Abstract

Transplantation is now performed globally as a routine procedure. However, the increased demand for donor organs and consequent expansion of donor criteria has created an imperative to maximize the quality of these gains. The goal is to balance preservation of allograft function against patient quality-of-life, despite exposure to long-term immunosuppression. Elimination of immunosuppressive therapy to avoid drug toxicity, with concurrent acceptance of the allograft – so-called operational tolerance – has proven elusive. The lack of recent advances in immunomodulatory drug development, together with advances in immunotherapy in oncology, has prompted interest in cell-based therapies to control the alloimmune response. Extensive experimental work in animals has characterized regulatory immune cell populations that can induce and maintain tolerance, demonstrating that their adoptive transfer can promote donor-specific tolerance. An extension of this large body of work has resulted in protocols for manufacture, as well as early-phase safety and feasibility trials for many regulatory cell types. Despite the excitement generated by early clinical trials in autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation, there is as yet no clinically validated, approved regulatory cell therapy for transplantation. In this review, we summarize recent advances in this field, with a focus on myeloid and mesenchymal cell therapies, including current understanding of the mechanisms of action of regulatory immune cells, and clinical trials in organ transplantation using these cells as therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Transplantation is a marvel of modern medicine. Kidney disease, once considered a death sentence until the advent of artificial renal replacement therapies in the early 1900s, is now treated preferentially by kidney transplantation, and offers superior survival and quality-of-life measures in suitable candidates.1 The evolution of transplantation from the first successful kidney transplant2 in 1954, to the standard-of-care prescribed today, is indebted to the combined effort of clinicians, scientists and patients in the quest for improved recipient outcomes. Kidney transplantation is the most common solid organ transplantation procedure performed world-wide.3 The era of increasing demand for organs has necessitated broadening of donor acceptance criteria that use less ideal allografts, and approaches that maximize the benefits from transplantation. Since the ELITE-Symphony study,4 there have been few major therapeutic changes reaching routine clinical care over the last 10 years. Current drug options entail lifelong immunosuppression, and are not without significant disadvantages, increasing the risks of potentially life-threatening infections and unfavorable cardiovascular, metabolic and cancer risk profiles for the recipient. The need to uncover novel therapies to prevent rejection and extend allograft survival, while minimizing exposure of the patient to risks of chronic immunosuppression, remains. Cellular therapy is a novel treatment approach that has gathered interest recently. This review focuses on myeloid-derived cells and mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) to tested to induce tolerance in solid organ transplantation (Figure 1).

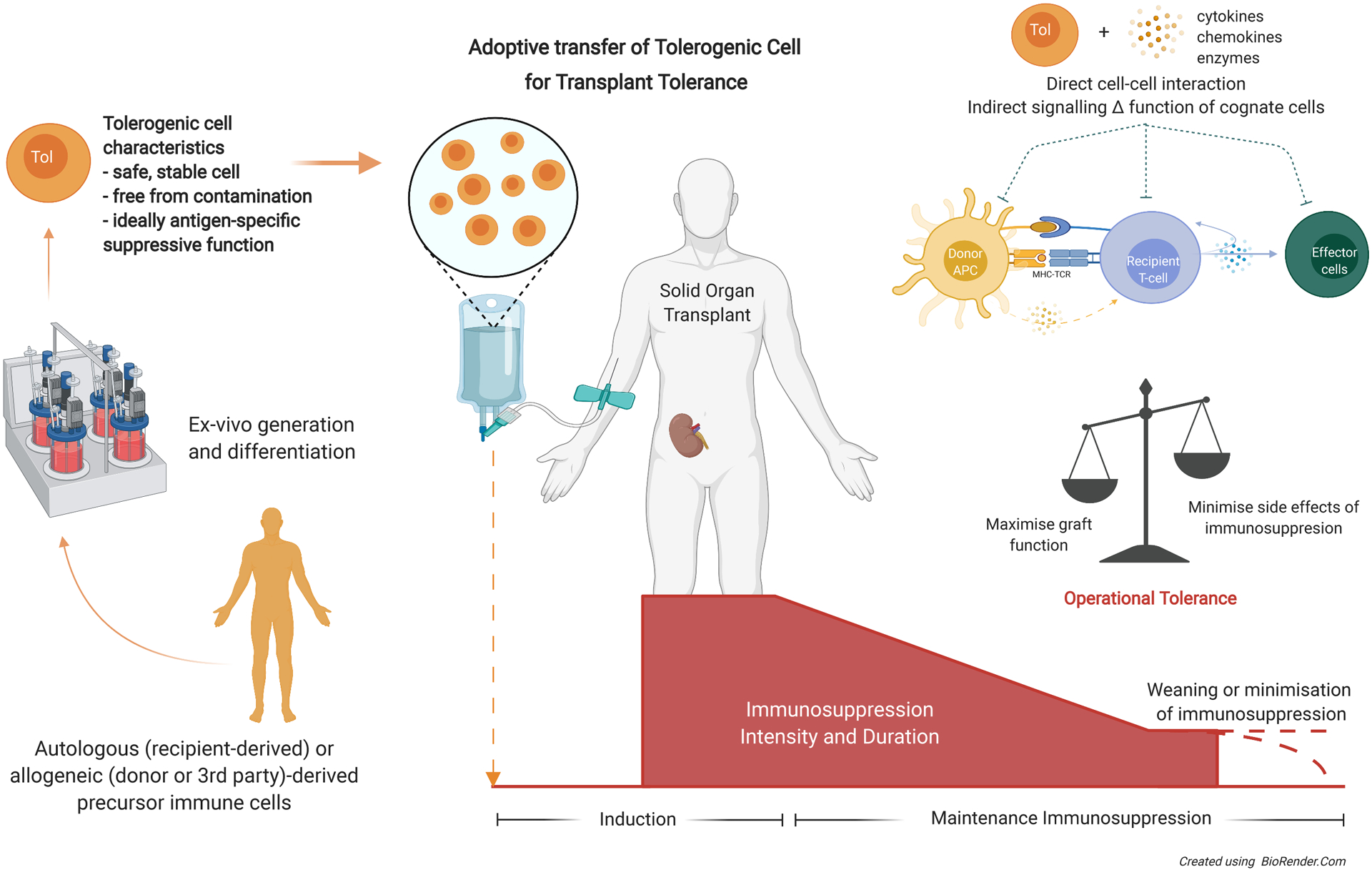

Figure 1.

Concept of tolerogenic cell therapy to reduce the need or intensity of maintenance immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation thus minimizing the adverse side effects while still able to prevent rejection and support graft and patient health. Autologous, allogeneic or third-party derived precursor cells generated and manipulated ex-vivo according to Good Manufacturing Practices guidelines, generating a stable population of tolerogenic cells for adoptive transfer peritransplantation. These tolerogenic cells can act via direct cell-cell interactions or indirectly through the controlled orchestration of cytokines, chemokines or enzymes to influence surrounding cells to either disrupt T-cell activation, differentiation or effector function; or induce differentiation of naïve recipient cells to adopt a suppressive phenotype. APC, antigen-presenting cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TCR, T-cell receptor; Tol, tolerogenic.

TRANSPLANT TOLERANCE AND TOLEROGENIC CELL TYPES

Immunological tolerance is the ‘holy grail’ of transplantation and describes nonreactivity of the recipient’s immune system to the nonself, immunogenic donor allograft.5–7 Achieving full or partial tolerance can help minimize the need for intense pharmacological immunosuppression to prevent rejection, while maintaining requisite immunocompetence to control or prevent infection and malignancy.

Recent research into transplant tolerance has been focused on immune system-donor tissue interfaces: including adoptive cellular therapy, in vivo induction of regulatory cells, co-stimulation blockade and donor hematopoietic cell chimerism.8–16 Studies of rare patients who achieve spontaneous “operational tolerance” (acceptance of the graft without clinically significant rejection in the absence of maintenance immunosuppression) have revealed clues to the potential mechanisms – including the role of various tolerogenic cell populations.17–25

Currently, there is no cell therapy approved for use in human solid organ transplantation although a wide variety of cells have been investigated in preclinical and clinical studies. These include cells from myeloid, lymphoid or mesenchymal lineages. (Figure 2) This review will discuss a selection of adoptive tolerogenic cell therapies, including tolerogenic dendritic cells (tolDC), regulatory macrophages (Mreg); and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) - summarizing recent advances, mechanisms and progress in recent clinical studies (Tables 1–3). Within the constraints of this article, we have not discussed myeloid-derived suppressor cells,26 regulatory T-cells27–30 (Treg) and chimeric antigen receptor Tregs31–34 (CAR-Treg) in which all have translational potential.

