Abstract

Objectives

One Health is transiting from multidisciplinary to transdisciplinary concepts and its viewpoints should move from ‘proxy for zoonoses’, to include other topics (climate change, nutrition and food safety, policy and planning, welfare and well-being, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), vector-borne diseases, toxicosis and pesticides issues) and thematic fields (social sciences, geography and economics). This work was conducted to map the One Health landscape in Africa.

Methods

An assessment of existing One Health initiatives in Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries was conducted among selected stakeholders using a multi-method approach. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to One Health initiatives were identified, and their influence, interest and impacts were semi-quantitatively evaluated using literature reviews, questionnaire survey and statistical analysis.

Results

One Health Networks and identified initiatives were spatiotemporally spread across SSA and identified stakeholders were classified into four quadrants. It was observed that imbalance in stakeholders' representations led to hesitation in buying-in into One Health approach by stakeholders who are outside the main networks like stakeholders from the policy, budgeting, geography and sometimes, the environment sectors.

Conclusion

Inclusion of theory of change, monitoring and evaluation frameworks, and tools for standardized evaluation of One Health policies are needed for a sustained future of One Health and future engagements should be outputs- and outcomes-driven and not activity-driven. National roadmaps for One Health implementation and institutionalization are necessary, and proofs of concepts in One Health should be validated and scaled-up. Dependence on external funding is unsustainable and must be addressed in the medium to long-term. Necessary policy and legal instruments to support One Health nationally and sub-nationally should be implemented taking cognizance of contemporary issues like urbanization, endemic poverty and other emerging issues. The utilization of current technologies and One Health approach in addressing the ongoing pandemic of COVID-19 and other emerging diseases are desirable. Finally, One Health implementation should be anticipatory and preemptive, and not reactive in containing disease outbreaks, especially those from the animal sources or the environment before the risk of spillover to human.

Keywords: One health (OH), Africa, Public health, Animal health, Environment health, Zoonosis, Emerging and re-emerging diseases, Food safety, Antimicrobial resistance, Toxicosis

Abbreviations: ACDC, Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention; AFROHUN, Africa One Health University Network; AMR, Antimicrobial resistance; AMU, Arab Maghreb Union; AU, African Union; AU-IBAR, African Union Inter-African Bureau for Animal Resources; BSL-3, Biosafety level 3 laboratory; BMGF, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; CEMAC, Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa; CILSS, Permanent Inter-State Committee for Drought Control in the Sahel; COCTU, Control of Trypanosomiasis in Uganda; COMESA, Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa; EAC, East African Community; ECCAS, Economic Community of Central African States; ECOWAS, Economic Community of West African States; COVID-19, Coronavirus (SARS CoV 2) disease 2019; FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; FELTP, Field Epidemiology & Laboratory Training Program; GARC, Global Alliance for Rabies Control; GHSA-ZDAH, Global Health Security Agenda's Zoonotic Diseases and Animal Health in Africa; GIS, Geographic information system; HPAI H5N1, Highly pathogenic avian influenza subtype H5N1; IGAD, Intergovernmental Authority on Development; ILRI, International Livestock Research Institute; ISAVET, Frontline In-Service Applied Veterinary Epidemiology Training; IRA, Institute for Resource Assessment; KEMRI, Kenya Medical Research Institute; MALF, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries; M & E, monitoring and evaluation; MoH, Ministry of Health; MRU, Mano River Union; NISCAI, National Inter-Ministerial Steering Committee on Avian Influenza; NTCAI, National Technical Committee on Avian Influenza; OH, One Health; OIE, World Organization for Animal Health; PMP, Progressive Management Pathway; RECs, regional economic commissions; RVF, Rift Valley fever; UNICEF, United Nations Children's Fund; UNSIC, United Nations System Influenza Coordination; USAID, United States Agency for International Development; SACIDS, Southern African Centre for Infectious Disease Surveillance; SACU, South African Customs Union; SADC, South African Development Community; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa; SWOT, Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats; WAEMU, West African Economic and Monetary Union; WHO, World Health Organization; ZDU, Zoonotic Disease Unit.

Highlights

-

•

One Health transcends multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary concepts; it’s expanding scope to cover ignored fields;

-

•

Mapping the One Health landscape in Africa is desirable for effective monitoring and evaluation, and measurable outcomes;

-

•

Development of national roadmaps is necessary for One Health institutionalization and to develop targeted activities;

-

•

Anticipatory and not reactive One Health implementation optimizes its benefits at addressing countries’ challenges.

1. Introduction

One Health (OH) is the collaborative effort of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally, and globally, to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment [1,2]. Incontestably, humans coexist with animals in complex yet interdependent relationships in the environment. These relationships present opportunities to share resources and diseases that influence public, animal and environment health as well as impacts human socio-economics [3]. To achieve the goals of One Health and address potential or existing global and transnational health risks, One Health-related policies and solutions should be systematic, coordinated, collaborative, multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral in outlooks [4,5]. Identified health risks associated with known interfaces (human-livestock-wildlife-environmental) include: diseases (zoonotic [6,7], non-zoonotic, non-communicable, emerging & re-emerging [8], vector-borne), toxicosis, climate change and pesticides [4,9,10].

Notably, One Health has gained major traction in the past two decades. The rapid adoption of One Health concepts globally has resulted in more than 100 One Health networks, with some 24 initiatives previously reported from Africa [11]. Currently, the foci of One Health platforms include coordination, organization, collaboration, communication, capacity building, information sharing, tool development and joint research [11] (Supplementary Table 1: http://bit.ly/ohafrica). However, a standardized evaluation tool for One Health policies at all levels needs to be developed.

The detailed history of One Health has been described [12,13] (Table 1). Briefly, Hippocrates first recognized the role of environmental factors and its impact on human health, thus promoting the concept that public health depended on a clean environment. Rudolf Virchow and William Osler recognized the link between animal and human medicine, and coined the name ‘zoonosis’ and advocated for veterinary medical education [2]. James Steele founded the Veterinary Public Health Division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, in 1947, and contributed significantly to the understanding of the epidemiology of zoonotic diseases. Calvin Schwabe coined the term ‘one medicine’ in a veterinary medical textbook in 1964. The twelve Manhattan Principles, formed in 2004 [14], established links between humans, animals, and the environment; how these links are integral to understanding disease dynamics, and the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to prevention, education, investment, and policy development [15].

Table 1.

Chronological transition and major One Health initiatives⁎

| S No. | Contributor(s)/ Organization(s)/Event(s) & timeline(s) | Contributions to One Health advancement |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hippocrates (460–370 BCE) | Recognized the role of environmental factors and impact on human healtha. |

| 2 | Rudolf Virchow & William Osler (1821–1902) | Recognized the link between animal and human medicine, and coined the name ‘zoonosis’ b. |

| 3 | James Steele (1947) | Veterinarian who was trained in public health who founded the Veterinary Public Health Division at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in Atlanta, in 1947. His works contributed significantly to the understanding of the epidemiology of zoonotic diseases b. |

| 4 | Calvin Schwabe (1927–2006) | A veterinarian trained in public health, coined the term One Medicine in a veterinary medical textbook in 1964 b. |

| 5 | Wildlife Conservation Society (2004) | The twelve Manhattan Principles were created in Rockefeller University, New York. They showed the links between humans, animals, and the environment. Also showed how these integrate understanding disease dynamics, and the importance of interdisciplinary approaches to prevention, education, investment, and policy development c |

| 6 | American Veterinary Medical Association (2006) | Established One Health Initiative Task Force d. |

| 7 | American Medical Association (2007) | Passed a One Health resolution to promote partnering between veterinary and human medical organizations. Recommended One Health approach for responses to global disease outbreaks e. |

| 8 | International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza (2007) | Developed the One Health concept and strengthened linkages between the human and animal health systems especially for the pandemic preparedness and human security, New Delhi e. |

| 9 | International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza in Egypt (2008) | Development of a framework titled ‘Contributing to One World, One Health-A Strategic Framework for Reducing Risks of Infectious Diseases at the Animal-Human-Ecosystems Interface’, with key recommendations for One Health approach to global health e,f. |

