Abstract

Purpose

To assess traditional medicine practice claims by the community for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Methods

A community-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among 422 households of Jimma Zone, and the data were collected by interviewing individuals from the selected households. The medicinal plants were recorded on Microsoft excel 2010 with their parts used, dosage form, route of administration and source of plants and tabulated in the table. Descriptive statistics were used to describe and organize the data. The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) was calculated for each traditional medicine to identify the top 10 medicinal products.

Results

Around 46% of participants used traditional medicines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. The study recorded 32 herbal and non-herbal medicinal products. Garlic (RFC: 0.166), ginger (RFC: 0.133), lemon (RFC: 0.133), garden cress (RFC: 0.069) and “Damakase” (RFC: 0.031) were the frequently used herbal medicines. Seeds (47.22%) and leaves (30.56%) were the most used parts of medicinal plants. Most preparation of medicinal plants (90.63%) was administered through the oral route. The majority of medicinal plants were from home gardens.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Around half of the participants practiced traditional medicines for COVID-19. Garlic, ginger, lemon, garden cress and “Damakase” were the frequently used herbal products. Seeds and leaves were regularly used parts. The oral route is the most used route of administration. The majority of medicinal plants were from home gardens. This quantity of traditional medicine practice is probably challenging to control the pandemic. However, it might open possibilities for pharmaceutical industries and researchers to look into the effectiveness and safety of claimed medicinal products. Therefore, all responsible bodies are advocated to behave accordingly.

Keywords: traditional and complementary medicine, COVID-19, novel coronavirus, SARS-COV-2

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic originated in Wuhan, China.1 The cause for this virus is a novel coronavirus, called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is one of the known viruses of the Coronaviridae family capable of infecting humans.2 According to World Health Organization, there are over 193 million confirmed cases and over 4 million deaths. The disease is mainly transmitted through close contact with infected individuals via respiratory droplets from either sneezing or coughing.3 The virus shows various unspecific symptoms, ranging from mild to severe. Fever (98%) is the most frequent manifestation that is reported by patients, followed by cough (76%), myalgia or fatigue (44%), sputum production (28%), and headache (8%).4

Even though there are vaccines produced for COVID-19 by different manufacturing industries, people in the community and researchers are trying to find the best way to cure the disease, including herbal medicine. The world was relying on self-care practices that include the use of traditional medicine.5 Traditional medicine is gaining attention for the design and development of novel anti-infectives that might have been used in the prevention and treatment of infectious agents. Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) is a set of practices that are not fully integrated into the modern healthcare system and include herbal products, animal products, spiritual healers, yoga, and relaxation techniques.6 The practice has been used throughout the world for centuries to prevent and treat chronic and acute illnesses including, respiratory tract infections. The immunity of patients plays an essential role in COVID-19. Therefore, traditional medicines having immunomodulatory effects could be a potential candidate for preventive and treatment of COVID-19 patients.7,8

During the early stage of the disease, the community was consuming herbal medicines containing certain active substances, which have antimicrobial or antiviral, anti-inflammatory and immunostimulatory activities, such as Echinacea, Quinine, and Curcumin. These herbal compounds are assumed to modulate the immune system of patients, and they might have beneficial effects on preventing or treating COVID-19.8,9

There are limited clinical trials on the effectiveness of traditional medicines in the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. However, collecting patients views and experiences of using traditional medicine in COVID-19 is essential for future practice. Collecting data on common information queries received in community pharmacies, other medical institutions, and Internet forums will help develop evidence-based information. These interns support effective consultation and communication practices for patients.5 There are theoretical approaches suggesting ACE2 (Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2) could be one target for managing the COVID-19 infection.10 Plant extracts showed an inhibitory effect on ACE. Cerasus avium (L.) Moench, Alcea digitata (Boiss.) Alef, and Rubia tinctorum L, inhibit ACE up to 100%. Citrus aurantium L.; Berberis integerrima Bge; Peganum harmala L.; and Allium sativum L inhibit the enzyme up to 70% or more.11

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes traditional, complementary and alternative medicine of proven quality, safety, and efficacy have many benefits.12 And Africa has a long history of traditional medicine and practitioners that play a crucial role in providing care to populations.13,14 Medicinal plants such as Artemisia annua are considered as possible treatments for COVID-1915,16 And such practices need to be tested for efficacy and safety. The Zone is rich in natural flora, and there are many known traditional medicine practitioners (>115) in the study area.17 In addition, studies reported that traditional medicines practice is common in the Jimma zone.18–20 The current study aimed to assess traditional medicine practices claim by the community for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 during the pandemic and might serve as an input for pharmaceutical manufacturers and researchers for designing and developing novel agents used for the prevention and treatment of patients.

