Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of two dosing regimens of fremanezumab in Japanese and Korean patients with episodic migraine.

Background

Episodic migraine, which accounts for more than 90% of migraine cases, is inadequately addressed by widely available preventive therapies. Fremanezumab, a monoclonal antibody that selectively targets the trigeminal sensory neuropeptide calcitonin gene‐related peptide involved in migraine pathogenesis, has demonstrated efficacy in international Phase 3 trials of patients with both chronic and episodic migraine.

Methods

This Phase 3 randomized, placebo‐controlled trial randomly assigned patients with episodic migraine to receive subcutaneous fremanezumab monthly (225 mg at baseline, week 4, and week 8), fremanezumab quarterly (675 mg at baseline and placebo at weeks 4 and 8), or matching placebo. The primary endpoint was the mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12‐week treatment period after the first dose.

Results

Of 357 patients enrolled (safety set, n = 356; full analysis set, n = 354), the least‐squares mean (±standard error) reductions in the average number of migraine days per month during 12 weeks were significantly greater with fremanezumab monthly (−4.0 ± 0.4, n = 121) and fremanezumab quarterly (−4.0 ± 0.4, n = 117) than with placebo (−1.0 ± 0.4, n = 116; p < 0.0001 for both comparisons). The proportion of patients reaching at least a 50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12‐week period after initial administration was also significantly improved with fremanezumab (fremanezumab monthly, 41.3%; fremanezumab quarterly, 45.3%; placebo, 11.2%; p < 0.0001 for both comparisons) as were other secondary endpoints (p < 0.001 for all comparisons between fremanezumab and placebo). Injection‐site reactions were more common in fremanezumab‐treated patients (fremanezumab monthly, 25.6%; fremanezumab quarterly, 29.7%; placebo, 21.4%).

Conclusion

Fremanezumab prevents episodic migraine in Japanese and Korean patients to a similar extent than in previously reported populations with no new safety concerns.

Keywords: calcitonin gene‐related peptide, episodic migraine, fremanezumab, Japanese, Korean

Abbreviations

- ANCOVA

analysis of covariance

- CGRP

calcitonin gene‐related peptide

- eC‐SSRS

electronic Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale

- ICHD

International Classification of Headache Disorders

- LSM

least‐squares mean

- MIDAS

Migraine Disability Assessment questionnaire

- MMRM

mixed‐effects model for repeated measures

- SD

standard deviation

- SE

standard error

- TEAEs

treatment‐emergent adverse events

INTRODUCTION

Episodic migraine, migraine with or without aura that occurs with <15 headache days per month, accounts for more than 90% of migraine cases,1 but is associated with less headache‐related disability, quality of life impairment, and comorbidities than chronic migraine.1, 2, 3 Furthermore, episodic migraine progresses to chronic migraine at a rate of 2.5% of cases each year and, conversely, chronic migraine may revert to episodic migraine.2 Although preventive therapies are strongly recommended for both chronic migraine and episodic migraine occurring on four headache days per month or more, many patients do not receive such medications,4 persistence is often poor,5, 6, 7 and existing agents used for migraine prevention are often associated with significant adverse reactions.8 A recent Japanese real‐world treatment patterns survey reported that many patients with episodic migraine report issues with the efficacy of preventive treatment, in addition to adverse events and concerns regarding long‐term safety.9

In this setting, monoclonal antibodies targeting the trigeminal sensory neuropeptide calcitonin gene‐related peptide (CGRP) or the CGRP receptor have emerged as effective preventive medications for migraine with few or no adverse reactions attributable to them.10, 11 Guidelines such as those of the European Headache Federation have made evidence‐based recommendations for the use of monoclonal antibodies against CGRP or its receptor for prevention of both episodic and chronic migraine.12 Among these, fremanezumab is a fully humanized IgG2Δa/kappa monoclonal antibody that potently and selectively binds to both isoforms of CGRP and has demonstrated efficacy in several Phase 213, 14 and Phase 3 trials,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 including in patients with difficult‐to‐treat migraine who have had an inadequate response to up to four classes of migraine‐preventive medications.15

A Phase 1 study has assessed the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of fremanezumab in Japanese and Caucasian healthy volunteers.21 Furthermore, Japanese patients with episodic migraine have been included in previous global clinical trials of fremanezumab.19 This trial is dedicated to confirm the efficacy of fremanezumab in Japanese patients with episodic migraine. The inclusion of patients from South Korea in this trial was deemed acceptable based on the lack of reported population differences in CGRP polymorphism, minimal differences between Japan and South Korea in diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, and therapeutic approach.

In this context of previous trial results, we hypothesized that monthly and quarterly subcutaneous administration of fremanezumab would provide improved efficacy and similar safety compared with placebo for preventive treatment of episodic migraine in Japanese and Korean patients.

