Abstract

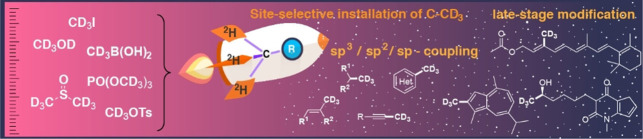

In the field of medicinal chemistry, the precise installation of a trideuteromethyl group is gaining ever‐increasing attention. Site‐selective incorporation of the deuterated “magic methyl” group can provide profound pharmacological benefits and can be considered an important tool for drug optimization and development. This review provides a structured overview, according to trideuteromethylation reagent, of currently established methods for site‐selective trideuteromethylation of carbon atoms. In addition to CD3, the selective introduction of CD2H and CDH2 groups is also considered. For all methods, the corresponding mechanism and scope are discussed whenever reported. As such, this review can be a starting point for synthetic chemists to further advance trideuteromethylation methodologies. At the same time, this review aims to be a guide for medicinal chemists, offering them the available C−CD3 formation strategies for the preparation of new or modified drugs.

Keywords: C−C coupling, C1 building blocks, deuterium, medicinal chemistry, methylation

“3 D” drug development: The deuterated “magic methyl” group is attracting increased interest in pharmaceutical industry. In this review, we discuss the currently available methods for C−CD3 bond forming reactions and classify them according to the trideuteromethylation reagent. The mechanisms, scope and limitations of each method are considered in order to provide a guide for targeted trideutermethylation.

1. Introduction

With around 80 % of the top‐selling drugs containing a methyl group, the importance of site‐selective methylation in medicinal chemistry cannot be overestimated.[1] This is not surprising as methylation is one of the most prevalent and important chemical transformations in biology.[2] For example, just one Me unit distinguishes thymine (DNA) from uracil (RNA). Five amino acids just differ in number and position of methyl units, which ultimately will influence enzyme functionality.[3] Likewise, installation of a methyl unit can be a great tool to profoundly alter and optimize the pharmacological properties of drugs by inducing stereoelectronic and solubility effects.[4] Via stereoelectronic effects, methylation can change or improve the affinity of a compound to a receptor with a minimal change in physical properties of the molecule.[5] As such, methylation can be a strategy to develop more selective and potent drugs.[6] This effect can be dramatic in terms of both changes and improvements in the drug‐bioreceptor interaction. For example, methylation has been demonstrated to change an antagonist into an agonist/allosteric modulator.[7] In the case of improved drug‐bioreceptor interaction, boosts in potency up to 507 fold have been reported.[8] This very large potency increase resulting from a C−H to C−Me transformation is described as the “magic methyl effect”. This so‐called “magic methyl effect” is attributed to “the induction of profound conformational changes leading to low energy conformers that better approximate the bound state”. In addition, the ease of enzymatic metabolization and thus half‐life of the drug can be affected by methylation via stereoelectronics.[9] Apart from these stereoelectronic effects, also the solubility properties change upon methylation as a result of branching, which on its turn can improve the drug availability at the target location. Unlike the popular and sterically analogous CF3 group, the lipophilicity of the molecule does not change much upon methylation, avoiding the formation of too greasy molecules and consequently a violation of the rules of Lipinsky.[10]

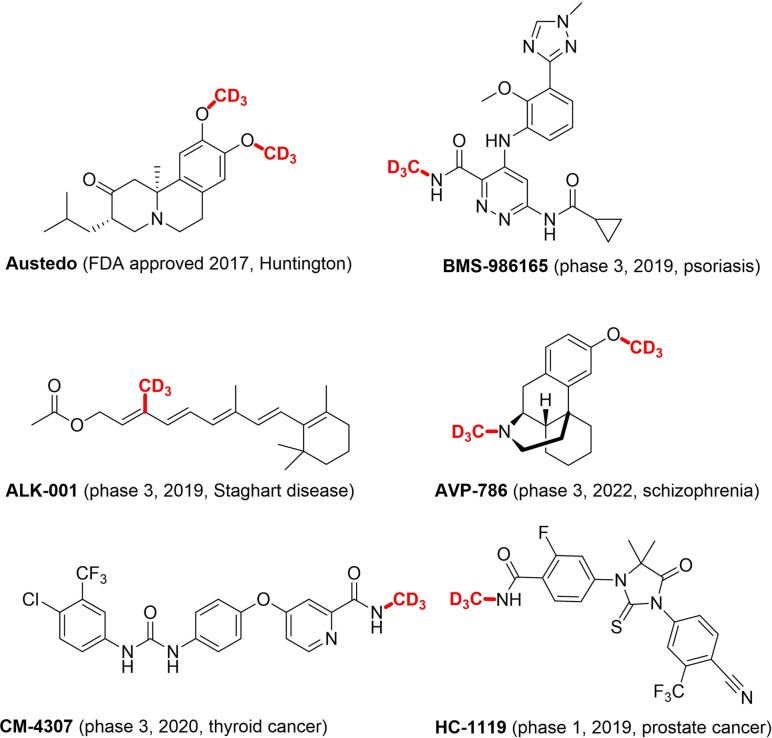

A deeper understanding of these effects, provoked by methylation, on the pharmacology of bioactive compounds is provided by the work of Lovering.[11] Here the increase of saturation and the resulting three dimensionality of a compound (“escape from flatland”) is described to lead to higher clinical success. At the same time, an increase in saturation improves solubility. Not only in drug development but also in peptide chemistry, methylation is adopted as a well‐established strategy to achieve the desired pharmacological properties.[12] When the hydrogen atoms of the methyl group are interchanged for deuterium atoms (the most conventional isosteric replacement) additional benefits in terms of medicinal properties can be obtained. The C−D bond is stronger than the C−H bond due to the kinetic isotope effect, so replacing C−H bonds with C−D bonds can lead to drugs that are less prone to oxidative metabolization and, therefore, longer‐acting.[13] Apart from optimizing the pharmacokinetics, site‐selective deuteration can also lead to reduced toxicity via “metabolic shunting”, increased bio‐activation, stabilization of unstable stereoisomers and even a reduction in drug interactions.[13d] Only recently has there been increased interest in deuterated drugs, mainly due to extra costs and synthetic challenges. In 2017, deutetrabenazine (Austedo) was approved by the FDA as the first deuterated drug (Figure 1). Deutetrabenazine is, in fact, just an improvement of a drug already on the market by so‐called “deuterium switching”. Another strategy is deuterium incorporation during the early stage of drug development.[13d] A very extensive review on deuterated drugs and their applications was published in 2019 by Pirali et al.[13d]

Figure 1.

CD3‐containing approved drug and drug candidates in clinical trials.[13d, 16]

By installing a trideuteromethyl (CD3) group, the mentioned benefits of site‐selective methylation and deuteration can be exploited in one chemical building block. There are currently multiple CD3‐containing drugs in the clinical phase, and deutetrabenazine, the first approved deuterated drug, contains two OCD3 groups (Figure 1).

In the following we discuss currently established methods for site‐selective trideuteromethylation of carbon atoms according to the trideuteromethylation reagents and discuss the corresponding mechanisms and scope of the methodologies.

2. [D4]Methanol

Deuterated methanol is one of the most accessible CD3 sources that also can act as a reagent for C−CD3 bond formation. As a trideuteromethylation reagent CD3OD is especially interesting. It is an inexpensive, relatively low‐toxic trideuteromethylation reagent with high atomic efficiency. Furthermore, CD3OD not only acts as a direct trideuteromethylation reagent but is also the precursor for the preparation of nearly all other trideuteromethylation reagents, including CD3I or CD3OTs.[17]

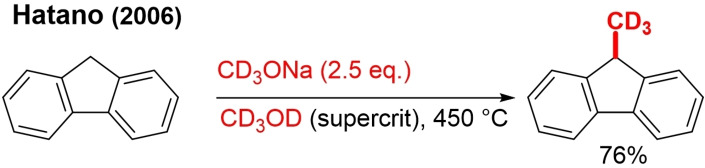

2.1. Transition metal (TM)‐free trideuteromethylation

The direct use of [D4]methanol is hampered by the fact that CD3OD is a weak electrophilic agent for alkylation reactions. Consequently, non‐TM catalyzed reactions are near to nonexistent. Hatano used [D4]methanol in the supercritical state in the presence of an excess of CD3ONa for the introduction of the CD3 group at the 9‐position in fluorene (Scheme 1).[18] The mechanism of this transformation is not fully understood and most likely involves passage through a CD2O intermediate, supposedly formed together with D2O and CD4 through the decomposition of CD3OD.

Scheme 1.

CD3 installation on fluorene with supercritical CD3OD.

Due to the shortcomings of noncatalytic approaches, more efficient methods, such as borrowing hydrogen (BH) strategies using cost‐effective and environmentally friendly iron or manganese‐based catalysts, have recently been developed.

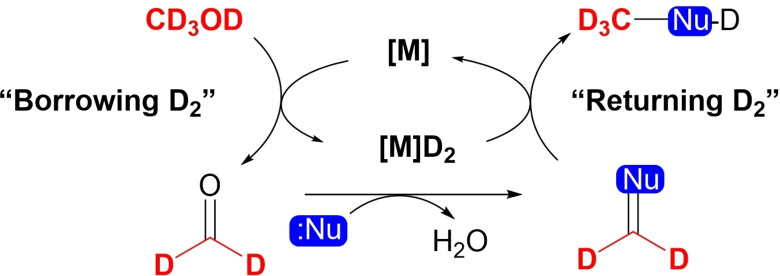

2.2. Trideuteromethylation through Borrowing Hydrogen Catalysis

In the BH methodology (also known as hydrogen autotransfer), the alcohol is subjected to intermediate oxidation by a catalyst (“borrows” hydrogen from the substrate), to the corresponding aldehyde (Scheme 2). The formed aldehyde subsequently reacts with the nucleophilic component. At the end of the cycle, the adduct is hydrogenated by a catalytic complex, and an alkylated product is formed. An overview of BH catalysis and the use of methanol as a C1 source can be found in publications of Corma and Jagadeesh.[19]

Scheme 2.

Schematic of the borrowing hydrogen process with [D4]methanol.

The BH methodology is a very useful transformation; however, it should be noted that this direct methylation with methanol is not devoid of internal problems due to the high stability of methanol against dehydrogenation leading to the use of high temperatures and strong bases, and the formation of unstable intermediates.

2.2.1. α‐Trideuteromethylation of enolates

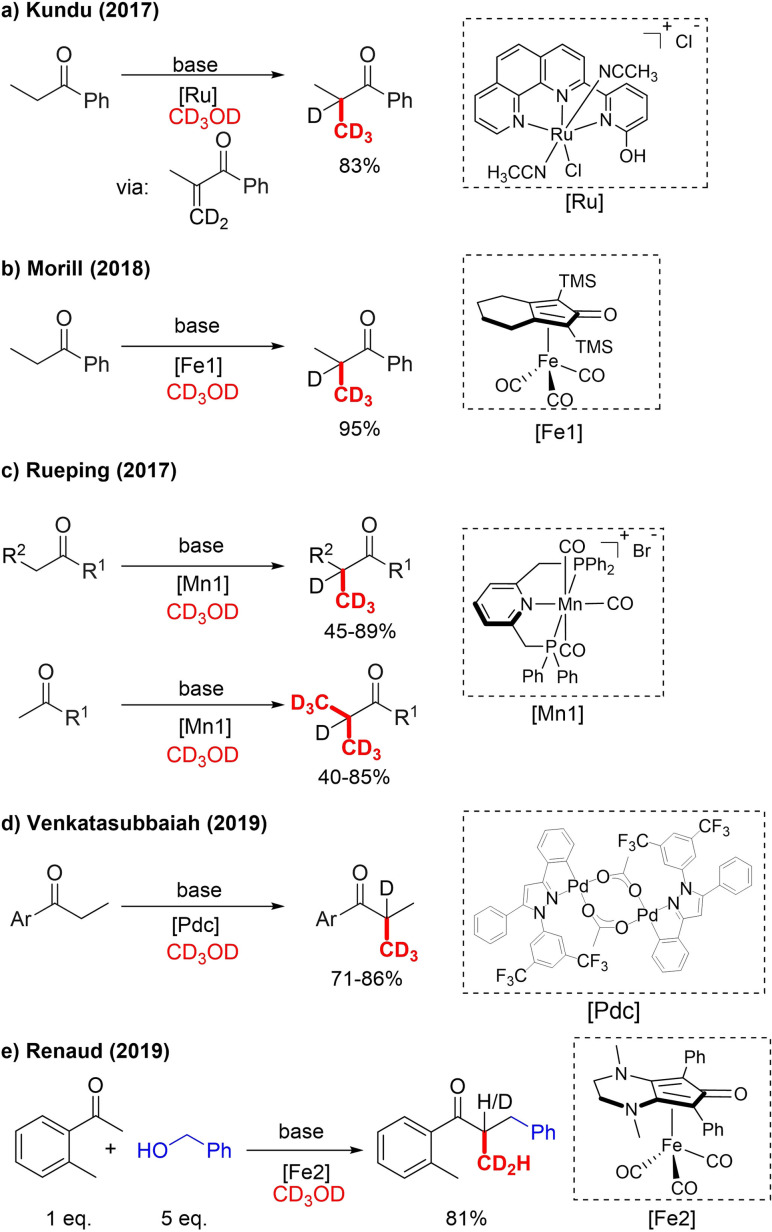

For α‐trideuteromethylation via BH catalysis, propiophenone has been used as a test substrate by many research groups. Kundu et al. was the first to report α‐trideuteromethylated methyl ketones. Using a moisture‐ and air‐stable Ru‐catalyst, α‐CD3‐alkylated propriophenone was obtained in 83 % yield (Scheme 3a).[20] Mechanistic studies and DFT calculations suggest an enone intermediate. Aside from using an expensive ruthenium catalyst, this first variant of BH‐trideuteromethylation required a large excess of the base KOtBu (4 equiv.). In 2018 Morrill et al. used a Knölker‐type iron precatalyst activated with trimethylamine N‐oxide for the C‐methylation of ketones.[21] This led to an improvement over the work of Kundu, and an excellent yield of 95 % was obtained (Scheme 3b). With methanol, oxindoles and indoles also underwent BH methylation under the same conditions. As in the report of the Kundu reaction conditions, the probable enone intermediate was also tested, delivering a CH2D‐methylated product in 74 % yield.

Scheme 3.

α‐Trideuteromethylation of ketones with CD3OD. a) KOtBu (4 equiv.), 85 °C, 24 h; b) Me3NO (0.04 equiv.), NaOH (2 equiv.), 80 °C, 24 h; c) Cs2CO3 (4 equiv.), 105 °C, 24 h; d) PCy3, LiOtBu (0.3 eq), 130 °C, 48 h e) KOH (0.1 equiv.), K3PO4 (2 equiv.), 90 °C, 24 h.

The Knölker iron catalyst is well known for its transfer hydrogenation ability and has low toxicity and a rather low price compared to precious metal catalysts. In fact, the search for non‐noble earth‐abundant hydrogen atom transfer catalysts is currently a very active field. From that perspective, Rueping and co‐workers realized further progress by developing a selective C1‐methylation process using an air‐ and moisture‐stable MnI pincer complex.[22]

Manganese is the third most common transition metal in the Earth's crust, and the area of manganese catalyst research is currently developing rapidly. Various substituted ketone derivatives, as well as cyclic, (hetero)aromatic and aliphatic ketones, formed α‐methylated products with good to excellent yields. In the case of acetophenone derivatives, di‐trideuteromethylation took place (Scheme 3c).[23] It was also demonstrated that when using CD3OH, concomitant deuteration of the α‐position can be avoided. In 2019, Venkatasubbaiah reported selective [D3]methylation of propriophenone derivatives (Scheme 3d). However, their method relies on an expensive palladacycle and does not deliver additional benefits compared to the mentioned Fe and Mn catalytic systems. Renaud went a step further and applied this BH strategy in a tandem three‐component reaction catalyzed by a Knölker‐type iron catalyst for the preparation of α‐branched methylated ketones from methanol, benzyl alcohol and a ketone substrate.[25] When CD3OD was used instead of MeOH, an α‐CD2H‐labeled ketone was obtained, indicating that benzyl alcohol acted as a hydrogen source (Scheme 3e). All previously discussed methods are limited to ketone substrates.