Materials and Methods

Study Setting and Period

The study was conducted in Jimma Zone, Oromia Regional State. Jimma is located 357 Km Southwest of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Currently, the Zone has 22 Woredas and two (2) self-administrative cities, and according to the 2007 Ethiopian census, the Zone had a total population of 2,486,155, of which 1,250,527 was men and the total households counted were 521,506.21 According to the Jimma Zone health bureau, 12,989 of them tested for COVID-19. Eight hundred and five (805) were confirmed to have COVID-19 cases, and 798 recovered. The study was conducted from March-April 2021.

Study Design

A community-based cross-sectional study design was employed.

Participants and Sampling Procedures

The sample size was determined by using single population proportion formula for a cross-sectional study, n=Z2P (1-P)/d2. Where P=50% (prevalence of traditional medicine practice for prevention and treatment of COVID-19), Z=1.96 (the value under the standard normal table for 95% CI), d=5% (margin of error) and the total sample size was 384. The community might be unwilling to participate because of case novelty, and we consider a 10% non-response rate. Finally, the total sample size included in the study was 422 households.

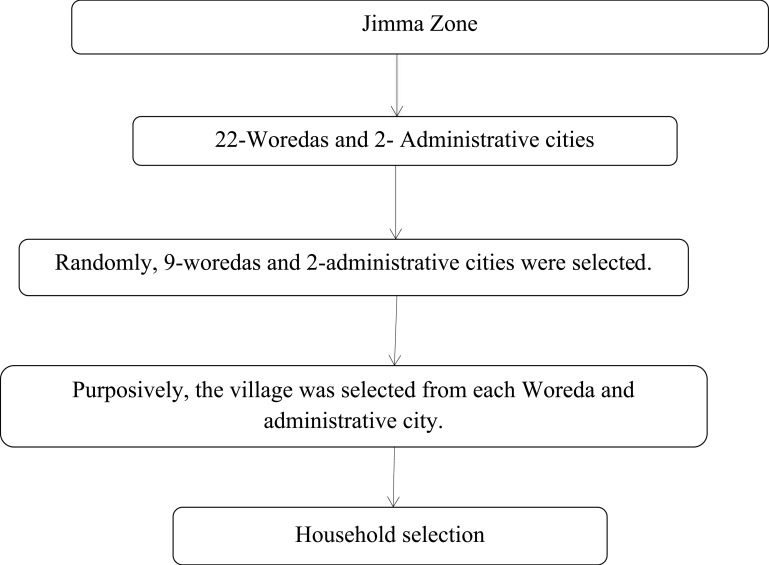

Nine Woredas and two administrative cities were selected using a lottery method. A proportional allocation was employed to obtain the required sample size for each Woreda and administrative city. A convenient sampling technique was used to select villages from each Woreda depending on data about traditional medicine practice obtained from their respective administration office. Finally, the households were selected using a systematic random sampling technique, and the first household was selected randomly from the list obtained from the included village administration office (Figure 1). Adults (> 18 years old) and living for at least six months and expressed willingness to participate were included. Priority was given for mothers and fathers, and if they are unavailable during data collection, individual older than 18 years was included. Parents who were unable to supply the required information due to any reason (mental health, incapable of communication, not willing etc.) were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Sampling framework.

