Abstract

To investigate the role of dipterans in the transmission of Onchocerca lupi and other zoonotic filarioids, samples were collected from different sites in Algarve, southern Portugal, morphologically identified and molecularly tested for filarioids. Culex sp. (72.8%) represented the predominant genus followed by Culicoides sp. (11.8%), Ochlerotatus sp. (9.7%), Culiseta sp. (4.5%), Aedes sp. (0.9%) and Anopheles sp. (0.3%). Nineteen (2.8%) specimens scored positive for filarioids, with Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (2%) positive for Dirofilaria immitis (1.4%), Dirofilaria repens, Acanthocheilonema reconditum, Onchocerca lupi, unidentified species of Filarioidea (0.2%, each) and Onchocercidae (0.6%). Additionally, Culiseta longiareolata (6.5%), Ochlerotatus caspius (3%) and Culex laticinctus (0.2%) scored positive for unidentified Onchocercidae, A. reconditum and for O. lupi, respectively. This is the first report of the occurrence of DNA of O. lupi, D. repens and A. reconditum in Culex spp. in Portugal. Information regarding the vectors and the pathogens they transmit may help to adopt proper prophylactic and control measures.

Keywords: Acanthocheilonema reconditum, Culex spp., Dirofilaria immitis, Dirofilaria repens, Onchocerca lupi, Portugal, Wolbachia

First report of the occurrence of the DNA of Onchocerca lupi, Dirofilaria repens and Acanthocheilonema reconditum in Culex spp. from Portugal.

Unidentified species of Filarioidea and Onchocercidae were detected in mosquitoes from Portugal.

The detection of Wolbachia supergroup E in Culex laticinctus positive for O. lupi is new to science and deserves further investigation.

Introduction

Arthropods include important vectors of pathogens, being mainly distributed and abundant in tropical and temperate regions (Schaffner et al., 2013). Among them, mosquito species belonging to several genera (e.g., Anopheles, Culex, Aedes, Ochlerotatus and Mansonia) are recognized as vectors of viruses, bacteria and filarioids causing diseases in many animal species, including humans (Otranto et al., 2013a). Similarly, biting midges (Culicoides spp.) are recognized as vectors of other filarioids (i.e., Onchocerca cervicalis, Railliet and Henry, 1910 and Onchocerca gutturosa, Neumann, 1910 of horses and cattle, respectively) (Takaoka et al., 1995). Dirofilaria immitis (Leidy, 1856), the causative agent of canine heartworm disease, is distributed in tropical and temperate regions (Otranto et al., 2013a), whereas Dirofilaria repens (Railliet and Henry, 1911), causing canine subcutaneous dirofilariosis, is present in continental and eastern European countries (Capelli et al., 2018). The majority of human cases of infection by Dirofilaria spp. are associated with D. repens in Europe and D. immitis in the Americas (Dantas‐Torres & Otranto, 2013). In addition, an increasing number of human infections caused by these filarioids have been reported in European countries (Diaz, 2015). Less studied filarioids such as Acanthocheilonema reconditum (Grassi, 1890) and Cercopithifilaria spp. are showing an increase in prevalence (up to 15.9%) among canine populations in Europe (Otranto et al., 2012). Furthermore, Onchocerca lupi (Rodonaja, 1967) has gained the interest of the scientific community as a zoonotic agent both in the USA, Europe, northern Africa and Middle East Asia (Otranto et al., 2015; Colella et al., 2018). Indeed, after the first case report of human ocular onchocercosis caused by O. lupi in Turkey (Otranto et al., 2011), up to 19 patients have been diagnosed positive for this parasite, worldwide (i.e., Germany, Tunisia, Hungary, Greece, Turkey, Iran and U.S.A.) (Berry et al., 2014; Dudley et al., 2015; Grácio et al., 2015). Though O. lupi has been previously detected in a wolf in Republic of Georgia many decades ago (Rodonaja, 1967), data on the infection in dogs and cats are limited to a few case reports from southern (Greece, Portugal, Spain) and central Europe (Germany, Hungary, Switzerland) (Otranto et al., 2013b; Grácio et al., 2015; Maia et al., 2015; Miró et al., 2016). In particular, the southern area of Portugal, Algarve region, has been spotted as one of the major foci of infection for O. lupi in canine populations and, after the first case report in 2010 (Faísca et al., 2010), up to 8.3% of infection was detected in apparently healthy dogs (Otranto et al., 2013b). Despite these prevalence data, information on the epidemiology and biological cycle of O. lupi is still minimal or lacking. Indeed, though there are reports of O. lupi putative vector (e.g., Simulium tribulatum, Lugger, 1897 in the U.S.A.) (Hassan et al., 2015), the final confirmation has not been achieved. Moreover, evidences suggest that D. repens has spread faster than D. immitis from the endemic areas of southern Europe to North, while the prevalence of seropositive humans is increasing in western and eastern Europe (Capelli et al., 2018; Fontes‐Sousa et al., 2019). In particular, D. immitis was serologically detected in humans and dogs throughout Portugal (Alho et al., 2018; Fontes‐Sousa et al., 2019), as well as, D. repens in one dog (Maia et al., 2016) from Algarve region, suggesting that Dirofilaria spp. are endemic in this country.

The current study aimed to identify the mosquito and biting midge populations present in specific sites of Algarve region and to molecularly detect filarioids they carry, in order to gain more information about their vector role in areas where O. lupi and D. immitis occur in sympatry.

