Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this descriptive study was to examine Appalachian stakeholder attitudes toward routine memory screening, and to compare and contrast results from a similar study conducted in an ethnically diverse rural Florida cohort. Determining perceptions about memory screening is essential prior to developing culturally relevant programs for increasing early dementia detection and management among rural underserved older adults at risk of cognitive impairment. Benefits of early detection include ruling out other causes of illness and treating accordingly, delaying onset of dementia symptoms through behavior management and medications, and improving long-term care planning (Dubois, Padovani, Scheltens, Rossi, & Dell’Agnello, 2016). These interventions can potentially help to maintain independence, decrease dementia care costs, and reduce family burdens (Frisoni, et al., 2017).

Method:

Researchers applied a parallel mixed method design (Tashakkori & Newman, 2010) of semi-structured interviews, measurements of health literacy (REALM-SF) (Arozullah, et al., 2007), sociodemographics, and cognitive screening perceptions (PRISM-PC) (Boustani, et al., 2008), to examine beliefs and attitudes about memory screening among 22 FL and 21 WV rural stakeholders (residents, health providers, and administrators).

Results:

Findings included that > 90% participants across both cohorts were highly supportive of earlier dementia detection through routine screening regardless of sample characteristics. However, half of those interviewed were doubtful that provider care or assistance would be adequate for this terminal illness. Despite previous concerns of stigma associated with an Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, rural providers are encouraged to educate patients and community members regarding Alzheimer’s disease and offer routine cognitive screening and follow-through.

Keywords: Rural, Appalachian, screening and diagnosis, Alzheimer’s disease

The Alzheimer’s Association estimates that 5.7 million Americans have Alzheimer’s disease (AD), yet over half report not being told of a diagnosis early in the disease process (Gaugler, James, Johnson, Marin, & Weuve, 2019). Delayed diagnosis and management contribute to sky-rocketing care costs associated with AD, which are predicted to reach over $1 trillion if current trends continue. This burden may be even higher in rural populations such as Appalachia, due to increasing numbers of older adults (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018), fewer providers, long distances to travel to specialty services (Gaugler et al., 2019), and less access to resources for health-related education (Mattos et al., 2017). Rural older Appalachian residents may also face a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) due to the prevalence of associated risk factors such as increased rates of obesity, smoking, diabetes, and midlife hypertension (Appalachian Region Commission, 2017). Related issues such as lack of access to care, nutrition/weight status, diabetes, and mental health/disorders were the first four health priorities identified by over 1,000 rural residents in 49 states surveyed nationally in establishing the Rural Healthy People 2020 (RHP2020) (Bolin et al., 2015).

To decrease ADRD care costs and societal burden, greater attention is now being given to increasing the public’s awareness regarding signs and symptoms of AD and the importance of early detection, diagnosis and initiation of treatment (Gaugler et al., 2019; National Institutes of Health, 2018). However, this attention has not been targeted specifically for underserved rural populations. As a consequence of limited awareness, rural older adults have low levels of cognitive health literacy leading toward further challenges in access to information related to memory changes (Wiese, Williams, & Tappen, 2014). Lack of knowledge of AD may contribute to rural residents’ misperceptions about the disease and or the disease process (Wiese, Williams, & Galvin, 2018a) such as beliefs that nothing can be done and fears about loss of independence. Rural providers have cited similar reasons they are often hesitant to screen for memory loss (Rosenbloom et al., 2018).

To correct these misconceptions, rural residents and providers need to be aware of the benefits of early detection, which include 1) ruling out other causes and treating them accordingly, 2) delaying the onset of more serious symptoms through behavior management and medications, and 3) improving long-term care planning (Dubois, Padovani, Scheltens, Rossi, & Dell’Agnello, 2015). Each of these interventions can help to maintain independence, decrease ADRD care costs, and reduce family burdens (Frisoni et al., 2017). Furthermore, there is a lack of knowledge among providers and the general rural population regarding the ability to screen for potential memory loss using brief, validated measures (Wiese, Williams,Tappen, & Newman 2019a; Wiese et al., 2017).

Dementia detection research in rural settings

The lack of attention to cognitive screening in rural populations is reflected in the scarcity of research available, a gap highlighted by several researchers (Abner, Jicha, Christian, & Schreurs, 2016; (Adler, Lawrence, Ounpraseuth, & Asghar-Ali, 2015; Martin et al., 2015; Meit et al., 2014; Morgan et al., 2019; Winblad et al., 2016). Studies are available which show a delay in diagnosis and treatment in rural versus urban populations. Abner et al. (2016) found that 2013 ADRD diagnoses were 11% lower (95% CI: 9%–13%) in Appalachian Kentucky and WV. In contrast, Matto et al. (2017) found that there was a greater time lapse between Pennsylvania urban dwellers’ symptoms to time of diagnosis. In a recent scoping review to investigate the incidence of dementia screening and detection among rural populations, Barth, Nickel, and Kolominsky-Rabas (2018) reported disappointing findings. Only 30 articles were discovered in four major databases (Cochrane Library, PsychInfo, PubMed, and Science Direct). Four delivery types of interventions were reported; telephone screenings, face-to face with providers, telehealth, or online/mobile applications, but sample sizes were small, were usually not tested explicitly in rural or remote settings, and only two were randomized controlled trials. Wiese, Williams, & Tappen (2014) conducted a literature review of barriers to cognitive screening in rural populations, and found that in the 206 abstracts reviewed, only six met the search criteria for rural barriers, and cognitive, memory, or dementia screening. In preparing this article, a new scan of literature in PubMed, Science Direct, and Google Scholar resulted in no further studies with the search terms beyond those mentioned above, other than one investigating Appalachian residents’ attitudes toward Alzheimer’s disease. Wiese and Williams (2018b) reported that West Virginia (WV) residents were hopeful about more effective treatment options, potential benefits of herbal intake as children, and that AD could be something potentially preventable through healthier living. Qualitative themes that emerged were “personal knowing of AD” and “preventing AD”. The researchers also concluded that recognizing cultural perceptions and addressing knowledge gaps by rural providers was needed to correct the misconceptions regarding routine cognitive screening for rural older adults at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

In a companion study to this one targeting a more ethnically diverse rural group (n = 21) including 22% Hispanic and 14% African American, Wiese, Williams, & Galvin (2018a) found that the majority of both lay resident and professional stakeholders were in favor of routine memory checks.