| 10 | International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza (2008) | Adoption of the developed framework on ‘Contributing to One World, One Health-A Strategic Framework for Reducing Risks of Infectious Diseases at the Animal-Human-Ecosystems Interface’ at Sharm El Sheik g. |

| 11 | FAO/OIE/WHO/UNSIC/ UNICEF/WB (2008) | Development of the implementable policies on One Health finalized in 2010 at the Stone Mountain, Georgia e. |

| 12 | Centers for Disease Prevention and CDC (2009) | Establishment of a One Health Office to serve as a point of contact for external animal health organizations which would aim at procuring external funding. The office has since expanded its role to support public health, facilitate data exchange, implement zoonotic disease prioritization and enhance cross-disciplinary research across sectors |

| 13 | USAID (2009) | Launching of the Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) program to ensure a coordinated comprehensive international effort to prevent, detect and respond to emergence of animal-origin diseases that could threaten human health. |

| 14 | Public Health Agency of Canada (2009) | Held One World, One Health Expert Consultation meeting, Winnipeg, Canada |

| 15 | International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza (2010) | Expansion of the above jointly-developed framework the organizations involved also developed implementable policies on One Health and the development of six workshops |

| 16 | International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza (2010) | Adoption of the Hanoi Declaration (focused attention at the animal-human-ecosystem interface), Hanoi, Vietnam |

| 17 | WB and UN (2010) | Joint release of the ‘Fifth Global Progress Report on Animal and Pandemic Influenza’ |

| 18 | EU (2011) | Published a report on ‘Outcome and Impact Assessment of the Global Response to the Avian Influenza Crises: 2005–2010’ h. |

| 19 | 1st international One Health Congress (IOHC) (2011) | Meeting was held in Melbourne, Australia e,i. |

| 20 | The International Congress on Pathogens at the Human-Animal Interface (ICOPHAI) (2011, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019) | To address important challenges and needs for capacity building in the field of One Health, an inaugural ICOPHAI congress was held at the United Nations Conference Center (UNCC) in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in 2011, followed by the 2nd in Porto de Galinhas, Brazil (2013), 3rd in Chiang-Mai, Thailand (2015) and 4th in Doha, Qatar (2017) and the 5th conference was held in Quebec, Canada. |

| 21 | 1st One Health Conference in Africa (2011) | Meeting was held in Johannesburg, South Africa e,i. |

| 22 | High-Level Tripartite Technical meeting (2011) | Considered the Tripartite Concept Note and addressed health risks that occurred in the different geographic regions using three selected diseases and issue (rabies, influenza and antimicrobial resistance) as points of departure to build political will and engage Health Ministers on issues of One Health |

| 23 | Global Risk Forum - One Health Summit (2012) | A policy and economic forum to advocate for One Health – One Planet – One Future j. |

| 24 | Zoobiquity publication and Conferences (2012) | Published a book on the connection between human and animal health and, later, in reference to many interdisciplinary issues on humans and animals, followed by conferences held globally k. |

| 25 | 2nd IOHC in collaboration with WHO/FAO/OIE (2013) | Meeting was held in Bangkok, Thailand g. |

| 26 | International Conference on One Health (Africa) | Funded by USAID, OHCEA organized three meetings in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1st) and Kampala in Uganda (2nd and 3rd) from 2013 to 2019. |

| 27 | International One Health Day | Set up in 2016 and held every November 3rd l. |

| 28 | 3rd IOHC (2015) | Meeting was held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. |

| 29 | 4th IOHC (2016) | Meeting was held in Melbourne, Australia |

| 30 | 5th IOHC (2018) | Meeting was held in Saskatoon, Canada |

| 31 | 6th World OHC (2020) | Meeting will be held in Edinburgh, UK m. |

Note that the list is not exclusive as many One Health-related events are happening that may not have been formally captured.

Bresalier et al., 2015.

CDC, 2016b.

29 September 2004 Symposium. www.oneworldonehealth.org.

AVMA, 2018.

Gibbs, 2014.

FAO/OIE/WHO/UNSIC/UNICEF/WB, 2008.

Killewo, 2019.

European Union, 2011.

Mackenzie & Jeggo, 2011.

GRF, 2020.

Natterson-Horowitz & Bowers, 2012.

OHC, 2020.

Osterhaus et al., 2020; https://icophai.org/about-icophai.

In 2006, the American Veterinary Medical Association establish a One Health Initiative Task Force [1,14], and in 2007, the American Medical Association passed a One Health resolution to promote partnering between veterinary and human medical organizations. The International Ministerial Conference on Avian and Pandemic Influenza (IMCAPI) of 2007 and 2008 advocated that the One Health concept should be used to strengthen pandemic preparedness and human security. Furthermore, in 2008, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and the World Health Organization (WHO) together with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the United Nations System Influenza Coordination (UNSIC), and the World Bank developed a framework titled: ‘Contributing to one world, one health-a strategic framework for reducing risks of infectious diseases at the animal-human-ecosystems interface’ [14,16]. This framework led to the formation of six workgroups: 1) cataloguing and developing One Health training curricula; 2) establishing a global network; 3) developing a country-level need assessment; 4) building capacity at country-level; 5) developing a business case to promote donor support; and 6) gathering evidence for proof of concept through literature reviews and prospective studies [14].

Other developments in One Health have been documented (Table 1, [[17], [18], [19]]), and in 2016, the One Health Commission initiated the idea of a One Health Day together with the One Health Platform and the One Health Initiative Team, and a consensus of 3 November every year was reached (Table 1). To date, other perspectives in holistic approach to health systems have been proposed for harmonization with One Health including at least the:

-

1)

EcoHealth, an approach that leans towards constructivist-leaning and not only positivist-leaning assumptions which currently dominate One Health. EcoHealth approach emphasizes the need to protect all living creatures (One Health + whole ecosystem sustainability and socioeconomics), implying that parasites, unicellular organisms, and possibly viruses have a value and should be protected equally [20,21];

-

2)

Planetary health, an approach that focuses on the achievement of the highest attainable standard of health, well-being, and equity worldwide through judicious attention to the human systems—political, economic, and social—that shape the future of humanity and the Earth's natural systems that define the safe environmental limits within which humanity can flourish [15,20,22].

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is likely to profoundly influence the broader adoption of One Health concepts. A rapid analysis of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic suggests that numerous One Health-related concepts and policies are being promoted. First, the ecological perspective on the virus originally established a conundrum among the human-bat-pangolin and live bird market in Wuhan, China [[23], [24], [25], [26]]. Secondly, the approach to manage COVID-19 pandemic was primarily discipline-centric (public health) and disaggregated by geographies (China, Iran, Italy, etc.), a situation where a country's infection is basically thought to be handled as the country's problem primarily [27]. For instance, the advent of COVID-19 pandemic was seen as a health problem limited to the People's Republic of China, although public health policy makers globally were studying the China's situation to learn lessons. Undoubtedly, the response to COVID-19 pandemic should be inter-disciplinary, trans-disciplinary and multi-sectoral. To address unprecedented challenges like COVID-19 and future public health events and emergencies, such One Health approach is needed. In the current work, we explore the One Health landscape across Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries using multi-method approach and report our findings. This study is vital since a One Health centre in Africa was launched in 2020 to facilitate networking, knowledge transfer, critical One Health thinking and sustainable applied research in the Sub-Saharan African region. In order to engage stakeholders and conceptualize the research for development agenda, this inventory study was conducted.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Definition of the study area

In this study, SSA geographically refers to an area in the African continent, south of the Sahara comprising of 46 member States of the African Union (Supplementary Fig. 1, [28]). Using the United Nations' definition of SSA (https://unstats.un.org/unsd/mi/africa.htm), and a review of all One Health initiatives and implementations identified in SSA to date, two maps were created defining the geographical areas of each sub-region (West, East, Southern and Central Africa) and the numbers of initiatives identified per sub-region (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). Maps were validated through additional desk review and consultative engagement with key One Health stakeholders with knowledge of the field. Initiatives were clustered by types, focus area (organization, implementation, coordination, capacity development, research, tool and multipurpose), duration (in years), funding source (national, external, donor partner, multiple), spheres of operation (sub-national, national, regional or global), fields of focus (public health, animal health, environmental health, food safety, wildlife, conservation, AMR, land use and policy etc.) and management structure (national, institutional, global, executive or trusteeship) (http://bit.ly/ohafrica).

