Abstract

Elder mistreatment is common and has serious consequences. The emergency department (ED) may provide a unique opportunity to detect this mistreatment, with social workers often asked to take the lead in assessment and intervention. Despite this, social workers may feel ill-equipped to conduct assessments for potential mistreatment, due in part to a lack of education and training. As a result, the authors created the Emergency Department Elder Mistreatment Assessment Tool for Social Workers (ED-EMATS) using a multiphase, modified Delphi technique with a national group of experts. This tool consists of both an initial and comprehensive component, with 11 and 17 items, respectively. To our knowledge, this represents the first elder abuse assessment tool for social workers designed specifically for use in the ED. The hope is that the ED-EMATS will increase the confidence of ED social workers in assessing for elder mistreatment and help ensure standardization between professionals.

Keywords: assessment, elder abuse, emergency department, hospitals

Elder mistreatment is an important but underrecognized social issue. Elder mistreatment is often referred to as elder abuse, which is defined as “a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate actions, which causes harm, risk of harm, or distress to [an older adult]” (New York City Elder Abuse Center, n.d., para. 1). Elder mistreatment is perpetrated by a person in a position of trust or by someone who targets an older adult based on age or disability (National Research Council [NRC], 2003). It includes physical abuse, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, financial exploitation, and neglect, with many victims experiencing multiple types of mistreatment concurrently (NRC, 2003; U.S. Department of Justice and Department of Health and Human Services, 2014).

Elder mistreatment is common, affecting approximately 10 percent of community-dwelling older adults each year (Acierno et al., 2010; Lachs & Pillemer, 2004; NRC, 2003; Pillemer, Burnes, Riffin, & Lachs, 2016). This mistreatment often has serious consequences, including increased mortality (Lachs & Pillemer, 2015; Lachs, Williams, O'Brien, Pillemer, & Charlson, 1998), hospitalization (Dong & Simon, 2013b), and nursing home placement (Dong & Simon, 2013a; Lachs, Williams, O'Brien, & Pillemer, 2002). Elder mistreatment is also associated with increased risk of depression and exacerbation of chronic illness (Dyer, Pavlik, Murphy, & Hyman, 2000). Despite the high prevalence and severity, only one in 24 cases are recognized and reported to authorities (Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, and New York City Department for the Aging, 2012). The vast majority of these victims remain unidentified (Burnes, Acierno, & Hernandez-Tejada, 2018).

A hospital emergency department (ED) visit provides an important opportunity to improve elder mistreatment detection (Fulmer, Paveza, Abraham, & Fairchild, 2000) and to initiate intervention. An ED presentation for acute injury or illness may represent the only time a mistreated older adult ever leaves the home (Bond & Butler, 2013). Although elder mistreatment identification in the ED is currently infrequent (Rosen, Hargarten, Flomenbaum, & Platts-Mills, 2016), the ED already plays an essential role in identifying and intervening in cases of child abuse (Hochstadt & Harwicke, 1985; Kistin, Tien, Bauchner, Parker, & Leventhal, 2010) and intimate partner violence (IPV) (Choo et al., 2015; Rhodes et al., 2015).

In EDs that have a social worker as part of the clinical team, this social worker may be expected to take the lead in assessing for potential elder mistreatment and initiating interventions for victims. The value of social workers as part of the ED multidisciplinary care team, particularly for older adult patients, is increasingly recognized in this setting (Auerbach & Mason, 2010; Hamilton et al., 2015). Despite this, many ED and hospital-based social workers lack training for or experience with comprehensive assessment for elder mistreatment and are unclear about their responsibilities (Felton & Polowy, 2015). In contrast to child abuse and IPV, hospitals do not routinely offer elder mistreatment training to social workers. Although the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) has developed elder justice curriculum modules for social work schools, preprofessional social workers have little knowledge of elder abuse (CSWE, 2015; Policastro & Payne, 2014). Information about state-mandated training for social workers is not readily available, but anecdotal evidence suggests that this training is uncommon, even while social workers are mandated reporters in most states. Therefore, many ED social workers are unsure how to approach an assessment for elder mistreatment and have little guidance to assist them.

An understanding of the need to increase identification of elder mistreatment in the ED has led to a new focus on improving recognition by medical professionals in this setting. This includes additional training on both warning signs and risk factors, and consideration of implementation of a brief universal or targeted ED screening (Rosen, Stern, Elman, & Mulcare, 2018). As a result, it is likely that many more cases of suspected elder mistreatment will be referred to ED social workers for assessment.

To our knowledge, no tools to assist ED-based social workers with elder mistreatment assessment have been developed. Therefore our goal was to create an elder mistreatment assessment tool for social workers in the ED.