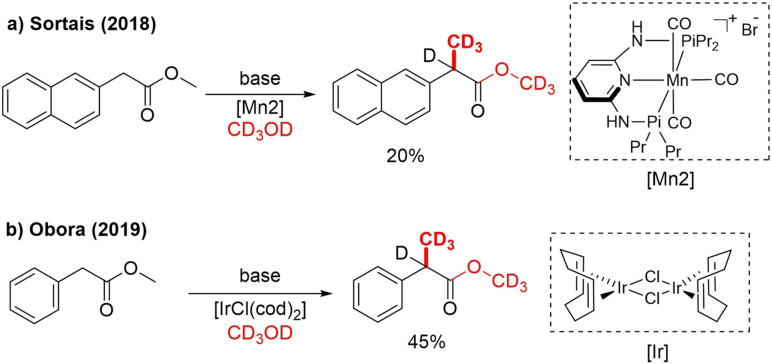

In 2018, Sortais reported for the first time α‐trideuteromethylation of an ester, although in low yield (20 %), with a similar MnI pincer‐catalyst as the Rueping group (Scheme 4a). The same catalyst also achieved [D3]methylation of 1,3‐diphenylpropan‐1‐one in high yield (82 %).[26] Furthermore, Obora in 2019 reported α‐methylation of aryl esters by utilizing an [IrCl(cod)2]/dppe‐catalyzed process. One trideuteromethylated example obtained in 45 % yield is shown (Scheme 4b).[27] It should, however, be noted that for both methods, ester OMe‐to‐OCD3 exchange took place in addition to α‐trideuteromethylation.

Scheme 4.

α‐Trideuteromethylation of esters with CD3OD. a) NaOtBu (1 equiv.), toluene, 120 °C, 20 h; b) dppe, KOtBu (0.7 equiv.), 150° C, 48 h.

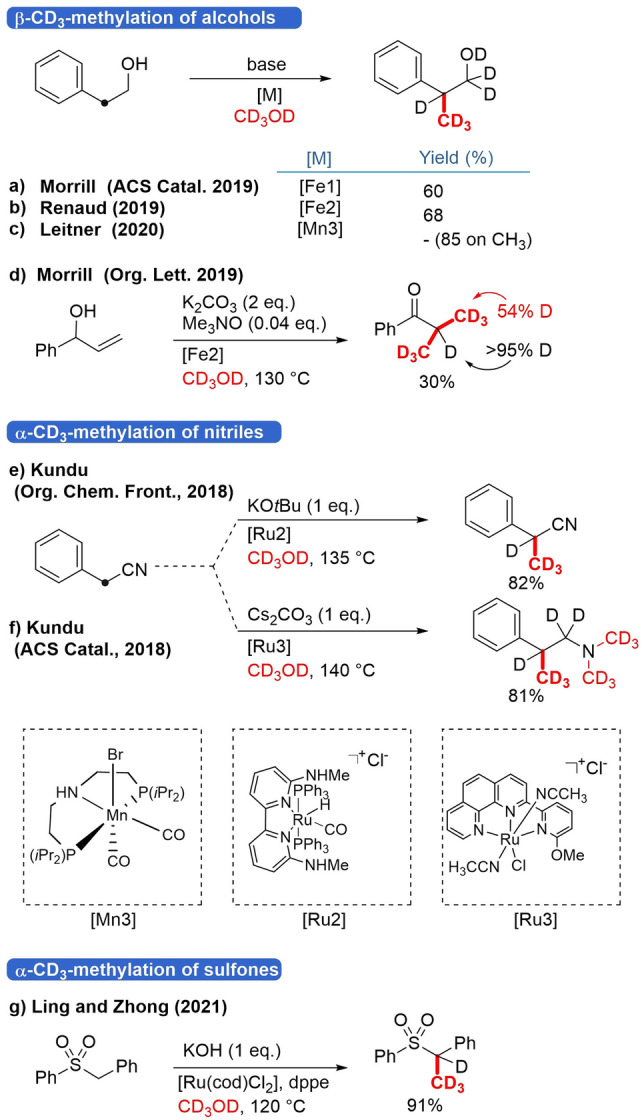

2.2.2. Trideuteromethylation of alcohols and nitriles

Based on the progress made in carbonyl α‐methylation, there has been rapid progress in β‐methylation of alcohols (crossed aldol reaction). The groups of Morrill[28] and Renaud[29] reported the selective β‐methylation of substituted aryl alcohols in the presence of diaminocyclopentadienone iron tricarbonyl complex (Scheme 5a, b). The complex showed good reactivity towards the selective β‐methylation of substituted 2‐arylethanol derivatives. To further demonstrate the usefulness of the Fe‐catalyzed procedure, the Morrill group showed that the process may be extended to allyl alcohols, resulting in products with moderate to excellent yields (Scheme 7d, below).[30] During methylation with CD3OD there was near complete incorporation of deuterium at the α‐ and for 54 % at β‐position. This percentage of 54 % can be understood when an iron hydride, formed by dehydrogenation of allyl alcohol or methanol, is involved in the mechanism. Leitner et al. recently demonstrated β‐methylation of alcohols employing highly effective air‐stable molecular manganese complex that requires only low loadings (0.5 mol%; Scheme 5c).[31] A [D3]methylation experiment was conducted, but no yield was reported; however, methylated products under the same reaction conditions were obtained in 85 % yield.

Scheme 5.

C[D3]methylation of alcohols and nitriles. Reaction conditions: a) Me3NO (0.1 equiv.), NaOH (2 equiv.), 130 °C, 24 h; b) NaOH (0.1 equiv.), NaOtBu (1 eq.), tBuOH, 110 °C, 40 h; c) NaOtBu (3 equiv.), 150 °C, 24 h.

Scheme 7.

D3 methylation of quinolines with CD3OD.

Alkylation of the nitriles is a well‐studied topic in BH‐methodology, owing to the pioneering work of Grigg and co‐workers.[32] The deuteromethylation on 2‐phenylpropanenitrile was demonstrated by the Kundu group and relied on Ru complexes (Scheme 5e).[33] Interestingly, a transition from bipyridine‐type ligand to phen‐py‐OMe and Cs2CO3 as a base instead of KOtBu resulted in tandem C‐methylation as well as N‐methylation. In this manner, a D12 compound was obtained in one step in 81 % yield (Scheme 5f).[34]

2.2.3. Borrowing Hydrogen catalytic trideuteromethylation of aromatic substrates

Following the pioneering work of Grigg and co‐workers, who first reported the BH strategy, Cai and his colleagues reported a simple and straightforward methylation approach in the synthesis of biologically important alkylated indoles and pyrroles with cyclopentadienyl iridium catalyst (Scheme 6a).[36] [D3]methylation of indole delivered [D3]skatole, which is widely used to study metabolic kinetics, in 81 % yield.[37] Although noble metal catalysts such as Ir and Ru are well known to be effective for the BH alkylation, they have limitations due to the price, toxicity and difficulty of recovery. To address this issue, Morrill entered the topic of indole alkylation and suggested an inexpensive and benign Knölker‐type (cyclopentadienone)iron carbonyl complex precatalyst [Fe1] (Scheme 3), activated with trimethylamine N‐oxide for the C‐methylation of a broad range of substrates, including indole. With the new catalyst, the same indole C2‐trideuteromethylation occurred with a yield of 67 % (Scheme 6b).[21]

Scheme 6.

[D3]methylation of indole and naphthalen‐2‐ol by BH‐strategy.

In another study related to trideuteromethylation of aromatic substrates, Hong and Kim in 2017 have demonstrated ortho‐aminomethylation and methylation of electron‐rich phenols with in situ generated (iPr)‐RuH2(CO)(PPh3)2. A reaction of [D4]methanol with 2‐naphthol, during mechanistic studies, resulted in the formation of CD3‐labeled product in 88 % yield (Scheme 6c).[38] Although the direct introduction of the CD3 group on the aromatic ring via CH functionalization with CD3OD would be of high value for drug development, it has unfortunately not yet been developed further.

2.3. Trideuteromethylation of quinolines

In 2017 a study on the use of methanol as an alkylating reagent of electron‐deficient heteroarenes was published by Li and co‐workers.[39] The room‐temperature UV‐mediated reaction under air did not require an external photosensitizer or TM catalyst. Their strategy was based on the photochemical generation of a hydroxymethyl radical in a mixture of CH2Cl2/MeOH. CH2Cl2 significantly increased the yield as it promoted hydroxymethyl radical generation, the rate‐limiting step. Three different routes are proposed for the generation of hydroxymethyl radicals: via electron transfer to the protonated substrate, via a chlorine radical generated from CH2Cl2, or by electron transfer between CD3OD and CH2Cl2 (Scheme 9a, below). Trifluoroacetic acid was used for the protonation of substrates. This protonated substrate is subsequently attacked by the nucleophilic radical. The formed cationic radical is in resonance with an enamine radical that, upon loss of water, forms a diene cationic radical intermediate that undergoes an electron transfer with CD3OD. In the final step, tautomerization affords the end product (Scheme 7a).

Scheme 9.

Pd‐catalyzed ortho C−H trideuteromethylation with CD3I.

Not only quinoline but also benzothiazole, purine and nicotinic acid derivatives underwent site‐selective methylation under the same reaction conditions. Slightly changing reaction conditions also afforded methylated isoquinoline and pyridine derivatives. Trideuteromethylation was only demonstrated for one quinoline substrate. When using CD3OH instead of CD3OD in CH2Cl2 the CD2H labeled product was delivered (Scheme 7a). Similarly, Barriault in 2017 described a photochemical alkylation of quinolines, pyridines, and phenanthridines using UVA LED light under argon atmosphere.[40] Instead of TFA, HCl is used as acid and no CH2Cl2 was added. In the case of DCl in D2O and [D4]methanol as a solvent, the CD3‐product was obtained in 77 % yield (Scheme 7b). By combining the appropriate solvents and acid also CD2H and CDH2 labeling could be achieved. The presented mechanism is very similar to the mechanism of Li, starting with hydroxymethyl radical generation. In 2020, the same group used a catalytic system based on an iridium photocatalyst, DCE as the solvent and blue instead of UVA light, which gave a lower yield of 21 % instead of 73 %.[41] The main difference is that for this protocol, hydroxymethyl radical generation occurs through chlorine radical formation by the excited photocatalyst.

3. CD3I and Its Organometallic Derivatives Prepared in Situ

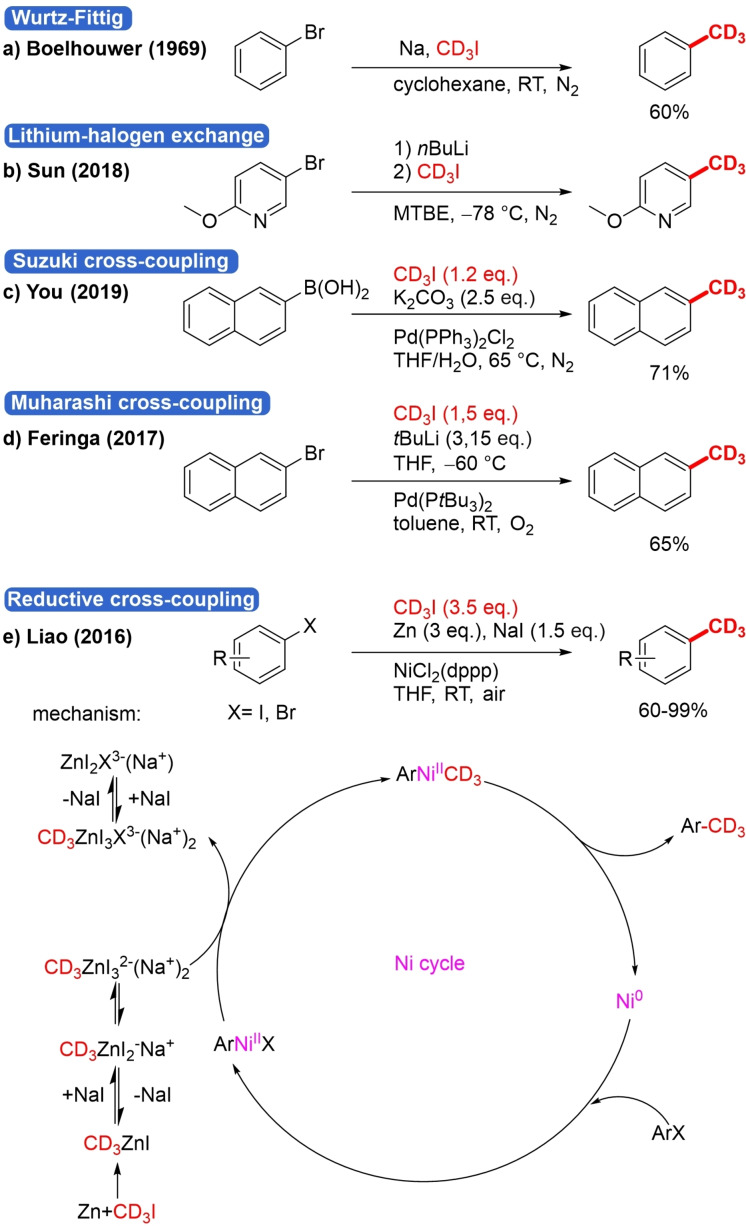

Analogous to methyl iodide, CD3I is one of the main trideuteromethylation reagents.[42] Because iodide is a good leaving group, it is especially suitable for nucleophilic substitution reactions, and the weak C−I bond makes it very prone to oxidative insertion of a transition‐metal catalyst. Reported in 1969, trideuteromethylation of aryl bromides with CD3I was achieved via the Wurtz‐Fittig reaction, which relies on the use of very reactive sodium (Scheme 8a).[43] Later, the standard approach for trideuteromethylation of (hetero)aryl halides was lithium‐halogen exchange at −78 °C, followed by trapping the CD3I electrophile (Scheme 8b).[44] This strategy was also applied for trideuteromethylation of alkyl bromides, bromoalkenes and terminal alkynes.[45] This approach, however, has numerous drawbacks. The use of cryogenic temperatures and reactive organolithium reagents, which are dangerous to handle, makes this method unfit for adoption on an industrial scale. Additionally, the reactive organolithium reagent is not compatible with electrophilic substituents on the (hetero)aryl moiety.

Scheme 8.

Different routes for aryl halide trideuteromethylation with CD3I.

A way to avoid these harsh conditions is direct trideuteromethylation of (hetero)aryl halides with CD3 organometallic reagents by TM‐catalyzed C(sp3)‐C(sp2) cross‐coupling. There are a few reports on cross‐coupling with the corresponding CD3 organometallic reagent.[46] Most noteworthy is the very fast room temperature trideuteromethylation, reported by Feringa in 2017, of bromonaphthalene by a palladium nanoparticle catalyzed Muharashi cross‐coupling under air with CD3Li generated in situ from CD3I (Scheme 8d).[46b] For the Suzuki‐Miyaura reaction there are also some examples where the arene organometallic nucleophile reacts with CD3I as an electrophile (Scheme 8c).[47] This TM‐catalyzed cross‐coupling approach, however, still suffers from some drawbacks such as the required prefunctionalization to form a nucleophilic organometal, which adds at least one reaction step and generates metallic waste. Additionally, the nucleophilic nature of the CD3‐organometal still limits the number of compatible functional groups. Reductive coupling is a strategy to circumvent these drawbacks. In 2016 Liao et al. published a Ni‐catalyzed reductive coupling of ArX (X=I, Br) and CD3I (3.5 eq.) using Zn as a reductant (Scheme 8e).[48] Both electron‐donating and electron‐withdrawing substituents were tolerated as well as heteroaryl iodides and a vinyl group‐containing substrate. Two mechanisms were proposed. One involves a free‐radical chain process and the other a transmetalation before reductive elimination (RE) of the product, a mechanism very similar to Lipshutz‐Negishi cross‐coupling.[49]

Mechanistic studies have indicated a small preference for the latter mechanism (Scheme 8e). In the first step, oxidative insertion in ArX by Ni0 occurs, and the formed ArNiIIX species undergoes TM with a CD3ZnI3 2−(Na+)2 species. Via RE the product is formed and Ni0 regenerated. Additionally, Osaka prepared trideuteromethylated arenes by cross‐electrophile coupling but with CD3OTs as an electrophilic trideuteromethyl source (Scheme 21, below).[50]

Scheme 21.

Trideuteromethylation of active methylenes with a [D6]DMSO‐derived reagent prepared by sulfoxonium metathesis (one pot).

