Key Points

Question

Does the probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) among critically ill patients?

Findings

In this randomized trial involving 2650 patients, no significant difference in VAP incidence was found among patients treated with probiotics compared with placebo (21.9% vs 21.3%, respectively; hazard ratio 1.03; 95% CI 0.87-1.22).

Meaning

These findings do not support the use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation.

Abstract

Importance

Growing interest in microbial dysbiosis during critical illness has raised questions about the therapeutic potential of microbiome modification with probiotics. Prior randomized trials in this population suggest that probiotics reduce infection, particularly ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), although probiotic-associated infections have also been reported.

Objective

To evaluate the effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG on preventing VAP, additional infections, and other clinically important outcomes in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized placebo-controlled trial in 44 ICUs in Canada, the United States, and Saudi Arabia enrolling adults predicted to require mechanical ventilation for at least 72 hours. A total of 2653 patients were enrolled from October 2013 to March 2019 (final follow-up, October 2020).

Interventions

Enteral L rhamnosus GG (1 × 1010 colony-forming units) (n = 1321) or placebo (n = 1332) twice daily in the ICU.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was VAP determined by duplicate blinded central adjudication. Secondary outcomes were other ICU-acquired infections including Clostridioides difficile infection, diarrhea, antimicrobial use, ICU and hospital length of stay, and mortality.

Results

Among 2653 randomized patients (mean age, 59.8 years [SD], 16.5 years), 2650 (99.9%) completed the trial (mean age, 59.8 years [SD], 16.5 years; 1063 women [40.1%.] with a mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score of 22.0 (SD, 7.8) and received the study product for a median of 9 days (IQR, 5-15 days). VAP developed among 289 of 1318 patients (21.9%) receiving probiotics vs 284 of 1332 controls (21.3%; hazard ratio [HR], 1.03 (95% CI, 0.87-1.22; P = .73, absolute difference, 0.6%, 95% CI, –2.5% to 3.7%). None of the 20 prespecified secondary outcomes, including other ICU-acquired infections, diarrhea, antimicrobial use, mortality, or length of stay showed a significant difference. Fifteen patients (1.1%) receiving probiotics vs 1 (0.1%) in the control group experienced the adverse event of L rhamnosus in a sterile site or the sole or predominant organism in a nonsterile site (odds ratio, 14.02; 95% CI, 1.79-109.58; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation, administration of the probiotic L rhamnosus GG compared with placebo, resulted in no significant difference in the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia. These findings do not support the use of L rhamnosus GG in critically ill patients.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02462590

This clinical trial assessed whether Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG compared with placebo reduces ventilator-associated pneumonia and other clinically important outcomes for a broad range of critically ill patients.

Introduction

Probiotics have emerged as a biologically plausible strategy to treat or prevent a wide range of infectious, inflammatory, and autoimmune conditions. Postulated mechanisms of benefit for a broad spectrum of diseases include enhanced gut barrier function, competitive inhibition of pathogenic bacteria, and modulation of the host inflammatory response.1,2 A recent randomized trial involving 2556 healthy newborns in rural India showed that Lactobacillus plantarum and fructooligosaccharide decreased the risk of sepsis and lower respiratory tract infection.3 Systematic reviews of randomized trials involving adults suggest that probiotics reduce antibiotic-associated diarrhea,4 but their effect on Clostridioides difficile infection appears inconsistent.5,6,7 Reports of iatrogenic probiotic–associated infections8 also highlight the need for evaluation of possible harm associated with their use.9

Among critically ill patients, randomized trials suggest that probiotics reduce infection rates by 20%10 and may decrease the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) by 25% to 30%.10,11 VAP remains a common, serious, nosocomial infection and an important focus of prevention directives for health care organizations. Economic evaluation suggests the cost-effectiveness of probiotics for VAP prevention.12 Current guidelines suggest probiotic use for selected medical and surgical intensive care unit (ICU) patients for whom trials have documented safety and benefit.13 Given the growing interest in microbial dysbiosis in the ICU and the therapeutic potential of microbiome modification,14,15 probiotics are a promising VAP prevention strategy. This multicenter trial was designed to determine whether Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG compared with placebo reduces VAP and other clinically important outcomes for a broad range of critically ill patients.

Methods

Following an internal blinded pilot trial16 documenting feasibility,17 the main trial was launched and included patients in pilot phase. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan were published (Supplement 1).18 Participating hospital institutional review boards approved the trial. Research coordinators obtained a priori written informed consent from eligible patients or substitute decision-makers. Forty-four ICUs participated from Canada (41 ICUs), the United States (2 ICUs), and Saudi Arabia (1 ICU).

