Abstract

This study uses Medicare data to assess physician practice interruptions during the 2019-2020 period of the COVID-19 pandemic and provides preliminary evidence on whether those interruptions suggest early retirements or exit from medical practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the practice of medicine across the US. The majority of physicians—especially those practicing in outpatient settings—saw visit volume fall in March of 2020, only returning to prepandemic levels in September.1

In response, many physicians reported practice interruptions, with some expressing intent to retire or close their practice.1,2 We analyzed Medicare data to assess physician practice interruptions and provide preliminary evidence on whether those interruptions suggest early retirements or exit from medical practice.

Methods

We analyzed Medicare physician claims for 100% of fee-for-service beneficiaries from January 1, 2019, to December 30, 2020, and Doximity data on physician age. We counted the monthly number of claims billed by each physician in 2019 and 2020. We defined a practice interruption as a month in which a physician who had previously billed Medicare billed zero Medicare claims. For example, if a physician who had previously billed Medicare did not bill Medicare in April of 2020, we considered April 2020 a practice interruption. We defined interruptions with return as those for which the physician resumed billing Medicare within 6 months of the last billing month and interruptions without return as those for which the physician did not resume billing Medicare within 6 months. We excluded physicians in training, pediatricians, and physicians who billed fewer than 50 Medicare claims during 2018, as these groups may bill Medicare intermittently for reasons other than practice interruptions.

To compute monthly practice interruption rates in 2019 vs 2020, we regressed our 3 practice interruption outcomes on calendar month interacted with an indicator for 2020. We then tested for differential changes by physician characteristics (age, sex, specialty, practice size, practice location) in the month of peak practice interruptions (April) from 2019 to 2020. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 17 (StataCorp), with statistical significance defined as 2-sided P < .05. The study was deemed not to involve human participants by the University of Minnesota institutional review board.