Data Collection Tools and Techniques

Pretested, semi-structured interview-based questionnaires were used for the data collection. The questionnaires were adapted from previous studies conducted to assess community claims for other types of infections and modified as required.22–24,27,28 The questionnaires were prepared in English. To check the clarity and reliability of the questionnaire, a pretest was conducted on 5% of the sample size. During the process of pretest, the participants were selected randomly from the non-sampled village. The questionnaires consist of sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, religion, marital status, occupation, level of education, number of families). Traditional medicine practice for prevention and treatment of COVID-19 (do you ever used any traditional medicine for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since the outbreak? Do you agree spiritual healers can prevent and treat COVID-19? Do you agree traditional medicine practitioners can prevent and treat COVID-19 cases? Traditional medicine used if any (local name, part/s used, dosage form, route of administration, method of preparation, duration of use, frequency of use, source of the plant). The data were collected by trained data collectors (Pharmacists and Health Officers). During data collection, the data collectors maintained at least two meters (2m) distance from the respondents, and the use of a face mask and alcohol-based hand sanitizer was mandatory.

Data Processing, Analysis and Presentation

The data were entered and cleaned using Epi Info 3.1 software and exported to IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) for further analysis. Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage) were used for describing and summarizing the data.

The medicinal plants were recorded in Microsoft excel 2010 and tabulated in the table with their respective local name, families, parts used, dosage form, method of preparation, frequency of use, duration of use and source of plants. For all the traditional medicines described, Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) was calculated using equation 1.25

1

1

Where FC is the number of respondents who mentioned the plant species and N is the number of respondent participated in the study.

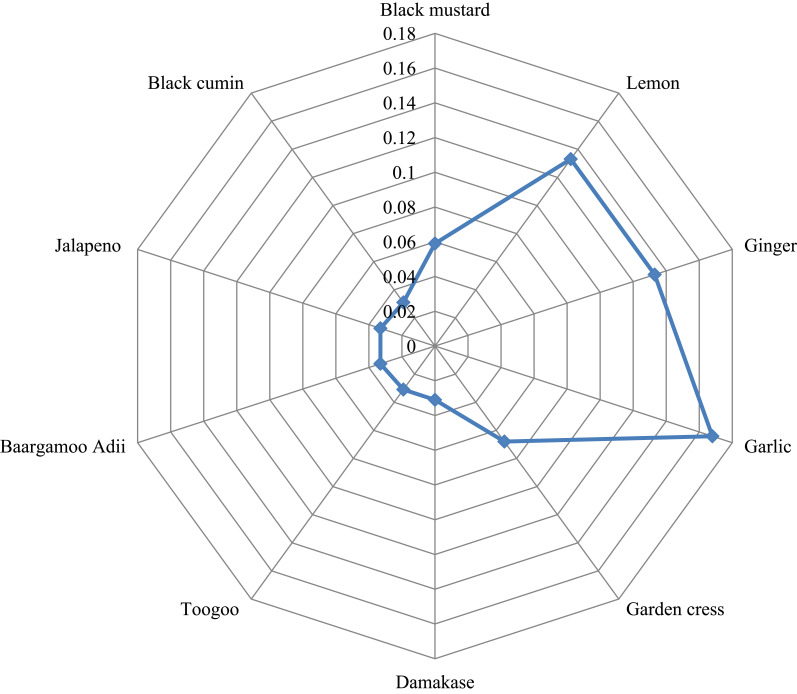

The results of the RFC and the top 10 medicinal plants used were presented in the radar diagram.

Ethical Consideration

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Jimma University (JU), Institute of Health and approved with IRBPGN/934/2020 number. The Ethical Review Committee of Jimma University accepted and approved verbal informed consent. Verbal informed consent was obtained from the participants after the purpose and methods of the study had been explained in detail. All of their responses were kept confidential and anonymous.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

More than half, 226 (53.6%) of the participants were males. The majority of 355 (84.1%) participants were married, and around 72% of the participants were followers of the Muslim religion. The age (mean ± SD) of participants was 38.49 ± 19.26. 147 (34.8%) of the participants did not have formal education, and around 39% of participants were farmers. The numbers of families living in one home (mean ± SD) were 4.61± 1.85 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 38.4905 ± 19.26 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 226 (53.6) |

| Female | 196 (46.4) |

| Religion | |

| Muslims | 307 (72.7) |

| Orthodox | 85 (20.1) |

| Protestant | 30 (7.1) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 355 (84.1) |

| Single | 50 (11.8) |

| Widowed | 14 (3.3) |

| Divorced | 3 (0.7) |

| Level of education | |

| No formal education | 147 (34.8) |

| Some primary education | 116 (27.5) |

| Completed primary education | 51 (12.1) |

| Diploma certificate | 40 (9.5) |

| Completed secondary education | 33 (7.8) |

| Bachelors | 35 (8.3) |

| Occupation | |

| Farmers | 164 (38.9) |

| Self employed | 118 (28.0) |

| Government employed | 69 (16.4) |

| Others | 71 (16.8) |

| Number of family (mean ± SD) | 4.61 ± 1.85 |

Practice of Traditional Medicine for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19

