Abstract

Slum settlements have received significant attention for their vulnerabilities to the spread of Covid-19. To mitigate risks of transmission, and alleviate economic distress associated with containment measures, public health experts and international agencies are calling for community-driven solutions that harness local participation. In slum settlements, such approaches will encounter the informal slum leaders present across cities of the Global South. How are slum leaders positioned to address the health and livelihood threats of the pandemic within their neighborhoods? What problem-solving activities, if any, have they performed for residents during the pandemic? What factors shape success in those efforts? To answer these questions, we conducted a phone survey of 321 slum leaders across 79 slum settlements in two north Indian cities. The survey was conducted in April and May 2020, at the height of India’s stringent national lockdown in response to the virus. Our survey reveals striking continuities with pre-pandemic politics. First, slum leaders persist in their problem-solving roles, even as they shift their efforts towards requesting urgently needed government relief (particularly food rations). Second, slum leaders vary in their reported ability to gather information about relief schemes, make claims, and command government responsiveness. The factors that inform the effectiveness of slum leaders during ‘normal times’, notably their education and degree of embeddedness in party networks, continue to do so during the lockdown. Slum leader reliance on partisan networks raises concerns regarding the inclusiveness of their efforts. Finally, slums are not uniformly challenged in maintaining social distancing. Pre-pandemic disparities in infrastructural development fragment the degree to which residents must depart from social distancing guidelines to secure essential services.

Keywords: Urban Informality, Slums, Covid-19, Distributive Politics, Asia, India

1. Introduction

In a phone conversation on April 29, 2020—at the height of India’s coronavirus-induced lockdown—Aakash Chouhan described the precarious state of things in Ganpati Nagar. Ganpati Nagar is a sprawling kachi basti (slum settlement) in Jaipur, the capital city of Rajasthan state. Aakash, an informal leader in the settlement, explained that the dense mass of jhuggies (shanties) in Ganpati Nagar was making social distancing all but impossible. Compounding this issue of overcrowding, many residents do not have water taps within their homes, forcing them to gather at public posts. And because city sweepers mostly limit their cleaning to the main road outside the slum, residents must leave their homes to clear alleyways of mounting trash.1 Staying away from other people in Ganpati Nagar, within or outside one’s home, is not feasible.

Slum settlements like Ganpati Nagar have received significant attention for their vulnerabilities to the spread of Covid-19 (Biswas, 2020, Lee et al., 2020, Parth., 2020). UN-Habitat puts the dangers of the pandemic to this population in blunt terms: “The impact of Covid-19 will be most devastating in poor and densely populated urban areas, especially for the one billion people living in informal settlements and slums worldwide” (UN-Habitat, 2020).

Catching the virus is not the only threat facing slum residents in India. Many face land tenure insecurity because they lack formal property rights.2 Most residents also work in the informal sector and depend on tenuous, day-to-day earnings.3 For several weeks, India’s nationwide lockdown put a hard stop to those earnings, pushing many residents into an even deeper state of precarity. To help residents in Ganpati Nagar, Aakash has contacted public officials to request food. He has also assisted residents in obtaining documents that are required to access government relief.

There are growing calls from public health experts (Corburn et al., 2020) and international agencies to include figures like Aakash within “community-driven solutions” in the fight against Covid-19 (UN-Habitat, 2020).4 A Social Science in Humanitarian Action (2020) report, for example, argues: “It is crucial that responses to Covid-19 are organized through…groups and leaders [in informal urban settlements] who know their settings best and have existing links to residents.” Epidemiologists have written that mitigation policies “need to be carried out in partnership with community organizations…even local gangs could be partners” (Lee et al., 2020).

Yet, despite such growing calls for inclusive policy responses, there is little systematic information coming from slum communities themselves. Efforts to survey slum residents are hampered by the inability of researchers to conduct face-to-face surveys during the pandemic. Most information on the pandemic-time experiences of slum residents comes from journalistic interviews of residents in a small handful of famous ‘mega-slums,’ such as Dharavi in Mumbai or Kibera in Nairobi (Chebet, 2020, Gettleman, 2020).

The information in such reports is necessarily limited. First, these city-sized mega-slums are hardly representative of most slums within their respective countries, let alone elsewhere. Second, these accounts do not sufficiently address how challenges during the pandemic relate to, and are informed by those many vulnerabilities in slums that predate its onset. Third, slum populations are too often described in undifferentiated and apolitical terms. Such language neglects the possible role played by informal hierarchies of leadership that emerge to deal with everyday problems within settlements.

Consequently, crucial questions about the experiences of slum residents during the pandemic remain unanswered. Do residents perceive similar challenges in facing the crisis than those ascribed by external observers? Are the local leadership structures slum residents use to address everyday governance problems able to help secure needed assistance during the pandemic? To what degree are these local leaders informed about government relief schemes initiated during the lockdown that slum residents might benefit from?

To investigate these questions, we conducted a telephone survey in April and May 2020 of 321 slum leaders across 79 squatter settlements—a pervasive type of slum settlement in India and cities of the Global South more broadly—in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh and Jaipur, Rajasthan.5 Importantly, our design and implementation of this phone survey drew on a decade of prior qualitative and survey research in these same settlements and with the same informal leaders. Our repeated interactions with these slum leaders allowed us not only to contact them by phone, but ensured a robust response rate, and underpinned their willingness to talk at length about the complexities of the crisis.

India is an important setting in which to study how the pandemic is unfolding within slums. First, an estimated 65 million people live across India’s slums (Government of India, 2015). Second, India’s central government imposed some of the world’s most stringent mitigation strategies in its immediate response to the pandemic.6 On March 24, India announced a nationwide lockdown for three weeks. During this initial phase, nearly all services, travel, and economic activities were suspended or prohibited, and people were banned from leaving their homes. The lockdown was extended several times, and remained in place until May 31, with some varying relaxations, after which the central government announced a phased lifting of restrictions. For slum populations marked by poverty and informality, the lockdown made the ‘lives versus livelihoods’ tradeoff especially acute.

We present two key sets of findings. Our first set of findings pertains to how sampled slum leaders articulate the challenges produced by the pandemic and lockdown. First, they note that while they continued with their problem-solving activities, the focus of those activities pivoted sharply to demanding urgently needed government relief—specifically, food rations. Second, their protracted efforts to secure public infrastructure like roads and streetlights have slowed during the crisis, not only because of more pressing subsistence issues but also because of the heightened costs to collective action under lockdown orders. Third, pre-pandemic disparities across settlements in levels of infrastructural development inform the types of local challenges to social distancing noted by surveyed slum leaders.