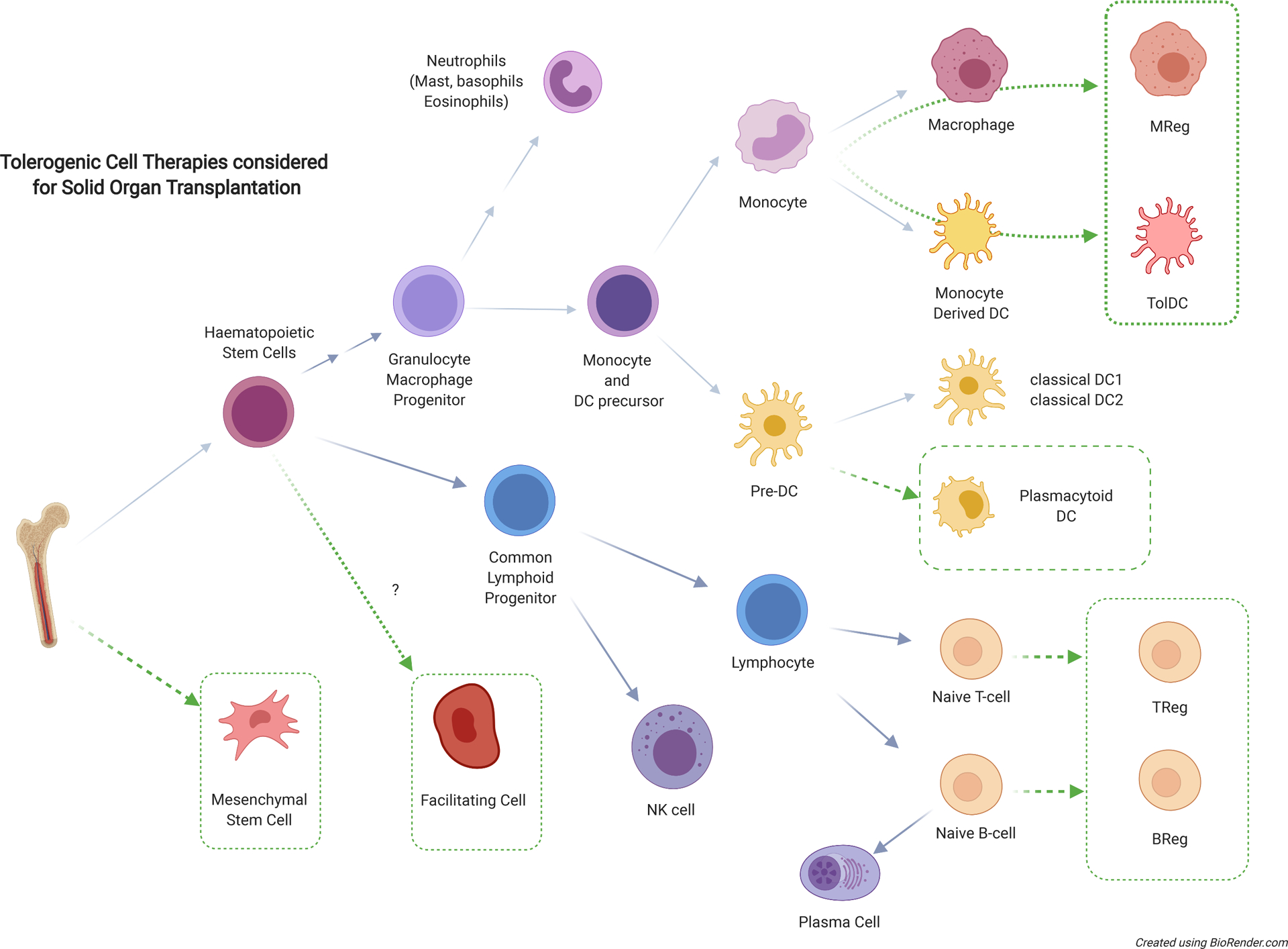

Figure 2.

Simplified overview of hematopoietic or mesenchymal derived cells which have important effector and regulatory roles in transplant immunology – with potential candidates for tolerogenic cell therapy for clinical transplant tolerance highlighted (dotted boxes). BReg, regulatory B cell; DC, dendritic cell; Mreg, regulatory macrophage; NK, natural killer; TolDC, tolerogenic dendritic cell; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Table 1.

Clinical trials of adoptive transfer of tolerogenic dendritic cells in solid organ transplantation.

| Trial (center) | Study | Patients | Cell and dosing | Immunosuppression protocol | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The ONE study ATDC trial

(University of Nantes, part of multinational study) |

Phase I/II clinical trial N = 11 enrolled N = 8 treated |

Living donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, at least 1/6 HLA mismatch, PRA < 40%, did not need desensitization |

Recipient peripheral blood monocytes cultured in low dose GM-CSF for 6 days to generate autologous tolerogenic DCs (ATDC) Dose: 1×106 cells/kg infused day −1 (prior) to transplantation (IV) |

Cell infusion (intervention group) or basiliximab (reference group). Prednisolone tapered off before 20 weeks. Tacrolimus continued throughout the study with target levels specified in keeping with ELITE-Symphony trial. MPA continued until study end but if in cell therapy group, there was an option for deliberate dose tapering from 36 weeks if no evidence of rejection. |

Pooled data for cell therapy group (CTG) of ATDC, Mreg and Tregs Primary endpoint – biopsy proven rejection. Result: no difference between the groups. Secondary endpoint – histological changes of rejection without clinical evidence, eGFR. Result: no difference and CTG also found to have higher population of Tregs and less viral infections compared to reference group |

Sawitzki B et al, 2020104 NCT02252055 NCT01656135 |

|

Donor-derived regulatory dendritic cells in renal transplantation

(University of Pittsburgh) |

Phase I clinical trial Recruiting N = 14 |

Living donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, PRA < 20%, no pre-formed DSA with MFI > 1000 |

Donor derived CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes modified with vitamin D3, IL-10 to generate DCregs Dose: 0.5–5×106 cells/kg (dose escalation) infused 7 days prior to transplantation |

Preconditioning with half dose mycophenolate and donor-derived, tolerogenic DC infusion 7 days prior to surgery. Maintenance with triple immunosuppressive therapy of tacrolimus, mycophenolate and prednisolone as standard of care. |

Primary outcome: composite safety outcomes up to 1 year post transplant with regards to death, infusion reaction, malignancy, de novo DSA, biopsy proven rejection and non-surgical graft loss. In progress |

Thomson A et al, 2016184 NCT03726307 |

|

Donor-derived regulatory dendritic cells in liver transplantation

(University of Pittsburgh) |

Phase I/II clinical trial Enrolment complete N=15 |

Living donor liver transplant Immunological risk: first graft, no autoimmune liver disease; creatinine < 2.5 mg/dl |

Donor derived CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes modified with vitamin D3, IL-10 to generate DCregs Dose: 2.5–10×106 cells/kg infused 7 days prior to transplantation |

Preconditioning with half dose mycophenolate and donor-derived, tolerogenic DC infusion 7 days prior to surgery Maintenance with triple immunosuppressive therapy of tacrolimus, mycophenolate and prednisolone as standard of care. |

Primary outcome: safety and preliminary efficacy (drug withdrawal) to demonstrate operational tolerance. Secondary outcomes – de novo DSA, change in renal function, quality of life or cardiovascular risk In progress |

Thomson A et al, 2018185 Macedo C et al, 2020186 NCT 03164265 |

ATDC, autologous tolerogenic dendritic cell; CTG, cell therapy group; DC, dendritic cell; DCreg, regulatory DC; DSA, donor specific antibody; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GM-CSF, granulocyte and macrophage colony stimulating factor; IL-10, interleukin 10; IV, intravenous; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; MPA, mycophenolic acid; Mreg, regulatory macrophage; PRA, plasma renin concentration; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Table 3.

Clinical trials involving adoptive transfer of MSCs in solid organ transplantation.

| Trial (Centre) | Study | Patients | Cell and dosing | Immunosuppression protocol | Outcomes | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

MSC in living donor kidney transplantation

(Bayer College of Medicine) |

Phase II clinical study Recruiting |

Living donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, PRA < 20%, no DSA |

Autologous MSC Dose: 1, 2, or 3 ×106 cells on day 0 and day 4 postop |

Intervention arm with MSC infusion will receive basiliximab, tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and corticosteroids. Placebo arm will receive similar immunosuppression to the intervention arm but with normal saline instead of MSC infusion. |

Primary outcome – number of patients without Infusion toxicity: venous thromboembolism, respiratory distress, pulmonary edema, hemodynamic instability, myocardial infarction, capillary leak syndrome, acute kidney injury, or biopsy-proven rejection. Secondary outcomes: acute rejection, graft loss or death 6 months posttransplantation. |

NCT03478215 | |

|

MSC and kidney transplant tolerance (Phase A)

(Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Milan) |

Phase I clinical study Recruiting |

Deceased donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, PRA < 10% |

Third party, ex vivo expanded bone marrow- derived MSC 1–2×106 cells/kg |

MSC in addition to kidney transplant protocol but otherwise not specified. | Primary outcomes: number of adverse events, circulating naïve and memory T-cells, regulatory T-cells, T-cell function in mixed leukocyte reaction, urinary Foxp3 mRNA expression. | NCT02565459 | |

|

MSC under basiliximab/low dose rATG to induce kidney transplant tolerance

(Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Milan) |

Phase I clinical study N = 4 |

Living donor kidney transplant | Autologous, bone marrow- derived MSC Dose: 1–2×106 cells/kg 7 days posttransplantation or day −1 prior to transplantation. N = 2 given day −1 N = 2 given day +7 |

MSC infusion vs basiliximab. All patients received low dose rATG and standard triple immunosuppression. Immunosuppression weaning not specified but 1 patient was weaned off cyclosporin at 73 months posttransplantation |

Primary outcome: percentage inhibition of memory T-cell response, induction of T-cell anergy, and induction of Tregs. Secondary outcome: safety parameters to MSC infusion, graft function, and rejection. Study terminated due to severe engraftment syndrome with AKI and evidence of inflammation on biopsies. |

NCT00752479 Perico N et al, 2018200 NCT02012153 |

|

|

MSC and subclinical rejection

(Leiden University Medical Center) |

Phase I clinical study N = 6 |

Living donor kidney transplant with 2/6 HLA mismatch | Autologous, bone marrow- derived MSC (banked prior to transplantation) Dose: 1–2×106 cells/kg 2x doses of MSC 7 days apart |

MSC administered if there was evidence of subclinical rejection or IF/TA on 4 week or 6 month biopsies. Define IF/TA. All patients received standard immunosuppression. |

Primary outcome: resolution of rejection. There was improvement of tubulitis after MSC infusion. Five of 6 demonstrated reduced mixed leukocyte reaction to the donor. Opportunistic infections reported in 50% patients. |

Reinders M et al, 201338 NCT00734396 |

|

|

MSC therapy in kidney recipients

(Leiden University Medical Center) |

Phase II clinical trial N = 70 |

Living donor kidney transplant Excluded if regraft or BPAR ≤6 weeks posttransplantation. |

Autologous, bone marrow- derived MSC Dose: 1×106 cells/kg Given 7 days apart at 6th and 7th week posttransplantation. |

MSCs given posttransplantation and concurrently with everolimus and prednisolone. At 2nd infusion (week 7) – tacrolimus reduced and completely weaned 1 week later. Comparator arm continued on standard dose prednisolone/everolimus/tacrolimus. |

Primary endpoint: fibrosis scores and CNI withdrawal. Secondary endpoint: composite of BPAR, graft loss or death, renal function, proteinuria, and adverse events of opportunistic infection or cardiovascular disease. Awaiting results. |

Reinders ME et al, 2014201 NCT02057965 |

|

|

HLA-matched allogeneic MSC therapy in kidney transplantation (NEPTUNE)

(Leiden University Medical Centre) |

Phase I clinical study N = 10 |

Living donor kidney transplant Risk: first graft, PRA<50% |

Autologous, bone marrow- derived MSC (banked prior to transplantation) Dose: 1–2×106 cells/kg; 2x doses of MSC 7 days apart |

