Abstract

Context

Multilevel church-based interventions may help address racial/ethnic disparities in obesity in the United States since churches are often trusted institutions in vulnerable communities. These types of interventions affect at least two levels of socio-ecological influence which could mean an intervention that targets individual congregants as well as the congregation as a whole. However, the extent to which such interventions are developed using a collaborative partnership approach and are effective with diverse racial/ethnic populations is unclear, and these crucial features of well-designed community-based interventions.

Objective

The present systematic literature review of church-based interventions was conducted to assess their efficacy for addressing obesity across different racial/ethnic groups (eg, African Americans, Latinos).

Data Sources and Extraction

In total, 43 relevant articles were identified using systematic review methods developed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Task Force on Community Preventive Services. The extent to which each intervention was developed using community-based participatory research principles, was tailored to the particular community in question, and involved the church in the study development and implementation were also assessed.

Data Analysis

Although 81% of the studies reported significant results for between- or within-group differences according to the study design, effect sizes were reported or could only be calculated in 56% of cases, and most were small. There was also a lack of diversity among samples (eg, few studies involved Latinos, men, young adults, or children), which limits knowledge about the ability of church-based interventions to reduce the burden of obesity more broadly among vulnerable communities of color. Further, few interventions were multilevel in nature, or incorporated strategies at the church or community level.

Conclusions

Church-based interventions to address obesity will have greater impact if they consider the diversity among populations burdened by this condition and develop programs that are tailored to these different populations (eg, men of color, Latinos). Programs could also benefit from employing multilevel approaches to move the field away from behavioral modifications at the individual level and into a more systems-based framework. However, effect sizes will likely remain small, especially since individuals only spend a limited amount of time in this particular setting.

Keywords: African Americans, church-based interventions, Latinos, obesity prevention

INTRODUCTION

While more than a third (35.7%) of the adult population in the United States is obese, acute disparities persist across ethnic/racial groups and vary on the basis of age, sex, and socioeconomic status.1 For example, the prevalence of obesity among African American women (51%) and Latina women (41%) is significantly higher than the rate among white women (31%).1 , 2 Irrespective of gender, African Americans seem to gain weight faster than whites (eg, 2.79 body mass index [BMI] units over 16 years compared to 2.0 BMI units).3 Obesity, in turn, increases the risk of numerous chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes, which disproportionately affects African Americans and Latinos.4 Health inequalities also result in financial burdens, particularly for men of color. Between 2006 and 2009, African American men incurred an estimated $341.8 billion in excess medical costs and Hispanic men incurred an additional $115 billion due to health inequalities.5

Community-based intervention efforts designed to address obesity-related disparities experienced by racial and ethnic groups have increasingly focused on mediating social institutions such as churches.6 Indeed, church-based interventions have emerged as a viable approach to promoting health and wellness among vulnerable communities of color given their reach (eg, 85% of Latinos and 87% of African Americans report a religious affiliation),7–9 their sociohistorical role in vulnerable communities (eg, the Black Church in the civil Rights Movement), and their potential as critical partners in improving the ethical treatment of vulnerable groups in health research.10 They have also been cited as a culturally appropriate, cost-effective setting that could propel the field of lifestyle interventions forward.11 , 12 The faith community includes specific places of worship, such as churches, or organizations that are affiliated with a particular faith or religion.13 Prior reviews of evidence-based obesity interventions among racial/ethnic minorities have generally included studies conducted in churches14 or exclusively focused on faith-based settings.15–17 Those that exclusively focused on churches noted multiple methodological limitations such as small sample sizes in these studies, lack of robust evaluative approaches, and short follow-up time frames.15 , 17 These reviews also noted that most faith-based studies have involved only women and African Americans, and that research with other ethnic minorities has tended to be exploratory.15 , 16

This review builds on this prior work by examining additional characteristics of these interventions within the broader church-based literature and applying a more expansive framework to understand elements of success among church-based obesity programs. For example, there seems to be broad agreement that several factors are critical to the success of church-based health programs, such as the need for collaboration, tailoring, and the use of community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles.13 , 18 , 19 Collaborations speak of the partnerships between congregations and outside organizations and have been shown to increase the likelihood that the program in question can be successfully replicated elsewhere.19 Tailoring is the extent to which program elements take into account issues such as culture, age, and religious beliefs that can make the intervention’s message more easily understood by congregation members.19 This is particularly important for obesity-specific interventions since it is unclear whether programs that incorporate religious beliefs into the curriculum are more successful than secular interventions delivered in faith-based settings.16 Use of CBPR principles in church-based obesity programs means the extent to which programs build effective and equal partnerships with churches to elicit trust and carry out the intervention, even though the partnership features of a study have not been assessed in previous reviews.

This review sought to address this gap by conducting a narrative review of congregation-based obesity interventions in order to inform the development of effective and sustainable obesity programs in church-based settings. Specifically, it sought to systematically review the church-based obesity intervention literature relating to the United States, to gain a deeper understanding of the current state of such interventions and their impacts on populations at increased risk for obesity. Further, it explores the extent to which these programs use CBPR principles such as collaboration and tailoring to offer future planners a survey of lessons learned in this field.

EVIDENCE ACQUISITION

Literature search

A 3-pronged search strategy was employed to identify journal articles on obesity interventions in church settings. First, a professional librarian searched multiple databases (PUBMED, Sociological Abstracts, PsycINFO, Cochrane databases, CINAHL, WorldCat, and Social Sciences Abstracts) using various combinations of the following search terms: obesity OR obese OR overweight OR body-mass index OR fruit* OR vegetable* OR exercise OR “physical activity” AND church* OR faith-based OR religion OR religion and psychology OR religious OR clergy. The literature was searched through August 2017. Publications were restricted to those written in English and conducted in the United States. Second, the National Cancer Institute (NCI)’s website on research-tested intervention programs was used. For the NCI database search, the topics selected were diet/nutrition, obesity, and physical activity, and the study setting selected was religious establishments (see http://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/index.do). Lastly, bibliographies of the studies included in previous related literature reviews were reviewed to ensure a comprehensive approach.

