Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic has impacted adolescents’ psychosocial adjustment and social relationships across the world. This prospective longitudinal study examined whether internalizing problems during the pandemic could be predicted by precrisis friend support, and whether this effect was moderated by the time adolescents spent with their friends and COVID‐19‐related stress. 245 Dutch adolescents (M age = 11.60) participated before and during COVID‐19. Higher pre‐COVID‐19 friend support predicted less (self‐reported and parent‐reported) internalizing problems during COVID‐19, and this effect was not moderated by the time adolescents spent with friends or COVID‐19‐related stress. Friends may thus protect against developing internalizing symptoms in times of crisis. We also found the reverse effect: Internalizing problems before COVID‐19 were predictive of friend support during COVID‐19.

Keywords: internalizing problems, COVID‐19, friendship

The COVID‐19 crisis may impact social relationships and psychosocial adjustment of adolescents across the world, as they experience several drastic social changes in their daily lives due to lockdowns and may experience internalizing problems due to the uncertain nature of the COVID‐19 crisis (Liu, Bao, Huang, Shi, & Lu, 2020). As mental health issues that arise in adolescence tend to persist into adulthood (e.g., Lewinsohn, Rohde, Klein, & Seeley, 1999; Rao, Hammen, & Daley, 1999), it is important to study predictors of internalizing problems in young adolescents during the COVID‐19 crisis. Friend support may act as a buffer against various negative experiences, including times of crisis (Henrich & Shahar, 2008). Therefore, the current study examined whether precrisis friend support is negatively related to internalizing problems during the COVID‐19 crisis, and how the amount of time adolescents spend with friends and COVID‐19‐related stress affects this association.

Pre‐COVID‐19 Predictors of Internalizing Problems

There is some preliminary evidence that the prevalence of internalizing problems has increased during the COVID‐19 crisis in adults (Salari et al., 2020), but social isolation during the lockdown might be especially detrimental for adolescents, for whom close friends are an increasingly important source of support (Furman & Buhrmester, 1992). Yet, the evidence is mixed; some longitudinal studies showed increases in depression or anxiety during the COVID‐19 crisis in adolescents (Cohen et al., 2021; Kwong et al., 2020), whereas others found no difference (Achterberg, Dobbelaar, Boer, & Eveline, 2021; Janssen et al., 2020). Clearly, not all adolescents equally suffer from and develop internalizing problems during the COVID‐19 crisis, and mean‐level changes in internalizing symptoms due to COVID‐19 have to be understood in the context of normative developmental changes. Therefore, understanding individual differences in relative change in internalizing problems is important.

Individual differences in adolescent internalizing problems during the COVID‐19 crisis may be explained by several factors. Specifically, adolescents experienced isolation from their friends among the most distressing things about the lockdown (Branquinho, Kelly, Arevalo, Santos, & Gaspar de Matos, 2020). As friendships are an important source of wellbeing for adolescents (van der Horst & Coffe, 2012), having good‐quality friendships may protect against developing symptoms of depression, for example, by reducing loneliness (Nangle, Erdley, Newman, Mason, & Carpenter, 2003). The buffer theory of social support (Alloway & Bebbington, 1987) suggests that social support impacts the way major life events affect mental or physical health. Friends can be a source of support that protects against negative life events over and above parental support (Cornwell, 2003), and friend support may especially be an important buffer during the COVID‐19 crisis, as peer interactions have been drastically limited in this period. This theory has received considerable empirical support: One longitudinal study showed that baseline friend support buffered the effects of subsequent terrorist attacks on depression (Henrich & Shahar, 2008), and in a review, the majority of studies showed that social support could increase resilience against the negative impact of periods of political violence or large natural disasters (Aba, Knipprath, & Shahar, 2019). Therefore, it is likely that adolescents with higher‐quality friendships before the COVID‐19 crisis develop relatively fewer internalizing symptoms during the crisis.

The Role of Time Spent With Friends in Internalizing Symptoms

Besides support, the time adolescents spend with friends (either online or offline) is another important dimension of friendships (Bukowski, Hoza, & Boivin, 1994) that affects psychosocial adjustment. For example, it has been shown that spending time with friends predicts delinquency over and above friendship closeness and increases the effect of friend delinquency on adolescent delinquency (Agnew, 1991). Time spent with friends may also contribute to internalizing problems, particularly in periods such as COVID‐19 when time with friends is limited. There is mixed evidence for the main effect of spending time with friends on internalizing problems: Spending more time with peers has been linked to a decrease in social anxiety one year later, even when controlling for prior social anxiety (Nelemans et al., 2016). Yet, a cross‐sectional study found that adolescents were particularly at risk to experience depressive symptoms if they spent more time with friends during the COVID‐19 crisis (Ellis, Dumas, & Forbes, 2020), possibly because they use more emotion‐oriented coping strategies, such as co‐rumination (Starr, 2015), that have been associated with internalizing symptoms (Duan et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2021).