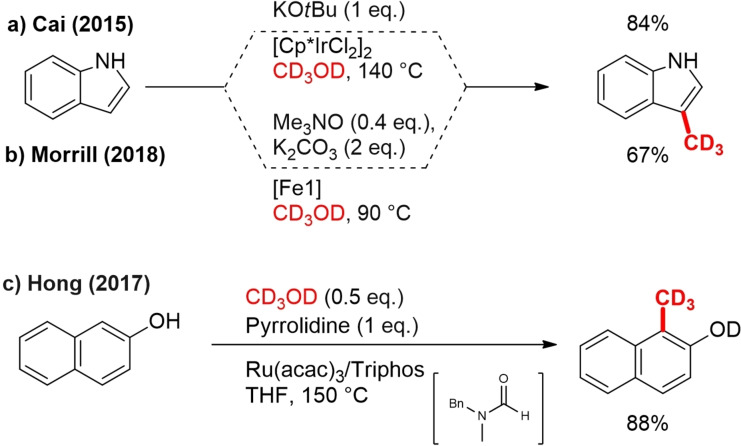

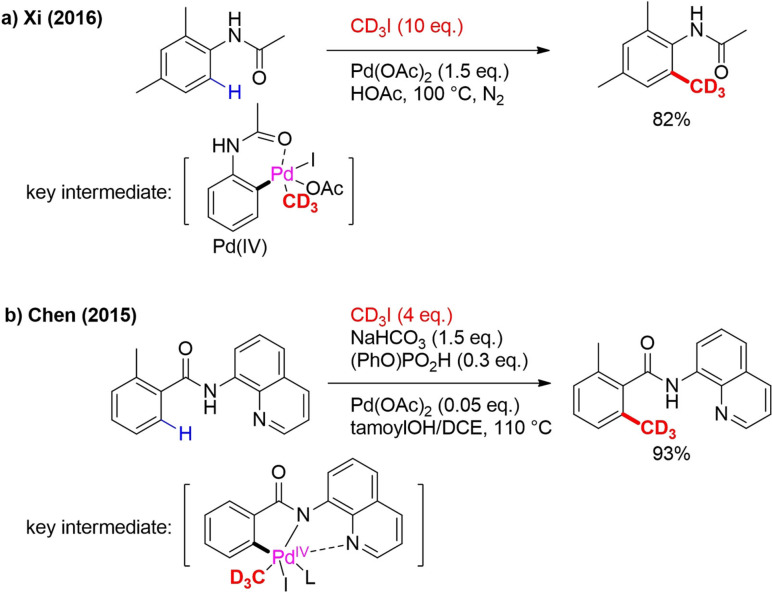

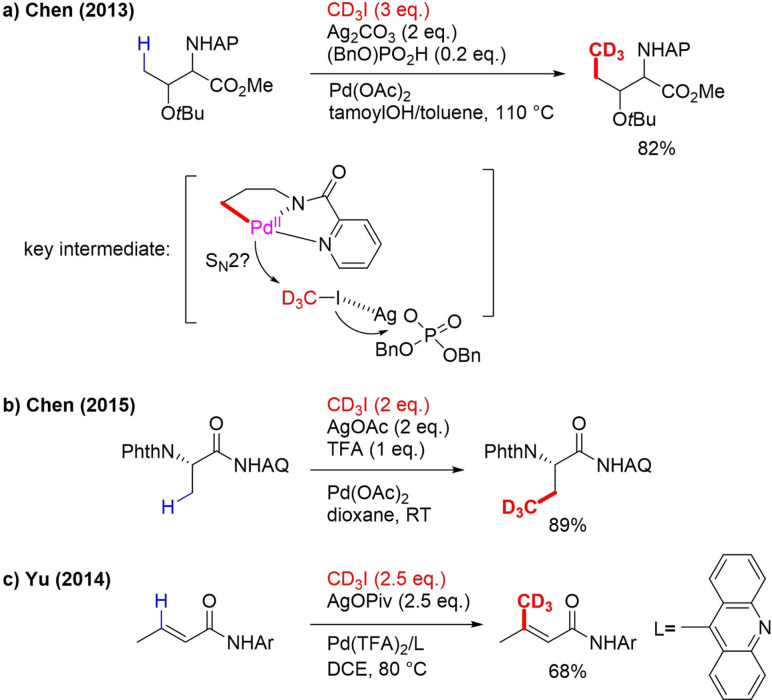

CD3I has also been applied as a reagent in the C−H trideuteromethylation of arenes, a very useful transformation from an atom and a step‐economy point of view. A classical strategy is ortho‐lithiation with nBuLi followed by trapping with CD3I.[51] The scope of this approach is very limited due to the use of very reactive organolithium; milder conditions are needed. In 2016, ortho C−H trideuteromethylation of acetanilide was achieved based on a method developed in 1984 by Tremont (Scheme 9a).[52] Stoichiometric use of Pd(OAc)2, forming ortho‐palladate acetanilide, is a prerequisite. This ortho‐palladate undergoes RE leading to product formation (Scheme 9a).

The right choice of solvent system allows selective mono‐ or di‐methylation. In 2015, Chen reported Pd‐catalyzed C−H ortho alkylation of quinolyl benzamides with primary and secondary alkyl iodides (Scheme 9b).[53]

One example is trideuteromethylation with CD3I. The reaction was promoted by NaHCO3 and organic phosphates. The amount of NaHCO3 could be varied to achieve selective mono‐ or dialkylation. A broad scope of benzamides undergoes this reaction but the yields of electron‐deficient benzamides are significantly lower. There are also examples with a thiophene and an indole ring instead of benzene. Mechanistically, a PdII/PdIV cycle undergoes carbopalladation as first step, followed by OA of CD3I and RE (Scheme 9b). In the last step, dissociation of the PdII catalyst occurs. The 8‐aminoquinoline auxiliary group can easily be removed to form an ester after trideuteromethylation. It was also demonstrated that C−H alkylation still occurs with 5‐methoxy‐8‐aminoquinoline as auxiliary group which can then be easily transformed into a primary amide.

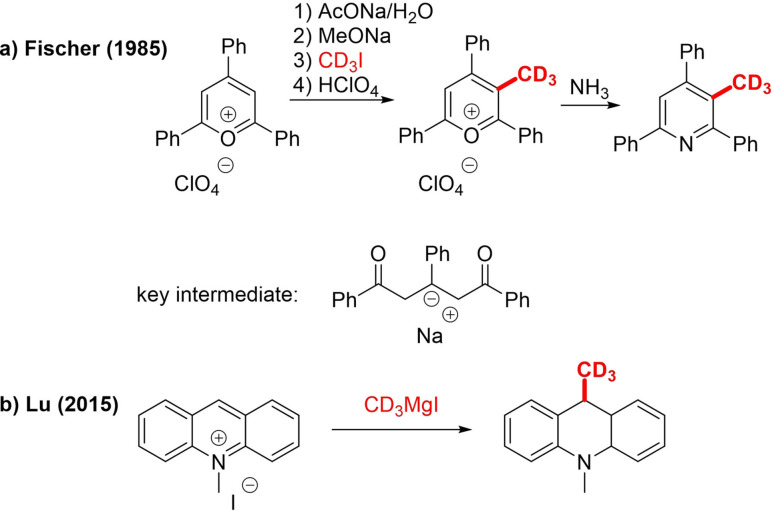

Fischer reported a very specific case of C−H trideuteromethylation, not relying on ortho‐lithiation or an auxiliary group, where triarylpyrylium salt is converted to CD3 triarylpyridine via a 1,3,5‐triarylpentene‐1,5‐dione enolate (Scheme 10a).[54] Similarly, Lu trideuteromethylated an aromatic methylacridinium salt using CD3MgI, in situ prepared from CD3I, forming 9‐C[D3]methylacridan (Scheme 10b).[55]

Scheme 10.

C−H trideuteromethylation of aromatic salts.

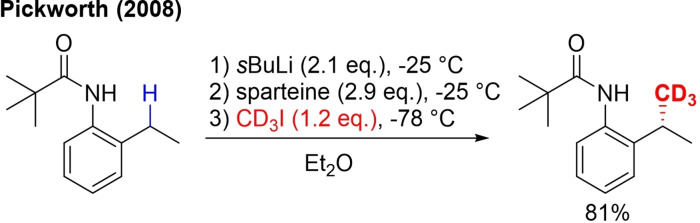

In addition to the TM‐catalyzed C(sp2)‐H trideuteromethylation of aryl groups, the even more challenging TM‐catalyzed C(sp3)‐H trideuteromethylation with CD3I has been reported. The most straightforward and a classical TM‐free approach involves generating a stabilized carbanion that is then trapped by the electrophilic CD3I. As a consequence, this strategy is limited to carbon atoms, which can generate a stable carbanion, and as mostly a strong base is needed, the compatibility with other functional groups is limited. Examples of CD3‐labeling at the α‐position of carbonyl, sulfonyl and nitrile groups and the position 2 of 1,3‐dithianes have been reported.[56] The benzyl position is another accessible position for stable carbanion generation to achieve C(sp3)‐H trideuteromethylation. An enantioselective CD3‐labeled isopropyl aniline derivative was prepared via lithiation and use of sparteine (Scheme 11).[57]

Scheme 11.

Enantioselective TM‐free C(sp3)‐H trideuteromethylations with CD3I.

In 2013, Chen described a Pd‐catalyzed method for γ‐C(sp3)‐H alkylation of picolinamide (PA) protected aliphatic amines with primary alkyl iodides.[58] Ag2CO3 and dibenzyl phosphate were critical promotors of the reaction. The article presents one example of trideuteromethylation (Scheme 12a).

Scheme 12.

Pd‐catalyzed C(sp3)‐H/ C(sp2)‐H trideuteromethylations with CD3I.

Various protected amino acids were selectively alkylated. PA‐protected 3‐pentylamine containing two equivalent γ‐Me groups could be sequentially alkylated. In the case of benzylamine and β‐arylethylamine derivatives, δ‐C(sp2)‐H alkylation was observed. It was also shown that with a more easily removable PA auxiliary group, methylation still occurred. Analogous to the related ortho C−H trideuteromethylation method developed by the same group (Scheme 9b, above) a PdII/PdIV cycle is proposed as the mechanism. Dibenzyl phosphate is thought to function as a phase‐transfer catalyst and slow addition of Ag+ to the solution resulted in the activation of iodides. An OA of CD3I is then proposed via SN2 mechanism (Scheme 12a) and finally RE.

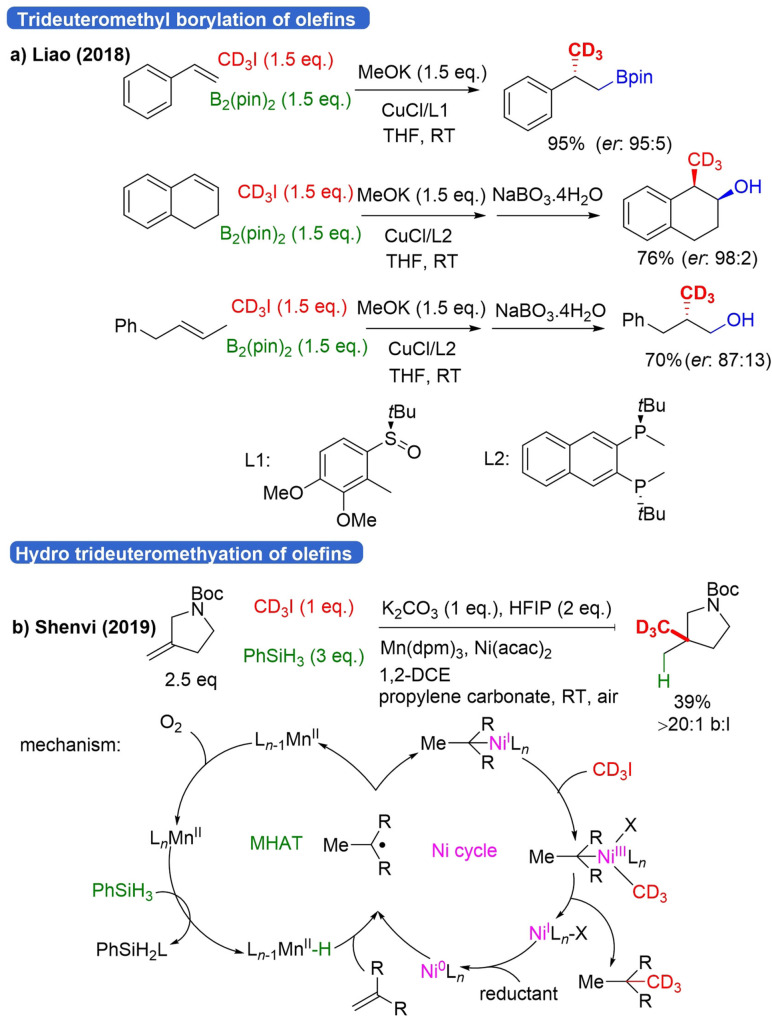

Two years later, the same group developed a strategy for β‐C(sp3)‐H mono alkylation of aminoquinoline(AQ)‐coupled phthaloyl‐L‐alanine with primary alkyl iodides.[59] One trideuteromethylation example is shown (Scheme 12b). In the next step, the auxiliary group can be converted to a carboxylic acid, leading to a β‐CD3 amino acid. No mechanistic details were provided. Apart from C(sp3)‐H activation also Pd‐catalyzed vinylic C(sp3)‐H trideuteromethylation has been reported. The group of Yu discovered that simple amides can be trideuteromethylated at the vinyl position via Pd‐catalyzed C−H functionalization.[60] The use of 9‐methylacridin as a ligand for Pd proved to be crucial. Their method is also applicable for the C(sp3)‐H and aromatic C(sp2)‐H methylation of amides, but no trideuteromethyl examples were shown. More recently, two procedures on the trideuteromethyl functionalization of olefins with CD3I were reported. Liao reported the enantioselective (trideutero)methyl borylation of alkenes by a copper catalyst containing a chiral phosphine ligand in a three‐component reaction (Scheme 13a).[61]

Scheme 13.

Trideuteromethyl functionalization of alkenes with CD3I.

A broad range of styrenes containing different functional groups at different positions underwent the reaction to give anti‐Markovnikov products. However, for p‐CF3, p‐CN, meta‐Cl and meta‐Br substituted styrenes, the enantioselectivity was poor. Switching to another chiral phosphine ligand, β‐substituted styrenes and aliphatic olefins underwent the reaction as well to form syn‐addition products. Scalability and late‐stage modification were also demonstrated but no mechanistic description was given. Shenvi published a method in 2019 for Markovnikov hydroalkylation of unactivated olefins with unactivated alkyl halides.[62] This transformation allows for the preparation of quaternary C−CD3 and relies on Mn/Ni dual catalysis. One example is shown with CD3I as an alkyl halide (Scheme 13b). A whole range of alkenes containing different functional groups is tolerated. Additionally, heteroatoms on the alkene were compatible. Tri‐ and tetrasubstituted alkenes give higher branched to linear ratios. The reaction was even demonstrated for different natural product scaffolds. As a mechanism, the generation of a tertiary radical from the alkene via Mn mediated metal‐hydride hydrogen atom transfer (MHAT) was proposed (Scheme 13b). This radical is then intercepted by a low‐valence Ni catalyst that delivers the product by RE after OA of the alkyl halide. Notably, Baran also achieved hydro‐trideuteromethylation. His method, however, relies on a two‐step process via a hydrazone intermediate, and instead of CD3I, the system CD3OD/CD2O is used (Scheme 27c, below).[63]

Scheme 27.

Noncryogenic route towards 5‐CD3 pirfenidone.

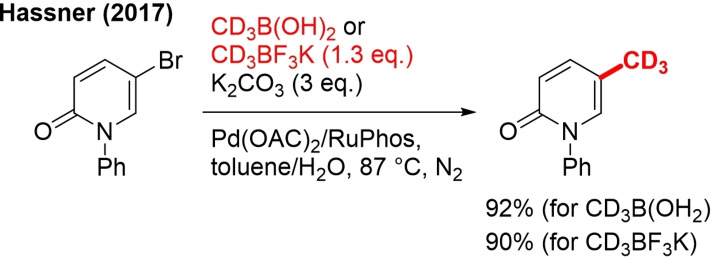

CD3I and it's in situ prepared derivative like CD3MgI have been employed in many reduction reactions. Under Birch reduction conditions, CD3I facilitated reductive trideuteromethylation of benzonitriles, 3,5‐dimethylbenzoic acids, α,β‐epoxyketones and α,β‐unsaturated ketones (Scheme 14).[64]

Scheme 14.

Reductive trideuteromethylation with CD3I under Birch conditions.

