Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to examine the cumulative disadvantage of different forms of childhood misfortune and adult-life socioeconomic conditions (SEC) with regard to trajectories and levels of self-rated health in old age and whether these associations differed between welfare regimes (Scandinavian, Bismarckian, Southern European, and Eastern European).

Method

The study included 24,004 respondents aged 50–96 from the longitudinal SHARE survey. Childhood misfortune included childhood SEC, adverse childhood experiences, and adverse childhood health experiences. Adult-life SEC consisted of education, main occupational position, and financial strain. We analyzed associations with poor self-rated health using confounder-adjusted mixed-effects logistic regression models for the complete sample and stratified by welfare regime.

Results

Disadvantaged respondents in terms of childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC had a higher risk of poor self-rated health at age 50. However, differences narrowed with aging between adverse-childhood-health-experiences categories (driven by Southern and Eastern European welfare regimes), categories of education (driven by Bismarckian welfare regime), and main occupational position (driven by Scandinavian welfare regime).

Discussion

Our research did not find evidence of cumulative disadvantage with aging in the studied life-course characteristics and age range. Instead, trajectories showed narrowing differences with differing patterns across welfare regimes.

Keywords: Cumulative advantage/disadvantage, Early origins of health, Life-course analysis, Self-rated health

As European societies grow older, understanding the factors that support good health in old age becomes increasingly important (Rechel et al., 2013). The literature investigating the effect of life-course factors on different healthy aging outcomes has repeatedly shown that adversities early in life have a long-lasting detrimental effect on health (Schafer & Ferraro, 2012; Sieber et al., 2019). Childhood misfortune specifically has been shown to impact health in the long term, irrespective of adult-life socioeconomic conditions (SEC) (Aartsen et al., 2019; Cheval, Chabert, Sieber, et al., 2019; Cheval, Chabert, Orsholits, et al., 2019; Landös et al., 2019; Schafer & Ferraro, 2012; van de Straat et al., 2018). Studies showed that poor self-rated health (SRH) in adult life in general was associated with disadvantaged childhood socioeconomic conditions (CSC) (Hyde, Jakub, Melchior, Van Oort, & Weyers, 2006; Sieber et al., 2019), adverse childhood experiences (ACE) (Felitti et al., 1998; Gilbert et al., 2015), and adverse childhood health experiences (ACHE) (Haas, 2007; Power & Peckham, 1990). Yet, evidence is lacking on whether these associations with SRH apply to adults aged 50 and older and on how they develop with aging.

As a comprehensive health measure covering different health dimensions such as physical and mental health and as a predictor of mortality (DeSalvo, Bloser, Reynolds, He, & Muntner, 2006), SRH has proven to be a relevant outcome when examining differences in older adults’ health (Christian et al., 2011; O’Brien Cousins, 1997).

From a life-course perspective, the long-lasting effects of childhood misfortune on SRH in old age can be explained by the cumulative dis/advantage (CDA) model, defined as the “systemic tendency for interindividual divergence in a given characteristic (e.g., money, health, or status) with the passage of time’’ (Dannefer, 2003). The CDA model posits that social conditions and events early in the life course create differences between individuals that grow over time (Dannefer, 1987; Schafer, Ferraro, & Mustillo, 2011). These processes are intertwined with the everyday lives of individuals, generating either increasing or decreasing advantages, which lead to a consistently growing gap in health (or another characteristic) between subgroups with the passage of time (Cullati, Rousseaux, Gabadinho, Courvoisier, & Burton-Jeangros, 2014; Ferraro & Kelley-Moore, 2003). While the focus on the influences of childhood misfortune on later-life health is crucial, it is important not to neglect the other life-course influences. The danger of “Time-One Encapsulation” exists if the causal role of SEC later in life is disregarded and attention is only paid to childhood conditions (Dannefer, 2018). Dannefer (2018) uses the term “life-course reflexivity” to emphasize the necessity of considering social conditions later in life when looking at childhood effects, thus employing an encompassing life-course approach in studying CDA processes. There are two underlying elements of this principle. First, interactive dynamics in adulthood are acknowledged as having a role in producing changes in the life course in mid- and old age, and, second, human intentionality and action are considered central in shaping these changes (Dannefer, 2018).

At the same time, contrary to the CDA model, some authors posit that differences between individuals become less pronounced over the life course. This tendency could be due to health selection in old age, where only the most robust individuals of each group survive over time, leading to narrowing differences between social categories (O’Rand, 2009). This theory is also known as the age-as-leveler hypothesis (Lynch, 2003). Another explanation consists of life-course processes that have the potential to reverse the CDA mechanisms through their positive effects (O’Rand, 2009). This includes “unexpected shifts in life conditions,” such as marriage/divorce or new employment, and “personal aspirations” or individual agency to overcome disadvantaged social origins (Burton-Jeangros, Cullati, Sacker, & Blane, 2015; O’Rand, 2009).

This article intends to test three aspects of the CDA theory with regard to SRH trajectories: (a) Growing differences with aging by different childhood misfortune categories, (b) The principle of life-course reflexivity by acknowledging the importance of interactive dynamics in adult-life, which produce mid- and later life changes (Dannefer, 2018), (c) The influence of large-scale social regulation of economic and policy factors within states on the variation in trajectories (Dannefer, 2018). Thus, we aim to test the CDA mechanisms at two different levels: at the micro-level considering the role of childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC and at the macro-level by taking into account welfare regimes.

Since the CDA processes are thought to operate not only on micro- but also macro-levels, creating distinction and stratification at each level as individuals move through the life course, it is crucial to take into account their multileveled reality (Dannefer, 2018). The CDA model is based on social dynamics driven by macro-level forces impacting individual trajectories, which are expected to vary according to economic and welfare-state policies (Cullati et al., 2014; Dannefer, 2018). These varying effects are thought to occur because social policies alleviate adversities in individuals’ lives to differing degrees (Sieber et al., 2019). More generous welfare regimes reduce social stratification and absorb the impact of material shortfalls by providing higher levels of benefits to their citizens (Bartley, Blane, & Montgomery, 1997). Moreover, we hypothesize that CDA processes are less pronounced or offset in more generous welfare regimes since individuals are given more opportunities to break free from a vicious cycle of cumulative disadvantage. For instance, state-level pension plans or health insurance (e.g., Medicare) may help compensate adversities experienced throughout the life course (Crystal, Shea, & Reyes, 2017; Dannefer, 2018; McWilliams, Meara, Zaslavsky, & Ayanian, 2010; Myerson, Tucker-Seeley, Goldman, & Lakdawalla, 2019). Following previous research on the impact of life-course SEC on SRH at old age, countries can be grouped into four welfare regimes to reflect similarities in terms of the relative roles of the state, family, and market in the provision of welfare (Sieber et al., 2019). In that respect, Ferrera’s typology derived from Esping-Andersen’s and augmented by the Eastern European welfare regime, focuses on how social benefits are granted and organized, and is labeled as one of the most accurate typologies (Eikemo, Bambra, Judge, & Ringdal, 2008; Eikemo, Huisman, Bambra, & Kunst, 2008; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1996). The Scandinavian welfare regime is characterized by a strong interventionist state aiming at social equality trough a generous redistributive social-security system and universal coverage (Eikemo, Bambra, et al., 2008; Esping-Andersen, 1990). The Bismarckian welfare regime is minimally redistributive with benefits being related to earnings and administered by employers, which leads to “status differentiating” welfare programs which distinguishes this welfare regime from others (Bambra & Eikemo, 2009; Eikemo, Bambra, et al., 2008; Esping-Andersen, 1990). The Southern European welfare regime is considered a rather basic type of welfare state, with a fragmented system of welfare provision and strong reliance on family and the charitable sector as well as partial health care coverage (Eikemo, Bambra, et al., 2008; Ferrera, 1996). The Eastern European welfare regime is characterized by limited health service provision and poor overall population health, grouping formerly Communist countries that experienced a shift from universalism to a marketized and decentralized welfare state (Bambra & Eikemo, 2009; Eikemo, Huisman, et al., 2008).

