Abstract

Trifluridine (FTD)/tipiracil (TPI) plus bevacizumab (Bev) is a promising late-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Although chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN) is a well-known predictor of FTD/TPI efficacy, whether CIN is a predictive marker of efficacy for FTD/TPI + Bev remains unclear. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the clinical outcomes of FTD/TPI + Bev and the predictive markers of its efficacy. Clinical data of patients with mCRC who received FTD/TPI + Bev at the Cancer Institute Hospital between January 2017 and August 2020 were retrospectively collected. Disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS) and safety were assessed. In addition, subgroup analyses of prognostic and predictive efficacy markers were performed. In total, 94 patients (median age, 60.0 years; age range, 32–82 years; 37 men and 57 women) were included in the present study. The DCR was 44.7%, the median PFS time was 2.9 months (2.3–4.1 months) and the median OS time was 10.0 months (7.3–11.1 months). Grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment occurred in 27.7% of patients, which was significantly associated with a longer PFS time than those who did not develop CIN [3.8 months (2.3–8.4 months) vs. 2.7 months (1.8–4.0 months); P=0.008]. Furthermore, the DCR was higher in patients with grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment than those without CIN (61.5 vs. 38.2%; P=0.07). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment are independent predictors for a longer PFS time (P=0.01). Taken together, the results of the present study suggest that grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment are early predictors of the efficacy of FTD/TPI + Bev.

Keywords: trifluridine tipiracil, bevacizumab, colorectal cancer, chemotherapy-induced neutropenia, predictive factor

Introduction

Trifluridine (FTD)/tipiracil (TPI) are nucleoside antineoplastic agents that are used in 1:0.5 molar ratio as a novel oral treatment (1). FTD is an active anticancer agent that possibly mediates its effect by inducing DNA dysfunction through direct uptake into DNA after oral administration. TPI specifically inhibits thymidine phosphorylase, the enzyme that degrades FTD, increasing the bioavailability of FTD (1–3). FTD/TPI has a different mechanism of action from conventional antineoplastic agents such as 5-fluorouracil. Moreover, a preclinical study has shown the effect of FTD/TPI on tumors with low susceptibility to pyrimidine fluoride-based antineoplastic agents (4). Following a phase III trial comparing FTD/TPI monotherapy and best supportive care (BSC) (5,6), FTD/TPI was approved for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with refractory to conventional standard chemotherapy in Japan, the US, and the Europe Union (7–9). One of the predictive factors of FTD/TPI efficacy is chemotherapy-induced neutropenia (CIN), which is well known as the most common adverse event of this drug (10). The predictive nature of CIN is attributed to a dose-response relationship between FTD exposure and neutropenia, in agreement with the findings of a dose-escalation study that a higher rate of neutropenia at higher FTD and TPI doses implies greater drug efficacy (10). In addition, FTD/TPI plus bevacizumab (Bev) is an alternative treatment option as a third- or later-line chemotherapy for patients with mCRC, as this treatment is safe and leads to a higher disease control rate (DCR) and longer progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), than FTD/TPI monotherapy. Nevertheless, there are only a few phase I/II (11–13) or randomized phase II trials (14) investigating the efficacy of FTD/TPI + Bev. Moreover, because the PFS following this salvage-line treatment is still low, predictors of early treatment efficacy are important to help optimize treatment strategies; however, the efficacy predictors of FTD/TPI + Bev remain unclear. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes of FTD/TPI + Bev and to explore predictors of its efficacy.

Materials and methods

Patients

This is a retrospective cohort study in a single institute in Japan. Patients with mCRC who received FTD/TPI + Bev at the Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, from January 2017 to August 2020 were enrolled. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (Tokyo, Japan, registry number 2020-1017). The protocol was described on the hospital website, and subjects were provided the opportunity to opt-out; therefore, no additional consent was required from patients. All the data were readily available and not taken specifically for this study. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Treatment schedule

FTD/TPI (35 mg/m2) was administered orally twice daily, after breakfast and dinner, for 5 days a week for 2 weeks, followed by a 14-day rest, and then Bev (5 mg/kg) was administered via intravenous infusion for 30 min every 2 weeks. This treatment cycle was repeated every 4 weeks until tumor progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred or at the patient's request. Dose reductions and treatment discontinuations were performed owing to toxicity, disease progression, or based on the physician's decisions (11).