Study selection

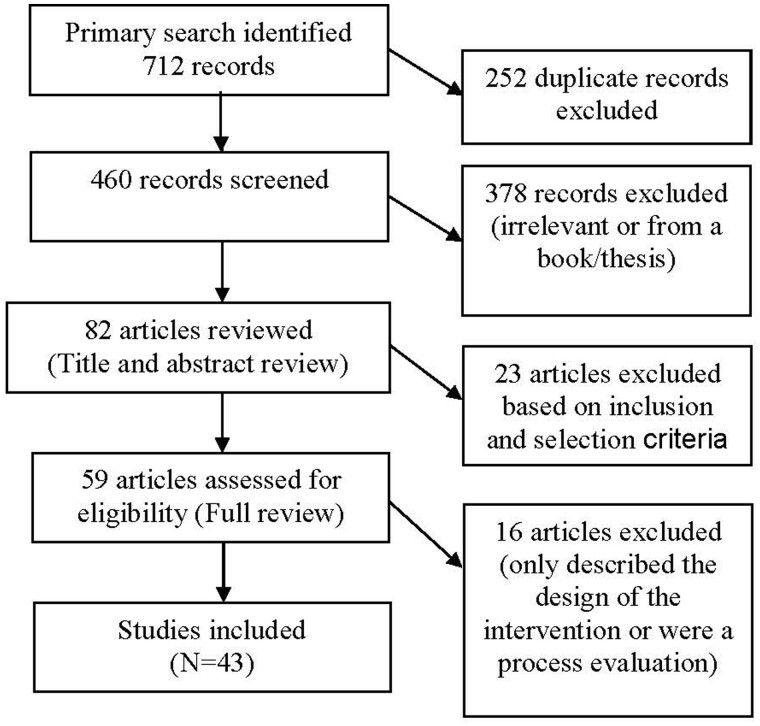

Figure 1 shows the search methodology and inclusion/exclusion criteria. The search yielded 712 journal articles, of which 252 were removed for being duplicates or nonrelevant material based on title review. Of the 460 articles screened, 378 were excluded owing to irrelevance, or because they were a thesis or book. From the 82 studies whose title and abstract were reviewed, the only articles included were original studies that used empirical, quantitative data to report the effects of an intervention designed for any faith-based setting (eg, church, faith-based organization) with at least 1 weight-related outcome (eg, BMI, diet, physical activity). Fifty-nine articles were selected for full review, and 16 were excluded because they only described the study design or reported process evaluation data. After applying these criteria, 43 relevant articles were finally included in this study.20–47

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature selection process.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted using methods for conducting literature reviews developed for the Guide to Community and Preventive Services by the CDC’s Task Force on Community Preventive Services (Zaza S, Wright-de Aguero L, Briss PA, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med 2000;18(suppl 1):44–74). This approach was used since it facilitated systematic evaluation of each study through a standardized form that classified and described key characteristics of the intervention and evaluation (26 questions) and assessed the quality of the study’s execution (23 questions). Two independent reviewers conducted the data abstraction and verified the results of the data points: study population characteristics (ie, age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status), study design and setting, intervention variables, theoretical model, follow-up time, and components of tailoring. These same reviewers verified the abstraction results for selected clinical and behavioral outcomes (mean weight or BMI, physical activity, and dietary intake) and calculated standardized effect sizes across studies, providing standard errors or standard deviations (SDs) according to pre-established guidelines for literature reviews.48 For single-group pre-post effect sizes, the pre-intervention mean was subtracted from the post-intervention mean and divided by the pre-group or pooled SD. Cohen’s d was calculated for comparisons of intervention vs control groups when available, and reported according to Cohen’s conventions for small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8) effect sizes.49 , 50 For controlled trials, between-group effect sizes compared intervention and control group outcomes at follow-up assessment. For publications that reported data from multiple follow-up assessments, effect sizes were calculated for the assessment closest to the end of intervention for consistency across studies. Effect sizes were corrected for direction of outcome values so that positive effect sizes indicated improvement/risk reduction.

Using the same abstracted data, two independent reviewers verified the categorization of each study according to the 4 levels established by Lasater.51 This was done to systematically assess key aspects of the church-based approach, ie, the extent to which congregational members or leaders were involved in delivering the intervention and the extent to which the intervention incorporated religious/spiritual content. Studies were classifed as Level I if the church was simply a convenient location or a venue to recruit and track participants for an externally sponsored and implemented intervention, such that all or most intervention and evaluation activities occurred outside of the church. Level II signified studies in which the intervention was delivered in a church setting, but was mostly implemented by individuals from outside the church. Level III identified those studies in which trained religious organization volunteers delivered a significant portion of the intervention. Finally, Lasater Level IV signified interventions where trained religious organization volunteers delivered a significant portion of the intervention and there were substantial religious or spiritual components embedded in the intervention. In addition, studies that used CBPR methods were identified (Yes/No) since these can lead to more relevant and sustainable interventions and findings that are actionable. Studies that directly stated use of CBPR principles or mentioned collaborative partnerships for multiple phases of the study (ie, including intervention development) were classified as affirmative for the use of CBPR methods.

Lastly, studies were organized by design, from randomized (controlled) trials, to nonrandomized studies, to pre-intervention and post-intervention studies. This was done to facilitate comparison among similar studies across the identified metrics.

EVIDENCE SYNTHESIS

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 43 studies are presented in Table 1 and organized by design. Of the 43 studies, 22 were randomized by design, 6 were nonrandomized, and 15 were pre-post intervention studies. Six studies were conducted in single churches, and 14 studies were conducted in small groups of churches (ie, 2–9 churches). Four studies did not provide the number of churches, and the rest (19) were conducted in 10–49 churches and ranged in total sample size from 74 to 2519 participants. Only 2 studies focused on children, while the remaining studies focused on middle-aged or older adults. Thirty-five studies (81%) included entirely or largely (>70%) female samples. In terms of racial/ethnic composition, 32 studies focused only on African Americans, and only 5 focused exclusively on other races/ethnicities (ie, whites or Latinos). In terms of sociodemographic indicators such as education and income, most studies sampled individuals with a high-school education or higher, although education levels were not reported in 13 of the studies. There was more variation in terms of income among the studies that reported information on this indicator (which was only a little more than one third of the total studies). Over half of the studies were set in the southern USA, 23% were in cities in the northeast USA, and the rest of the studies reported western cities/counties, or an unspecified region (eg, the Midwest USA).

Table 1.