In terms of empirical analyzes, this study has three objectives in line with the three aspects of the CDA theory. First, we aim at examining the associations of different forms of childhood misfortune (CSC, ACE, ACHE) with levels and trajectories of SRH in old age. Second, we investigate the role of adult-life SEC (education, main occupation, financial strain) in the association of childhood adversities with levels and trajectories of SRH in old age. By following the life-course reflexivity principle, we aim to take into account the whole life course and acknowledge the potential causal role of adult-life SEC, which has not been done by existing studies on CDA and SRH (Bauldry, Shanahan, Boardman, Miech, & Macmillan, 2012; Cullati et al., 2014; Mirowsky & Ross, 2008). Third, we aim to examine whether welfare regimes influence the associations of childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC with levels and trajectories of SRH in old age. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time the CDA hypothesis has been tested with SRH in older age with a comparative analysis strategy examining differences across welfare regimes. We hypothesize that in more generous welfare regimes with strong redistributive policies, the CDA processes are less marked, that is, the processes that lead to growing differences between categories of childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC are absent or less discriminating. The distinction between levels and trajectories is important as the levels allow us to examine the differences in SRH at the beginning of the studied period, indicating potential CDA processes before the age of 50 which led to these differences. The trajectories, however, allow us to directly investigate whether CDA processes can be observed in the studied period between 50 and 96 years.

Method

Study Design and Participants

In this study, we used cross-national and longitudinal data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), which collected information on health and SEC of individuals aged 50 and older in 27 European countries (Börsch-Supan et al., 2013). SHARE has collected six waves (every 2 years) of data between 2004 and 2015. Wave 3 includes retrospective life-course data on childhood and adult-life predictors. In our study, we included participants aged between 50 and 96 years who participated in the third wave and had at least one SRH observation over the six survey waves.

Welfare Regimes

This study used the welfare regime classification as proposed by Eikemo et al. (2008), which expands Ferrera’s typology with the Eastern European welfare regime (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Ferrera, 1996). Accordingly, we classified the 13 countries in the final sample into four welfare regimes: Scandinavian (Denmark, Sweden), Bismarckian (Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland), Southern European (Greece, Italy, Spain), and Eastern European (Czech Republic, Poland). See Supplementary Material for more information.

Measures

Outcome: Self-Rated Health

In line with a previous study (Sieber et al., 2019), we formed a binary outcome by grouping the categories “poor” and “fair” indicating poor SRH as opposed to “good,” “very good,” and “excellent” indicating good SRH (see Supplementary Material for more information).

Childhood Misfortune

ACE

We used a score combining a set of traumatic events (emotional, physical, or linked to household dysfunction) that occurred during childhood (from age 0 to 15) and that were outside a child’s control (Felitti et al., 1998); parental death (father, mother, or both), parental mental illness, parental drinking abuse, child in care (living in a children’s home or with a foster family), period of hunger, and property taken away. Following previous studies, we computed a score ranging from 0 to 7 by combining the 6 ACE indicators (see Supplementary Material for more information).

ACHE

ACHE combined information on five indicators of childhood health problems up until the age of 15 into a binary variable (Cheval, Chabert, Sieber, et al., 2019; Cheval, Orsholits, et al., 2019); long hospitalization (hospitalization for a month or more), multiple hospitalizations (more than three times within a 12-month period), childhood illness (including polio, asthma, or meningitis/encephalitis), serious health conditions (including severe headaches, psychiatric problem, fractures, heart trouble, cancers), and physical injury that has led to permanent handicap, disability, or limitation in daily life (see Supplementary Material for more information).

CSC

CSC is a score derived from four binary indicators of adverse SEC at age 10: (a) occupational position of the main breadwinner (low vs high skill), (b) number of books in the home (≤10 vs >10), (c) a measure of overcrowding (more than one vs one or less persons per room in the household), and (d) housing quality (absence of all vs presence of at least one of the following: fixed bath, cold and hot running water, inside toilet, central heating) (Wahrendorf & Blane, 2015, see Supplementary Material for more information).

Adult-life SEC

We used three indicators of adult-life SEC representing different adult-life periods (Sieber et al., 2019); education (primary, secondary, tertiary), main occupational position (low and high skill), and financial strain (Is the household able to make ends meet? easily, fairly easily, with some difficulty, with great difficulty; see Supplementary Material for more information).

Statistical Analysis

We used logistic mixed-effects models to analyze the data with observations (Level 1) nested within participants (Level 2). These models avoided excluding participants with missing observations as they do not require an equal number of observations for all participants. Age was centered at the beginning of the trajectory (i.e., 50 years), which allowed us to examine the differences in level of poor SRH at the youngest age of the sample’s age range. In addition, age was divided by 10 so that the coefficient yielded effects of increase in risk of poor SRH over a 10-year period. A quadratic term for age was not included in the models since preliminary tests revealed that it was not significant and did not improve model fit. Model 1a tested the association between childhood misfortune (CSC, ACE, ACHE) and the level of risk of poor SRH at age 50 (Table 2). In addition, Model 1a included interaction terms between age and childhood misfortune to examine whether childhood misfortune influences the trajectories of poor SRH with aging. This allowed us to test whether the differences between childhood misfortune categories were growing (cumulative disadvantage) or narrowing with aging. In Model 2a, we added the adult-life SEC (education, main occupational position, financial strain) and their respective interactions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of Childhood Misfortune and Adult-Life Socioeconomic Circumstances with Level and Trajectories of Poor Self-Rated Health at Old Age

| M1a | M2a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (10-year period) | 2.81 (2.58–3.07) | *** | 2.98 (2.59–3.42) | *** |

| At least one ACE (ref. None) | 1.69 (1.44–2.00) | *** | 1.66 (1.42–1.95) | *** |

| At least one ACHE (ref. None) | 1.82 (1.57–2.11) | *** | 1.85 (1.60–2.13) | *** |

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||

| Disadvantaged | 0.57 (0.46–0.70) | *** | 0.79 (0.64–0.97) | * |

| Middle | 0.28 (0.23–0.34) | *** | 0.59 (0.48–0.73) | *** |

| Advantaged | 0.18 (0.14–0.22) | *** | 0.53 (0.42–0.67) | *** |

| Most advantaged | 0.09 (0.07–0.13) | *** | 0.42 (0.30–0.59) | *** |

| Education (ref. Primary) | ||||

| Secondary | 0.67 (0.57–0.80) | *** | ||

| Tertiary | 0.34 (0.26–0.43) | *** | ||

| Main Occupational Position (ref. High skill) | ||||

| Low skill | 1.60 (1.33–1.91) | *** | ||

| Never worked | 0.96 (0.71–1.30) | |||

| Financial strain (ref. Easily) | ||||

| Fairly easily | 1.74 (1.48–2.04) | *** | ||

| With some difficulty | 3.35 (2.80–4.01) | *** | ||

| With great difficulty | 7.17 (5.70–9.01) | *** | ||

| Interactions | ||||

| Age × at least one ACE (ref. None) | 0.99 (0.91–1.07) | 0.97 (0.90–1.05) | ||

| Age × at least one ACHE (ref. None) | 0.85 (0.78–0.91) | *** | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) | *** |