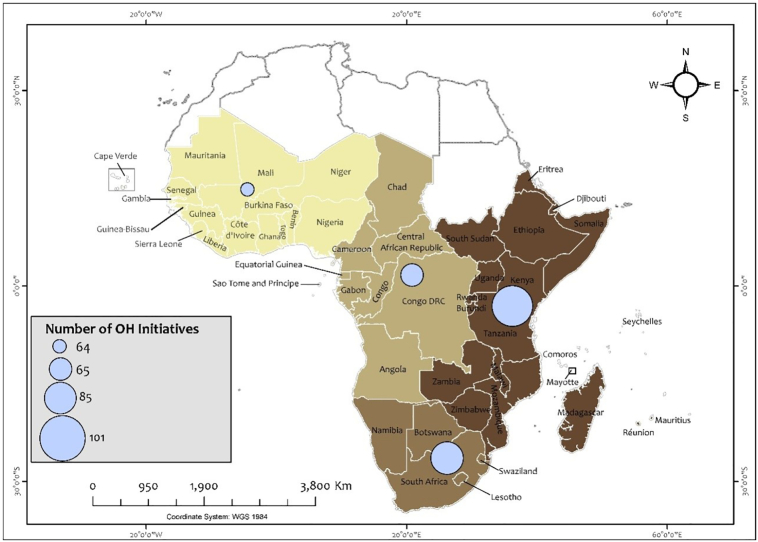

Fig. 1.

Map of Sub-Saharan Africa showing numbers of identified One Health initiatives per sub-region.

One health initiatives across SSA (n = 145) were grouped into coordination, organization, implementation, capacity building, research, tools/applications and multipurpose initiatives. These are national, regional, continental or global in spheres. Many of the initiatives cut across more than one sub-region and the identified initiatives included 101 from East Africa, 85 from Southern Africa, 65 from Central Africa and 64 from West Africa. Coordination and duplication of platforms appeared to be a major challenge among the different initiatives.

2.2. Desk review of literature and expert opinion survey

Available peer-reviewed and grey literatures on One Health in SSA were reviewed. Specifically, all available information on One Health-related to SSA was searched for in two global peer databases (Google Scholar and PubMed) using the relevant search terms related to or closely aligned with One Health (Supplementary Table 2). Also, the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats to One Health (SWOT) were extracted from various reports. These details were used to validate opinions gathered through questionnaire survey and stakeholders' interviews, and used to map all identified One Health initiatives per sub-region.

2.3. Development of a questionnaire and an online survey

A questionnaire was developed and validated by three experts to capture essential data and key inputs on One Health activities and initiatives, influence, interest, impacts and view that motivate One Health in Africa (Table 2, Supplementary Table 3). It was pretested among 7 professionals from the field of public and animal health. Using the developed questionnaire, a total of 57 participants/experts were interviewed through snowball sampling method until no new theme/issue was mentioned. Responses were obtained from individuals and groups of professionals from various African countries and fields such as: public health, animal health, environment health, wildlife experts, etc. Selected experts may/may not reside in Africa but have worked in the field of One Health in Africa.

Table 2.

Details of the questionnaire tool to evaluate One Health Initiatives in Africa.

| Question | Variable | Ranking/ Response | Range or comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) |

|

High (5) Moderate (3) Low (1) |

Definitions of OH interest, influence and impact, and institutions were included in the accompanied email or explanation of the questionnaire. |

|

High (5) Moderate (3) Low (1) |

||

|

High (5) Moderate (3) Low (1) |

||

| 2) |

|

Narrative (maximum 50 words) | |

|

Narrative (maximum 200 words) | ||

| 3) | List the ministries/institutions involved in OH activities & One Health Policy and implementation by institutional category and area of interest that you know. | Answers are provided in a segmented matrix box | |

| 4) |

|

Cardinal number | |

| 5) |

|

Lowest (1) Highest (10) |

Range |

| 6) |

|

Lowest (1) Highest (10) |

Range |

The questionnaire had structured questions with a Likert-scale scoring (scale of 1–5) for One Health Interest, One Health Influence (impact) and One Health Policy Power, the likely impact of organizations on One Health (low-moderate-high), identified One Health stakeholders, and the total numbers of stakeholders influenced by each organization. It also consisted of semi-structured questions including 1) perceived weakest link to successful One Health implementation, and 2) area of best investment in One Health. The questionnaire was available online (https://www.surveymonkey.com/r/M66QTTF) during the survey, or in paper copies where online data cannot be accessed (Supplementary Table 3).

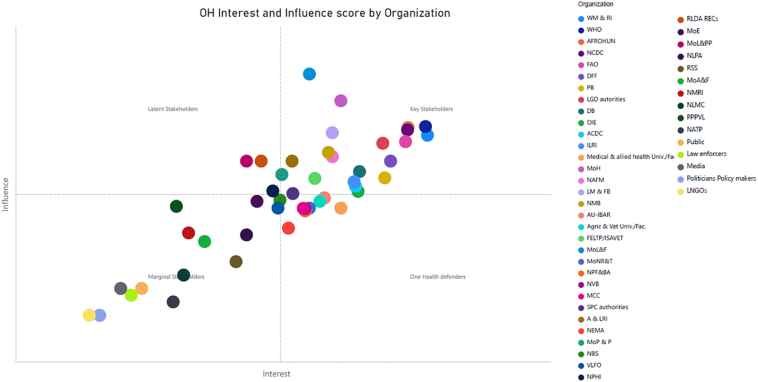

One Health Interest is defined as the commitment of an organization/person in ensuring that systematic and continued collaborative, multi-sectoral, and transdisciplinary approach is utilized between multiple disciplines/sectors to deliver One Health activities at all levels. One Health Influence/impact is the individual's organization spheres of power to significantly impact on One Health-related decisions implemented locally or nationally. One Health Policy Power relates to organizational ability to influence investments, laws, rules and regulations that ultimately shapes and governs the way people and organizations act and interact between each other and with the government to “address complex challenges that threaten human and animal health, food security, poverty and the environments” [[29], [30], [31]]. These criteria were measured through assessment of sphere of power to impact and ability to influence, and formed the basis for classifying stakeholders into the influence-interest quadrants. The ‘key stakeholders’ have both a genuine interest in One Health and can significantly influence the One Health policy framework, and members of this group should be engaged regularly. One Health defenders and latent stakeholders have strong interests in One Health but limited policy influence, or have limited interests in One Health but strong policy influence, and these two groups should be kept informed of the process regularly and, when possible, actively engaged. Stakeholders with limited interest in One Health and limited or minor policy influence are positioned in the bottom left quadrant as marginal stakeholders. They are not anticipated to contribute much to One Health policy development, but their activities should be monitored because they might become important player in One Health policy discussion.

2.4. Data analysis and statistics

Using the framework previously engaged for evaluation of One Health policy stakeholders in Uganda and Kenya [32,33], data from the current study was analyzed. Briefly, all data were entered into, managed and processed in Microsoft Excel version 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). We generated a list of potential One Health Policy Stakeholders and validated the list with One Health experts (play a major role in livestock development; public health; the environment and social development (e.g. poverty reduction)). The identified stakeholders were grouped according to institutional category and areas of interest in order to appreciate stakeholders' perspectives on One Health. Thereafter, based on the interview self-rated scores, the One Health interest, influence and policy power scores were obtained and filtered for inclusion in the analysis and graphical representation of the One Health influence – interest matrix to develop a One Health quadrant, using a 0 to 10 ordinal scale for both dimensions. Descriptive statistics were performed to measure central tendency or variability of the data.

Mean, median, mode and standard deviations were generated for all values using online statistical tool, OpenEpi (https://www.openepi.com/Mean/CIMean.htm). Pairwise correlation of interest, influence and policy power was conducted using the Stata version 9 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). Using the One Health Interest and Influence scores, the One Health Quadrant map was produced to categorize all identified stakeholders into key, latent and marginal stakeholders and One Health defenders. For spatial mapping of One Health initiative in SSA, verified data were submitted to the Geographic Information System (GIS) laboratory, Institute of Resource Assessment (IRA), University of Dar es Salaam.

