Abstract

Objective

The increased prevalence of metabolic dyslipidemia (MD) and its association with a variety of disorders raised a lot of attention to its management. Caveolin 1 (CAV1) the key protein in the caval structure of plasma membranes is many cell types that play an important role in its function. (CAV1) is a known gene associated with obesity. Today, a novel diet recognized as the Mediterranean and Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet (MIND) is reported to have a positive effect on overall health. Hence, we aimed to investigate the interactions between CAV1 polymorphism and MIND diet on the MD in overweight and obese patients.

Results

Remarkably, there was a significant interaction between the MIND diet and CAV1 rs3807992 for dyslipidemia (β = − 0.25 ± 132, P = 0.05) in the crude model. Whereby, subjects with dominant alleles had a lower risk of dyslipidemia and risk allele carriers with higher adherence to the MIND diet may exhibit the lower dyslipidemia. This study presented the CAV1 gene as a possible genetic marker in recognizing people at higher risks for metabolic diseases. It also indicated that using the MIND diet may help in improving dyslipidemia through providing a probable interaction with CAV1 rs3807992 polymorphism.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13104-021-05777-4.

Keywords: MIND diet, Metabolic dyslipidemia, Caveolin 1, Obesity, Personalized nutrition

Introduction

Dyslipidemia is a metabolic disorder that imposes an enormous burden on public health [1]. Some concerns exist regarding “Metabolic dyslipidemia” (MD), with high triglyceride (TG) and low levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, which is associated with an elevated risk of Coronary heart disease (CHD) [2, 3]. Dyslipidemia is a significant primary risk factor for atherosclerosis, which is considerably prevalent in Iran. Moreover, people with central obesity and diabetes have a greater susceptibility to dyslipidemia [4].

As a multifactorial condition, MD and obesity are also determined by environmental conditions such as dietary intake and genetic variations [5]. In this manner, genetically related investigations have examined cases linked to complex diseases related to dyslipidemia from various populations [6, 7]. CAV1 has the ability to regulate various signals as well as maintain cholesterol homeostasis [8]. It is associated with cholesterol release and dyslipidemia risk factors [9].

The content of dietary patterns is important as controlling factors linked to the risk of dyslipidemia [10]. Some studies have investigated the interplays between Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet and Mediterranean diet with dyslipidemia separately. It should be noted that high intakes of saturated fatty acids and unhealthful styles positively influence MD and the DASH diet is reported to have inverse associations with blood lipid concentrations [11]. A review on the correlation between dietary patterns and dyslipidemia also found that the DASH diet containing reduces the risk of MD [12]. The Mediterranean and Mediterranean-DASH intervention for MIND diet ingredients are replete with antioxidants that improve heart health and mitigate Hypertension (HTN) risk [13]. Another study examined the main role of the CAV1 gene in developing the cardiovascular disease with an effect on lipid factors and reported significant associations [14]. In this regard, we recently explored information about the interaction between CAV1 and dietary intake in overweight and obese women [15, 16].

To the authors’ knowledge, there has been no previous study evaluating the interaction between the MIND diet and CAV1 polymorphism towards dyslipidemia risk factors. Therefore, the present study intended to investigate the interaction between MIND diet with the CAV1 gene in association with MD.

Main text

Study population

In the present cross-sectional research, a random selection of referral patients was performed from health centers in Tehran, Iran. This study was approved by the Ethics Commission of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.142). Subjects included healthful overweight and non-menopause women aged over 18 years on average, with a BMI ranging from 25 to 40 kg/m2.

Women with a history of inflammatory disease, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, kidney failure, stroke, thyroid disease, liver disease, cancer, and those who were on weight loss programs or reported daily energy intakes between 800 and 4200 kcal/day, or using supplements and medications during the study time were all excluded.