The prevalence of TM practice claims for the prevention and management of COVID-19 was 195 (46.2%). Thirty-two percent (32%) of the participants believes spiritual healers could treat COVID-19. However, only 123 (29.1%) of the participants claimed COVID-19 could be treated by traditional healers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Traditional Medicine Practice for COVID-19 in Jimma Zone During the Outbreak

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Do you ever use traditional medicine for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 since its outbreak? | |

| Yes | 195 (46.2) |

| No | 227 (53.8) |

| Do you believe that spiritual healers can treat COVID-19 cases? | |

| Yes | 135 (32.0) |

| No | 212 (50.2) |

| I do not know/not sure | 75 (17.8) |

| Do you believe that traditional healers can treat COVID-19 cases? | |

| Yes | 123 (29.1) |

| No | 192 (45.5) |

| I do not know/not sure | 107 (25.4) |

Herbal Products Claims by the Community for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19

The community claimed both herbal and non-herbal traditional medicines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19. From these: Garlic, ginger, lemon, garden cress and “Damakase” were some of them to list. The detailed description of herbal products claimed by the community is described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Detailed Description of Traditional Medicines Claimed by the Community for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19

| No. | Local/Vernacular (English Name) | Family | Part of Plant Used | Dosage Form Used | Route of Administration | Method of Preparation | Duration of Treatment | Frequency of Use/Day | RFC | Source of Plant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loomii (lemon) | Rutaceae | Juice | Liquid | Oral | The juice is mixed with cold water and drink as it is OR The juice is boiled with tea and drink it OR the drink the juice as it is | 1–14 days, 2–5 days, 2 days | Once | 0.133 | Local market |

| 2 | Jinjibla (Ginger) | Zingiberaceae | Root | Liquid | Oral | Boiled with tea and drink it before it cools OR The root part is grinded and uniformly mixed with milk and drink as it is | 7–30 days | Once | 0.133 | Home garden/market |

| 3 | Feexoo fi qullubbii adii (garlic and garden cress) | Brassicaceae, Alliaceae respectively | Seed and root, respectively | Semi-solid | Oral | The seed and root is grinded and mixed until uniformly distributed and eat as it is | 15-days | Twice | 0.007 | Home garden/ market |

| 4 | Abasuuda gurraacha (black cumin) | Ranunculaceae | Seed | Solid | Oral | The seed is grinded and eaten with food | 1-month | Once | 0.033 | Local market |

| 5 | Qullubbii adii, Feexoo fi Loomii (garlic, garden cress and lemon) | Alliaceae, Brassicaceae, Rutaceae, respectively | Root, seed and seed respectively | Liquid | Oral | The three components are grinded and mixed uniformly and eat it | 1-month | Once at night | 0.002 | Local market |

| 6 | Qullubbii adii (garlic) | Alliaceae | Root | Solid | Oral | Grinded and eaten with food OR Boiled with tea and drink it before it cools OR Eaten as it is after removing the outer part | 1 month, 3-days, respectively | Once at night | 0.168 | Local market |

| 7 | Qullubbii adii, feexoo, and qariya* (garlic, garden cress and jalapeno) | Alliaceae, Brassicaceae, Solanaceae, respectively | Bulb, seed | Semi-solid | Oral | All of the components were grinded and uniformly mixed in butter and eaten as it is | 60-days | Once | 0.002 | Home garden/market |

| 8 | Sanafic* (Black Mustard) | Brassica nigra, Brassicaceae | Seed | Semisolid | Oral | Powdered and eaten with food | 1-month | Twice | 0.059 | Local market |

| 9 | Feexoo (garden cress) | Brassicaceae | Seed | Solid | Oral | Grinded and eaten as it is OR eaten with food | 2–5 days | Once | 0.069 | Local market |