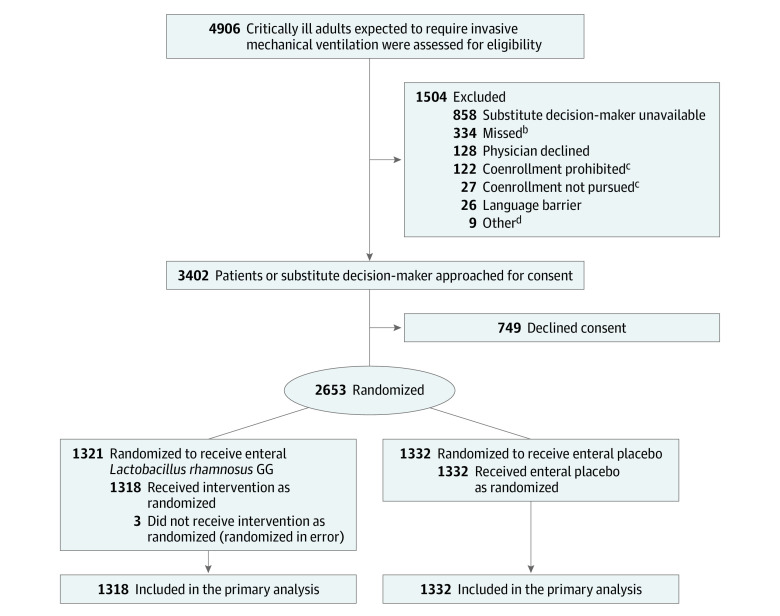

Enrolled patients were at least 18 years old, expected to require mechanical ventilation for at least 72 hours as determined by the treating ICU team (Figure 1). Excluded patients had already received mechanical ventilation for more than 72 hours; were immunocompromised (HIV with a CD4 cell count <200 cells/μL, chronic immunosuppressive medications, chemotherapy in the last 3 months, prior organ or hematological transplant, or absolute neutrophil count < 500 cells/μL); carried increased risk of endovascular infection18; had severe acute pancreatitis; had a percutaneous enteral feeding tube or were unable to receive enteral medication; had plans for palliation; and had previously enrolled in this trial or a related trial.

Figure 1. Screening, Selection, and Flow of Patients in PROSPECTa.

aNo data were collected on ineligible patients. Ten patients in the placebo group and 15 in the probiotics group had consent withdrawn for the study product but were followed up for outcomes and were included in the primary analysis.

bMissed patients included those admitted to the ICU on weekends or holidays or other times when the research coordinators or pharmacists were unavailable.

cEnrollment in an additional study.

dOther reasons included nonresidents, incarcerated patients, or family members who were not approached due to extreme stress.

Concealed 1:1 allocation in this parallel-group trial was stratified by center and admission status (medical, surgical, or trauma), using a web-based randomization system with undisclosed block sizes of 4 or 6. Patients, next of kin, and clinical and research staff remained blinded to allocation. Unblinded study pharmacists randomized patients and prepared the blinded study product.

Patients received 1 × 1010 colony forming units of L rhamnosus GG (i-Health Inc) or an identical enteral placebo solution (microcrystalline cellulose) twice daily. The study product was administered for up to 60 days or until discharge from the ICU or until Lactobacillus species was isolated from a sterile site or cultured as the sole or predominant organism from a nonsterile site. Throughout the trial, every 100th capsule from each site was cultured at the Laboratory for Interdisciplinary Microbiome Research at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario,18,19 to confirm the fidelity of viable probiotic dosing and the integrity of the placebo study product (eText, Supplement 2).

Research coordinators recorded baseline data (eg, demographics, illness severity, life support), daily data (eg, study product administration, pneumonia prevention strategies, and other cointerventions), culture results, infections, diarrhea (documented by bedside nurses), length of stay, and mortality by using a secure web-based system (iDataFax). Relevant anonymized clinical, microbiological, and radiological source data were submitted to the methods center.

Outcomes

The primary end point was VAP, informed by the presence of a new, progressive, or persistent radiographic infiltrate on chest radiograph after at least 2 days of mechanical ventilation, plus any 2 of the following: (1) fever (core temperature >38 °C) or hypothermia (temperature <36 °C); (2) white blood cell count less than 3.0 × 106/L or exceeding 10 × 106/L, and (3) purulent sputum.20,21

Secondary end points included different pneumonia classifications (eTable 1 in Supplement 2 for definitions),22,23,24,25 C difficile and other infections,18 and additional clinically important outcomes as detailed below. Early VAP (pneumonia 3-5 days after initiation of mechanical ventilation), was distinguished from late VAP (after ≥ 6 days of mechanical ventilation, including up to 2 days after discontinuing mechanical ventilation), and from postextubation pneumonia (arising ≥3 days after mechanical ventilation discontinuation). A composite outcome incorporated incident early VAP, late VAP, or postextubation pneumonia. All ICU-acquired infections were adjudicated, including bloodstream infections, intra-abdominal infection, C difficile infection (requiring diarrhea and laboratory confirmation or colonoscopic or histopathological evidence of pseudomembranous colitis26), upper genitourinary tract infection, skin and soft-tissue infection, other infections, adapted from the International Sepsis Forum.23 A composite outcome incorporated any of the foregoing ICU-acquired infections. Diarrhea was based on the World Health Organization definition (≥3 loose or watery bowel movements per day27), and the Bristol Stool Score classification for loose or watery stool (type 6 or 7).28 Antibiotic-associated diarrhea was defined as occurring any day on which any antibiotic was administered or within 1 day.29 Antimicrobial use (daily dose of therapy, defined daily dose, and antimicrobial-free days) were recorded in the ICU.18 Duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital length of stay, as well as ICU and hospital mortality were documented.