3. Results

Fifty-seven (57) (including 19 online and 38 paper-based) responses were obtained detailing 145 One Health initiatives1 identified across SSA and these were broadly classified (Supplementary Table 1: http://bit.ly/ohafrica). East Africa has significantly more One Health initiatives/activities (n = 101) compared with other sub-regions: Southern Africa (n = 85), Central Africa (n = 65) and West Africa (n = 64) (Fig. 1). These initiatives were national, regional, continental or global and many of the initiatives cut across more than one sub-regions.

Fifty-five (55) organizations or professional groupings were identified with relevant One Health agenda including those with high, moderate or low impacts on One Health (Table 3). Additionally, the stakeholders and professionals grouped into major One Health quadrants (key stakeholders, latent stakeholders, marginal stakeholders and defenders of One Health initiatives; Fig. 2). Among the key stakeholders are the global/continental public and animal health authorities (like the WHO, FAO, ILRI, AFROHUN, ACDC), programmes (FELTP/ISAVET), national ministries responsible for public and animal health and the local government authorities (Fig. 2). The medical and veterinary regulatory boards, state, county and provincial authorities, and other ministries were identified as latent stakeholders. Marginal stakeholders include the policy makers, the law enforcers, public and private human and veterinary laboratories, and the local non-governmental organization among others (Fig. 2). The livestock farmers, poultry farmers and breeders, national emergency management authorities and the medicine control councils are among the One Health defenders. Using pairwise correlation of interest, influence and power-policy, only the interest and influence scores have good correlation (correlation score = 0.71, p < 0.0001) but policy-power was poorly correlated with interest (correlation score = 0.17, p = 0.27) and influence (correlation score = 0.18, p = 0.25).

Table 3.

List of identified organizations and groupings, likely impact, Mean interest, Mean Influence and Policy power scores of One Health Initiatives and Policies.

| Serial Number | Organizations & groupings | Likely impact on One Health initiatives (Low - Moderate - High) | Mean influence score (0−10) | Standard Deviation | Mean interest score (0–10) | Standard Deviation | One Health Policy Power Score (0–10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National Livestock Marketing Councils | Moderate | 6.3 | 1.7 | 6.6 | 2.5 | 6.4 |

| 2 | National Livestock Producers Associations | Moderate | 6.9 | 1.1 | 7.2 | 3.1 | 6.7 |

| 3 | National Associations of Traders and Processors | Moderate | 6.3 | 2.2 | 5.9 | 2.3 | 6.5 |

| 4 | National Research Support Systems like NRF, ETF, COSTECH, ARC, others | Moderate | 7.1 | 2.4 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 7.1 |

| 5 | Veterinary, environmental and other field officers working in clinics, holding grounds, livestock markets and quarantine stations | High | 7.5 | 1.8 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 6.9 |

| 6 | Medical health care staff (clinics, hospitals) | High | 8.1 | 1.9 | 7.7 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 7 | General public | Moderate | 6.2 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 6.0 |

| 8 | Ministry responsible for Agriculture and Forestry | High | 6.8 | 2.0 | 6.8 | 1.7 | 6.7 |

| 9 | Ministry responsible for Livestock and Fisheries | High | 9.3 | 1.7 | 7.8 | 1.7 | 8.0 |

| 10 | Ministry responsible for Natural Resources and Tourism | High | 7.3 | 2.1 | 7.8 | 1.8 | 6.9 |

| 11 | Ministry responsible for Environment | High | 7.4 | 1.7 | 7.3 | 1.8 | 7.2 |

| 12 | National Environment Management Authority | High | 7.0 | 1.9 | 7.6 | 2.1 | 7.2 |

| 13 | Ministry responsible for Lands and Physical Planning | Moderate | 8.0 | 2.2 | 7.0 | 2.0 | 7.0 |

| 14 | Ministry responsible for Public Health | High | 8.9 | 2.0 | 8.1 | 1.6 | 7.4 |

| 15 | Agricultural & Veterinary Universities /Faculties/Colleges | Moderate | 7.4 | 1.5 | 7.9 | 1.4 | 6.9 |

| 16 | Medical & allied health Universities/Faculties/Colleges | Moderate | 7.3 | 2.1 | 8.1 | 2.0 | 7.1 |

| 17 | Agency/Directorate responsible for medicine control | High | 7.3 | 1.6 | 7.7 | 1.6 | 7.0 |

| 18 | Development partners, funders & financial institutions (USAID, EU, UKAid, World Bank, others) | High | 8.0 | 1.5 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 7.4 |

| 19 | Public & private financial Institutions | Low | 5.2 | 1.5 | 5.1 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| 20 | National Medical Research Institute | High | 6.9 | 2.7 | 6.6 | 1.9 | 6.9 |

| 21 | National Plant Health Inspectorate Service | Moderate | 7.6 | 2.5 | 7.5 | 2.3 | 6.5 |

| 22 | National Poultry Farmers & Breeders Association | Moderate | 7.3 | 2.5 | 7.8 | 2.5 | 7.1 |

| 23 | National Association of animal Feed Manufacturers | Moderate | 8.1 | 1.6 | 8.0 | 1.1 | 7.1 |

| 24 | African Union-IBAR | Moderate | 7.5 | 2.4 | 7.9 | 1.9 | 7.4 |

| 25 | Regional Livestock Development Agencies/Organization and Regional Economic Communities | High | 8.0 | 1.6 | 7.3 | 1.5 | 6.8 |

| 26 | Africa Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention | Moderate | 7.6 | 2.3 | 8.2 | 1.6 | 7.4 |

| 27 | National Medical Board | High | 8.1 | 1.6 | 8.0 | 1.6 | 7.5 |

| 28 | National Veterinary Board | High | 7.3 | 2.4 | 7.8 | 1.8 | 7.2 |

| 29 | Ministry responsible for Policy and Planning | High | 7.8 | 1.7 | 7.5 | 1.9 | 6.6 |

| 30 | National Bureau of Standards | Moderate | 7.4 | 2.0 | 7.5 | 1.6 | 7.2 |

| 31 | National Agricultural and Livestock Research Institute | High | 8.0 | 1.5 | 7.6 | 1.6 | 7.7 |

| 32 | Dairy Board | High | 7.8 | 1.4 | 8.3 | 1.4 | 7.5 |

| 33 | Livestock Meat & Food Board | High | 8.4 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 1.6 | 7.3 |

| 34 | Pharmacy Board | Moderate | 7.8 | 1.8 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 7.7 |

| 35 | Field Epidemiology & Laboratory Training Program (FELTP)/ In-Service Applied Veterinary Epidemiology | High | 7.7 | 2.0 | 7.9 | 2.1 | 7.3 |

| 36 | State/Province/County Authorities | High | 7.5 | 2.2 | 7.6 | 2.0 | 7.9 |

| 37 | Local Government/District Authorities | Moderate | 8.3 | 1.5 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 7.8 |

| 38 | World Organization for Animal Health | Moderate | 7.5 | 2.0 | 8.3 | 1.2 | 7.5 |

| 39 | International Livestock Research Institute | Moderate | 7.7 | 2.2 | 8.2 | 1.5 | 7.2 |

| 40 | Wildlife Management & Research Institutions and Services | High | 8.4 | 2.1 | 8.9 | 0.9 | 7.8 |

| 41 | Food and Agriculture organization of the UN | Moderate | 8.3 | 1.2 | 8.7 | 1.0 | 7.8 |

| 42 | National Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention | High | 8.5 | 1.3 | 8.7 | 0.9 | 7.8 |

| 43 | Africa One Health University Network | Moderate | 8.5 | 1.4 | 8.7 | 0.8 | 7.9 |

| 44 | World Health Organization | High | 8.5 | 1.5 | 8.9 | 0.7 | 7.9 |

| 45 | Local NGO, CBO and FBOs | Moderate | 5.7 | 1.8 | 5.7 | 1.4 | 6.3 |

| 46 | Public and Private public and veterinary laboratories | High | 8.2 | 1.1 | 8.0 | 1.7 | 6.5 |

