Abstract

Aims

The genetic cause of cardiac conduction system disease (CCSD) has not been fully elucidated. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) can detect various genetic variants; however, the identification of pathogenic variants remains a challenge. We aimed to identify pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in CCSD patients by using WES and 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards and guidelines as well as evaluating the usefulness of functional studies for determining them.

Methods and results

We performed WES of 23 probands diagnosed with early-onset (<65 years) CCSD and analysed 117 genes linked to arrhythmogenic diseases or cardiomyopathies. We focused on rare variants (minor allele frequency < 0.1%) that were absent from population databases. Five probands had protein truncating variants in EMD and LMNA which were classified as ‘pathogenic’ by 2015 ACMG standards and guidelines. To evaluate the functional changes brought about by these variants, we generated a knock-out zebrafish with CRISPR-mediated insertions or deletions of the EMD or LMNA homologs in zebrafish. The mean heart rate and conduction velocities in the CRISPR/Cas9-injected embryos and F2 generation embryos with homozygous deletions were significantly decreased. Twenty-one variants of uncertain significance were identified in 11 probands. Cellular electrophysiological study and in vivo zebrafish cardiac assay showed that two variants in KCNH2 and SCN5A, four variants in SCN10A, and one variant in MYH6 damaged each gene, which resulted in the change of the clinical significance of them from ‘Uncertain significance’ to ‘Likely pathogenic’ in six probands.

Conclusion

Of 23 CCSD probands, we successfully identified pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 11 probands (48%). Functional analyses of a cellular electrophysiological study and in vivo zebrafish cardiac assay might be useful for determining the pathogenicity of rare variants in patients with CCSD. SCN10A may be one of the major genes responsible for CCSD.

Keywords: Cardiac conduction system disease, Whole exome sequencing, 2015 ACMG standards and guidelines, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-out in zebrafish, Cellular electrophysiological study

Time for primary review: 40 days

1. Introduction

Bradyarrhythmia is a common clinical finding and can be usually due to a physiologic reaction, pharmacotherapy, or advanced age. Patients with bradyarrhythmia may present with syncope, symptoms of heart failure, and rarely sudden cardiac death. The cardiac conduction system consists of the sinus node, atrioventricular (AV) node, and His-Purkinje system. Bradyarrhythmia can be categorized on the level of disturbances in the hierarchy of this system and includes sinus node dysfunction and AV conduction disturbances or blocks.1

The pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying cardiac conduction system disease (CCSD) are divided into acquired or inherited causes. Several studies showed genetic variants associated with CCSD linked to either structurally normal heart diseases or structural heart diseases.1–3 Thus, high-throughput sequencing (HTS) may be helpful in determining the causes of CCSD because of their comprehensiveness.4 Advancement of HTS has identified lots of putative variants associated with inherited cardiac disease. However, determining true pathogenicity of targeted diseases is still a major challenge.5

In 2015, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), and the College of American Pathologists reported updated standards and guidelines for the classification of sequence variants using criteria informed by expert opinion and empirical data.6 This guideline is useful for the consistent and reliable interpretation of genetic variants, but it also identifies many variants of uncertain significance, which are of limited use in medical decision-making.

Of these criteria, functional studies could be one of the powerful tools in support for disease pathogenicity.6 The gold standard for the functional analysis of ion channel variants is an electrophysiological measurement using a patch-clamp method in cell expression systems and a simulation study with mathematical models of human cardiomyocytes.7 Zebrafish is an emerging model for studying cardiac diseases, including cardiac arrhythmia, and for determining the pathogenicity of unknown genes detected by whole-exome sequencing (WES) or HTS.8,9 The recent sequencing of zebrafish has revealed that approximately 70% of human genes have functional homologs in zebrafish.10 Moreover, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-out in zebrafish can facilitate high-throughput screens for phenotypic effects with high levels of on-target efficiency and relatively off-target modifications.11,12 However, in vivo zebrafish cardiac assay using CRISPR/Cas9 systems has not been fully established for interpreting pathogenicity of human rare variants associated with CCSD.

Here, we assessed 23 probands diagnosed with early-onset CCSD with pacemaker implantation (PMI) or a family history of PMI. We used a prioritization approach with 117 arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy-related genes in conjunction with WES for these patients, and classified the variants according to the ACMG standards and guidelines. Then, we performed functional studies to re-classify guideline-based pathogenicity for these variants, using a patch-clamp method in heterologous expression systems and a simulation study for ion channel variants, and in vivo zebrafish cardiac assay for non-ion channel variants.

2. Methods

All data and supporting materials have been provided in the published article. An expanded Methods section is available in the Supplementary material online.

2.1 Study patients

The study conformed with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Medical Research at our institution. All study patients provided written informed consent before registration.

The study patients were recruited from multiple hospitals in Japan. Early-onset CCSD was defined as bradyarrhythmia occurring in individuals aged <65 years, who showed an AV block and/or a sick sinus syndrome (SSS) with PMI or a family history of PMI. In addition, we used DNA-sequencing data of 102 control subjects without electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormality.

2.2 WES and determining pathogenicity of candidate variants

WES was performed using the Illumina HiSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). We extracted variants from 117 candidate genes linked to monogenic arrhythmogenic disorders or cardiomyopathies (Supplementary material online, Table S1) and conducted standard quality control analysis. All variants were annotated by the Variant Effect Predictor version 82 and referred following in silico damaging scores: MetaSVM for missense variants; LOFTEE for protein truncating variants (PTVs); and CADD for all variants.13 Then, we interpreted these annotated variants using 2015 ACMG standards and guidelines, which provided criteria for the classification of pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants (Figure 1).6 These variants were retained if they were found in the database of arrhythmia cases in Osaka University and Nara Medical University.

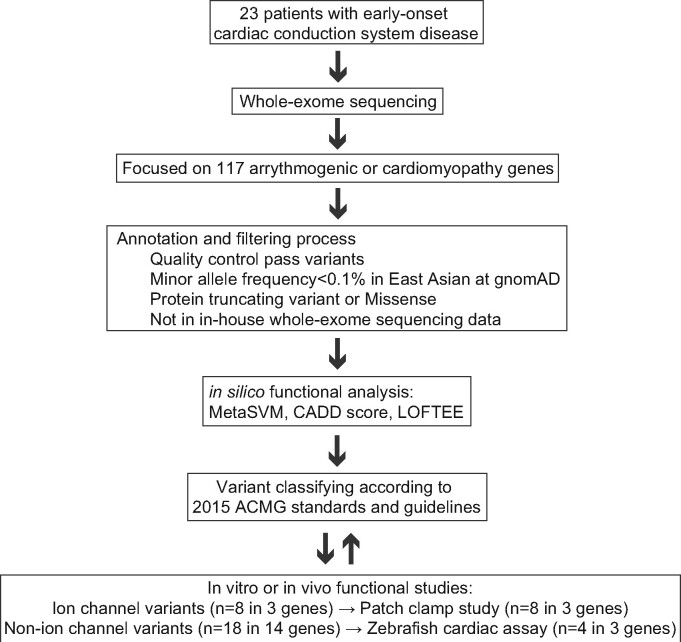

Figure 1.

Experimental workflow for determining pathogenicity of candidate variants in CCSD by targeted analysis of WES. ACMG, American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics; CADD, combined annotation dependent depletion; gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database; LOFTEE, loss-of-function transcript effect estimator; MetaSVM, in silico ensemble damaging score.

2.3 In vivo zebrafish cardiac assay

All zebrafish experiments have been approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, which is certified by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and the Bioethical Committee on Medical Research, School of Medicine, Kanazawa University. The procedures were also performed in compliance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Zebrafish euthanasia was performed following NIH and American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines using an overdose of Tricaine in combination with hypothermic shock.