Our second set of findings concern variation in the degree to which slum leaders are able to mitigate the adverse effects of the pandemic and lockdown. First, we document considerable variation in the effectiveness of slum leaders during the pandemic, including in the information they possess about pandemic-time government relief programs, their ability to contact politicians and bureaucrats, and their ability to get requests for assistance fulfilled. Second, variations in slum leader effectiveness correspond to differences in their level of education, degree of rootedness in partisan networks, and affiliation to the incumbent party in their province. The importance of slum leader education and partisan embeddedness suggests considerable continuity with the determinants of slum leader efficacy during ‘normal’ times. Overall our findings show the continued importance of leaders as problem-solvers during the pandemic, but also document the notable limits to their efforts imposed by a reliance on partisan networks.

2. Informal community governance in India’s slums

An examination of how India’s slums are positioned to confront the coronavirus crisis must grow out of an understanding of the ways in which these communities are organized during ‘normal times.’ Such knowledge is crucial for designing and implementing local resilience strategies that are “co-produced” between the state and communities (Ostrom, 1996, Gupte and Mitlin, 2020). In this section, we sketch the contours of informal governance in India’s slums, drawing on our fieldwork and survey research in Bhopal and Jaipur.

At the center of political life in India’s slums is the basti neta, or slum leader. The economic deprivation and state repression that slum residents face compels them to select leaders who spearhead efforts to demand development and resist eviction. These are non-state actors who live within settlements and experience the same risks of eviction and underdevelopment as their neighbors.7 Alongside residents, slum leaders also experience state violence, manifest as evictions and aggressive policing (Bhan, 2016, Ghertner, 2015). What separates netas from other residents is an ability to get things done in the city.

Several attributes underpin leaders’ problem-solving abilities, including literacy and some formal education, which facilitate petition writing and navigating government institutions (Auerbach and Thachil, 2018).8 Slum leaders often rely on writing petitions as an important strategy for making claims on local politicians and bureaucrats (Auerbach, 2017; Auerbach, 2020). Slum leaders are also more likely than average residents to hold modest public sector jobs—for example, municipal sweepers, clerks, and guards—granting them a small but useful degree of connectivity to local government.9

Three features of slum leadership buttress their significance during the pandemic: their widespread prevalence; the broad array of activities they perform; and their embeddedness within partisan networks. First, slum leaders are nearly omnipresent across settlements. In our 2015 survey of 2199 residents across 110 slum settlements in Bhopal and Jaipur, 69% of respondents acknowledged slum leaders in their settlement. All but three settlements had resident-acknowledged slum leaders. Moreover, almost all (103 of 110 settlements) had multiple slum leaders. Researchers have documented these same figures in other Indian cities (Das & Walton, 2015, de Wit, 1997, Jha et al., 2007).

Slum leaders perform an array of activities for residents. Drawing on our 2015 resident survey, the most commonly reported activities are helping residents secure ration cards and petitioning officials for public services like paved roads, piped water, drains, and streetlights.10 Slum leaders also engage in dispute resolution, organize residents to fight eviction, and spread information about public programs for the poor.

The targets of these claims are situated across India’s three tiers of elected government as well as a constellation of bureaucrats and government departments in charge of specific public services. Since decentralization reforms in the early 1990s, municipal governments have emerged as increasingly important institutions in India’s cities. Elected municipal councilors are often a first port of call for slum leaders seeking to make demands on behalf of their settlement,11 in part because of their small constituency sizes.12 Yet slum leaders can and do also directly contact higher-level politicians, such as state-level Members of Legislative Assembly (MLA).13

Finally, slum leaders are predominantly embedded within partisan political networks. In 2016, we surveyed 629 slum leaders across the same 110 settlements sampled in our 2015 resident survey. The vast majority (544) was affiliated with either the Indian National Congress (INC) or Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the two political parties in competition in Bhopal and Jaipur. In this role, they organize rallies, distribute patronage goods, and encourage election-time turnout—the trappings of urban popular politics (Chatterjee, 2004). Affiliation with party networks also confers access to influential elites, which helps slum leaders fulfill the requests of residents from a dismissive and discretionary state.14

The importance of these figures is plausibly heightened during the Covid-19 pandemic. The state’s imperviousness to slum residents is likely all the more acute, when already brittle state capacity is being stretched thinner and citizens are less able to politically mobilize to strengthen their claims. Such conditions may well amplify the importance of slum leaders as mouthpieces transmitting their community’s problems.

3. A phone survey of slum leaders

Below, we draw on a phone survey of 321 slum leaders across 79 slums in Bhopal and Jaipur, conducted during India’s coronavirus lockdown. We focus on a pervasive type of slum in India and cities of the Global South more broadly: squatter settlements. Squatter settlements are crowded, low-income neighborhoods constructed by residents in an unsanctioned, haphazard manner. Residents of squatter settlements face land tenure insecurity due to weak or absent formal property rights and are marginalized in the distribution of basic public services (UN-Habitat, 1982). Squatter settlements are often located on environmentally sensitive lands like riverbeds, mountainsides, and along railroad tracks.

Below, we use the terms “squatter settlement” and “slum” interchangeably to refer to the neighborhoods under study. We do so for ease of exposition and to resonate with the colloquial and official use of the term “slum” in India, which encompasses squatter settlements. Readers, though, should note that squatter settlements are the specific empirical focus of this study and represent just one type of settlement that falls within the larger category of “slums.”15 Their widespread presence and intensive vulnerabilities make them substantively important spaces to study in the context of the pandemic.16

Ordinarily, any systematic survey of slum leaders faces considerable challenges given the informal nature of these positions. Doing so during a pandemic is even more challenging and required building on a multi-staged survey design. In the summer of 2015, we surveyed 2199 residents across 110 squatter settlements in Bhopal and Jaipur. Settlements were selected through a stratified random sampling procedure. First, we gathered lists of slums in the two cities and mapped them in Google Earth.17 These lists in Bhopal and Jaipur included 375 slums and 273 slums, respectively.

The official lists of “slums” included a variety of low-income neighborhoods—squatter settlements, dilapidated old city neighborhoods, post-eviction resettlement colonies, and erstwhile villages swallowed by urban sprawl. As such, we had to truncate the lists to squatter settlements. Delineating types of settlements in this way is important, as they differ in their legality, historical origins, and social integration in the city.18 Indeed, as Krishna and his coauthors (2014, p. 2) argue, “Little is gained (and much is lost) by considering slums as a homogenous category of settlements.” Sampling from within the category of squatter settlements also ensures a higher degree of comparability across units, given the common origins and features of these neighborhoods in India’s cities.

We identified squatter settlements by their distinctive physical features—unplanned, densely populated, and amorphously shaped neighborhoods with tangled and narrow networks of alleyways—using satellite imagery and extensive field visits (see Fig. 1 for an example squatter settlement).19 The final sample frame of squatter settlements totaled 115 in Jaipur and 192 in Bhopal. We then selected 110 settlements (50 in Jaipur and 60 in Bhopal) through random sampling stratified on population and geographic area.20

Fig. 1.

A Squatter Settlement in Central Bhopal.