Study endpoints

Tumor response was assessed by computed tomography using the RECIST guidelines, v1.1. Complete response (CR) was defined as the complete disappearance of all detectable evidence of disease as determined using total body computed tomography. Partial response (PR) was defined as a minimum of 30% decrease in the sum of target lesion diameters. Stable disease (SD) was defined as everything between a 30% decrease and a 20% growth in tumor size. Progressive disease was defined as a minimum of 20% increase in the sum of target lesion diameters. Objective response rate (ORR) implied the proportion of patients who showed CR or PR to therapy, and DCR indicated the proportion of patients who showed CR, PR, or SD response to therapy. PFS was defined as the time from the first day of treatment to either the first objective evidence of disease progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time from the first day of treatment until the time of death. Toxicity was graded according to the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0, both within the first cycle and at all periods of treatment. Neutrophils were measured during the first cycle treatment or just before the initiation of second cycle treatment, which was defined as CIN within the first cycle of the treatment. We also evaluated the relationship between clinical outcomes of FTD/TPI + Bev and neutropenia within the first cycle.

Statistical analysis

PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the statistical significance of the correlation between the clinical outcome and clinical parameters was assessed using the log-rank test. We compared the categorical characteristics by conducting the Pearson's χ2 tests. Statistical tests provided two-sided P values, with P<0.05 considered significant. In the Cox proportional hazard analysis, factors with P<0.05 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis (backward stepwise methods). Statistical analyses were conducted using the EZR statistical software (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) 1.41 based on R and R commander (15).

Results

Patient characteristics

The characteristics of 94 patients with mCRC who received FTD/TPI + Bev are summarized in Table I. The median age at the time of data collection was 60 (range, 32–82) years. Of the 94 patients, 37 were male (39.3%). The lung was the most frequent site of metastasis (73.4%), followed by the liver (59.6%), lymph node (48.9%), and peritoneum (42.6%) at the start of FTD/TPI + Bev. Fifty-seven patients (60.5%) harbored RAS mutants in their tumor tissues. There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics between mCRC patients with and without grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment (Table SI).

Table I.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics (n=94).

| Characteristic | Number of patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Median age at enrollment, years (range) | 60 (32–82) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 37 (39.3) |

| Female | 57 (60.7) |

| ECOG PS | |

| 0 | 64 (68.1) |

| 1 | 24 (25.5) |

| 2 | 6 (6.4) |

| Primary site | |

| Right-sided colon | 26 (27.7) |

| Left-sided colon | 68 (72.3) |

| Metastatic site | |

| Lung | 69 (73.4) |

| Liver | 56 (59.6) |

| Lymph node | 46 (48.9) |

| Peritoneal | 40 (42.6) |

| Other | 26 (27.7) |

| RAS status in tissue | |

| Wild-type | 37 (39.4) |

| Mutant | 57 (60.6) |

| Time from the start of first-line chemotherapy, months | |

| <18 | 32 (34.0) |

| ≥18 | 60 (63.8) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.2) |

| Number of prior regimens | |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) |

| 2 | 68 (72.3) |

| 3 | 22 (23.4) |

| 4 | 4 (4.3) |

| Prior regimens | |

| Fluoropyrimidine | 94 (100.0) |

| Irinotecan | 94 (100.0) |

| Oxaliplatin | 93 (98.9) |

| Angiogenesis inhibitor | 94 (100.0) |

| Anti-EGFR antibodies | 18 (19.1) |

| Number of metastasis | |

| 1 | 10 (10.6) |

| >1 | 84 (89.4) |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; Other, brain, bone, ovary and adrenal glands; RAS, rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Toxicity

We reviewed the adverse events (AEs) of patients with mCRC who received FTD/TPI + Bev. Grade 3 or 4 AEs in all treatment periods occurred in 56 patients (59.6%). AE occurrences in 94 patients with mCRC are summarized in Table II. There were no treatment-related deaths. The most common grade 3 or 4 AEs were neutropenia (51.1%), anemia (13.8%), and thrombocytopenia (6.4%), respectively. Febrile neutropenia occurred in one patient (1.1%). Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia in the first cycle of treatment occurred in 26 patients (27.7%). There were significant differences in the incidence of leucopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hypertension between patients with and without grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment (Table SII).

