Abstract

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has the authority to regulate characteristics of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Prior research indicates that regulation of certain characteristics of these products may have an effect on their appeal and use. Policies that affect appeal and use of ENDS are relevant to attempts to reduce use among young people—including young adults—but are also relevant to adults who use these products as harm reduction tools. Using a novel concurrent choice task, we evaluated the relative reinforcement of JUUL brand ENDS products that varied in flavor (n=8) and nicotine (n=8) among samples of young adults who use JUUL. Findings suggest that restricting JUUL flavor to tobacco-only results in decreased appeal, while reducing the nicotine content of JUUL pods to 3%—from the conventional 5%—does not have an effect on product appeal. Findings also validate a novel methodology for delivering fixed doses of ENDS vapor within the context of a task that assesses the relative reinforcement of ENDS products with varying characteristics. This methodology can be applied to assessing the relative reinforcing effects of a wide variety of tobacco products with varied characteristics.

Keywords: JUUL, flavor, nicotine content

Introduction

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act of 2009 gave the United States (U.S.) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulatory authority over the manufacture, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products (U.S. Congress, 2009). In 2016, the FDA extended its regulatory authority to explicitly include electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) products (Food and Drug Administration, 2016). Indeed, accumulating research indicates that regulation of ENDS characteristics (e.g., flavor, nicotine content) could potentially impact the use of ENDS via decreased appeal of these products. These potential impacts are relevant not only for attempts to reduce the likelihood of use among youth and adolescents, but may also affect ENDS product use among adult established users, including those who have or are seeking to reduce or quit combusted tobacco product use via harm reduction methods. Indeed, relevant regulatory action regarding ENDS flavors has already been undertaken in the U.S.: In January 2019, San Francisco, California implemented a comprehensive ban on the sale of flavored ENDS products—excluding tobacco flavor (San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2018). Additionally, in January 2020, the FDA finalized a flavor enforcement policy under which the sale of flavored pod- and cartridge-based ENDS is prohibited, though tobacco- and menthol-flavored pods/cartridges are exempted (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020).

The availability of flavors is viewed as an appealing characteristic of ENDS products among both youth/adolescents (Ambrose et al., 2015; Harrell et al., 2017; Kong, Morean, Cavallo, Camenga, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2015; Tsai et al., 2018) and adults (Cheney, Gowin, & Wann, 2016; Evans et al., 2020; Leventhal et al., 2020; McDonald & Ling, 2015; Patel et al., 2016; Sussman et al., 2014) who use ENDS. The appeal of flavored ENDS is evident among young adults, in particular: A qualitative study of young adults reported that being able to consume a wide variety of e-liquid flavors is a motivation for using ENDS (Cooper, Harrell, & Perry, 2016). Moreover, laboratory studies of the impact of e-liquid flavors on subjective appeal among young adults have also indicated that flavored e-liquids—and sweet-flavored e-liquids, in particular—resulted in greater appeal ratings (Audrain-McGovern, Strasser, & Wileyto, 2016) such as liking and willingness to use again compared to non-sweet (e.g. tobacco) and flavorless e-liquids (Goldenson et al., 2016). Recent research also indicates that limiting the availability of ENDS e-liquid flavors results in decreased appeal of ENDS (Leventhal et al., 2020), as well as decreased intended use of and hypothetical choices for ENDS among samples of people who smoke cigarettes (Buckell, Marti, & Sindelar, 2018) and people who are dual users of both ENDS and cigarettes (Pacek, Rass, Sweitzer, Oliver, & McClernon, 2019).

In addition to flavor, the nicotine content of ENDS also contributes to their appeal. Use of ENDS with greater nicotine concentrations result in greater plasma nicotine concentrations (Phillips-Waller, Przulj, Smith, Pesola, & Hajek, 2021; Ramôa et al., 2016). Products that produce desirable airway irritation caused by nicotine (i.e., “throat hit”) are sometimes self-reported as reasons for vaping among young adults (Pokhrel, Herzog, Muranaka, & Fagan, 2015), though experimental evidence has not borne this out (Goldenson et al., 2016). Additionally, nicotine-containing—versus nicotine-free—ENDS are more effective at reducing craving to smoke cigarettes (Bullen et al., 2010; Perkins, Karelitz, & Michael, 2017) and nicotine withdrawal (Perkins et al., 2017), as well as the number of cigarettes smoked per day when used by persons who smoke cigarettes (Tseng et al., 2017). Conversely, In a randomized double-blind crossover design study, Meier and colleagues (Meier et al., 2017) found no differences in terms of withdrawal, satisfaction, intention to quit or confidence to quit using cigarettes, or carbon monoxide or urinary cotinine between users of nicotine-containing versus nicotine-free ENDS. Also, Leventhal and colleagues (Leventhal et al., 2020) found that acute use of nicotine-containing e-liquids in a laboratory-based paradigm actually decreased appeal of ENDS among people who are dual users of both ENDS and cigarettes. These mixed findings potentially suggest that factors in addition to nicotine content alone (e.g., sensory components of vaping, interactive effects between flavor and nicotine content (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2017; Rosbrook & Green, 2016)) are responsible for the appeal of nicotine-containing ENDS products. Regardless, recent work conducted in the U.S. suggests that reducing the nicotine content of ENDS may reduce intentions to use ENDS, while simultaneously having the unintended consequence of increasing intentions to use combusted cigarettes among young adults (Pacek et al., 2019).

Given the evidence above, it is likely that regulation that limits the diversity of available ENDS products with respect to flavor and nicotine content will also have an effect on ENDS appeal and use (Pacek, Wiley, & McClernon, 2018). For instance, within the context of hypothetical choice tasks among people who use both ENDS and cigarette, restricting the available flavors of ENDS (Buckell, Marti, & Sindelar, 2017; Pacek, Oliver, & McClernon, 2018), as well as restricting the availability of desired ENDS nicotine contents (Pacek et al., 2018), has been found to increase the likelihood of participants’ choosing to decrease their use of ENDS. Survey data collected among a sample of young adults following the implementation of a comprehensive tobacco product flavor ban in San Francisco, California indicated that the overall prevalence of flavored tobacco use as well as flavored ENDS use decreased, but was not eliminated (Yang, Lindblom, Salloum, & Ward, 2020). Moreover, the authors observed a marginally significant trend for an increase in cigarette smoking, regardless of menthol preference (Yang et al., 2020).