METHODS

Trial design

This was a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group Phase 2b/3 trial conducted in Japanese and Korean patients with episodic migraine between November 2017 and November 2019 (Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03303092). Patients were enrolled from 57 institutions in Japan and 10 institutions in Korea (Table S1) with enrolment and informed consent procedures performed at each investigational site by the investigators or their designees. The trial design is similar to that of a previous global Phase 3 trial of fremanezumab in patients with episodic migraine and consisted of a 4‐week screening period and a 12‐week double‐blind treatment period.19 Male or female patients aged 18–70 years were mainly considered eligible if they: (a) had a history of migraine with onset ≤50 years of age according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version, ICHD‐3 beta)22 or clinical judgment suggested a migraine diagnosis for ≥12 months before giving informed consent; (b) met the criteria for episodic migraine during the 28‐day screening period, defined as a headache occurring on 6–14 days, with ≥4 days fulfilling ICHD‐3 beta criteria for migraine with or without aura, probable migraine, or use of triptans or ergot derivative. The main exclusion criteria were the lack of efficacy of at least two of four clusters of preventive medications despite an adequate trial and clinically significant major organ or ophthalmic disease. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table S2.

Informed consent was documented on a written informed consent form approved by the same institutional review board or independent ethics committee/ethics committee that approved the trial protocol and which complied with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guideline and local regulatory requirements.

Treatment

After the initial screening period (Visit 1), eligible patients were randomly assigned at baseline (Visit 2) in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive monthly fremanezumab, quarterly fremanezumab, or placebo via subcutaneous injection. Randomization was performed by electronic interactive response technology (IRT), with stratification according to sex, country, and baseline use of preventive medication (yes or no). Both patients and all parties involved in the investigation were blinded to the trial‐group assignments. Foreknowledge of treatment assignment was concealed from both the investigators and patients by use of a randomization code generated as part of the IRT. This was administered by an external contract research organization, and the study sponsor was also blinded to treatment assignment through the use of the randomization codes that were only allowed to be broken in case of a medical emergency.

Dosing of fremanezumab was based on the results of a previous Phase 2b trial in patients with episodic migraine.14 Patients in the fremanezumab monthly group received fremanezumab 225 mg as a single active subcutaneous injection (225 mg/1.5 ml) and placebo as two 1.5 ml injections at baseline (Visit 2) and then fremanezumab 225 mg as a single active injection (225 mg/1.5 ml) at month 1 (Visit 3) and month 2 (Visit 4). Patients in the fremanezumab quarterly group received fremanezumab 675 mg as three active injections (225 mg/1.5 ml each) at baseline (Visit 2) and placebo as a single 1.5 ml injection at month 1 (Visit 3) and month 2 (Visit 4). Placebo group patients received three 1.5 ml placebo injections at baseline (Visit 2) and a single 1.5 ml placebo injection at month 1 (Visit 3) and month 2 (Visit 4, Figure S1). To ensure blinding was not compromised, interventions were made similar to each other by use of identical packaging and identical prefilled syringes each containing 1.5 ml of the investigational product. The number of injections provided at each visit that involved treatment administration was also identical to avoid investigators or patients becoming aware of study medication assignment.

Concomitant migraine‐preventive medications were allowed in no more than 30% of the trial patients if the dose had not changed for 2 months prior to screening and was kept consistent throughout the trial; otherwise, they were generally prohibited (Table S3).

Outcomes

Patients were observed at five scheduled visits (screening [Visit 1], baseline [dose 1; Visit 2], week 4 [dose 2, Visit 3], week 8 [dose 3, Visit 4], and at the end of treatment [week 12 or early withdrawal, Visit 5]). Data on headache such as occurrence, duration, severity, migraine characteristics (e.g., aura, vomiting), and medication use were recorded by patients daily using an electronic headache diary.

The primary endpoint was the mean change from baseline in the monthly (28‐day) average number of migraine days during the 12‐week period after the first dose of fremanezumab or placebo (see Table S4 for definition of migraine days). This is consistent with the primary endpoint recommended by guidelines of the International Headache Society guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine.23

Secondary efficacy endpoints during the 12‐week period after the first dose of fremanezumab or placebo were (a) proportion of patients reaching ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days, (b) mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of days with use of any acute headache medications, and (c) mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days in patients not receiving concomitant migraine‐preventive medications. A further secondary endpoint determined at 4 weeks after the final (third) dose of fremanezumab was the mean change from baseline in disability score, as measured by the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire.24

Safety was primarily assessed by the occurrence of treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs), which were classified according to severity, seriousness, and causal relationship to trial medication or discontinuation. TEAEs recorded in case report forms were substituted with preferred terms according to MedDRA version 22.0. In addition to TEAEs, safety was assessed by clinical laboratory tests (chemistry, hematology, coagulation, and urinalysis), 12‐lead ECG, physical examination, vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, temperature, and respiratory rate), weight, and the electronic Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale (eC‐SSRS).25 Antidrug antibodies were assessed in patients who received fremanezumab during the trial.

