies. Although we aimed to recruit individuals from diverse backgrounds, all participants identified as male and a majority were highly educated. Our intention, however, was not to represent all partners of patients with RA, but to use a sampling strategy that allowed for in-depth exploration of partners of female patients with RA who participated in the MOTHERS study. Nonetheless, there is need for future research that considers perspectives from diverse health literacy, gender and sexual identities.

Altogether, this study provides insight into the perspectives of partners of female patients with RA and has led to the development of a conceptual framework on the partner’s role in reproductive decision-making. Given the supportive role of partners of female patients with RA when making reproductive decisions, health-care providers and arthritis organizations need to include partners in their scope of care and service delivery in order to support both patients with RA and their partners throughout the process of reproductive decision-making.

Acknowledgements

This work was presented previously at the 2020 American College of Rheumatology Convergence conference and the abstract published in Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(suppl 10). Dr De Vera holds a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair and is a recipient of a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Nevena Rebić is a receipt of a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Drug Safety and Effectiveness Cross-Disciplinary Training (DSECT) program award.

Funding: This study was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Initiative for Outcomes in Rheumatology Care.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data used in this article cannot be shared publicly due to institutional ethics restrictions intending to protect the privacy of research participants.

References

- 1.Whitacre CC, Reingold SC, O'Looney PA.. A gender gap in autoimmunity. Science 1999;283:1277–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badley EM, Kasman NM.. The impact of arthritis on Canadian women. BMC Womens Health 2004;4(Suppl 1):S18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marder W, Littlejohn EA, Somers EC.. Pregnancy and autoimmune connective tissue diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2016;30:63–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerosa M, Schioppo T, Meroni PL.. Challenges and treatment options for rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016;17:1539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Man YA, Dolhain RJ, van de Geijn FE, Willemsen SP, Hazes JM.. Disease activity of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: results from a nationwide prospective study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause ML, Makol A.. Management of rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy: challenges and solutions. Open Access Rheumatol 2016;8:23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Backman CL, Smith LDF, Smith S, Montie PL, Suto M.. Experiences of mothers living with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:381–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebić N, Garg R, Ellis U. et al. “Walking into the unknown…” key challenges of family planning and pregnancy in inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobi CE, van den Berg B, Boshuizen HC. et al. Dimension-specific burden of caregiving among partners of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology 2003;42:1226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebic N, Garg R, Munro S. et al. Making decisions about medication use, pregnancy, and having children among women with rheumatoid arthritis: a constructivist grounded theory study [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 2020;7(Suppl 10). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehman AJ, Pratt DD, DeLongis A. et al. Do spouses know how much fatigue, pain, and physical limitation their partners with rheumatoid arthritis experience? Implications for social support. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charmaz K.Constructing grounded theory, 2nd edn.London; Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matheson L, Harcourt D, Hewlett S.. ‘Your whole life, your whole world, it changes’: partners' experiences of living with rheumatoid arthritis. Musculoskeletal Care 2010;8:46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann C, Dieppe P.. Different patterns of illness-related interaction in couples coping with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:279–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this article cannot be shared publicly due to institutional ethics restrictions intending to protect the privacy of research participants.