Material and methods

Sample collection

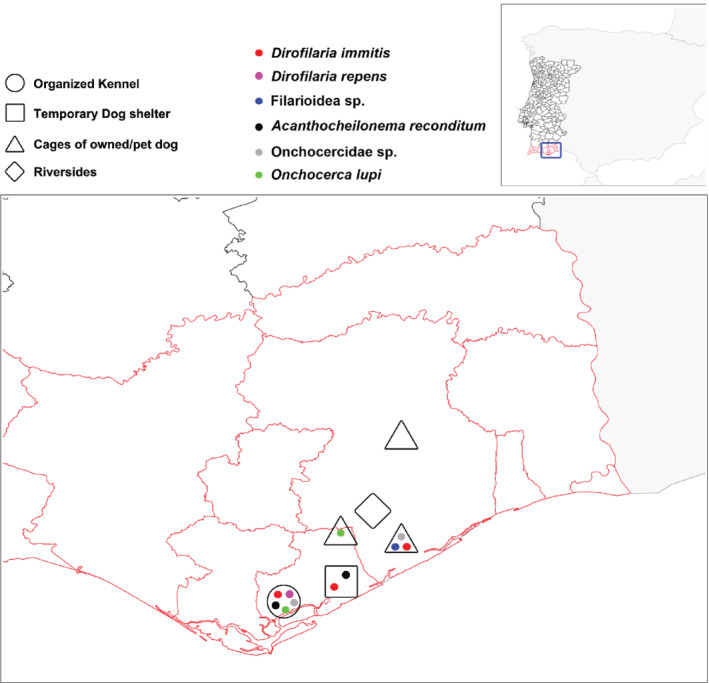

From June to August 2018, flies were collected from four different collection sites of Algarve region (southern Portugal), using CO2‐baited CDC light and BG‐sentinel‐2 mosquito traps baited with dry ice and BG lure containing ammonia, lactic acid and caproic acid (Biogents, Regensburg, Germany). Sampling areas (Fig. 1) were selected primarily based on previous history of dogs infected by O. lupi (Otranto et al., 2013b) in an organized kennel, in and around the cages of privately owned dogs (i.e., n = 3), in a temporary dog shelter, and in the riversides and near areas frequented by hunting dogs. Sampling was carried out throughout the day at weekly intervals in all six sites and the collected samples were kept at −4 °C until transferred to the laboratory. Female mosquitoes and Culicoides were identified up to genus level based on morphological keys of Ribeiro & Ramos (1999) and Mathieu et al. (2012), respectively, dissected under a stereomicroscope to find the larval stages of filarioids, and placed in single tubes containing 70% ethanol until further molecular processing.

Fig. 1.

Map of South‐East Algarve region, Portugal. Sampling sites and filarioids detected are indicated.

DNA isolation, molecular and sequencing analyses

Genomic DNA was isolated from individual female flies using GenUP gDNA Kit (Biotechrabbit, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. All samples were tested molecularly for the DNA of filarioids by conventional PCR (cPCR) using two set of primers targeting partial 12S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) genes, respectively. Each fly that tested positive for filarioid was molecularly identified using primers targeting partial cox1 gene. The source of blood meal was analysed in positive flies using the primer pairs targeting cytochrome b gene and cPCR run protocol previously described (Appendix S1). Positive dipterans were also tested for the endosymbiont, Wolbachia pipientis infection using 16S rRNA and Wolbachia surface protein (wsp) genes. All amplified PCR products were visualised in 2% agarose gel containing Gel Red® nucleic acid gel stain (VWR International PBI, Milan, Italy) and documented in Gel Logic 100 (Kodak, New York, NY, U.S.A.). The PCR products were purified and sequenced in both directions using the same primers, employing the Big Dye Terminator v.3.1 chemistry in a 3130 Genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, U.S.A.) in an automated sequencer (ABI‐PRISM 377). Nucleotide (nt) sequences were edited, aligned and analysed using BioEdit and compared with available sequences in the GenBank using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST; http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). All specimens were also screened for the DNA of O. lupi using quantitative real‐time PCR (qPCR) assay and run protocol described elsewhere. The details of the primers used in the current study are given in supplementary file (Appendix S1).