Statistics

Sample size calculations were based on results of a previous Phase 2b trial in which the difference between the monthly fremanezumab and placebo groups in the mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12‐week period was calculated as −2.7 days.14 To be conservative, a treatment difference between each fremanezumab group and the placebo group in the current trial was assumed to be 1.8 (standard deviation [SD], 4.1) days for which a sample size of 110 patients per group provided more than 90% power for the trial to succeed at a significance level of 0.05 (two‐sided). After trial initiation, it was discovered that patients in the fremanezumab monthly group had been administered a different initial dose (675 mg) to that planned in the protocol due to an error in the IRT system. To ensure the safety of trial patients, the sponsor halted further administration of fremanezumab to all patients who had already been enrolled in the trial. The 96 patients randomized before trial suspension were defined as Cohort 1 and are not included in this report. Cohort 2 was established to resume the trial using the originally planned sample size of 330 patients and data from these patients form the basis of the results reported for this trial. Enrolment for Cohort 2 was stopped when the target sample size was reached. There was no data safety monitoring board, and no interim analyses were planned.

The safety set included all randomly assigned patients who received at least one dose of a trial regimen in Cohort 2. The full analysis set, which was used for all efficacy analyses, included all patients in the safety set from Cohort 2 who had at least 10 days of baseline and postbaseline assessment data on monthly average number of migraine days.

Descriptive statistics related to baseline characteristics and adverse events were evaluated using mean, SD, or absolute frequency count and proportions as appropriate. The primary endpoint was analyzed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model that included treatment, sex, country, and baseline preventive medication use as fixed effects and baseline number of migraine days and years since onset of migraine as covariates. Two‐sided 95% confidence intervals and p‐values were constructed for the least‐squares mean (LSM) differences between each fremanezumab group and the placebo group. Adjustment for multiple comparisons was accomplished using a fixed sequence procedure. If superiority of the fremanezumab monthly group versus placebo was confirmed at a two‐sided significance level of 0.05, then the fremanezumab quarterly group versus placebo was also tested at a two‐sided significance level of 0.05. For the ANCOVA, when the number of evaluation days of the electronic headache diary after administration was 10 days or more, headache diary data were normalized to 28 days of data during the 3‐month period. Therefore, there were no missing values for the primary analysis by ANCOVA. The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was performed as a sensitivity analysis for the normality assumption when comparing each fremanezumab group with placebo. In addition to the primary analysis by ANCOVA, a mixed‐effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) analysis was also used to estimate the mean change from baseline in the monthly number of migraine days by each month. The MMRM included treatment, sex, country, baseline migraine‐preventive medications use, month, and treatment‐by‐month interaction as fixed effects, and baseline value and years since onset of migraine as covariates. For the MMRM analysis, data were also normalized to 28 days of data when the number of evaluation days of the electronic headache diary in each month was 10 days or more. However, data were not available for patients who discontinued, so data for evaluation may be missing for a particular month.

For the secondary endpoint related to the proportion of patients reaching ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days, each fremanezumab group and the placebo group were compared using Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by baseline preventive medication use. Differences between each fremanezumab group and the placebo group and two‐sided 95% confidence interval (a Mantel–Haenszel estimator of the difference and its two‐sided 95% confidence interval) were computed. The ANCOVA model was applied to secondary endpoints related to the mean changes from baseline in the monthly average number of days with use of any acute headache medications and the monthly average number of migraine days in patients not receiving concomitant migraine‐preventive medications. The LS mean ± standard error (SE) of monthly change from baseline values estimated by the MMRM were also plotted. Finally, for the mean change from baseline in MIDAS disability score, the ANCOVA model was performed in a manner similar to that of the primary endpoint.

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical calculations.