| 10 | Damakase* (Lamiaceae) | Labiatae | Leaves | Liquid | inhalation/Oral | The fresh leaves are squeezed and the juice is sniffed OR The fresh leaves are squeezed and they drink the juice | 2 days, 3–5 days | Once | 0.031 | Home garden |

| 11 | Bakkanniisa (no common English name) | Euphorbionce | Leaves | Liquid | Oral | The fresh leaves are squeezed and they drink the juice OR The leaves becomes hot by fire and the hot leaves was applied on forehead | 3–5 days, 1 days | Once | 0.012 | Home garden |

| 12 | Toogoo (no common English name) | Acanthaceae | Leaves | Liquid | Oral | The fresh leaves are squeezed and they drink the juice | 3-days | Twice | 0.033 | Forest |

| 13 | Barbare* (Ethiopian nigella seed) | Solanaceae | Seed | Solid | Oral | The seeds are grinded and eaten with food | 3-days | Three times | 0.019 | Home garden |

| 14 | Jinjibila fi qullubbii adii (ginger and garlic) | Zingiberaceae, Alliaceae respectively | Root | Liquid | Oral | Not reported | 7-days | Once | 0.002 | Home garden/market |

| 15 | Feexoo, sanafic,* qullubbii adii fi qariya* (garden cress, mustard, garlic and jalapeno) | Brassicaceae, Brassicaceae, Alliaceae, Solanaceae, respectively | Leaves | Solid | Oral | The fresh leaves are grinded and uniformly mixed together, and they eat with food and/alone | 4-days | Once | 0.002 | Home garden/market |

| 16 | Qariya* (jalapeno) | Solanaceae | Seed | As it is | Oral | Eaten with food as it is | 2–5 days | Twice | 0.021 | Home garden/market |

| 17 | Baargamoo adii fi bakkanniisa | Myrtaceae, Euphorbionce respectively | Leaves for both | Aerosol | Inhalation | The fresh leaves of the plants are boiled in water and the aerosol produced will be inhaled | 2–3 days | Once | 0.002 | Forest |

| 18 | Xosign* | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 0.002 | Market | |

| 19 | Damma daamuu (Honey) | N/A | Fresh honey | Semisolid | Oral | Drink as it is | 2–5 days | Once | 0.017 | Home garden/market |

| 20 | Baargamoo Adii | Myrtaceae | Leaves | Aerosol | Inhalation | The fresh leaves are cleaned and boiled with water and inhale it OR the fresh leaves are squeezed and inhaled as it is | 2–5 days | Twice | 0.033 | Market |

| 21 | Dhuummuugaa | Acanthaceae | Leaves | Liquid | Oral | The fresh leaves is dissolved in clean water and drink it | 2–3 days | Once | 0.005 | Forest |

| 22 | Qomonyoo | Simarobouceae | Leaves | Aerosol | Topical | “Ulachuu”@ | 2 days | Once | 0.012 | Forest |

| 23 | Amaamoo | - | Leaves | Liquid | Oral | The fresh leaves is grinded and dissolved in clean water and drink it | 2 days | Once | 0.007 | Forest |

| 24 | Tunjoo | - | Leaves | Liquid | Oral | The fresh leaves is grinded and dissolved in clean water and drink it | 3 days | Once | 0.002 | Forest |

| 25 | Araqee* (local alcohol) | N/A | Juice | Liquid | Oral | Drinking the alcohol | 1 days | Three times | 0.019 | Homemade/market |

| 26 | Muuqii/garbuu | - | Seed | Liquid | Oral | The seed is powdered and boiled with clean water and drink it | 1 day | Twice | 0.002 | Home garden/market |

| 27 | Qurunfud* (cloves) | Myrtaceae | Seed | Liquid | Oral | The seed is boiled with coffee and drink it | 1 day | Three times | 0.002 | Local market |

| 28 | Qarafa* (cinnamon) | Capsicum pepper | Leaves | Liquid | Oral | The fresh leaves is boiled with coffee and drink it | ≥ 3 days | Three times | 0.002 | Local market |

| 29 | Jimaa (khat) | Catha edulis, celastracea | Leaves | N/A | Oral | The fresh leaves is Chewed and swallow it | Daily | Once | 0.002 | Home garden/farmland |