Table II.

Incidence of adverse events during treatment period.

| Adverse event | Any grade, n (%) | Grade 3 or 4, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 45 (47.9) | 13 (13.8) |

| Neutropenia | 71 (75.5) | 48 (51.1) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18 (19.1) | 6 (6.4) |

| Anorexia | 20 (21.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vomiting | 15 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nausea | 47 (50.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (17.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Hypertension | 12 (12.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Proteinuria | 33 (35.1) | 0 (0.0) |

Survival endpoints and factors associated with survival

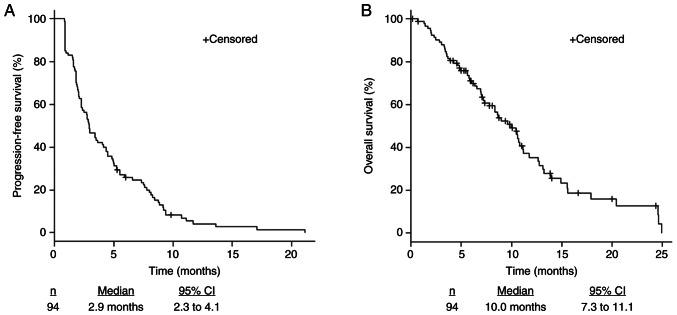

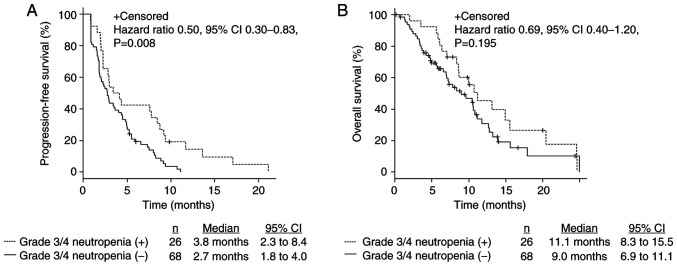

The median PFS was 2.9 months (2.3–4.1), and the median OS was 10.0 months (7.3–11.1) (Fig. 1). The ORR and DCR were 0% and 44.7%, respectively (Table III). Patients with grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment had significantly longer PFS (3.8 months [2.3–8.4] vs. 2.7 months [1.8–4.0], P=0.008) (Fig. 2A) and tended to have longer OS (11.1 months [8.3–15.5] vs. 9.0 months [6.9–11.1], P=0.19 (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, there were no complete nor partial response. The DCR in patients with grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment was higher than in patients without grade 3 or 4 CIN (61.5 and 38.2%, P=0.07; Table III).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival in all patients. CI, confidence interval.

Table III.

Summary of antitumor response.

| Variable | Total number of patients (n=94) | Patients with grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment (n=26) | Patients without grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment (n=68) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best overall response, n (%) | ||||

| Complete response | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Partial response | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Stable disease | 42 (44.7) | 16 (61.5) | 26 (38.2) | – |

| Progressive disease | 45 (47.9) | 10 (38.5) | 35 (51.5) | – |

| Not evaluated | 7 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (10.3) | – |

| Disease control rate, % | 42 (44.7) | 16 (61.5) | 26 (38.2) | 0.07 |

-, not available.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival based on presence or absence of grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment. CI, confidence interval.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of predictors of clinical outcomes