RESULTS

Subject disposition and baseline characteristics

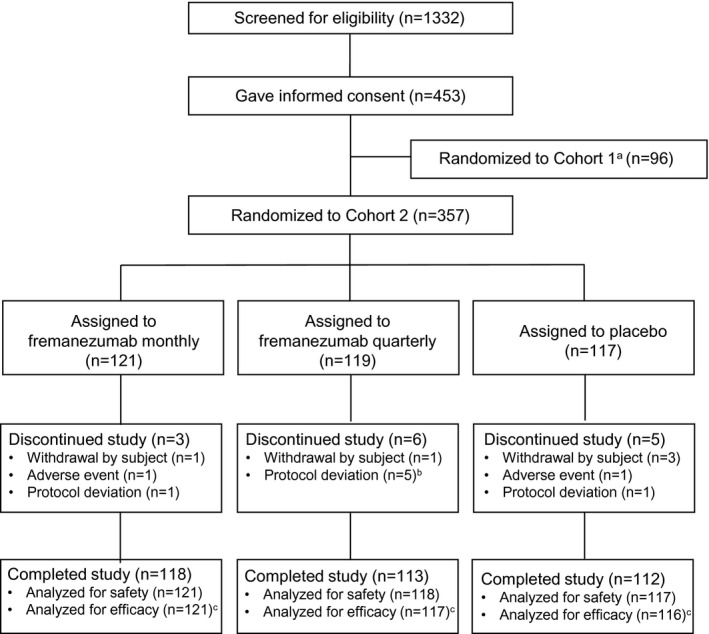

In total, 357 patients were randomized, and trial treatment was administered to 356 patients (fremanezumab monthly group, n = 121; fremanezumab quarterly group, n = 118; placebo group, n = 117). Figure 1 shows the flow of patients in Cohort 2 throughout the phases of the trial. Of the randomized patients, 343 patients (96.1%) completed the trial with the most common reason for discontinuation among the 14 patients who discontinued the trial being protocol deviation (n = 7), followed by withdrawal of consent (n = 5) and adverse events (n = 2). The percentage of trial completion was similar in the fremanezumab monthly (n = 118/121; 97.5%), fremanezumab quarterly (n = 113/119; 95.0%), and placebo (n = 112/117; 95.7%) groups.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of patient disposition throughout the phases of the trial. aCohort 1 trial suspended due to dose error caused by interactive response technology. bIncludes one patient who did not receive trial drug. cA total of three patients were excluded from the efficacy analysis (full analysis set) as they had less than 10 days of baseline and postbaseline assessment data on monthly average number of migraine days

Demographic and other baseline characteristics were also similar among the treatment groups, including in relation to the proportion of females, age, and weight/body mass index (Table 1). Headache characteristics at baseline showed little variation between groups with regard to the number of days with headache of any severity and duration (range 11.0–11.1 days), number of headache days of at least moderate severity (range 7.5–8.0 days), number of migraine days per month (range 8.6–9.0 days), the proportion of patients receiving migraine‐preventive medications (range 18.8%–19.8%), and the mean number of years since onset of migraine (range 18.3–22.0 years).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

| Fremanezumab | Placebo (n = 117) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly (n = 121) | Quarterly (n = 119) | Total (n = 240) | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 44.4 (9.5) | 41.9 (10.1) | 43.1 (9.8) | 44.2 (10.7) |

| Country | ||||

| Japan, n (%) | 102 (84.3) | 101 (84.9) | 203 (84.6) | 98 (83.8) |

| Korea, n (%) | 19 (15.7) | 18 (15.1) | 37 (15.4) | 19 (16.2) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 23.0 (4.0) | 22.5 (3.4) | 22.7 (3.7) | 22.8 (3.5) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 101 (83.5) | 101 (84.9) | 202 (84.2) | 100 (85.5) |

| Disease history | ||||

| Time since onset of migraine, mean year (SD) | 22.0 (12.9) | 18.3 (11.4) | 20.2 (12.3) | 19.4 (13.3) |

| Use of migraine‐preventive medications at baseline, yes, n (%) | 24 (19.8) | 23 (19.3) | 47 (19.6) | 22 (18.8) |

| n = 121 | n = 118 | n = 239 | n = 117 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease characteristics during 28‐day preintervention period | ||||

| Number of days with headache of any severity and duration, mean (SD) | 11.0 (2.1) | 11.0 (2.5) | 11.0 (2.3) | 11.1 (2.5) |

| Number of headache days of at least moderate severity, mean (SD) | 7.6 (2.5) | 7.5 (2.8) | 7.5 (2.6) | 8.0 (2.8) |

| Number of migraine days, mean (SD) | 8.6 (2.5) | 8.7 (2.5) | 8.7 (2.5) | 9.0 (2.8) |

| Use of any acute headache medications, yes, n (%) | 120 (99.2) | 117 (98.3) | 237 (98.8) | 117 (100.0) |

| Use of migraine‐specific acute headache medicationsa, yes, n (%) | 115 (95.0) | 110 (92.4) | 225 (93.8) | 114 (97.4) |

Triptans and ergot compounds.

