Abstract

Time-resolved fluorescence and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were used to examine how two amino acids, L-phenylalanine (L-PA) and N-acetyl-DL-tryptophan (NAT), affect the temperature-dependent membrane affinity of two structurally similar coumarin solutes for 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) vesicles. The 7-aminocoumarin solutes, coumarin 151 (C151) and coumarin 152 (C152), differ in their substitution at amine position—C151 is a primary amine, and C152 is a tertiary amine—and both solutes show different tendencies to associate with lipid bilayers consistent with differences in their respective log-P-values. Adding L-PA to the DPPC vesicle solution did not change C151’s propensity to remain freely solvated in aqueous solution, but C152 showed a greater tendency to partition into the hydrophobic bilayer interior at temperatures below DPPC’s gel-liquid crystalline transition temperature (Tgel-lc). This finding is consistent with L-PA’s ability to enhance membrane permeability by disrupting chain-chain interactions. Adding NAT to DPPC-vesicle-containing solutions changed C151 and C152 affinity for the DPPC membranes in unexpected ways. DSC data show that NAT interacts strongly with the lipid bilayer, lowering Tgel-lc by up to 2°C at concentrations of 10 mM. These effects disappear when either C151 or C152 is added to solution at concentrations below 10 μM, and Tgel-lc returns to a value consistent with unperturbed DPPC bilayers. Together with DSC results, fluorescence data imply that NAT promotes coumarin adsorption to the vesicle bilayer surface. NAT’s effects diminish above Tgel-lc and imply that unlike L-PA, NAT does not penetrate into the bilayer but instead remains adsorbed to the bilayer’s exterior. Taken in their entirety, these discoveries suggest that amino acids—and by inference, polypeptides and proteins—change solute affinity for lipid bilayers with specific effects that depend on individualized amino-acid-lipid-bilayer interactions.

Significance

Amino acids change solute affinity for lipid bilayers in unique and distinctive ways. Using data from time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry experiments, findings presented in this work point to different amino-acid-lipid-bilayer interaction mechanisms that, in turn, affect how solutes associate with lipid bilayers. Temperature-dependent fluorescence results demonstrate how these mechanisms affect not only the tendency of aqueous phase solutes to accumulate in lipid bilayers and on the bilayer surface but also how partitioned solutes change their distribution throughout the bilayer.

Introduction

Synthetic organic solutes have long been the subject of partitioning studies that seek to assess properties such as bioavailability, toxicity, and environmental persistence (1, 2, 3, 4). The most commonly cited measure of partitioning behavior is the log P (or log Ko/w) partitioning coefficient that describes solute affinity for an organic environment (1-octanol) relative to an aqueous environment. Despite being developed in the late 19th century as a predictor of anesthetic efficacy (5,6), log P continues to be used as a model describing solute accumulation in biological membranes (7) and serves one of five criteria in the Lipinski rule of five framework that guides pharmaceutical development (8,9).

Although log P remains a valuable predictive tool, more chemically informed models describing solute affinity for membranes continue to be developed. To account for charged solutes with various pKas, the log D scale was created and accounted for pH-dependent changes in solute charge (10, 11, 12). The liposome-water coefficient (log Klip/w) was developed to provide more accurate description of a solute’s membrane affinity by adding liposomes to an aqueous phase (13,14). The log Klip/w shares a parabolic relationship with the log P for lower molecular weight solutes, but this relationship breaks down for larger molecules because of the higher energies required to displace solutes within the membrane structure (2,13). Other studies have also shown that solute accumulation in membranes varies between lipid types, meaning that these equilibrium coefficients fail to capture “real” partitioning tendencies because biological cells contain a host of environments, including those created by storage lipids (fatty lipids) and the heterogeneous membrane bilayer (15). When anticipating solute accumulation in adipose tissue (composed primarily of storage lipids), olive oil is often used as a replacement for the octanol phase in the determination of the log P (now log Kolive oil/water) for storage lipids (15).

Although these modifications to log P are useful and provide a more realistic perspective into membrane partitioning tendencies, they are still limited in their capabilities. Common shortcomings include a limited ability to function correctly for larger solutes and an oversimplification of lipid membrane heterogeneity (1,16). In summary, log P and its derivatives are useful tools; however, they are unable to account for specific solute-solute and solute-membrane interactions that underlie all partitioning behaviors. In an effort to add complexity and improve the accuracy and predictive power of Klip/w, a number of studies have created lipid vesicles containing additional components such as cholesterol (17), surfactants (18), and proteins (19).

Recent work in our own laboratory demonstrated that time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy can determine the extent of solute accumulation in simple lipid vesicle bilayers and, more importantly, identify how solutes distribute themselves across the bilayer. Specifically, solutes having fluorescence lifetimes sensitive to local solvation environments can effectively report on whether solutes sample conditions attributed to either an aqueous buffer, a hydrophobic alkane-like environment, or surroundings that can be approximated as polar organic solvents. These studies illustrated how solute partitioning depends on bilayer phase (20) and composition (21) and also demonstrated that partitioning ratios could be quantified (22).

Our previous work in this area examined the temperature dependence of solute partitioning into single- or dual-component phospholipid bilayers. Understanding how the presence of additional biologically relevant species affects membrane properties is necessary for developing accurate descriptions of how solute affinity for lipid bilayers changes. The studies described below examine solute affinity for lipid bilayers in the presence of two amino acids, L-phenylalanine (L-PA) and N-acetyl-DL-tryptophan (NAT). Several reports have suggested that amino acids alter solute binding to lipid membranes and change membrane permeability to organic solutes (23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28). Complementing the body of experimental work have been computational studies that examined how amino acids and peptides associate with lipid membranes, the free energy changes involved with such associations, and the impact of peptide association on bilayer properties (29, 30, 31). Experimental findings particularly relevant to the studies described below reported that L-PA increased lipid bilayer permeability at L-PA concentrations of 5 and 20 mM (32). This study proposed that the increase in permeability was due to phenylalanine aggregates forming within the membrane. Other studies by Nandi et al. compared the effects of D-phenylalanine with L-PA on lipid bilayer vesicles and how the different enantiomers interact with the lipid membrane, concluding that an L-PA increases the lipid membrane fluidity and membrane permeability more than D-phenylalanine (33). Additionally, Kanwa et al. reported that amino acid formal charge affects how effectively the amino acid is accommodated into lipid membranes (34). Specifically, cationic amino acids fluidize the membrane, whereas anionic amino acids dehydrate the membrane. Given that these studies demonstrate that amino acids affect membrane permeability, we hypothesize that partitioning behavior and solute distributions in the lipid bilayers’ varied solvation environments will also change.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Structures of all five chemicals used in these experiments—coumarin 151 (C151), coumarin 152 (C152), L-PA, NAT, and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC)—are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of (a) coumarin 151 (C151), (b) coumarin 152 (C152), (c) N-acetyl-DL-tryptophan (NAT), (d) L-phenylalanine (L-PA), (e) and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) lipid. Number assignments refer to various environments created by lipid with the 1) nonpolar, hydrophobic hydrocarbon tail, 2) the polar glycerol-backbone and ester groups, and 3) the polar zwitterionic phosphate headgroup. The COOH pKa-values for NAT and L-PA are 3.6 and 2.2, respectively (ChemDraw Prime 19.0), giving local charges on structures at pH 7 used for these experiments.