| 47 | US CDC | Moderate | 8.5 | 1.3 | 8.7 | 0.9 | 7.8 |

| 48 | Government Boards | Moderate-high | 6.5 | 2.1 | 6.8 | 2.1 | 7.2 |

| 49 | Law enforcers (police, military, customs) | Low-moderate | 6.0 | 2.1 | 6.1 | 1.3 | 5.2 |

| 50 | Input providers (Veterinary, medical, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, biologicals, feed & equipment | High | 7.2 | 1.6 | 6.9 | 1.7 | 5.5 |

| 51 | Meat inspectors | High | 8.4 | 1.6 | 7.9 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| 52 | Media (print, electronic & social) | Moderate | 7.3 | 1.8 | 7.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| 53 | Politicians/Policy makers | High | 7.5 | 2.1 | 9.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| 54 | Environmental health officers & researchers | High | 6.0 | NA | 6.0 | NA | NA |

| 55 | Climate office & experts | High | 6.0 | NA | 8.0 | NA | NA |

| Correlation analysis of One Health Interest, Influence and Power-policy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/no. | Variable | Interest | Influence | Power-Policy |

| 1. | Interest | 1.0000 | ||

| 2. | Influence | 0.7138* | 1.0000 | |

| 3. | Power-Policy | 0.1725 | 0.1809 | 1.0000 |

*Significant at < 0.0001

A total of 57 experts from the following fields responded to the questionnaire: global one health leaders, veterinarians, physicians, animal scientists, public health professionals/epidemiologists, butcher, infectious disease expert, aquaculture expert and animal health technician. Responses were provided through feedbacks online or in hard copies on paper. No physical meeting was engaged in view of the risk of COVID-19 infection.

Fig. 2.

Quadrant analysis of One Health Stakeholders' Interest and influence matrix in One Health initiatives.

National Livestock Marketing Council (LMC), National Livestock Producers Association (LPA), National Associations of Traders and Processors (NATP), Research Support Systems like NRF, COSTECH, ARC, others (RSS), Ministry responsible for Agriculture and Forestry(MoA&F), Ministry responsible for Livestock and Fisheries (MoL&F), Veterinary and livestock field officers working in holding grounds, livestock markets and quarantine station (VLFO), Ministry responsible for Natural Resources and Tourism (MoNR&T), Ministry responsible for Environment (MoE), National Environment Management Authority (NEMA), Ministry responsible for Lands and Physical Planning (MoL&PP), Ministry responsible for Public Health (MoH), Agricultural & veterinary Universities/Faculties/Colleges (Agric & Vet Univ./Fac.), Medical & allied health Universities/Faculties/Colleges,Agency/Directorate responsible for medicine control (MCC), National Medical Research Institute (NMRI), National Plant Health Inspectorate Service (NPHI), National Poultry Farmers & Breeders Association (NPF&BA), National Association of animal Feed Manufacturers (NAFM), African Union-IBAR (AU-IBAR), Regional Livestock Development Agencies/Organization and Regional Economic Communities (RLDA/RECs), Africa Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention(ACDC), National Medical Board (NMB), National Veterinary Board (NVB), Ministry responsible for Policy and Planning (MoP&P), National Bureau of Standards (NBS), Agricultural and Livestock Research Institute (A&LRI), Dairy Board (DB), Livestock Meat & Food Board (LM&FB), Pharmacy Board (PB),Field Epidemiology & Laboratory Training Program (FELTP)/ In-Service Applied Veterinary Epidemiology (ISAVET) Programme (ISAVET), State/Province/County Authorities (SPC Authorities), Local Government/District Authorities (LGD Authorities), World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), Donors, funders & financial institutions like USAID, EU, UKAid, World Bank, others (DFF), International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), Wildlife Management & Research Institutions and Services (WM&RI), Food and Agriculture organization (FAO),National Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (NCDC), One Health Central and Eastern Africa (AFROHUN), World Health Organization (WHO), Local NGO, CBO and FBOs (LNGOs), Public and Private public and veterinary laboratories (PPPVL).

3.1. Selected examples of one health initiatives in Sub-Saharan African

While One Health initiatives are spread across SSA, selected examples of One Health implementations were highlighted below to show specifics of strengths weaknesses, unintentional consequences and how investments in One Health can be redirected:

1. The Coordinating Office for the Control of Trypanosomiasis in Uganda (COCTU) is a One Health initiatives with documentary evidence in Africa. The COCTU has been implementing joint Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), animal trypanosomiasis and Glossina species (tsetse fly) control in Uganda for almost three decades [34]. Despite the milestones and achievements, it continues to face financial challenges for its sustainability. Its name and associated perceptions also challenged its operation in other areas and fields, e.g. vector-borne disease like Rift Valley fever (RVF).

2. Kenya established a multi-sectoral committee to develop preparedness planning and efforts at mitigating the potential introduction and spread of HPAI H5N1. This body also responded to an outbreak of RVF in the Eastern Africa Region during 2006–2007 [35,36]. This coordinated efforts between the Ministry of Health (MoH) and Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries (MALF), joint coordination and communication, built human capacity especially through the Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training program (FELTP) and other sustained collaboration with other US programmes led to the development of a fully functional BSL-3 laboratory at KEMRI and the formation of a national One Health coordinating office, the Zoonotic Disease Unit (ZDU) in 2012 [36,37].

3. On December 12, 2005, the Federal Government anticipatorily inaugurated a Technical Committee of Experts for the prevention and control of HPAI H5N1 outbreak in Nigeria. By February 8, 2006, the first case of HPAI H5N1 in poultry in Africa was reported, the national government rapidly set up a National Inter-Ministerial Steering Committee on Avian Influenza (NISCAI) and the National Technical Committee on Avian Influenza (NTCAI). This Technical Committee coordinated and implemented emergency action plan and strategy proposed for the prevention and control of the outbreak [38,39]. However, these bodies faded away with the elimination of the HPAI H5N1 in Nigeria and did not get institutionalized31. Also, the FELTP programme has since kick-started in October 2008 and is facilitating joint human-animal-environment and laboratory-field joint investigations and interventions [40,41].

4. The rabies intervention in Tanzania has benefitted from multiple partnership, academic programmes and research interventions. The wildlife ecosystems of Serengeti, Selous and few others have benefitted from funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) for a rabies elimination programme in Tanzania covering 23 high-risk districts [42,43]. The research group from the University of Glasgow and GARC had delivered several rabies interventions both in Tanzania's Mainland and the Islands of Zanzibar using One Health approach [[44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51]]. Using innovative One Health approach involving practitioners and students of One Health, FAO had partnered with the government of Tanzania to deliver rabies control in Moshi, Kilimanjaro Region [40,43]. The challenges with project-based deliveries remain the sustainability, national ownership and resource limitations [52].

5. Currently, the Food and Agriculture Organization through the Global Health Security Agenda's Zoonotic Diseases and Animal Health in Africa (GHSA-ZDAH) funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has been supporting many One Health interventions through policy documents, control strategies, protocols, evaluations, national veterinary laboratories strengthening, epidemio-surveillance capacity building, workforce development and AMR. These activities are expected to continue into the foreseeable future. Similarly, the Africa CDC and the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) have launched major continental One Health initiatives.

In terms of observed weakest links, 27 themes were identified ranging from issues of weak collaborations and coordination, inadequate human and material resources, lack of decentralization to subnational levels, limited One Health data, data concealment, inadequate representation of some sectors and misconceptions about One Health among others (Table 4). For areas of best investment in One Health in SSA in order to promote One Health implementations, the following were identified areas: strengthening intersectoral and multidisciplinary collaborations, building national and subnational capacities in One Health, investment in research and software for reporting and interoperability, joint outbreak response, support for decentralization of One Health office at national-subnational levels, support for setting up One Health champions and stakeholders committees at national-subnational levels, financing of One Health interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research, support for the development of MoUs and legal document, establishment of specific undergraduate/postgraduate track of training in One Health, and sensitization on One Health at community levels (Table 4). Importantly, there is a need for a more qualitative evaluation of the identified weakest link for One Health implementation in Africa. This opportunity should be used to avoid pitfalls that have delimited the success of previous One Health efforts (Table 4).