All patients received alemtuzumab, tacrolimus XL, everolimus, and prednisolone. MSC administered if no rejection on 6-month biopsy. MSC donors were matched for each patient without repeated HLA mismatches on split antigen level for HLA-A, -B, -DR, and -DQ. |

Primary outcome: BPAR. Secondary outcome: fibrosis, serious event, renal function, de novo DSA. No difference in BPAR but 2 patients in MSC arm had focal areas of inflammation on biopsy. No de novo DSA. |

Dreyer GJ et al, 202037 NCT 02387151 |

|

|

Induction therapy with autologous MSC for kidney allografts

(Fuzhou General Hospital) |

Phase I clinical study N = 165 |

Living donor kidney transplantation Excluded if regraft or evidence of immunological memory against donor |

Autologous bone marrow- derived MSC Dose: 1–2×106 cells/kg MSC given 24 hr and 2 weeks posttransplant |

The control group received basiliximab, CNI, mycophenolate, and steroids. Intervention groups were given MSC infusion, CNI (standard or low dose), mycophenolate, and steroids. |

Primary outcome: BPAR. Secondary outcome: death, graft survival, and adverse events. Intervention group had less BPAR, fever. Steroid-resistant rejections, better graft function, and fewer opportunistic infections compared to control group within the first year. No engraftment syndrome reported. |

NCT00658073 | |

|

Safety and efficacy of autologous MSC in kidney transplantationy

(Postgraduate Institute of Medical Research, Chandigrah, India) |

Pilot study N = 4 | Living donor kidney transplant | Autologous bone marrow- derived MSC 0.2–0.3 vs 2.1–2.8 ×106 cells/kg given day 0 and day 30 posttransplantation |

All patients received rabbit antithymocyte globulin, CNI, mycophenolate, and prednisolone. MSC given in addition to above. |

Primary outcomes: safety, graft function, rejection, and T-cell immunophenotyping. No rejection on 1-month and 3-month protocol biopsies. Increased proportion of Tregs on immunophenotyping |

Mudrabettu C et al, 2015205 | |

|

Donor-derived MSC combined with low-dose tacrolimus after kidney transplantation

(Sun Yat-Sen University) |

Pilot study N = 12 |

Living donor kidney transplant Immunological risk - first graft - PRA < 10% |

Donor bone marrow-derived MSC 5×106 cells/kg day 0 posttransplantation and further 2×106 cells/kg day 30 |

All patients received cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone induction, along with tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisolone. 6 patients received donor-derived MSC infusion and these patients also had with 0.02–0.04mg/kg dose reduction in tacrolimus compared to the control group. |

Primary outcome: eGFR at 1 month posttransplantation. Secondary outcome: delayed graft function, graft function, patient survival, acute rejection, serious adverse events. Only 1 episode of BPAR in the control group and none in the MSC group. No statistical difference in eGFR over first year. Changes to immune cell population and mixed leukocyte reaction was not durable past 3 months. |

Peng Y et al, 2013207 NCT02561767 |

|

|

Allogeneic MSC as induction therapy in kidney transplantation

(Sun Yat-Sen University) |

Randomized control trial N= 42 |

Deceased donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft |

Umbilical cord blood- derived MSC (allogeneic) Dose: 2×106 cells/kg 30 min prior to transplantation and 5×106 cells/kg intraoperatively before releasing renal artery |

Induction with antithymocyte globulin and methylprednisolone and then standard triple immunosuppression for all patients. Intervention arms received MSC during transplantation. |

Primary outcome: incidence of BPAR and DGF posttransplantation. Pilot results showed no improvement in rates of DGF. No difference in rejection and no significant adverse events recorded. |

Sun G et al, 2012179

Sun Q et al, 2018180 NCT02490020 |

|

|

Infusion of third-party MSC after kidney transplant ation

(University of Liege) |

Phase I/II clinical trial N = 20 |

Deceased donor kidney or liver transplantation Immunological risk: first graft, PRA < 50% |

Third party bone marrow- derived MSC 1.5–3×106 cells/kg |

MSCs given in addition to standard immunosuppression in intervention arm. | Primary endpoints: infusion toxicity, infections, and malignancy outcomes. Secondary endpoint: graft survival, patient survival, liver and kidney function. No acute infusion toxicity noted. No difference in 1-year eGFR or rejection. One patient with cardiac event in MSC group but uncertain if linked. Four patients developed antibodies to MSCs. |

Erpicum P et al, 2019204 NCT01428001 |

|

|

Infusion of MSC after liver transplantation

(University of Liege) |

Phase I/II open label trial N = 10 |

Deceased donor liver transplant Immunological risk: first graft |

Third party bone marrow- derived MSC 1.5–3 ×106 cells/kg given 3 days post liver transplantation |

MSCs given in addition to standard immunosuppression in intervention arm. Weaning of mycophenolate considered in intervention group if no rejection after 6 months. No weaning applied to control arm. |

Primary endpoints: infusion toxicity, infections, and malignancy outcomes. Secondary endpoint: graft survival, patient survival, liver and kidney function. No significant differences in primary outcomes but not able to successfully wean immunosuppression safely in 8 of 9 patients attempted. |

Detry O et al, 2019203 NCT01429038 |

|

|

MYSTEP1 trial

(University Hospital Tuebingen) |

Phase I clinical trial Recruiting |

Living donor liver transplant in the pediatric population | Donor specific, bone marrow-derived MSC obtained 4 weeks pretransplantation. 1×106 cells/kg at day 0 intraportally and day 2 post operatively | MSC in additional to standard immunosuppression. Reduce tacrolimus dose if 6 month protocol biopsy did not show rejection. |

Primary outcomes: MSC infusion toxicity, severe adverse events, and graft function posttransplantation. | NCT02957552 | |

|

MSC therapy in liver transplantation

(Papa Giovanni XXIII Hospital, Bergamo, Italy) |

Phase I trial Recruiting |

Liver transplant Immunological risk: first graft. |

Third party, ex vivo expanded MSCs. 1–2×106 cells/kg at time of transplantation | MSC vs no treatment. Presume in addition to standard immunosuppression but not specified. | Primary outcomes: adverse events, liver CD71 and hepcidin antimicrobial genes, circulating naïve and memory T-cells and changes in mixed lymphocyte reaction. | NCT02260375 | |

|

MSC and islet cotransplantation

(Medical University of South Carolina) |

Phase I clinical trial N = 3 |

Islet transplantation | Autologous, bone marrow derived MSC 20–100×106 MSC/patient |

Islet transplant with autologous MSC following total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. | 2 of 3 patients currently entered in the trial had significant GI or thrombosis adverse events in the first 8 weeks but uncertain if infusion or surgery related. | NCT02384018 | |

|

MSC therapy for lung rejection

(Mayo Clinic) |

Phase I clinical trial N = 9, recruiting |

Lung transplantation Treatment of rejection |

Allogenic bone marrow- derived MSC. Bone marrow purchased from Lonza. Dose: 1, 2, or 4×106 cells/kg |

Treatment refractory bronchiolitis obliterans (moderate to severe lung rejection). | Primary outcome: adverse events, pulmonary function test. Results so far show no serious adverse events or change in pulmonary function in patients who received MSC. Renal function remained stable in the first 30 days post infusion. |

NCT02181712 | |

AKI, acute kidney injury; BPAR, biopsy-proven acute rejection; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; DGF, delayed graft function; DSA, donor specific antibody; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; GI, gastrointestinal; IF/TA, interstitial fibrosis/tubular atrophy; mRNA, messenger RNA; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PRA, plasma renin concentration; rATG, rabbit antithymocyte globulin; Treg, regulatory T cell.

WHAT IS AN ‘IDEAL’ TOLEROGENIC CELL?

In keeping with the principle of nonmaleficence, tolerogenic cells must be immunologically safe to administer. Once given, they must not provoke any pro-inflammatory responses, not undergo unexpected cellular phenotype switching (ie, tolerogenic-to-activated effector cell type), nor excessive, nonspecific immunosuppression (ie, lead to increased risk of infections or malignancies). Establishing safety has been a major priority to development of cellular therapies in transplantation given the potentially serious consequences. This includes host sensitization to allogeneic cells, graft rejection, or potential increased susceptibility to infection if there is excessive immunosuppressive potential of the cell product.

Tolerogenic cells provide benefit when given in addition to, or in place of, standard immunosuppression that the patient would have otherwise received (beneficence). A particular advantage might include the ability to selectively dampen the immune response to donor alloantigen. There should be a reasonable therapeutic window, where sufficient shift occurs towards a state of donor-specific unresponsiveness, but not limit the immune response to nondonor antigens. The therapeutic window must also be achievable within the constraints of required dosing – ensuring a reasonable cell number and/or volume which would be straightforward to culture or manufacture. In some trials, cells may be given pretransplantation, peritransplantation, or posttransplantation with single or multiple doses of specific product.

WHICH PATIENTS SHOULD RECEIVE TOLEROGENIC CELL THERAPY?