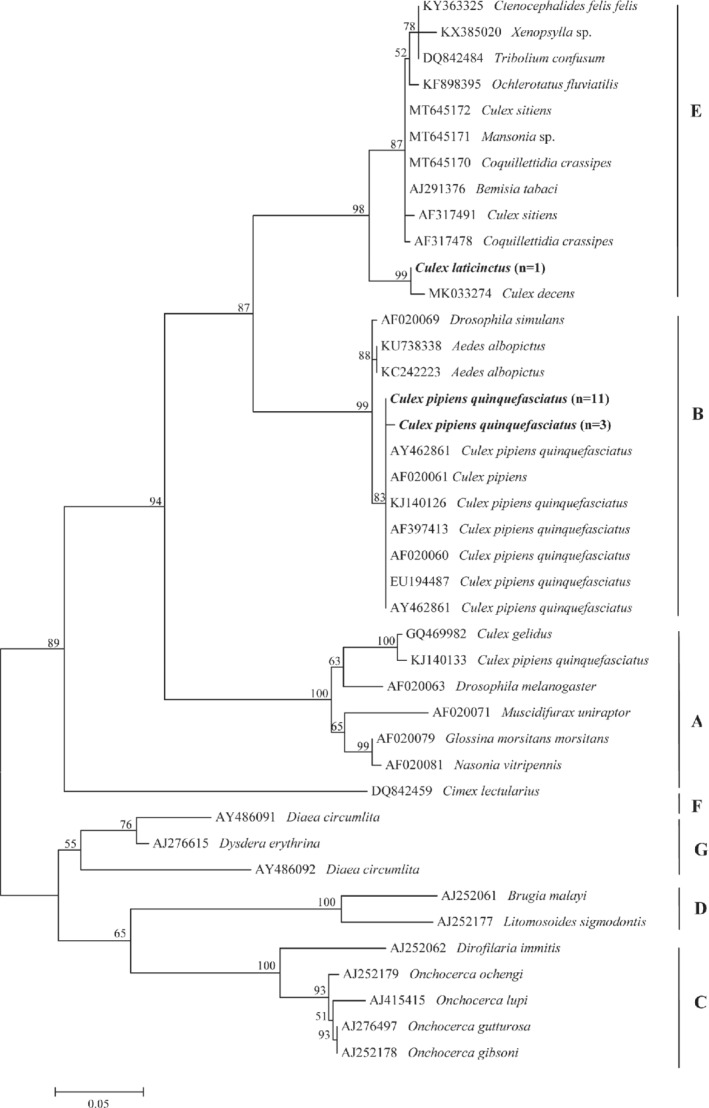

Phylogenetic analysis

Representative sequences of the 12S rRNA and cox1 genes of filarioids and wsp gene of W. pipientis were included along with the sequences available in the GenBank database for phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic relationships were inferred using Maximum Likelihood (ML) method based on General Time Reversible model (Nei & Kumar, 2000) with discrete Gamma distribution (+G + I) to model evolutionary rate differences among sites for cox1, Hasegawa‐Kishino‐Yano and Tamura 3‐parameter models with +G for 12S rRNA and for wsp genes, respectively (Hasegawa et al., 1985; Tamura, 1992; Kumar et al., 2018), selected by best‐fit model (Nei & Kumar, 2000). Evolutionary analyses were conducted on 1000 bootstrap replications using the MEGA X software (Tamura et al., 2013). Homologous sequences from Filaria martis and Thelazia callipaeda were used as outgroups (cox1: AM042552, AJ544880; 12SrRNA: AJ544858).

Statistical analysis

Prevalence of filarioid infection among flies (proportion of insects infected by larval stages of different filarioid species on the total population of insects collected from different location of Portugal) was assessed. Statistical analysis was done using StatLib software. Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI) were established for proportions.

Results

The most prevalent species of dipteran collected belonged to the genus Culex (n = 501, 72.8%), followed by Culicoides (n = 81, 11.8%), Ochlerotatus (n = 67, 9.7%), Culiseta (n = 31, 4.5%), Aedes (n = 6, 0.9%) and Anopheles (n = 2, 0.3%). Of the 688 specimens collected, the highest number was from cages of privately owned dogs (45.5%) (Table 1), whereas the highest prevalence of filarioid infection (3.2%) was recorded in mosquitoes collected from organised kennel (Table 2). Only one mosquito scored positive by a larva of D. immitis after dissection. Nineteen mosquito specimens (2.8%; 95% CI: 1.7–4.3) scored molecularly positive for filarioids, without coinfections and with Culex spp. as the most prevalent infected genus (2.2%; 95% CI: 1.3–3.6). At the molecular detection, 14 specimens of Culex pipiens quinquefasciatus (Say, 1823; 100% nt identity with MK575480) scored positive for D. immitis (n = 7, 1.4%; 95% CI: 0.6–2.9), Onchocercidae (n = 3, 0.6%; 95% CI: 0.2–1.8), O. lupi, D. repens, A. reconditum and Filarioidea (n = 1, 0.2%, each; 95% CI: 0.02–1.1) by cPCR (Table 2). Moreover, Culex laticinctus (Edwards, 1913; 95.01% nt identity with MT993489), Ochlerotatus caspius (Pallas, 1771; 99.62% nt identity with MT993477) and Culiseta longiareolata (Macquart, 1838; 100% nt identity with MT993479) scored positive for O. lupi (n = 1, 0.2%; 95% CI: 0.02–1.1), A. reconditum (n = 2, 3%; 95% CI: 0.5–10.2) or for Onchocercidae (n = 2, 6.5%; 95% CI: 1.2–20.7), respectively (Table 2). None of the Anopheles spp. (n = 2), Aedes spp. (n = 6) and Culicoides spp. (n = 81) scored positive (data not shown). Wolbachia pipientis (Hertig, 1936) was only detected in 15 filarioid‐infected Culex spp.. Detection by qPCR confirmed the positivity of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus and of Cx. laticinctus for O. lupi. Of the 19 positive mosquitoes, 6 scored positive for the host blood meal, with two Oc. caspius positive for dog and human, two Cs. longiareolata for avian and two Cx. p. quinquefasciatus for human (Appendix S2). Blast analyses of all sequences of D. immitis, D. repens, O. lupi and A. reconditum displayed a nt identity of 100% with those available in GenBank database for both genes examined (12SrRNA: KF707482, KX265091, KC686903, MT252013; cox1: MN945948, MT012806, KX853327; JF461456). An identity ranging from 96.3 to 98.3% was obtained for 12S rRNA sequences of Onchocercidae and Filarioidea (KR676614, JX870434) and from 98.9 to 99.1% for cox1 sequences of Filarioidea (LC107819). All Culicoides spp. scored negative for filarioids. The wsp sequences of W. pipientis detected in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus showed a nt identity from 99.5% to 100% with that available from GenBank (MH218812) with the exclusion of that found in Cx. laticinctus, which showed a nt identity of 99.3% with that of Culex decens (Theobald, 1901; MK033274).

Table 1.