Numerous examples for the reduction of the carbonyl group in ketones, aldehydes and esters with CD3MgI/CD3MgBr Grignard reagent prepared in situ can be found.[65] Additionally, the reduction of an acid chloride, to only a CD3‐labeled ketone, with CD3CdCl prepared from CD3MgI and CdCl2 is described.[66] Other classical reactions for Grignard reagents, namely, the ring‐opening of epoxides and 1,4 addition, involving CD3MgI are described in the literature as well.[67] In transition metal‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions, CD3MgI reacts as a nucleophile with ArX (X=Cl, Br,I), primary RI, benzyl ether and enol ether electrophiles.[68] In copper‐catalyzed displacement reaction O‐TBS ether, O‐Benzyl and O−Ts groups can be substituted for a trideuteromethyl group with CD3MgI.[69] Additionally, less classical Grignard involved reactions, such as substitutions of carbon ether and stereoselective conversion of cyclopropane carbinols to alkylidene cyclopropanes, CD3 labeled examples are published.[70] In two steps, the cuprate (CD3)2CuLi can be in situ prepared from CD3I.[71] Using CD2HI, also (CDH2)2CuLi can be generated for CDH2 labeling. (CD3)2CuLi can act as a trideuteromethyl source that is a softer nucleophile than CD3MgI and CD3Li. Classical reactions of cuprates, such as acid chloride‐to‐ketone conversion, 1,4‐addition and substitution of OTs and phosphate groups, were also performed with (CD3)2CuLi.[72] Less known reactions, such as Pd‐catalyzed cross‐coupling with iodostyrene derivatives and conversion of acetylenic ketones to CD3‐substituted allene, have also been reported.[71, 73]

Although CD3I is used for a very broad range of trideuteromethylation, it has the disadvantages of being an expensive, toxic, volatile and corrosive reagent.[74]

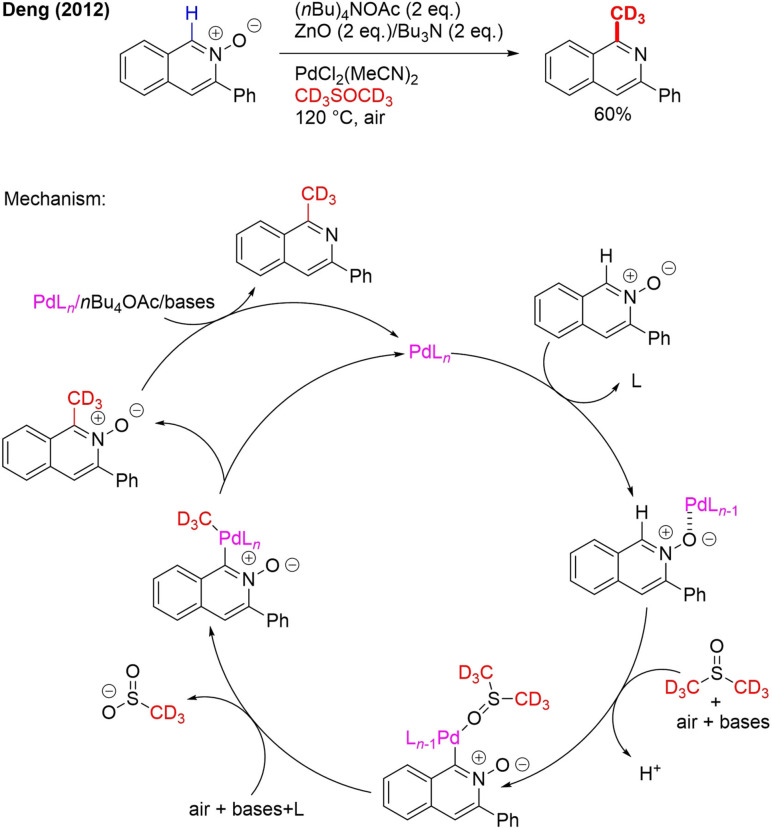

4. [D6]DMSO

In contrast to CD3I, [D6]DMSO is a cheap, nontoxic and widely available solvent making it a particularly interesting reagent for the production of CD3‐labeled drugs. In 2012, the first publication on carbon trideuteromethylation with [D6]DMSO appeared. Isoquinoline N‐oxides were converted into 1‐CD3–isoquinolines by palladium‐catalyzed C−H oxidation (Scheme 15).[75] The N‐oxide group functions as a directing group that is removed during the reaction.

Scheme 15.

Pd‐catalyzed conversion of isoquinoline N‐oxides to 1‐CD3‐isoquinolines in [D6]DMSO.

According to the proposed mechanism, PdLn initially coordinates with the oxygen of the N‐oxide, activating the C−H bond next to it (Scheme 15). This leads to oxidation–carbopalladation of the C−H bond and complexation of [D6]DMSO with the palladium catalyst. Base and air‐assisted oxidative cleavage of the C−S bond followed by CD3 insertion is the next step. Upon RE, trideuteromethylated isoquinoline N‐oxide is formed. This N‐oxide will then be removed with the aid of PdLn/(nBu)4OAc (phase‐transfer catalyst)/base.

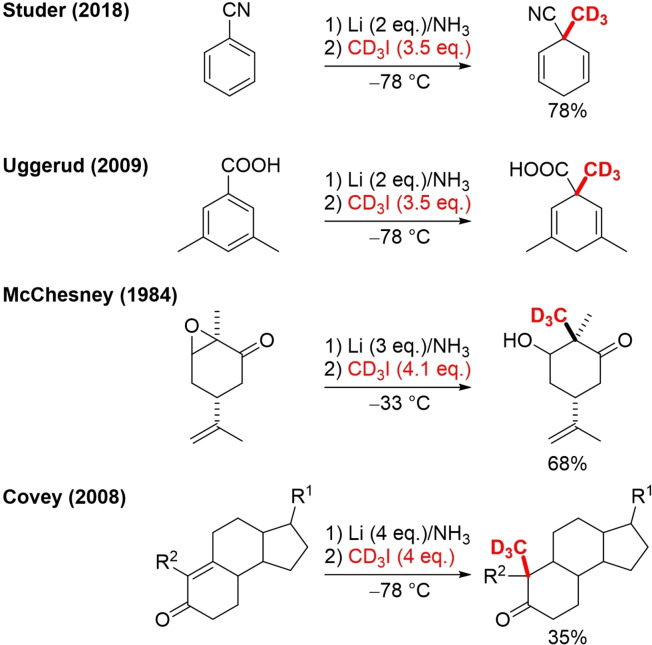

In recent years, multiple strategies were developed for CD3 installation using a trideuteromethyl radical derived from [D6]DMSO. In 2016, Antonchick reported radical trideuteromethylation of isoquinoline in [D6]DMSO using FeCl2, hydrogen peroxide and TFA. As the trideuteromethyl radical has nucleophilic character, the attack occurs on the most electron‐poor position. As a consequence, no directing group was required, as in the previous described method. The method was applied to many scaffolds (Scheme 16).[76] Apart from trideuteromethylation of different isoquinoline derivatives with electron‐withdrawing and electron‐donating substituents, the method could also be applied to transforming a broad range of N‐methyl‐N‐aryl‐methacrylamides to trideuteromethylated oxindole derivates. This occurs by nucleophilic attack of the alkene, followed by cyclization and rearomatization. Various acrylamides were converted into CD3‐containing α‐haloamides. Even an α‐aryl‐β‐trideuteromethyl amide containing a quaternary carbon center could be obtained from N‐(arylsulfonyl)acrylamide in a tandem process (Scheme 16).

Scheme 16.

Radical TM‐catalyzed trideuteromethylation on different scaffolds and the proposed mechanism for CD3 radical generation from [D6]DMSO.

The generation of the CD3 radical is presented as a three‐step process (Scheme 16), starting with the reaction between Fe2+ and H2O2 Equation (1), also called the Fenton reaction.[77] As a result of this reaction, a hydroxyl radical is formed together with Fe3+ and OH− Equation (2). This OH radical will attack [D6]DMSO, and the newly formed radical will fragment to a CD3 radical and CD3SOOH Equation (3).

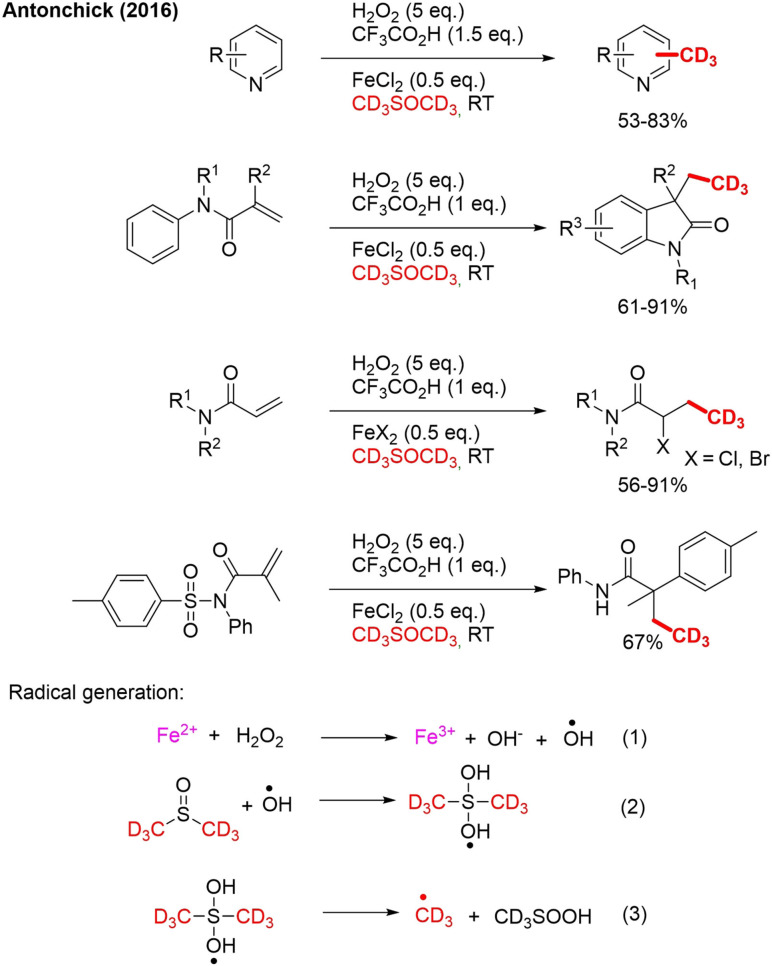

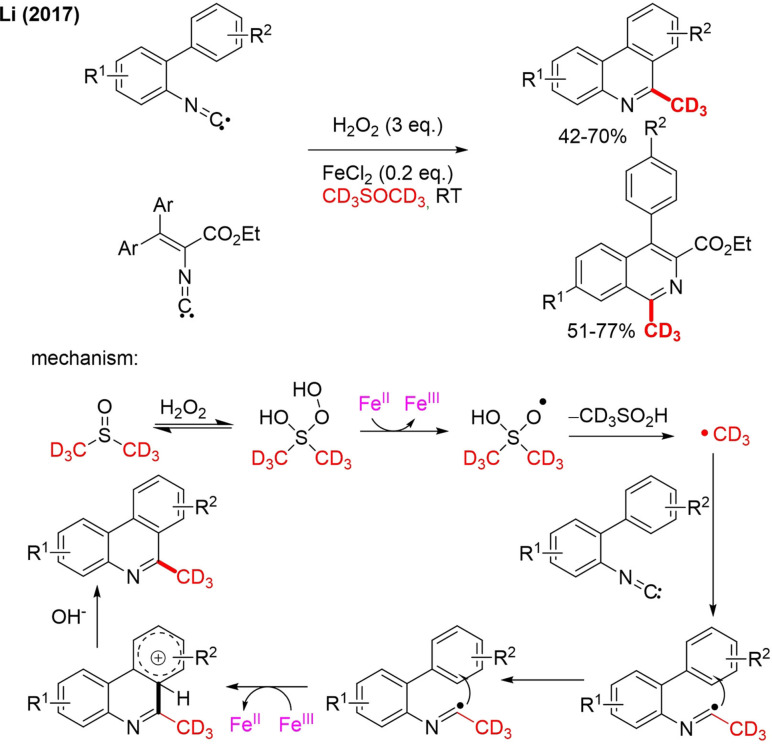

The Wang group also achieved the transformation of methyl‐N‐aryl‐methacrylamides to trideuteromethylated oxindole derivates with [D6]DMSO. Unlike Antonchick, they performed the reaction under visible‐light promoted conditions, and no TFA was required.[78] The exact role of light is unclear. Previous research proposes a double role: to photoreduce Fe3+ and regenerate Fe2+ and to increase hydroxyl radical generation. Li developed the method further. Using inert conditions, biphenylisocyanides derivatives were converted into CD3‐labeled phenanthridines and isoquinolines, which are medicinal relevant building blocks, by radical cascade cyclization (Scheme 17).[80] A wide variety of substituents were tolerated but not the strongly withdrawing nitrile and nitro functional groups. The mechanism presented for CD3 radical formation is somewhat different as in the work of Antonchick (Scheme 17) and preceding literature reports.[81] Here, hydrogen peroxide attacks [D6]DMSO via nucleophilic addition, and the formed adduct is subsequently reduced by FeII. The radical adduct fragmentates to the CD3 radical, which attacks the isocyanide. Radical cyclization followed by deprotonation/rearomatization affords final product.

Scheme 17.

Radical trideuteromethylation of biphenylisocyanides to phenanthridines and isoquinolines.

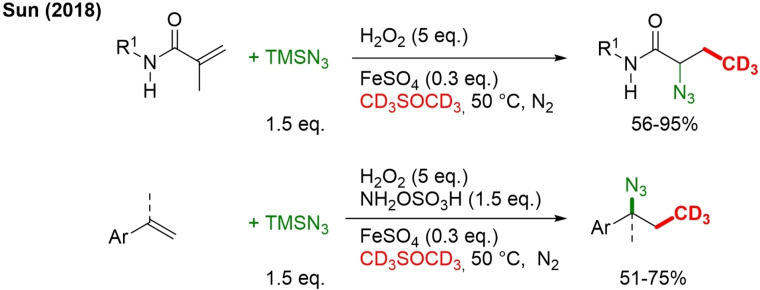

In the presence of TMSN3 and under N2, the same method was also adopted for 1‐step azido‐trideuteromethylation of active alkenes, which can then be further transformed to amines and heterocycles (Scheme 18).[82]

Scheme 18.

Radical azidotrideuteromethylation of acrylamides and styrenes.

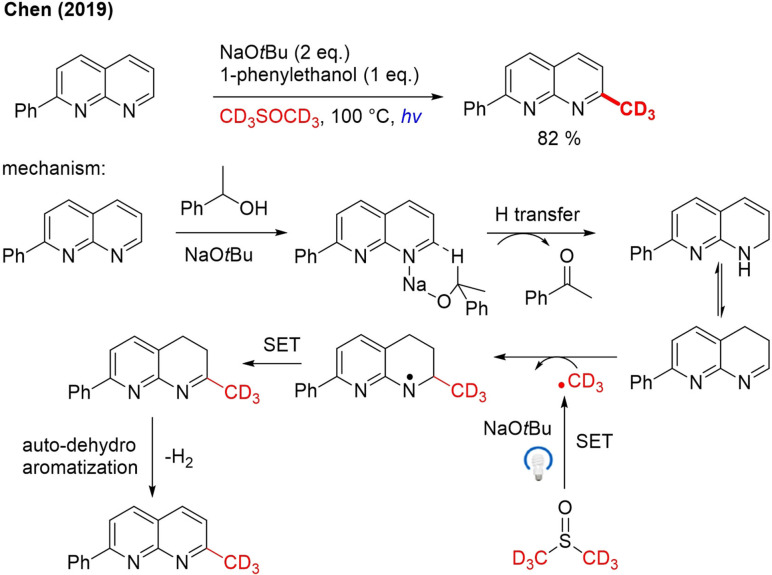

In 2019, Chen achieved radical trideuteromethylation without a TM catalyst. With NaOtBu as a base, PhEtOH as hydrogen donor, [D6]DMSO as a solvent and visible light irradiation a whole range of 1,8‐naphthyridine derivatives were trideuteromethylated (Scheme 19).[83] For methylation, heteroaryls, and electron‐withdrawing/donating substituents were tolerated. When the conditions were applied for other heterocycles such as indole, pyridine, isoquinoline, quinoline or quinoxaline no or very little product was formed. Two plausible mechanistic pathways are presented, but one is preferred by the authors on the basis of control experiments and recent literature reports.[84] In this mechanism, a sodium alkoxide formed by deprotonation of PhEtOH interacts with an iminium (Scheme 19). In a subsequent step, a Meerwein‐Pondof‐Verley‐Oppenauer (MPV−O) type hydrogen transfer and a protonation take place, leading to allyl amine formation, which tautomerizes to an enamine. This enamine is attacked by a CD3 radical generated from [D6]DMSO by single electron transfer (SET) in the presence of light and NaOtBu. The formed radical adduct undergoes another SET to an imine, which is converted to end product by dehydroaromatization.

Scheme 19.

TM‐free, light‐induced radical α‐trideuteromethylation of 1,8‐naphthyridines.

Furthermore, Glorius reported a mild method for regioselective radical trideuteromethylation of quinolines/isoquinolines with [D6]DMSO under photoredox conditions (Scheme 20).[85]

Scheme 20.

Radical trideuteromethylation of quinolines/isoquinolines by photo‐redox catalysis with [D6]DMSO.