Importantly, the frequency of contact with friends may also moderate the effect of friend support on internalizing symptoms. Time spent with friends may strengthen the effect of precrisis friend support on the development of internalizing problems during COVID‐19. The cumulative protection hypothesis (Masten & Wright, 1998) suggests that having multiple protective factors may result in stronger resilience than the sum of individual protective factors. Adolescents who (continue to) frequently spend time with friends may benefit more from the friend support they perceived before the crisis than adolescents who do not see their supportive friends as often anymore. Therefore, friend support may have a stronger buffering effect when friends also continue to spend time together, both online and offline.

The Role of COVID‐19‐Related Stress in Internalizing Symptoms

The COVID‐19 crisis may not be experienced as equally stressful by all adolescents. As it has been repeatedly shown that (interpersonal) stress is associated with adolescent depression (Rudolph et al., 2000), COVID‐19‐related stress might also relate to differences between adolescents in internalizing symptoms during the COVID‐19 crisis. Indeed, adolescents experienced more negative and less positive feelings if they perceived COVID‐19 as a serious threat to themselves or in general (Commodari & La Rosa, 2020), and adolescents who experienced more COVID‐19‐related stress experienced more symptoms of depression (Ellis et al., 2020). It is therefore important to take into account individual differences in perceived stress during the crisis.

Importantly, COVID‐19‐related stress may also interact with friend support in predicting internalizing problems during COVID‐19, such that the effect of stress may be dampened by higher levels of friend support. Such a moderation effect was found in a study on the impact of a suicide bombing, which showed that perceived bombing‐related stress predicted depression (controlling for prebombing depression), but only when prebombing friend support was low (Shahar, Cohen, Grogan, Barile, & Henrich, 2009). In conclusion, COVID‐19‐related stress may impact internalizing problems directly or by moderating the effect of friend support.

Controlling for the Effect of Internalizing Problems on Friend Support

Although internalizing symptoms during COVID‐19 are of primary interest in the current study, it is important to also consider a potential reverse effect: Adolescents who experienced more internalizing problems before the crisis may have more difficulty maintaining supportive friendships during the crisis. Depressed and socially anxious adolescents tend to use more avoidant coping strategies, such as social withdrawal (Beidel, Turner, & Morris, 1999; Spirito & Francis, 1996), which has in turn been related to lower levels of experienced companionship and intimacy in their close friendships (Biggs, Vernberg, & Wu, 2011). During a lockdown, anxious and depressed adolescents may have been even more prone to socially withdraw from peers, because they had fewer structured opportunities to interact with others. In fact, some adolescents with a history of mental health issues (especially those who are withdrawn) reported that they had difficulty connecting to peers in times when social isolation is the norm (YoungMinds, 2020). Therefore, we also examined the effect of internalizing problems on friend support.

Current Study

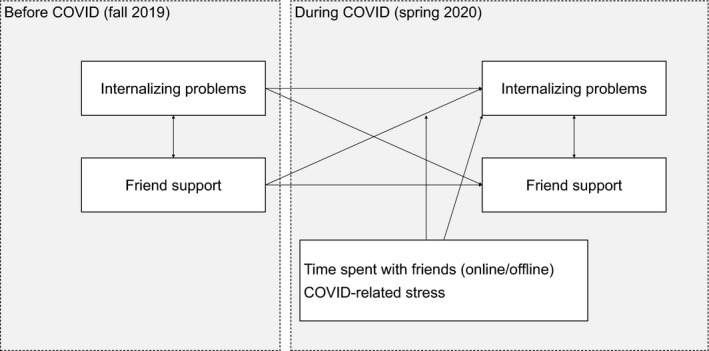

In sum, there is some evidence that adolescents experience more internalizing problems during COVID‐19, but not all adolescents may develop similar levels of internalizing problems during the crisis. Individual differences in internalizing problems during the crisis may be explained by friend support precrisis and may additionally depend on time spent with friends or COVID‐19‐related stress. We examined bidirectional longitudinal associations between friend support and internalizing problems from before to during COVID‐19 and also assessed whether the effect of friend support on internalizing problems was moderated by the time adolescents spend with friends (both online and offline) during the COVID‐19 crisis, and by COVID‐19‐related stress and worry. The proposed model for this study is displayed in Figure 1. Because both internalizing symptoms (Rudolph, 2002) and friend support (Linden‐Andersen, Markiewicz, & Doyle, 2009) are generally higher in girls, we controlled for gender in all models. We also controlled for friendship stability: The effects of pre‐COVID‐19 support by a best friend may be different when this is no longer one’s best friend during the crisis.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for the links between friend support and internalizing problems before and during the COVID‐19 crisis.