Households within our 110 sampled settlements were selected through a spatial sampling technique. We downloaded satellite images of each settlement from Google Earth and then randomly selected width and length pixels on each image. Pixels that landed on rooftops were marked and assigned to an enumerator. Those that fell on open spaces or outside the settlement were discarded and resampled. This process yielded 20 randomly selected households per settlement. The authors accompanied the survey teams to ensure the integrity of the sampling procedure.

We asked residents to provide names of the informal leaders in their settlement. Drawing on these responses, and a census of party workers across the 110 settlements, we created a sample frame of 914 slum leaders. In the summer of 2016, we conducted a face-to-face survey of 629 slum leaders, yielding a response rate of 68.18%. Most non-responses were due to slum leaders leaving the settlement, being sick, or having passed away. Only 24 slum leaders declined to participate. To our knowledge, this is the first large and representative survey of slum leaders ever conducted, in India or elsewhere.

We returned to our 629 surveyed slum leaders in April and May 2020 to investigate their activities and opinions during the lockdown. Between 2016 and 2020, 13 of our 110 sampled settlements had been evicted. As a consequence, our sample frame for the phone survey was reduced to 590 slum leaders across 97 settlements.

We were able to contact and survey 321 slum leaders across 79 of the settlements over the phone, for a response rate of 54%.21 Given how frequently people change their phone numbers in our study setting, coupled with the difficult times in which we sought to talk, this response rate is impressive. In fact, nearly every non-response was due to the respondent’s number being switched off (with a minimum of five different attempts, with only one refusal). We view this high response rate as a product of our sustained engagement with these communities.

3.1. The sampled slum leaders

Table 1 describes our phone survey sample of 321 slum leaders, and compares them to the 308 leaders we could not contact who were in our original sample. The table shows the sample we could interview was broadly comparable to those whom we could not reach across a range of attributes measured in 2016, including gender, age, religion, party affiliation, and political experience. This comparability helps assuage concerns that our phone survey sample is not representative of our original sample of slum leaders.22

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Surveyed Slum Leaders.

| Respondent Attribute | Included in Phone Sample (N = 321) | Excluded from Phone Sample (N = 308) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years in 2016) | 47.738 | 47.766 | 0.028 |

| Education (in years) | 8.595 | 8.143 | −0.452 |

| Female | 0.103 | 0.143 | 0.040 |

| Born in settlement | 0.231 | 0.299 | 0.068* |

| Experience (in years in 2016) | 20.595 | 20.256 | −0.339 |

| BJP Leader (in 2016) | 0.533 | 0.487 | −0.046 |

| Congress Leader (in 2016) | 0.327 | 0.357 | 0.030 |

| Party position-holder (in 2016) | 0.682 | 0.636 | −0.046 |

| Religious Minority | 0.271 | 0.315 | 0.044 |

Note: All tests are two-tailed. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Table 1 shows slum leaders are overwhelmingly male, and predominantly born outside of their settlement. On average, they have considerable experience in informal leadership positions. As with our original survey, the vast majority of leaders in our phone sample (86%) are affiliated with one of the two major political parties, the BJP and Congress. Finally, we find considerable social diversity, in line with our 2016 sample. Leaders come from just over 100 different Hindu jati (subcastes) or Muslim zat. Over one in four leaders on our phone survey came from non-Hindu religious minorities (89% of these religious minority leaders are Muslim).

How do surveyed slum leaders compare to ordinary residents in their settlements? We compare the 321 leaders with ordinary residents we surveyed across the same 79 settlements in 2015 (N = 1574). Not surprisingly, leaders are far less likely to be female (10.3%), compared to residents (45.7%). Leaders are also older than average residents (48 years to 36) and more educated (8.6 years to 5.5 years). While far from wealthy, leaders do have higher household monthly incomes than average residents (Rs. 22,665/USD 307 to Rs. 12,520/USD 170).23 However, leaders in our phone sample are not less likely than residents to come from minority faiths (27% to 26%). These comparisons are especially important in revealing the position of slum leaders within settlements, and the degree to which they represent certain kinds of residents. It is worth keeping in mind how the characteristics of slum leaders might shape their assessments of the pandemic and mitigation strategies.

4. Challenges of the crisis and slum leader responses

Accounts of India’s slums as sitting-duck coronavirus hotspots have been largely absent of community-level voices. How do slum leaders, who are deeply embedded in the social and political networks of their neighborhoods, assess the multi-faceted problems of the pandemic and lockdown? What do they see as barriers to social distancing and the challenges of slowed economic activity? How have these challenges affected the activities they undertake on behalf of residents?

4.1. Challenges for social distancing

We asked our 321 respondents a series of questions about potential obstacles for social distancing. The first question probed the extent to which residents know the importance of keeping away from one another to prevent virus transmission. 43% of surveyed slum leaders noted that knowledge about social distancing is uneven within their settlement—that, “some residents know” while others do not. Few (5%) slum leaders described a total lack of awareness among residents, while the majority (52%) expressed that “everyone” in their settlement knows the importance of social distancing. According to leaders, low levels of formal education among residents have not prevented public awareness from growing about social distancing.

Other questions explored challenges stemming from the built space, and the marginalized status of residents in the provision of public services. A significant percentage of the residents we surveyed in 2015 across the 79 represented slums do not have water taps within their homes (39%). To collect water for drinking and cleaning, they use communal sources like public taps, borewells, and truck-fed tanks, which force them to move about in public spaces. Moreover, intermittency in water supply narrows the bands of time when water can be collected, and creates uncertainty over the timing of that supply. Failing to wait can mean losing out on water for the day, so people tend to congregate in groups, often for lengthy periods, to fill their buckets.24

One-fifth of respondents reported that crowding around shared water sources is either a major problem (12%) or moderate problem (8%) for social distancing. The remaining respondents did not see this as a problem within their settlement. When we investigate these responses further, we find that slum leaders living in settlements with sparser household water connections are nearly twice more likely to report public water sources as a problem for social distancing than those slum leaders in settlements with more widespread household water connections.25 As one such leader told us:

In my settlement, many people don’t have taps in their home. So people…are forced to come outside. Many people understand it is dangerous to come to a crowded place for water, but they have to. This is a big problem.26

In response, several slum leaders we spoke to described efforts to ensure a regular water supply reaches their settlement during the pandemic:

Sometimes the water is late. Usually, it comes at 5:30 pm, but it has been coming at 7 pm…I called the councilor and my party president, and they called the water people. The water is still sometimes late, but I’ve made sure it comes every day.27

The biggest problem has been water. We had to call tankers privately to get water, and leaders like me have to make those calls.28

These findings suggest that, in the short-term, state governments should provide a more regular and robust supply of water in those slums lacking household water connections. Sending water tankers to meet supply gaps can be important, but might lead to problems of overcrowding at the tanker itself. Such deliveries should be combined with efforts to reduce crowding. In the longer term, investments in piped water should not only be seen as extending a crucial public service, but also as a means of facilitating social distancing during public health crises concerning infectious diseases.