Ideally, all patients suitable for transplantation should be considered for tolerogenic cell therapy. However, risk of rejection from immunosuppression reduction or withdrawal is not equally distributed amongst the organs and this factor is reflected in the selection of patient groups in current cell therapy trials. Recipients of living donor kidney or liver transplants have dominated contemporary studies of cellular therapies and tolerance given the overall lower immunological risk and restricted time-period during which cells can be prepared. Other solid organ transplants have been excluded given the high-risk of rejection and associated morbidity and mortality, especially following cardiac and lung transplantation. Highly sensitized patients or patients with underlying autoimmune disease are also less likely to be studied, given the increased risk of rejection and intensive immunosuppression regimens required. Cell products investigated thus far are derived from either donor or recipient sources and generated or expanded ex vivo. This creates a significant lag time and potential barrier for recipients of deceased donor organs if protocolized cell therapies are to be given pretransplantation or peritransplantation. Some phase I studies have administered Tregs35,36 and MSC37,38 months after liver or kidney transplantation and have not demonstrated significant adverse outcomes, although the efficacy is yet to be proven. Potentially, this could be circumvented by development of third-party cell biobanks (akin to umbilical cord-derived Tregs and MSC) that could be accessed as ‘off-the-shelf’ products. This strategy has been successful for CAR T-cells for use in hematological cancers and antigen-specific CD8+ T-cells for resistant viral infections following allogeneic stem cell transplantation.39–42

SOURCE AND REGULATION OF TOLEROGENIC CELLS

Sufficient numbers of circulating, physiologically intrinsic tolerogenic cells are difficult to isolate from donors for use in solid organ transplantation. Hence, ex vivo expansion of precursor cells, followed by appropriate in vitro manipulation is required to obtain adequate numbers of tolerogenic cells. These cells can be derived from the recipient (autologous), donor, or third party (allogenic). Details as to manipulation of precursor cells will be discussed in the following sections but most commonly, precursor cells are derived from peripheral blood, in particular peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) can also be derived from peripheral blood, but other potential sources include bone marrow, umbilical blood and nonlymphoid tissue such as skin, adipose and muscle.43 Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) produced through reprogramming of somatic cells can be a source of MSCs, but to date have only been used in experimental models of organ transplantation or human hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for prevention of graft-versus-host disease.44–46

Tolerogenic cells for human use are viewed as a medium-to-high risk category biological product - they require ex vivo manipulation and are intended for nonhomologous use (expected function being different to originally derived product).47 Specific requirements by regulatory bodies for these products may vary depending on the country and institution undertaking the clinical study, but at a minimum, most regulatory agencies require compliance with the Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines. GMP guidelines allow for standardization in manufacturing biological products to ensure consistent and controlled quality standards that are appropriate for use of cellular products in human trials. GMP practice dictates standards from organizations and facility management, to product production and distribution. Cells produced to GMP quality fulfil a set of predefined release criteria specific to each individual trial. This often details the cell product’s viability, purity, phenotype, function determined with in vitro bioassays and sterility (with maximum allowable endotoxin and microbial contamination limits)48–50 (Figure 1). These release criteria can vary for each cell type and center, introducing a major source of heterogeneity that needs to be considered when reviewing results of studies, particularly given the small sample sizes of most human transplant tolerance studies.

IMPORTANT OUTCOMES FOR CELL-BASED THERAPIES IN TRANSPLANT TOLERANCE

Generally, in organ transplantation, biopsy proven rejection and/or graft survival has been reported as the primary outcomes to evaluate treatment effects of cell therapy. The presence of subclinical rejection, patient and graft survival, graft function and adverse events, including infusion reactions and opportunistic infections heralding over-immunosuppression have been commonly recorded as secondary outcomes. Of note, studies to date incorporated relatively short duration follow-up, often limiting observation time to 1 year. Current studies are also still relatively early phase I/II trials with small and select groups of recipients. This is understandable given progress to date, with investigators now overcoming major technical challenges to produce the desired cell product in sufficient numbers to meet target cell doses. Furthermore, these cell therapies have generally been tested in relatively low immune risk recipients (unsensitized or patients at low risk of rejection) and in living-donor transplant settings (particularly useful current studies focusing on cell therapy given before or at time of transplantation, allowing sufficient time for cell expansion). Development of HLA-matched third-party cells or banked autologous cells may be of interest if more studies explore the role of cell therapy post transplantation.

Future refinement to select suitable, higher risk candidates may be identified through the ‘molecular microscope’, identifying genomic biomarkers of patients who might benefit most from tolerogenic therapies.51–55 Standardized in vitro testing of cellular products prior to infusion, and validation of clinical and laboratory biomarkers or surrogate end points (with potential to incorporate various ‘-omics’ technologies and bioinformatics)56 to optimize future study design.

Myeloid-derived Tolerogenic Cell Therapies

Antigen-presenting cells (APC) have an important role in maintaining central and peripheral tolerance. Clonal deletion of CD4+CD8+ thymocytes and Treg generation for central tolerance is dependent upon antigen presentation to thymic T-cells57 and experimental depletion of APC can lead to dysregulation of immune tolerance and development of autoimmune phenomena.57–59 Furthermore, APC are the first responders of innate immunity, initiating inflammatory cascades and also orchestrating adaptive immune response through allorecognition following transplantation. Given their central, promulgating role in inflammation, manipulation of macrophages or DC to achieve tolerance is appealing with robust research directed at tolerogenic myeloid DC (TolDC) and regulatory macrophages (Mreg).

Mechanisms of TolDC-and Mreg-induced tolerance

These APC share common progenitors and overlapping features but can be distinguished by tissue residence and functional phenotype.60–63 Tissue-resident cells are specialized myeloid cells which continually survey the parenchymal microenvironment and are important in both initiation and resolution of inflammation.64 Tissue-resident cells are donor-derived passenger leukocytes which accompany the allograft during transplantation and can participate in both direct or semi-direct alloantigen presentation. In addition, monocyte-derived APC can be found in the allograft, either from donor or recipient origin, and can also initiate inflammation and rejection through either direct, indirect or semi-direct alloantigen recognition65–70 (Figure 3). Administration of TolDC or Mreg may disrupt canonical T-cell activation by professional APC, leading to a state of functional or peripheral tolerance. This may be through either secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines and expression of immunomodulatory surface molecules leading to T cell anergy, apoptosis and/or induction of regulatory T-cells (iTreg).71–73

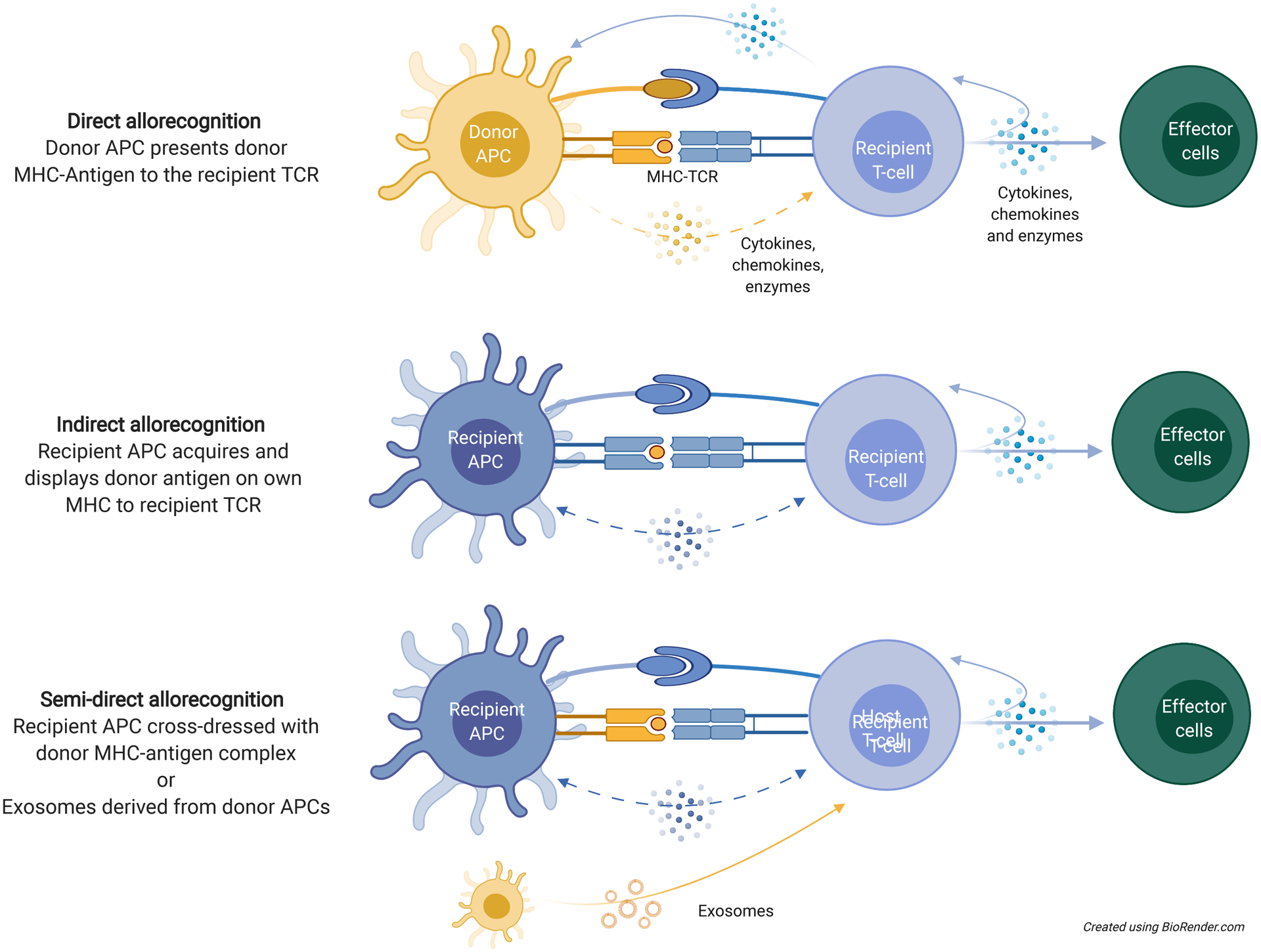

Figure 3.

Important pathways of alloantigen recognition in transplant sensitization and rejection. Direct alloantigen recognition involves presentation of an intact MHC-antigen complex by donor APCs to recipient lymphocytes. Indirect allorecognition occurs through recipient APC uptake of donor-derived antigen molecules to present to lymphocytes. Semi-direct allorecognition can occur through exosomes (delivering microRNA and donor-content to recipient lymphocytes) or cross dressing of recipient APCs with donor-derived MHC-antigen complexes by trogocytosis. From antigen recognition to effector cell differentiation, all are potential targets through which tolerogenic cells can exert their effects. APC, antigen-presenting cell; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TCR, T-cell receptor.