We tested the following hypotheses. First, as adolescents with higher‐quality friendships experience less loneliness and have a stronger support system that may compensate negative experiences (Henrich & Shahar, 2008; Nangle et al., 2003), we expected that adolescents who experience more friend support before the COVID‐19 crisis report less internalizing symptoms during the COVID‐19 crisis (controlling for internalizing symptoms before COVID‐19). Second, we expected that adolescents who report more internalizing symptoms before COVID‐19 report less friend support during COVID‐19 (controlling for friend support before COVID‐19; Beidel et al., 1999; Biggs et al., 2011). Third, we expected that adolescents who spend more time with their friends during the COVID‐19 crisis report less internalizing symptoms during the COVID‐19 crisis (Nelemans et al., 2016). Fourth, we expected that the negative association of friend support with internalizing problems during COVID‐19 is stronger for adolescents who spend more time with their friends (either online or offline) during the COVID‐19 crisis, because frequent contact provides them with more opportunities to seek or give support, or other social coping mechanisms. Fifth, we expected that adolescents who experience more COVID‐19‐related stress report more internalizing symptoms during the COVID‐19 crisis. Sixth, we expected that the positive association of COVID‐19‐related stress with internalizing problems is stronger for adolescents who experience lower friend support, as friend support may buffer against negative life events (Alloway & Bebbington, 1987; Henrich & Shahar, 2008). Hypotheses 1 and 3–6 were preregistered at OSF (https://osf.io/d27kv/). In addition, we aimed to replicate these results using independent reports (i.e., parents and adolescents) of adolescents’ internalizing problems. Although adolescents’ reports may give more insights into their cognitions and emotions, additionally using parents’ reports reduces the risk of overestimating effects because of negative cognitive styles associated with depressive symptoms (Garber & Rao, 2014).

Method

Participants

The sample was drawn from an ongoing longitudinal multi‐informant study on development across school transitions. Participants were recruited through 84 schools in several urban areas in the Netherlands. Adolescents were invited to participate if they were in the final year of primary school in the academic year 2019–2020. The sample consisted of 245 Dutch adolescents (Mage = 11.60, SD = .50; 50% female) and one of their parents (84.7% female in Wave 1). In most cases, the same parent reported on both occasions (94.9%). Of our 245 participants, 96.7% was of Dutch origin, and 82.2% lived in a two‐parent household. Socioeconomic status was on the high side in our sample, although there was quite some variability. Adolescents perceived their SES as higher than average (M = 7.71, SD = 1.11 on a 1–10 scale). Net family income was assessed categorically with categories “less than €1000,” “more than €9000,” and values in between with €500 increments. The median net family income was €4000–4500 (with an approximated SD of €2215).

Procedure

Online questionnaires were completed by participants and one of their parents as part of a larger data collection project that involved home visits. The first wave (T1) took place in the fall of 2019, and all questionnaires were completed before the outbreak of COVID‐19. The second wave (T2) took place approximately six months later, and all questionnaires were completed during the initial months of the COVID‐19 crisis (April–July 2020). Wave 2 took place during an intelligent lockdown, where schools in the Netherlands were closed, but adolescents were allowed to go outside (e.g., for daily exercise). On May 11, schools partially reopened, but there was great variation between schools in the extent to which adolescents received online and offline education. Both waves took place during the last year of elementary school. Participants received €10 for each completed measurement wave. All participants and one of their parents signed informed consent before participation. This procedure was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences of Utrecht University.

Measures

Internalizing problems

Adolescents reported on their own depression and anxiety using the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (47 items; Chorpita, Yim, Moffitt, Umemoto, & Francis, 2000). Participants indicated for each of 47 statements (e.g., “I worry about things”) how often it applied to them on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Internal consistency was excellent in both Wave 1 (Cronbach’s α = .93) and Wave 2 (Cronbach’s α = .95).

Additionally, adolescents’ parents reported on their child’s internalizing symptoms using the internalizing problems scale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991), which assesses anxiety, withdrawal, and somatic complaints. Parents indicated for each of 31 statements (e.g., “Is too fearful or too anxious”) to what extent it applied to their participating child on a scale from 1 (not applicable) to 3 (clearly or often applicable). Internal consistency was good in Wave 1 (Cronbach’s α = .84) and Wave 2 (Cronbach’s α = .88).

Friend support

The 7‐item support subscale of the brief version of the self‐report Network of Relationships Inventory (Furman & Buhrmester, 1985) was used to assess social support from adolescents’ friends. We additionally administered 4 items based on the Friendship Quality Scale (Bukowski et al., 1994) to assess additional aspects of friendship quality. These items were phrased to fit the format of the Network of Relationships Inventory and assessed help, intimacy, and companionship. Participants indicated for each of 11 statements (e.g., “How much do you care about your best friend?”) how often it applied to the relationship with their best friend, on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Internal consistency was good in Wave 1 (Cronbach’s α = .86) and Wave 2 (Cronbach’s α = .90).

Time spent with friends

The time participants spent with friends (during the COVID‐19 crisis) was assessed using three self‐report questions based on Osgood and Anderson’s assessment of unstructured socializing with peers (Osgood & Anderson, 2004): “How much time do you spend with friends outside of school? (This includes face‐to‐face contact, not online!)”, “How much time do you spend with friends online?”, and “How much time do you spend just ‘hanging’ with friends outside of school, without any adults present?” Response categories ranged from 1 (never) to 6 ([almost] every day, more than a few hours a day). Internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s α = .66).

COVID‐19‐related stress

Four self‐report items assessing COVID‐19‐related stress were created for the current project. Participants rated to what extent they had been worried about the following four topics since the COVID‐19 outbreak on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much): (1) the chances of getting infected, (2) the chances of friends or family getting infected, (3) the effect of the COVID‐19 crisis on their physical health, and (4) the effect of the COVID‐19 crisis on their mental or emotional health. Internal consistency was good (Cronbach’s α = .78). A Confirmatory Factor Analysis provided evidence for this scale's construct validity.