Number and percentage of genera of dipterans collected from Algarve region, Portugal, divided according to the genus and sampling site of collection.

| Description of sampling sites | Culex Tot (%) | Ochlerotatus Tot (%) | Aedes Tot (%) | Culiseta Tot (%) | Anopheles Tot (%) | Culicoides Tot (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organized kennel (n = 1) | 270 (95.4) | 9 (3.2) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | — | — | 283 (41.1) |

| Temporary dog shelter (n = 1) | 14 (18.2) | 55 (71.4) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (1.3) | — | 5 (6.5) | 77 (11.2) |

| Cages of owned/pet dog (n = 3) | 203 (64.9) | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 29 (9.3) | 2 (0.6) | 76 (24.3) | 313 (45.5) |

| Riversides (n = 1) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | — | — | — | — | 15 (2.2) |

| Total | 501 (72.8) | 67 (9.7) | 6 (0.9) | 31 (4.5) | 2 (0.3) | 81 (11.8) | 688 |

Table 2.

Number (positive/total) and prevalence (%) of filarioids in dipterans divided according to sampling sites from Algarve region, Portugal.

| Culex (n = 501) | Ochlerotatus (n = 67) | Culiseta (n = 31) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sampling site | D. immitis | D. repens | A. reconditum | O. lupi | Onchocercidae sp. | Filaroidea sp. | A. reconditum | Onchocercidae sp. |

| Organized kennel (n = 1) | 4/270 (1.5) | 1/270 (0.4) | 1/270 (0.4) | 1/270 (0.4) | 1/270 (0.4) | 0/270 | 1†/9 (11.1) | 0/1 |

| Temporary dog shelter (n = 1) | 1/14 (7.1) | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 1†/55 (1.8) | 0/1 |

| Cages of owned/pet dog (n = 3) | 2/203 (1.0) | 0/203 | 0/203 | 1*/203 (0.5) | 2/203 (1.0) | 1/203 (0.5) | 0/2 | 2‡/29 (6.9) |

| Riversides (n = 1) | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/14 | 0/1 | — |

Culex laticinctus.

Ocharotatus caspius.

Culiseta longiareolata; Positive specimens of Culex without asterisk belongs to Culex pipiens quinquiefasciatus. None of the Anopheles sp. (n = 2), Aedes sp. (n = 6) Culicoides sp. (n = 81) scored positive.

Mosquitoes molecularly identified were indicated with the following symbols.