The gene editing in zebrafish with CRISPR/Cas9 was conducted to evaluate detected PTV in LMNA or EMD from a patient with early-onset CCSD. Cardiac phenotypes were scored at 48 and 72 h post-fertilization (hpf), and genomic DNA was prepared from individuals for Sanger sequencing. The heart rate (HR) was visually counted at 48 hpf by using a stereomicroscope. Cardiac function was evaluated at 48 hpf by using video microscopy with upright microscope. Voltage mapping was recorded on isolated 72 hpf zebrafish hearts.14 Luciferase units were measured in CRISPR/Cas9 injected nppb: F-Luc zebrafish embryos at 5 days of post-fertilization to evaluate the expression levels of the cardiac natriuretic peptide B.15

With respect to mosaic founders (F0) with lmna knockout, they were raised and were outcrossed to a wild-type (WT) line at the age of 3 months (Supplementary material online, Figure S1). Heterozygous F1 fishes with same lmna mutation were incrossed, and cardiac phenotypes for F2 embryos were evaluated as described above. Each F2 embryo was genotyped after evaluation of the cardiac phenotype to distinguish between heterozygous and homozygous carriers. Nuclear structure of cardiomyocytes in WT lmna+/+ and homozygous lmnadel/del adult zebrafish was evaluated using immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy. The expression levels of nppb gene in lmna+/+ and lmnadel/del adult zebrafish were tested using reverse transcription and quantitative PCR.

To generate mutant lines for evaluating the F0 generation, we also used a rapid knockout method, known as acute CRISPR (aCRISPR).16 Four guide RNAs synthesized from crRNA and tracrRNA and Cas9 protein were co-injected into 1-cell stage cells, whereas the tracrRNA and Cas9 mix was injected in cells from the same clutch as controls.

To characterize a human MYH6 variant, a myh6 ATG-blocking morpholino antisense oligonucleotide (myh6 ATG-MO) (1 ng/embryo) was injected alone or co-injected with human WT or mutant MYH6 cRNA (0.4 ng/embryo) at the 1- to 2-cell stage, as described previously.17 The HR and cardiac function were evaluated at 48 hpf. Voltage mapping was recorded on isolated 72 hpf zebrafish hearts.

2.4 Plasmid constructs and electrophysiology

Mutant cDNAs were constructed by an overlap extension strategy or using a QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Mammalian cells were transfected with the cDNA encoding potassium or sodium channels and green fluorescent protein (GFP). Cells displaying green fluorescence 48–72 h after transfection were subjected to electrophysiological analysis. Rapidly activating delayed-rectifier potassium current (IKr) and fast sodium current (INa) were measured using the whole-cell patch clamp technique with an amplifier, Axopatch-200B (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), at room temperature.

2.5 Simulations of cardiac action potentials

With mathematical models of human ventricular myocytes18 and rabbit peripheral sinoatrial node (SAN) cells,19 we evaluated effects of the mutational changes in kinetic behaviour of IKr and INa on the mid-myocardial action potential configuration of the ventricular myocyte model and pacemaker activity of the peripheral SAN cell model connected to the atrial membrane model via the gap junction conductance. Dynamic behaviours of the model cell were determined by solving a system of non-linear ordinary differential equations numerically. Detailed procedures for simulations are described in the previous articles.18,19

2.6 Statistical analysis

Pooled electrophysiological data were expressed as mean ± standard error. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for the single comparisons between the two groups. One-way analysis of variance, followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test, was used to analyse data with equal variance among three or more groups. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 11.0.0 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA) and Origin 2018 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

3. Results

3.1 Clinical characteristics and molecular genetic analysis of the study cohort

The mean age of the study participants was 40 ± 16 years at the diagnosis of CCSD (Table 1). Of 23 subjects, 12 (52%) were women, 13 (57%) had SSS, 17 (74%) had AV block, and 18 (78%) underwent PMI. Thirteen (57%) had a first-degree family history of PMI. Echocardiographic data revealed a normal mean ejection fraction. Atrial fibrillation (AF) and muscular disease were complicated in 12 (52%) and 2 (10%) subjects, respectively.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with early-onset cardiac conduction system diseases

| Number of probands | 23 |

| Female (%) | 12 (52) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 40 ± 16 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 44 ± 12 |

| Sick sinus syndrome (%) | 13 (57) |

| R-S I/R-S II/R-S III | 4/7/2 |

| Atrioventricular block (%) | 17 (74) |

| I/II/III | 2/5/10 |

| Family history of PMI | 13 (57) |

| PMI (%) | 18 (78) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 12 (52) |

| LVEF (%) | 66 ± 10 |

| Muscular dystrophy | 2 (10) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PMI, pacemaker implantation; R-S, Rubenstein.

Gene analysis showed that five PTVs were identified in EMD and LMNA where loss of function is a known pathogenicity for CCSD (Table 2). These PTVs were absent from the controls in gnomAD or HGVD. Both CADD and LOFTEE indicated a deleterious effect of these PTVs on each gene (Supplementary material online, Table S2). ClinVar or HGMD classified EMD p. W226X, LMNA c. 1489-2A>G, and LMNA p. R321X into pathogenic or disease causing variants. In addition to these 5 PTVs, 1 PTV and 14 missense variants were absent from the controls, 1 PTV and 20 missense variants were considered as deleterious by in silico predictive algorithms, and 2 missense variants were classified as disease causing variants by HGMD (Table 2 and Supplementary material online, Table S2). RBM20 p.1217R was found in a male patient diagnosed with right bundle branch block (RBBB) at age 40 years and complete AV block at age 55 years in Nara Medical University. His younger brother was also diagnosed as RBBB and his grandfather died suddenly in his 70’s.

Table 2.

Pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants determined by 2015 ACMG standards and guidelines

| Gene | Base change | Amino acid change | PVS1 | PS2 | PS3 | PM2 | PP1 | PP3 | PP4 | PP5 | BS3 | Classification without PS3 (functional studies) | Classification with PS3 (functional studies) | Patient number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMD | 677G>A | W226X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | 1 | ||

| 664C>T | Q222X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | 2 | |||||

| LMNA | 339dupT | K114XfsX1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | 3 | ||||

| 1489-2A>G | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | 4 | ||||||

| 961C>T | R321X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Pathogenic | Pathogenic | 5 | ||||

| KCNH2 | 805C>T | R269W | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 7 | ||||

| SCN5A | 5470C>G | P1824A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 7 | ||||

| SCN10A | 3787C>T | R1263X | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 6 | ||||||

| 4444A>G | I1482V | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 8 | |||||

| 5455G>T | D1819Y | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 9 | |||||||

| 4118T>G | M1373R | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 9 | |||||||

| 1519T>C | F507L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 10 | |||||||

| 2413G>A | G805S | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 10 | |||||||

| MYH6 | 3347G>A | R1116H | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 11 | ||||||

| 3755G>A | R1252Q | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Likely pathogenic | 11 | |||||||

| RYR2 | 2300C>G | S767W | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 12 | |||||||

| MYH7 | 968T>C | I323T | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 10 | |||||||

| MYH11 | 4532G>A | R1511Q | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 3 | ||||||

| RBM20 | 3649G>A | G1217R | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 6 | ||||||

| TTN | 70264G>C | G23422R | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 14 | |||||||

| DES | 556G>A | D186N | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 14 | ||||||

| CBS | 1552T>C | Y518H | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 4 | ||||||

| TBX5 | 409G>A | V137M | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 7 | |||||||

| ACTC1 | 710C>T | S237F | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 8 | ||||||

| PRKAG2 | 1366C>G | R456G | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 13 | ||||||||

| MAP2K2 | 937C>T | R313W | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Uncertain significance | Uncertain significance | 3 |

PVS1: null variant (nonsense, frameshift, canonical ±1 or 2 splice sites, initiation codon, single or multiexon deletion) in a gene where LOF is a known mechanism of disease.

PS2: De novo (both maternity and paternity confirmed) in a patient with the disease and no family history.

PS3: Well-established in vitro or in vivo functional studies supportive of a damaging effect on the gene or gene product.

PM2: Absent from controls (or at extremely low frequency if recessive) in Exome Sequencing Project, 1000 Genomes Project, or Exome Aggregation Consortium.

PP1: Cosegregation with disease in multiple affected family members in a gene definitively known to cause the disease.

PP3: Multiple lines of computational evidence support a deleterious effect on the gene or gene product.

PP4: Patient’s phenotype or family history is highly specific for a disease with a single genetic aetiology.

PP5: Reputable source recently reports variant as pathogenic, but the evidence is not available to the laboratory to perform an independent evaluation.

BS3: Well-established in vitro or in vivo functional studies show no damaging effect on protein function or splicing.

ACMG, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics.

