Abstract

Over the past 50 years, intense research effort has taught us a great deal about multiple sclerosis. We know that it is the most common neurological disease affecting the young-middle aged, that it affects two to three times more females than males, and that it is characterized as an autoimmune disease, in which autoreactive T lymphocytes cross the blood–brain barrier, resulting in demyelinating lesions. But despite all the knowledge gained, a key question still remains; what is the initial event that triggers the inflammatory demyelinating process? While most research effort to date has focused on the immune system, more recently, another potential candidate has emerged: hypoxia. Specifically, a growing number of studies have described the presence of hypoxia (both ‘virtual’ and real) at an early stage of demyelinating lesions, and several groups, including our own, have begun to investigate how manipulation of inspired oxygen levels impacts disease progression. In this review we summarize the findings of these hypoxia studies, and in particular, address three main questions: (i) is the hypoxia found in demyelinating lesions ‘virtual’ or real; (ii) what causes this hypoxia; and (iii) how does manipulation of inspired oxygen impact disease progression?

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, hypoxia, blood vessels, inflammation, blood–brain barrier integrity

Halder and Milner draw on significant recent developments to review the potential role of hypoxia in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. In particular, they discuss the possible causes of this hypoxia, and the impact of manipulation of inspired oxygen on disease progression.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease that results in demyelination and axonal degeneration (Ffrench-Constant, 1994; Compston and Coles, 2008). Within multiple sclerosis patients, there is tremendous variation in how patients present, progress, and respond to different medications (Brownlee et al., 2017; Doshi and Chataway, 2017). To understand the reasons underlying this heterogeneity, 20 years ago, the Lassmann laboratory examined multiple sclerosis lesions at the histopathological level and determined that they could be segregated into four basic patterns (Lucchinetti et al., 1996, 1999, 2000). Pattern I contains inflammatory T cells and macrophages but relative preservation of oligodendrocytes. Pattern II is similar to pattern I but includes antibody and complement accumulation on degenerating myelin, suggesting an antibody-mediated process (Prineas and Graham, 1981; Storch et al., 1998). Pattern IV shows profound oligodendrocyte death at the centre of the lesion, suggesting a primary oligodendrogliopathy (Lucchinetti et al., 1996). Pattern III shows low inflammation and is characterized as a ‘dying back’ oligodendrogliopathy, in which myelin proteins concentrated at the distal end of oligodendrocyte extensions, including myelin associated glycoprotein, completely disappear, while those concentrated more centrally, including myelin basic protein and proteolipid protein, remain (Itoyama et al., 1980; Ludwin and Johnson, 1981; Lucchinetti et al., 2000). Ultimately, the destruction spreads more centrally, resulting in oligodendrocyte apoptosis. Interestingly, distal oligodendogliopathy is a characteristic feature in the cuprizone demyelination model, in which cuprizone blocks oligodendrocyte energy metabolism, providing a clue that energy deficiency may be a cause of distal oligodendrogliopathy (Ludwin and Johnson, 1981). It is also consistently found in ischaemic white matter stroke (Aboul-Enein et al., 2003). Taken with the finding that type III lesions are unique in showing high induction of hypoxia-induced factor (HIF)-1α (Aboul-Enein et al., 2003), this evidence suggests that hypoxia may be an early trigger of white matter inflammation in multiple sclerosis, at least in type III lesions.

Is the hypoxia found in demyelinating lesions ‘virtual’ or real?

Evidence of ‘virtual hypoxia’ in multiple sclerosis lesions

The idea that hypoxia may play a role in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis was first postulated many years ago (Gottlieb et al., 1990). However, it was several years later before studies described hypoxic-like injury and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide (NO) in acute multiple sclerosis lesions, suggesting that these factors trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to tissue energy deficiency (Redford et al., 1997; Aboul-Enein and Lassmann, 2005). Subsequent studies have confirmed structural and functional mitochondrial damage in acute multiple sclerosis lesions (Mahad et al., 2008), though interestingly, mitochondrial number and activity are actually increased in established inactive multiple sclerosis plaques, suggestive of increased energy demand by demyelinated axons (Witte et al., 2009). In addition, studies of axonal pathology in multiple sclerosis samples revealed marked suppression of mitochondrial respiratory chain complexes (Dutta et al., 2006), supporting the hypothesis that inflammation-associated NO or ROS inhibits mitochondrial function in chronically demyelinated axons, resulting in reduced ATP production, which is then outstripped by the increased energy demand of hyperexcitable demyelinated axons, thus creating an energy-deficient metabolic crisis, a situation termed histotoxic or ‘virtual hypoxia’ (Trapp and Stys, 2009). A large number of studies have since confirmed these findings and it is now well established that mitochondrial dysfunction or ‘virtual hypoxia’ is an important mechanism in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis (Mahad et al., 2015). Furthermore, recent evidence shows that in addition to providing an insulating membrane that wraps axons, oligodendrocytes are also metabolically coupled to axons via myelinic channels that transmit energy metabolites between the myelin sheath and the periaxonal space, implying that an energy deficit in oligodendrocytes will also negatively impact adjacent axons (Simons and Nave, 2016).