Descriptive information of church-based obesity-related interventions by study design (n = 43)

| Reference and program name (if reported) | Sample size | Study Population Demographics |

Intervention details | Delivered by | Theory | Duration/ frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Mean age, y | Female % | Race/ethnicity % | Education and/or income, %c | Region | |||||

| Randomized control trials | ||||||||||

| Arredondo et al (2017)52; Fe en Acción |

|

44.4 | 100 | 100 Latino | 45.4 HS+ 58.3 <$2K (monthly) | San Diego County, CA | I: group sessions (prayer, PA classes, handouts, discussion), LHA, MI calls, mailings, simpleins/ads, LHA walkability audits and environmental projects

|

Congregants | EM, formative research, MI | 12 mo/ varied |

| Bopp et al (2009)66; 8 Steps to Fitness |

|

52 | 80 | 100 AA | 91.4 HS+ 71 >$25K | SC | Group sessions (PA, scripture reading, discussion) pedometers, assignments, handouts | Congregants, church leaders | Formative research, SCT, TTM | 2 mo/ once a week |

| Bowen et al (2009)22; Eating for a Healthy Life |

|

54 | 85 | 89 W | 14 ≤HS | Seattle, WA | I: volunteer advisory board, interpersonal support, mailings, motivational messages, social activities, healthy eating sessions, policy, print materials

|

Healthy eating coordinator, congregants | MI, SLT, TTM | 9 mo/ varied |

| Campbell et al (1999, 2000)23 , 24; Black Churches United for Better Health |

|

53.8 | 73 | 98 AA | 67 HS 59 <$20K | NC | I: tailored simpleins, print materials, gardens, educational sessions, cookbook/ recipe tasting, FV, LHA, community coalitions, pastor support, grocer-vendor involvement, church activities

|

Congregants | EM, SCT, SSM, TTM | 20 mo/ varied |

| Duru et al (2010)26; Sisters in Motion |

|

72.8 | 100 | 100 AA | 23 <HS 53 <$2K (monthly) | Los Angeles, CA | I: group sessions (scripture reading, prayer, PA goal-setting/ reinforcement, pedometer competition), PA

|

Research assistant, local fitness instructor | NR | 2 mo/ once a week; 6 mo/ once a week |

| Kennedy et al (2005)29 |

|

44 | 90.2 | 100 AA | NR | Baton Rouge, LA | I1: group sessions (nutrition education)

|

Congregants | NR | 6 mo/ varied |

| Krukowski et al (2010)67 |

|

48.5 | 71 | 100 W | 68 college degree | South | I1: standard behavioral weight control group sessions (diabetes prevention)

|

Graduate student | NR | 4 mo/ once a week |

| McNabb et al (1997)53; PATHWAYS |

|

56.5 | 100 | 100 AA | 13 <HS | NR | I: group sessions (tailored dietary goals, problem solving, PA promotion)

|

Congregants | Discovery learning framework | 14 wk/ once a week |

| Murrock et al (2010)33 |

|

NR | 100 | 100 AA | NR | Midwest | I: group sessions (dance with gospel music)

|

Local dance instructor | SCT | 2 mo / twice a week |

| Resnicow et al (2001)37; Eat for Life |

|

43.9 | 73.3 | 100 AAb | 44 ≤HS 23 <$20K | Atlanta, GA | I1: faith-based healthy eating video, cookbook, print materials, gift cues, reminder call

|

Registered dietitian or dietetic intern | MI, SCT | 12 mo/ varied |

| Resnicow et al (2004)38; Body and Soul |

|

50.6 | 74.4 | 100 AAb | 33 ≤HS 28 <$30K | CA; GA; NC; SC; DE; VA | I: faith-based healthy eating video, cookbook, health fair, 2 MI calls, educational sessions, cooking classes, print materials, church-wide activities (3 nutrition events, 1 policy change)

|

Congregants | EM, MI, self- determination theory, SCT | 6 mo/ NR |

| Resnicow et al (2005)40; Go Girls! |

|

13.6 | 100 | 100 AAb | NR | Atlanta, GA | I: group sessions (nutrition/PA education, PA), 1-d retreat, pagers (tailored nutrition/PA messages), 4– 6 MI calls

|

Graduate- level counselor, dietitian, exercise physiologist, research staff | Formative research, MI, SCT | 6 mo/ once a week or once a month |

| Resnicow et al (2005)39; Healthy Body Healthy Spirit |

|

46.3 | 76.2 | 100 AAb | 28.9 ≤HS 11.6 <$20K | Atlanta, GA | I1: culturally targeted materials (faith-based healthy eating video, PA video, cookbook, PA guide, gospel music)

|

|

SCT, MI | 12 mo/ varied |

| Samuel-Hodge et al (2009)41; A New Dawn |

|

59 | 64 | 98.5 AA | 12.4 y (mean) 45 <$30K | NC | I: individual counseling (diet, barriers to behavioral change, psychosocial issues), group sessions (prayer, PA, PA education, recipe tasting) support calls, healthy eating/PA mailings

|

Registered dietitian, local health professional, congregants | Adult learning theory, SCT, TTM | 12 mo/ varied |

| Sattin et al (2016)54; Fit Body and Soul |

|

46 | 83.4 | 100 AA | 50.8 college+ | August a, GA | I: group sessions (spiritual messages, weight loss and behavioral modification strategies)

|

Congregants | MI, SCT | 12 wk/ once a week; 6 mo/ once a month |

| Trost et al (2009)42; Shining Like Stars |

|

8 | 51.4 | 23.9 AA 57.8 W | NR | KS | I: group sessions (faith-based PA curriculum), family devotional activities

|

Congregants | NR | 1 mo/ once a week |

| Webb et al (2017)68; Walking in Faith |

|

48.3 | 41 | 97.7 W | 81 graduate+ | PA | I: faith-based online PA curriculum

|

Web-based | SCT | 12 wk/ once a week |

| Wilcox et al (2007, 2007)43 , 44; Health-e-AME |

|

NR | 68 | 100 AAb | 52 ≤HS 36 <$25K | SC | I: praise aerobics, chair exercises, walking, group sessions (behavior change skills, scripture, PA, handouts), PA-related sermons, print materials, PA/healthy food at church events

|

Pastor, congregants | EM, TTM | 24–36 mo/ varied |

| Wilcox et al (2013)69; Faith, Activity, and Nutrition (FAN) |

|

54.1 | 75.7 | 99.4 AA | 10.3 <HS 42.7 <30K | SC | I: church leader trainings, cooks’ training, monthly mailings (health behavior change), incentives, handouts (simplein inserts, recipes), pastor mailings, messages from the pulpit, policies/ practices, stipend

|

Pastor, congregants | EM, SCT | 15 mo/ varied |

| Winett et al (2007)45; Guide to Health |

|

53 (median) | 67 | 23 AA | NR | South | I1: online curriculum (goals, nutrition/PA education, behavior change strategies)