3.2 Clinical characteristics of patients with PTVs in EMD or LMNA

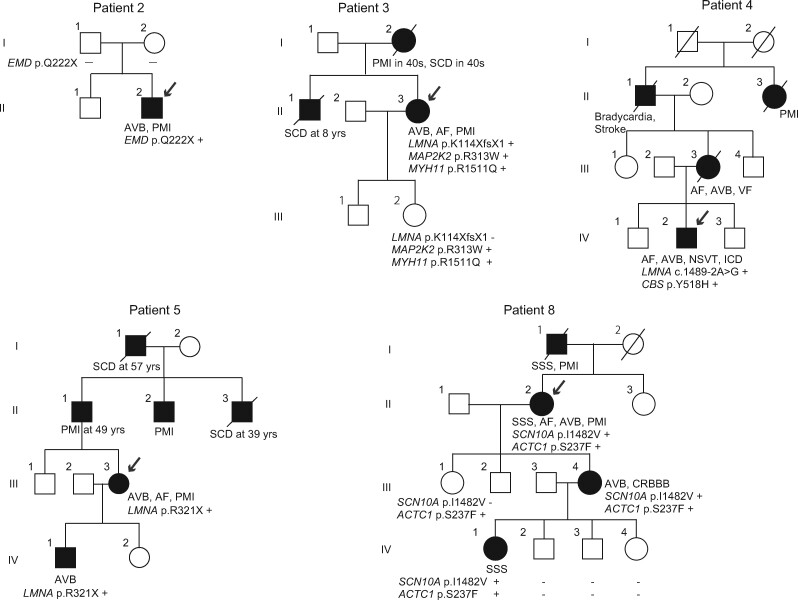

We identified two PTVs in EMD and three PTVs in LMNA (Table 2). Two patients harbouring PTVs in EMD were diagnosed with CCSD at the age of 33 and 17 years, respectively. They showed AV block and AF in addition to muscular dystrophy, and underwent PMI (Table 3).20 With regard to Patient 1 with EMD p. W226X, we previously reported an Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (EDMD) family including 16 carriers (7 men and 9 women) with EMD p. W226X. EDMD caused by EMD mutation is associated with X-linked recessive inheritance. All of the seven male carriers had cardiac involvement, and their first cardiac manifestation occurred at age 10–37 years (mean age, 20.9 years).20 In Patient 2, the segregation variant was confirmed in EMD (p. Q222X) (Figure 2). Proband’s parents did not have this variant which was classified as de novo mutation.

Table 3.

Summary of clinical characteristics of early-onset CCSD patients having with pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants

| Patient number | Gender | Age at diagnosis (years) | SSS | AV block | FH of PMI | PMI | AF | LVEF (%) | Rare variants | Classification with PS3 (functional studies) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | 33 | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 53 | EMD W226X | Pathogenic |

| 2 | Male | 17 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ | 60 | EMD Q222X | Pathogenic |

| 3 | Female | 39 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 58 |

|

Pathogenic |

| 4 | Male | 23 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 64 |

|

Pathogenic |

| 5 | Female | 44 | – | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 61 | LMNA R321X | Pathogenic |

| 6 | Male | 51 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | ✓ | 70 |

|

Likely pathogenic |

| 7 | Female | 47 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | – | 77 |

|

|

| 8 | Female | 42 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 79 |

|

Likely pathogenic |

| 9 | Female | 31 | – | ✓ | – | ✓ | – | 76 |

|

Likely pathogenic |

| 10 | Male | 17 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ | – | 60 |

|

Likely pathogenic |

| 11 | Female | 60 | ✓ | ✓ | 83 |

|

Likely pathogenic |

AF atrial fibrillation; AV block, atrioventricular block; CCSD, cardiac conduction system diseases; FH, family history; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PMI, pacemaker implantation; SSS, sick sinus syndrome.

Figure 2.

Pedigrees of family 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8. Squares and circles represent males and females, respectively. Slash marks represent deceased individuals. Black filled symbols indicate patients with a clinical diagnosis of CCSD. Open symbols represent unaffected family members. The probands are indicated by arrows. Plus and minus signs indicate positive and negative variants, respectively.

Three patients harbouring PTVs in LMNA were diagnosed with CCSD at the age of 39, 23, and 44 years, respectively. Patient 3 with LMNA K114XfsX1 was a 55-year-old woman (Table 3 and Figure 2). Her ECG showed first-degree AV block at age 39 years and sinus arrest at age 41 years. She had a family history of SCD and PMI. She received PMI at age 42 years and developed AF at 47 years. Echocardiogram showed low normal left ventricular (LV) systolic function. Patient 4 with LMNA 1489-2A>G was a 23-year-old man (Table 3 and Figure 2). His mother died suddenly due to ventricular fibrillation at the age of 50 years. His ECG showed AF and complete AV block, and received ICD therapy. Echocardiogram showed normal LV systolic function. Patient 5 with LMNA R321X was a 44-year-old woman (Table 3 and Figure 2). She had a family history of SCD and PMI. Her ECG showed paroxysmal AF at age 32 years and first-degree AV block at age 43 years. She received ICD therapy at the age of 44 years old. Echocardiogram showed normal LV systolic function.

PTVs in EMD and LMNA could be defined as pathogenic on the basis of ‘1 very strong (PVS1) and 1 Moderate (PM2) and 1 supporting by the guideline (PP1, PP3, PP4, or PP5)’ (Table 2).

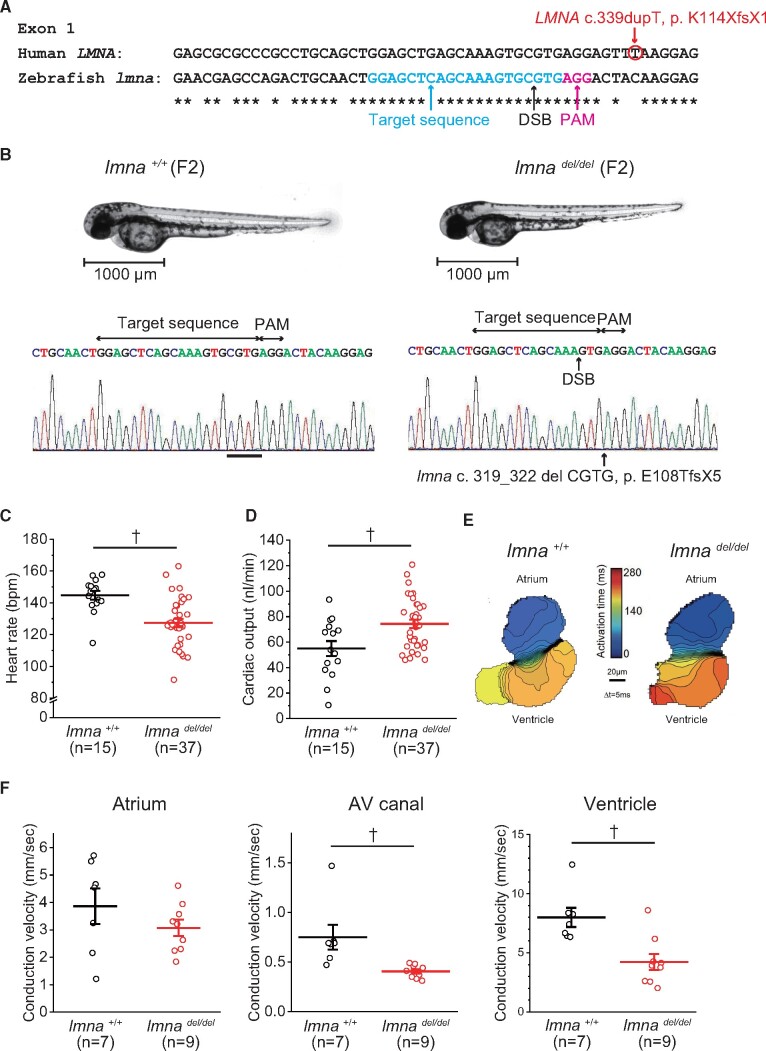

3.3 Functional studies of PTVs in LMNA and EMD using zebrafish

We studied the usefulness of in vivo zebrafish assay using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-out for interpreting PTVs associated with CCSD. At first, we evaluated the functional effect of one of PTVs, c. 339dupT, p. K114XfsX1 in LMNA. We confirmed that the human LMNA homolog, lmna (ENSDART00000191716.1), in zebrafish was present in only one copy and shared 66% identity with human LMNA. The target site was selected around the equivalent lmna site of the human LMNA c.339dupT (Figure 3A). At 48 hpf after the microinjection of only sgRNA or sgRNA and Cas9 protein, the appearance and the heart morphology of both embryos looked similar (Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). Genomic DNA was prepared from 10 individuals, and Sanger sequencing showed a variety of mutations in sgRNA+Cas9 injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). The mean HR of the sgRNA+Cas9 injected embryos at 48 hpf significantly decreased compared with those of sgRNA injected or non-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S2B). Voltage mapping on isolated 72 hpf zebrafish hearts showed that the mean conduction velocities of the ventricle (mm/s) were significantly decreased in the sgRNA+Cas9 injected embryos compared with sgRNA injected embryos (8.0 ± 1.2 vs.16.8 ± 2.6; P < 0.01) (Supplementary material online, Figure S2C).

