Abstract

Wnt signaling plays a critical role during embryogenesis and is responsible for regulating the homeostasis of the adult stem cells and cells fate via a multitude of signaling pathways and associated transcription factors, receptors, effectors, and inhibitors. For this review, published articles were searched from PubMed Central, Embase, Medline, and Google Scholar. The search terms were Wnt, canonical, noncanonical, signaling pathway, β-catenin, environment, and heavy metals. Published articles on Wnt signaling pathways and heavy metals as contributing factors for causing diseases via influencing Wnt signaling pathways were included. Wnt canonical or noncanonical signaling pathways are the key regulators of stem cell homeostasis that control many mechanisms. There is an adequate balance between β-catenin dependent and independent Wnt signaling pathways and remain highly conserved throughout different development stages. Environmental heavy metal exposure may cause either inhibition or overexpression of any component of Wnt signaling pathways such as Wnt protein, transcription factors, receptors, ligands, or transducers to impede normal cellular function via negatively affecting Wnt signaling pathways. Environmental exposure to heavy metals potentially contributes to diseases via deregulated Wnt signaling pathways.

Key Words: β-catenin, Environmental, Heavy metals, Noncanonical, Wnt signaling

Introduction

Wnt signaling plays a critical role during embryogenesis. It is responsible for regulating the homeostasis of the adult stem cells and cells fate via a multitude of signaling pathways and associated transcription factors, receptors, effectors, and inhibitors (1, 2). The term Wnt is derived from the combination of two gene names of Drosophila melanogaster wingless (wg1) and mouse proto-oncogene (int-1) (3). After the discovery of int-1 as the integration site of mammary tumor virus inserted within mouse DNA, it is known that both Drosophila and mouse genes were homologs so named as Wnt and usually pronounced as ‘wint’ (4, 5). So far, nearly 19 human and mouse Wnt genes have been found, i.e. Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2b/I3, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt8a/d, Wnt8b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b/I2, Wnt11, Wnt14, Wnt15, and Wnt16. They are located either immediately adjacent to each other, transcribed in opposite directions, or clustered within the genome (6). Wnt signaling pathways are broadly characterized into two, i.e., canonical (β-catenin dependent) and noncanonical (β-catenin independent) pathways. In the same way, Wnt proteins are classified into canonical Wnts (e.g., Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt3, Wnt3a, and Wnt7a) and noncanonical Wnts (e.g., Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, and Wnt11) (7). These Wnt pathways are not autonomous as there is considerable overlap between them (4).

Canonical Wnt signaling pathways

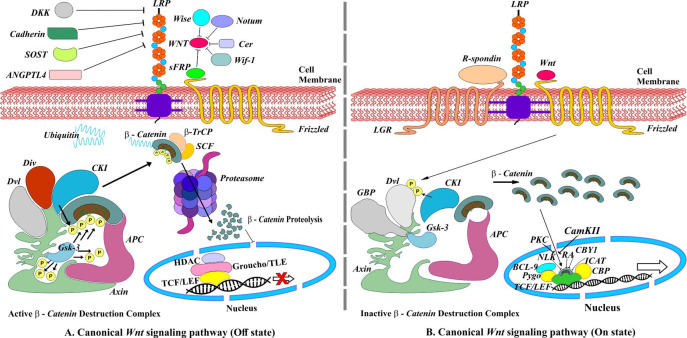

Canonical Wnt signaling or Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates cell fate determination during embryonic development. An absence of Wnt protein extracellularly results in activation of β-catenin destruction complex (βCDC), which consists of two scaffold proteins, i.e., axin and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and two kinases enzymes, i.e., casein kinase 1 (CK1) and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) that are responsible for the phosphorylation of β-catenin. Phosphorylated β-catenin is recognized by F-box protein β-transduction repeat-containing protein (β-Trcp), which along with Skp1-Cullin-F-box (SCF) ubiquitin ligase, target β-catenin for proteasomal degradation and prevents its translocation to the nucleus. In the absence of β-catenin, Groucho/TLE binds to T-cell factor/lymphoid enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factor recruiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) and thereby repressing transcription of many downstream genes (8-10) (Figure 1A). The presence of extracellular Wnt protein forms a Wnt-Fz-LRP6/5 complex upon binding to frizzled (fz) receptor and its co-receptors LRP6/5. The Wnt-Fz-LRP6/5 complex recruit cytosolic protein disheveled (Dv1), engaging Gsk3 binding protein (GBP) and axin along kinases enzymes CK1 and Gsk3, which in turn phosphorylate LRP6/5. The phosphorylated LRP6/5 acts as positive feedback causing sequestration of βCDC, consequently stabilizing and accumulating cytoplasmic β-catenin to enter into the nucleus and finally activating Wnt target gene expression (8, 9) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway. (A) Off state, absence of Wnt ligands leading to degradation of β-Catenin. (B) On state, the presence of Wnt ligands. R-spondins (RSPOs) is a Wnt signaling agonist that enhances Wnt signaling by binding to the members of the leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor family on the cell surface

Noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways

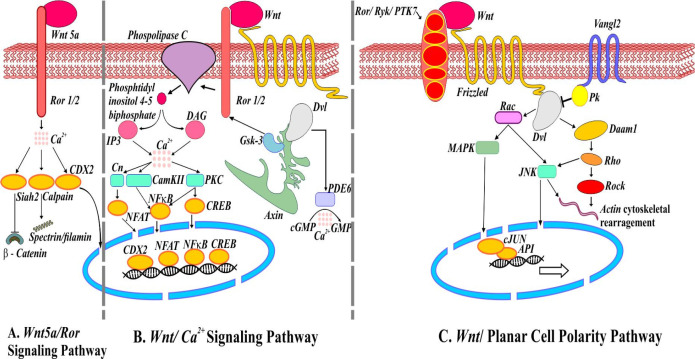

There are numerous noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways such as Wnt5a/Ror2, Wnt/Ca2+, Wnt/RAP1, Wnt/PKA, Wnt/Gsk3MT, Wnt/PKC, Wnt/RYK, and Wnt/mTOR (4). Wnt5a/Ror pathway is operating independently of β-catenin involves receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2. A protease called calpain in a Ca2+ dependent manner cleaves cytoskeleton proteins filamin and spectrin in these pathways. Also, Ca2+ leads to translocation of transcription factor caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) into the nucleus and transcribe downstream regulatory genes (Figure 2A) (4). In the Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway, the Wnt/Fz ligand-receptor and co-receptor Ror1/2 interact to activate the disheveled complex (Dvl), axin, and Gsk3 to phosphorylate Ror1/2. Phosphorylated Ror1/2 activates phospholipase C on the plasma membrane, causing intracellular signaling activation and formation of inositol 1,4,5 triphosphate (IP3). IP3 and cytoplasmic diacylglycerol (DAG) diffuse to stimulate the endoplasmic reticulum and release of Ca2+ that finally leads to the activation and translocation of transcription factors into the nucleus and change in the expression of downstream regulatory genes (Figure 2B). In the same way, the noncanonical Wnt/planar cell polarity pathway initiated upon recruitment of Dvl by Fz and its co-receptors Ror/Ryk/PTK7 leading to actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. The MAP kinase (MAPK) and C-jun-N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathways activate C-Jun and API transcription factors (Figure 2C) (11-13).

Figure 2.

Noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways. (A) Schematic representation of mediators involved in Wnt5a/Ror signaling pathways. Activation of ubiquitin ligase Shiah2 by Wnt5a represses Wnt/β-catenin. (B) Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway. Wnt/Fz interaction may activate phosphodiesterase 6 (PDE6) causing Ca2+ to decrease cGMP. The release of Ca2+ induces NFAT, NFкB, and CREB translocation into the nucleus regulating the expression of genes. (C) Wnt/Planar cell polarity pathway. Van Gogh (Vangle2) forms a complex with prickle (Pk) responsible for antagonizing PCP pathway. Wnt/Fz/ Ror/Ryk/PTK7/Dvl complex also recruits Dishevelled associated activator of morphogenesis (Daam1) involve in actin cytoskeleton rearrangement

Wnt antagonists

Numerous Wnt antagonists can negatively affect Wnt signaling pathway activation. They can be classified based on their different mechanisms of antagonizing ligand-receptor interaction. Members of secreted frizzled-related proteins (sFRPs), Wnt inhibitory factor 1 (Wif-1), Cerberus (Cer), notum SOST, Wise, and angiopoietin-like 4 (ANGPTL4) are Wnt antagonists that bind to Wnt ligand and block Wnt signaling pathways. Unlike other Wnt antagonists, dickkopf (Dkk) family members inhibit Wnt signaling by binding to Wnt receptors (14). The Wnt signaling components and their antagonists have a critical role in normal cell signaling. Many exogenous environmental factors such as heavy metals appeared to be associated with the pathological disease through altered Wnt signaling pathways (Table 1).

Table 1.

Heavy metal induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathways and associated risks

| Study (Animal/cells/tissue) | Mechanism | Outcomes | Risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathways and associated risks | |||||

| 1 | Human bronchial epithelial cells | Activates Rac1 on PKCα and Wnt5b-PKCα-mediated signaling pathway. | Activates cancer cell survival, proliferation and migration | Cancer | (27) |

| 2 | Adipose derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (ASCs) | Alters β-catenin levels and modulates TGFβ signaling pathway | Decreases osteogenic (Runx2, OPN and BGP) and chondrogenic (Sox9, DSPG3 and ACAN) genes expression | Induces changes in ASCs differentiation | (32) |

| 3 | Arsenic transformed cells | Activates β-catenin-VEGF pathway | Induces pro-angiogenic activity and promotes angiogenesis | Cancer | (20) |

| 4 | RIMM-18 cells | Alters Wnt/β-catenin, COX-2 and BMP signaling pathways | Decreases Wnt4, β-catenin, and BMP7 expression, increases Wt1, COX-2, MMP2 and 9 expression | Renal cancer | (18) |

| 5 | Human mesenchymal stem cells | Activates Wnt signaling pathway via upregulating Wnt3a and inhibits PPARγ, C/EBPα/β expression, and interaction between them | Reduces C/EBPs and PPARγ protein formation, inhibits adipogenesis and alters cell fate determination | Cancer | (28) |

| 6 | P19 stem cells | Repress Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway via decreasing expression of β-catenin and other muscle and neuron-specific transcription factors | Reduces myosin heavy chain and Tuj1 expression | Inhibits myogenesis and neurogenesis | (33) |

| 7 | CRL-1807 cells | Activate ROS mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway via increased expression of β-catenin and phospho-GSK | Decreases SOD and catalase level and generation of ROS | Tumorigenesis | (22) |

| Cadmium-induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathways and associated risks | |||||

| 8 | Mice fetus | Increases mRNA expression levels of Wnt/β-catenin target genes (Ahr, Arnt, NKx2.5, Ctnnb1 and Gsk3β) | Impairs the normal function of Ahr in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling during cardiogenesis, decreases total number of cardiomyocytes, swelling and apoptosis | Cardiovascular disease | (48) |

| 9 | Mice | Promote noncanonical Wnt signaling pathway and activates cdc42, increases C/EBPα while decreases Hhex expression | Impairs development of hematopoietic stem cells | Lymphopoiesis toxicity to the immune system |

(45) |

| 10 | Japanese medaka embryos | Dysregulated Wnt signaling pathway via overexpression of Wnt gene, repressed bax, rad51, while inhibiting transcription of NADH-dehydrogenase nd5 gene | Increases heart rate, impairs mitochondrial respiratory chain and spinal and cardiac deformities | Teratogenicity | (49) |

| 11 | Human osteoblastic Saos-2 cells | Induces nuclear translocation of β-catenin and increased expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes and caspase 3 activation | Induces cell proliferation and apoptosis | Bone diseases | (46) |

| 12 | Cd exposed RWPE1 cells | Dysregulated expression of ABCG2, OCT-4, and WNT-3 genes | Induces tumor growth and invasion | Oncogenic transformation | (55) |

| 13 | Chick embryo | Disrupt noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ pathway via downregulated Wnt11, PKCα and CaMKII gene expression | Induces ventral body wall defect | Omphalocele | (54) |

| 14 | Chick embryo | Disrupt noncanonical Wnt pathway via downregulated ROCK1 and 11 gene expression | Induces ventral body wall defect | Omphalocele | (51) |

| 15 | Mice kidney | Upregulates Wnts, Fz receptors, Twist, fibronectin, collagen1 and increased expression of Wnt target genes (c-Myc, cyclin D1, Abcb1b) | Induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition that leads to renal fibrosis | Renal cancer | (58) |

