Abstract

Background and Aim

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)‐guided through‐the‐needle biopsy (TTNB) has improved the diagnostic algorithm of pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs). Recently, a new through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps device (Micro Bite, MTW Endoskopie Manufakture) has been introduced. The primary aim was to assess the safety and technical success of this new type of micro‐forceps. The secondary aim was to evaluate the diagnostic role of EUS‐TTNB.

Methods

Retrospective study of consecutive patients receiving EUS‐TTNB for the diagnosis of PCNs. Two micro‐forceps were used: Moray Micro‐forceps and Micro‐Bite. Cystic fluid was collected for cytological analysis. Categorical variables were analyzed by Fisher's exact test, and continuous variables were analyzed by Student's t‐test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Forty‐nine patients enrolled in the study (24% male; mean age 63 ± 14 years). TTNB was successfully performed in all patients. A diagnostic sample was obtained in 67.3% PCNs with TTNB compared with 36.7% with cyst fluid cytology (P 0.01). Adverse events rate was 10.2% and occurred in older patients (76.6 ± 5.4 vs 61.3 ± 13.7 P = 0.02). The 51% underwent EUS‐TTNB with Micro Bite. A diagnostic sample was obtained in 52% PCNs with Micro Bite compared with 24% obtained with cyst fluid cytology (P = 0.07). Comparing the two devices, the rate of diagnostic sample obtained with the micro‐forceps Moray was higher than that obtained with the Micro Bite (20/24 [83.3%] vs 13/25 [52%] P 0.03).

Conclusions

EUS‐TTNB increases the diagnostic yield of PCNs. The new Micro‐Bite could represent a valid alternative to the currently used Moray Micro‐forceps, but its diagnostic rate is still suboptimal and further studies are needed.

Keywords: endoscopic ultrasound, increased diagnosis, micro‐forceps, new device, pancreatic cystic neoplasm

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)‐fine needle aspiration (FNA)‐based cytology has low sensitivity and specificity to differentiate pancreatic cystic neoplasm (PCN). EUS through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps (EUS through‐the‐needle biopsy [TTNB]) increases the diagnostic yield. A new EUS‐TTNB microforceps device (Micro Bite, MTW Endoskopie Manufakture) has been introduced, which was successfully performed in all 49 patients. Fifty‐one percent of the patients underwent EUS‐TTNB with MTW, and technical success was 100%. A diagnostic sample was obtained in 52% of PCNs with Micro Bite compared with 24% obtained with cyst fluid cytology (P = 0.07). Overall EUS‐TTNB diagnostic rate was greater than FNA (67.3% vs 36.7% P < 0.01). This is the first study evaluating the efficacy of the MTW in the diagnosis of PCN. MTW represents a valid and safe alternative to the Moray micro‐forceps. High diagnostic yield of EUS‐TTNB was obtained in pancreatic cystic neoplasm.

Introduction

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) are being diagnosed with increasing frequency because of the widespread use of cross‐sectional imaging and are estimated to be present in 2–45% of the general population. PCN comprises a clinically challenging entity as their biological behavior ranges from benign to malignant disease.1

On one hand, some PCNs have the potential for malignant transformation to adenocarcinoma, but on the other hand, this rate is low and it is estimated approximately 0.24% per year.2 Consequently, correct management of PCN may prevent progression to pancreatic cancer as well as minimizing the need for lifelong follow‐up surveillance.

At present, there is no single diagnostic test that reliably can help in distinguishing and stratifying the malignancy risk of PCNs. Hence, the current clinical practice relies on a combination of clinical history, cross‐sectional imaging, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA), cyst fluid analysis, and cytology.1, 2, 3, 4, 5

A recent study showed that EUS‐FNA‐based cytology had 42% sensitivity and 99% specificity to differentiate mucinous from non‐mucinous PCN.6

Targeted cyst wall sampling using FNA can provide adequate specimen for cytologic or histologic evaluation in 65–81% but the diagnostic yield remains low (29%) due to the relatively small tissue sample that can be obtained using conventional FNA.7, 8

To improve the diagnostic yield, a through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps device (Moray Microforceps, US Endoscopy, Mentor, OH, USA) was introduced for EUS‐guided tissue sampling in PCNs. This single‐use micro‐forceps can be passed through the lumen of a standard 19‐gauge EUS‐FNA needle, allowing through‐the‐needle tissue biopsy (TTNB) for histologic sampling of PCNs.