In order to anticipate and evaluate the outcomes resulting from tobacco product regulation—including those described above—data regarding how tobacco users value products with varying characteristics relative to one another are needed. In the present study, we validate a novel method of delivering fixed doses of ENDS vapor—within the context of a concurrent choice task—in order to evaluate the relative reinforcement of ENDS products with varying characteristics among samples of young adults who use JUUL. JUUL are pod-based ENDS products that, at the time of the study, were available in a variety of flavors and two nicotine contents and comprised more than 70% of the ENDS marketplace (Truth Initiative, 2019). Moreover, JUUL products are subject to the previously mentioned FDA flavor enforcement policy regarding pod-based ENDS. The study was conceived of and data collection completed prior to the ban on pod flavors. We have utilized this procedure—in which participants engaged in a concurrent choice task during which they expended effort to earn fixed doses of ENDS vapor—to estimate the differential demand for ENDS of varying flavors and nicotine content.

Method

Participants

Eligible participants (n=16) were young adults (age 18-25) who used JUUL ENDS and reported using a JUUL device ≥15 days per month for ≥3 months and reported current use of JUUL-branded pods. The latter criterion was established to avoid recruiting individuals who used non-JUUL branded and/or refillable pods that are compatible with JUUL devices and to ensure that we would be able to provide participants with their preferred-flavor and -nicotine content JUUL pods. Participants were required to have an expired breath alcohol level of 0; report a non-tobacco flavor as their preferred pod flavor (for the Flavor Study only); not have allergies to propylene glycol or glycerin; not be pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or breastfeeding (if female); and have systolic and diastolic blood pressure of <160 mmHg and <100 mmHg, respectively, and heart rate of <115 beats per minute. In an attempt to recruit people who use JUUL who were representative of the larger ENDS-using population in the U.S., and due to the significant prevalence of other tobacco product use among people who use ENDS (Pacek, Villanti, & Mcclernon, 2019), other tobacco product use was not an exclusion criterion for this study. The institutional review board at Duke University School of Medicine approved this study (Pro00101275; “Behavioral Assessment of Tobacco Product Valuation”).

Procedures

After obtaining informed consent, participants completed screening measures in order to determine whether they were eligible for the study. Participants provided expired breath alcohol level and carbon monoxide level samples, in addition to height and weight, and a urine pregnancy test (if female). Participants also completed the following measures: Tobacco Use History, Stages of Change (DiClemente et al., 1991), and eFTND (i.e., the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence ((Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991), modified to apply to vaping).

Following completion of screening measures, eligible participants completed the remaining study procedures during a single study visit. Half of the sample (n=8) was randomized to the Flavor Study and half (n=8) was randomized to the Nicotine Study. In each study, participants were given access to two different JUUL pods. In the Flavor Study, participants were given access to their preferred flavor JUUL pod, as well as a Virginia Tobacco-flavored JUUL pod. Both pods had 5% nicotine content. In the Nicotine Study, participants had access to a 5% nicotine content JUUL pod in their preferred flavor, as well as a preferred flavor-matched 3% nicotine content JUUL pod. At the time of the study (April – October 2019), possible flavors included Mint, Menthol, Mango, Cucumber, Crème, and Fruit. Aside from the JUUL pods available to participants, all procedures for both studies were identical.

Product Appeal Phase.

During the Product Appeal Phase, participants were familiarized with the controlled puff volume apparatus (CPVA; (Levin, Rose, & Behm, 1989)). We used a CPVA that was modified to allow for the administration of controlled doses of JUUL vapor (see Supplemental Figure 1). We chose to administer controlled doses of vapor because under conditions of self-administration, the amount of product self-delivered could be confounded with product characteristics, thus clouding interpretation of subjective and behavioral effects. Participants were given access to two CPVAs—one loaded with the participants’ preferred JUUL pod and the other loaded with the non-preferred JUUL pod. Participants—but not staff—were initially blinded to which CPVA contained which JUUL pod. The order of product sampling was randomized and counterbalanced (e.g., preferred or non-preferred pod sampled first).

Participants were instructed to take 4 puffs (60 mL per puff; 30 second inter-puff interval) of the first pod. These puffing parameters were selected to give participants experience with the study JUUL pods, while balancing too little exposure (e.g., a single puff) and higher levels of exposure (e.g., 10 puffs) which may risk satiation prior to completing the Reinforcement Phase procedures (i.e., reducing the likelihood that participants would make choices to use either of the offered JUUL pods). Additionally, the 60 mL puff volume is based on the mean puff volume recorded during cigarette smoking topography from a large number (n = 840) of cigarette smokers (unpublished findings from CENIC I trial); At the time of the study, no reliable estimates of puff volumes from JUUL topography were available in the literature. After sampling, participants completed the Vaping Effects Questionnaire—a modified version of the Cigarette Evaluation Scale (Cappelleri et al., 2007). The Vaping Effects Questionnaire pertained specifically to the pod that participants had just sampled. Following a 5-minute break, participants sampled the second pod (using the same procedures detailed above). After sampling the second pod, participants completed a battery of self-report questionnaires. Participants completed a measure of detailed sociodemographic characteristics and an additional measure of ENDS dependence: the Penn State E-Cigarette Dependence Index (Foulds et al., 2015). Additionally, participants completed the Perceived Health Risks scale (Hatsukami, Vogel, Severson, Jensen, & O’Connor, 2016; Pacek, McClernon, et al., 2018) and were asked, on a scale from 1-10, to rate their perceived risk of developing a variety of health conditions as a result of a) their JUUL use; b) general ENDS use; and c) cigarette smoking. Health conditions included the following: lung cancer, heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma, liver disease, emphysema, respiratory infections, other cancers, addiction, harm to self, and harm to others.

Reinforcement Phase.