Figure 3.

Functional studies of LMNA c.339dupT using F2 zebrafish embryos with lmna deletion mutation. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of human LMNA and zebrafish lmna. DSB, double-strand break; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif. (B) Representative images illustrating the morphology of 2 dpf lmna+/+ (wild-type) and lmnadel/del mutants, and Sanger sequence of lmna gene. (C) HR of lmna+/+ (n = 15) and lmnadel/del mutants (n = 37). (D) Cardiac output of lmna+/+ (n = 15) and lmnadel/del mutants (n = 37). (E) Isochronal map of lmna+/+ and lmnadel/del mutants summarizing the regional spread of electrical activity across the atrium and into the ventricle. The lines represent the positions of the action potential wavefront at 5-ms intervals. The colour scale depicts the timing of electrical activation (blue areas activated before red areas). (F) Mean estimated conduction velocities at the atrium, AV, atrioventricular canal, and ventricle of lmna+/+ (n = 7) and lmnadel/del mutants (n = 9). Regions of interest was placed at middle of atrium, AV canal, or ventricle. †P < 0.01.

We also evaluated F2 zebrafish embryos. Sequencing analysis of F1 fish after outcross between mosaic founders (F0) and WT fishes showed various truncating indels. Of 10 genotyped F1 fishes, 6 had heterozygous lmna c. 319_322 del CGTG, p. E108TfsX5, which caused a premature stop codon (1 male and 5 females) (Supplementary material online, Figure S3). The guide RNA design checker revealed a potential off-target site in herc1, to which 2 mismatches in the gRNA design were compared (Supplementary material online, Figure S4A). No mutation was found in the potential off-target site of the 10 genotyped F1 fishes (Supplementary material online, Figure S4B). The appearance and the heart morphology of both F2 embryos looked similar (Figure 3B). The mean HR of lmnadel/del significantly decreased compared with those of lmna+/+ (Figure 3C). The evaluation of cardiac function using video microscopy showed that the mean stroke volume, mean cardiac output, and the mean fractional area change of lmnadel/del significantly increased compared with those of lmna+/+ (Table 4 and Figure 3D). Voltage mapping on isolated 72 hpf zebrafish hearts showed that mean conduction velocities of both AV canal and ventricle were significantly decreased in lmnadel/del compared with lmna+/+ (Table 4 and Figure 3F). Immunostaining analyses demonstrated that both atrial and ventricular cardiomyocytes of lmnadel/del displayed abnormal nuclear structures compared with those of lmna+/+ (Supplementary material online, Figure S5A). The mRNA expression levels of nppb gene were significantly higher in lmnadel/del compared with lmna+/+ (Supplementary material online, Figure S5B).

Table 4.

The evaluation of cardiac function at 48 hpf and conduction velocity at 72 hpf of the F2 embryos of lmna+/+ and lmnadel/del

| lmna +/+ | lmna del/del | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac function | n = 15 | n = 37 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 145 ± 11 | 127 ± 15† |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 0.39 ± 0.18 | 0.59 ± 0.15† |

| Cardiac output (mL/min) | 54.97 ± 22.85 | 74.35 ± 19.70† |

| Fractional area change (%) | 26.88 ± 8.72 | 38.87 ± 9.26† |

| Conduction velocity | n = 7 | n = 9 |

| Atrium (mm/s) | 3.86 ± 0.64 | 3.07 ± 0.30 |

| Atrioventricular canal (mm/s) | 0.75 ± 0.12 | 0.40 ± 0.02† |

| Ventricle (mm/s) | 7.99 ± 0.81 | 4.23 ± 0.68† |

P < 0.01 vs. lmna+/+.

We also confirmed the functional effect of another PTV, c. 961C>T, p. R321X in LMNA using the aCRISPR method for directed knockdown in F0 fish (Supplementary material online, Figure S6). Sanger sequencing revealed various mutations in the lmna aCRISPR embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S6B). The mean HR of the lmna aCRISPR embryos was significantly decreased compared with that of tracrRNA-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S6C and Table S3). The mean cardiac output of the lmna aCRISPR embryos was comparable to that of the tracrRNA-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S6D and Table S3). The mean conduction velocities of the ventricle were significantly decreased in the lmna aCRISPR embryos compared with that in the tracrRNA-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S6E and F and Table S3). Normalized luciferase units in the lmna aCRISPR embryos were comparable to those of the tracrRNA-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S7A).

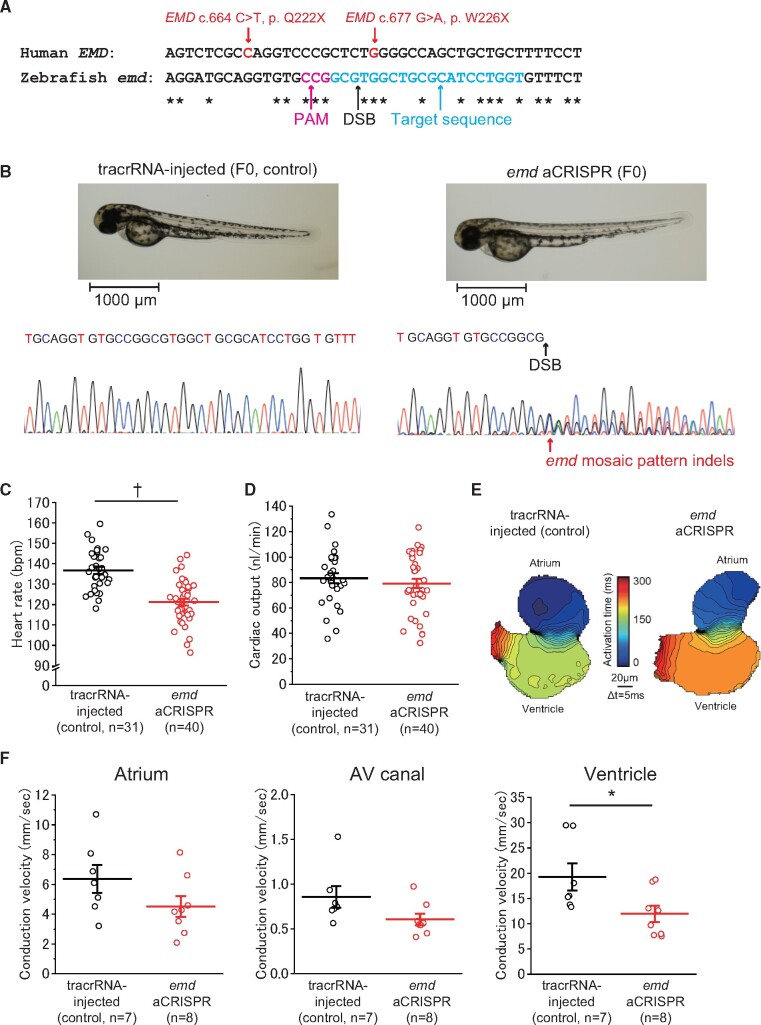

We next confirmed the functional effect of PTVs (p. Q222X and p. W226X) in EMD using the aCRISPR method (Figure 4). We evaluated the human EMD homolog using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. We confirmed that emd (ENSDART00000193281.1) in zebrafish is present in only one copy of human EMD and shared 45% identity with human EMD. The appearance and the heart morphology of both the emd aCRISPR and tracrRNA-injected embryos at 48 hpf was similar (Figure 4B). Sanger sequencing showed various mutations in the emd aCRISPR embryos (Figure 4B). The mean HR of the emd aCRISPR embryos was significantly decreased compared with that of the tracrRNA-injected embryos (Figure 4C and Table 5). The mean cardiac output of the emd aCRISPR embryos was comparable to those of the tracrRNA-injected embryos (Figure 4D and Table 5). The mean conduction velocities of the ventricle were significantly decreased in the emd aCRISPR embryos compared with that in the tracrRNA injected embryos (Figure 4E and F, and Table 5). Normalized luciferase units in the emd aCRISPR embryos were comparable to those of the tracrRNA-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S7B).