Laser grade C151 and C152 were purchased from Exciton Technologies (Edmonton, Canada); L-PA and NAT were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA), respectively; and DPPC was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). All chemicals were used as received. Solutions were made in using MilliporeSigma water (18.2 MΩ; Burlington, MA) buffered to a pH of 7.0 with a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer (ionic strength = 10 mM). C151 and C152 concentrations in all solutions were kept constant at 6 μM. L-PA and NAT concentrations were kept constant at 10 mM. (Control experiments were performed with 20-mM PBS buffer solutions without amino acids to test whether a simple change in ionic strength might change C15X affinity for membranes. These experiments with higher PBS concentrations resulted in findings equivalent to those performed in a 10-mM PBS buffer (20), demonstrating that over this limited concentration range, solute affinity for DPPC bilayers is not sensitive to ionic strength. Data not shown.)

C151 and C152 have been extensively studied and have well-characterized photophysical properties (20, 21, 22,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40). In its neutral form, L-PA has a log P of −1.4, indicating it should remain in the aqueous environment. The pKa1 of the COOH group of L-PA is 2.2, and the pKb2 for the R-NH3+ 9.9 (calculated by ChemDraw Prime 19.0); this combination results in a zwitterionic form in the PBS (pH 7) buffer used in these experiments. Because a zwitterion L-PA has a (calculated) log P of 0.12, this implies a greater tendency to partition into the DPPC bilayer than in its neutral form. The other amino acid used in this study is NAT. In its neutral form, NAT has a log-P-value of 1.1, indicating its affinity for the organic medium; however, under experimental conditions (pH 7.0), NAT is also zwitterionic, and its log-P-value diminishes to 0.34.

Lipid bilayer preparation

Lipid bilayer vesicles were prepared by dissolving DPPC in chloroform. The solvent was then removed via rotary evaporation. The resulting thin lipid film was subsequently rehydrated using a 6-μM coumarin and 10-mM amino acid solution in 10 mM PBS (pH 7) to form a lipid vesicle solution. The solution was sonicated for 30 min at ∼50°C. The solution temperature was then maintained at 50°C as the solution was passed through an Avanti Mini Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids) 10 times with a membrane pore size of 200 nm (21,22,35,36). Fluorescence experiments were made with 1.5-mM DPPC vesicle solutions, and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) experiments used 20 mM DPPC vesicle solutions.

DSC

DSC measurements were done using a TA Instruments Discovery Q2000 DSC (Hüllhorst, Germany). Vesicle solutions were made using the method described above with concentrations of 20-mM DPPC vesicles and rehydrated with 10-mM PBS buffer (pH 7) for pure DPPC vesicles. For C15X-AA-doped DPPC vesicles, a 6 μM coumarin solution with 10-mM amino acid solution in a 10-mM PBS buffer was used to rehydrate vesicles. The vesicles made for DSC experiments were not filtered to size select vesicles. For experiments, Tzero pans and Tzero hermetic lids from TA Instruments were used and equilibrated at 20°C and heated 1°C/min to 55°C to capture the gel-liquid crystalline transition temperature (Tgel-lc).

Time-correlated single-photon counting

Fluorescence lifetimes were measured after coumarin excitation by a Ti-sapphire oscillator (Coherent Chameleon, 80 MHz, 85-fs pulse duration, 60–1040-nm wavelength range; Santa Carla, CA) coupled with an APE autotracker harmonic generator (Berlin, Germany) used to a frequency double the fundamental wavelength. A Conoptics model 350-10 modulator (Danbury, CT) was used to reduce the repetition rate to 4 MHz. Picoquant PicoHarp 300 and FluoTime 200 software were used for data collection. Samples were equilibrated at reported temperatures for 5 min using a Quantum Northwest TC125 temperature controller (Seattle, WA); longer equilibration times led to no discernable change in emission traces. Excitation wavelengths were unique to each solute in individual bulk solvents. For experiments carried out with vesicle-containing solutions, excitation wavelengths were chosen that overlapped coumarin absorption in all bulk solvents. Adding amino acids did not change the C15X steady-state excitation-emission spectra in the different bulk solvents. Changes to C15X emission lifetimes, when they were observed, were modest, and discussed in the relevant sections below. Additional details about experimental procedures and assemblies can be found in (20, 21, 22,35,36,40,41).

Time-resolved emission data from vesicle-containing solutions are fitted with a linear combination of independent lifetimes and amplitudes using fitting parameters that are adjusted to minimize residuals and optimize χ2. The resulting lifetimes are then compared with solute lifetimes in different bulk solvents that were chosen to mimic local solvation environments within the lipid bilayer. The fluorescence decay and amplitude expression are shown in Eq. 1, where Ai and τi are the amplitude and lifetime of the ith component, respectively (42).

| (1) |

Each equation was fitted independently, without any constraints, for the lifetimes and amplitudes with a typical χ2 between 0.90 and 1.10 when accounting for at most three lifetimes. Typically, uncertainties in lifetimes and amplitudes were 0.2 ns and 0.04, respectively. Reported data represent the averaged results from at least four to five experiments with independently prepared, equivalent samples. Lifetime uncertainties are reported as ±0.2 ns because of the time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) instrument response function; however, the error bars presented in this work are the result of four to five trials averaged together with deviations reported for an average of those trials. The average lifetimes and amplitudes and their respective standard deviations are reported for each specific temperature.

Results and discussion

L-PA results and discussion

Structural changes in the lipid bilayer can be inferred from changes in Tgel-lc as a function of L-PA concentration. L-PA’s reported ability to increase bilayer permeability (32) implies weaker intermolecular forces between the bilayer’s acyl chains, a hypothesis borne out by the small but measurable shift in Tgel-lc from 41.0 to 40.5°C (Fig. 2). The effect of L-PA concentration on the DPPC Tgel-lc is shown as found in Fig. S1. The DSC endothermic peak remains at 40.5°C as the concentration of L-PA increases. Adding C151 to the phenylalanine-containing vesicle solution does not further alter Tgel-lc, but the addition of C152 to the solution results in significant changes the DSC behavior. Specifically, the endotherm peak diminishes in intensity and broadens considerably. Such behavior indicates synergistic effects in which the two solutes—L-PA and C152—disrupt cohesive forces between the DPPC acyl chains (43).

Figure 2.

DSC trace of pure DPPC, 10 mM L-PA in DPPC, C151 with 10 mM L-PA in DPPC, and C152 with 10 mM L-PA in DPPC. Each trace is endothermic and offset for ease of viewing. To see this figure in color, go online.

