Abstract

Objective

The association between enterovirus infection and type 1 diabetes (T1D) is controversial, and this meta-analysis aimed to explore the correlation.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database were searched from inception to April 2020. Studies were included if they could provide sufficient information to calculate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. All analyses were performed using STATA 15.1.

Results

Thirty-eight studies, encompassing 5921 subjects (2841 T1D patients and 3080 controls), were included. The pooled analysis showed that enterovirus infection was associated with T1D (P < 0.001). Enterovirus infection was correlated with T1D in the European (P < 0.001), African (P = 0.002), Asian (P = 0.001), Australian (P = 0.011), and Latin American (P = 0.002) populations, but no conclusion could be reached for North America. The association between enterovirus infection and T1D was detected in blood and tissue samples (both P < 0.001); no association was found in stool samples.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that enterovirus infection is associated with T1D.

Keywords: enterovirus infection, type 1 diabetes, case-control studies, odds ratio, meta-analysis

Introduction

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is a multifactorial disease resulting from the autoimmune destruction or dysfunction of pancreatic β cells (1). T1D has become a global burden, and at least 13 million individuals suffer from the disease worldwide (2, 3). Exogenous insulin injection cannot produce an optimal control of glucose homeostasis, leading to microvascular complications in the heart, brain, eye, kidney, and peripheral nervous system (4).

Although several environmental factors have been reported to be associated with T1D, enterovirus infection is under intensive focus (4–6). It is a ubiquitous, small, non-enveloped positive-strand RNA virus. Enterovirus genus belongs to the Picornaviridae family and consists of 15 species, seven of which contain human pathogens. These human infecting enteroviruses are classified into four species (Enterovirus A-D and Rhinovirus A-C) and contain more than 250 serologically distinct viruses. Enterovirus A-D consists of over 100 different types, including polioviruses, coxsackievirus types A and B (CVA and CVB), numbered enteroviruses, and echoviruses (7, 8). Enteroviruses potentially interact with several receptors (9), among which the coxsackie and adenovirus receptor (CAR) is the most studied with respect to T1D. Enteroviruses can infect pancreatic β cells in pancreatic islets via the CAR, which is expressed on β and α cells, and the viruses replicate in both these cell types (10, 11). Both acute and persistent enterovirus infections have been shown to affect the functions of the host cell, inducing β cell death, decreasing insulin mRNA expression and insulin secretion, and disrupting the Golgi apparatus (11–16).

A meta-analysis identified the correlation between enterovirus infection and T1D in 2011 (17). Although several original studies have been reported from 2012 to 2020 (10, 18–34), no updated meta-analysis has been performed to explore and refine the correlation. The conclusions of the original studies are conflicting, and thus, a meta-analysis including the latest studies is still needed to evaluate the association between enterovirus infection and T1D.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Database were searched for relevant studies. We used the following terms for searching: “enterovirus” AND (“type 1 diabetes” OR “type 1 diabetic patients” OR “type 1 diabetes mellitus” OR “insulin-dependent diabetes” OR “insulin-dependent diabetic patients” OR “T1D” OR “T1DM”). The searches were restricted to English-language articles published up to April 2020. We also reviewed the references of included articles to identify any potential additional study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) study design: case-control; (2) outcomes: investigated the association between enterovirus infection and T1D and reported the number of subjects with and without enterovirus infection for each group; (3) subjects: patients with insulin-dependent diabetes (i.e., T1D); and (4) controls: non-diabetic individuals. When there were multiple publications from the same study population, only the publication with the largest sample size was included. Studies were excluded if they were (1) reviews, letters, or case reports, (2) cell or animal studies, or (3) duplicate publications from the same population.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted independently by two authors. Disagreements were resolved by a third author. The following information was extracted: first author, publication year, country, mean age, the gender ratio of the cases, number of patients in the case and control group, number of enterovirus infections in each group, detection method, sample source, and enterovirus type. We also contacted the corresponding author to obtain details of the missing relevant data.

Quality Assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale (NOS) (35), a 9-star system, was used for quality assessment. Two authors assessed the studies independently. Any differences were resolved by consulting a third author. The assessment scale included the selection method of the exposed group (with enterovirus infection) and the non-exposed group (without enterovirus infection), the matching of the two groups, and the outcome assessment. A study awarded more than 5 stars was considered a high-quality study.

Statistical Analysis

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to estimate the strength of the association between enterovirus infection and T1D. The fixed-effect model was used for non-heterogeneous data, and the random effect model was used for heterogeneous data. The Q and I 2 statistics were used to test for heterogeneity. If statistically significant heterogeneity was present (Q statistic P < 0.05 or I 2 ≥ 50%), the random-effect model was applied; otherwise, the fixed-effect model was used (36). In order to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analyses by continents (Asia, Europe, North America, or Africa), detection methods (PCR, ELISA, or immunostaining), sample sources (blood, tissue, or stool), and study quality (NOS score ≥ 6 or < 6). The sensitivity analysis was conducted by the sequential removal of each study. Begg’s correlation and Egger’s regression were used to assess the potential publication bias (37, 38). All analyses were conducted using STATA 15.1 (Stata, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis

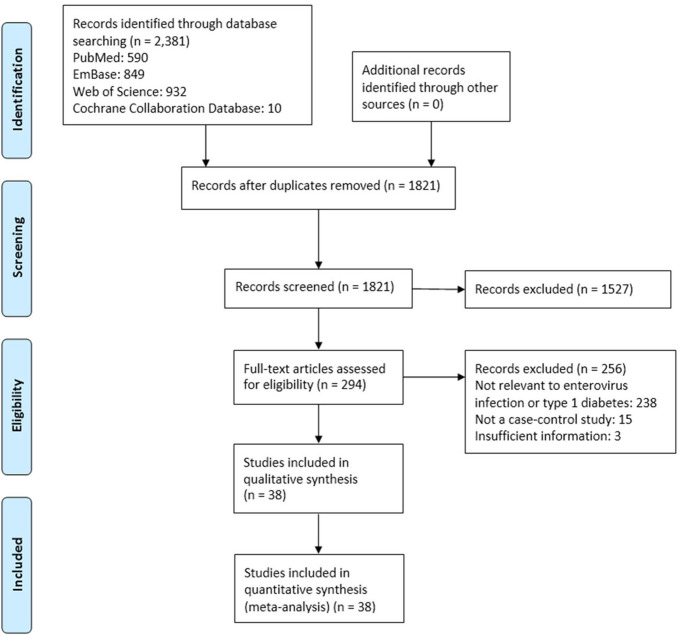

The study process is shown in Figure 1. Among 1501 potentially relevant studies, 38 met the inclusion criteria (10, 18–34, 39–58). The dataset included 5921 subjects (2841 T1D patients and 2841 controls). The included studies were published from 1990 to 2019, with sample sizes ranging from 7 to 766. Of these studies, 25 were from Europe, four from Africa, two from Asia, two from Australia, one from North America, and one from Latin America. Most studies were in Caucasians. No study was excluded due to poor quality. Detailed information of all the included studies is listed in Table 1. The results of the quality evaluation are shown in Supplement Table 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the process of selecting studies for the meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 38 studies included in the present meta-analysis.

| Author, publication year | Country | Ethnicity | Mean age of cases (year) | Male of cases (%) | No. of case/control | No. of EV infection (case/control) | Detection method | EV type | Sample source | NOS scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takita (18) | Japan | Asian | 22.7 | 100.0 | 3/17 | 3/0 | Immunostaining | VP1 | tissue | 6 |

| Kim (19) | Sydney | Mixed | 5.7 | 56.0 | 45/48 | 11/5 | RT-PCR | EV-A, EV-B | blood | 5 |

| Vehik (20) | USA | Mixed | – | – | 383/383 | 78/76 | RT-PCR | CVB | stool | 6 |

| Zargari (21) | Iran | Caucasian | 13.7 | – | 35/35 | 10/0 | ELISA | VP1 | blood | 6 |

| Federico (22) | Italy | Caucasian | 9.4 | 46.3 | 82/117 | 53/0 | Immunostaining and virus culture in cells followed by end-point PCR (59) | – | blood | 5 |

| Nekoua (23) | Benin | African | 21.8 | 40.0 | 15/8 | 11/2 | ELISA | PV1, CVB-4 | saliva or blood | 7 |

| El-Senousy (24) | Egypt | African | 9.8 | 50.0 | 382/100 | 100/0 | RT-PCR | CVB-4 | blood | 5 |

| Karaoglan (25) | Turkey | Caucasian | 8.2 | 57.5 | 40/30 | 3/0 | Serology | IVB, ECHO7, PIV4, CAV7, H3N2 CBV4 |

blood | 6 |

| Aida (26) | Japan | Asian | 61.5 | 41.7 | 12/19 | 0/0 | Immunostaining | VP1 | blood | 4 |

| Honkanen (27) | Finland | Caucasian | 11.0 | – | 97/221 | 50/86 | RT-PCR | CVA, CVB, ECHO, EV-68, EV-71, EV-90 | stool | 6 |

| Boussaid (28) | Tunisia | Afican | 19.7 | 61.1 | 95/141 | 30/11 | RT-PCR | – | blood | 7 |

| Abdel-Latif (29) | Egypt | African | 9.8 | 60.0 | 382/100 | 100/0 | RT-PCR | – | blood | 7 |

| Hodik (10) | Sweden | Caucasian | – | – | 27/24 | 15/6 | RT-PCR | – | tissue | 5 |

| Krogvold (30) | Norway | Caucasian | 28.8 | 50.0 | 6/6 | 4/0 | Immunostaining (VP1) and RT-PCR | VP1 | tissue | 4 |

| Laitinen (31) | Finland | Caucasian | – | – | 183/366 | 108/183 | Neutralization assay | CVB-1 | blood | 5 |

| Cinek (32) | Norway | Caucasian | – | – | 45/92 | 11/25 blood samples | RT-PCR | – | blood | 6 |

| Salvatoni (33) | Italy | Caucasian | 9.7 | 62.5 | 24/26 | 19/0 | Virus culture in cells followed by end-point PCR (59) | – | blood | 6 |

| Oikarinen (34) | Finland | Caucasian | 43.0 | 28.2 | 39/41 | 29/12 | Immunostaining | – | tissue | 5 |

| Schulte (39) | Netherlands | Caucasian | 9.7 | 50.0 | 10/20 | 4/0 | RT-PCR | HEV-B | blood | 4 |

| Richardson (40) | UK | Caucasian | 12.7 | – | 72/119 | 44/12 | Immunostaining | – | tissue | 4 |