Clinically suspected infections were classified as prevalent if present before randomization, on the day of randomization, or 1 day after randomization; these were not considered trial outcomes and did not include persistent or progressive prevalent pneumonia. Prevalent infections were centrally adjudicated by 1 physician blinded to treatment allocation and center. Incident infections were trial outcomes, occurring 2 or more days after randomization. Clinically suspected incident pneumonia and C difficile infection were centrally adjudicated using the clinical notes and by microbiological and radiological source reports, following pilot calibration by 2 independent physicians blinded to allocation and center; disagreement was resolved by discussion or by a third investigator. Other incident infections were adjudicated by 1 physician blinded to allocation and center.

Adverse events were defined as the isolation of Lactobacillus species in a culture from a sterile site or as the sole or predominant organism cultured from a nonsterile site. Serious adverse events were those Lactobacillus isolates resulting in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or were life-threatening or resulting in death. Any culture obtained by clinicians, processed by the hospital microbiology laboratory as positive for Lactobacillus species was documented. The isolate when available underwent strain genotyping at the Microbiome Research Laboratory at McMaster University to analyze whether it was the strain of L rhamnosus GG used in the study product.

Statistical Analysis

Based on an estimated 15% VAP rate,17,22 2650 patients were enrolled to detect a 25% relative risk reduction (based on results from prior meta-analyses)10,30 with 80% power (α = .05).

Patients were all analyzed in the group to which they were allocated. Cox proportional hazards analysis used for the primary outcome was stratified by center and admission diagnosis (medical vs surgical vs trauma), and presented using Kaplan-Meier curves. The VAP incidence rate was reported as the number of cases per 1000 ventilator-days. A stratified Cox proportional hazards model, estimating hazard ratios (HRs) and associated 95% CIs was also used for dichotomous secondary outcomes. Skewed continuous secondary outcomes were log-transformed; if normally distributed, parametric methods were used to compare groups. If the outcome distributions remained skewed after log-transformation, nonparametric methods were used. Graphical approaches were used to examine residuals to assess model assumptions and goodness of fit, including the proportional hazards assumption for Cox-regression analyses. When the assumption of proportional hazards was not met, we compared the proportion of patients with the outcome between groups using the Mantel-Haenszel approach incorporating our stratification variables.

We conducted 4 prespecified sensitivity analyses18: (1) The proportion of patients with VAP between groups were compared using the Mantel-Haenszel approach incorporating our stratification variables; (2) VAP results were analyzed accounting for death as a competing risk using the Fine and Gray proportional subdistribution hazards model31; (3) A per-protocol analysis of each incident infection and a composite of all ICU-acquired infections among patients receiving the study product for 90% or more of the study days to evaluate maximal probiotic exposure were conducted; and (4) All VAP events were analyzed regardless of when they occurred after randomization.

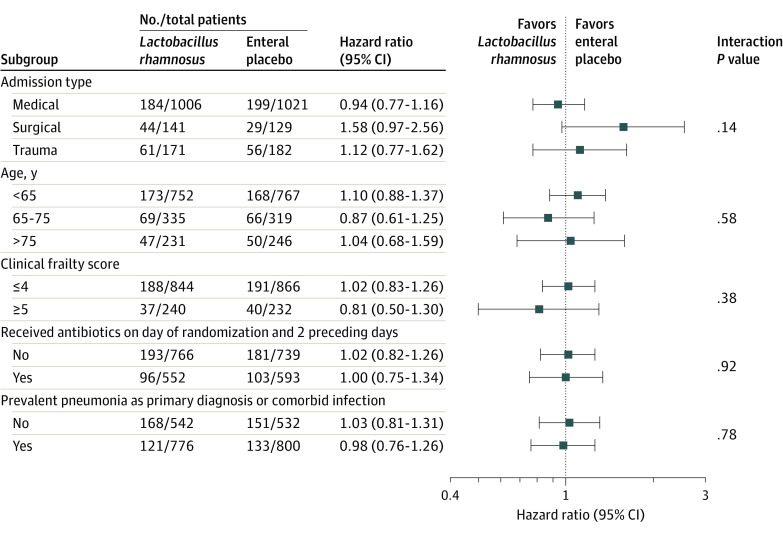

Five prespecified subgroup analyses were conducted for the primary outcome of VAP by adding a main effect for the subgroup variable as well as its interaction with randomized treatment to the primary Cox proportional hazards analysis.18 The test for interaction was the test for significance of the interaction term in this analysis. The subgroup analyses were (1) medical vs surgical vs trauma patients; (2) age (>75 years vs 65-75 years vs <65 years); (3) Baseline Clinical Frailty Score (≥532 vs ≤4); (4) patients receiving antibiotics the day of randomization and the 2 preceding days vs other patients; and (5) patients with prevalent pneumonia vs other patients. The hypotheses were that the probiotic effects on the primary outcome would be attenuated in older medical patients due to frailty and immunosenescence, as well as in those who received antibiotics prior to randomization and who had prevalent pneumonia, given that these are pneumonia risk factors that are potentially less likely to be modified by probiotics.