If C152 partitioning into the DPPC bilayer is enhanced by L-PA, as implied by the DSC results, the next question to resolve is where within the bilayer does C152 accumulate? C152’s log-P-value of 2.2 predicts that partitioning into membranes should be favored. Previous work used C152’s time-dependent fluorescence emission to assess its local solvation environment in lipid bilayers based on its behavior in bulk solvation environments (20,35). In polar protic environments, C152 is believed to form a twisted intramolecular charge transfer (ICT) state and has a correspondingly short (≤1 ns) lifetime (38). In polar aprotic environments, this lifetime lengthens to ∼2 ns and in nonpolar, alkane environments, C152 emission is dominated by a relatively long ∼4-ns lifetime. In all organic solvents, C152 fluorescence decay is well described by single exponential kinetics. In aqueous solution, C152 emission is dominated by a short (sub-nanosecond) component with a longer lifetime (∼3.6 ns) contributing to <20% of the decay trace intensity. C151’s time-resolved emission behavior is also well characterized by a 4.51-ns lifetime in PBS buffer; a 5.25-ns lifetime in both methanol and acetonitrile; and biexponential decay with shorter lifetimes (1.21 ns (65%) and 3.27 ns (35%)) in alkanes (20).

Given findings from the DSC experiments, we assumed that adding L-PA to vesicle-containing solutions did not change C151 partitioning into DPPC bilayers but did change C152’s partitioning behavior. The assumption regarding C151 behavior was borne out by time-resolved fluorescence measurements described below. To assess C152 partitioning into DPPC bilayers infiltrated with L-PA, we first measured the time-resolved emission from C152 in methanol, acetonitrile, and cyclohexane. These solvents were chosen to represent the different solvation environments C152 might encounter across the DPPC bilayer. All solvents contained 10 mM L-PA, although the L-PA concentration in cyclohexane was likely smaller because of solubility constraints. Data from these studies are reported in Table 1 for C152 (and C151) in solutions of cyclohexane (nonpolar), acetonitrile (polar aprotic), methanol (polar protic), and the PBS buffer (pH 7). Bulk solvent fluorescence decay traces can be found in the Fig. S2. In the event of a biexponential fluorescence decay resulting in two lifetimes, the lifetime with the highest amplitude was used as representative for that environment. Including minority lifetimes (and amplitudes) for a given solvent did not improve fitting accuracy by statistically significant amounts. The fluorescence lifetimes of C151 and C152 with L-PA in each of the bulk solvents were taken as a function of temperature and decreased by less than 0.3 ns in all solvents as temperature increased from 10 to 60°C (Tables S1 and S2, respectively). In every instance, the lifetimes were virtually unchanged from those of the C15X solutes alone in the respective solvents. L-PA does, however, appear to change the relative amplitudes in cases in which fluorescence emission is biexponential, particularly for C151 in cyclohexane.

Table 1.

Fluorescent lifetimes (in nanoseconds) of C151-L-PA and C152-L-PA in bulk solvents

| Solvent | C151-L-PA τf (ns) | C152-L-PA τf (ns) |

|---|---|---|

| PBS buffer | 4.58 | 0.60 (0.81) |

| 3.77 (0.19) | ||

| Methanol | 5.24 | 1.04 |

| Acetonitrile | 5.37 | 2.16 |

| Cyclohexane | 1.12 (0.24) | 3.98 |

| 3.80 (0.76) |

The numbers reported in parenthesis are the respective amplitudes of the reported lifetimes. The fluorescent lifetimes reported were measured at 10°C.

To examine how L-PA affects C151 and C152 partitioning into DPPC lipid bilayers, both solutes were introduced (separately) to DPPC vesicle solutions containing 10 mM L-PA, and each coumarin’s time-resolved emission was measured as a function of temperature over a range from 10 to 60°C. To determine whether effects were reversible, spectra were collected as the temperature was increased and then decreased. As mentioned in the experimental section, each emission trace was fitted independently with a minimal number of lifetimes leading to a χ2 between 0.9 and 1.1. The fluorescence lifetimes of C15X-L-PA in DPPC lipid bilayers at each temperature were then compared with the lifetimes found in bulk solvents to infer the local solvation environment surrounding the solute. Each respective amplitude was a radiative rate corrected using the fluorescence quantum yield of pure C15X in the respective environment. The results of C15X-L-PA in DPPC lipid vesicles can be seen in Fig. 3 with the results of the fitting seen in Table 2.

Figure 3.

TCSPC spectra of C151-L-PA in DPPC (top) and C152-LP In DPPC (bottom) as a function of temperature. Each trace was fitted using Eq. 1 and are reported in Table 2. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

Fluorescence lifetimes (in nanoseconds) of C15X-L-PA in DPPC respective amplitudes (in parentheses) from 10 to 60°C and back

| C151-L-PA |

C152-L-PA |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| temp. (°C) | Buffer τ1 | Buffer τ1 (A1) | Polar τ2 (A2) | Nonpolar τ3 (A3) |

| 10 | 4.90 | 0.55 (0.54) | 1.44 (0.20) | 4.21 (0.26) |

| 20 | 4.87 | 0.43 (0.51) | 1.45 (0.30) | 4.10 (0.19) |

| 30 | 4.81 | 0.35 (0.50) | 1.41 (0.37) | 4.10 (0.13) |

| 36 | 4.85 | 0.32 (0.42) | 1.35 (0.48) | 4.34 (0.10) |

| 42 | 4.97 | 0.29 (0.29) | 1.28 (0.64) | 4.56 (0.07) |

| 50 | 5.02 | 0.18 (0.17) | 0.98 (0.78) | 5.10 (0.05) |

| 60 | 4.90 | 0.17 (0.21) | 0.77 (0.74) | 5.02 (0.05) |

| 50 | 5.04 | 0.17 (0.17) | 0.97 (0.78) | 5.01 (0.05) |

| 42 | 5.07 | 0.26 (0.24) | 1.25 (0.69) | 4.40 (0.07) |

| 36 | 4.89 | 0.31 (0.40) | 1.32 (0.50) | 4.25 (0.10) |

| 30 | 4.87 | 0.34 (0.44) | 1.41 (0.44) | 4.14 (0.12) |

| 20 | 4.85 | 0.41 (0.47) | 1.53 (0.35) | 4.16 (0.18) |

| 10 | 4.90 | 0.53 (0.51) | 1.45 (0.23) | 4.27 (0.26) |

Amplitudes have been corrected for their respective radiative rates. Lifetime uncertainties are ±0.2 ns; amplitude uncertainties are ±0.04.

Fig. 3 and Table 2 show that C151 fluorescence decay traces in L-PA-DPPC solutions can be fitted to a single lifetime that matches that of C151-L-PA in PBS buffer. This result demonstrates that C151-L-PA does not partition into the lipid vesicles, similar to this solute’s behavior in the absence of L-PA (20). This finding also reinforces conclusions from DSC experiments showing that adding C151 to an L-PA-DPPC solution did not further change the bilayer’s gel-liquid crystalline transition.