| Age × CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||

| Age × Disadvantaged | 1.00 (0.91–1.10) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | ||

| Age × Middle | 1.04 (0.95–1.14) | 0.99 (0.90–1.09) | ||

| Age × Advantaged | 1.05 (0.94–1.17) | 0.95 (0.84–1.06) | ||

| Age × Most advantaged | 1.08 (0.92–1.27) | 0.93 (0.78–1.10) | ||

| Age × Education (ref. Primary) | ||||

| Age × Secondary | 1.04 (0.96–1.13) | |||

| Age × Tertiary | 1.20 (1.07–1.36) | ** | ||

| Age × Main occupational position (ref. High skill) | ||||

| Age × Low skill | 0.89 (0.82–0.98) | * | ||

| Age × Never worked | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) | |||

| Age × Financial strain (ref. Easily) | ||||

| Age × Fairly easily | 1.04 (0.97–1.13) | |||

| Age × With some difficulty | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | |||

| Age × With great difficulty | 0.92 (0.82–1.03) |

Note: ACE = adverse childhood experiences; ACHE = adverse childhood health experiences; CI = confidence interval; CSC = childhood socioeconomic conditions; OR = odds ratios. All models are adjusted for sex, birth cohort, and attrition. Age was centered at 50 years and divided by 10 so that the coefficients yielded the effects for a 10-year period.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

As previous research has shown that welfare regime moderates the associations between adult-life SEC and level of poor SRH (Sieber et al., 2019), we ran models including triple interactions (age × predictors × welfare regime) testing whether welfare regime also moderated the trajectories of poor SRH (data not shown). Significant triple interactions supported our decision to stratify the models by welfare regime. We ran Models 1b and 2b (Tables 3 and 4, see Supplementary Material) separately for each welfare regime and correspond to the unstratified Models 1a and 2a.

Table 3.

Associations of Childhood Misfortune and Adult-Life Socioeconomic Circumstances with Level and Trajectories of Poor Self-Rated Health at Old Age Stratified by Scandinavian and Bismarckian Welfare Regime

| Scandinavian | Bismarckian | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 3,626 | N = 10,250 | |||||||

| M1b | M2b | M1b | M2b | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (10-year period) | 3.51 (2.41–5.10) | *** | 5.00 (3.22–7.75) | *** | 2.66 (2.24–3.16) | *** | 2.77 (2.18–3.52) | *** |

| At least one ACE (ref. None) | 2.06 (1.34–3.19) | ** | 1.99 (1.30–3.06) | ** | 1.79 (1.38–2.33) | *** | 1.57 (1.22–2.03) | *** |

| At least one ACHE (ref. None) | 1.47 (1.00–2.18) | 1.54 (1.05–2.27) | * | 1.81 (1.44–2.27) | *** | 1.70 (1.36–2.13) | *** | |

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Disadvantaged | 0.77 (0.26–2.27) | 0.82 (0.28–2.38) | 0.66 (0.43–1.02) | 0.84 (0.55–1.29) | ||||

| Middle | 0.35 (0.13–0.96) | * | 0.49 (0.18–1.34) | 0.38 (0.25–0.58) | *** | 0.69 (0.45–1.05) | ||

| Advantaged | 0.24 (0.09–0.67) | ** | 0.41 (0.15–1.16) | 0.27 (0.18–0.42) | *** | 0.60 (0.39–0.94) | * | |

| Most advantaged | 0.12 (0.04–0.36) | *** | 0.29 (0.09–0.93) | * | 0.14 (0.08–0.24) | *** | 0.44 (0.26–0.77) | ** |

| Education (ref. Primary) | ||||||||

| Secondary | 1.38 (0.77–2.47) | 0.57 (0.42–0.78) | ** | |||||

| Tertiary | 0.86 (0.44–1.69) | 0.35 (0.23–0.52) | *** | |||||

| Main Occupational Position (ref. High skill) | ||||||||

| Low skill | 3.68 (2.37–5.71) | *** | 1.65 (1.25–2.17) | *** | ||||

| Never worked | 3.94 (0.34–46.05) | 2.49 (1.31–4.75) | ** | |||||

| Financial strain (ref. Easily) | ||||||||

| Fairly easily | 1.25 (0.81–1.93) | 1.90 (1.49–2.42) | *** | |||||

| With some difficulty | 3.45 (1.66–7.16) | ** | 4.88 (3.56–6.69) | *** | ||||

| With great difficulty | 9.04 (2.44–33.42) | ** | 27.02 (17.05–42.83) | *** | ||||

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Age × at least one ACE (ref. None) | 0.86 (0.69–1.06) | 0.86 (0.70–1.06) | 1.01 (0.89–1.14) | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | ||||

| Age × at least one ACHE (ref. None) | 1.00 (0.83–1.21) | 0.97 (0.80–1.16) | 0.91 (0.81–1.02) | 0.93 (0.83–1.04) | ||||

| Age × CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Age × Disadvantaged | 0.98 (0.65–1.47) | 0.99 (0.66–1.50) | 1.05 (0.87–1.26) | 1.02 (0.85–1.23) | ||||

| Age × Middle | 1.07 (0.73–1.57) | 1.08 (0.73–1.60) | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 0.97 (0.81–1.17) | ||||

| Age × Advantaged | 1.00 (0.67–1.48) | 0.99 (0.66–1.49) | 1.11 (0.92–1.35) | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) | ||||

| Age × Most advantaged | 1.15 (0.72–1.83) | 1.07 (0.66–1.74) | 1.17 (0.92–1.50) | 0.99 (0.77–1.28) | ||||

| Age × Education (ref. Primary) | ||||||||

| Age × Secondary | 0.85 (0.66–1.08) | 1.07 (0.93–1.23) | ||||||

| Age × Tertiary | 0.82 (0.61–1.10) | 1.28 (1.06–1.55) | * | |||||

| Age × Main occupational position (ref. High skill) | ||||||||

| Age × Low skill | 0.69 (0.56–0.85) | *** | 0.96 (0.83–1.10) | |||||

| Age × Never worked | 0.60 (0.25–1.46) | 0.94 (0.72–1.22) | ||||||

| Age × Financial strain (ref. Easily) | ||||||||

| Age × Fairly easily | 1.19 (0.97–1.45) | 1.01 (0.90–1.13) | ||||||

| Age × With some difficulty | 1.01 (0.73–1.40) | 0.89 (0.76–1.04) | ||||||

| Age × With great difficulty | 1.16 (0.62–2.16) | 0.57 (0.44–0.73) | *** |

Note: ACE = adverse childhood experiences; ACHE = adverse childhood health experiences; CSC = childhood socioeconomic conditions; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratios. All models are adjusted for sex, birth cohort and attrition. Age was centered at 50 years and divided by 10 so that the coefficients yielded the effects for a 10-year period.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Table 4.