|

Web-based | SCT | 3 mo/ once a week |

| Yanek et al (2001)46; Project Joy |

|

53 | 100 | 100 AA | 92 HS | Baltimore, MD | I1: group sessions of nutrition education, taste test or cooking demo, PA, discussion, retreat

|

Research staff, congregants | Formative research, community action and social marketing model, SLT | 12 mo/ varied |

| Young and Stewart (2006)47; Stretch– N’ Health |

|

48.3 | 100 | 100 AA | NR | Baltimore, MD | I: group sessions (gospel music, prayer, PA, discussion, print materials, buddy supports), handouts, individual PA plans

|

Certified aerobics instructor, local health educator | Formative research, SCT | 6 mo/ once a week |

| Nonrandomized Trials | ||||||||||

| Boltri et al (2011)21; Diabetes Prevention Program |

|

57.2 | 70.3 | 100 AA | NR | GA | I: 16-group sessions (prayer, diabetes prevention education, behavior change) | Congregants | SAT | 6–16 wk/ once a week |

| C: 6-group sessions | ||||||||||

| Faridi et al (2010)27; Partners reducing effects of diabetes (PREDICT) |

|

NR | 81.2 | 100 AA | 37 ≤HS 37 <$30K | New Haven and Bridgeport, CT | I: group sessions (diabetes prevention), individual meetings, advocacy activities

|

Congregants | NR | 12 mo/ varied |

| Harmon et al (2014)70; Dash of Faith |

|

61 | 69.6 | 100 AA | 87 HS+ | SC | I: group sessions (cooking, potlucks, discussion, nutrition education, guest speakers)

|

Consultant, guest speaker | Formative research, SCT | 3 mo/ once a week; 8 mo/ bimonthly |

| Kim et al (2008)30; Wholeness, Oneness, Righteousness, Deliverance (WORD) |

|

54.1 | 71 | 100 AA | 46 ≤HS 26 <$20K | NR | I: group sessions (nutrition/PA education, PA, health-focused bible study, prayer)

|

Congregants | SCT, SSM, TTM | 2 mo/ once a week |

| Parker et al (2010)35; Love, Inspiration, Family, Education (LIFE) |

|

50.7 | 100 | 100 AA | 11 <HS 16 <$10K | Rural SC | I: group sessions (spiritual messages, nutrition education, daily PA, provider discussions)

|

County extension educator | Formative research | 10 wk/ once a week |

| Tucker et al (2017)55; Health- Smart Church Program |

|

NR | 81.4 | 100 AA | 40 ≤HS 28.6 <$20K | Bronx, NYC, NY | I: individual coaching (goal-setting), group sessions (health-smart video, resource guide, discussion, health panel), PA classes

|

Pastor, church leaders, community member, health professional | HSET | 6 wk/ varied |

| Pre-post test studies | ||||||||||

| Barnhart et al (1998)20 | N = 16 NR | 60.5 | 100 | 100 AA | NR | Bronx, New York City (NYC), NY | Group sessions (nutrition education, goal setting, FV barriers, food advertising/la bels, recipes) | Research staff | Formative research | 6 wk/biweekly |

| Davis Smith et al (2007)71; Lifestyle Balance Church Diabetes Prevention Program |

|

NR | 70 | 100 AA | NR | Rural GA | Group sessions (nutrition education, PA, behavior change) | Research staff | NR | 6 wk/ once a week |

| Dodani and Fields (2010)25; Fit Body and Soul | N = 40 NR | 46 | 85.3 | 100 AA | 95 HS+ | Evans County, GA | Pastor-led sermons/ messages, group sessions, individual coaching/ assessments, print materials | Pastor, congregants | Formative research | 3 mo/ once a week |

| Goldfinger et al (2008)28; Project Healthy Eating, Active Lifestyles (HEAL) |

|

68.3 | 81 | 100 AA | 69 ≤HS 23 <$15K | Harlem, New York City, NY | Group sessions (portion control, nutrition, budget- friendly healthy eating, PA strategies) | Congregants | Formative research | 10 wk/ 8 sessions total |

| Gutierrez et al (2014)72; Fine, Fit, and Fabulous (FFF) |

|

NR | 88.3 | 58.5 AA, 41.5 Latinos | 73.2 HS+ | Bronx, NYC, NY | Group sessions (nutrition education, healthy eating techniques, spiritual messages, PA) | Consultant, trainer | Formative research | 3 mo/ once a week |

| Ivester et al (2010)73 |

|

53 | 65.9 | 98 W | NR | NC | Group sessions (prayer, nutrition education, PA), print materials, heart rate monitors, individual PA | NR | NR | 2 mo/ twice a week |

| Kumanyika and Charleston (1992)31; Lose Weight and Win |

|

51 | 100 | 98 AA | NR | Baltimore, MD | Group sessions (nutrition education, PA), nutrition and behavioral counseling, competitions | Registered dietitian, LHA, exercise instructor | NR | 2 mo/ once a week |

| Martinez et al (2012)32 |

|

43 | 100 | 100 Latinosa | 57 ≤HS

|

San Diego, CA | LHA-led walking groups (spiritual educational messages, prayers), PA class, sermons, print materials, health seminars, LHA walking audits, advocacy events | LHA, pastor | NR | 6 mo/ varied |

| McCoy et al (2017)74 | N = 82 NR | 52 | 87.8 | 100 AA | 100 HS+ 17 <$30K | MS | I: health text messages, weight loss competition

|

Phone-based | Formative research, HBM, IMB | 3 mo/ 3 times a week |

| Oexmann et al (2001)34; Lighten Up |

|

57 | 82 | 64 AA | NR | NC; SC | Group sessions (prayer, bible study, stories, diaries, spiritual health messages), support calls, behavior change checklist | NR | NR | 2 mo/ once a week |

| Peterson and Cheng (2011)36; Heart and Soul PA Program |

|

49.6 | 100 | 100 AA | 44 <HS 55 <$40K | Urban Midwestern city | Group sessions (PA, prayer, bible messages, social support domains), booklet | Nurse practitioner | Formative research, social comparison theory | 6 wk/ once a week |

| Whisenant et al (2013)75 |

|

NR | 89.3 | NR | NR | AL | I: group sessions (prayer, faith- based healthy living topics, bible study, PA)

|

Health experts; nutritionists, nurses, exercise physiologist, volunteers | NR | 3–6 mo/ varied |

| Whitt-Glover et al (2008)76 |

|

52 | 89 | 100 AA | 96% HS+ | NC | Group sessions (prayer, behavioral strategies to increase PA, PA, discussion, faith-based messages, incentives) | Certified fitness instructor, community LHA | SCT | 3 mo/ once a week |

| Williams et al (2015)77; Turn the Beat Around |

|

52 | 73.6 | 100 AA | 25.1 ≤HS | AL | Group sessions (prayer, stroke prevention curriculum, nutrition/ PA education, BP control, goal setting, food demo) | Congregants, county extension personnel | TTM | 3 mo/ biweekly |

| Yeary et al (2011)56; WORD |

|

50.8 | 84.6 | 100 AA | 42.3 ≤HS 69.2 <30K | AR | I; group sessions (faith-based messages, nutrition/ PA educational messages, behavioral strategies, PA), self- monitoring diaries | Congregants | Formative research, SCT, SSM | 16 wk/ once a week |

Note: Reported income is the annual household income unless otherwise noted; numbers were rounded to the whole percent; % unless otherwise noted.1

100% were of Mexican descent.