C152 lifetimes identified for L-PA-DPPC solutions are very similar to those measured for C152 in DPPC solutions in the absence of L-PA. The emission decay data in Fig. 3 are best fitted to three unique lifetimes. The short, sub-nanosecond lifetime corresponds to C152-L-PA in PBS buffer, indicating that some C152 remains in the aqueous solution and does not associate with the DPPC vesicles. The intermediate lifetime at temperatures below Tgel-lc falls between the polar aprotic (2.16 ns in acetonitrile) and polar protic (1.04 ns in methanol) limits but clearly indicates a C152 population sampling a local environment having an appreciable static dielectric constant. Above Tgel-lc, this intermediate lifetime closely matches C152’s lifetime in methanol, indicating a polar protic solvation environment. Although we cannot definitively assign C152’s intermediate lifetime at low temperatures to specific solvation forces, above Tgel-lc C152 in the polar headgroup region behaves as if it is associating solvating water molecules in the glycerol backbone region of the DPPC bilayer. This phenomenon has been reported before and is attributed to bilayer hydration above Tgel-lc (20,35). Lastly, the long lifetime most closely matches that of C152-L-PA in cyclohexane, implying a portion of the C152 solute molecules are fully solvated within the acyl chain region of the lipid bilayer. Data reported in Table 2 are illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

C152 fluorescence lifetimes (top) in L-PA-DPPC solutions and the respective radiative rate corrected lifetime contributions (bottom). The three lifetimes are assigned to C152 in PBS buffer (τ1, red circles), DPPC’s polar headgroup region (τ2, green squares), and DPPC’s nonpolar interior (τ3, blue triangles). The dashed lines indicate the Tgel-lc of DPPC bilayer at ∼41.5°C. Each point is an average of five independent trials, and the respective error bars on each point indicate an uncertainty of one standard deviation based on the results from those five trials. In some instances, the uncertainty is smaller than the marker used to represent that data point. To see this figure in color, go online.

Although the lifetimes for C152 partitioning into DPPC bilayers are very similar, regardless of whether or not L-PA is present, the contributions of these lifetimes to the C152 emission traces are measurably different between the two systems. In the absence of L-PA and at the lowest temperature sampled (10°C), the distribution of C152 between aqueous/polar/interior environments is ∼0.40:0.40:0.20, in which polar refers to the polar, glycerol backbone region of the bilayer, and interior refers to the nonpolar acyl chain region of the bilayer. When L-PA is present, this aqueous/polar/interior balance changes to 0.55:0.20:0.25. In other words, adding L-PA depletes C152 in the polar headgroup region, pushing more C152 back into aqueous buffer and some into the bilayer’s hydrophobic interior. If the bilayer is infiltrated by L-PA and L-PA not only disrupts chain-chain interactions but is better solvated than C152 in the polar headgroup region, then L-PA would afford C152 easier access to the membrane’s low polarity region for the hydrophobic C152. Furthermore, L-PA might also occupy “sites” in the polar headgroup region that are then no longer able to accommodate C152, thereby increasing C152’s concentration in aqueous solution. This latter assertion is speculative but does raise questions about bioconcentration mechanisms and the nature of solute solvation in biological membranes.

At the highest temperatures sampled, 50 and 60°C, the fraction of C152 in the polar headgroup region reaches ∼75–80%, with the polar region showing strong evidence of hydration above Tgel-lc. At these elevated temperatures, the C152 fraction in the nonpolar region falls to almost zero, and the C152 fraction in aqueous solution drops to ∼20%. This gradual increase of C152 in the bilayer’s polar headgroup region stands in contrast with the more abrupt uptake of C152 shown by DPPC bilayers in the absence of L-PA (20). The data in Fig. 4 are consistent with the DSC results that show how L-PA and C152 synergistically suppress and broaden the DPPC bilayer’s Tgel-lc. The fact that L-PA affects C152 partitioning but has no effect on C151 affinity for DPPC bilayers implies that this amino acid will only influence partitioning for those solutes that already have a tendency to accumulate in bilayers. As will be noted below, these observations have direct consequences for predicting how L-PA associates with DPPC bilayers.

NAT results and discussion

Given how L-PA affects C152 partitioning into membranes, we sought to determine if these findings were general for amino acids. In that context, we employed the same techniques to determine how NAT influences C151 and C152 partitioning into DPPC lipid bilayers containing 10 mM NAT.

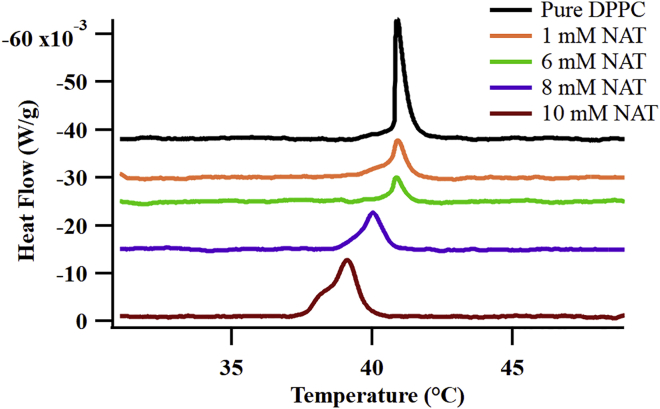

NAT’s effects on DPPC’s properties are evident in concentration-dependent DSC experiments. Fig. 5 reports DSC endotherms of DPPC vesicle solutions over a range of NAT concentrations. At concentrations above 6 mM, NAT causes DPPC’s Tgel-lc to shift to lower temperatures and develop an additional low temperature shoulder. These effects are much more pronounced than any observed with L-PA, indicating that NAT associates more strongly with the DPPC bilayer.

Figure 5.

DSC spectra of 20 mM DPPC vesicles rehydrated with pure PBS buffer as well as 1, 6, 8, and 10 mM NAT in PBS buffer. Each trace is endothermic and offset for ease of viewing. To see this figure in color, go online.

The DSC data show that at low NAT concentrations, Tgel-lc of the NAT-DPPC systems remains virtually unchanged from that of pure DPPC. As NAT concentration increases from 6 to 10 mM, the primary feature in the isotherm shifts from 41 to 39°C, a change much larger than the −0.5°C shift induced by 10 mM L-PA. In addition to the shift to lower temperatures, NAT induces a low temperature shoulder to the endotherm, suggesting that a second mechanism may also be affecting the gel-liquid crystalline lipid bilayer phase transition. Earlier work studying saccharide adsorption to lipid films attributed a high temperature shoulder to dehydration of the lipid bilayer headgroups, allowing stronger coulomb interactions to further stabilize the bilayer’s gel phase (44,45). A low temperature shoulder may signify disruption of acyl chain interactions. Alternatively, this observation may also hint at more direct NAT-choline headgroup interactions that weakens coulomb attractions between headgroups in a way that also disrupts the gel-liquid crystalline phase transition (46).