Figure 4.

Functional studies on EMD p. Q222X and p. W226X using CRISPR-mediated deletions of the human EMD ortholog, emd, in zebrafish. (A) Multiple sequence alignment of human EMD and zebrafish emd. (B) Representative images illustrating the morphology of 2 dpf emd aCRISPR and tracrRNA-injected embryos and Sanger sequence of emd gene. (C) HR of tracrRNA-injected (n = 31) and emd aCRISPR (n = 40) embryos. (D) Cardiac output of tracrRNA-injected (n = 31) and emd aCRISPR (n = 40) embryos. (E) Isochronal map of tracrRNA-injected and emd aCRISPR embryos summarizing the regional spread of electrical activity across the atrium and into the ventricle. (F) Mean estimated conduction velocities at the atrium, AV canal, and ventricle of tracrRNA-injected (n = 7) and emd aCRISPR (n = 8) embryos. Regions of interest was placed at the middle of the atrium, AV canal, or ventricle. †P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

Table 5.

The evaluation of cardiac function at 48 hpf and conduction velocity at 72 hpf of the F0 emd aCRISPR and tracrRNA- injected embryos

| tracrRNA-injected (control) | emd aCRISPR | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac function | n = 31 | n = 40 |

| Heart rate (b.p.m.) | 137 ± 10 | 121 ± 11† |

| Stroke volume (mL) | 0.61 ± 0.16 | 0.65 ± 0.17 |

| Cardiac output (mL/min) | 83.34 ± 21.45 | 79.25 ± 22.86 |

| Fractional area change (%) | 37.94 ± 7.62 | 37.10 ± 9.75 |

| Conduction velocity | n = 7 | n = 8 |

| Atrium (mm/s) | 6.37 ± 2.48 | 4.52 ± 1.99 |

| Atrioventricular canal (mm/s) | 0.86 ± 0.32 | 0.61 ± 0.18 |

| Ventricle (mm/s) | 19.26 ± 7.12 | 11.97 ± 4.58* |

P < 0.01 or *P < 0.05 vs. tracrRNA injected.

3.4 Clinical characteristics of a patient harbouring both rare missense variants in KCNH2 and SCN5A and the functional properties of the variants by cellular electrophysiological analysis

Furthermore, we sought to define the functional effect of 2 rare missense variants classified as ‘uncertain significance’ by the guideline in KCNH2 and SCN5A.

Patient 7 with SCN5A P1824A and KCNH2 R269W was a 47-year-old woman.21 Her ECG showed SA block, AV block, and marked QT prolongation (HR 56/min, QTc 0.56 s). Holter ECG monitoring revealed a 4.5 s pause with transient loss of consciousness. She had a family history of PMI and considered to be an indication for PMI. Echocardiogram showed normal LV systolic function.

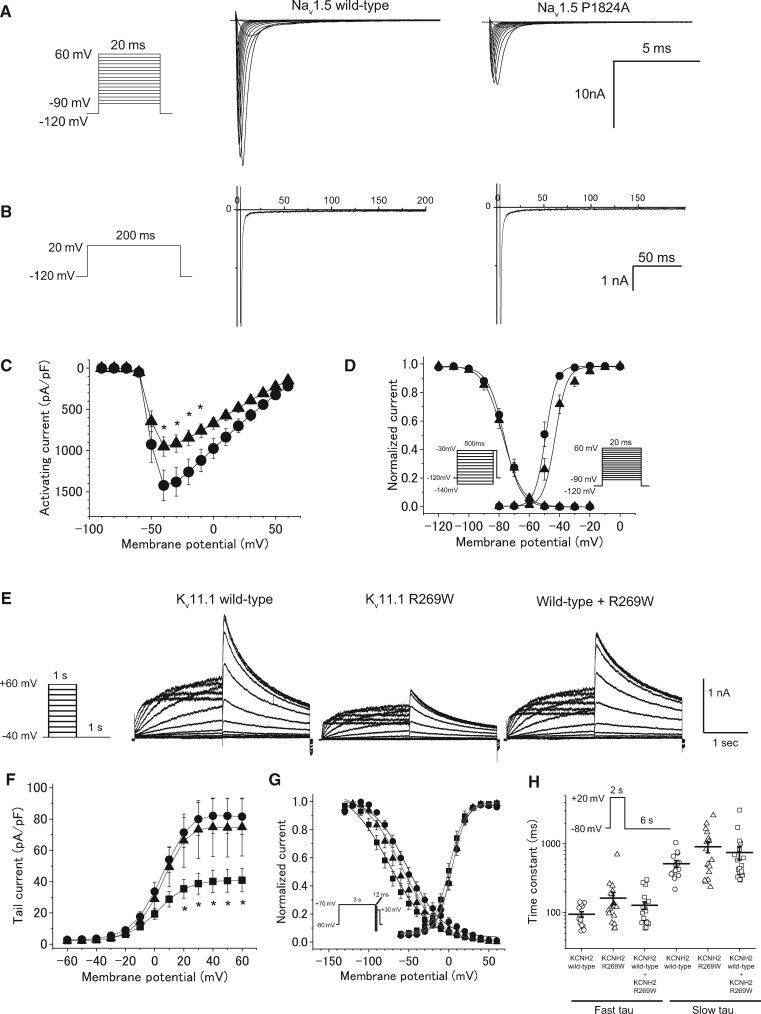

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing WT or P1824A cDNA and the human beta1 subunit cDNA in combination with a bicistronic plasmid encoding GFP. Compared with the WT Nav1.5 channel, P1824A significantly reduced the peak sodium current density (Figure 5A, C and Table 6). No difference was found in persistent sodium current between WT (0.50 ± 0.07% of peak) and P1824A (0.30 ± 0.07% of peak) (Figure 5B). The voltage dependence of steady-state activation of P1824A was significantly shifted in depolarizing (+5.7 mV) directions (Figure 5D and Table 6). No significant difference was observed in the voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Functional properties of Nav1.5 channel and Kv11.1 channel in a patient with SCN5A P1824A and KCNH2 R269W. (A) The voltage protocol and representative whole-cell Na+ currents of the wild-type and P1824A Nav1.5 channels. (B) Comparison of late Na+ currents. The late Na+ currents were measured at the end of 200-ms depolarizing pulses, as shown in the inset. (C) I–V relationships for peak currents in HEK293 cells transfected with wild-type (closed circle, n = 23) and P1824A (closed triangle, n = 21). *P < 0.05 vs. wild-type. (D) The voltage protocols and the voltage dependence of steady-state fast inactivation and activation for wild-type (n = 19 and 23) and P1824A (n = 14 and 21). (E) The voltage protocol and representative expressed currents in CHO-K1 cells transfected with Kv11.1 wild-type alone, Kv11.1 R269W, and wild-type plus R269W. (F) I–V relationships for tail currents in CHO-K1 cells transfected with wild-type alone (closed circle, n = 19), R269W (closed square, n = 17), and wild-type plus R269W (closed triangle, n = 12). *P < 0.05 vs. wild-type. (G) The voltage protocols and normalized steady-state activation and inactivation curves for wild-type alone (n = 19 and 7), R269W (n = 17 and 10), and wild-type plus R269W (n = 12 and 9). (H) The voltage protocol and fast and slow components of deactivation time constants as a function of test potentials for wild-type alone (n = 15), R269W (n = 18), and wild-type plus R269W (n = 20). The deactivation process was fit to biexponential functions.

Table 6.