METHOD

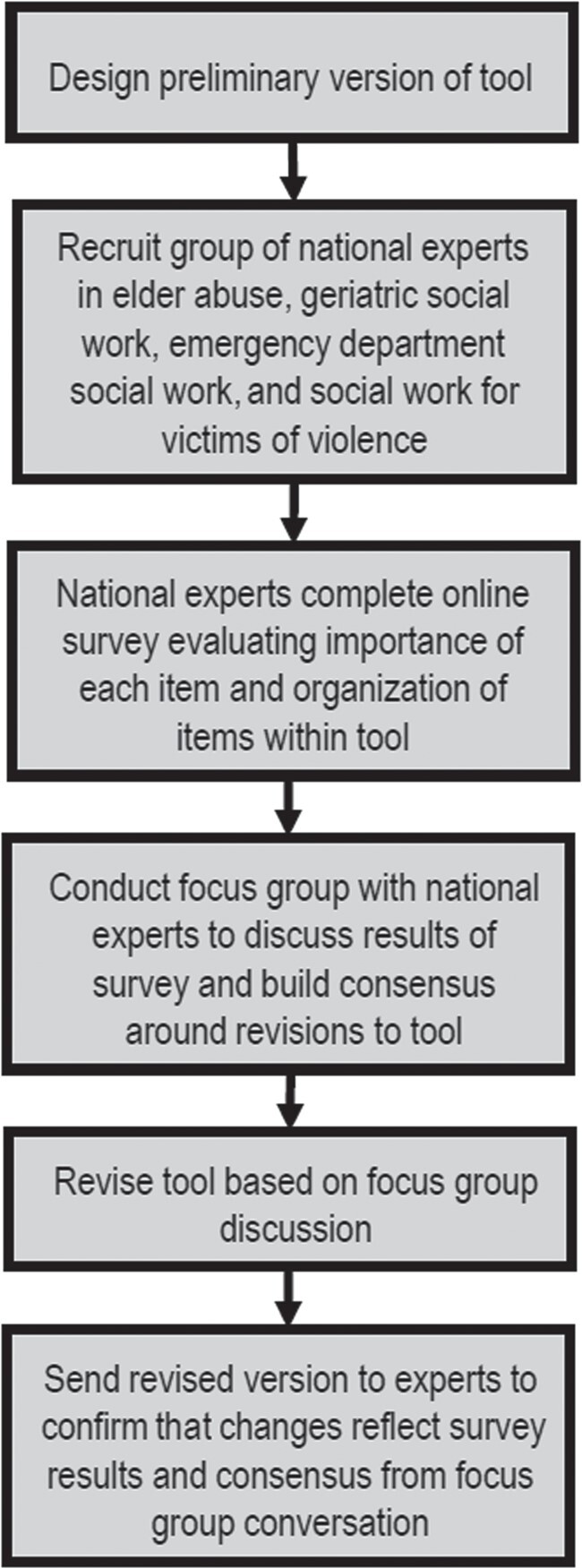

To design our ED social work assessment for elder abuse, we used a modified Delphi technique (Custer, Scarcella, & Stewart, 1999). This multistep process included an examination of existing assessment and screening tools, design of a preliminary version of the assessment tool, initial review by an expert panel with individual feedback via survey, expert panel focus group discussion, integration of panel recommendations, and final review of the revised version by the expert panel. The steps of this process are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Summary of Multistep Process Using Modified Delphi Technique to Develop Emergency Department Elder Mistreatment Assessment Tool for Social Workers

Examination of Existing Assessment and Screening Tools

We conducted a comprehensive examination of existing elder abuse assessment and screening tools for professionals in different disciplines. We identified existing tools using several recent systematic and comprehensive reviews (Beach, Carpenter, Rosen, Sharps, & Gelles, 2016; Fulmer, Guadagno, Bitondo Dyer, & Connolly, 2004; Gallione et al., 2017; National Center on Elder Abuse [NCEA], 2017; Phelan, 2012; Worrilow & Barraco, 2015). The reviews are shown in more detail in Table 1. We also collaborated with NCEA (2017), who had prepared a Research to Practice report on the topic. We evaluated four tools for elder abuse assessment and 14 published tools for elder abuse screening. For tools that were not readily available, we contacted the authors to receive a copy. In addition, with the permission of the creators, we examined a screening tool designed for ED use that had not yet been published but has been subsequently (Platts-Mills et al., 2018). Table 2 describes the assessments and tools we examined.

Table 1.

Published Reviews of Elder Abuse Screening Tools and Assessments

| Systematic | Databases Used | Number of | Time Period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, Year | Review | in Review | Results | Covered | Summary of Results |

| Fulmer, Guadagno, Bitondo Dyer, & Connolly, 2004 | No | Not disclosed | 11 | 1981–2000 | • Consensus must be achieved to determine what constitutes an appropriate/acceptable screen/assessment• Focus should be on developing instruments for rapid assessment and longer diagnostic assessments• Much need for additional research |

| Gallione et al., 2017 | Yes | MEDLINE, Cochrane, EMBASE, Scopus | 11 | 1980–2015 | • No tool identified as a gold standard• Many tools require validity and reliability testing |

| National Center on Elder Abuse, 2017 | No | Not disclosed | 17 | 1980–2016 | • There is no gold standard for elder abuse screening• Many screening tools exist, designed primarily for health care providers• Not all tools have psychometrics |

| Worrilow & Barraco, 2015 | No | MEDLINE | 9 | 1991–2015 | • Most tools were not designed for the emergency department• More research should be done to standardize criteria for evaluation and diagnosis of elder abuse |

Table 2.