Background information

In addition to the main variables of interest, we assessed adolescents’ and parents’ demographic information, including gender (1 = girl, 0 = boy), age, ethnicity, perceived SES, household composition, and, for parents, income. Friendship stability (i.e., whether an adolescent reported on the same friend in both waves; 1 = same friend, 0 = different friend) was assessed by asking participants to name the friend about whom they filled in the questionnaires and comparing these names across waves. To control for differences in educational experiences during the pandemic, adolescents reported how frequently they received online and offline education since the COVID‐19 outbreak on seven items on a scale from 1 ([almost] never) to 5 ([almost] always).

Analytic Plan

Descriptive statistics were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (IBM Corp, 2017). The hypotheses were tested using path models in a SEM framework in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017), using α = .05 (two‐tailed) for significance testing and betas to estimate effect size. Missing data were handled using FIML. Some participants were removed from the dataset because they had too much missing data on the study variables, resulting in a sample size of 236 for analyses including adolescent‐reported internalizing problems and 240 for analyses including parent‐reported internalizing problems. All continuous variables and interaction terms were standardized prior to the analysis.

To test the hypothesis that adolescents who experienced more friend support before the COVID‐19 crisis reported less internalizing symptoms during the COVID‐19 crisis (controlling for internalizing symptoms before COVID‐19), we fit a cross‐lagged panel model (Model 1). Internalizing problems (T2) were regressed on the main predictor, friend support (T1), taking into account the reverse cross‐lagged effect, within‐time associations between internalizing problems and friend support, and autoregressive paths for both internalizing problems and friend support. To explore whether the effect of friend support on internalizing symptoms was significantly stronger than the reverse effect, we constrained the cross‐lagged paths to be equal and tested whether model fit was significantly worse than fit of the unconstrained model.

Next, to test the hypotheses regarding the main and interaction effects of time spent with friends (Model 2), we added main and interaction effects of time with friends (T2) with friend support (T1) to predict internalizing problems (T2). Similarly, to test the hypotheses regarding the main and interaction effects of COVID‐19‐related stress (Model 3), we added main and interaction effects of COVID‐19‐related stress (T2) with friend support (T1) to predict internalizing problems (T2). Interaction terms were allowed to correlate with the main effects.

In all models, we controlled all predictor and outcome variables for gender and friendship stability. In addition, we carried out sensitivity analyses (Model 4–6) to inspect whether the results from Model 1–3 were similar when using parent‐reported internalizing problems. Models were only interpreted if two out of the following three fit requirements were met: CFI ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .08, SRMR ≤ .08 (Byrne, 2012).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all study variables at both timepoints are displayed in Table 1. Repeated measures ANOVAs showed a significant decrease from T1 (before COVID‐19) to T2 (during COVID‐19) in both self‐reported internalizing problems, F(1, 187) = 3.97, p = .048, and friend support, F(1, 187) = 5.88, p < .001, but not in parent‐reported adolescent internalizing problems, F(1, 187) = 0.52, p = .470.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for all Study Variables

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Int. Prob. A T1 | 1.47 (.31) | |||||||

| 2. Int. Prob. A T2 | 1.43 (.33) | .647*** | ||||||

| 3. Int. Prob. P T1 | 1.17 (.17) | .388*** | .373*** | |||||

| 4. Int. Prob. P T2 | 1.18 (.19) | .414*** | .457*** | .802*** | ||||

| 5. Friend support T1 | 3.79 (.59) | −.013 | −.123 | .030 | −.117 | |||

| 6. Friend support T2 | 3.54 (.75) | −.087 | −.183* | −.197* | −.221* | .491*** | ||

| 7. Time with friends | 4.11 (.93) | −.023 | −.117 | −.139 | −.165* | .162* | .217* | |

| 8. COVID‐19 stress | 1.92 (.73) | .274*** | .282*** | .119 | .083 | .152 | .159 | .054 |

Int. Prob. A = adolescent‐reported internalizing problems; Int. Prob. P = parent‐reported adolescent internalizing problems; T1 = before COVID‐19; T2 = during COVID‐19.

*p < .05, ***p < .001.

When all paths were freely estimated, Model 1 (including bidirectional paths between friend support and self‐reported internalizing problems) and Model 4 (including bidirectional paths between friend support and parent‐reported internalizing problems) were saturated. Wald tests showed that constraining paths from gender to friend support and internalizing problems, and from friendship stability to internalizing problems across waves did not result in significantly lower model fit in any of the six models, ps > .192. The path from friendship stability to friend support was not constrained to be equal for both waves, because doing so resulted in significantly poorer model fit for all six models, ps < .025. However, constraining the cross‐lagged paths between friend support and internalizing problems to be equal did not result in poorer fit for both adolescent‐reported internalizing problems (Model 1), Wald χ2(1) = 0.06, p = .804, and parent‐reported internalizing problems (Model 4), Wald χ2(1) = 3.58, p = .059. Therefore, in all subsequent models, these paths were constrained.