Evidence of oxygen deficiency (true hypoxia) in demyelinating lesions

Over the past 5–6 years, studies of multiple sclerosis patients and the animal multiple sclerosis model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), have demonstrated that oxygen deficiency exists within demyelinating lesions. Using pimonidazole labelling and oxygen probes, Davies et al. (2013) demonstrated marked hypoxia in the lumbar spinal cord of EAE rats, with the degree of hypoxia correlating closely with neurological deficit (Davies et al., 2013). Significantly, pO2 levels were restored to normal during disease remission but fell sharply again during relapse. Further studies from the Smith laboratory adopting a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection strategy to model the molecular events underlying development of inflammatory demyelination, demonstrated transient hypoxia at an early stage, specifically in the white-grey matter border and dorsal white column, that was associated with elevated ROS and NO, which preceded demyelination (Desai et al., 2016). Based on these findings, the authors proposed a model whereby activation of innate immune mechanisms leads to transient hypoxia in vascular watershed regions of the spinal cord, resulting in energy deficiency and subsequent oligodendrocyte death and demyelination.

Studies from the Dunn laboratory have confirmed hypoxia in demyelinating lesions both in the CNS of EAE and multiple sclerosis patients. Using susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI), Nathoo et al. (2013) showed increased levels of deoxyhaemoglobin (i.e. poorly oxygenated blood) within spinal cord and cerebellar blood vessels in EAE mice. Notably, when EAE mice received oxygen supplementation, the SWI lesions disappeared (Nathoo et al., 2015). Studies using pO2 sensors in EAE demonstrated a strong correlation between the degree of white matter inflammation and level of hypoxia (Johnson et al., 2016). More recently, using frequency domain near-infrared spectroscopy (fdNRS), Yang and Dunn (2015) demonstrated that microvascular haemoglobin oxygen saturation (StO2) in the cerebral cortex of multiple sclerosis patients was markedly decreased, closely correlating with clinical disability, strongly supporting the idea of a pathogenic role for hypoxia in multiple sclerosis progression.

What is the cause of hypoxia in multiple sclerosis lesions?

As the title of this review suggests, perhaps the critical outstanding question remains: does hypoxia lead to neuroinflammation or is it the other way around? To answer this question, we need to examine the possible causes of tissue hypoxia.

Reduced oxygen delivery

Reduced cerebral blood flow

Reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF) in multiple sclerosis patients was first demonstrated more than 35 years ago (Swank et al., 1983; Brooks et al., 1984). More recently, improved imaging techniques have enabled investigators to differentiate between demyelinating lesions, normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) and grey matter, revealing not only that CBF is reduced in all forms of multiple sclerosis (relapsing-remitting, primary progressive and clinically isolated syndrome), but also that it occurs in brain areas not yet showing demyelination (NAWM) (Law et al., 2004; Adhya et al., 2006; Varga et al., 2009; Papadaki et al., 2012). This suggests that cerebral hypoperfusion may be a universal early pathogenic event in multiple sclerosis, but what causes this reduced blood flow?

The high degree of comorbidity between vascular disease and multiple sclerosis suggests that vascular pathology may be an important predisposing factor in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis (Christiansen et al., 2010; Tettey et al., 2014; Kappus et al., 2016). This is supported by elevated levels of cardiovascular risk factors in multiple sclerosis patients, including type 1 diabetes (Bechtold et al., 2014), dyslipidaemia (Weinstock-Guttman et al., 2011), and cigarette smoking (Hedström et al., 2013), as well as increased incidence of ischaemic stroke (Capkun et al., 2015; Tseng et al., 2015). Interestingly, intimal thickening of cerebral arteries (Yuksel et al., 2019) and stiffer retinal arterioles have been described in multiple sclerosis patients (Kochkorov et al., 2009). Importantly, vasodilatory responses in cerebral arterioles are impaired in multiple sclerosis patients (Marshall et al., 2014). One proposed mechanism is that the vasoconstrictive peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1) is upregulated by reactive astrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions (Nie and Olsson, 1996; Ostrow et al., 2000), triggering arteriolar constriction. In support of this concept, ET-1 levels in blood and CSF are elevated in multiple sclerosis patients (Speciale et al., 2000; Haufschild et al., 2001), and a recent study showed that while CBF in multiple sclerosis patients was reduced by 20%, ET-1 receptor blockade restored CBF to control values (D'Haeseleer et al., 2013).

Hypoxic vulnerability due to cerebrovascular anatomy

One of the strongest arguments for a vascular cause of multiple sclerosis is that lesions tend to occur predominantly in CNS areas with a poor blood supply, including the periventricular and juxtacortical regions of the brain, optic nerve, and spinal cord white matter (Zimmerman and Netsky, 1950; DeLuca et al., 2006; Toosy et al., 2014). Most cerebral demyelinating lesions occur in the watershed areas between the anterior, middle and posterior cerebral arteries that are located at the terminal end points of arterial branches, where blood supply is weakest (Brownell and Hughes, 1962; Haider et al., 2016). In the spinal cord, lesions tend to occur in white matter tracts or in the grey–white matter border zone, areas that have the poorest blood supply (Hassler, 1966; Turnbull et al., 1966). Recently, an MRI study showed that lesions tend to occur in regions with relatively poor perfusion (Holland et al., 2012).

Blood–brain barrier disruption and oedema

Early in the evolution of a demyelinating lesion, the initial trigger, whether it be hypoxia or localized inflammation, results in blood–brain barrier breakdown (Kermode et al., 1990; Gay and Esiri, 1991). This triggers leak of serum proteins into the CNS parenchyma, causing localized oedema, which compresses microvessels, leading to ischaemia and hypoxic tissue damage.

