Abstract

This manuscript details the strategy employed for categorising food items based on their processing levels into the four NOVA groups. Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires (FFQs) from the Nurses’ Health Studies (NHS) I and II, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and the Growing Up Today Studies (GUTS) I and II cohorts were used. The four-stage approach included: (i) the creation of a complete food list from the FFQs; (ii) assignment of food items to a NOVA group by three researchers; (iii) checking for consensus in categorisation and shortlisting discordant food items; (iv) discussions with experts and use of additional resources (research dieticians, cohort-specific documents, online grocery store scans) to guide the final categorisation of the short-listed items. At stage 1, 205 and 315 food items were compiled from the NHS and HPFS, and the GUTS FFQs, respectively. Over 70 % of food items from all cohorts were assigned to a NOVA group after stage 2. The remainder were shortlisted for further discussion (stage 3). After two rounds of reviews at stage 4, 95⋅6 % of food items (NHS + HPFS) and 90⋅7 % items (GUTS) were categorised. The remaining products were assigned to a non-ultra-processed food group (primary categorisation) and flagged for sensitivity analyses at which point they would be categorised as ultra-processed. Of all items in the food lists, 36⋅1 % in the NHS and HPFS cohorts and 43⋅5 % in the GUTS cohorts were identified as ultra-processed. Future work is needed to validate this approach. Documentation and discussions of alternative approaches for categorisation are encouraged.

Key words: Cohort studies, Diet categorisation, Expert discussion, Food frequency questionnaires, Nova groups, Ultra-processed foods

Abbreviations: FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; GUTS, Growing Up Today Study; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study

Introduction

Ultra-processed foods are ready-to-eat/heat industrial formulations of food substances that have been derived from whole foods, and that typically contain added flavours, colours and other cosmetic additives(1). They are one of the four groups that make up the NOVA classification – a system that classifies food based on the extent and purpose of the industrial processing they undergo and accounts for the physical, biological and chemical methods used in their manufacture, including the use of additives(1). Recently, observational studies have provided the first evidence for the health harms associated with the intake of ultra-processed foods(2–4).

For the most part, the large-scale prospective cohort studies that have assessed the associations between ultra-processed foods and disease outcomes have used a self-administered food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) for repeated dietary assessment(5–9). However, the food lists on the basis of which dietary information is collected are designed to have a limited number of pre-defined items which represent the primary sources of energy and nutrients in the population under study(10). As such, FFQs are unable to cover the full spectrum of foods consumed, including ultra-processed foods. Additionally, all supporting information that would be useful in identifying the ultra-processed products from the food lists like cooking methods used, food combinations and ingredients, place of food consumption and brand names of packaged products are usually not captured by FFQs.

Capturing ultra-processed food intake may not have been the explicit goal of epidemiologic studies at the time of their inception. This would have implications for the development of their dietary assessment instruments. Even 24-h diet recalls or diet records that describe with some detail the foods eaten and their method of preparation, may therefore still lack the granularity needed to accurately identify all ultra-processed products. This may result in some ambiguity in the identification of the grade of processing of a subset of food items from different dietary assessment methods and not limited to FFQs, creating an opportunity for discussion of the possible approaches for improving the identification and estimation of ultra-processed foods in epidemiologic studies.

There is limited documentation of the approaches used in the classification of food intake into the four NOVA categories or in the identification of ultra-processed foods. To our knowledge, no previous study has explicitly presented the process used in the identification of ultra-processed foods from FFQs in sufficient detail to aid replication. As a result, the challenges encountered in the process of manual classification of the diet, or the decisions made to address them have not been systematically documented. Potential sources of misclassification may also be overlooked. This gap in the evidence base hinders progress in streamlining the application of the NOVA classification to dietary intake, in identifying ultra-processed foods, in estimating their contribution to the diet, and in improving dietary assessment methods to better capture food processing levels.

The purpose of this manuscript is to detail the approach for categorising food items captured by semi-quantitative FFQs of the Nurses’ Health Studies I and II, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and the Growing Up Today Study I and II, into the four NOVA groups and to identify ultra-processed foods. Collectively, these cohorts have made important contributions to the evidence base informing dietary guidelines and nutrition policy(11) and their semi-quantitative FFQs have served as a template for FFQs used in epidemiologic studies, globally(12–14). Presenting the strategy adopted in these cohorts will inform the categorisation of the diet in other studies that use similar assessment methods. While no validation work is presented, the broader goal of this manuscript is to encourage discussions on approaches to categorise dietary data into the NOVA groups and to inform the evolution of dietary assessment methods.

Methods

Cohort details

The first cohort of the Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) in 1976 enrolled 121 701 female registered nurses, aged 30 and 55 years(15). In 1986, 51 529 male health professionals, aged 40 and 75 years, comprised the first cohort of the HPFS(16), and in 1989, the first cohort of the NHS-II began with 116 686 female registered nurses, aged 25–42 years. Since then, participants in all three adult cohorts complete a biennial follow-up questionnaire on their medical history, lifestyle factors and occurrence of chronic diseases.

In 1996, the children of the NHS-II study participants were recruited into a study of their own – the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS)(17). At inception, GUTS included 16 882 girls and boys aged between 9 and 14 years. In 2004, the study expanded to include a second cohort of 10 920 children between the ages of 10 and 17 years – the GUTS-II cohort. The two youth cohorts were followed biannually until 2013 when they were merged into one cohort.

Assessment of food intake

Dietary data from all waves of both the adult and the youth cohorts were collected using a self-administered, semi-quantitative FFQ(15,17). The first FFQ used in 1984 had 116 items and information on the usual intake of food and beverages from the NHS participants. This FFQ was expanded in 1986 to ~130 foods and sent every 4 years to track the diets of participants in both the NHS and the HPFS cohorts (NHS-II, since 1991). The GUTS FFQ included ~150 food items and was modified from the validated adult FFQ to the cognitive level and dietary knowledge of adolescents. It specifically included snack foods consumed by a younger population and food eaten away from home(17). The FFQs continue to be updated to capture more detailed information on cooking methods and relevant food items(15).

All FFQs ask participants how often, on average, they consumed a given reference portion of a food item over the course of the previous year. A total of nine response categories capture usual intake, ranging from ‘never or less than once/month’ to ‘≥6 times/day.’ The reproducibility and validity of these FFQs have been extensively evaluated(16–19). Nutrient intakes are estimated on the basis of a daily weight assigned to each food item based on its frequency of consumption(19). A database of the nutrient content of FFQ food items maintained by study dietitians, the Harvard nutrient database, began in 1984(15). It has been updated every 4 years to reflect changes to nutrient composition (e.g., changes in trans fat content). It also includes new food items and the most recent information on food components based on the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Nutrient Database for Standard Reference and the Food and Nutrients Database for Dietary Studies.

Classification of food items into the NOVA groups

The NOVA classification considers the extent and purpose of processing of the food item and includes four groups – (1) unprocessed or minimally processed food, (2) processed culinary ingredients, (3) processed foods and (4) ultra-processed foods. The first three NOVA groups include food products that have undergone processing methods like grinding, roasting, pasteurisation, freezing, vacuum packaging or non-alcoholic fermentation (minimally processed foods), centrifuging, refining or extracting (processed culinary ingredients) or preservation methods such as canning and bottling (processed foods)(1). The category of ultra-processed foods includes food items that normally undergo more intensive industrial processing like hydrolysis, or hydrogenation, extrusion, moulding and pre-frying.

A four-stage process was undertaken to identify the ultra-processed foods from both the adult and the youth FFQs. First, all food items in the FFQs across different waves of data collection were complied. Food items that were nearly identical between FFQs but were presented with minor differences were captured as separate items (e.g., ‘Cold breakfast cereal (1 bowl)’ and ‘Cold breakfast cereal (1 serving)’). This was done to make sure that no food item was overlooked. FFQs from every 4 years of the NHS-I (1986–2010), the NHS-II (1991–2015), the HPFS (1986–2014), from 1996, 1998, 2001 for GUTS-I and from 2004, 2006, 2008, 2011 for GUTS-II were used.