Associations of Childhood Misfortune and Adult-Life Socioeconomic Circumstances with Level and Trajectories of Poor Self-Rated Health at Old Age Stratified by Southern and Eastern European Welfare Regime

| Southern European | Eastern European | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 6,891 | N = 3,237 | |||||||

| M1b | M2b | M1b | M2b | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age (10-year period) | 3.14 (2.76–3.56) | *** | 2.85 (2.16–3.77) | *** | 1.52 (1.24–1.85) | *** | 1.87 (1.27–2.74) | ** |

| At least one ACE (ref. None) | 1.98 (1.46–2.68) | *** | 1.65 (1.22–2.22) | ** | 1.51 (1.02–2.21) | * | 1.44 (0.99–2.11) | |

| At least one ACHE (ref. None) | 2.03 (1.53–2.70) | *** | 2.06 (1.56–2.73) | *** | 1.70 (1.21–2.38) | ** | 1.51 (1.09–2.11) | * |

| CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Disadvantaged | 0.86 (0.64–1.14) | 1.01 (0.76–1.35) | 0.76 (0.50–1.16) | 1.06 (0.69–1.62) | ||||

| Middle | 0.48 (0.35–0.65) | *** | 0.76 (0.55–1.05) | 0.23 (0.15–0.33) | *** | 0.40 (0.27–0.61) | *** | |

| Advantaged | 0.35 (0.23–0.55) | *** | 0.77 (0.49–1.23) | 0.14 (0.08–0.24) | *** | 0.31 (0.18–0.53) | *** | |

| Most advantaged | 0.40 (0.15–1.08) | 1.24 (0.45–3.39) | 0.25 (0.07–0.92) | * | 0.70 (0.19–2.58) | |||

| Education (ref. Primary) | ||||||||

| Secondary | 0.47 (0.36–0.61) | *** | 0.48 (0.33–0.71) | *** | ||||

| Tertiary | 0.17 (0.11–0.27) | *** | 0.38 (0.19–0.74) | ** | ||||

| Main Occupational Position (ref. High skill) | ||||||||

| Low skill | 0.86 (0.58–1.27) | 1.69 (1.11–2.56) | * | |||||

| Never worked | 0.57 (0.36–0.90) | * | 1.21 (0.42–3.45) | |||||

| Financial strain (ref. Easily) | ||||||||

| Fairly easily | 1.08 (0.75–1.55) | 1.54 (0.96–2.48) | ||||||

| With some difficulty | 1.49 (1.05–2.11) | * | 2.22 (1.38–3.56) | ** | ||||

| With great difficulty | 2.19 (1.49–3.22) | *** | 5.92 (3.37–10.38) | *** | ||||

| Interactions | ||||||||

| Age × at least one ACE (ref. None) | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) | 0.99 (0.86–1.13) | 0.86 (0.70–1.06) | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | ||||

| Age × at least one ACHE (ref. None) | 0.83 (0.72–0.96) | * | 0.81 (0.70–0.94) | ** | 0.76 (0.62–0.92) | ** | 0.80 (0.66–0.97) | * |

| Age × CSC (ref. Most disadvantaged) | ||||||||

| Age × Disadvantaged | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 0.95 (0.83–1.08) | 0.93 (0.74–1.15) | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) | ||||

| Age × Middle | 1.02 (0.87–1.18) | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 1.20 (0.98–1.48) | 1.10 (0.88–1.37) | ||||

| Age × Advantaged | 1.09 (0.86–1.37) | 0.95 (0.75–1.21) | 1.23 (0.91–1.66) | 1.07 (0.78–1.46) | ||||

| Age × Most advantaged | 0.85 (0.52–1.37) | 0.75 (0.46–1.24) | 0.67 (0.31–1.43) | 0.53 (0.25–1.14) | ||||

| Age × Education (ref. Primary) | ||||||||

| Age × Secondary | 1.11 (0.97–1.26) | 1.20 (0.98–1.47) | ||||||

| Age × Tertiary | 1.30 (1.00–1.69) | 1.23 (0.85–1.79) | ||||||

| Age × Main occupational position (ref. High skill) | ||||||||

| Age × Low skill | 0.98 (0.79–1.21) | 0.84 (0.66–1.07) | ||||||

| Age × Never worked | 1.11 (0.87–1.40) | 1.02 (0.61–1.70) | ||||||

| Age × Financial strain (ref. Easily) | ||||||||

| Age × Fairly easily | 1.02 (0.85–1.21) | 0.83 (0.64–1.07) | ||||||

| Age × With some difficulty | 1.09 (0.92–1.30) | 0.86 (0.67–1.11) | ||||||

| Age × With great difficulty | 1.08 (0.89–1.30) | 0.80 (0.58–1.11) |

Note: ACE = adverse childhood experiences; ACHE = adverse childhood health experiences; CI = confidence interval; CSC = childhood socioeconomic conditions; OR = odds ratios. All models are adjusted for sex, birth cohort and attrition. Age was centered at 50 years and divided by 10 so that the coefficients yielded the effects for a 10-year period.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Finally, Models 3a and 3b correspond to Models 2a and 2b with the addition of the “living with a partner” and “unhealthy behavior index” covariates (without interactions, see Supplementary Material for variable description) to examine the independent effect of childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC on poor SRH as prior research has shown that these covariates influence SRH (Supplementary Table S2, see Supplementary Material; Cullati et al., 2014; Knöpfli, Cullati, Courvoisier, Burton-Jeangros, & Perrig-Chiello, 2016; Sieber et al., 2019).

In line with previous research (Sieber et al., 2019), we adjusted all models for three prior confounders; participant attrition [no dropout/dropout (participants who did not respond to Waves 5 and 6)/death [participants who died during follow-up]), sex (male/female), and birth cohort (1919–1928/1929–1938 [Great Depression]/1939–1945 [World War-II]/post-1945).

Finally, we performed sensitivity analyzes excluding observations for participants (a) older than 90 years because the descriptive statistics showed that observations above this age were few, (b) participants who died during the survey, (c) and participants who dropped out. Additionally, we ran the models including a variable for number of waves interviewed replacing the attrition variable described above as well as using a stricter coding of the drop out modality including nonresponse in Waves 4, 5, and 6. The sensitivity analyzes revealed consistent results with those of the main analyzes presented in the following section and did not indicate deviating findings due to very old participants or attrition. In addition, we performed two robustness analyzes, in which (a) we ran the same models treating the SRH item as a continuous variable ranging from 0, excellent to 4, poor SRH as well as (b) treating it as an ordinal variable to perform ordinal logistic regressions (data available upon request).

Results

Participants’ Characteristics

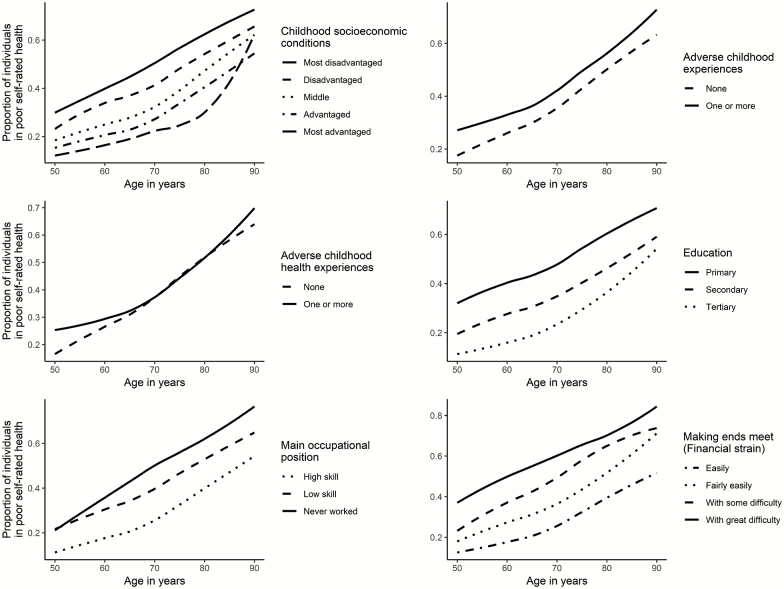

The final sample used for the models included 24,004 respondents (56% female); 3,626 (15.1%) in Scandinavian, 10,250 (42.7%) in Bismarckian, 6,891 (28.7%) in Southern European, and 3,237 (13.5%) in Eastern European welfare regimes (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Material). At baseline, respondents with poor SRH were on average older than respondents with good SRH. The higher the childhood misfortune, the higher the proportion of respondents with poor SRH. Similarly, the more disadvantaged the adult-life SEC, the higher the proportion of respondents with poor SRH. The proportion of respondents with poor SRH was the highest in Eastern European welfare regime (50.5%), followed by Southern European (33.5%), Bismackian (25.3%), and Scandinavian welfare regime (14.6%) (Supplementary Table S1). In Figure 1, we plotted the observed evolution of poor SRH proportions with aging for each childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC variable. In general, these descriptive trajectories show a rather parallel evolution up until the age of 70 and thereafter a narrowing pattern between the categories.