These studies did not report the racial/ethnic background of the study population. We are assuming it is 100% AA given the inclusion criteria and/or study focus.ccontrol.

Abbreviations: AA, African American; AL, Alabama; C, control or comparison group; CA, California; DASH, dietary approaches to stop hypertension; DE, Delaware; EM, ecological model; FV, fruits and vegetables; GA, Georgia; HBM, health belief model; HS, high school degree; HSET, health self-empowerment theory; HBM, xxxxx; I, intervention group; IMB, information-motivation-behavior skills model; KA, Kansas; LHA, lay health advisors(s); MD, Maryland; MI, motivational interviewing; NC, North Carolina; NR, not reported; NYC, New York City; PA, physical activity; SAT, social action theory; SC, South Carolina; SCT, social cognitive theory; SLT, social learning theory; SSM, social support models; TTM, transtheoretical (stages of change) model; VA, Virginia; W, White.

Interventions

Intervention details, including who delivered the interventions, are also included in Table 1. Most interventions used a face-to-face delivery modality, but a wide variety of methods were utilized, including group sessions, church-level activities, self-help (eg, via printed materials, videos, messaging), and motivational interviewing (MI) counseling. Over half used a peer-educator model (n = 24), while the other studies relied on professionals/research staff or automated means (phone/web/text) to deliver the program.

Twenty-five studies also mentioned a theoretical framework derived from formative research or established theory (eg, social learning theory, social cognitive theory; see the “Theory” column, Table 1). Of note is that only 5 studies reported using an ecological model in an attempt to change individual behavior through environmental changes at the church (eg, by increasing the availability of fruit & vegetables at church functions) and only a few programs were designed to affect organizational policy-related factors (ie, Body and Soul; Eating for a Healthy Life; and the Faith, Activity, and Nutrition Program, Fe en Acción). Most interventions incorporated activities solely at the individual level (eg, nutrition education classes, exercise sessions, one-on-one nutritional counseling). Most studies (n = 27) incorporated intervention periods of 6 months or less.

Evaluation design and primary outcomes

Findings for the selected primary outcomes and corresponding Lasater Levels are presented in Table 2. Of the 41 studies in which the Lasater Level was ascertainable, 1 (2.4%) was classified as Level 1, 17 (41.5%) as Level II, 10 (24.4%) as Level III, and 13 (31.7%) as Level IV. Over half of the studies used a biomarker (eg, weight, BMI, waist circumference) as the primary outcome, whereas others focused on a behavior; such as fruit and vegetable intake or level of physical activity. For pre-post changes in weight (measured in pounds or kilograms), waist circumference, or BMI (%), 19 of the 27 identified studies that measured these outcomes reported statistically significant changes. Only 7 studies reported a significant time-series difference between the intervention and comparison groups for measurements of weight, waist circumference, or BMI,29 , 30 , 45 , 46 , 52–54 and about half (n = 4) of these employed CBPR principles.30 , 46 , 52 , 54 Most of the 7 studies with significant time-series differences in weight outcomes (n = 6) were Lasater Level III or IV studies,29 , 30 , 46 , 52–54 indicating that the church had a significant role in the development and implementation of the BMI/weight intervention.30 , 46 , 54 Overall, of the 27 studies with biomarker outcomes, 19 (70%) demonstrated significant improvements in BMI, weight, or waist circumference. Of the 19 successful studies, the slight majority (63%; n = 12) were Lasater Level III or IV studies. It should be noted that the number of study outcomes exceeds the total number of studies (n = 43) because more than 1 outcome may have been measured per study.

Table 2.

Community partnering levels and intervention effects among church-based interventions by study design (n = 43)

| Reference | Post-treatment change* |

Effect size (Cohen’s d)c

|

Lasater Level | CBPR principles | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight/waist/BMI | Diet | PA | Weight | Diet | PA | |||

| Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||

| Arredondo et al (2017)52 | I-C: BMI: −0.43** |

|

0.23 |

|

III | Yes | ||

| Bopp et al (2009)66 | I: −1.9 kg/m2** (at 3 mo.) | NS | I: 0.012b (S) | NS | IV | Yes | ||

| Bowen et al (2009)22 |

|

NC | III | Yes | ||||

| Campbell et al (1999)23 |

|

|

IV | Yes | ||||

| Duru et al (2010)26 | NS | +7457 (steps/wk) among I compared to C** | NS | NC | II | No | ||

| Kennedy et al (2005)29 |

|

|

|

|

||||

| Krukowski et al (2010)67 | ||||||||

| McNabb et al (1997)53 |

|

|

III | No | ||||

| Murrock and Gary (2010)33 | NS | +41 units in PASE (at time 2**) | NS | 0.19b | II | Yes | ||

| Resnicow et al (2001)37 |

|

NC | II | Yes | ||||

| Resnicow et al (2004)38 |

|

|

IV | Yes | ||||

| Resnicow et al (2005)40 |

|

|

|

|

II | Yes | ||

| Resnicow et al (2005)39 | NS | NS | II | Yes | ||||

| Samuel- Hodge et al (2009)41 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | III | Yes |

| Sattin et al (2016)54 | I: −2.39 lb (baseline to 12 mo)** | NS | NC | NS | IV | Yes | ||

| Trost et al (2009)42 | +13 MVPA steps/min I vs C, averaged across time 1 to time 4** | NC | IV | No | ||||

| Webb et al (2017)68 | Accelerometer-based moderate PA time, I vs C: +16 min/wk** | 0.15 | II | No | ||||

