Abstract

Objective

To understand the perspectives of persons’ living with diabetes about the increasing cost of diabetes management through an analysis of online health communities (OHCs) and the impact of persons’ participation in OHCs on their capacity and treatment burden.

Patients and Methods

A qualitative study of 556 blog posts submitted between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2017 to 4 diabetes social networking sites was conducted between March 2018 and July 2019. All posts were coded inductively using thematic analysis procedures. Eton’s Burden of Treatment Framework and Boehmer’s Theory of Patient Capacity directed triangulation of themes with existing theory.

Results

Three themes were identified: (1) cost barriers to care: participants describe individual and systemic cost barriers that inhibit prescribed therapy goals; (2) impact of financial cost on health: participants describe the financial effects of care on their physical and emotional health; and (3) saving strategies to overcome cost impact: participants discuss practical strategies that help them achieve therapy goals. Finally, we also identify that the use of OHCs serves to increase persons’ capacity with the potential to decrease treatment burden, ultimately improving mental and physical health.

Conclusion

High cost for diabetes care generated barriers that negatively affected physical health and emotional states. Participant-shared experiences in OHCs increased participants’ capacity to manage the burden. Potential solutions include cost-based shared decision-making tools and advocacy for policy change.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: BoTF, Burden of Treatment Framework; BS, blood sugar; DME, Durable Medical Equipment; HMO, health maintenance organization; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; IRB, institutional review board; OHC, online health community; PLWD, person living with diabetes; PPA, Partnership for Prescription Assistance; RX, prescription; T1D, type 1 diabetes; TPC, Theory of Patient Capacity

In the United States, approximately 34.1 million adults 18 years or older live with diabetes.1 This epidemic will only grow because 84 million people have prediabetes and an estimated 15% to 30% of these will develop type 2 diabetes within 5 years, bringing the total number to 46.7 million by conservation estimates.2 Simultaneously, health care costs for diabetes treatment have skyrocketed, due in part to the increase in insulin cost and lack of generic glucose-lowering medication.3 From 2002 to 2013, out-of-pocket expenses have increased from $231.48 to $736.09 per year per individual.3 These expansions of cost have resulted in significant financial burden for persons living with diabetes (PLWDs),4 which is associated with cost-related medication rationing, and blood glucose levels above guideline-suggested targets.5,6

Participant-shared experiences in online health communities (OHCs; eg, forums, support groups, and social media groups) are an easily accessible and efficient data source that have been widely used to assess treatment effects, adherence, and perceived quality of care from the end-user perspective.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Through these OHCs, PLWDs also have the opportunity to share their experiences, feelings, and therapy options with their peers.16

To date, it is not known how PLWDs express care-related cost concerns online. Therefore, in this study we aimed to understand, through systematic exploration of OHCs, participants’ perceptions of cost-related diabetes management concerns to provide new insights about the financial burden of living with diabetes.

Patients and Methods

This qualitative study used data retrieval of public anonymous posts from discussion websites of PLWDs. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures as exempt (IRB #17-008326).

Study Design and Population

Three researchers (C.C.G., J.P.B., and G.S.B.) used an iterative process of keyword selection to identify 88 keywords related to diabetes cost, supplies, and medications from 13 OHCs. We used a custom Python-based Web scraper to retrieve participants’ posts from 4 diabetes social networking sites (Helparound, SparkPeople, Diabetes Daily, and TuDiabetes). Though all posts were public, demographic information and consent were not obtained because participants’ information was not publicly available, so all personal identifiers (eg, user name and state) were removed in accordance with the IRB and a unique ID was created for each post so that it could be followed in a thread anonymously. We used Fuzzy Matching to identity noise, such as synonyms and spelling variations (Supplemental Table 1, available online at https://mcpiqojournal.org). In total, we located 965,478 unique posts created between 2007 and 2017. Of these, 13,982 posts had at least 2 keywords each. After we identified the most frequently appearing keywords, we used a filter to ensure that each retained post had at least 3 keywords, resulting in 1639 posts (Supplemental Table 2, available online at https://mcpiqojournal.org). After this step, a statistician was consulted to identify a random sample of the TuDiabetes posts because the data would otherwise comprise 82% (1,364/1,649) of the total posts and overrepresent within the overall sample. Therefore, the 556 posts for analysis were composed of all posts from Helparound, SparkPeople, and Diabetes Daily and a random sample of 20% (271/1,364) of TuDiabetes posts (Supplemental Table 3, available online at https://mcpiqojournal.org).