In the univariate Cox proportional hazard analysis, liver metastasis, lymph node metastasis, and grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment were predictive factors for PFS. PS and liver metastasis were predictive factors for OS (Tables IV and V). Moreover, liver and lymph node metastases were independent predictive factors for a shorter PFS, while CIN was an independent predictive factor for a longer PFS (liver metastasis: HR 1.82, 95% CI 1.17–2.83, P=0.007; lymph node metastasis: HR 2.23, 95% CI 1.40–3.54, P=0.0007; grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment: HR 0.51, 95% CI 0.3–0.86, P=0.01) in the multivariate analysis. Furthermore, liver metastasis and performance status were independent predictive factors for a shorter OS (liver metastasis: HR 2.31, 95% CI 1.34–3.98, P=0.002; PS: HR 2.26, 95% CI 1.29–3.97, P=0.004) in the multivariate analysis (Tables IV and V).

Table IV.

Univariate Cox regression analyses for PFS and OS in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

| A, PFS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | HR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 1.16 | 0.75 | 1.79 | 0.4950 |

| ECOG PS (0 vs. 1 or 2) | 1.42 | 0.89 | 2.26 | 0.1340 |

| Age, years (<65 vs. ≥65) | 0.91 | 0.59 | 1.39 | 0.6532 |

| Primary tumor location (left vs. right) | 0.83 | 0.52 | 1.34 | 0.4615 |

| Liver metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 1.53 | 0.99 | 2.36 | 0.0515 |

| Lung metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 0.91 | 0.56 | 1.47 | 0.6975 |

| Peritoneal metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 1.05 | 0.68 | 1.59 | 0.8289 |

| Lymph node metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 2.22 | 1.40 | 3.51 | 0.0006c |

| Tissue RAS mutation (negative vs. positive) | 0.68 | 0.44 | 1.05 | 0.0826 |

| Time from the start of first-line chemotherapy, months (<18 vs. ≥18) | 0.65 | 0.42 | 1.02 | 0.0586 |

| Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment (negative vs. positive) | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.84 | 0.0080b |

| Treatment regimen (bevacizumab vs. other) | 0.78 | 0.51 | 1.20 | 0.2623 |

|

| ||||

| B, OS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Variable | HR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value |

|

| ||||

| Sex (female vs. male) | 1.04 | 0.62 | 1.75 | 0.8573 |

| ECOG PS (0 vs. 1 or 2) | 1.83 | 1.07 | 3.12 | 0.0273a |

| Age, years (<65 vs. ≥65) | 0.81 | 0.47 | 1.37 | 0.4292 |

| Primary tumor location (left vs. right) | 1.01 | 0.58 | 1.77 | 0.9616 |

| Liver metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 1.95 | 1.15 | 3.30 | 0.0126a |

| Lung metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 0.81 | 0.46 | 1.42 | 0.4567 |

| Peritoneal metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 1.11 | 0.66 | 1.85 | 0.6868 |

| Lymph node metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 1.16 | 0.70 | 1.91 | 0.5673 |

| Tissue RAS mutation (negative vs. positive) | 1.13 | 0.67 | 1.89 | 0.6407 |

| Time from the start of first-line chemotherapy, months (<18 vs. ≥18) | 0.91 | 0.54 | 1.52 | 0.7077 |

| Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment (negative vs. positive) | 0.70 | 0.40 | 1.20 | 0.1950 |

| Treatment regimen (bevacizumab vs. other) | 1.37 | 0.81 | 2.33 | 0.2423 |

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; RAS, rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog.

Table V.

Multivariate Cox regression analyses for PFS and OS in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

| A, PFS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | HR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value |

| Liver metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 1.82 | 1.17 | 2.83 | 0.0079b |

| Lymph node metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 2.23 | 1.40 | 3.54 | 0.0007c |

| Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia within the first cycle of treatment (negative vs. positive) | 0.51 | 0.30 | 0.86 | 0.0118a |

|

| ||||

| B, OS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Variable | HR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P-value |

|

| ||||

| ECOG PS (0 vs. 1 or 2) | 2.26 | 1.29 | 3.97 | 0.0043b |

| Liver metastasis (negative vs. positive) | 2.31 | 1.34 | 3.98 | 0.0027b |

P<0.05

P<0.01

P<0.001. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status.

