PURPOSE:

Telehealth has been an integral response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, no studies to date have examined the utility and safety of telehealth for oncology patients undergoing systemic treatments. Concerns of the adequacy of virtual patient assessments for oncology patients include the risk and high acuity of illness and complications while on treatment.

METHODS:

We assessed metrics related to clinical efficiency and treatment safety after propensity matching of newly referred patients starting systemic therapy where care was in large part replaced by telehealth between March and May 2020, and 206 newly referred patients from a similar time period in 2019 where all encounters were in-person visits.

RESULTS:

Patient-initiated telephone encounters that capture care or effort outside of visits, time to staging imaging, and time to therapy initiation were not significantly different between cohorts. Similarly, 3 month all-cause or cancer-specific emergency department presentations and hospitalizations, and treatment delays were not significantly different between cohorts. There were substantial savings in travel time with virtual care, with an average of 211.4 minutes saved per patient over a 3-month interval.

CONCLUSION:

Our results indicate that replacement of in-person care with virtual care in oncology does not lead to worse efficiency or outcomes. Given the increased barriers to patients seeking oncology care during the pandemic, our study indicates that telehealth efforts may be safely intensified. These findings also have implications for the continual use of virtual care in oncology beyond the pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused large shifts in the delivery of health care, which is most evident in the widespread adoption of telemedicine.1,2 For instance, on the basis of data from four of the largest telehealth providers in the United States, there was a > 50% increase in virtual encounters in the first quarter of 2020 including a 154% increase noted by the last week of March 2020.1 Although the adoption of telemedicine has not been uniform across the United States, the use of virtual care has increased across all specialties, including specialties where telemedicine was previously infrequently used such as in oncology.3,4

The clinical benefit of telemedicine on patient outcomes and satisfaction for the management of chronic medical conditions including hypertension, heart failure, cystic fibrosis, substance abuse, and mental health disorders has been substantiated across multiple studies.5-8 Other benefits of telemedicine include the reduction in health care costs and patient transportation, while potentially increasing access to care.6,7 However, research on the impact of telemedicine on clinical outcomes and safety in oncology is lacking. In particular, the use of telehealth in oncology is associated with concerns of the adequacy of virtual patient assessments including the evaluation of performance status, complexity of therapies used, and the high acuity of illness and complications while on treatment.4 Indeed, an analysis of malpractice claims related to telemedicine indicates that inadequate documentation and faulty triage were the most frequent medical errors.9

The purpose of our study was to determine whether practice efficiency and safety in oncology were affected by the substitution of in-person visits with telehealth at our institution. We assessed 3-month outcomes including patient-initiated telephone encounters, time to staging imaging, and time to therapy initiation, all-cause or cancer-specific emergency department presentations and hospitalizations, and treatment delays between patients after propensity matching who received treatment through in-person visits or virtual visits.

METHODS

Our institution began using telehealth in March 2020 at the discretion of the treating physician. We assessed consecutively referred patients to medical oncology clinics between March and May 2020 (virtual) who had at least one telehealth visit, were determined to require timely systemic therapy, and received at least one cycle of intravenous therapy. To account for seasonal variation, the baseline cohort included all consecutively referred patients between February and June 2019 (in-person). Treating providers were restricted to 21 medical oncologists who treated patients across both time periods. Patients were excluded if they were enrolled in clinical trials, required inpatient treatment, or had any necessary or elective delays before starting systemic therapy. Necessary or elective delays were assessed by the consensus of two clinicians as any delay that could only be attributed to patient preference or necessary medical treatment. For instance, if the patient needed to complete radiation before systemic therapy, this was considered a necessary delay. Elective delays attributed to patient preference were based on any documentation indicating that the patient requested a treatment start date beyond 4 weeks of the initial visit. Any delays attributed to the timing of physician orders, scheduling of imaging or treatment by the clinic, or any other provider or clinic action were considered to be non-necessary and nonelective delays. There were no environmental factors during the time periods analyzed that affected our results. Clinical actions and outcomes from the date of the initial visit to 3 months after were assessed from the medical record. To gauge efficiency, we assessed patient-initiated telephone encounters, time to staging imaging, and time to therapy initiation. To gauge safety, we assessed all-cause or cancer-specific emergency department presentations and hospitalizations, and treatment delays. Other clinical practice variables assessed included referrals to palliative care and molecular profiling for advanced cancers. These variables were selected as they could be objectively determined and because they resemble quality metrics that ultimately affect the patient experience, which are commonly used in program evaluation. Time to staging imaging was determined as the number of days between the date of the first encounter and the date of imaging. Time to therapy initiation was determined as the number of days between the date of the first encounter and the date of the first treatment infusion. Dates of imaging and treatment were abstracted from discrete data fields in the electronic medical record.