The Reinforcement Phase occurred 30 minutes after completion of the Appeal Phase. During the Reinforcement Phase, participants were given access to the same CVPAs, outfitted with the same JUUL pods, as during the Appeal Phase. We utilized a validated concurrent-choice progressive ratio task (PRT) in which participants were able to earn opportunities to take puffs from the two JUUL pods over the course of one hour. Participants earned puffs by clicking designated buttons on a computer screen—one that corresponded to the preferred JUUL pod and one that corresponded to the non-preferred JUUL pod. The buttons were situated side-by-side on a plain computer background, and identical in appearance (i.e., gray, square), but were labelled “Preferred” and “Non-Preferred.” Earning puffs from the non-preferred JUUL pod required clicking the designated button 10 times; every 10 button clicks would result in earning an additional puff. Earning puffs from the preferred JUUL pod required 10 clicks on the designated button the first time, and an increasing number of button clicks moving forward (i.e., 10, 53, 107, 213, 427, 800, 1200, 1600, 2400, 2800). The progressive ratio was based on that in (Higgins et al., 2017), but scaled down to one-third of the Higgins et al. progressive ratio, as the task in the present study was one-third the total duration of that in the Higgins study (i.e., 1 hour versus 3 hours). As in the Appeal Phase, the size of the puffs available following button presses was standardized across participants (60 mL) via the CPVAs.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics described the sociodemographic and tobacco use characteristics of participants. Within each study, Wald tests were used to assess differences between participants’ preferred and non-preferred pods in terms of subjective effects, risk perceptions, and the number of choices for preferred versus non-preferred pods. T-tests were utilized to compare the overall number of puffs earned, as well as the proportion of puffs earned to use the preferred pod, between the Flavor and Nicotine studies. Alpha levels were set at 0.05.

Results

Participant characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics

Slightly more than half of the sample (56.2%) were female and the average age was 20.1 years (SD=1.9) (Table 1). Participants were predominantly White (87.5%)—with the remaining 12.5% reporting Black race—and all were of non-Hispanic ethnicity (100.0%). One participant (6.3%) reported having attained less than a high school education, 25% had a high school diploma, 62.4% reported completing some college, and 6.3% had a Bachelor’s degree. No differences were observed between participants in the Flavor and Nicotine studies on the basis of sociodemographic characteristics (all p’s < 0.05).

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic characteristics

| Overall (n=16) |

Flavor Study (n=8) |

Nicotine Study (n=8) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex – n (%) | |||

| Male | 7 (43.8%) | 3 (37.5) | 4 (50.0) |

| Female | 9 (56.2%) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (50.0) |

| Age – mean (SD) | 20.1 (1.9) | 19.6 (1.9) | 20.6 (1.9) |

| Race – n (%) | |||

| White | 14 (87.5) | 7 (12.5) | 7 (12.5) |

| Black | 2 (12.5) | 1 (87.5) | 1 (87.5) |

| Non-Hispanic ethnicity – n (%) | 16 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) |

| Education – n (%) | |||

| Some high school | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| High school diploma | 4 (25.0) | 3 (37.5) | 1 (12.5) |

| Some college | 10 (62.4) | 5 (62.5) | 5 (62.5) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) |

Tobacco Use Characteristics

Participants regularly used JUUL, reporting use on an average of 28.4 days per month (SD=3.5) (Table 2). Participants reported moderate dependence on ENDS via the eFTND (M=5.3 [SD=2.4]) and the PS Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index (M=10.3 [SD=4.3]). The majority of the sample most often used Mint (68.8%), 18.8% reported use of Mango, 6.2% used Menthol, and 6.2% used Crème flavored pods. All participants regularly used JUUL pods with 5% nicotine strength. Most had used other types of ENDS (93.7%) and had reported any use of cigarettes in the past (87.5%); 20.0% and 31.3% reported current use of other ENDS and cigarettes, respectively. Among those who had used cigarettes in the past, the majority reported that cigarette use preceded their trying other ENDS (92.9%) and JUUL (100.0%). Most (93.8%) reported lifetime use of tobacco products other than ENDS or cigarettes (e.g., little cigars), though only 37.5% reported past-month use. The majority (87.5%) also reported lifetime use of cannabis and tobacco concurrently (e.g., blunts), and 62.5% reported past-month use. Half (50.0%) of the sample reported vaping THC in their lifetime. Participants reported perceiving similar levels of risk associated with using JUUL versus other ENDS for all health conditions listed, with the exception of risk for addiction, which participants perceived to be greater when using JUUL (M=6.4 [SD=1.1] versus M=6.0 [SD=1.2]; p=0.029). Participants reported significantly greater perceived risk associated with using regular cigarettes—as compared to when using JUUL—for all health conditions (p’s<0.001 - <0.04), with the exception of risk for developing asthma (p=0.055) and addiction (p=0.164), which were rated as being comparable between the two products. No differences were observed between participants in the Flavor and Nicotine studies on the basis of tobacco use characteristics (all p’s > 0.05).

Table 2.

Participant tobacco use history characteristics

| Overall (n=16) |

Flavor Study (n=8) |

Nicotine Study (n=8) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| JUUL Use | |||

| Age at first JUUL use – mean (SD) | 18.8 (2.1) | 18.0 (2.3) | 19.5 (1.8) |

| Age at regular JUUL use – mean (SD) | 19.1 (1.9) | 18.6 (2.1) | 19.5 (1.8) |

| Duration of JUUL use (in months) – mean (SD) | 11.9 (7.9) | 13.1 (9.4) | 10.8 (6.4) |

| JUUL use frequency – n (%) | |||

| Every day | 13 (81.3) | 7 (87.5) | 6 (75.0) |

| Some days | 3 (18.7) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (25.0) |

| Not at all | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Average days using JUUL per month – mean (SD) | 28.4 (3.5) | 29.4 (1.8) | 27.5 (4.6) |

| Average puffs per day – mean (SD) | 118 (130.9) | 96.3 (92.6) | 141.1 (164.4) |

| eFTND – mean (SD) | 5.3 (2.4) | 4.9 (2.9) | 5.6 (2.0) |

| PS Electronic Cigarette Dependence Index – mean (SD) | 10.3 (4.3) | 11.8 (4.9) | 8.8 (3.4) |

| JUUL Pod Flavor – n (%) | |||

| Mint | 11 (68.8) | 5 (62.5) | 6 (75.0) |

| Mango | 3 (18.8) | 2 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| Menthol | 1 (6.2) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Crème | 1 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| JUUL Pod Nicotine strength – n (%) | |||

| 3% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 5% | 16 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| E-cigarette Use | |||

| Ever use of other e-cigarette(s) – n (%) | 15 (93.7) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (100.0) |

| Current, regular use of other e-cigarette(s) – n (%) | 3 (20.0) | 1 (14.3) | 3 (20.0) |

| Ever vape THC – n (%) | 8 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) | 3 (37.5) |

| Cigarette Use | |||

| Ever smoke a cigarette – n (%) | 14 (87.5) | 6 (75.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Cigarette smoking frequency – n (%) | |||

| Every day | 1 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| Some days | 4 (28.6) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (37.5) |

| Not at all | 9 (64.3) | 5 (83.3) | 4 (50.0) |

| Tried cigarettes before trying e-cigarettes* – n (%) | 13 (92.9) | 5 (83.3) | 8 (100.0) |

| Tried cigarettes before trying JUUL* – n (%) | 14 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) |

| Used cigarettes regularly before using e-cigarettes regularly** – n (%) | 3 (60.0) | 1 (100.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Used cigarettes regularly before using JUUL regularly** – n (%) | 3 (60.0) | 1 (100.0) | 2 (50.0) |

| Other Tobacco Product Use | |||

| Ever used other tobacco products – n (%) | 15 (93.8) | 7 (87.5) | 8 (100.0) |

| Currently use other tobacco products – n (%) | 6 (37.5) | 2 (25.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Ever used cannabis and tobacco together – n (%) | 14 (87.5) | 7 (87.5) | 7 (87.5) |

| Currently use cannabis and tobacco together – n (%) | 10 (62.5) | 5 (62.5) | 5 (62.5) |

Note.

