Abstract

Rationale: Tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) play a critical role in the defense against inhaled pathogens. The isolation and study of human lung tissue–resident memory T cells and lung-resident macrophages (MLR) are limited by experimental constraints.

Objectives: To characterize the spatial and functional relationship between MLR and human lung tissue–resident memory T cells using ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP).

Methods: TRM and MLR were isolated using EVLP and intraperfusate-labeled CD45 antibody. Cells isolated after 6 hours of EVLP were analyzed using spectral flow cytometry. Spatial relationships between CD3+ and CD68+ cells were explored with multiplexed immunohistochemistry. Functional relationships were determined by using coculture and T-cell–receptor complex signal transduction.

Measurements and Main Results: Lungs from 8 research-consenting organ donors underwent EVLP for 6 hours. We show that human lung TRM and MLR colocalize within the human lung, preferentially around the airways. Furthermore, we found that human lung CD8+ TRM are composed of two functionally distinct populations on the basis of PD1 (programed cell death receptor 1) and ZNF683 (HOBIT) protein expression. We show that MLR provide costimulatory signaling to PD1hi CD4+ and CD8+ lung TRM,, augmenting the effector cytokine production and degranulation of TRM.

Conclusions: EVLP provides an innovative technique to study resident immune populations in humans. Human MLR colocalize with and provide costimulation signaling to TRM, augmenting their effector function.

Keywords: ex vivo lung perfusion, human lung immunology, tissue-resident memory T cell, lung-resident macrophage, innate and adaptive immune interaction

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Lungs contain a large quantity of tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM), which reside at the mucosal surface and are relatively specific to common inhaled pathogens, like influenza and respiratory syncytial virus. Most of our understanding about the biology of lung TRM comes from murine models; the study of maintenance and function of human lung TRM has been limited by experimental constraints.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Using ex vivo lung perfusion, this translational investigation establishes a novel means to isolate and study TRM and lung-resident macrophages (MLR) from human lungs. This study found that human lungs have a large population of TRM that colocalize with MLR, mainly around the small airways. The majority of CD4+ and CD8+ lung TRM have increased cell-surface expression of PD1 (programmed cell death protein 1). These PD1hi TRM have increased effector functional capacity when stimulated in the presence of lung macrophages, suggesting that MLR colocalize with and provide costimulatory signaling to PD1hi lung TRM.

Experimental mouse models have established that after infection, the mouse lung contains a large population of pathogen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, most of which are tissue-resident T cells, do not recirculate, and have a rapid effector response when presented with a secondary challenge (1, 2). Human studies have similarly shown that lungs are enriched with tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) that are specific to many inhaled pathogens, including influenza (3, 4), respiratory syncytial virus (5, 6), Streptococcus pneumoniae, and mycobacterial tuberculosis (7). Furthermore, in humans, the presence of respiratory syncytial virus–specific lung TRM is associated with decreased severity of illness on secondary exposure (6). Mouse models have shown that this secondary response is not reliant on antigen priming in the secondary lymphoid organs, suggesting an in situ response to inhaled pathogens (3).

The local factors that allow a rapid effector response of TRM are not fully elucidated. Lung-resident macrophages (MLR), composed of both alveolar and bronchial macrophages, are the most abundant resident immune population in the lung (8). MLR are vital for defense against inhaled pathogens and play key roles in tissue homeostasis, abrogating the inflammatory response to apoptosis via phagocytosis of cellular debris (9, 10). Given their location at the site of first exposure to a pathogen, alveolar and bronchial macrophages would be ideal for providing a costimulatory signal to TRM after antigen exposure. However, this has yet to be reported.

Herein, we establish ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) as an effective means for isolating human lung TRM and MLR for investigation. We show that TRM persist within the lung throughout 6 hours of EVLP, and by introducing a labeled CD45 antibody into the perfusate, we can accurately differentiate lymphocytes that are TRM from those that are not. Furthermore, we show that TRM and MLR cocluster within the human lung, predominantly around the airways. We found that PD1 (programed cell death receptor 1)hi CD4+ and CD8+ lung TRM have an augmented effector and cytotoxic response to T-cell–receptor complex signaling when cocultured with MLR, resulting in enhanced protein expression of IFNγ, TNFα (tumor necrosis factor α), and LAMP1 (CD107a), suggesting that MLR provide a costimulatory signal to TCR-complex signaling. PD1loCD8+ TRM were composed mainly of ZNF683 (HOBIT)hi TBET (T-box transcription factor TBX21)hi cells with high granzyme B content that was largely unaffected by TCR-complex signaling. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract to the American Thoracic Society (11).

Methods

Human Lungs and EVLP

We obtained human donor lungs (N = 8, Table 1) declined for transplantation from the organ-procurement organization serving our region (Center for Organ Recovery and Education). This process was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Center for Organ Research Involving Decedents. The technique of normothermic EVLP has been described previously and can be found in the online supplement (see Methods and Figure E1 in the online supplement; see also Figure 1A) (12). Lung biopsy specimens, BAL fluid, and perfusate were sampled as outlined in Figure 1B. BAL was performed with a disposable bronchoscope in the lateral segment of the left or right lower lobe. Fifty milliliters of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected after wedging the bronchoscope, and the return fluid was used for the analysis. Fifteen milliliters of perfusate was removed from the circuit at each study time point. Supernatant was obtained from both perfusate and BAL samples after centrifugation for 5 minutes at 1,500 rotations/min. At 0 hours, a lung biopsy specimen was obtained from the lingula, right middle lobe, or left lower lobe using an Endo GIA Ultra surgical stapler (Covidien) with a 60-mm articulating reload; at 6 hours, the biopsy specimen was obtained by manual excision after removal of the lung from the perfusion circuit. Lung biopsies were divided, half underwent fixation with zinc-buffered formaldehyde for immunohistochemistry (IHC), and the remainder underwent mechanical and enzymatic digestion to obtain a single-cell suspension.

Table 1.

Lung Donor Demographics

| Sample ID | Age | Sex | BMI | Reason Lungs Not Used Clinically | PaO2/FiO2 (T0/T6) | Weight Change (g) | Cold Ischemia (min) | Compliance at T6 (dyn) | Labeled CD4+ T Cells (%) | Labeled CD8+ T Cells (%) | Labeled Myeloid Cells (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV19-001 | 49 | F | 40 | Poor-quality NOS | 543/547 | NA | 180 | 21 | 2 | 12 | — |

| EV19-002 | 46 | F | 31 | Not offered by OPO | 585/507 | +433 | 600 | 35 | 1 | 16 | — |

| EV19-003 | 41 | M | 22 | Poor perfusion distribution | 461/592 | +107 | 240 | 62 | 11 | 5 | — |

| EV19-004 | 57 | M | 25 | Initially low PaO2 | NA/498 | +627 | 60 | 115 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| EV19-006 | 63 | M | 26 | DCD | 507/540 | +188 | 60 | 96 | 3 | 7 | 13 |

| EV20-001 | 53 | M | 37 | Not offered by OPO | NA/600 | +196 | 420 | 210 | 0 | 1 | 40 |

| EV20-004 | 61 | F | 19 | Poor-quality NOS | 387/490 | +380 | 1,020 | 70 | 19 | 12 | 8 |

| EV20-005 | 55 | F | 31 | Not offered by OPO | 460/448 | +607 | 120 | 51 | 15 | 29 | 5 |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; DCD = donor after cardiac death; ID = identifier; NA = not available; NOS = not otherwise specified; OPO = organ procurement organization; T0 = 0-hour time point; T6 = 6-hour time point.

Figure 1.