The overcrowded nature of slum settlements has often been cited as a problem for social distancing (Sur & Mitra, 2020). Within squatter settlements, jhuggies are packed together without any semblance of planning, creating amorphously shaped neighborhoods strung together with narrow alleyways (see Fig. 1). The problem of overcrowding extends to domestic life as well. The average household across the 79 settlements has 6 people living in it, often within one or two small rooms with little ventilation. In such environments, it is not surprising that more than half of our slum leader respondents reported dense living conditions to be at least somewhat of a problem (21%) if not a big problem (32%) for social distancing in their settlement.

As our opening vignette suggests, slum residents are often left to clean public drains and gutters themselves, as municipal sweepers infrequently or never come to remove solid waste. In the average of the 79 settlements, only 47% of surveyed residents in 2015 reported that municipal sweepers come to their settlement to clean, with a one standard deviation of 24%. Most slum leaders (86%), however, did not believe the need to gather to clean public spaces was a problem with respect to social distancing.

This lack of concern possibly stems from the fact that the lockdown unfolded before the start of monsoon season, when problems around drainage are most acute and require more routine cleaning. It could also reflect the active efforts of slum leaders and residents to take actions to preempt this problem from growing. Leaders we spoke to described settlement-wide cleaning efforts they had organized:

The first thing I did was pay attention to cleaning. I organized a cleaning drive in the basti, where I asked everyone to clean their areas. The councilor provided us a tanker with a sanitizer spray that we used on the houses of the slum.29

4.2. Disruptions of the lockdown

A second series of questions sought to understand the depth of problems associated with suspended movement and slowed economic activity due to the lockdown. Food shortages emerged quite clearly as the most pressing concern facing residents, according to surveyed slum leaders. More than three-quarters of respondents stated that food shortages had become either a much deeper problem (44%) or moderately deeper problem (34%) for residents since the start of the lockdown. One third of respondents went on to note that difficulties in accessing medicine had also become a much deeper problem (12%) or moderately deeper problem (20%) for residents since the start of the lockdown.

Pre-lockdown levels of water supply and sanitation do not appear to have changed in most settlements: 79% of surveyed slum leaders reported that the supply of these two services has gone unchanged. The remaining one-fifth noted that these two services are either much worse (4%) or worse (17%) compared to pre-lockdown levels. In interpreting these findings, it is important to note that in many settlements, water and sanitation services were insufficient before the lockdown. That inadequacy has persisted for many residents during the lockdown.30

The vast majority of respondents (93%) reported that unemployment is “much worse” during the lockdown. Most residents work in the informal economy, doing jobs that require leaving the settlement and moving about in the city. Drawing on our resident survey, these jobs most commonly include unskilled laborers, domestic workers, autorickshaw drivers, street vendors, and small shop owners.

We asked our sampled slum leaders how many days the average household in their settlement could go on in the context of the lockdown with their current food and money supply. The average response was just over three weeks, at 24 days. Note that the lockdown had been going on for a month at the start of our survey.

Almost all of the 321 surveyed slum leaders (95%) reported that the police patrolled within their settlement during the lockdown. A non-trivial 29% went on to note that there have been instances of police violence toward residents. Their responses align with news reports of police repression during the lockdown, many of which note violent actions often disproportionately target slum residents and poor urban migrants (see Thachil, 2020).

These myriad threats have compelled slum leaders to reorient their efforts from their typical activities toward providing residents with immediate relief. 58% of the leaders we surveyed had contacted a politician—broadly conveyed to include ward councilors, MLAs, and MPs—in the city to request assistance on behalf of residents since the lockdown began. Yet none of these requests were for the everyday repairs for the settlement that slum leaders so often focus on. Instead, these efforts have been overwhelmingly to request food rations for residents of their settlement: 91% of the 185 slum leaders who contacted a government official or politician during the lockdown have done so to request food.

Many leaders also highlighted their efforts to ensure residents had the required documents to avail government relief programs, particularly food assistance, launched in the wake of the lockdown.

I called our ward councilor…I told him there are people in my settlement without ration cards. If they don’t have this card they cannot get the free grains the government is giving to people during the lockdown. He talked to the people at the ration shop and they told him to give a list of the people who need supplies. He gave them the list of 25 people that I gave him, and in two days time these 25 people got 10 kg of wheat, 2 kg rice, and one packet of salt.31

Other leaders spoke of their role in ensuring food packets delivered by politicians and private NGOs reached the most deserving beneficiaries:

I have tried to make a list of households who must work each day in order to eat (roz kamane vale, roz khane vale). I made sure they were the ones who got the supplies. See, if I knew a household was better off then we would not give the supplies to them. Now, how long can even those families last? No one here is a crorepati (multi-millionaire). In the days to come, they will need help as well.32

Such responses are framed in terms of deservingness, but raise questions of how slum leaders might work to ensure resources are channeled toward particular residents, especially their own political supporters. As we document in the next section, partisan networks do appear to structure the political responsiveness that slum leaders receive from higher-level officials during the pandemic, much as in everyday politics. Such partisan biases point to limitations of community-driven efforts relying on actors embedded within politicized networks.

Given the challenges induced by the stringent lockdown, readers might assume that slum leaders will favor suspending the lockdown as soon as possible. Yet leaders articulated a far more nuanced and heterogeneous set of views. We asked respondents whether, in their view, residents in their settlement were more worried about health concerns from the virus, or the threat to livelihoods posed by the lockdown. A majority (54%) said they believed residents were more concerned by the threat the pandemic posed to their health. As one leader told us, “what’s the point of jobs without health? If we are sick, we will not be able to work.”33 A smaller, but non-trivial proportion (36%) of respondents viewed economic concerns as trumping health, as another leader articulated:

Earning our daily bread is a far bigger problem than health. Look, people can still get better from an illness. But no one can live without bread…and people need to be able to earn in order to eat. 34

In other discussions, leaders noted that slum residents must often engage in work that is especially high risk, from delivery and cleaning services, to work in crowded markets and factories. Such varying responses are reminders not to assume or simplify responses from residents on their views of the relative costs of the pandemic and the lockdown.

5. How effective are slum leaders in responding to the crisis?

We shift now from describing how slum leaders assess the pandemic and lockdown, to evaluating how effectively they perform their duties during this challenging period. Slum leaders are regarded as key sources of information within their communities. Where do these leaders get their pandemic-related information? We find that they rely on a diversity of sources. The most common are news channels on television (86%), followed by newspapers (62%). Social media (Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter) and personal conversations with people in their social and political networks also make up a nontrivial portion of information sources (40% and 36%, respectively).35 However, these patterns suggest caution in rushing to proclaim social media platforms, particularly WhatsApp, as the dominant source of information among local political operatives in urban India.

In these latter two categories, we probed further the specific sources of information. These answers revealed the preeminence of the political networks in which leaders are embedded. Of those who cited social media as a source of information, 57% noted other party workers as the people sharing that news, and 45% cited more senior politicians in the city. By comparison, only 27% cited religious leaders, and 30% cited doctors, medical professionals, or healthcare workers.