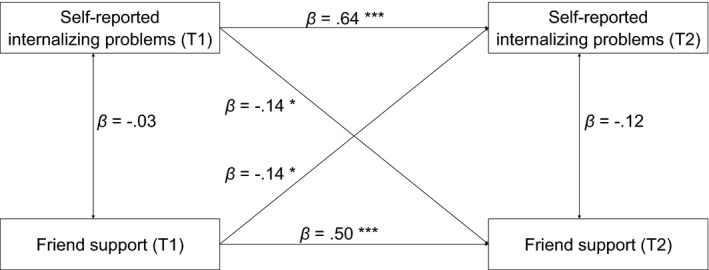

Self‐Reported Internalizing Problems and Friend Support

Model 1 (see Figure 2), including bidirectional links between self‐reported internalizing problems and friend support while controlling for gender and friendship stability, showed good fit to the data, CFI = 1.000, RMSEA = .000 [.000, .037], SRMR = .012. The significant negative bidirectional effects between friend support and internalizing problems showed that adolescents who perceived more friend support before COVID‐19 reported less internalizing problems during COVID‐19 and that adolescents who experienced more internalizing problems before COVID‐19 reported lower friendship quality during COVID‐19, βs = −.14, ps = .011. Furthermore, there were significant stability paths for both friend support, β = .50, p < .001, and internalizing problems, β = .64, p < .001. Gender had significant positive effects on friend support and internalizing problems, which revealed that girls reported more friend support, β = .46, p < .001, and internalizing problems, β = .35, p < .001, than boys. Friendship stability only positively affected friend support before COVID‐19, β = .46, p = .001, but not during COVID‐19, β = −.14, p = .503, and it did not significantly affect internalizing problems, βs = −.10, p s = .237. Within‐time associations between friend support and internalizing problems were not significant before COVID‐19, β = −.03, p = .613, or during COVID‐19, β = −.12, p = .055.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of results for Model 1 (self‐reported internalizing problems).

Note. Not all terms that were included in the model are displayed in the figure. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

Model 2, adding main and interaction effects of time spent with friends on internalizing problems to Model 1, showed good fit to the data, CFI = .974, RMSEA = .045 [.000, .956], SRMR = .064. However, there was no significant main effect of time spent with friends during COVID‐19, β = −.08, p = .174, or interaction effect with friend support before COVID‐19, β = .01, p = .935, suggesting that time spent with friends during COVID‐19 was not related to the level of internalizing problems adolescents experience, either directly or by strengthening the effect of friend support. These results did not change when separately analyzing time spent with friends online and offline.

Model 3, adding main and interaction effects of COVID‐19‐related stress on internalizing problems to Model 1, showed good fit to the data, CFI = .956, RMSEA = .060 [.013, .100], SRMR = .058. There was a significant positive main effect of COVID‐19‐related stress during COVID‐19, β = .15, p = .010, but no interaction effect with friend support before COVID‐19, β = −.06, p = .319, suggesting that adolescents who experienced more COVID‐19‐related stress also experienced more internalizing problems, but stress did not moderate the association between friend support and internalizing problems.

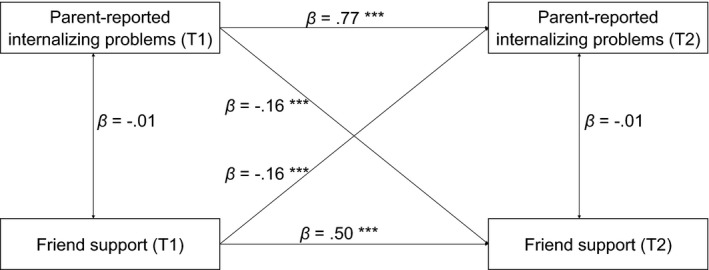

Parent‐Reported Adolescent Internalizing Problems and Friend Support

Model 4 (see Figure 3), including cross‐lagged path model of bidirectional links between parent‐reported adolescent internalizing problems and friend support, while controlling for gender and friendship stability, showed good fit to the data, CFI = .991, RMSEA = .052 [.000, .120], SRMR = .036. The significant negative bidirectional effects between (adolescent‐reported) friend support and parent‐reported internalizing problems showed that adolescents who perceived more friend support before COVID‐19 had less internalizing problems during COVID‐19 according to their parents and that adolescents whose parents reported more adolescent internalizing problems before COVID‐19 experienced lower friendship quality during COVID‐19, βs = −.16, ps < .001. Furthermore, there were significant stability paths for both friend support, β = .50, p < .001, and internalizing problems, β = .77, p < .001. Gender had significant positive effects on friend support and internalizing problems which revealed that girls scored higher on self‐reported friend support, β = .47, p < .001, and parent‐reported internalizing problems, β = .15, p = .042, than boys. Friendship stability had a significant positive effect on friend support before COVID‐19 only, β = −.46, p = .001, but not on friend support during COVID‐19, β = −.22, p = .294, or on internalizing problems, βs = −.02, p s = .813. Within‐time associations between friend support and parent‐reported internalizing problems were not significant before COVID‐19, β = −.01, p = .936, or during COVID‐19, β = −.01, p = .803.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of results for Model 4 (parent‐reported internalizing problems).

Note. Not all terms that were included in the model are displayed in the figure. ***p < .001.