TolDC can stimulate the expansion of conventional CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ iTreg, functionally-suppressive T regulatory-1 cells (Tr1, CD4+CD25−Foxp3−) and possibly CD8+ regulatory T-cells through upregulation of IL-10 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO).57,74–77 TolDC may further stimulate IL-10 secretion by CD19hiFcγIIbhi regulatory B cells (Breg).78–82 TolDC can also upregulate CTLA-4 expression (an important inhibitory feedback signal of T cell activation83,84), release TGF-β (stimulating expansion of tolerogenic Treg),85 and increase PD-L1-PD1 signaling (reducing T-cell proliferation and survival). The latter receptor phosphorylates the immunoreceptor tyrosine based inhibitory motif (ITIM) and recruits Src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-1 (SHP1) and SHP2 to block TCR signaling and proliferation.86,87 TolDC can also inhibit T cell differentiation by preventing CD39 ectonucleotidase-mediated breakdown of extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and subsequent activation of the pro-inflammatory purinergic P2X7-TLR-MyD88 signaling pathway.88–91

Tissue macrophages are important sentinels of danger signals, including pro-inflammatory cytokines,92 and mediate an important role in allograft rejection.93 Exposure of macrophages to IL-4 or IL-10 can polarize towards an M2 phenotype,94–98 that is associated with anti-inflammatory characteristics and release of further IL-10 and TGF-β.99,100 Similar to TolDs, Mregs can produce regulatory cytokines or metabolites (such as IL-10, IDO) that promote the formation of iTreg (TIGIT+ Treg),101,102 influence indirect and semi-direct antigen presentation of Mreg-antigens by intact APCs, and reduce T-cell proliferation or survival through iNOS pathways.103

Preparation and Requirements of TolDC and Mreg cells for adoptive transfer

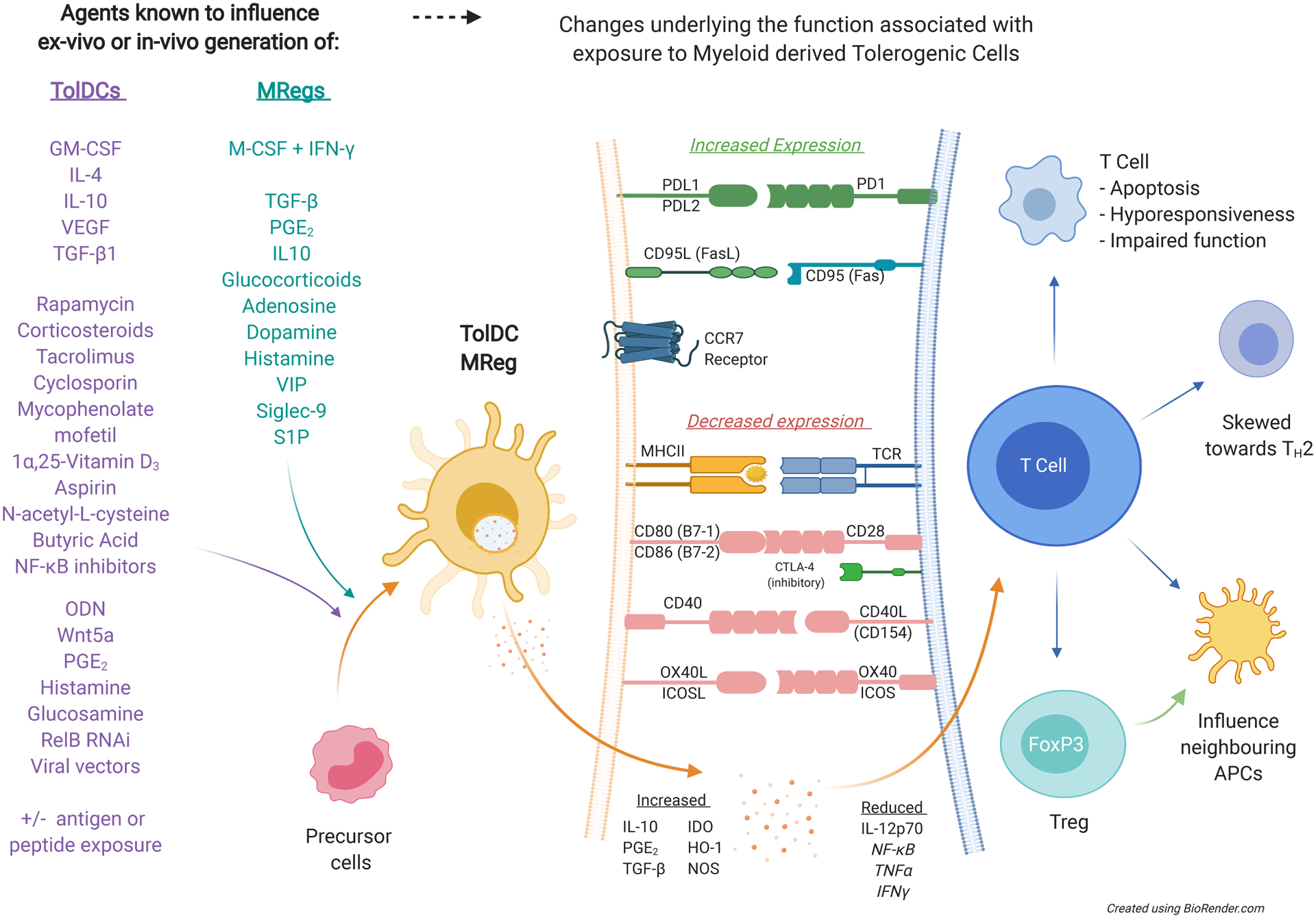

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are an accessible, renewable cell pool that can be purified and manipulated into a desired myeloid cell type. They form the basis for most ex vivo protocols that generate human tolDC or Mreg. Recipient (autologous) or donor (allogeneic) blood can be used to purify CD14+ monocytes, which are then exposed to specific cytokines or growth factors in culture to direct their differentiation into the preferred regulatory population (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Overview of mechanisms underlying how TolDCs or Mregs achieve tolerance through direct cell-cell contact with altered expression of co-stimulatory and co-inhibitory molecules. These cells can also influence the cells in the immediate microenvironment through altered cytokine, chemokine, and/or enzyme release to influence downstream cell survival, differentiation, and function. See abbreviations list for cytokine, chemokine and enzyme details. APC, antigen-presenting cell; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; FoxP3, foxhead box p3; GM-CSF, granulocyte and macrophage colony stimulating factor; HO-1, haem oxygenase-1; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; IL-4, interleukin 4; IL-10, interleukin 10; M-CSF, macrophage colony stimulating factor; Mreg, regulatory macrophage; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; ODN, oligodeoxynucleotide; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; RNAi, RNA interference; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; TCR, T-cell receptor; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor beta 1; TH2, T-helper cell type 2; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; TolDC, tolerogenic dendritic cell; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VIP vasoactive intestinal peptide.

Mreg used in The One Study104 and earlier pilot studies105–107 were generated by exposing donor-derived CD14+ monocytes to low dose macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and stimulation with interferon gamma (IFN-γ). Prespecified criteria used to characterize these Mreg included a CD14loCD16loCD80loCD86loCD85hloCD258lo phenotype, tessellating epithelioid morphology, suppression of T cell proliferation in mixed leukocyte culture, elevated IDO, and <1% contamination with T lymphocytes.108–112

Early phase trials of donor- or recipient-derived tolDC have delivered ex vivo-generated, maturation-resistant DC also derived from circulating CD14+ monocytes.113–115 Autologous TolDC (ATDC) are attractive in that they avoid the potential risk of host sensitization, and murine models demonstrate their effectiveness in promoting heart allograft tolerance.111,116,117 The use of ATDC in humans was demonstrated in the DC arm of the ONE study,104 using recipient-derived PBMC exposed to low-dose GM-CSF for 6 days before administration 1 day before kidney transplantation. These cells met similar criteria described above for Mreg but needed to demonstrate a HLA-DRloCD80loCD86loCD83loCD40lo immature phenotype and show maturation resistance to LPS ± IFNγ in vitro. The results are encouraging, adding to evidence supporting the use of PBMCs from patients with kidney disease. Despite the cells being derived from a uremic environment, they can generate functional tolDC.112 However, efficacy of (donor antigen-pulsed) host-derived tolDC was lower than of tolDC generated from healthy donors in nonhuman primates.118,119

Clinical trials of living donor kidney or liver transplantation use donor-derived monocytes cultured in GM-CSF, IL-4, vitamin D3 and IL-10. Defined release criteria included >95% tolDC purity, expression of the tolerogenic surface markers HLA-DR−CD11c+CD14−CD40loCD80lo CD86loPD-L1hiCCR7+CD83lo, a PDL-1:CD86 ratio > 2.5 and cell culture supernatant with high IL-10 and low IL-12p70 levels.109,118,119 There are also early phase clinical studies using tolDC in autoimmune diseases not covered in this review.110,120–124

GM-CSF, 1α,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3 (vit D3) are commonly used in protocols for tolDC generation125–128 resulting in low-level expression of MHC and co-stimulatory molecules, production of IL-10, failure to prime T-cells and induction of Treg proliferation.129 Vit D3 has also been combined with dexamethasone and produces CD14+CD11chiDC-SIGN+CD1a− tolDC with elevated PD-L1:CD86 that promotes Treg or Tr1-like Treg.27,129,130 Other agents that have been studied in combination with vit D include monophosphoryl lipid A and LPS.130–132 In the presence of stimuli that activate TLR2 and TLR4, or ligands for pattern recognition receptors, tolDC display maturation resistance, with low-to-intermediate levels of CD80, CD86, CCR7, higher levels of CCR4/5, and increased IL-10 compared to immunogenic or classical DC.126,133 These DC retain the ability to home to inflamed tissue via CXCR3 and CCR7.127,134

An important consideration is what happens to tolDC or Mreg once infused and exposed to the effects of anti-rejection medications. All transplant recipients receive some regimen of glucocorticoids for immunosuppression and traditionally these are thought to influence a wide variety of gene expression, including inhibition of pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling and activation of protein-1 transcription factors. Recent evidence suggests that glucocorticoids can alter cellular immune pathways and the transcriptomes of myeloid and lymphoid cells within hours of administration, and have been used in some protocols for generating tolerogenic cell products.101,135–141 Other medications, including tacrolimus, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, rapamycin and minocycline have been used modulate DC phenotype.115,133,142–144 Animal studies suggest that tolDC effects are retained when they are administered concurrently with conventional immunosuppression given that these agents are also known to inhibit DC maturation, with reduced MHC and co-stimulatory molecule expression, lower IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ and increased IL-10 and TGF-β production.145–147