Data Analyses

Thematic Analysis

All data were coded by 3 coders (C.C.G., N.R.E.S., and F.J.K.T.) using Nvivo 11 software (QSR International) between March 2018 and July 2019. We first read and reread the posts to familiarize with the data. As a pilot, we coded 40 posts in triplicate using line-by-line coding following reflexive thematic analysis methods until calibration was complete.17,18 In conducting this process, we created a standardized codebook with codes and code definitions. Subsequently, we used the codebook to continue coding independently and met weekly to discuss additional codes and refine existing ones. Following coding, 2 researchers (N.R.E.S. and A.S.M.Z.) conducted data synthesis using matrices and the query function in Nvivo 11 to explore overlapping concepts. This resulted in themes inductively derived from the data.

Theoretical Triangulation

In the second phase of analysis, we explored our themes in relation to existing theories relevant to the current work: Eton’s Burden of Treatment Framework (BoTF) and Boehmer’s Theory of Patient Capacity (TPC).19,20 Briefly, BoTF describes the work done by patients to take care of their health, the challenges that exacerbate the burden, and the impacts that work has on their quality of life.21 The TPC describes the necessary components of patient capacity required to mobilize capacity to handle the work and burden of living with chronic illness.19

We primarily used memo writing to aid our review of the data during this phase of analysis and met regularly with other researchers (C.C.G. and F.T.B.) to ensure credibility.22 Author K.R.B. reviewed the coding and analysis to ensure confirmability of the data. Disagreements were discussed among the researchers until consensus was achieved. After final analysis, 3 main themes and 6 subthemes were identified.

Reflexivity

It is important to acknowledge our backgrounds, and the 3 coders are from immigrant backgrounds. Therefore, it is possible that we may have approached the data with biases concerning our own experiences with health care in our countries of origin. Consequently, we may have felt empathetic toward participants’ feelings and judge targets of frustration, such as the insurance industry, harshly. Finally, our core research team is housed in the endocrinology research unit. Therefore, our clinical experience with insulin may contribute to an expectation of insulin cost burden. To recognize these biases and their potential risks to the research, our team met regularly to discuss these issues.

Results

Thematic Analysis

We identified 3 main themes: cost barriers to care, impact of financial cost on health, and saving strategies to overcome cost impact. These themes demonstrate multiple facets of care challenges and how participants try to address these obstacles.

Cost Barriers to Care

Participants expressed how navigating insurance policies and the health care system inhibited their access to prescribed therapies. These barriers act to increase participants’ self-described burden of treatment. We identified 3 subthemes that further explicate this issue. A common factor is the negative effect of the insurance system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Theme 1: Cost Barriers to Care; Subthemes Include Concerns Specific to Economic, Personal, and Environmental Barriers

| Bureaucratic Cost Barriers | Quote |

|---|---|

|

1.1. “Pods are so expensive—I'm on disability as well and there's no way Medicare would pay for supplies—even the other insurance united won't pay for supplies. They feel pumps are a luxury.” 1.2. “I bet insulin is outrageous in price! My insurance covered a brand new pump... But they will not cover the supplies… a 3-month supply would cost roughly $900 ....” 1.3. “Can only get a box of 5 from pharm, cost $145. I can't get money until Monday. Out of my pen tonight.” 1.4. “In January, my insurance rates are going up almost 50%. I realize that every year health care costs go up but this is absurd. My insurance company has no documentation to justify this high increase.” 1.5. “I’m on a PPA assistance program through Lilly but they haven’t sent in my medicine lately. I’m still waiting. So while I was waiting I had to go out and buy some insulin. It came to 108 dollars. That is nuts!!! Why is insulin so expensive?” |

|

1.6. “Recently as a college student with no job I have had problem buying my insulin.” 1.7. “I will check with my insurance to see if it covered too because I am not working and every little bit helps. And the cost of medication is high enough as it is without insurance.” 1.8. “I had health insurance during my latter college years, covered by college, but the Rx coverage was horrible and I racked up some credit card debt paying for insulin and other D-supplies.” 1.9. “I don't have money for an Omnipod I work a bunch and am still broke my husband doesn't work I am the only one working and we can barely afford our bills.” |