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics

| Good SRH | Poor SRH | |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Total | 16,939 (70.6) | 7,065 (29.4) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 61.3 (8.7) | 65.3 (9.6) |

| Scandinavian WR | 3,096 (85.4) | 530 (14.6) |

| Bismarckian WR | 7,657 (74.7) | 2,593 (25.3) |

| Southern European WR | 4,583 (66.5) | 2,308 (33.5) |

| Eastern European WR | 1,603 (49.5) | 1,634 (50.5) |

| ACE: None | 13,637 (72.1) | 5,268 (27.9) |

| ACE: At least one | 3,302 (64.8) | 1,797 (35.2) |

| ACHE: None | 12,697 (70.8) | 5,244 (29.2) |

| ACHE: At least one | 4,242 (70) | 1,821 (30) |

| CSC: Most disadvantaged | 2,492 (55.2) | 2,019 (44.8) |

| CSC: Disadvantaged | 3,979 (65.9) | 2,063 (34.1) |

| CSC: Middle | 5,785 (75.1) | 1,922 (24.9) |

| CSC: Advantaged | 3,536 (80.3) | 867 (19.7) |

| CSC: Most advantaged | 1,147 (85.5) | 194 (14.5) |

| Education | ||

| Primary | 4,108 (56.4) | 3,180 (43.6) |

| Secondary | 8,908 (73.6) | 3,188 (26.4) |

| Tertiary | 3,923 (84.9) | 697 (15.1) |

| Main occupational position | ||

| High skill | 4,439 (82.2) | 964 (17.8) |

| Low skill | 11,303 (68.3) | 5,245 (31.7) |

| Never worked | 1,197 (58.3) | 856 (41.7) |

| Financial strain | ||

| Easily | 7,294 (81.7) | 1,634 (18.3) |

| Fairly easily | 5,216 (71.1) | 2,120 (28.9) |

| With some difficulty | 3,147 (60.5) | 2,058 (39.5) |

| With great difficulty | 1,282 (50.6) | 1,253 (49.4) |

| Partnership status: Alone | 3,831 (64.1) | 2,143 (35.9) |

| Partnership status: In couple | 13,108 (72.7) | 4,922 (27.3) |

| Unhealthy behavior index, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.3 (0.3) |

| Female | 9,176 (68.3) | 4,259 (31.7) |

| Male | 7,763 (73.5) | 2,806 (26.5) |

| Birth cohort | ||

| After 1945 | 8,126 (77.6) | 2,339 (22.4) |

| Between 1919 and 1928 | 1,274 (53.7) | 1,098 (46.3) |

| Between 1929 and 1938 | 3,526 (62.7) | 2,096 (37.3) |

| Between 1939 and 1945 | 4,013 (72.4) | 1,532 (27.6) |

| Attrition: No dropout | 12,583 (73.6) | 4,510 (26.4) |

| Attrition: Dropped | 3,302 (70) | 1,412 (30) |

| Attrition: Deceased | 1,054 (48) | 1,143 (52) |

Note: ACE = adverse childhood experiences; ACHE = adverse childhood health experiences; CSC = childhood socioeconomic conditions; SRH = self-rated health; WR = welfare regime.

Figure 1.

Descriptive plot of observed evolution of poor self-rated health proportions by age by childhood misfortune and adult-life socioeconomic conditions.

Association of Childhood Misfortune with Levels and Trajectories of Poor Self-Rated Health in Old Age, Objective 1 (Model 1a)

In Model 1a, we found that all three childhood misfortune predictors (CSC, ACE, and ACHE) were associated with differences in the levels of SRH at the beginning of the trajectory (i.e., age 50), with more disadvantaged categories consistently having higher odds of poor SRH in old age across predictors than less disadvantaged categories (Table 2). The model revealed no differing linear trajectories of poor SRH with aging by ACE and CSC categories. For ACHE, however, the interaction term with age revealed that the linear decline of poor SRH with aging for respondents that had at least one ACHE was less steep compared with those who had no ACHE.

Accumulation of Disadvantage Over the Life Course, Objective 2 (Model 2a)

Education, main occupational position, and financial strain were associated with the level of SRH at the beginning of the trajectory, with more disadvantaged categories consistently having higher odds of poor SRH at age 50 than less disadvantaged categories (Model 2a; Table 2). A significant interaction term revealed narrowing differences with aging between primary and tertiary education, but no change in trajectories between primary and secondary education. For main occupational position, we observed narrowing differences between high and low skill occupations as people grow older in the association with poor SRH. The trajectories between those that never worked and those with high occupational position were, however, not different with aging. For financial strain, the interaction terms did not reveal differences in the trajectories with aging.

The associations of the childhood misfortune predictors with level and trajectories of poor SRH in old age stayed significant when adjusting for adult-life SEC and covariates (Model 2a). The results remained unchanged after full adjustment with partnership status and the unhealthy behavior index (Supplementary Table S2, see Supplementary Material).

Moderation of Childhood Misfortune and Adult-Life SEC Associations with Poor Self-Rated Health by Welfare Regimes, Objective 3

In terms of level of poor SRH at age 50, results revealed the associations between CSC and poor SRH differed across welfare regimes (Tables 3 and 4, Supplementary Material). While in Scandinavian (Table 3) and Southern European welfare regime (Table 4), the association became nonsignificant with the addition of adult-life SEC (Model 2b, with the exception of most advantaged in Scandinavian), the association stayed significant in Bismarckian (Table 3) and Eastern European welfare regimes (Table 4, though with less marked differences between the CSC categories compared to Model 1b). The associations between ACE and ACHE with poor SRH did not differ across welfare regimes. However, the associations between education and main occupational position (but not financial strain) and poor SRH were different across welfare regimes (Tables 3 and 4, Model 2b). The results revealed no association of education with poor SRH in the Scandinavian welfare regime, whereas, there was an expected gradient in the other welfare regimes. Low main occupational position was associated with higher levels of poor SRH when compared to high occupational position across welfare regimes, except in the Southern European regime. Never having done paid work was associated with higher levels of poor SRH in Bismarckian welfare regime when compared to high main occupational position, while in the Southern European welfare regime it was associated with lower levels of poor SRH. In Scandinavian and Eastern European regimes, never having done paid work was not associated with SRH. Financial strain was consistently associated with poor SRH across welfare regimes, with more disadvantaged categories showing higher levels of poor SRH (Tables 3 and 4, Model 2b).