Previous reports of clinical outcomes

A summary of previous prospective and retrospective reports of FTD/TPI + Bev for patients with mCRC receiving salvage-line therapy is presented in Table VI (11,14,16–20). In these reports, the median PFS time was 3.7–6.8 months and the median OS time was 8.6–14.4 months. In addition, grade 3 or 4 neutropenia occurred in 38.9–72.0% of all cases. The clinical outcomes of the present study were comparable to previous reports (11,14,16–20). A summary of previous prospective and retrospective reports of FTD/TPI monotherapy for patients with mCRC is presented in Table SIII (5,6,21–28). In these reports, the median PFS time was 2.0–2.5 months and the median OS time was 5.3–9.0 months. Furthermore, grade 3 or 4 neutropenia occurred in 14.3–50.0% of all cases.

Table VI.

Previous reports of clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab as a late-line treatment.

| Author, year (ref.) | Number of patients | RR, % | DCR, % | PFS, months | OS, months | Grade 3 or 4 neutropenia in all treatment periods, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuboki et al, 2017 (11) | 21 | 0.0 | 64.0 | 3.7 | 11.4 | 72.0 |

| Kotani et al, 2019 (17) | 60 | 5.0 | 53.3 | 3.7 | 8.6 | 50.0 |

| Matsuhashi et al, 2019 (18) | 17 | 0.0 | 70.1 | 6.8 | 14.1 | 41.2 |

| Pfeiffer et al, 2020 (14) | 46 | 2.2 | 67.4 | 4.6 | 9.4 | 67.4 |

| Fujii et al, 2020 (19) | 21 | 0.0 | 76.1 | 5.6 (TTF) | 14.4 | 52.4 |

| Shibutani et al, 2020 (20) | 36 | 8.3 | 58.3 | – | – | 38.9 |

| Nose et al, 2020 (16) | 32 | – | – | 4.7 | 11.7 | 53.1 |

| Data in present study | 94 | 0.0 | 44.7 | 2.9 | 10.0 | 51.1 |

RR, response rate; DCR, disease control rate; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; TTF, time to treatment failure; -, not available.