Indicates that question was asked of participants who reported lifetime use of cigarettes.

Indicates that the question was asked of participants who reported lifetime regular use of cigarettes.

Appeal phase

Vaping Effects Questionnaire

Following sampling of their preferred (i.e., preferred flavor) and non-preferred (i.e., tobacco flavor) JUUL pods, participants in the Flavor Study reported that their preferred pod resulted in greater ratings of pleasant sensations (p<0.001), pleasurable rush or buzz (p=0.021), liking (p<0.001), satisfaction (p<0.001), wanting more of the product (p=0.002), good taste (p<0.001), enjoyment of sensations in the chest and throat (p=0.029), similarity to their preferred JUUL pod (p<0.001) (Table 3). Participants also rated their preferred pod as providing less reduction in craving for ENDS as compared to their non-preferred pod (p=0.017).

Table 3.

Vaping Effects Questionnaire

| Flavor Study | Nicotine Study | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Preferred Pod | Preferred Pod | p-value | Non-Preferred Pod | Preferred Pod | p-value | |

| Pleasant sensations | 36.5 (26.7) | 88.5 (14.7) | <0.001 | 69.9 (15.0) | 81.1 (17.8) | 0.193 |

| Unpleasant sensations | 41.9 (39.8) | 8.9 (17.5) | 0.050 | 18.4 (17.6) | 17.6 (20.8) | 0.939 |

| Relaxation | 53.0 (31.6) | 78.0 (17.0) | 0.069 | 67.3 (19.9) | 79.1 (20.9) | 0.265 |

| Pleasurable rush or buzz | 37.5 (27.2) | 66.6 (16.4) | 0.021 | 42.8 (35.5) | 56.9 (34.6) | 0.434 |

| Nausea | 6.9 (11.1) | 1.1 (2.2) | 0.173 | 4.4 (10.5) | 5.4 (14.0) | 0.874 |

| Dizziness | 17.5 (28.0) | 22.3 (24.5) | 0.724 | 13.4 (24.4) | 16.3 (19.8) | 0.780 |

| Coughing | 12.6 (35.3) | 1.3 (3.5) | 0.380 | 10 (17.1) | 12.4 (18.3) | 0.793 |

| Difficulty inhaling | 26.3 (28.8) | 11.3 (15.8) | 0.218 | 10.0 (16.0) | 10.8 (13.4) | 0.921 |

| Liking | 27.4 (22.0) | 91.8 (15.5) | <0.001 | 65.1 (23.6) | 81.0 (19.7) | 0.166 |

| Satisfying | 36.8 (21.6) | 89.3 (15.6) | <0.001 | 69.5 (24.7) | 80.0 (28.2) | 0.441 |

| Want more | 28.9 (28.2) | 74.3 (17.5) | 0.002 | 52.3 (26.4) | 73.0 (26.1) | 0.136 |

| Feel the effects | 39.5 (30.7) | 63.6 (19.8) | 0.083 | 53.5 (29.9) | 70.0 (25.6) | 0.256 |

| How high in nicotine | 49.0 (29.0) | 69.0 (29.2) | 0.191 | 41.4 (17.2) | 52.3 (21.4) | 0.281 |

| Irritation | 25.3 (30.9) | 7.6 (14.5) | 0.169 | 9.4 (18.6) | 9.5 (15.0) | 0.988 |

| Good taste | 19.6 (19.5) | 90.5 (17.8) | <0.001 | 59.9 (25.2) | 77.0 (21.6) | 0.167 |

| Enjoy the sensations in chest/throat | 22.5 (34.0) | 66.4 (33.1) | 0.029 | 52.5 (24.1) | 49.5 (35.3) | 0.845 |

| Reduced craving for e-cigarettes | 67.0 (17.5) | 33.9 (30.0) | 0.017 | 49.3 (29.2) | 50.0 (22.6) | 0.954 |

| Strong throat hit | 60.9 (36.6) | 41.9 (30.5) | 0.278 | 39.1 (30.5) | 42.0 (31.7) | 0.856 |

| Similarity to preferred JUUL | 22.6 (31.1) | 99.9 (0.4) | <0.001 | 72.4 (26.2) | 89.1 (10.9) | 0.117 |

| How much would you pay for a day’s worth? | $3.72 (6.79) | $6.47 (7.59) | 0.458 | $3.75 (1.16) | $4.19 (1.16) | 0.465 |

Note: Bold text indicates statistically significant difference at p=0.05

Participants in the Nicotine Study, conversely, did not report differences in ratings between their preferred (i.e., 5% nicotine content) and non-preferred (i.e., 3% nicotine content) pods on the Vaping Effects Questionnaire for any item, including the item rating how high the sampled pod was in nicotine (p=0.281).