In the presence of the electrophilic activator, PhPOCl2 trideuteromethyl radicals are generated from [D6]DMSO via the formation of chlorodi(trideuteromethyl)sulfonium species (Scheme 20), which is subsequently reduced via an electron shuttle process. The formed radical fragments generate the CD3 radical. To form product, the protonated starting material is reduced by SET in the presence of excited Iridium photocatalyst (PC) IrII*. Electron shuttling from the generated radical and chlorodi(trideuteromethyl)sulfonium species forms the CD3 radical, which attacks the substrate. The formed radical intermediate is oxidized via SET with the Ir PC and deprotonated to give the product.

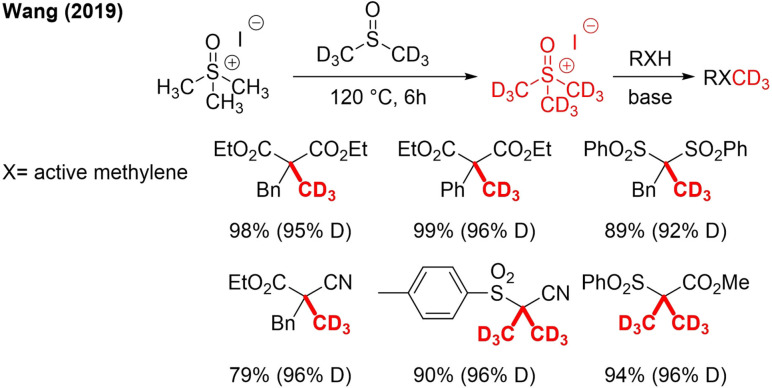

Very recently, a new trideuteromethylation reagent was developed by a metathesis reaction between [D6]DMSO and trimethylsulfoxonium iodide (TMSOI).[86] This reagent can become a cheap and nontoxic alternative for CD3I. The reagent was used as electrophilic CD3‐reagent (Scheme 21). The in situ preparation of the reagent and subsequent reaction were performed in one pot. One disadvantage of this reagent is that the deuteration is not always completely 100 %.

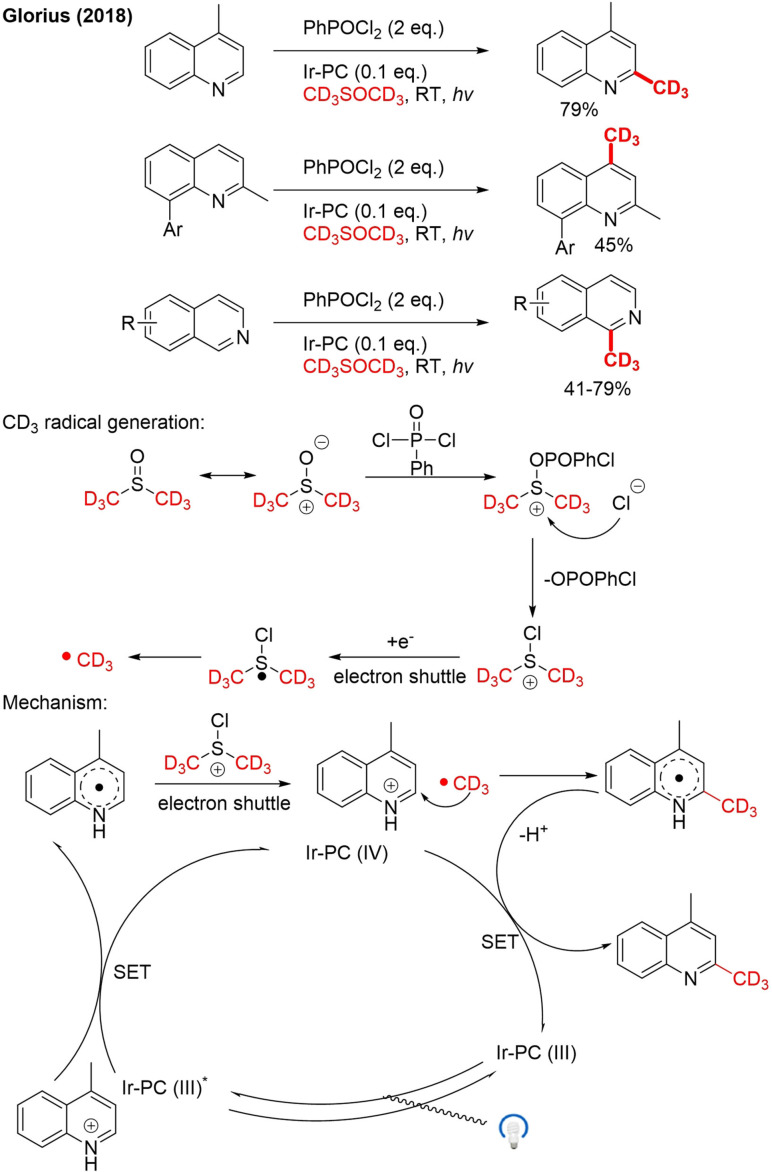

5. CD3OTs

Analogously to methyl tosylate, CD3OTs was recently employed as an electrophilic trideuteromethylation reagent that can be easily prepared from CD3OD and TsCl in one step.[87] In 2018, Osaka reported the transformation of ArX (X=I, Br, Cl, OTf) into ArCD3 by reductive coupling with CD3OTs using Ni/Co dual catalysis (Scheme 22a).[50] The Co catalyst plays a crucial role in transmethylation. Arenes with electron‐withdrawing/donating substituents underwent a smooth reaction. Heteroaryl iodides and even aryl triflate were compatible. Liao published another method for reductive trideuteromethylation in 2016, but in that case CD3I was applied as an electrophile (Scheme 8e).48 For this Co/Ni‐catalyzed reaction, a mechanism was also proposed. First, Mn generates active Ni0 and CoI catalysts by reduction (Scheme 22a). Then, OA of ArX to Ni0 occurs, followed by a reduction to a Ar‐NiI species. In the other cycle, the oxidative addition of CD3OTs to the nucleophilic CoI catalyst takes place. The two cycles come together during a transmetalation involving SET. By this process, high‐valent Ar‐NiIIIX−R is formed, and the CoI catalyst is regenerated. Finally, RE gives ArCD3 and NiIX, which are converted back to active Ni0 by reduction with Mn.

Scheme 22.

Trideuteromethylation of ArX with CD3OTs by reductive cross‐coupling a) using Co/Ni dual catalysis and b) under photoredox conditions.

MacMillan and co‐workers developed a method for methylation of aryl bromides and alkyl bromides under metallaphotoredox conditions in 2018.[88] They developed their method further in later work to also facilitate radiomethylation of alkyl‐ and aryl bromides.[89] The main focus of the article is on late‐stage functionalization of pharmaceutical derivatives with CT3 and 11CH3 units, but also one example was shown for CD3 installation (Scheme 22b). For the original metallaphotoredox methylation protocol, a clear mechanism was proposed, but for the trideuteromethylation under slightly adapted conditions, the authors did not provide the particular mechanism. However, it is likely that both reaction pathways are similar.

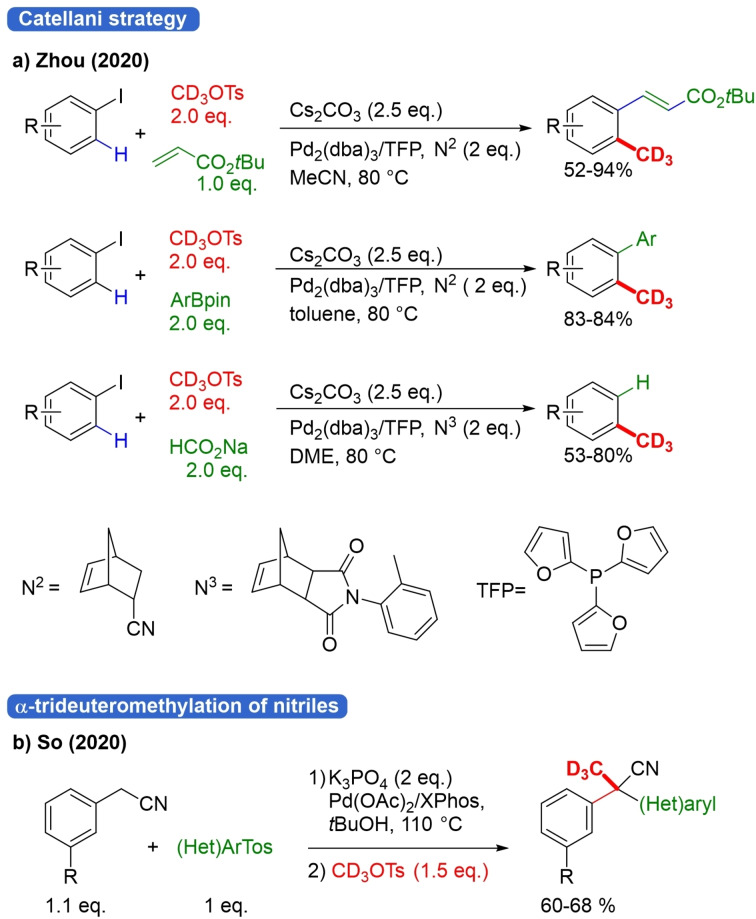

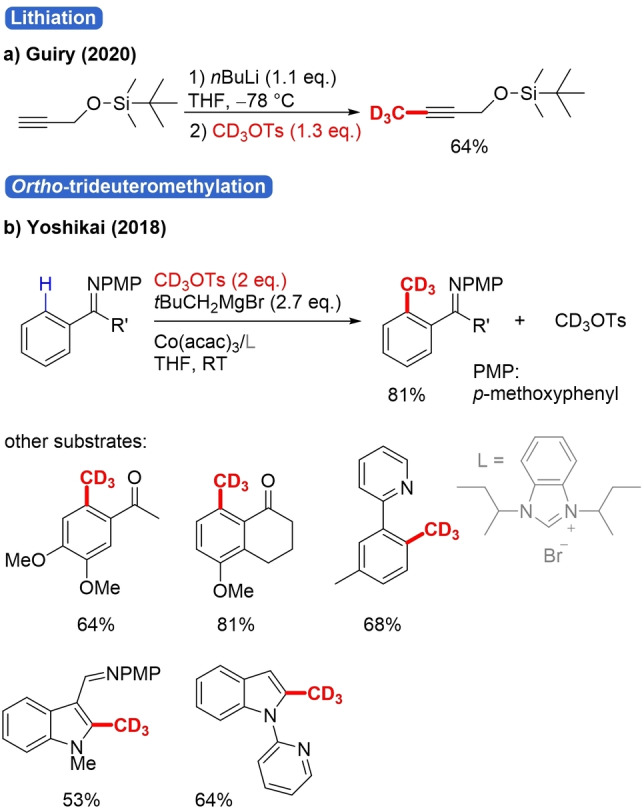

Apart from C−X, different C−H trideuteromethylation strategies with trideuterotosylate have been reported. The C−H of terminal alkynes can be transformed into C−CD3 via lithiation with nBuLi and trapping with CD3OTs as electrophile (Scheme 23a).[90] Two papers report TM‐catalyzed ortho‐trideuteromethylation relying on CD3OTs and various N‐directing groups, such as pyridine, para‐methoxyaniline and aminoquinoline (Scheme 23b).[91]

Scheme 23.

C−H Trideuteromethylation strategies with CD3OTs.

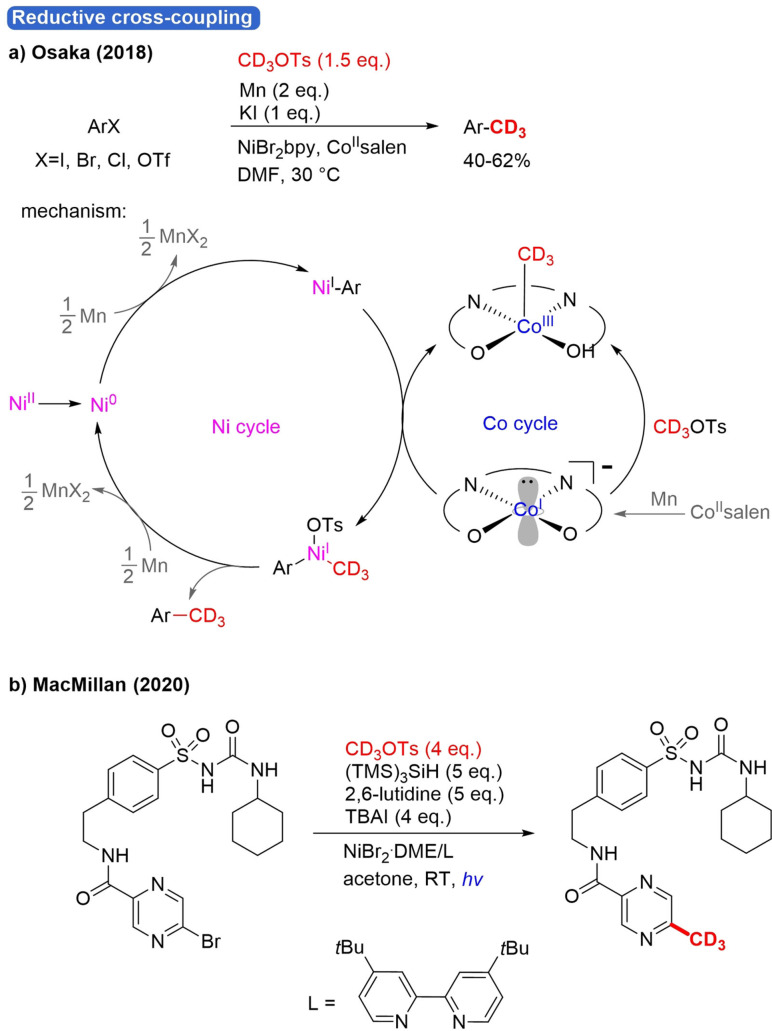

Recently, two further reports of trideuteromethylation reactions where CD3OTs was not the sole reagent appeared. In 2019, Zhou and co‐workers achieved the dual‐task trideuteromethylation of (hetero)aryliodides by a Catellani strategy using cooperative Pd/norbornene (NBE) catalysis and CD3OTs as trideuteromethyl source (Scheme 24a).[92] The method offers a toolbox to prepare a very wide array of trideuteromethylated arenes due to the combination of ortho C−H trideuteromethylation with an ipso cross‐coupling termination reaction using aryl iodide substrates. Heck, Suzuki and hydrogen ipso termination were achieved.

Scheme 24.

Trideuteromethylation with CD3OTs in multicomponent reactions.

In the case of methylation with the analog CH3OTs, the Sonogashira reaction, borylation and cyanation termination were shown. Scalability and late‐stage trideuteromethylation of drug‐like compounds with stereoretention were also demonstrated.

Notably, in the absence of another ortho‐substituent on the substrate di‐trideuteromethylation takes place. No mechanism is presented, but in literature some examples are shown with same type of dual‐task methylation via Catellani strategy.[92] However, in those cases, MeI was used as methylation reagent. Zhou et al. claimed that the use of MeOTs, which is less reactive and less volatile than MeI, was crucial for the success and wide scope of their strategy. The So group constructed quaternary C−CD3 bonds in a two‐step, one‐pot 3‐component reaction. The first step consists of α‐arylation of arylacetontrile with aryltosylate, and in the second step, CD3OTs is employed as the second electrophile (Scheme 24b).[94]

6. [D6]Dimethyl sulfate and [D3]methyl triflate

Some examples of trideuteromethylation with (CD3)2SO4 as an electrophile, such as lithiation followed by trapping and Wurtz coupling, can be found.[95] However, (CD3)2SO4 is an expensive, non‐abundant and toxic reagent that can be replaced by greener and more inexpensive electrophilic CD3 sources. Additionally, for the related [D3]methyl triflate (CD3SO3CF3) there is one example for lithiation of thiazole followed by trapping with [D3]methyl triflate as an electrophile.[93]

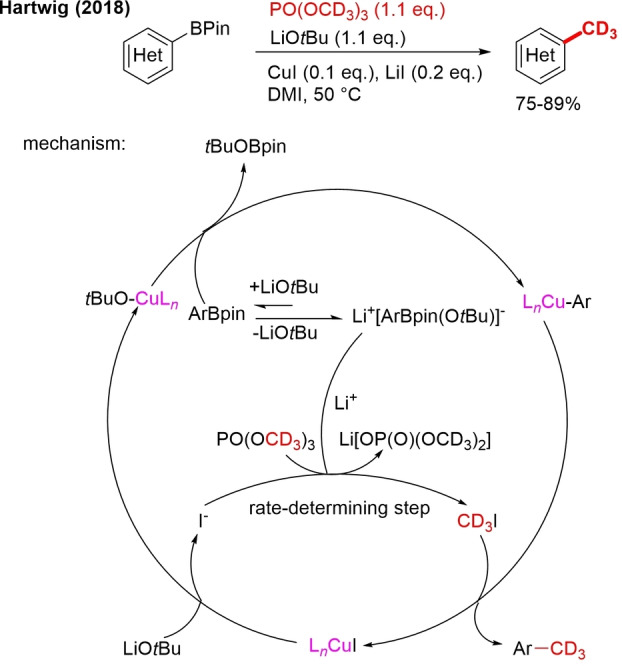

7. [D9]Trimethyl phosphate PO(OCD3)3

In 2018, Hartwig reported for the first time methylation with trimethyl phosphate as an inexpensive electrophilic methyl source.[97] Under the described reaction conditions, a whole range of (hetero)aryl boronic esters were methylated. As the trideuteromethyl analog, PO(OCD3)3, is also accessible, this method was equally demonstrated for trideuteromethylation (Scheme 25). Scalable and late‐stage site‐selective trideuteromethylation of a drug by one‐pot, two‐step borylation and trideuteromethylation is shown as well.