Second, three researchers working independently assigned foods in the adult (N.K, S.R, E.M) and the youth (N.K, M.D, E.M) cohorts to one of the four NOVA groups based on their grade of processing – unprocessed/minimally processed foods (G1), processed culinary ingredients (G2), processed foods (G3) and ultra-processed foods (G4). Food assignment was guided by the definition, examples and supplementary material published by the proponents of the NOVA classification(1). Categorisation was an iterative process requiring the review of the original FFQs used at each wave of data collection to contextualise food items within the larger food lists. Food preparations made from multiple ingredients or different food items that were presented jointly in the FFQ were not disaggregated into their different components. Additionally, the nutrient profile of food items, their actual amounts consumed by the study participants or participant demographics were not considered at any point in the categorisation process. Instead, the original food item as it was listed in the FFQ was categorised in its entirety.

At the third stage, categorisation between researchers was triangulated. Food items for which there was consensus in the categorisation among all researchers were assigned to their NOVA group. A food item was flagged for further scrutiny and shortlisted in case a researcher was unable to assign it to a NOVA group or in cases of disagreement in categorisation by any two researchers.

At stage four, an expert panel comprising of three senior nutrition epidemiologists (F.F.Z; T.F; Q.S) with substantial experience working with the dietary intake in these cohorts, was convened to review and discuss the categorisation of the short-listed products. All discussions were additionally informed by the following resources:

Consultations with the research dietitians. The team of research dietitians, led by L.S, was responsible for overseeing the collection of dietary data and for ascertaining the nutrient composition of food items across all Harvard cohorts. They shared their insights obtained from gathering supplementary data, tracking new and reformulated products available in the supermarket, and conducting multiple pilot studies with cohort participants.

Cohort-specific documents. These resources provided more insight into the extent of processing of certain FFQ food items by highlighting information on the specific ingredients used in recipes and food preparations, the proportion by weight of individual ingredients to the final recipe or a more detailed description of food items (whether the food was canned or salted or boiled, the brand name of certain packaged foods, etc.).

Supermarket scans. The ingredient lists of the first five brands of specific products that were displayed on the Walmart website in 2019 and 2020 were scrutinised. They served as a proxy for establishing the level of processing for a small proportion of food items for which limited information was available from the resources listed above.

The process of categorisation of food items at this stage was also iterative and at the end of stage four, all products were categorised into one of the four NOVA groups. The compilation and categorisation of food items from both the adult and the youth cohorts was done in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft 365, academic license).

Results

At stage one, a total of 205 unique foods from all FFQ food lists of the NHS, NHS-II and HPFS cohorts and 315 foods in the GUTS cohort were identified and compiled. These included individual food items (‘Butter’; ‘Coffee’; ‘Prunes’; ‘White rice’) and food items that were presented jointly (examples mentioned later). Ninety-seven percent of the food items in the adult cohorts (n 199 of 205) and 93 % in the GUTS cohort (n 293 of 315) were asked in this manner. Of the multiple food items presented jointly, a large majority of them had similar grades of processing. Examples include ‘Tangerines, clementines, mandarin oranges’, ‘English muffins, bagels, rolls’, ’Shrimp, lobster, or scallops as a main dish’, ‘Beef, pork hotdog’. Some multiple items included specific examples of products or brand names like ‘Hot breakfast cereal, like oatmeal, grits’, ‘Non-fat iced coffee dairy drinks, like Coffee Coolatta, Frappuccino’, ‘Cereal/Granola bar like Nature Valley, Quaker, or Special K’. However, about 3 % (n 6 of 205) of the grouped food items in the NHS and the HPFS cohorts and 7 % (n 22 of 315) in the youth cohort included a combination of food items with potentially different grades of processing. For instance, in ‘Jams, jellies, preserves, honey’, honey would be differently processed from the other condiments. Similarly, for ‘Pie, home-baked or ready-made’, home-made pies would be differently processed to ready-made pies. Other examples of jointly presented food items with different grades of processing include ‘Onion rings, cooked onions, or soup’, ‘Tofu, soyburgers, miso, edamame, or other soy dish’.

Food items were assigned to a NOVA group by three researchers in stage two. At this stage, other food items included in the FFQs specific to each cohort were also used to inform categorisation. For instance, the classification of ‘Cold breakfast cereal’ into G4 was informed by contextualising it relative to another item on the FFQ, ‘Cooked oatmeal, oatbran’ (G1), for which information was also collected in the same year. Cold cereals were assumed to be packaged and ready-to-eat, and therefore more likely to be ultra-processed, especially as another item was capturing minimally processed oats. For food preparations containing more than one ingredient, the item description helped ascertain the level of processing of certain foods and their categorisation. Examples include ‘Home-made soup without bouillon cube’ (G1), ‘Pie, home-baked’ (G1). The descriptor ‘home-made’ indicated that the food item was likely to not be ultra-processed (confirmed by the phrase ‘without bouillon cube’) and hence it was categorised as G1.

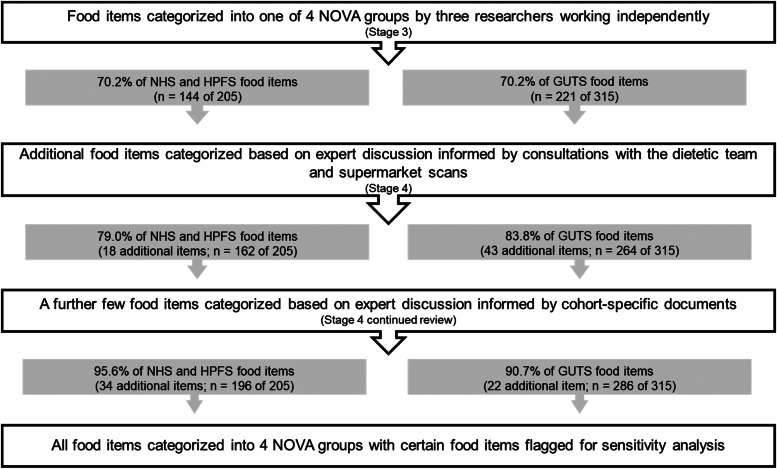

NOVA group assignments were triangulated in stage 3. There was consensus among all study researchers in the categorisation of 144 of the 205 food items (70⋅2 %) in the adult cohorts and 221 of the 315 food items (70⋅2 %) in the youth cohort (see Fig. 1). For example: ‘Rice’, ‘Celery’, ‘Raw carrot’ were assigned to G1; ‘Butter’, ‘Canola oil’ to G2; ‘Canned tuna’, ‘Olives’ to G3; and ‘Jello’, ‘Ready-made soup from a can’ to G4. The descriptor ‘ready-made’ indicated that the food item was likely to be ultra-processed. There was some uncertainty between researchers in the categorisation of 61 of the 205 food items in the adult cohorts (29⋅8 %) and 94 of 315 food items in the youth cohort (29⋅8 %). These included all the grouped foods with a combination of products with potentially different grades of processing mentioned earlier (e.g., ‘Jams, jellies, preserves, honey’).

Fig. 1.

The process of NOVA categorisation of food items captured by semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires of the Nurses’ Health Studies I and II (NHS), the Health Professionals follow-up study (HPFS) and the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

The food items with uncertain categorisation (n 61 in NHS/HPFS; n 94 in GUTS) were further reviewed by the expert panel in stage four. Consultations with the dietetic team followed by supermarket scans and team discussions informed the categorisation of eighteen of the sixty-one food items in the adult cohorts and forty-three of the ninety-four food items in the GUTS cohorts. These were subsequently assigned to a NOVA group. At this juncture, 79 % and 83⋅8 % of the food items from the adult and youth cohorts respectively, had been categorised. Sixteen of the eighteen foods in the NHS and HPFS cohorts and twenty-five of the forty-three in the GUTS cohort were identified as having a low potential for contributing to the ultra-processed proportion of the diet – in all possible scenarios of categorisation, these products would have been assigned to either the minimally processed or the processed groups. Examples include: ‘Apricots’, ‘Prunes’, ‘Walnuts’ (G1); ‘Sauerkraut’, ‘Cottage or ricotta cheese’, ‘Mustard’ (G3). The processing category for ‘Mustard’ (G3) was informed by the supermarket scans. Food products (n 2 in NHS/HPFS; n 18 in GUTS) that were classified as ultra-processed at this stage included ‘Salad dressing’, ‘Soy or Worcestershire sauce’, ‘Tofu, soyburgers, other meat substitutes’, ‘Hawaiian Punch, lemonade, Koolaid or other non-carbonated fruit drinks’ and food preparations like ‘Salami, bologna, or other deli meat sandwich’, ‘Bagels, English muffins, or rolls including breakfast sandwiches’, ‘Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): Beef, pork, or lamb’.