Biochemical assessment

All blood samples were collected after having an 8–12 h fasting state at the Nutrition and Genomics Laboratory of TUMS. Moreover, fasting blood sugar (FBS), TG, total cholesterol level, low-density lipoprotein (LDL), and HDL were measured according to standard protocols [17]. All of which were measured at the Bionanotechnology laboratory, Tehran University of Medical Science.

Anthropometric measurement and body composition

The anthropometric indices were measured for all participants. Weight (kg), Height (m), waist circumference (WC, cm), and the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were measured. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Respectively the researchers assessed the body composition of all cases with the use of Body Composition Analyzer BC-418MA-In Body (United Kingdom). The device calculates body fat percentage, fat mass, and fat-free mass (FFM) and predicts skeletal muscle mass (SMM) based on data obtained by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) using bioelectrical impedance analysis.

Dietary assessment

The diet scores were estimated using a semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaires (FFQ) including a list of 147 food items this questionnaire has well-established reliability and validity specifically for Iranian adults [18, 19]. The software program, Nutritionist IV, was used for nutrient analysis and was modified for Iranian foods. A MIND diet score using the methodology described by Morris et al., focusing on 15 components is. There was a maximum of 15 points, higher intake of brain-healthy food groups, was scored 0, 0.5, or 1 point depending on the level of consumption [20].

Assessment of other variables

Assessment of physical activity was based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ).

Low HDL ≤ 50 mg/dl and TG > 150 mg/dl indices were considered for metabolic dyslipidemia in participants [21].

DNA genotyping

For DNA extraction from whole blood by the Gene All Mini Columns Type kit, 1 ml of RBC lysis solution was initially decanted into a 2 ml microtube that contained 300 μl of the blood and subjected to gentle shaking 5 times, followed by overtaxing for 10 s and then centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 3 min. Amplification of gene region containing CAV1 polymorphism (rs3807992) with G as the major allele (dominant allele) and A as the minor allele was conducted via the polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) technique using the following primers:

F: 3′AGTATTGACCTGATTTGCCATG5′, R: 5′GTCTTCTGGAAAAAGCACATGA-3′

The process of PCR reactions was conducted with an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of amplification including denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 42–50 °C for 1 min and elongation at 72 °C for 2 min.

Statistical analysis

Normality distribution was surveyed by applying Kolmogorov–Smirnov’s test. Data were analyzed by IBM SPSS version 22 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative variables were reported by (Mean ± SD) and qualitative variables were expressed using percentages and numbers. Comparison of quantitative and qualitative variables between genotypes and MIND diet was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Chi-square test respectively. The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed after adjustment for age, total energy intake, BMI, and physical activity. Binary logistic regression was used for calculating the odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for assessing the interaction between the MIND diet and genotypes on metabolic dyslipidemia.

Results

Study population characteristics

This cross-sectional study was performed on 263 overweight and obese women within the range of 18–55 years old. The means (± SD) of age and BMI of individuals were 36.67 ± 9.10 and 161.2 ± 5.87 (kg/m2).

The frequencies of the G allele were 38%. The overall prevalence of CAV1 rs3807992 genotypes was 25.5%, 22.3% and 47.8% for AA, AG, and GG respectively Table 1.

Table 1.

Cav1 rs3807992 genotypes and allelic variants of the study population

| Cav1 rs3807992 genotypes | Genotypes frequency | Alleles frequency | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | AG | AA | A | G | |

| 47.8% (n = 193) | 22.3% (n = 99) | 25.5% (n = 103) | 38.6% | 61.4% | |

The demographic, anthropomorphic, and biochemical characteristics of participants across quartiles of MIND are shown in Table 2. After adjustment for BMI, age, total energy intake, and physical activity, there was a significant difference in FFM (P = 0.03). The individuals in the fourth quartile had higher FFM rather than the first quartile. Moreover, there is a significant association between dyslipidemia (P = 0.01) and TG (P = 0.00) across the quartiles. It is shown that individuals with dominant alleles had higher dyslipidemia and a higher level of TG. Also, there was a marginally significant difference between groups for IPAQ and SMM (P = 0.06).