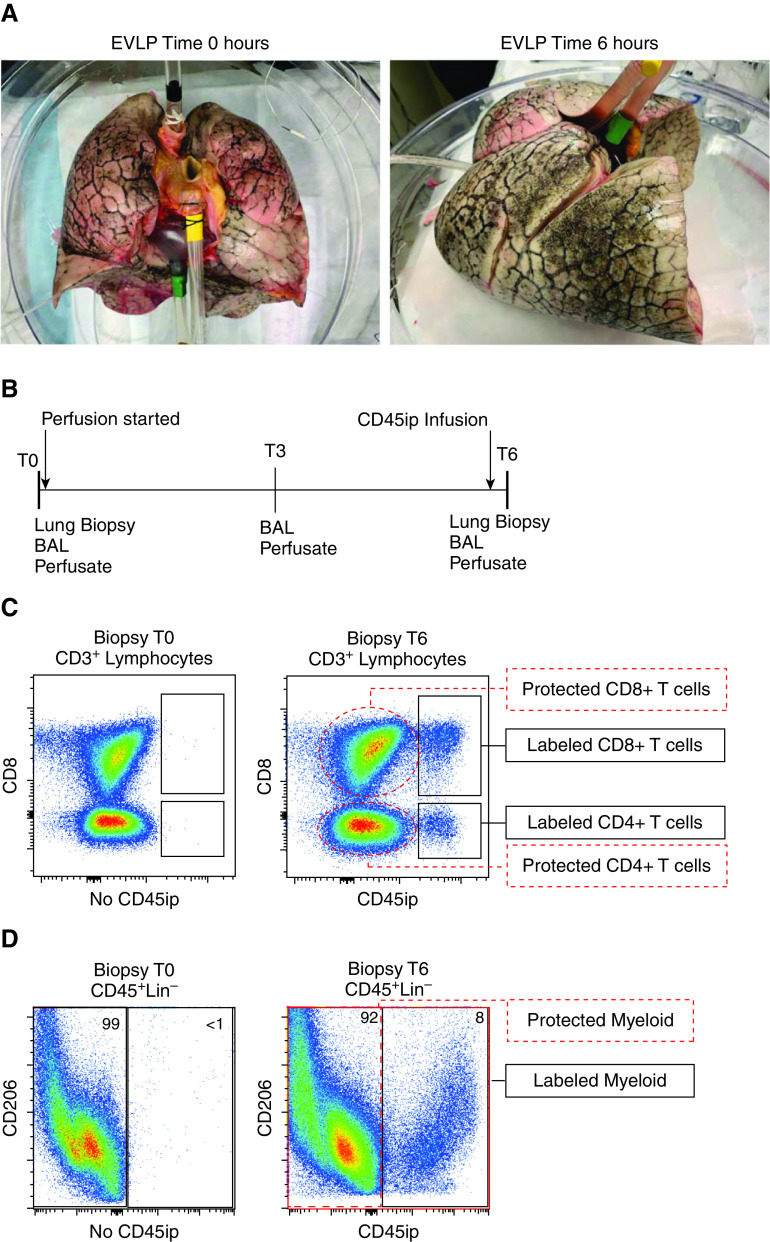

Ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) to isolate tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM) and lung-resident macrophages (MLR). Experimental model of isolating human lung TRM and MLR using 6 hours of EVLP and an intraperfusate-labeled CD45 (CD45ip) antibody: (A) human lungs before (left) and after (right) 6 hours of EVLP. (B) Study timeframe showing timing of sample collection and labeled antibody administration 20 minutes before the 6-hour time point (T6) of EVLP. (C) Representative flow-cytometric plot of live CD3+ lymphocytes taken from lung biopsy specimens at the 0-hour time point (T0; left) where no CD45ip antibody is present and at T6 (after 20 min of intraperfusate antibody circulation). T cells in communication with the perfusate are positive for the antibody (black rectangles), defined as “labeled” T cells, whereas the majority of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are protected from intraperfusate labeling (red dashed ovals) and labeled “protected.” (D) Representative flow-cytometric plot of live, CD45+, Lin− singlets taken from lung biopsy specimens at T0 (left) and T6 (right). Those cells positive for CD45ip antibody are identified as labeled myeloid cells, and those absent of CD45ip antibody are identified as protected myeloid cells. Lin− = CD3, CD19, and CD56 lineage–negative.

Labeling of Passenger Lymphocytes

After 5 hours and 40 minutes of EVLP, 500 µl of conjugated antihuman CD45 antibody expanded in 20 ml of PBS was injected into the perfusate in the cannula sutured to the pulmonary artery (Figures E1A and E1B). This antibody was allowed to circulate in the perfusate for 20 minutes, and then the lungs were removed from the perfusate return cannula, allowing active removal of the remaining perfusate in the lung by the draining cannula. Multiparameter flow cytometry was used to differentiate T cells (Figure 1C), myeloid cells (Figure 1D), B cells, and CD56+ lymphocytes (Figure E2) in communication with the perfusate (labeled) and those not in communication with the perfusate (protected).

Isolation of Single-Cell Suspensions and Supernatant

Supernatant from BAL and perfusate samples was stored immediately in a −80 freezer. Lung biopsy specimens were mechanically digested in the presence of enzymatic digestion media (RPMI + 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS], 100 mg/ml of collagenase D, 10 mg/ml of DNase, 100 mg/ml of trypsin inhibitor, and penicillin–streptomycin–l-glutamine) using scissors and then using gentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec). Each sample was then incubated in a warm shaker for 1.5 hours, followed by a repeated use of gentleMACS Dissociator, and then passed through a metal strainer: a 100-µm strainer and a 70-µm strainer. Samples were washed with complete RPMI (RPMI + 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin–l-glutamine) and immediately stained and analyzed for flow cytometry using the protocol below or reexpanded in freeze media and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Flow Cytometry and Cell Sorting

Single-cell suspensions were stained in 200 µl of fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) buffer (PBS + 1% FBS) at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells per tube. Five microliters of Human Trustain FcX (catalog number 422302; BioLegend) was added to each tube for 10 minutes before staining. Cell-surface staining was performed for 30–60 minutes while covered at room temperature in FACS buffer. Cells were then fixed with eBioscience Intracellular Fixation and Permeabilization Buffer Set (Invitrogen) for 1 hour on ice. Intracellular staining was performed in the presence of permeabilization buffer at room temperature for 30–60 minutes. Flow cytometry was performed on a Cytek Aurora spectral flow cytometer (Cytek Biosciences). The gating strategy for the differentiation of T-cell phenotypes has been previously reported (13) (Figure E2). To obtain a broad comparison between labeled and protected cells of myeloid lineage, we started with live CD45+ cells that were lineage (CD3, CD56, CD19) negative. From this population, we identified alveolar macrophages, neutrophils, and lung dendritic cells on the basis of previously described gating techniques (14–16) and compared cell-surface markers broadly among all labeled and protected cells within that group. Cell sorting was performed on live cells using a BD FACSAria (BD Biosciences) flow cytometer. Alveolar macrophages were defined as live, CD45+CD14+CD206+ singlets. To allow controlled T-cell–receptor complex stimulation, T cells were sorted on the basis of CD4 and CD8, and not CD3, positivity. Table E1 provides a full list of all antibodies used for multiparameter flow cytometry.

In Vitro TRM Stimulation and Cytometric Bead Array

TRM stimulation was performed in 96-well plates, with 50,000–100,000 sorted TRM per well. TRM were cultured for 5–6 hours at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide as follows: TRM with media alone (RPMI + 10% FBS, and penicillin–streptomycin–l-glutamine), TRM with 1 µl/ml of monoclonal CD3, TRM with 1 µl/ml of monoclonal CD3 plus MLR at a ratio of 1:1, and TRM with CD2, CD3, and CD28 beads. All samples were incubated in the presence of 0.4 µl of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences), 0.4 µl of GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences), and 1 µl of CD107a. The gating strategy for cytokine production was based on clear demarcations noted on our positive and negative controls: CD2/3/28 stimulation and no CD2/3/28 stimulation, respectively. Supernatant from BAL fluid and perfusate at 0, 3, and 6 hours of EVLP were tested for cytokine content using the BD Cytometric Bead Array Human Th1/Th2 Cytokine Kit (catalog number 550749; BD Biosciences).

IHC and Imaging Analysis

Multiplexed IHC for CD3 and CD68 was performed on 5-µm sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung biopsy specimens obtained at 0 and time 6 hours of EVLP (see online supplement). Random sections of airway and the surrounding parenchyma were identified at 20× magnification using a Nikon Eclipse 55i microscope and captured as red–green–blue (RGB) images with a Nikon DS-Fi1 camera. As RGB images do not contain distinct color channels that facilitate digital image analysis, an unsupervised classification algorithm was developed to perform image color segmentation into CD3 (brown), CD68 (red), or nucleus (blue) bins. A Gaussian mixture model (17) was used for pixel classification because it segments the nonspherical RGB clusters more accurately than does K-means clustering. The classification algorithm was trained on a random sample of pixel RGB values from the entire data set and was subsequently used to determine the probability that a given pixel represents TRM (brown, CD3), MLR (red, CD68), or nuclei (blue). The color-segmented images were then prepared for digital analysis using an empirically derived image-processing sequence that consists of binary erosion, dilation, and hole filling (SciPy multidimensional image processing library). The centroids of the TRM, MLR, and nuclei were identified using the region props module from scikit-image. These centroids approximate the location and density of the relevant cell populations.

The R package “spatstat” (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was then used to determine the probability of spatial clustering among the centroids of TRM, MLR, and nuclei (18). Specifically, the inhomogeneous cross-type pair-correlation function (PCF) for a multiple-point pattern was used. This allows for robust cross-type spatial-clustering analysis of an inhomogeneous distribution that is expected for cells in the complex lung architecture. The PCFs were calculated to a radius of 50 mm between each pair of centroids. PCF values greater than 1 indicate statistically significant clustering between the paired centroids at the given radius. Thus, the area under the curve) values greater than 1 were calculated and used as a summary statistic to quantify spatial clustering, as previously described (19, 20).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.), R, and Python (Python Software Foundation). Because of the small sample size, we assumed that protein expression did not follow a normal distribution and used a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess for statistical significance of differential cell-surface and intracellular protein expression. A paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test was similarly used for all additional comparisons unless otherwise specified in the figure legends. Univariate linear regression was used to analyze the relationship between T-cell cytokine production and donor and experimental parameters. For all analyses, a two-tailed P value of <0.05 was the threshold used to determine statistical significance. Adobe Illustrator Creative Cloud 2017 was used for all graphics; unless otherwise specified in figure legend, error bars included in figures represent the mean and SD.

Results

EVLP Effectively Isolates Human-Lung T Cells with a TRM Phenotype

We set out to establish whether EVLP could be used to effectively isolate human lung TRM and MLR for study. Explanted human lungs from research-consenting organ donors underwent EVLP for 6 hours (Figure 1A and Table 1). At 5 hours and 40 minutes, a CD45-conjugated antibody was administered into the perfusate and allowed to circulate for 20 minutes before lung biopsy (Figures 1A and 1B and E1A and E1B). By comparing in vitro with ex vivo CD45 labeling, we were able to differentiate immune cells protected from the circulation, herein referred to as “protected” cells, from those in active communication with the circulation, herein referred to as “labeled” cells. The persistence of labeled lymphocytes varied between lungs, with percentages as high as 29% for labeled CD8+ T cells and 19% for labeled CD4+ T cells (Table 1). Among these eight EVLP lungs, preliminary univariate analysis shows that the proportion of labeled CD4+ and CD8+ T cells did not correlate with cold ischemia time before EVLP, donor body mass index (BMI), donor age, or pulmonary edema (as measured by weight increase over 6 h).