Similar to the L-PA-DPPC experiments, PBS buffer solutions (pH 7) containing 6 μM coumarin and 10 mM NAT were used to rehydrate 20 mM DPPC vesicles that were then analyzed using DSC (Fig. 6). As noted in Fig. 5, NAT by itself at concentrations ≥6 mM significantly perturbs Tgel-lc. However, in NAT-DPPC solutions, both coumarins cause Tgel-lc to shift back to higher temperatures (40.4°C). The DSC endotherm peak also sharpens and intensifies for C151-NAT-DPPC and C152-NAT-DPPC solutions, implying that the coumarin solutes, despite their 1000-fold smaller concentration (6 μM C15X vs. 10 mM NAT) offset the disruptive effect(s) that NAT has on the DPPC bilayer cohesion (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

DSC spectra of 20 mM DPPC vesicles rehydrated with pure PBS buffer, 10 mM NAT in PBS buffer, and 6 μM C151 and C152 with 10 mM NAT in PBS buffer. Each trace is endothermic and offset for ease of viewing. To see this figure in color, go online.

Time-resolved emission data provide insight into the unusual and surprising DSC results. Table 3 reports the fluorescence lifetimes of C151 and C152 in the model solvents containing NAT, and the respective decay traces of C15X-NAT in each of the model solvents can be found in Fig. S3. The lifetimes of C151-NAT and C152-NAT in each bulk solvent were also measured as a function of temperature, and these data can be found in Tables S3 and S4, respectively, of the Supporting materials and methods. The lifetimes of C15X-NAT as a function of temperature changed little with the exception of C151-NAT in cyclohexane. In that system, C151’s emission lifetime increased from 4.20 ns (in the NAT containing solutions) to 4.83 ns (in the solutions without NAT).

Table 3.

Fluorescent lifetimes (in nanoseconds) of C151-NAT and C152-NAT in bulk solvents

| Solvent | C151-NAT τf (ns) | C152-NAT τf (ns) |

|---|---|---|

| PBS buffer | 4.04 | 0.58 (0.77) |

| 3.36 (0.23) | ||

| Methanol | 4.36 | 1.08 |

| Acetonitrile | 4.24 | 1.98 |

| Cyclohexane | 4.20 (0.79) | 3.70 |

| 0.78 (0.21) |

The numbers reported in parenthesis are the respective amplitudes of the reported lifetimes. The fluorescent lifetimes reported were measured at 10°C.

NAT changed C151 lifetimes measurably in the different solvents, implying specific C151-NAT interactions. In particular, C151’s PBS buffer lifetime shortens from 4.51 to 4.04 ns, and the decay lifetimes in both methanol and acetonitrile shorten by ∼1 ns (from ∼5.3 to ∼4.3 ns). In cyclohexane, C151 continues to show biexponential decay, but the amplitudes switch. In the absence of NAT, C151 emission in cyclohexane is dominated by the shorter lifetime (τ1 = 1.21 ns, A1 = 0.65; τ2 = 3.27 ns, A2 = 0.35). In a cyclohexane solution that contains NAT, the longer lifetime component (τ1 = 4.20 ns) dominates (A1 = 0.79) over the shorter component (τ2 = 0.78 ns, A2 = 0.21). In contrast to C151 behavior in NAT-free solvents, the results in Table 3 indicate significant solute-solute interactions. In particular, these results imply that in nonpolar solvents, NAT stabilizes C151’s planar charge transfer excited state. In contrast to C151, C152’s emission behavior in bulk solvents containing 10 mM NAT differ little from behavior in the solvents by themselves, implying much weaker solute-solute interactions.

After characterizing the time-resolved emission of C15X-NAT in the model solvents (Fig. S3; Tables S3 and S4), a PBS buffered solution of 6 μM C15X and 10 mM NAT was used to prepare DPPC vesicles. These systems were studied as a function of temperature using time-resolved fluorescence (Fig. 7). The resulting decay traces were fitted using Eq. 1. Once determined, the lifetimes of C151 and C152 in the NAT-DPPC solutions were compared with the lifetimes of C15X-NAT in bulk solvents to determine each solute’s solvation environments. Amplitudes were radiative rate corrected using the radiative rates of pure C15X in each bulk solvent. Results of this analysis of C15X in NAT-DPPC solutions are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 7.

TCSPC spectra of C151-NAT in DPPC (top) and C152-NAT in DPPC (bottom) as a function of temperature. Each trace was fitted using Eq. 1 and are reported in Table 4. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 4.

Fluorescence lifetimes (in nanoseconds) of C15X-NAT in DPPC respective amplitudes (in parentheses) from 10 to 60°C and back down to 10°C

| C151-NAT |

C152-NAT |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| temp. (°C) | Buffer τ1 (A1) | Complex τ2 (A2) | Buffer τ1 (A1) | Polar τ2 (A2) | Nonpolar τ3 (A3) |

| 10 | 4.12 (0.89) | 0.63 (0.11) | 0.52 (0.63) | 1.63 (0.22) | 4.16 (0.15) |

| 20 | 3.98 (0.90) | 0.66 (0.10) | 0.43 (0.60) | 1.42 (0.28) | 3.90 (0.12) |

| 30 | 3.87 (0.89) | 0.72 (0.11) | 0.39 (0.57) | 1.51 (0.35) | 3.69 (0.08) |

| 36 | 3.84 (0.88) | 0.77 (0.12) | 0.36 (0.53) | 1.42 (0.40) | 3.62 (0.07) |

| 42 | 4.06 (0.85) | 0.70 (0.15) | 0.34 (0.22) | 1.27 (0.74) | 3.72 (0.04) |

| 50 | 3.90 (0.86) | 0.78 (0.14) | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.98 (0.75) | 3.86 (0.04) |

| 60 | 3.66 (0.87) | 0.73 (0.13) | 0.21 (0.23) | 0.76 (0.73) | 3.48 (0.04) |

| 50 | 3.86 (0.86) | 0.70 (0.14) | 0.23 (0.21) | 0.97 (0.75) | 3.58 (0.04) |

| 42 | 4.07 (0.85) | 0.75 (0.15) | 0.29 (0.21) | 1.22 (0.75) | 3.75 (0.05) |

| 36 | 3.82 (0.88) | 0.76 (0.12) | 0.34 (0.52) | 1.38 (0.41) | 3.67 (0.08) |

| 30 | 3.88 (0.89) | 0.77 (0.11) | 0.38 (0.54) | 1.47 (0.37) | 3.75 (0.09) |

| 20 | 4.02 (0.88) | 0.72 (0.12) | 0.41 (0.55) | 1.45 (0.32) | 3.88 (0.13) |

| 10 | 4.14 (0.88) | 0.65 (0.12) | 0.45 (0.52) | 1.41 (0.31) | 4.14 (0.17) |

Amplitudes have been corrected for their respective radiative rates. Lifetime uncertainties are ±0.2 ns; amplitude uncertainties are ±0.04.