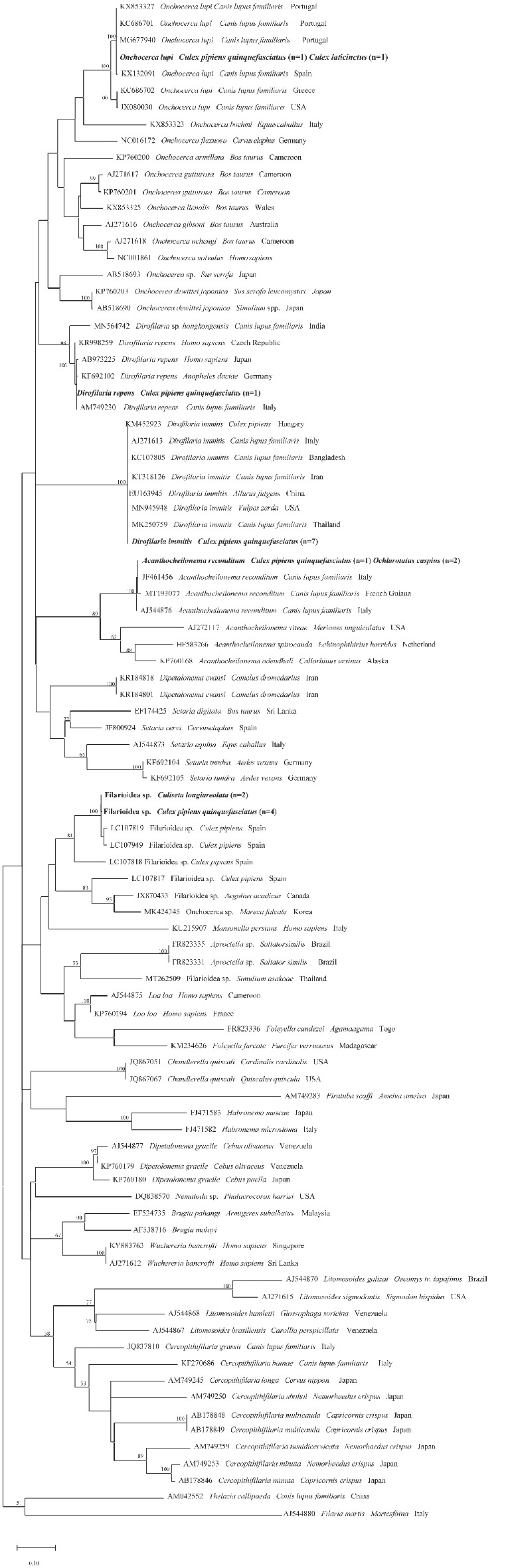

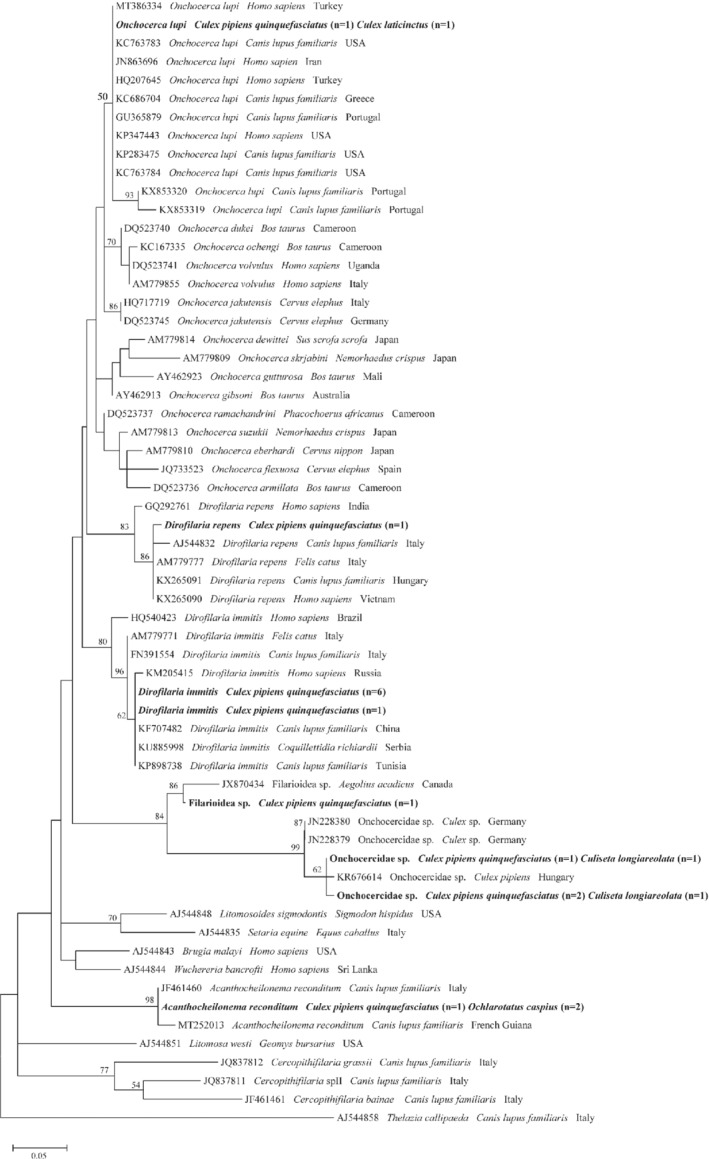

Phylogenetic analyses support molecular identification by clustering all the representative sequences of D. immitis, D. repens, O. lupi and A. reconditum in the corresponding species clades supported by high bootstrap value for cox1 and 12S rRNA trees (Figs 2 and 3). In particular, both 12S rRNA and of cox1 phylogenetic dendrograms clustered sequences of unidentified Onchocercidae and Filarioidea within the clades of the same species, respectively, and those of O. lupi within a species‐specific clade which includes reference sequences from Portugal and Spain, and as a sister clade which includes sequences of O. lupi, with the exclusion of other Onchocerca species (Figs 2 and 3).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationship of filarioids detected in this study (in bold) and other filarioids available from GenBank based on cytochrome c oxidase sequences. Evolutionary analysis was conducted on 1000 bootstrap replications using Maximum Likelihood method and General Time Reversible model. Filaria martis was used as outgroup. GenBank accession number, host species and country of origin are indicated.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of filarioids detected in this study (in bold) and other filarioids available from GenBank based on a partial sequence of the 12S rRNA gene. Evolutionary analysis was conducted on 1000 bootstrap replications using Maximum Likelihood method and Hasegawa‐Kishino‐Yano model. Thelazia callipaeda was used as outgroup. GenBank accession number, host species and country of origin are indicated.

Similarly, the ML analyses of Wolbachia sequences yielded strict consensus in overlapping the topology of trees obtained from wsp (Fig. 4) and 16S rRNA (data not shown) genes, with a strong bootstrap value (up to 99%) for each clade (Fig. 4). All representative sequences of Wolbachia detected in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus clustered in the same clade of the reference Wolbachia sequences that belong to supergroup B, excluding the monophyletic clade which grouped the sequences found in Cx. laticinctus with those of the reference supergroup E (Fig. 4). Representative sequences of all filarioids and Wolbachia were deposited in GenBank (Accession numbers: MW242746–48, MW243588, MW254895‐901, MW435608‐14; Appendix S3).

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic relationship of Wolbachia detected in this study (in bold) and other available from GenBank belonging to different supergroups based on a partial sequence of the Wolbachia surface protein (wsp). Evolutionary analysis was conducted on 1000 bootstrap replications using Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura 3‐parameter model. GenBank accession number and host species are indicated.

Discussion

This study assessed the presence of filarioids in dipterans collected from specific sites in Algarve region, southern Portugal. In particular, DNA of O. lupi was detected for the first time in mosquito specimens belonging to Culex genus, as well as that of D. repens in the same mosquito genus, in this country. The predominance of Culex spp. (72.8%) herein collected was supported by previous data where a high prevalence of mosquito species belonging to this genus (i.e., Cx. pipiens, 52% and Culex theileri, Theobald, 1903, 29%) was reported (Freitas et al., 2012). The finding of different dipteran genera, such as Culex, Ochlerotatus, Aedes, Culiseta, Anopheles and Culicoides, may be due to the favourable climatic conditions recorded in the Algarve province. For example, variation in relative abundance and species diversity (i.e., Oc. caspius Cx. pipiens and Anopheles atroparvus, Van Thiel, 1927) has been observed from season to season and every year in the above mentioned region (Freitas et al., 2012; Osório et al., 2014; Silva et al., 2019). Indeed, the presence of wetlands and lagoons, used by migratory birds, can favour the abundance and diversity in mosquito species populations, which may perpetuate the biological cycle of pathogens and/or potentially transmit them (Freitas et al., 2012).