Reinforcement phase

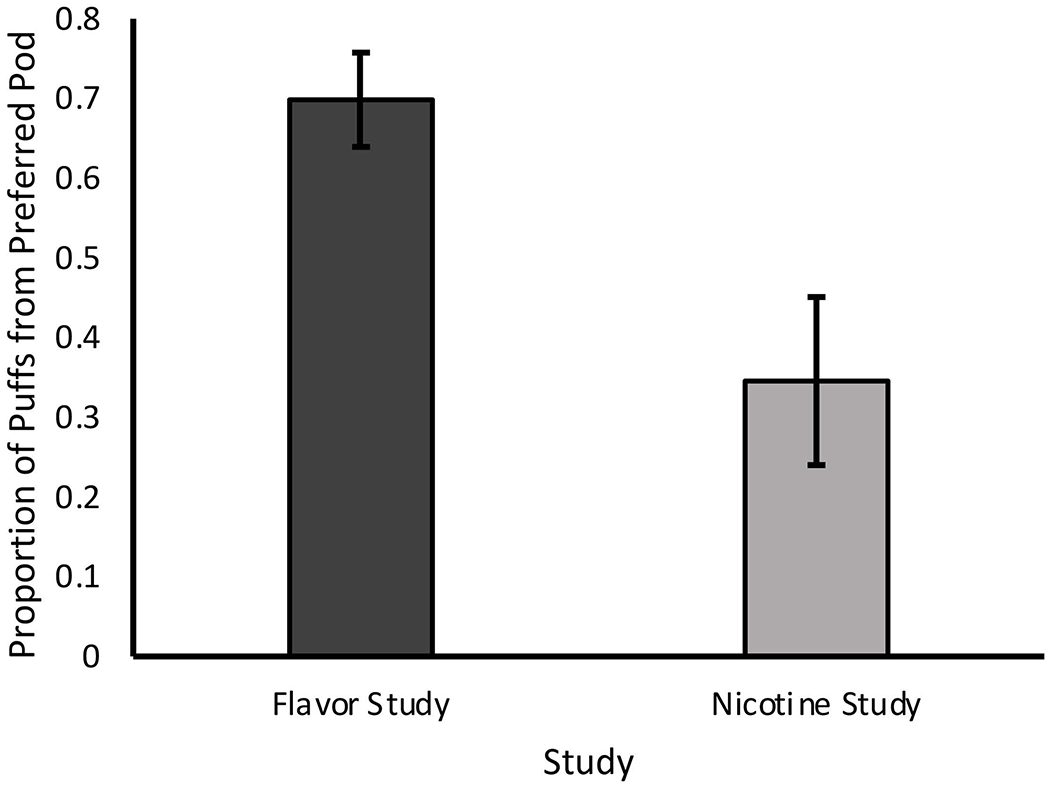

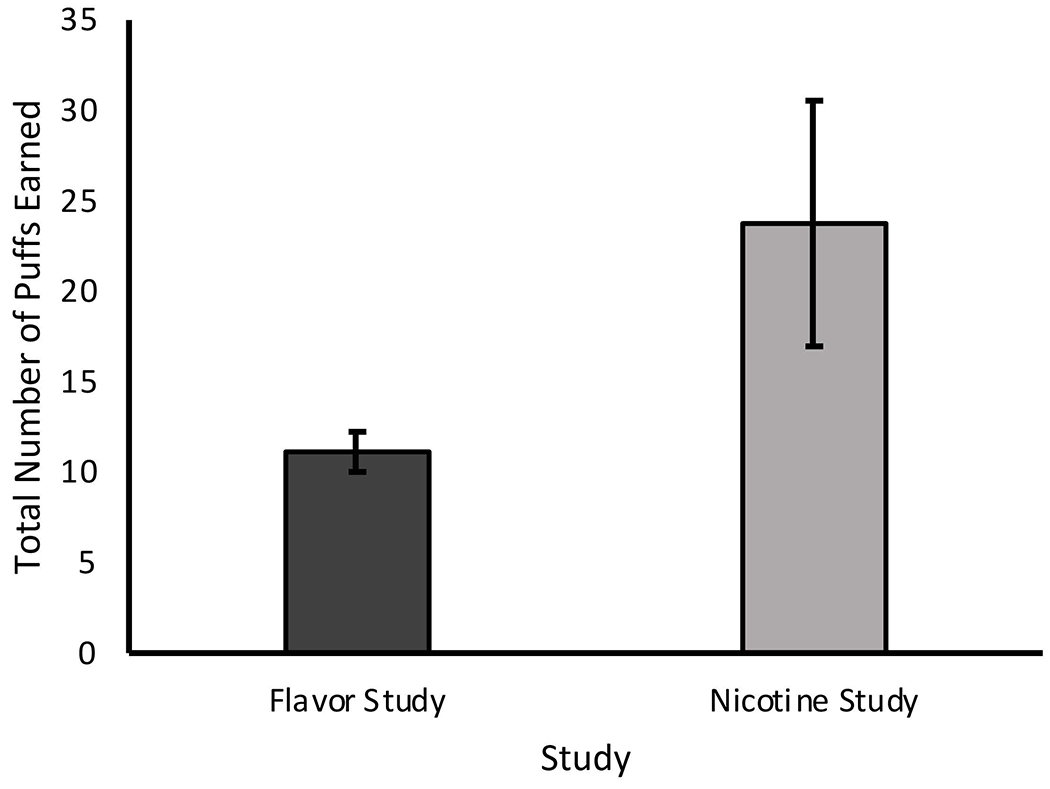

In the Flavor Study, participants made an average of 4,175.9 (SD=3,108.1) clicks on the button corresponding to the preferred pod and an average of 36.3 (SD=24.5) clicks on the button corresponding to the non-preferred pod. Flavor Study participants earned a significantly greater number of puffs from their preferred pod (mean=7.5 [SD=1.6]) than the non-preferred pod mean=3.6 [SD=2.4]; p=0.005). Conversely, in the Nicotine Study, participants made an average of 1,151.8 (SD=1,145.8) clicks on the button corresponding to the preferred pod and an average of 191.3 (SD=24.5) clicks on the button corresponding to the non-preferred pod. Nicotine Study participants earned a significantly greater number of puffs from the non-preferred pod (mean=19.1 [SD=17.9]) as compared to their preferred pod (mean=4.6 [SD=1.9]; p=0.043). These findings are depicted in Figure 1A and 1B. When comparing across the two studies and considering the total number of puffs that participants earned during the task, participants in the Flavor Study earned a significantly greater proportion of puffs for their preferred JUUL pod than did individuals in the Nicotine Study (mean=0.70 [SD=0.17] vs. 0.35 [SD=0.30]; p=0.011) (Figure 2). However, the average total number of puffs earned did not differ significantly between the Flavor or Nicotine Study (mean=11.1 [SD=3.1] vs. 23.8 [SD=19.2]; p=0.088) (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

A. Number of puffs earned from preferred versus non-preferred pods in the Flavor Study (n=8); p=0.005. B. Number of puffs earned from preferred versus non-preferred pods in the Nicotine Study (n=8); p=0.043

Figure 2.

Proportion of puffs earned from preferred JUUL pods, comparing Flavor (n=8) and Nicotine Studies (n=8); p=0.011

Figure 3.