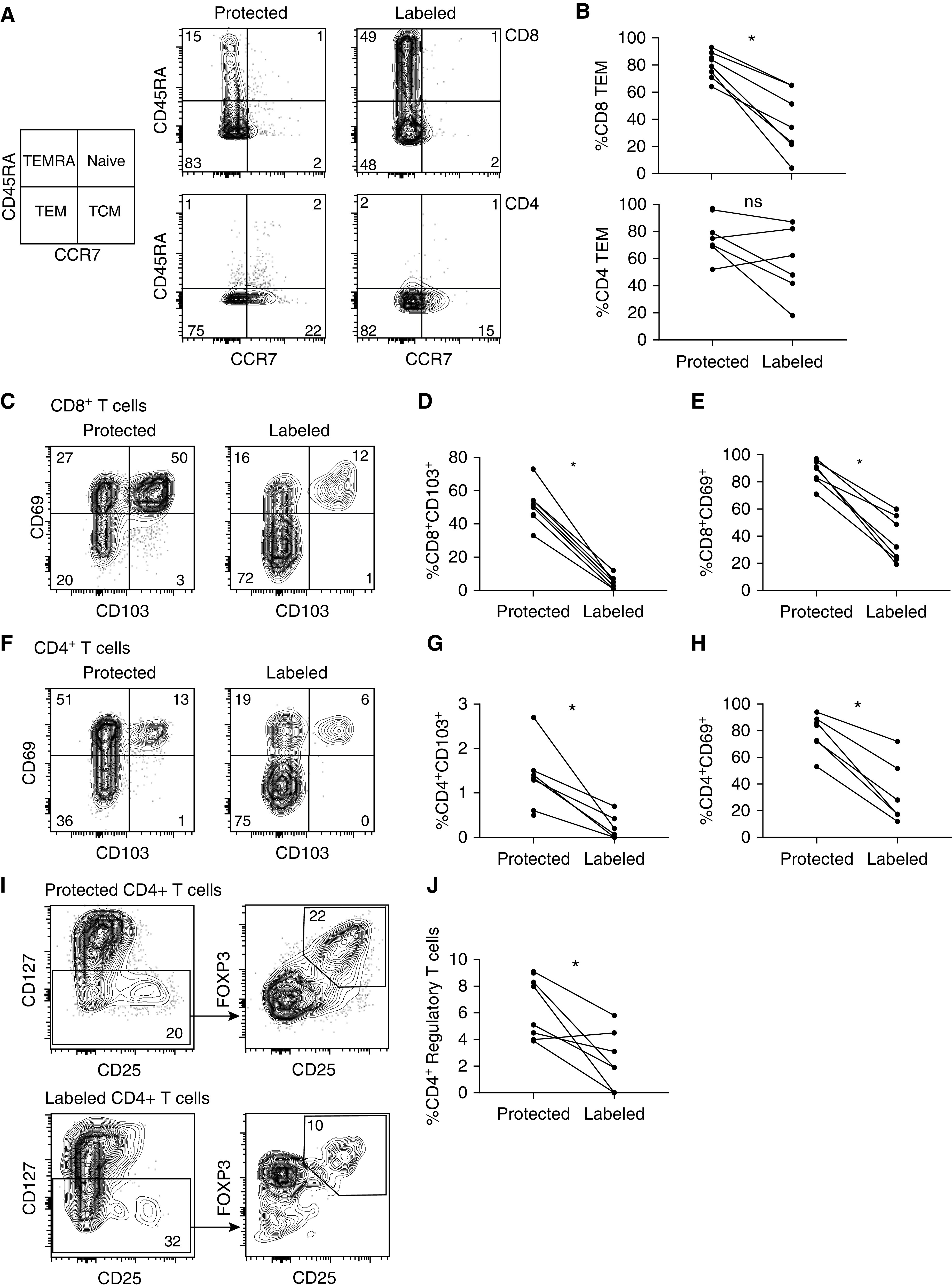

Protected CD8+ T cells were composed of a higher proportion of effector memory T cells (TEM; CCR7−CD45RA−); both protected and labeled CD4+ T cells were composed predominantly of TEM and central memory T cells (CCR7+CD45RA−), with very few naive cells (CCR7+CD45RA+) in either group (Figures 2A and 2B). Lung TRM showed significantly increased expression of the canonical cell-surface markers of tissue residency, CD103 and CD69 (Figures 2C–2H). In addition, CD8+ TRM showed increased expression of core residency marker integrin α 1 (CD49a) and the immunomodulatory immunoglobulin superfamily member 2 protein, CD101 (Figures E3A and E3B) (21, 22). Protected CD4+ T cells had a higher proportion of regulatory T cells, defined as CD127loCD25+FOXP3+ cells (Figures 2I and 2J). There was a non–statistically significant trend toward an increased proportion of PD1 positivity among protected CD4+ and CD8+ T cells when compared with labeled cells (Figure E3C). These findings provide compelling evidence that EVLP is an effective means of isolating human TRM and that after 6 hours of EVLP, the majority of retained T cells are tissue-resident T cells.

Figure 2.

Protected T cells have increased canonical markers of tissue residency and include CD4+ regulatory T cells. (A) Subset composition of representative samples using flow cytometry to identify the phenotype on the basis of CCR7 and CD45RA cell-surface expression as TEM (CCR7−CD45RA−), TCM (CCR7+CD45RA−), naive T cells (CCR7+, CD45RA+), and TEMRA (CCR7−CD45RA+) from lung biopsy specimens taken at 6 hours of ex vivo lung perfusion. (B) Compiled data showing paired proportion of TEM for both CD8+ (top) and CD4+ (bottom) T cells

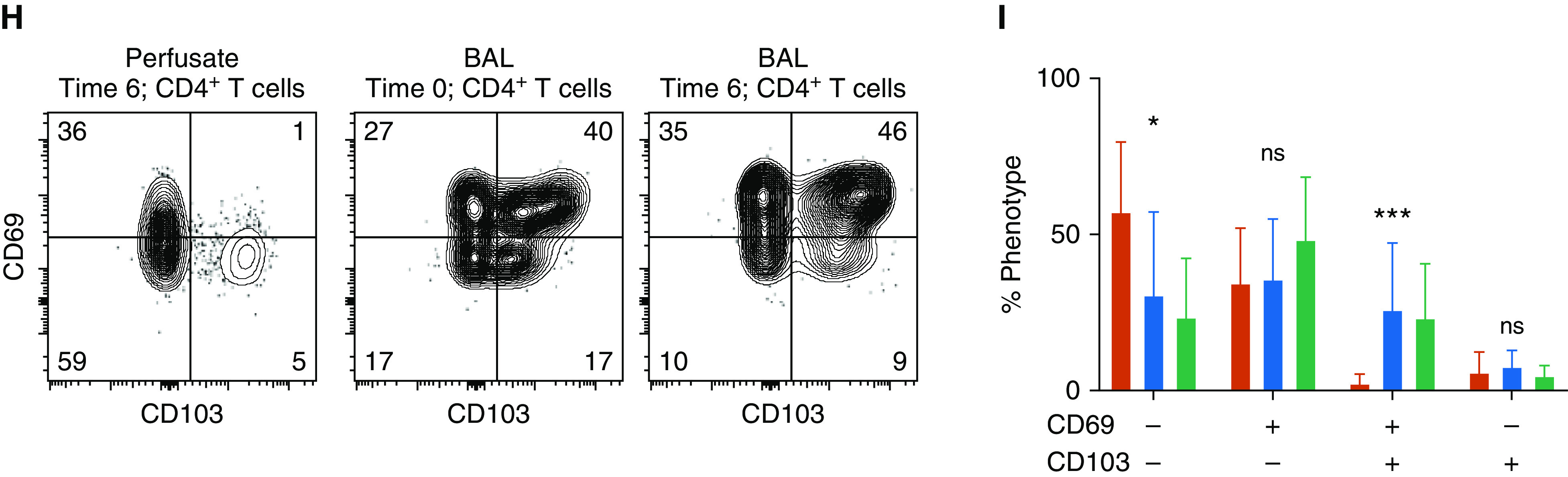

To validate that the alveolar compartment was protected from intraperfusate labeling and to identify the phenotype of lymphocytes egressing from the ex vivo lung or lung-draining lymphatics, we performed flow cytometry from cells obtained from BAL fluid and perfusate at 0 and time 6 hours of EVLP. Intraperfusate CD45 labeling successfully differentiated the perfusate and alveolar compartments of the EVLP circuit with almost no cross-contamination (Figure 3A). CD8+ T cells obtained from the perfusate had a higher proportion of naive and terminally differentiated effector T cells (CD45RA+CCR7−) and a reduced proportion of TEM than those obtained at either time point from the BAL fluid (Figures 3B and 3C). CD4+ T cells from the perfusate had a higher proportion of naive and central memory T cells and a lower proportion of TEM than those obtained from the BAL fluid (Figures 3D and 3E). The perfusate was devoid of CD8+CD69+CD103+ cells but had small populations of CD69+CD103− and CD69−CD103+ cells compared with cells obtained from the BAL fluid (Figures 3F and 3G). Most CD4+ T cells from the BAL fluid expressed CD69, as did a small population of those obtained from the perfusate. Similar to CD8+ T cells, the perfusate was devoid of CD69+CD103+ CD4+ T cells but had small populations of CD69+CD103− and CD69−CD103+ cells (Figures 3H and 3I).

Figure 3.

Differential phenotype of BAL-fluid and perfusate compartments. (A) Representative histograms displaying intraperfusate CD45 labeling by sample location and time for CD8+ T cells (far left), CD4+ T cells (middle), and alveolar macrophages (far right, defined as lineage-negative CD14+CD206+). (B and D) Representative flow-cytometric plots of CD8+ (B) and CD4+ (D) T-cell phenotypes based on CD45RA and CCR7 expression for samples obtained from perfusate at the 6-hour time point (T6; far left), from BAL fluid at the 0-hour time point (T0; middle), and from BAL fluid at T6 (far right). (C and E) Cumulative proportions of phenotypes for CD8+ (C) and CD4+ (E) T cells (bars represent means with SDs shown; N = 8; with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001 by Kruskal-Wallis test). (F and H) Representative flow-cytometric plots of canonical tissue-resident memory T-cell markers CD69 and CD103 for CD8+ (F) and CD4+ (H) T cells obtained from perfusate at 6 hours (far left), BAL fluid at 0 hours (middle), and BAL fluid at 6 hours (far right). (G and I) Cumulative proportions of CD69 and CD103 expression from CD8+ (G) and CD4+ (I) T-cell phenotypes (bars represent means with SDs shown; N = 8; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, and ***P < 0.0001 by Kruskal-Wallis test). + = positive; − = negative; CD45ip = intraperfusate-labeled CD45; max = maximum; ns = no statistically significant difference; TCM = central memory T cells; TEM = effector memory T cells; TEMRA = terminally differentiated effector T cells.

Over the course of 6 hours of EVLP, there was a non–statistically significant trend toward an increased proportion of CD8+ T cells expressing CD69 at 6 hours but no change in the proportion of CD4+ T cells expressing CD69 (Figure E4A). There was no change in the proportion of either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing MHC Class II (HLADR) (Figure E4B) or TNF receptor superfamily 7 (CD27) (Figure E4C). The proportion of regulatory T cells (CD4+CD127loCD25hiFOXP3+) did not change over the course of EVLP (Figure E4D). Together, these data suggest that EVLP enriches for a tissue-resident population of T cells, particularly among CD8+ T cells, and that lung TRM do not appear to upregulate markers of activation throughout the EVLP process.