|

1.10. “I'm on Medicaid in Washington state, and they've just changed to an HMO type admin, with new policies. Now, they will only cover 1 box of 100 strips for each 3 months!... I really hate it that people who are NOT our physicians (in fact, not physicians at all!) are making decisions on what we need." 1.11. “A pack of 5 Apidra pen cartridges would cost me just over $40, and that's in Canadian dollars, so with today's exchange it's more like $30 in the US. Lantus is more expensive (perhaps twice the cost), but that's still under $100 in both countries (or should be!)." 1.12. “It is in Belgium with basically unlimited amounts of strips provided for free and only very low costs for insulin. In Belgium the amount of free strips is limited to 5 a day but you get all the insulin for free. But in both countries you can live with T1D without it being a huge financial burden." 1.13. “My company just switched from United Healthcare to Blue Cross Blue Shield Texas… my pump supplies were covered under pharmacy side with United so only having to pay a copay per month, no deductible had to be met. NOW, with BCBSTX they will only cover under DME and so until my high deductible is met, have to pay outright at $350 per month for supplies. Can't afford that for sure ... I am IDDM type ... I did not have good control without the pump and had to take so many injections per day. Been doing rather well on the pump. Scares me to think about not having my pump anymore.” |

DME, Durable Medical Equipment; HMO, health maintenance organization; IDDM, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus; PPA, Partnership for Prescription Assistance; RX, prescription; T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Economic Barriers

Several participants described how economic barriers negatively affected their diabetes care. Situations described by participants included insufficient insurance coverage (Table 1, quotes 1.1 and 1.2) and high out-of-pocket cost affecting treatment access (quote 1.3). In addition, insurance policy unreliability was a major concern for participants. Participants complained about unexpected changes in insurance policies that worsened access to diabetes treatment (quote 1.4). They also voiced economic struggles despite using assistance programs (quote 1.5).

Individual Barriers

Participants’ individual context was also a barrier for treatment. Participants described how employment status affected their income, insurance status, and insurance coverage (quotes 1.6, 1.7, and 1.8). Participants who financially supported their families reported that the high cost of supplies made it difficult to simultaneously access adequate supplies of medicine and support their families to the extent required (quote 1.9).

Environmental Barriers

Participants reflected about issues caused by their environmental context. Participants commented on comparisons not only between states but also between the United States and other nations to describe how policies influenced supply and insulin access (quotes 1.10, 1.11, and 1.12). Participants pointed out that situations related to insurance coverage were out of their control, yet affected their ability to complete daily treatment goals (quote 1.13).

Impact of Financial Cost on Health

Participants described how the aforementioned barriers affected their quality of life and health. Two subthemes elaborate on this further (Table 2).

Table 2.

Theme 2: Impact of Financial Cost on Health; Subthemes Include Impact on Care (physical), as Well as Emotional Impact

| Quote | |

|---|---|

| Impact on care | 2.1. “I’m so medically broke I’m going to have to go back to injections. I’ve been on a pump since 2006 and insulin since 1981. I am only 34 years old but I know as soon as I go back to injections my life expectancy will decrease.” 2.2. “The many times I’ve ran out of Lantus over the past year, I tried taking just Humalog (I have plenty of it) and it always was a disaster, even when checking my BS (around the clock) every 2 to 4 hours, it never worked out.” 2.3. “Insulin is outrageous in price! I have had to go back on injections since my insurance doesn't really pay much for infusion sets, my company on infusion sets is $500 for 3 months.” |

| Emotional impact | 2.4. “What am I supposed to do? I can't live without insulin, how can these insurance companies do this...Now I'm super scared to even try and fill my pump supplies, they're going to tell me I owe a million dollars for them. I don't know what to do, I've had diabetes for 25 years and a pump for 18 and I've never had to deal with this.... so frustrated.” 2.5. “I was told by a pharmacy clerk that a man did not have any insurance and needing insulin it cost 900.00. He could not get it. He was given 3 needles for his insulin and was told by his doctor I hope you get some help and have a good day. What? How can these insurance companies get away with this? Profit before helping folk. What an ugly world we live in.” 2.6. “Well now I have insurance through my job and it sucks. I just picked up a 1 one supply of insulin and had to pay $550.00 out of pocket. The pharmacy told me that the insurance company covered some of it. I started crying of anger because I can't afford $550.00 right now, let alone every single month.” 2.7. “Now, they will only cover 1 box of 100 strips for each 3 months!... unless you turn in a copy of your logs to prove you use more than that. That's 1 test a day...! ...so whether I like it or not I HAVE to log it now if I want to test when I need it! I really hate it that people who are NOT our physicians (in fact, not physicians at all!) are making decisions on what we need... ARRRRGH!” |

BS, blood sugar.