Efficacy

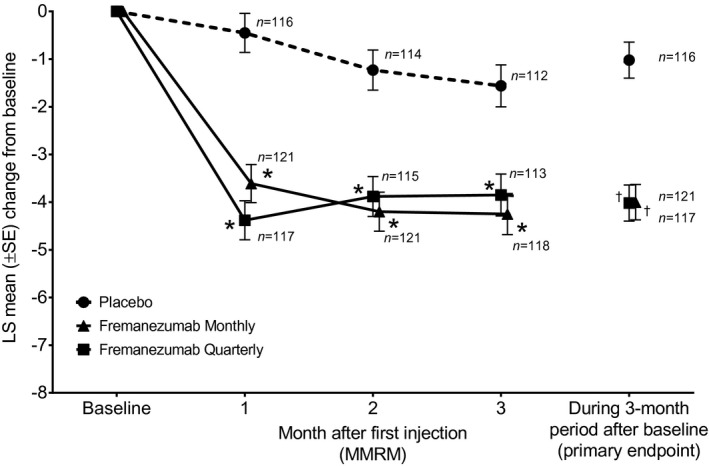

Regarding the primary endpoint, the LSM ± SE change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12‐week period after initial trial medication administration was −4.0 ± 0.4 days, −4.0 ± 0.4 days, and −1.0 ± 0.4 days in the fremanezumab monthly, fremanezumab quarterly, and placebo groups, respectively (ANCOVA for 12‐week analysis). This corresponded to a difference in the mean (95% CI) change versus placebo of −3.0 ± 0.4 (−3.74, −2.23) days in the fremanezumab monthly group and −3.0 ± 0.4 (−3.76, −2.24) days in the fremanezumab quarterly group (p < 0.001 vs. placebo for both comparisons). Results using a sensitivity analysis by the Wilcoxon rank‐sum test confirmed the results of the primary endpoint. According to MMRM analysis for each monthly visit, the LSM ± SE change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days was greater in both fremanezumab treatment groups compared with placebo at all visits (p < 0.001; Figure 2). A reduction in the number of migraine days in comparison with the placebo group was observed in both fremanezumab groups from 4 weeks after initial administration (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Changes from baseline in the monthly (28‐day) average number of migraine days (full analysis set population). An asterisk denotes p < 0.0001 for the comparison of fremanezumab monthly or quarterly with placebo; mixed‐effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) analysis. A dagger denotes p < 0.0001 for the comparison of fremanezumab monthly or quarterly with placebo; primary endpoint

Results of the primary and secondary efficacy endpoints are summarized in Table 2. Over the 12‐week treatment period, the proportion of patients reaching ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days was greater in patients who received either fremanezumab monthly (41.3%) or fremanezumab quarterly (45.3%) compared with patients who received placebo (11.2%; p < 0.001 for both comparisons). Similarly, the mean reduction from baseline in the monthly average number of days with use of any acute headache medications was greater in patients who received either fremanezumab monthly (−3.3 ± 0.3) or fremanezumab quarterly (−3.3 ± 0.4) compared with placebo recipients (−0.5 ± 0.4; p < 0.001 for both comparisons). The mean reduction in monthly average number of migraine days in patients not receiving concomitant migraine‐preventive medications per month was also greater in patients who received fremanezumab monthly (−4.4 ± 0.4) or fremanezumab quarterly (−4.2 ± 0.4) than patients who received placebo (−1.4 ± 0.4; p < 0.0001 for both comparisons). Finally, MIDAS questionnaire disability scores assessed at 4 weeks after the final (third) injection were also reduced to a greater extent with fremanezumab (fremanezumab monthly, −12.6 ± 1.4; fremanezumab quarterly, −12.6 ± 1.5) compared with placebo (−7.4 ± 1.5; p < 0.001 for both comparisons).

TABLE 2.

Summary of primary and secondary efficacy endpoints

| Fremanezumab | Placebo (n = 116) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly (n = 121) | Quarterly (n = 117) | ||

| Primary endpoint | |||

| Average number of migraine days per month, mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 3.0 | 5.0 ± 3.3 | 8.2 ± 3.7 |

| Mean change from baseline during 12‐week period ± SE | −4.0 ± 0.4 | −4.0 ± 0.4 | −1.0 ± 0.4 |

| Difference versus placebo (95% CI, p)a | −3.0 ± 0.4 (−3.74, −2.23; p < 0.0001) | −3.0 ± 0.4 (−3.76, −2.24; p < 0.0001) | |

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| Proportion of patients reaching ≥50% reduction in the average number of migraine days per month from baseline during the 12‐week period after the first dose of study medication | |||

| Number of patients with reduction (%) | 50 (41.3) | 53 (45.3) | 13 (11.2) |

| Difference versus placebo, % (95% CI, p)b | 30.1 (19.6, 40.6; p < 0.0001) | 34.1 (23.4, 44.7; p < 0.0001) | |

| Average number of days with use of any acute headache medications per month | |||

| Mean change from baseline during 12‐week period ± SE | −3.3 ± 0.3 | −3.3 ± 0.4 | −0.5 ± 0.4 |

| Difference ± SE versus placebo (95% CI, p)a | −2.8 ± 0.4 (−3.55, −2.14; p < 0.0001) | −2.8 ± 0.4 (−3.54, −2.12; p < 0.0001) | |