The most prevalent filarioid detected in the current study was D. immits (1%) found in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus. This species was previously reported in Algarve with an overall mean prevalence of 12% in canine populations in the mainland Portugal (e.g., prevalence rates of 16.7% in Ribatejo, 16.5% in Alentejo, 30% in Madeira 6.8% in Aveiro and 8.8% in Coimbra) (Alho et al., 2018). Despite the known endemicity of D. immitis in dogs from Portugal, Cx. theileri was the only species found to be infected with this filarioid (Ferreira et al., 2015). In addition, other mosquito species (e.g., Culex pipiens, Linnaeus, 1758; Anopheles maculipennis sensu lato, Meigen 1818; A. atroparvus, Ae. caspius and Aedes detritus sensu lato, Haliday, 1833) have been found positive for DNA of D. immitis in Portugal and thus have been suggested as potential vectors (Ferreira et al., 2017). Therefore, the molecular detection also of D. repens in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus, indicates that this mosquito species may be involved in the transmission of both Dirofilaria species. Though D. repens microfilariae (mfs) were diagnosed in a dog from the western part of Algarve region (Maia et al., 2016; Capelli et al., 2018), this filarioid has never been found in any mosquito collected in Portugal (Ferreira et al., 2015; Ferreira et al., 2017).

The same mosquito species, Cx. p. quinquefasciatus, as well as Oc. caspius was molecularly positive for A. reconditum (prevalence of infection 0.2 and 3%, respectively). Detection of A. reconditum DNA in both mosquito species above mentioned was unexpected as fleas and lice are the known vectors for this filarioid (Brianti et al., 2012). Accordingly, A. reconditum could have been acquired by mosquitoes while feeding on infected dogs, as suggested by the positivity of the same specimens for blood of dogs. Indeed, though xenomonitoring may be sensitive in detecting filarioids in insects, positive results for parasite DNA do not imply the role of them as vectors of the same pathogens, since larval stages can be detected up to 2 weeks after the meal with blood circulating mfs (Fischer et al., 2007). In addition, data above represent confirmatory evidence for the circulation of A. reconditum among canine populations from Portugal, with an estimated prevalence of the infection up to 0.8% (Ferreira et al., 2017).

The molecular detection in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus and Cs. longiareolata of unidentified filarioids, phylogenetically close to Onchocercidae and Filarioidea found in birds from Germany (Czajka et al., 2012) and Hungary (Kemenesi et al., 2015) could be due to the ornithophilic attitude of these mosquito species (Rizzoli et al., 2015). This hypothesis is also supported by the detection of common black bird (Turdus merula) DNA, in the blood meal of Cs. longiareolata, which suggests that this mosquito species may acquire mfs while feeding on birds.

On the other hand, the detection of human blood DNA in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus may be explained by the presence of two ecoforms within the Cx. pipiens complex, which occur in sympatry in Portugal (Gomes et al., 2009). Hence, the mosquito belonging to Cx. pipiens complex had a shift in the feeding preferences from ornithophilic (pipiens) to mammalophilic (molestus) and thus acquired the ability to feed on both hosts (Gomes et al., 2009). The plasticity of Cx. p. quinquefasciatus host preference has been previously described, indicating that this species of mosquito can act as a bridge vector for pathogens biting humans and other mammals and birds (Farajollahi et al., 2011).

Detection of the DNA of O. lupi in Cx. p. quinquefasciatus and Cx. laticinctus suggests the potential implication of mosquitoes belonging to genus Culex in the transmission of this filarioid. Though this result does not imply any evidence of their role as vectors for this filarial species, the recent findings of Onchocerca sp. larvae from the sand fly Psychodopygus carrerai carrerai (Brilhante et al., 2020) suggests that insect species, other than simuliids, may acquire mfs of this onchocercid. Though Onchocerca sp. are known to be vectored by Simulium sp. and Culicoides sp. through cutting or chewing mouth parts (telmophagy/pool feeding), it is demonstrated that other blood‐feeding insects (e.g., Aedes aegypti mosquito) may obtain blood also by lacerating vessels and not only directly from vessels (Gordon & Lumsden, 1939). Therefore, mosquitoes may acquire the pathogen while feeding, by piercing mouth parts (solenophagy/tube feeding) and ingest mfs of O. lupi in subcutaneous connective tissue. While the potential role of black flies in the transmission of O. lupi in dogs and humans has been hypothesized, no convincing scientific evidence in this regard has yet been produced (Otranto et al., 2013a). To date, vector tracking of this filarioid is limited to the detection of the DNA of O. lupi in S. tribulatum in the USA (Hassan et al., 2015) and to the presence of Simulium reptans in areas where the cases of canine ocular onchocerciasis have been reported (i.e., Switzerland, Germany and Hungary) (Otranto et al., 2013a).

Findings of Wolbachia supergroup B in Cx. p. quinquefascaitus confirms previous reports in this vector species (Werren et al., 2008), whereas the detection of Wolbachia supergroup E in Cx. laticinctus positive for O. lupi is new to science and it needs further investigation. In the same line of reason, implications of this Wolbachia supergroup in the vector capacity of this mosquito species needs further research. Indeed, it is known that Wolbachia symbionts are able to manipulate the reproductive system of many invertebrate hosts increasing or decreasing host fitness for the developing pathogens in them (Zug & Hammerstein, 2015). Furthermore, a mutualistic symbiosis has been described between Wolbachia and Onchocercidae, which contribute to the reproduction of filariae (Casiraghi et al., 2004).

Conclusion

Detection of the DNA of O. lupi as well as of D. repens in Culex spp. for the first time in Portugal needs further investigations to understand their vector capacity and competence to transmit these zoonotic parasites to animals and humans in Portugal. Algarve is a touristic place offering a wide range of outdoor activities (ie., bird watching, fishery and aquaculture) that may facilitate the spread of filarioids vectored by dipteran species. Thus, information regarding the vectors and their transmitting pathogens may help to standardise an adequate prophylactic approach and proper vector control measures to effectively control the above zoonotic filarioids.