Total number of puffs earned from either JUUL pod, comparing Flavor (n=8) and Nicotine (n=8) Studies; p=0.088

Discussion

Findings from the present studies indicate that limiting the availability of JUUL flavors to tobacco only significantly decreases the appeal of these products among young adults who use JUUL. Conversely, decreasing the available nicotine content of JUUL does not appear to impact the product’s appeal. Moreover, findings from these studies serve as validation of our novel, controlled-puff, concurrent choice task, which can be utilized to evaluate the relative reinforcement of ENDS products with varying characteristics.

Perhaps not surprisingly, participants in the Flavor Study (i.e., comparing preferred versus non-preferred flavor, all 5% nicotine content pods) rated their preferred flavored pod significantly more favorably than the non-preferred pod on a number of subjective effects items (St Helen, Dempsey, Havel, Jacob, & Benowitz, 2017). However, participants also rated the non-preferred pod as being greater in terms of the ability to reduce craving for ENDS as compared to their preferred pod. Though this finding may be somewhat counterintuitive, we postulate that, given that the non-preferred flavor pod was rated significantly lower in terms of pleasant sensations, liking, and wanting more, participants craved continued vaping to a lesser degree following use of the non-preferred flavor pod. Participants in the Flavor Study also earned a significantly greater proportion of puffs from their preferred-flavor pod than from the non-preferred tobacco-flavored pod, despite the escalating amount of effort required to earn puffs from the preferred pod. Given the apparent appealing and reinforcing nature of preferred-flavor pods, coupled with the observed dislike of the tobacco-flavored pods, it is possible that regulations that would restrict the available ENDS flavors may result in increased effort expenditure to obtain illicit flavored ENDS products or non-JUUL ends (e.g., disposables such as Puff Bar) and/or result in the use of other tobacco products such as combusted cigarettes (Leventhal et al., 2020; Pacek et al., 2019), which have a significantly greater relative risk profile (Goniewicz et al., 2018).

It is worth noting that since the completion of the present studies, the FDA has enacted an enforcement policy that serves to prohibit the sale of flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes—with the exception of tobacco and menthol flavors (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2020). Consequently, the preferred-flavor pods that were utilized in these studies are no longer available on the market. However, the findings are still highly relevant, as in addition to the permitted tobacco flavor, JUUL pods remain available for purchase in menthol flavor (JUUL, 2021), which could be subject to future FDA regulation. Moreover, findings may be relevant to a number of other ENDS devices that remain on the market, including refillable pod mod devices (e.g., Suorin Air, SMOK Novo) and non-JUUL branded pods that are compatible with JUUL devices and intended to be refilled with the e-liquid of the user’s choosing. Both such examples are not currently regulated under the aforementioned FDA flavor enforcement policy.

In contrast, participants in the Nicotine Study (i.e., comparing 5% versus 3% nicotine content pods, all in participants’ preferred flavor) rated their preferred 5% nicotine content pod and the 3% nicotine content non-preferred pods as being similar on all subjective effects items. Most notably, participants rated both the 5% and 3% pods as being equally high in nicotine. Collectively, these findings suggest that participants find these JUUL pods to be equally appealing and satisfying, regardless of nicotine content. These findings can be contrasted with those of a study Phillips-Waller and colleagues (Phillips-Waller et al., 2021), wherein the European Union version of JUUL (20 mg/mL nicotine content) was perceived to less effectively relieve urges to smoke and perceived to contain less nicotine than the 5% nicotine content JUUL that is available in the U.S. When considering the lack of differences in participant perceptions of pod nicotine content, two factors may potentially be at play. It is possible that the nicotine contents may truly be indistinguishable from one another, particularly given the high nicotine content of both pods: the 5% nicotine content pods contain 59 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter of liquid (mg/mL) whereas the 3% pods contain 35 mg/mL (JUUL, 2019). It is possible that participants would be able to better discriminate between the 5% nicotine content pods and pods with a lower nicotine content, as in prior research (Phillips-Waller et al., 2021). Alternately, it is possible that the acute nature of exposure to each of the JUUL pods during the course of this study made distinguishing between the two nicotine contents difficult, and that the ability to discriminate the two nicotine contents may increase with greater use of the two products. Participants also worked to earn significantly more puffs from the non-preferred 3% nicotine content pod than from the preferred 5% pod. These findings may owe, at least in part, to the non-preferred pod requiring relatively less effort (i.e., button clicks) to obtain as compared to the preferred pod. This, coupled with the previously noted possibility that participants find both the 3% and 5% pods to be equally satisfying, may explain the discrepant use. Last, it is also possible that 4 puffs were not sufficient to allow participants to accurately discriminate between the two nicotine contents; prior work has utilized a greater number (i.e., 8-15) of puffs during product sampling (Perkins, Herb, & Karelitz, 2019; St Helen et al., 2017; St Helen, Shahid, Chu, & Benowitz, 2018).

The novel method of delivering fixed doses of ENDS vapor—validated via the present studies—can be utilized in conjunction with traditional behavioral economics research methods for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacies and substitutability of tobacco products (Grace, Kivell, & Laugesen, 2015; Johnson, Johnson, Rass, & Pacek, 2017; Rusted, Mackee, Williams, & Willner, 1998). The ENDS vapor delivery methodology described herein is advantageous, given that behavioral economics methods can be complicated by the relative units of consumption of each tobacco product being compared. As the proxy of reinforcing value in purchase tasks is daily drug consumption, the unit of daily use is a critical variable (Bickel, Johnson, Koffarnus, MacKillop, & Murphy, 2014). Whereas the relevant daily unit for a product like combusted cigarettes (i.e., cigarettes smoked per day) is an established and easily identifiable metric, the relevant daily unit is currently unclear for ENDS. Though less of an issue in the present work wherein we compared two JUUL ENDS of varying characteristics, behavioral economics methods can also be complicated by the relative units of consumption of different tobacco products—particularly when assessing the substitutability of two different classes of products (e.g., combusted cigarettes vs. ENDS). In our paradigm, we constrained the amount of vapor that could be obtained in each trial, thus preventing confounds associated with allowing users to self-administer more of one product versus another. Given the complexities that are often inherent to behavioral economics research, our method presents an opportunity to assess and establish differences in the relative value of tobacco products that can be compared across products and product characteristics, as well as across studies and individuals.