The tissue microenvironment provides important paracrine signals to influence myeloid cell maturation, and phagocytosis of local apoptotic bodies can add to their immunoregulatory function through production of TGF-β. Sterile inflammation such as rejection can also induce counter-regulatory myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC) through the MyD88 pathway.148–152 Alternative methods to generate tolDC113,114,153 include the use of the NF-kB inhibitor (Bay 11-7082),154 butyric acid,155 aspirin,156 vit D with IL-10,118,119 minocycline,143 TGFβ,157 protein kinase inhibitor,157 vasoactive intestinal peptide,158 hepatic growth factor,159,160 Flt3 ligand inhibitor,161,162 CTLA4-Ig,163 Wnt5a,164 monophosphoryl lipid A,165 silencing of IL-12p35166 or RelB and NFκB,167 genetic engineering to increase expression of IL-10, TGF-β or CTLA4,168 CCR7169 or Fas-ligand,170 TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand,171 exosomes,111,117 apoptotic bodies and peptides172 from donor-derived leukocytes. The ability of apoptotic cell capture to promote DC tolerogenicity, including use of photopheresis (extracorporeal photochemotherapy) to induce apoptosis, together with evidence that acquisition of donor-derived apoptotic cell products induces the expansion of donor-specific Treg in transplant recipients has been reported.172–174

Clinical trials using TolDC and MReg

Preclinical studies in mice and primate models have demonstrated the benefit of adoptive myeloid cell therapies to improve outcomes in heart, islet, liver and kidney transplantation,175–180 whereas recent clinical trials have addressed the translational potential of adoptive tolDC or Mreg cell therapy (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Clinical trials of adoptive transfer of regulatory macrophages in solid organ transplantation.

| Trial (center) | Study | Patients | Cell and dosing | Immunosuppression protocol | Outcomes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The ONE study

Mreg trial (University of Regensburg) |

Phase I/II clinical trial N = 8 enrolled N = 2 treated |

Living donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, at least 1/6 HLA mismatch, PRA < 40%, did not need desensitization |

Allogeneic (donor-derived) CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes co-cultured with low dose M-CSF with IFNγ stimulation on day 6 for 24hr. Dose: 2.5–7.5×106 cells/kg infused 7 days prior to transplantation |

Cell infusion (intervention group) or basiliximab (reference group). Prednisolone tapered off before 20 weeks. Tacrolimus continued throughout the study with target levels specified in keeping with ELITE-Symphony trial. MPA continued until study end but if in cell therapy group, there was an option for deliberate dose tapering from 36-weeks if no evidence of rejection. |

Pooled data for CTG of autologous tolerogenic DCs, Mreg and Tregs Primary endpoint – biopsy proven rejection. Result: no difference between the groups. Secondary endpoint – histological changes of rejection without clinical evidence, eGFR. Result: no difference and CTG also found to have higher population of Tregs and less viral infections compared to reference trial group |

Sawitzki B et al, 2020104 NCT02085629 |

|

Regulatory macrophages (University of Regensburg) |

Pilot study N = 5 |

Living donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, did not need desensitization, anti-HLA Ab < 5% |

Donor-derived CD14+ peripheral blood monocytes cultured with low dose M-CSF with IFNγ stimulation Dose: 1.74–10.39×107 cells/kg on day 5 post transplantation |

Induction with antithymocyte globulin, tacrolimus and corticosteroids. Steroids weaned by day 14 if no concerns for rejection and physician had option to wean down tacrolimus dose if nil rejection on first protocol biopsy at 8 weeks. |

Primary outcome: biopsy-proven rejection. 4 of 5 patients were able to be maintained on low dose tacrolimus One biopsy proven rejection in context of low tacrolimus levels (2–4 ng/ml) |

Hutchinson J et al, 2008105 |

| Regulatory macrophages (Mreg) | Pilot study N = 10 |

Deceased donor kidney transplant Immunological risk: first graft, all HLA mismatch groups allowed |

Donor-derived, CD14+ monocytes cultured with low dose M-CSF with IFNγ stimulation on day 6, ready for use by day 7 culture Dose: 1.37–9×107 cells/kg administered 5 days post transplantation |

Induction with tacrolimus, sirolimus, and corticosteroids. Steroids and sirolimus were weaned over the duration of the study |

Primary outcome: biopsy-proven rejection. 7 of the 10 patients who received Mreg suffered confirmed (or suspected) rejection episodes between 6–28 weeks post transplantation. |

Hutchinson J et al, 2008106 |

Ab, antibody; CTG, cell therapy group; DC, dendritic cell; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IFNγ, interferon gamma; M-CSF, macrophage colony stimulating factor; MPA, mycophenolic acid; Mreg, regulatory macrophage; PRA, plasma renin concentration; Treg, regulatory T cell.

The ONE Study104 was a landmark early clinical trial of regulatory cell therapy. This was a multinational study consisting of 6 parallel arms of distinct cell therapy groups (CTG) and a reference group of 66 patients who received living-donor kidney transplants. Patients of high immunological risk were excluded (re-graft, PRA > 40% or needing desensitization), as were patients who were an exact HLA match with their donors. Both groups received the same regimen of prednisolone, mycophenolate and tacrolimus, but the reference group received basiliximab induction instead of cell therapy and patients were followed up for median of 60-weeks. The CTG received a prespecified dosing regimen of either tolDC, Mreg or Treg peritransplantation, with optional dose tapering of mycophenolate during the study period a minimum of 36 weeks had elapsed since time of transplantation. This was a phase I/II clinical trial with 38 patients in the CTG group – including 8 patients in the autologous tolDC arm (University of Nantes) and 2 patients in the donor-derived Mreg arm (University of Regensburg). Given the small numbers, results were pooled for analysis and found no difference in the primary outcome of incidence of biopsy-proven acute rejection (BPAR) between CTG and reference groups. Tapering of immunosuppression to tacrolimus monotherapy was successfully achieved in 15 of 38 patients in the CTG group. Two patients failed attempted tapering – suffering either biopsy-proven rejection or IgA recurrence. There was no significant difference between groups with regard to secondary endpoints (subclinical rejection, estimated glomerular filtration rate, or measured de novo donor specific antibodies). The study also reported a higher proportion of Treg in recipient peripheral blood and reduced rates of viral infection in the CTG compared to the reference group.

This ONE report documents the largest cohort tested with regulatory immune cells in kidney transplantation and shows these products can be safely administered and that maintenance immunosuppression may be minimized following regulatory cell therapy. While the numbers in the myeloid-based arm are small but encouraging. Comparison to basiliximab treatment allows direct comparison with current standard-of-care induction immunosuppression. Although basiliximab standard of care group was not a true control group since the CTG group had a greater option of dose tapering, we know from earlier studies that immunosuppression weaning is not always safe, nor reliably predictable in ‘low-risk’ kidney transplant recipients – with mixed results for mycophenolate181,182 and increased risk of rejection following tacrolimus withdrawal in the immunologically quiescent recipient.183 The potential value of Mreg in deceased donor transplantation is uncertain, with an earlier pilot study by the same group requiring major revisions to their study protocol early due to safety concerns when 5 of 7 patients needed treatment for suspected or confirmed rejection in the context of maintenance tacrolimus, sirolimus and steroid combination with unsuccessful weaning to tacrolimus monotherapy.105

TolDC generated from donor-derived monocytes cultured with GM-CSF, IL-4, vit D3 and IL-10 are currently being investigated in 2 phase I/II clinical trials of living donor liver or kidney transplantation at the University of Pittsburgh. Allogeneic tolDC are infused 7 days prior to transplantation, concurrently with half-dose mycophenolate until transplantation. The kidney transplant study stipulates patients remain on standard triple immunosuppression of prednisolone, tacrolimus and mycophenolate, whilst the liver transplant study includes protocolized weaning of prednisolone by 1 week, mycophenolate by 12 months and potentially tacrolimus between 12–18 months if 12 month protocolized transplant biopsies were rejection-free.184–186 These 2 trials are in progress at time of writing. The aim of these studies is to evaluate feasibility and safety, and to obtain preliminary mechanistic insights – which will allow for refinement of future human and preclinical studies.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells

MSCs have been investigated for clinical use since the 1990s, with expansion to over 200 clinical trials. The broad therapeutic application of MSCs has spawned several companies and FDA approval for use in pediatric, steroid-resistant GVHD.187 The development of commercially-available third-party MSCs is particularly useful for therapy at short notice, but needs to be balanced against the risk of allo-sensitization. MSCs have also received attention over the last decade for treatment of acute kidney injury,188 RA,189 and MS.190