| Average number of migraine days in patients not receiving concomitant migraine‐preventive medications per month | |||

| Number of patients evaluated | 97 | 94 | 94 |

| Mean change from baseline during 12‐week period ± SE | −4.4 ± 0.4 | −4.2 ± 0.4 | −1.4 ± 0.4 |

| Difference ± SE versus placebo (95% CI, p)a | −3.0 ± 0.4 (−3.82, −2.21; p < 0.0001) | −2.8 ± 0.4 (−3.62, −2.01; p < 0.0001) | |

| MIDAS score | |||

| Number of patients evaluated | 118 | 113 | 112 |

| Mean change from baseline at 4 weeks after third (final) injection ± SE | −12.6 ± 1.4 | −12.6 ± 1.5 | −7.4 ± 1.5 |

| Difference ± SE versus placebo (95% CI, p)a | −5.2 ± 1.5 (−8.14, −2.33; p < 0.001) | −5.1 ± 1.5 (−8.09, −2.20; p < 0.001) | |

ANCOVA model for change from baseline includes treatment, sex, country, and baseline preventive medication use (yes/no) as fixed effects and baseline value and years since onset of migraine as covariates.

Comparisons conducted using Mantel–Haenszel test stratified by baseline preventive medication use (yes/no).

Safety

Overall, TEAEs in the safety set (n = 356) occurred in 57.0% of the fremanezumab monthly group, 62.7% of the fremanezumab quarterly group, and 65.8% of patients in the placebo group (Table 3). No serious TEAEs were observed, and almost all events were rated as mild to moderate in severity with the exception of one severe TEAE in a placebo‐treated patient. One patient each in the fremanezumab monthly and placebo group had TEAEs, which led to trial discontinuation. Injection‐site reactions were the most common TEAE potentially related to trial treatment and occurred in 31 patients (25.6%) in the fremanezumab monthly group, 35 patients (29.7%) in the fremanezumab quarterly group, and 25 patients (21.4%) in the placebo group. The incidences of erythema and induration were greater in the fremanezumab monthly group and injection‐site pain was up to approximately two times greater with fremanezumab (9.1%–13.6%) compared with placebo (6.0%). Other TEAEs that occurred more than twice as frequently with fremanezumab were injection‐site pruritus (fremanezumab monthly, 5.8%; fremanezumab quarterly, 1.7%; placebo, 0.0%) and influenza (fremanezumab monthly, 5.0%; fremanezumab quarterly, 1.7%; placebo, 0.9%).

TABLE 3.

Adverse events

| Fremanezumab | Placebo (n = 117) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly (n = 121) | Quarterly (n = 118) | Total (n = 239) | ||

| Patients with at least one TEAEa | 69 (57.0) | 74 (62.7) | 143 (59.8) | 77 (65.8) |

| Patients with at least one potentially drug‐related TEAE | 32 (26.4) | 37 (31.4) | 69 (28.9) | 28 (23.9) |

| Patients with at least one serious TEAE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with any TEAEs leading to discontinuation of the trial | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with adverse events reported in >2% of patients in any group | ||||

| Injection‐site reactions | 31 (25.6) | 35 (29.7) | 66 (27.6) | 25 (21.4) |

| Erythema | 19 (15.7) | 14 (11.9) | 33 (13.8) | 15 (12.8) |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.4) | 5 (2.1) | 1 (0.9) |

| Induration | 18 (14.9) | 14 (11.9) | 32 (13.4) | 12 (10.3) |

| Pain | 11 (9.1) | 16 (13.6) | 27 (11.3) | 7 (6.0) |

| Pruritus | 7 (5.8) | 2 (1.7) | 9 (3.8) | 0 |

| Swelling | 4 (3.3) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (2.5) | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | ||||

| Influenza | 6 (5.0) | 2 (1.7) | 8 (3.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 17 (14.0) | 15 (12.7) | 32 (13.4) | 16 (13.7) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.5) | 4 (1.7) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 3 (2.5) | 3 (1.3) | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (2.6) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 0 | 3 (2.5) | 3 (1.3) | 0 |

| Dizziness | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (2.6) |

| Headache | 2 (1.7) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (1.7) | 4 (3.4) |

| Migraine | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.6) |

| Eczema | 3 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (1.7) | 0 |

| Protocol‐defined adverse events of special interest | ||||

| Cardiovascular events | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 3 (2.6) |

| Hepatic enzyme increased | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) |

| Hepatic function abnormal | 2 (1.7) | 0 | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Hy's law eventsb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ophthalmic events of at least moderate severity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe hypersensitivity reactions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Adverse events were collected by coding in MedDRA version 22.0.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events, any adverse events that occurred after treatment started.