Vascular inflammation

Studies of multiple sclerosis brain tissue demonstrate that endothelial cell activation occurs before parenchymal reaction or demyelination (Wakefield et al., 1994), suggesting that vascular dysfunction may be an early trigger of multiple sclerosis, via reduced CBF resulting in hypoxia. Activated blood vessels also trigger the clotting cascade, via downregulation of antithrombotic proteins such as thrombomodulin and upregulation of thrombotic factors, such as tissue factor and thrombin (Kopp et al., 1997; Esmon, 2005, 2012; Foley and Conway, 2016), which predisposes to thrombotic occlusion and hypoxia/ischaemia (Tomasson et al., 2009; Emmi et al., 2015).

Metabolic crisis induced by leucocyte infiltration

Active demyelinating lesions are characterized by mass infiltration of proliferating lymphocytes and monocytes, which produce high levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that amplify the inflammatory reaction (Ffrench-Constant, 1994; Compston and Coles, 2008). All this activity places high oxygen demand on the local environment. Notably, the most severe levels of hypoxia within demyelinating lesions, as indicated by HIF-1α expression, are found within inflammatory leucocytes (Le Moan et al., 2015; Halder and Milner, 2020).

Hypoxia and inflammation: a reciprocal relationship

Interestingly, in many different tissues and diseases, the link between hypoxia and inflammation extends both ways. In mice, systemic hypoxia drives vascular leakage and inflammatory cell accumulation in multiple organs along with elevated levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines (Eckle et al., 2008; Rosenberger et al., 2009; Eltzschig and Carmeliet, 2011). Likewise, humans who are exposed to high altitude hypoxia show similar responses (Hartmann et al., 2000). At the extreme end of the spectrum, acute hypoxia caused by ischaemic stroke triggers severe neuroinflammation in the brain (Yang et al., 2019). Recent studies suggest that hypoxia and inflammation are connected at the molecular level via the enzyme prolyl hydroxylase (PHD), such that when hypoxia inhibits the PHDs, this promotes signalling not only in the HIF pathways, but because PHDs also suppress NF-κB production, hypoxia also stimulates NFκB production, which drives the production of proinflammatory cytokines (Bartels et al., 2013). On the other hand, tissue inflammation is often associated with marked hypoxia, such as that seen in sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease and acute lung injury (Karhausen et al., 2004; Eckle et al., 2013; Taccone et al., 2014). It has also been postulated that the link between inflammation and hypoxia could account for the no reflow phenomenon observed in ischaemic stroke and myocardial infarction (Eltzschig and Eckle, 2011; Burrows et al., 2016). Taken with these findings in other tissues, it seems likely that in the evolution of multiple sclerosis lesions, hypoxia and inflammation have an intertwined relationship whereby transient hypoxic episodes triggered by vascular dysfunction could lead to inflammation, but equally, activation of the innate immune system could augment tissue hypoxia. These events would establish a ‘hypoxia-inflammation cycle’ as proposed by the Dunn laboratory, and efforts to break this cycle could have strong therapeutic potential in the management of multiple sclerosis (Yang and Dunn, 2019).

How does manipulation of inspired oxygen impact disease progression?

If hypoxia is a primary trigger of inflammatory demyelination, it seems logical that treating multiple sclerosis patients with supplemental oxygen should neutralize the pathogenic stimulus and provide therapeutic benefit. However, if supplemental oxygen provided such an easy fix, one would imagine this would have been discovered and implemented as a multiple sclerosis therapy many years ago, but unfortunately, that is not the case. To understand the reasons behind this, it is important to look at the history underlying this concept and examine some of the recent basic science that may provide clues as to why this may or may not be a good therapeutic option.

The clinical trials (and tribulations) of hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Fifty years ago, Boschetty and Cernoch showed that hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) alleviated clinical symptoms in 15 of 26 multiple sclerosis patients (Boschetty and Cernoch, 1970). Though this was a novel and interesting finding, unfortunately, the clinical improvements were only transient. Several years later, studies led by Neubauer suggested a positive therapeutic effect of HBOT, noting that while HBOT was not a cure, regular long-term application of HBOT ‘favorably altered the natural history of multiple sclerosis’ (Neubauer, 1978, 1980, 1985). A subsequent randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study confirmed these findings, making the important observation that ‘patients with less severe forms of disease had a more favorable and lasting response’, perhaps giving the first indication that oxygen therapy is most effective when given at an early stage of disease (Fischer et al., 1983). Disappointingly, however, a large number of follow-up studies provided mixed results, with some demonstrating transient benefits of HBOT (Pallotta, 1982; Murthy et al., 1985; Barnes et al., 1987; Oriani et al., 1990), but many failing to confirm the early positive findings (Neiman et al., 1985; Wood et al., 1985; Confavreux et al., 1986; Harpur et al., 1986; Lhermitte et al., 1986; Wiles et al., 1986). A large multicentre 2-year clinical trial also failed to demonstrate any significant long-term benefit of HBOT (Kindwall et al., 1991). Bennett and Heard (2004) performed a systematic meta-analysis review of 12 clinical trials, concluding that there was little evidence of a significant beneficial effect of HBOT, although they raised the possibility that ‘it still remains possible that HBOT is effective in a subgroup of individuals not clearly identified in the trials to date’ (Bennett and Heard, 2004). Based on the conflicting outcomes of these studies, the use of HBOT is not currently recommended for treating multiple sclerosis (Bennett and Heard, 2010).