Perhaps more important is examining how effective slum leaders are in accessing information that is valuable to residents. Following the abrupt lockdown order, India’s central government announced a number of schemes designed to help economically disadvantaged citizens. While some of these benefits focused on the countryside, at least five highly publicized schemes were important for slum residents, including 5 kg of free rice or wheat and 1 kg of lentils distributed through the Public Distribution System36 , monthly cash transfers of Rs. 500 for three months to women holding bank accounts opened under the Jan Dhan financial inclusion scheme,37 three free cooking gas cylinders to poor women registered with the Ujjwala Yojana scheme38 , Rs. 1000 additional monthly pension for three months for those receiving old age, widow, or disability pensions39 , and instructions to state governments to pay construction workers out of pre-existing welfare board funds.40

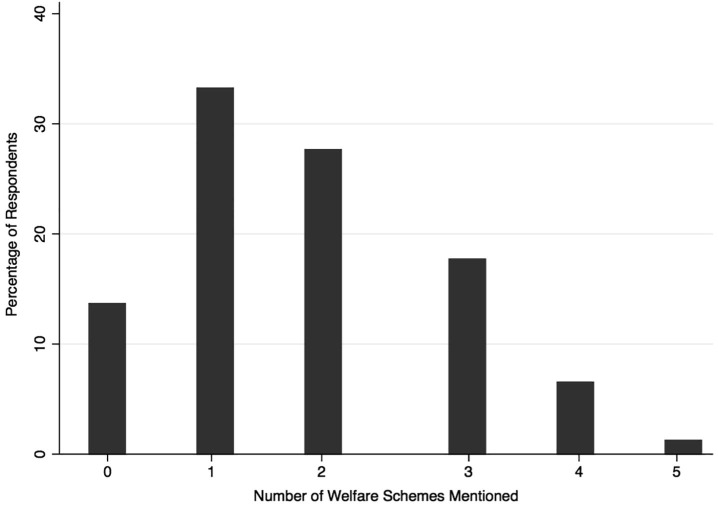

The success of such schemes depends at least in part on citizens being aware of their existence, in order to avail of these benefits. We therefore asked slum leaders to enumerate any schemes they were aware of being launched following the lockdown order that slum residents might benefit from. We coded how many of these five key schemes the respondent listed without any prompting. This measure is a helpful indicator of slum leader capabilities given that these schemes were applicable across our study cities, and were widely and simultaneously reported across the country. Yet Fig. 2 shows significant variation in leader awareness of these schemes. 47% of our sample named zero or one scheme, while the remaining 53% identified two or more schemes.

Fig. 2.

Slum Leader Awareness of Relief Schemes. Note: The figure shows the distribution of responses regarding how many out of five key welfare schemes affecting slum residents announced in the wake of India’s lockdown slum leaders were able to identify without prompting (N = 321).

Another key role of slum leaders is in lobbying political elites to fulfill the requests of people in their settlements. These efforts are central to generating the popular support upon which their informal authority rests. The leaders we surveyed were all from the settlements in which they worked, did not have family connections in politics (81%), and were migrants to the cities in which they lived (74%). Their authority did not come from caste hierarchies, dynastic power, or economic clout. It was earned through entrepreneurial sweat.

Yet our survey revealed unevenness in the degree to which slum leaders had contacted or been contacted by politicians.41 30% of respondents said a politician had reached out to them since the lockdown’s onset. The vast majority (90%) of such calls involved the politician asking the slum leader how they might help the settlement. 58% of leaders reported taking the initiative and calling a local political leader themselves. Further, responsiveness to those requests has been uneven. 63 of the 185 slum leaders (34%) who asked for help reported that they have received “no assistance,” and another 29% report receiving “full assistance.” The rest lie in between (37%), stating they have received “some assistance.”

In short, our survey uncovers considerable variation in the extent to which slum leaders know about pandemic-related government programs, in the degree to which slum leaders have contacted or been contacted by politicians, and the degree to which their calls for help produce a response.

What factors shape such variation? Column 1 of Table 2 reports the results of an OLS regression model in which the dependent variable measures how many of the five major relief schemes the slum leader correctly identified in an unprompted and open-ended answer. The dependent variable for the model reported in Column 2 is whether the slum leader was called by a politician, and in Column 3 is whether they themselves contacted a politician for assistance. The model in Column 4 truncates the sample to slum leaders who report requesting help (185 of the 321 slum leaders surveyed). The outcome here identifies whether they received no (0), some (1), or full (2) assistance.42

Table 2.

Correlates of Slum Leader Efficacy During the Lockdown.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Awareness of Schemes (0–5) | Politician Called Slum Leader (0–1) | Slum Leader Called Politician (0–1) | Slum Leader Got Help (0–2) |

| Experience (years) | 0.007 | 0.006* | 0.005 | −0.009 |

| (0.011) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.008) | |

| Meeting Attendance a (0–4) | 0.005 | 0.048*** | 0.038* | 0.134*** |

| (0.045) | (0.016) | (0.022) | (0.042) | |

| Position-Holder | 0.291* | 0.147** | 0.110 | 0.008 |

| (0.157) | (0.068) | (0.090) | (0.134) | |

| Education a (years) | 0.033** | 0.016** | 0.001 | 0.015 |

| (0.014) | (0.006) | (0.007) | (0.021) | |

| Aligned w/ Center + Local | −0.124 | −0.045 | −0.012 | −0.177 |

| (0.166) | (0.045) | (0.057) | (0.111) | |

| Aligned with State | 0.117 | 0.199*** | 0.054 | 0.389*** |

| (0.143) | (0.059) | (0.055) | (0.132) | |

| Female a | −0.044 | 0.085 | −0.049 | 0.065 |

| (0.261) | (0.076) | (0.095) | (0.209) | |

| Religious Minority a | −0.168 | 0.062 | −0.043 | −0.149 |

| (0.129) | (0.065) | (0.064) | (0.130) | |

| Household Income a (logged) | −0.169* | 0.017 | 0.025 | 0.054 |

| (0.095) | (0.038) | (0.039) | (0.065) | |

| Age | −0.009 | −0.005* | −0.005* | −0.004 |

| (0.010) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.009) | |

| Bhopal Leader | 0.090 | −0.017 | −0.150*** | −0.066 |

| (0.171) | (0.050) | (0.055) | (0.143) | |

| Observations | 311 | 311 | 311 | 179 |

Notes: *p < 0.10 **p < 0 .05 ***p < 0.01 The table reports results from OLS regressions with robust standard errors clustered by settlement. Dependent variables in these specifications indicate the number (out of five) of post-lockdown welfare schemes identified by respondents (Column 1), a binary indicator of whether a politician contacted a slum leader since the onset of the lockdown (Column 2), a binary indicator of whether a slum leader called a politician for assistance since the lockdown onset (Column 3), and a three-point indicator of whether slum leaders requesting help received no, some, or full assistance (Column 4). a refers to variables measured on the 2016 face-to-face survey, all others are measures from the 2020 phone survey.