The data monitoring committee independently reviewed blinded interim analyses, with no stopping guides for futility, and conservative warning guides for benefit. Interim analyses occurred at one-third and two-thirds of enrollment using 2-sided tests with a fixed conservative α = .001 for the first and second interim analyses, and an α = .05 for final analyses,33,34 using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). All analyses used 2-sided testing and an α = .05. Analyses of secondary outcomes as well as sensitivity and subgroup analyses were not adjusted for multiple comparisons and should be interpreted as exploratory.35 No multiple imputation analyses were needed for missing data because missing data were 0.5%, less than the threshold specified in our statistical analysis plan.18 In Cox regressions, patients who did not have complete follow-up for outcomes were censored on the final data collection day.

Results

Participants

Of the randomized patients included in the primary analysis, 1318 patients received L rhamnosus GG (probiotic) and 1332 received placebo (Figure 1).

Of the 2650 participants (mean age, 59.8 years [SD, 16.5 years]; mean Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score, 22.0 [SD, 7.8]), 1063 (40.1%) were women and 2027 (76.5%) had a medical admitting diagnosis. At baseline, all patients were receiving mechanical ventilation, 1621 (61.2%) were receiving inotropes or vasopressors, and 215 (8.1%) were receiving kidney replacement therapy.

On admission, 1877 patients (70.8%) had a prevalent infection, 1576 (59.5%) of whom had pneumonia as a concurrent or primary admitting diagnosis. Antimicrobials were prescribed or ongoing for 2186 patients (82.5%) on the day of randomization. Baseline characteristics between the probiotic and placebo groups were not significantly different (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Patients.

| No. (%) of patients | ||

|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (n = 1318) | Placebo (n = 1332) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 60.1 (16.2) | 59.6 (16.8) |

| Women | 541 (41.0) | 522 (39.2) |

| Men | 777 (59.0) | 810 (60.8) |

| Clinical frailty score ≥5, No./total (%)a | 240/1084 (22.1) | 232/1098 (21.1) |

| APACHE II score, mean (SD)b | 22.3 (7.8) | 21.7 (7.9) |

| Admission category | ||

| Medical | 1006 (76.3) | 1021 (76.7) |

| Trauma | 171 (13.0) | 182 (13.7) |

| Surgical | 141 (10.7) | 129 (9.7) |

| Admitting diagnostic category | ||

| Respiratory | 441 (33.5) | 476 (35.7) |

| Neurological | 227 (17.2) | 242 (18.2) |

| Trauma | 180 (13.7) | 184 (13.8) |

| Sepsis | 179 (13.6) | 147 (11.0) |

| Cardiovascular | 118 (9.0) | 130 (9.8) |

| Other medical | 91 (6.9) | 73 (5.5) |

| Gastrointestinal | 50 (3.8) | 54 (4.1) |

| Other surgical | 32 (2.4) | 26 (2.0) |

| Other medical | ||

| Patient experience prior to randomization, median (IQR) | ||

| ICU admission to randomization, d | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) |

| Intubation to randomization, d | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) |

| Critical care intervention on day 1 | ||

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 1318 (100.0) | 1332 (100.0) |

| Inotropes or vasopressors | 798 (60.5) | 823 (61.8) |

| Dialysisc | 106 (8.0) | 109 (8.2) |

| Enteral and parenteral nutrition on day 1 | ||

| Enteral nutrition on day 1 | 1140 (86.5) | 1151 (86.5) |

| Parenteral nutrition on day 1 | 12 (0.9) | 19 (1.4) |

| Prevalent infectionsd | ||

| Pneumoniae | 776 (58.9) | 800 (60.1) |

| Bacteremia | 142 (10.8) | 134 (10.1) |

| Skin or soft-tissue infection | 91 (6.9) | 76 (5.7) |

| Other infectionsf | 79 (6.0) | 77 (5.8) |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 48 (3.6) | 44 (3.3) |

| Clostridioides difficile infection | 16 (1.2) | 10 (0.8) |

| Upper urinary tract infectiong | 9 (0.7) | 12 (0.9) |

| Antibiotic exposure | ||

| Use at randomization | 1095 (83.1) | 1091 (81.9) |

| Use at randomization and the 2 d before | 552 (41.9) | 593 (44.5) |

Degree of fitness and frailty (range, 1-9: 1, very fit; 5, mildly frail; 9, terminally ill).32 Results were collected for patients randomized on or after May 23, 2016 (not captured retrospectively or for pilot trial patients).

Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE-II) score measures the severity of illness within the first 24 hours of a patient’s admission to an intensive care unit (ICU; range 0 to 71, higher scores indicate more severe disease and a higher risk of death).

Patients with chronic kidney failure who received dialysis prior to the index admission or requiring dialysis.

Prevalent infections are not mutually exclusive, and they include conditions such as the infections listed as well as other infections listed in footnote f.

Any prevalent pneumonia (community acquired, hospital acquired, ventilator associated).

Other infections (eg, meningitis, encephalitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, sinusitis, mediastinitis).

Microbiologically confirmed abscess or other radiographic or surgical evidence of upper urinary tract infection with or without positive urine culture (positive urine culture alone not included).

Of 2650 patients, 14 (9 in the probiotics and 5 in the placebo group) had consent withdrawn for daily data collection. These patients are represented in all analyses; mortality is documented in each case; for all other outcomes, these patients were censored on their last day of daily data collection.