Recognizing that rural settings vary greatly across the nation (Bolin et al., 2015), the aim of this descriptive parallel mixed methods study was to examine a different cohort of stakeholders’ attitudes toward routine memory screening. The long-term goal of this research is to inform the development of future educational interventions for increasing routine memory screening among rural residents.

Methods

Setting and sample

WV is among the five oldest populations per capita in the country (United States Census Bureau, 2018). Study participants were sought from among those living or working in southern Nicholas County, WV, which holds the highest number of the state’s Medicare beneficiaries (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018). As is typical of Appalachia, this county is largely White (98%) and most (85%) graduated from high school, but the median household income was low at $39,000 in 2018 with a 20% poverty rate (United States Census Bureau, 2018). Recruitment sites for stakeholders included the local city hall, two senior centers, health care clinics, and faith-based organizations. Freeman’s (1994) classic definition of stakeholder is still applicable today (Andriof, Waddock, Husted, & Rahman, 2017) and can be viewed in terms of an individual or group who is affected by or who can influence the goals of a project or organization objectives (Freeman, 1994). The stakeholders who agreed to participate were comprised of two each: senior center administrators, senior center volunteer staff, health clinic administrators, law enforcement officers, emergency medical technicians, physicians, nurse practitioners, licensed practical nurses, paid caregivers, family caregivers, and residents.

Data collection procedures

Persons were eligible to participate in this study if they lived in the area at least ten years and were identified as stakeholders by the local clinic and senior center staff. One month prior to data collection, the study team sent invitations to participate through e-mails and phone calls. Exclusion criteria included the inability to speak or comprehend English, or a lack of familiarity with the topic of dementia, but neither circumstance arose during recruitment.

Quantitative measures

Quantitative measures included a sociodemographic survey, health literacy screen, the Rapid Estimate of Literacy in Medicine, short form (REALM-SF) by Arozullah et al. (2007), and the Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC) Scale (Boustani et al., 2008).

Sociodemographic survey

Questions in the sociodemographic survey included gender, sex, ethnicity, race, prior caregiver experience, years lived in the community, and if a health care provider had offered or conducted tests for memory loss in the past year. Participants were also asked if they would be willing to participate in a “check of their memory.”

Health literacy survey

Health literacy was also assessed as sociodemographic variable, as low scores are often an indicator of rural health disparities (Rikard, Thompson, McKinney, & Beauchamp, 2016). The REALM-SF health literacy test is comprised of a seven-word recognition exercise (Menopause, Antibiotics, Exercise, Jaundice, Rectal, Anemia, and Behavior). The REALM-SF has demonstrated strong reliability (Cronbach’s a = .91), (Cronbach, 1951) and validity in diverse settings (Rikard et al., 2016). To administer the REALM-SF, participants were asked to read aloud any words they recognized. A point was discreetly recorded for any words read correctly, with categorization by functional ability and grade level: No points recorded (0) indicated a score of third grade or lower. Persons scoring in this category need repeated oral instructions, audio/video tapes, and/or illustrated materials. A literacy score of 1–3 indicates a fourth-to-sixth grade level, requiring low-literacy level materials. Persons with scores between 4 and 6 (equivalent seventh to eighth grade of health literacy) can read many patienteducation materials, and possibly medication labels. The highest score of 7 indicates a 9th grade or higher level of ability in health literacy.

Perceptions regarding dementia screening

The PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) was designed to assist the researcher in evaluating participants’ attitudes regarding the benefits or harms of dementia screening. The PRISM-PC items can also aid in evaluating willingness to participate in screening. The PRISM-PC scale has been used in both primary and community care settings with over 800 patients, including those with lower health literacy (Fowler et al., 2015). The most recent study demonstrated similar and acceptable internal consistency as previous work (a = .85) including that of the subscales and constructs (Harrawood, Fowler, Perkins, LaMantia, & Boustani, 2018). The PRISM-PC items were scored on a Likert Scale of 1–5 ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5). Boustani et al. (2008) used varimax rotated-factor loadings to identify two scales: “potential harm or benefit in screening” and “acceptance of dementia screening.” Constructs emerging from the first scale included knowledge of dementia screening and being tested. Constructs under the second scale included negative impacts of screening on independence, suffering, stigma, and benefits (Boustani et al., 2008).

Qualitative interviews

Dates and times for the interviews were established with participants following confirmation of interest and study qualifications. The PI traveled to two senior centers, two rural health care clinics, two churches, two private business locales, and one police and fire rescue station. All data collection took place in a private office at these various settings. Participants signed informed consent following the procedures approved by the university’s institutional review board. Participants were asked to answer sociodemographic and health literacy surveys and six semi-structured interview questions which were recorded. The questions were designed through content validity indices and expert review and used successfully in an earlier study targeting an ethnically diverse population (Wiese, Williams, & Galvin, 2018a). These questions were:

What do you see as benefits to routine screening for AD for adults over age 65?

What ways would dementia screening be beneficial to family members/to the community?

What do you think may prevent people from seeking routine screening for AD in your community?

What are some negative consequences to the person or family in finding out that they have AD?

What other problems could result from screening for AD?

What fears do you have related to the subject of screening for memory loss?

Interviews were conducted until no novel responses or preliminary findings appeared, indicating saturation (Saunders et al., 2018). Immediately following each interview, stakeholders completed a quantitative measure regarding perceptions of testing for memory loss (Boustani et al., 2008).

The surveys and tape recorder were maintained in a locked briefcase and returned to the PI’s office, where the data were recorded in SPSS v24 (IBM, Armonk, NY) on a password protected computer with an encrypted server.

The transcription of the interview data to a Word 2018 document was completed by a registered and secure transcription service contracted with the academic institution. A research assistant reviewed the transcriptions and made corrections prior to the investigators’ verification of accuracy in preparation for data analysis.