| 16 | Mice kidney and liver | Dysregulates Shh and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | Impairs thymocyte development | Cancer | (56) |

| 17 | BEAS-2B cells | Altered Wnt signaling pathway via upregulation of TCF4, Wnt7b and DIXDC1, UCHL1 | Initiates oncogenic transformation of lung epithelial cells | Tumorigenesis | (60) |

| Copper induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathways and associated risks | |||||

| 18 | Zebrafish | Downregulates Wnt signaling via elevated ROS | Suppresses embryonic motility | Suppress hatching | (61) |

| 19 | Zebrafish | Downregulate Wnt signaling | Inhibits specification and formation of three swimbladder layer in a stage-specific manner | Impairs swimbladder development and inflation | (62) |

| 20 | Zebrafish | Increases canonical Wnt signaling via decreasing Wnt5 and Wnt11 transcription, altering Cmlc2, dlx3, ntl, hgg, pax2 and 6 gene expression | Smaller head, eyes and delayed epiboly | Developmental toxicity | (63) |

| Lead-induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathways and associated risks | |||||

| 21 | Rats (Brian tissues) |

Suppresses protein expression of NR2B, Arc, Wnt7a and mRNA levels of Arc/Arg3.1 and Wnt7a | Decreases spine density and dentate gyrus regions | Memory and cognitive deficit | (70) |

| 22 | MC3T3-E1 subclone 14 cells | Inactivates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by regulating Wnt3a, Dkk-1, pGSK3β and β-catenin. | Changes bone mineral composition, inhibits skeletal growth and bone maturation | Inhibits osteoblastic differentiation | (77) |

| 23 |

MC3T3-E1 cells (Mice) |

Depresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling due to increased sclerostin via regulating TGFβ canonical signaling pathway | Loss of trabecular bone and reduces bone strength | Osteoporosis | (74) |

| 24 | Rats | Inhibits Wnt/β-catenin pathway via reducing β-catenin, Runx2 in stromal precursor cells and increasing PPAR-γ, sclerostin protein levels | Decreases osteoblastogenesis and increases adipogenesis | Osteoporotic-like phenotype and risk of fracture | (75) |

| 25 | Mice | Inhibits β-catenin activity | Alters progenitor cell differentiation, promotes osteoclastogenesis and suppress osteoblastogenesis | Skeletal deficits | (78) |

| 26 | Rats | metal-induced | Decreases spine density and alters synaptogenesis | Impairs spine outgrowth | (79) |

| 27 | Mice | Decreases β-catenin protein along with elevated Dkk-1 and sclerostin | Inhibits endochondral ossification causing immatures cartilage in the callus | Impairs fracture healing | (81) |

| 28 | Mice | Induces TGFβ, BMP, upregulates Sox-9, type 2 collagen, aggrecan, and induces NFkappaB signaling. | Induces chondrogenesis and nodule formation | Impairs fracture healing | (82) |

| Mercury induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathways and associated risks | |||||

| 29 | Zebrafish and human HepG2 cells | Deregulates Wnt signaling pathway, nuclear receptor and kinase activities | Triggers oxidative stress, intrinsic apoptotic pathway, gluconeogenesis, adipogenesis, mitochondrial dysfunction, endocrine disruption and metabolic disorders | Hepatotoxicity | (83) |

ACAN: Aggrecan; Ahr: Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; Arc/Arg3.1: Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein; BGP: Osteocalcin; BMP-4: Bone morphogenetic protein-4;BEAS-2B: Human lung epithelial cells; Dkk-1: Dickkopf-1; dlx3: distal-less homeobox 3; MMP7: Matrix metalloprotease 7; NR2B: NR2B subunit of NMDA receptor; ntl: no tail; OPN: Osteopontin; PPARδ: Peroxisome proliferator associated receptor δ; pGSK3β: Phosphorylation of GSK3β; Runx2: Runt-related transcription factor 2; RIMM-18 cells: Rat inducible metanephric mesenchyme-18; TGFβ: transforming growth factor-beta; Tuj1: Neuron-specific Class III β-tubulin; Sox9: SRY(sex-determining region Y)-Box 9; DSPG3: Dermatan sulfate proteoglycan 3; PKCα: Protein kinase Cα; VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; Wt1: Wilms’ tumor protein 1; RWPE1: immortalized non-tumorigenic human prostate epithelial cells.

Methods

This review aims to summarize different cellular mechanisms of Wnt signaling pathways and risks of diseases associated with dysregulated Wnt signaling pathways under the environmental exposure of heavy metals. A literature search was performed on different databases, including PubMed Central, Embase, Medline, and Google Scholar. Search terms were Wnt, canonical, noncanonical, signaling pathway, β-catenin, environment, and heavy metals used to sort the articles using Boolean operators. Published articles on Wnt signaling pathways were considered to summarize the cellular mechanism of canonical and noncanonical signaling pathways. At the same time, published articles on heavy metals as contributing factors for causing diseases via influencing Wnt signaling pathways were included to summarize environmental heavy metals’ effect via affecting the Wnt signaling pathway. Articles search remained limited to published articles in the English language only.