Defined as aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase ≥3 × upper limit of normal (ULN) and total bilirubin ≥2 × ULN or International Normalized Ratio (INR) >1.5.

Clinically significant changes in vital signs were recorded in a small proportion of patients, but the incidence was not greater in either fremanezumab group than in the placebo group. There were no significant ECG findings in any treatment group. Changes in laboratory parameters (serum chemistry, hematology, coagulation, and urinalysis) were not considered clinically significant and also occurred in a similar proportion of patients in fremanezumab and placebo groups. In terms of the eC‐SSRS measure, only one patient in the placebo group was rated as positive after the first dose of trial medication. Finally, treatment‐related antidrug antibodies were observed in 3 of 239 fremanezumab‐treated patients (1.3%) with neutralizing antibody observed in one patient.

DISCUSSION

Results of this Phase 3 trial of fremanezumab in Japanese and Korean patients with episodic migraine demonstrated a significant benefit of fremanezumab either administered monthly or quarterly in terms of the primary endpoint of reduction in the average number of migraine days per month (equivalent to a reduction of approximately 3 days for either fremanezumab regimen versus placebo). Improvements (p < 0.0001) were also seen in secondary endpoints, which included the proportion of patients reaching at least 50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days of at least moderate severity, mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of days with use of any acute headache medications, and mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days in patients not receiving concomitant migraine‐preventive medications. Headache‐related disability improvements with fremanezumab at 4 weeks after final administration were also greater than with placebo (fremanezumab monthly, p < 0.001; fremanezumab quarterly, p < 0.001). Many of these improvements versus placebo overall were also noted at 4 weeks, which is important to emphasize given that many current prophylactic medications are associated with premature discontinuation.6 Fremanezumab was also generally well tolerated with a low rate of discontinuation due to adverse events. As expected from previous trial findings, injection‐site reactions were the most common adverse event, and these reactions tended to occur in a higher proportion of fremanezumab‐treated patients.

Efficacy results in the present trial were consistent with those reported in similar but larger international Phase 2b and Phase 3 trials of patients with episodic migraine.14, 19 A relatively lower placebo response appears to be present in the current trial although the reason for this is not clear as blinding was assured by the study procedures. In a Phase 2b trial of 297 patients with high‐frequency episodic migraine, the reduction from baseline to 9–12 weeks in migraine days versus placebo for patients who received fremanezumab monthly (2.8 days) was almost identical to that of the present trial.14 A Phase 3 trial of 875 enrolled patients with episodic migraine found a statistically significant difference with fremanezumab monthly of −1.5 days and with fremanezumab quarterly of −1.3 days versus placebo (p < 0.001 for both comparisons).19 Findings related to secondary efficacy endpoints, including disability, were also similar between the present trial and earlier trials. This confirms the assumption, supported by earlier clinical studies, that fremanezumab provides a comparable overall response in Japanese and Korean patients with Caucasian and mixed populations. The favorable adverse event profile of fremanezumab noted in this trial is also consistent with previous clinical trials. As noted previously regarding adverse events of special interest, there was a greater incidence of several injection‐site reactions, especially pain, but no clinically significant concerns related to hepatic, ophthalmic, or cardiac injury as well as suicidality. A numerically greater incidence of influenza noted in the fremanezumab quarterly group was not considered to be related to study medication by investigators.

Inclusion of a quarterly dose regimen and patients receiving certain concomitant preventive medications is a key strength of this trial that allows assessment of more choice in dosing and treatment in likely real‐world conditions. The main limitations of this trial have been noted previously in some Phase 3 trials of fremanezumab,17, 19 and include the inability to assess the efficacy or safety of fremanezumab in patients with more refractory disease or coexisting diseases and over evaluation periods greater than 12 weeks.

CONCLUSION

Fremanezumab provides effective prevention against episodic migraine in Japanese and Korean patients. Overall efficacy and safety were comparable with those noted in international trials of mainly Caucasian patients with no safety concerns raised.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD APPROVAL

Approval was granted by the relevant institutional review board or independent ethics committee/ethics committee that approved the trial protocol.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, and Noboru Imai report personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Byung‐Kun Kim reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; consultation fees from Teva Korea and Sanofi Korea; consultation and lecture fees from Lundbeck Korea; and lecture fees from Lilly Korea, Allergan Korea, SK‐Pharma, and YuYu Pharma. Xiaoping Ning is a full‐time employee of Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D. Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba, Hiroyuki Kondo, and Nobuyuki Koga are full‐time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Byung‐Kun Kim, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, Noboru Imai, Xiaoping Ning, Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba. Acquisition of data: Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Byung‐Kun Kim, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, Noboru Imai, Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba. Analysis and interpretation of data: Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Byung‐Kun Kim, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, Noboru Imai, Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba. Drafting of the manuscript: Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Byung‐Kun Kim, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, Noboru Imai, Xiaoping Ning, Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba, Hiroyuki Kondo, Nobuyuki Koga. Revising it for intellectual content: Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Byung‐Kun Kim, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, Noboru Imai, Xiaoping Ning, Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba, Hiroyuki Kondo, Nobuyuki Koga. Final approval of the completed manuscript: Fumihiko Sakai, Norihiro Suzuki, Byung‐Kun Kim, Yoshihisa Tatsuoka, Noboru Imai, Xiaoping Ning, Miki Ishida, Kaori Nagano, Katsuhiro Iba, Hiroyuki Kondo, Nobuyuki Koga.