The benefits of oxygen supplementation in animal studies

In 2013, motivated by their finding of frank hypoxia in the spinal cords of EAE rats, Davies et al. (2013) examined whether supplemental oxygen therapy impacts either the presence of spinal cord hypoxia or neurological deficit (Davies et al., 2013). This showed that after 1 h of breathing normobaric 95% oxygen, rats showed small but significant improvements in neurological score that was underpinned by the disappearance of spinal cord hypoxia. Animals maintained on supplemental oxygen for longer demonstrated clinical improvement up to Day 7. More recently, using an LPS injection strategy aimed at modelling the early molecular events underlying a multiple sclerosis lesion, the same group demonstrated spinal cord hypoxia at an early stage of lesion development (Desai et al., 2016). Interestingly, when rats were treated with 80% normobaric oxygen for 2 days immediately after LPS injection, the area of demyelination was ‘dramatically and significantly reduced or even absent’. Based on these findings, the authors concluded that ‘hypoxia emerges as a decisive constituent of the factors causing pattern III demyelination’.

The benefits of oxygen reduction in animal studies

While studies from the Smith laboratory hint at therapeutic potential of oxygen therapy (Desai et al., 2016), paradoxically, several recent animal studies have highlighted therapeutic benefit of the exact opposite, i.e. the application of mild hypoxia. Inspired by the strong neuroprotective influence of hypoxic preconditioning in animal models of ischaemic stroke (Dowden and Corbett, 1999; Miller et al., 2001; Stowe et al., 2011), the Dore-Duffy lab demonstrated that mice maintained under chronic mild hypoxic conditions (CMH; 10% O2) before EAE started, showed reduced neurological deficit (Dore-Duffy et al., 2011). Mechanistically, CMH promoted an anti-inflammatory environment in the CNS, as defined by reduced infiltrated CD4+ T lymphocytes and increased regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Esen et al., 2016).

In support of this, using a relapsing-remitting EAE model, we found that CMH preconditioning reduced peak disease severity by more than 50%, with protection maintained up to 7 weeks (Halder et al., 2018), concomitant with reduced levels of blood–brain barrier disruption, leucocyte infiltration, and demyelination. Mechanistic studies showed that CMH enhanced blood–brain barrier stability, correlating with reduced endothelial expression of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, and increased expression of tight junction proteins. Recently, we made the more clinically relevant observation that when applied to pre-existing EAE, CMH markedly accelerates clinical recovery, leading to long-term reduction in neurological deficit, correlating with significant reduction in vascular disruption, leucocyte accumulation and demyelination within spinal cord (Halder and Milner, 2020). At the molecular level, CMH reduced endothelial expression of VCAM-1 while increasing expression of tight junction proteins. Interestingly, while CMH had no impact on the extent of leucocyte infiltration at peak disease (3 days after CMH began), it profoundly enhanced apoptotic removal of infiltrated leucocytes during the remission phase. HIF-1α expression was strongest in infiltrated monocytes and this was greatly increased by CMH. These data suggest that CMH protects by enhancing vascular integrity and apoptosis of infiltrated monocytes.

What have we learnt from the oxygen manipulation studies?

Recent studies demonstrate that both reduction and enhancement of oxygen delivery improve clinical function in EAE (Desai et al., 2016; Esen et al., 2016; Halder and Milner, 2020), but how can this paradox be explained? We believe two main factors could account for this: (i) the developmental stage of inflammatory lesion when treatment is applied; and (ii) the impact of oxygen manipulation on different cell types. If hypoxia is an early trigger of at least some types of multiple sclerosis, it follows that oxygen supplementation at an early stage of lesion development could overcome this oxygen deficit, thus preventing the pathological cascade leading to demyelination. That supplemental oxygen at an early stage of lesion development dramatically reduced the extent of demyelination supports this concept (Desai et al., 2016). However, if oxygen therapy is applied at a later stage of lesion development, for instance, during the remission phase, it might fail, not just because it is too late to prevent the hypoxic-inflammatory cycle, but also because oxygen supplementation may prevent monocyte apoptosis during clinical remission (Halder and Milner, 2020). Perhaps these recent EAE findings may explain the conflicting HBOT outcomes in multiple sclerosis patients. Based on recent studies demonstrating marked suppression of EAE by mild hypoxia (Dore-Duffy et al., 2011; Esen et al., 2016; Halder et al., 2018; Halder and Milner, 2020), is there any therapeutic potential for the use of hypoxia? While CMH is an impractical therapeutic option, two possibilities worth exploring are intermittent hypoxic training (IHT), whereby short bursts of mild hypoxia are designed to confer long-term protection (Stowe et al., 2011) and hypoxia mimetics, drugs that have already shown clinical efficacy in EAE (Navarrete et al., 2018).