Scheme 25.

Trideuteromethylation (hetero)arylboronic ester with PO(OCD3)3.

After mechanistic studies, the authors proposed a mechanism starting with an exchange of iodine for tert‐butoxide on a CuII catalyst (Scheme 25). This free iodide ion is responsible for the slow generation of CD3I from PO(OCD3)3 in the presence of a Li+ Lewis‐acid catalyst, which makes CD3 more electrophilic. This free Li+ is taught to form by reaction of ArBpin with LiOtBu forming a Li+[ArBpin(OtBu)]− species. The CuIOtBu species, newly formed after OtBu−/I− exchange, undergoes transmetalation with ArBpin to form a copper aryl species that reacts with the generated CD3I, forming ArCD3. Slow generation of MeI is claimed to be crucial to ensure selective reaction with arylcopper species over basic groups on aryl boronate substrates. The need for PO(OCH3)3 as a methylation reagent was also demonstrated because with MeI and MeOTs, the yields were significantly lower under the same reaction conditions.

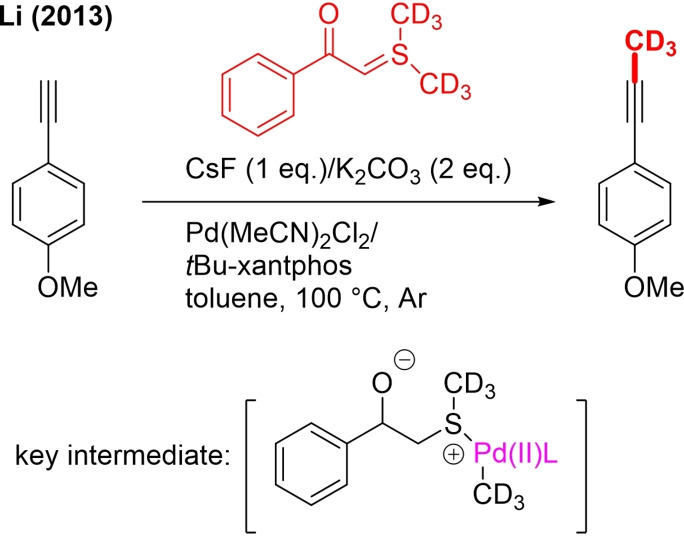

8. Bis(trideuteromethyl)sulfonium Ylide

Dimethyl sulfonium ylides can act as methyl electrophiles and cross‐coupled with terminal alkynes in presence of a Pd catalyst.[99] Unlike the classical Sonogashira reaction for C(sp)‐C(sp3) bond formation, this reaction is copper‐free. It was demonstrated that interchanging the two methyl groups of the sulfonium ylide for CD3 groups leads to trideuteromethylation of terminal alkynes (Scheme 26). Preparation of the CD3‐analog was done by the reaction of [D6]dimethylsulfide with 2‐bromoacetophenone. A broad range of electron‐rich and electron‐deficient aryl alkynes smoothly underwent the reaction. Additionally, aliphatic, vinyl, O/N/Si substituted alkynes are compatible with the protocol. Following a mechanistic study, it was proposed that first, oxidative insertion of Pd0 in S‐CD3 occurs (Scheme 26), followed by ylide‐ to‐alkyne exchange and finally RE of the product.

Scheme 26.

Trideuteromethylation of terminal alkyne via Pd‐catalyzed cross‐coupling with bis(trideuteromethyl)sulfonium ylide.

9. CD3B(OH)2/CD3BF3K

The Hassner group achieved trideuteromethylation of a bromopyridine unit by the Suzuki‐Miyaura reaction using trideuteromethyl boronic acid and potassium trideuteromethyl trifluoroborate as nucleophilic CD3 sources.[46a] These reagents can be prepared from CD3I in one and two steps, respectively.

The method was demonstrated for the noncryogenic preparation of the 5‐CD3 version of the drug pirfenidone (Scheme 27). The use of the RuPhos ligand was critical to obtain a high yield. This method can still be explored much further and become an important strategy for late‐stage trideuteromethylation in drug development.

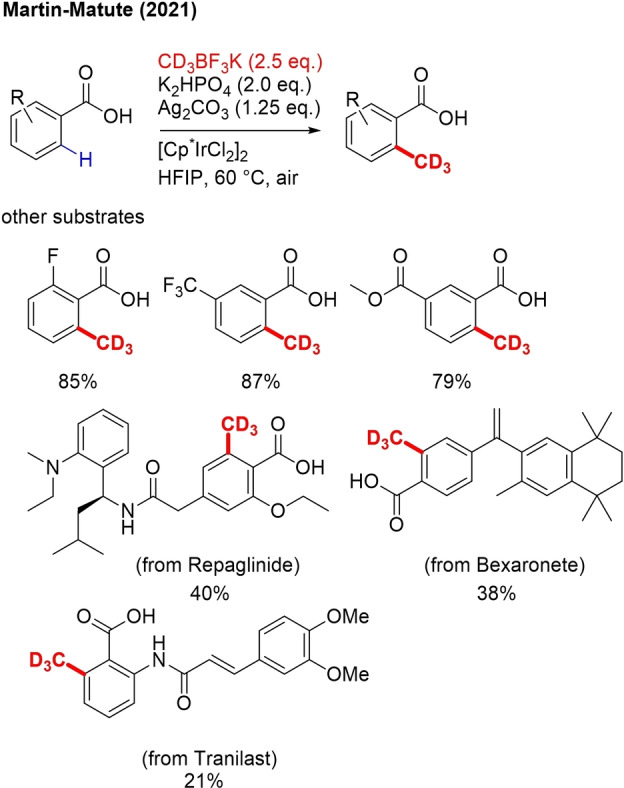

Very recently, a method has been reported for ortho C−H (trideutero)methylation of aryl carboxylic acids with CD3BF3K as trideuteromethylation reagent, under air (Scheme 28).[100] The method requires a [Cp*IrCl2] precatalyst, KHPO2 as base and Ag2CO3 as stoichiometric oxidant. Both electron‐donating and electron‐withdrawing substituents on the aryl ring are tolerated and other potential directing groups did not interfere. In the case of ortho‐methylation also heteroaryl moieties could be applied. Interestingly, this method allows C−H methylations of benzoic acid‐containing drugs with high functional group diversity and multiple potential C−H activation sites. No mechanism was presented.

Scheme 28.

Ir‐catalyzed ortho‐trideuteromethylation of aryl carboxylic acids.

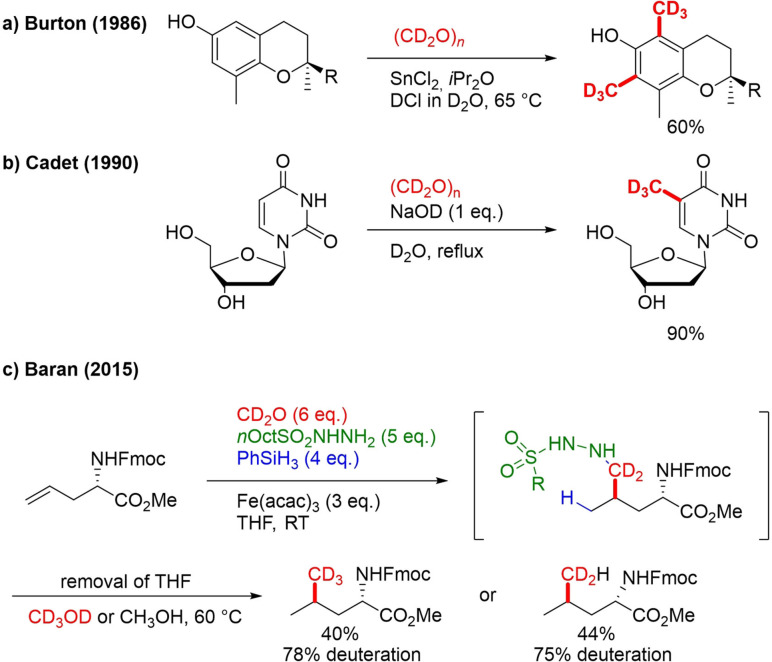

10. [D2]Formaldehyde and (CD2O)n

In literature, some reports can be found on the use of [D2]formaldehyde and deuterated paraformaldehyde in combination with another deuterated reagent for C−CD3 formation. Burton, for example, depended on (CD2O)n/DCl/D2O as deuterated compound mixture for the di‐trideuteromethylation of a α‐tocopherol (Scheme 29a). The reaction is based on SnCl2‐catalyzed methylation protocol.[101] Cadet used deuterated paraformaldehyde in presence of NaOD and D2O (reflux) for trideuteromethylation of 2’‐deoxyuridine (Scheme 29b) to afford CD3‐thymidine.[102] Baran developed a protocol for one‐pot, two‐step Markovnikov hydromethylation that relies on d2 ‐formaldehyde.[63] In the first step, the iron‐catalyzed preparation of hydrazide is achieved from in situ‐formed formaldehyde, hydrazine and an alkene substrate (Scheme 28c). A solvent switch from THF to methanol and gentle heating to 60 °C in the second step facilitates the C−N reduction to deliver the final product. The protocol was demonstrated for hydromethylation of mono‐, di‐ and trisubstituted alkenes containing acid‐labile, Lewis basic, acid and reducible functional groups. For deuterium labeling l‐Fmoc‐allylglycine‐OMe was transformed to l‐Fmoc‐leucine‐OMe. Using CD2O/CD3OD afforded CD3‐product in a 40 % yield with 78 % deuteration (Scheme 29c). Incomplete deuteration of alkyl hydrazide intermediate is presumably responsible for not reaching 100 % deuteration overall. In the case of CD2O/CH3OH, a perfectly CD2H‐labeled product was acquired in 44 % yield.

Scheme 29.

CD2O‐mediated trideuteromethylation.

Although [D2]formaldehyde is a unique reagent that facilitates very specific transformations towards CD3 labeled compounds, there are a number of drawbacks connected to its use, such as high toxicity, price and volatility.

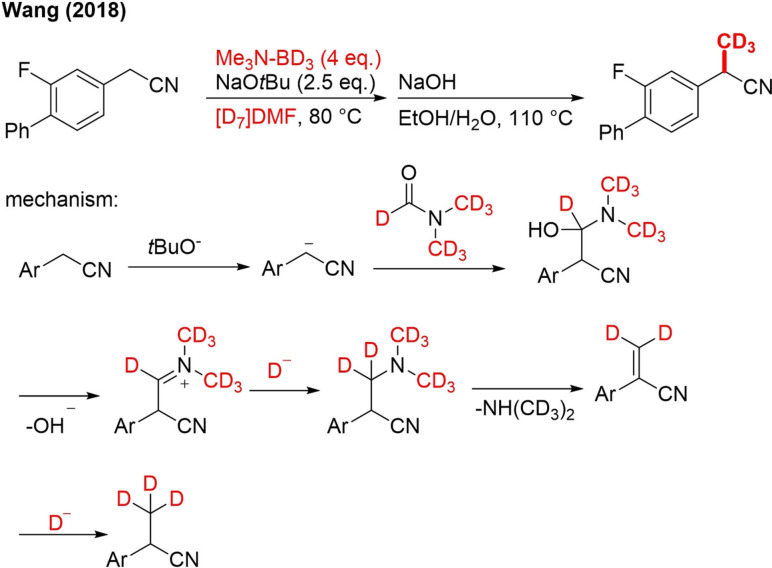

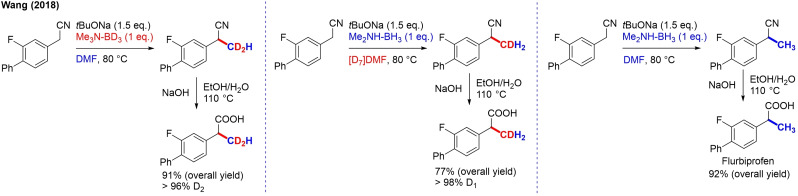

11. The [D7]‐DMF/NMe3‐BD3 System

Direct TM‐free mono α‐trideuteromethylation of aryl acetonitriles and aryl acetamides is possible under mild conditions using the combined system NMe3‐BD3/DCON(CD3)2 (Scheme 30).[103]

Scheme 30.

Preparation of the CD3‐flurbiprofen precursor by α‐trideuteromethylation of aryl acetonitriles.

Mechanistic studies with isotopically labeled reagents demonstrated that the formyl group of DMF delivers the carbon atom and one hydrogen atom.

BH3 was then the source of the other 2 hydrogen atoms. The mechanism, which was finally proposed on the basis of these studies, initiates with deprotonation at the α‐position, followed by nucleophilic addition of the carbanion on [D7]DMF (Scheme 30). In the next step, hydroxyl elimination occurs, and the formed iminium ion is reduced by a deuteride anion originating from NMe3‐BD3. The di(trideuteromethyl)arylacetonitrile undergoes an E1cb elimination of (CD3)2NH, leading to the formation of an acrylonitrile. A second deuteride reduction finally affords the product. As such, this approach allows selective installation of CH3, CD3, CH2D and CD2H units by using the right combination of Me2NH‐BH3/Me3N‐BD3 and DMF/[D7]DMF (Scheme 31). As both BD3 and DCON(CD3)2 are relatively inexpensive and abundant deuterium sources and no transition metal catalyst is used, this method can be adopted on an industrial scale.

Scheme 31.

Preparation of CD2H/CDH2/CH3 flurbiprofen precursors by α‐trideuteromethylation of arylacetonitriles.

12. The CO2/D2 System

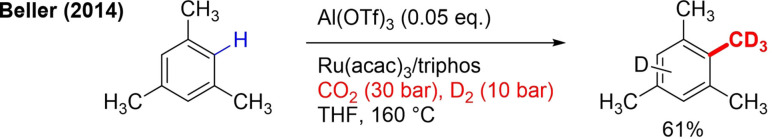

The Beller group is the only group to date to achieve C−H methylation of (hetero)arenes using abundant and inexpensive CO2 as a green C‐1 carbon source.[104] Inexpensive H2 is used as reductant. By replacing H2 by D2, CD3 installation was also demonstrated. The reaction is catalyzed by a ruthenium catalyst and Lewis acid (Scheme 32).

Scheme 32.

C−H trideuteromethylation of an arene relying on CO2/D2 system.

The method is so far limited to electron‐rich (hetero)arenes, and dimethylation also occurs. In the case of CD3 installation, H/D exchange on the aromatic ring also takes place, yielding a mixture of products.

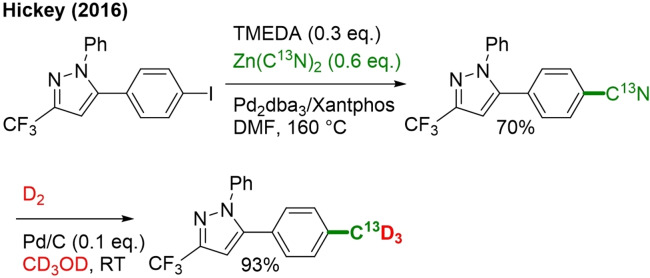

13. The Zn(CN)2+CD3OD/D2 System

CD3 installation under reductive conditions can also be performed by reduction of a nitrile group with D2 and Pd/C catalyst in deuterated methanol (Scheme 33).[105]

Scheme 33.

Preparation of the 13CD3 version of Celecoxib by nitrile introduction followed by reduction with D2 in CD3OD.

Nitrile groups, which act as the carbon source, were introduced by the reaction of ArI with Zn(CN)2 via Negishi coupling. This method enables the introduction of different types of labeled methyl groups by choosing the appropriate nitrile and reduction reagent.