In continued review at stage four, cohort-specific documents along with further input from the dietetic team were used to determine the level of processing for thirty-four additional food items in the adult cohorts and twenty-two additional food items in the GUTS cohort. These products were subsequently assigned to a NOVA category, resulting in the categorisation of 95⋅6 % (adult cohorts) and 90⋅7 % (youth cohort) of all food items. For instance, cohort-specific documents described ‘Applesauce’ as ‘applesauce, canned, sweetened, and without salt’ and ‘Canned peaches’ as ‘peaches, canned, heavy syrup; peaches, canned in juice’ which helped with their assignment into G4. The documents also provided a detailed description for items like ‘French fried potatoes’ (frozen French fries prepared, McDonald's French fries; Burger King French fries). Additional examples of food items that were assigned to the ultra-processed food group at this stage include food preparations like ‘Brownies’, ‘French fried potatoes’, ‘Pizza’, ‘Chowder or cream soup’, ‘Dairy coffee drink’, ‘Danish, sweet rolls, pastry’.

There was not enough evidence in the resource documents to support the classification of the nine remaining food items in the NHS and HPFS cohorts and twenty-nine remaining food items in the GUTS cohort. After discussion with the expert panel, a conservative approach to their categorisation was adopted by assigning these products to a non-ultra-processed NOVA group as their primary categorisation. Examples of the food items that were categorised in this manner include: ‘Popcorn’ (G3); ‘Soya milk’ (G1); ‘Chicken or turkey sandwich’ (G1); ‘Pancakes or waffles’ (G1); ‘Pie, home-baked or ready-made’ (G1). In the future analysis that assesses associations between ultra-processed food consumption and disease outcomes, these products would be recommended for further sensitivity analysis at which point they would be assigned to the ultra-processed group to check for robustness of the associations seen. A flow chart of the categorisation process and cumulative categorised percent is presented in Fig. 1.

A total of 74 of the 205 food items (36⋅1 %) from the NHS and HPFS FFQ food lists and 137 of the 315 food items (43⋅5 %) from the GUTS FFQ food lists were assigned to the ultra-processed food category at the end of the categorisation process at stage 4. Of these, 85⋅1 % of the food items in the adult cohorts (63 of 74) and 72⋅9 % in the youth cohort (100 of 137) were categorised at the end of stage 2, even before discussion with experts (e.g., ‘Regular carbonated beverage with caffeine & sugar’, ‘White bread, pita bread, or toast’, ‘Popsicles’). Over 86 % of the ultra-processed foods from all cohorts were categorised after the first round of reviews with experts. Fig. 2 presents the contribution of the four NOVA groups to the FFQ food lists compiled from all waves of the cohorts.

Fig. 2.

The percentage contribution of the four NOVA groups to the food items compiled from all waves of the Nurses’ Health Studies, the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (a), and the Growing Up Today Studies (b).

Tables 1 and 2 capture the short-listed food items scrutinised at stage four.

Table 1.

Foods items that required discussion and further review in the Nurses’ Health Studies I and II, and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study

| All foods with discordant categorisation n 61 of 205 | Foods requiring additional review n 43 | Foods in sensitivity analysis n 9 |

|---|---|---|

| Apple juice cider | Applesauce | Beef, pork, lamb sandwich |

| Applesauce | Beans or lentils | Chicken or turkey sandwich |

| Apricots | Beef, pork, lamb sandwich | Cream |

| Beans or lentils | Brownies | Pancakes or waffles |

| Beef, pork, lamb sandwich | Cake, home-baked | Pie, home-baked or ready-made |

| Brownies | Canned peaches | Popcorn: regular |

| Cake, home-baked | Canned pear | Potato chips or corn chips |

| Canned peaches | Chicken or turkey sandwich | Soya milk |

| Canned pear | Chowder or cream soup | Tomato sauce |

| Carrots | Cookies, home-baked | |

| Chicken or turkey sandwich | Cottage ricotta cheese | |

| Chowder or cream soup | Cream | |

| Cooked carrots | Crispbreads | |

| Cookies, home-baked | Dairy coffee drink | |

| Maize | French fried potatoes | |

| Cottage ricotta cheese | Grapefruit juice | |

| Cream | Grapefruit or grapefruit juice | |

| Crispbreads | Grapefruit, grapefruit juice | |

| Dairy coffee drink | Hamburger, lean or extra lean | |

| French fried potatoes | Home-made sweet roll, coffee cake | |

| Grapefruit juice | Jams, jellies, preserves, honey | |

| Grapefruit or grapefruit juice | Orange juice | |

| Grapefruit, grapefruit juice | Orange juice with calcium | |

| Hamburger, lean or extra lean | Other canned fruit | |

| Herbal or decaf tea | Other cheese | |

| Home-made sweetroll, coffee cake | Other cooked breakfast cereal | |

| Jams, jellies, preserves, honey | Other fruit juices | |

| Mustard | Pancakes or waffles | |

| Orange juice | Pasta | |

| Orange juice with calcium | Peanut butter | |

| Other canned fruit | Pie, home-baked or ready-made | |

| Other cheese | Pizza | |

| Other cooked breakfast cereal | Popcorn: regular | |

| Other fruit juices | Potato chips or corn chips | |

| Other nuts | Potatoes, baked, boiled or mashed | |

| Pancakes or waffles | Pretzels | |

| Pasta | Regular hamburger | |

| Peanut butter | Sour cream | |

| Peanuts | soya milk | |

| Peas or lima beans | Tea | |

| Pie, home-baked or ready-made | Tofu or soyabeans | |

| Pizza | Tomato sauce | |

| Popcorn: regular | Tortillas | |

| Potato chips or corn chips | ||

| Potatoes, baked, boiled or mashed | ||

| Pretzels | ||

| Prunes | ||

| Regular hamburger | ||

| Salad dressing | ||

| Sauerkraut | ||

| Sour cream | ||

| Soya milk | ||

| Tea | ||

| Tofu or soyabeans | ||

| Tomato sauce | ||

| Tortillas | ||

| Walnuts | ||

| Yogurt | ||

| Yogurt-plain, low-carb | ||

| Plain or carbonated water | ||

| Soya or Worcestershire sauce |

Table 2.