Study Product Integrity, Exposure, and Adherence

The study product was administered for a median of 9 days (IQR, 5-15 days) in both groups. Overall, 2630 of 2650 patients (99.2%) received at least 1 dose (identical proportions in both groups). Patients received at least 1 dose on 32 458 of 36 046 study days (90.0%); results were not significantly different in the probiotic group (16 471 of 18 319 [89.9%]) and placebo group (15 987 of 17 727 [90.2%]).

Primary Outcome

Among 1318 patients receiving L rhamnosus GG, 289 (21.9%) developed VAP compared with 284 of 1332 patients (21.3%) receiving placebo (hazard ratio [HR], 1.03; 95% CI, 0.87 to 1.22; P = .73; absolute difference, 0.6%; 95% CI, –2.5% to 3.7%; Table 2; eFigure in Supplement 2). Sensitivity analyses (eTable 2 in Supplement 2) yielded no significantly different results. Subgroup analyses did not indicate any effect modification based on diagnostic category (medical, surgical, or trauma), age, frailty status, prior receipt of antimicrobials, or prevalent pneumonia at baseline (Figure 2).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomesa.

| No. (%) of patients | Absolute difference (95% CI), %b | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (n = 1318) | Placebo (n = 1332) | ||||

| Primary outcome | |||||

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia at any time18,20 | 289 (21.9) | 284 (21.3) | 0.6 (–2.5 to 3.7) | 1.03 (0.87 to 1.22) | .73 |

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

| Pneumonia | |||||

| Early ventilator-associated pneumoniac | 50 (3.8) | 61 (4.6) | –0.8 (–2.3 to 0.7) | 0.80 (0.55 to 1.17) | .26 |

| Late ventilator-associated pneumoniad | 243 (18.4) | 231 (17.3) | 1.1 (–1.8 to 4.0) | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.32) | .35 |

| Postextubation pneumoniae | 22 (1.7) | 20 (1.5) | 0.2 (–0.8 to 1.1) | 1.21 (0.63 to 2.32) | .58 |

| Any pneumoniaf | 307 (23.3) | 300 (22.5) | 0.8 (–2.4 to 4.0) | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.23) | .61 |

| Other infections | |||||

| Any infectiong | 414 (31.4) | 418 (31.4) | 0.0 (–3.5 to 3.6) | 0.97 (0.84 to 1.11) | .64 |

| Positive urine culture | 171 (13.0) | 174 (13.1) | –0.1 (–2.7 to 2.5) | 0.99 (0.79 to 1.24) | .96 |

| Any bacteremia | 106 (8.0) | 101 (7.6) | 0.5 (–1.6 to 2.5) | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.44) | .58 |

| Skin or soft-tissue infection, nonsurgical | 37 (2.8) | 28 (2.1) | 0.7 (–0.5 to 1.9) | 1.11 (0.67 to 1.85) | .68 |

| Any Clostridioides difficile infectionh | 32 (2.4) | 28 (2.1) | 0.3 (–0.8 to 1.5) | 1.15 (0.69 to 1.93) | .60 |

| Other infectionsi | 28 (2.1) | 37 (2.8) | –0.7 (–1.8 to 0.5) | 0.74 (0.45 to 1.22) | .24 |

| Skin or soft-tissue infection, surgical site | 28 (2.1) | 33 (2.5) | –0.4 (–1.5 to 0.8) | 0.80 (0.46 to 1.39) | .43 |

| Intra-abdominal infection | 19 (1.4) | 22 (1.7) | –0.2 (–1.2 to 0.7) | 0.79 (0.41 to 1.50) | .47 |

| Upper urinary tract infectionj | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | –0.1 (–0.4 to 0.3) | 1.02 (0.14 to 7.26) | .98 |

| Diarrhea | |||||

| ≥ 3 Stools per d | 861 (65.3) | 855 (64.2) | 1.1 (–2.5 to 4.8) | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.11) | .90 |

| ≥1 Stools of Bristol type 6 or 7k | 1076 (81.6) | 1080 (81.1) | 0.6 (–2.4 to 3.5) | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.17) | .13 |

| ≥3 Bristol type 6 or 7 stools per dk | 756 (57.4) | 731 (54.9) | 2.5 (–1.3 to 6.3) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) | .66 |

| Antibiotic-associated diarrhea | |||||

| ≥3 Stools per d | 785 (59.6) | 787 (59.1) | 0.5 (–3.3 to 4.2) | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) | .63 |

| ≥1 Stools of Bristol type 6 or 7k | 1014 (76.9) | 1016 (76.3) | 0.7 (–2.6 to 3.9) | 1.07 (0.98 to 1.17) | .14 |

| ≥3 Bristol type 6 or 7 stools per dk | 691 (52.4) | 671 (50.4) | 2.1 (–1.8 to 5.9) | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.15) | .57 |

| Other clinical outcomes | |||||

| Mechanical ventilation, median (IQR), d | 7 (4 to 13) | 7 (4 to 13) | .81l | ||

| ICU stay, median (IQR), d | 12 (7 to 19) | 12 (8 to 18) | .45m | ||

| Hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 22 (13 to 42) | 22 (13 to 40) | .42m | ||

| Death in ICU | 279 (21.2) | 296 (22.2) | –1.1 (–4.2 to 2.1) | 0.91 (0.77 to 1.08) | .30 |

| Death in hospital | 363 (27.5) | 381 (28.6) | –1.1 (–4.5 to 2.4) | 0.91 (0.79 to 1.06) | .21 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

All definitions are detailed in.18 The number of ventilator-associated pneumonia cases per 1000 ventilator days was 23.3 in the probiotics group and 23.1 in the placebo group.