Data analysis

During the quantitative data analysis, qualitative coding, and mixed methods synthesis, the study aim was addressed by specifically examining and exploring (1) What are the community stakeholders’ perceptions toward memory screening? (2) Did attitudes impact stakeholder willingness to be screened?

Quantitative analysis

Results of the sociodemographic data, PRISM-PC measures, and interview transcripts were examined using descriptive statistics and Pearson’s r correlations. The research team reviewed, cleaned, and conducted random checking of the data during their first analysis meeting.

Qualitative analysis

Prior to examining the qualitative data, the researchers discussed as a group, then individually pursued, bracketing of any personal interests and experiences that could lead to a biased interpretation of the qualitative interview data Sorsa, Kiikkala, & Åstedt-Kurki, 2015). To further minimize the threat of bias and “capture the essence of stakeholders’ intended meanings,” transcripts of the recorded interviews were analyzed using Saldaña’s in vivo process (Saldaña, 2015). The in vivo method of coding is defined as using the participant’s own key word or phrase to create acoding category. This process allows the researcher to be more attuned to the stakeholder’s perspectives and language and diminishes the threat of choosing themes built on words or phrases generated by the investigator (p. 71).

Each team member independently reviewed the transcripts twice and looked for consistency and variations in patterns of the data (Tappen, 2015). Before meeting to discuss their findings, the investigators identified general codes based on participant statements, grouped participant responses to the most relevant code, and selected one in vivo statement that would best characterize responses under each code (Saldaña, 2015). The researchers also recorded their reflections, known as memoing, during the process of reading and coding the transcripts. Memoing is a technique used in qualitative research to seek additional answers, stimulate further questions, and identify topics for future investigation (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). These notes were included in the preliminary data analysis. The researchers met twice more to conduct further analysis for reaching consensus on which in vivo statements best characterized the overall participant responses, and to conduct the parallel mixed methods synthesis (Chiang-Hanisko, Newman, Dyess, Piyakong, & Liehr, 2016) of the quantitative and qualitative findings.

Parallel mixed methods analysis

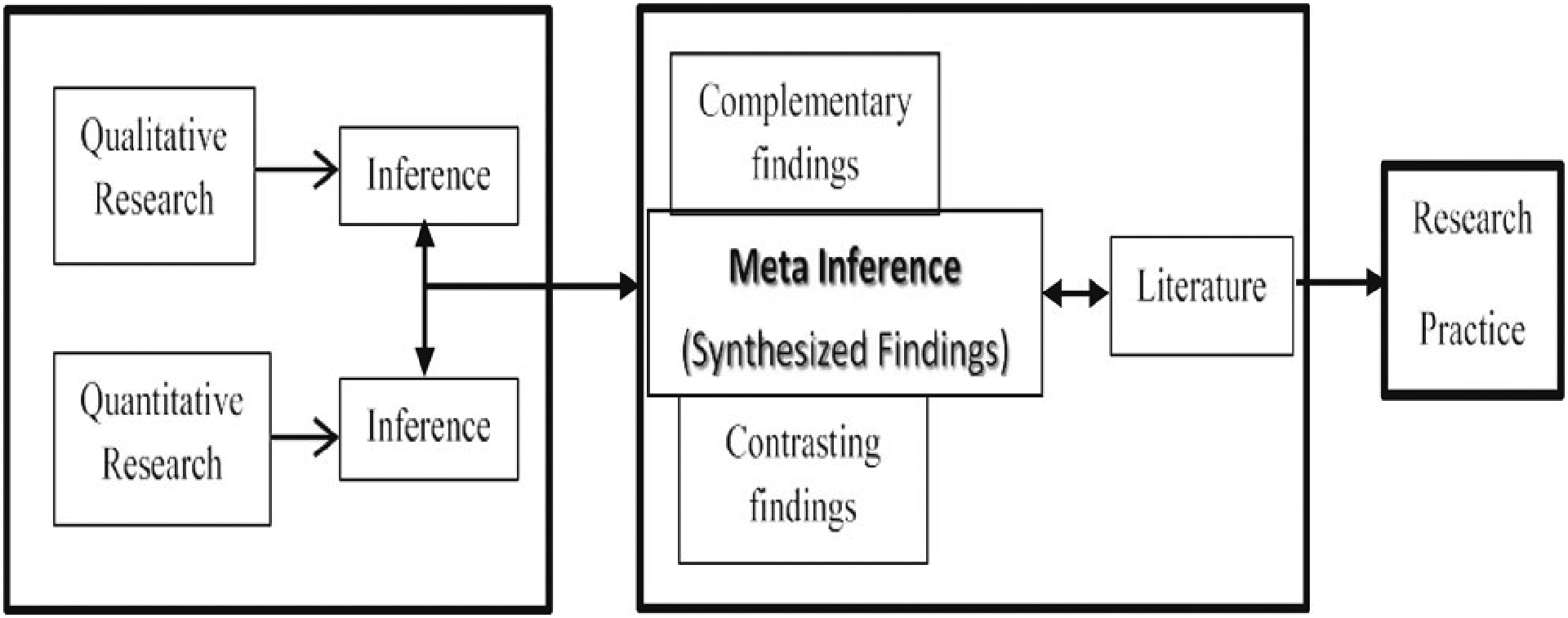

The parallel mixed (PMM) technique by Tashakkori and Newman (2010) was chosen because it calls for methods transparency in establishing trustworthiness, provides opportunities for self-correction, and offers deeper insight into the phenomena under investigation, all which increase the likelihood of reproducibility (Chiang-Hanisko et al., 2016). To answer our research questions using this type of method, the data gathering, analysis, and inferences of the qualitative and quantitative findings transpired concurrently (Tashakkori & Newman, 2010). The final step was examining the inferences at the point where the findings intersect to answer the question of how/where to combine the results. Chiang-Hanisko et al. (2016) provide a visual (Figure 1) and explain that it is important to synthesize the results gathered from the PMM at the interface of both the quantitative and qualitative data. The PMM approach offers the opportunity to capture a more holistic and complete perspective than what would be gleaned from only one outlook.