The first observation that stands out is that C151 emission in NAT-DPPC solutions requires two emission lifetimes, not a single lifetime, as was the case for C151 in DPPC and L-PA-DPPC solution (and in the buffer solution by itself). Specifically, C151 emission in the NAT-DPPC solutions contains a measurable (∼15%) contribution from a short-lived, ∼0.70-ns component. This lifetime is absent in C151-NAT solutions in any bulk solvent. C151’s photophysical behavior attributes short lifetimes to its inability to form a stable, planar ICT state (37). ICT formation is favored in polar solvents—both protic and aprotic—and diminished in nonpolar solvents in which excited state C151 is believed to retain sp3 hybridization about the amine. The short lifetime observed in the C151-NAT-DPPC systems implies that a subset of the solvated C151 samples a local environment where it is conformationally restricted, and photoexcitation does not lead to ICT formation. Similar behavior has been reported for C151 adsorbed to silica-methanol interfaces where hydrogen bonding between adsorbed C151 and silica’s surface silanol groups coupled with surface induced changes in solvent organization introduce a short emission lifetime (∼1.2 ns) to what should otherwise be a single exponential decay with a lifetime of ∼5.3 ns (40).

Two other observations from the C15X-NAT-DPPC systems stand out. First, in addition to the short C151 lifetime noted above, the decay spectra of C152-NAT-DPPC show evidence of three unique lifetimes that are temperature dependent: a short (∼0.4 ns) lifetime corresponding to that of C152-NAT solvated in the PBS buffer, an intermediate (1.6 ns) lifetime below Tgel-lc that is similar to C152-NAT in acetonitrile, and a long (4 ns) lifetime that corresponds to that of the C152-NAT pairing solvated in cyclohexane. All three lifetimes grow shorter at higher temperatures, and above Tgel-lc, the intermediate lifetime changes from a polar aprotic to a polar protic limit. Fig. 8 summarizes these two observations by plotting the temperature-dependent lifetimes of C15X-NAT in DPPC vesicles; overlaid on these data are dashed lines to indicate the dominant lifetimes of C152 in the four bulk model solvents containing 10 mM NAT. The respective lifetime contributions for the lifetimes found in Fig. 9 and Table 4.

Figure 8.

Fluorescence lifetimes of C151-NAT (top) in DPPC and C152-NAT in DPPC (bottom). The three lifetimes in the C152 traces are assigned to C152 in the PBS buffer (τ1, red circles), polar headgroup region (τ2, green squares), and nonpolar bilayer interior (τ3, blue triangles). The horizontal dashed lines represent the dominant lifetime of C15X-NAT in bulk solvents for comparison. The vertical dashed lines note Tgel-lc of DPPC bilayer at ∼41.5°C. Each point is an average of four trials and the respective error bars on each point indicate one standard deviation of uncertainty from the four trials. In some cases, the uncertainty is smaller than the marker used to represent that data point. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 9.

Radiative rate corrected lifetime contributions of C15X-NAT in DPPC. The lifetime contributions seen here correlate with the lifetimes reported in Fig. 8 with C151 sampling two distinct environments and C152 sampling three environments in the DPPC-NAT solutions. For C151, the short lifetime contributions (pink diamonds) cannot be represented by C151 behavior in any bulk solvent (containing NAT) (Table 3). For C152, the three environments are assigned to C152 in the PBS buffer (τ1, red circles), the polar headgroup region (τ2, green squares), and the nonpolar bilayer interior (τ3, blue triangles). The dashed lines indicate the Tgel-lc at ∼41.5°C. Each point is an average of four trials, and the error bars on each point are one standard deviation of the four trials. To see this figure in color, go online.

The lifetime contributions determined for the C151 in NAT-DPPC system change very little as a function of temperature. In contrast, C152’s behavior shows a strong temperature dependence with a large increase in the intermediate lifetime’s contribution, assigned to C152 solvated in the polar backbone region, in the vicinity of DPPC’s Tgel-lc. Similar behavior has been observed previously and was assigned to C152 moving into the polar part of a lipid bilayer as the bilayer melted and was able to accommodate more solutes in its interior (20,22,35).

Given these findings, three unexpected behaviors must be addressed:

-

1)

The effects of C151 and C152 on DPPC’s phase transition in the presence of NAT.

-

2)

The origin of C151’s second emission decay lifetime in NAT-DPPC solutions.

-

3)

C152’s abrupt uptake into DPPC bilayers in the vicinity of Tgel-lc when NAT is present in contrast to the more gradual temperature-dependent partitioning behavior observed in L-PA-DPPC solutions.

Each issue is addressed below, and together, these explanations lead to a description of NAT associating strongly with DPPC’s charged headgroups in a way that affects bilayer properties and solute (C151 and C152) accumulation mechanisms.

The effect of C15X on DPPC’s phase transition in the presence of NAT

The DSC results in Fig. 5 show a clear trend in DPPC’s Tgel-lc as a function of NAT concentration: as NAT concentration rises, Tgel-lc shifts to lower temperatures and develops an even lower temperature shoulder. With 10 mM NAT in solution, DPPC’s main transition temperature is 2.5°C lower than in the PBS buffer alone. Fig. 6 shows that with 6 μM coumarin also in the NAT-DPPC solution, Tgel-lc is virtually indistinguishable from solutions containing pure DPPC vesicles (40.4°C (coumarin-NAT-DPPC) vs. 40.5°C (DPPC)). This behavior contrasts with that of L-PA, in which a 10-mM L-PA concentration leads to a very modest but reproducible −0.5°C shift in Tgel-lc. Both L-PA and NAT are zwitterionic with a net charge of zero; however, NAT is slightly more hydrophobic (log P = 0.34 vs. 0.12 for L-PA) and has more hydrogen bonding opportunities. Whereas L-PA is predicted to migrate into the bilayer, possibly aggregating in the hydrophobic interior (32), we propose that NAT associates primarily with DPPC’s charged headgroups.

DSC and time-resolved emission data also show that C151 does not associate with DPPC bilayers in the absence of NAT (nor with DPPC bilayers in the presence of L-PA). In order for the DSC endotherm in an NAT-DPPC (10 mM) solution to “snap back” to its original temperature and shape with the addition of C151 (and C152), we propose that membrane destabilization by NAT results from a weakening of headgroup-headgroup interactions through direct, coulomb interactions between the zwitterionic NAT and the zwitterionic DPPC headgroup. However, we maintain that these NAT adsorbates remain on the surface of the bilayer (perhaps with the aromatic rings penetrating into the glycerol backbone region) and afford opportunities for either the C151 or C152 to hydrogen bond directly with this surface complex, weakening the NAT-DPPC association enough for the bilayer to recover its original phase stability. If C151 (or C152)-NAT association was strong enough for the complex to dissociate from the membrane surface, we would expect the >1000:1 NAT/C15X ratio to result in no change in DPPC’s DSC behavior relative to solutions containing only 10 mM NAT and the DPPC vesicles. Furthermore, if the NAT partitioned into the bilayer interior, as is presumed to be the case for L-PA, we would not expect C151 to associate with the membrane at all, and Tgel-lc would remain unchanged from the C151-free NAT-DPPC solutions.

