Short abstract

Tumors impair function of tumor‐infiltrated antigen‐presenting cells by altering intracellular PGE2 catabolism in the myeloid cells.

Keywords: COX‐2, 15‐PGDH, microenvironment, lipid mediators, cancer

Abstract

Recent studies suggest that tumor‐infiltrated myeloid cells frequently up‐regulate COX‐2 expression and have enhanced PGE2 metabolism. This may affect the maturation and immune function of tumor‐infiltrated antigen‐presenting cells. In vitro studies demonstrate that tumor‐derived factors can skew GM‐CSF‐driven differentiation of Th1‐oriented myeloid APCs into M2‐oriented Ly6C+F4/80+ MDSCs or Ly6C–F4/80+ arginase‐expressing macrophages. These changes enable myeloid cells to produce substantial amounts of IL‐10, VEGF, and MIP‐2. The tumor‐mediated inhibition of APC differentiation was associated with the up‐regulated expression of PGE2‐forming enzymes COX‐2, mPGES1 in myeloid cells, and the simultaneous repression of PGE2‐catabolizing enzyme 15‐PGDH. The presence of tumor‐derived factors also led to a reduced expression of PGT but promoted the up‐regulation of MRP4, which works as a PGE2 efflux receptor. Addition of COX‐2 inhibitor to the BM cell cultures could prevent the tumor‐induced skewing of myeloid cell differentiation, partially restoring cell phenotype and down‐regulating the arginase expression in the myeloid APCs. Our study suggests that tumors impair the intracellular PGE2 catabolism in myeloid cells through simultaneous stimulation of PGE2‐forming enzymes and inhibition of PGE2‐degrading systems. This tumor‐induced dichotomy drives the development of M2‐oriented, arginase‐expressing macrophages or the MDSC, which can be seen frequently among tumor‐infiltrated myeloid cells.

Abbreviations

- 15‐PGDH

15‐hydroxy‐PG dehydrogenase

- BM

bone marrow

- COX‐2

cyclooxygenase 2

- DC

dendritic cell

- MDSC

myeloid‐derived suppressor cell

- mPGES1

microsomal PGE synthase‐1

- MRP4

multidrug resistance protein 4

- PGT

PG influx transporter

- TAM

tumor‐associated macrophage

- TCM

tumor‐conditioned medium

- Treg

T regulatory cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Antigen‐presenting cells are crucial for initiation of an adaptive immune response. APCs present antigens to cognate TCRs and stimulate the differentiation of T cells into type 1 or type 2 subsets, depending on the cellular and cytokine milieu, which results in T cell activation or tolerance. The function of APC is tightly regulated by the local microenvironment, which shapes the generation of immune response. The tumor microenvironment contains an abundance of immunosuppressive factors. Tumor‐derived factors affect maturation and function of tumor‐infiltrated APCs, thus promoting unfavorable local conditions for development of effective anti‐tumor immune response.

PGE2 is a tumor‐derived factor that is overexpressed frequently in the tumor microenvironment; furthermore, itˈs involved in tumor‐mediated immune dysfunction. PGE2 hinders the ability of BM‐derived APCs to present antigen and secrete Th1 cytokines, but on the other hand, PGE2 stimulates production of Th2 and Th17 cytokines [1, –, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Recent studies suggest that PGE2 may contribute to tumor‐induced immunosuppression by modulating function of Tregs and MDSCs. Consequently, PGE2 up‐regulates forkhead box P3 expression in Tregs and enhances the in vitro inhibitory function of these cells [7]. PGE2 is also able to up‐regulate expression of arginase I in myeloid cells [8]. Arginase is involved in mechanisms of MDSC‐mediated immune suppression, and its expression is highly up‐regulated in TAMs [9] and tumor‐infiltrated myeloid cells [10]. In addition, high concentrations of PGE2 inhibit in vitro differentiation of BM‐derived DCs and promote accumulation of MDSCs [11, 12].

Increased COX‐2 expression and enhanced PGE2 production are attributed frequently to the inflammation‐associated cancers such as lung, colon, bladder, prostate, and other cancers [13, 14]. Moreover, the expression of inducible enzyme COX‐2 has been detected in cancer and inflammatory tumor‐infiltrated cells, including myeloid APCs and their precursors [14, –, 16].

To evaluate the effect of tumor‐derived factors on intracellular PGE2 metabolism in myeloid APCs, we used an in vitro model of GM‐CSF‐driven generation of BM‐derived DCs. Our results indicate that addition of CT‐26 TCM to the BM cell culture promotes strong up‐regulation of COX‐2 and mPGES1 and reduces expression of the PGE2‐catabolizing enzyme in myeloid cells. The presence of TCM alters the antigen‐presenting function of BM‐derived APCs, and it promoted the development of macrophage‐like immunosuppressive myeloid cells. Pharmacological inhibition of COX‐2 activity in myeloid cells significantly improves the differentiation and function of BM‐derived APCs, which were impaired by tumor‐derived factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and tumor models

Six‐ to 8‐week‐old BALB/c and C57BL/9 female mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD, USA). The CT‐26 murine colon carcinoma cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA).

Generation of BM‐derived APCs

The method for generating of BM‐derived CD11c+F4/80+ cells with GM‐CSF was adapted from previous publications [17, 18] with some modifications. At Day 0, BM cells were seeded into tissue treated with 150 cm2 cell culture flask (Corning Inc., Lowell, MA, USA) in 20 ml DMEM/F12 culture medium containing 10 ng/ml rGM‐CSF to remove adherent cells. After 4 h of incubation, floating, nonadherent cells were collected, counted, and plated down at 0.5–1 × 106 cells/well of a six‐well ultra‐low attachment plate (Corning Inc.) in 5 ml complete culture medium containing 20 ng/ml rGM‐CSF. Fresh GM‐CSF was added to the wells with cells on Days 2, 4, and 6. On Day 8, cells that were slightly attached to the bottom were lifted using a cell lifter (Costar, Corning, NY, USA). In some experiments, the COX‐2 inhibitor LM‐1685 (Calbiochem, San‐Diego, CA, USA) and/or selective mPGES1 inhibitor CAY10589 (Cayman Chemical, Ann‐Arbor, MI, USA) at various concentrations were each added in cell cultures starting from Day 0.

CT‐26 TCM

CT‐26 tumor cells (5×105 cells/mouse) were injected s.c. into BALB/c mice. Two weeks after inoculation of tumor cells, mice were killed in CO2 chamber. Tumor cell suspension was prepared by enzymatic digestion as described before [15]. After washing in PBS, tumor single‐cell suspension was resuspended in the DMEM/F12 (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) medium supplemented with 5% FBS and antibiotics (penicillin/streptomycin, HyClone) and placed in 150 mm2 flasks at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells/ml. Twenty‐four hours later, supernatant (TCM) was collected, filtered, aliquoted, and frozen. In all experiments where the presence of tumor‐derived factors was required, 25% of CT‐26 TCM was added in cell cultures.