| Dotta (41) | Italy | Caucasian | 13.8 | 33.3 | 6/26 | 3/0 | Immunostaining | CVB-4 | tissue | 5 |

| Oikarinen (42) | Finland | Caucasian | 32.7 | 16.7 | 12/10 | 6/0 | RT-PCR | – | tissue | 4 |

| Sarmiento (43) | Cuba | Mixed | 7.3 | 38.2 | 34/68 | 9/2 | RT-PCR | – | blood | 6 |

| Moya-Suri (44) | Germany | Caucasian | 13.0 | 51.1 | 47/50 | 17/2 | RT-PCR | CVB-4, CVB-2, CVB-6 | blood | 7 |

| Salminen (45) | Finland | Caucasian | 12.3 | 41.7 | 12/53 | 10/22 | RT-PCR | PV-3, CVA-9, CVB-3, CVB-4, CVB-5, EV-3, EV-11, EV-18, EV-24, EV-25 | blood | 7 |

| Ylipaasto (46) | Finland/Germany | Caucasian | – | 40.0 | 65/40 | 4/0 | RT-PCR | – | tissue | 5 |

| Craig (47) | Australia | Mixed | 8.1 | 38.3 | 206/160 | 62/6 | RT-PCR | EV-71 | blood or stool | 6 |

| Sadeharju (48) | Finland | Caucasian | – | – | 19/84 | 3/7 | RT-PCR | CVB-4, EV-11 | blood | 8 |

| Salminen (49) | Finland | Caucasian | – | 53.7 | 41/196 | 7/8 | RT-PCR | CVB-4, EV-11 | blood | 6 |

| Coutant (50) | France | Caucasian | – | – | 16/49 | 2/1 | RT-PCR | – | blood | 6 |

| Yin (51) | Sweden | Caucasian | 8.6 | 75.0 | 24/24 | 18/7 | RT-PCR | CVB-5, EV-5, CVB-4 | blood | 7 |

| Lönnrot (52) | Finland | Caucasian | 8.4 | 61.0 | 49/105 | 11/2 | RT-PCR | – | blood | 6 |

| Nairn (53) | UK | Caucasian | 7.1 | – | 110/182 | 30/9 | RT-PCR | PV1-3, CVA-21, CVA-24, EV-70 | blood | 7 |

| Andréoletti (54) | France | Caucasian | 28.2 | 50.0 | 12/15 | 5/0 | RT-PCR | CVB-3, CVB-4 | blood | 4 |

| Clements (55) | UK | Caucasian | 3.9 | – | 14/45 | 9/2 | RT-PCR | CVB-3, CVB-4 | blood | 6 |

| Foy (56) | UK | Caucasian | 11.0 | 58.2 | 55/42 | 22/13 | RT-PCR | – | blood | 6 |

| Buesa-Gomez (57) | USA | Mixed | 8.5 | 50.0 | 2/5 | 0/0 | RT-PCR | – | tissue | 4 |

| Foulis (58) | UK | Caucasian | – | – | 147/43 | 0/0 | Immunostaining | – | tissue | 3 |

EV, enterovirus; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; PV1, poliovirus type 1; CVB, Coxsackie virus B; VP1, enterovirus capsid protein 1; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale.

Pooled Analysis

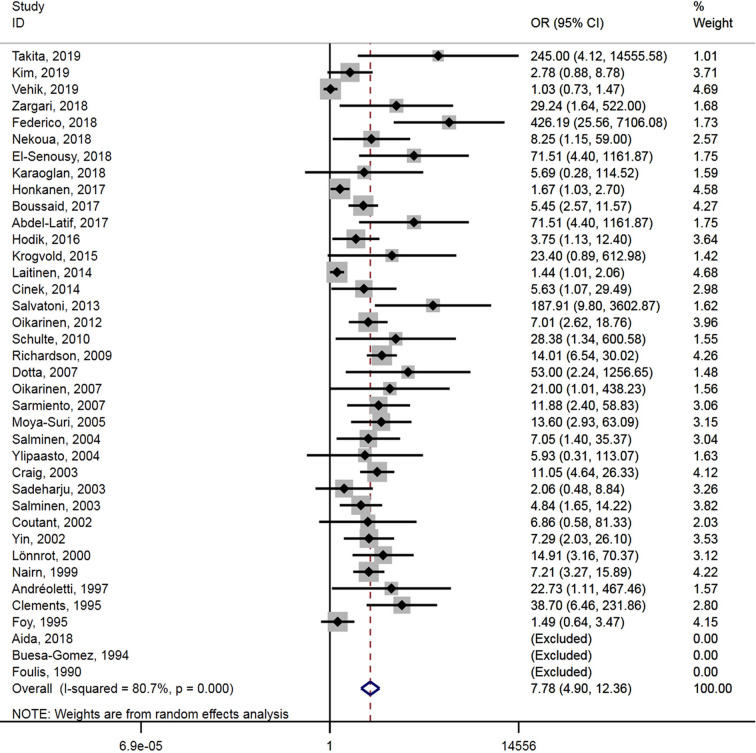

A total of 38 studies reported the association between enterovirus infection and T1D. Enterovirus infection was associated with T1D (OR = 7.8, 95% CI = 4.9–12.4, P < 0.001) (Figure 2), and substantial heterogeneity was observed among the studies (P < 0.001, I 2 = 80.7%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of ORs of enterovirus and type 1 diabetes.