Table 2.

Participant characteristics consist of anthropometric measurements, and body composition, blood parameters across the quartiles of the MIND diet

| Variables | Q1(n = 97) | Q2 (n = 98) | Q3 (n = 98) | Q4 (n = 98) | P-value | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | ||||||

| Age (year) | 35.52 ± 8.69 | 37.49 ± 9.72 | 36.88 ± 9.71 | 36.88 ± 8.67 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.82 ± 12.21 | 80.43 ± 13.49 | 81.01 ± 12.01 | 82.40 ± 11.31 | 0.69 | 0.27 |

| Height (cm) | 161.04 ± 5.46 | 161.26 ± 5.96 | 161.20 ± 6.00 | 161.08 ± 6.17 | 0.99 | 0.63 |

| IPAC (MET-minutes/week) | 1007.75 ± 1754.61 | 785.62 ± 588.73 | 1339.00 ± 2699.21 | 1541.56 ± 2468.50 | 0.16 | 0.06 |

| Body composition | ||||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.29 ± 4.49 | 30.87 ± 4.64 | 31.22 ± 4.28 | 31.68 ± 3.77 | 0.62 | 0.35 |

| SMM (kg) | 25.19 ± 2.99 | 25.44 ± 3.54 | 25.51 ± 3.60 | 26.02 ± 3.49 | 0.38 | 0.06 |

| FFM (kg) | 45.99 ± 5.01 | 46.19 ± 5.74 | 46.57 ± 6.03 | 47.23 ± 5.83 | 0.44 | 0.03 |

| BFM (%) | 35.13 ± 9.15 | 34.15 ± 9.82 | 34.54 ± 8.55 | 35.09 ± 7.37 | 0.83 | 0.87 |

| WHR (%) | 1.87 ± 9.24 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.94 ± 0.05 | 0.93 ± 0.05 | 0.39 | 0.55 |

| WC (cm) | 99.43 ± 9.87 | 98.63 ± 10.54 | 99.80 ± 10.55 | 100.48 ± 9.33 | 0.63 | 0.27 |

| PBF (%) | 42.66 ± 5.65 | 42.04 ± 5.54 | 42.16 ± 5.51 | 42.03 ± 5.36 | 0.83 | 0.30 |

| Blood pressure | ||||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 108.97 ± 17.22 | 112.77 ± 13.26 | 112.62 ± 14.61 | 111.07 ± 14.39 | 0.41 | 0.96 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.37 ± 12.63 | 79.75 ± 9.37 | 77.75 ± 9.74 | 76.39 ± 9.62 | 0.17 | 0.35 |

| Biochemical assessment | ||||||

| FBS (mg/dl) | 86.30 ± 9.75 | 87.23 ± 9.08 | 88.20 ± 11.09 | 87.97 ± 8.76 | 0.72 | 0.77 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 124.33 ± 57.90 | 118.65 ± 65.13 | 121.53 ± 58.80 | 93.19 ± 50.9 | 0.13 | 0.45 |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 45.03 ± 9.16 | 48.43 ± 10.65 | 45.45 ± 9.77 | 47.83 ± 12.66 | 0.22 | 0.38 |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 90.67 ± 22.52 | 97.45 ± 24.92 | 94.53 ± 24.12 | 96.54 ± 24.82 | 0.46 | 0.49 |

| HOMA-IR | 3.33 ± 1.30 | 3.44 ± 1.35 | 3.38 ± 1.28 | 2.91 ± 0.89 | 0.34 | 0.92 |

| Insulin (mIU/ml) | 1.24 ± 0.22 | 1.18 ± 0.24 | 1.20 ± 0.24 | 1.22 ± 0.20 | 0.50 | 0.76 |