Figure 1.

Parallel Mixed Methods (Chiang-Hanisko, Newman, Dyess, Piyakong, and Liehr, 2016).

The analyses centered on exploring the potential for contrasting or complementary patterns (Chiang-Hanisko et al., 2016). To do this, answers to the interview questions and survey items that addressed the same concept were analyzed for patterns of consistency and variation. The similarities and differences were identified. For items and interview questions that did not address the same issue, a summary of differences was created. The findings were then merged (the interpretive interface) to reach a greater depth of understanding in addressing the study aim of examining a cohort of Appalachian stakeholder attitudes toward routine memory screening.

Results

The key findings from the quantitative surveys and semi-structured qualitative interview questions offered to 22 Appalachian key stakeholders not previously diagnosed with AD are presented. The planned sample size was 20 participants based on the previous study8 and recruitment continued until investigators believed that no new information was emerging. The sociodemographic findings of the largely White (n = 21) and one African American participant are available in Table 1. The majority were female (73%), saw a provider (95%) and had experience as a caregiver of someone with dementia (82%). The average age was 64 (SD = 12.1) and mean health literacy was high at 6 (SD = 2.4). There were no significant differences between older or younger persons or education levels and attitudes toward memory screening.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics; Categorical and Continuous Variables

| n = 22 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | f | % |

| Total Sample | ||

| Male | 6 | 27 |

| Female | 16 | 73 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 21 | 95 |

| African American | 1 | 5 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 15 | 68 |

| Widowed | 5 | 23 |

| Divorced/Separated | 2 | 9 |

| See a Provider | ||

| Yes | 21 | 95 |

| No | 1 | 5 |

| Willing to be Screened Caregiver | 22 | 100 |

| Yes | 18 | 82 |

| No | 4 | 8 |

| M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 64 | 2.1 | 43 | 86 |

| Education | 15 | .2 | 6 | 24 |

| REALM-SV | 6 | 2.4 | 0 | 7 |

Notes: Descriptive variables are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Mean, standard deviation, and range for continuous variables are presented.

Rapid Estimate of Literacy in Medicine, short form (REALM-SF) by Arozullah, et al., (2017).

PRISM-PC survey items addressing memory screening

Included in the PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) survey was the item related to one’s willingness to participate in memory screening. All the participants answered “yes” (n = 22) to the survey item “Would you be willing to participate in a brief check of your memory?” Most participants also answered positively on the 22 items included in the PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) items investigating willingness to screen (see Table 2). For example, 82% persons were agreeable to blood testing or “pictures of head or brain” (86%) to detect dementia. All participants indicated that they would want their provider to screen them annually for memory problems and that they would want to know if they had memory problems. Importantly, 100% believed that early detection offered a better chance for treatment, that they would have time to talk with their family, and make plans for future care. Over 80% believed the family would suffer financially, but not emotionally, and did not want to burden their family with care. Most (77%) did not believe they would lose their insurance if they were told of an AD diagnosis.

Table 2.

Responses to Selected Items of PRISM-PC Survey (Boustani, et al., 2008)

| # of no/yes responses / % total responses | ||

|---|---|---|

| Item | No/% | Yes/% |

| I would like to know if I am at higher risk than others for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | 2/9 | 20/91 |

| I would like to know if I have AD | 1/5 | 21/95 |

| I would like to know if I have a problem with memory | — | 22/100 |

| I would like a doctor to examine me every year to know if I have developed memory problems | — | 22/100 |

| I do not believe treatment for AD is currently available | 16/72 | 6/28 |

| Early detection of AD increases the chance to treat the disease better | — | 22/100 |

| If knew earlier that I have AD, my family would have a better chance to take care of me | 4/18 | 18/82 |

| If I found out early that I have AD, I would have more time to plan for the future | — | 22/100 |

| If I found out early that I have AD, I would have more time to talk with family about my health care | — | 22/100 |

| If I found out early that I have AD, I would sign my advance directive | 10/45 | 12/55 |

| If I knew earlier that I have AD, I would be motivated to have a healthier lifestyle | 18/82 | 4/18 |

| If I knew earlier that I have AD, I would be more willing to participate in research about this disease | 4/18 | 18/82 |

| If I knew that I have AD, my family would suffer financially | 4/18 | 18/82 |

| If I knew earlier that I have AD, my family would suffer emotionally | 16/72 | 6/28 |

| If I have AD, I would not want my family to know | 16/72 | 6/28 |

| If I knew I have AD, I would feel humiliated by family members and others. | 20/91 | 2/9 |

| If knew I have AD, would be ashamed or embarrassed | 12/55 | 10/45 |

| If knew I have AD, I would be depressed | 7/32 | 15/68 |

| If knew I have AD, I would give up on life | 15/68 | 7/32 |

| If I am diagnosed with AD, I would be living in a nursing home | 14/64 | 8/36 |

| If I was diagnosed with AD, my doctor would not provide the best care for my medical condition | 11/50 | 11/50 |

| I would like to be tested for AD with pictures of my head or brain. | 3/14 | 19/86 |

| I would like to be tested for AD with a blood sample. If I am diagnosed with AD, I would not be able to get health insurance | 4/18 5/23 | 18/82 17/77 |

Notes: There were 22 respondents in the sample. Table 2 displays the number of participants who answered “No” or “Yes” to each item and the percent of the total number of responses.

Perceptions Regarding Investigational Screening for Memory in Primary Care (PRISM-PC) Scale (Boustani, et al., 2008).

Although stakeholders wanted to be informed, 68% indicated that they would also be depressed if they were to learn of an AD diagnosis. Only 50% believed that they would receive the best care from their medical doctor for their condition. Of note is that only 18% indicated that they would change their own lifestyle if they became aware they had AD.