Environmental exposure of heavy metals and deregulated Wnt signaling pathways

Arsenic

Environmental arsenic (As) exposure induces malignant transformation (15-17). Animal studies revealed that As induces cancer cell survival, proliferation, and migration via modulating various signaling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin, BMP7, COX2, and influencing possible cross-talk among them (18). Angiogenesis contributes to carcinogenesis. It promotes tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis via β-catenin-VEGF pathway activation (19-21). A study on As-transformed human bronchial epithelial cells demonstrated As-induced an increase in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression, an angiogenic stimulating growth factor augments β-catenin activity that leads to angiogenesis and risk of carcinogenesis (20). A combination or single exposure of trivalent arsenic (As(III)) or hexavalent chromium promoted colorectal tumor in azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate treated mice. As was found to induce tumorigenesis due to the ROS-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. As. by generating ROS caused imbalance of oxidant and antioxidant enzymes along with declined superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase level, while increased expression of β-catenin, phospho-GSK, NADPH oxidase1 (NOX1), and 8-OHdG. Suggesting the role of As. exposure to the tumor size increase, incidence, and inflammation via modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (22). Noncanonical Wnts such as Wnt5b are known to be associated with cancer and disease pathologies (23, 24). Noncanonical Wnt signaling regulates cell migration via activation of protein kinase Cα (PKCα) (25). As exposure in the endothelial cells activates Rac1, i.e., required for remodeling and angiogenesis (26). Persistent As exposure upregulates Rac1, Wnt5b, and PKCα in As-transformed cells suggesting the role of noncanonical Wnt5b in PKC activation, cell migration, and cancer risk (27). Environmental As exposure also promotes cancer via altering cell fate determination through Wnt signaling pathway activation. In human mesenchymal stem cells, As exposure upregulates the Wnt3a protein and its mRNA, while it inhibits the expression of PPARγ, C/EBPα/β, and interaction between them, thus adversely affecting adipogenesis (28). Since PPARγ positively, while Wnt negatively regulates adipogenesis (28, 29). Moreover, CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBPs) expresses in adipocytes, whose inhibition impairs adipogenesis (30, 31). Another study demonstrated changes in the adipose-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (ASCs) differentiation in mice vide As induced altered canonical TGFβ signaling pathway and dose-dependent decline in the β-catenin (CTNNB1), osteogenic such as Runx2, OPN, and BGP along with and chondrogenic such as Sox9, DSPG3 and ACAN gene expression (32). As. exposure during embryogenesis of mice found to repress the muscle and neuron-related transcription factors, including Pax3, Myf5, MyoD, myogenin, neurogenin 1 and 2, and NeuroD. Such resulted in altered embryonic stem cells differentiation into skeletal muscles and neurons by repressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling (33). Moreover, chronic As exposure reported renal cancer via persistent decrease in β-catenin expression, declined Wnt4, BMP7 and duration dependent increase in Wilms’ tumor protein 1 (Wt1), Cox2, MMP2 and MMP9 expression in RIMM-18 cells (18). The canonical Wnt signaling pathway is vital to regulate nephron induction during the development of the kidney mediated by Wnt4 (34). BMP7 promotes kidney repair after obstruction-induced renal injury (35). Likewise, Wt1 is essential for normal kidney development (36). However, matrix metalloproteinases and Cox2 overexpression are associated with tumorigenesis (37, 38). Suggesting Wt-1, Wnt4, and BMP7 expression required in murine for normal kidney development. As exposure induces renal cancer via affecting BMP7, COX-2, and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways and possible cross-talk among them (18). The facts above suggested that As contributes to angiogenesis, carcinogenesis, and tumorigenesis via modulating directly or indirectly canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways.

Cadmium

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry designated cadmium (Cd) as a carcinogen due to its toxic effect via releasing ROS, impairing calmodulin activity, and potential of altering signal transduction networks including Wnt/β-catenin, and estrogen (39, 40). Cd adversely affects immunity, leading to osteoporosis and bone diseases via modulating hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and progenitor cells towards myelopoiesis (41, 42). Cdc42 is known to regulate HSCs rejuvenation and aging via the noncanonical Wnt5a signaling pathway (43, 44). While Cd exposure contributed toxicity to the immune system through impaired HSC function and activated the noncanonical Wnt5a-Cdc42 signaling pathway (45). Cd as an endocrine disruptor induces nuclear translocation of β-catenin, causing increased expression of Wnt/β-catenin target genes and caspase3 activation in human osteoblastic Saos-2 cells. This resulted in osteoblastic apoptosis and necrosis due to altered bone homeostasis and the future risk of bone diseases (46). Wnt/β-catenin signaling is vital for vascularization and angiogenesis (47). Environmental Cd exposure increases the risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) via abnormal Wnt/β-catenin signaling and aryl hydrocarbon receptor targets genes including Ahr, Arnt, Nkx2.5, Ctnnb1 and Gsk3β. Thus impairs the physiological function of Ahr in regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling that leads to the risk of CVDs (48). Likewise, Japanese medaka embryos reported Cd-induced adverse effects to the early life stages of fish via deregulated Wnt signaling pathway. There observed negative impacts on heartbeat, cardiac morphogenesis, spinal and cardiac deformities and risk of CVDs. There observed Cd induced suppressed expression of DNA repair rad51 gene, pro-apoptotic bax gene, impaired mitochondrial respiration via inhibiting transcription of NADH-dehydrogenase nd5 gene, and overexpression of cell proliferation and differentiation gene i.e. Wnt1 (49). Cd exposure also contributes to developmental defects among animals via modulating canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling pathways. Cd induces varying degree of adherens junction breakdown in the periderm, disturbing cadherins distribution and their intracellular associates via aberrant Wnt signaling pathway resulted in ventral body wall (VBW) defect (50). Rho-associated coiled-coil-containing protein kinase (ROCK) I and ROCK-II regulates signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton in Wnt non-canonical signaling pathway while it absence demonstrated ventral body wall (VBW) defect. A study on chick embryo demonstrated Cd induced downregulated ROCK I and ROCK-II genes expression during embryogenesis that resulted into VBW defect in chick embryo due disrupted Wnt non canonical signaling pathway (51). Noncanonical signaling pathways such as Wnt/Ca2+ regulates cell movement and adhesion during embryogenesis. Wnt is vital for PKC activation and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) in the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway requiring for actin-cytoskeleton organization and cell adhesion (52, 53). Cd treated chick embryos reported disrupt noncanonical Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway via downregulation of Wnt11, PKCα and CaMK11 gene expression during embryogenesis, thus impairing cell movement and adhesion and risk of VBW defects such as omphalocele (54). Cd reported carcinogenic activity via several mechanisms involving Wnts. Cd causes oncogenic transformation of normal cells by recruiting normal stem cells to an oncogenic phenotype by noncontagious carcinogen transformed epithelia via dysregulated Wnt3 expression (55). Thymocyte requires sonic hedgehog and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways for its maturation. Environmental Cd exposure in mice demonstrated decreased expression of these pathways in the thymus, thereby altering the expression of their target genes resulting in altered thymocyte development, increased cell proliferation and risk of cancer development (56). Cd exposure causes nuclear translocation of β-catenin. Cd also reduces the interaction between β-catenin and AJ components, including α-catenin and E-cadherin, thus increasing the binding of β-catenin with TCF4 transcription factor of Wnt signaling pathway and thus upregulates Wnt target genes including Abcd1b, c-Myc and cyclin D1. However, E-cadherin overexpression reduces Wnt signaling, cell proliferation and Cd toxicity (57). Chronic Cd exposure via drinking water causes transcriptional activation of Wnts and initiates epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), leading to renal fibrosis and the risk of developing cancer. Cd exposure considerably increases kidney Cd content which in turn increases expression of various Wnt ligands, including -3a,6,7a/b,9a/b,10a and 11 and upregulation of Fz1 to Fz10 except Fz3 receptor. Thus caused increased expression of Wnt target genes such as Abcd1b, c-Myc and cyclin D1 which promote cell proliferation, survival, migration and malignancy that leads to characteristic changes in the renal epithelial cells towards fibrosis and cancer through activated Wnt signaling pathway (58). These facts suggesting that Cd induces nephrocarcinogenesis via initiating Wnt signaling pathway, disrupting E-cadherin/β-catenin complex resulting in excessive nuclear translocation of β-catenin and TCF4 activation and upregulation of MDR1, Abcd1b, c-Myc and cyclin D1 genes (59).