| hs.CRP (mg/l) | 4.59 ± 5.10 | 4.16 ± 4.51 | 3.92 ± 4.06 | 4.56 ± 4.93 | 0.84 | 0.61 |

| ALT (mg/dl) | 17.67 ± 7.10 | 17.30 ± 7.52 | 17.51 ± 7.47 | 18.60 ± 7.39 | 0.73 | 0.36 |

| AST (mg/dl) | 19.63 ± 13.36 | 17.43 ± 11.80 | 19.65 ± 14.16 | 19.81 ± 12.76 | 0.70 | 0.81 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dl) | 178.55 ± 38.37 | 190.16 ± 33.45 | 181.55 ± 37.48 | 188.63 ± 35.59 | 0.24 | 0.57 |

| MIND-score quartile | ||||||

| AA% | 28.7% | 23.8% | 28.7% | 18.8% | 0.67 | 0.45 |

| AG% | 15.9% | 28.0% | 25.6% | 30.5% | ||

| GG% | 26.8% | 24.7% | 22.6% | 25.8% | ||

| Dyslipidemia | ||||||

| Without | 85 (87.6%) | 73 (74.5%) | 71 (72.4%) | 60 (61.2%) | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| With | 12 (12.4%) | 25 (25.5%) | 27 (27.6%) | 38 (38.8%) | ||

| HDL (mg/dl) | ||||||

| < 50 | 63 (64.9%) | 61 (62.2%) | 58 (59.2%) | 51 (52.0%) | 0.06 | 0.74 |

| ≥ 50 | 34 (21.5%) | 37 (23.4%) | 40 (25.3%) | 47 (29.7%) | ||

| TG (mg/dl) | ||||||

| < 150 | 66 (68.0%) | 50 (51.0%) | 47 (48.0%) | 24 (24.5%) | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ≥ 150 | 31 (32.0% | 48 (49.0%) | 51 (52.0%) | 74 (75.5%) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 28 (25.9%) | 26 (24.1%) | 28 (25.9%) | 26 (25.9%) | 0.59 | 0.90 |

| Married | 68 (24.2%) | 71 (25.3%) | 70 (24.9%) | 72 (25.6%) | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| Illiterate | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0.61 | 0.27 |

| Underdiploma | 9 (18.4%) | 14 (28.6%) | 14 (28.6%) | 12 (24.5%) | ||

| College education | 87 (25.9%) | 83 (24.7%) | 82 (24.4%) | 84 (25.0%) | ||

| Economic status | ||||||

| Low | 9 (22.5%) | 9 (22.5%) | 10 (25.0%) | 12 (30.0%) | 0.47 | 0.91 |

| Moderate | 42 (25.3%) | 51 (30.7%) | 36 (21.7%) | 37 (22.3%) | ||

| Good | 40 (26.3%) | 31 (20.4%) | 41 (27.0%) | 40 (26.3%) | ||

| Excellent | 4 (21.1%) | 4 (21.1%) | 7 (36.8%) | 4 (21.1%) | ||

Bold values of table are significantly different from zero at P < 0.005

Quantitative variables were reported with mean and SD and qualitative variables with number and percentage values were calculated by ANOVA as mean ± SD

Variables are presented by mean ± SD for continuous variables and frequency for categorical variables

MD: metabolic dyslipidemia: TG > 150 and HDL < 40

BMI body mass index, WC waist circumference, WHR, waist-to-hip ratio, FFM fat-free mass, HDL high-density lipoprotein, hs-CRP high-sensitivity C reactive protein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, BMR basal metabolic rate, TG triacylglycerol, TC total cholesterol, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate transaminase, IPAC international physical activity questionnaire, PBF percent body fat, BFM body fat mass, SMM skeletal muscle mass

P values resulted from the analysis of one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. Tukey test was performed to compare each genotype with other types for continuous variables

*P-value is found by ANCOVA and adjusted for age, BMI, physical activity, and total energy intake

Investigation of body composition, biochemical variables, and RMRs among the CAV1 rs3807992 genotypes

Additional file 1: Table S1 shows the association between anthropometric body composition, biochemical parameters, and CAV1 rs3807992 genotypes. We observed that the individuals who had GG alleles had a higher level of DBP (P = 0.02). There is also a meaningful association between genotype and two categories of TG (P = 0.01). It was seen that 52.3% of GG carriers had TG < 150. It was seen that individuals with the higher carrier of AA had higher weight and lower levels of DBP rather than other groups.