Conclusions

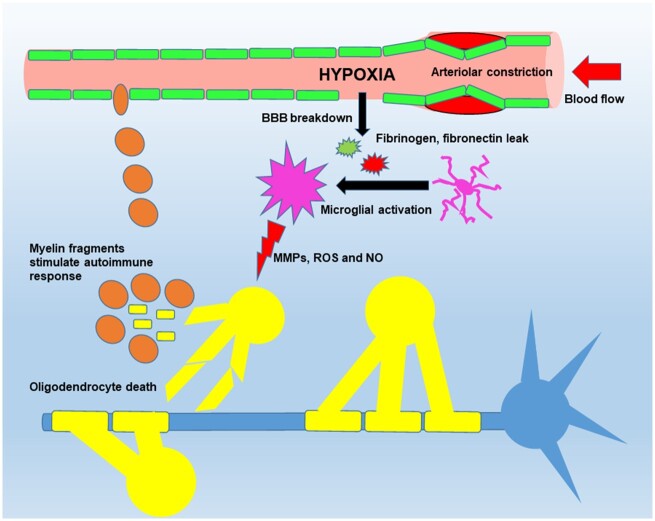

While a role for mitochondrial dysfunction (virtual hypoxia) cannot be underestimated, the presence of cerebral hypoperfusion and true oxygen deficiency have been demonstrated early in demyelinating lesions (Varga et al., 2009; Nathoo et al., 2013; Desai et al., 2016), suggesting a potential role as a primary trigger in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis or at the very least, amplifying the pathogenic effect of virtual hypoxia. So, what leads to this hypoxic state? One possibility (Fig. 1) is that cerebral hypoperfusion predisposes to hypoxia in areas with poorest blood supply, which triggers blood–brain barrier disruption, microglial activation and subsequent myelin degradation. An alternative theory suggests that activation of innate immune cells triggers vascular dysfunction, leading to ischaemia/hypoxia in the watershed areas (Desai et al., 2016). While it’s currently unclear which comes first; vascular dysfunction or inflammation, future analysis of this relationship in multiple sclerosis patients using high resolution imaging, together with mechanistic animal studies, should shed light on this important question.

Figure 1.

Model proposing a vascular trigger of hypoxia and demyelination. In this model, cerebrovascular dysfunction leads to hypoperfusion, triggering a transient hypoxic state in vulnerable areas of the CNS (vascular watershed areas), which results in blood–brain barrier (BBB) disruption and localized leak of serum proteins (fibrinogen, fibronectin and vitronectin) leading to microglial activation. The activated microglia then release cytotoxic factors (cytokines, MMPs, ROS and NO), which damage oligodendrocytes, leading to cell death and demyelination. This, in turn, triggers release of myelin antigenic fragments that stimulate T lymphocytes on surveillance, leading ultimately to a full-blown autoimmune response. MMP = matrix metalloproteinase; NO = nitric oxide; ROS = reactive oxygen species.

Is there any therapeutic potential in manipulating oxygen supply to the multiple sclerosis patient? Unsurprisingly, for a disease with heterogeneous clinical presentation and pathogenesis, to date, this has not provided a simple answer, with HBOT trials providing inconclusive results (Bennett and Heard, 2010). Recent animal studies have further muddied the waters by showing that enhanced and diminished oxygen both provide therapeutic benefit in EAE (Desai et al., 2016; Halder and Milner, 2020). However, closer inspection of these studies has provided important clues, both in suggesting that the timing of oxygen manipulation may be a critical factor in determining therapeutic outcome, and in defining the molecular mechanisms underlying this time sensitivity. These data suggest that while supplemental oxygen may provide benefit in the very early stages of lesion development by removing the hypoxic pathogenic trigger, it may prove counterproductive once the inflammatory process is in full swing, because extra oxygen could ‘fan the flames’ of the inflammatory process. With this in mind, while it seems likely that hypoxia plays a pivotal role in triggering the pathogenesis of demyelinating disease, more studies are required to determine the cause of this hypoxia, how it can be prevented or overcome, and at what time point of disease progression, manipulation of inspired oxygen might become a realistic therapeutic option in multiple sclerosis.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health R56 grant NS095753.

Competing interests

The authors report no competing interests.