Published Elder Abuse Screening Tools and Assessments

| Screening Tools and | Domains | Social Worker | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive Assessments | Citation | Setting | Addressed | as Authora |

| Comprehensive Assessments | ||||

| Case Detection of Abused Elderly Patients | (Rathbone-McCuan & Voyles, 1982) | Clinical setting | All | Yes |

| Assessment of Elder Mistreatment: Issues and Considerations. Elder Mistreatment Guidelines for Health Care Profession: Detection, Assessment and Intervention | (Ansell & Breckman, 1988) | Clinical setting | All | Yes |

| Written protocol for identification and assessment in Strategies for Helping Victims of Elder Mistreatment | (Breckman & Adelman, 1988) | Any, but has medical component for clinical setting | All | Yes |

| Harborview Medical Center elder abuse diagnostic and intervention protocol in Elder Abuse and Neglect: Causes, Diagnosis, and Intervention Strategies | (Quinn & Tomita, 1997) | Any, but has medical component for clinical setting | All | Yes |

| Screening Tools | ||||

| Screening Protocol for Identification of Abuse and Neglect of the Elderly | (Johnson, 1981) | Not specified | Physical, verbal/psychological, financial, neglect | No |

| Health, Attitudes Toward Aging, Living Arrangements, and Finances (HALF) Assessment | (Ferguson & Beck, 1983) | Health services setting | All, but is observational | No |

| Hwalek-Sengstock Elder Abuse Screening Test (H-S/EAST) | (Neale, Hwalek, Scott, Sengstock, & Stahl, 1991) | Health and social services agencies | All | Yes |

| Brief Abuse Screen for the Elderly (BASE) | (Reis, Nahmiash, & Shrier, 1993) | Clinical setting | All, but is observational | Yes |

| Caregiver Abuse Screen (CASE) | (Reis & Nahmiash, 1995) | Community-based health and social services agencies | Physical, verbal/psychological, neglect | Yes |

| Indicators of Abuse (IOA) | (Cohen, Halevi-Levin, Gagin, & Friedman, 2006; Reis & Nahmiash, 1998) | By a professional, following a home visit | All, but is observational | Yes |

| Screening Tools and Referral Protocol for Stopping Abuse Against Older Ohioans | (Bass, Anetzberger, Ejaz, & Nagpaul, 2001) | Not specified | Physical, verbal/psychological, financial, neglect | Yes |

| Vulnerability to Abuse Screening Scale (VASS) | (Schofield, Reynolds, Mishra, Powers, & Dobson, 2002) | Mailed to clients | All | No |

| Elder Assessment Instrument (EAI) | (Fulmer, 2003) | Clinical setting | Physical, financial, neglect | No |

| Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (EASI) | (Yaffe, Wolfson, Lithwick, & Weiss, 2008) | Family practice ambulatory care | All | Yes |

| Elder Abuse and Neglect Risk Assessment Tool | (Cohen, Halevi-Levin, Perlozki, Gagaeien, & Freedman, 2010) | Not specified | Physical, financial, neglect | Yes |

| Older Adult Financial Exploitation Measure (OAFEM) | (Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Langley, & Wilber, 2010) | Social services agencies | Financial | Yes |

| Geriatrics Mistreatment Scale (GMS) | (Giraldo-Rodriguez & Rosas-Carrasco, 2013) | Clinical setting | All | No |

| ED Senior AID (Emergency Department Senior Abuse Identification) Tool | (Platts-Mills et al., 2018) | Emergency setting | All | No |

Design team included author with social work background.

Design of Preliminary Version

Two authors (Alyssa Elman [AE] and Tony Rosen [TR]) initially comprehensively examined each of the existing published tools. We assessed the level of evidence supporting each tool, including whether it had been validated, and, if so, how applicable the setting in which the validation occurred was to ED social work. We used in-person meetings to qualitatively analyze and categorize the individual items from all tools to identify relevant domains for inclusion. We then built a preliminary version of our ED social work assessment tool based on the themes that emerged. We preferentially included items from validated scales when possible while attempting to be mindful of the unique challenges associated with conducting a social work assessment in an ED setting. This was developed into a preliminary version of the tool through several team meetings, where it was revised iteratively through a consensus process. Team members included three social workers with expertise in acute care, geriatrics, family violence, and elder abuse; three emergency physicians with additional training in geriatrics and a focus in elder mistreatment; a geriatrician with extensive elder mistreatment research and leadership experience; and an epidemiologist focusing on acute care and public health and sociomedical issues in older adults. Attempting to balance the need to ensure assessment for multiple types of mistreatment with a sensitivity to the omnipresent time pressure in an ED, we divided the preliminary version of the tool into a brief initial assessment and then a comprehensive assessment to be performed if concern existed after completing the former. In the preliminary version, the initial part of the tool had 14 items and the comprehensive had 24 items.

Modified Delphi: Overview

We used a modified Delphi approach to incorporate the input of a panel of experts to refine the tool. The Delphi method is well established and has been used extensively in health care and other sectors to reliably develop consensus. This method, initially described by the RAND Corporation (Dalkey & Helmer, 1963), is an iterative process that uses a systematic progression of voting by an expert panel to build consensus around a research question about which little is known (Eubank et al., 2016; Hsu & Sandford, 2007). The original Delphi method developed at RAND did not include a face-to-face meeting of experts; however, the Delphi method has been “modified” to include the opportunity for interaction between experts (Gustafson, Shukla, Delbecq, & Walster, 1973). Previous studies have shown that this modified Delphi approach can be better than the traditional Delphi method (Eubank et al., 2016; Graefe & Armstrong, 2011; Gustafson et al., 1973). In our study, we used this modified Delphi approach, which has also been successfully used for elder abuse risk indicators and screening questions (Erlingsson, Carlson, & Saveman, 2003), roles and responsibility in a multidisciplinary elder abuse intervention (Du Mont, Kosa, Macdonald, Elliot, & Yaffe, 2015), skills-based competencies for forensic nurse examiners providing elder abuse care (Du Mont, Kosa, Macdonald, Elliot, & Yaffe, 2016), and ED palliative care screening (George et al., 2015).