Discussion

In the present study, we explored the clinical outcomes of FTD/TPI + Bev and the predictive factors of its efficacy. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that CIN within the first cycle of treatment is an indicator for the efficacy of FTD/TPI + Bev in multivariate analysis of a large number of cases. FTD/TPI + Bev showed enhanced activity against colorectal cancer xenografts compared with FTD/TPI alone (29). Moreover, clinical data from the phase I/II C-TASK FORCE study and the phase II study conducted by Pfeiffer et al (11,14) showed that treatment with FTD/TPI + Bev induced promising antitumor activity with manageable toxicity in advanced mCRC refractory or intolerant to standard therapies. A summary of previous prospective and retrospective reports of FTD/TPI + Bev for patients with mCRC receiving salvage-line therapy is shown in Table VI (11,14,16–20). The clinical outcomes such as PFS, OS, and DCR in patients treated with the FTD/TPI + Bev are better than those in patients treated with the FTD/TPI monotherapy (Tables VI and SIII) (5,6,11,14,16–28). Furthermore, the clinical outcomes of FTD/TPI + Bev of this study were comparable to previous reports. Thus, FTD/TPI + Bev may be a more effective regimen than FTD/TPI monotherapy. On the other hand, the incidence of grade 3 or 4 CIN of FTD/TPI + Bev is higher than FTD/TPI monotherapy (Tables VI and SIII) (5,6,11,14,16–28). CIN was an independent predictive factor for the efficacy of FTD/TPI monotherapy, as reported previously (11,30–32). As mentioned before, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics analysis in the RECOURSE trial suggests a dose-response relationship between FTD exposure and CIN, in agreement with the findings of the dose-escalation studies that a higher rate of CIN at higher doses of FTD/TPI leads to greater efficacy of the drug (10). Furthermore, results of a randomized phase II trial comparing FTD/TPI + Bev with FTD/TPI monotherapy showed that grade 3 or higher neutropenia in the FTD/TPI + Bev group was 67 vs. 38% in the FTD/TPI monotherapy group and PFS in the FTD/TPI + Bev group is significantly longer than that in the FTD/TPI monotherapy group (14). This is because anti-angiogenic drugs can normalize tumor vasculature, alleviate hypoxia, increase drug delivery, and elevate antitumor immune cells; because tumors are accompanied by abnormal vascular structure, tumor interstitial fluid pressure increases owing to vascular leakage, accompanied by hypoxia (33). In addition, a meta-analysis showed that Bev was associated with an increased risk of high-grade neutropenia, as inhibition of the VEGF receptor blocks hematopoietic stem cell cycle, differentiation, and recovery after bone marrow suppression (34). According to the above hypothesis, the clinical outcome of FTD/TPI + Bev was better than that of FTD/TPI monotherapy. Furthermore, it was similar to the results of several second-line clinical trials (35,36) that investigated a combination therapy consisting of a chemotherapy and anti-VEGF antibody for patients with mCRC. We did not discuss the results of first-line clinical trials in this manuscript. Nevertheless, this study was limited by the relatively small number of patients and its retrospective nature. Despite these limitations, the results of this study provide important and novel insights into the clinical use of FTD/TPI + Bev in salvage-line chemotherapy. For mCRC patients without neutropenia after the initiation of FTD/TPI + Bev, we should consider early image evaluation and treatment changes (e.g., regorafenib) or BSC. In conclusion, the clinical outcomes of FTD/TPI + Bev were comparable to previous reports that showed it to be more effective than FTD/TPI monotherapy. Grade 3 or 4 CIN within the first cycle of treatment is an early predictive marker of the chemotherapeutic efficacy of FTD/TPI + Bev. This could be a useful biomarker for optimizing treatment decisions in daily clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors of the present study would like to thank Ms Yukie Naito and Ms Yuki Horiike (Cancer Institute Hospital, Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research) for providing data management.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BSC