Model 5, adding main and interaction effects of time spent with friends on internalizing problems to Model 4, showed good fit to the data, CFI = .954, RMSEA = .073 [.035, .111], SRMR = .080. However, there was no significant main effect of time spent with friends during COVID‐19, β = −.03, p = .505, or interaction effect with friend support before COVID‐19, β = −.04, p = .451, suggesting that time spent with friend during COVID‐19 was not related to the level of adolescent internalizing problems parents reported, either directly or by strengthening the effect of friend support. These results did not change when separately analyzing time spent with friends online and offline.

Model 6, adding main and interaction effects of COVID‐19‐related stress on internalizing problems to Model 4, showed good fit to the data, CFI = .986, RMSEA = .040 [.000, .084], SRMR = .049. However, there was no significant main effect of COVID‐19‐related stress, β = .00, p = .938, or interaction effect with friend support before COVID‐19, β = .02, p = .662, suggesting that COVID‐19‐related stress was not related to the level of adolescent internalizing problems parents reported, either directly or by affecting the effect of friend support.

Discussion

The current study examined whether pre‐COVID‐19 friend support predicted self‐reported and parent‐reported adolescent internalizing problems during COVID‐19 (while controlling for pre‐COVID‐19 internalizing problems). Furthermore, we tested whether the effect of friend support on internalizing problems was moderated by the time adolescents spent with friends (online or offline) during the COVID‐19 crisis or COVID‐19‐related stress. Results showed that pre‐COVID‐19 friend support was significantly bidirectionally related with both self‐reported and parent‐reported internalizing problems during COVID‐19, after controlling for gender and friendship stability. In contrast to our hypotheses, no significant moderation effects were found. In contrast to some other findings on the effect of the COVID‐19 crisis on mental health (Cohen et al., 2021; Kwong et al., 2020), the overall level of self‐reported (but not parent‐reported) internalizing problems showed a small but significant decrease during the crisis. Possibly, adolescents in our sample experienced the lockdown and homeschooling as a less stressful period and felt better because important tests were canceled or because they had more time to relax. Furthermore, the lockdown was relatively brief: Results may be different after a year of very little face‐to‐face contact with peers and teachers due to the pandemic. Adolescents also reported lower friend support during the crisis than before, which may be partly explained by adolescents spending less time with their friends during the pandemic. It should be noted that the decreases in internalizing symptoms and friend support were significant but small, and there were also many adolescents who reported an increase instead.

Bidirectional Links Between Friend Support and Internalizing Problems

In line with our hypothesis, we found that adolescents who experienced more pre‐COVID‐19 friend support reported significantly less internalizing problems during COVID‐19, after controlling for gender, friendship stability, and pre‐COVID‐19 internalizing problems. This effect was also found when using parent‐reported adolescent internalizing problems. Friend support may directly reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, for example, by reducing loneliness (Nangle et al., 2003). Adolescents who lack close, supportive friendships may be more likely to feel excluded from the peer group and develop internalizing symptoms. Alternatively, friend support may buffer against the effects of life events, such as the COVID‐19 crisis, on mental health, so that adolescents with better friendships develop less psychosocial problems in times of crisis.

As expected, these effects were bidirectional: Adolescents who experienced more internalizing problems before COVID‐19 also reported lower friend support during COVID‐19. Adolescents with higher levels of internalizing symptoms are more likely to withdraw from social relations, which in turn reduces the quality of their close friendships (Biggs et al., 2011). Particularly during COVID‐19, when structural ways to meet friends (such as in school) are more restricted and maintaining peer relationships requires more initiative from adolescents, adolescents with more internalizing symptoms might be more inclined to withdraw from interactions with friends.

Effects of Time Spent With Friends and COVID‐19‐Related Stress

In line with our expectations, we found a main effect of COVID‐19‐related stress on self‐reported (but not parent‐reported) internalizing problems. This is consistent with cross‐sectional studies that showed that adolescents who experienced more COVID‐19 stress also reported more loneliness and depression (Ellis et al., 2020). We did not find COVID‐19‐related stress to moderate the association between friend support and internalizing problems. This suggests that friend support and stress are individual compensatory and risk factors, respectively, but stress does not diminish the effect of friend support or vice versa, which provides evidence for a compensatory model of resilience, rather than a protective model (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005).

In contrast to our hypothesis, we found no main or moderating effect of time spent with friends on the association between friend support and (either self‐ or parent‐reported) internalizing problem. Frequently seeing one’s friends (either offline or online) does not seem to add to or strengthen the protective effect of friend support on internalizing problems. This finding suggests that during the initial lockdown, adolescents still benefited from friend support that they perceived before they were socially isolated regardless of the extent to which they were able to interact with friends online or offline. However, now that COVID‐19 has impacted the world for over a year, adolescents may not be as resilient against the effects of prolonged social isolation.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

An important strength of this study was the prospective longitudinal design, including data before and during the outbreak of COVID‐19. Although it should be noted that this study is observational and not experimental, the prospective longitudinal aspect allowed us to include less ‘biased’ measures of pre‐COVID‐19 friend support and internalizing problems than retrospective studies do. Additionally, we studied bidirectional longitudinal associations and not only cross‐sectional associations between friend support and internalizing problems. Furthermore, we replicated the results using parent‐reported and self‐reported internalizing problems, supporting the robustness of these findings.