Chromium

Chronic exposure of hexavalent chromium (Cr) on BEAS-2B human lung epithelial cells demonstrated changes in the various gene expression mostly related to cell adhesion, protein ubiquitination, oxidative stress, EMT, metastasis, and Wnt signaling. There also observed upregulation of potential lung cancer biomarker ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCHL1) that initiates the transformation of lung epithelial cells towards an early stage of lung cancer (60). Another study reported that chromium promoted colorectal cancer through ROS-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (22).

Copper

Copper (Cu) inhibits zebrafish egg hatching via suppressing embryonic motility (61). It also impairs zebrafish swimbladder development and inflation by inhibiting the specification and formation of three swimbladder layers in a stage-specific manner (62). These were due to Cu-induced generation of ROS and downregulation of Wnt signaling (61, 62). However, Wnt agonist 6-bromoindirubin-3’-oxime (BIO) was found to alleviate the suppressing effect of Cu on egg hatching and swimbladder development (61). Cu induces toxicity to the early development of zebrafish (63). Transcription factors such as Ntl required for the development of posterior body structures (64), Dlx regulates intracellular signaling between neural and non-neural ectoderm and is vital for patterning adjacent cell fate (65), Hgg regulates the position of the anterior prechordal mesoderm (66), Wnt5 and 11 required for convergence and extension movement during various stages of gastrulation (67). Pax2 and 6 regulate CNS development (68), and cardiac myosin light chain 2 (Cmlc2) is an essential component of thick myofilament assembly while, its expression inhibits the cardiac looping resulting in impaired cardiac development (63). Environmental Cu exposure demonstrated toxicity to zebrafish by reducing the size of the head and eyes, aberrantly affect the dorsoventral patterning, cell migration of gastrulation, and prevent looping of heart tube during cardiogenesis. Such phenotypes were due to altered gene expression of ntl, dlx3, and hgg during gastrulation, Cmlc2 expression, and decreased pax2 and pax6 gene expressions along with decreased Wnt5 and 11 transcription factors (63).

Lead

Environmental lead (Pb) exposure Pb induces neurotoxic and extra neurotoxic pathophysiological outcome that tends to sustain and maintain for a lifetime (69). Developmental chronic Pb exposure through lactation among rat pups demonstrated impaired learning and memory (70). The role of activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc/Arg3.1) and hippocampal Wnt7a is known to regulate dendritic spines’ formation and structure (71, 72). Dendritic spines are essential for excitatory synaptic transmission, and any change in their construction, numbers, and morphology will affect synaptic plasticity and spatial learning (73). Chronic Pb exposure reported the dose-dependent reduction of spine density and dentate gyrus region causing dysregulated synaptogenesis, impaired Arc/Arg3.1 and hippocampal Wnt7a ultimately resulted in impaired learning and memory among adult rats (70). Several animal studies reported Pb-induced bone pathologies such as osteoporosis, impaired healing of fractured bone, skeletal deficit growth, and development due to Pb-induced modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and their related key regulators (74, 75). It is well known that Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates osteoblastic anabolic function in bone formation (76). Murine studies reported declined osteoblastogenesis due to Pb exposure (74, 75). This is due to Pb-induced sclerostin production via TGFβ canonical signaling pathway (74). Even low Pb exposure increases peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) and sclerostin while decreases β-catenin and Runx2 in stromal precursor cells, thereby disrupt bone homeostasis via inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (75). Likewise, the subtoxic Pb concentration was found to decrease alkaline phosphatase (ALP), type 1 collagen (COL1), osteocalcin (OC), and Runx2 impairing regulation of Wnt3a, Dkk-1, pGSK3β, and β-catenin (77). Environmental Pb exposure also alters progenitor cell differentiation via promoting osteoclastogenesis and suppressing osteoblastogenesis, resulting in reduced trabecular bone quality, bone strength, and spine density due to reduced Wnt signaling, thereby negatively impacting spine outgrowth (78, 79). Wnt signaling is also an important anabolic pathway required for chondrocyte maturation and endochondral ossification (80). While Pb is the potent inhibitor of endochondral ossification due to the deficit Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway that delays bone mineralization, causing the development of immature cartilage in the callus, thus impair healing of fractured bone (81). Pb induced upregulation of aggrecan, Sox-9 and type 2 collagen modulate multiple signaling pathways such as AP-1, BMP, and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kappaB) and TGFβ, thus induce chondrogenesis (82). Facts as mentioned earlier suggest that Pb exposure via impairing the function of several key regulators of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways suppresses bone nodule formation, bone mineralization, skeletal growth and bone maturation, resulting into trabecular bone loss and decrease in bone strength that leads to osteoporotic like phenotype and risk of fracture later in life.

Mercury

Mercury (Hg) induces liver toxicity employing several processes associated with oxidative stress-mediated cell death, dysregulation of kinases including Gsk3 during Wnt signaling pathways. This gluconeogenesis and adipogenesis resulted in mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic disruption, and endocrine disruption (83).