Several case‐reports and observational studies9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19 have been published. However, these studies were affected by a high heterogeneity and by the small number of included patients that have limited the possibility to assess the real clinical impact.

Recently, a new through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps device (Micro Bite, MTW Endoskopie Manufakture) has been introduced. The shape of the forceps is oval, spoon‐shaped mouth, toothed, with diameter of 0.8 mm (Fig. 1). This single‐use micro‐forceps can be passed through the lumen of a standard 19‐gauge EUS‐FNA needle.

Figure 1.

Micro Bite: MTW Endoskopie Manufakture.

There are no data in the literature about the diagnostic role of this new through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps in the management of PCNs. The primary aim of this study was to assess the safety and technical success of this new through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps. The secondary aims were to evaluate the overall diagnostic role of EUS‐TTNB in the management of PCN when compared with FNA cyst fluid cytology.

Methods

It is a retrospective study of consecutive patients who underwent EUS‐FNA and TTNB for PCNs at the Operative Endoscopy department of Campus Bio‐Medico University Hospital of Rome. In accordance with the international guidelines,1 the pancreatic cysts enrolled in the study were those with features suspected for malignancy: Growth‐rate ≥5 mm/year; increased levels of serum carbohydrate antigen 19.9 (CA 19.9) (>37 U/mL); main pancreatic duct dilatation between 5 and 9.9 mm; cyst diameter ≥40 mm; enhancing mural nodule (<5 mm).

The EUS exam was performed using a linear Ecoendoscope Fujifilm (EG‐580UT), with patients in deep sedation. The cyst's size and location, the presence of mural nodule, solid mass or wall thickness and the main pancreatic duct dilation were recorded. EUS‐FNA was performed using the 19‐gauge EUS‐FNA needle (Boston scientific Slimline).

Before puncturing PCNs, the stylet was removed and the micro‐forcep was preloaded in the FNA needle in order to reduce fluid aspiration and cystic walls collapse due to the stylet removal before the sampling. The needle was inserted into the PCN under EUS guidance and with the use of Doppler to avoid interposed vessels. After puncturing PCNs, the micro‐forcep was inserted through the FNA needle till it was seen inside the cyst (Fig. 2). The micro‐forcep open was then advanced and gently pushed against the opposite walls, then closed and pulled back until the “tent sign” was seen. In case of the presence of mural nodules, the biopsy was directed on them.

Figure 2.

EUS‐TTNB of pancreatic cyst. The hyperechogenic needle is inside the cyst. The arrow indicates the small jaws of the opened micro‐forceps. EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; TTNB, through‐the‐needle biopsy.

The specimen obtained was placed directly in formalin. The number of passes was guided by the obtainment of macroscopic visible fragment of tissue. Cystic fluid was also collected for intra‐cystic markers dosage (carcinoid embryonic antigen [CEA], amylase, lipase) and for cytological analysis. For the cytological analysis, cystic fluid was either smeared onto a glass slide or placed into a CytoLyt container for liquid‐based cytology. Cytological and histological samples were evaluated by a pathologist specialized in pancreatic cytology and were graded according to the guidelines of the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology.20 A prophylactic antibiotic (Fluoroquinolones) was administrated. Technical success was defined as the successful acquisition of at least one macroscopically visible biopsy sample.

An adequate sample was defined when there was sufficient material for the histological analysis. A diagnostic sample was defined if the material obtained allows distinguishing the type of pancreatic cysts. A cyst was determined to be mucinous on cytology if there was identifiable epithelium with characteristics consistent with mucinous pancreatic cystic epithelium. On histology with TTNB, a cyst was categorized as mucinous if there was mucinous epithelium with cytoplasmic mucin seen.

The final diagnosis was obtained by surgical histopathology when available. In the absence of surgery, the diagnosis was based on a combination of imaging features, value of CEA, history of acute/chronic pancreatitis, and stable appearance on follow‐up imaging at 12 months or later.

