To the Editor:

During the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic it has become clear that patients with comorbidities are not only at higher risk of contracting the disease but also to develop serious complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). A dose-dependent correlation between alcohol consumption and viral infections is well documented (1) and, furthermore, alcohol consumption has been shown to increase the risk of acquiring community infections (2).

A general increase in the consumption of alcohol has been reported during the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic (3). It has been hypothesized that patients with alcohol-related disorders are at an increased risk of COVID-19 (4). However, it remains unknown whether alcohol consumption is associated with a more severe course of COVID-19.

Methods

We conducted a cohort study to understand the association of alcohol use and ARDS development using data from ECHOVID-19 (The COVID-19 Echocardiography Study), a prospective multicenter cohort study of 215 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 recruited from eight hospitals in eastern Denmark (March 30 to June 1, 2020). All patients were included consecutively with the investigators blinded to the health status of patients before inclusion. Inclusion criteria for ECHOVID-19 were laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-19 infection, age ≥ 18 years, not admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) at time of inclusion (patients were not excluded if later transferred to the ICU), and being capable of signing a written informed consent. Additional exclusion criteria for this substudy was an unknown history of alcohol consumption (N = 44).

The primary outcome was ARDS (defined according to the Berlin Criteria) (5) during hospitalization. Severe ARDS, defined as ARDS with an arterial oxygen pressure/fraction of inspired oxygen ratio ≤ 100 mm Hg, was a secondary outcome. Information on alcohol consumption was obtained by a questionnaire. The exposure was defined as the continuous number of drinks of alcohol per week (12 g ethanol/drink). We used parametric and nonparametric tests to assess differences in baseline characteristics in relation to the outcome. Logistic regression models were used to test and visualize the association between alcohol consumption and the outcomes. A multivariable model was constructed to adjust for potential confounders of ARDS and severe ARDS development. The multivariable model included the variables: age, smoking status (ever-smoker vs. never-smoker), prevalent heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. All participants gave written informed consent, and the study was performed in accordance with the second Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the regional ethics board. The study is registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04377035).

Results

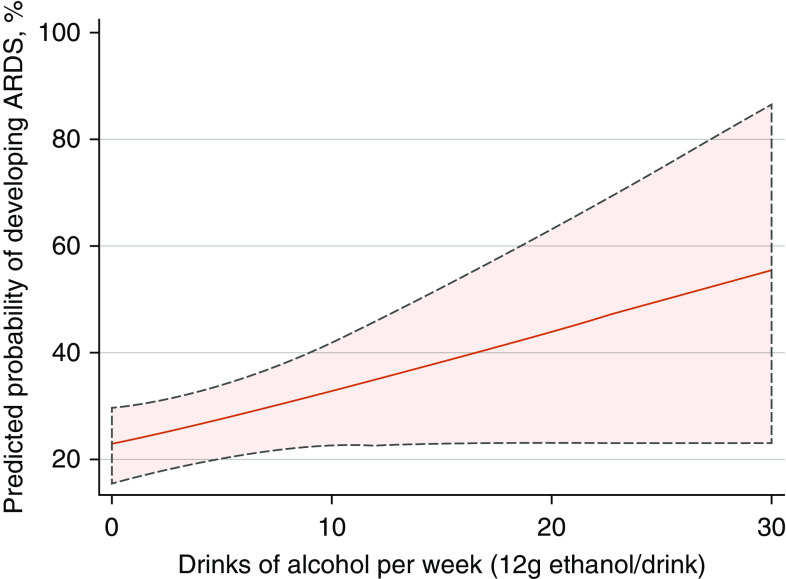

A total of 171 patients were included in the final sample. The mean age of the study sample was 69 ± 13 years and 55% were male. Baseline characteristics of patients progressing to ARDS and patients not developing ARDS are listed in Table 1. During follow-up (median, 6 d; interquartile range [IQR], 4–11) 44 patients (25.7%) developed ARDS. Of these, 22 patients (12.9%) developed severe ARDS. ARDS was not observed significantly more frequently in patients excluded from the study sample (N = 15 [34%]; P = 0.27). The comparison of self-reported alcohol consumption revealed that patients developing ARDS consumed more drinks of alcohol per week than patients free of ARDS (7.0 drinks: IQR, 5.0–20.0 vs. 3.0 drinks: IQR, 2.0–8.0; P = 0.010). In a univariable model, weekly alcohol consumption was associated with development of ARDS (odds ratio [OR], 1.06; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.01–1.12; P = 0.015, per 1-drink increase) and severe ARDS (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02–1.13; P = 0.009) (Figure 1). The association between self-reported alcohol consumption and ARDS remained significant after multivariable adjustments (ARDS: OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.00–1.10; P = 0.046, per 1 drink increase; severe ARDS: OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01–1.13; P = 0.013, per 1 drink increase).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics stratified by ARDS

| No ARDS | ARDS | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 127 | 44 | — |