In terms of trajectories of poor SRH with aging, we found no differences between the CSC and ACE categories across welfare regimes (Tables 3 and 4), but the association between ACHE and SRH trajectories did differ across welfare regimes. In Southern and Eastern European welfare regimes, respondents who experienced one or more ACHE had a less steep increase of poor SRH with aging when compared to those who did not experience ACHE. Furthermore, associations of adult-life SEC with SRH trajectories differed across welfare regimes (Tables 3 and 4). The SRH trajectories between the various categories of education were not different within Scandinavian, Southern, and Eastern European welfare regimes. However, in the Bismarckian welfare regime, respondents with tertiary education had a steeper increase of poor SRH with aging when compared to primary education. Respondents with low-skill main occupational position in the Scandinavian welfare regime had a less steep increase of poor SRH with aging when compared to high-skill occupational position. Across other welfare regimes, main occupational position did not show differing trajectories with aging between the different categories. Respondents with great difficulty making ends meet in the Bismarckian welfare regime had a less steep increase of poor SRH with aging when compared to those who could make ends meet easily. Across the other welfare regimes, SRH trajectories between categories of financial strain were not different with aging.

Full adjustment of the models with partnership status and unhealthy behavior index did not change the results on level and trajectories of poor SRH (Supplementary Table S2, Supplementary Material).

In the robustness analyzes, the models with a continuous and ordinal SRH outcome variable showed consistent results with the models including a binary outcome. In addition, we observed supplementary age-predictor interactions (trajectories) that supported the findings described above with one exception: In Scandinavian welfare regimes, respondents with secondary and tertiary education had a less steep increase of poor SRH with aging compared to respondents with primary education.

Discussion

The main results of this cross-national and longitudinal study examining the associations of childhood misfortune, adult-life SEC, and welfare regime with SRH in old age are multifaceted. Independent from welfare regime, the results showed a persistent and graded association of childhood misfortune (objective 1) and adult-life SEC (objective 2) with the level of SRH, which is in line with the CDA model. The more disadvantaged respondents showed poorer SRH at the age of 50. According to the CDA model, a potential explanation for these differences could be the accumulation of disadvantages over the life course up until the age of 50. For SRH trajectories, we found that for ACHE (objective 1), education, and main occupational position (objective 2), differences in SRH between the various categories diminished with aging. Thus, when testing the hypothesis of the CDA model to health trajectories in the second half of life (50–96 years), we observed that differences in SRH diminished over time in the case of ACHE, education, and main occupational position or were maintained on the same level in the case of CSC, ACE, and financial strain. Figure 1 suggests that while the pattern of narrowing differences starts already at the beginning of the observed period for ACHE, the education and main occupational position categories seemed to approach each other from around 70 years on. These findings are in line with the age-as-leveler hypothesis, which states that differences decrease in old age due to mortality selection. Furthermore, the results showed that adult-life SEC did not explain the associations of childhood misfortune with levels of SRH, which hint at a cumulative life-course effect of adult-life SEC on the differences at age 50 in addition to the effects of childhood.

When looking at differences in the associations with levels of SRH across welfare regimes (objective 3), ACE, ACHE, and financial strain were similarly associated with more disadvantaged categories presenting poorer SRH. A potential explanation for the level differences in these latter variables could be the accumulation of disadvantages in the life course up until age 50, which seemed to lead to similar results across welfare regimes. In contrast, CSC, education, and main occupational position showed varying patterns. The persistent associations of ACE and ACHE across welfare regimes as opposed to the varying associations of CSC may be the result of the welfare regimes’ main focus on adult-life factors such as pensions and unemployment benefits rather than directly experienced childhood adversities. Since CSC is measured through parental socioeconomic circumstances and ACE and ACHE through personal experiences, this may explain the differences in the associations. In the Southern European welfare regimes, adult-life SEC seemed to explain the association between CSC and SRH, suggesting that the accumulation of disadvantage from CSC could be compensated by better outcomes in adult-life SEC. This may be the result of the expansion of welfare benefits in these welfare regimes, which mainly occurred during adult life for the included cohorts in this study (Ferrera, 1996). Education was associated with better SRH across welfare regimes, except for the Scandinavian welfare regimes where no association was found, suggesting a positive effect of more generous and redistributive welfare policies. Scandinavian countries are known to invest a significant share of their GDP in their educational system with the aim of ensuring equal access regardless of parents’ status or income. Similarly, low main occupational position was associated with poorer SRH across welfare regimes, but seemed not to play a role in Southern European welfare regime. This result can be explained by differences in employment policies, family solidarity, and informal economy across European countries. In Southern European countries, workers’ social protection, as well as comprehensive unemployment policies, developed quickly over the past decades (Karamessini, 2007). Moreover, people living in these countries—as well as in northern welfare regimes—can more frequently rely on intergenerational solidarity within their families compared to countries in other welfare regimes (Daatland & Lowenstein, 2005). Such solidarity within families provide people with significant additional socioeconomic resources which can compensate adversities in the life course, such as temporary job loss. In addition, familial solidarity can help building up substantial socioeconomic reserves (through financial support, heritage, or logistic support) that protect individuals from adverse events and shocks, which are linked with the development of vulnerability (Cullati, Kliegel, & Widmer, 2018).

With regard to the comparison of SRH trajectories in the age range from 50 to 96 years across welfare regimes (objective 3), we found narrowing differences with aging for ACHE in Southern and Eastern European welfare regimes, which is in line with the age-as-leveler hypothesis. In other words, poor health in childhood continues to fuel health inequality in the second half of life in Bismarckian and Scandinavian welfare regimes, by maintaining health differences despite aging. In Southern and Eastern welfare regimes this inequality-generative process stopped influencing the trajectories, as differences narrowed. We have no explanation for this result, except for potential health selection bias, which could influence our findings through selection by design (respondents included in aging study) and attrition during follow-up. For the other childhood misfortune variables, we found no differing trajectories across welfare regimes. For adult-life SEC, the results showed narrowing differences with aging between primary and tertiary education in the Bismarckian welfare regime. Similarly, we found narrowing differences between low and high main occupational position within the Scandinavian welfare regime, as well as between having no and great difficulties making ends meet with household income in the Bismarckian regimes. These findings can be explained by the age-as-leveler hypothesis, which states that differences decrease with aging due to mortality selection.

Compared to previous literature, this study made use of comprehensive measures of childhood misfortune, rather than focusing on a single indicator, in order to test trajectories in SRH with aging. Our results are in line with the research of Sieber et al., 2019, which did not find robust effects of CSC on SRH trajectories with aging (starting from age 50). Here, we extended these results by analyzing two additional measures of childhood misfortune, ACE and ACHE. We found ACHE is associated with narrowing SRH differences with aging in Southern and Eastern European welfare regimes. Other studies on CDA and SRH did not consider childhood predictors (Cullati et al., 2014; Mirowsky & Ross, 2008) and/or analyzed CDA patterns in stages earlier than old age (Bauldry et al., 2012). A study with the same data and analysis outline but using frailty as the outcome measure, found similar patterns in the associations of childhood misfortune and adult-life SEC with the level of the outcome (Van Der Linden et al., 2019). However, in addition to the narrowing differences in the trajectories of the various ACHE categories, the study on frailty also found narrowing trajectories by CSC categories. Moreover, the article on frailty also found growing differences between low and high main occupational position in the Bismarckian welfare regime. This underlines the importance of considering various outcomes when studying the CDA theory (Van Der Linden et al., 2019). When looking at economic inequality in later life, existing research found that inequality within each cohort kept increasing with aging as well as between cohort inequalities, with higher economic inequality for younger cohorts (Crystal et al., 2017; Crystal & Waehrer, 1996). The longitudinal finding stating increasing inequality throughout the life course is contrary to our findings of narrowing health inequalities in old age. However, Crystal and Waehrer (1996) and Crystal and colleagues (2017) looked at economic rather than health inequality and used United States–based data for their studies. Ferraro and Kelley-Moore (2003) have shown that obesity has long-lasting health consequences during adulthood. By employing a life-course reflexivity approach they found that these detrimental effects could be compensated through regular exercise. Although this study did not take into account potential macro-level influences on the associations, it showed the importance of considering experiences across the life course. In our study, we found that in Southern welfare regimes the detrimental effect of CSC could be compensated by adult-life SEC. Another study that looked at cross-national differences in the impact of childhood health and SEC on later-life health found a long lasting negative impact independent of adult-life SEC and behavioral factors and that this impact varies substantially across contexts, which is consistent with our study (Haas & Oi, 2018). However, this study did not look into health trajectories at older age.