Results

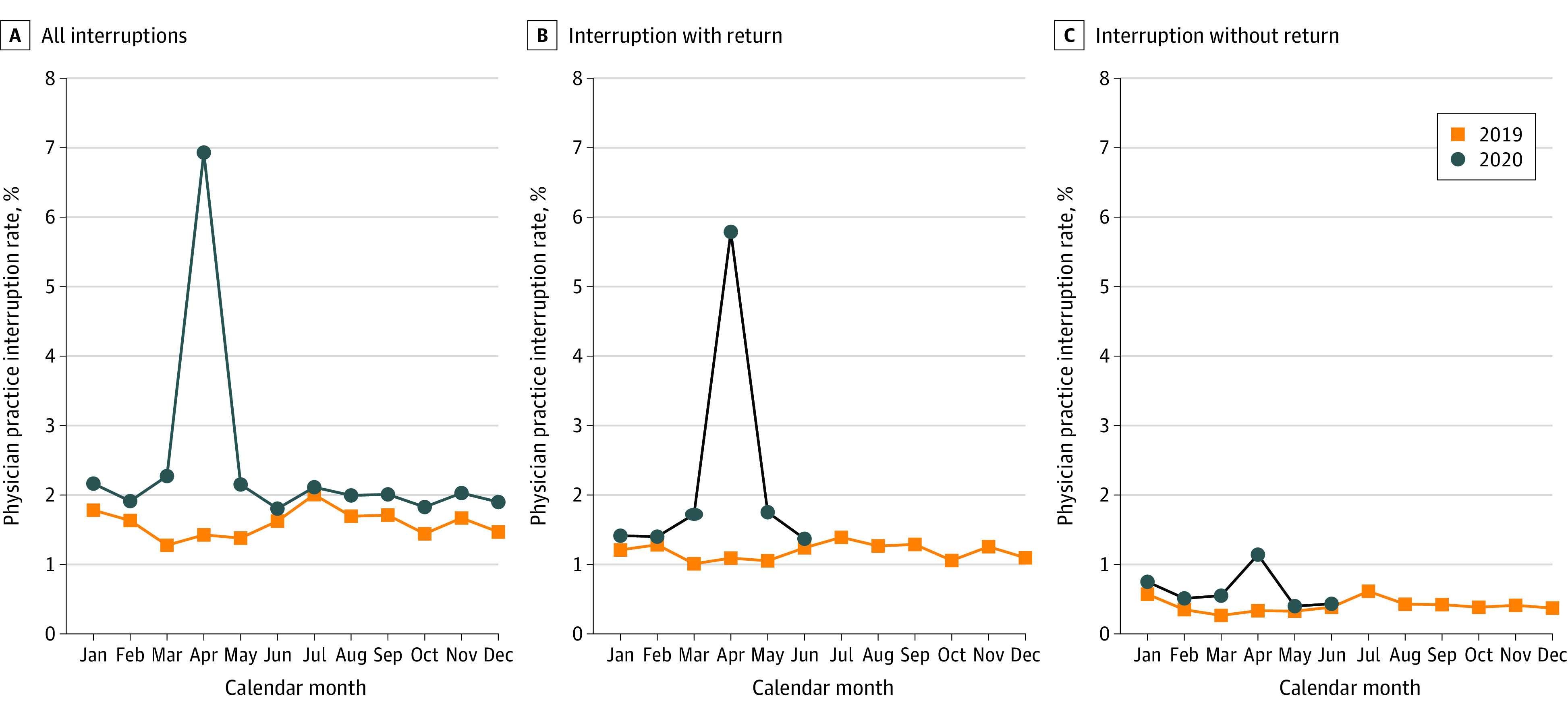

Our sample included 547 849 physicians billing Medicare. Practice interruption rates were similar before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, except for a spike in April 2020, when 34 653 (6.93% [95% CI, 6.89%-6.97%]) physicians billing Medicare experienced a practice interruption (Figure), relative to 1.43% (95% CI, 1.39%-1.46%) in 2019 (P < .001). Overall, 1.14% (95% CI, 1.12%-1.16%) of physicians stopped practice in April 2020 and did not return, compared with 0.33% (95% CI, 0.32%-0.35%) in 2019 (P < .001).

Figure. Monthly Physician Practice Interruption Rate, Overall and by Return Status.

Month of interruption was defined as the first month during which a physician billed zero claims. Source: Authors’ analysis of Medicare claims data (2019-2020) and Doximity data.

Practice interruption rates varied by physician characteristic (Table). The increase between April 2019 and April 2020 in interruption rates and interruption-without-return rates was larger for older physicians (≥55 years) than for younger physicians (change in interruption rates: 7.23% [95% CI, 7.10%-7.35%] vs 3.90% [95% CI, 3.81%-3.99%], P < .001; change in interruption-without-return rates: 1.30% [95% CI, 1.24%-1.36%] vs 0.34% [95% CI, 0.31%-0.37%], P < .001). Female physicians, specialists, physicians in smaller practices, those not in a health professional shortage area, and those practicing in a metropolitan area experienced greater increases in practice interruption rates in April 2020 vs April 2019, but those groups typically had higher rates of return, so the overall change in practice interruptions without return were similar across characteristics other than age.

Table. Change in Physician Practice Interruption Rate Between April 2019 vs April 2020, by Physician Characteristics.

| Rate, % (95% CI)a | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice interruption | Practice interruption with return | Practice interruption without return | ||||||||||

| April 2019 | April 2020 | Change | P value | April 2019 | April 2020 | Change | P value | April 2019 | April 2020 | Change | P value | |