Table 4.

Common themes originating from selected One Health stakeholders on important questions on One Health initiatives.

| S. No. | Observed weakest link in the Sub-Saharan African countries that have prevented or limit the successful implementation of One Health at local, national or regional level | Suggested area of best invest towards improving One Health implementation in the African countries |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Weak collaborations between the various sectors that should implement One Health. Unhealthy rivalry and competition among the various sectors of one health sometimes hamper developments in One Health. One Health integration among the various sectors of One Health is still somewhat weak. Reductionism. | Strengthening collaboration between the various sectors at national and subnational levels (see Supplementary Table 5 for example). This may also have regional ramifications. |

| 2 | Inadequate human, material and financial resources from the government. There is oftentimes Inter-sectoral discrimination in funding and budget provisions among key disciplines hence the lack of funds to finance projects. The government could facilitate a Theory of Change process for different (One) Health problems and engage all sectors and disciplines in developing their roles and contribution in the big puzzle | Capacity building of the staff at central (national) and subnational level – on management, coordination, communication and resource mobilization. Such example include but is not limited to the HEAL curriculum. |

| 3 | Decentralization of One Health activities to subnational level for implementation should be prioritized. | Invest in research and software development for easy reporting and collation of data in the field of One Health. |

| 4 | Low level of One Health awareness among policy makers and the public on burden of zoonoses and benefits of One Health. | Developing strategies and guidelines for zoonoses and relevant One Health issues like antimicrobial resistance, toxins, environmental issues etc. |

| 5 | There are limited data on burden of zoonoses and other One Health challenges to influence policy. Even where data from vital research outputs exist, sharing among the various One Health stakeholders and end users/beneficiaries may be problematic. | Mapping of One Health stakeholders/actors and activities implemented in the country. |

| 6 | Relatively weaker wildlife sector compared to public and animal health. | Joint (inter-ministerial and intersectoral) field activities e.g. outbreak investigations. |

| 7 | Cross-border implementation of One Health initiatives is always challenging in view of different policies, legislations, and uneven finance/sponsorship among countries that share borders. Ineffective cross-border One Health implementation. | Support advocacy on One Health approach and associated activities (including good practices documented so far) to ensure enhanced understanding among policy makers and actors. Promote One Health education among reputable political leaders. |

| 8 | Coordination mechanism at both national and subnational levels is still weak and often non-committal. This is as a result of not having adequate staff fully committed to implementation of One Health activities. | Lobby for adequate number of qualified staff (experts in public health, animal health and environment health/metrological, GIS/data and information management specialist and risk communication expert) at the central coordination office to ensure implementation of the agreed work plan. |

| 9 | Wildlife health is currently not well captured in the principles of One Health. The human medical and veterinary practitioners are sometimes at loggerheads for supremacy of disciplines | Utilize fund for human resource development and capacity building, especially for the professionals left behind in previous One health training so that they will be better positioned to perform optimally in the One Health initiatives. |

| 10 | Poor representation of other fields like the animal scientists, biologist, other relevant biomedical and natural sciences, and social sciences and policy related fields in the One Health teams. Wildlife health and ecohealth are also still very deficient and left behind in One Health initiatives | Equipping the coordination office to facilitate data collection, processing and timely information sharing |

| 11 | The career civil servants often want to take the forefront role in new initiatives like One Health without consideration for professional fits, hence the lack of competence and administrative lapses to lead the One Health team | The payment of ad-hoc staff to support substantive staff in ramping up capacity for One Health. |

| 12 | Foreign partnership on One Health joint activities is dwindling and insufficient external funding is available. | Training on One Health through various means and innovations like online platforms, remotely accessed training, localised training initiatives, and nationally institutionalised training on resource mobilization and establishing global collaborations. |

| 13 | Inferiority – superiority complexes among the various professionals and institutions. In some high-profile organizations and institutions, some persons see their role as more important than that of others. This mindset and insular attitude generate resistance to collaborate and refusal to give due credit to other productive groups/organizations with counterproductive consequences for noble One Health concept/approach | Assembling a team comprising various professional bodies and stakeholders like veterinarians, animal health technologists, epidemiologists, public health specialists, print and electronic media practitioners etc. to propagate the concept and importance of One Health in the representative local government areas in all the regions of the country. During this exercise data will be obtained simultaneously to ascertain the level of awareness of One Health concept in the country for future use. |

| 14 | Concealment and denial of information and data among the various One Health stakeholders, hence the obvious inter-sectoral communication gap. Information and data sharing among sectors may also be met with some level of resistance or officially barred. | Form a team of different professionals across disciplines to start a large One Health national team, with subnational formats replicated at the secondary and tertiary levels of administration. The team will be expected to develop proposals and jointly implement different activities together including research, awareness creation, training and field implementation for different stakeholders. |

| 15 | Misconceptions of One Health approach. Prevailing uni-disciplinary research and weak understanding of the essence of One Health. For example, public health clinicians still think largely of clinical approach, the veterinarians think of population medicine approach and the environmentalists and ecologists think of the environment and wildlife/habitat/ecosystem health primarily. | Carry out gap assessments to determine the core areas with obstacle for the development of One health initiatives in the country. This will be followed by the presentation of the positive impact of one health to the stakeholders in the country. The outcome will be presented to higher officials, policy makers and influencers for purpose of advocacy. |

| 16 | Administrative challenges and inter-sectoral bureaucratic bottlenecks may sometimes make One Health impracticable. For example, some line ministries cannot pull funds together inter-ministerially to jointly implement activities | To finance researches that are related to public health, food-borne diseases, meat contamination, food preservation, food security, livestock genetic improvements, and evidence-based research. |

| 17 | Undefined or not clearly defined roles, responsibilities and functions of the various stakeholders hence encroachments and duplication of functions and activities. Lack of policy framework and system that will enable the effective coordination of relevant stakeholder institutions. | To sponsor projects related to AMR and resistance gene transfer among human, animal and their environment. |

| 18 | There is no unified database on One Health as the different sectors prefer their independence. | Construction of a good slaughterhouse, and proper remuneration of meat inspectors to showcase proof of concept. |

| 19 | Poor advocacy to policy makers hence lack of One Health approaches at subnational levels. | Injection of fund into areas and projects starved of funds. |

| 20 | Poor knowledge of relevant One Health initiatives among relevant stakeholders (the general public) as well as inadequate/archaic knowledge of concept roles, importance and contributions of One Health. | To attend workshops and relevant seminars that clearly put into perspectives enlightenment and acquisition of knowledge on One Health programs, initiatives and activities, as well as the establishment of Community of Practice (CoP) |

| 21 | Prioritization of other emergency issues e.g. the ongoing COVID-19, Ebola, natural disasters etc. | Money will be used to prepare the MOU or legislation for partnership which clearly define the roles of every professional partaking in One Health activities. Such investment should focus on preventive rather than responsive outbreak response. |

| 22 | The non-existent of relevant One Health policies and robust understanding of the topic by legislators and regulators. | Establishment of One Health administrative offices at subnational level for proper organization |

| 23 | Poor monitoring and evaluation of One Health activities and initiatives. | Boosting capacities of different constituents of One Health and setting up necessary M & E to closely monitor progress. |

| 24 | Endemic poverty prevents making informed One Health decisions | Investment into One Health Education and Curricula at University/College levels. Promote One Health approaches among undergraduate medical and veterinary students, in diploma colleges and or fund MSc projects utilizing One Health approaches. Such is also important at primary education level (e.g. teaching the concepts of good hygienic practices, how health of animals and humans and environment are interconnected) including the supportive training to teachers. |

| 25 | Access to direct local funding to support research/implementation of One Health approaches are inconsistent. Most of the present One Health activities are donor-driven. | Establish undergraduate and post-graduate training and research in the One Health approach with practical and applicable field attachments for all cadres of practitioners using modern ICT techniques. This should be tied to local, subnational and national resource mobilizations. |