Impact on Care

Participants discussed concerns regarding negative physical health outcomes due to lack of access to adequate treatment (Table 2, quote 2.1). These limitations forced participants to make treatment changes with a subsequent decline in subjective quality of life (quote 2.2). Participants described situations in which they were forced to make treatment decisions based on economic considerations, sometimes without physician input and other times directly disregarding a physicians’ prescribed treatment (Tables 1 and 2, quotes 1.2, 2.2, and 2.3).

Emotional Impact

Participants expressed concern about the emotional burden of health care, which was implicitly present in most of the coded posts. Many reported feelings of frustration and hopelessness when confronted with insufficient coverage and access to necessary supplies and medications (quotes 2.4 and 2.5). Additionally, participants reported feeling anger and mistrust toward insurance providers and anguish regarding the negative influence that the high cost of health care had on their overall quality of life (quotes 2.6 and 2.7).

Strategies to Overcome Cost Impact

Participants used OHCs to share strategies and experiences that address the cost of diabetes care (Table 3).

Table 3.

Theme 3: Strategies to Overcome Cost Impact; These Include Resources for Saving Money and Social Support

| Strategies to Overcome Cost Challenges | Quote |

|---|---|

|

3.1. “Here are a couple of ideas. TrueTrack seems to be the cheapest meter and strips to get and also the Walmart brand. I have an accu-check that I got for $20 on sale at Rite-Aid and i get my strips free through the company because I have no insurance.” 3.2. “I had a very expensive copay with my old meter and the strips where [sic] around $75 each vial. My doctor suggested I change to the Reli On meter (Walmart brand) I don't recall what I spent on the meter, but the strips are 9 dollars per vial and you don't need a prescription.” 3.3. “I ordered some strips online through Amazon for half the price, then getting through store or pharmacy, my daughter recommended.” 3.4. “In order to keep the cost down load a coupon for Tresiba which, when used with insurance, your co pay is only $15. This discount is ok to use for 2 years.” 3.5. “So I look for better deals. One is, buy your insulin in Canada, Seven bottles of Lilly Humalog for less than $400 including shipping. Your insurance may not reimburse you but if you can get them to put the cost against your deductible it is worth it.” 3.6. “Yeah, the prices in US are ridiculous. I've been buying my Humalog through Canadian pharmacy for the last couple of years @ 1/3 the price. It's shipped directly from Turkey where it's manufactured for Lilly.” 3.7. “Patient Assistance Program Roche Diagnostics has established a Patient Assistance Program in the United States that provides free ACCU-CHEK blood glucose test strips to people with diabetes who cannot afford them. Patients can contact the Roche Patient Assistance Program at 866-441-4090 for information about the program and eligibility requirements.” 3.8. “Most hospitals have Patient advocates who should be able to tell you where to turn for help. If nothing comes from there try diabetes office or contact your representative.” 3.9. “Yes, it's happening worldwide. My charity, link, recently collected anecdotal prices of insulin and people pay anywhere from $3 to $60 per vial. We are building an advocacy force for this issue and other similar issues to ensure that everyone with type 1 has affordable insulin and supplies.” |

Frequently, saving strategies were shared. Use of specific brands or stores, online shopping, and access to online coupons were often suggested (Table 3, quotes 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, and 3.4). Shopping abroad was also a strategy mentioned (quotes 3.5 and 3.6). Participants brought up the possibility of accessing assistance programs to get free or less expensive supplies (quotes 3.7. 3.8, and 3.9).

Theoretical Triangulation

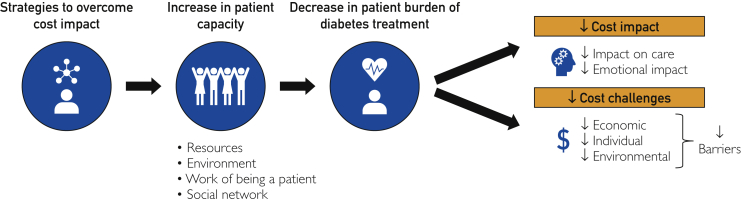

In comparing the themes with existing theory (TPC and BoTF), we found that participants shared strategies to positively influence various components of capacity. Specifically, these strategies increased participants’ capacity through increasing their available resources in the form of economic and educational information, expanding their social network reach through forum use, and broadening their environmental access to social support programs or community resources in their respective regions. Finally, all these tools reduce workload by sharing tools to save energy and money.