| 30 | Siinfaa | - | Seed | Semisolid | Oral | The seed is grinded and uniformly mixed with honey and drink it | 2 weeks | Twice | 0.002 | Home garden/farmland |

| 31 | Qullubbii adii fi siinfaa | Alliaceae | Root and seed respectively | Semisolid | Oral | The root and seed part of the plant was grinded. The grinded part will be uniformly mixed with honey and drink it | 2 weeks | Once | 0.007 | Home garden |

| 32 | Abasuuda gurraacha fi qullubbii adii (black cumin and garlic) | Ranunculaceae, Alliaceae respectively | Seed, root | Semisolid | Oral | The seed and root is grinded and uniformly mixed with honey and drink it | 2 weeks | Twice | 0.002 | Home garden/farmland |

Notes: Unless otherwise indicated all of vernacular names are in Afaan Oromoo. *Amharic name. @Ulachuu is an Afaan Oromoo language, which follows the principle of mist therapy, that the patients or clients use parts of the plants after aerosolization.

Abbreviations: RFC, Relative Frequency of Citation; N/A, not applicable.

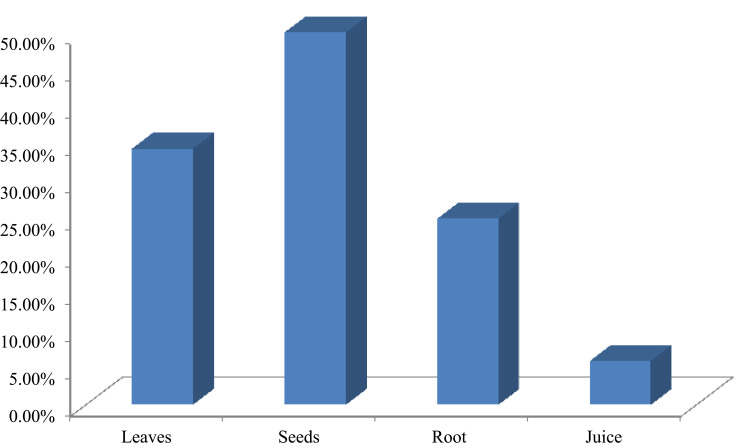

Parts of Plants Used

The most frequently used parts of medicinal plants described by the community were seeds (50.00%) followed by leaves (34.38%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Parts of medicinal plants claimed by the community for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Route of Administration

From 32 herbal and non-herbal traditional medicines (Table 3) described by the community, 29 (90.63%) prepared for oral administration in either solid/liquid dosage form (Table 4).

Table 4.

Traditional Medicines Route of Administration for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19

| Route of Administration | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Oral | 29 (90.63) |

| Inhalation | 1 (3.12) |

| Oral or inhalation | 1 (3.12) |

| Topical | 1 (3.12) |

Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) and Source of Medicinal Plants

The relative frequency of citation ranged from 0.002–0.168, and the majority of medicinal plants were from the home garden (Table 3).

Top 10 Traditional Medicines Claimed by Community for the Prevention and Treatment of COVID-19

As shown in Figure 3 of the radar plot, garlic (RFC= 0.168) was the most cited herbal medicine, followed by ginger (RFC=0.133) and lemon (RFC=O.133).

Figure 3.

Relative frequency of citation of traditional medicine claims for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Discussion

Emerging viral infections are amongst the major global community health anxieties. COVID-19 is an infectious respiratory disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Except for the development of vaccines, there is no specific drug to treat COVID-19.26

At present, traditional medicine practice for COVID-19 seems to be usual all over the world. A series of herbs are believed to be effective in relieving or treating symptoms. Many governments also formally or informally advocate or authorize the use to treat COVID-19, mainly because of its effectiveness in relieving other respiratory symptoms or popular beliefs. Traditional medicine practice in COVID-19 can reflect geography, culture, and religion,5 and this type of practice is part of Ethiopia’s healthcare systems.