C151’s second lifetime in NAT-DPPC solutions

Fitting C151 time-resolved fluorescence emission in NAT-DPPC solutions requires two lifetimes, one long (τ1 ∼4.0 ns) assigned to C151 remaining in PBS buffer and one short (τ2 ∼0.7 ns) that does not correspond to C151 in any of the bulk solvents containing NAT. The relative contributions from these two lifetimes (∼85% for τ1 and 15% for τ2) change little over the temperature range sampled. The shorter lifetime is consistent with C151 solvated in nonpolar solvents or in confinement in which a long-lived ICT state cannot be stabilized (37,40). The insensitivity of τ2 (and A2) to membrane phase implies that these short-lived C151 species are not affected by the bilayer’s backbone and acyl chain organization. This observed behavior is consistent with independent C151-NAT-choline headgroup complexes that remain intact from 10 to 60°C.

An abrupt uptake of C152 into the bilayer in the vicinity of the Tgel-lc

Comparing the lower panels of Figs. 4 and 9 is instructive. Both show the temperature-dependent changes in amplitude associated with C152 solvated in DPPC’s polar headgroup region. The lifetimes of these amplitudes change from a value close to the polar aprotic limit at lower temperatures to a polar protic limit at temperatures above Tgel-lc, implying that above the transition temperature, C152 in the headgroup region can accept hydrogen bonds from putative H2O that has hydrated the membrane. In both L-PA-DPPC and NAT-DPPC solutions, C152 shows a greater affinity for the polar region of the membrane than the surrounding aqueous solution. However, in the L-PA-DPPC solutions, C152 concentration increases almost monotonically as the solution passes through Tgel-lc (Fig. 4), whereas in NAT-DPPC solutions, C152 concentration increases abruptly near Tgel-lc.

As noted earlier, results from the L-PA-DPPC solution can be explained by a mechanism in which L-PA penetrates into the lipid bilayer, disrupting chain-chain interactions and enabling C152 accumulation. As the temperature rises, this disruption becomes more pronounced and allows increasing amounts of C152 to be absorbed by the bilayer (both from the hydrophobic part of the bilayer and from the bulk buffer). This result is consistent with the DSC data that show Tgel-lc becoming broader and less pronounced when L-PA and C152 are both present in a DPPC vesicle solution (Fig. 2).

In the case of NAT-DPPC, however, C152 accumulation into the bilayer changes little below Tgel-lc and then rises abruptly at temperatures above Tgel-lc. DSC data show that Tgel-lc in this system is sharp and narrow. If the NAT had penetrated into the DPPC bilayer, we would expect that the bilayer would accommodate increasing amounts of C152 as the temperature rose and that the C152 in the bilayer would sample a lifetime similar to that in L-PA-DPPC systems. The data in Figs. 8 and 9 do not support this picture. Instead, C152’s behavior can be understood and reconciled with items 1 and 2 above if NAT is bound to the DPPC headgroups and effectively blocks C152 partitioning into the bilayer. Only after the bilayer melts and the vesicle expands does C152 have the access to begin accumulating in the membrane’s polar backbone region. Compared with the 33% increase of C152 into the DPPC backbone region when L-PA is present, and the bilayer melts (A2 changing from 0.48 to 0.64), bilayer melting in the presence of NAT increases A2 by 75% (A2 changing from 0.40 to 0.70). This difference in percentage increase further emphasizes the different effects that different amino acids have on solute accumulation in biological membranes.

Conclusions

Results presented in this work examined how two amino acids, L-PA and NAT, affect partitioning of two coumarin solutes, C151 and C152, into DPPC vesicle bilayers. These studies were motivated by earlier work that illustrated how amino acids affected bilayer structure and permeability. Results from DSC and time-resolved fluorescence emission showed that L-PA increases the amount of C152 in the nonpolar region of the DPPC bilayer at lower temperatures but decreases the amount of C152 in the polar backbone region. L-PA did not affect C151’s behavior, with virtually all C151 remaining in the aqueous buffer unaffected by the vesicle bilayers. These results implied that L-PA integrated into the bilayer and disrupting cohesive chain-chain interactions and also possibly becoming solvated in the glycerol backbone region.

In contrast, the DSC results together with time-resolved fluorescence emission suggested a different mechanism describing NAT-DPPC interactions. Specifically, changes to DPPC’s Tgel-lc as a function of NAT concentration and the presence of a coumarin solute imply that NAT interacts directly with the charged DPPC headgroup—presumably through coulomb interactions—and this NAT-DPPC binding induced site-specific adsorption of coumarin solutes from solution to the bilayer surface. These NAT-DPPC complexes introduced a new emission lifetime for C151, implying C151 association with the (modified) membrane surfaces. This association also drew C152 to the DPPC bilayer surface but inhibited C152 partitioning into the bilayer relative to L-PA-DPPC systems at temperatures below Tgel-lc. Once the bilayer melts, NAT had no discernible effect on C152 partitioning relative to C152 partitioning into NAT-free DPPC vesicle bilayers.

These descriptions of how different amino acids control solute partitioning into lipid bilayers are admittedly speculative and will likely evolve with improved experiments and more sophisticated modeling. Nevertheless, findings from these combined thermal and time-resolved emission studies necessitate different mechanisms describing how amino acids affect membrane properties. Discoveries described above will provide grist for the mill for continued studies of heterogeneous chemistry in complex biological systems.