Glossary

- CMH

chronic mild hypoxic conditions

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- HBOT

hyperbaric oxygen therapy

References

- Aboul-Enein F, Lassmann H. Mitochondrial damage and histotoxic hypoxia: a pathway of tissue injury in inflammatory brain disease? Acta Neuropathol 2005; 109: 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboul-Enein F, Rauschka H, Kornek B, Stadelmann C, Stefferl A, Brück W, et al. Preferential loss of myelin-associated glycoprotein reflects hypoxia-like white matter damage in stroke and inflammatory brain diseases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2003; 62: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhya S, Johnson G, Herbert J, Jaggi H, Babb JS, Grossman RI, et al. Pattern of hemodynamic impairment in multiple sclerosis: dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion MR imaging at 3.0 T. Neuroimage 2006; 33: 1029–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes MP, Bates D, Cartlidge NE, French JM, Shaw DA. Hyperbaric oxygen and multiple sclerosis: final results of a placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1987; 50: 1402–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels K, Grenz A, Eltzschig HK. Hypoxia and inflammation are two sides of the same coin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 18351–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtold S, Blaschek A, Raile K, Dost A, Freiberg C, Askenas M, et al. Higher relative risk for multiple sclerosis in a pediatric and adolescent diabetic population: analysis from DPV database. Diabetes Care 2014; 37: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M, Heard R. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 1: CD003057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M, Heard R. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for multiple sclerosis. CNS Neurosci Ther 2010; 16: 115–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschetty V, Cernoch J. [ Use of hyperbaric oxygen in various neurologic diseases. (Preliminary report)]. Bratisl Lek Listy 1970; 53: 298–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DJ, Leenders KL, Head G, Marshall J, Legg NJ, Jones T. Studies on regional cerebral oxygen utilisation and cognitive function in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1984; 47: 1182–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell B, Hughes JT. The distribution of plaques in the cerebrum in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1962; 25: 315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet 2017; 389: 1336–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrows F, Haley MJ, Scott E, Coutts G, Lawrence CB, Allan SM, et al. Systemic inflammation affects reperfusion following transient cerebral ischaemia. Exp Neurol 2016; 277: 252–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capkun G, Dahlke F, Lahoz R, Nordstrom B, Tilson HH, Cutter G, et al. Mortality and comorbidities in patients with multiple sclerosis compared with a population without multiple sclerosis: an observational study using the US Department of Defense administrative claims database. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015; 4: 546–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Farkas DK, Miret M, Sørensen HT, Pedersen L. Risk of arterial cardiovascular diseases in patients with multiple sclerosis: a population-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology 2010; 35: 267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2008; 372: 1502–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confavreux C, Mathieu C, Chacornac R, Aimard G, Devic M. [ Ineffectiveness of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in multiple sclerosis. A randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Presse Med 1986; 15: 1319–22. ]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Haeseleer M, Beelen R, Fierens Y, Cambron M, Vanbinst AM, Verborgh C, et al. Cerebral hypoperfusion in multiple sclerosis is reversible and mediated by endothelin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 5654–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies AL, Desai RA, Bloomfield PS, McIntosh PR, Chapple KJ, Linington C, et al. Neurological deficits caused by tissue hypoxia in neuroinflammatory disease. Ann Neurol 2013; 74: 815–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca GC, Williams K, Evangelou N, Ebers GC, Esiri MM. The contribution of demyelination to axonal loss in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2006; 129: 1507–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RA, Davies AL, Tachrount M, Kasti M, Laulund F, Golay X, et al. Cause and prevention of demyelination in a model multiple sclerosis lesion. Ann Neurol 2016; 79: 591–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P, Wencel M, Katyshev V, Cleary K. Chronic mild hypoxia ameliorates chronic inflammatory activity in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Adv Exp Med Biol 2011; 701: 165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi A, Chataway J. Multiple sclerosis, a treatable disease. Clin Med 2017; 17: 530–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowden J, Corbett D. Ischemic preconditioning in 18- to 20-month-old gerbils: long-term survival with functional outcome measures. Stroke 1999; 30: 1240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta R, McDonough J, Yin X, Peterson J, Chang A, Torres T, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of axonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 2006; 59: 478–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckle T, Brodsky K, Bonney M, Packard T, Han J, Borchers CH, et al. HIF1A reduces acute lung injury by optimizing carbohydrate metabolism in the alveolar epithelium. PLoS Biol 2013; 11: e1001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckle T, Faigle M, Grenz A, Laucher S, Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK. A2B adenosine receptor dampens hypoxia-induced vascular leak. Blood 2008; 111: 2024–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Carmeliet P. Hypoxia and inflammation. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 656–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eltzschig HK, Eckle T. Ischemia and reperfusion–from mechanism to translation. Nat Med 2011; 17: 1391–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmi G, Silvestri E, Squatrito D, Amedei A, Niccolai E, D'Elios MM, et al. Thrombosis in vasculitis: from pathogenesis to treatment. Thromb J 2015; 13: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esen N, Katyshev V, Serkin Z, Katysheva S, Dore-Duffy P. Endogenous adaptation to low oxygen modulates T-cell regulatory pathways in EAE. J Neuroinflammation 2016; 13: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. Coagulation inhibitors in inflammation. Biochem Soc Trans 2005; 33: 401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT. Protein C anticoagulant system–anti-inflammatory effects. Semin Immunopathol 2012; 34: 127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ffrench-Constant C. Pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1994; 343: 271–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer BH, Marks M, Reich T. Hyperbaric-oxygen treatment of multiple sclerosis. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. N Engl J Med 1983; 308: 181–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley JH, Conway EM. Cross talk pathways between coagulation and inflammation. Circ Res 2016; 118: 1392–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gay D, Esiri M. Blood-Brain Barrier Damage in Acute Multiple Sclerosis Plaques. Brain 1991; 114: 557–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb SF, Smith JE, Neubauer RA. The etiology of multiple sclerosis: a new and extended vascular-ischemic model. Med Hypotheses 1990; 33: 23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider L, Zrzavy T, Hametner S, Höftberger R, Bagnato F, Grabner G, et al. The topograpy of demyelination and neurodegeneration in the multiple sclerosis brain. Brain 2016; 139: 807–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder SK, Kant R, Milner R. Hypoxic pre-conditioning suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by modifying multiple properties of blood vessels. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2018; 6: 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder SK, Milner R. Chronic mild hypoxia accelerates recovery from pre-existing EAE by enhancing vascular integrity and apoptosis of infiltrated monocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117: 11126–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpur GD, Suke R, Bass BH, Bass MJ, Bull SB, Reese L, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in chronic stable multiple sclerosis: double-blind study. Neurology 1986; 36: 988–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann G, Tschöp M, Fischer R, Bidlingmaier C, Riepl R, Tschöp K, et al. High altitude increases circulating interleukin-6, interleukin-1 receptor antagonist and C-reactive protein. Cytokine 2000; 12: 246–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassler O. Blood supply to human spinal cord. A microangiographic study. Arch Neurol 1966; 15: 302–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haufschild T, Shaw SG, Kesselring J, Flammer J. Increased endothelin-1 plasma levels in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroophthalmol 2001; 21: 37–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedström AK, Hillert J, Olsson T, Alfredsson L. Smoking and multiple sclerosis susceptibility. Eur J Epidemiol 2013; 28: 867–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland CM, Charil A, Csapo I, Liptak Z, Ichise M, Khoury SJ, et al. The relationship between normal cerebral perfusion patterns and white matter lesion distribution in 1,249 patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2012; 22: 129–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoyama Y, Sterhberger NH, Webster HD, Quarles RH, Cohen SR, Richardson EP Jr. Immunocytochemical observations on the distribution of myelin-associated glycoprotein and myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol 1980; 7: 167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TW, Wu Y, Nathoo N, Rogers JA, Wee Yong V, Dunn JF. Gray matter hypoxia in the brain of the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model of multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2016; 11: e0167196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappus N, Weinstock-Guttman B, Hagemeier J, Kennedy C, Melia R, Carl E. Cardiovascular risk factors are associated with increased lesion burden and brain atrophy in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016; 87: 181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karhausen J, Furuta GT, Tomaszewski JE, Johnson RS, Colgan SP, Haase VH. Epithelial hypoxia-inducible factor-1 is protective in murine experimental colitis. J Clin Invest 2004; 114: 1098–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermode AG, Thompson AJ, Tofts P, MacManus DG, Kendall BE, Kingsley DP, et al. Breakdown of the blood-brain barrier precedes symptoms and other MRI signs of new lesions in multiple sclerosis. Pathogenetic and clinical implications. Brain 1990; 113: 1477–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kindwall EP, McQuillen MP, Khatri BO, Gruchow HW, Kindwall ML. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with hyperbaric oxygen. Results of a national registry. Arch Neurol 1991; 48: 195–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochkorov A, Gugleta K, Kavroulaki D, Katamay R, Weier K, Mehling M, et al. Rigidity of retinal vessels in patients with multiple sclerosis. Klin Monatsbl Augenheilkd 2009; 226: 276–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp CW, Siegel JB, Hancock WW, Anrather J, Winkler H, Geczy CL, et al. Effect of porcine endothelial tissue factor pathway inhibitor on human coagulation factors. Transplantation 1997; 63: 749–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M, Saindane AM, Ge Y, Babb JS, Johnson G, Mannon LJ, et al. Microvascular abnormality in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: perfusion MR imaging findings in normal-appearing white matter. Radiology 2004; 231: 645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Moan N, Baeten KM, Rafalski VA, Ryu JK, Coronado PER, Bedard C, et al. Hypocia inducible factor-1a in astrocytes and/or myeloid cells is not required for the development of autoimmune demyelinating disease. eNeuro 2015; 2: ENEURO.0050-14.2015–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lhermitte F, Roullet E, Lyon-Caen O, Metrot J, Villey T, Bach MA, et al. [Double-blind treatment of 49 cases of chronic multiple sclerosis using hyperbaric oxygen]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 1986; 142: 201–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti C, Brück W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. A quantitative analysis of oligodendrocytes in multiple sclerosis lesions. A study of 113 cases. Brain 1999; 122: 2279–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti C, Br�Ck W, Parisi J, Scheithauer B, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Heterogeneity of multiple sclerosis lesions: implications for the pathogenesis of demyelination. Ann Neurol 2000; 47: 707–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchinetti CF, Brück W, Rodriguez M, Lassmann H. Distinct patterns of multiple sclerosis pathology indicates heterogeneity on pathogenesis. Brain Pathol 1996; 6: 259–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwin SK, Johnson ES. Evidence for a “dying-back” gliopathy in demyelinating disease. Ann Neurol 1981; 9: 301–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad D, Ziabreva I, Lassmann H, Turnbull D. Mitochondrial defects in acute multiple sclerosis lesions. Brain 2008; 131: 1722–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2015; 14: 183–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall O, Lu H, Brisset J-C, Xu F, Liu P, Herbert J, et al. Impaired cerebrovascular reactivity in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 1275–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller BA, Perez RS, Shah AR, Gonzales ER, Park TS, Gidday JM. Cerebral protection by hypoxic preconditioning in a murine model of focal ischemia-reperfusion. Neuroreport 2001; 12: 1663–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy KN, Maurice PB, Wilmeth JB. Doube-blind randomized study of hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) versus placebo in multiple sclerosis (MS). Neurology 1985; 35: 104. [Google Scholar]