Investigation of dietary intake among the CAV1 rs3807992 genotypes

The food group and nutrient intakes according to CAV1 rs3807992 genotypes are shown in (Additional file 1: Table S2). Significant differences were seen in other vegetable and fast food groups (P < 0.05).

Interaction of MIND diet and CAV1 rs3807992 with dyslipidemia

Interaction between the MIND diet and CAV1 rs3807992 gene variants on dyslipidemia is shown in (Additional file 1: Table S3). There was a significant interaction between MIND diet and genotype for metabolic dyslipidemia (β = − 0.25 ± 132, OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.60–1.00, P = 0.05) in the crude model. Whereby, subjects with dominant allele had a lower risk of dyslipidemia. Besides, in model one age, IPAC, BMI, and energy intake had been controlled for participants had (β = − 0.34 ± 152, OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.52–0.95, P = 0.02), after controlling for age, IPAC, BMI, energy intake and job was observed subjects to have 0.64-fold in model two (β = − 0.44 ± 165, OR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.46–0.88, P = 0.007), this inverse association becomes more significant.

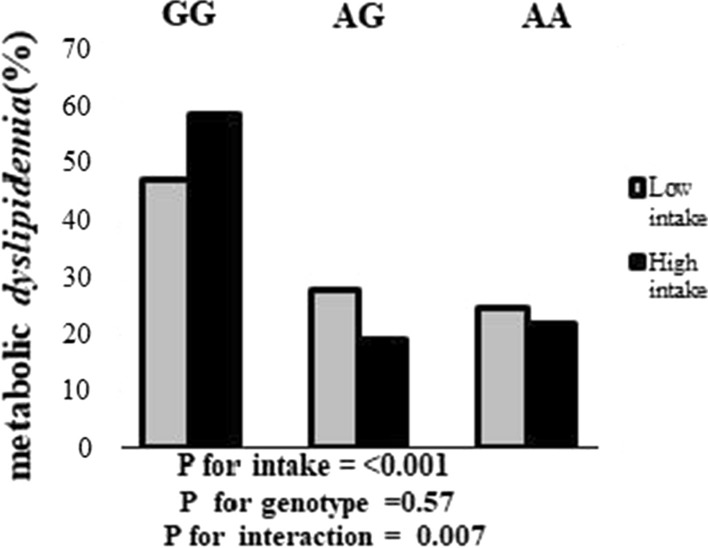

Percentage of Metabolic dyslipidemia across CAV1 rs3807992 genotypes based on a low and high intake of the MIND diet. The percentage of Metabolic dyslipidemia in low intake across GG, AG, and AA genotypes were respiratory—%, 27.8%, and 25%. The percentage of Metabolic dyslipidemia in high intake across GG, AG, and AA genotypes were respiratory—%, 19%, and 22.2% (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of Metabolic dyslipidemia across GG, AG, and AA genotypes based on intake of the MIND diet

Discussion

In this study, we reported the novel finding that AA carriers of rs3807992 CAV1 gene variant had higher weight rather than other groups. In this manner, we should note that CAV1 is a main fatty acid-binding protein in adipocytes [22, 23]. CAV1 also directly binds to cholesterol. A high amount of cholesterol is one of the hallmarks of the biogenesis of specialized membrane lipid rafts, called caveolae [24].