| 26 | The lack of formal education of stakeholders. For instance, the farmers, herders, butchers, smallholder farmers, roadside drug shop owners, food vendors and other artisans may be important stakeholders but are not formally educated in hygiene, biosafety and biosecurity, one health, antimicrobial resistance and such one health issues, hence they will continually serve to limit milestones and achievements in One Health. | To support the implementation of a policy framework that mandates One Health collaboration and integration at all relevant stakeholder institutions. Integration of One Health into relevant stakeholder institutions through the establishment of One Health Desks in every institution that will cater to issues or projects that require multi-disciplinary and transdisciplinary actions/contributions. |

| 27 | To strengthen coordination and empower subnational One Health actions (implementation) | |

| 28 | Conduct community sensitization using established front like the political and religious leaders. | |

| 29 | Conduct Community sensitization at one of the hot spots and interfaces for diseases e.g. point of entry (POE) | |

| 30 | Strengthen preparedness planning and improve the ability to respond to zoonotic diseases, AMR and other public health events outbreak at all levels. | |

| 31 | Strengthens animal and public health reporting systems and their interoperability | |

| 32 | Initiate the collaboration of different professionals to research into climate-smart agriculture for increased food production, ecofriendly utilities and vibrant blue economy due to the fact that humans now encroach into the natural forests and their rich and diverse fauna which expose humans and domestic animals to new pathogens | |

| 33 | Initiate transdisciplinary research where veterinarian, public health, social science, laboratory and environment health experts and local community opinion leaders could work together on shared objectives | |

| 34 | To support centralization of tools for reporting of zoonotic infectious disease and related One health issues once it is detected and ensuring that this platform is available to all key parastatals and stakeholders involved in One health | |

| 35 | Promotion of biosecurity among veterinarians, rangers, health workers and others | |

| 36 | Start a project that would incorporate transdisciplinary approaches with contributions from a wide range of professionals. Such project would target the integration of One Health approach and target the vulnerable (unemployed youth and women) in the society. These individuals make the larger part of the population. The projects objectives will include: Improvement of livelihoods of the target populations through the creation of awareness on one health approach. Empowerment of the vulnerable by creating sustainability Use the target subset of the population to disseminate the acquired information and benefit as proof of concept to the rest of the community. |

|

| 37 | Establish a national one health task force or network multiple professionals | |

| 38 | I would then recruit community leaders and members and train them on this approach and use them as ambassadors and One Health champions to preach the one health approach at the community level. | |

| 39 | Establishment of or strengthening of One Health administrative offices at subnational levels for proper organization of national-subnational integration and future funding | |

| 40 | Such money will be invested to promote wildlife health involvement in One Health | |

| 41 | The money will be used to augment budget deficit wherever there is genuine interest in One Health administration | |

| 42 | To address poorly coordinated One Health activities by running an office | |

| 43 | To sponsor bills for legislations and policies on One Health initiatives |

Responses were obtained from individuals and groups of professionals from various fields and disciplines including public health, animal health, environmental health, fisheries, and other stakeholders, cutting across multiple African countries and from experts who have worked in the field of One Health in Africa but reside within or outside the continent. Snowballing method was utilized to gather this information until the saturation point was reached when no new theme was mentioned.

3.2. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis

One Health has made a lot of inroads in SSA. It has also been impacted by certain enablers and hindrances. While the summary is available below, details are tabulated in Supplementary Table 4. The summarized gaps observed in One Health implementation in Africa include but are not limited to the following:

-

1.

Information sharing, communication and collaborations among the various sectors of One Health is very poor among disciplines and sectors. No stakeholder should be left in the fringe of participation. Challenges must be evaluated comprehensively and all necessary stakeholders must be brought in as active players in interdisciplinary engagement for problem assessment, stakeholder mapping and in the design and implementation of One Health solutions.

-

2.

Proliferation of data and multiple platforms for information capturing that are mostly multichotomous. This largely emanated from the data capture systems created differently for each sector without a consideration for other field. Quality data must be accessible and verifiable from a centralized source and reporting formats.

-

3.

Preparedness and response to disease outbreaks, emergency interventions, disaster interventions and recoveries, policy development, community engagement and M&E for One Health initiatives are dissimilar across African countries or are inexistent in some countries, especially those without external assistance to develop such intervention. Where these are available, they are often not tested or evaluated through drills, simulations and after action reviews.

-

4.

Lack of institutional development and adequate human resource as well as lack of One Health capacity building in the different sectors. Usually, in most Sub-African countries, public health capacities are ahead of the animal health and environment health capacities. These dissimilarities have often served as barriers to harmonized interventions between sectors.

-

5.

Duplication of roles and efforts among sectors serve as hindrance to effective implementation of One Health initiatives and effective participation of government ministries. Having a centralized and harmonized multi-sectoral platform will promote interdisciplinary facilitation of ‘one healthiness’ in addressing AMR, surveillance and other issues in SSA.

-

6.

Many ministries and government departments and parastatals are understaffed. Majority of the personnel though may also be qualified in their professional disciplines, are not always competent or skilled enough in the utilization of One Health approach, and where they are competent, they may lack the wherewithal to perform/implement One Health effectively.

-

7.

The greater majority of the One Health stakeholders continue to depend on external funding and sponsorships. Although the government may dedicate some budget to One Health issues, there is paucity of national sponsorship and partnership in the field of One Health. Also, over-reliance on technical assistance and subject matter experts/specialists from international organizations and foreign countries can become a limitation and create dependency.

-

8.

Absence of or deficiency of regulations, policy documents, legal instruments and memorandum of understanding on the involvement of vertical and horizontal engagements is a weakness.

-

9.

Quality laboratory services, which are essential components of healthcare system remain weak due to several factors. Most national laboratories do not meet the accreditation standards under the quality management system, capacities are limited, skills are not regularly updated and laboratory diagnostic facilities are limited or unavailable to deliver efficient and prompt diagnosis, particularly, during emergencies and in outbreak situations. This is particularly so, in the subnational systems of low to lower-middle income and conflict-impacted countries in SSA [45,46]. Furthermore, regional and sub-regional-level reference laboratories that should support national efforts are often not available.

-

10.

Cross-border One Health initiatives and efforts have been launched in many border areas across Africa, and are largely championed by continental or regional economic commissions (RECs) like the AU, AU-IBAR, ACDC, ECOWAS, WAEMU, MRU, ECCAS, CEMAC, COMESA, IGAD, AMU, EAC, SADC, SACU, CILSS etc., the follow-up actions and implementation of outcomes arising from the reforms have often suffered neglect because of lack of interests, differences in country-level policies and lack of political will. These sub-regional and regional-led efforts can be utilized to promote One Health and both national and subnational system can take advantage of these bodies to implement national-level One Health initiatives.

-

11.

Since the ministries implement their activities based on dedicated and gazetted budget lines, and because One Health is a relatively new concept compared to traditional public, animal and environment health implementation frameworks, as well as the policy and socio-economic environments, One Health platforms often have none to insufficient allocations to actualize approved One Health activities. Currently, the donor-funded One Health budget is unsustainable because with the donors, future funding environment may be inconsistent and uncertain. Necessary legal and policy instruments for prioritizing national funding for planning and implementation of One Health initiatives must be created.

-

12.

There are no systemic disease surveillance system; but if present, the communication and information exchange among the systems and the reporting channels is less than desirable.

-

13.

While selected African countries have functional One Health platforms, sometimes, the lack of subnational platforms hinders One Health coordination. Moreso, most subnational governmental systems in Africa have limited competencies and subject matter expertise in the workforce to implement One Health approach and integrate multi-sectoral work. While formulation and coordination as well as legal backing often take place at the national level, field implementation resides with the subnational system. Therefore, the subnational system should be carried along in the national One Health platform.

-

14.

The set-up costs, as well as the cost of acquisition, implementation and maintenance of ICT infrastructure and modern technologies to support One Health are usually high and untenable in most SSA. Lamentably, the back-up infrastructure like electricity is inconsistent in several countries to support technologies.

-

15.