Authors' contributions

Sample collection: Maria Alfonsa Cavalera; Carla Maia; Conceptualization: Ranju R.S. Manoj, Maria Stefania Latrofa, Domenico Otranto; Supervision: Maria Stefania Latrofa, Domenico Otranto; Methodology: Ranju R.S. Manoj, Maria Stefania Latrofa; Investigation: Ranju R.S. Manoj, Maria Stefania Latrofa; Maria Alfonsa Cavalera; Data curation: Ranju R.S. Manoj, Maria Stefania Latrofa; Writing ‐ original draft: Ranju R.S. Manoj, Maria Stefania Latrofa; Writing ‐ review & editing: Ranju R.S. Manoj, Maria Stefania Latrofa, Domenico Otranto, Maria Alfonsa Cavalera, Jairo Alfonso Mendoza‐Roldan, Carla Maia. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Primers used for the study

Appendix S2. Details of the blood meal analysis of positive flies

Appendix S3. Gene Bank accession numbers of the representative sequences of filarioids and Wolbachia identified in the current study

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Viet‐Linh Nguyen (Department of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Bari, Italy) for his help in preparing the site map of the current study area and Giada Annoscia (Department of Veterinary Medicine of the University of Bari, Italy) for the lab assistance. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ranju Ravindran Santhakumari Manoj and Maria Stefania Latrofa contributed equally.

Data availability statement

Data obtained from the results of this manuscript are included within the article. The raw data set used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Abbasi, I., Cunio, R. & Warburg, A. (2009) Identification of blood meals imbibed by phlebotomine sand flies using cytochrome b PCR and reverse line blotting. Vector‐Borne and Zoonotic Diseases, 9, 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alho, A.M., Meireles, J., Schnyder, M.et al. (2018) Dirofilaria immitis and Angiostrongylus vasorum: the current situation of two major canine heartworms in Portugal. Veterinary Parasitology, 252, 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry, R., Stepenaske, S., Dehority, W.A.M., Nmathison, B. & Bishop, H. (2014, November) Zoonotic Onchocerca lupi presenting as a subcutaneous nodule in a 10‐year‐old girl: report of the second case in the United States and a review of the literature. In Abstract Book of ASDP Annual Meeting.