Modified Delphi: Expert Panel Recruitment

We identified experts to participate in this panel based on our experience in the field and on recommendations from colleagues. Specifically, we described our project to the National Collaboratory to Address Elder Mistreatment and asked fellow members to suggest social work experts. The panelists included professional social workers with experience in elder abuse and sociomedical issues among older adults. Participants had expertise in family violence, ED social work, outpatient geriatrics, and palliative care. Several participants have worked closely with law enforcement and criminal justice, and many have participated in multidisciplinary community-based teams that address challenging elder abuse cases. Details about the credentials and relevant experience of the expert panel can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Expert Panel Characteristics

| Experience | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | |||||||

| Total Years | Years of Elder | Years of | Years of Domestic | Emergency | |||

| Participant | Reason for | Credentials/ | of Clinical | Abuse–Focused | Geriatric | Violence Social | Department |

| # | Selection | Licensure | Social Work | Work | Social Work | Work | Social Work |

| 1 | Elder abuse expertise | LCSW, MSW | 38 | 20 | |||

| 2 | Elder abuse expertise | LCSW, MSW, PhD | 36 | 24 | 36 | 12 | 2.5 |

| 3 | Elder abuse expertise | LCSW, MSW | 12 | 6 | |||

| 4 | Geriatric expertise | LCSW, MSW | 25 | 23 | |||

| 5 | Geriatric expertise | LCSW, MSW | 16 | 16 | |||

| 6 | Geriatric expertise | LCSW, MSW | 10 | 10 | 10 | ||

| 7 | Geriatric expertise | LMSW, MSW | 4 | 2 | |||

| 8 | Domestic violence expertise | LCSW, MSW | 19 | 3 | 5 | ||

| 9 | Domestic violence expertise | LCSW, MSW | 15 | 7 | |||

| 10 | Emergency department expertise | LCSW, MSW | 26 | 20 | |||

Modified Delphi: Initial Independent Review and Survey

Panel members were sent the preliminary version of the assessment tool and the 18 existing tools on which it was based. In this first phase, each member of the panel reviewed the preliminary tool individually. They were asked to make recommendations for modifications using an online survey.

The survey asked participants to indicate how critical each question was (on a scale of 0 to 8) and whether each question belonged in the initial or comprehensive part of the assessment or should not be included at all. We also asked if any items should be reworded for clarity. Panelists were sent a link to the survey Web page within the e-mail and used an online interface to enter their answers. The survey was designed and the results stored using Typeform (Barcelona, Spain). The entire survey is available on request from the first author.

Results were analyzed to identify the level of consensus for each item and to determine which items needed additional discussion. Based on survey results, consensus did not exist among experts for 13 items from the preliminary version of the tool. Panelists did not agree about whether six of the 13 items should be included in the tool and whether an additional seven belonged in the brief initial section or the comprehensive section.

Modified Delphi: Focus Group with Expert Panel

A focus group was conducted in April 2018 with all expert panelists participating in person or via telephone to discuss the tool and build consensus. Qualitative approaches are often helpful to explore topics that lack significant previous research and may not lend themselves to quantitative analysis (Green & Britten, 1998; Krumholz, Bradley, & Curry, 2013; Pope & Mays, 1995). Author TR has formal training in qualitative research and has conducted successful studies with such approaches in the past. This focus group was moderated by several of the authors (AE, Sarah Rosselli [SR], Sunday Clark, Risa Breckman, and TR). A summary of the survey results was sent to all panelists in advance of the focus group. The focus group guide incorporated these results and included questions such as “Should any of the questions be removed entirely?” and “Would you reword any of the questions for clarity, completeness, or acceptability?” (The entire focus group guide is available on request from the first author.) We used the focus group to allow the expert panel to discuss, in detail, all questions for which initial written responses differed substantially. Through this focus group, consensus was arrived at for all questions. The focus group was audio-recorded and professionally transcribed. Transcripts were then reviewed in detail and discussed in depth by authors AE, SR, and TR to identify themes and review items for consensus.