When participants increase their capacity, they are better able to overcome the cost burden of care. By overcoming the cost burden of diabetes care, negative health care outcomes related to rationing behaviors and emotional impact can be reduced (Figure).

Figure.

Information shared on online health communities increases patients' capacity to fulfil therapy goals while decreasing the burden associated with performing diabetes care, ultimately improving health outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of Findings

We found that the high cost for diabetes care generated 3 main cost-related barriers: economic, individual, and environmental. These barriers negatively affected physical health and emotional states. Furthermore, theoretical triangulation was used to show how participants exemplify resiliency. In particular, OHCs are used to increase knowledge and social capital. This information is then used in real life to alleviate diabetes care–related burden. Whether intentional or unintentional, PLWDs can increase capacity through this approach.

Limitations and Strengths

There are certain limitations related to working with data from OHCs. Self-reported experiences are subject to bias due to its subjective nature. Therefore, we cannot verify the veracity or magnitude of statements or if entries are submitted by PLWDs. Another limitation is that we did not subdivide data based on time before and after the enactment of the Affordable Care Act, which sought to reform insurance and health care systems to ultimately improve health care access, increase quality, and decrease cost. Though the Affordable Care Act provisions increased insurance coverage, the findings continue to be relevant due to the persistence of racial and socioeconomic disparities.23,24 Further, self-selection bias may contribute to a limited set of experiences or perspectives since online participation is voluntary. Individuals may be uncomfortable sharing private information, even if anonymous. Although all data were collected from free websites, online participation is also informed by health literacy, technology literary, and cost barriers to accessing technology. Moreover, we lack access to participants’ demographic groups to comment on whether there would be demographic differences across databases.

Despite these limitations, the depiction of participants’ experiences in our study is consistent with previously published data.25

In balance, our study has several noteworthy strengths. This is the first study that focuses on the financial burden of diabetes care as discussed in OHCs. An advantage of analyzing online communication is that it is an easily accessible source for interactions between people of diverse backgrounds and social standings.26,27 The data are reportedly from individuals with diabetes or their caregivers, and thus the information is presented in a patient-friendly manner. The online data are also likely composed of honest experiences because creators can be anonymous. Similarly, strategies on overcoming barriers for care shared on forums were vetted by real-life experience. Additionally, we used artificial intelligence in a novel way to identify initial forum entries using natural language processing software, and triangulated the themes we identified with existing self-management theories, BoTF and TPC.19,21 This is the first time both frameworks have been used together in a qualitative study to analyze the burden of diabetes care, thus generating a fresh perspective on the issue.

Relationship to Other Literature

Our study found that participants described variability in health care costs across insurance companies, states, and countries, which have been previously characterized in the literature.28,29 Financial barriers were cited as a limitation to medications, diabetes supplies, and overall ability to complete treatment as prescribed.30 Similar to the existing literature, perceived financial burden and uninsured status were associated with blood glucose levels above and below guideline-suggested targets (glycated hemoglobin ≥8%) and decreased medication use.5,31

Our study also describes individual financial factors that affect diabetes care, such as income. Berkowitz et al32 described that 28% of people with diabetes experienced medication underuse, 11% expressed housing instability, and 14% had energy insecurity.

Our findings are supported by Moorhead et al,26 who reported that social media is an important health care communication tool for PLWDs to increase sociability and emotional support.

In a study examining US medical spending from 2006 to 2009,33 future-discounted lifetime medical expenditure was $124,600 higher for PLWDs at age 40 years compared with their peers despite diabetes being associated with lower life expectancy.34, 35, 36 Higher costs were associated with complications and comorbid conditions, such as blood glucose levels above or below guideline-suggested targets, amputations, or end-stage renal disease. In conjunction with our findings, this suggests that OHC support and strategies that improve glycemic control could result in not only improved health outcomes but also reduced health care spending.

Practice Implications

Though the Affordable Care Act has been shown to reduce health care–related financial burden for certain populations, including low- and middle-income families with children, many people still face significant financial burden.23 In addition, there have been recent efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, including new rules to decrease Medicaid financing and protections for people with pre-existing conditions.37 For now, the Affordable Care Act remains in place.