| Wilcox et al (2007)44 | NS | NS | NS | NS | IV | Yes | ||

| Wilcox et al (2013)69 | NS | NS | NS | NS | IV | Yes | ||

| Winett et al (2007)45 |

|

|

|

II | No | |||

| Yanek et al (2001)46 |

|

|

IV | Yes | ||||

| Young and Stewart (2006)47 | NS | NS | II | Yes | ||||

| Nonrandomized Trials | ||||||||

| Boltri et al (2011)21 | I: −3.8 kg at program | 0.03

|

III | Yes | ||||

| completion, −1.9 kg at | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Faridi et al (2010)27 | NS | NS | III | Yes | ||||

| Harmon et al (2014)70 | I: +2.3 servings F/V per day at 2 mo vs baseline | I: 0.22 | II | Yes | ||||

| Kim et al (2008)30 | I: −3.0 lb mean change between I-C groups** | NS |

|

0.9 | NS | 0.77 | IV | Yes |

| Parker et al (2010)35 |

|

|

II | Yes | ||||

| Tucker et al (2017)55 | I: −0.23 kg/m2 mean difference TI-T2 |

|

NC | NC | III | Yes | ||

| Pre-post test studies | ||||||||

| Barnhart et al (1998)20 | +2.0 vegetable servings per week at 8 wk vs baseline | NC | II | Yes | ||||

| Davis Smith et al (2007)71 |

|

|

II | No | ||||

| Dodani and Fields (2010)25 | NS | NC | IV | Yes | ||||

| Goldfinger et al (2008)28 | −9.8 lb (at 1 y) | +0.7 FV servings/d (at 1 yr) | NS | 0.26 | 0.41 | NS | III | Yes |

| Gutierrez et al. (2014)72 | −4.38 lb (at 12 wk) | NC | II | Yes | ||||

| Ivester et al (2010)73 |

|

|

N/A | No | ||||

| Kumanyika and Charleston (1992)31 | Medication group: −6 lb No-med group: −6 lb |

|

II | No | ||||

| Martinez et al (2013)78 | +53 (mean min LTPA/wk at 6 mo) | 0.22 | IV | N/A | ||||

| McCoy et al (2017)74 | <30 min PA: +8% (of IG participants) | NC | I | No | ||||

| Oexmann et al (2001)34 |

|

|

N/A | Yes | ||||

| Peterson and Cheng (2011)36 | +140 min/wk at 6 mo post test | 0.76 | II | No | ||||

| Whisenant et al (2014)75 |

|

NC | IV | No | ||||

| Whitt-Glover et al (2008)76 |

|

|

II | Yes | ||||

| Williams et al (2015)77 | NS | NS | III | Yes | ||||

| Yeary et al (2011)56 |

|

|

|

|

IV | Yes | ||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; C, control or comparison group; cm, centimeters; CBPR, community-based participatory research; FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; FI, fruit intake; FV, fruit and vegetables; FVI, fruit and vegetable intake; I, intervention group; lb, pounds; LT, long term; LTPA, leisure time physical activity; MET, metabolic equivalent task; MPA, moderate physical activity; MVPA, moderate and/or vigorous physical activity; N/A, not available; NC, not calculated owing to insufficient information; NS, results not significant; PA, physical activity; PASE, physical activity scale for the elderly; ST, short term; VI, vegetable intake; VPA, vigorous physical activity; WC, waist circumference.

Effect sizes were corrected for the direction of outcome values so that positive effect sizes indicate improvement/risk reduction.

Cohen’s d calculation was based on the last study assessment.ccontrol.

Only results for studies in which change (pre-change to post-change and/or intervention effect) meeting a significance level of P < 0.05 are noted.

Intervention effect or comparison (ie, intervention to control group) difference meets a significance level of P < 0.05].

Dietary outcomes

Findings for diet-related outcomes are also presented in Table 2. In terms of pre-post changes for diet, most studies (n = 13) focused on servings of fruits and/or vegetables per week/day. Nine reported significant changes and the majority were designed to detect a time-series difference between intervention and control groups.20 , 22 , 23 , 28 , 37–40 , 45 All of these studies employed CBPR principles and about half were highly engaged with participating churches given their Lasater Levels of III/IV.22 , 23 , 28 , 38 Overall, of the 11 studies with diet outcomes, 9 (82%) demonstrated significant increases in fruit or vegetable intake. However, only 44% (n = 4) of the 9 successful studies were Lasater Levels III or IV.

Physical activity outcomes

Table 2 also presents findings related to those studies that measured some aspect of physical activity (n = 21). Seven studies reported nonsignificant findings, and of the 14 that found significant differences (67%), 8 studies reported significant time-series differences between the intervention and comparison groups for measurements of leisure-time physical activity. Of these 14 studies, 7 (half) had employed CBPR principles and tailoring, and 6 (42%) had high (III/IV) Lasater Levels.30 , 32 , 42 , 52 , 55 , 56 Of the 21 studies with exercise outcomes, 14 (67%) demonstrated significant increases in physical activity or steps per day. However, only 43% (n = 6) of the 14 successful studies were Lasater Levels III or IV.

Effect sizes

While the majority of studies (81%) reported significant within- or between-group differences across outcomes, effect sizes were reported or could be calculated in only 57% of cases. Of the 24 studies where effect sizes were either reported (n = 4) or were calculated (n = 20), most effect sizes were small to medium in magnitude.

DISCUSSION

This narrative review was unique in its utilization of CBPR principles and Lasater Levels as metrics by which to evaluate church-based obesity interventions. To the authors' knowledge, it is the only systematic review to identify and highlight these important components of obesity programing within faith-based settings. This review found that the majority of church-based interventions that targeted weight, diet, or physical activity outcomes employed CBPR principles throughout the development and implementation phase of the interventions. However, no straightforward relationship was found between successful study outcomes and higher Lasater Levels. While the slight majority of successful studies targeting BMI/weight/waist outcomes also had higher Lasater Levels (III or IV), this was not the case for studies targeting diet or physical activity outcomes (where the slight minority of successful studies had higher Lasater Levels). At best, this suggests that the use of trained religious organization volunteers, rather than external interventionists, for implementing outcomes may be associated with more positive weight outcomes.