Cell isolation

T lymphocytes were purified from freshly isolated, naive splenocytes using mouse T cell enrichment columns (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), according to the manufacturerˈs instructions. Ly‐6C‐positive cells were isolated from mouse BM cell suspension by using positive selection and PE‐conjugated anti‐Ly‐6C antibody (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA) and MACS MicroBeads against PE, according to the manufacturerˈs instructions. Briefly, BM cells were incubated with PE‐conjugated anti‐Ly‐6C antibodies for 20 min and washed twice with PBS. After washing with cold MACS, buffer‐stained cells were incubated with PE‐microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) for an additional 15 min and subsequently subjected to positive selection of Ly‐6C+ cells on a MACS LS column, according to the manufacturerˈs instructions (Miltenyi Biotec). The purity of recovered cells, as assessed by flow cytometry, exceeded 95%.

Allogeneic MLR

T lymphocytes were purified from freshly isolated, naive splenocytes of C57B/6 mice using mouse T cell enrichment columns. Triplicates of 1 × 105‐enriched T cells were seeded into a 96‐well round‐bottom plate (Costar) together with titrated numbers of BALB/c BM‐derived APCs generated in the presence or absence CT‐26 TCM. At Day 3, BrdU was added into cell cultures for 18 h. Proliferation of CD3, CD4, and CD8 T cells was assessed by BrdU incorporation into S‐phase DNA by flow cytometry using an APC BrdU flow kit (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Flow cytometry

Cells were stained with antibodies against I‐Ad, Ly‐6C, Ly‐6G, CD86, CD80 CD11b, CD11c, and F4/80 as described before [15]. Cytometry data were acquired using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and analyzed with CXP software (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Analysis of Stat1 and Stat3 phosphorylation

Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of phospho‐Stat1 (pY701) and phospho‐Stat3 (pY705) was performed using BD Phosflow technology (BD Biosciences). BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) or CT‐26 conditioned medium (25% of total volume) in an ultra‐low attachment plate for 6 days. In some experiments, the COX‐2 inhibitor was added at a concentration of 40 μM. On Day 6, cells were collected, washed in PBS, and fixed immediately in BD Phosflow lyse/fix buffer (BD Biosciences) for 10 min at 37°C. Then, cells were washed in PBS and permeabilized in BD Phosflow Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences) for 30 min on ice. Cells were stained with PE‐conjugated mouse antiphospho‐Stat1 (pY701) and antiphospho‐Stat3 (pY705) antibodies (BD Biosciences) with a combination of surface APC‐conjugated anti‐F4/80 antibodies (Serotec, UK) at recommended concentrations for 30 min.

Multiplex cytokine assay

BM cells were cultured in the presence or absence of CT‐26 TCM as described above. Twenty‐four hours later, cell culture supernatants were collected, filtered, and stored at –80°C and then assayed for the presence of cytokines using a Multiplex assay. A Multiplex cytokine kit was obtained from Bio‐Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA, USA), and an assay was performed using Luminex‐200 (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA).

Quantitative real‐time PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated from BM cells using the RNeasy Plus mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), according to the manufacturerˈs instructions. Integrity of the RNA was analyzed in a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). cDNA for each RNA sample was synthesized in 20 μL reactions using the high‐capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) following the manufacturerˈs protocol. Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis was performed using an Applied Biosystems Prism 7900HT fast real‐time PCR system, according to the manufacturerˈs specification. cDNA‐specific TaqMan® gene expression assays for 15‐(NAD)PGDH (Assay ID: Mm00515121_m1), COX‐2 (Assay ID: Mm00478374_m1), and mPGES1 (Assay ID: Mm00478374_m1) from Applied Biosystems were used in the study. A mouse actin β was used as an endogenous control (Applied Biosystems).

Assay for arginase activity

Arginase activity was measured in BM cell lysates using the QuantiChrom arginase assay kit from BioAssay Systems (Hayward, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance between values was determined by the Student t‐test. The data were expressed as the mean ± sd. Probability values ≥0.05 were considered nonsignificant. Significant values of P ≤ 0.05 were expressed with an asterisk. The flow cytometry data shown are representative of at least three separate determinations.

RESULTS

In vitro generation of BM‐derived antigen‐presenting cells

According to recent studies [17, 18], there are three major stable cell populations that could be generated from BM progenitors when stimulated with GM‐CSF: firmly adherent macrophages and loosely adherent, immature and nonadherent, mature BM‐derived DCs. In the present study, we used the ultra‐low attachment cell culture plates to avoid the adherence of cultured cells to the plastic and promote the generation of DCs through formation of cell clusters [19].

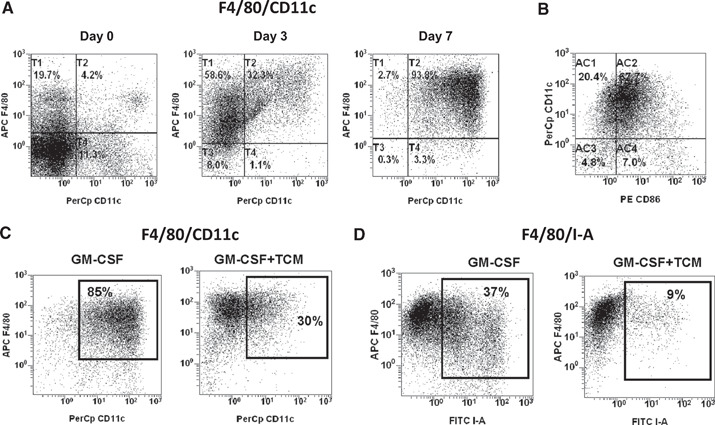

We cultured the BM‐derived progenitors from naïve mice in the presence of GM‐CSF for 8 days. As shown in Figure 1 A, 80% of BM‐derived cells collected on Day 3 expressed monocyte‐macrophage marker F4/80, and only 30% of them acquired murine DC marker CD11c. On Day 8, most of cultured cells were F4/80/CD11c double‐positive cells. Interestingly enough, all CD11c‐positive cells coexpressed the F4/80 marker at any time‐point of culturing BM cells in the presence of GM‐CSF (Fig. 1A). Most CD11c‐positive cells also coexpressed the CD86 costimulatory molecule (Fig. 1B), but the expression of CD80 was low (data not shown). In addition to the F4/80/CD11c double‐positive cells, on Day 8, we detected in cultures small amounts of Ly‐6G+ neutrophils (<5%) and B220‐positive cells (<5%; data not shown). Total yield of BM‐derived APCs in ultra‐low attachment plates was significantly higher than in conventional cell culture plates, where myeloid cells are free to attach to the plastic surface (data not shown).

Figure 1.