Safety was defined by the rate of occurrence of post‐procedure adverse events. Adverse events were defined according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)'s lexicon on adverse events in endoscopy.21

Two different TTNB micro‐forceps were used: The Moray Microforcep, US Endoscopy, Mentor, OH and the Micro Bite; MTW Endoskopie Manufakture. The choice was made according to the hospital's availability of the device.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were presented as mean with corresponding SD or median with range. Categorical variables were presented as percentages. In the univariate analysis, numerical outcomes were compared using a Student's t test, while for categorical data Fischer's exact test was used. A logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the association between the abovementioned variables and the TTNB diagnostic samples. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, from December 2017 to November 2020, 49 patients who underwent EUS‐TTNB were included (24.5% male; mean age 63 ± 14 years old). In 13 (26.5%) PCNs, mural nodules were observed. Pathological dilatation of pancreatic duct (5–9 mm) was detected in eight (2%) patients (Table 1). In 18 PCNs (36.7%), the size was bigger than 40 mm. Six patients showed an increase of cyst's size of more than 5 mm from the previous follow‐up image and four patients had increased serum CA 19.9 value.

Table 1.

General features of pancreatic cystic neoplasm

| Pancreatic cyst's features | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Cyst size (mean; SD) | 38.2 ± 16 |

| Location | |

| Head | 21 (43) |

| Body | 13 (27) |

| Tail | 15 (30) |

| Multifocal | 14 (28.5) |

| Main PD dilated | 8 (16.3) |

| Mural nodule | 13 (26.5) |

| Atrophic parenchyma | 4 (8.2) |

| Feasibility of TTNB | 49 (100) |

| Adequate samples | 40/49 (81.6) |

| Diagnostic samples | 33/49 (67.4) |

| Number of passes (median; range) | 3.5 (1–6) |

| Adverse events | 5 (10.2) |

PD, pancreatic duct; TTNB, through‐the‐needle biopsy.

The mean size of PCNs was 38 ± 16 mm and was mostly localized in pancreatic head and tail (42.8%). Exactly 28.6% of patients had multifocal disease. A unilocular cyst was observed in 65% of the patients. In 25 patients (51%), EUS‐TTNB has been performed with the new device Micro Bite, MTW Endoskopie Manufakture. EUS‐TTNB with Micro Bite was successfully performed in 25 of 25 (100%) patients. An adequate sample was obtained in 17 of 25 (68%) patients. A diagnostic sample was obtained in 13 of 25 (52%) PCNs with TTNB compared with 6 of 25 (24%) obtained with FNA cyst fluid cytology (P 0.07). Only one patient had an adverse event represented by the occurrence of fever after the procedure.

Considering all patients independently from the type of device, a diagnostic sample was obtained in 33 of 49 (67.3%) PCNs with TTNB compared with 18 of 49 (36.7%) obtained with FNA cyst fluid cytology (P 0.01).

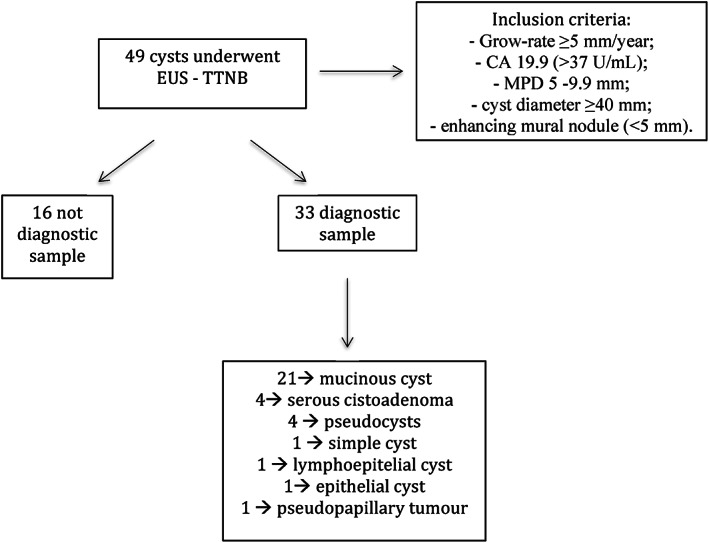

Mucinous PCNs were diagnosed in 21 of 49 patients (42.8%). Sixteen of 49 samples were classified as not diagnostic; 4 of 49 were serous cistoadenoma; 1 of 49 were lymphoepithelial cyst; 1 of 49 solid pseudopapillary tumor; 4 of 49 pseudocysts; 1 of 49 simple cyst; 1 of 49 epithelial cyst with low‐grade dysplasia (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the management of pancreatic cysts: From the inclusion criteria to the diagnosis.