Foods items that required discussion and further review in the Growing Up Today Study

| All foods with discordant categorisation n 94 of 315 | Foods requiring additional review n 51 | Foods in sensitivity analysis n 29 |

|---|---|---|

| Apple juice and other fruit juices | Apples or applesauce | Apples or applesauce |

| Apples or applesauce | Baked chips, e.g., baked lays | Baked chips, e.g., baked lays |

| Bagels, English muffins or rolls include breakfast sandwiches | Brownies | Cake |

| Baked chips, e.g., baked lays | Burrito: beans | Chicken or turkey sandwich |

| Beans or lentils include baked beans | Burrito: beef or pork | Clear soup (with rice, noodles, vegetables) |

| Beef (steak, roast) or lamb as main dish | Burrito: chicken or turkey | Corn chips/Doritos |

| Brownies | Burrito: tofu | Corn chips/Doritos |

| Burrito: beans | Burrito: vegetables | Cornbread |

| Burrito: beef or pork | Cake | Cornbread |

| Burrito: chicken or turkey | Cheeseburger | French toast |

| Burrito: tofu | Chicken or turkey sandwich | French toast |

| Burrito: vegetables | Clear soup (with rice, noodles, vegetables) | Grilled cheese |

| Cake | Coleslaw | Lasagne/baked ziti/ravioli |

| Cheese | Cookies | Pancakes or waffles |

| Cheeseburger | Corn chips/Doritos | Pancakes or waffles or French toast |

| Chicken or turkey as main dish | Corn chips/Doritos | Pancakes or waffles |

| Chicken or turkey sandwich | Cornbread | Pie |

| Clear soup (with rice, noodles, vegetables) | Cornbread | Popcorn |

| Coffee – not decaf | Cream (milk) soups or chowder | Potato chips |

| Coleslaw | Danish, sweet rolls, pastry | Pudding |

| Cookies | Doughnuts | Regular potato chips, corn chips, Doritos |

| Corn chips/Doritos | French fries | Roast beef or ham sandwich |

| Corn chips/Doritos | French toast | Sandwich or wrap: beef |

| Cornbread | French toast | Sandwich or wrap: chicken or turkey |

| Cornbread | Grilled cheese | Sandwich or wrap: tuna |

| Cottage or ricotta cheese | Hamburger | Sandwich or wrap: veggie (no meat) |

| Cream (milk) soups or chowder | Lasagne/baked ziti/ravioli | Tea – hot or iced |

| Danish, sweetrolls, pastry | Macaroni and cheese | Tomato sauce, e.g., spaghetti sauce |

| Donuts | Pancakes or waffles | Tuna sandwich |

| Eggrolls | Pancakes or waffles or French toast | |

| Fish sticks, fish cakes or fish sandwich | Pancakes or waffles | |

| French fries | Peanut butter sandwich (plain or with jelly, fluff, etc.) | |

| French toast | Pie | |

| French toast | Pizza | |

| Fruit drinks/pouch, lemonade, Sunny D, Koolaid, sugared ice tea or other non-carbonated fruit drink – NOT juice | Popcorn | |

| Fruit drinks/punch, lemonade, Sunny D, Koolaid or other non-carbonated fruit drink (No juice) | Potato chips | |

| Grilled cheese | Pudding | |

| Hamburger | Regular potato chips, corn chips, Doritos | |

| Hawaiian Punch, lemonade, Koolaid or other non-carbonated fruit drink | Roast beef or ham sandwich | |

| Hawaiian Punch, lemonade, sport & fruit drinks | Sandwich or wrap: beef | |

| Jams, jellies, preserves, syrup, honey or fluff exclude sandwiches | Sandwich or wrap: chicken or turkey | |

| Lasagne/baked ziti/ravioli | Sandwich or wrap: tuna | |

| Liver | Sandwich or wrap: veggie (no meat) | |

| Macaroni and cheese | Spaghetti with tomato sauce | |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): beef, pork or lamb | Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – beans | |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): chicken or turkey | Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – beef | |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): fish | Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – beef and beans | |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): tofu | Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – chicken | |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): vegetables | Tea – hot or iced | |

| Noodles, pasta | Tomato sauce, e.g., spaghetti sauce | |

| Onion rings, cooked onions or soup (1/2 cup) | Tuna sandwich | |

| Orange juice | ||

| Pancakes or waffles | ||

| Pancakes or waffles or French toast | ||

| Pancakes or waffles | ||

| Peaches, plums, apricots (fresh, canned or dried) | ||

| Peanut butter sandwich (plain or with jelly, fluff, etc.) | ||

| Peanuts, nuts | ||

| Peas or lima beans (fresh, frozen, canned) or soup | ||

| Pie | ||

| Pizza | ||

| Popcorn | ||

| Pork, ribs or ham as main dish | ||

| Potato chips | ||

| Potato salad | ||

| Pretzels | ||

| Pudding | ||

| Regular potato chips, corn chips, Doritos | ||

| Rice | ||

| Roast beef or ham sandwich | ||

| Salad dressing (not low energy) | ||

| Salami, bologna or other deli meat sandwich | ||

| Salsa | ||

| Sandwich or wrap: beef | ||

| Sandwich or wrap: chicken or turkey | ||

| Sandwich or wrap: tuna | ||

| Sandwich or wrap: veggie (no meat) | ||

| Shrimp, lobster, scallops | ||

| Soya Milk (glass or with cereal) | ||

| Spaghetti with tomato sauce | ||

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – beans | ||

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – beef | ||

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – beef and beans | ||

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – chicken | ||

| Tea – hot or iced | ||

| Tofu | ||

| Tofu, soyaburgers, miso, edamame or other soya dish | ||

| Tofu/soyaburgers/other meat substitutes | ||

| Tomato sauce, e.g., spaghetti sauce | ||

| Tomatoes/tomato juice | ||

| Tortilla – no filling | ||

| Tuna sandwich | ||

| Wine or wine cooler | ||

| Yogurt – not frozen |

The final NOVA classification of food items in the NHS and the HPFS cohorts is presented in Table 3. Table 4 presents the NOVA classification of the GUTS food items. The classification of the food lists of the FFQs formed the basis for the development of four different indicators that reflected participant consumption of ultra-processed foods in the cohorts – absolute kilocalories from ultra-processed foods, percentage of kilocalories from ultra-processed foods, percentage of grams of ultra-processed foods and the servings per day from ultra-processed foods.

Table 3.

The classification of all food items captured by the semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires of the Nurses’ Health Studies I and II, and the Health Professionals follow-up study, into the NOVA groups of minimally processed foods (1), processed culinary ingredients (2), processed foods (3), and ultra-processed foods (4)