Modified Delphi: Final Revisions and Panel Rereview

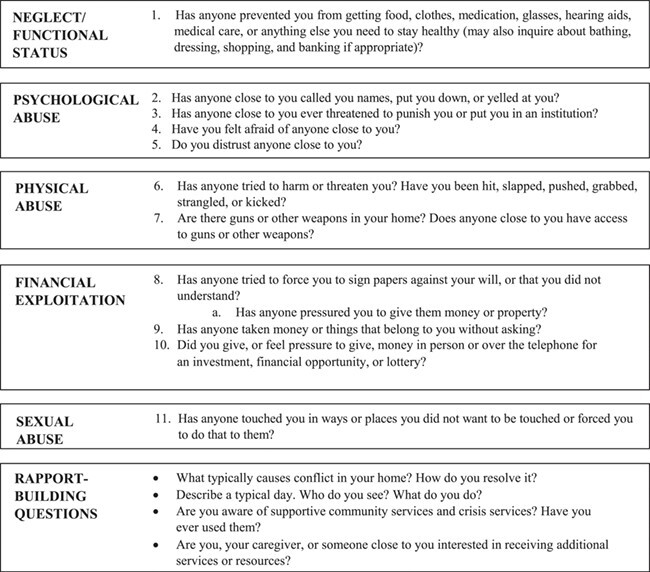

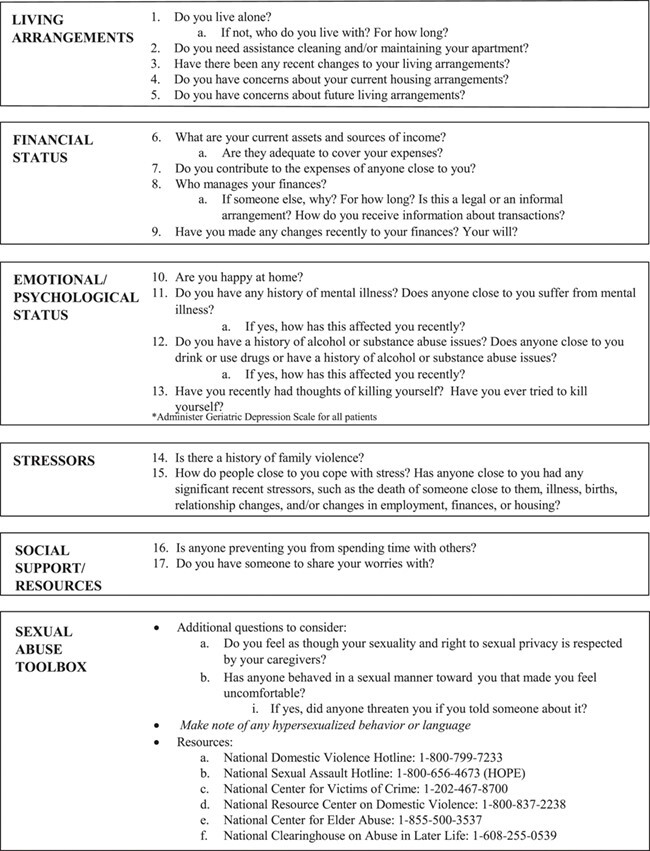

Based on feedback from the focus group, we made revisions to the tool. Per suggestions from the expert panel, two toolboxes were incorporated into the assessment: (1) a rapport-building toolbox for the initial assessment and (2) a sexual assault toolbox for the comprehensive section. Items for the toolboxes were developed during the focus group.

Seven items were removed entirely, primarily because they would likely be asked in a standard social work assessment. One question was added to the initial tool and one question was moved from the initial section to the comprehensive section. Four questions were moved from the comprehensive section to the rapport-building toolbox. Many questions were rephrased for clarity and the order of questions was revised.

Before finalization, the revised version was sent to all expert panelists via e-mail to ensure that the changes reflected what had been discussed and to solicit any final comments.

NAME OF TOOL

The final versions of the tool, which we have named Emergency Department Elder Mistreatment Assessment Tool for Social Workers (ED-EMATS), are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The initial screening section (Figure 2) has 11 items and the comprehensive assessment section (Figure 3) has 17 items. We included rapport-building and sexual assault toolboxes. In our experience using the tool, the initial screening section takes five to 15 minutes to complete and the comprehensive follow-up takes 15 to 25 additional minutes to complete. Patient interactions vary in length based on their responses and the need to ask follow-up questions.

Figure 2.

Emergency Department Elder Mistreatment Assessment Tool for Social Workers (ED-EMATS)—Initial Assessment

Figure 3.

Emergency Department Elder Mistreatment Assessment Tool for Social Workers (ED-EMATS)—Comprehensive Evaluation

DISCUSSION

We have attempted to design an assessment tool specifically for use by social workers in the ED setting. Although brief screening instruments exist for varied disciplines, including one currently intended for use by ED medical providers and nurses (Platts-Mills et al., 2018) and one for health care professionals in the community (Bomba, 2006), which social workers may use, previously published tools we reviewed were not developed expressly for social workers and case managers. ED social workers have previously indicated that they believe many cases of elder abuse are likely missed, in part because of a lack assessment tools that are available for use in the ED (Rosen, Stern, Mulcare, et al., 2018). Our goal is to provide an additional framework that may be of assistance to those already seasoned in practice and likewise develop a standardized approach for inexperienced social workers to feel more confident in conducting this assessment, especially in the absence of formal training. We believe that the ED-EMATS will increase the confidence of ED social workers in assessing for elder mistreatment and help ensure standardization between professionals.