The results expose a few patterns. First, our outcomes of interest do not correlate with gender. Female slum leaders are in a minority, comprising just over 10% of our phone sample, and 12% of our original sample. Yet, our fieldwork demonstrated that women who do become slums leaders are influential within their settlements. Indeed, we do not find that female leaders are systematically less knowledgeable about public schemes, less likely to be contacted by politicians, or less likely to receive requested assistance. Comparing Hindu and (predominantly Muslim) minority leaders, while the latter report lower levels of knowledge of schemes, and lower rates of receiving requested help, these differences are not statistically significant.

By contrast, we find considerable evidence of the importance of education and a slum leader’s embeddedness in partisan networks. First, a slum leader’s education positively correlates with their knowledge of schemes during the lockdown. This result is important given that since many slum residents are formally eligible for benefits under these five schemes, a leader’s knowledge of these benefits can potentially enable residents to access such welfare without additional politician mediation. As we mention above, many residents report that enabling such direct access is a key feature of the everyday activities of slum leaders in normal times. A slum leader’s efficacy cannot thus be reduced to their ability to connect with politicians, as measured by outcomes in Columns 2–4, but also encompasses their ability to disseminate information enabling residents to seek benefits directly.

Beyond this informational channel, Table 2 also suggests educated slum leaders can induce greater political responsiveness from elites. Column 2 shows education positively correlates with a leader reporting being contacted by politicians during the lockdown. This outcome is an important, given that the purpose for the vast majority of such calls (86 out of 96) was to ask the slum leader what kind of assistance the politician could provide to the settlement.43 Substantively, a one standard deviation increase in slum leader education (4.5 years) corresponds to a 7.2 percentage point increase in their likelihood of being contacted. This is substantial, given only 30% of leaders report such contact from politicians.

Importantly, we do not find evidence that education’s impact is due to its correlation with economic status. Education’s impact remains significant even when controlling for monthly household income. Income is in fact weakly correlated with education within our sample, negatively correlates with scheme awareness, and does not significantly correlate with any of our measures of political responsiveness.44

Our results also speak to the importance of embeddedness within local partisan networks. First, we find that slum leaders who currently enjoy formal positions within local party organizations report 0.291 more government schemes than those without positions, although this coefficient is only significant at the 90% level. Position-holders are also 14.7 percentage points more likely to have been contacted by a politician. We similarly find the frequency with which slum leaders reported attending party meetings in 2016 positively correlates with their being called by politicians and with the likelihood of slum leaders who contacted politicians reporting they received help (both at the 99% level), and with their likelihood of initiating contact themselves (at the 90% level). Party meeting attendance (measured on a five point scale) is a useful indicator of partisan loyalty for political elites.45 Going from reporting “never attending meetings” (0) to “attending monthly meetings” (2) in 2016 corresponds to a 9.6 percentage point increase in the likelihood of being called by a politician during the lockdown period.

The importance of education and partisan embeddedness in shaping the effectiveness of slum leaders reveals striking continuities with pre-pandemic politics. In prior work, we find slum residents systematically prefer and support more educated slum leaders, due to education being regarded as an important signal of problem-solving ability (Auerbach and Thachil, 2018). Such beliefs appear well founded. We find slum leader education positively and significantly correlates with a range of indicators of everyday problem-solving efficacy measured on our 2016 survey.46

We also find that education and party meeting attendance positively and significantly correspond to the level to which a slum leader is promoted by senior politicians within party organizations. Elite preferences are driven by an understanding that educated slum leaders are more likely to be popular among residents, helping them secure votes during elections, and that slum leaders who attend party meetings are more likely to be loyal to party superiors in contexts marked by high levels of electoral competition and some party-switching (see footnote 22).

Compared to the importance of education and partisan embeddedness, we do not find slum leaders who are official members of the BJP (N = 122), the party in control of the central government and the majority party within the urban municipal council of both Jaipur and Bhopal, to be advantaged in their access to politicians. We also include a measure identifying leaders who are aligned with the provincial state government (N = 115), at the time of the survey (BJP in Bhopal, Congress in Jaipur). We find leaders aligned with state governments are 19.9 percentage points more likely to report being contacted by politicians and are also more likely to report receiving requested assistance. Table S.2 reports further results suggesting the value of state alignment. We find that BJP leaders in Bhopal (who enjoy alignment with the center, state, and local governments) report significantly greater politician responsiveness across these two measures than BJP leaders in Jaipur (who only enjoy center and local alignment). Similarly, we find Congress leaders in Jaipur (who enjoy only state alignment) report significantly greater responsiveness than their co-partisans in Bhopal (who are not aligned with the majority party at any level).

One reason for state-level incumbent alignment appearing relatively more important may be that slum leaders appear to have been most likely to interact with state-level representatives in the context of the pandemic. For example, 99 slum leaders across 43 settlements reported that a politician visited their settlement during the lockdown. 57 slum leaders identified a state-level incumbent (MLA) as the visiting politician, across 27 separate settlements. Zero respondents identified national-level members of parliament (MPs), and only 26 reported a visit by their municipal councilor. Our data cannot speak to why MLAs appear more prominent than local councilors, especially given the importance of the latter in everyday politics. This remains an important question for further exploration.

6. Conclusion

India’s slum leaders have persisted in their problem-solving roles during the coronavirus pandemic. Their informal authority and political networks—constructed long before the announcement of the lockdown—have been deployed to request government relief in the face of widespread joblessness. These political networks have also served as circuits of communication to spread information about pandemic-time government programs. The activities that usually command the time of slum leaders—in particular, petitioning the state for public infrastructure and services—have been largely suspended to tackle more pressing issues of subsistence.

Our findings underscore the importance of not approaching slum settlements as undifferentiated in their vulnerabilities to virus transmission. Variation in pre-pandemic levels of infrastructural development—specifically, the extension of piped water to households—mediate the degree to which residents must congregate in public spaces. Other features of the built space, such as dense living conditions, present problems for social distancing that are more uniform across settlements. Our findings also stress that lower levels of formal education in slum settlements do not inhibit the spread of information about keeping a safe distance from others during the pandemic, even if doing so in practice is so difficult for many residents.

India’s slum leaders are the influential community members that animate calls for bottom-up responses to the pandemic. They are active and widespread across settlements and are focal points of problem solving. Government agencies and civil society organizations will confront these informal leaders while making public health interventions in slum settlements.

Slum leaders, however, should not be romanticized, and their ability to inclusively assist residents over-estimated. Their responsiveness to residents can be uneven and shaped by ethnicity, gender, and partisanship in ways that demand further study.47 These leaders often receive benefits for engaging in slum leadership—party patronage and fees-for-services from residents—introducing the possibility of capture in the distribution of public resources. Women are less likely to become slum leaders, marginalizing female voices in local decision-making. Participatory approaches must anticipate and address these features of slum leadership.