best supportive care

- CIN

chemotherapy-induced neutropenia

- CR

complete response

- DCR

disease control rate

- ORR

objective response rate

- OS

overall survival

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PR

partial response

- SD

stable disease

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

DK, HO and ES conceptualized and designed the present study. DK, HO, ES, AO, TW, KYo, TS, IN, MO, DT, KC and KYa acquired and analyzed the data. DK, HO, ES and AO interpreted the data. DK and HO drafted the initial manuscript and performed statistical analysis. ES, AO, TW, KYo, TS, IN, MO, DT, KC and KYa critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. ES and KYa supervised the study. DK, HO and ES confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research (Tokyo, Japan; approval no. 2020-1017). The protocol is described on the hospital website, and subjects were provided the opportunity to opt-out; therefore, no additional consent was required from patients. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Tanaka N, Sakamoto K, Okabe H, Fujioka A, Yamamura K, Nakagawa F, Nagase H, Yokogawa T, Oguchi K, Ishida K, et al. Repeated oral dosing of TAS-102 confers high trifluridine incorporation into DNA and sustained antitumor activity in mouse models. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:2319–3226. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidelberger C, Parsons DG, Remy DC. Syntheses of 5-trifluoromethyluracil and 5-trifluoromethyl-2′-deoxyuridine. J Med Chem. 1964;7:1–5. doi: 10.1021/jm00331a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujiwara Y, Oki T, Heidelberger C. Fluorinated pyrimidines. XXXVII. Effects of 5-trifluoromethyl-2′-deoxyuridine on the synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid of mammalian cells in culture. Mol Pharmacol. 1970;6:273–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emura T, Suzuki N, Fujioka A, Ohshimo H, Fukushima M. A novel combination antimetabolite, TAS-102, exhibits antitumor activity in FU-resistant human cancer cells through a mechanism involving FTD incorporation in DNA. Int J Oncol. 2004;25:571–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer RJ, Van Cutsem E, Falcone A, Yoshino T, Garcia-Carbonero R, Mizunuma N, Yamazaki K, Shimada Y, Tabernero J, Komatsu Y, et al. Randomized trial of TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1909–1919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu J, Kim TW, Shen L, Sriuranpong V, Pan H, Xu R, Guo W, Han SW, Liu T, Park YS, et al. Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase iii trial of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) monotherapy in Asian patients with previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: The TERRA study. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:350–358. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y, Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hasegawa K, Hotta K, Ishida H, Ishiguro M, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1–42. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01485-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Arain MA, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Farkas L, et al. Colon Cancer, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:329–359. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2021.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, Aranda Aguilar E, Bardelli A, Benson A, Bodoky G, et al. ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1386–1422. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshino T, Cleary JM, Van Cutsem E, Mayer RJ, Ohtsu A, Shinozaki E, Falcone A, Yamazaki K, Nishina T, Garcia-Carbonero R, et al. Neutropenia and survival outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with trifluridine/tipiracil in the RECOURSE and J003 trials. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuboki Y, Nishina T, Shinozaki E, Yamazaki K, Shitara K, Okamoto W, Kajiwara T, Matsumoto T, Tsushima T, Mochizuki N, et al. TAS-102 plus bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies (C-TASK FORCE): An investigator-initiated, open-label, single-arm, multicentre, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:1172–1181. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satake H, Kato T, Oba K, Kotaka M, Kagawa Y, Yasui H, Nakamura M, Watanabe T, Matsumoto T, Kii T, et al. Phase Ib/II Study of biweekly TAS-102 in combination with bevacizumab for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies (BiTS Study) Oncologist. 2020;25:e1855–e1863. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Cutsem E, Danielewicz I, Saunders MP, Pfeiffer P, Argilés G, Borg C, Glynne-Jones R, Punt CJA, Van de Wouw AJ, Fedyanin M, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil plus bevacizumab in patients with untreated metastatic colorectal cancer ineligible for intensive therapy: The randomized TASCO1 study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1160–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeiffer P, Yilmaz M, Möller S, Zitnjak D, Krogh M, Petersen LN, Poulsen LØ, Winther SB, Thomsen KG, Qvortrup C. TAS-102 with or without bevacizumab in patients with chemorefractory metastatic colorectal cancer: An investigator-initiated, open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:412–420. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30827-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nose Y, Kagawa Y, Hata T, Mori R, Kawai K, Naito A, Sakamoto T, Murakami K, Katsura Y, Ohmura Y, et al. Neutropenia is an indicator of outcomes in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with FTD/TPI plus bevacizumab: A retrospective study. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2020;86:427–433. doi: 10.1007/s00280-020-04129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotani D, Kuboki Y, Horasawa S, Kaneko A, Nakamura Y, Kawazoe A, Bando H, Taniguchi H, Shitara K, Kojima T, et al. Retrospective cohort study of trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) plus bevacizumab versus trifluridine/tipiracil monotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1253. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuhashi N, Takahashi T, Fujii H, Suetsugu T, Fukada M, Iwata Y, Tokumaru Y, Imai T, Mori R, Tanahashi T, et al. Combination chemotherapy with TAS-102 plus bevacizumab in salvage-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A single-center, retrospective study examining the prognostic value of the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score in salvage-line therapy of metastatic colorectal cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2019;11:390–396. doi: 10.3892/mco.2019.