However, there have also been successful advocacy efforts across the country, as evidenced by the creation of state laws and policies that support affordable care plans and insurance coverage. A recent success of advocacy efforts was seen in Colorado, the first state to limit out-of-pocket costs to $100 per prescription per month.38 Around the same time, Minnesota passed the Alec Smith Emergency Insulin Act to provide eligible PLWDs with a 3-month supply of emergency insulin.39 This act was created in response to the death of a 26-year-old man who was underinsured, unable to cover out-of-pocket expenses, and as a consequence had to ration insulin.39 Even more recently, Eli Lilly and Sanofi implemented co-pay assistance programs so that insulin can be more affordable during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.37 However, there is still a need for advocacy because some of these changes are temporary and people across the country continue to struggle with the financial burden of their diabetes care.

Our findings highlight that OHCs are a source of information regarding PLWDs' struggles with the cost of diabetes care. However, they do not replace the need for cost conversations during clinical encounters.40 Instead, they highlight the critical necessity of cost conversation during clinical encounters to align treatment plans with PLWDs' financial capacity.41, 42, 43

Finally, our results imply that PLWDs benefit from sharing information in the online communities. Additional research should address how resource sharing and social support through OHCs could be further developed as a health care system strategy to improve experience and outcomes for PLWDs.

Conclusion

High cost for diabetes care generated barriers that negatively affected physical health and emotional states. Participant-shared experiences in OHCs increased capacity and resources to manage the burden. Future research to expand on the themes is needed. Potential solutions include cost-based shared decision-making tools and advocacy for policy change.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Christina LaVecchia, Anjali D. Thota, Paige W. Organick, and Gabriela Spencer Bonilla for input on the study design and contribution to the project. C.C.G. and N.R.E.S. are co-first authors.

Footnotes

Grant Support: This study was supported by the Cortese Family Innovation Award and the Gordon and Betty More Foundation Grant. Dr Boehmer’s time was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, grant K12HS026379, and the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant KL2TR002492. Additional support for Minnesota Learning Health System scholars is offered by the University of Minnesota Office of Academic Clinical Affairs and the Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, or Minnesota Learning Health System Mentored Career Development Program.

Potential Competing Interests: The authors report no competing interests.

Supplemental material can be found online at https://mcpiqojournal.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