Recent studies exhibited that CAV1 can be transmitted to lipid droplets. It seems that the activity of CAV1is essential to preserve the perilipin function and the following lipid droplet integrity, thus its absence can result in the alterations of lipid droplet size [25, 26].

Previously, variants in the CAV1 gene have been connected to lipodystrophy, a disorder of unusual lipid distribution [27]. Today, various genome-wide studies have supported the correlation between the CAV1 variants and dyslipidemia, for instance, the low HDL and high TGs [28, 29]. Previous studies also showed the role of CAV1 in cardiometabolic disorders. These results were also reported in human studies with CAV1 mutations that exhibit dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and diabetes [30–33]. It is demonstrated that another variant of the CAV1 gene means rs926198 is linked to dyslipidemia, particularly low HDL cholesterol and also other metabolic disorders, including diabetes, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk in Caucasians and Hispanics. Therefore, it may be considered as a marker for cardiometabolic risk factors in non-obese people [34].

Remarkably, both knockout and autosomal recessive mutations in the CAV1 gene correlate with alterations in lipid and glucose metabolism despite a lean phenotype with reduced adiposity [31, 32]. Here we also elucidated that there was no significant association between all of the nutrients intakes across the three alleles of CAV1rs3807992 genotypes. There was a significant interaction between MIND diet and genotype for dyslipidemia and the AA carriers with higher adherence to the MIND diet may exhibit lower dyslipidemia. Nevertheless, there was no remarkable interaction between MIND diet and genotype on dyslipidemia after adjustments.

We also find a significant association between CAV1 genotypes with DBP, which remained significant after adjustment for age, BMI, physical activity, and total energy intake. Interestingly, AA carrier was associated with higher weight and lower DBP. However, another study on a Caucasian cohort with subsequent replication in a Hispanic cohort did not observe any relationship between the CAV1 variant and HTN [34].

Conclusion

The CAV1 gene seems to be a genetic marker that might help in recognizing people at higher risks for metabolic diseases. The present study indicates that using a novel diet as a MIND diet may help in improving dyslipidemia by providing a possible interaction with CAV1 rs3807992 gene variants. Finally, more large-scale clinical studies with longitudinal data are necessary to confirm our data and to investigate other available diets in this field of research.

Limitation

A food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) was used to assess dietary intake that is self-reported and accordingly, reliant on the patient’s memory. This research focused primarily on the composition of MIND diet. However, other dietary patterns can also contribute to the progression of MD. Finally, because this is an observational study, the relationships revealed in Iranian women may not be applicable for people of other races.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Participant characteristics consist of anthropometric measurement, body composition, and blood parameters across Cav1 rs3807992genotypes. Table S2. Dietary intake of study population according to Cav1 rs3807992 genotypes. Table S3. The interactions between mind diet and Cav1 rs3807992 genotype on the risk of MD.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

One-way analysis of variance

- ANCOVA

Analysis of covariance

- BMI

Body mass index

- CAV1

Caveolin 1

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- CHD

Coronary heart disease

- DASH

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- DXA

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBS

Fasting blood sugar

- FFQ

Food Frequency Questionnaires

- FFM

Fat-free mass

- HTN

Hypertension

- HDL

High-density lipoprotein

- IPAQ

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- MIND

Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay diet

- MD

Metabolic dyslipidemia

- LDL

Low-density lipoprotein

- PCR-RFLP

Polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism

- SMM

Skeletal muscle mass

- TG

Triglycerides

- WC

Waist circumference

- WHR

Waist-to-hip ratio

- WC

Waist circumference

- WHR

Waist-to-height ratio

Authors’ contributions

NK and FS contributed to conception and design. FA and FK contributed to all experimental work. AM contributed to data and statistical analysis. NK, FA, AM and FS wrote the manuscript. KM: supervision; validation; project administration. All authors meet the criteria listed above. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript has been granted by the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 98-03-212-46728). The funder had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article. We are grateful to all of the participants for their contribution to this research. This study was supported by grants from the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Availability of data and materials