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujii H, Matsuhashi N, Kitahora M, Takahashi T, Hirose C, Iihara H, Yamada Y, Watanabe D, Ishihara T, Suzuki A, Yoshida K. Bevacizumab in combination with TAS-102 improves clinical outcomes in patients with refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective study. Oncologist. 2020;25:e469–e476. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibutani M, Nagahara H, Fukuoka T, Iseki Y, Wang EN, Okazaki Y, Kashiwagi S, Maeda K, Hirakawa K, Ohira M. Combining bevacizumab with trifluridine/thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor improves the survival outcomes regardless of the usage history of bevacizumab in front-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2020;40:4157–4163. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.14415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshino T, Mizunuma N, Yamazaki K, Nishina T, Komatsu Y, Baba H, Tsuji A, Yamaguchi K, Muro K, Sugimoto N, et al. TAS-102 monotherapy for pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:993–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70345-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arita S, Shirakawa T, Matsushita Y, Shimokawa HK, Hirano G, Makiyama A, Shibata Y, Tamura S, Esaki T, Mitsugi K, et al. Efficacy and safety of TAS-102 in clinical practice of salvage chemotherapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:1959–1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masuishi T, Taniguchi H, Hamauchi S, Komori A, Kito Y, Narita Y, Tsushima T, Ishihara M, Todaka A, Tanaka T, et al. Regorafenib versus trifluridine/tipiracil for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A retrospective comparison. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:e15–e22. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kotani D, Shitara K, Kawazoe A, Fukuoka S, Kuboki Y, Bando H, Okamoto W, Kojima T, Doi T, Ohtsu A, et al. Safety and efficacy of trifluridine/tipiracil monotherapy in clinical practice for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: Experience at a single institution. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:e109–e115. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sueda T, Sakai D, Kudo T, Sugiura T, Takahashi H, Haraguchi N, Nishimura J, Hata T, Hayashi T, Mizushima T, et al. Efficacy and safety of regorafenib or TAS-102 in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard therapies. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:4299–4306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwakman JJM, Vink G, Vestjens JH, Beerepoot LV, de Groot JW, Jansen RL, Opdam FL, Boot H, Creemers GJ, van Rooijen JM, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of trifluridine/tipiracil in metastatic colorectal cancer: Real-life data from the netherlands. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:482–489. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cremolini C, Rossini D, Martinelli E, Pietrantonio F, Lonardi S, Noventa S, Tamburini E, Frassineti GL, Mosconi S, Nichetti F, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil (TAS-102) in refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A multicenter register in the frame of the Italian compassionate use program. Oncologist. 2018;23:1178–1187. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriwaki T, Fukuoka S, Taniguchi H, Takashima A, Kumekawa Y, Kajiwara T, Yamazaki K, Esaki T, Makiyama C, Denda T, et al. Propensity score analysis of regorafenib versus trifluridine/tipiracil in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapy (REGOTAS): A Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum multicenter observational study. Oncologist. 2018;23:7–15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsukihara H, Nakagawa F, Sakamoto K, Ishida K, Tanaka N, Okabe H, Uchida J, Matsuo K, Takechi T. Efficacy of combination chemotherapy using a novel oral chemotherapeutic agent, TAS-102, together with bevacizumab, cetuximab, or panitumumab on human colorectal cancer xenografts. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:2135–2142. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kasi PM, Kotani D, Cecchini M, Shitara K, Ohtsu A, Ramanathan RK, Hochster HS, Grothey A, Yoshino T. Chemotherapy induced neutropenia at 1-month mark is a predictor of overall survival in patients receiving TAS-102 for refractory metastatic colorectal cancer: A cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:467. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2491-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamauchi S, Yamazaki K, Masuishi T, Kito Y, Komori A, Tsushima T, Narita Y, Todaka A, Ishihara M, Yokota T, et al. Neutropenia as a predictive factor in metastatic colorectal cancer treated with TAS-102. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2017;16:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makihara K, Fukui R, Uchiyama H, Shigeoka Y, Toyokawa A. Decreased percentage of neutrophil is a predict factor for the efficacy of trifluridine and tipiracil hydrochloride for pretreated metastatic colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019;10:878–885. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.04.04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Bock K, Mazzone M, Carmeliet P. Anti-angiogenic therapy, hypoxia, and metastasis: Risky liaisons, or not? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:393–404. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schutz FA, Jardim DL, Je Y, Choueiri TK. Haematologic toxicities associated with the addition of bevacizumab in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1161–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hurwitz H, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny W, Cartwright T, Hainsworth J, Heim W, Berlin J, Baron A, Griffing S, Holmgren E, et al. Bevacizumab plus irinotecan, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2335–2342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D, Österlund P, Greil R, Van Cutsem E, von Moos R, Viéitez JM, Bouché O, Borg C, et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): A randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.