To compare the virtual and in-person cohorts, a 1-to-1 propensity-matched analysis without replacement was applied using the nearest neighbor method within a caliper of 0.1. Propensity scores were calculated using logistic regression modeling, and patients were matched on age, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score, cancer type, stage, and Charlson Comorbidity Index. To calculate potential miles of travel avoided and potential time saved, we measured the number of miles traveled in a round trip per visit on the basis of the shortest driving distance determined from Google Maps between the UT Southwestern Cancer Center and the patients' recorded residence. This study was undertaken as a quality improvement program to increase telehealth utility and reviewed by the UT Southwestern Human Research Protection Program, which determined that institutional review board approval was not required because it did not meet the federal definition of research given in 45 Code of Federal Regulations 46.

RESULTS

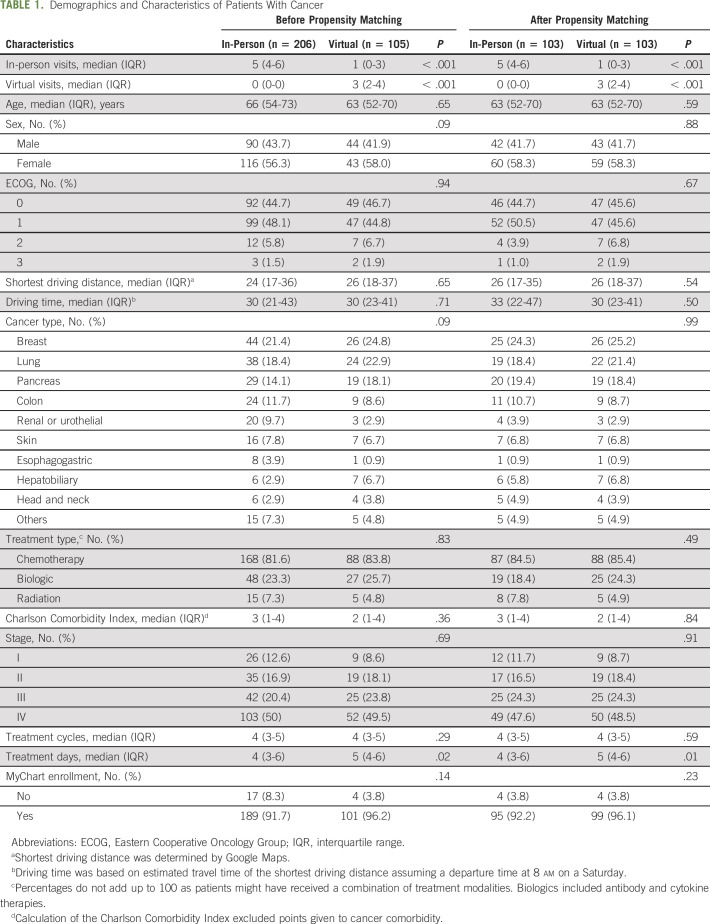

Demographics and characteristics including number of visits, driving distance from home, comorbidities, and number of treatment cycles and days for unmatched and matched cohorts are shown in Table 1. A precipitous decline in the number of new referrals to the institution at the beginning of the pandemic accounted for the nearly 50% decrease in the size of the unmatched virtual cohort compared with the unmatched in-person cohort. In the virtual cohort, two thirds of all encounters were telehealth and approximately 26% of patients were receiving virtual care exclusively. Covariate differences between cohorts were compared before and after matching in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Characteristics of Patients With Cancer