Differential Compartmentalization of Alveolar Macrophages and Lung Dendritic Cells

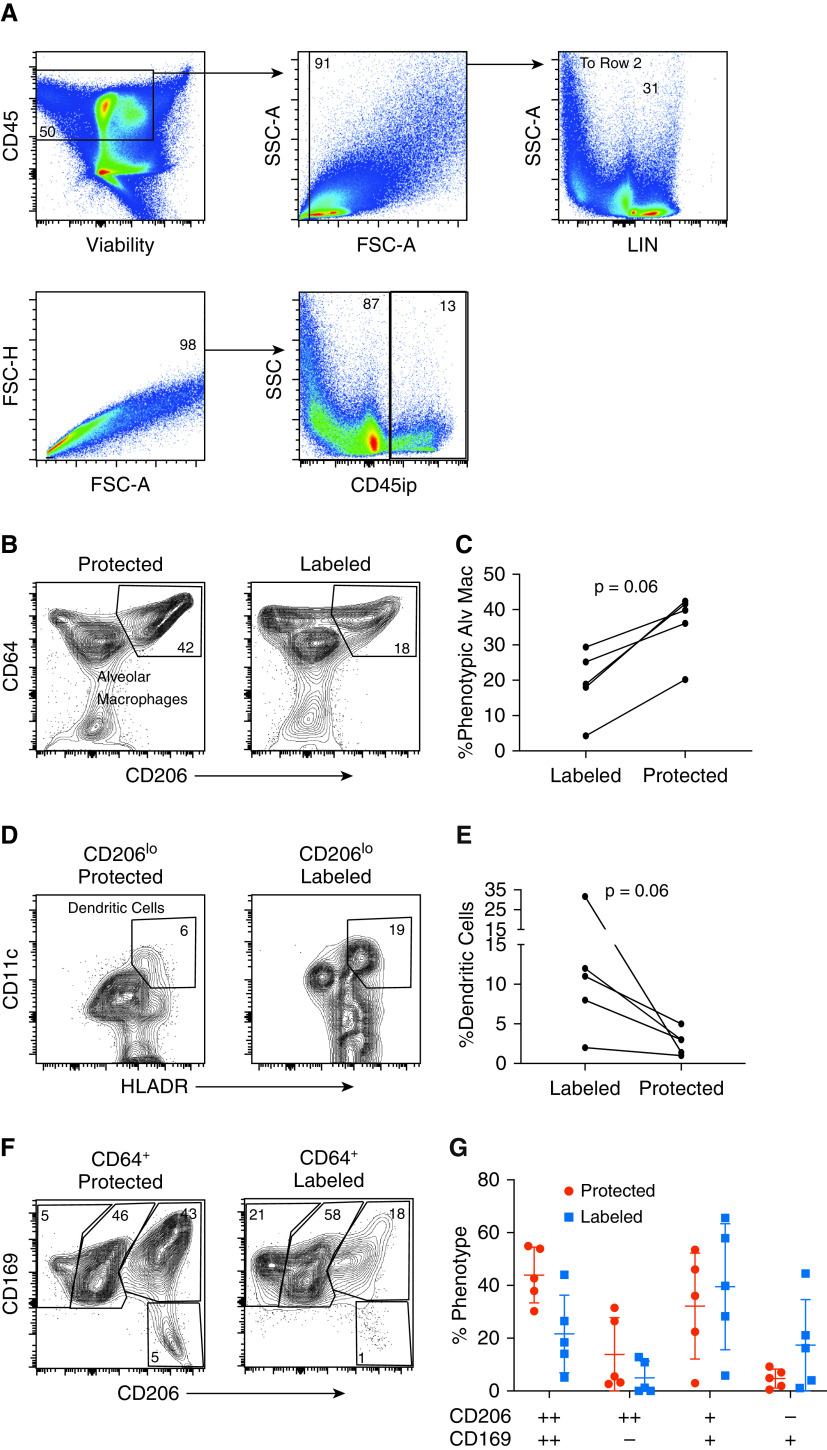

We next sought to compare the phenotypic differences between perfusate-labeled and protected cells of myeloid origin. This was accomplished by gating for live, CD45+ singlets that were lineage (CD3, CD19, CD56) negative (Figure 4A). As expected, the proportion of alveolar macrophages, defined as those cells with surface expression for both Fc-γ receptor 1 (CD64) and the mannose receptor (CD206), was much higher in the protected compartment than in the labeled compartment (Figure 4B). However, we found that the proportion of lung dendritic cells, defined as CD206loCD11c+HLADR+ cells, was consistently higher in the labeled population than in the protected population (Figure 4C). We then compared different populations of CD64+ cells on the basis of their expression of CD206 and sialoadhesin (CD169), which was based on prior studies using these markers to differentiate distinct populations of interstitial and alveolar macrophages (23). Although there was no statistically significant difference among these distinct populations, there was a trend toward increased CD169+CD206− myeloid cells among the labeled population and increased CD1692+CD2062+ cells among the protected population (Figure 4D). Protected cells of myeloid lineage, when compared with labeled cells, showed a trend toward an increased proportion positive for HLADR, PDL1 (programmed death-ligand 1), CD68, and CD1c (Figures E5A–E5F). Together, these results suggest a differential compartmentalization of lung cells of myeloid lineage, with alveolar macrophages being protected from perfusate and dendritic cells and CD169+CD206− macrophages being preferentially in communication with the perfusate. Finally, intraperfusate labeling identified a population of ex vivo CD45-unlabeled CD3−CD20+ (B cells) and CD56+ (natural killer) lymphocytes after 6 hours of EVLP, presumably tissue-resident B cells and natural killer cells (Figure E2).

Figure 4.

Differential compartmentalization of alveolar macrophages (Alv Mac) and lung dendritic cells. (A) Representative flow-cytometric plot isolating cells with a myeloid lineage (LIN). (B) Representative flow-cytometric plot identifying Alv Mac (defined as LIN−, CD64+CD206+) from lung biopsy specimens taken at 6 hours on the basis of the presence (right) or absence (left) of intraperfusate CD45 labeling (CD45ip). (C) Paired comparison of the proportion of Alv Mac from each cellular compartment (P = 0.06, n = 5). (D) Representative flow-cytometric plot identifying dendritic cells (defined as LIN CD206lo, HLADR+CD11c+) from lung biopsy specimens taken at 6 hours on the basis of the presence (right) or absence (left) of CD45ip. (E) Paired comparison of the proportion of Alv Mac from each cellular compartment (P = 0.06, n = 5). (F) Representative flow-cytometric plots of macrophage phenotypes based on CD169 and CD206 expression for protected (left) and labeled (right) CD64+ cells obtained from lung biopsy specimens at 6 hours. (G) Cumulative data (n = 5). ++ = strongly positive; + = weakly positive; − = negative; FSC-A = forward scatter area; FSC-H = forward scatter height; SSC = side scatter; SSC-A = side scatter area.