- Nathoo N, Agrawal S, Wu Y, Haylock-Jacobs S, Yong VW, Foniok T, et al. Susceptibility-weighted imaging in the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model of multiple sclerosis indicates elevated deoxyhemoglobin, iron deposition and demyelination. Mult Scler 2013; 19: 721–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathoo N, Rogers JA, Yong VW, Dunn JF. Detecting deoxyhemoglobin in spinal cord vasculature of the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mouse model of multiple sclerosis using susceptibility MRI and hyperoxygenation. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0127033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarrete C, Carrillo-Salinas F, Palomares B, Mecha M, Jiménez-Jiménez C, Mestre L, et al. Hypoxia mimetic activity of VCE-004.8, a cannabidiol quinone derivative: implications for multiple sclerosis therapy. J Neuroinflammation 2018; 15: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman J, Nilsson BY, Barr PO, Perrins DJ. Hyperbaric oxygen in chronic progressive multiple sclerosis: visual evoked potentials and clinical effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1985; 48: 497–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer RA. Treatment of multiple sclerosis with monoplace hyperbaric oxygenation. J Fla Med Assoc 1978; 65: 101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer RA. Exposure of multiple sclerosis patients to hyperbaric oxygen at 1.5–2 ATA. A preliminary report. J Fla Med Assoc 1980; 67: 498–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer RA, Barnes MP, Bates D, Cartlidge NEF, French JM, Shaw DA, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen for multiple sclerosis. Lancet 1985; 325: 810–1. [Google Scholar]