We evaluated the possible association between cystic features and the diagnosis with TTNB. There was no difference in terms of cyst size (38.1 ± 17 vs 38.4 ± 15 P 0.41), cyst location in pancreatic head versus other sites (12/21 57.1% vs 9/21 42.8% P 0.25), presence of mural nodule (9/13 69.2% vs 4/13 30.7% P 1), and the rate of diagnosis with TTNB. In the logistic regression analysis, neither the presence of mural nodule nor the presence of pathologic Wirsung dilation was associated with a higher rate of TTNB diagnostic sample (odds ratio [OR] 0.89 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.22–3.48 P 0.86; OR 1.5 95% CI 0.27–8.73 P 0.62). The localization of the cyst in the pancreatic head was not associated with a higher rate of TTNB diagnostic sample (OR 0.45 95% CI 0.13–1.49 P 0.91). The mean value of CEA in mucinous cyst was 1792.3 ± 3533.7 ng/mL.

Regarding the safety of the EUS‐TTNB, post‐procedure adverse events were observed in 5 of 49 (10.2%) cases. Two (40%) of these were mild acute pancreatitis managed with fasting and fluid resuscitation. One (20%) patient experienced moderate–severe acute pancreatitis with infected fluid collections that were drained with EUS stent position. Two (40%) patients had fever after the procedure, which was managed with antibiotic therapy and paracetamol.

There was no association between the cystic size and the risk of adverse events (48.2 ± 19 vs 37.8 ± 15 P 0.15). The mean age was higher in patients who developed adverse events compared with those who did not (76.6 ± 5.4 vs 61.3 ± 13.7 P 0.02). About the mean number of passes performed with the micro‐forceps, data were available only for 23 patients. The median value was 3 (range of 1–6 passes). The mean number of passes in patients in whom the EUS‐TTNB was diagnostic was similarly compared with the others (3.2 ± 1 vs 3.7 ± 1 P 0.28).

Overall, four patients underwent surgery, and in three cases, the diagnosis was confirmed. Only in one patient, while the histological diagnosis obtained with TTNB was intraductal mucinous papillary neoplasm (IPMN) with low‐grade dysplasia, the definitive histological diagnosis in the surgical specimen was mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Comparing the two devices, the rate of diagnostic sample obtained with the micro‐forceps Moray was higher than that obtained with the Micro Bite (20/24 [83.3%] vs 13/25 [52%] P 0.03) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Differences between micro‐forceps Moray and Micro Bite

| Moray (n 24) | Micro Bite (n 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyst's size (mean; SD) | 38.6 ± 17 | 37.8 ± 16 | 0.86 |

| Feasibility of through‐the‐needle biopsy | 24/24 (100%) | 25/25 (100%) | 1 |

| Adequate sample | 23/24 (95.8%) | 17/25 (68%) | 0.02 |

| Diagnostic sample | 20/24 (83.3%) | 13/25 (52%) | 0.03 |

| Adverse events | 4/24 (16.7%) | 1/25 (4%) | 0.18 |

There was no difference in terms of mean age (62 ± 14 vs 63.1 ± 14 P 0.91), male sex (6/24 vs 6/25 P 1), and cyst's size (37.8 ± 15 vs 38.6 ± 17 P 0.86) between the two groups of patients.

No difference in terms of adverse events rate was observed between the two micro‐forceps (4/5 [80%] vs 1/5 [20%] P 0.18).

Discussion

The present retrospective study investigates, for the first time, the safety and technical success of a new micro‐forceps, the Micro Bite, MTW Endoskopie Manufakture, for the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Of the 49 patients with PCNs included in the study, this new device was used in 25 patients, and it was successfully performed in all cases, obtaining an adequate sample for the histological analysis in 68% of the patients. Mild adverse event occurred in one patient.

Considering the overall EUS‐TTNB, independently from the type of micro‐forceps, a histological adequate sample and a histological diagnostic sample were obtained irrespectively in 67.3% and 81.6% of PCN. The high technical success and tissue acquisition yield with TTNB in the current study are in line with prior series and so it supports the reproducibility of these findings.