| Food item | NOVA group assignment |

|---|---|

| 1−2 % Milk | 1 |

| Alfafa sprouts | 1 |

| Apple juice cider | 3 |

| Applesauce | 4 |

| Apricots | 1 |

| Avocado | 1 |

| Bacon | 4 |

| Banana | 1 |

| Beans or lentils | 1 |

| Beef, calf, pork liver | 1 |

| Beef, lamb as a main dish | 1 |

| Beef, pork hot dogs | 4 |

| Beef, pork, lamb sandwicha | 1a |

| Beer | 3 |

| Beets | 1 |

| Blueberries | 1 |

| Breaded fish cakes, pieces, sticks | 4 |

| Breakfast bar | 4 |

| Broccoli | 1 |

| Brown rice | 1 |

| Brownies | 4 |

| Brussels sprouts | 1 |

| Butter | 2 |

| Caffeine-free coke pepsi | 4 |

| Cake, home-baked | 1 |

| Cake, ready-made | 4 |

| Candy bar with chocolate | 4 |

| Candy bar without chocolate | 4 |

| Canned peaches | 4 |

| Canned pear | 4 |

| Canned tuna | 3 |

| Cantaloupe | 1 |

| Carrots | 1 |

| Cauliflower | 1 |

| Celery | 1 |

| Chicken or turkey hot dogs | 4 |

| Chicken or turkey liver | 1 |

| Chicken or turkey sandwicha | 1a |

| Chicken or turkey, with skin | 1 |

| Chicken or turkey, without skin | 1 |

| Chocolate bars | 4 |

| Chowder or cream soup | 4 |

| Coffee | 1 |

| Coke, Pepsi cola | 4 |

| Cold breakfast cereal | 4 |

| Cooked cabbage | 1 |

| Cooked carrots | 1 |

| Cooked oatmeal, oatbran | 1 |

| Cookies, brownie ready-made | 4 |

| Cookies, fat free, reduced fat | 4 |

| Cookies, home-baked | 1 |

| Maize | 1 |

| Cottage ricotta cheese | 3 |

| Creama | 2a |

| Cream cheese | 4 |

| Crispbreads | 3 |

| Cucumber | 1 |

| Dairy coffee drink | 4 |

| Dark chocolate bars | 4 |

| Dark meat fish | 1 |

| Decaffeinated coffee | 1 |

| Diet nutrition drinks, Slimfast | 4 |

| Doughnuts | 4 |

| Dried cranberries | 1 |

| Eggplant, zucchini, summer squash | 1 |

| Energy bar | 4 |

| Energy or high protein bars | 4 |

| English muffins, bagels, rolls | 4 |

| Ensure, boost or other meal replacement drinks | 4 |

| Fat free popcorn | 4 |

| Fat free, light crackers | 4 |

| Figs | 1 |

| Flavoured yogurt without Nutrasweet | 4 |

| French fried potatoes | 4 |

| Fresh apples, pears | 1 |

| Fresh pears | 1 |

| Frozen yogurt, sherbet, ice cream | 4 |

| Garlic | 1 |

| Grapefruit | 1 |

| Grapefruit juice | 1 |

| Grapefruit or grapefruit juice | 1 |

| Green, red peppers | 1 |

| Hamburger, lean or extra lean | 1 |

| Hawaiian punch | 4 |

| Herbal or decaf tea | 1 |

| High-protein, low-carb candy bar | 4 |

| Home-made soup with bouillon | 4 |

| Home-made soup without bouillon cube | 1 |

| Home-made sweetroll, coffee cake | 1 |

| Hummus | 3 |

| Ice cream | 4 |

| Iceberg or head lettuce | 1 |

| Jams, jellies, preserves, honey | 4 |

| Kale, mustard or chard green | 1 |

| Ketchup or red chili sauce | 4 |

| Light beer | 3 |

| Liquor | 4 |

| Low-energy soda, caffeine free | 4 |

| Low-energy soda, Pepsi, 7-up | 4 |

| Low-fat, fat-free mayonnaise | 4 |

| Margarine | 4 |

| Mixed dried fruit | 1 |

| Mixed dried fruits | 1 |

| Mixed vegetables | 1 |

| Muffins or biscuits | 4 |

| Mushrooms | 1 |

| Mustard | 3 |

| Non-dairy whitener | 4 |

| Nutrasweet or Equal | 4 |

| Oat bran | 1 |

| Oil and vinegar dressing | 2 |

| Olive oil added to food | 2 |

| Olives | 3 |

| Omega-3 fortified including yolk | 1 |

| Onion as a garnish | 1 |

| Onion as a vegetable | 1 |

| Orange juice | 1 |

| Orange juice with calcium | 1 |

| Orange squash | 1 |

| Oranges | 1 |

| Other artificial sweetener | 4 |

| Other bran | 1 |

| Other canned fruit | 3 |

| Other carbon beverage | 4 |

| Other cheese | 3 |

| Other cooked breakfast cereal | 1 |

| Other fish | 1 |

| Other fruit juices | 1 |

| Other grains | 1 |

| Other low energy carb | 4 |

| Other low energy cola with caffeine | 4 |

| Other nuts | 1 |

| Pancakes or wafflesa | 1a |

| Pasta | 1 |

| Peach, apricots, plums | 1 |

| Peanut butter | 3 |

| Peanuts | 1 |

| Peas or lima beans | 1 |

| Pepper | 1 |

| Pie, home-baked | 1 |

| Pie, home-baked or ready-madea | 1a |

| Pie, ready-made | 4 |

| Pizza | 4 |

| Plain or carbonated water | 1 |

| Popcorn: regulara | 3a |

| Pork as a main dish | 1 |

| Potato chips or corn chipsa | 3a |

| Potatoes, baked, boiled or mashed | 1 |

| Pretzels | 3 |

| Processed meats, sausage | 4 |

| Prune juice | 1 |

| Prunes | 1 |

| Raisins or grapes | 1 |

| Raw carrots | 1 |

| Ready-made soup from can | 4 |

| Ready-made sweetroll, coffeecake | 4 |

| Red chili sauce | 4 |

| Red wine | 3 |

| Regular crackers | 4 |

| Regular hamburger | 1 |

| Regular mayonnaise | 4 |

| Romaine or leaf lettuce | 1 |

| Rye, pumpernickel bread | 4 |

| Salad dressing | 4 |

| Salami, bologna, processed meat sandwiches | 4 |

| Salsa, picante, taco sauce | 4 |

| Salt | 2 |

| Sauerkraut | 3 |

| Shrimp lobster scallop | 1 |

| Skim or low-fat milk | 1 |

| Snack bars | 4 |

| Sour cream | 2 |

| Soya milka | 1a |

| Soya or Worcestershire sauce | 4 |

| Spinach, cooked | 1 |

| Spinach, raw | 1 |

| Splena | 4 |

| Spreadable butter | 4 |

| Strawberries | 1 |

| String beans | 1 |

| Sweetroll fat free or reduced fat | 4 |

| Tangerines, clementines, mandarin oranges | 1 |

| Tea | 1 |

| Toasted breads, bagel or English muffin | 4 |

| Tofu or soyabeans | 3 |

| Tomato juice | 3 |

| Tomato saucea | 3a |

| Tomato soup | 4 |

| Tomatoes | 1 |

| Tortillas | 3 |

| Uncooked cabbage, coleslaw | 1 |

| Walnuts | 1 |

| Watermelon | 1 |

| Wheat germ | 1 |

| White bread | 4 |

| White rice | 1 |

| White wine | 3 |

| Whole eggs | 1 |

| Whole milk | 1 |

| Whole wheat – whole grain bread | 4 |

| Yams or sweet potatoes | 1 |

| Yogurt | 1 |

| Yogurt artificially sweetened | 4 |

| Yogurt flavoured without nutrasweet | 4 |

| Yogurt-plain, low-carb | 1 |

Indicates foods to be categorised as ultra-processed (4) for sensitivity analysis.

Table 4.

The classification of all food items captured by the semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaires of the Growing Up Today Study, into the NOVA groups of minimally processed foods (1), processed culinary ingredients (2), processed foods (3) and ultra-processed foods (4)

| Food item | NOVA group assignment |

|---|---|

| 1 or 2 % milk | 1 |

| 1 % milk | 1 |

| 2 % milk | 1 |

| Added sugar | 2 |

| Apple juice, other 100 % fruit juices | 1 |

| Apple juice and other 100 % fruit juices | 1 |

| Apple juice and other fruit juices | 1 |

| Apples or applesauce | 1a |

| Apples or pears | 1 |

| Applesauce | 4 |

| Bacon | 4 |

| Bacon | 4 |

| Bagels, English muffins or rolls include breakfast sandwiches | 4 |

| Baked chips, e.g., Baked Lays | 3a |

| Bananas | 1 |

| Beans or lentils including baked beans | 1 |

| Beans/lentils/edamame | 1 |

| Beans/lentils/soybeans | 1 |

| Beef (steak, roast) or lamb as main dish | 1 |

| Beef or lamb as a main dish, e.g., as a steak or roast | 1 |

| Beef or pork hot dogs | 4 |

| Beef, pork or lamb fat | 1 |

| Beef/pork sausage | 4 |

| Beer | 3 |

| Beer, regular | 3 |

| Beets (not greens) | 1 |

| Biscuit | 4 |

| Biscuit/roll | 4 |

| Breakfast bars, e.g., Nutrigrain, granola, Kashi | 4 |

| Broccoli | 1 |

| Broccoli | 1 |

| Brown gravy | 4 |

| Brown rice | 1 |

| Brownies | 4 |

| Brussels sprouts | 1 |

| Burrito: beans | 4 |

| Burrito: beef or pork | 4 |

| Burrito: chicken or turkey | 4 |

| Burrito: tofu | 4 |

| Burrito: vegetables | 4 |

| Butter | 2 |

| Butter – not margarine | 2 |

| Cake | 1a |

| Cake or snack cakes, e.g., Twinkies | 4 |

| Canned tuna | 3 |

| Canola oil | 2 |

| Cantaloupe | 1 |

| Cantaloupe, melons | 1 |

| Carbonated, low-cal ‘diet’ beverage with caffeine (e.g., Diet Coke) | 4 |

| Carrots, cooked | 1 |

| Carrots, cooked | 1 |

| Carrots, raw | 1 |

| Carrots, raw | 1 |

| Celery | 1 |

| Celery | 1 |

| Cereal/Granola bar, like Nature Valley, Quaker or Special K | 4 |

| Cheese | 3 |

| Cheese, eaten alone or added to main dish, sandwich or quesadilla | 3 |

| Cheeseburger | 4 |

| Chicken nuggets | 4 |

| Chicken or turkey as a main dish (e.g., fried or roasted) with skin, including grounded | 1 |