CT‐26 TCM inhibits GM‐CSF‐driven differentiation of BM‐derived myeloid antigen‐presenting cells. (A and B) In vitro generation of BM‐derived myeloid antigen‐presenting cells. BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) for 8 days in ultra‐low attachment plates. At indicated time‐points, cells were collected, stained for CD11c, F4/80 (A), and CD86 (B), and analyzed by flow cytometry. (C and D) BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) and/or CT‐26 conditioned media (25% of total volume). On Day 8, cells were collected, and expression of CD11c, F4/80, and I‐A was assessed by flow cytometry. Results of one representative experiment out of four are shown. APC F4/80, allophycocyanin‐F4/80.

CT‐26 TCM impairs differentiation of BM‐derived CD11c+MHC class II‐positive APCs but promotes expansion of Ly6C+F4/80+ monocyte‐type MDSC and F4/80+CD11c– macrophages

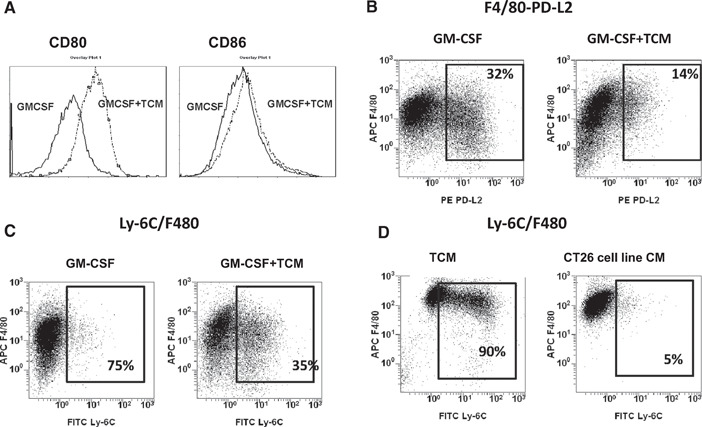

It is well documented that the local microenvironment and cytokine milieu in the tumor vicinity tend to disrupt the immunological functions of newly recruited mononuclear phagocytes. Some of these disruptions include maturation of tumor‐infiltrated APCs, its antigen‐presenting function, and macrophage‐mediated cytotoxicity toward tumors. As a consequence, recruited myeloid cells frequently diverted toward pro‐tumoral‐immunosuppressive TAMs or MDSCs [20, –, 22, 23, 24, 25]. Indeed, culturing of BM cells in the presence of the CT‐26 TCM substantially impaired the in vitro GM‐CSF‐driven development of myeloid APCs. Figure 1C shows that in the absence of TCM, 85% of cells cultured in medium contained GM‐CSF alone and expressed DC marker CD11c and macrophage marker F4/80. In contrast, the addition of TCM to the cell culture with GM‐CSF profoundly decreased the expression of CD11c down to 30% but not the F4/80 marker. Furthermore, TCM markedly reduced expression of the MHC class II molecule (Fig. 1D). We also observed that TCM promotes an up‐regulation of CD80 but had no effect on expression of CD86 (Fig. 2 A). In addition, TCM inhibited GM‐CSF‐induced expression of another costimulatory molecule, PD‐L2, which plays an important role in antigen‐presenting function (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

CT‐26 TCM promotes accumulation of monocytic MDSCs and macrophages. BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) and/or CT‐26 conditioned medium (25% of total volume). At Day 8, cells were collected, washed, stained with anti‐CD86 and ‐CD80 (A), F4/80 and PD‐L2 (B), or F4/80 and Ly‐6C (C) antibodies. (D) CT‐26 TCM was collected from ex vivo excised tumor (TCM) or from an in vitro‐cultured CT‐26 cell line (CT26 cell line CM). BM‐derived cells from naïve mice were cultured in the presence of TCM or CT26 cell line CM but in the absence of GM‐CSF. On Day 8, cells were collected and analyzed by flow cytometry for expression of Ly‐6C and F4/80 markers. Results of one representative experiment out of three are shown. APC F4/80, allophycocyanin‐F4/80.

It has been demonstrated previously that tumor‐derived factors could impair maturation or differentiation of BM‐derived APCs, and as a consequence, it promotes the accumulation of immature myeloid cells or MSDCs [26]. To this end, we examined whether CT‐26‐derived TCM could up‐regulate markers of MDSCs, such as Ly‐6G (granulocytic MDSC) and Ly‐6C (monocytic MDSC). Our results indicate that culturing of BM‐derived progenitors in the presence of TCM and GM‐CSF promotes up‐regulation of Ly‐6C (but not Ly‐6G) in ∼35% of BM‐derived myeloid cells (Fig. 2C). The rest of the cultured cells were positive for monocyte/macrophage marker F4/80 but not for DC marker CD11c (data not shown). It has to be noted that culturing of BM cells in the presence of TCM but in the absence of GM‐CSF resulted in much greater accumulation of Ly‐6C+F4/80+ MDSCs (∼90%; Fig. 2D, left panel). Interestingly, up‐regulation of Ly‐6C in myeloid cells could be achieved only by exposure of BM cells to TCM obtained from ex vivo‐excised CT‐26 tumors (Fig. 2D, left panel) but not TCM obtained from the in vitro‐cultured CT‐26 cell line (Fig. 2D, right panel).

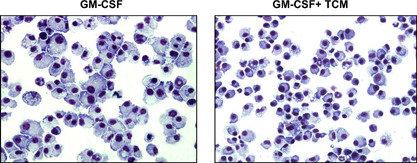

Cytospin slides stained with H&E show that CT‐26 TCM impairs the cytomorphology of BM‐derived APCs. Cells cultured in the presence of TCM showed characteristics of immature DCs or myeloid cell precursors. These characteristics include small and irregularly shaped cells with indented excentric nucleus (Fig. 3, right panel) as compared with normal, mature cells that have large and vacuolated, DC‐like cells (Fig. 3, left panel) but without veils that are typical for mature DCs. Taken together, our results demonstrate that the CT‐26 tumor skews the in vitro, GM‐CSF‐driven differentiation of mature APCs into M2‐oriented Ly6C+F4/80+ MDSCs or Ly6C–F4/80+ macrophages.

Figure 3.

CT‐26 TCM impairs morphology of myeloid cells. (A) BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) and/or CT‐26 conditioned media (25% of total volume) for 8 days using an ultra‐low attachment plate. At Day 8, cells were collected and stained with H&E and then analyzed under a light microscope.