The ED-EMATS may be added to electronic medical record to further assist ED social workers in appropriately assessing these vulnerable patients and accurately documenting the encounter. It may also be incorporated into regular ED and hospital social work and case manager trainings. In addition, it may serve as an element of an elder mistreatment curriculum that should be implemented in professional social work schools. We plan to test the efficacy of this tool qualitatively and quantitatively, including examining validity, reliability, and ease of use in a clinical setting. Doing so may allow us to compare it to existing tools. Our goal with the ED-EMATS tool, though, is not only to assist ED social workers in accurately identifying elder abuse, but also to give a structure for a comprehensive assessment to help determine appropriate next steps. We hope to test its ability to effectively fulfill this function as well.

We recognize that responses to many items in this tool may require additional probing. We have not provided guidance or advice for this, as we believe that this additional follow-up exploration is a core part of social work training. Also, we have not provided suggestions for interventions for patients identified as elder mistreatment victims or at risk. Available resources and appropriate next steps may differ between communities and based on the patients’ circumstances.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. We used a comprehensive qualitative review of existing tools to categorize items and identify domains to develop a preliminary version of our ED social work assessment tool. Although this is an established research technique, domains and their categorization may have been affected by the subjective way in which the tools were assessed by the research team. In addition, although we attempted to include items from validated tools when possible, given that most tools had not been previously validated, many items in the tool we developed had not been formally validated. Another limitation is that we chose expert panelists based on our experience in the field and on recommendations from colleagues rather than using objective criteria. We attempted to mitigate this by inviting social workers with various experiences and from different geographical regions, nearly all of whom agreed to participate. Also, our expert panel was relatively small. The small size of the panel is partially because limited expertise about elder mistreatment currently exists among social work professionals. Notably, it is unclear how many experts are needed for the Delphi process (Smith, Clark, Kapoor, & Handler, 2012), but it is possible that our panel does not represent broad enough perspectives on the topic (Lerner et al., 2015). The goal of consensus may also have weakened the final tool, as panelists may have conformed to the majority opinion rather than disagreeing (Mukherjee et al., 2015). While moderating the focus group, we attempted to minimize this limitation by providing opportunities for everyone to share their perspective and explore concerns or differences of opinion in detail.

Conclusion

Through a rigorous modified Delphi process, we have developed the ED-EMATS, an ED social work assessment tool. We anticipate that it will standardize and improve the care social workers provide older adults in the ED. We believe it will become a useful part of an increased professional focus on assessing and initiating intervention for vulnerable victims of elder mistreatment in the ED and other settings.

Alyssa Elman, LMSW, is supervising social worker of the Vulnerable Elder Protection Team (VEPT), Department of Emergency Medicine, New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Sarah Rosselli, LCSW, is Victim Intervention Program social worker, Department of Emergency Medicine, New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. David Burnes, PhD, is associate professor and associate dean, University of Toronto, Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work. Sunday Clark, ScD, is associate professor of epidemiology research in emergency medicine and director of research, Department of Emergency Medicine, New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center; Michael E. Stern, MD, is associate professor of clinical emergency medicine and chief, geriatric emergency medicine; Veronica M. LoFaso, MD, is associate professor of medicine; and Mary R. Mulcare, MD, is assistant professor of clinical emergency medicine and director, undergraduate medical education for the Department of Emergency Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Risa Breckman, LCSW, is director, New York City Elder Abuse Center, Weill Cornell Medical College. Tony Rosen, MD, is assistant professor of emergency medicine and program director of VEPT, Department of Emergency Medicine, New York–Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Address correspondence to Alyssa Elman, Department of Emergency Medicine, New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, 525 E. 68th Street, New York, NY 10065; e-mail: ale2011@med.cornell.edu.

REFERENCES

- Acierno, R., Hernandez, M. A., Amstadter, A. B., Resnick, H. S., Steve, K., Muzzy, W., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, P., & Breckman, R. (1988). Assessment of elder mistreatment: Issues and considerations. Elder mistreatment guidelines for health care profession: Detection, assessment and intervention. New York: Mount Sinai/Victim Services Agency’s Elder Abuse Project. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, C., & Mason, S. E. (2010). The value of the presence of social work in emergency departments. Social Work in Health Care, 49, 314–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, D. M., Anetzberger, G. J., Ejaz, F. K., & Nagpaul, K. (2001). Screening tools and referral protocol for stopping abuse against older Ohioans: A guide for service providers. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 13(2), 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Beach, S. R., Carpenter, C. R., Rosen, T., Sharps, P., & Gelles, R. (2016). Screening and detection of elder abuse: Research opportunities and lessons learned from emergency geriatric care, intimate partner violence, and child abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 28(4–5), 185–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomba, P. A. (2006). Use of a single page elder abuse assessment and management tool: A practical clinician’s approach to identifying elder mistreatment. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 46(3–4), 103–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, M. C., & Butler, K. H. (2013). Elder abuse and neglect: Definitions, epidemiology, and approaches to emergency department screening. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 29, 257–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckman, R. S., & Adelman, R. D. (1988). Strategies for helping victims of elder mistreatment. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, D., Acierno, R., & Hernandez-Tejada, M. J. (2018). Help-seeking among victims of elder abuse: Findings from the National Elder Mistreatment Study. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 891–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo, E. K., Gottlieb, A. S., DeLuca, M., Tape, C., Colwell, L., & Zlotnick, C. (2015). Systematic review of ED-based intimate partner violence intervention research. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 16, 1037–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M., Halevi-Levin, S., Gagin, R., & Friedman, G. (2006). Development of a screening tool for identifying elderly people at risk of abuse by their caregivers. Journal of Aging and Health, 18, 660–685. doi: 10.1177/0898264306293257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M., Halevi-Levin, S., Perlozki, D., Gagaeien, R., & Freedman, G. (2010). Elder Abuse and Neglect–Risk Assessment Tool. Haifa, Israel: University of Haifa, Israel, in collaboration with JDC-ESHEL (Association for Planning and Development of Services for the Aged in Israel), Ministry of Social Affairs and Social Services, Ministry of Health, and the social services at local municipalities in Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, K. J., Iris, M., Ridings, J. W., Langley, K., & Wilber, K. H. (2010). Self-report measure of financial exploitation of older adults. Gerontologist, 50, 758–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council on Social Worker Education . (2015). Elder justice: Curriculum modules for MSW programs. Retrieved fromhttps://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Centers-Initiatives/Centers/Gero-Ed-Center/ElderJustice-CSWE-Gero-Ed.pdf.aspx