According to the present study, almost half (46.2%) of the participants used traditional medicines for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 cases. The finding is higher than the telephone survey study conducted in India, where (25.8%) of participants were practicing traditional medicines. The discrepancy might be due to the study participants. As the study conducted in India only included patients in isolation centers with suspected COVID-19.27 However, the finding was comparable with the study conducted in Hong Kong; in which 44% of the participants practiced traditional medicines for prevention and treatment of COVID-19.28 Different studies claimed that traditional medicine could be a possible candidate for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.29,30 There is a report that traditionally used plant species as food can boost immunity. Therefore, might help to prevent the clinical presentation of COVID-19.31

Around one-third of the participants claim spiritual healers can treat COVID-19 cases, and 29.1% of the participants perceived traditional healers could treat COVID-19. The discrepancy between the practice of traditional medicine (46%) and the claim that traditional healers can treat the case (29%) might be due to the absence of approved drugs, inaccessibility of approved vaccines (economic component) and the absence of another choice.

The community described 32 herbal and non-herbal products used for the prevention and/treatment of COVID-19. The study conducted in Morocco identified 23 medicinal plants for the prevention of COVID-19.32 The most commonly reported parts of the herbal medicine were: seeds followed by leaves. The finding was comparable with the study conducted in Nepal33 in which leaves, seeds and fruit were the commonly used parts of medicinal plants. The oral route of administration was the frequently used route of administration by the community. Garlic, ginger and lemon were the most used herbal products. This finding is comparable with the study from Nepal in which Zingiber officinale followed by Curcuma angustifolia and Allium sativum.33

Strength of the Study

This study is the first kind in Ethiopia, and a good sample size was used for this cross-sectional study. In addition, the study was done during the pandemic area, so it catches up with the current real practice in the community.

Limitation of the Study

The study was cross-section and suffers from the drawback of the cross-sectional study design. The study did not assess the efficacy and safety profile of described traditional medicines and hence not recommended to be practiced. In addition, there might be measurement error for some variables.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Nearly half of the participants were practicing traditional medicine for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19 cases. Half of the participants did not believe spiritual healers treat COVID-19, and one-third of the participants claimed that traditional healers could treat COVID-19. Garlic, ginger, lemon, garden cress and “damakase” were the most commonly used herbal products. The most frequently used parts of the herbal products were seeds followed by leaves, and the most used route of administration was the oral route. This quantity of traditional medicine practice is probably challenging to control the pandemic. However, it might open possibilities for pharmaceutical industries and researchers to look into the effectiveness and safety of claimed medicinal products. Therefore, all responsible bodies are advocated to behave accordingly.

Future Direction

The traditional medicines were identified from indigenous knowledge of the community, and it is advised in-vitro and in-vivo tests to be conducted to assure their safety and efficacy. Identification of the active component of medicinal plants is also necessary and might be a possible lead compound for the design of an effective therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Jimma University for funding this research, the participants and data collectors.

Funding Statement

The current work was funded by the Jimma University fund for the COVID-19 special grant. The funder did not have any role in the design of the study and publication.

Data Sharing Statement

The data set used for analysis is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethical Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Jimma University Institute of Health (IRBPGN/934/2020).