The overwhelmingly male composition of slum leaders highlights an important limitation to our study and a crucial path for future research—to examine the gendered impacts of the pandemic in slums. Pre-pandemic studies demonstrate how women develop problem-solving networks in India’s slums (Snell-Rood, 2015 and Williams et al., 2015), providing a foundation for research into how women individually and collective act to mitigate risk during this period of heightened distress. Understanding pandemic-time vulnerabilities among women in slums—and their efforts to address those vulnerabilities—is a pressing area of research.

Our study revealed that slum leaders are not equally positioned to secure information, make claims, and command government responsiveness in the context of the pandemic. While the average slum leader has higher levels of formal education than the average resident, the former still vary in this crucially important indicator of efficacy. We find that better educated slum leaders tend to possess higher levels of information about government programs designed to soften the economic blow of the lockdown, and are more likely to report being contacted by elite politicians. Slum leaders that are more deeply entrenched in partisan networks also appear to be more likely to contact, and be contacted by political elites, as well as report having received assistance to pandemic-time claims. Such variation demands an acknowledgement that within slums, state-society co-production will, in part, hinge on an efficacy among informal leaders that is uneven across them.

Participatory approaches must take these limits to community leadership into account in their design and implementation. Slum leaders are unlikely to be pushed aside or circumvented in local public health campaigns. They emerge in contexts of pervasive risk to engage government institutions on behalf of residents and drum up electoral support for political parties. They were central to political life in slums before the pandemic, and will continue in this status after the pandemic subsides.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study received IRB approval from American University (IRB-2020-322). The authors thank Nick Barnes, Tanushree Goyal, Naomi Hossain, Anjali Thomas, and Gabrielle Kruks-Wisner for their valuable feedback on the paper, and Shagun Gupta and Ved Prakash Sharma for excellent research assistance. The research was funded by American University and the University of Pennsylvania.

Phone interview with slum leader in Ganpati Nagar, Jaipur, April 29, 2020. Names of respondents and settlements are changed to ensure anonymity.

On property rights in India’s cities, see Banerjee (2002) and Risbud (2014). On urban informality in India, see Roy (2009), Weinstein (2014), Heller et al. (2015), and Rains and Krishna (2020).

On India’s informal economy, see Agarwala (2013).

On community-driven development, see Mansuri and Rao (2013).

See Section 3 for a definition of squatter settlements and a discussion on how we enumerated them in Bhopal and Jaipur.

According to an index compiled by Oxford University, from March 24th until May 6th, India ranked 9th out of 151 countries in its average “stringency.” This index reflects the “number and strictness of government policies, and should not be interpreted as ‘scoring’ the appropriateness or effectiveness of a country’s response” (Coronavirus Government Response Tracker, 2020).

On problem-solving networks in slums, see Auyero (2001).

See our comparison of slum residents and slum leaders in footnote 9 below. Scholars have found education to be a key ingredient in the emergence of intermediaries in rural India as well (Krishna, 2002).

Comparing our sampled 2199 slum residents and 629 slum leaders (described in Section III), we find the latter are more likely than residents to hold modest government jobs (6.7% vs. 1.8%), professional jobs (3.5% vs. 0.4%), and be educators (2.1% vs. 1.0%). Leaders are thus nearly four times more likely to have one of these more connected, higher-status jobs than residents (12.3% vs. 3.2%).

On the use of political intermediaries to gain access to state resources in India’s cities, see Harriss (2005), Jha et al. (2007), Berenschot (2010) and Auerbach (2020).

Drawing on an earlier survey we conducted with 201 current and former ward councilors in Bhopal and Jaipur, we find that 72 percent of surveyed councilors acknowledged that slum residents are often accompanied by slum leaders when visiting them to ask for assistance. Furthermore, 60% of our sampled slum leaders in 2016 name their ward councilor as the person who integrated them into party organizations. In everyday claim-making and party network building within slum settlements, ward councilors are an important set of political actors.

As per the 2011 Census, the average municipal ward populations in Bhopal and Jaipur were 25,689 and 39,557 people, respectively.

On the politics of bottom-up claim making in India, see Kruks-Wisner (2018).

On the “capriciousness” of the Indian state toward the poor, see Ahuja and Chhibber (2012).

The degree to which our findings travel to other types of informal urban settlements represents an important path for future research.

We estimate that just under half (47%, a plurality) of listed “slums” across Bhopal and Jaipur are squatter settlements.

These lists came from multiple government and non-government sources, allowing us to triangulate among them to ensure a comprehensive sample frame. The lists also included “non-notified settlements”—settlements not officially acknowledged by the government, ensuring that our sample frame is not systematically missing newer, less-established settlements.

See Risbud (1988), Roy (2002), and Bhatnagar (2010) for examples of studies that distinguish among types of informal settlements.

We also only include settlements with over 300 residents (roughly 50 households). Housing clusters that stray below this size cease to constitute a settlement.

Selected settlements were first visited to ensure they had not been evicted and fit the category of squatter settlements. If the initially selected settlement was evicted, could not be located, or fell outside the category of squatter settlements, a new one was randomly sampled.

35 of these settlements are in Bhopal and 44 are in Jaipur.

To ensure comparability, we use responses from our 2016 survey for included and excluded slum leaders. We do find shifts in partisan affiliation in our phone sample, although these are reasonably even across the two parties: 9 switched affiliation from Congress to BJP between 2016 and 2020, and 12 switched from BJP to Congress. Overall, the percentage of phone survey respondents (N=321) who are BJP (55%) and Congress (34%) affiliates in 2020 is comparable to equivalent levels for BJP (51%) and Congress (34%) across the full sample (N=629).

Each of these differences is significant at the 95% level (two-tailed).

On deficiencies and intermittency in water supply in India’s cities, see Kumar et al. (2018) and Parikh et al. (2015).

We generated a binary variable for whether respondents believed public water sources are a problem (1) or not (0) for social distancing in their settlement (the latter category combining responses of “moderate problem” and “big problem”). We then conducted a simple difference of means test, comparing respondents in settlements with above average pre-pandemic intra-household access to piped water (based on the sample mean of surveyed residents with water taps in their homes in 2015 as the cutoff) versus those respondents in settlements with below average intra-household access to piped water. The latter are more likely to report this as a problem (27.3%) than the former (14.5%) (p = 0.005; two-tailed).

On the political economy of water and sanitation in India’s slums, see Chidambaram (2020).

Interview with Katar, Bhopal, April 10, 2020.

Respondents could identify multiple sources, which were all recorded.

This provision was made under the Prime Minister Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana scheme to beneficiaries covered under the National Food Security Act, and has been extended until November 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-lockdown-prime-minister-narendra-modi-addresses-nation-on-june-30–2020/article31953944.ece

These are bank accounts designed by India’s Ministry of Finance as part of a financial inclusion initiative launched after the Modi government’s first election victory in 2014. https://www.livemint.com/news/india/woman-jan-dhan-account-holders-to-get-rs-500-per-month-for-next-3-months-11585210124179.html

Under this scheme, beneficiaries were credited with the funds for purchasing the cylinders, which were then to be used to purchase cylinders upon delivery. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/energy/oil–gas/ujjwala-beneficiaries-get-6–8-crore-free-cylinders/articleshow/75868138.cms?from=mdr

“Politician” was broadly conveyed to include ward councilors, MLAs, and MPs.