Prior reviews of interventions targeting obesity, diabetes, and/or cardiovascular disease in faith-based organizations have either not considered both the delivery mechanism and the religious tailoring facets of interventions15 , 16 or have focused only on the collaborative research structure in studies involving predominantly African American samples.17 , 57 Two systematic reviews suggested only about half of faith-based health programs are delivered by external health professionals,17 , 58 and another review found 12 of 19 studies followed collaborative research approaches, but only 2 used a participatory approach where members of the faith community exerted greater control and provided input throughout program development and implementation.57 If congregation involvement can help reduce obesity-related disparities, church-based interventions need to be created within broader, sustainable partnerships than is currently exhibited in this review. Such a partnership would identify and address the barriers to collaboration and build consensus across sectors on how to best engage in these activities, as well as leverage resources from these sectors to target the sources of obesity disparities, create interventions to eliminate disparities, and develop a continual feedback loop that sustains learning within the partnership. However, partnerships are often solely funded through grants, and sustainability is often hampered as a result.59 Further, additional research could compare the efficacy of church-based health interventions that vary the level of engagement with churches. For example, studies could examine whether a church-based intervention is more likely to be sustained when engagement is high (ie, a Lasater level III or IV) than when it is low (ie, Levels I and II).

This narrative review also found church-based obesity interventions largely focus on female, older African American populations in the South, similar to a prior review that found about half of the identified studies involved African Americans and most had predominantly female participants.15 Although the focus on African Americans is critical given obesity disparities in the United States, the emphasis on female African Americans may preclude the generalizability of these studies to other vulnerable populations. For example, only 2 studies focused solely on Latinos, despite the fact that this group is also heavily burdened by obesity and obesity-related diseases60 and is also highly religious.61 Men of color also experience health disparities and are underrepresented in most public health research.62 Therefore, to fully address obesity-related disparities, it is important to include Latinos as well as men in future church-based intervention research.

Most studies intervened solely through behavioral modification at the individual person-level through educational and fitness sessions or print materials and did not address organizational or policy/environmental domains. Yet congregations provide physical infrastructure and complex social networks that can be leveraged for health promotion and services. They also provide access to informal support, food, healthcare, and educational and job opportunities through extended social networks and linkages with other community institutions.7 Minority congregations in particular are often viewed as trusted resources by their members and can help provide culturally sensitive programs to address obesity. Future church-based interventions should strive to employ a multilevel approach to move the field forward.

Of interest in this research is the comparatively large number of studies with significant findings in which effect sizes were not reported by authors and were instead calculated by research staff (57%). Also of note is that effect sizes could not be calculated in 31% of the studies with significant findings owing to insufficient information or incomplete reporting of pertinent information (such as standard errors or standard deviations). This suggests that better reporting is needed for faith-based interventions. Further, in the 68% of studies that included effect size estimates, the majority (75%) revealed small-to-medium effects, similar to a recent meta-analysis of physical activity interventions across diverse settings that found a mean effect size of 0.19.63 This raises implications regarding future church-based studies in terms of ensuring that they are sufficiently powered to detect small-to-medium effects. This may be particularly true for church-based interventions that follow the social-ecological model, since community-level interventions often have smaller effects as measured by conventional methods.64 , 65 There is also the inherent issue that individuals spend only so much of their time at church, which may further exacerbate this problem of smaller effect sizes.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first narrative review of church-based obesity interventions to comprehensively examine outcomes, intervention design, and program implementation for church-based interventions across different racial/ethnic groups. Other strengths include the use of methods approved by the Community Preventive Services Task Force, which is composed of public health and prevention experts appointed by the CDC Director, and these methods have been published in peer-reviewed journals. Quality control of the screening process was ensured by using reviewers trained in these methods specifically for this review.

Regarding limitations, this review focused only on interventions conducted in the United States. Though the focus on the USA is warranted given the stark disparities in obesity experienced by certain groups in this country, future reviews could benefit from including a more international perspective. Second, as mentioned above, among those 57% of studies in which effect sizes (Cohen’s d statistics) were calculated by research staff, unbalanced study designs, participant attrition, and incomplete information hindered this review’s ability to calculate reliable estimates in some cases. This helps explain why few studies reported effect sizes at the outset, and speaks to the methodological challenges inherent in using effect size estimates as a comparative metric by which to compare faith-based intervention studies. It also raises the question of whether traditional study metrics are sufficient or whether new metrics should be developed for research in church and similar community-based settings.

CONCLUSION

Public health professionals developing church-based interventions to address obesity need to consider the diversity among populations burdened by this condition and develop programs that are tailored to these different populations (eg, men of color, Latinos). Programs could also benefit from employing multilevel approaches to move the field away from behavioral modifications at the individual level and toward a more systems-based framework. This seems imperative if church-based interventions are to address and reverse the racial and ethnic inequalities related to obesity in the United States.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge members of the research team (Jennifer Hawes-Dawson, Eunice Wong, Margaret Whitley), the study’s Steering Committee Co-Chairs (Rev Michael A. Mata and Rev Dr Clyde W. Oden), and the Los Angeles Metropolitan Churches (LAM). They would also like to thank Roberta Shanman, RAND librarian, for her invaluable assistance with the literature review search for this publication.

Author contributions. Overall integrity of the work from inception to publication: K.R.F., D.D.P., K.P.D. Design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: KR.F., D.D.P., M.V.W., B.K., K.P., and K.P.D. Preparation and review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: K.R.F., D.D.P., K.P.D. Final approval of the version to be published: K.R.F., D.D.P., M.V.W., B.K., K.P., and K.P.D.

Funding. This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health or NIH (grant number R01HD050150 and grant number R24MD007943). Dr Payán received salary support from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (grant number T32 HS00046). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or AHRQ.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

References

- 1.May AL, Freedman D, Sherry B, et al. Obesity—United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:120–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, et al. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief. October 2017:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truong KD, Sturm R. Weight gain trends across sociodemographic groups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1602–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer PA, Penman-Aguilar A, Campbell VA, et al. Conclusion and future directions: CDC health disparities and inequalities report—United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013;62:184–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorpe RJ, Richard P, Bowie J, et al. Economic burden of men’s health disparities in the United States. Int J Men’s Health. 2013;12:195. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLeroy KR, Norton BL, Kegler MC, et al. Community-based interventions. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:529–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Black and white differences in religious participation: a multisample comparison. J Sci Study Relig. 1996;35:403–410. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Religious and spiritual involvement among older african americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: findings from the national survey of american life. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:S238–S250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooperman A, Smith GA, Cornibert SS. U.S. Public Becoming Less Religious. Pew Research Center; 2015. Available at: www.pewresearch.org.