CLINICAL TRIALS REGISTRATION NUMBER

NCT03303092 (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all patients for their participation in the trial, and all trial sites, investigators, and all clinical research staff for their contributions. We also thank Yoshiko Okamoto, PhD, and Mark Snape, MBBS, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, for medical writing assistance, which was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. All authors contributed to writing the introduction and discussion sections.

Sakai F, Suzuki N, Kim B‐K, et al. Efficacy and safety of fremanezumab for episodic migraine prevention: multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, parallel‐group trial in Japanese and Korean patients. Headache. 2021;61:1102–1111. 10.1111/head.14178

Funding information

This work was supported by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Anonymized individual participant data that underlie the results of this study will be shared with researchers to achieve aims prespecified in a methodologically sound research proposal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lipton RB, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML. A comparison of the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study and American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study: demographics and headache‐related disability. Headache. 2016;56:1280‐1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Manack AN, Lipton RB. Defining the differences between episodic migraine and chronic migraine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:86‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Park SP. The role of headache chronicity among predictors contributing to quality of life in patients with migraine: a hospital‐based study. J Headache Pain. 2014;15:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the Second International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS‐II). Headache. 2013;53:644‐655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonafede M, Wilson K, Xue F. Long‐term treatment patterns of prophylactic and acute migraine medications and incidence of opioid‐related adverse events in patients with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:1086‐1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolley JM, Bonafede MM, Maiese BA, Lenz RA. Migraine prophylaxis and acute treatment patterns among commercially insured patients in the United States. Headache. 2017;57:1399‐1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Adherence to oral migraine‐preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35:478‐488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ha H, Gonzalez A. Migraine headache prophylaxis. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99:17‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, et al. Real‐world treatment patterns and patient‐reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, Krause DN. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies—successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:338‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao G, Yu T, Han X, Mao X, Li B. Therapeutic effects and safety of olcegepant and telcagepant for migraine: a meta‐analysis. Neural Regen Res. 2013;8:938‐947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacco S, Bendtsen L, Ashina M, et al. European headache federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies acting on the calcitonin gene related peptide or its receptor for migraine prevention. J Headache Pain. 2019;20:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bigal ME, Dodick DW, Krymchantowski AV, et al. TEV‐48125 for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine: efficacy at early time points. Neurology. 2016;87:41‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bigal ME, Edvinsson L, Rapoport AM, et al. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of TEV‐48125 for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2b study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:1091‐1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, et al. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2019;394:1030‐1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halker Singh RB, Aycardi E, Bigal ME, Loupe PS, McDonald M, Dodick DW. Sustained reductions in migraine days, moderate‐to‐severe headache days and days with acute medication use for HFEM and CM patients taking fremanezumab: post‐hoc analyses from phase 2 trials. Cephalalgia. 2019;39:52‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2113‐2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.VanderPluym J, Dodick DW, Lipton RB, Ma Y, Loupe PS, Bigal ME. Fremanezumab for preventive treatment of migraine: functional status on headache‐free days. Neurology. 2018;91:e1152‐e1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, et al. Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:1999‐2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goadsby PJ, Silberstein SD, Yeung PP, et al. Long‐term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of fremanezumab in migraine: a randomized study. Neurology. 2020;95:e2487‐e2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen‐Barak O, Weiss S, Rasamoelisolo M, et al. A phase 1 study to assess the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of fremanezumab doses (225 mg, 675 mg and 900 mg) in Japanese and Caucasian healthy subjects. Cephalalgia. 2018;38:1960‐1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) . The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2013;33:629‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tfelt‐Hansen P, Pascual J, Ramadan N, et al. Guidelines for controlled trials of drugs in migraine: third edition. A guide for investigators. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:6‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache‐related disability. Neurology. 2001;56:S20‐S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mundt JC, Greist JH, Gelenberg AJ, Katzelnick DJ, Jefferson JW, Modell JG. Feasibility and validation of a computer‐automated Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale using interactive voice response technology. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:1224‐1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized individual participant data that underlie the results of this study will be shared with researchers to achieve aims prespecified in a methodologically sound research proposal.