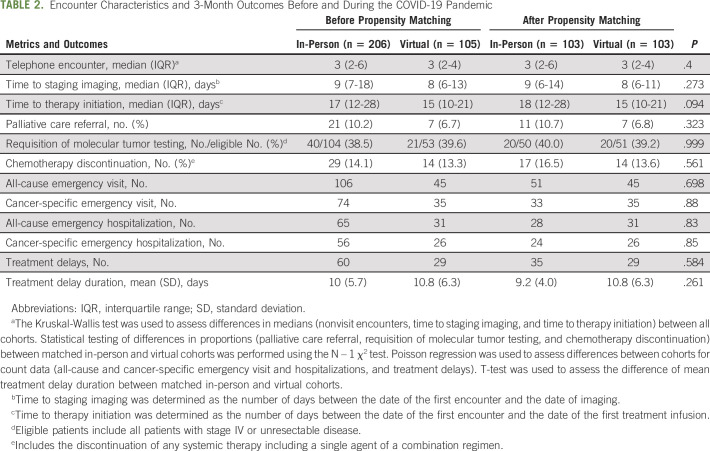

Nonvisit telephone encounters, which capture care or effort outside of visits and rates of molecular testing of advanced cancers, were not significantly different between cohorts (Table 2). Median times to staging studies for matched in-person and virtual patients were 9 and 8 days, respectively, and this was not significantly different (Table 2). Similarly, median times to initiation of systemic treatment were 18 and 15 days, respectively, and this was not significantly different (Table 2). There was a trend toward decreased referrals to palliative care in unmatched and unmatched cohorts, but this was not statistically significant (Table 2). There were no discernable differences in 3-month clinical outcomes among cohorts including rates of chemotherapy discontinuation and all-cause or cancer-specific emergency visits or hospitalizations (Table 2). In addition, the number of treatment delays and mean duration of delays were similar across cohorts (Table 2). Notably, no patients in either cohort were hospitalized for COVID-19 during the 3-month follow-up period.

TABLE 2.

Encounter Characteristics and 3-Month Outcomes Before and During the COVID-19 Pandemic

As a result of telehealth, the virtual cohort potentially avoided 20,198 total miles and 192.2 miles per patient of travel. This was equivalent to a potential savings of 22,192 total minutes and 211.4 minutes per patient.

DISCUSSION

Although telemedicine use is now widespread, its deployment in oncology as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic was done without a thorough investigation of its impact on clinical outcomes. Our institution's experience suggests that virtual care in oncology does not lead to worse efficiency or outcomes when compared with in-person care. This is particularly notable, given that oncology patients undergoing treatment are at high risk of numerous complications and toxicities.

Telemedicine as a complement to conventional medical care has been associated with improved clinical outcomes, including a reduction in mortality and hospitalizations among patients with heart failure.10,11 However, the increasing utilization of telemedicine raises concerns related to privacy, security, and patient safety.12 No studies to date have specifically assessed the safety of telemedicine, although a retrospective analysis of 32 telemedicine-related malpractice lawsuits revealed that 60% of claims were settled in favor of the plaintiff.9 Further research is necessary to identify errors and deficits in medical care that may be more prevalent in virtual care in oncology and other disciplines. It is also unknown whether utilization of telemedicine by physicians is selective and how practice behaviors affect telemedicine safety.

The design of our study does not allow us to exclude the impact of the pandemic as a confounding factor. Safety concerns and travel restrictions for patients likely affect patient's willingness to travel and to seek or use medical care. For instance, although our institution clinics remained fully staffed during the study period in the pandemic to accommodate a regular influx of patients and in-person visits, the number of patient referrals declined between March and May 2020. Pandemic-related factors might have resulted in referrals for patients with more advanced disease, greater symptoms, or other morbidities requiring urgent medical follow-up.