Subgroup Analysis

Studies were categorized by continent, detection method, sample source, and study quality in the subgroup analysis. Enterovirus infection was correlated with T1D in the European (OR = 7.5, 95% CI = 4.4–12.6, P < 0.001), African (OR = 16.5, 95% CI = 2.8–95.1, P = 0.002), Asian (OR = 245.0, 95% CI = 4.1–15000.0, P = 0.001), Australian (OR = 5.8, 95% CI = 1.5–22.9, P = 0.011), and Latin American (OR = 11.9, 95% CI = 2.4–58.8, P = 0.002) populations. The study from North America reported no association between enterovirus and T1D, but since only one study was included, no conclusion could be reached. The association between enterovirus infection and T1D was shown in blood samples (OR = 8.8, 95% CI = 4.9–15.9, P < 0.001) and tissue samples (OR = 9.9, 95% CI = 5.5–17.8, P < 0.001), but none was detected in stool samples. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed between different detection methods and study quality (Table 2).

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis results.

| Subgroup | Number of studies | OR | 95% CI | P | Heterogeneity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | P | I2 (%) | |||||

| Continent | ||||||||

| Europe | 25 | 7.5 | 4.4 | 12.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 76.4 | |

| Africa | 4 | 16.5 | 2.8 | 95.1 | 0.002 | 0.018 | 70.2 | |

| Asia | 2 | 245.0 | 4.1 | 15,000.0 | 0.001 | 0.379 | 0.0 | |

| Australia | 2 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 22.9 | 0.011 | 0.057 | 72.3 | |

| North America | 1 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.857 | NA | NA | |

| Latin America | 1 | 11.9 | 2.4 | 58.8 | 0.002 | NA | NA | |

| Detection method | ||||||||

| RT-PCR | 26 | 6.8 | 4.1 | 11.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 78.1 | |

| Immunostaining | 7 | 15.1 | 3.5 | 65.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 89.7 | |

| ELISA | 2 | 12.3 | 2.4 | 62.6 | 0.002 | 0.449 | 0.0 | |

| Sample source | ||||||||

| Blood | 23 | 8.8 | 4.9 | 15.9 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 76.9 | |

| Tissue | 8 | 9.9 | 5.5 | 17.8 | <0.001 | 0.344 | 11.1 | |

| Stool | 2 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 0.307 | 0.115 | 59.8 | |

| Study quality | ||||||||

| NOS score ≥6 | 22 | 6.9 | 3.9 | 12.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 80.3 | |

| NOS score <6 | 13 | 11.2 | 4.3 | 29.4 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 82.9 | |

RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

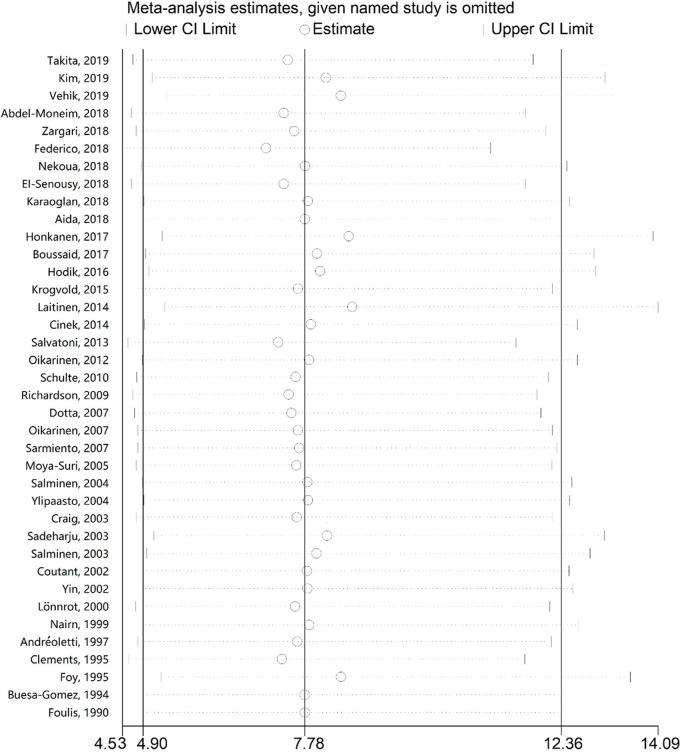

Sensitivity Analysis

In order to evaluate the influence of each study on the pooled OR, the sensitivity analysis was performed by the sequential removal of every study. The results showed no significant variation in OR, which reflected the stability and robustness of our results (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis of the association between enterovirus and type 1 diabetes. The odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between enterovirus and type 1 diabetes were recalculated by sequentially excluding each study indicated on the left.

Publication Bias

Funnel plots showed a slight asymmetry. Publication bias was indicated by P-values from Egger’s regression (P < 0.001); however, no significant publication bias was indicated by P-values from Begg’s test (P = 0.151).

Discussion

The incidence of T1D is rising in many countries. Environmental factors, especially enterovirus infection, might be involved in the initiation and acceleration of the pathogenesis of T1D (60). Although a previous meta-analysis was conducted to identify whether enterovirus infection was associated with T1D (17), the present meta-analysis consisted of the largest number of original studies and subjects available to evaluate the association. Furthermore, we conducted a subgroup analysis of the detection method and sample source, which was not performed in the previous meta-analysis.