Mechanisms of MSC and transplant tolerance

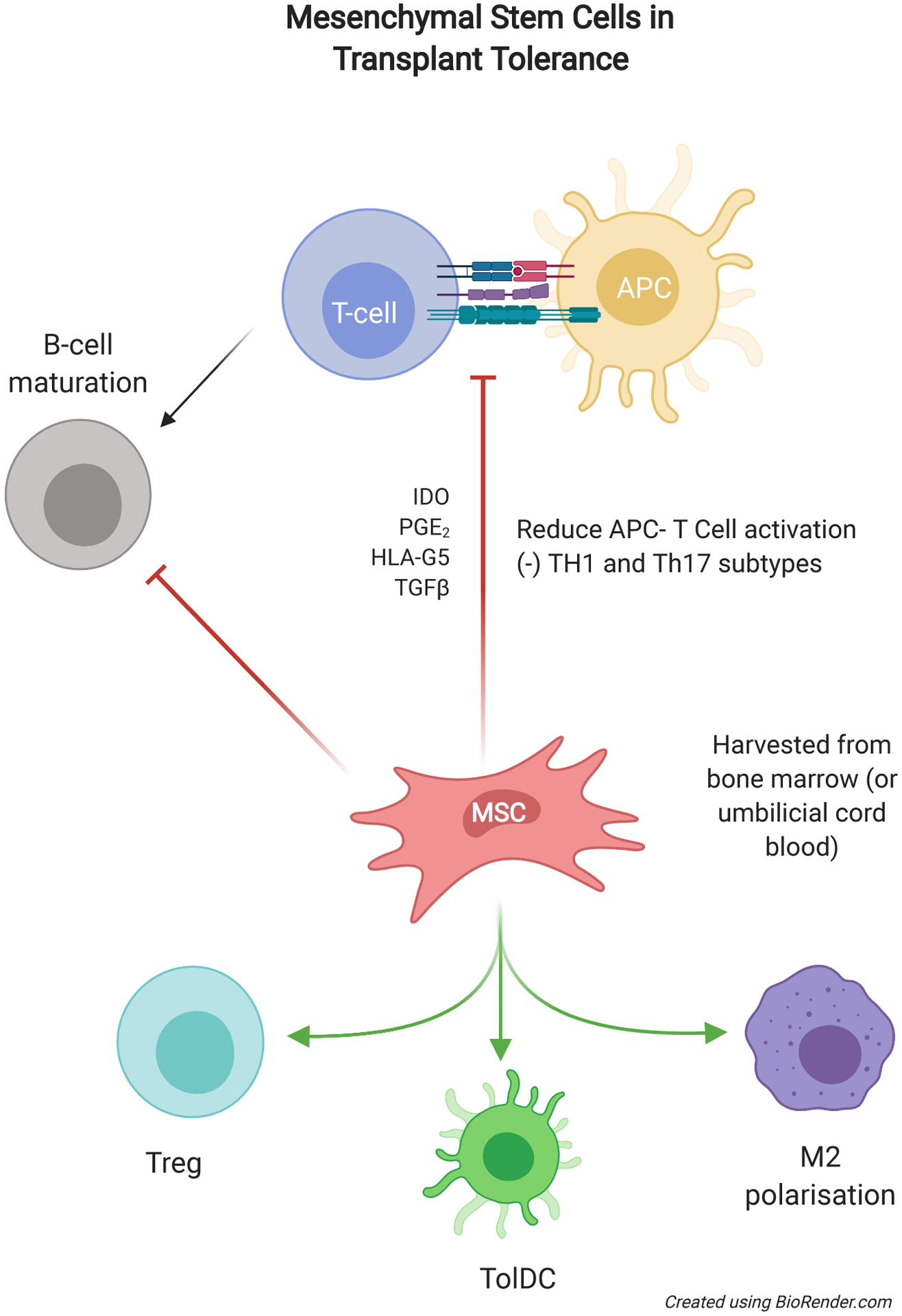

Like myeloid-derived tolerogenic cells, MSCs also promote improved graft survival in preclinical rodent and primate models and are thought to exert immunomodulatory effects on both innate and adaptive immune pathways. Generation of Foxp3+ Tregs is the favored mechanism through which MSCs exert transplant tolerance.191,192 MSCs can impair APC maturation and reduce signal 1 and signal 2 presentations at the APC-T-cell interface. This in turn, reduces the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12 and IFN-γ), and limits activation of effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. MSCs also promote proliferation of Treg and impair B-cell maturation following sterile inflammation and can influence monocyte/macrophage polarization, skewing towards the M2 phenotype.193,194 MSCs produce many of the same soluble factors as tolDC and Mreg, particularly IDO, PGE2, TGF-β, HLA-G5 and NO, and utilize CXCL9 and CXCL10 to attract and affect immunomodulatory of cells within close proximity8,43,195,196 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Overview of the use of MSC for renal transplantation in the quest for tolerance. MSCs have a wide range of influences on the immune system with both suppressive effects on activation and maturation can promote differentiation of immune cells into regulatory or suppressive phenotypes. APC, antigen-presenting cell; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PGE2, prostaglandin E2; TGFβ, transforming growth factor beta; TolDC, tolerogenic dendritic cell; Treg, regulatory T cell.

Preparation and requirements of MSCs for adoptive transfer

Sources of MSCs typically include third-party umbilical cord blood, as well as donor or autologous bone marrow in solid organ and hematological stem cell transplantation. iPS cells are another promising population from which to generate these MSC, but have yet to be tested in human solid organ transplantation. Primary cells expanded in bioreactors and can be identified as multipotent MSCs by criteria determined by the International Society for Cellular Therapy. MSCs are defined as cells which adhere to plastic, differentiate into skeletal tissue in vitro, and express CD105, CD73, CD90, but not cell surface CD34, CD45, CD14, CD11b, CD19, CD79α or HLA-DR.8 Use of MSCs to promote transplant tolerance have similar GMP requirement for CD73+CD90+CD105+ phenotype and usually <2% CD34+ or CD45+ contamination, compatible morphology, and karyotype stability. It is important to note that karyotype stability alone is insufficient to determine genetic stability and there is the potential tumorigenic risk of increased passages during ex-vivo expansion.197–199

Clinical Trials using MSC

Early clinical studies administering autologous, bone marrow-derived MSCs in living donor kidney and liver transplantation38,43,200–207 have shown mixed results. Most phase I trials demonstrate relative safety in transplant recipients, (Table 3) but one study conducted in Italy (NCT00752479) described focal inflammatory infiltrates in renal biopsies when MSCs were administered to living-related kidney transplant recipients with basiliximab and low-dose rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin induction followed by cyclosporin/mycophenolate maintenance therapy. This was thought to be a severe engraftment phenomenon, leading to early termination and revision of future trial protocols.43,200,208 Another phase I trial performed in the Netherlands (NCT00734396) tested posttransplant use of MSCs in living donor kidney transplantation. Patients had 2 HLA-DR mismatches and received standard induction with basiliximab, and calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)/mycophenolate/prednisolone therapy.38 Two of the 6 patients showed evidence of inflammation suggestive of subclinical rejection and one further exhibited biopsy-proven rejection. This was in addition to transient declines in renal function thought to be engraftment reaction. Five of the 6 patients showed some degree of inhibition of donor-specific immunity, with reduced proliferation in a mixed leukocyte reaction. These results led to the development of the Neptune study (NCT02387151),37 a single-center phase Ib study in which MSCs were given to 10 patients, 6 months after living donor kidney transplantation and with clean 6-month surveillance biopsies. Patients received alemtuzumab induction and prednisolone/everolimus/tacrolimus maintenance therapy. Importantly, this trial used third-party, allogeneic MSCs that were typed to avoid repeated HLA-mismatches at -A, -B, -DR and -DQ loci. At 1 year post transplant, there were no cases of BPAR, and 1 patient showed subclinical rejection with borderline change histology. Despite the HLA mismatches on MSC products, there were no de novo DSAs detected postinfusion. Thirty percent of patients had detectable BK viremia but no evidence of nephropathy, and a similar number suffered from herpes zoster. Infusion or engraftment reactions were not reported, and it was noted that pro-inflammatory cytokines were not significantly elevated following MSC infusion.

The largest cohort of kidney transplant recipients treated with MSCs comprised 159 patients in a study conducted at the Fuzhou General Hospital, China.209 This was a single-center, randomized control trial where autologous BM--derived MSCs were prepared a month prior to transplantation and given at the time of and 2 weeks posttransplantation. The control group was given basiliximab instead of cell therapy and all patients were maintained on CNI, mycophenolate and steroids. This protocol is similar to that of The ONE study, except that low dose prednisolone was maintained for all patients and the cell therapy group received both standard and low-dose (80% of standard) CNI immunosuppression regimens. Fifty-three patients were enrolled in each of the 3 groups. There was a lower risk of BPAR in the MSC group compared to controls, regardless of CNI dose. Interestingly, only patients in the control (basiliximab induction) group had steroid-resistant rejection requiring anti-thymocyte globulin. The trend of better outcomes in the cell therapy group was also seen in the eGFR within the first-year posttransplantation. Twelve-month patient and graft survival was similar between the groups and not surprisingly, the MSC with low-dose CNI had the lowest incidence of opportunistic infections. These studies add significantly to the body of evidence that MSCs may be beneficial in allowing reduced intensity of maintenance immunosuppression, but the results require both validation and longer-term follow-up. The effectiveness of MSCs in high immunological risk and/or deceased donor transplantation is untested.209 Trials using MSCs need to be carefully designed given the risk of engraftment-related side effects, graft inflammation, excess immunosuppression potentially contributing to opportunistic infections and malignancy210,211 and known thrombogenic risks associated with activation of platelet and coagulation system.212,213 One trial with MSCs as treatment of severe lung rejection214 is ongoing, and another study combines MSCs with autologous islet transplantation following total pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis.215

Conclusion

Regulatory immune cell therapy exploits the cell’s inherent capacity to negatively influence cognate immune effector cells. We have highlighted the importance of myeloid and mesenchymal lineage regulatory cells which show potential as adjuvant immunosuppressive agents in clinical studies. The results so far are encouraging, but future cell therapy studies need to show significant benefit over current standard-of-care to justify the potential risks and resource investment. Current barriers to more widespread use of tolerogenic cell therapy in solid-organ transplantation include:

Clinical trials to date largely exclude recipients of higher immunological risks (higher risk grafts such as cardiac transplantation or higher risk individual such as re-graft or high panel reactive antibody titers), time-challenged scenarios of deceased donor kidney transplantation, or whether these cells can be used in the injured allograft (with delayed graft function or active rejection). These important issues will need to be addressed to justify cell therapy use outside the lower immune risk recipients of living donor transplants and duration of the effects of cell therapy.

Clinical efficacy is yet to be proven – the optimal protocol for dosing and timing of administration is yet to be determined and greater number of patients will need to be included in trials to provide more robust evidence. Recruitment will be a major barrier given it is an issue in transplantation-based interventional studies in general and may need additional strategies such as enrichment of the patient cohort and utilizing pragmatic or adaptive therapies in the future when there are more phase II/III clinical trials.

Active monitoring for adverse effects needs to be ongoing, with the ONE study having the longest reported follow up period so far. The duration of the effects of cell therapy are unknown and will need longer term observed and censored data to ensure there is no excess in major adverse events.

Further monitoring of the immune landscape and exploration of the molecular mechanisms that underlie tolerogenic cell function will allow for greater precision in cell generation and trial design to achieve these aims.

Supplementary Material

Financial Disclosure:

J.L. is a recipient of the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) postgraduate scholarship (GNT116877) and the Westmead Association BJ Amos Travelling scholarship. N.M.R. is supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (GNT1158977) and Project Grant (GNT1138372). A.W.T. is the recipient of research grants from the US National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI118777, U19 AI131453, and U01 AI136779).

Abbreviations

- APC

Antigen-presenting cell

- ATG

anti-thymocyte globulin

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- BReg

regulatory B cell

- CAR-T cell

Chimeric antigen receptor-T cell

- CNI

calcineurin inhibitor

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

- DC

dendritic cell

- FCx

facilitating cell

- Foxp3

foxhead box p3

- GM-CSF

granulocyte and macrophage colony stimulating factor

- GVHD

graft versus host disease

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- HO-1

heme oxygenase-1

- ICOS

inducible T-cell costimulator

- ICOSL

inducible T-cell costimulatory ligand

- IDO

indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IFN-γ

interferon gamma

- LAG3

lymphocyte activation protein 3

- M-CSF

macrophage colony stimulating factor

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- Mreg

regulatory macrophage

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NK cell

natural killer cell

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- ODN

oligodeoxynucleotide

- PD1

programmed death protein 1

- PDL1, PDL2

programmed death ligand 1 and 2

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta

- TH1

T-helper cell type 1

- TH17

T-helper cell type 17

- TolDC

tolerogenic dendritic cell

- TRAIL

tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis inducing ligand

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- Wnt5a

wingless-related integration site 5a

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Rose C, Gill J, Gill JS. Association of kidney transplantation with survival in patients with long dialysis exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(12):2024–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker CF, Markmann JF. Historical overview of transplantation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(4):a014977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ANZDATA Registry. Chapter 7: Kidney Transplantation. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 42nd Report Last updated June 18, 2020. Available at https://www.anzdata.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/c07_transplant_2018_ar_2019_v1.0_20200525.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2021.