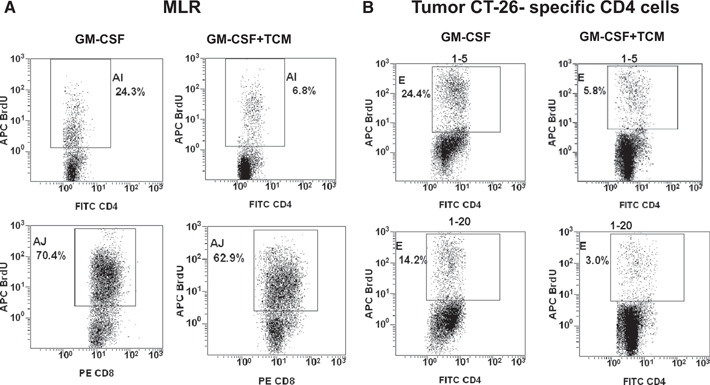

CT‐26 TCM diminishes the immune function of BM‐derived antigen‐presenting cells

Figure 4A shows the impaired ability of BM‐derived cells grown in the presence of CT‐26 TCM to stimulate naïve T cells in allogeneic MLR. Figure 4B demonstrates that the percent of antigen‐specific CD4 T cells incorporating BrdU (7% at ratio 1:10 and 4% at ratio 1:20) in the presence of BM cells grown with CT‐26 TCM is threefold lower as compared with the percent of a proliferating CD4 T cell (24% at ratio 1:10 and 14% at ratio 1:20), cocultured with CD11c+F4/80+ cells, generated in the presence of GM‐CSF alone.

Figure 4.

BM‐derived myeloid cells cultured in the presence of CT‐26 conditioned media show a diminished ability to stimulate antigen‐specific T cell proliferation. (A) MLR. BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) with added or not added CT‐26 TCM for 8 days. Purified, naïve T cells (1×105/well) from naïve C57/Bl/6 mice were mixed with titrated numbers of BALB/c BM cells grown with or without a CT‐26 TCM (ratio BM cell:T cell, 1:5 is shown). At Day 3, BrdU was added into cell cultures for 18 h. (B) Antigen‐specific proliferation of CD4 T cells. T lymphocytes were purified from spleens of immune mice (which were immunized twice previously with irradiated CT‐26 tumor cells). BM cells were grown as described above in A. T cells were mixed with titrated numbers of BM‐derived APCs. Then, cell cocultures were stimulated with irradiated, specific CT‐26 murine tumor cells. Forty‐eight hours later, BrdU was added in the cell cultures for 15 h. Proliferation of CD4 and CD8 T cells was assessed by flow cytometry. All experiments were repeated twice. Results of one representative experiment are shown. APC Brd U, allophycocyanin‐Brd U.

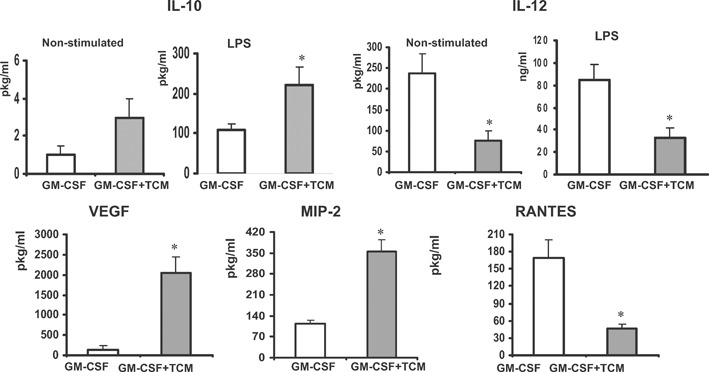

Furthermore, cells cultured in the presence of CT‐26 conditioned medium become M2‐oriented macrophages that produce high amounts of IL‐10 and low amounts of IL‐12 in response to LPS stimulation (Fig. 5, upper left and right panels, respectively). BM cells grown in the presence of CT‐26 TCM secreted significantly higher amounts of VEGF and MIP‐2 compared with the cells grown in absence of TCM (Fig. 5). Collectively, the obtained results suggest that CT‐26 TCM promotes differentiation of BM myeloid precursors into M2‐oriented, macrophage‐like cells or monocytic Ly‐6C‐positive MDSCs, despite the presence GM‐CSF.

Figure 5.

Exposure of BM‐derived myeloid cells to tumor‐derived factors promotes M2‐oriented cytokine profile. BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) and/or CT‐26 conditioned media (25% of total volume) for 8 days using an ultra‐low attachment plate. At Day 8, cells were collected, counted, and incubated in the presence of LPS (1 μg/ml) for 24 h. Then, cell supernatants were collected, filtered, and assayed for the presence of cytokines and growth factors using the Multiplex assay. *P < 0.05.

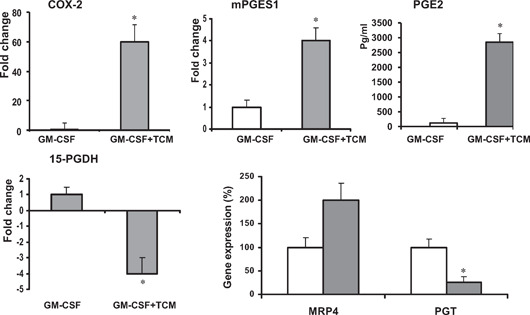

CT‐26 TCM up‐regulates the PGE2‐forming enzymes and down‐regulates expression of 15‐PGDH

The tumor microenvironment regulates the phenotype and functional activity of the recruited mononuclear phagocytes. PGE2 and COX‐2 (required for the conversion of arachidonic acid to PGE2) are major inflammatory mediators in the tumor microenvironment [14, 15]. It has been shown that enhanced secretion of PGE2 by tumor cells causes a reduced number of tumor‐infiltrating DCs and a reduction in their APC function.

Here, we demonstrate that tumor‐mediated inhibition of GM‐driven differentiation of BM progenitors was associated with highly induced gene expression of PGE2‐forming enzymes COX‐2 and mPGES1 in myeloid cells as well as with increased PGE2 production (Fig. 6, upper panel). These changes were associated with simultaneous repression of PGE2‐catabolizing enzyme 15‐PGDH (Fig. 6, lower panel). Intracellular PGE2 metabolism has been linked earlier to PGE2‐transporting receptors such as PGT and MRP4. Therefore, we evaluated the effect of the CT‐26 TCM on PGT and MRP4 expression in the BM‐derived myeloid APC (Fig. 6, lower right panel). Our results indicate that the presence of TCM promoted up‐regulation of MRP4 expression but inhibited expression of PGT. Significant up‐regulation of MRP4 gene expression was also detected in tumor‐infiltrated CD11b myeloid cells isolated from CT‐26 tumor‐bearing mice (data not shown). Together, our data suggest that tumor‐mediated, aberrant differentiation of BM‐derived APCs is associated with marked changes in the expression of enzymes and receptors participating in PGE2 metabolism/catabolism, thus favoring its enhanced formation and reduced intracellular degradation.

Figure 6.