- 10.Taylor R, Chatters L. Religion in the Lives of African Americans: Social, Psychological and Health Perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Noia J, Furst G, Park K, et al. Designing culturally sensitive dietary interventions for African Americans: review and recommendations. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:224–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venditti EM. Behavioral lifestyle interventions for the primary prevention of type 2 diabetes and translation to Hispanic/Latino communities in the United States and Mexico. Nutr Rev. 2017;75:85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, et al. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perez LG, Arredondo EM, Elder JP, et al. Evidence-based obesity treatment interventions for Latino adults in the U.S.: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:550–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maynard MJ. Faith-based institutions as venues for obesity prevention. Curr Obes Rep. 2017;6:148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancaster KJ, Carter-Edwards L, Grilo S, et al. Obesity interventions in African American faith-based organizations: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:159–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson E, Berry D, Nasir L. Weight management in African-Americans using church-based community interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc. 2009;20:59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lasater TM, Wells BL, Carleton RA, et al. The role of churches in disease prevention research studies. Public Health Rep. 1986;101:125–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnhart JM, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Nelson M, et al. An innovative, culturally-sensitive dietary intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake among African-American women: a pilot study. Top Clin Nutr. 1998;13:63–71. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boltri JM, Davis-Smith M, Okosun IS, et al. Translation of the National Institutes of Health Diabetes Prevention Program in African American churches. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:194–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen DJ, Beresford SA, Christensen CL, et al. Effects of a multilevel dietary intervention in religious organizations. Am J Health Promot. 2009;24:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1390–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell MK, Motsinger BM, Ingram A, et al. The North Carolina Black Churches United for Better Health Project: intervention and process evaluation. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodani S, Fields JZ. Implementation of the fit body and soul, a church-based life style program for diabetes prevention in high-risk African Americans. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:465–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duru OK, Sarkisian CA, Leng M, et al. Sisters in motion: a randomized controlled trial of a faith-based physical activity intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1863–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faridi Z, Shuval K, Njike VY, et al. Partners reducing effects of diabetes (PREDICT): a diabetes prevention physical activity and dietary intervention through African-American churches. Health Educ Res. 2010;25:306–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldfinger JZ, Arniella G, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. Project HEAL: peer education leads to weight loss in Harlem. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:180–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy BM, Paeratakul S, Champagne CM, et al. A pilot church-based weight loss program for African-American adults using church members as health educators: a comparison of individual and group intervention. Ethn Dis. 2005;15:373–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim KH, Linnan L, Campbell MK, et al. The WORD (wholeness, oneness, righteousness, deliverance): a faith-based weight-loss program utilizing a community-based participatory research approach. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35:634–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumanyika SK, Charleston JB. Lose weight and win: a church-based weight loss program for blood pressure control among black women. Patient Educ Couns. 1992;19:19–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martinez SM, Arredondo EM, Roesch SC. Physical activity promotion among churchgoing Latinas in San Diego, California: does neighborhood cohesion matter? J Health Psychol. 2013;18:1319–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murrock CJ, Gary FA. Culturally specific dance to reduce obesity in African American women. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:465–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oexmann MJ, Ascanio R, Egan BM. Efficacy of a church-based intervention on cardiovascular risk reduction. Ethn Dis. 2001;11:817–822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker VG, Coles C, Logan BN, et al. The LIFE project: a community-based weight loss intervention program for rural African American women. Fam Community Health. 2010;33:133–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peterson JA, Cheng AL. Heart and soul physical activity program for African American women. West J Nurs Res. 2011;33:652–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Wang T, et al. A motivational interviewing intervention to increase fruit and vegetable intake through Black churches: results of the Eat for Life trial. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1686–1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, et al. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, et al. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Health Psychol. 2005;24:339–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Resnicow K, Taylor R, Baskin M, et al. Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obes Res. 2005;13:1739–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Samuel-Hodge CD, Keyserling TC, Park S, et al. A randomized trial of a church-based diabetes self-management program for African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35:439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trost SG, Tang R, Loprinzi PD. Feasibility and efficacy of a church-based intervention to promote physical activity in children. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilcox S, Laken M, Bopp M, et al. Increasing physical activity among church members: community-based participatory research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilcox S, Laken M, Anderson T, et al. The health-e-AME faith-based physical activity initiative: description and baseline findings. Health Promot Pract. 2007;8:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winett RA, Anderson ES, Wojcik JR, et al. Guide to health: nutrition and physical activity outcomes of a group-randomized trial of an Internet-based intervention in churches. Ann Behav Med. 2007;33:251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, et al. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(suppl 1):68–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young DR, Stewart KJ. A church-based physical activity intervention for African American women. Fam Community Health. 2006;29:103–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thalheimer W, Cook S. How to calculate effect sizes from published research articles: a simplified methodology; 2002.

- 49.Cohen J. Some statistical issues in psychological research. In: Wolman BB, ed. Handbook of Clinical Psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1965:95–121. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York, NY: Routledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lasater TM, Becker DM, Hill MN, et al. Synthesis of findings and issues from religious-based cardiovascular disease prevention trials. Ann Epidemiol. 1997;7:S546–S553. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Haughton J, et al. Fe en Acción: promoting physical activity among churchgoing Latinas. Am J Public Health. 2017;107:1109–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McNabb W, Quinn M, Kerver J, et al. The PATHWAYS church-based weight loss program for urban African-American women at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sattin RW, Williams LB, Dias J, et al. Community trial of a faith-based lifestyle intervention to prevent diabetes among African-Americans. J Community Health. 2016;41:87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tucker CM, Wippold GM, Williams JL, et al. A CBPR study to test the impact of a church-based health empowerment program on health behaviors and health outcomes of black adult churchgoers. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeary KH, Cornell CE, Turner J, et al. Feasibility of an evidence-based weight loss intervention for a faith-based, rural, African American population. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A146.. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Newlin K, Dyess SM, Allard E, et al. A methodological review of faith-based health promotion literature: advancing the science to expand delivery of diabetes education to Black Americans. J Relig Health. 2012;51:1075–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, et al. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1030–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Derose KP, Hawes-Dawson J, Fox SA, et al. Dealing with diversity: recruiting churches and women for a randomized trial of mammography promotion. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:632–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abraido-Lanza AF, Echeverria SE, Flórez KR. Latino immigrants, acculturation, and health: promising new directions in research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:219–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shapiro E. Places of habits and hearts: church attendance and Latino immigrant health behaviors in the United States. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5:1328–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jones DJ, Crump AD, Lloyd JJ. Health disparities in boys and men of color. Am J Public Health 2012;102:S170–S172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR. Interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults: meta-analysis of outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:751–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Susser M. The tribulations of trials—intervention in communities. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:156–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fishbein M. Great expectations, or do we ask too much from community-level interventions? Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1075–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]