In vivo coding

When meeting together to share their analyses, the researchers realized that several statements could have been categorized as belonging to more than one code. In addition, one reviewer chose “Knowledge” rather than “Awareness” as an in vivo code. To resolve these minor differences the investigators met again, referred to their memoing notes, shared their thought processes using diagrams on white boards, discussed the meanings and inferences of the stakeholder responses, and reached consensus regarding which in vivo statements were most representative of participant input (see Table 3). The resulting in vivo themes and examples of supporting statements are listed below.

Table 3.

In Vivo Themes with Participant Statements regarding Willingness to Screen

| Code/In Vivo Theme | Participant Statement |

|---|---|

| Burden I don’t want to burden my family |

|

| Fear/I’m afraid that I’ll get it later in life |

|

| Awareness/Know what you have so you can best deal with it |

|

| Help/Getting them to the right doctor would be a problem |

|

| Fatalism/By the time they get help it’s too late |

|

Note: The italicized participant phrases indicate the selected in vivo codes

Knowing what you have so you can best deal with it was a theme based on participant comments such as “maybe if we had known what was coming we might have been better prepared for it” and “the more you know about someone’s health, the more you are able to help them.”

I don’t want to burden my family was another theme, and supported in additional statements such as “I’ve already told my family that if I am diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, find a nursing home”, and “They are sick themselves just trying to deal with … take care of … their family person with it”.

By the time they get help, it’s too late was revealed by statements such as “Whaddya gonna do about it?” and “who is goin to help em?”

Getting them to the right doctor would be a problem, further evidenced by concerns expressed such as “they can’t get help. They can’t get to help.”

I’m afraid that I’ll get it later in life was a fear often heard throughout the interviews: I have a fear that …. “I’ll get it before they figure out a way to stop it”, … “not having a brain that works.”

Parallel mixed methods findings

Results from the PRISM-PC (Boustani et al., 2008) items were examined for quantitative inferences, using 51% or greater as the majority benchmark of participant responses. These descriptive results were compared and contrasted with the qualitative thematic inferences using a parallel mixed methods approach (Chiang-Hanisko et al., 2016, Figure 1), which resulted in two meta-inferences (Table 4).

Table 4.

Results of Parallel Mixed Methods Analysis

| Analysis | Synthesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Inferences (In Vivo Codes) | Quantitative Inferences (PRISM-PC Results) | Meta-Inference | Practice Implication |

| I’m afraid that I’ll get it later in life | 91% want to know if higher AD risk/would want an annual check-up 95% would want to know if they had AD | There is large support for early screening, despite concerns about emotional burdens | Increase access to annual memory screening Inform providers regarding AWV annual memory screening and benefits to screening |

| I Don’t Want To Burden My Family | 82% thought family would suffer financially 28 % thought family would suffer emotionally/would not want them to know 36% thought they would be in a nursing home after AD diagnosis | ||

| Know What You Have So You Can Best Deal With It | 91% want to know if higher AD risk 95% would want to know if they had AD 100% would want to know if they had memory problems/would want an annual memory check | ||

| By The Time They Get Help It’s Too Late | 32% would give up on life 82% would not be motivated to have a healthier lifestyle after earlier diagnosis 100% thought earlier diagnosis would allow earlier care planning | Despite the strong belief that earlier diagnosis allows for earlier care planning, many doubt that effective health coverage or care is available, and will not seek to alter lifestyle. | Educate residents regarding insurance benefits Increase provider engagement in AD detection Is the reluctance to change behaviors a type of fatalism? More research is needed. |

| Getting Them To The Right Doctor Would Be A Problem | 77% thought they would lose health insurance 50% thought doctor would not provide the best care for medical condition | ||

Discerning the meta-inferences

The two meta-inferences were agreed upon by the researchers after pairing the results of the PRISM-PC items that addressed similar concerns as the in vivo codes. For example, in the PRISM-PC findings, although 82% thought family would suffer financially, only 28% thought family would suffer emotionally or would not want them to know. Awareness was important; over 90% wanted to know if they were at higher AD risk or had AD, and 100% wanted to know if they had memory problems and would want an annual memory check. In the qualitative interviews, the in vivo themes were “I’m afraid that I’ll get it later in life”, “I don’t want to burden my family”, and “know what you have so you can best deal with it.” Yet 100% wanted an annual memory check and to know if they had trouble with their memory. Therefore, combining these findings led to the meta-inference that there is large support for early screening, despite concerns about emotional burdens.

The second meta-inference was induced after inspecting the results that despite 100% agreeing with the statement that an earlier diagnosis would allow earlier care planning, 82% would not be motivated to have a healthier lifestyle, 77% thought they would lose health insurance, and 50% thought the doctor would not provide the best care for medical condition. A third indicated that they would give up on life upon hearing of a dementia diagnosis. The in vivo themes were “by the time they get help it’s too late” and “getting them to the right doctor would be a problem.” Therefore, the meta-inference was Despite the strong belief that earlier diagnosis allows for earlier care planning, many doubt that effective health coverage or care is available, and will not seek to alter lifestyle.

Discussion

The results of applying the parallel mixed methods (Chiang-Hanisko et al., 2016) revealed that although an Appalachian stakeholder group perceived the importance of AD detection in planning, they expressed doubt that the needed support was available. Nor did this cohort, derived from a culture that is typically viewed as being independent and self-sustaining (Goins, Spencer, & Williams, 2011) want to make changes in their current pattern of living, even though they wished to know if they were at risk for or had dementia.

Perceptions about cognitive screening in other rural cohorts

The investigators next considered whether this and other findings might be similar to previous studies of rural residents’ perceptions about dementia detection. Only one study conducted within the last five years was located specifically targeting rural resident perceptions about dementia or memory screening, which was a companion study to this current work reported previously in this journal (Wiese, Williams, & Galvin, 2018a). Although exact comparisons cannot be made, the same data-gathering measures, the Sociocultural Health Belief Model theoretical framework (Sayegh & Knight, 2013), qualitative in vivo coding, checks for trustworthiness (such as member-checking), and quantitative data analysis were used in both studies. Parallel mixed methods inspection was used only in this Appalachian cohort study.