In the present study, 38 case-control studies, consisting of 5921 subjects (2841 T1D subjects and 3080 controls) were included. The pooled analysis showed that enterovirus infection is associated with T1D, with almost 8-fold the odds of enterovirus infection in T1D compared with the controls, consistent with the previous meta-analysis (17). As the new studies included Asian and African populations, a finding of significant association in these populations suggests that the correlation with relatively high T1D rates found in European populations is also observed in other populations. Karaoglan et al. (25) investigated the serologic epidemiological and molecular evidence on enteroviruses and respiratory viruses in patients with newly-diagnosed T1D during the cold season and showed that enteroviruses and respiratory viruses, in addition to seasonal infections, could play a role in the etiopathogenesis and clinical onset of T1D. Honkanen et al. (27) evaluated whether the presence of enterovirus was associated with the appearance of islet autoimmunity in T1D and found that enterovirus infection diagnosed by detecting viral RNA was associated with the development of islet autoimmunity with an interval of several months. In the subgroup analysis, enterovirus infection was correlated with T1D in Europe, Africa, Asia, Australia, and Latin American, but no conclusion could be reached for North America. Moreover, the association between enterovirus infection and T1D was shown in blood and tissue samples, but no association was detected in stool samples, possibly because only two studies presented data from stool specimens and because stool sampling and handling are subject to more technical variability than blood, for example, especially if stool sampling is performed at home. Thus, the subgroup variability needs to be investigated in future studies. Sensitivity analysis showed that this meta-analysis results were robust, without a single study influencing the results by itself, indicating statistical stability and reliability. Still, a significant publication bias was observed in Egger’s test, suggesting a possible under-reporting of negative results or no reports from smaller centers with less experience.

Enterovirus infection is associated with the destruction of β cells (1). Two recent studies have shown that CVB1 is associated with an increased risk of β-cell autoimmunity, while CVB3 and CVB6 are associated with a reduced T1D risk (31, 61). CVB1 has been reported to infect human pancreatic islets in vitro; it is one of the most cytolytic enterovirus serotypes in this model (62). In addition, an in vivo study performed in CBS/j mice demonstrated that the CVB3 virus did not affect glucose tolerance, while CVB4 did (63). Only a few original studies in our meta-analysis have provided the enterovirus type for cases and controls, and hence, we could not establish the correlation between enterovirus type and T1D. Still, those studies (31, 61–63) suggest that different strains of enteroviruses could have different impacts on the development of T1D through variations in the genome of the viruses. One of the limitations in all these studies is the difficulty of obtaining not just the evidence of serotype but the complete enterovirus genomes from human patients at the time of T1D diagnosis. In addition, obtaining the complete genomes from stool samples is technically difficult. Future studies will have to examine more closely the strains associated with T1D as well as the genomes and mechanisms involved since the development of T1D might vary with serotypes.

Some limitations should be noted. First, the sample size is still small in this meta-analysis, especially in the subgroup analysis. Second, although some of the original studies detected the enterovirus types, most of them did not provide the number of T1D patients per enterovirus type. Therefore, we could not examine the correlation between enterovirus type and T1D. Third, although subgroup and sensitivity analyses were conducted, a source of heterogeneity was still not found, which could be attributed to the insufficient information obtained from the original studies. Fourth, the further evaluation of potential gene-gene or gene-environment interactions was limited by the insufficient original data. Despite the limitations, our meta-analysis significantly increased the statistical power based on substantial data from different studies.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that enterovirus infection is associated with T1D. This study might provide a scientific basis for identifying the infectious agents associated with T1D and for the possible prevention of T1D through vaccines and other means. Studies with a larger sample size, especially from the US and China, are needed to reach a definitive conclusion.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author Contributions

KW and FY, study design and manuscript writing. YC, data collection and data analysis. JX, data interpretation. YZ, preparation of the manuscript. YW and TL, literature analysis. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the Jinhua Science and Technology Bureau (Grant no.2020-3-036).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2021.706964/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

T1D, type 1 diabetes; CAR, coxsackie and adenovirus receptor; NOS, Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CVA, coxsackievirus type A; CVB, coxsackievirus type B.