The present studies have a number of limitations which should be noted. First, we acknowledge that the small sample sizes in these pilot studies likely limit statistical power. \ Across both studies, we were not able to conduct some common PRT-related analyses (e.g., breakpoint on the PRT button, switchover point) due to data not being orderly Perhaps in future work, with a larger sample size, we could have enough orderly data to justify running these analyses. Additionally, for both studies, we did not include a concurrent choice task in which the effort to obtain puffs from each product was equal (e.g., requiring 10 button clicks to earn puffs from either JUUL). Within the Nicotine study, we also did not include a nicotine-free or other lower (i.e., greater than zero but less than 3%) pod condition. Future work should incorporate conditions such as these. Additionally, future work should evaluate whether findings from this novel concurrent choice task correlate with or predict real world tobacco use behavior. Should this be supported, the choice task used in the present studies could be utilized to make predictions regarding the effects of potential tobacco product regulations. Future work should also evaluate additional tobacco products (e.g., other ENDS products, IQOS, of varying characteristics), as well as evaluate different product types against one another (e.g., combusted cigarettes versus ENDS), using this paradigm.

The U.S. FDA has the authority to regulate tobacco products, including characteristics of ENDS that affect the relative appeal and value of these products. Our findings suggest that, among young adults who use JUUL, restricting JUUL to tobacco flavors may decrease the appeal/positive subjective effects of these products. However, reducing JUUL nicotine content to 3% (from the conventional 5%) may not impact product appeal/subjective effects. Regulatory policies that have the potential to impact appeal and use of ENDS products—such as those evaluated in the present studies—are of import to both efforts that seek to reduce the incidence of use among young people and non-users as well as to issues surrounding the use of ENDS products by adults as a means of harm reduction. Additionally, our findings validate a novel methodology for delivering fixed doses of ENDS vapor within the context of a task aimed at assessing the relative reinforcement of ENDS products with varying characteristics. This methodology can be applied to assessing the relative reinforcing effects of a wide variety of tobacco products with varied characteristics.

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has the authority to regulate characteristics of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS). Such regulation has the potential to impact appeal and use of ENDS, products which may be utilized as harm reduction tools. Findings from the present studies suggest that restricting JUUL brand ENDS to tobacco flavor reduces the appeal of these products among young adults (age 18-25), while restricting the nicotine content to 3% (versus 5%) does not.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

Salary support for LRP was provided by NIDA grant K01DA043413. The funding source had no other role than financial support.

All authors have contributed significantly to the manuscript and have reviewed and approved of the final version.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, Conway KP, Borek N, Hyland A, & Villanti AC (2015). Flavored Tobacco Product Use Among US Youth Aged 12-17 Years, 2013-2014. JAMA, 314(17), 1871–1873. 10.1001/jama.2015.13802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Strasser AA, & Wileyto EP (2016). The impact of flavoring on the rewarding and reinforcing value of e-cigarettes with nicotine among young adult smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 166, 263–267. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, & Murphy JG (2014). The Behavioral Economics of Substance Use Disorders: Reinforcement Pathologies and Their Repair. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 641–677. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckell J, Marti J, & Sindelar JL (2017). Should flavors be banned in e-cigarettes? Evidence on adult smokers and recent quitters from a discrete choice experiment. NBER Working Paper Series, Working paper 23865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckell John, Marti J, & Sindelar JL (2018). Should flavours be banned in cigarettes and e-cigarettes? Evidence on adult smokers and recent quitters from a discrete choice experiment. Tobacco Control, tobaccocontrol-2017-054165. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-054165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, Glover M, Lin R, & Laugesen M (2010). Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: Randomised cross-over trial. Tobacco Control, 19(2), 98–103. 10.1136/tc.2009.031567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Baker CL, Merikle E, Olufade AO, & Gilbert DG (2007). Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors, 32(5), 912–923. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney MK, Gowin M, & Wann TF (2016). Electronic Cigarette Use in Straight-to-Work Young Adults. American Journal of Health Behavior, 40(2), 268–279. 10.5993/AJHB.40.2.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Harrell MB, & Perry CL (2016). A Qualitative Approach to Understanding Real-World Electronic Cigarette Use: Implications for Measurement and Regulation. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E07. 10.5888/pcd13.150502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, & Rossi JS (1991). The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(2), 295–304. 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AT, Henderson KC, Geier A, Weaver SR, Spears CA, Ashley DL, … Pechacek TF (2020). What Motivates Smokers to Switch to ENDS? A Qualitative Study of Perceptions and Use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23). 10.3390/ijerph17238865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food and Drug Administration. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act; Restrictions on the Sale and Distribution of Tobacco Products and Required Warning Statements for Tobacco Products. , (2016). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Veldheer S, Yingst J, Hrabovsky S, Wilson SJ, Nichols TT, & Eissenberg T (2015). Development of a Questionnaire for Assessing Dependence on Electronic Cigarettes Among a Large Sample of Ex-Smoking E-cigarette Users. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 17(2), 186–192. 10.1093/ntr/ntu204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson NI, Kirkpatrick MG, Barrington-Trimis JL, Pang RD, McBeth JF, Pentz MA, … Leventhal AM (2016). Effects of sweet flavorings and nicotine on the appeal and sensory properties of e-cigarettes among young adult vapers: Application of a novel methodology. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 168, 176–180. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.09.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, Blount BC, Caldwell KL, Feng J, … Hyland AJ (2018). Comparison of Nicotine and Toxicant Exposure in Users of Electronic Cigarettes and Combustible Cigarettes. JAMA Network Open, 1(8), e185937. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace RC, Kivell BM, & Laugesen M (2015). Estimating cross-price elasticity of e-cigarettes using a simulated demand procedure. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 17(5), 592–598. 10.1093/ntr/ntu268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell MB, Weaver SR, Loukas A, Creamer M, Marti CN, Jackson CD, … Eriksen MP (2017). Flavored e-cigarette use: Characterizing youth, young adult, and adult users. Preventive Medicine Reports, 5, 33–40. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Vogel RI, Severson HH, Jensen JA, & O’Connor RJ (2016). Perceived Health Risks of Snus and Medicinal Nicotine Products. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 18(5), 794–800. 10.1093/ntr/ntv200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerström KO (1991). The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Heil SH, Sigmon SC, Tidey JW, Gaalema DE, Hughes JR, … Tursi L (2017). Addiction Potential of Cigarettes With Reduced Nicotine Content in Populations With Psychiatric Disorders and Other Vulnerabilities to Tobacco Addiction. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(10), 1056–1064. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Johnson PS, Rass O, & Pacek LR (2017). Behavioral economic substitutability of e-cigarettes, tobacco cigarettes, and nicotine gum. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 31(7), 851–860. 10.1177/0269881117711921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUUL. (2019). How much nicotine is in a JUULpod? Retrieved July 9, 2019, from JUUL USA website: https://support.juul.com/hc/en-us/articles/360026223453-How-much-nicotine-is-in-a-JUULpod-