The strengths of this study include a follow-up of 12 years with repeated measurements every 2 years, which allowed for an analysis of the SRH trajectories in different life-course events and socioeconomic circumstances from age 50. In addition, the large sample size including respondents from different European countries, combined with comprehensive childhood misfortune indicators and adult-life SEC predictors allowed for a comparative analysis of the CDA framework on a macro-level across welfare regime. However, one limitation is the self-reported and retrospective data used for childhood misfortune and main occupational position, which may be subject to recall bias, common source bias, or social desirability. Nevertheless, previous research has shown adequate validity for recall measures of adverse experiences and SEC (Barboza Solís et al., 2015), and for childhood health (Haas & Bishop, 2010), especially as the models were adjusted with its predictors, such as socioeconomic resources (Vuolo, Ferraro, Morton, & Yang, 2014). Second, as an inevitable characteristic of a longitudinal study, attrition may imply a selection bias in the remaining sample. By adjusting our models for attrition and conducting sensitivity analyzes excluding respondents who dropped out or died during follow-up, we accounted for this potential limitation. Third, as a subjective assessment of health in a cross-country study, SRH may be sensitive to the respondent’s cultural context. However, previous research found that in a European context differences in reporting styles explained some part of the cross-country variations but did not eliminate them (Hardy, Acciai, & Reyes, 2014). Fourth, due to data limitation and study design the countries included in the analyzes represent a selected sample and might bias the findings. Fifth, a robustness analysis using a continuous SRH outcome variable confirmed the above results. In addition, the continuous models revealed supplementary significant differences in SRH trajectories. We observed growing differences with aging between respondents with primary and tertiary education in Scandinavian welfare regimes only, which supports the CDA theory. However, these supplementary results can be explained by the fact that in the continuous case respondents move more easily between the response categories compared to the dichotomous case. Given that SRH is not a genuine linear variable with the same distance between the response categories, these results need to be looked at with caution. The binary SRH outcome gives a more clinical and reliable assessment of the respondent’s health by better dissociating good and poor health.

In conclusion, this study reveals the long-lasting consequences of childhood misfortune on health in old age and shows narrowing differences between ACHE categories over time in old age, which was driven by the effects in Southern and Eastern European welfare regimes. Furthermore, the present research underlines the importance of a life-course approach following the principle of life-course reflexivity, by considering adult-life SEC when examining the associations between childhood misfortune and health in old age. Similar to childhood misfortune, disadvantaged SEC in adult-life were associated with poorer health in old age. We observed narrowing differences over time in old age for the various categories of education, which was due to the effects in the Bismarckian welfare regime, and for main occupational position, which was due to the effects in the Scandinavian welfare regime.

Generally, we found that CDA processes before the age of 50 may explain the health differences in the studied categories up until that age. However, we did not find support for growing differences over time in old age (after 50) in the studied life-course characteristics as proposed by the CDA model but rather narrowing differences across these variables, which seemed to be specifically marked from 70 years on as Figure 1 suggests. The evidence for old-age trajectories in this study are in line with alternative hypotheses to the cumulative dis/advantage theory, such as the age-as-leveler hypothesis, stating that differences in old age decrease due to mortality selection, which leads to a more homogenous population in these age groups (Lynch, 2003). Another potential explanation for these findings may be that welfare regimes prevented CDA processes to continue their path in old age. However, future research is needed to confirm this explanation, as we did not test the “absence” of welfare regimes. This study underlines the importance to consider various analysis levels and life-course stages when examining CDA processes, as the individual life course on the micro-level seems to be influenced by social policies on the macro-level. Further research will be needed to carefully work out the causes for the differences between welfare regimes in order to identify robust policy conclusions from these findings.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research “LIVES – Overcoming vulnerability: Life course perspectives,” which is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant no. 51NF40-160590). The authors are grateful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for its financial assistance. B. Cheval is supported by an Ambizione grant (PZ00P1_180040) from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant (agreement number 676060 [LONGPOP] to B. W. A. van der Linden).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Michele Pellizzari for his invaluable methodological support he has provided in the review process of this article. This article uses data from SHARE Waves 1, 2, 3 (SHARELIFE), 4, 5, and 6 (DOIs: 10.6103/SHARE.w1.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w2.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w3.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w4.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w5.600, 10.6103/SHARE.w6.600). The SHARE data collection was primarily funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006–062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005–028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006–028812) and FP7 (SHARE-PREP: no. 211909, SHARE-LEAP: no. 227822, SHARE M4: N°261982). The authors gratefully acknowledge additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the US National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C), and various national funding sources (see www.share-project.org).