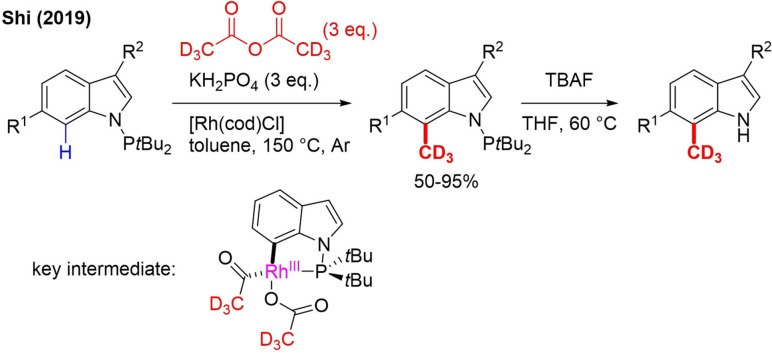

14. [D6]Acetic Anhydride

In 2019, the use of the cheap and abundant [D6]acetic anhydride as a trideuteromethylation reagent was reported. C7 site‐selective decarbonylative trideuteromethylation of PtBu2N‐substituted indoles is performed in the presence of a Rhodium catalyst (Scheme 34).[106]

Scheme 34.

Rhodium‐catalyzed C7 trideuteromethylation of indole and subsequent removal of the directing group.

With CD3OTs and CD3OD, trideuteromethylation of the C1 and C2 positions could already be achieved (Schemes 23 and 6, respectively).[21, 36b, 91b] This C7‐ trideuteromethylation is very unique and occurs due to the PtBu2‐directing group. Another asset of this method is that the directing group can be easily removed. One small drawback is that partial deuteration of the C2 position occurs when that position is not substituted. Mechanistically, the authors propose formation of a rhodacycle followed by OA of [D6]acetic anhydride (Scheme 33) and decarbonylation. RE as the final step gives the product.

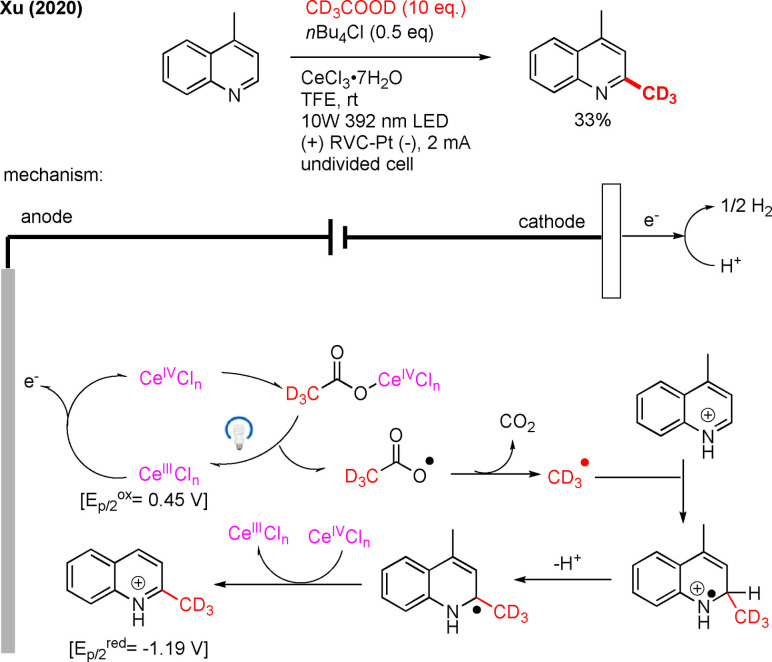

15. CD3COOD

Very recently, the Xu′s group achieved C−H functionalization of heteroarenes under decarboxylative electro‐photocatalytic conditions (Scheme 35).[107] This Minisci‐type reaction occurs through hydrogen evolution and could be performed oxidant‐free by merging electrochemistry and photocatalysis.

Scheme 35.

Decarboxylative trideuteromethylation of heteroarene under electro‐photocatalytic conditions.

Additionally, one trideuteromethylation example was shown for their method (Scheme 35), using CD3COOD which can be prepared by pyrolysis of [D4]malonic acid.[108] Apart from light and electricity, the method also relies on a cerium catalyst. The proposed mechanism is described as follows: The CeIII catalyst is anodically oxidized to CeIV, which coordinates to CD3COOH (Scheme 36). This complex undergoes photoinduced ligand‐to‐metal charge transfer (MLCT) to revert to CeIII and to form a carboxyl radical, which leads to the CD3‐radical after decarboxylation. The CD3‐radical will then attack the protonated lepidine, that subsequently will undergo deprotonation. Finally, oxidation by CeIV affords trideuteromethylated product. The method was demonstrated to be scalable and applicable for late‐stage functionalization. The described transformation has also been achieved with [D6]DMSO under photoredox conditions by Glorius (Scheme 20).

Scheme 36.

‐ Site‐selective di‐trideuteromethylation of ortho‐substituted iodoarenes.

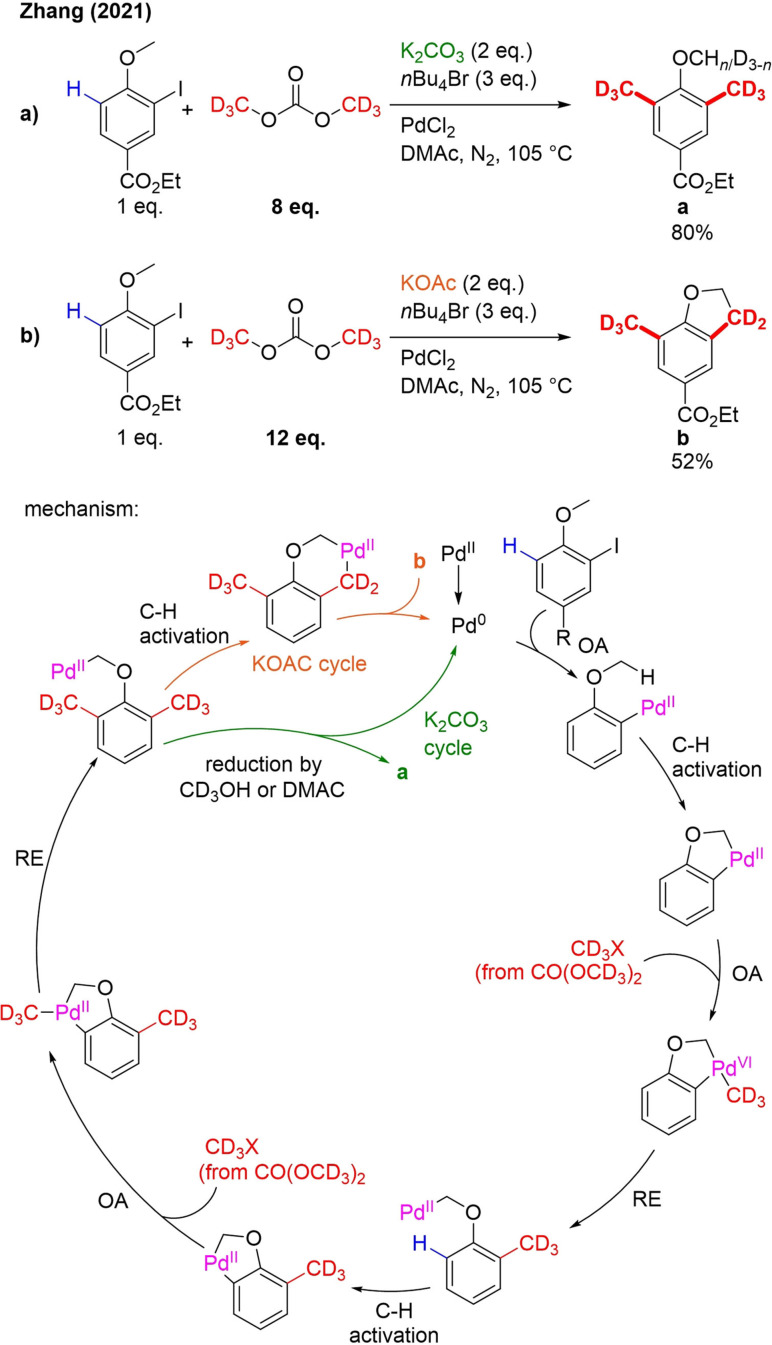

16. [D6]Dimethyl Carbonate ([D6]DMC)

Very recently, [D6]dimethyl carbonate was introduced as a new trideuteromethylation reagent. The Zhang group developed a new strategy for site‐selective di(trideutero)methylation using ortho‐substituted iodoarenes as substrates, K2CO3 as a base, PdCl2 as catalyst and [D6]dimethyl carbonate as the trideuteromethyl source (Scheme 36a).[109] [D6]DMC is a very interesting reagent. It can be readily prepared from CD3OD and CO and can be easily handled.[110] The described di‐trideuteromethylation occurs at the ipso‐ and meta‐position in relation to the iodide, thus leading to meta‐C−H functionalization. The iodide group can thus be seen as a traceless directing group. Heteroaryl substituents and groups in meta‐position of iodide were compatible with the reaction conditions. Apart from ortho‐methoxy, also ortho‐benzyl furnished the expected products. For the methylation process, it was shown that also 2‐bromoanisoles are good substrates. However, Pd(o‐tol)3 had to be used as a catalyst. In the case of methylation, both late‐stage modification and upscaling were demonstrated. If KOAc was used as a base, instead of K2CO3, subsequent oxidative C(sp3)‐H/ C(sp3)‐H oxidative coupling can take place (Scheme 35b), leading to CD3‐labeled dihydrobenzofurane derivatives, when a methoxy ortho‐substituent is present. It was also shown that in case of an ortho‐alkyl substituent, CH3‐functionalized indanes can be prepared.

Mechanistic studies suggested the following reaction pathway (Scheme 36): After oxidative insertion of PdII in the aryl–I bond, a palladacycle is formed due to C−H activation. This palladacycle undergoes an OA with CD3X, generated from [D6]DMC and probably nBu4Br. RE leads to ipso‐trideuteromethylation and cleavage of an aryl C−H bond, furnishing a second palladacycle. This second palladacycle is involved in the same process and affords meta‐trideuteromethylation. In case of K2CO3, the complex formed after RE will be reduced by DMAC or CD3OD (generated from [D6]DMC) to furnish the product. If on the other hand KOAc is used as a base, another C−H activation can occur to form a palladacycle for a third time, which finally undergoes RE to afford the dihydrobenzofurane derivative.

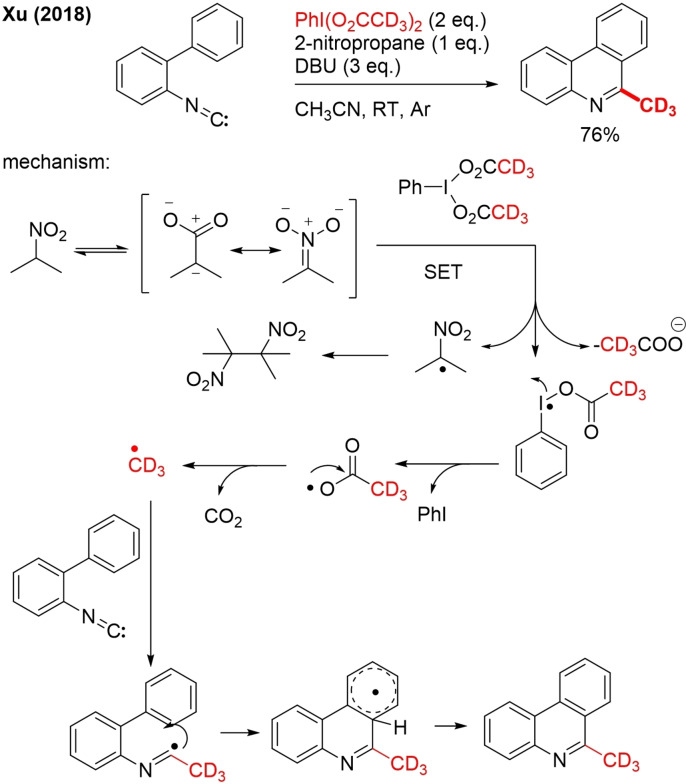

17. [D6]PhIOAc2/2‐Nitropropane

The hypervalent iodine reagent PhIOAc2 in the presence of 2‐nitropropane can act as a source of methyl radicals.[111] This interesting method has many advantages over the more established methods for methyl radical generation from DMSO and peroxides. The reaction conditions are milder, and no metals are involved. PhIOAc2 acts as both an oxidant and a methyl radical source, and the generated by‐product PhI can be reused to synthesize PhIOAc2. 6‐methyl‐phenanthridines containing a wide variety of functional groups can be prepared from biphenylisocyanides via radical cascade cyclization. In a mechanistic study, trideuteromethylation was demonstrated by using [D6]PhIOAc2 (PhI(O2CCD3)2 instead of PhIOAc2, clearly proving that hypervalent iodine is the source of the methyl/trideuteromethyl group. Site‐selective methylation of isoquinolines was also demonstrated using this protocol but no example of trideuteromethylation was shown. However, for other aromatic heterocycles, such as benzoxazoles and benzothiazole, no product was formed. For the generation of (trideutero)methyl radicals, a mechanism is proposed whereby 2‐nitropropane is first deprotonated by DBU (Scheme 37).

Scheme 37.

6‐CD3‐phenanthridine preparation by radical trideuteromethylation of biphenylisocyanide with PhI(O2CCD3) as trideuteromethyl radical source.

In the next step, the resonance‐stabilized nitronate anion reacts with PhI(O2CCD3) by SET. The iodoanyl radical formed by this reduction step undergoes fragmentation via homolytic cleavage of the I−O bond. Decarboxylation of the [D3]acetoxyl radical generates the CD3 radical that can react with the isocyanide. Radical cyclization, followed by deprotonation/aromatization affords end product.

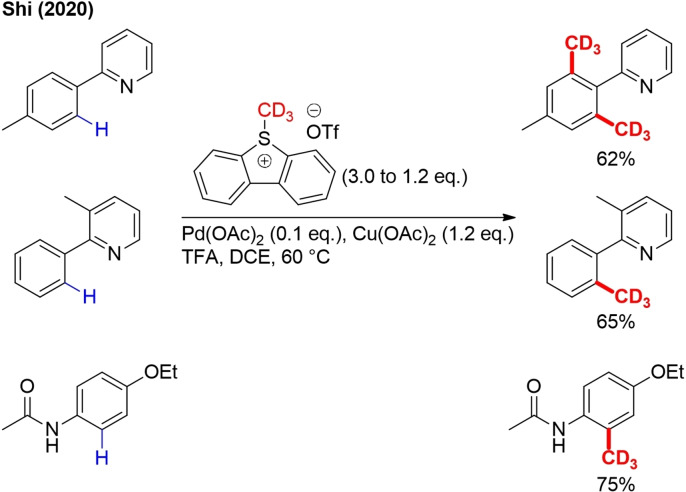

18. 5‐([D3]Methyl)‐5H‐dibenzo[b,d]thiophen‐5‐ium Trifluoromethane Sulfonate (DMTT)

Inspired by the reactivity profile of S‐adenosylmethionine (SAM) and making use of the design principle of the Umemoto reagent, the Shi group developed 5‐([D3]methyl)‐5H‐dibenzo[b,d]thiophen‐5‐ium trifluoromethane sulfonate (DMTT) as a [D3]methylating S‐adenosylmethionine (SAM) analog.[112]

[D3]Methylation with this reagent occurs biomimetically and analogous to SAM chemistry in living organisms, thus exhibiting high chemoselectivity under very mild conditions. This reagent is stable at ambient temperature and can be easily prepared on a large scale from dibenzothiophene and CD3OD. It was demonstrated that this reagent could be applied in TM‐catalyzed directed ortho‐trideuteromethylation of arenes with pyridyl and acetylamino directing groups (Scheme 38). More classical CD3 reagents, such as CD3I and (CD3)2SO4, could not deliver products under the same reaction conditions.

Scheme 38.

TM‐catalyzed ortho‐trideuteromethylation of arenes with DMTT.

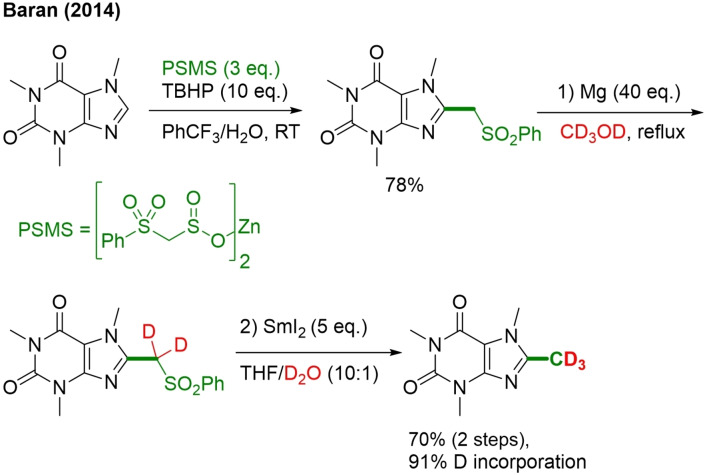

19. Zinc Bis(phenylsulfonylmethanesulfinate) (PSMS)/CD3OD/D2O

The Baran group developed a biomimetic and SAM‐inspired protocol. Their method affords C−H methylation of heteroarenes.[113] Slightly adapting the conditions and one extra reaction step made this protocol applicable for trideuteromethylation (Scheme 39). For this protocol, a new bench‐stable reagent, zinc bis(phenylsulfonylmethanesulfinate) (PSMS), was developed as a methyl radical surrogate. This reagent will react chemoselective with the heteroarene at the most electron‐rich position, at room temperature and under air, to form (phenylsulfonyl)methylated intermediate, which can be easily desulfonylated to form the methylated product. If CD3OD is used instead of MeOH, and an extra step with SmI2 in THF/D2O is performed, trideuteromethylation is achieved instead of methylation.