- JUUL. (2021). Retrieved from JUUL Shop website: https://www.juul.com/shop

- Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, & Krishnan-Sarin S (2015). Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 17(7), 847–854. 10.1093/ntr/ntu257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Green BG, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Jatlow P, Gueorguieva R, … O’Malley SS (2017). Studying the interactive effects of menthol and nicotine among youth: An examination using e-cigarettes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 193–199. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Mason TB, Cwalina SN, Whitted L, Anderson M, & Callahan C (2020). Flavor and Nicotine Effects on E-cigarette Appeal in Young Adults: Moderation by Reason for Vaping. American Journal of Health Behavior, 44(5), 732–743. 10.5993/AJHB.44.5.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Rose JE, & Behm F (1989). Controlling puff volume without disrupting smoking topography. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 21(3), 383–386. 10.3758/BF03202801 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald EA, & Ling PM (2015). One of several “toys” for smoking: Young adult experiences with electronic cigarettes in New York City. Tobacco Control, 24(6), 588–593. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier E, Wahlquist AE, Heckman BW, Cummings KM, Froeliger B, & Carpenter MJ (2017). A Pilot Randomized Crossover Trial of Electronic Cigarette Sampling Among Smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 19(2), 176–182. 10.1093/ntr/ntw157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek Lauren R., Joseph McClernon F, Denlinger-Apte RL, Mercincavage M, Strasser AA, Dermody SS, … Donny EC (2018). Perceived nicotine content of reduced nicotine content cigarettes is a correlate of perceived health risks. Tobacco Control, 27(4), 420–426. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek Lauren R, Villanti AC, & Mcclernon FJ (2019). Not Quite the Rule, But No Longer the Exception: Multiple Tobacco Product Use and Implications for Treatment, Research, and Regulation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 10.1093/ntr/ntz221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek Lauren R., Wiley JL, & Joseph McClernon F (2018). A Conceptual Framework for Understanding Multiple Tobacco Product Use and the Impact of Regulatory Action. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 10.1093/ntr/ntyl29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Oliver JA, & McClernon FJ (2018). What would you do if… ?: Analysis of young adult dual users’ anticipated responses to hypothetical e-cigarette market restrictions. Presented at the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Pacek LR, Rass O, Sweitzer MM, Oliver JA, & McClernon FJ (2019). Young adult dual combusted cigarette and e-cigarette users’ anticipated responses to hypothetical e-cigarette market restrictions. Substance Use & Misuse, 54(12), 2033–2042. 10.1080/10826084.2019.1626435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Davis KC, Cox S, Bradfield B, King BA, Shafer P, … Bunnell R (2016). Reasons for current E-cigarette use among U.S. adults. Preventive Medicine, 93, 14–20. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Herb T, & Karelitz JL (2019). Discrimination of nicotine content in electronic cigarettes. Addictive Behaviors, 91, 106–111. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, & Michael VC (2017). Effects of nicotine versus placebo e-cigarette use on symptom relief during initial tobacco abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 25(4), 249–254. 10.1037/pha0000134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips-Waller A, Przulj D, Smith KM, Pesola F, & Hajek P (2021). Nicotine delivery and user reactions to Juul EU (20 mg/ml) compared with Juul US (59 mg/ml), cigarettes and other e-cigarette products. Psychopharmacology, 238(3), 825–831. 10.1007/s00213-020-05734-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Herzog TA, Muranaka N, & Fagan P (2015). Young adult e-cigarette users’ reasons for liking and not liking e-cigarettes: A qualitative study. Psychology & Health, 30(12), 1450–1469. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1061129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramôa CP, Hiler MM, Spindle TR, Lopez AA, Karaoghlanian N, Lipato T, … Eissenberg T (2016). Electronic cigarette nicotine delivery can exceed that of combustible cigarettes: A preliminary report. Tobacco Control, 25(e1), e6–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosbrook K, & Green BG (2016). Sensory Effects of Menthol and Nicotine in an E-Cigarette. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 18(7), 1588–1595. 10.1093/ntr/ntw019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusted JM, Mackee A, Williams R, & Willner P (1998). Deprivation state but not nicotine content of the cigarette affects responding by smokers on a progressive ratio task. Psychopharmacology, 140(4), 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Francisco Department of Public Health. (2018). Flavored Tobacco. Retrieved from https://www.sfdph.org/dph/default.asp

- Helen G, Dempsey DA, Havel CM, Jacob P, & Benowitz NL (2017). Impact of e-liquid flavors on nicotine intake and pharmacology of e-cigarettes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 178, 391–398. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helen G, Shahid M, Chu S, & Benowitz NL (2018). Impact of e-liquid flavors on e-cigarette vaping behavior. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 189, 42–48. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.04.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Garcia R, Cruz TB, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Pentz MA, & Unger JB (2014). Consumers’ perceptions of vape shops in Southern California: An analysis of online Yelp reviews. Tobacco Induced Diseases, 12(1), 22. 10.1186/s12971-014-0022-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truth Initiative. (2019). E-cigarettes: Facts, stats and regulations. Retrieved from https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/e-cigarettes-facts-stats-and-regulations

- Tsai J, Walton K, Coleman BN, Sharapova SR, Johnson SE, Kennedy SM, & Caraballo RS (2018). Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Use Among Middle and High School Students—National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(6), 196–200. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6706a5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng T-Y, Krebs P, Schoenthaler A, Wong S, Sherman S, Gonzalez M, … Shelley D (2017). Combining Text Messaging and Telephone Counseling to Increase Varenicline Adherence and Smoking Abstinence Among Cigarette Smokers Living with HIV: A Randomized Controlled Study. AIDS and Behavior, 21(7), 1964–1974. 10.1007/s10461-016-1538-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Congress. Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Federal Reform Act. , Pub. L. No. Pub. L. No. 111-31 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2020). FDA finalizes enforcement policy on unauthorized flavored cartridge-based e-cigarettes that appeal to children, including fruit and mint. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- Yang Y, Lindblom EN, Salloum RG, & Ward KD (2020). The impact of a comprehensive tobacco product flavor ban in San Francisco among young adults. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 11, 100273. 10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.