Tumor‐mediated alteration of PGE2‐related gene expression in myeloid cells. (A) BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) and/or CT‐26 conditioned media (25% of total volume) for 8 days using an ultra‐low attachment plate. On Day 8, cells were collected, washed, and lysed for RNA isolation. Total cellular RNA was isolated from cells with RNeasy reagent (Qiagen). Quantitative real‐time RT‐PCR analysis was performed using an Applied Biosystems Prism 7900HT fast real‐time PCR system. To examine the effect of TCM on PGE2 production, BM‐derived cells were cultured with or without TCM for 8 days, washed with PBS twice, and incubated for an additional 24 h to collect supernatants. PGE2 levels of cell supernatants were determined using an ELISA kit from Cayman Chemical. All samples were run in triplicates. *P < 0.05.

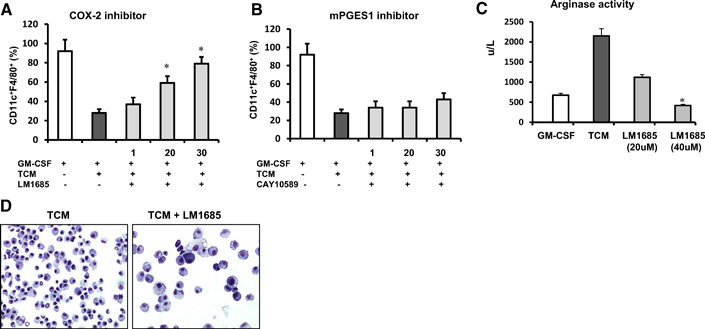

The inhibition of COX‐2 activity in BM cells cultured in the presence of CT‐26 TCM partially restores the development of BM‐derived antigen‐presenting cells

Previous studies demonstrated that inhibition of COX‐2 in tumor‐bearing mice could improve anti‐tumor immune response and increase overall survival [8, 27, –, 29]. These effects have been linked to the inhibition of COX‐2 activity in tumor cells. The data obtained in this study strongly suggest that tumors could also impair the PGE2 catabolism in BM‐derived myeloid cells through simultaneous stimulation of PGE2‐forming enzymes and inhibition of PGE2‐degrading enzymes. This dichotomy could potentially influence the observed tumor‐mediated regulation of APC differentiation and function. Therefore, we asked whether the inhibition of COX‐2 activity in BM‐derived myeloid cells grown in the presence of CT‐26 TCM and GM‐CSF could improve in vitro APC development. A selective inhibitor of COX‐2 LM‐1685 was added to the BM cell cultures with CT‐26 TCM. Obtained results indicate that inhibition of COX‐2 could partially restore expression of CD11c in myeloid cells cultured in the presence of tumor‐derived factors in a dose‐dependent manner (Fig. 7 A). We also examined whether inhibition of another PGE2‐forming enzyme mPGES1 could prevent down‐regulation of CD11c expression in myeloid cells exposed to TCM. However, the effect of selective inhibitor, mPGES1, CAY10589 was negligible (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The inhibition of COX‐2 activity in BM precursors partially restores the development of APCs. BM cells were cultured in the presence of GM‐CSF and/or CT‐26 TCM. Inhibitors of COX‐2 or mPGES1 were added on Day 0 at indicated concentrations. (A and B) On Day 8, cells were collected, and expression of CD11c and F4/80 was assessed using flow cytometry. Results of one representative experiment out of four are shown. (C) Effect of COX‐2 inhibitor on tumor‐induced arginase activity in myeloid cell lysates was evaluated using the quantitative colorimetric arginase assay kit as described in Materials and Methods. Average means ± sd are shown. (D) Cytospin slides were stained with H&E and analyzed under a light microscope. *P < 0.05.

One of the key features of TAMs and MDSCs in tumor host is high expression of arginase I. Arginase depletes arginine, which is an essential amino acid for T cell activation [30, 31]. As shown in Figure 7C, culturing of BM‐derived cells in the presence of CT‐26 TCM promotes increased arginase activity in those cells as compared with cells grown in the presence of GM‐CSF only. Adding COX‐2 inhibitor to the cell cultures could prevent the tumor‐induced arginase activation completely in myeloid cells. In addition, the inhibition of COX‐2 could improve the morphology of cells cultured in the presence of CT‐26 TCM (Fig. 7D).

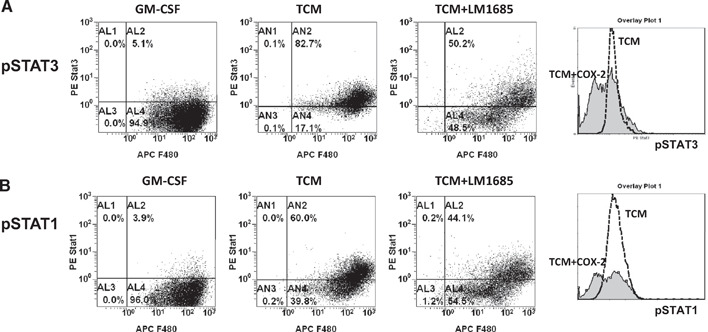

Tumor‐induced COX‐2 involved in tumor‐mediated up‐regulation of Stat3/Stat1 activity in BM‐derived myeloid cells

Enhanced phosphorylation of Stat3 and Stat1 in myeloid cells derived from tumor‐bearing mice has been implicated in abnormal differentiation of DCs and tumor‐induced immune suppression in the tumor host [26, 28]. Here, we examined whether tumor‐mediated, enhanced PGE2 metabolism could contribute to the activation of Stat3 and Stat1 in BM‐derived myeloid cells. Figure 8 shows that the addition of CT‐26 TCM to the BM‐derived cells promotes phosphorylation of Stat3 and Stat1 in most myeloid cells (phospho‐Stat3: 82.7% in the presence of TCM vs. 5.1% in control; phospho‐Stat1: 60.0% in the presence of TCM vs. 3.9% in control). The data are consistent with reports published previously [26, 28]. Addition of COX‐2 inhibitor to the BM‐derived cells could partially reverse the activation of Stat3 (Fig. 8A) as well as Stat1 (Fig. 8B). The results suggest that tumor‐induced COX‐2 up‐regulation in myeloid cells contributes to the tumor‐mediated activation of Stat3 and Stat1.

Figure 8.

Tumor‐induced COX‐2 contributes to tumor‐mediated activation of Stat3/Stat1 in BM‐derived myeloid cells. BM cells from naïve BALB/c mice were cultured in the presence of mouse rGM‐CSF (20 ng/ml) or CT‐26 conditioned media (25% of total volume) in an ultra‐low attachment plate for 6 days. The COX‐2 inhibitor was added at a final concentration of 40 μM. On Day 6, cells were collected, washed in PBS, and fixed immediately in BD Phosflow lyse/fix buffer (BD Biosciences). Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of phospho‐Stat1 (pSTAT1; pY701) and phospho‐Stat3 (pSTAT3; pY705) was performed using BD Phosflow technology (BD Biosciences).