| Male, n (%) | 66 (52.0) | 28 (63.6) | 0.18 |

| Age, yr (SD) | 68.1 (13.9) | 70.9 (12.0) | 0.25 |

| Alcohol intake if consumer, 12 g/wk (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–8.0) | 7.0 (5.0–20.0) | 0.010 |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 26.6 (5.4) | 27.4 (6.5) | 0.43 |

| Pack-years if smoking history, yr (IQR) | 25.0 (15.0–45.0) | 22.5 (6.5–37.5) | 0.40 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | — | — | 0.001 |

| Current | 10 (8.1) | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Former | 58 (46.8) | 34 (77.3) | — |

| Never | 56 (45.2) | 10 (22.7) | — |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 69 (54.3) | 29 (65.9) | 0.18 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 127.9 (19.8) | 121.8 (16.8) | 0.07 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg (SD) | 73.4 (11.1) | 87.2 (10.5) | 0.15 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 30 (24.0) | 10 (22.7) | 0.86 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 48 (37.8) | 22 (50.0) | 0.16 |

| Prevalent heart failure, n (%) | 12 (9.4) | 6 (13.6) | 0.44 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 21 (16.5) | 7 (15.9) | 0.92 |

Definition of abbreviations: ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; BMI = body mass index; IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 1.

The association of alcohol consumption and the probability of developing ARDS during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) hospitalization. The figure is displaying the adjusted predicted risk of developing ARDS during hospitalization for COVID-19 (with 95% confidence intervals) for the population in relation to weekly alcohol consumption. ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Discussion

In this study, weekly alcohol consumption was associated with an increased risk of developing ARDS during hospitalization for COVID-19. Higher alcohol consumption is known to be detrimental to health, but it may also be an indicator of psychosocial and socioeconomic challenges. Currently, there does not exist published literature regarding the prognosis after COVID-19 infection according to alcohol consumption. However, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Simou and colleagues conducted a review and metanalysis investigating the association between alcohol consumption and risk of ARDS in hospitalized adults (N = 177,674) (6). The authors found that chronic high alcohol consumption significantly increased the risk of ARDS. The increased risk of ARDS in excessive chronic alcohol consumption has been suggested to be caused by alcohol-induced oxidative stress leading to depletion of the critical antioxidant glutathione and ultimately deteriorates alveolar barrier integrity and modulation of the immune response (7). Kim and colleagues (8) assessed the association between risk factors and ICU admission in 2,419 adults hospitalized with COVID-19. The authors found several risk factors and underlying conditions independently associated with ICU admission. The risk factors included obesity, immunosuppression, diabetes mellitus, and age (75–84 vs. 18–39 yr) with adjusted risk ratios of 1.31, 1.29, 1.31, and 1.84, respectively. In comparison, the adjusted OR of ARDS development for every 10 weekly drinks in our study was 1.64; 95% CI, 1.01–2.68; P = 0.046. Thus, it seems that the association between weekly alcohol consumption and ARDS are within the same range as other risk factors known to be associated with a severe course of COVID-19. Naturally, there are several reservations when comparing risk ratios and odds ratios in addition to adjusted estimates of different studies.

We acknowledge that our findings are limited by the small sample size and should be further tested in larger cohorts. In addition, a limitation is that information on alcohol consumption is self-reported. Lastly, weekly alcohol consumption was missing for 20% of patients from the ECHOVID-19 study; however, we found an association of alcohol consumption with ARDS even though the included group of patients were probably less sick (less likely to develop ARDS) than the patients not able to provide information on weekly alcohol consumption. In conclusion, weekly alcohol consumption is associated with progression to ARDS during hospitalization with COVID-19. Assessing alcohol consumption habits in hospitalized COVID-19 may be useful for the identification of patients at increased risk of a poor in-hospital prognosis.

Footnotes

Supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation grant NFF20SA0062835 (T.B.-S., M.C.H.L., and K.G.S.), Europcar Denmark (M.C.H.L. and K.G.S.), funds from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, and the Lundbeck Foundation (T.B.-S.). The sponsors had no role in the design and interpretation of the data.

Clinical trial registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04377035).

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Saitz R, Ghali WA, Moskowitz MA. The impact of alcohol-related diagnoses on pneumonia outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:1446–1452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Simou E, Britton J, Leonardi-Bee J. Alcohol and the risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e022344. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Da BL, Im GY, Schiano TD. Coronavirus disease 2019 hangover: a rising tide of alcohol use disorder and alcohol-associated liver disease. Hepatology. 2020;72:1102–1108. doi: 10.1002/hep.31307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Testino G. Are patients with alcohol use disorders at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Alcohol Alcohol. 2020;55:344–346. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, et al. ARDS Definition Task Force. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simou E, Leonardi-Bee J, Britton J. The effect of alcohol consumption on the risk of ARDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2018;154:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liang Y, Yeligar SM, Brown LAS. Chronic-alcohol-abuse-induced oxidative stress in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:740308. doi: 10.1100/2012/740308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim L, Garg S, O’Halloran A, Whitaker M, Pham H, Anderson EJ, et al. Risk factors for intensive care unit admission and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized adults identified through the U.S. coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-associated hospitalization surveillance network (COVID-NET) Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1012. [online ahead of print] 16 Jul 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]