Each cohort had unique characteristics. This WV group was 95% White, with an average education level of 15 (SD=2.0), whereas 76% of the Florida (FL) largely retired migrant worker cohort was ethnically diverse, with an average age of 58.2 (SD=15.4). In the Appalachian cohort, no significant differences or correlations were found between willingness to screen and the sociodemographic factors of age, ethnicity, race, marital status, education, health literacy, years lived rural, or caregiving experience. Likewise, in the FL cohort, no significant relationships were found between the sociodemographic variables and willingness to screen. However, in the FL cohort (Wiese, Williams, & Galvin, 2018a), negative correlations (p = .01) were found between years living rurally and health literacy (r = .83), and health literacy and age (r = −.67). Stakeholders in each cohort included healthcare administrators and providers, ministers, retirees, and informal caregivers, but only this WV cohort had law enforcement or emergency responders.

Qualitative themes between two rural cohorts

Perceptions are likely to be influenced not only by culture (Goins et al., 2011) but by locality and availability of resources. In comparing these results, we found three similar themes between the two studies. The first was evidence of a strong desire to be informed of knowing of the presence of dementia, as seen in the in vivo codes “gives families a chance” in the FL group and “knowing what you have so you can best deal with it” in the Appalachia group. Secondly, both groups highlighted concerns about adequate memory care through statements about limited resources and lack of attention to dementia illness by providers. Third, both groups were expressive about the fatality of the illness, as seen in the codes “a sentence being pronounced over their lives” (the FL group) and “fear of getting it later in life” (Appalachian group). In contrast, the Appalachian group rarely mentioned issues identified in the FL cohort codes of “trust is everything here” and “keep everybody at home” (see Table 4). The two rural groups did share the overall theme of being aware and informed so that one could plan and prepare. A striking difference was that the majority of the ethnically diverse FL group indicated that they would be motivated to have a healthier lifestyle if they knew earlier that they had AD. This contrast between the two rural groups highlights the importance of assessing communities’ unique perspectives prior to planning educational and behavioral interventions related to dementia prevention.

Limitations and strengths

Limitations of this study included the lack of diversity or participant randomization, and potential historical influence on results due to the intense television and newspaper media campaign regarding signs and symptoms of AD occurring simultaneously in WV. Other limitations included the threat of selection bias, as stakeholders were recommended by gatekeepers. The variety of disciplines, ages, education, and experiences represented likely helped in minimizing this threat. Although outside the scope of this study, examining cultural influences would provide valuable insight to this work. Strengths included the familiarity of the PI with the population, and willingness of residents to engage in research (only one of the residents invited to participate declined, due to personal travel). Another strength of the study was the use of parallel mixed method of discovery. This method, “when applied with thoughtful interpretation at the intersection of qualitative and quantitative data, has the potential to capture a complete perspective” (Chiang-Hanisko et al., 2016, p. 3).

Implications for education

There is a timely need to decrease the health care disparity of delayed ADRD detection in underserved rural settings. Based on the findings as reported in meta-inference #2 (see above), willingness to know did not lead to willingness to act. However, with education about lifestyle choices that may delay onset or disease progression, and awareness that providers can follow through on measures to support persons with dementia, individuals’ willingness to act could increase. Inspiring such health-seeking behaviors begins with increasing knowledge to change misconceptions. Schoenberg, Howell, and Fields (2012) and Schoenberg et al. (2009, 2016) demonstrated the effectiveness of applying Schoenberg’s “Faith Moves Mountains” model of health education for significantly increasing rates of breast, cervical, and colon cancer screenings in rural Appalachian Kentucky. Community agencies may be of help in discovering innovative educational approaches to counteracting reluctance to change behaviors when designing interventions for rural residents.

Nursing and medical students and community groups can partner together with providers to offer brief, culturally effective education seminars regarding ADRD in older adult settings. Offering cognitive screenings and referrals to primary care providers immediately after awareness seminars can help to increase rates of dementia detection. Training lay health educators to conduct annual screenings in independent living facilities, community centers, faith-based settings, and gated communities can assist with increasing awareness.

It is important to assess each community’s perspectives and knowledge gaps, as shown by the comparison between this Appalachian and the FL cohort. A community-based participatory approach using open-ended surveys and/or the PRISM-PC instrument, and the Basic Knowledge of Alzheimer’s Disease (BKAD; Wiese, Williams, Tappen, & Newman, 2019a) measure used recently in rural settings can be helpful. These approaches have been well received by community members during practice projects recently completed summer 2019 in the authors’ home state in both rural and urban Haitian Creole communities (Wiese, Williams, Hain, & Galvin, 2019b; Daccarett and Wiese, 2019).

Numerous pre-made educational outlines, hand-outs, and PowerPoints for offering disease awareness do not have to be created; they are available for free download by a simple google search of “Alzheimer’s disease education” from sites such as the Alzheimer’s Association Training and Education Center, and many are available in Spanish. These resources can be adapted to the appropriate health literacy level.

A different concern is that 50% of the participants in this study were doubtful that provider care or assistance would be adequate for this terminal illness. Compounding the issue of fatalism among the participants is the perception by providers that detecting and treating AD require too much time, and may not yield benefit (Ahmad, Orrell, Iliffe, & Gracie, 2010). Providers may not be aware that the Alzheimer’s Association and National Institute on Aging (NIA) have partnered to provide multiple training modules, including those directed specifically toward rural providers. Included in these resources are findings from a federally-funded task force that cite brief screening measures as effective methods for memory screening (Cordell et al., 2013), such as the Mini-Cog™ (Borson, Scanlan, Chen, and Ganguli (2003) and Borson et al., 2013), or informant interview, such as the Quick Dementia Rating Scale (Galvin, 2015; Berman et al., 2017).

In addition to screening tools and education modules, the NIA (2020) offers user-friendly algorithms to follow. Increasing awareness of these resources among rural providers could aid in increasing active dementia management. We suggest sharing this resource with rural clinics, health facilities, and medical associations as a first step in addressing the second meta-inference: Despite the strong belief that earlier diagnosis allows for earlier care planning, many doubt that effective health coverage or care is available, and will not seek to alter lifestyle. In addition, an area needing improvement is promoting earlier and home-based care of persons with AD. One concrete means of achieving this would be to revise the current coverage for home care offered by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2018) which limits coverage to acute care needs only. Insurance policy changes are needed that would support extended care in the home for persons with AD.