References

- 1.Hober D, Sauter P. Pathogenesis of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Interplay Between Enterovirus and Host. Nat Rev Endocrinol (2010) 6(5):279–89. 10.1038/nrendo.2010.27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G, Group ES. Incidence Trends for Childhood Type 1 Diabetes in Europe During 1989-2003 and Predicted New Cases 2005-20: A Multicentre Prospective Registration Study. Lancet (2009) 373(9680):2027–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith TL, Drum ML, Lipton RB. Incidence of Childhood Type I and non-Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in a Diverse Population: The Chicago Childhood Diabetes Registry, 1994 to 2003. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab (2007) 20(10):1093–107. 10.1515/jpem.2007.20.10.1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levet S, Charvet B, Bertin A, Deschaumes A, Perron H, Hober D. Human Endogenous Retroviruses and Type 1 Diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rep (2019) 19(12):141. 10.1007/s11892-019-1256-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Craig ME, Kim KW, Isaacs SR, Penno MA, Hamilton-Williams EE, Couper JJ, et al. Early-Life Factors Contributing to Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetologia (2019) 62(10):1823–34. 10.1007/s00125-019-4942-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Calvo T. Enteroviral Infections as a Trigger for Type 1 Diabetes. Curr Diabetes Rep (2018) 18(11):106. 10.1007/s11892-018-1077-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tapparel C, Siegrist F, Petty TJ, Kaiser L. Picornavirus and Enterovirus Diversity With Associated Human Diseases. Infect Genet Evol (2013) 14:282–93. 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craig ME, Nair S, Stein H, Rawlinson WD. Viruses and Type 1 Diabetes: A New Look at an Old Story. Pediatr Diabetes (2013) 14(3):149–58. 10.1111/pedi.12033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baggen J, Thibaut HJ, Strating J, van Kuppeveld FJM. The Life Cycle of non-Polio Enteroviruses and How to Target It. Nat Rev Microbiol (2018) 16(6):368–81. 10.1038/s41579-018-0005-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hodik M, Anagandula M, Fuxe J, Krogvold L, Dahl-Jorgensen K, Hyoty H, et al. Coxsackie-Adenovirus Receptor Expression Is Enhanced in Pancreas From Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care (2016) 4(1):e000219. 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ifie E, Russell MA, Dhayal S, Leete P, Sebastiani G, Nigi L, et al. Unexpected Subcellular Distribution of a Specific Isoform of the Coxsackie and Adenovirus Receptor, CAR-SIV, in Human Pancreatic Beta Cells. Diabetologia (2018) 61(11):2344–55. 10.1007/s00125-018-4704-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colli ML, Nogueira TC, Allagnat F, Cunha DA, Gurzov EN, Cardozo AK, et al. Exposure to the Viral by-Product dsRNA or Coxsackievirus B5 Triggers Pancreatic Beta Cell Apoptosis via a Bim/Mcl-1 Imbalance. PLoS Pathog (2011) 7(9):e1002267. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alidjinou EK, Engelmann I, Bossu J, Villenet C, Figeac M, Romond MB, et al. Persistence of Coxsackievirus B4 in Pancreatic Ductal-Like Cells Results in Cellular and Viral Changes. Virulence (2017) 8(7):1229–44. 10.1080/21505594.2017.1284735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lietzen N, Hirvonen K, Honkimaa A, Buchacher T, Laiho JE, Oikarinen S, et al. Coxsackievirus B Persistence Modifies the Proteome and the Secretome of Pancreatic Ductal Cells. iScience (2019) 19:340–57. 10.1016/j.isci.2019.07.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Busse N, Paroni F, Richardson SJ, Laiho JE, Oikarinen M, Frisk G, et al. Detection and Localization of Viral Infection in the Pancreas of Patients With Type 1 Diabetes Using Short Fluorescently-Labelled Oligonucleotide Probes. Oncotarget (2017) 8(8):12620–36. 10.18632/oncotarget.14896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sioofy-Khojine AB, Lehtonen J, Nurminen N, Laitinen OH, Oikarinen S, Huhtala H, et al. Coxsackievirus B1 Infections Are Associated With the Initiation of Insulin-Driven Autoimmunity That Progresses to Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetologia (2018) 61(5):1193–202. 10.1007/s00125-018-4561-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yeung WC, Rawlinson WD, Craig ME. Enterovirus Infection and Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Molecular Studies. BMJ (2011) 342. 10.1136/bmj.d35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takita M, Jimbo E, Fukui T, Aida K, Shimada A, Oikawa Y, et al. Unique Inflammatory Changes in Exocrine and Endocrine Pancreas in Enterovirus-Induced Fulminant Type 1 Diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab (2019) 104(10):4282–94. 10.1210/jc.2018-02672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim KW, Horton JL, Pang CNI, Jain K, Leung P, Isaacs SR, et al. Higher Abundance of Enterovirus A Species in the Gut of Children With Islet Autoimmunity. Sci Rep (2019) 9(1):1749. 10.1038/s41598-018-38368-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vehik K, Lynch KF, Wong MC, Tian X, Ross MC, Gibbs RA, et al. Prospective Virome Analyses in Young Children at Increased Genetic Risk for Type 1 Diabetes. Nat Med (2019) 25(12):1865–72. 10.1038/s41591-019-0667-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zargari Samani O, Mahmoodnia L, Izad M, Shirzad H, Jamshidian A, Ghatrehsamani M, et al. Alteration in CD8(+) T Cell Subsets in Enterovirus-Infected Patients: An Alarming Factor for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Kaohsiung J Med Sci (2018) 34(5):274–80. 10.1016/j.kjms.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Federico G, Genoni A, Puggioni A, Saba A, Gallo D, Randazzo E, et al. Vitamin D Status, Enterovirus Infection, and Type 1 Diabetes in Italian Children/Adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes (2018) 19(5):923–9. 