| Chicken or turkey as a main dish, without skin | 1 |

| Chicken or turkey as main dish | 1 |

| Chicken or turkey hot dogs or sausages | 4 |

| Chicken or turkey sandwich | 1a |

| Chicken or turkey skin | 1 |

| Chocolate like Hershey's or M & M's | 4 |

| Chocolate candy like Hershey's, Snickers or M & M's | 4 |

| Chocolate candy like Snickers or M & M's | 4 |

| Chocolate milk | 4 |

| Chocolate milk or any flavoured milk | 4 |

| Chocolate or other flavoured milk | 4 |

| Chocolate, e.g., Hershey's or M&M's | 4 |

| Clear soup (with rice, noodles, vegetables) | 3a |

| Coffee – not decaf. | 1 |

| Coffee drinks – latte, Coolers, Coolatas, Frappuccinos, Mochachinos | 4 |

| Cold breakfast cereal | 4 |

| Cold breakfast cereal | 4 |

| Coleslaw | 4 |

| Collard greens/kale | 1 |

| Collard greens/kale/cooked spinach | 1 |

| Cooked oatmeal, including instant | 1 |

| Cookies | 4 |

| Maize | 1 |

| Maize | 1 |

| Corn chips/Doritos | 3a |

| Corn oil | 2 |

| Cornbread | 3a |

| Cornbread | 3 |

| Cottage cheese | 3 |

| Cottage or ricotta cheese | 3 |

| Crackers, e.g., Cheez-its or Ritz | 4 |

| Crackers, like Wheat Thins or Ritz | 4 |

| Cream (milk) soups or chowder | 1 |

| Cream cheese | 4 |

| Cream cheese | 4 |

| Cream, e.g., coffee, sour (exclude fat free) | 2 |

| Danish, donut, sweetroll or pastry | 4 |

| Danish, sweetrolls, pastry | 4 |

| Dark bread | 4 |

| Dark meat fish, e.g., tuna steak, salmon, sardines, swordfish | 1 |

| Decaffeinated coffee | 1 |

| Diet soda | 4 |

| Donuts | 4 |

| Eggrolls | 1 |

| Eggs | 1 |

| Eggs, e.g., scrambled, fried, in breakfast sandwich | 1 |

| Energy bar (like Power or Cliff Bar) | 4 |

| Energy bar, e.g., Powerbar, Clif Bar, Lunabar | 4 |

| Energy drink – (e.g., Red Bull), Regular energy drinks | 4 |

| Energy drink – (e.g., Red Bull), Sugar free, low energy or low carb energy drinks | 4 |

| Energy drink – Red Bull, Rock Star | 4 |

| English muffins or bagels | 4 |

| Fish sticks, fish cakes or fish sandwich | 4 |

| French fries | 4 |

| French fries | 4 |

| French toast | 1a |

| Fresh fish as main dish | 1 |

| Frozen yogurt | 4 |

| Frozen yogurt or low-fat ice cream | 4 |

| Fruit drinks/pouch, lemonade, Sunny D, Koolaid, sugared ice tea or other non-carbonated fruit drink – NOT juice | 4 |

| Fruit snacks or fruit rollups | 4 |

| Fun fruit or fruit rollups | 4 |

| Graham crackers | 4 |

| Grapes | 1 |

| Green/red peppers | 1 |

| Green/red/yellow peppers | 1 |

| Greens/kale | 1 |

| Grilled cheese | 3a |

| Hamburger | 4 |

| Hawaiian Punch, lemonade, Koolaid or other non-carbonated fruit drink | 4 |

| Hawaiian Punch, lemonade, sport & fruit drinks | 4 |

| High protein bar (like MetRx or Balance Bar) | 4 |

| High protein bar, e.g., Zone or Balance Bar | 4 |

| High protein shake or drink, e.g., whey or soya | 4 |

| Hot breakfast cereal, like oatmeal, grits | 1 |

| Hot dogs | 4 |

| Hot tea | 1 |

| Ice cream | 4 |

| Ice cream | 4 |

| Iced tea – sweetened | 4 |

| Instant Breakfast | 4 |

| Instant breakfast drink | 4 |

| Instant Breakfast Drink/High Protein Shake or Drink | 4 |

| Jams, jellies, preserves, syrup, honey or fluff, exclude sandwiches | 4 |

| Jello | 4 |

| Ketchup | 4 |

| Ketchup | 4 |

| Lasagne/baked ziti/ravioli | 1a |

| Lettuce/tossed salad | 1 |

| Lettuce/tossed salad | 1 |

| Light beer, e.g., Bud Light or Natural Light | 3 |

| Liquor, like vodka or rum | 4 |

| Liver | 1 |

| Low energy or low-fat salad dressing | 3 |

| Low energy or low-fat salad dressing | 3 |

| Low-fat or whole milk coffee dairy drinks, e.g., Cappuccino, Mocha, Latte | 4 |

| Low-fat or whole milk iced coffee dairy drinks, e.g., Coffee Coolatta, Frappuccino | 4 |

| Macaroni and cheese | 1 |

| Margarine – not butter | 4 |

| Mayonnaise | 4 |

| Mayonnaise | 4 |

| Meatballs or meatloaf | 1 |

| Milk | 1 |

| Milkshake or frappe | 4 |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): beef, pork or lamb | 4 |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): chicken or turkey | 4 |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): fish | 4 |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): tofu | 4 |

| Mixed other dishes (e.g., Pad Thai, chili, Frz. dinners): vegetables | 4 |

| Mixed vegetables | 1 |

| Mixed vegetables | 1 |

| Muffin | 4 |

| Nachos with cheese | 4 |

| Non-fat coffee dairy drinks, e.g., Cappuccino, Mocha, Latte | 4 |

| Non-fat iced coffee dairy drinks, e.g., Coffee Coolatta, Frappuccino | 4 |

| Noodles, pasta | 1 |

| Oatmeal | 1 |

| Oatmeal and other hot breakfast cereal, like farina, grits | 1 |

| Olive Oil | 2 |

| Onion rings, cooked onions or soup | 1 |

| Onions as a garnish or in salad | 1 |

| Orange juice | 1 |

| Orange juice | 1 |

| Oranges, grapefruit | 1 |

| Other candy bars (Milky Way, Snickers) | 4 |

| Other candy bars, e.g., Milky Way, Snickers | 4 |

| Other candy without chocolate (Skittles) | 4 |

| Other carbonated, low-cal beverage without caffeine, (e.g., Diet 7-Up) | 4 |

| Other cooked breakfast cereal | 1 |

| Other fish, e.g., cod, haddock, halibut | 1 |

| Other grains, like kasha, couscous, bulgur | 1 |

| Other hot breakfast cereal, like farina or grits | 1 |

| Other nuts | 1 |

| Other regular carbonated beverage with sugar (e.g., 7-Up) | 4 |

| Pancakes or waffles | 1a |

| Pancakes or waffles or French toast | 1a |

| Pasta (e.g., spaghetti with sauce, lasagne): chicken or turkey | 1 |

| Pasta (e.g., spaghetti with sauce, lasagne): vegetable | 1 |

| Pasta (e.g., spaghetti with sauce, lasagne): beef/hamburger/pork | 1 |

| Pasta (e.g., spaghetti with sauce, lasagne): plain | 1 |

| Peaches, plums, apricots | 1 |

| Peaches, plums, apricots (fresh, canned or dried) | 1 |

| Peanut butter sandwich (plain or with jelly, fluff, etc.) | 4 |

| Peanut butter, plain exclude sandwiches | 1 |

| Peanuts | 3 |

| Peanuts, nut | 3 |

| Pears | 1 |

| Peas or lima beans | 1 |

| Peas or lima beans or soup | 1 |

| Pie | 1a |

| Pizza | 4 |

| Popcorn | 3a |

| Popsicles | 4 |

| Poptarts | 4 |

| Pork, ribs or ham as main dish | 1 |

| Posicles | 4 |

| Potato chips | 3a |

| Potato salad | 1 |

| Potato salad | 1 |

| Potatoes – baked, boiled, mashed | 1 |

| Potatoes – baked or boiled, mashed | 1 |

| Pretzels | 3 |

| Pudding | 1a |

| Pudding – EXCLUDE sugar free | 4 |

| Raisins | 1 |

| Regular carbonated beverage with caffeine & sugar, (e.g., Coke, Pepsi, Mt. Dew, Dr. Pepper) | 4 |