A recent meta‐analysis conducted on nine studies aimed to assess the clinical impact of EUS‐TTNB in terms of technical success, histological accuracy, and diagnostic yield.22

The overall histologic adequacy of EUS‐TTNB was around 87% and the diagnostic yield was 69.5% (95% CI 59.2–79.7) with high heterogeneity among studies (I 2 = 84.7%; P < 0.001). This suboptimal diagnostic yield was possibly related to the heterogeneity of cyst wall. In fact, a large portion of the cyst may undergo epithelial denudation, and TTNB samples can result in inconclusive fibrotic tissue. The fact that TTNB does not provide information on the whole cyst but only on focal pieces is probably the greatest limitation of this technique. This aspect was experienced even in our study where in one patient the histological diagnosis obtained with TTNB showed low‐grade dysplasia while the definitive histological diagnosis in the surgical specimen presented foci of adenocarcinoma.

In another meta‐analysis conducted on 11 studies, Facciorusso and colleagues showed that the overall sample adequacy rate with TTNB was 85.3%, with diagnostic accuracy and sensitivity of 78.8% and 82.2%, respectively.23

About the number of passes that should be performed, the method is still not standardized. In the literature, the average number of micro‐forceps passes is three and it seems to be associated with the histological adequacy and diagnostic yield. On the other hand, it is necessary to define the minimum number of passes necessary to reach an adequate diagnosis because the traumatism of each pass could increase the risk of adverse events and the time of the procedure.

In their study, Crinò et al showed that the obtainment of two TTNB macroscopically visible specimens reached 100% histologic adequacy and a specific diagnosis in 74% of patients. The collection of a third specimen did not add any additional information and should be avoided to possibly decrease the risk of adverse events.24

In the present study, the number of passes was available only for 23 patients, and the mean number was similar between diagnostic and non‐diagnostic sample obtained. Of course these results must be taken with caution because of the small number of the patients but it could be correlated with the fact that the most important aspect is the attainment of macroscopically visible specimens independently from the number of passes.

Regarding the risk of post‐procedure adverse events, data from the literature show that the pooled estimate for the overall adverse events rate of EUS‐TTNB was 8.6% (95% CI 4.0–13.1). In the present study, adverse events were observed in 10.2% of cases, and it is concordant with previous results. However, we experienced major adverse events (necrotizing acute pancreatitis) only in one case.

The present study has some limitations related to its retrospective design. Indeed, only a small percentage of PCN underwent surgery and so only for those we have a definite diagnosis. However, the other lesions were followed up according with the European guidelines,1 and in no case the diagnosis was changed. Ultimately, the aspiration of cystic fluid was performed after the TTNB sampling and it could cause cyst's wall bleeding, which may interfere with the cytological evaluation.

In conclusion, for the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the safety and technical success of the Micro Bite forceps in the diagnosis of PCN. This new device—Micro Bite: MTW Endoskopie Manufakture—represents a valid alternative to the currently used Moray Microforceps, given the high adequate sample rate. However, other studies conducted on wider sample of patients are necessary to confirm it.

The present study confirms the high diagnostic yield of EUS‐TTNB in PCN. This technique seems to be safe but not absolutely free from adverse events, so it should be performed in well‐selected patients.

Declaration of conflict of interest: All the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contribution: Serena Stigliano and Francesco Covotta collected and analyzed the data. Serena Stigliano and Francesco M Di Matteo wrote the manuscript. All the authors carefully reviewed the manuscript.