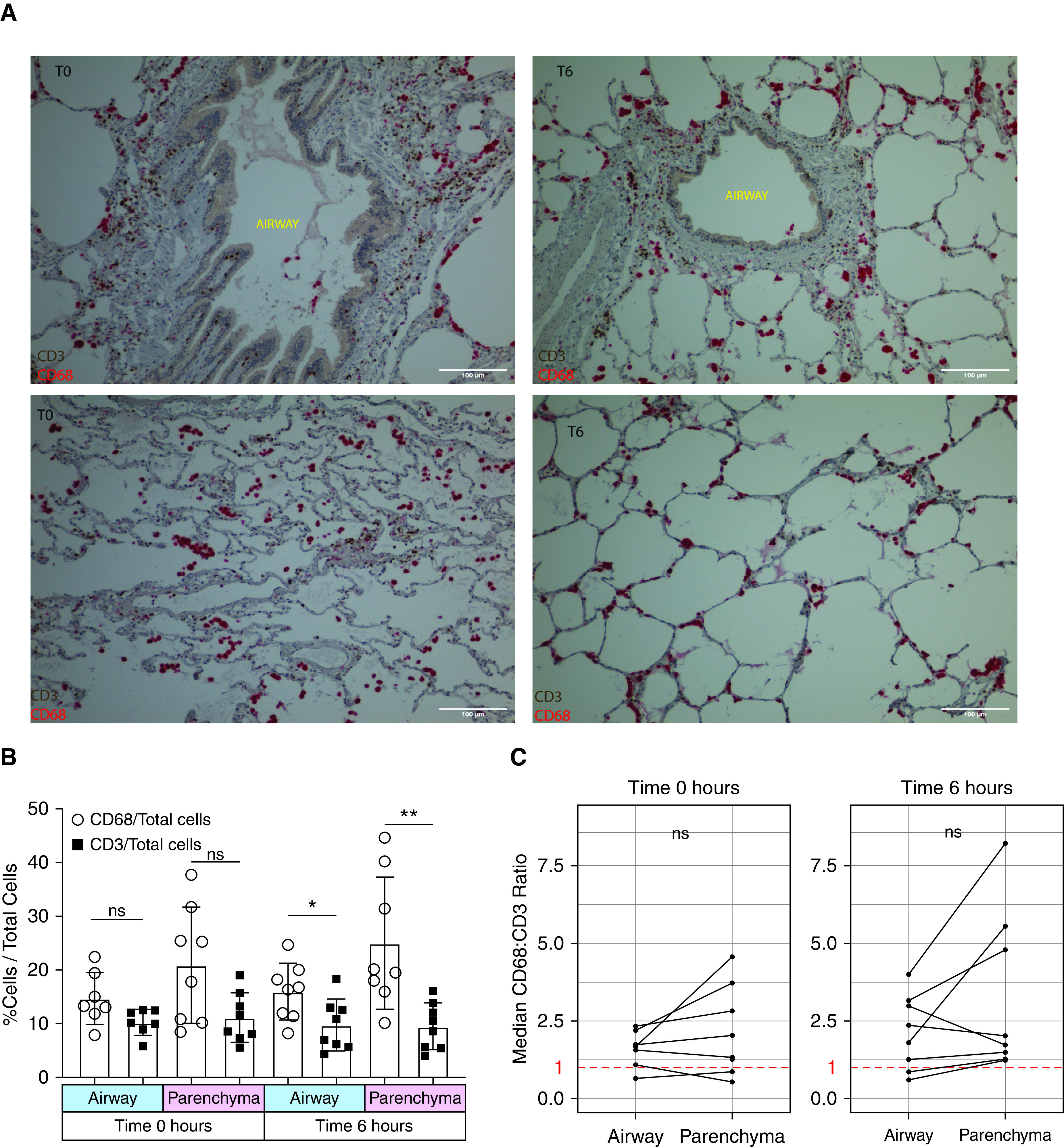

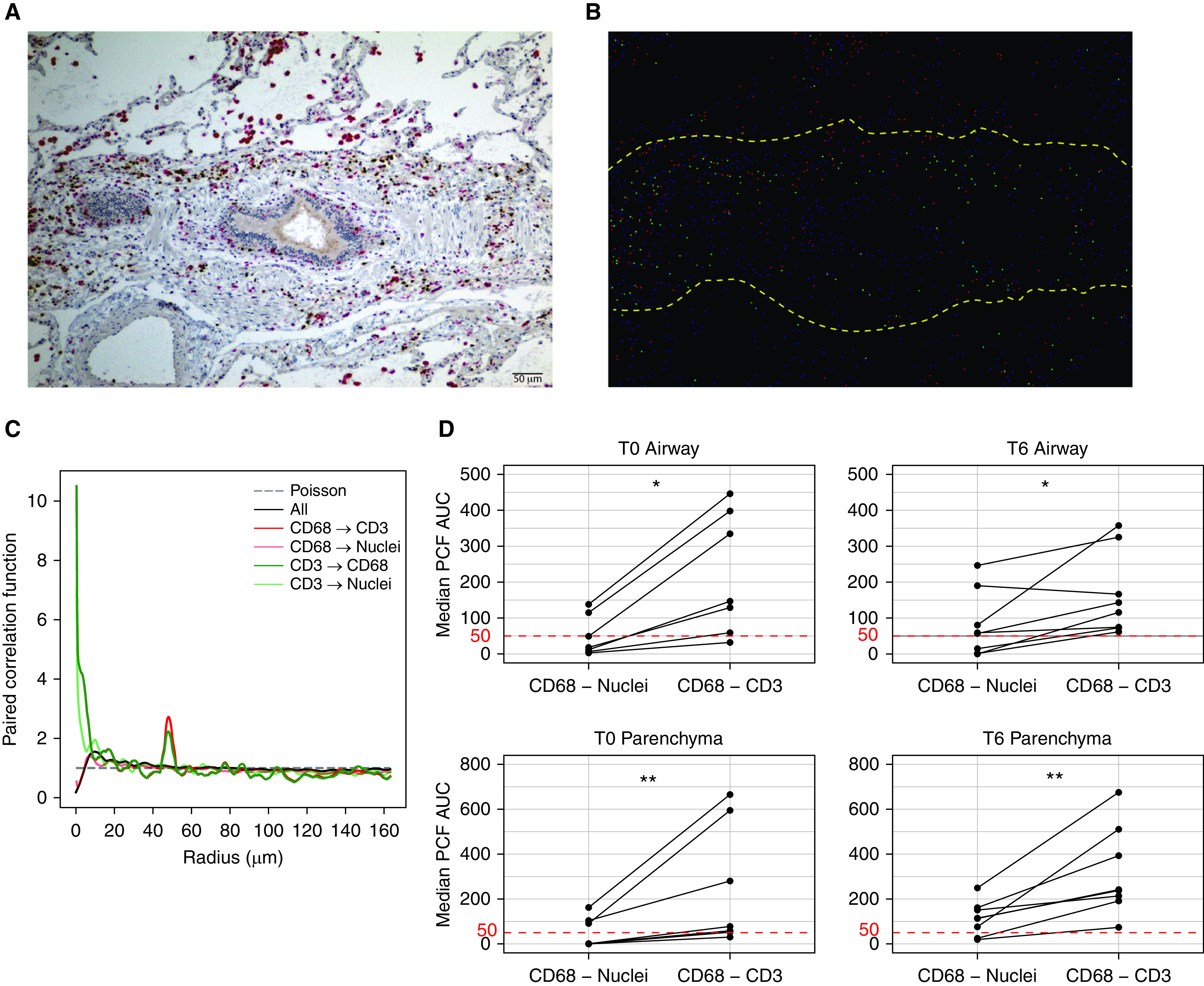

Lung TRM Cocluster with MLR Preferentially around the Airways

To investigate the spatial relationship between lung TRM and MLR, we performed multiplexed IHC on lung biopsy specimens taken at 0 and 6 hours of EVLP. At 0 hours, we found large clusters of CD3+ and CD68+ cells, mainly around the airways but occasionally within the parenchyma; after 6 hours of EVLP, the clusters of cells around the airways persisted (Figure 5A). At both 0 and 6 hours, monocytes were more prevalent than T cells everywhere in the lung, but to a much lesser degree around the airways (Figure 5B); CD3+ cells were present in near equal proportion to CD68+ cells around the airways (Figure 5C). Using a machine-learning algorithm, centroids of CD3+ and CD68+ from IHC were generated, and spatial relationships among cell types were compared with those of all cells (labeled nuclei) using a PCF (Figures 6A–6C). We found that CD3+ and CD68+ cells coclustered around the airways and parenchyma at all time points, but to a stronger degree after 6 hours of EVLP, with all airway and parenchyma sections meeting the algorithm’s threshold for coclustering (Figure 6D). These results suggest that TRM and MLR cocluster around both the airways and parenchyma of human lungs.

Figure 5.

Tissue-resident memory T cells are abundant in the lung and are mainly airway centered. Multiplexed immunohistochemistry of CD3 (brown) and CD68 (red) was performed on sections of lung obtained at the 0-hour time point (T0) and at the 6-hour time point (T6) of ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP). (A) Representative immunohistochemistry of the airway (top row) and lung parenchyma (bottom row) at T0 (left column) and after T6 of EVLP (right column). (B) Cumulative data showing the proportion of CD3+ and CD68+ cells of all nucleated cells by time of lung biopsy and area captured on imaging. “Airway” refers to small airways, and “parenchyma” refers to the adjacent lung parenchyma section devoid of airway or blood vessels. The median value per lung is included in each graph, with 8 lungs included (*P = 0.02 and **P = 0.008). (C) Cumulative data of CD68/CD3 ratio by anatomic location for T0 (left) and T6 (right) of EVLP. The median value of each lung is included, 8 lungs were included in the analysis, the orphaned parenchyma dot at 0 hours is due to the lack of an identifiable airway in one biopsy specimen at 0 hours, and the red dashed line equals a ratio of 1. Scale bars, 100 μm. ns = no statistically significant difference.

Figure 6.

Tissue-resident memory T cells and lung-resident macrophages colocalize within the lung, predominantly around the airways. (A) Representative multiplexed immunohistochemistry showing CD3 (brown) and CD68 (red) cells colocalizing around the airways. (B) Image converted to centroids (dots) using a machine-learning algorithm; yellow dashed lines outline the border of the airway. (C) Representative graph showing PCF (y-axis) across distances between centroids (x-axis) in micrometers for all cellular spatial relationships in one image; deviations above the Poisson distribution suggest colocalization at that radius (for reference, the diameter of a T cell is roughly 7 µm [49], and the diameter of a macrophage is variable but is on average 21 µm [50]). (D) Cumulative data comparing proximity between CD68+ cells and either nuclei or CD3+ cells within and around the small airways (top row) and lung parenchyma (bottom row) at T0 (left column) and T6 (right column) of ex vivo lung perfusion; for reference, an AUC value of 50 µm would represent a random Poisson distribution (*P = 0.02 and **P = 0.008; median value of 3–6 random airway and parenchyma sections included from 8 lungs; no T0 airway identified for one sample). Scale bar, 50 μm. AUC = area under the curve; PCF = pair-correlation function; T0 = 0-hour time point; T6 = 6-hour time point.