Unadjusted absolute difference.

Diagnosed on day 3 to 5 after initiation of mechanical ventilation.

Diagnosed on or after day 6 of mechanical ventilation, including up to 2 days after mechanical ventilation discontinued.

Pneumonia arising 3 or more days after mechanical ventilation discontinued.

Composite outcome of incident early ventilator-associated pneumonia, late ventilator-associated pneumonia, or postextubation pneumonia. Rarely, will a patient with an early ventilator-associated pneumonia that resolves (clinically from the perspective of signs and symptoms, microbiologically, and/or radiographically) develop a second ventilator-associated pneumonia 2 weeks later. The rows may therefore not add up to the composite total.

Any of the foregoing infections, not including positive urine cultures alone, considering only the adjudicated pneumonia outcome.

Graphical approaches indicated that the assumption of proportional hazards was not met for C difficile; the proportions analysis odds ratio was 1.15 (95% CI, 0.69-1.93; P value = .598).

Meningitis, encephalitis, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, sinusitis, mediastinitis, etc.

Microbiologically confirmed abscess or other radiographic or surgical evidence of upper urinary tract infection with or without positive urine culture (positive urine culture alone not included).

Stool classification system that characterizes each bowel movement (scale range,1-7 ).28 Types 1 or 2 stool indicates constipation; types 6 and 7 indicate diarrhea.

Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

t Test performed on the log-transformed variable.

Figure 2. Subgroup Analyses: Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia.

Secondary Outcomes

Applying alternative definitions for pneumonia, results were comparable with the primary analysis (eTable 1 in Supplement 2). C difficile infection developed in 32 patients (2.4%) receiving probiotics vs 28 (2.1%) receiving placebo (Table 2). Because graphical approaches indicated that the proportional hazards assumption was not met for this infection, we ran a proportions analysis, which yielded an odds ratio (OR) of 1.15 (95% CI, 0.69 to 1.93; P = .60; absolute difference, 0.3% (95% CI, –0.8% to 1.5%). No significant difference between groups for any infectious outcomes was found (Table 2); per-protocol analyses yielded no significantly different results (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Diarrhea occurred in 2156 patients (81.4%) when defined as 1 or more stools of Bristol types 6 or 7. There was no significant difference in diarrhea between patients in the probiotic vs placebo groups using any definition (Table 2). Antibiotic-associated diarrhea was also common; there was no significant difference between groups using any definition (Table 2).

Antimicrobial use was not significantly different between patients receiving probiotics vs placebo, considering metrics of length of therapy, days of therapy, defined daily dose or antimicrobial-free days (all per 1000 patient-days in the ICU; eTable 4 in Supplement).

Patients received mechanical ventilation for a median of 7 days (IQR, 4-13 days). The median duration of ICU stay of 12 days8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and hospital stay of 22 days (IQR, 13-41 days) were not significantly different between groups. In the ICU, 279 patients (21.2%) in the probiotics group and 296 patients (22.2%) in the placebo group died (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.77 to 1.08; P = .30; absolute difference, –1.1%; 95% CI, −4.2% to 2.1%). Death in the hospital occurred in 363 patients (27.5%) in the probiotics group and 381 (28.6%) in the placebo group (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.79 to 1.06; P = .21; absolute difference, –1.1%; 95% CI, –4.5% to 2.4%; Table 2).

Adverse Events and Serious Adverse Events

Of the 16 patients with an adverse event (isolation of Lactobacillus species in a culture from a sterile site or as the sole or predominant organism in a nonsterile site) or serious adverse event during the trial, 12 Lactobacillus isolates were available to sequence; 12 were confirmed as L rhamnosus GG, which were all in the probiotic group (Table 3). The sources included 10 blood, 1 blood and hepatic abscess, 1 intra-abdominal abscess, 1 peritoneal fluid, 1 pleural fluid, and 2 urine. Fifteen patients (1.1%) receiving probiotics compared with 1 patient (1.1%) receiving placebo experienced either an adverse event or a serious adverse event (OR, 14.02; 95% CI, 1.79-109.58; P = .001). Both patients who had a serious adverse event died. (eTable 5 in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Adverse and Serious Adverse Events.

| No. (%) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (n = 1318) | Placebo (n = 1332) | ||

| Adverse eventsa | 13 (1.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Serious adverse eventsb | 2 (0.2) | 0 | |

| Serious adverse events or adverse events | 15 (1.1) | 1 (0.1) | 14.02 (1.79-109.58) |

Defined as the isolation of Lactobacillus species in a culture from a sterile site or as the sole or predominant organism cultured from a nonsterile site.

Defined as Lactobacillus isolates that resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, were life-threatening, or resulted in death.