DISCUSSION

A substantial part of inflammatory tumor‐infiltrated cells is represented by recruited BM‐derived CD11b myeloid cells [15, 32] that potentially differentiate into APCs and generate the anti‐tumor immune response. However, the tumor microenvironment is unfavorable for initiation of an effective anti‐tumor immune response [33, 34]. Tumor‐derived factors and local environmental conditions in the tumor vicinity regulate the function of tumor‐infiltrated APCs and subsequently convert recruited, BM‐derived myeloid cells into tumor‐supporting cells such as immunosuppressive, proangiogenic TAMs, MDSCs, or regulatory/vasculogenic DCs [9, 10, 26, 35, –, 37, 38, 39, 40].

One of the major tumor‐derived factors that affect myeloid cells in a tumor‐bearing host is PGE2. It has been shown that tumor‐derived PGE2 binds directly to myeloid cells through selective PGE2 receptors EP2 and EP4. Enhanced EP2/EP4 PGE2‐mediated signaling leads to induction of arginase I expression [8], inhibition of DC differentiation [2, 11], and increased secretion of matrix metallopeptidase 9 [41].

On the other hand, increased expression of PGE2‐forming enzymes, such as inducible COX‐2 and mPGES1, has been detected, not only in cancer cells but also in inflammatory tumor‐infiltrated myeloid cells [16]. The exact mechanism of the up‐regulation of COX‐2 in tumor‐infiltrated CD11b is currently unknown. Recent studies suggest multiple mechanisms for induction of COX‐2 in myeloid cells, including hypoxia [42], TLR signaling [43], proinflammatory cytokines, or cell activation via adherence to extracellular matrix. In our study, we demonstrate that expression of COX‐2 and mPGES1 can occur in BM‐derived myeloid cells by their exposure to TCM. COX‐2 expression was not induced in our experiments by cell adherence to plastic, as in this study, we specifically used the “ultra‐low attachment cell culture plates” that prevent cell adherence to the surface. Similarly to COX‐2, the presence of tumor‐derived factors promoted expression of another major PGE2‐forming enzyme, mPGES1.

Levels of bioactive PGE2 in cells are regulated by NAD+‐linked 15‐PGDH, a key enzyme responsible for the biological inactivation of PGs. 15‐PGDH catalyzes the oxidation of the 15(S)‐hydroxyl group of PGs, resulting in the formation of 15‐keto‐PGs, which exhibit greatly reduced biological activities [44]. In addition, this enzyme participates in inactivation of other lipid products such as leukotrienes [45]. 15‐PGDH has been identified as a tumor‐suppressor gene for several human cancers including colon, lung, breast, and bladder cancer [46, –, 48]. Deficiency of 15‐PGDH is associated with resistance to COX‐2 inhibitor celecoxib in an animal model of colon cancer prevention [49]. 15‐PGDH is involved in regulation of local anti‐tumor immune response via leveraging of bioactive PGE2 levels in tissues [15] and possibly also contributes to regulation of cancer‐related inflammation through degradation of leukotrienes and PGs.

Previous studies have shown that expression and catabolic activity of 15‐PGDH are decreased frequently in cancer tissues. We have demonstrated recently that local overexpression of the 15‐PGDH gene at the tumor site can reduce PGE2 levels significantly in the tumor microenvironment and promote a therapeutic anti‐tumor immune response [15]. Thus, forced expression or pharmacological stimulation of 15‐PGDH in the tumor microenvironment through recombinant expression vectors or other gene‐delivery strategies may represent an effective approach to reduce intratumoral PGE2 levels and promote effective anti‐tumor immune responses.

In the present study, we describe that exposure of BM‐derived myeloid cells to TCM results in the down‐regulation of a major PGE2‐catabolizing enzyme, 15‐PGDH. Our results are consistent with reports published previously showing that tumor‐infiltrated CD11b myeloid cells isolated from murine colon or prostate tumors lack 15‐PGDH gene expression [15]. Recent studies suggest that PGE2 catabolic function of 15‐PGDH has been linked to PGT, a specialized membrane receptor that provides transport of PGE2 into cells directly to 15‐PGDH for its further degradation [50]. Here, we show that expression of intracellular elements participating in PGE2 degradation, such as PGT and 15‐PGDH, is down‐regulated in TCM‐treated, BM‐derived myeloid cells. Decreased expression of 15‐PGDH and PGT in myeloid cells results in reduced catabolism of intracellular PGs and promotes elevated intracellular levels of PGE2. Another molecule affected after exposure to the tumor‐derived factors was MRP4, which is a member of the ATP‐binding cassette family of membrane transporters involved in the efflux of endogenous molecules, including PGs. It is plausible that tumor‐increased expression of MRP4 promotes the enhanced efflux of newly formed PGE2 and other bioactive substances out from myeloid cells to the extracellular space.

The tumor‐induced impairment of the PGE2 metabolism was associated with significant phenotypic and functional changes in myeloid cells. Exposure of BM myeloid progenitor cells to tumor‐derived factors resulted in inhibition of GM‐CSF‐driven APC differentiation, which can be judged by the reduction of antigen‐presenting function coupled with decreased expression of mature APC markers CD11c and MHC class II and enhanced expression of CD80 and arginase I. Furthermore, TCM‐treated BM cells secreted elevated levels of IL‐10, MIP‐2, and VEGF. The morphology of cells exposed to TCM was reminiscent of morphology of macrophage‐like cells or MDSCs. The addition of the COX‐2 inhibitor to the culture could prevent the tumor‐induced skewing of DC differentiation to macrophages, partially restoring DC cell phenotype and down‐regulating the arginase expression in myeloid APCs. These data are consistent with reports published previously showing that PGE2 is involved in tumor‐mediated inhibition of APC function and differentiation/maturation, as well as in induction of immunosuppressive myeloid cells [1, 2, 8, 11, 12, 15].

Remarkably, TCM promotes differentiation of BM‐derived APCs into M2‐oriented, immunosuppressive, macrophage‐like cells, even in the presence of GM‐CSF. This may explain the ineffectiveness of GM‐CSF‐based cancer vaccines administered in the tumor host. GM‐CSF has the ability to mobilize the myeloid progenitors from BM into peripheral blood lymphoid organs and then stimulate DC differentiation in tissues, thus promoting an anti‐tumor immune response. However, administration of GM‐CSF in a tumor‐bearing host frequently results in immunosuppression mediated by GM‐CSF‐induced MDSCs [51, 52]. Results obtained in our study suggest that coadministration of COX‐2 inhibitors or other agents that target PGE2 metabolism could improve the therapeutic efficacy of GM‐CSF cancer vaccines by preventing the tumor‐induced, PGE2‐dependent differentiation of immunostimulating APCs into immunosuppressive, macrophage‐like cells or MDSCs.