This study also included some limitations. First, some adolescents were in full lockdown while completing Wave 2 questionnaires, whereas others were able to partially go to school. Although the frequency of face‐to‐face education during the pandemic (a proxy for the intensity of the lockdown at that moment) was not significantly associated with any of the studied variables, we cannot draw conclusions about how different intensity levels of lockdown might affect the results. Second, the measure for time spent with friends showed moderate reliability and consisted of only three items. Although questions were quite broad, including different types of both online and offline contact, findings may have been different if they had been able to distinguish between quality and quantity of interaction with friends. Third, our sample included only Dutch adolescents in their final year of primary school, and these findings may not generalize to older adolescents or adolescents in other countries.

Future research should study the long‐term, as well as the prolonged effects of the COVID‐19 crisis on youth mental health. Our study showed that, in the short term, adolescents did not seem worse off than before the COVID‐19 crisis. However, as the pandemic continues to affect youth globally for over a year with frequent strict lockdowns, it is likely that after a longer period adolescents suffered more from isolation from their peers and being stuck inside their home, without as many opportunities to socialize, exercise, and receive proper education. It is yet unknown how prolonged isolation affects socio‐emotional and academic development, and future studies should follow up on youth during the extended COVID‐19 crisis.

Conclusion

To conclude, the current study showed that in times of crisis, such as the COVID‐19 pandemic, adolescents benefit from support of their close friends in the prevention of internalizing problems. Although this study only examined the relatively short‐term effects of COVID‐19 on adolescents’ internalizing symptoms and friend support, it is important to take into account the potential protective role of friend support on the effects of continued social isolation during the COVID‐19 lockdowns as well. With prolonged isolation, the effects of staying home, away from peers, may become more negative. Even during the initial months of the COVID‐19 pandemic, our results already show a decline in friend support. While appreciating the necessity of the restrictive measurements to contain the pandemic, governments and youth workers should be aware of the negative effect of the pandemic on friend support and adolescent mental health and should stimulate supportive interactions within the limits of the restrictions as much as possible. These findings could also remain relevant after the pandemic: In other stressful situations (e.g., terrorism; Henrich & Shahar, 2008), having supportive friends may also be a protective factor against psychopathology.

This study was preregistered at OSF (https://osf.io/d27kv/).