- Brianti, E., Gaglio, G., Napoli, E.et al. (2012) New insights into the ecology and biology of Acanthocheilonema reconditum (Grassi, 1889) causing canine subcutaneous filariosis. Parasitology, 139, 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilhante, A.F., de Albuquerque, A.L., de Brito Rocha, A.C.et al. (2020) First report of an Onchocercidae worm infecting Psychodopygus carrerai carrerai sandfly, a putative vector of Leishmania braziliensis in the Amazon. Scientific Reports, 10, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capelli, G., Genchi, C., Baneth, G.et al. (2018) Recent advances on Dirofilaria repens in dogs and humans in Europe. Parasites & Vectors, 11, 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiraghi, M., Bain, O., Guerrero, R.et al. (2004) Mapping the presence of Wolbachia pipientis on the phylogeny of filarial nematodes: evidence for symbiont loss during evolution. International Journal for Parasitology, 34, 191–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colella, V., Lia, R.P., Di Paola, G., Cortes, H., Cardoso, L. & Otranto, D. (2018) International dog travelling and risk for zoonotic Onchocerca lupi . Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, 65, 1107–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czajka, C., Becker, N., Poppert, S., Jöst, H., Schmidt‐Chanasit, J. & Krüger, A. (2012) Molecular detection of Setaria tundra (Nematoda: Filarioidea) and an unidentified filarial species in mosquitoes in Germany. Parasites & Vectors, 5, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantas‐Torres, F. & Otranto, D. (2013) Dirofilariosis in the Americas: a more virulent Dirofilaria immitis? Parasites & Vectors, 6, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, J.H. (2015) Increasing risks of human dirofilariasis in travellers. Journal of Travel Medicine, 22, 116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, R.W., Smith, C., Dishop, M., Mirsky, D., Handler, M.H. & Rao, S. (2015) A cervical spine mass caused by Onchocerca lupi . The Lancet, 386, 1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faísca, P., Morales‐Hojas, R., Alves, M.et al. (2010) A case of canine ocular onchocercosis in Portugal. Veterinary Ophthalmology, 13, 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farajollahi, A., Fonseca, D.M., Kramer, L.D. & Kilpatrick, A.M. (2011) “Bird biting” mosquitoes and human disease: a review of the role of Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in epidemiology. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 11, 1577–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C.A.C., de Pinho Mixão, V., Novo, M.T.L.M.et al. (2015) First molecular identification of mosquito vectors of Dirofilaria immitis in continental Portugal. Parasites & Vectors, 8, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C., Afonso, A., Calado, M.et al. (2017) Molecular characterization of Dirofilaria spp. circulating in Portugal. Parasites & Vectors, 10, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, P., Erickson, S.M., Fischer, K.et al. (2007) Persistence of Brugia malayi DNA in vector and non‐vector mosquitoes: implications for xenomonitoring and transmission monitoring of lymphatic filariasis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 76, 502–507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontes‐Sousa, A.P., Silvestre‐Ferreira, A.C., Carretón, E.et al. (2019) Exposure of humans to the zoonotic nematode Dirofilaria immitis in Northern Portugal. Epidemiology & Infection, 147, e282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, F.B., Novo, M.T.L.M., Esteves, A.S. & Almeida, A. (2012) Species composition and WNV screening of mosquitoes from lagoons in a wetland area of the Algarve, Portugal. Frontiers in Physiology, 2, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, B., Sousa, C.A., Novo, M.T.et al. (2009) Asymmetric introgression between sympatric molestus and pipiens forms of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Comporta region, Portugal. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 9, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, R.M. & Lumsden, W.H.R. (1939) A study of the behaviour of the mouth‐parts of mosquitoes when taking up blood from living tissue; together with some observations on the ingestion of microfilariae. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology, 33, 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- Grácio, A.J.S., Richter, J., Komnenou, A.T. & Grácio, M.A. (2015) Onchocerciasis caused by Onchocerca lupi: an emerging zoonotic infection. Systematic review. Parasitology Research, 114, 2401–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, M., Kishino, H. & Yano, T.A. (1985) Dating of the human‐ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 22, 160–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, H.K., Bolcen, S., Kubofcik, J.et al. (2015) Isolation of Onchocerca lupi in dogs and black flies, California, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21, 789–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemenesi, G., Kurucz, K., Kepner, A.et al. (2015) Circulation of Dirofilaria repens, Setaria tundra, and Onchocercidae species in Hungary during the period 2011–2013. Veterinary Parasitology, 214, 108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.P., Rajavel, A.R., Natarajan, R. & Jambulingam, P. (2007) DNA barcodes can distinguish species of Indian mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 44, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. (2018) MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 35, 1547–1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latrofa, M.S., Annoscia, G., Colella, V.et al. (2018) A real‐time PCR tool for the surveillance of zoonotic Onchocerca lupi in dogs, cats and potential vectors. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 12, e0006402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia, C., Annoscia, G., Latrofa, M.S.et al. (2015) Onchocerca lupi nematode in cat, Portugal. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21, 2252–2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia, C., Lorentz, S., Cardoso, L., Otranto, D. & Naucke, T.J. (2016) Detection of Dirofilaria repens microfilariae in a dog from Portugal. Parasitology Research, 115, 441–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A.R., Brown, G.K., Dunstan, R.H. & Roberts, T.K. (2005) Anaplasma platys: an improved PCR for its detection in dogs. Experimental Parasitology, 109, 176–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, B., Cêtre‐Sossah, C., Garros, C.et al. (2012) Development and validation of IIKC: an interactive identification key for Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) females from the Western Palaearctic region. Parasites & Vectors, 5, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miró, G., Montoya, A., Checa, R.et al. (2016) First detection of Onchocerca lupi infection in dogs in southern Spain. Parasites & Vectors, 9, 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei, M. & Kumar, S. (2000) Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osório, H.C., Zé‐Zé, L., Amaro, F. & Alves, M.J. (2014) Mosquito surveillance for prevention and control of emerging mosquito‐borne diseases in Portugal—2008–2014. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 11583–11596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto, D., Traversa, D., Guida, B., Tarsitano, E., Fiorente, P. & Stevens, J.R. (2003) Molecular characterization of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I gene of Oestridae species causing obligate myiasis. Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 17, 307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto, D., Sakru, N., Testini, G.et al. (2011) First evidence of human zoonotic infection by Onchocerca lupi (Spirurida, Onchocercidae). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 84, 55–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto, D., Brianti, E., Latrofa, M.S.et al. (2012) On a Cercopithifilaria sp. transmitted by Rhipicephalus sanguineus: a neglected, but widespread filarioid of dogs. Parasites & Vectors, 5, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto, D., Dantas‐Torres, F., Brianti, E.et al. (2013a) Vector‐borne helminths of dogs and humans in Europe. Parasites & Vectors, 6, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto, D., Dantas‐Torres, F., Giannelli, A.et al. (2013b) Zoonotic Onchocerca lupi infection in dogs, Greece and Portugal, 2011–2012. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 19, 2000–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otranto, D., Giannelli, A., Latrofa, M.S.et al. (2015) Canine infections with Onchocerca lupi nematodes, United States, 2011–2014. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 21, 868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, H., & Ramos, H.C. (1999) Identification keys of the mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) of continental Portugal, Açores and Madeira. European Mosquito Bulletin (United Kingdom).

- Rizzoli, A., Bolzoni, L., Chadwick, E.A.et al. (2015) Understanding West Nile virus ecology in Europe: Culex pipiens host feeding preference in a hotspot of virus emergence. Parasites & Vectors, 8, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodonaja, T.E. (1967) A new species of nematode, Onchocerca lupi n. sp., from Canis lupus cubanensis. Soobshchenyia Akad . Nauk Gruzinskoy SSR, 45, 715–719. [Google Scholar]

- Schaffner, F., Medlock, J.M. & Van Bortel, A.W. (2013) Public health significance of invasive mosquitoes in Europe. Clinical Microbiology Infection, 19, 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M., Morais, P., Maia, C., de Sousa, C.B., de Almeida, A.P.G. & Parreira, R. (2019) A diverse assemblage of RNA and DNA viruses found in mosquitoes collected in southern Portugal. Virus Research, 274, 769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka, H., Aoki, C., Bain, O., Ogata, K. & Baba, M. (1995) Investigation of Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in relation to the transmission of bovine Onchocerca and other filariae in Central Kyushu, Japan. Parasite (Paris, France), 2, 367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K. (1992) Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions when there are strong transition‐transversion and G+ C‐content biases. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 9, 678–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 30, 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werren, J.H., Baldo, L. & Clark, M.E. (2008) Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 6, 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W., Rousset, F. & O'Neill, S. (1998) Phylogeny and PCR–based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 265, 509–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zug, R. & Hammerstein, P. (2015) Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biological Reviews, 90, 89–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Primers used for the study

Appendix S2. Details of the blood meal analysis of positive flies

Appendix S3. Gene Bank accession numbers of the representative sequences of filarioids and Wolbachia identified in the current study

Data Availability Statement

Data obtained from the results of this manuscript are included within the article. The raw data set used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.