Disclosure

The authors disclose no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lipsitch M, Swerdlow DL, Finelli L. Defining the epidemiology of Covid-19-studies needed. New Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1194–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2002125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nugraha RV, Ridwansyah H, Ghozali M, Khairani AF, Atik N. Traditional herbal medicine candidates as complementary treatments for COVID-19: a review of their mechanisms, pros and cons. Evidence-Based Compl Alternative Med. 2020;2020:Article ID 2560645. doi: 10.1155/2020/2560645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu Y, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(29):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paudyal V, Sun S, Hussain R, Abutaleb MH, Hedima EW. Complementary and alternative medicines use in COVID-19: a global perspective on practice, policy and research. Res Soc Administrat Pharm. 2021;S1551–7411(21)00170-4. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alzahrani AS, Price MJ, Greenfield SM, Paudyal V. Global prevalence and types of complementary and alternative medicines use amongst adults with diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;8:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang L, Liu Y. Potential interventions for novel coronavirus in China: a systematic review. J Med Virol. 2020;92(5):479–490. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma M, Anderson SA, Schoop R, Hudson JB. Induction of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines by respiratory viruses and reversal by standardized Echinacea, a potent antiviral herbal extract. Antiviral Res. 2009;83(2):165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kocaadam B, Şanlier N. Curcumin, an active component of turmeric (Curcuma longa), and its effects on health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(13):2889–2895. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1077195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ZhangáH P, Liá YZ, Slutskyá AS. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):586–590. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05985-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heidary F, Varnaseri M, Gharebaghi R. The potential use of Persian herbal medicines against COVID-19 through angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Arch Clin Infect Dis. 2020;15(COVID–19):e102838. doi: 10.5812/archcid.102838 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization. WHO traditional medicine strategy: 2014–2023. World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ezekwesili-Ofili JO, Okaka AN. Herbal medicines in African traditional medicine, herbal medicine. Philip F. Builders, Intech Open; 2019: 10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ozioma EO, Chinwe OA. Herbal medicines in African traditional medicine. Herbal Med. 2019;30(10):191–214. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orege JI, Adeyemi SB, Tiamiyu BB, Akinyemi TO, Ibrahim YA, Orege OB. Artemisia and Artemisia-based products for COVID-19 management: current state and future perspective. Adv Traditional Med. 2021;1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13596-021-00576-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haq FU, Roman M, Ahmad K, et al. Artemisia annua: trials are needed for COVID-19. Phytother Res. 2020;34:2423–2424. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suleman S, Tufa TB, Kebebe D, et al. Treatment of malaria and related symptoms using traditional herbal medicine in Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;1(213):262–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suleman S, Ketsela A, Mekonnen Z. Assessment of self-medication practices in Assendabo town, Jimma zone, southwestern Ethiopia. Res Soc Administrat Pharm. 2009;5(1):76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bekele BB, Berkesa ST, Tefera E, Kumalo A. Self-medication practice in limmu genet, Jimma zone, southwest Ethiopia: does community based health insurance scheme have an influence? J Pharmaceutics. 2018;2018:Article ID 1749137. doi: 10.1155/2018/1749137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yineger H, Yewhalaw D. Traditional medicinal plant knowledge and use by local healers in Sekoru District, Jimma Zone, Southwestern Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2007;3(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Central Statistical Authority of Ethiopia (CSA). Jimma Zone Population Survey. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistical Authority (CSA) of Ethiopia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wassie SM, Aragie LL, Taye BW, Mekonnen LB. Knowledge, attitude, and utilization of traditional medicine among the communities of Merawi town, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evidence-Based Compl Alternative Med. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/138073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gari A, Yarlagadda R, Wolde-Mariam M. Knowledge, attitude, practice, and management of traditional medicine among people of Burka Jato Kebele, West Ethiopia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(2):136. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.148782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amuamuta A, Na-Bangchang K. A review of ethnopharmacology of the commonly used antimalarial herbal agents for traditional medicine practice in Ethiopia. African J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015;9(25):615–627. doi: 10.5897/AJPP2014.4233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tardío J, Pardo-de-santayana M. Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ Bot. 2008;62(1):24–39. doi: 10.1007/s12231-007-9004-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tegen D, Dessie K, Damtie D. Candidate anti-COVID-19 medicinal plants from Ethiopia: a review of plants traditionally used to treat viral diseases. Evidence-Based Compl Alternative Med. 2021;2021:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2021/6622410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charan J, Bhardwaj P, Dutta S, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) and home remedies by COVID-19 patients: a telephonic survey. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2021;36(1):108–111. doi: 10.1007/s12291-020-00931-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam CS, Koon HK, Chung VC, Cheung YT. A public survey of traditional, complementary and integrative medicine use during the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0253890. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0253890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vellingiri B, Jayaramayya K, Iyer M, et al. COVID-19: a promising cure for the global panic. Sci Total Environ. 2020;725:138277. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rastogi S, Pandey DN, Singh RH. COVID-19 pandemic: a pragmatic plan for ayurveda intervention. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2020.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang F, Zhang Y, Tariq A, et al. Food as medicine: a possible preventive measure against coronavirus disease (COVID‐19). Phytother Res. 2020;34(12):3124–3136. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El Alami A, Fattah A, Chait A. Medicinal plants used for the prevention purposes during the covid-19 pandemic in Morocco. J Analytical Sci Appl Biotechnol. 2020;2(1):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khadka D, Dhamala MK, Li F, et al. The use of medicinal plants to prevent COVID-19 in Nepal. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2021;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13002-021-00449-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]