This research was supported by a grant of the European Research Council (ERC‐2017‐CoG‐773023 INTRANSITION). Data collection procedure was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social & Behavioural Sciences of Utrecht University. All participants and their parents (if they were below the age of 16) gave their informed consent to participation. The scripts for data analyses will be shared on OSF.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- Aba, G. , Knipprath, S. , & Shahar, G. (2019). Supportive relationships in children and adolescents facing political violence and mass disasters. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21, 83. 10.1007/s11920-019-1068-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the child behavior checklist/4‐18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg M., Dobbelaar S., Boer O. D., Crone E. A. (2021). Perceived stress as mediator for longitudinal effects of the COVID‐19 lockdown on wellbeing of parents and children. Scientific Reports, 11(1). 10.1038/s41598-021-81720-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew, R. (1991). The interactive effects of peer variables on delinquency. Criminology, 29(1), 47–72. 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1991.tb01058.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway, R. , & Bebbington, P. (1987). The buffer theory of social support–A review of the literature. Psychological Medicine, 17(1), 91–108. 10.1017/s0033291700013015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidel, D. C. , Turner, S. M. , & Morris, T. L. (1999). Psychopathology of childhood social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(6), 643–650. 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, B. K. , Vernberg, E. M. , & Wu, Y. P. (2011). Social anxiety and adolescents’ friendships. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 32(6), 802–823. 10.1177/0272431611426145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branquinho, C. , Kelly, C. , Arevalo, L. C. , Santos, A. , & Gaspar de Matos, M. (2020). “Hey, we also have something to say”: A qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people's experiences under COVID‐19. Journal of Community Psychology, 48, 2740–2752. 10.1002/jcop.22453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski, W. M. , Hoza, B. , & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre‐ and early adolescence: The development and psychometric properties of the friendship qualities scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11(3), 471–484. 10.1177/0265407594113011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. New York, NY: Routlegde. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita, B. F. , Yim, L. M. , Moffitt, C. E. , Umemoto, L. A. , & Francis, S. E. (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM‐IV anxiety and depression in children: A revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 835–855. 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00130-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Z. P. , Cosgrove, K. T. , Deville, D. C. , Akeman, E. , Singh, M. K. , White, E. , … Kirlic, N. (2021). The impact of COVID‐19 on adolescent mental health: Preliminary findings from a longitudinal sample of healthy and at‐risk adolescents. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 8. 10.3389/fped.2021.622608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commodari, E. , & La Rosa, V. L. (2020). Adolescents in quarantine during COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy: Perceived health risk, beliefs, psychological experiences and expectations for the future. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 559951. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.559951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B. (2003). The dynamic properties of social support: Decay, growth, and staticity, and their effects on adolescent depression. Social Forces, 81, 953–978. 10.1353/sof.2003.0029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duan, L. , Shao, X. , Wang, Y. , Huang, Y. , Miao, J. , Yang, X. , & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID‐19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, W. E. , Dumas, T. M. , & Forbes, L. M. (2020). Physically isolated but socially connected: Psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID‐19 crisis. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des sciences du comportement, 52(3), 177–187. 10.1037/cbs0000215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, S. , & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26(1), 399–419. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children's perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21, 1016–1024. 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W. , & Buhrmester, D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63, 103–115. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber, J. , & Rao, U. (2014). Depression in children and adolescents. In Lewis M. & Rudolph K. D. (Eds.), Handbook of developmental psychopathology (3rd ed., pp. 489–520). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, C. C. , & Shahar, G. (2008). Social support buffers the effects of terrorism on adolescent depression: Findings from Sderot, Israel. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 1073–1076. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31817eed08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, L. H. C. , Kullberg, M.‐L. , Verkuil, B. , van Zwieten, N. , Wever, M. C. M. , van Houtum, L. A. E. M. , … Elzinga, B. M. (2020). Does the COVID‐19 pandemic impact parents’ and adolescents’ well‐being? An EMA‐study on daily affect and parenting. PLoS One, 15, e0240962. 10.1371/journal.pone.0240962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, A. S. F. , Pearson, R. M. , Adams, M. J. , Northstone, K. , Tilling, K. , Smith, D. , … Timpson, N. J. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID‐19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 218, 334–343. 10.1192/bjp.2020.242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn, P. M. , Rohde, P. , Klein, D. N. , & Seeley, J. R. (1999). Natural course of adolescent major depressive disorder: Continuity into young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(1), 56–63. 10.1097/00004583-199901000-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden‐Andersen, S. , Markiewicz, D. , & Doyle, A.‐B. (2009). Perceived similarity among adolescent friends: The role of reciprocity, friendship quality, and gender. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(5), 617–637. 10.1177/0272431608324372 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. J. , Bao, Y. , Huang, X. , Shi, J. , & Lu, L. (2020). Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID‐19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 347–349. 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. , & Wright, M. O. D. (1998). Cumulative risk and protection models of child maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 2(1), 7–30. 10.1300/J146v02n01_02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K. , & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide (8th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nangle, D. W. , Erdley, C. A. , Newman, J. E. , Mason, C. A. , & Carpenter, E. M. (2003). Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children's loneliness and depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescescent Psychology, 32(4), 546–555. 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelemans, S. A. , Hale, W. W. , Raaijmakers, Q. A. W. , Branje, S. J. T. , van Lier, P. A. C. , & Meeus, W. H. J. (2016). Longitudinal associations between social anxiety symptoms and cannabis use throughout adolescence: The role of peer involvement. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(5), 483–492. 10.1007/s00787-015-0747-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgilés, M. , Morales, A. , Delvecchio, E. , Francisco, R. , Mazzeschi, C. , Pedro, M. , & Espada, J. P. (2021). Coping behaviors and psychological disturbances in youth affected by the COVID‐19 health crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 565657. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.565657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, D. W. , & Anderson, A. L. (2004). Unstructured socializing and rates of delinquency. Criminology, 42, 519–549. https://doi‐org/10.1111/j.1745‐9125.2004.tb00528.x [Google Scholar]

- Rao, U. M. A. , Hammen, C. , & Daley, S. E. (1999). Continuity of depression during the transition to adulthood: A 5‐year longitudinal study of young women. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 908–915. 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 3–13. 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, K. D. , Hammen, C. , Burge, D. , Lindberg, N. , Herzberg, D. , & Daley, S. E. (2000). Toward an interpersonal life‐stress model of depression: The developmental context of stress generation. Developmental Psychopathology, 12(2), 215–234. 10.1017/s0954579400002066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari, N. , Hosseinian‐Far, A. , Jalali, R. , Vaisi‐Raygani, A. , Rasoulpoor, S. , Mohammadi, M. , … Khaledi‐Paveh, B. (2020). Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 57. 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, G. , Cohen, G. , Grogan, K. E. , Barile, J. P. , & Henrich, C. C. (2009). Terrorism‐related perceived stress, adolescent depression, and social support from friends. Pediatrics, 124, e235–e240. 10.1542/peds.2008-2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spirito, A. , Francis, G. , Overholser, J. , & Frank, N. (1996). Coping, depression, and adolescent suicide attempts. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(2), 147. 10.1207/s15374424jccp2502_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, L. R. (2015). When support seeking backfires: Co‐rumination, excessive reassurance seeking, and depressed mood in the daily lives of young adults. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34(5), 436–457. 10.1521/jscp.2015.34.5.436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst, M. , & Coffe, H. (2012). How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well‐being. Social Indicators Research, 107(3), 509–529. 10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YoungMinds . (2020). Coronavirus: Impact on young people with mental health needs. Survey 3: Autumn 2020 – Return to school. Retrieved from https://youngminds.org.uk/media/4119/youngminds‐survey‐with‐young‐people‐returning‐to‐school‐coronavirus‐report‐autumn‐report.pdf [Google Scholar]