Biophysical properties of wild-type and P1824A Nav1.5 channels, and wild-type and R269W Kv11.1 channels

| Nav1.5 |

Kv11.1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | P1824A | Wild-type | R269W | Wild-type /R269W | |||

| Cells (n) | 23 | 21 | 19 | 17 | 12 | ||

| Peak INa (pA/pF) | -1485 ± 186 | -846 ± 131* | — | — | — | ||

| The maximum tail current (pA/pF) | — | — | 84.2 ± 11.2 | 41.3 ± 7.4* | 75.7 ± 18.7 | ||

| Activation | V1/2 (mV) | -49.5 ± 1.1 | -43.8 ± 1.7* | 3.8 ± 1.8 | 0.5 ± 2.3 | 3.9 ± 2.1 | |

| SF (mV) | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.5* | 7.9 ± 0.3 | 8.7 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.4 | ||

| Cells (n) | 19 | 14 | 7 | 10 | 9 | ||

| Inactivation | V1/2 (mV) | -75.9 ± 1.2 | -76.6 ± 1.9 | -50.1 ± 4.5 | -80.8 ± 8.6* | -63.0 ± 4.8 | |

| SF (mV) | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | 20.9 ± 1.9 | 21.7 ± 1.7 | 19.7± 0.7 | ||

| Cells (n) | — | — | 17 | 19 | 21 | ||

| Deactivation | τfast, -80 (ms) | — | — | 83.4 ± 10.6 | 162.3 ± 32.8 | 121.0 ± 16.2 | |

| τslow, -80 (ms) | — | — | 514.0 ± 58.4 | 907.6 ± 166.2 | 747.0 ± 163.1 | ||

SF, Slope factor;

P<0.05 vs. wild-type.

Then, CHO-K1 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing WT (0.5 μg), R269W (0.5 μg), or WT (0.5 μg) + R269W (0.5 μg) in combination with the plasmid encoding GFP (Figure 5E). Electrophysiological studies showed that the maximum tail current of R269W was significantly smaller than that of WT (P < 0.05) (Figure 5F and Table 6). The maximum tail current of WT + R269W was comparable to that of WT alone. No significant difference in activation and deactivation kinetics was observed among three channels (Figure 5G and H, Table 6). The steady-state inactivation of R269W was significantly shifted in its voltage dependence to a negative potential compared with that of WT (Figure 5G and Table 6).

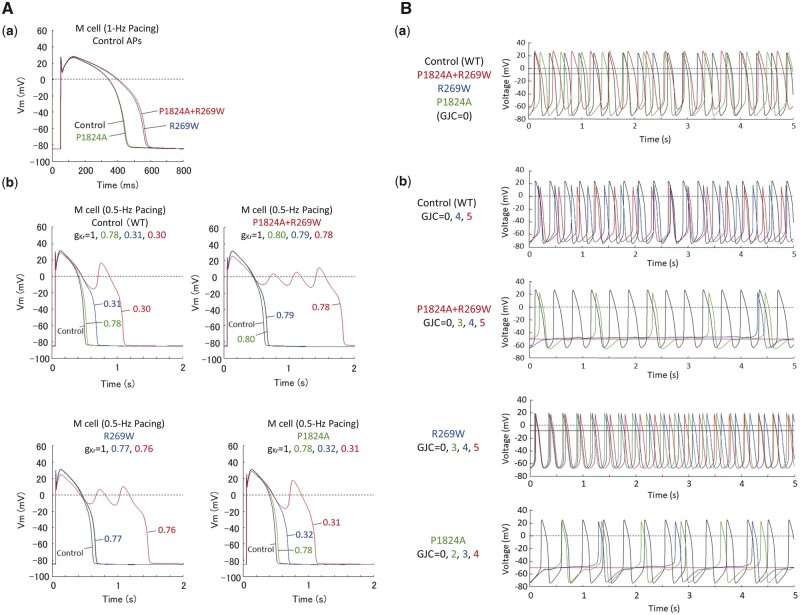

Simulation study showed that the mutational changes (by KCNH2 R269W+SCN5A P1824A) in the conductance and activation/deactivation/inactivation kinetics of IKr and INa prolonged the mid-myocardial action potential duration by 32% in the patient model of human ventricular myocytes paced at 1 Hz (Figure 6A-a). The normal, patient (double mutation), R269W single mutation and P1824A single mutation models exhibited early afterdepolarizations when IKr was reduced by 70%, 22%, 24%, and 69%, respectively (Figure 6A-b). The results also showed that the mutational changes slowed pacemaking in the patient peripheral SAN cell model (Figure 6B-a). Increasing GJC caused arrhythmic dynamics (skipped beat runs) and cessation of pacemaker activity in the patient and P1824A single mutation models, but not in the normal or R269W single mutation model (Figure 6B-b).

Figure 6.

Computer simulation of the effects of modified kinetic behaviour of Kv11.1 and Nav1.5 currents on electrophysiological properties of human ventricular myocytes (mid-myocardial cells) and electrotonic effects of atrial myocytes on pacemaker activity of peripheral sinoatrial node (SAN) cells in a normal subject and a patient with modified Kv11.1 and Nav1.5 currents. (A) Simulated action potentials of ventricular mid-myocardial cell models for a normal subject and patient with modified Kv11.1 and Nav1.5 currents (A—a). The model cells were paced at 1 Hz by 1-ms stimuli of 60 pA/pF for 30 min; steady-state behaviours after the last stimulus are shown. Modified inactivation/deactivation kinetics of R269W (KCNH2 R269W), P1824A (SCN5A P1824A), and P1824A+R269W (KCNH2 R269W and SCN5A P1824A) prolonged action potential duration at 90% repolarization (APD90) from 400 to 517, 404, or 526 ms, respectively. Effects of IKr block on action potentials were also determined for the control and patient models, and those with KCNH2 or SCN5A single mutation (A—b). (B) Simulated spontaneous action potentials in peripheral SAN cell models for the control, patient, and KCNH2 or SCN5A single mutation (B—a). Action potentials were also computed for each SAN model cell connected to an atrial cell with gap junction conductance (GJC) of 0–5 nS (B—b), as described previously.23

3.5 Clinical characteristics of patients with rare PTV and missense variants in SCN10A, and electrophysiological studies for these variants

We found one PTV and 5 rare missense variants classified as ‘uncertain significance’ by the guideline in SCN10A in 4 of 23 patients with CCSD (Table 3). Patient 6 with SCN10A R1263X showed paroxysmal AF at age 49 years. He had a sinus pause of 3.6 s following termination of AF on his monitoring ECG at age 51 years, and received PMI. Patient 8 with SCN10A I1482V was diagnosed as SSS, AV block, and AF at age 42 years (II-2 in the Figure 2). She received PMI at the age of 56 years old. The SCN10A I1482V was also found in her daughter (III-4) and grandchild (IV-1) who showed AV block and SSS, respectively, and was not found in family members with a normal ECG (III-1, IV-2, 3, and 4). Patient 9 with SCN10A D1819Y and M1373R had AV block at age 31 years. She developed syncope at age 36 years and received PMI. Patient 10 with SCN10A F507L and G805S was a 17-year-old man who had SSS and received PMI. Echocardiogram of these four patients showed normal LV systolic function.

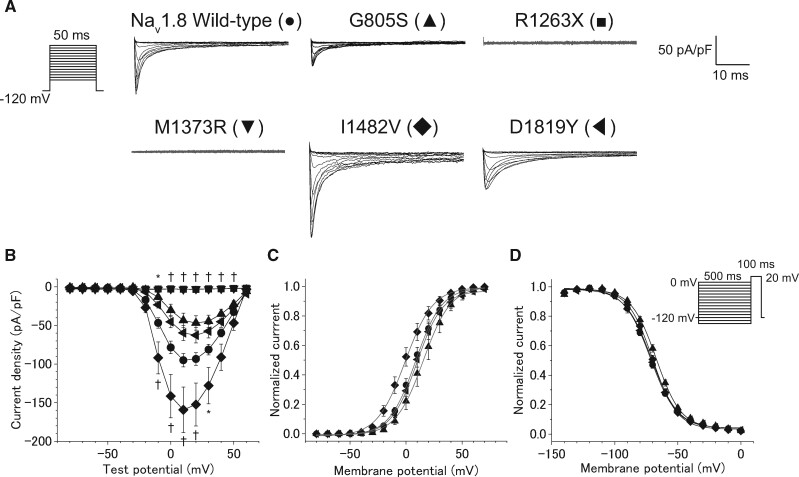

ND7/23 cells were transiently transfected with vectors expressing WT, G805S, F507L, R1263X, M1373R, I1482V, or D1819Y SCN10A cDNA in the plasmid encoding GFP. Figure 7A and Supplementary material online, Figure S8A show representative current traces recorded for these WT and rare variant Nav 1.8 channels. Neither R1263X nor M1373R generated sodium currents, whereas WT, G805S, F507L, I1482V, and D1819Y generated sodium currents. Compared with the WT, I1482V significantly increased the peak current density (Figure 7A and B, and Table 7). The voltage dependence of steady-state activation of I1482V was significantly shifted by 8.9 mV in hyperpolarizing directions (Figure 7C and Table 7). G805S variant decreased the peak sodium current density, and caused a significant depolarizing shift (+4.5 mV) in the voltage-dependence of inactivation (Figure 7D and Table 7).