Other limitations of this study include a small sample size from a single institution in a large urban setting and its retrospective nature. Thus, it is unclear whether our results are generalizable to all practice environments and patient populations. In addition, further research is needed to investigate other metrics of care and patient-oriented end points beyond our 3-month follow-up period. A majority of patients in our virtual cohort also had their initial visit conducted virtually (87%), and further research is needed to evaluate whether outcomes may differ when initial visits are conducted virtually or in-person. Similarly, it remains to be investigated whether the proportion of virtual care used may be associated with outcomes as this could not be distinguished in our study with a limited sample of patients who received virtual care exclusively. Our analysis of potential miles of travel avoided and time saved assumes that patients do not receive treatment in the same visit, which does not apply to all patients. Nonetheless, our findings provide new insight as previous research has largely examined the use of telehealth as a complement rather than a replacement of in-person care.13 In a recent survey, 62% of patients with cancer reported a delay in cancer-related care attributed to COVID-19, suggesting that telehealth efforts should be intensified as a safe remedy to address patient care needs.14 These findings also have implications for the use of telehealth in oncology beyond the pandemic as a convenient and reliable resource for patients and providers.

Adam Yopp

Research Funding: Merck

Muhammad S. Beg

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ipsen, Array BioPharma, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Cancer Commons, Legend Biotech

Research Funding: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck Serono, Agios, Five Prime Therapeutics, MedImmune, ArQule, Genentech, Sillajen, CASI Pharmaceuticals, ImmuneSensor Therapeutics, Tolero Pharmaceuticals

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

D.H. was supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: David Hsiehchen, Magdalena Espinoza

Financial support: David Hsiehchen

Administrative support: David Hsiehchen

Provision of study materials or patients: David Hsiehchen

Collection and assembly of data: David Hsiehchen, Magdalena Espinoza

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Clinical Efficiency and Safety Outcomes of Virtual Care for Oncology Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Adam Yopp

Research Funding: Merck

Muhammad S. Beg

Consulting or Advisory Role: Ipsen, Array BioPharma, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Cancer Commons, Legend Biotech

Research Funding: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Merck Serono, Agios, Five Prime Therapeutics, MedImmune, ArQule, Genentech, Sillajen, CASI Pharmaceuticals, ImmuneSensor Therapeutics, Tolero Pharmaceuticals

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koonin LM, Hoots B, Tsang CA, et al. : Trends in the use of telehealth during the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January-March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:1595-1599, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jeffery MM, D'Onofrio G, Paek H, et al. : Trends in emergency department visits and hospital admissions in health care systems in 5 states in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med 180:1328-1333, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, et al. : Variation in telemedicine use and outpatient care during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood) 40:349-358, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elkaddoum R, Haddad FG, Eid R, et al. : Telemedicine for cancer patients during COVID-19 pandemic: Between threats and opportunities. Future Oncol 16:1225-1227, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flodgren G, Rachas A, Farmer AJ, et al. : Interactive telemedicine: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD002098, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hersh WR, Helfand M, Wallace J, et al. : Clinical outcomes resulting from telemedicine interventions: A systematic review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 1:5, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean S, Sheikh A, Cresswell K, et al. : The impact of telehealthcare on the quality and safety of care: A systematic overview. PLoS One 8:e71238, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruse CS, Krowski N, Rodriguez B, et al. : Telehealth and patient satisfaction: A systematic review and narrative analysis. BMJ Open 7:e016242, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz HP, Kaltsounis D, Halloran L, et al. : Patient safety and telephone medicine: Some lessons from closed claim case review. J Gen Intern Med 23:517-522, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitsiou S, Pare G, Jaana M: Effects of home telemonitoring interventions on patients with chronic heart failure: An overview of systematic reviews. J Med Internet Res 17:e63, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agboola S, Jethwani K, Khateeb K, et al. : Heart failure remote monitoring: Evidence from the retrospective evaluation of a real-world remote monitoring program. J Med Internet Res 17:e101, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall JL, McGraw D: For telehealth to succeed, privacy and security risks must be identified and addressed. Health Aff (Millwood) 33:216-221, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noah B, Keller MS, Mosadeghi S, et al. : Impact of remote patient monitoring on clinical outcomes: An updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. NPJ Digit Med 1:20172, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Cancer Society : COVID-19 Pandemic Ongoing Impact on the Cancer Community: May 2020. Washington, DC, American Cancer Society, 2020 [Google Scholar]