Conclusion

Wnt signaling pathways are vital for normal cellular functions and are sensitive to environmental exposure of heavy metals such as As, Cd, Cu, Pb, and Hg. Heavy metal exposure deregulates the Wnt signaling pathway that ultimately contributes to the initiation of various diseases and even cancer. Heavy metal-induced deregulated Wnt signaling pathway contributes to cancer and tumor development, toxicity to system organs such as kidney and liver, impairs normal bone and skeleton growth, and contributes toxicity to marine life. However, more research is warranted involving humans and exposure to other heavy metals to rule out their exact mechanism of action and possible means of controlling them to save humans, animals, and marine life.

Author’s contributions

All authors contributed equally to this review.

References

- 1.Veeman MT, Axelrod JD, Moon RT. A Second Canon: Functions and Mechanisms of β-Catenin-Independent Wnt Signaling. Dev. Cell . 2003;5:367–77. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pukrop T, Binder C. The complex pathways of Wnt 5a in cancer progression. J. Mol. Med. . 2008;86:259–66. doi: 10.1007/s00109-007-0266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma RP, Chopra VL. Effect of the Wingless (wg1) mutation on wing and haltere development in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev. Biol. . 1976;48:461–5. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De A. Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway: a brief overview. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. . 2011;43:745–56. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nusse R, Brown A, Papkoff J, Scambler P, Shackleford G, McMahon A, Moon R, Varmus H. A new nomenclature for int-1 and related genes: The Wnt gene family. Cell. . 1991;64 doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90633-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller JR. The Wnts. Genome Biol. . 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2001-3-1-reviews3001. Reviews3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamura M, Nemoto E. Role of the Wnt signaling molecules in the tooth. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. . 2016;52:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jdsr.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacDonald BT, Tamai K, He X. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms and diseases. Dev. Cell . 2009;17:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Kappel EC, Maurice MM. Molecular regulation and pharmacological targeting of the beta-catenin destruction complex. Br. J. Pharmacol. . 2017;174:4575–88. doi: 10.1111/bph.13922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valenta T, Hausmann G, Basler K. The many faces and functions of β-catenin. EMBO J. . 2012;31:2714–36. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson DJ, Long DA, Dean CH. Planar cell polarity in organ formation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. . 2018;55:96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokol SY. Spatial and temporal aspects of Wnt signaling and planar cell polarity during vertebrate embryonic development. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. . 2015;42:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pataki CA, Couchman JR, Brabek J. Wnt Signaling Cascades and the Roles of Syndecan Proteoglycans. J. Histochem. Cytochem. . 2015;63:465–80. doi: 10.1369/0022155415586961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawano Y, Kypta R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J. Cell Sci. . 2003;116:2627. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Zhao Y, Smith E, Goodall GJ, Drew PA, Brabletz T, Yang C. Reversal and prevention of arsenic-induced human bronchial epithelial cell malignant transformation by microRNA-200b. Toxicol. Sci. . 2011;121:110–22. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu Y, Li Y, Pang Y, Ling M, Shen L, Yang X, Zhang J, Zhou J, Wang X, Liu Q. EMT and stem cell-like properties associated with HIF-2α are involved in arsenite-induced transformation of human bronchial epithelial cells. PloS one. . 2012;7:e37765–e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang R, Li Y, Xu Y, Zhou Y, Pang Y, Shen L, Zhao Y, Zhang J, Zhou J, Wang X. EMT and CSC-like properties mediated by the IKKβ/IκBα/RelA signal pathway via the transcriptional regulator, Snail, are involved in the arsenite-induced neoplastic transformation of human keratinocytes. Arch. Toxicol. . 2013;87:991–1000. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0933-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokar EJ, Person RJ, Sun Y, Perantoni AO, Waalkes MP. Chronic exposure of renal stem cells to inorganic arsenic induces a cancer phenotype. Chem. Res. Toxicol. . 2013;26:96–105. doi: 10.1021/tx3004054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weis SM, Cheresh DA. Tumor angiogenesis: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Nat. Med. . 2011;17:1359. doi: 10.1038/nm.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Z, Humphries B, Xiao H, Jiang Y, Yang C. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in arsenic-transformed cells promotes angiogenesis through activating β-catenin-vascular endothelial growth factor pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. . 2013;271:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsen JJ, Pohl SÖ-G, Deshmukh A, Visweswaran M, Ward NC, Arfuso F, Agostino M, Dharmarajan A. The Role of Wnt Signalling in Angiogenesis. Clin. Biochem. Rev. . 2017;38:131–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Mandal AK, Saito H, Pulliam JF, Lee EY, Ke ZJ, Lu J, Ding S, Li L, Shelton BJ, Tucker T, Evers BM, Zhang Z, Shi X. Arsenic and chromium in drinking water promote tumorigenesis in a mouse colitis-associated colorectal cancer model and the potential mechanism is ROS-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. . 2012;262:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugimura R, Li L. Noncanonical Wnt signaling in vertebrate development, stem cells and diseases. Birth Defects Res. C: Embryo Today . 2010;90:243–56. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harada T, Yamamoto H, Kishida S, Kishida M, Awada C, Takao T, Kikuchi A. Wnt5b-associated exosomes promote cancer cell migration and proliferation. Cancer Sci. . 2017;108:42–52. doi: 10.1111/cas.13109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luna-Ulloa LB, Hernández-Maqueda JG, Castañeda-Patlán MC, Robles-Flores M. Protein kinase C in Wnt signaling: Implications in cancer initiation and progression. IUBMB Life. . 2011;63:915–21. doi: 10.1002/iub.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith KR, Klei LR, Barchowsky A. Arsenite stimulates plasma membrane NADPH oxidase in vascular endothelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. . 2001;280:L442–L9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.3.L442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Humphries B, Xiao H, Jiang Y, Yang C. MicroRNA-200b suppresses arsenic-transformed cell migration by targeting protein kinase Cα and Wnt5b-protein kinase Cα positive feedback loop and inhibiting Rac1 activation. J. Bio. Chem. . 2014;289:18373–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.554246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav S, Anbalagan M, Shi Y, Wang F, Wang H. Arsenic inhibits the adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells by down-regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and CCAAT enhancer-binding proteins. Toxicol. In Vitro. . 