- 4.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. New Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2562–2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roussey-Kesler G, Giral M, Moreau A, et al. Clinical operational tolerance after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(4):736–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massart A, Ghisdal L, Abramowicz M, et al. Operational tolerance in kidney transplantation and associated biomarkers. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;189(2):138–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood KJ, Bushell A, Hester J. Regulatory immune cells in transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(6):417–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casiraghi F, Perico N, Cortinovis M, et al. Mesenchymal stromal cells in renal transplantation: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(4):241–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li XC, Turka LA. An update on regulatory T cells in transplant tolerance and rejection. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(10):577–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braza MS, van Leent MMT, Lameijer M, et al. Inhibiting inflammation with myeloid cell-specific nanobiologics promotes organ transplant acceptance. Immunity. 2018;49(5):819–828.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirk AD, Turgeon NA, Iwakoshi NN. B cells and transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6(10):584–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ochando J, Fayad ZA, Madsen JC, et al. Trained immunity in organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(1):10–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson AW, Ezzelarab MB. Regulatory dendritic cells: profiling, targeting, and therapeutic application. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2018;23(5):538–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kinnear G, Jones ND, Wood KJ. Costimulation blockade: current perspectives and implications for therapy. Transplantation. 2013;95(4):527–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alegre ML, Mannon RB, Mannon PJ. The microbiota, the immune system and the allograft. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(6):1236–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Messner F, Etra JW, Dodd-O JM, et al. Chimerism, transplant tolerance, and beyond. Transplantation. 2019;103(8):1556–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswas SK, Gangi L, Paul S, et al. A distinct and unique transcriptional program expressed by tumor-associated macrophages (defective NF-kappaB and enhanced IRF-3/STAT1 activation). Blood. 2006;107(5):2112–2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heymann F, Tacke F. Immunology in the liver--from homeostasis to disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13(2):88–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerut J, Sanchez-Fueyo A. An appraisal of tolerance in liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(8):1774–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazariegos GV, Reyes J, Marino IR, et al. Weaning of immunosuppression in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1997;63(2):243–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaked A, DesMarais MR, Kopetskie H, et al. Outcomes of immunosuppression minimization and withdrawal early after liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(5):1397–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson AW, Tevar AD. Kidney transplantation: a safe step forward for regulatory immune cell therapy. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1589–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newell KA, Asare A, Kirk AD, et al. Identification of a B cell signature associated with renal transplant tolerance in humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1836–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newell KA, Asare A, Sanz I, et al. Longitudinal studies of a B cell–derived signature of tolerance in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(11):2908–2920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scalea JR, Lee YS, Davila E, et al. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their potential application in transplantation. Transplantation. 2018;102(3):359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira LMR, Muller YD, Bluestone JA, et al. Next-generation regulatory T cell therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18(10):749–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin-Moreno PL, Tripathi S, Chandraker A. Regulatory T cells and kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(11):1760–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu M, Wang YM, Wang Y, et al. Regulatory T cells in kidney disease and transplantation. Kidney Int. 2016;90(3):502–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoogduijn MJ, Issa F, Casiraghi F, et al. Cellular therapies in organ transplantation. Transplant Int. 2021;34(2):233–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Noyan F, Zimmermann K, Hardtke-Wolenski M, et al. Prevention of allograft rejection by use of regulatory T cells with an MHC-specific chimeric antigen receptor. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(4):917–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferreira LMR, Tang Q. Generating antigen-specific regulatory T cells in the fast lane. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(4):851–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohseni YR, Tung SL, Dudreuilh C, et al. The future of regulatory T cell therapy: promises and challenges of implementing CAR technology. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, Lu W, Liang CL, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) Treg: a promising approach to inducing immunological tolerance. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez-Fueyo A, Whitehouse G, Grageda N, et al. Applicability, safety, and biological activity of regulatory T cell therapy in liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(4):1125–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chandran S, Tang Q, Sarwal M, et al. Polyclonal regulatory T cell therapy for control of inflammation in kidney transplants. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(11):2945–2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dreyer GJ, Groeneweg KE, Heidt S, et al. Human leukocyte antigen selected allogeneic mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in renal transplantation: the Neptune study, a phase I single-center study. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(10):2905–2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinders MEJ, de Fijter JW, Roelofs H, et al. Autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of allograft rejection after renal transplantation: results of a phase I study. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2(2):107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blyth E, Jiang W, Clancy LE, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplant (HSCT) for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL) using CD34 selected stem cells followed by prophylactic infusions of pathogen-specific and CD19 CAR T cells. Cytotherapy. 2020;22(5):S17–S18. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gowrishankar K, Birtwistle L, Micklethwaite K. Manipulating the tumor microenvironment by adoptive cell transfer of CAR T-cells. Mamm Genome. 2018;29(11):739–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sutrave G, Gottlieb DJ. Adoptive cell therapies for posttransplant infections. Curr Opin Oncol. 2019;31(6):574–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Withers B, Clancy L, Burgess J, et al. Establishment and operation of a third-party virus-specific T cell bank within an allogeneic stem cell transplant program. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24(12):2433–2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Podestà MA, Remuzzi G, Casiraghi F. Mesenchymal stromal cells for transplant tolerance. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sequiera GL, Saravanan S, Dhingra S. Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells as an individual-specific and renewable source of adult stem cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1553:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bloor AJC, Patel A, Griffin JE, et al. Production, safety and efficacy of iPSC-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in acute steroid-resistant graft versus host disease: a phase I, multicenter, open-label, dose-escalation study. Nat Med. 2020;26(11):1720–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshida S, Miyagawa S, Toyofuku T, et al. Syngeneic mesenchymal stem cells reduce immune rejection after induced pluripotent stem cell-derived allogeneic cardiomyocyte transplantation. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yano K, Speidel AT, Yamato M. Four Food and Drug Administration draft guidance documents and the REGROW Act: a litmus test for future changes in human cell- and tissue-based products regulatory policy in the United States? J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(7):1579–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bedford P, Jy J, Collins L, et al. Considering cell therapy product “good manufacturing practice” status. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018;5:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kalantari T, Kamali-Sarvestani E, Ciric B, et al. Generation of immunogenic and tolerogenic clinical-grade dendritic cells. Immunol Res. 2011;51(2–3):153–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian code of good manufacturing practice for human blood and blood components, human tissues and human cellular therapy products. Version 1.0 2013. Available at https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/manuf-cgmp-human-blood-tissues-2013.pdf. Accessed March 17, 2021.

- 51.Martínez-Llordella M, Lozano JJ, Puig-Pey I, et al. Using transcriptional profiling to develop a diagnostic test of operational tolerance in liver transplant recipients. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(8):2845–2857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tambur AR, Campbell P, Claas FH, et al. Sensitization in Transplantation: Assessment of Risk (STAR) 2017 working group meeting report. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(7):1604–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiebe C, Kosmoliaptsis V, Pochinco D, et al. HLA-DR/DQ molecular mismatch: a prognostic biomarker for primary alloimmunity. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(6):1708–1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiebe C, Rush DN, Nevins TE, et al. Class II eplet mismatch modulates tacrolimus trough levels required to prevent donor-specific antibody development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(11):3353–3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O’Connell PJ, Zhang W, Menon MC, et al. Biopsy transcriptome expression profiling to identify kidney transplants at risk of chronic injury: a multicentre, prospective study. Lancet. 2016;388(10048):983–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karczewski KJ, Snyder MP. Integrative omics for health and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(5):299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Audiger C, Rahman MJ, Yun TJ, et al. The importance of dendritic cells in maintaining immune tolerance. J Immunol. 2017;198(6):2223–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen M, Wang YH, Wang Y, et al. Dendritic cell apoptosis in the maintenance of immune tolerance. Science. 2006;311(5764):1160–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohnmacht C, Pullner A, King SBS, et al. Constitutive ablation of dendritic cells breaks self-tolerance of CD4 T cells and results in spontaneous fatal autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2009;206(3):549–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-resident macrophage ontogeny and homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44(3):439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ancuta P, Crowe S, et al. Nomenclature of monocytes and dendritic cells in blood. Blood. 2010;116(16):e74–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rogers NM, Ferenbach DA, Isenberg JS, et al. Dendritic cells and macrophages in the kidney: a spectrum of good and evil. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(11):625–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kurts C, Ginhoux F, Panzer U. Kidney dendritic cells: fundamental biology and functional roles in health and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16(7):391–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):986–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marino J, Paster J, Benichou G. Allorecognition by T lymphocytes and allograft rejection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Benichou G, Thomson AW. Direct versus indirect allorecognition pathways: on the right track. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(4):655–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hughes AD, Zhao D, Dai H, et al. Cross-dressed dendritic cells sustain effector T cell responses in islet and kidney allografts. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(1):287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakayama M. Antigen presentation by MHC-dressed cells. Front Immunol. 2015;5:672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quaglia M, Dellepiane S, Guglielmetti G, et al. Extracellular vesicles as mediators of cellular crosstalk between immune system and kidney graft. Front Immunol. 2020;11:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morelli AE, Bracamonte-Baran W, Burlingham WJ. Donor-derived exosomes: the trick behind the semidirect pathway of allorecognition. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2017;22(1):46–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Ann Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hill M, Cuturi MC. Negative vaccination by tolerogenic dendritic cells in organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2010;15(6):738–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li H, Shi B. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and their applications in transplantation. Cellular & molecular immunology. 2015;12(1):24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kohli K, Janssen A, Förster R. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce tolerance predominantly by cargoing antigen to lymph nodes. Eur J Immunol. 2016;46(11):2659–2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]