| Overall | 1.43 (1.39-1.46) |

6.93 (6.89-6.97) |

5.50 (5.43-5.58) |

1.09 (1.06-1.12) |

5.79 (5.72-5.85) |

4.70 (4.63-4.77) |

0.33 (0.32-0.35) |

1.14 (1.12-1.16) |

0.81 (0.77-0.84) |

|||

| Physician age, y | ||||||||||||

| <55 | 1.19 (1.15-1.23) |

5.09 (5.00-5.17) |

3.90 (3.81-3.99) |

<.001 | 1.02 (0.98-1.05) |

4.58 (4.50-4.66) |

3.56 (3.47-3.65) |

<.001 | 0.17 (0.16-0.19) |

0.51 (0.48-0.54) |

0.34 (0.31-0.37) |

<.001 |

| ≥55 | 1.70 (1.65-1.75) |

8.93 (8.81-9.04) |

7.23 (7.10-7.35) |

1.12 (1.14-1.22) |

7.10 (7.00-7.21) |

5.92 (5.81-6.03) |

0.52 (0.49-0.55) |

1.82 (1.77-1.88) |

1.30 (1.24-1.36) |

|||

| Physician sex | ||||||||||||

| Men | 1.25 (1.21-1.28) |

6.34 (6.26-6.42) |

5.09 (5.01-5.18) |

<.001 | 0.92 (0.89-0.95) |

5.20 (5.13-5.27) |

4.28 (4.20-4.36) |

<.001 | 0.33 (0.31-0.34) |

1.14 (1.11-1.18) |

0.82 (0.78-0.85) |

.46 |

| Women | 1.84 (1.78-1.91) |

8.32 (8.18-8.46) |

6.47 (6.32-6.63) |

1.49 (1.43-1.55) |

7.17 (7.04-7.30) |

5.68 (5.54-5.83) |

0.35 (0.33-0.38) |

1.14 (1.09-1.20) |

0.79 (0.73-0.85) |

|||

| Physician specialty | ||||||||||||

| Specialist | 1.36 (1.32-1.39) |

7.86 (7.77-7.95) |

6.51 (6.41-6.60) |

<.001 | 1.05 (1.02-1.08) |

6.70 (6.62-6.79) |

5.65 (5.57-5.74) |

<.001 | 0.31 (0.29-0.32) |

1.16 (1.12-1.20) |

0.85 (0.81-0.89) |

<.001 |

| Primary care | 1.58 (1.52-1.64) |

4.86 (4.76-4.97) |

3.28 (3.16-3.40) |

1.18 (1.13-1.24) |

3.76 (3.67-3.85) |

2.58 (2.49-2.68) |

0.40 (0.37-0.43) |

1.10 (1.05-1.15) |

0.71 (0.65-0.76) |

|||

| Practice size, No. of physicians | ||||||||||||

| 1-9 | 1.22 (1.17-1.28) |

7.57 (7.43-7.70) |

6.34 (6.20-6.48) |

<.001 | 0.85 (0.80-0.89) |

6.63 (6.22-6.46) |

5.49 (5.37-5.62) |

<.001 | 0.38 (0.35-0.41) |

1.23 (1.17-1.28) |

0.85 (0.79-0.91) |

.10 |

| ≥10 | 1.52 (1.48-1.56) |

6.65 (6.57-6.73) |

5.13 (5.04-5.22) |

1.20 (1.17-1.24) |

5.54 (5.47-5.62) |

4.34 (4.26-4.43) |

0.31 (0.30-0.33) |

1.10 (1.07-1.14) |

0.79 (0.75-0.83) |

|||

| Practice location | ||||||||||||

| HPSA | 1.53 (1.49-1.58) |

6.66 (6.56-6.75) |

5.12 (5.02-5.22) |

<.001 | 1.16 (1.12-1.20) |

5.52 (5.44-5.60) |

4.36 (4.27-4.45) |

<.001 | 0.37 (0.35-0.39) |

1.13 (1.10-1.17) |

0.77 (0.72-0.81) |

.006 |

| Not HPSA | 1.29 (1.24-1.34) |

7.28 (7.17-7.39) |

5.99 (5.88-6.11) |

1.00 (0.96-1.04) |

6.13 (6.03-6.23) |

5.13 (5.03-5.24) |

0.29 (0.27-0.31) |

1.15 (1.11-1.19) |

0.86 (0.81-0.91) |

|||

| Practice urbanicity | ||||||||||||

| Metropolitan | 1.38 (1.35-1.41) |

7.03 (6.95-7.10) |

5.65 (5.57-5.73) |

<.001 | 1.06 (1.03-1.09) |

5.89 (5.82-5.96) |

4.82 (4.75-4.90) |

<.001 | 0.32 (0.30-0.33) |

1.14 (1.11-1.17) |

0.82 (0.79-0.86) |

.003 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 1.84 (1.72-1.95) |

6.06 (5.85-6.27) |

4.22 (3.99-4.45) |

1.34 (1.24-1.43) |

4.90 (4.71-5.09) |

3.56 (3.18-3.78) |

0.50 (0.44-0.55) |

1.16 (1.07-1.25) |

0.66 (0.55-0.77) |

|||

Abbreviation: HPSA, health professional shortage area.

Within an outcome (ie, interruption rate and interruption-without-return rate), each physician characteristic represents its own regression. Differential changes in interruption rates by physician characteristic were tested for by regressing interruption outcomes on a variable equal to 1 in the pandemic period (2020), the physician characteristic of interest (eg, physician age category), and an interaction between pandemic period and the characteristic of interest. Source: Authors’ analysis of Medicare claims data (2019-2020) and Doximity data.

Discussion

Practice interruptions in the treatment of Medicare patients during 2020 exceeded those in 2019 and were concentrated in April—coinciding with the nadir of outpatient clinical volume due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most practice interruptions were temporary, though not all. The pandemic appears to have impeded return to practice more for older physicians than for younger physicians, consistent with anecdotal reports and survey findings regarding intent to close practices, retire, or otherwise transition away from clinical medicine.2,3

This work has several limitations. First, the analysis was limited to Medicare claims, which likely reflect only part of physicians’ clinical activities. Second, it is impossible to definitively attribute practice interruptions without return to retirement, or practice interruptions with return to furloughs. Third, this measure of practice interruption likely misses meaningful interruptions that lasted for less than a month or did not involve complete cessation in treating Medicare patients. Further study is needed to understand the long-term effects of practice interruptions on the physician workforce and access to care.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Associate Editor.

References

- 1.Mehrotra A, Chernew ME, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D, Schneider EC. The impact of COVID-19 on outpatient visits in 2020: visits remained stable, despite a late surge in cases. Commonwealth Fund. Published February 22, 2021. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2021/feb/impact-covid-19-outpatient-visits-2020-visits-stable-despite-late-surge

- 2.2020 Survey of America’s physicians: COVID-19 impact edition. The Physicians Foundation. Accessed July 19, 2021. https://physiciansfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/2020-Survey-of-Americas-Physicians_Exec-Summary.pdf

- 3.Primary Care Collaborative . Quick COVID-19 primary care survey. Larry A. Green Center. Accessed July 29, 2021. https://www.green-center.org/covid-survey