Figure 7.

The functional consequence of five variants in SCN10A assessed by whole-cell patch clamp recording. (A) The voltage protocol and representative current traces of Nav 1.8 using wild-type and mutant channels. (B) I–V relationships for peak currents in ND 7/23 cells transfected with SCN10A wild-type (●, n = 64) and five variants including G805S (▲, n = 15), R1263X (■, n = 15), M1373R (▼, n = 19), I1482V (◆, n = 25), and D1819Y (◀, n = 24). *P < 0.05 or †P < 0.01 vs. wild-type by one-way ANOVA, followed by a Bonferroni post hoc test. (C) Normalized steady-state activation curves of SCN10A wild-type (n = 64), and three variants including G805S (n = 15), I1482V (n = 25), and D1819Y (n = 24). (D) The voltage protocols and normalized steady-state inactivation curves of SCN10A wild-type (n = 33) and three variants including G805S (n = 13), I1482V (n = 23), and D1819Y (n = 22).

Table 7.

Biophysical properties of wild-type, G805S, R1263X, M1373R, I1482V, and D1819Y Nav1.8 channels

| Wild-type | G805S | R1263X | M1373R | I1482V | D1819Y | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells (n) | 64 | 15 | 15 | 19 | 25 | 24 | |

| Peak INa (pA/pF) | -101.0 ± 8.9 | -49.2 ± 9.5 | -4.5 ± 0.4* | -4.8 ± 0.5* | -162.9 ± 30.3† | -63.3± 9.9 | |

| Activation | V1/2 (mV) | 9.8 ± 2.3 | 16.2 ± 3.8 | — | — | 0.9 ± 3.0* | 12.2 ± 3.0 |

| SF (mV) | -8.9 ± 0.3 | -8.7 ± 0.4 | — | — | -8.2 ± 0.4 | -9.6 ± 0.4 | |

| Cells (n) | 33 | 13 | 23 | 22 | |||

| Inactivation | V1/2 (mV) | -71.7 ± 1.0 | -67.2 ± 1.1* | — | — | -70.2 ± 1.2 | -71.6 ± 1.7 |

| SF (mV) | 10.0 ± 0.3 | 9.6 ± 0.4 | — | — | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.3 | |

SF, Slope factor;

P<0.05 vs. wild-type;

P<0.01 vs. wild-type.

3.6 Clinical characteristics of a patient with rare missense variants in MYH6, and functional study of one MYH6 variant using zebrafish

Patient 11 with MYH6 R116H and R1252Q was a 60-year-old woman who had SSS and dizziness. Her three sisters also showed bradycardia and her cousin had undergone PMI. Echocardiogram showed normal LV systolic fraction. We performed targeted myh6 knockdown with ATG-MO. Most embryos with myh6 MO knockdown showed a swollen pericardial sac (Supplementary material online, Figure S9A). Myh6 morphants (n = 73) showed a significantly slower HR compared with non-injected embryos (n = 75) as described previously.17 Co-injection of MYH6 WT (n = 69) or R1252Q cRNA (n = 70) increased HR to the extent of non-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S9B). Interestingly, cardiac oedema was rarely seen in MYH6 WT cRNA-injected embryos compared with MYH6 R1252Q cRNA-injected embryos (Supplementary material online, Figure S9A). The mean stroke volume and cardiac output of the myh6 MO-injected embryos were significantly reduced compared with those of the non-injected embryos. Co-injection of MYH6 WT RNA partially rescued the decreased mean stroke volume and cardiac output, while co-injection of MYH6 R1252Q cRNA did not (Supplementary material online, Figure S9C and D, and Table S4). The mean conduction velocities of the ventricle were significantly decreased in the myh6 MO-injected embryos. Co-injection of MYH6 WT cRNA partially rescued the reduced mean conduction velocities, while co-injection of MYH6 R1252Q cRNA did not, and showed significantly reduced conduction velocities compared with the control (Supplementary material online, Figure S9E and Table S4).

3.7 Classification of rare variants in consideration of functional studies

Above functional studies for 13 rare variants demonstrated that 11 rare variants in LMNA, EMD, KCNH2, SCN5A, SCN10A, and MYH6 could have damaging effects on each target gene (PS3), and two rare variants in SCN10A might not exert similar effects (BS3) (Table 2). Of those, seven variants changed their clinical significance from ‘uncertain significance’ to ‘likely pathogenic’ when added the functional study results: ‘1 strong (PS3) and 1 Moderate (PM2)’ or ‘1 strong (PS3) and ≥2 supporting (PP3, PP4, and/or PP5)’ (Table 2).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we analysed 23 patients with CCSD for rare variants in arrhythmia and/or cardiomyopathy-related 117 genes using HTS. Since functional studies contributed greatly to the determination of the precise pathogenicity of variants of unknown significance, we finally determined five pathogenic variants in five patients and seven likely pathogenic variants in six patients according to 2015 ACMG standards and guidelines.

This study provided some interesting findings. First, we identified two PTVs in EMD and three PTVs in LMNA as pathogenic. Also, we could confirm its pathogenicity based on functional properties of two PTVs in LMNA and two PTVs in EMD using in vivo zebrafish cardiac assay. This study represents the first report of the pathogenicity of PTVs in LMNA and EMD as determined by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-out in zebrafish. EMD and LMNA are known to be the disease-causing genes of EDMD with manifestation as high-grade AV block. The former is associated with X-linked recessive inheritance and the latter with autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and sporadic forms of EDMD. Both genes encode nuclear envelope proteins. EDMD is a genetically heterogeneous disorder characterized by early contractures, slowly progressive muscle wasting and weakness, and cardiomyopathy with conduction block. Some patients present with conduction disturbances or atrial cardiomyopathy even when skeletal myopathy is absent and are possible candidates for these mutations. In terms of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated zebrafish analysis, it has been used as a useful in vivo model to assay the pathogenicity of human variants in familial cardiovascular diseases.22,23 Zebrafish has the advantage of transparency, low cost, and the ability to manipulate their genome efficiently. Zebrafish can gain a prominent role as the models of thousands of candidate disease-associated genes and alleles.10 Namely, human pathogenesis of CCSD with LMNA or EMD mutation could be modelled in zebrafish.

Second, we could determine the pathogenicity of six rare ion channel variants with previously defined as ‘unknown significance’ by two functional analyses, electrophysiological and simulation studies. SCN5A P1824A and KCNH2 R269W were identified from the proband with SSS, AV block, and QT prolongation.21 Electrophysiological study demonstrated that both mutations showed loss-of-function. SCN5A encodes for the α-subunits of the voltage-gated Na+ channels (the Nav 1.5 channel), which is expressed in the conduction system and in the atrial regions surrounding the SAN and the AV node.24 A simulation study demonstrated that SCN5A P1824A may contribute to sinus node dysfunction, leading to SSS because of the higher vulnerability to electrotonic modulation. In contrast, the KCNH2 variant but not the SCN5A variant may contribute to QT prolongation and facilitate the formation of early afterdepolarizations during IKr inhibition, as demonstrated theoretically. Thus, the simulation study was useful in explaining the role of each variant in multiple disorders.

We determined four likely pathogenic variants in SCN10A in 4 of 23 (17%) CCSD patients. A cellular electrophysiological study demonstrated that three variants (G805S, R1263X, and M1373R) showed loss-of-function effects, and one variant (I1482V) showed gain-of-function effect. The voltage-gated sodium channel alpha subunit, Nav1.8 is encoded by SCN10A and is highly expressed in sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia. Several genome-wide association studies showed that SCN10A was associated with cardiac conduction. This is the first study to suggest that rare variants of SCN10A play an important role in the development of CCSD. A recent review showed how SCN10A variants promote dysfunctional conduction: the cardiomyocyte, enhancer, and neuronal hypotheses.25 CCSD caused by gain-of-function SCN10A rare variants may be explained through the neuronal hypothesis. The neuronal hypothesis stipulates that SCN10A indirectly exerts an effect on cardiac conduction through intracardiac neurons. SCN10A functions in cholinergic neurons to exert negative chronotropic and dromotropic effects on sinus and AV nodal tissues and modulates myocyte refractoriness. Gain-of-function SCN10A rare variants might cause vagus nerve stimulation and cardiac conduction disturbance. In contrast, the mechanism of causing CCSD by SCN10A loss-of-function rare variants is poorly understood. One possibility is that the enhancer hypothesis may be associated with the onset of CCSD by these variants. The enhancer hypothesis states that the cardiac enhancer located in Scn10a interacted with the promoter of Scn5a and was essential for Scn5a expression in murine cardiac tissue. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanism by which loss-of-function SCN10A rare variants modulate cardiac conduction and lead to development of bradycardia.