| Regular hot tea with caffeine, including green tea | 1 |

| Regular potato chips, corn chips, Doritos | 3a |

| Rice | 1 |

| Roast beef or ham sandwich | 1a |

| Safflower oil | 2 |

| Salad dressing (not low energy) | 1 |

| Salad dressing (not low energy) | 1 |

| Salami, bologna or other deli meat sandwich | 4 |

| Salsa | 1 |

| Salsa | 1 |

| Sandwich or wrap: beef | 1a |

| Sandwich or wrap: chicken or turkey | 1a |

| Sandwich or wrap: peanut butter & jelly/fluff | 4 |

| Sandwich or wrap: salami, bologna or other deli meat | 4 |

| Sandwich or wrap: tuna | 1a |

| Sandwich or wrap: veggie (no meat) | 1a |

| Sausage | 4 |

| Seeds (Sunflower or Pumpkin) | 1 |

| Seeds, e.g., sunflower or pumpkin | 1 |

| Shrimp, lobster or scallops as a main dish | 1 |

| Shrimp, lobster, scallops | 1 |

| Skim/non-fat milk | 1 |

| Skim/non-fat milk (glass or with cereak) | 1 |

| Smoothies (e.g., medium Jamba Juice or Orange Julius) | 1 |

| Snack cakes, like Ring Dings/Swiss Rolls/Twinkies | 4 |

| Snack cakes, like Twinkies | 4 |

| Soda – not diet | 4 |

| Soda – not diet | 4 |

| Soya milk (glass or with cereal) | 4 |

| Soya milk, any flavour | 4 |

| Soyabean oil | 2 |

| Spaghetti or other pasta with tomato sauce | 1 |

| Spaghetti with tomato sauce | 1 |

| Spinach | 1 |

| Spinach, raw as in salad | 1 |

| Sport drinks – Powerade or Gatorade | 4 |

| Spreadable butter (butter mixed with oil to make it soft and spreadable) | 4 |

| Strawberries | 1 |

| String beans | 1 |

| String beans | 1 |

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas | 4 |

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – Beans | 4 |

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – Beef | 4 |

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – Beef and Beans | 4 |

| Tacos/burritos/enchiladas – Chicken | 4 |

| Tea – hot or iced | 1a |

| Tofu | 3 |

| Tofu, soyaburgers, miso, edamame or other soya dish | 4 |

| Tofu/soyaburgers/other meat substitute | 4 |

| Tomato juice or V8 | 1 |

| Tomato sauce, e.g., spaghetti sauce | 3a |

| Tomatoes | 1 |

| Tomatoes | 1 |

| Tomatoes/tomato juice | 1 |

| Tortilla – no filling | 3 |

| Tortilla, e.g., tacos, quesadillas (exclude burritos) | 3 |

| Tuna sandwich | 3a |

| Vegetable oil | 2 |

| Veggieburger | 4 |

| Walnuts | 1 |

| Water – tapped or bottled | 1 |

| Watermelon | 1 |

| Wheat or dark bread | 4 |

| Whipped cream | 4 |

| Whipped cream – EXCLUDE coffee drinks and/or fat free | 2 |

| White bread, pita bread or toast | 4 |

| White or pita bread, exclude sandwiches | 4 |

| White rice | 1 |

| Whole milk | 1 |

| Whole milk (glass or with cereal) | 1 |

| Whole wheat or whole grain bread, include toast | 4 |

| Whole wheat or whole grain, exclude sandwiches | 4 |

| Wine or wine cooler | 4 |

| Yams/sweet potatoes | 1 |

| Yams/sweet potatoes | 1 |

| Yogurt – not frozen | 4 |

| Yogurt – plain, not frozen | 1 |

| Yogurt – artificially sweetened (e.g., light peach) | 4 |

| Yogurt – sweetened (e.g., strawberry, vanilla) | 4 |

| Zucchini, summer squash, eggplant | 1 |

Items will not add up to 315 – only one of two or more near-identical items (e.g., Corn chips/Doritos; Corn chips or Doritos) have been presented here.

Indicates foods to be categorised as ultra-processed (4) for sensitivity analysis.

Discussion

This article details the process of categorising food items into the four NOVA groups and identifying the ultra-processed proportion of the FFQ food lists of the NHS-I and II, the HPFS and the GUTS cohorts. Over 70 % of the food items across all cohorts were assigned into one of the four NOVA groups after the first attempt at categorisation, based on published definitions that account for differences in processing between groups and their accompanying example products. The approach to classifying the remaining 30 % of food items involved discussions with experts that were informed by insights from the research dieticians, information provided by cohort-specific documents and scans of online grocery stores.

A conservative approach to the classification of some of the more challenging food items was adopted. This meant that only food items that could be justifiably considered ultra-processed based on information from cohort-specific documents were assigned to this NOVA group. The nutrient composition of the product was never considered in the categorisation process. In the handful of instances of uncertainty, a non-ultra-processed NOVA group was assigned as the primary classification and the food items were flagged for future sensitivity analysis where they could be re-categorised as ultra-processed. It is therefore reasonable to assume that the ultra-processed foods may be underestimated, and caution is needed in the interpretation of the future absolute intake of ultra-processed foods estimated from these FFQs. While this may have an attenuating effect on any future diet–disease relationship studied, the recategorisation planned for sensitivity analyses will help measure the variability associated with this approach.

Besides the resources mentioned in this article to help with the NOVA categorisation of dietary data, additional resources may be considered. Since there is no one gold-standard for applying the NOVA categorisation, the use of year-appropriate, context- or region-specific nationally representative surveys that use 24-h diet recalls or diet records could be used to gather more detailed information on dietary intake. The food items from these surveys could help determine the level of processing of certain challenging products. For instance, the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) in the US could be used to provide some insight into the processing grade of certain challenging foods if there was no access to cohort-specific resources. Information on complementary aspects of participant dietary behaviour like their frequency of eating out, purchase of branded packaged foods, perceived consumption of branded products, etc., may also be used to corroborate the NOVA classification of their diet. Previously, researchers have used participant report of percentage of brands of ultra-processed foods and home-made foods to resolve uncertainty and reach consensus in categorising dietary data collected using 24-h diet records(20). This additional information was used after all consumed food items had been categorized according to NOVA by study dietitians and reviewed by an expert panel.

Alternative approaches were considered but not implemented. In the present approach, composite food preparations with multiple ingredients were considered in their entirety when being assigned to a NOVA group, informed by key information contained in their item descriptions (home-made, ready-made, takeaway, frozen, etc.), along with information of the ingredient lists of equivalent products from the websites of leading retailers. Alternatively, home-made composite dishes could be divided into their ingredients and the individual ingredients could then be assigned to a NOVA group. Another alternative approach might classify food items into more than one NOVA group with appropriate resources justifying the allocation of a percentage of the food item into each group. For instance, ‘Pie, home-baked or ready-made’ could be split to allocate 60 % of its nutrient profile to the minimally processed group and 40 % to the ultra-processed group. This approach of dividing the nutrient profile of the food item into more than one NOVA group has been done before(6,21). It may either be an equal split between different NOVA groups or be divided in a proportion that is informed by other sources(21). Validation studies will be needed to estimate the misclassification minimised in determining the ultra-processed foods by these approaches.