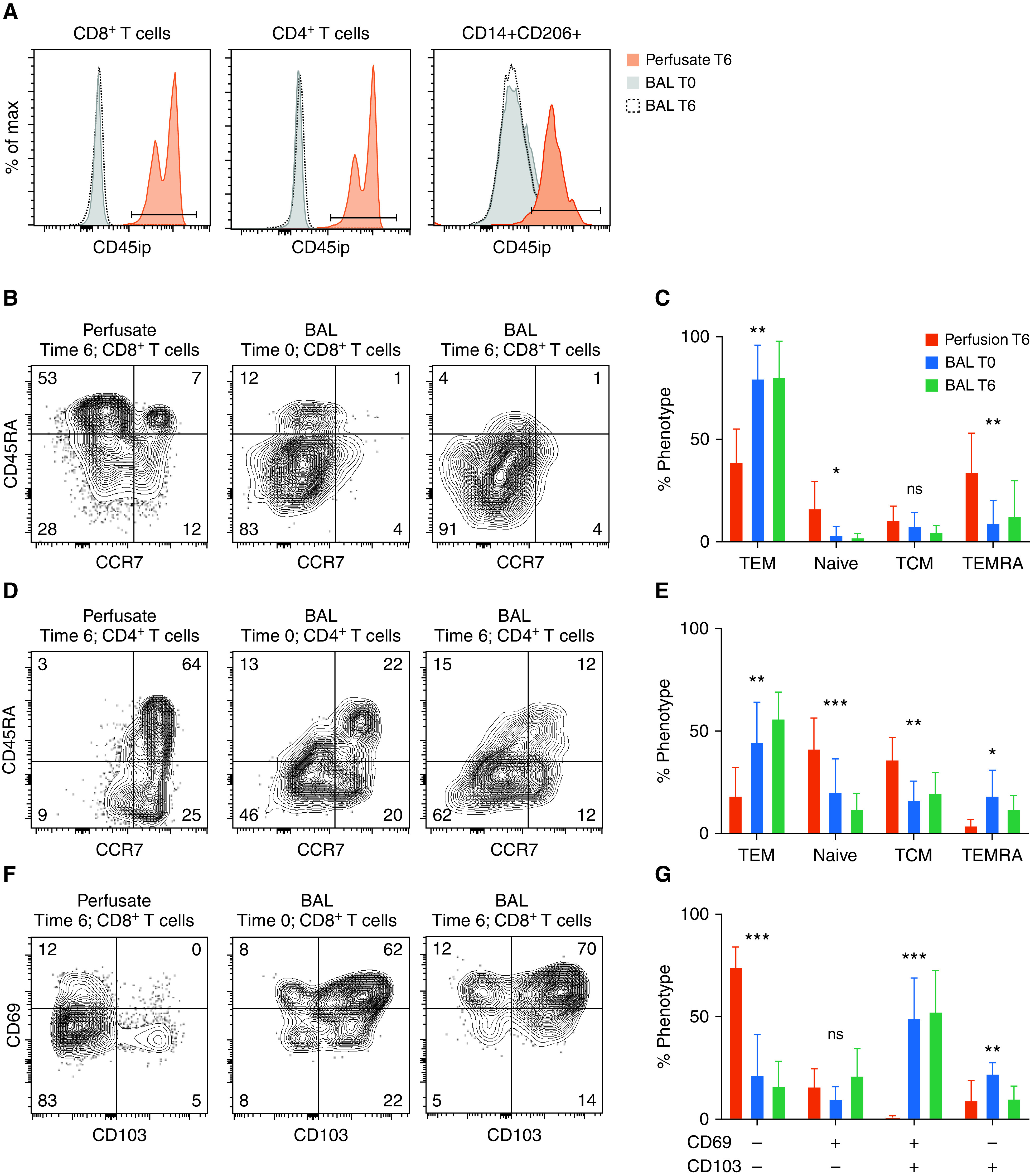

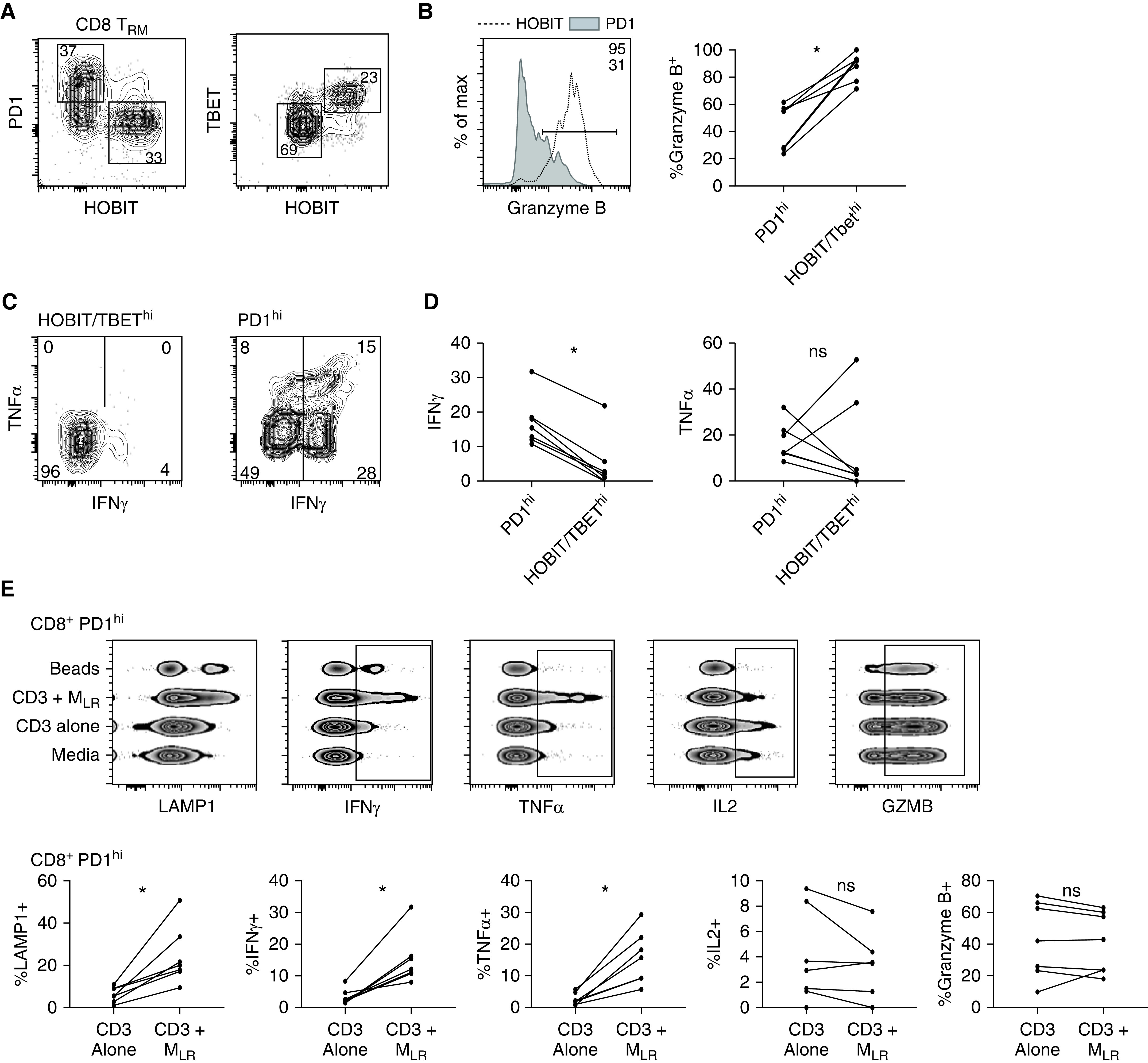

MLR Provide Costimulatory Signaling to Both CD4+ and CD8+ Lung TRM

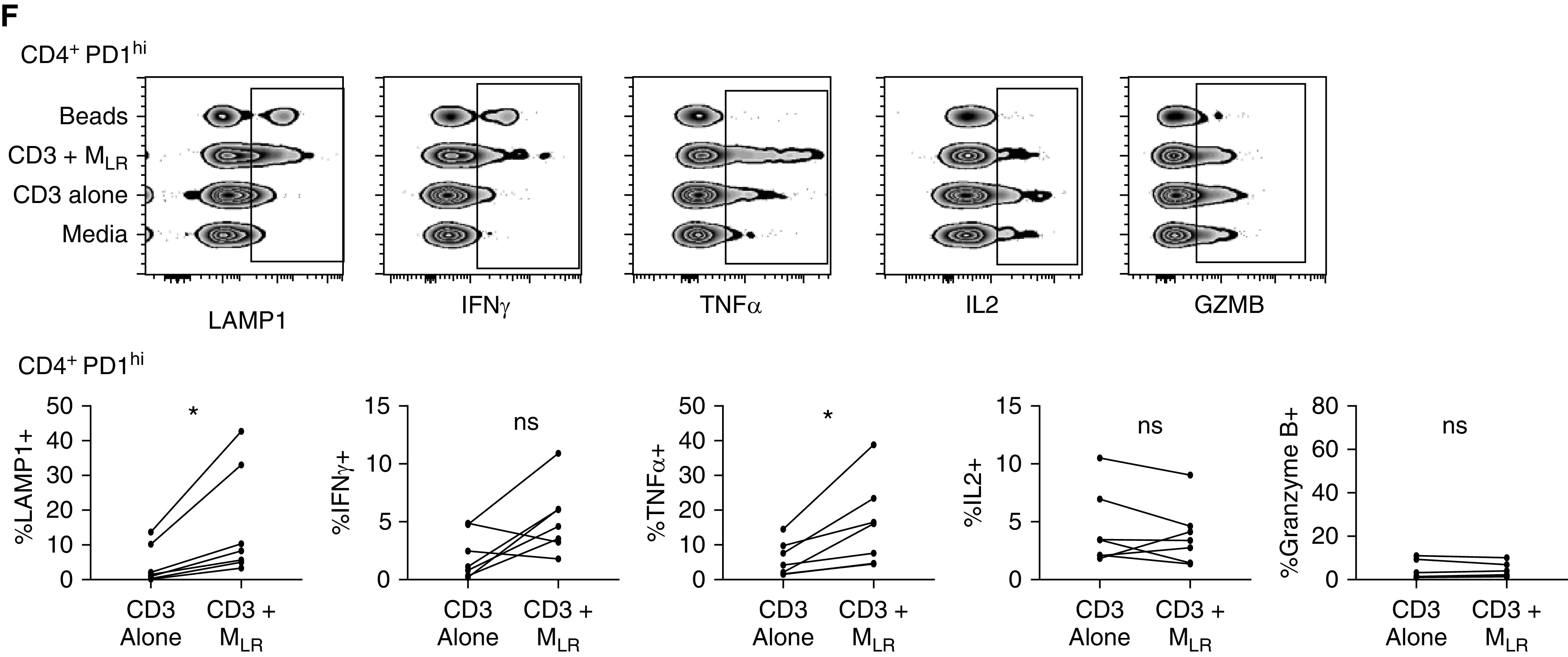

On the basis of our findings that CD3+ and CD68+ cells colocalize predominantly around the airways, we next set out to determine whether MLR impacted the effector function of TRM. We isolated live TRM (defined as live CD45+CD14− CD206−CD4/CD8+CD69+ cells) and MLR (defined as live CD45+CD14+CD206+ cells) from biopsy specimens taken at 6 hours (Figure E6). TRM were stimulated with monoclonal CD3 in the absence and presence of MLR at a 1:1 ratio. Regardless of the experimental condition, CD4+ and CD8+ TRM could be separated into PD1hi and PD1lo populations; PD1lo CD8+ TRM had increased expression of both the transcription factors HOBIT and TBET (Figure 7A). CD8+ TRM PD1hiHOBITlo (PD1hi) and HOBIT/TBEThiPD1lo (HOBIThi) populations were functionally distinct, with HOBIT/TBEThi showing high baseline granzyme B content that did not change with stimulation plus a poor effector response to stimulation and PD1hi showing preferential production of effector cytokines with stimulation and lower granzyme B content (Figures 7B–7D).

Figure 7.