Discussion

In this trial involving critically ill patients, the probiotic L rhamnosus GG did not significantly reduce the risk of VAP, C difficile, or other infections. Furthermore, no effects on diarrhea, antimicrobial use, length of stay or mortality were identified. In this broad population of ICU patients with high illness severity, life support dependence, antimicrobial exposure, and propensity for ICU-acquired infection, L rhamnosus GG did not confer any other benefits.

These results differ from meta-analyses of previous small, predominantly single-center studies, suggesting decreased VAP rates associated with probiotics during critical illness, including this strain.10,11 However, findings from this trial do accord with a trial showing no effect of a Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium preparation on C difficile infection in older hospitalized patients receiving antibiotics.7 Furthermore, the increased risk of adverse events observed among patients receiving probiotics aligns with a recent report of L rhamnosus GG bacteremia in critically ill children prescribed this probiotic.36 These results indicate that, although critically ill patients exhibit loss of commensal microbiota, overgrowth of potential pathogens and thus highly perturbed microbial communities,14,15,37 probiotics may not improve clinically important outcomes associated with dysbiosis in this setting. Rigorous probiotics trials with neutral results enhance clinical decision-making, inform resource allocation, and ensure balanced systematic reviews and guidelines.

In this trial population, central genomic analyses of clinical specimens allowed distinction between endogenous or environmental strains of Lactobacillus species and the study product. Isolation of the probiotic Lactobacillus species in sterile sites such as blood may reflect impaired gut integrity, despite excluding patients at risk of increased gut permeability and withholding the study product if this developed in enrolled patients. Some bloodstream isolates may represent contamination during clinical testing in patients receiving the study product, although strict infection prevention protocols guided capsule handling. Lactobacillus species bacteremia may have clinical significance, increasing the risk of death when serious underlying comorbidities coexist.38

This randomized, concealed, blinded trial had high protocol adherence and no loss to follow-up. Probiotic capsule integrity was independently documented,19 aligning with calls for larger rigorous trials of probiotics in a range of human conditions.8,9,36 All infectious outcomes underwent blinded adjudication. Analyses were prespecified, and findings were consistent in unadjusted, adjusted, prespecified sensitivity and subgroup analyses.39 Participation of 44 centers in 3 countries over 4 years enhances the generalizability of results for this population. The findings have implications for practice and policy,13 suggesting circumspect prescribing of probiotics during serious illness.40

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, in the absences of direct comparative studies, L rhamnosus GG was the probiotic evaluated, given that it is the most common intervention tested in this setting that had shown initial promise.21 However, results may have differed using an alternate dose, genus, species, or strain or if studied in specialized populations such as patients who experienced trauma or were of low surgical risk with lower antimicrobial exposure or lower infectious risk. Second, it was not possible to examine pulmonary microbiota over time or between groups, or probiotic gastrointestinal colonization in this international trial. Third, there are inherent limitations of each VAP definition and no universal reference standard; however, our analyses were strengthened by protocolized data collection and use of several definitions.18

Conclusions

Among critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation, administration of the probiotic L rhamnosus GG compared with placebo resulted in no significant difference in the development of ventilator-associated pneumonia. These findings do not support the use of L rhamnosus GG for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia or other clinically important outcomes in critically ill patients.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure. Kaplan-Meier curve for primary outcome, ventilator-associated pneumonia

eTable 1. Alternative pneumonia definition outcomes

eTable 2: Sensitivity analyses

eTable 3: Per-protocol analyses for other infectious outcomes

eTable 4: Antimicrobial administration

eTable 5: Characteristics of patients with lactobacillus isolates: serious adverse events and adverse events

Nonauthor Collaborators. The PROSPECT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group members