Implications for practice

The inferences (Table 4) resulting from the parallel mixed methods analysis resulted in practice implications, which were 1) increase access to annual memory screening, 2) inform providers regarding the Annual Wellness Visit annual memory screening and benefits to screening, 3) educate residents regarding insurance benefits, 4) and increase provider engagement in AD detection.

Although the results discussed here are not generalizable to all rural communities, hopefully these findings will encourage rural providers to think further about committing to early detection. Future actions to increase cognitive screening in rural settings can be built on the example of this work, which revealed that participants’ beliefs of being aware of a dementia diagnosis is important in order to plan for the future.

Implications for research

The RHP2020 initiative demonstrated that rural health disparities are closely related to geography and resulting lack of healthcare access (Bolin et al., 2015). Despite findings from this study and its partner study in rural FL illustrating two diverse cohorts of rural residents’ interest in health-seeking behaviors of dementia screening and detection, care access and provider interest were also noted as barriers. An alternative is home-based care by gerontological nurse practitioners in collaboration with primary care providers. An early study from the 1990’s demonstrated significant (p = .02) increases in length of home stays (Stuck et al., 1995) at a cost savings of $6,000 per geriatric patient seen by nurse practitioners partnering with physicians. Using the inflation calculator index of 68.4% inflation, this would translate to a 2019 savings of $10,101 (Clinicaltrials.gov, 2019). More recently, the “Maximizing Independence at Home” or MIND study showed effectiveness in delaying transition to institutionalized care and improving self-reported quality of life (Samus et al., 2014). A home-based approach was successful in recent pilot work of dementia detection and treatment in rural subsidized housing (Wiese, Williams, Hain, & Galvin, 2019b). Additional research is needed to validate the updated cost benefits of rural aging in place through home-based care approaches. The goal is to garner substantial insurance coverage for short and long term home care coverage, particularly in light of the numerous rural hospital and other health service closures (Bolin et al., 2015). In addition, more research is needed to explore the factors related to reluctance to change behaviors such as fatalism.

Conclusion

In conclusion, although the findings demonstrated widespread support for memory screening, participants were concerned about the lack of follow-through following a diagnosis. Similarly, other researchers recently found that offering screenings is not enough to decrease costly healthcare utilization (Rosenbloom et al., 2018). Rural providers, educators, and practitioners can help diminish AD-related burdens by discerning community-based perceptions and needs regarding AD detection, and partnering with local stakeholders in designing effective linkages to AD-related services built on the community’s own strengths.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abner EL, Jicha GA, Christian WJ, & Schreurs BG (2016). Ruralurban differences in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders diagnostic prevalence in Kentucky and West Virginia. The Journal of Rural Health, 32(3), 314–320. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler G, Lawrence BM, Ounpraseuth ST, & Asghar-Ali AA (2015). A Survey on Dementia Training Needs Among Staff at Community-Based Outpatient Clinics. Educational Gerontology, 41(12), 903–915. doi: 10.1080/03601277.2015.1071549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S, Orrell M, Iliffe S, & Gracie A (2010). GPs’ attitudes, awareness, and practice regarding early diagnosis of dementia. British Journal of General Practice, 60(578), e360–e365. doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X515386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriof J, Waddock S, Husted B, & Rahman SS (2017). Unfolding stakeholder thinking: Theory, responsibility and engagement. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Appalachian Region Commission (ARC). (2017). Health Disparities in Appalachia. Retrieved from https://www.arc.gov/images/appregion/fact_sheets/HealthDisparities2017/WVHealthDisparitiesKeyFindings817.pdf.

- Arozullah AM, Yarnold PR, Bennett CL, Soltysik RC, Wolf MS, Ferreira RM, … Davis T (2007). Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Medical Care Journal, 45 (11), 1026–1033. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180616c1b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth J, Nickel F, & Kolominsky-Rabas PL (2018). Diagnosis of cognitive decline and dementia in rural areas—A scoping review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(3), 459–474. doi: 10.1002/gps.4841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman SE, Koscik RL, Clark LR, Mueller KD, Bluder L, Galvin JE, & Johnson SC (2017). Use of the Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS) as an initial screening measure in a longitudinal cohort at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease Reports, 1(1), 9–13. doi: 10.3233/ADR-170004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin JN, Bellamy GR, Ferdinand AO, Vuong AM, Kash BA, Schulze A, & Helduser JW (2015). Rural Healthy People 2020: New decade, same challenges. The Journal of Rural Health, 31(3), 326–333. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Frank L, Bayley PJ, Boustani M, Dean M, Lin PJ, … Stefanacci RG (2013). Improving dementia care: The role of screening and detection of cognitive impairment. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(2), 151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, & Ganguli M (2003). The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(10), 1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boustani M, Perkins AJ, Monahan P, Fox C, Watson L, Hopkins J, … Hendrie HC (2008). Measuring primary care patients’ attitudes about dementia screening. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(8), 812–820. doi: 10.1002/gps.1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang-Hanisko L, Newman D, Dyess S, Piyakong D, & Liehr P (2016). Guidance for using mixed methods design in nursing practice research. Applied Nursing Research, 31, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2018). Medicare Geographic Distribution. Retrieved from: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Geographic-Variation/GV_PUF.html.

- Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, Chodosh J, Reuben D, Verghese J, … & Medicare Detection of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup. (2013). Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(2), 141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Creswell JD (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daccarett S & Wiese LK (2019). Increasing Cognitive Screening, Neuropsychological Referrals, and Dementia Detection Among Older Haitian Adults. Poster Presentation, April 9, Southern Gerontological Society 40th annual conference, Destin Beach, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, Rossi A, & Dell’Agnello G (2015). Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: A literature review on benefits and challenges. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 49(3), 617–631. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RE (1994). The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Business Ethics Quarterly, 4(4), 409–421. doi: 10.2307/3857340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler NR, Perkins AJ, Turchan HA, Frame A, Monahan P, Gao S, & Boustani MA (2015). Older primary care patients’ attitudes and willingness to screen for dementia. Journal of Aging Research, 2015, 1–7. doi:10.1155/2015/42326 doi: 10.1155/2015/423265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisoni GB, Boccardi M, Barkhof F, Blennow K, Cappa S, Chiotis K, … Winblad B (2017). Strategic roadmap for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease based on biomarkers. The Lancet Neurology, 16(8), 661–676. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30159-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J, James B, Johnson T, Marin A, & Weuve J (2019). The 2019 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers & Dementia, 115(3), 321–387. Retrieved from: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE (2015). The Quick Dementia Rating System (QDRS): A rapid dementia staging tool. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment & Disease Monitoring, 1(2), 249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin JE, & Goodyear M (2017). Brief informant interviews to screen for dementia: The AD8 and quick dementia rating system. In Cognitive Screening Instruments (pp. 297–312). Illinois: Spring Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Spencer SM, & Williams K (2011). Lay Meanings of Health Among Rural Older in Appalachia. The Journal of Rural Health, 27(1), 13–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2010.00315.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrawood A, Fowler NR, Perkins AJ, LaMantia MA, & Boustani A (2018). Acceptability and results of screening among older adults in the United States. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 15(1), 51–55. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666170908100905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Kelly S, Khan A, Cullum S, Dening T, Rait G, … Lafortune L (2015). Attitudes and preferences towards screening for dementia: A systematic review of the literature. Biomed Central (BMC)Geriatrics, 15(1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattos MK, Snitz BE, Lingler JH, Burke LE, Novosel LM, & Sereika SM (2017). Older rural-and urban-dwelling Appalachian adults with mild cognitive impairment. The Journal of Rural Health, 33(2), 208–216. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meit M, Knudson A, Gilbert T, Yu ATC, Tanenbaum E, Ormson E, & Popat MS (2014). The 2014 update of the rural-urban chartbook. Rural Health Reform Policy Research Center. Retrieved from: https://ruralhealth.und.edu/projects/health-reform-policy-researchcenter/pdf/2014-rural-urban-chartbook-update.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D, Kosteniuk J, Seitz D, O’Connell ME, Kirk A, Stewart J, … Kennett-Russill D (2019). A five-step approach for developing and implementing a Rural Primary Health Care Model for Dementia: A community–academic partnership. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 20, 1–11. doi: 10.1017/S1463423618000968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2020). National Institute of Aging’s Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resources for Professionals. Retrieved from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-dementia-resourcesfor-professionals.

- Rikard RV, Thompson MS, McKinney J, & Beauchamp A (2016). Examining health literacy disparities in the United States: A third look at the National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL). BMC Public Health, 16(1), 975. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3621-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom M, Barclay TR, Borson S, Werner AM, Erickson LO, Crow JM, … Hanson LR (2018). Screening Positive for Cognitive Impairment: Impact on Healthcare Utilization and Provider Action in Primary and Specialty Care Practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 33(10), 1746–1751. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4606-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña J (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Samus QM, Johnston D, Black BS, Hess E, Lyman C, Vavilikolanu A, … Lyketsos CG (2014). A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: The maximizing independence at home (MIND) pilot randomized trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(4), 398–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.12.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, … Jinks C (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh P, & Knight BG (2013). Cross-cultural differences in dementia: The Sociocultural Health Belief Model. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(4), 517–530. doi: 10.1017/S104161021200213X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Eddens K, Jonas A, Snell-Rood C, Studts CR, Broder-Oldach B, & Katz ML (2016). Colorectal cancer prevention: Perspectives of key players from social networks in a low-income rural US region. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 30396–30313. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.30396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Hatcher J, Dignan MB, Shelton B, Wright S, & Dollarhide KF (2009). Faith Moves Mountains: An Appalachian cervical cancer prevention program. American Journal of Health Behavior, 33(6), 627–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberg NE, Howell BM, & Fields N (2012). Community strategies to address cancer disparities in Appalachian Kentucky. Family & Community Health, 35(1), 31. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3182385d2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorsa MA, Kiikkala I, & Åstedt-Kurki P (2015). Bracketing as a skill in conducting unstructured qualitative interviews. Nurse Researcher, 22(4), 8–12. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.4.8.e1317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuck AE, Aronow HU, Steiner A, Alessi CA, Büla CJ, Gold MN, … Beck JC (1995). A trial of annual in-home comprehensive geriatric assessments for elderly people living in the community. New England Journal of Medicine, 333(18), 1184–1189. Doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511023331805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappen RM (2015). Advanced nursing research: From theory to practice. Sudbury: Jones & Bartlett Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2018). State and county QuickFacts. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/gladescountyflorida, US/PST045218.

- Wiese LK, Williams CL, Tappen R, Newman D, & Rosselli M (2017). Assessment of Basic Knowledge About Alzheimer’s Disease Among Older Rural Residents: A Pilot Test of a New Measure. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 25(3), 519–548. doi: 10.1891/1061-3749.25.3.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese L, Galvin JE, & Williams CL (2018a). Rural stakeholder perceptions about cognitive screening. Aging & Mental Health, 23(12), 1–13. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1525607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese LK, & Williams CL (2018b). An Appalachian perspective of Alzheimer’s disease: A rural health nurse opportunity. Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care, 18(1), 180–209. doi:10.14574/ojrnhc.v17i1 doi: 10.14574/ojrnhc.v17i1.469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese LK, Williams CL, Tappen RM, & Newman D (2019a). An updated measure for investigating basic knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease in underserved rural settings. Aging & Mental Health, March 14, 1–8. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1584880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese LK, Williams CL, Hain D, Galvin J, & Newman D (2019). Detecting Dementia in Older, Ethnically Diverse Residents in Rural Subsidized Housing. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 15(7): P1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese LK, Williams CL, & Tappen RM (2014). Analysis of barriers to cognitive screening in rural populations in the United States. Advances in Nursing Science, 37(4), 327–339. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]