Once validated, this approach could be used in future studies to minimise the misclassification associated with estimating the ultra-processed fraction of the diet and could help assess diet–disease relationships more accurately. It could also be used to identify ultra-processed foods from databases that contain information on dietary intake, food product acquisition, or food item sales. The identification of specific barriers faced at each stage of the categorisation process could be used to inform data-driven algorithms categorising dietary intake and inform the refinement of existing dietary assessment instruments to more accurately reflect the level of processing of food items. Including specific information in dietary assessment instruments on the processing of certain food items (e.g., ‘home-made from scratch’), including brand names of packaged products where possible (for branded breakfast cereal and breads for instance), capturing the place of preparation (at restaurant, street-food, take-aways), as well as the manner of preparation of mixed dishes and the types of ingredients used (e.g., ‘from scratch with fresh ingredients’, ‘pre-made and frozen using processed ingredients’) would make identifying the level of processing of food items easier(22). For FFQs, it could also mean adding more items or sub-dividing existing ones to differentiate between grades of processing and asking follow-up questions that give a better sense of the overall processing of the dietary pattern(23).

Finally, this work may serve as a protocol for applying the NOVA classification and identifying ultra-processed foods in other large-scale cohort studies. While it presents a specific example of an approach for the classification of FFQ food item, the various stages and the decision-points detailed in this manuscript could be modified based on context-specific needs and applied to other studies. This work may also be valuable as a template for authors thinking about documenting and making transparent their method of classification to help increase the reproducibility of their research.

Strengths and limitations

The limitations of this approach are important to highlight. First, the present approach to classification assumed no changes to the food composition of the food item over time. As a result, the nutrient database from 2014 was used to determine the nutrient composition for all products irrespective of whether that product was listed in the FFQ in 1986 (first FFQ cycle in these cohorts) or in 2015 (the latest available FFQ cycle in these cohorts). The use of the nutrient database from 2014 likely confers a healthier nutrient composition to products that have been subject to reformulation(24,25). Second, changes to the grade of processing over time because reformulation of the products was not captured by the present approach. Thus, the classification of a food product as ultra-processed remained static over time. While it is likely that a small portion of foods switched between NOVA groups over the course of dietary data collection due to reformulation, future work would be needed to capture the evolution of the processing of these products.

A third limitation is related to the use of supermarket scans in informing categorisation. The asynchrony between the collection of the dietary information from participants and the website searches may result in the identification of different brands of products from the ones consumed by the participants and/or different levels of processing as gauged from the ingredient lists. In the present approach, ingredient lists of the most popular brands of products from 2019 to 2020 were used to reflect the processing of certain food items listed in FFQs from 1986 to 2015. To minimise the potential for misclassification, cohort-specific resources were given priority in informing the NOVA categorisation of most food items and the grocery website scans, while helpful, were only used to categorise a handful of products.

Finally, the food lists included a few food items that combined individual foods from different NOVA groups. While it is likely that the energetic contribution of each food was small, the approach to categorisation did not attempt to disaggregate the grouped foods to estimate the dietary contribution of each of the individual items. Single food items that were composite dishes (like baked dishes requiring multiple ingredients, some of which may be ultra-processed) were also not disaggregated into individual components, but instead, the dish in its entirety was categorised into a NOVA group.

The strengths of this approach were the triangulation of NOVA group assignment, expert review of the categorisation process, the use of supporting documents to inform the categorisation of the more challenging food items and the high transferability of the approach to categorising dietary data collected using other diet assessment methods in different contexts. The actual consumption levels as reported by the participants or participant demographics were not considered, so inherent systematic biases associated with the over- under-reporting of certain foods did not influence the categorisation strategy adopted.

Conclusions

This manuscript presents the strategy used in the identification of the ultra-processed portion of the food lists of FFQs in large-scale population studies. The iterative, conservative approach adopted, relied on discussions with experts and was informed by insights from the research dieticians, information provided by cohort-specific documents and scans of online grocery stores. All food items were assigned a primary NOVA group with some foods being ear-marked for further sensitivity analysis. Future work would be needed to certify the validity of this approach by comparing participant ultra-processed food consumption estimated through FFQs against diet records while using the present approach of dietary categorisation. An evaluation of the generalisability and feasibility of applying this approach to other study populations and contexts is also warranted. Documentation and discussions of alternative approaches for categorisation and the evolution of dietary assessment methods to better capture ultra-processed foods are encouraged.

Acknowledgements

N. K., S. R., E. M. S., J.-P. D.-C., M. D. made substantial contributions to the classification of the diet. L. S., F. F. Z., Q. S., T. T. F., C. M., W. W. provided expert input into the classification of the diet. N. K. led the development of the manuscript. S. R., E. M. S., J.-P. D.-C., M. D., L. S., F. F. Z., Q. S., T. T. F., C. M., W. W. gave critical feedback on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

N. K. was supported by a FAPESP fellowship (2019/22278-7). E. M. S was supported by a FAPESP fellowship (2018/17972-9).

The authors have no financial or non-financial competing interests to declare.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval

This study uses secondary data and is exempt from ethics approval.

References

- 1.Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, et al. (2019) Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr 22, 936–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane MM, Davis JA, Beattie S, et al. (2020) Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 observational studies. Obes Rev 22, 13146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Zhang Z, Yang H, et al. (2020) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health outcomes: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Nutr J 19, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pagliai G, Dinu M, Madarena MP, et al. (2020) Consumption of ultra-processed foods and health status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 3, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costa CDS, Assunção MCF, Loret de Mola C, et al. (2020) Role of ultra-processed food in fat mass index between 6 and 11 years of age: a cohort study. Int J Epi 50, 256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monge A, Canella DS, López-Olmedo N, et al. (2020) Ultra-processed beverages and processed meats increase the incidence of hypertension in Mexican women. Br J Nutr 126, 1–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendonça RDD, Pimenta AM, Gea A, et al. (2016) Ultraprocessed food consumption and risk of overweight and obesity: the University of Navarra Follow-Up (SUN) cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 104, 1433–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunha DB, da Costa THM, da Veiga GV, et al. (2018) Ultra-processed food consumption and adiposity trajectories in a Brazilian cohort of adolescents: ELANA study. Nutr Diabet 8, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva FM, Giatti L, de Figueiredo RC, et al. (2018) Consumption of ultra-processed food and obesity: cross sectional results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) cohort (2008–2010). Public Health Nutr 21, 2271–2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willett W (2012) Nutritional Epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu FB, Satija A, Rimm EB, et al. (2016) Diet assessment methods in the Nurses’ Health Studies and contribution to evidence-based nutritional policies and guidelines. Am J Public Health 106, 1567–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin-Moreno JM, Willett WC, Gorgojo L, et al. (1994) Dietary fat, olive oil intake and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer 58, 774–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis, et al. (2001) Comparative validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute food frequency questionnaires: The Eating at America's Table Study. Am J Epi 154, 1089–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández-Avila M, Romieu I, Parra S, et al. (1998) Validity and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire to assess dietary intake of women living in Mexico City. Salud Publica de Mex 40, 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, et al. (2016) Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses’ Health Studies. Am J Public Health 106, 1573–1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, et al. (1992) Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epi 135, 1114–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockett HR, Wolf AM & Colditz GA (1995) Development and reproducibility of a food frequency questionnaire to assess diets of older children and adolescents. J Am Diet Ass 95, 336–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rockett HR, Breitenbach M, Frazier AL, et al. (1997) Validation of a youth/adolescent food frequency questionnaire. Prev Med 26, 808–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willett WC, Sampson L, et al. (1985) Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epi 122, 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Srour B, Fezeu LK, Kesse-Guyot E, et al. (2019) Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). Br Med J 365, 1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romieu X, Khandpur N, Katsikari A, et al. Consumption of industrial processed foods and risk of premenopausal breast cancer among Latin American women: the PRECAMA study. Under review at Cancer Causes and Control. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2015) Guidelines on the Collection of Information on Food Processing Through Food Consumption Surveys. Rome: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willett WC (1994) Future directions in the development of food-frequency questionnaires. Am J Clin Nutr 59, 171S–174S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Camp D, Hooker NH & Lin CTJ (2012) Changes in fat contents of US snack foods in response to mandatory trans fat labelling. Public Health Nutr 15, 1130–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spiteri M & Soler LG (2018) Food reformulation and nutritional quality of food consumption: an analysis based on households panel data in France. Eur J Clin Nutr 72, 228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]