10.1111/pedi.12673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nekoua MP, Yessoufou A, Alidjinou EK, Badia-Boungou F, Moutairou K, Sane F, et al. Salivary Anti-Coxsackievirus-B4 Neutralizing Activity and Pattern of Immune Parameters in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: A Pilot Study. Acta Diabetol (2018) 55(8):827–34. 10.1007/s00592-018-1158-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El-Senousy WM, Abdel-Moneim A, Abdel-Latif M, El-Hefnawy MH, Khalil RG. Coxsackievirus B4 as a Causative Agent of Diabetes Mellitus Type 1: Is There a Role of Inefficiently Treated Drinking Water and Sewage in Virus Spreading? Food Environ Virol (2018) 10(1):89–98. 10.1007/s12560-017-9322-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karaoglan M, Eksi F. The Coincidence of Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus With IgM Antibody Positivity to Enteroviruses and Respiratory Tract Viruses. J Diabetes Res (2018) 2018:8475341. 10.1155/2018/8475341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aida K, Fukui T, Jimbo E, Yagihashi S, Shimada A, Oikawa Y, et al. Distinct Inflammatory Changes of the Pancreas of Slowly Progressive Insulin-Dependent (Type 1) Diabetes. Pancreas (2018) 47(9):1101–9. 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honkanen H, Oikarinen S, Nurminen N, Laitinen OH, Huhtala H, Lehtonen J, et al. Detection of Enteroviruses in Stools Precedes Islet Autoimmunity by Several Months: Possible Evidence for Slowly Operating Mechanisms in Virus-Induced Autoimmunity. Diabetologia (2017) 60(3):424–31. 10.1007/s00125-016-4177-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boussaid I, Boumiza A, Zemni R, Chabchoub E, Gueddah L, Slim I, et al. The Role of Enterovirus Infections in Type 1 Diabetes in Tunisia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab (2017) 30(12):1245–50. 10.1515/jpem-2017-0044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdel-Latif M, Abdel-Moneim AA, El-Hefnawy MH, Khalil RG. Comparative and Correlative Assessments of Cytokine, Complement and Antibody Patterns in Paediatric Type 1 Diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol (2017) 190(1):110–21. 10.1111/cei.13001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krogvold L, Edwin B, Buanes T, Frisk G, Skog O, Anagandula M, et al. Detection of a Low-Grade Enteroviral Infection in the Islets of Langerhans of Living Patients Newly Diagnosed With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes (2015) 64(5):1682–7. 10.2337/db14-1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laitinen OH, Honkanen H, Pakkanen O, Oikarinen S, Hankaniemi MM, Huhtala H, et al. Coxsackievirus B1 Is Associated With Induction of Beta-Cell Autoimmunity That Portends Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes (2014) 63(2):446–55. 10.2337/db13-0619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cinek O, Stene LC, Kramna L, Tapia G, Oikarinen S, Witso E, et al. Enterovirus RNA in Longitudinal Blood Samples and Risk of Islet Autoimmunity in Children With a High Genetic Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: The MIDIA Study. Diabetologia (2014) 57(10):2193–200. 10.1007/s00125-014-3327-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salvatoni A, Baj A, Bianchi G, Federico G, Colombo M, Toniolo A. Intrafamilial Spread of Enterovirus Infections at the Clinical Onset of Type 1 Diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes (2013) 14(6):407–16. 10.1111/pedi.12056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oikarinen M, Tauriainen S, Oikarinen S, Honkanen T, Collin P, Rantala I, et al. Type 1 Diabetes Is Associated With Enterovirus Infection in Gut Mucosa. Diabetes (2012) 61(3):687–91. 10.2337/db11-1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stang A. Critical Evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for the Assessment of the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analyses. Eur J Epidemiol (2010) 25(9):603–5. 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ (2003) 327(7414):557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating Characteristics of a Rank Correlation Test for Publication Bias. Biometrics (1994) 50(4):1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in Meta-Analysis Detected by a Simple, Graphical Test. BMJ (1997) 315(7109):629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schulte BM, Bakkers J, Lanke KH, Melchers WJ, Westerlaken C, Allebes W, et al. Detection of Enterovirus RNA in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells of Type 1 Diabetic Patients Beyond the Stage of Acute Infection. Viral Immunol (2010) 23(1):99–104. 10.1089/vim.2009.0072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Richardson SJ, Willcox A, Bone AJ, Foulis AK, Morgan NG. The Prevalence of Enteroviral Capsid Protein Vp1 Immunostaining in Pancreatic Islets in Human Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetologia (2009) 52(6):1143–51. 10.1007/s00125-009-1276-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dotta F, Censini S, van Halteren AG, Marselli L, Masini M, Dionisi S, et al. Coxsackie B4 Virus Infection of Beta Cells and Natural Killer Cell Insulitis in Recent-Onset Type 1 Diabetic Patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (2007) 104(12):5115–20. 10.1073/pnas.0700442104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oikarinen M, Tauriainen S, Honkanen T, Oikarinen S, Vuori K, Kaukinen K, et al. Detection of Enteroviruses in the Intestine of Type 1 Diabetic Patients. Clin Exp Immunol (2008) 151(1):71–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03529.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sarmiento L, Cabrera-Rode E, Lekuleni L, Cuba I, Molina G, Fonseca M, et al. Occurrence of Enterovirus RNA in Serum of Children With Newly Diagnosed Type 1 Diabetes and Islet Cell Autoantibody-Positive Subjects in a Population With a Low Incidence of Type 1 Diabetes. Autoimmunity (2007) 40(7):540–5. 