Supplemental Online Material

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2020. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020. Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2017. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2017. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hua X., Carvalho N., Tew M., Huang E.S., Herman W.H., Clarke P. Expenditures and prices of antihyperglycemic medications in the United States: 2002-2013. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1400–1402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piette J.D., Heisler M., Wagner T.H. Cost-related medication underuse: do patients with chronic illnesses tell their doctors? JAMA Intern Med. 2004;164(16):1749–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.16.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piette J.D., Wagner T.H., Potter M.B., Schillinger D. Health insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of care. Med Care. 2004;42(2):102–109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108742.26446.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herkert D., Vijayakumar P., Luo J. Cost-related insulin underuse among patients with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):112–114. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawkins J.B., Brownstein J.S., Tuli G. Measuring patient-perceived quality of care in US hospitals using Twitter. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25(6):404–413. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gohil S., Vuik S., Darzi A. Sentiment analysis of health care tweets: review of the methods used. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2018;4(2):e43. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myslin M., Zhu S.H., Chapman W., Conway M. Using twitter to examine smoking behavior and perceptions of emerging tobacco products. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e174. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bychkov D., Young S. Social media as a tool to monitor adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Transl Res. 2018;3(suppl 3):407–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis M.A., Anthony D.L., Pauls S.D. Seeking and receiving social support on Facebook for surgery. Soc Sci Med. 2015;131:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Egan K.G., Israel J.S., Ghasemzadeh R., Afifi A.M. Evaluation of migraine surgery outcomes through social media. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(10):e1084. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman R.A., Viswanath K., Vaz-Luis I., Keating N.L. Learning from social media: utilizing advanced data extraction techniques to understand barriers to breast cancer treatment. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158(2):395–405. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3872-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bender J.L., Jimenez-Marroquin M.-C., Jadad A.R. Seeking support on facebook: a content analysis of breast cancer groups. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(1):e16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hong Y., Pena-Purcell N.C., Ory M.G. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: a systematic literature review. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(3):288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mikal J.P., Beckstrand M.J., Parks E. Online social support among breast cancer patients: longitudinal changes to Facebook use following breast cancer diagnosis and transition off therapy. J Cancer Survivorship. 2020;4(3):322–330. doi: 10.1007/s11764-019-00847-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V., Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(4):589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boehmer K.R., Gionfriddo M.R., Rodriguez-Gutierrez R. Patient capacity and constraints in the experience of chronic disease: a qualitative systematic review and thematic synthesis. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):127. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0525-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eton D.T., Ridgeway J.L., Egginton J.S. Finalizing a measurement framework for the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2015;6:117–126. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S78955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eton D.T., de Oliveira D.R., Egginton J.S. Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Outcome Meas. 2012;3:39–49. doi: 10.2147/PROM.S34681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. Judging the quality of case study reports. Int J Qual Studies Educ. 1990;3(1):53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wisk L.E., Peltz A., Galbraith A.A. Changes in health care–related financial burden for US families with children associated with the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(11):1032–1040. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marino M., Angier H., Fankhauser K. Disparities in biomarkers for patients with diabetes after the Affordable Care Act. Med Care. 2020;58(suppl 6 1):S31–S39. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000001257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayliss E.A., Steiner J.F., Fernald D.H., Crane L.A., Main D.S. Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(1):15–21. doi: 10.1370/afm.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moorhead S.A., Hazlett D.E., Harrison L., Carroll J.K., Irwin A., Hoving C. A new dimension of health care: systematic review of the uses, benefits, and limitations of social media for health communication. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(4):e85. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allen C., Vassilev I., Kennedy A., Rogers A. Long-term condition self-management support in online communities: a meta-synthesis of qualitative papers. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(3):e61. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron C.G., Bennett H.A. Cost-effectiveness of insulin analogues for diabetes mellitus. CMAJ. 2009;180(4):400–407. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Borah B.J., Darkow T., Bouchard J., Aagren M., Forma F., Alemayehu B. A comparison of insulin use, glycemic control, and health care costs with insulin detemir and insulin glargine in insulin-naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther. 2009;31(3):623–631. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edelman S., Pettus J. Challenges associated with insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2014;127(10 suppl):S11–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ngo-Metzger Q., Sorkin D.H., Billimek J., Greenfield S., Kaplan S.H. The effects of financial pressures on adherence and glucose control among racial/ethnically diverse patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(4):432–437. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1910-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berkowitz S.A., Meigs J.B., DeWalt D. Material need insecurities, control of diabetes mellitus, and use of health care resources: results of the Measuring Economic Insecurity in Diabetes study. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(2):257–265. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhuo X., Zhang P., Barker L., Albright A., Thompson T.J., Gregg E. The lifetime cost of diabetes and its implications for diabetes prevention. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(9):2557–2564. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li R., Bilik D., Brown M.B. Medical costs associated with type 2 diabetes complications and comorbidities. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(5):421–430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McBrien K.A., Manns B.J., Chui B. Health care costs in people with diabetes and their association with glycemic control and kidney function. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1172–1180. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shetty S., Secnik K., Oglesby A.K. Relationship of glycemic control to total diabetes-related costs for managed care health plan members with type 2 diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(7):559–564. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.7.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willison C.E., Singer P.M. Repealing the Affordable Care Act essential health benefits: threats and obstacles. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(8):1225. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.House Bill 19-1216. Reduce insulin prices. Concerning measures to reduce a patient's costs of prescription insulin drugs, and, in connection therewith, making an appropriation. Colorado General Assembly 1st Regular Sess (CO 2019).

- 39.HF3100. The Alec Smith Emergency Insulin Act. Office of the Revisor of Statutes: Conference Committee Report, 91st Legislature (MN 2019-2020).

- 40.Public Agenda Still Searching: How People Use Health Care Price Information in the United States, New York State, Florida, Texas and New Hampshire; 2017. https://www.publicagenda.org/reports/still-searching-how-people-use-health-care-price-information-in-the-united-states/

- 41.Alexander G.C., Casalino L.P., Meltzer D.O. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290(7):953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Irwin B., Kimmick G., Altomare I. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care. Oncologist. 2014;19(11):1135–1140. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmittdiel J.A., Steers N., Duru O.K. Patient-provider communication regarding drug costs in Medicare Part D beneficiaries with diabetes: a TRIAD Study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:164. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.