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Relman DA. The human microbiome and the future practice of medicine. JAMA. 2015;314(11):1127-1128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bassetti M, Bandera A, Gori A. Therapeutic potential of the gut microbiota in the management of sepsis critical care. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):105. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2780-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panigrahi P, Parida S, Nanda NC, et al. A randomized synbiotic trial to prevent sepsis among infants in rural India. Nature. 2017;548(7668):407-412. doi: 10.1038/nature23480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hempel S, Newberry SJ, Maher AR, et al. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;307(18):1959-1969. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston BC, Lytvyn L, Lo CK, et al. Microbial preparations (probiotics) for the prevention of Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: an individual patient data meta-analysis of 6,851 participants. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(7):771-781. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldenberg JZ, Yap C, Lytvyn L, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12(12):CD006095. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen SJ, Wareham K, Wang D, et al. Lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in older inpatients (PLACIDE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2013;382(9900):1249-1257. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61218-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hempel S, Newberry S, Ruelaz A, et al. Safety of probiotics used to reduce risk and prevent or treat disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2011;200(200):1-645. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bafeta A, Koh M, Riveros C, Ravaud P. Harms reporting in randomized controlled trials of interventions aimed at modifying microbiota: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(4):240-247. doi: 10.7326/M18-0343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manzanares W, Lemieux M, Langlois PL, Wischmeyer PE. Probiotic and synbiotic therapy in critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2016;19:262. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1434-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batra P, Soni KD, Mathur P. Efficacy of probiotics in the prevention of VAP in critically ill ICU patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. J Intensive Care. 2020;8:81. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00487-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branch-Elliman W, Wright SB, Howell MD. Determining the ideal strategy for ventilator-associated pneumonia prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(1):57-63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2316OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. ; Society of Critical Care Medicine; American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition . Guidelines for the provision and assessment of nutrition support therapy in the adult critically ill patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN). JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2016;40(2):159-211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald D, Ackermann G, Khailova L, et al. Extreme dysbiosis of the microbiome in critical illness. mSphere. 2016;1(4):e00199-e16. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00199-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitsios GD, Morowitz MJ, Dickson RP, Huffnagle GB, McVerry BJ, Morris A. Dysbiosis in the intensive care unit: microbiome science coming to the bedside. J Crit Care. 2017;38:84-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnstone J, Meade M, Marshall J, et al. ; PROSPECT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group . Probiotics: Prevention of Severe Pneumonia and Endotracheal Colonization Trial-PROSPECT: protocol for a feasibility randomized pilot trial. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2015;1:19. doi: 10.1186/s40814-015-0013-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook DJ, Johnstone J, Marshall JC, et al. ; PROSPECT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group . Probiotics: prevention of severe pneumonia and endotracheal colonization Trial-PROSPECT: a pilot trial. Trials. 2016;17:377. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1495-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnstone J, Heels-Ansdell D, Thabane L, et al. ; PROSPECT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group . Evaluating probiotics for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a randomised placebo-controlled multicentre trial protocol and statistical analysis plan for PROSPECT. BMJ Open. 2019;9(6):e025228. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamarche D, Rossi L, Shah M, et al. Quality control in the conduct of a probiotic randomized trial. Abstract presented at: Critical Care Canada Forum; October 28, 2014: Toronto, ON. Accessed August 25, 2021. https://criticalcarecanada.com/abstracts/2014/quality_control_in_the_conduct_of_a_probiotic_randomized_trial.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossman RF, Fein A. Evidence-based assessment of diagnostic tests for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Executive summary. Chest. 2000;117(4)(suppl 2):177S-181S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.4_suppl_2.177S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrow LE, Kollef MH, Casale TB. Probiotic prophylaxis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(8):1058-1064. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200912-1853OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heyland D, Muscedere J, Wischmeyer PE, et al. ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group . A randomized trial of glutamine and antioxidants in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(16):1489-1497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calandra T, Cohen J; International Sepsis Forum Definition of Infection in the ICU Consensus Conference . The International Sepsis Forum Consensus Conference on definitions of infection in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(7):1538-1548. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000168253.91200.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pugin J, Auckenthaler R, Mili N, Janssens JP, Lew PD, Suter PM. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia by bacteriologic analysis of bronchoscopic and nonbronchoscopic “blind” bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;143(5 Pt 1):1121-1129. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/143.5_Pt_1.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36(5):309-332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SH, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. ; Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; Infectious Diseases Society of America . Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults: 2010 update by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(5):431-455. doi: 10.1086/651706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization . Accessed November 29, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease

- 28.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920-924. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thibault R, Graf S, Clerc A, et al. Diarrhea in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2013;17:R153. doi: 10.1186/cc12832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrof EO, Dhaliwal R, Manzanares W, Johnstone J, Cook D, Heyland DK. Probiotics in the critically ill: a systematic review of the randomized trial evidence. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(12):3290-3302. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318260cc33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94(446):496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489-495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haybittle JL. Repeated assessment of results in clinical trials of cancer treatment. Br J Radiol. 1971;44(526):793-797. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-44-526-793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized control trials requiring prolonged observations of each patient, I: introduction and design. British J Cancer. 1976;34:585. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li G, Taljaard M, Van den Heuvel ER, et al. An introduction to multiplicity issues in clinical trials: the what, why, when and how. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(2):746-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yelin I, Flett KB, Merakou C, et al. Genomic and epidemiological evidence of bacterial transmission from probiotic capsule to blood in ICU patients. Nat Med. 2019;25(11):1728-1732. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0626-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamarche D, Johnstone J, Zytaruk N, et al. ; PROSPECT Investigators; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group; Canadian Critical Care Translational Biology Group . Microbial dysbiosis and mortality during mechanical ventilation: a prospective observational study. Respir Res. 2018;19(1):245. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0950-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salminen MK, Rautelin H, Tynkkynen S, et al. Lactobacillus bacteremia, clinical significance, and patient outcome, with special focus on probiotic L. rhamnosus GG. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(1):62-69. doi: 10.1086/380455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schandelmaier S, Briel M, Varadhan R, et al. Development of the Instrument to assess the Credibility of Effect Modification Analyses (ICEMAN) in randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses. CMAJ. 2020;192(32):E901-E906. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yi SH, Jernigan JA, McDonald LC. Prevalence of probiotic use among inpatients: a descriptive study of 145 US hospitals. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(5):548-553, 548-553. z. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

eFigure. Kaplan-Meier curve for primary outcome, ventilator-associated pneumonia

eTable 1. Alternative pneumonia definition outcomes

eTable 2: Sensitivity analyses

eTable 3: Per-protocol analyses for other infectious outcomes

eTable 4: Antimicrobial administration

eTable 5: Characteristics of patients with lactobacillus isolates: serious adverse events and adverse events

Nonauthor Collaborators. The PROSPECT Investigators and the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group members

Data Sharing Statement