Author contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

W.H.S. gratefully acknowledges sabbatical support from York College of Pennsylvania. This material is based upon work supported in part by the National Science Foundation Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research Cooperative Agreement OIA-1757351. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Editor: John Conboy.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.07.021.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Kwon J.H., Liljestrand H.M., Katz L.E. Partitioning of moderately hydrophobic endocrine disruptors between water and synthetic membrane vesicles. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2006;25:1984–1992. doi: 10.1897/05-550r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon J.H., Liljestrand H.M., Yamamoto H. Partitioning thermodynamics of selected endocrine disruptors between water and synthetic membrane vesicles: effects of membrane compositions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007;41:4011–4018. doi: 10.1021/es0618200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver M., Adrover M., Miró M. In-vitro prediction of the membranotropic action of emerging organic contaminants using a liposome-based multidisciplinary approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;738:140096. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Wezel A.P., Cornelissen G., Opperhuizen A. Membrane burdens of chlorinated benzenes lower the main phase transition temperature in dipalmitoyl-phosphatidylcholine vesicles: implications for toxicity by narcotic chemicals. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 1996;15:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer H. On the theory of alcohol narcosis: first communication. Which property of anesthetics determines its narcotic effect? Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 1899;425:109–118. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overton C.E. In: Studies of Narcosis—Charles Ernest Overton, 1991. Lipnick R., editor. Verlag Gustav Fischer; Jena, Germany: 1901. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leo A., Hansch C., Elkins D. Partition coefficients and their uses. Chem. Rev. 1971;71:525–616. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollastri M.P. Overview on the rule of five. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol. 2010;49:9.12.1–9.12.8. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0912s49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kah M., Brown C.D. LogD: lipophilicity for ionisable compounds. Chemosphere. 2008;72:1401–1408. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.04.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing L., Glen R.C. Novel methods for the prediction of logP, pK(a), and logD. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2002;42:796–805. doi: 10.1021/ci010315d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhal S.K., Kassam K., Pearl G.M. The Rule of Five revisited: applying log D in place of log P in drug-likeness filters. Mol. Pharm. 2007;4:556–560. doi: 10.1021/mp0700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gobas F.A., Lahittete J.M., Mackay D. A novel method for measuring membrane-water partition coefficients of hydrophobic organic chemicals: comparison with 1-octanol-water partitioning. J. Pharm. Sci. 1988;77:265–272. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600770317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Heijden S.A., Jonker M.T. Evaluation of liposome-water partitioning for predicting bioaccumulation potential of hydrophobic organic chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:8854–8859. doi: 10.1021/es902278x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endo S., Escher B.I., Goss K.U. Capacities of membrane lipids to accumulate neutral organic chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:5912–5921. doi: 10.1021/es200855w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipinski C.A. Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods. 2000;44:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8719(00)00107-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takegami S., Kitamura K., Kitade T. Partitioning of anti-inflammatory steroid drugs into phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylcholine-cholesterol small unilamellar vesicles as studied by second-derivative spectrophotometry. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2008;56:663–667. doi: 10.1248/cpb.56.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rai V., Tan H.S., Michniak-Kohn B. Effect of surfactants and pH on naltrexone (NTX) permeation across buccal mucosa. Int. J. Pharm. 2011;411:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.03.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maherani B., Arab-Tehrany E., Linder M. Calcein release behavior from liposomal bilayer; influence of physicochemical/mechanical/structural properties of lipids. Biochimie. 2013;95:2018–2033. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duncan K.M., Casey A., Walker R.A. Coumarin partitioning in model biological membranes: limitations of log P as a predictor. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124:8299–8308. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c06109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gobrogge C.A., Kong V.A., Walker R.A. Temperature-dependent partitioning of C152 in binary phosphatidylcholine membranes and mixed phosphatidylcholine/phosphatidylethanolamine membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:7889–7898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b04831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gobrogge C.A., Walker R.A. Quantifying solute partitioning in phosphatidylcholine membranes. Anal. Chem. 2017;89:12587–12595. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arias J.M., Cobos Picot R.A., Díaz S.B. Interaction of N-acetylcysteine with DPPC liposomes at different pH: a physicochemical study. New J. Chem. 2020;44:14837–14848. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arias J.M., Tuttolomondo M.E., Altabef A.B. Molecular view of the structural reorganization of water in DPPC multilamellar membranes induced by l-cysteine methyl ester. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1156:360–368. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cutró A.C., Disalvo E.A. Phenylalanine blocks defects induced in gel lipid membranes by osmotic stress. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:10060–10065. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b05590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cutro A.C., Disalvo E.A., Frías M.A. Effects of phenylalanine on the liquid-expanded and liquid-condensed states of phosphatidylcholine monolayers. Lipid Insights. 2019;12 doi: 10.1177/1178635318820923. 1178635318820923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosa A.S., Cutro A.C., Disalvo E.A. Interaction of phenylalanine with DPPC model membranes: more than a hydrophobic interaction. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:15844–15847. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b08490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White S.H., Wimley W.C. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1376:339–352. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(98)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johansson A.C., Lindahl E. The role of lipid composition for insertion and stabilization of amino acids in membranes. J. Chem. Phys. 2009;130:185101. doi: 10.1063/1.3129863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khandelia H., Ipsen J.H., Mouritsen O.G. The impact of peptides on lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:1528–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacCallum J.L., Bennett W.F., Tieleman D.P. Distribution of amino acids in a lipid bilayer from computer simulations. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3393–3404. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.112805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins R., Vaida V. Phenylalanine increases membrane permeability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:14388–14391. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nandi S., Pyne A., Sarkar N. Antagonist effects of l-phenylalanine and the enantiomeric mixture containing d-phenylalanine on phospholipid vesicle membrane. Langmuir. 2020;36:2459–2473. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b03543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanwa N., De S.K., Chakraborty A. Interaction of aliphatic amino acids with zwitterionic and charged lipid membranes: hydration and dehydration phenomena. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020;22:3234–3244. doi: 10.1039/c9cp06188f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gobrogge C.A., Blanchard H.S., Walker R.A. Temperature-dependent partitioning of coumarin 152 in phosphatidylcholine lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2017;121:4061–4070. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b10893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gobrogge C.A., Kong V.A., Walker R.A. Temperature dependent solvation and partitioning of coumarin 152 in phospholipid membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:1805–1812. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b09505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nad S., Pal H. Unusual photophysical properties of coumarin-151. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2001;105:1097–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nad S., Kumbhakar M., Kumbhakar H. Photophysical properties of coumarin-152 and coumarin-481 dyes: unusual behavior in nonpolar and in higher polarity solvents. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:4808–4816. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Purnell G.E., Walker R.A. Hindered isomerization at the silica/aqueous interface: surface polarity or restricted solvation? Langmuir. 2018;34:9946–9949. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b02299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy D., Liu S., Walker R.A. Nonpolar adsorption at the silica/methanol interface: surface mediated polarity and solvent density across a strongly associating solid/liquid boundary. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:27052–27061. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Purnell G.E., McNally M.T., Walker R.A. Buried liquid interfaces as a form of chemistry in confinement: the case of 4-dimethylaminobenzonitrile at the silica-aqueous interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:2375–2385. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Becker W. In: Advanced Time-Correlated Single Photon Counting Techniques. Castleman A.W. Jr., Toennies J.P., Zinth W., editors. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alanso A.G., Felix M. Effect of detergents and fusogenic lipids on phospholipid phase transitions. J. Membr. Biol. 1983;71:183–187. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kodama M., Kuwabara M., Seki S. Successive phase-transition phenomena and phase-diagram of the phosphatidylcholine-water system as revealed by differential scanning calorimetry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1982;689:567–570. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Link K.A., Spurzem G.N., Walker R.A. Organic enrichment at aqueous interfaces: cooperative adsorption of glucuronic acid to DPPC monolayers studied with vibrational sum frequency generation. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2019;123:5621–5632. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.9b02255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jain M.K., Min N.M. Effect of small molecules on the dipalmitoyl lecithin liposomal bilayer: III. Phase transition in lipid bilayer. J. Membr. Biol. 1977;34:157–201. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.