Scheme 39.

C−H trideuteromethylation of heteroarene by using PSMS/CD3OD/D2O.

This method has multiple advantages. The sulfonylated intermediate is very easy to separate from starting material due to the difference in polarity. Unlike for other methyl radical sources, the reaction can be conducted under air at room temperature, and the conditions are mild, allowing late‐stage functionalization/ compatibility with sensitive functional groups. Despite these advantages, this method also has limitations: as PSMS reacts as an electrophilic radical, the reaction with electron‐poor pyridine gives poor yields and in the case of CD3 installation, the degree of deuteration is not a complete 100 %.

20. Summary and Perspective

In this article, we have presented the currently established methods for site‐selective installation of a CD3 group, classified on the basis of the reagent. This review can function as a guide for choosing the most appropriate strategy to prepare new site‐selectively CD3‐labeled organic molecules. Trideuteromethylation has been less explored than site‐selective methylation. Not surprisingly, most of the methods known make use of a CD3 reagent, which is readily available or can be easily prepared. Often new methylation methods do not present CD3 examples, whereas in most cases, the analogous CD3 reagent is readily available or can easily be prepared.[114] Examples of C−CD3 bond formation reactions involving reactants such as Sn(CD3)4, ZnCD3/CD3ZnBr, PhN+(CD3)3 or Al(CD3)3 analogs are not reported. Peroxides, an important class for radical methylation, were also not applied in trideuteromethylation. This is, however, more understandable, as CD3 analogs of the classically used peroxide reagents are synthetically difficult to attain. Considering the renewed interest in trideuteromethylated drugs and the fact that the majority of top‐selling drugs contain a methyl group, publications on new methylation strategies should include trideuteromethylation examples in their scope whenever possible. To further advance drug development, mild late‐stage and green (trideutero)methylation strategies are still in high demand.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Biographical Information

Joost Steverlynck graduated in 2012 with an M.Sc. in chemistry from KU Leuven (Belgium). As a fellow of the Agency for Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders (IWT) he obtained a PhD on the synthesis and self‐assembly of conjugated polymers with nonlinear topologies under the supervision of Prof. Guy Koeckelberghs. He continued as a postdoctoral researcher under the supervision of Prof. Thierry Verbiest, focusing on the synthesis of conjugated liquid‐crystalline materials with high Faraday response. In 2019, he started to work in the group of Prof. Magnus Rueping at KAUST (Saudi Arabia).

Biographical Information

Ruzal Sitdikov studied at Kazan University (KFU, Russia) with a focus on supramolecular organic chemistry. He obtained his Ph.D. under Prof. Ivan Stoikov in 2015 on thiacalix[4]arene receptors. In 2015 he worked on electroactive pillar[n]arenes at the KU Leuven, Belgium (Prof. Wim Dehaen's group, Erasmus Mundus grantee). Between 2016 and 2018, he performed research in supramolecular glycochemistry at the KTH, Sweden (Prof. Olof Ramström's group, Visby scholarship holder) and at the Åbo Akademi, Finland (Prof. Reko Leino's group, Johan Gadolin scholarship). Since 2019, he has been a postdoctoral researcher in Magnus Rueping's group developing modern electrosynthetic reactions at KAUST (Saudi Arabia).

Biographical Information

Magnus Rueping studied at the TU Berlin and Trinity College Dublin before obtaining his doctoral degree from the ETH Zürich in 2002 under Prof. Dieter Seebach. He conducted postdoctoral studies with Prof. David A. Evans at Harvard University. In 2004, he was appointed Degussa Endowed Professor for Synthetic Organic Chemistry at the Goethe Universität Frankfurt. After four years, he accepted a Chair at the RWTH Aachen. Since 2016 he has been a Professor of Chemical and Biological Sciences at KAUST and Associate Director of the KAUST Catalysis Center. His group researches the development and simplification of synthetic catalytic methodology and technology, and their application in the rapid synthesis of diverse functional natural and unnatural molecules.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Saudi Arabia, Office of Sponsored Research (FCC/1/1974). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

J. Steverlynck, R. Sitdikov, M. Rueping, Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 11751.

References

- 1.

- 1a.Njardarson, “Top 200 Pharmaceutical Products by US Retail Sales in 2019”, https://njardarson.lab.arizona.edu/content/top-pharmaceuticals-poster;

- 1b.McGrath N. A., Brichacek M., Njardarson J. T., J. Chem. Educ. 2010, 87, 1348–1349; [Google Scholar]

- 1c.Sun S., Fu J., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 3283–3289; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1d.Talele T. T., J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2166–2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a.Okano M., Bell D. W., Haber D. A., Li E., Cell 1999, 99, 247–257; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2b.Choy J. S., Wei S., Lee J. Y., Tan S., Chu S., Lee T.-H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 1782–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.

- 3a.Nan X., Ng H.-H., Johnson C. A., Laherty C. D., Turner B. M., Eisenman R. N., Bird A., Nature 1998, 393, 386–389; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3b.Lachner M., O′Carroll D., Rea S., Mechtler K., Jenuwein T., Nature 2001, 410, 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a.Barreiro E. J., Kummerle A. E., Fraga C. A., Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 5215–5246; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b.Ritchie T. J., Macdonald S. J. F., Pickett S. D., MedChemComm 2015, 6, 1787–1797; [Google Scholar]

- 4c.Kuntz K. W., Campbell J. E., Keilhack H., Pollock R. M., Knutson S. K., Porter-Scott M., Richon V. M., Sneeringer C. J., Wigle T. J., Allain C. J., Majer C. R., Moyer M. P., Copeland R. A., Chesworth R., J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 1556–1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hann M. M., Keserü G. M., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2012, 11, 355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.

- 6a.Li L., Beaulieu C., Carriere M.-C., Denis D., Greig G., Guay D., O'Neill G., Zamboni R., Wang Z., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 7462–7465; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6b.Smith C. J., Ali A., Hammond M. L., Li H., Lu Z., Napolitano J., Taylor G. E., Thompson C. F., Anderson M. S., Chen Y., J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 4880–4895; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6c.Zhang L., Brodney M. A., Candler J., Doran A. C., Duplantier A. J., Efremov I. V., Evrard E., Kraus K., Ganong A. H., Haas J. A., J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1724–1739; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6d.Leung C. S., Leung S. S., Tirado-Rives J., Jorgensen W. L., J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4489–4500; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6e.Schonherr H., Cernak T., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 12256–12267; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 12480–12492. [Google Scholar]

- 7.

- 7a.Sekiyama N., Hayashi Y., Nakanishi S., Jane D., Tse H. W., Birse E., Watkins J., Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996, 117, 1493–1503; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7b.Goodman A. J., Le Bourdonnec B., Dolle R. E., ChemMedChem 2007, 2, 1552–1570; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7c.Wood M. R., Hopkins C. R., Brogan J. T., Conn P. J., Lindsley C. W., Biochemistry 2011, 50, 2403–2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.

- 8a.Costello G. F., James R., Shaw J. S., Slater A. M., Stutchbury N. C., J. Med. Chem. 1991, 34, 181–189; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8b.Angell R., Aston N. M., Bamborough P., Buckton J. B., Cockerill S., deBoeck S. J., Edwards C. D., Holmes D. S., Jones K. L., Laine D. I., Patel S., Smee P. A., Smith K. J., Somers D. O., Walker A. L., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4428–4432; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8c.Berardi F., Abate C., Ferorelli S., de Robertis A. F., Leopoldo M., Colabufo N. A., Niso M., Perrone R., J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7523–7531; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8d.Kopecky D. J., Hao X., Chen Y., Fu J., Jiao X., Jaen J. C., Cardozo M. G., Liu J., Wang Z., Walker N. P., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 6352–6356; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8e.Ghosh A. K., Takayama J., Rao K. V., Ratia K., Chaudhuri R., Mulhearn D. C., Lee H., Nichols D. B., Baliji S., Baker S. C., J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4968–4979; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8f.Lansdell M. I., Hepworth D., Calabrese A., Brown A. D., Blagg J., Burring D. J., Wilson P., Fradet D., Brown T. B., Quinton F., J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 3183–3197; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8g.Judd W. R., Slattum P. M., Hoang K. C., Bhoite L., Valppu L., Alberts G., Brown B., Roth B., Ostanin K., Huang L., J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5031–5047; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8h.Coleman P. J., Schreier J. D., Cox C. D., Breslin M. J., Whitman D. B., Bogusky M. J., McGaughey G. B., Bednar R. A., Lemaire W., Doran S. M., ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 415–424; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8i.Quancard J., Bollbuck B., Janser P., Angst D., Berst F., Buehlmayer P., Streiff M., Beerli C., Brinkmann V., Guerini D., Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 1142–1151; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8j.Hwang J. Y., Smithson D., Zhu F., Holbrook G., Connelly M. C., Kaiser M., Brun R., Guy R. K., J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2850–2860; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8k.O'Reilly M. C., Scott S. A., Brown K. A., Oguin T. H. III, Thomas P. G., Daniels J. S., Morrison R., Brown H. A., Lindsley C. W., J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2695–2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams F. M., Pharmacol. Ther. 1987, 34, 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lipinski C. A., J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 235–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a.Lovering F., Bikker J., Humblet C., J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6752–6756; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11b.Lovering F., MedChemComm 2013, 4, 515–519. [Google Scholar]

- 12.

- 12a.Biron E., Chatterjee J., Ovadia O., Langenegger D., Brueggen J., Hoyer D., Schmid H. A., Jelinek R., Gilon C., Hoffman A., Kessler H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 2595–2599; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 2633–2637; [Google Scholar]

- 12b.Chatterjee J., Gilon C., Hoffman A., Kessler H., Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1331–1342; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12c.Pasternak A., Goble S. D., Struthers M., Vicario P. P., Ayala J. M., Di Salvo J., Kilburn R., Wisniewski T., DeMartino J. A., Mills S. G., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1, 14–18; [Google Scholar]

- 12d.White T. R., Renzelman C. M., Rand A. C., Rezai T., McEwen C. M., Gelev V. M., Turner R. A., Linington R. G., Leung S. S. F., Kalgutkar A. S., Bauman J. N., Zhang Y. Z., Liras S., Price D. A., Mathiowetz A. M., Jacobson M. P., Lokey R. S., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 810–817; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12e.Hilimire T. A., Bennett R. P., Stewart R. A., Garcia-Miranda P., Blume A., Becker J., Sherer N., Helms E. D., Butcher S. E., Smith H. C., Miller B. L., ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 88–94; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12f.Koay Y. C., Richardson N. L., Zaiter S. S., Kho J., Nguyen S. Y., Tran D. H., Lee K. W., Buckton L. K., McAlpine S. R., ChemMedChem 2016, 11, 881–892; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12g.Li W. J., Hu K., Zhang Q. Z., Wang D. Y., Ma Y., Hou Z. F., Yin F., Li Z. G., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 1865–1868; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12h.Rader A. F. B., Reichart F., Weinmuller M., Kessler H., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 26, 2766–2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.

- 13a.Gant T. G., J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 3595–3611; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13b.Mullard A., Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15, 219–221; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13c.Hearn B. R., Fontaine S. D., Pfaff S. J., Schneider E. L., Henise J., Ashley G. W., Santi D. V., J. Controlled Release 2018, 278, 74–79; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13d.Pirali T., Serafini M., Cargnin S., Genazzani A. A., J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 5276–5297; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13e.Russak E. M., Bednarczyk E. M., Ann. Pharmacother. 2019, 53, 211–216; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13f.Stringer R. A., Williams G., Picard F., Sohal B., Kretz O., McKenna J., Krauser J. A., Drug Metab. Dispos. 2014, 42, 954–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.

- 14a.Katsnelson A., Nat. Med. 2013, 19, 656; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14b.Timmins G. S., Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017, 27, 1353–1361; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14c.Cargnin S., Serafini M., Pirali T., Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 2039–2042; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14d.Ou W., Xiang X., Zou R., Xu Q., Loh K. P., Su C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6357–6361; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 6427–6431. [Google Scholar]

- 15.

- 15a.Timmins G. S., Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2014, 24, 1067–1075; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15b.Tung R. D., Future Med. Chem. 2016, 8, 491–494; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15c.Schmidt C., Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 493–494; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15d.DeWitt S. H., Maryanoff B. E., Biochemistry 2018, 57, 472–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cargnin S., Serafini M., Pirali T., Future Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 2039–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a.Quast H., Bieber L., Chem. Informationsdienst 1982, 13, 3253–3272; [Google Scholar]

- 17b.Tu Y., Zhong J., Wang H., Pan J., Xu Z., Yang W., Luo Y., J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2016, 59, 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatano B., Kubo D., Tagaya H., Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 54, 1304–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.

- 19a.Natte K., Neumann H., Beller M., Jagadeesh R. V., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6384–6394; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 6482–6492; [Google Scholar]

- 19b.Corma A., Navas J., Sabater M. J., Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1410–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakrabarti K., Maji M., Panja D., Paul B., Shee S., Das G. K., Kundu S., Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 4750–4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polidano K., Allen B. D. W., Williams J. M. J., Morrill L. C., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 6440–6445. [Google Scholar]

- 22.

- 22a.Quintard A., Rodriguez J., ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 28–30; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22b.Filonenko G. A., van Putten R., Hensen E. J., Pidko E. A., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1459–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sklyaruk J., Borghs J. C., El-Sepelgy O., Rueping M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 775–779; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 785–789. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mamidala R., Biswal P., Subramani M. S., Samser S., Venkatasubbaiah K., J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 10472–10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.o. Bettoni L., Seck C., Mbaye M. D., Gaillard S., Renaud J.-L., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3057–3061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruneau-Voisine A., Pallova L., Bastin S., César V., Sortais J.-B., Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 314–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukamoto Y., Itoh S., Kobayashi M., Obora Y., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3299–3303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polidano K., Williams J. M. J., Morrill L. C., ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 8575–8580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bettoni L., Gaillard S., Renaud J.-L., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 8404–8408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Latham D. E., Polidano K., Williams J. M., Morrill L. C., Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 7914–7918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.

- 31a.Kaithal A., Schmitz M., Hölscher M., Leitner W., ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 781–787; [Google Scholar]

- 31b.Kaithal A., van Bonn P., Holscher M., Leitner W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 215–220; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grigg R., Mitchell T. R., Sutthivaiyakit S., Tongpenyai N., Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 4107–4110. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roy B. C., Debnath S., Chakrabarti K., Paul B., Maji M., Kundu S., Org. Chem. Front. 2018, 5,1008–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul B., Shee S., Panja D., Chakrabarti K., Kundu S., ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2890–2896. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song D., Chen L., Li Y., Liu T., Yi X., Liu L., Ling F., Zhong W., Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 120–126. [Google Scholar]

- 36.

- 36a.Whitney S., Grigg R., Derrick A., Keep A., Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3299–3302; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36b.Chen S.-J., Lu G.-P., Cai C., RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 70329–70332. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer J., Elsinghorst P. W., Wüst M., J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 2011, 54, 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim S., Hong S. H., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 798–810. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W., Yang X., Zhou Z.-Z., Li C.-J., Chem 2017, 2, 688–702. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCallum T., Pitre S., Morin M., Scaiano J., Barriault L., Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 7412–7418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zidan M., Morris A. O., McCallum T., Barriault L., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sulikowski G. A., Sulikowski M. M., Haukaas M. H., Moon B., e-EROS, Iodomethane 2005, DOI:10.1002/047084289X.ri029m.pub2. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwa T., Boelhouwer C., Tetrahedron 1969, 25, 5771–5776. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yin Q. J., Chen Y. J., Zhou M., Jiang X. S., Wu J. J., Sun Y., Spectrochim. Acta Part A 2018, 204, 88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.

- 45a.Trost B. M., Toste F. D., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 5025–5036; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45b.Ikeda H., Akiyama K., Takahashi Y., Nakamura T., Ishizaki S., Shiratori Y., Ohaku H., Goodman J. L., Houmam A., Wayner D. D. M., Tero-Kubota S., Miyashi T., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 9147–9157; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]