- Custer, R. L., Scarcella, J. A., & Stewart, B. R. (1999). The modified Delphi technique—A rotational modification. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 15(2), 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dalkey, N., & Helmer, O. (1963). An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Management Science, 9, 458–467. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X., & Simon, M. A. (2013a). Association between reported elder abuse and rates of admission to skilled nursing facilities: Findings from a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Gerontology, 59, 464–472. doi: 10.1159/000351338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X., & Simon, M. A. (2013b). Elder abuse as a risk factor for hospitalization in older persons. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173, 911–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Mont, J., Kosa, D., Macdonald, S., Elliot, S., & Yaffe, M. (2015). Determining possible professionals and respective roles and responsibilities for a model comprehensive elder abuse intervention: A Delphi consensus survey. PLOS One, 10(12), e0140760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Mont, J., Kosa, D., Macdonald, S., Elliot, S., & Yaffe, M. (2016). Development of skills-based competencies for forensic nurse examiners providing elder abuse care. BMJ Open, 6(2), e009690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer, C. B., Pavlik, V. N., Murphy, K. P., & Hyman, D. J. (2000). The high prevalence of depression and dementia in elder abuse or neglect. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48, 205–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlingsson, C. L., Carlson, S. L., & Saveman, B.-I. (2003). Elder abuse risk indicators and screening questions: Results from a literature search and a panel of experts from developed and developing countries. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 15(3–4), 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- Eubank, B. H., Mohtadi, N. G., Lafave, M. R., Wiley, J. P., Bois, A. J., Boorman, R. S., & Sheps, D. M. (2016). Using the modified Delphi method to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16(1), 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton, E. M., & Polowy, C. I. (2015). Social workers and elder abuse. Washington, DC: National Association of Social Workers. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, D., & Beck, C. (1983). HALF: A tool to assess elder abuse within the family. Geriatric Nursing, 4, 301–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, T. (2003). Elder abuse and neglect assessment. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 29(6), 4–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, T., Guadagno, L., Bitondo Dyer, C., & Connolly, M. T. (2004). Progress in elder abuse screening and assessment instruments. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52, 297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer, T., Paveza, G., Abraham, I., & Fairchild, S. (2000). Elder neglect assessment in the emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 26, 436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallione, C., Dal Molin, A., Cristina, F. V., Ferns, H., Mattioli, M., & Suardi, B. J. (2017). Screening tools for identification of elder abuse: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 2154–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, N., Barrett, N., McPeake, L., Goett, R., Anderson, K., & Baird, J. (2015). Content validation of a novel screening tool to identify emergency department patients with significant palliative care needs. Academic Emergency Medicine, 22, 823–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo-Rodriguez, L., & Rosas-Carrasco, O. (2013). Development and psychometric properties of the geriatric mistreatment scale. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 13, 466–474. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00894.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graefe, A., & Armstrong, J. S. (2011). Comparing face-to-face meetings, nominal groups, Delphi and prediction markets on an estimation task. International Journal of Forecasting, 27(1), 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J., & Britten, N. (1998). Qualitative research and evidence based medicine. BMJ, 316(7139), 1230–1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson, D. H., Shukla, R. K., Delbecq, A., & Walster, G. W. (1973). A comparative study of differences in subjective likelihood estimates made by individuals, interacting groups, Delphi groups, and nominal groups. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 9, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C., Ronda, L., Hwang, U., Abraham, G., Baumlin, K., Morano, B., et al. (2015). The evolving role of geriatric emergency department social work in the era of health care reform. Social Work in Health Care, 54, 849–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstadt, N. J., & Harwicke, N. J. (1985). How effective is the multidisciplinary approach? A follow-up study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 9, 365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-C., & Sandford, B. A. (2007). The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation, 12(10), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. (1981). Abuse of the elderly. Nurse Practitioner, 6(1), 29–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistin, C. J., Tien, I., Bauchner, H., Parker, V., & Leventhal, J. M. (2010). Factors that influence the effectiveness of child protection teams. Pediatrics, 126, 94–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz, H. M., Bradley, E. H., & Curry, L. A. (2013). Promoting publication of rigorous qualitative research. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 6, 133–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs, M. S., & Pillemer, K. (2004). Elder abuse. Lancet, 364(9441), 1263–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs, M. S., & Pillemer, K. A. (2015). Elder abuse. New England Journal of Medicine, 373, 1947–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs, M. S., Williams, C. S., O’Brien, S., & Pillemer, K. A. (2002). Adult protective service use and nursing home placement. Gerontologist, 42, 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachs, M. S., Williams, C. S., O’Brien, S., Pillemer, K. A., & Charlson, M. E. (1998). The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA, 280, 428–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, E. B., McKee, C. H., Cady, C. E., Cone, D. C., Colella, M. R., Cooper, A., et al. (2015). A consensus-based gold standard for the evaluation of mass casualty triage systems. Prehospital Emergency Care, 19(2), 267–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifespan of Greater Rochester, Weill Cornell Medical Center of Cornell University, and New York City Department for the Aging . (2012). Under the radar: New York State Elder Abuse Prevalence Study: Self-reported prevalence and documented case surveys. Retrieved fromhttps://ocfs.ny.gov/main/reports/Under%20the%20Radar%2005%2012%2011%20final%20report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, N., Huge, J., Sutherland, W. J., McNeill, J., Van Opstal, M., Dahdouh-Guebas, F., & Koedam, N. (2015). The Delphi technique in ecology and biological conservation: Applications and guidelines. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 1097–1109. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Elder Abuse . (2017). Elder abuse screening tools for healthcare professionals. Retrieved fromhttp://eldermistreatment.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Elder-Abuse-Screening-Tools-for-Healthcare-Professionals.pdf