This study has several limitations. First, only 117 genes linked to arrhythmogenic diseases or cardiomyopathies were examined for rare variants associated with CCSD. Causative genes may be included in the remaining genes other than these 117 genes. Second, familial aggregation and segregation analysis were inadequate. Gene analyses for family members are needed to assign the PP2 category according to the 2015 ACMG guideline. Third, approximately 30% of the human genes do not have functional homologs in zebrafish. Fourth, one of the studied two LMNA PTVs and one of the studied two EMD PTVs were not conserved in zebrafish. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9 cannot modify such variants. However, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knock-out in zebrafish recapitulated the pathogenicity of PTVs in LMNA and EMD. In addition, functional properties of most missense variants in non-ion channel genes were not evaluated in this study. Well-established in vitro and in vivo functional studies are needed.

5. Conclusions

Integrated HTS targeting 117 arrhythmia and cardiomyopathy-related genes with functional studies identified 12 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 11 of 23 CCSD probands (48%): 5 probands harbouring 5 pathogenic variants in genes encoding nuclear envelope proteins; 5 probands harbouring at least one likely pathogenic variant in genes encoding ion channels; and 1 proband harbouring one likely pathogenic variant in MYH6. Notably, SCN10A may be one of the major development factors in CCSD.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the work described in the article and all take responsibility for it. K.H., Y.A., M.B., Y.K., I.K., C.M., S.T., and M.Y. designed the study. K.H., N.F., H.F., K.S., K.O., M.N., Y.K., T.T., B.K., K.O., Y.T., T.K., M.I., T.F., T.K., A.F., H.T., A.H., C.N., Y.S., T.T., Y.N., Y.T., H.O., Y.S., M.K., and M.T. conducted cardiovascular screening, examination, and clinical follow-up. K.H., R.T., Y.A., M.B., Y.K., E.B., P.S., M.B., Y.Z., A.K., Y.T., D.C., K.U., S.C., and T.K. performed experiments and collected the data. K.H., A.N., R.T., Y.A., and Y.K. analysed the data. K.H., A.N., R.T., Y.A., Y.K. and M.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Takako Obayashi, and Hitomi Oikawa for technical assistance.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This study was supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) [26460670 to K.H.] and Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research [15KK0302 to K.H.], Takeda Science Foundation (to K.H.), SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation. (to K.H.), Suzuken Memorial Foundation (to K.H.), and Japan Heart Foundation/Bayer Yakuhin Research Grant Abroad (to R.T.).

Translational perspective

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) may be helpful in determining the causes of cardiac conduction system disease (CCSD); however, the identification of pathogenic variants remains a challenge. We performed WES of 23 probands diagnosed with early-onset CCSD, and identified 12 pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants in 11 of these probands (48%) according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) standards and guidelines. In this context, functional analyses of a cellular electrophysiological study and in vivo zebrafish cardiac assay might be useful for determining the pathogenicity of rare variants, and SCN10A may be one of the major development factors in CCSD.

References

- 1.Beinart R, Ruskin J, Milan D. The genetics of conduction disease. Heart Fail Clin 2010;6:201–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolf CM, Berul CI. Inherited conduction system abnormalities–one group of diseases, many genes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006;17:446–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa T, Tsuji Y, Makita N. Inherited bradyarrhythmia: a diverse genetic background. J Arrhythm 2016;32:352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celestino-Soper PB, Doytchinova A, Steiner HA, Uradu A, Lynnes TC, Groh WJ, Miller JM, Lin H, Gao H, Wang Z, Liu Y, Chen PS, Vatta M. Evaluation of the genetic basis of familial aggregation of pacemaker implantation by a large next generation sequencing panel. PLoS One 2015;10:e0143588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ho CY, Charron P, Richard P, Girolami F, Van Spaendonck-Zwarts KY, Pinto Y. Genetic advances in sarcomeric cardiomyopathies: state of the art. Cardiovasc Res 2015;105:397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; on behalf of the ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med 2015;17:405–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayashi K, Konno T, Tada H, Tani S, Liu L, Fujino N, Nohara A, Hodatsu A, Tsuda T, Tanaka Y, Kawashiri MA, Ino H, Makita N, Yamagishi M. Functional characterization of rare variants implicated in susceptibility to lone atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:1095–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milan DJ, Macrae CA. Zebrafish genetic models for arrhythmia. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2008;98:301–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sabeh MK, Kekhia H, Macrae CA. Optical mapping in the developing zebrafish heart. Pediatr Cardiol 2012;33:916–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis EE, Frangakis S, Katsanis N. Interpreting human genetic variation with in vivo zebrafish assays. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1842:1960–1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gagnon JA, Valen E, Thyme SB, Huang P, Ahkmetova L, Pauli A, Montague TG, Zimmerman S, Richter C, Schier AF. Efficient mutagenesis by Cas9 protein-mediated oligonucleotide insertion and large-scale assessment of single-guide RNAs. PLoS One 2014;9:e98186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J, Zhou Y, Qi X, Chen J, Chen W, Qiu G, Wu Z, Wu N. CRISPR/Cas9 in zebrafish: an efficient combination for human genetic diseases modeling. Hum Genet 2017;136:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics 2010;26:2069–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panakova D, Werdich AA, Macrae CA. Wnt11 patterns a myocardial electrical gradient through regulation of the L-type Ca(2+) channel. Nature 2010;466:874–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker JR, Robinson TY, Sachidanandan C, Kelly AE, Coy S, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. In vivo natriuretic peptide reporter assay identifies chemical modifiers of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy signalling. Cardiovasc Res 2012;93:463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu RS, Lam II, Clay H, Duong DN, Deo RC, Coughlin SR. A rapid method for directed gene knockout for screening in G0 zebrafish. Dev Cell 2018;46:112–125.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishikawa T, Jou CJ, Nogami A, Kowase S, Arrington CB, Barnett SM, Harrell DT, Arimura T, Tsuji Y, Kimura A, Makita N. Novel mutation in the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene is associated with sick sinus syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:400–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurata Y, Hisatome I, Matsuda H, Shibamoto T. Dynamical mechanisms of pacemaker generation in IK1-downregulated human ventricular myocytes: insights from bifurcation analyses of a mathematical model. Biophys J 2005;89:2865–2887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurata Y, Matsuda H, Hisatome I, Shibamoto T. Regional difference in dynamical property of sinoatrial node pacemaking: role of na+ channel current. Biophys J 2008;95:951–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakata K, Shimizu M, Ino H, Yamaguchi M, Terai H, Fujino N, Hayashi K, Kaneda T, Inoue M, Oda Y, Fujita T, Kaku B, Kanaya H, Mabuchi H. High incidence of sudden cardiac death with conduction disturbances and atrial cardiomyopathy caused by a nonsense mutation in the STA gene. Circulation 2005;111:3352–3358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh H, Shimizu W, Hayashi K, Yamagata K, Sakaguchi T, Ohno S, Makiyama T, Akao M, Ai T, Noda T, Miyazaki A, Miyamoto Y, Yamagishi M, Kamakura S, Horie M. Long QT syndrome with compound mutations is associated with a more severe phenotype: a Japanese multicenter study. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:1411–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodatsu A, Konno T, Hayashi K, Funada A, Fujita T, Nagata Y, Fujino N, Kawashiri MA, Yamagishi M. Compound heterozygosity deteriorates phenotypes of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with founder MYBPC3 mutation: evidence from patients and zebrafish models. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2014;307:H1594–H1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jou CJ, Barnett SM, Bian JT, Weng HC, Sheng X, Tristani-Firouzi M. An in vivo cardiac assay to determine the functional consequences of putative long QT syndrome mutations. Circ Res 2013;112:826–830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monfredi O, Dobrzynski H, Mondal T, Boyett MR, Morris GM. The anatomy and physiology of the sinoatrial node–a contemporary review. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2010;33:1392–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park DS, Fishman GI. Nav-igating through a complex landscape: SCN10A and cardiac conduction. J Clin Invest 2014;124:1460–1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.