Author contributions: S. Sieber, B. Cheval, B.W.A. van der Linden, and S. Cullati designed the analyses. S. Sieber, B. Cheval, D. Orsholits, and B.W.A. van der Linden analyzed the data. S. Sieber drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Aartsen, M. J., Cheval, B., Sieber, S., Linden, B. W. V. der, Gabriel, R., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Advantaged socioeconomic conditions in childhood are associated with higher cognitive functioning but stronger cognitive decline in older age. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116(12), 5478–5486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807679116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambra, C., & Eikemo, T. A. (2009). Welfare state regimes, unemployment and health: A comparative study of the relationship between unemployment and self-reported health in 23 European countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63(2), 92. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barboza Solís, C., Kelly-Irving, M., Fantin, R., Darnaudéry, M., Torrisani, J., Lang, T., & Delpierre, C. (2015). Adverse childhood experiences and physiological wear-and-tear in midlife: Findings from the 1958 British birth cohort. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112, E738–E746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417325112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, M., Blane, D., & Montgomery, S. (1997). Health and the life course: Why safety nets matter. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 314, 1194–1196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7088.1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauldry, S., Shanahan, M. J., Boardman, J. D., Miech, R. A., & Macmillan, R. (2012). A life course model of self-rated health through adolescence and young adulthood. Social Science & Medicine, 75(7), 1311–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan, A., Brandt, M., Hunkler, C., Kneip, T., Korbmacher, J., Malter, F., . . . Zuber, S.; SHARE Central Coordination Team . (2013). Data Resource Profile: The Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). International Journal of Epidemiology, 42, 992–1001. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Jeangros, C., Cullati, S., Sacker, A., & Blane, D. (2015). A life course perspective on health trajectories and transitions. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-20484-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval, B., Chabert, C., Orsholits, D., Sieber, S., Guessous, I., Blane, D., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Disadvantaged early-life socioeconomic circumstances are associated with low respiratory function in older age. The Journals of Gerontology, Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical sciences, 74(7), 1134–1140. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gly177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval, B., Chabert, C., Sieber, S., Orsholits, D., Cooper, R., Guessous, I., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Association between Adverse childhood experiences and muscle strength in older age. Gerontology, 65, 474–484. doi: 10.1159/000494972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheval, B., Orsholits, D., Sieber, S., Stringhini, S., Courvoisier, D., Kliegel, M., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Early-life socioeconomic circumstances explain health differences in old age, but not their evolution over time. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 73, 703–711. doi: 10.1136/jech-2019-212110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian, L. M., Glaser, R., Porter, K., Malarkey, W. B., Beversdorf, D., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2011). Poorer self-rated health is associated with elevated inflammatory markers among older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(10), 1495–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, S., Shea, D. G., & Reyes, A. M. (2017). Cumulative advantage, cumulative disadvantage, and evolving patterns of late-life inequality. The Gerontologist, 57, 910–920. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal, S., & Waehrer, K. (1996). Later-life economic inequality in longitudinal perspective. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51B(6), S307–S318. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51B.6.S307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullati, S., Kliegel, M., & Widmer, E. (2018). Development of reserves over the life course and onset of vulnerability in later life. Nature Human Behaviour, 2, 551–558. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0395-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullati, S., Rousseaux, E., Gabadinho, A., Courvoisier, D. S., & Burton-Jeangros, C. (2014). Factors of change and cumulative factors in self-rated health trajectories: A systematic review. Advances in Life Course Research, 19(Supplement C), 14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daatland, S. O., & Lowenstein, A. (2005). Intergenerational solidarity and the family-welfare state balance. European Journal of Ageing, 2, 174–182. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0001-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer, D. (1987). Aging as intracohort differentiation: Accentuation, the Matthew effect, and the life course. Sociological Forum, 2(2), 211–236. doi: 10.1007/BF01124164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58(6), S327–S337. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.S327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer, D. (2018). Systemic and reflexive: Foundations of cumulative dis/advantage and life-course processes. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSalvo, K. B., Bloser, N., Reynolds, K., He, J., & Muntner, P. (2006). Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00291.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikemo, T.A., Bambra, C., Judge, K., & Ringdal, K. (2008). Welfare state regimes and differences in self-perceived health in Europe: A multilevel analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 66(11), 2281–2295. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eikemo, T.A., Huisman, M., Bambra, C., & Kunst, A. E. (2008). Health inequalities according to educational level in different welfare regimes: A comparison of 23 European countries. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(4), 565–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01073.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). Three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., . . . Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera, M. (1996). The “Southern Model” of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 17–37. doi.org/10.1177/095892879600600102 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, K. F., & Kelley-Moore, J. A. (2003). Cumulative disadvantage and health: Long-term consequences of obesity? American Sociological Review, 68, 707–729. doi: 10.2307/1519759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, L. K., Breiding, M. J., Merrick, M. T., Thompson, W. W., Ford, D. C., Dhingra, S. S., & Parks, S. E. (2015). Childhood adversity and adult chronic disease: An update from ten states and the District of Columbia, 2010. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 48, 345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, S. A. (2007). The long-term effects of poor childhood health: An assessment and application of retrospective reports. Demography, 44(1), 113–135. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, S. A., & Bishop, N. J. (2010). What do retrospective subjective reports of childhood health capture? Evidence from the Wisconsin longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 32(6), 698–714. doi: 10.1177/0164027510379347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas, S. A., & Oi, K. (2018). The developmental origins of health and disease in international perspective. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 213, 123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, M. A., Acciai, F., & Reyes, A. M. (2014). How health conditions translate into self-ratings: A comparative study of older adults across Europe. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 55, 320–341. doi: 10.1177/0022146514541446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, M., Jakub, H., Melchior, M., Van Oort, F., & Weyers, S. (2006). Comparison of the effects of low childhood socioeconomic position and low adulthood socioeconomic position on self rated health in four European studies. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60, 882–886. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamessini, M. (2007). The Southern European social model: Changes and continuities in recent decades. International Institute for Labour Studies. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---inst/documents/publication/wcms_193518.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Knöpfli, B., Cullati, S., Courvoisier, D. S., Burton-Jeangros, C., & Perrig-Chiello, P. (2016). Marital breakup in later adulthood and self-rated health: A cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. International Journal of Public Health, 61, 357–366. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0776-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landös, A., von Arx, M., Cheval, B., Sieber, S., Kliegel, M., Gabriel, R., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Childhood socioeconomic circumstances and disability trajectories in older men and women: A European cohort study. European Journal of Public Health, 29(1), 50–58. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, S. M. (2003). Cohort and life-course patterns in the relationship between education and health: A hierarchical approach. Demography, 40(2), 309–331. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, J. M., Meara, E., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2010). Commentary: Assessing the health effects of Medicare coverage for previously uninsured adults: A matter of life and death? Health Services Research, 45, 1407–22; discussion 1423. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01085.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2008). Education and self-rated health: Cumulative advantage and its rising importance. Research on Aging, 30(1), 93–122. doi: 10.1177/0164027507309649 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson, R. M., Tucker-Seeley, R., Goldman, D., & Lakdawalla, D. N. (2019). Does Medicare Coverage Improve Cancer Detection and Mortality Outcomes? (Working Paper No. 26292). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi: 10.3386/w26292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien Cousins, S. (1997). Validity and reliability of self‐reported health of persons aged 70 and older. Health Care for Women International, 18(2), 165–174. doi: 10.1080/07399339709516271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rand, A. M. (2009). Cumulative processes in the life course. In The craft of life course research (pp. 121–140). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Power, C., & Peckham, C. (1990). Childhood morbidity and adulthood ill health. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 44(1), 69–74. doi: 10.1136/jech.44.1.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechel, B., Grundy, E., Robine, J. M., Cylus, J., Mackenbach, J. P., Knai, C., & McKee, M. (2013). Ageing in the European Union. Lancet (London, England), 381, 1312–1322. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62087-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, M. H., & Ferraro, K. F. (2012). Childhood misfortune as a threat to successful aging: Avoiding disease. The Gerontologist, 52, 111–120. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, M. H., Ferraro, K. F., & Mustillo, S. A. (2011). Children of misfortune: Early adversity and cumulative inequality in perceived life trajectories. American Journal of Sociology, 116(4), 1053–1091. doi: 10.1086/655760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieber, S., Cheval, B., Orsholits, D., Van der Linden, B. W., Guessous, I., Gabriel, R., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Welfare regimes modify the association of disadvantaged adult-life socioeconomic circumstances with self-rated health in old age. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(4), 1352–1366. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyy283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Straat, V., Cheval, B., Schmidt, R. E., Sieber, S., Courvoisier, D., Kliegel, M., . . . Bracke, P. (2018). Early predictors of impaired sleep: A study on life course socioeconomic conditions and sleeping problems in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 24, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1534078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Linden, B. W. A., Sieber, S., Cheval, B., Orsholits, D., Guessous, I., Gabriel, R., . . . Cullati, S. (2019). Life-course circumstances and frailty in old age within different European welfare regimes: A longitudinal study with SHARE. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuolo, M., Ferraro, K. F., Morton, P. M., & Yang, T.-Y. (2014). Why do older people change their ratings of childhood health? Demography, 51(6), 1999–2023. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0344-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahrendorf, M., & Blane, D. (2015). Does labour market disadvantage help to explain why childhood circumstances are related to quality of life at older ages? Results from SHARE. Aging & Mental Health, 19(7), 584–594. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.938604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.