2013;27:211–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma X, Wang D, Zhao W, Xu L. Deciphering the Roles of PPARγ in Adipocytes via Dynamic Change of Transcription Complex. Front. Endocrinol. . 2018;9:473. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urs S, Venkatesh D, Tang Y, Henderson T, Yang X, Friesel RE, Rosen CJ, Liaw L. Sprouty1 is a critical regulatory switch of mesenchymal stem cell lineage allocation. FASEB J. . 2010;24:3264–73. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-155127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bezy O, Vernochet C, Gesta S, Farmer SR, Kahn CR. TRB3 Blocks Adipocyte Differentiation through the Inhibition of C/EBPβ Transcriptional Activity. Mol. Cell Biol. . 2007;27:6818–31. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00375-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shearer JJ, Figueiredo Neto M, Umbaugh CS, Figueiredo ML. In Vivo Exposure to Inorganic Arsenic Alters Differentiation-Specific Gene Expression of Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in C57BL/6J Mouse Model. Toxicol. Sci. . 2017;157:172–82. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong GM, Bain LJ. Arsenic exposure inhibits myogenesis and neurogenesis in P19 stem cells through repression of the β-catenin signaling pathway. Toxicol. Sci. . 2012;129:146–56. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park JS, Valerius MT, McMahon AP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates nephron induction during mouse kidney development. Development. . 2007;134:2533–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.006155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manson SR, Niederhoff RA, Hruska KA, Austin PF. The BMP-7-Smad1/5/8 pathway promotes kidney repair after obstruction induced renal injury. J. Urol. . 2011;185:2523–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hohenstein P, Pritchard-Jones K, Charlton J. The yin and yang of kidney development and Wilms’ tumors. Genes Dev. . 2015;29:467–82. doi: 10.1101/gad.256396.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. . 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pang LY, Hurst EA, Argyle DJ. Cyclooxygenase-2: A Role in Cancer Stem Cell Survival and Repopulation of Cancer Cells during Therapy. Stem Cells Int. . . 2016;2016:2048731. doi: 10.1155/2016/2048731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chmielowska-Bąk J, Izbiańska K, Deckert J. The toxic Doppelganger: on the ionic and molecular mimicry of cadmium. Acta Biochim. Pol. . 2013;60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thévenod F, Lee W-K. Cadmium and cellular signaling cascades: interactions between cell death and survival pathways. Arch. Toxicol. . 2013;87:1743–86. doi: 10.1007/s00204-013-1110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Yu X, Sun S, Li Q, Xie Y, Li Q, Zhao Y, Pei J, Zhang W, Xue P. Cadmium modulates hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and skews toward myelopoiesis in mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. . 2016;313:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodríguez J, Mandalunis PM. A Review of Metal Exposure and Its Effects on Bone Health. J. Toxicol. . 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/4854152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Florian MC, Dörr K, Niebel A, Daria D, Schrezenmeier H, Rojewski M, Filippi M-D, Hasenberg A, Gunzer M, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. Cdc42 activity regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging and rejuvenation. Cell Stem Cell. . 2012;10:520–30. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Florian MC, Nattamai KJ, Dörr K, Marka G, Überle B, Vas V, Eckl C, Andrä I, Schiemann M, Oostendorp RA. A canonical to non-canonical Wnt signalling switch in haematopoietic stem-cell ageing. Nature. . 2013;503 doi: 10.1038/nature12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y, Li Q, Yang Z, Shao Y, Xue P, Qu W, Jia X, Cheng L, He M, He R. Cadmium Activates Noncanonical Wnt Signaling to Impair Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function in Mice. Toxicol. Sci. . 2018;165:254–66. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfy166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papa V, Bimonte V, Wannenes F, D’Abusco A, Fittipaldi S, Scandurra R, Politi L, Crescioli C, Lenzi A, Di Luigi L. The endocrine disruptor cadmium alters human osteoblast-like Saos-2 cells homeostasis in vitro by alteration of Wnt/β-catenin pathway and activation of caspases. J. Endocrinol. Invest. . 2015;38:1345–56. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0380-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parmalee NL, Kitajewski J. Wnt signaling in angiogenesis. Curr. Drug Targets. . 2008;9:558–64. doi: 10.2174/138945008784911822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Omidi M, Niknahad H, Noorafshan A, Fardid R, Nadimi E, Naderi S, Bakhtari A, Mohammadi-Bardbori A. Co-exposure to an Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Endogenous Ligand, 6-Formylindolo[3,2-b]carbazole (FICZ), and Cadmium Induces Cardiovascular Developmental Abnormalities in Mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. . 2019;187:442–51. doi: 10.1007/s12011-018-1391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barjhoux I, Gonzalez P, Baudrimont M, Cachot J. Molecular and phenotypic responses of Japanese medaka (Oryzias latipes) early life stages to environmental concentrations of cadmium in sediment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. . 2016;23:17969–81. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6995-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thompson J, Wong L, Lau PS, Bannigan J. Adherens junction breakdown in the periderm following cadmium administration in the chick embryo: distribution of cadherins and associated molecules. Reprod. Toxicol. . 2008;25:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doi T, Puri P, Bannigan J, Thompson J. Downregulation of ROCK-I and ROCK-II gene expression in the cadmium-induced ventral body wall defect chick model. Pediatr. Surg. Int. . 2008;24:1297–301. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sheldahl LC, Slusarski DC, Pandur P, Miller JR, Kühl M, Moon RT. Dishevelled activates Ca2+ flux, PKC and CamKII in vertebrate embryos. J. Cell Biol. . 2003;161:769–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cai H, Liu D, Garcia JGN. CaM Kinase II-dependent pathophysiological signalling in endothelial cells. Cardiovas. Res. . 2007;77:30–4. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doi T, Puri P, Bannigan J, Thompson J. Disruption of noncanonical Wnt/CA2+ pathway in the cadmium-induced omphalocele in the chick model. J. Pediatr. Surg. . 2010;45:1645–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Y, Tokar EJ, Person RJ, Orihuela RG, Ngalame NNO, Waalkes MP. Recruitment of normal stem cells to an oncogenic phenotype by noncontiguous carcinogen-transformed epithelia depends on the transforming carcinogen. Environ. Health Perspect. . 2013;121:944–50. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1306714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hanson ML, Brundage KM, Schafer R, Tou JC, Barnett JB. Prenatal cadmium exposure dysregulates sonic hedgehog and Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the thymus resulting in altered thymocyte development. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. . 2010;242:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chakraborty PK, Lee W-K, Molitor M, Wolff NA, Thévenod F. Cadmium induces Wnt signaling to upregulate proliferation and survival genes in sub-confluent kidney proximal tubule cells. Mol. Cancer. . 2010;9:102. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chakraborty PK, Scharner B, Jurasovic J, Messner B, Bernhard D, Thévenod F. Chronic cadmium exposure induces transcriptional activation of the Wnt pathway and upregulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers in mouse kidney. Toxicol. Lett. . 2010;198:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thevenod F, Chakraborty P. The role of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in renal carcinogenesis: lessons from cadmium toxicity studies. Curr. Mol. Med. . 2010;10:387–404. doi: 10.2174/156652410791316986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park S, Zhang X, Li C, Yin C, Li J, Fallon JT, Huang W, Xu D. Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals an altered gene expression pattern as a result of CRISPR/cas9-mediated deletion of Gene 33/Mig6 and chronic exposure to hexavalent chromium in human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. . 2017;330:30–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y, Zhang R, Sun H, Chen Q, Yu X, Zhang T, Yi M, Liu JX. Copper inhibits hatching of fish embryos via inducing reactive oxygen species and down-regulating Wnt signaling. Aquat. Toxicol. . 2018;205:156–64. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu J, Zhang R, Zhang T, Zhao G, Huang Y, Wang H, Liu JX. Copper impairs zebrafish swimbladder development by down-regulating Wnt signaling. Aquat. Toxicol. . 2017;192:155–64. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu J, Zhang Q, Li X, Zhan S, Wang L, Chen D. The effects of copper oxide nanoparticles on dorsoventral patterning, convergent extension, and neural and cardiac development of zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. . 2017;188:130–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harvey SA, Tümpel S, Dubrulle J, Schier AF, Smith JC. no tail integrates two modes of mesoderm induction. Development. . 2010;137:1127–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.046318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Woda JM, Pastagia J, Mercola M, Artinger KB. Dlx proteins position the neural plate border and determine adjacent cell fates. Development. . 2003;130:331–42. doi: 10.1242/dev.00212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gonsar N, Coughlin A, Clay-Wright JA, Borg BR, Kindt LM, Liang JO. Temporal and spatial requirements for Nodal-induced anterior mesendoderm and mesoderm in anterior neurulation. Genesis. . 2016;54:3–18. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kilian B, Mansukoski H, Barbosa FC, Ulrich F, Tada M, Heisenberg CP. The role of Ppt/Wnt5 in regulating cell shape and movement during zebrafish gastrulation. Mech. Dev. . . 2003;120:467–76. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Blake JA, Ziman MR. Pax genes: regulators of lineage specification and progenitor cell maintenance. Development. . 2014;141:737. doi: 10.1242/dev.091785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khalid M, Abdollahi M. Epigenetic modifications associated with pathophysiological effects of lead exposure. J. Environ. Sci. Health C. . 2019:1–53. doi: 10.1080/10590501.2019.1640581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang QQ, Xue WZ, Zou RX, Xu Y, Du Y, Wang S, Xu L, Chen YZ, Wang HL, Chen XT. beta-Asarone Rescues Pb-Induced Impairments of Spatial Memory and Synaptogenesis in Rats. PLoS One. . 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Peebles CL, Yoo J, Thwin MT, Palop JJ, Noebels JL, Finkbeiner S. Arc regulates spine morphology and maintains network stability in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. . 2010;107:18173–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006546107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ciani L, Boyle KA, Dickins E, Sahores M, Anane D, Lopes DM, Gibb AJ, Salinas PC. Wnt7a signaling promotes dendritic spine growth and synaptic strength through Ca²⁺/Calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. . 2011;108:10732–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018132108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tønnesen J, Nägerl UV. Dendritic Spines as Tunable Regulators of Synaptic Signals. Front. Psychiatry. . 2016;7:101. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Beier EE, Sheu TJ, Dang D, Holz JD, Ubayawardena R, Babij P, Puzas JE. Heavy Metal Ion Regulation of Gene Expression: Mechanisms by which Lead Inhibits osteoblastic bone-forming activity through modulation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J. Bio. Chem. . 2015;290:18216–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.629204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Beier EE, Maher JR, Sheu TJ, Cory-Slechta DA, Berger AJ, Zuscik MJ, Puzas JE. Heavy metal lead exposure, osteoporotic-like phenotype in an animal model, and depression of Wnt signaling. Environ. Health Perspect. . 2013;121:97–104. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duan P, Bonewald LF. The role of the wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in formation and maintenance of bone and teeth. Int. J. Biochem. Cell B. . 2016;77:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sun K, Mei W, Mo S, Xin L, Lei X, Huang M, Chen Q, Han L, Zhu X. Lead exposure inhibits osteoblastic differentiation and inactivates the canonical Wnt signal and recovery by icaritin in MC3T3-E1 subclone 14 cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. . 2019;303:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2019.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beier EE, Inzana JA, Sheu TJ, Shu L, Puzas JE, Mooney RA. Effects of Combined Exposure to Lead and High-Fat Diet on Bone Quality in Juvenile Male Mice. Environ. Health Perspect. . 2015;123:935–43. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hu F, Xu L, Liu ZH, Ge MM, Ruan DY, Wang HL. Developmental lead exposure alters synaptogenesis through inhibiting canonical Wnt pathway in vivo and in vitro. PloS one. . 2014;9:e101894–e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang Y, Li YP, Paulson C, Shao JZ, Zhang X, Wu M, Chen W. Wnt and the Wnt signaling pathway in bone development and disease. Front. Biosci. . 2014;19:379–407. doi: 10.2741/4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beier EE, Sheu TJ, Buckley T, Yukata K, O’Keefe R, Zuscik MJ, Puzas JE. Inhibition of beta-catenin signaling by Pb leads to incomplete fracture healing. J. Orthop. Res. . . 2014;32:1397–405. doi: 10.1002/jor.22677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zuscik MJ, Ma L, Buckley T, Puzas JE, Drissi H, Schwarz EM, O’Keefe RJ. Lead induces chondrogenesis and alters transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein signaling in mesenchymal cell populations. Environ. Health Perspect. . 2007;115:1276–82. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ung CY, Lam SH, Hlaing MM, Winata CL, Korzh S, Mathavan S, Gong Z. Mercury-induced hepatotoxicity in zebrafish: in-vivo mechanistic insights from transcriptome analysis, phenotype anchoring and targeted gene expression validation. BMC Genomics . 2010;11:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]