The tumor microenvironment in inflammation‐associated cancers is rich for PGs [14, 15]. It is likely that freshly recruited BM‐derived myeloid APC precursors could experience a strong PGE2‐mediated impact in the tumor vicinity as a result of high concentrations of extracellular PGE2 secreted by surrounding tumor cells and tumor‐induced endogenous expression of COX‐2 and mPGES1 in recruited myeloid cells. Furthermore, tumors also repress PGE2‐catabolizing enzyme 15‐PGDH and 15‐PGDH‐linked PGT, thus promoting elevated levels of bioactive lipids in myeloid cells. We suggest that tumor‐induced up‐regulation of COX‐2 and 15‐PGDH down‐regulation in tumor‐infiltrated CD11b myeloid cells may play a significant role in the tumor‐induced immune dysfunction, leading to tumor escape from the immune system.

We also suggest that the described mechanism may have a physiological relevance for some inflammation‐associated cancers, including colon, lung, bladder, and prostate, and possibly in other cancers. Correction of intracellular catabolism in BM‐derived myeloid cells in those cancers could represent a target for cancer therapy and provide a new direction for regulation of local and systemic anti‐tumor immune responses.

AUTHORSHIP

E.E. performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper; I.D. performed research and analyzed data; J.O. performed research; J.V. wrote the paper; and S.K. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sharma, S., Stolina, M., Yang, S. C., Baratelli, F., Lin, J. F., Atianzar, K., Luo, J., Zhu, L., Lin, Y., Huang, M., Dohadwala, M., Batra, R. K., Dubinett, S. M. (2003) Tumor cyclooxygenase 2‐dependent suppression of dendritic cell function. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 961–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang, L., Yamagata, N., Yadav, R., Brandon, S., Courtney, R. L., Morrow, J. D., Shyr, Y., Boothby, M., Joyce, S., Carbone, D. P., Breyer, R. M. (2003) Cancer‐associated immunodeficiency and dendritic cell abnormalities mediated by the prostaglandin EP2 receptor. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 727–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harizi, H., Juzan, M., Pitard, V., Moreau, J‐F., Gualde, N. (2002) Cyclooxygenase‐ 2‐issued prostaglandin E (2) enhances the production of endogenous IL‐10, which down‐regulates dendritic cell functions. J. Immunol. 168, 2255–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sombroek, C. C., Stam, A. G. M., Masterson, A. J., Lougheed, S. M., Schakel, M. J. A. G., Meijer, C. J. L. M., Pinedo, H. M., van den Eertwegh, A. J. M., Scheper, R. J., de Gruijl, T. D. (2002) Prostanoids play a major role in the primary tumor‐induced inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 168, 4333–4343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ménétrier‐Caux, C., Bain, C., Favrot, M. C., Duc, A., Blay, J. Y. (1999) Renal cell carcinoma induces interleukin 10 and prostaglandin E2 production by monocytes. Br. J. Cancer 79, 119–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yao, C., Sakata, D., Esaki, Y., Li, Y., Matsuoka, T., Kuroiwa, K., Sugimoto, Y., Narumiya, S. (2009) Prostaglandin E2‐EP4 signaling promotes immune inflammation through Th1 cell differentiation and Th17 cell expansion. Nat. Med. 15, 633–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma, S., Yang, S. H., Zhu, L., Reckamp, K., Gardner, B., Baratelli, B., Huang, M., Batra, R., Dubinett, S. M. (2005) Tumor cyclooxygenase‐2/prostaglandin E2‐dependent promotion of FOXP3 expression and CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cell activities in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 65, 5211–5220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez, P. C., Hernandez, C. P., David Quiceno, D., Dubinett, S. M., Zabaleta, J., Ochoa, J. B., Gilbert, G., Ochoa, A. C. (2005) Arginase I in myeloid suppressor cells is induced by COX‐2 in lung carcinoma. J. Exp. Med. 202, 931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez, P. C., Quiceno, D. G., Zabaleta, J., Ortiz, B., Zea, A. H., Piazuelo, M. B., Delgado, A., Correa, P., Brayer, J., Sotomayor, E. M., Antonia, S., Ochoa, J. B., Ochoa, A. C. (2004) Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T‐cell receptor expression and antigen‐specific T‐cell responses. Cancer Res. 64, 5839–5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kusmartsev, S., Gabrilovich, D. (2005) STAT1 signaling regulates tumor‐associated macrophage‐mediated T cell deletion. J. Immunol. 174, 4880–4891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sinha, P., Clements, V. K., Fulton, A. M., Ostrand‐Rosenberg, S. (2007) Prostaglandin E2 promotes tumor progression by inducing myeloid‐derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 67, 4507–4513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talmadge, J. E., Hood, K., Zobel, L., Shafer, L., Coles, M., Toth, B. (2006) Chemoprevention by cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibition reduces immature myeloid suppressor cell expansion. Int. Immunopharmacol. 7, 140–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dannenberg, A. J., Subbaramaiah, K. (2003) Targeting cyclooxygenase‐2 in human neoplasia: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell 4, 431–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang, D., Dubois, R. N. (2006) Prostaglandins and cancer. Gut 55, 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eruslanov, E., Kaliberov, S., Daurkin, I., Kaliberova, L., Buchsbaum, D., Vieweg, J., Kusmartsev, S. (2009) Altered expression of 15‐hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase in tumor‐infiltrated CD11b myeloid cells: a mechanism for immune evasion in cancer. J. Immunol. 182, 7548–7557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klimp, A. H., Hollema, H., Kempinga, C., van der Zee, A. G., de Vries, E. G., Daemen, T. (2001) Expression of cyclooxygenase‐2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase in human ovarian tumors and tumor‐associated macrophages. Cancer Res. 61, 7305–7309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaba, K., Inaba, M., Romani, N., Aya, H., Deguchi, M., Ikehara, S., Muramatsu, S., Steinman, R. M. (1992) Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/ macrophage colony‐stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 176, 1693–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lutz, M. B., Kukutsch, N., Ogilvie, A. L., Rößner, S., Kochb, F., Romanib, N., Schuler, G. (1999) An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223, 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang, A., Bloom, O., Ono, S., Cui, W., Unternaehrer, J., Jiang, S., Whitney, J. A., Connolly, J., Banchereau, J., Mellman, I. (2007) Disruption of E‐cadherin‐mediated adhesion induces a functionally distinct pathway of dendritic cell maturation. Immunity 27, 610–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard, J. W. (2004) Tumor‐educated macrophages promote tumor progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mantovani, A., Schioppa, T., Porta, C., Allavena, P., Antonio Sica, A. (2006) Role of tumor‐associated macrophages in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 25, 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kusmartsev, S., Gabrilovich, D. (2006) Role of immature myeloid cells in mechanisms of immune evasion in cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 55, 237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabrilovich, D. (2004) The mechanisms and functional significance of tumor‐induced dendritic‐cell defects. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 941–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kusmartsev, S., Gabriovich, D. (2006) Effect of tumor‐derived cytokines and growth factors on differentiation and immune suppressive features of myeloid cells in cancer. Cancer Rev. Metastasis 25, 323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nefedova, Y., Huang, M., Kusmartsev, S., Bhattacharya, R., Cheng, P., Salup, R., Jove, R., Gabrilovich, D. (2004) Hyperactivation of STAT3 is involved in abnormal differentiation of dendritic cells in cancer. J. Immunol. 172, 464–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagaraj, S., Gabrilovich, D. (2009) Myeloid‐derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 162–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.DeLong, P., Tanaka, T., Kruklitis, R., Henry, A. C., Kapoor, V., Kaiser, L. R., Sterman, D. H., Albelda, S. M. (2003) Use of cyclooxygenase‐2 inhibition to enhance the efficacy of immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 63, 7845–7852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma, S., Zhu, L., Yang, S. C., Zhang, L., Lin, J., Hillinger, S., Gardner, B., Reckamp, K., Strieter, R. M., Huang, M., Batra, R. K., Dubinett, S. M. (2005) Cyclooxygenase 2 inhibition promotes IFN‐γ‐dependent enhancement of antitumor responses. J. Immunol. 175, 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stolina, M., Sharma, S., Lin, Y., Dohadwala, M., Gardner, B., Luo, J., Zhu, L., Kronenberg, M., Miller, P. W., Portanova, J. P., Lee, J. C., Dubinett, S. M. (2000) Specific inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 restores antitumor reactivity by altering the balance of IL‐10 and IL‐12 synthesis. J. Immunol. 164, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodriguez, P. C., Ochoa, A. C. (2008) Arginine regulation by myeloid derived suppressor cells and tolerance in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic perspectives. Immunol. Rev. 222, 180–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sica, A., Bronte, V. (2007) Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 1155–1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, B., Bowerman, N. B., Salama, J. K., Schmidt, H., Spiotto, M. T., Schietinger, A., Yu, P., Fu, Y‐X., Weichselbaum, R. R., Rowley, D. A., Kranz, D. M., Schreiber, H. (2007) Induced sensitization of tumor stroma leads to eradication of established cancer by T cells. J. Exp. Med. 204, 49–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zou, W. (2005) Immunosuppressive networks in the tumor environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 263–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kusmartsev, S., Vieweg, J. (2009) Enhancing efficacy of cancer vaccines in urologic oncology: new directions. Nat. Rev. Urol. 6, 540–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Norian, L. A., Rodriguez, P. C., O'Mara, L. A., Zabaleta, J., Ochoa, A. C., Cella, M., Allen, P. M. (2009) Tumor‐infiltrating regulatory dendritic cells inhibit CD8+ T cell function via L‐arginine metabolism. Cancer Res. 69, 3086–3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Conejo‐Garcia, J. R., Benencia, F., Courreges, M‐C., Kang, E., Mohamed‐Hadley, A., Buckanovich, R. J., Holtz, D. O., Jenkins, A., Na, H., Zhang, L., Wagner, D. S., Katsaros, D., Caroll, R., Coukos, G. (2004) Tumor‐infiltrating dendritic cell precursors recruited by a β‐defensin contribute to vasculogenesis under the influence of Vegf‐A. Nat. Med. 10, 950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ostrand‐Rosenberg, S. (2008) Immune surveillance: a balance between protumor and antitumor immunity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 18, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mantovani, A., Allavena, P., Sica, A., Balkwill, F. (2008) Cancer‐related inflammation. Nature 454, 436–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murdoch, C., Muthana, M., Coffelt, S. B. (2008) The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumor angiogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 618–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vieweg, J., Su, Z., Dahm, P., Kusmartsev, S. (2007) Reversal of tumor‐induced immune suppression. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 727s–732s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yen, J. H., Khayrullina, T., Ganea, D. (2008) PGE2‐induced metalloproteinase‐ 9 is essential for dendritic cell migration. Blood 111, 260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fang, H‐Y., Hughes, R., Murdoch, C., Coffelt, S. B., Biswas, S. K., Harris, A. L., Johnson, R. S., Imityaz, H. Z., Simon, M. C., Fredlund, E., Greten, F. R., Rius, J., Lewis, C. E. (2009) Hypoxia inducible factors 1 and 2 are important transcriptional effectors in primary macrophages experiencing hypoxia. Blood 114, 844–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rakoff‐Nahoum, S., Paglino, J., Eslami‐Varzaneh, F., Edberg, S., Medzhitov, R. (2004) Recognition of commensal microflora by Toll‐like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118, 229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tai, H. H., Cho, H., Tong, M., Ding, Y. (2006) NAD +‐linked 15‐hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase: structure and biological functions. Curr. Pharm. Des. 12, 955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clish, C. B., Levy, B. D., Chiang, N., Tai, H. H., Serhan, C. N. (2000) Oxidoreductases in lipoxin A4 metabolic inactivation: a novel role for 15‐onoprostaglandin 13‐reductase/leukotriene B4 12‐hydroxydehydrogenase in inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25372–25380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myung, S. J., Rerko, R. M., Yan, M., Platzer, P., Guda, K., Dotson, A., Lawrence, E., Dannenberg, A. J., Lovgren, A. K., Luo, G., Pretlow, T. P., Newman, R. A., Willis, J., Dawson, D., Markowitz, S. D. (2006) 15‐Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is an in vivo suppressor of colon tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12098–12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ding, Y., Tong, M., Moscow, J. A., Tai, H. H. (2005) NAD +‐linked 15‐ hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15‐PGDH) behaves as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer. Carcinogenesis 26, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf, I., O'Kelly, J., Rubinek, T., Tong, M., Nguyen, A., Lin, B. T., Tai, H. H., Karlan, B. Y., Koeffler, H. P. (2006) 15‐Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase is a tumor suppressor of human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 66, 7818–7823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yan, M., Myung, S‐J., Fink, S. P., Lawrence, E., Lutterbaugh, J., Yang, P., Zhou, X., Liu, D., Rerko, R. M., Willis, J., Dawson, D., Tai, H. H., Barnholtz‐Sloan, J. S., Newman, R. A., Bertagnolli, M. M., Markowitz, S. D. (2009) 15‐Hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase inactivation as a mechanism of resistance to celecoxib chemoprevention of colon tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9409–9413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nomura, T., Lu, R., Pucci, M. L., Schuster, V. L. (2004) The two‐step model of prostaglandin signal termination: in vitro reconstitution with the prostaglandin transporter and prostaglandin 15 dehydrogenase. Mol. Pharmacol. 65, 973–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bronte, V., Chappell, D. B., Apolloni, E., Cabrelle, A., Wang, M., Hwu, P., Restifo, N. P. (1999) Unopposed production of granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor by tumors inhibits CD8+ T cell responses by dysregulating antigen‐presenting cell maturation. J. Immunol. 162, 5728–5737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parmiani, G., Castelli, C., Pilla, L., Santinami, M., Colombo, M. P., Rivoltini, L. (2007) Opposite immune functions of GM‐CSF administered as vaccine adjuvant in cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 18, 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]