Some countries face economic and socio-political instabilities/insecurities etc. In such countries, prioritizing One Health initiative is hardly given any consideration because of limited access to service delivery and lack of resources even though those populations may be more vulnerable to disease events.

-

16.

Innovative approach at co-delivering One Health in the veterinary, medical, public health, socio-economics, policy and anthropology schools appears lacking. Teaching workforce capacities and focused curriculum need to improve using partner like the Africa One Health University Network (AFROHUN) formerly One Health Central and Eastern Africa (OHCEA).

-

17.

Currently, the private practitioners outside of the main government systems contribute minimally or do not contribute to and participate in One Health initiatives. Stimulus to facilitate inclusion of private stakeholders should be implemented by national One Health champions.

-

18.

Presently, policymakers at the national and subnational levels of governments have a somewhat poor understanding of and are not familiar with concepts of One Health. Enlightenment on One Health should be done for these cadres for purposes of advocacy and adequate information. This should address the issue of low prioritization and poor funding of One Health initiatives.

-

19.

To date, most One Health initiatives and networks in SSA have kick-started as a fall-out of project or sporadic sequel of single of few One Health activities. In these situations, the governance and management structure may not have been thought through and the existing government policies, legal documents, SOPs and strategies may not have been thoroughly considered before the implementation of national One Health platforms. Where this is the case, a review of the foundational basis for the national One Health platforms is necessary to fix outstanding issues in order to have broad based support and gain political goodwill of all One Health stakeholders.

-

20.

Operational research (OR) in One Health is lacking largely. There is a need to implement OR that considers trans-disciplinary/interdisciplinary engagements and activities. Such initiative must be based on real-life problem and not abstract. Additionally, the inclusion of outcome-based engagement that utilizes monitoring and evaluation as basis for One Health programme design is warranted.

-

21.

Inadequate inclusion of the ecosystem health dimension in the One Health platform left gaps in effectively addressing some underlying drivers of disease emergence such as deforestation, change in agricultural practices, etc.)

Comprehensive reports on the summaries above are available in peer-reviewed repositories and national documents [4,34,35,[52], [53], [54], [55], [56]].

4. Discussion

Based on this study, One Health has gained significant milestones since the time of Hippocrates to date and transited from merely the issues of zoonoses to broader inclusion of many sectors. In Africa, East Africa have thrived with One Health initiatives relatively more than the other sub-regions in SSA (Fig. 1), but whether this has reflected more on the sub-region compared with others is doubtful, because the majority of the initiatives does not have the monitoring and evaluation implemented alongside the One Health initiatives in Africa.

To date, many of the One Health Networks, both globally and particularly in Africa, are largely academic (78%) and approximately a third of them have narrow perspectives (human-animal health issues only) [11,30,31,38]. It is important to see One Health issues beyond the prism of human-animal health and, instead, to include all sectors and stakeholders in the planning and implementation of One Health approach, the focus of ecohealth. This reductionist view and imbalance in stakeholders' representation often translate into narrow perspectives and outcomes in One Health, with consequent lack of buying in from other stakeholders during implementation. In SSA, the One Health Networks collaborate less; it does not usually involve the clearly defined theory of change and to date, the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks for One Health issues are non-existent (Table 4) [11]. This gross lack of a clear framework for M&E will likely result in lack of direction and the conduct of many One Health activities without key outputs and outcomes in mind. Despite the current efforts (Supplementary Table 1, 4a & b), the One Health concept has mileages to gain in the areas of joint surveillance and monitoring, disease controls, emergency interventions, disaster interventions and recoveries among others [55,57]. Because many of the international agencies and donor partners, as well as national ministries responsible for public, animal and environmental health have large influences and interests in One Health (Table 3, Fig. 2), they need to work closely together to jointly implement national and subnational One Health efforts. The One Health quadrant was particularly informative to support clustering of sectoral working relationships and setting up of MoUs. Similarly, balance in the impact/influence, interest and policy power and an intermix of these stakeholders in effective implementation of One Health initiatives are important.

A number of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats have been identified. Given that One Health concept is suitable and adaptable to SSA for cheaper cross-sectoral, cross-disciplinary engagements [39,42], to date, funding for most (> 90%) of the One Health initiatives across Africa has originated largely from outside the continent with some partial co-funding from national governments and this position will need to change. In addition, many of the networks and institutions involved in One Health in Africa have their headquarters based in Europe or America with the exception of ILRI and SACIDS [11,35,56,58]. This is because the majority of the One Health initiatives and the associated funding for the implementation of the projects come from these continents. With rapid development of more One Health initiatives, some relatively new and upcoming institutions are taking roots in Africa, although without a sustained funding system as outlined in previous evaluations [[54], [55], [56]] (Supplementary Table 1).

To date, inter-ministerial and interdisciplinary protection of mandates and inadvertent but underlying turf wars remain a challenge for the effective take-off of One Health in Africa (Table 3; Supplementary Table 4). Certain stakeholders are also often left behind in the implementation of One Health, however, the evaluation of One Health impact, interest and policy power (Table 2, Fig. 2) have indicated that all actors and stakeholders are needed in the successful implementation of One Health at all levels. Ministries and government departments will need to consider issues of One Health as beyond territorial protection and open-up to other disciplines/sectors to deliver cost-effective solutions. Zoonotic diseases and threats of potential epidemics can facilitate national and regional emergence of One Health initiatives [34], and professionals must learn to utilize such One Health opportunities to deliver One Health. Clear national-subnational roadmap should be developed in the delivery of One Health concept taking cognizance of previous pitfalls for sustenance and set-back associated with initiatives implemented to date [34] (Table 3, Supplementary Table 4).

National One Health platforms will continually suffer setbacks, deliver externally-programmed outcomes and risk unsustainability if the dependence on donor-funding continues [11,34]. The necessary policies and legal instruments should be put in place per country, regionally and continentally in order to facilitate the push towards full implementation of One Health in SSA. Connolly et al. [57], had earlier discussed the One Health in the context of emerging urbanization and global disease threats, and emphasized that One Health implementation is possible in Africa and elsewhere if strong mutuality of commitment to One Health agenda at the supranational (global and continental) and micro (national and subnational, including individual) levels is assured. It should be understood that the poverty intermix with peri-urban/rural development remain an important interface for intense human-animal-environment interactions that may escalate diseases. These locations typically have poor service deliveries, poor sanitation, high human and animal population densities, poor living standards and huge social inequalities [57]. National and subnational authorities should concentrate on improving local capacities and implementing infrastructural developments that align with One Health objectives and facilitate its implementation at local levels. Local and national champions may be used to deliver One Health concept with blended approach [11,34].

Human capacity development at local level and integrating the concepts of One Health at all levels (informal and formal trainings) – right from primary up to tertiary levels – as well as in periods of in-service trainings will assist in ingraining the concept of One Health. Such example of sub-tertiary One Health concept is already in parts of North America where curricula are in place for facilitating One Health approach at primary and secondary levels of education, and this is suitable for Africa.

Africa has been considered as hotspot for various emerging infectious diseases and future global pandemic threats particularly because of its forested tropical regions, land-use changes, socio-economic changes and wildlife biodiversity [[58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63]]. One Health will deliver the most efficient and cost effective policies for disease prevention; policy interventions; environmental friendly consideration and socio-politically-adapted management through ecohealth. One Health remains a viable solution for SSA because:

-

1)

Africa has burden of infectious and zoonotic diseases at the interfaces coupled with growing food insecurity, threatened livelihoods and endemic poverty; these portend threats to national and continental economic growth;

-

2)

The growing convergence of technology and strategy in surveillance, prevention and management for diseases can be leveraged using One Health approach; and,

-

3)

The best intervention remains those that are regional-led and all-inclusive [62]. This is the strongest detection, prevention and defense mechanism that can be built against emerging threats posed by those drivers of bio-threats identified above [63].

The future of One Health institutionalization will be dependent upon removing barriers associated with reductionist viewpoints as outlined in our results and various reports. Policy makers, politicians, communication experts, socio-economists, social scientists and other fields cannot be considered as necessary only during the implementation and post-mortem analysis of One Health issues. They should be included right through the whole of One Health approach, right from the planning to execution.

5. Conclusion