Lung-resident macrophages (MLR) provide costimulatory signaling to tissue-resident memory T cells (TRM). CD69+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells were isolated from lung biopsy specimens after 6 hours of ex vivo lung perfusion using an influx cell sorter and were cultured with media alone (media), with monoclonal CD3 (CD3), with monoclonal CD3 plus MLR at an MLR/TRM ratio of 1:1 (CD3 + MLR), and with CD2/CD3/CD28 beads (beads). (A) Representative flow-cytometric plot of PD1 (programed cell death receptor 1) and HOBIT (left) and TBET (T-box transcription factor TBX21) and HOBIT (right) expression of CD8+ TRM cultured in media. (B) Representative histogram (left; horizontal line denotes positive gate) and paired cumulative frequency of intracellular GZMB (granzyme B) expression between PD1hi and HOBIThi or TBEThi CD8+ TRM (*P = 0.02, includes samples from 7 lungs). (C) Representative flow-cytometric plot of TNFα (tumor necrosis factor α) and IFNγ production among HOBIT or TBEThi (left) and PD1hi (right) CD8+ TRM isolated from lung biopsy specimens at 6 hours and cocultured with CD3 + MLR. (D) Composite data comparing the proportion of CD8+ TRM producing IFNγ (left) and TNFα (right) on the basis of expression of PD1 and either HOBIT or TBET (*P = 0.02, includes data from 7 lungs). (E) Representative comparison of cytokine production and LAMP1 expression for CD8+ PD1hi lung TRM under different stimulation conditions displayed as concatenated files from a single lung (top; rectangle outlines positive cells) and cumulative data (bottom; *P = 0.02; includes data from 7 lungs). (F) Representative comparison of cytokine production and LAMP1 expression for CD4+ PD1hi lung TRM under different stimulation conditions displayed as concatenated files from a single lung (top; rectangle outlines positive cells) and cumulative data (bottom; *P = 0.02; includes data from 7 lungs). max = maximum; ns = no statistically significant difference.

PD1hi TRM cultured in the presence of MLR produced increased amounts of IFNγ and TNFα and had increased cell-surface expression of CD107a when compared with stimulated with monoclonal CD3 alone. There was no difference in IL2, IL10, or granzyme B expression among groups (Figure 7E). CD4+ PD1hi TRM produced increased amounts of TNFα and had increased surface expression of CD107a when stimulated in the presence of MLR, with no difference in IL2 or granzyme B and a non–statistically significant increase in IFNγ (Figure 7F). Together, these findings suggest that MLR provide a costimulatory signal to PD1hi lung TRM after TCR-complex signaling.

To determine whether in vitro testing correlated with ex vivo cytokine production, we performed cytometric bead array on BAL supernatant and perfusate. We found that perfusate and BAL fluid had increasing concentrations of IL-10 over time and that TNFα had an initial rise at 3 hours followed by a trend toward downward concentration by 6 hours (Figure E7). Il-17 was increased in the perfusate over time, and there were negligible amounts of IFNγ found in either the BAL fluid or perfusate. This discordance between potential TRM cytokine production and actual cytokine content of the EVLP system suggests that injury induced by the EVLP system does not elicit an effector response in TRM.

Finally, we set out to identify preliminary evidence as to whether T-cell functional signatures were associated with any donor demographic or experimental parameters on univariate analysis. We compared the cytokine production and CD107a cell-surface expression of CD8+ and CD4+ TRM after stimulation with monoclonal CD3 in the presence of MLR with donor demographics and surrogate measures of lung injury. We found no relationship between donor BMI and T-cell function or degranulation (as measured by CD107a positivity; Figure E8A). We used reduced lung compliance at the end of 6 hours of EVLP as a surrogate of lung injury invoked either during ischemia time or by the process of EVLP. Decreased lung compliance was associated with a trend of increasing surface expression of CD107a, suggesting increased lysosomal degranulation with injury (Figure E8B). However, IL2 production did increase with increased lung compliance. There were no differences in cytokine production of CD4+ TRM based on donor age, sex, or BMI. Similarly, there were no effects of experimental parameters of EVLP on cytokine production of CD4+ TRM.

Discussion

Human lung TRM are instrumental in providing a rapid effector response to previously encountered inhaled pathogens and play a critical role in tumor immunosurveillance (24, 25). However, lung TRM also have the capacity to produce pathologic inflammation; for example, exposing mice to house dust mites leads to an accumulation of airway-centered, house dust mite–specific CD4+ TRM that is associated with increased airway resistance (26). Humans with asthma have been shown to have increased proportion of CD103+ T cells found in their BAL fluid (27, 28). Given the abundance of MLR, their adaptation to the local environment, and their vital role in maintaining lung homeostasis, it would seem reasonable that MLR play some role in guiding either the pro- or the antiinflammatory response of TRM (9, 10). Here, we present compelling evidence that MLR colocalize with TRM predominantly around the airways and that MLR enhance the effector response of lung TRM by providing costimulatory signaling. We show that PD1hi lung TRM are well poised to provide a rapid effector response on TCR-complex signal transduction in the presence of MLR.

Existing evidence suggests a two-way communication between T cells and macrophages. Effector CD8+ T cells assist in memory-macrophage formation after respiratory viral infection via IFNγ production (29). T-cell diapedesis is facilitated by macrophage nitric oxide production in lung cancers (30). TRM formation in the lung can be facilitated by priming from IL-10–producing monocytes via transforming growth factor β signaling (31). However, the means by which MLR modulate the effector response of TRM in human lungs remains incompletely characterized. In the pancreas, B7-H (PDL1) expressed on macrophages interacts with PD1 on pancreatic CD8+ TRM to modulate their effector function (20). We found that MLR rarely expressed PDL1, making this interaction less likely to play a major role in modulation of lung TRM. B7-1 and B7-2 expression on circulating monocytes was shown to provide costimulatory signaling to circulating lymphocytes via CD28 ligation (32). However, lung TRM have relatively low CD28 expression, and alveolar macrophages have diminished B7 expression when compared with circulating monocytes (32). Further investigation is required to determine the means of cosignaling. A few candidate pathways include both direct signaling via CD40–CD40L interaction (33) and paracrine effects of IL-12 release (34). Alternatively, this may represent an effect whereby macrophages augment T-cell effector function by enhancing TCR cross-linking by binding CD3 monoclonal antibody to their Fc receptor (35).

PD1 upregulation after chronic viral infection is associated with T-cell exhaustion, manifested as decreased capacity for proliferation and cytokine production (36). We found that PD1hi lung TRM conversely had enhanced effector function. We suspect, as previously reported (37), that PD1 expression represents a core immunomodulatory signature rather than exhaustion in TRM. This is consistent with studies showing that PD1 expression is associated with increased inflammation in joints (38) and that PD1 helps mediate a transient amount of exhaustion between infections, preventing pathologic inflammation (39). The transcription factors HOBIT and TBET are associated with the differentiation and regulation of cytotoxic effector function in CD8+ T cells (40–42). The role of HOBIT in formation and maintenance of TRM remains unclear. An experimental mouse model suggested that HOBIT plays a critical role in formation of TRM (43). However, subsequent studies showed that HOBIT-knockout mice are still capable of generating fewer cytotoxic TRM in the gut, manifested as decreased experimental colitis (44). Our results suggest that HOBIT expression is associated with a cytotoxic population of TRM, which would be consistent with a diminished extent of colitis previously described.

Like all means of studying human TRM, our findings are limited by experimental constraints. Longer time on EVLP may further enrich for protected immune populations; however, longer perfusion times diminish tissue viability. Furthermore, the mechanical stress of positive pressure ventilation and reactions to blood-surrogate perfusion may alter the resident immune cells in currently unknown ways. Stimulations of MLR and TRM were performed on frozen cells, with potential alteration of CD45 intraperfusate labeling. To isolate TRM and MLR from these frozen aliquots, we relied on surrogate markers of tissue residency from cells after 6 hours of EVLP; rare CD69+ passenger lymphocytes may have contaminated this population. The cytokine content of the BAL-fluid and perfusate compartments of lungs after 6 hours of EVLP did not correlate with the cytokine-production pattern found by stimulation of T cells in the presence of MLR. There are many possible explanations for this discrepancy that justify further investigation. The most likely is that interactions of TRM and MLR may require the presentation of a “nonself” cognate antigen to stimulate an effector response (45, 46). This possibility implies that “danger” signaling in the absence of a nonself peptide is insufficient to stimulate this resident immune network (47). The EVLP model provides a unique methodology for studying these complex interactions in human lungs, as well as for investigating the response of human resident immune populations to various challenges, via either inhalations or intraperfusate.

In this study, we found differential compartmentalization between alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells, which were predominantly found in the protected and labeled compartments, respectively. Our functional analyses focused on the impact of alveolar macrophages on the effector function of lung TRM, which fails to address the role that interstitial macrophages may play in modulating the tissue-resident adaptive immune response in the lung. Interstitial macrophages remain incompletely characterized in the human lung (48), predominantly because of experimental constraints and the more readily available sampling of alveolar macrophages. It is unclear whether interstitial macrophages would be removed from the circulation to the same degree as alveolar macrophages, making intraperfusate labeling a currently inadequate means of characterizing the interstitial macrophage population. However, we did find CD169+CD206− macrophages to preferentially occupy the labeled compartment, suggesting that this population is more closely localized to the circulation. Future attempts to more accurately characterize interstitial macrophages with EVLP as a population distinct from alveolar macrophages, will likely require the development of an intraperfusate labeling system that can withstand fixation and paraffin embedding, enabling spatial imaging analysis.

In conclusion, EVLP is an effective means of isolating TRM and MLR for further study. TRM and MLR colocalize within the human lung, predominantly around airways, and MLR provide costimulatory signaling after TCR-complex signal transduction.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the families of the organ donors as well as the Center for Organ Recovery & Education for procurement of lungs from research-consenting organ donors.

Footnotes

Supported by a Parker B. Francis Foundation Award grant (M.E.S.), by NIH grant 5 R01 HL123766-04 (M.R.), and by grant money provided by XVIVO Perfusion (P.S.).