References

- 1.The European Study Group on Cystic Tumours of the Pancreas . European evidence‐based guidelines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Gut. 2018; 67: 789–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheiman JM, Hwang JH, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015; 148: 824–48.e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park WG, Mascarenhas R, Palaez‐Luna Met al. Diagnostic performance of cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and amylase in histologically confirmed pancreatic cysts. Pancreas. 2011; 40: 42–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cizginer S, Turner BG, Bilge AR, Karaca C, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Cyst fluid carcinoembryonic antigen is an accurate diagnostic marker of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Pancreas. 2011; 40: 1024–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaddam S, Ge PS, Keach JWet al. Suboptimal accuracy of carcinoembryonic antigen in differentiation of mucinous and nonmucinous pancreatic cysts: results of a large multicenter study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015; 82: 1060–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gillis A, Cipollone I, Cousins G, Conlon K. Does EUS‐FNA molecular analysis carry additional value when compared to cytology in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasm? A systematic review. HPB. 2015; 17: 377–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barresi L, Tarantino I, Traina Met al. Endoscopic ultrasound‐guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy using a 22‐gauge needle with side fenestration in pancreatic cystic lesions. Dig. Liver Dis. 2014; 46: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong SK, Loren DE, Rogart JNet al. Targeted cyst wall puncture and aspiration during EUS‐FNA increases the diagnostic yield of premalignant and malignant pancreatic cysts. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2012; 75: 775–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hashimoto R, Lee JG, Chang KJ, Chehade NEH, Samarasena JB. Endoscopic ultrasound‐through‐the‐needle biopsy in pancreatic cystic lesions: a large single center experience. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2019; 11: 531–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang D, Trindade AJ, Yachimski Pet al. Histologic analysis of endoscopic ultrasound‐guided through the needle microforceps biopsies accurately identifies mucinous pancreas cysts. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019; 17: 1587–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang D, Samarasena JB, Jamil LHet al. Endoscopic ultrasound‐guided through‐the‐needle microforceps biopsy in the evaluation of pancreatic cystic lesions: a multicenter study. Endosc Int Open. 2018. Dec; 6: E1423–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samarasena JB, Nakai Y, Shinoura S, Lee JG, Chang KJ. EUS‐guided, through‐the‐needle forceps biopsy: a novel tissue acquisition technique. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015; 81: 225–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barresi L, Tarantino I, Ligresti D, Curcio G, Granata A, Traina M. A new tissue acquisition technique in pancreatic cystic neoplasm: endoscopic ultrasound‐guided through‐the ‐needle forceps biopsy. Endoscopy. 2015;47(S 01): E297–2015, 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pham KD‐C, Engjom T, Gjelberg Kollesete H, Helgeland L. Diagnosis of a mucinous pancreatic cyst and resection of an intracystic nodule using a novel through‐the‐needle micro forceps. Endoscopy. 2016; 48(S 01): E125–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shakhatreh M, Naini S, Brijbassie A, Grider D, Shen P, Yeaton P. Use of a novel through‐ the‐needle biopsy forceps in endoscopic ultrasound. Endosc Int Open. 2016; 04: E439–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Attili F, Pagliari D, Rimbaș Met al. Endoscopic ultrasound‐guided histological diagnosis of a mucinous non‐neoplastic pancreatic cyst using a specially designed through‐the‐needle microforceps. Endoscopy. 2016; 48(S 01): E188–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huelsen A, Cooper C, Saad N, Gupta S. Endoscopic ultrasound‐guided, through‐the‐needle forceps biopsy in the assessment of an incidental large pancreatic cystic lesion with prior inconclusive fine‐needle aspiration. Endoscopy. 2017; 49(S 01): E109–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crinò SF, Bernardoni L, Gabbrielli Aet al. Beyond pancreatic cyst epithelium: evidence of ovarian‐like stroma in EUS‐guided through‐the‐needle micro‐forceps biopsy specimens. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018; 113: 1059–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barresi L, Tacelli M, Chiarello G, Tarantino I, Traina M. Mucinous cystic neoplasia with denuded epithelium: EUS through‐the‐needle biopsy diagnosis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2018; 88: 771–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pitman MB, Centeno BA, Ali SZet al. Standardized terminology and nomenclature for pancreatobiliary cytology: the Papanicolaou Society of Cytopathology guidelines. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2014; 42: 338–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cotton PB, Eisen GM, Aabakken Let al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010; 71: 446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tacelli M, Celsa C, Magro Bet al. Diagnostic performance of endoscopic ultrasound through‐the‐needle microforceps biopsy (EUS‐TTNB) of pancreatic cystic lesions: a systematic review with meta‐analysis. Dig. Endosc. 2020; 32:1018–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Facciorusso A, Del Prete V, Antonino M, Buccino VR, Wani S. Diagnostic yield of EUS‐guided through‐the‐needle biopsy in pancreatic cysts: a meta‐analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020; 92:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crinò SF, Bernardoni L, Brozzi Let al. Association between macroscopically visible tissue samples and diagnostic accuracy of EUS‐guided through‐the‐needle microforceps biopsy sampling of pancreatic cystic lesions. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2019; 90: 933–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]