The data are not publicly available due to containing private information of participants. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Khadijeh Mirzaei.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the study protocol was confirmed by The Human Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Ethics Number IR.TUMS.VCR.REC.1398.142). All participants signed a written informed consent that was approved by the Ethics committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kronenberg F, et al. Prevalence of dyslipidemic risk factors in hemodialysis and CAPD patients. Kidney Int. 2003;63:S113–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s84.23.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rana JS, et al. Metabolic dyslipidemia and risk of coronary heart disease in 28,318 adults with diabetes mellitus and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 100 mg/dl. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(11):1700–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker J, et al. Vitamin D, metabolic dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2012;125(10):1036. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klop B, Elte JW, Cabezas MC. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients. 2013;5(4):1218–1240. doi: 10.3390/nu5041218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Opoku S, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for dyslipidemia among adults in rural and urban China: findings from the China national stroke screening and prevention project (CNSSPP) BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7827-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berberich AJ, et al. The role of genetic testing in dyslipidaemia. Pathology. 2019;51(2):184–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2018.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cano-Corres R, Candás-Estébanez B, Padró-Miquel A, Fanlo-Maresma M, Pintó X, Alía-Ramos P. Influence of 6 genetic variants on the efficacy of statins in patients with dyslipidemia. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32(8):e22566. doi: 10.1002/jcla.22566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gratton JP, Bernatchez P, Sessa WC. Caveolae and caveolins in the cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 2004;94:1408–1417. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129178.56294.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peng XL, Qu W, Wang LZ, Huang BQ, Ying CJ, Sun XF, Hao LP. Resveratrol ameliorates high glucose and high-fat/sucrose diet-induced vascular hyperpermeability involving Cav-1/eNOS regulation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):0113716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu C, Xue Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Qiao D, Wang B, Mao Z, Yu S, Wang C, Li W, Li X. Association between dietary patterns and dyslipidemia in adults from the Henan rural cohort study. Asian Pac J Clin Nutr. 2020;29(2):777–780. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.202007_29(2).0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopes HF, Martin KL, Nashar K, Morrow JD, Goodfriend TL, Egan BM. DASH diet lowers blood pressure and lipid-induced oxidative stress in obesity. Hypertension. 2003;41:422–430. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000053450.19998.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Omar SH. Mediterranean-dash intervention for neurodegenerative delay (MIND) diet slows cognitive decline after stroke. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.van den Brink AC, Brouwer-Brolsma EM, Berendsen AA, van de Rest O. The Mediterranean, dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH), and Mediterranean-DASH intervention for neurodegenerative delay (MIND) diets are associated with less cognitive decline and a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease—a review. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(6):1040–1065. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmz054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia G, Sowers JR. Caveolin-1 in cardiovascular disease: a double-edged sword. Diabetes. 2015;64(11):3645–3647. doi: 10.2337/dbi15-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abaj F, Koohdani F, Rafiee M, Alvandi E, Yekaninejad MS, Mirzaei K. Interactions between Caveolin-1 (rs3807992) polymorphism and major dietary patterns on cardio-metabolic risk factors among obese and overweight women. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21(1):138. doi: 10.1186/s12902-021-00800-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abaj F, Mirzaei K. Caveolin-1 genetic polymorphism interact with polyunsaturated fatty acids to modulate metabolic syndrome risk. Br J Nutr. 2021 doi: 10.1017/S0007114521002221.1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haile B, Wolde M, Gebregziabiher T. Assessment of fasting blood glucose, serum electrolyte, albumin, creatinine, urea and lipid profile among hypertensive patients and non-hypertensive participants at Wolaita Sodo University teaching and referral hospital. biorxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.10.27.356873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mirmiran P, Hosseini-Esfahani F, Jessri M, Mahan LK, Shiva N, Azizi F. Does dietary intake by Tehranian adults align with the 2005 dietary guidelines for Americans observations from the Tehran lipid and glucose study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2005;29:39–52. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v29i1.7564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rezazadeh A, Rashidkhani B. The association of general and central obesity with major dietary patterns of adult women living in Tehran, Iran. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2010;56:132–138. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.56.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, Sacks FM, Bennett DA, Aggarwal NT. MIND diet associated with reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease. HHS Public Access. 2015;11:1007–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rana JS, Visser ME, Arsenault BJ, Després JP, Stroes ES, Kastelein JJ, Wareham NJ, Boekholdt SM, Khaw KT. Metabolic dyslipidemia and risk of future coronary heart disease in apparently healthy men and women: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Int J Cardiol. 2010;143(3):399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.03.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerber GE, Mangroo D, Trigatti BL. Identification of high affinity membrane-bound fatty acid-binding proteins using a photoreactive fatty acid. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;123(1–2):39–44. doi: 10.1007/BF01076473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trigatti BL, Anderson RG, Gerber GE. Identification of caveolin-1 as a fatty acid binding protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;255(1):34–39. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Londos C, Brasaemle DL, Schultz CJ, Adler-Wailes DC, Levin DM, Kimmel AR, et al. On the control of lipolysis in adipocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:155–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pol A, Luetterforst R, Lindsay M, Heino S, Ikonen E, Parton RG. A caveolin dominant negative mutant associates with lipid bodies and induces intracellular cholesterol imbalance. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(5):1057–1070. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostermeyer AG, Paci JM, Zeng Y, Lublin DM, Munro S, Brown DA. Accumulation of caveolin in the endoplasmic reticulum redirects the protein to lipid storage droplets. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(5):1071–1078. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.5.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao H, Alston L, Ruschman J, Hegele RA. Heterozygous CAV1 frameshift mutations (MIM 601047) in patients with atypical partial lipodystrophy and hypertriglyceridemia. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:3. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tam CH, Lam VK, So W-Y, Ma RC, Chan JC, Ng MC. Genome-wide linkage scan for factors of metabolic syndrome in a Chinese population. BMC Genet. 2010;11(1):14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loos RJ, Katzmarzyk PT, Rao DC, Rice T, Leon AS, Skinner JS, et al. Genome-wide linkage scan for the metabolic syndrome in the HERITAGE family study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5935–5943. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abaj F, Saeedy SAG, Mirzaei K. Are caveolin-1 minor alleles more likely to be risk alleles in insulin resistance mechanisms in metabolic diseases? BMC Res Notes. 2021;14(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s13104-021-05597-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuengsamarn S, Garza AE, Krug AW, Romero JR, Adler GK, Williams GH, et al. Direct renin inhibition modulates insulin resistance in caveolin-1-deficient mice. Metab Clin Exp. 2013;62(2):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim CA, Delépine M, Boutet E, El Mourabit H, Le Lay S, Meier M, et al. Association of a homozygous nonsense caveolin-1 mutation with Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(4):1129–1134. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pojoga LH, Yao TM, Opsasnick LA, Garza AE, Reslan OM, Adler GK, et al. Dissociation of hyperglycemia from altered vascular contraction and relaxation mechanisms in caveolin-1 null mice. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 2013;348(2):260–270. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.209189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baudrand R, Goodarzi MO, Vaidya A, Underwood PC, Williams JS, Jeunemaitre X, et al. A prevalent caveolin-1 gene variant is associated with the metabolic syndrome in Caucasians and Hispanics. Metab Clin Exp. 2015;64(12):1674–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Participant characteristics consist of anthropometric measurement, body composition, and blood parameters across Cav1 rs3807992genotypes. Table S2. Dietary intake of study population according to Cav1 rs3807992 genotypes. Table S3. The interactions between mind diet and Cav1 rs3807992 genotype on the risk of MD.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to containing private information of participants. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Khadijeh Mirzaei.