Author Contributions: M.E.S., J.P., J.M., M.R., and P.S. provided substantial contributions to the conception of this work. J.S., K.N., T.H., and M.F. performed lung acquisition and performed the ex vivo lung perfusion. M.M.M. designed and executed the machine-learning algorithm to analyze immunohistochemistry samples and performed imaging analysis. A.C. acquired immunohistochemistry samples and assisted in flow cytometry. N.M. performed the cytometric bead array. M.E.S. performed all flow cytometry and cell stimulations, performed functional assays and statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Correspondence and requests for reprints should be addressed to Mark E. Snyder, M.D., University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Montefiore Hospital, NW628, 3459 Fifth Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213. E-mail: snyderme2@upmc.edu.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2403OC on December 11, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Teijaro JR, Turner D, Pham Q, Wherry EJ, Lefrançois L, Farber DL. Cutting edge: tissue-retentive lung memory CD4 T cells mediate optimal protection to respiratory virus infection. J Immunol. 2011;187:5510–5514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu T, Hu Y, Lee YT, Bouchard KR, Benechet A, Khanna K, et al. Lung-resident memory CD8 T cells (TRM) are indispensable for optimal cross-protection against pulmonary virus infection. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:215–224. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0313180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turner DL, Bickham KL, Thome JJ, Kim CY, D’Ovidio F, Wherry EJ, et al. Lung niches for the generation and maintenance of tissue-resident memory T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:501–510. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cho A, Bradley B, Kauffman R, Priyamvada L, Kovalenkov Y, Feldman R, et al. Robust memory responses against influenza vaccination in pemphigus patients previously treated with rituximab. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e93222. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McMaster SR, Wilson JJ, Wang H, Kohlmeier JE. Airway-resident memory CD8 T cells provide antigen-specific protection against respiratory virus challenge through rapid IFN-γ production. J Immunol. 2015;195:203–209. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jozwik A, Habibi MS, Paras A, Zhu J, Guvenel A, Dhariwal J, et al. RSV-specific airway resident memory CD8+ T cells and differential disease severity after experimental human infection. Nat Commun. 2015;6:10224. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ogongo P, Porterfield JZ, Leslie A. Lung tissue resident memory T-cells in the immune response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Immunol. 2019;10:992. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stone KC, Mercer RR, Gehr P, Stockstill B, Crapo JD. Allometric relationships of cell numbers and size in the mammalian lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:235–243. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guilliams M, Thierry GR, Bonnardel J, Bajenoff M. Establishment and maintenance of the macrophage niche. Immunity. 2020;52:434–451. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hussell T, Bell TJ. Alveolar macrophages: plasticity in a tissue-specific context. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:81–93. doi: 10.1038/nri3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Snyder ME, Sembrat J, Noda K, Harano T, Reck dos Santos PA, Pilewski J, et al. Ex-vivo lung perfusion provides a novel means of studying tissue resident immune populations in human lungs [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:A1001. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Weathington NM, Álvarez D, Sembrat J, Radder J, Cárdenes N, Noda K, et al. Ex vivo lung perfusion as a human platform for preclinical small molecule testing. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e95515. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.95515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Snyder ME, Finlayson MO, Connors TJ, Dogra P, Senda T, Bush E, et al. Generation and persistence of human tissue-resident memory T cells in lung transplantation. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:eaav5581. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aav5581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yu YR, Hotten DF, Malakhau Y, Volker E, Ghio AJ, Noble PW, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of myeloid cells in human blood, bronchoalveolar lavage, and lung tissues. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:13–24. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0146OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Desch AN, Gibbings SL, Goyal R, Kolde R, Bednarek J, Bruno T, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of mononuclear phagocytes in nondiseased human lung and lung-draining lymph nodes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:614–626. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201507-1376OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Granot T, Senda T, Carpenter DJ, Matsuoka N, Weiner J, Gordon CL, et al. Dendritic cells display Subset and tissue-specific maturation dynamics over human life. Immunity. 2017;46:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pedregosa F, Veroquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J Mach Learn Res. 2011;12:2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baddeley A, Turner R. spatstat: an R package for analyzing spatial point patterns. J Stat Softw. 2005;12:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao J, Chen AX, Gartrell RD, Silverman AM, Aparicio L, Chu T, et al. Immune and genomic correlates of response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in glioblastoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:462–469. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0349-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weisberg SP, Carpenter DJ, Chait M, Dogra P, Gartrell-Corrado RD, Chen AX, et al. Tissue-resident memory T cells mediate immune homeostasis in the human pancreas through the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Cell Rep. 2019;29:3916–3932. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schey R, Dornhoff H, Baier JL, Purtak M, Opoka R, Koller AK, et al. CD101 inhibits the expansion of colitogenic T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1205–1217. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheuk S, Schlums H, Gallais Sérézal I, Martini E, Chiang SC, Marquardt N, et al. CD49a expression defines tissue-resident CD8+ T cells poised for cytotoxic function in human skin. Immunity. 2017;46:287–300. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bharat A, Bhorade SM, Morales-Nebreda L, McQuattie-Pimentel AC, Soberanes S, Ridge K, et al. Flow cytometry reveals similarities between lung macrophages in humans and mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54:147–149. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2015-0147LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oja AE, Piet B, van der Zwan D, Blaauwgeers H, Mensink M, de Kivit S, et al. Functional heterogeneity of CD4+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes with a resident memory phenotype in NSCLC. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2654. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Djenidi F, Adam J, Goubar A, Durgeau A, Meurice G, de Montpréville V, et al. CD8+CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are tumor-specific tissue-resident memory T cells and a prognostic factor for survival in lung cancer patients. J Immunol. 2015;194:3475–3486. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Turner DL, Goldklang M, Cvetkovski F, Paik D, Trischler J, Barahona J, et al. Biased generation and in situ activation of lung tissue-resident memory CD4 T cells in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2018;200:1561–1569. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hirosako S, Goto E, Tsumori K, Fujii K, Hirata N, Ando M, et al. CD8 and CD103 are highly expressed in asthmatic bronchial intraepithelial lymphocytes. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;153:157–165. doi: 10.1159/000312633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Smyth LJ, Eustace A, Kolsum U, Blaikely J, Singh D. Increased airway T regulatory cells in asthmatic subjects. Chest. 2010;138:905–912. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yao Y, Jeyanathan M, Haddadi S, Barra NG, Vaseghi-Shanjani M, Damjanovic D, et al. Induction of autonomous memory alveolar macrophages requires T cell help and is critical to trained immunity. Cell. 2018;175:1634–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sektioglu IM, Carretero R, Bender N, Bogdan C, Garbi N, Umansky V, et al. Macrophage-derived nitric oxide initiates T-cell diapedesis and tumor rejection. OncoImmunology. 2016;5:e1204506. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1204506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thompson EA, Darrah PA, Foulds KE, Hoffer E, Caffrey-Carr A, Norenstedt S, et al. Monocytes acquire the ability to prime tissue-resident T cells via IL-10-mediated TGF-β release. Cell Rep. 2019;28:1127–1135, e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Toews GB, Vial WC, Dunn MM, Guzzetta P, Nunez G, Stastny P, et al. The accessory cell function of human alveolar macrophages in specific T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 1984;132:181–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schoenberger SP, Toes REM, van der Voort EIH, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–483. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shu U, Kiniwa M, Wu CY, Maliszewski C, Vezzio N, Hakimi J, et al. Activated T cells induce interleukin-12 production by monocytes via CD40-CD40 ligand interaction. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1125–1128. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dixon JFP, Law JL, Favero JJ. Activation of human T lymphocytes by crosslinking of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies. J Leukoc Biol. 1989;46:214–220. doi: 10.1002/jlb.46.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wherry EJ. T cell exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:492–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kumar BV, Ma W, Miron M, Granot T, Guyer RS, Carpenter DJ, et al. Human tissue-resident memory T cells are defined by core transcriptional and functional signatures in lymphoid and mucosal sites. Cell Rep. 2017;20:2921–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.08.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Petrelli A, Mijnheer G, Hoytema van Konijnenburg DP, van der Wal MM, Giovannone B, Mocholi E, et al. PD-1+CD8+ T cells are clonally expanding effectors in human chronic inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:4669–4681. doi: 10.1172/JCI96107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Z, Wang S, Goplen NP, Li C, Cheon IS, Dai Q, et al. PD-1hi CD8+ resident memory T cells balance immunity and fibrotic sequelae. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:eaaw1217. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Intlekofer AM, Takemoto N, Wherry EJ, Longworth SA, Northrup JT, Palanivel VR, et al. Effector and memory CD8+ T cell fate coupled by T-bet and eomesodermin. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1236–1244. doi: 10.1038/ni1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sullivan BM, Juedes A, Szabo SJ, von Herrath M, Glimcher LH. Antigen- driven effector CD8 T cell function regulated by T-bet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:15818–15823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2636938100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vieira Braga FA, Hertoghs KM, Kragten NA, Doody GM, Barnes NA, Remmerswaal EB, et al. Blimp-1 homolog Hobit identifies effector-type lymphocytes in humans. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45:2945–2958. doi: 10.1002/eji.201545650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mackay LK, Minnich M, Kragten NA, Liao Y, Nota B, Seillet C, et al. Hobit and Blimp1 instruct a universal transcriptional program of tissue residency in lymphocytes. Science. 2016;352:459–463. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zundler S, Becker E, Spocinska M, Slawik M, Parga-Vidal L, Stark R, et al. Hobit- and Blimp-1-driven CD4+ tissue-resident memory T cells control chronic intestinal inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:288–300. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Oberbarnscheidt MH, Zeng Q, Li Q, Dai H, Williams AL, Shlomchik WD, et al. Non-self recognition by monocytes initiates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3579–3589. doi: 10.1172/JCI74370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Holt PG. Antigen presentation in the lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:S151–S156. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.supplement_3.15tac2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liegeois M, Legrand C, Desmet CJ, Marichal T, Bureau F. The interstitial macrophage: a long-neglected piece in the puzzle of lung immunity. Cell Immunol. 2018;330:91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tasnim H, Fricke GM, Byrum JR, Sotiris JO, Cannon JL, Moses ME. Quantitative measurement of naïve T cell association with dendritic cells, FRCs, and blood vessels in lymph nodes. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1571. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Krombach F, Münzing S, Allmeling AM, Gerlach JT, Behr J, Dörger M. Cell size of alveolar macrophages: an interspecies comparison. Environ Health Perspect. 1997;105:1261–1263. doi: 10.1289/ehp.97105s51261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]