10.1080/08916930701523429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moya-Suri V, Schlosser M, Zimmermann K, Rjasanowski I, Gurtler L, Mentel R. Enterovirus RNA Sequences in Sera of Schoolchildren in the General Population and Their Association With Type 1-Diabetes-Associated Autoantibodies. J Med Microbiol (2005) 54(Pt9):879–83. 10.1099/jmm.0.46015-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salminen KK, Vuorinen T, Oikarinen S, Helminen M, Simell S, Knip M, et al. Isolation of Enterovirus Strains From Children With Preclinical Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Med (2004) 21(2):156–64. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01097.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ylipaasto P, Klingel K, Lindberg AM, Otonkoski T, Kandolf R, Hovi T, et al. Enterovirus Infection in Human Pancreatic Islet Cells, Islet Tropism In Vivo and Receptor Involvement in Cultured Islet Beta Cells. Diabetologia (2004) 47(2):225–39. 10.1007/s00125-003-1297-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Craig ME, Howard NJ, Silink M, Rawlinson WD. Reduced Frequency of HLA DRB1*03-DQB1*02 in Children With Type 1 Diabetes Associated With Enterovirus RNA. J Infect Dis (2003) 187(10):1562–70. 10.1086/374742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadeharju K, Hamalainen AM, Knip M, Lonnrot M, Koskela P, Virtanen SM, et al. Enterovirus Infections as a Risk Factor for Type I Diabetes: Virus Analyses in a Dietary Intervention Trial. Clin Exp Immunol (2003) 132(2):271–7. 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02147.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salminen K, Sadeharju K, Lonnrot M, Vahasalo P, Kupila A, Korhonen S, et al. Enterovirus Infections Are Associated With the Induction of Beta-Cell Autoimmunity in a Prospective Birth Cohort Study. J Med Virol (2003) 69(1):91–8. 10.1002/jmv.10260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coutant R, Carel JC, Lebon P, Bougneres PF, Palmer P, Cantero-Aguilar L. Detection of Enterovirus RNA Sequences in Serum Samples From Autoantibody-Positive Subjects at Risk for Diabetes. Diabetes Med (2002) 19(11):968–9. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00807_2.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin H, Berg AK, Tuvemo T, Frisk G. Enterovirus RNA Is Found in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells in a Majority of Type 1 Diabetic Children at Onset. Diabetes (2002) 51(6):1964–71. 10.2337/diabetes.51.6.1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lonnrot M, Salminen K, Knip M, Savola K, Kulmala P, Leinikki P, et al. Enterovirus RNA in Serum Is a Risk Factor for Beta-Cell Autoimmunity and Clinical Type 1 Diabetes: A Prospective Study. Childhood Diabetes in Finland (DiMe) Study Group. J Med Virol (2000) 61(2):214–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nairn C, Galbraith DN, Taylor KW, Clements GB. Enterovirus Variants in the Serum of Children at the Onset of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Med (1999) 16(6):509–13. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Andreoletti L, Hober D, Hober-Vandenberghe C, Belaich S, Vantyghem MC, Lefebvre J, et al. Detection of Coxsackie B Virus RNA Sequences in Whole Blood Samples From Adult Patients at the Onset of Type I Diabetes Mellitus. J Med Virol (1997) 52(2):121–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clements GB, Galbraith DN, Taylor KW. Coxsackie B Virus Infection and Onset of Childhood Diabetes. Lancet (1995) 346(8969):221–3. 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91270-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foy CA, Quirke P, Lewis FA, Futers TS, Bodansky HJ. Detection of Common Viruses Using the Polymerase Chain Reaction to Assess Levels of Viral Presence in Type 1 (Insulin-Dependent) Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Med (1995) 12(11):1002–8. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1995.tb00413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buesa-Gomez J, de la Torre JC, Dyrberg T, Landin-Olsson M, Mauseth RS, Lernmark A, et al. Failure to Detect Genomic Viral Sequences in Pancreatic Tissues From Two Children With Acute-Onset Diabetes Mellitus. J Med Virol (1994) 42(2):193–7. 10.1002/jmv.1890420217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Foulis AK, Farquharson MA, Cameron SO, McGill M, Schonke H, Kandolf R. A Search for the Presence of the Enteroviral Capsid Protein VP1 in Pancreases of Patients With Type 1 (Insulin-Dependent) Diabetes and Pancreases and Hearts of Infants Who Died of Coxsackieviral Myocarditis. Diabetologia (1990) 33(5):290–8. 10.1007/BF00403323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Genoni A, Canducci F, Rossi A, Broccolo F, Chumakov K, Bono G, et al. Revealing Enterovirus Infection in Chronic Human Disorders: An Integrated Diagnostic Approach. Sci Rep (2017) 7(1):5013. 10.1038/s41598-017-04993-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The ‘Hygiene Hypothesis’ for Autoimmune and Allergic Diseases: An Update. Clin Exp Immunol (2010) 160(1):1–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oikarinen S, Tauriainen S, Hober D, Lucas B, Vazeou A, Sioofy-Khojine A, et al. Virus Antibody Survey in Different European Populations Indicates Risk Association Between Coxsackievirus B1 and Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes (2014) 63(2):655–62. 10.2337/db13-0620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roivainen M, Ylipaasto P, Savolainen C, Galama J, Hovi T, Otonkoski T. Functional Impairment and Killing of Human Beta Cells by Enteroviruses: The Capacity Is Shared by a Wide Range of Serotypes, But the Extent Is a Characteristic of Individual Virus Strains. Diabetologia (2002) 45(5):693–702. 10.1007/s00125-002-0805-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hindersson M, Orn A, Harris RA, Frisk G. Strains of Coxsackie Virus B4 Differed in Their Ability to Induce Acute Pancreatitis and the Responses Were Negatively Correlated to Glucose Tolerance. Arch Virol (2004) 149(10):1985–2000. 10.1007/s00705-004-0347-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.