- National Research Council (2003). Elder mistreatment: Abuse, neglect and exploitation in an aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale, A. V., Hwalek, M. A., Scott, R. O., Sengstock, M. C., & Stahl, C. (1991). Validation of the Hwalek-Sengstock elder abuse screening test. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 10, 406–418. [Google Scholar]

- New York City Elder Abuse Center . (n.d.). Definition of elder abuse. Retrieved fromhttps://nyceac.org/about/definition/

- Phelan, A. (2012). Elder abuse in the emergency department. International Emergency Nursing, 20, 214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer, K., Burnes, D., Riffin, C., & Lachs, M. S. (2016). Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Gerontologist, 56(Suppl. 2), S194–S205. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platts-Mills, T. F., Dayaa, J. A., Reeve, B. B., Krajick, K., Mosqueda, L., Haukoos, J. S., et al. (2018). Development of the emergency department senior abuse identification (ED Senior AID) tool. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 30, 247–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Policastro, C., & Payne, B. K. (2014). Assessing the level of elder abuse knowledge preprofessionals possess: Implications for the further development of university curriculum. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 26, 12–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C., & Mays, N.-J.-B. (1995). Qualitative research: Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ, 311(6996), 42–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, M. J., & Tomita, S. K. (1997). Elder abuse and neglect: Causes, diagnosis, and interventional strategies (Vol. 8). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rathbone-McCuan, E., & Voyles, B. (1982). Case detection of abused elderly parents. American Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 189–192. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.2.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis, M., & Nahmiash, D. (1995). Validation of the caregiver abuse screen (CASE). Canadian Journal on Aging–Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 14(Suppl. 2), 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, M., & Nahmiash, D. (1998). Validation of the indicators of abuse (IOA) screen. Gerontologist, 38, 471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis, M., Nahmiash, D., & Shrier, R. (1993). A Brief Abuse Screen for the Elderly (BASE): Its validity and use. Paper presented at the 22nd Annual Scientific and Educational Meeting of the Canadian Association on Gerontology, Montreal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, K. V., Rodgers, M., Sommers, M., Hanlon, A., Chittams, J., Doyle, A., et al. (2015). Brief motivational intervention for intimate partner violence and heavy drinking in the emergency department: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 314, 466–477. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, T., Hargarten, S., Flomenbaum, N. E., & Platts-Mills, T. F. (2016). Identifying elder abuse in the emergency department: Toward a multidisciplinary team-based approach. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 68, 378–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, T., Stern, M. E., Elman, A., & Mulcare, M. R. (2018). Identifying and initiating intervention for elder abuse and neglect in the emergency department. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 34, 435–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2018.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, T., Stern, M. E., Mulcare, M. R., Elman, A., McCarthy, T. J., LoFaso, V. M., et al. (2018). Emergency department provider perspectives on elder abuse and development of a novel ED-based multidisciplinary intervention team. Emergency Medicine Journal, 35, 600–607. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2017-207303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, M. J., Reynolds, R., Mishra, G. D., Powers, J. R., & Dobson, A. J. (2002). Screening for vulnerability to abuse among older women: Women’s health Australia study. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 21(1), 24–37. doi: 10.1177/0733464802021001002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, K. J., Clark, S., Kapoor, W. N., & Handler, S. M. (2012). Information primary care physicians want to receive about their hospitalized patients. Family Medicine, 44, 425–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . (2014). The elder justice roadmap. Retrieved fromhttps://www.justice.gov/file/852856/download

- Worrilow, W. M., & Barraco, R. D. (2015). Physician screening for elder abuse in the emergency department: A literature review. Lehigh Valley Health Network Research Scholar Program Poster Session, Allentown, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe, M. J., Wolfson, C., Lithwick, M., & Weiss, D. (2008). Development and validation of a tool to improve physician identification of elder abuse: The elder abuse suspicion index (EASI)©. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 20, 276–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]