- Nie XJ, Olsson Y. Endothelin peptides in brain diseases. Rev Neurosci 1996; 7: 177–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oriani G, Barbieri S, Cislaghi G, Albonico G, Scarlato G, Mariani C. Long-term hyperbaric oxygen in multiple sclerosis: a placebo-controlled double-blind trial with evoked potentials studies. J Hyperbaric Med 1990; 5: 237–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow LW, Langan TJ, Sachs F. Stretch-induced endothelin-1 production by astrocytes. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2000; 36 (5 Suppl 1): S274–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotta R. [Hyperbaric therapy of multiple sclerosis]. Minerva Med 1982; 73: 2947–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadaki EZ, Mastorodemos VC, Amanakis EZ, Tsekouras KC, Papadakis AE, Tsavalas ND, et al. White matter and deep gray matter hemodynamic changes in multiple sclerosis patients with clinically isolated syndrome. Magn Reson Med 2012; 68: 1932–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prineas JW, Graham JS. Multiple sclerosis: capping of surface immunoglobulin G on macrophages engaged in myelin breakdown. Ann Neurol 1981; 10: 149–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redford EJ, Kapoor R, Smith KJ. Nitric oxide donors reversibly block axonal conduction: demyelinated axons are especially susceptible. Brain 1997; 120: 2149–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger P, Schwab JM, Mirakaj V, Masekowsky E, Mager A, Morote-Garcia JC, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent induction of netrin-1 dampens inflammation caused by hypoxia. Nat Immunol 2009; 10: 195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Nave KA. Oligodendrocytes: myelination and Axonal Support. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2016; 8: a020479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speciale L, Sarasella M, Ruzzante S, Caputo D, Mancuso R, Calvo MG, et al. Endothelin and nitric oxide levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurovirol 2000; 6 Suppl 2: S62–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch MK, Piddlesden S, Haltia M, Iivanainen M, Morgan P, Lassmann H. Multiple sclerosis: in situ evidence for antibody- and complement-mediated demyelination. Ann Neurol 1998; 43: 465–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe AM, Altay T, Freie AB, Gidday JM. Repetitive hypoxia extends endogenous neurovascular protection for stroke. Ann Neurol 2011; 69: 975–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swank RL, Roth JG, Woody DC Jr. Cerebral blood flow and red cell delivery in normal subjects and in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Res 1983; 5: 37–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taccone FS, Su F, De Deyne C, Abdellhai A, Pierrakos C, He X, et al. Sepsis is associated with altered cerebral microcirculation and tissue hypoxia in experimental peritonitis. Crit Care Med 2014; 42: e114–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettey P, Simpson S Jr., Taylor BV, van der Mei IA. Vascular comorbidities in the onset and progression of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2014; 347: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasson G, Monach PA, Merkel PA. Thromboembolic disease in vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2009; 21: 41–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toosy AT, Mason DF, Miller DH. Optic neuritis. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13: 83–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp BD, Stys PK. Virtual hypoxia and chronic necrosis of demyelinated axons in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng CH, Huang WS, Lin CL, Chang YJ. Increased risk of ischaemic stroke among patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2015; 22: 500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull IM, Brieg A, Hassler O. Blood supply of cervical spinal cord in man. A microangiographic cadaver study. J Neurosurg 1966; 24: 951–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga AW, Johnson G, Babb JS, Herbert J, Grossman RI, Inglese M. White matter hemodynamic abnormalities precede sub-cortical gray matter changes in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2009; 282: 28–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield AJ, More LJ, Difford J, McLaughlin JE. Immunohistochemical study of vascular injury in acute multiple sclerosis. J Clin Pathol 1994; 47: 129–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstock-Guttman B, Zivadinov R, Mahfooz N, Carl E, Drake A, Schneider J, et al. Serum lipid profiles are associated with disability and MRI outcomes in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 2011; 8: 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles CM, Clarke CR, Irwin HP, Edgar EF, Swan AV. Hyperbaric oxygen in multiple sclerosis: a double blind trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986; 292: 367–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte ME, Bø L, Rodenburg RJ, Belien JA, Musters R, Hazes T, et al. Enhanced number and activity of mitochondria in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Pathol 2009; 219: 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- , Wood J, Stell R, Unsworth I, Lance JW, Skuse N. A double-blind trial of hyperbaric oxygen in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Med J Aust 1985; 143: 238–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Hawkins KE, Doré S, Candelario-Jalil E. Neuroinflammatory mechanisms of blood-brain barrier damage in ischemic stroke. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2019; 316: C135–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Dunn JF. Reduced cortical microvascular oxygenation in multiple sclerosis: a blinded, case-controlled study using a novel quantitative near-infrared spectroscopy method. Sci Rep 2015; 5: 16477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, Dunn JF. Multiple sclerosis disease progression: contributions from a hypoxia-inflammation cycle. Mult Scler 2019; 25: 1715–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuksel B, Koc P, Ozaydin Goksu E, Karacay E, Kurtulus F, Cekin Y, et al. Is multiple sclerosis a risk factor for atherosclerosis? J Neuroradiol 2019;S0150-9861(19)30462-6. doi:10.1016/j.neurad.2019.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman HM, Netsky MG. The pathology of multiple sclerosis. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 1950; 28: 271–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]