The results are substantively unchanged if we collapse some and full assistance into one category.

Our results for education (0.015, p-value=0.021) replicate if we restrict the outcome in Column 2 to identify these 86 leaders who explicitly mention being called by politicians to ask how they might assist the slum.

Within our phone sample (N=321) the correlation coefficient between household income and education is only 0.25, among all leaders surveyed in 2016 (N=629), the coefficient is only 0.12. Among the 2199 slum residents we surveyed across the same set of settlements in 2015, the coefficient is 0.19. We read the result on household income in Column 1 with caution, as unlike education, this result does not replicate with any of the alternative outcomes of broker efficacy measured in our 2016 survey (filing petitions, leading protests, obtaining ID cards) noted in Table S.1. Income does not significantly correlate with any of these alternative outcomes.

Leaders who did not profess affiliation to any party were coded as attending zero meetings. However, our results for this variable are unchanged if we exclude these respondents, with the exception that this variable now also registers a positive (0.142) and significant (p=0.003) association with whether a leader called a politician (Column 3).

We estimate the same model used in Column 1 of Table 2, but instead use our full sample of 629 slum leaders surveyed in 2016, and replace the dependent variable with each of the three outcomes listed above. We find education has a positive and significant association with whether a leader reports filing a petition (0.017, p-value=0.000), leading a protest demanding a good or service for residents (0.009, p-value=0.024), and helping residents obtain documents (0.006, p-value =0.036), all within the past year. These findings are substantively important. A standard deviation increase in education (4.7 years for the full 2016 sample) corresponds to a 7.7 percentage point increase in the likelihood of a broker having filed a petition. While acknowledging the limits of self-reported data, we see no reason why more educated brokers would have a greater incentive to overclaim their activities relative to less educated brokers.

Understanding how political networks among slum leaders and slum residents shape the intra-settlement distribution of government relief represents an important area for future research. On slum leader responsiveness to resident requests for help in ‘normal’ times, see Auerbach and Thachil, 2020.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105304.

Interview with Shekhawat, Jaipur, April 29, 2020.

Interview with Sattar, Jaipur, May 6, 2020.

Interview with Rawat, Bhopal, May 4, 2020.

Interview with Kanhaiya, Jaipur, April 28, 2020.

Interview with Ansari, Bhopal, May 4, 2020.

Interview with Khan, Jaipur, April 29, 2020.

Interview with Sharma, Jaipur, April 28, 2020.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Agarwala R. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2013. Informal labor, formal politics, and dignified discontent in India. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja A., Chhibber P. Why the poor vote in india. Studies in Comparative International Development. 2012;47(4):389–410. doi: 10.1007/s12116-012-9115-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach Adam Michael. Neighborhood Associations and the Urban Poor: India’s Slum Development Committees. World Development. 2017;96:119–135. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach Adam Michael. Demanding Development: The Politics of Public Goods Provision in India’s Urban Slums. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach Adam Michael, Thachil Tariq. How Clients Select Brokers: Competition and Choice in India’s Slums. American Political Science Review. 2018;112(4):775–791. doi: 10.1017/S000305541800028X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach Adam Michael, Thachil Tariq. Cultivating Clients: Reputation, Responsiveness, and Ethnic Indifference in India’s Slums. American Journal of Political Science. 2020;64(3):471–487. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Auyero J. Duke University Press; 2001. Poor people’s politics. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee B. In: Holding their ground. Durand-Lasserve A., Royston L., editors. Earthscan; London: 2002. Security of tenure in Indian cities. [Google Scholar]

- Berenschot, W. (2010). Everyday mediation: The Politics of public service delivery in Gujarat, India. Development and Change, 41(5), 883–905. 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2010.01660.x. [DOI]

- Bhan G. University of Georgia Press; 2016. In the public’s interest: Evictions, citizenship, and inequality in contemporary Delhi. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar M. Ritu Publications; Jaipur: 2010. Urban slums and poverty. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, S. (2020). Coronavirus: The Race to Stop the Virus Spread in Asia’s ‘Biggest Slum.’ BBC News, April 6. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-52159986.

- Chatterjee P. Columbia University Press; New York: 2004. Politics of the governed. [Google Scholar]

- Chebet S. Coronavirus: A Father’s Fears in Kenya’s Crowded Kibera Settlement (March 21) 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-51988073 Retrieved from.

- Chidambaram S. How do institutions and infrastructure affect mobilization around public toilets vs. piped water? World Development. 2020;132:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104984. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corburn, J., Vlahov D., Mberu, B., Riley, L., Caiaffa, W.T., & Rashid, S.F. et al. (2020). Slum health: Arresting Covid-19 and improving well-being in urban informal settlements. Journal of Urban Health, 1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus Government Response Tracker (2020). Retrieved from https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/coronavirus-government-response-tracker.

- Das V., Walton M. Political leadership and the urban poor. Current Anthropology. 2015;56(Supplement 11):S44–S54. doi: 10.1086/682420. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit J. Sage; New Delhi: 1997. Poverty, policy and politics in Madras slums. [Google Scholar]

- Gettleman J. India’s Maximum City Engulfed by Coronavirus. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/world/asia/mumbai-lockdown-coronavirus.html Retrieved from.

- Ghertner D.A. Oxford University Press; New York: 2015. Rule by aesthetics. [Google Scholar]

- Government of India . Ministry of Housing and Urban Poverty Alleviation; New Delhi: 2015. Slums in India: A statistical compendium. [Google Scholar]

- Gupte J., Mitlin D. COVID-19: What is not being addressed. Environment and Urbanization. 2020;1–18 doi: 10.1177/0956247820963961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harriss J. Political participation, representation, and the urban poor. Economic and Political Weekly. 2005;40(11):1041–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Heller P., Mukhopadhyay P., Banda S., Sheikh S. Centre for Policy Research; New Delhi: 2015. Exclusion, informality, and predation in the cities of Delhi. [Google Scholar]

- Jha S., Rao V., Woolcock M. Governance in the gullies. World Development. 2007;35(2):230–246. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna A. Columbia University Press; New York: 2002. Active social capital. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna A., Sriram M.S., Prakash P. Slum types and adaptation strategies. Environment and Urbanization. 2014;26(2):568–585. doi: 10.1177/0956247814537958. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruks-Wisner G. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2018. Claiming the state: Active citizenship and social welfare in rural India. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar T., Post A., Ray I. Flows, leaks and blockages in informational interventions. World Development. 2018;106:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.01.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R., Raphael, E., & Snyder, R. (2020). A billion people live in slums. Can they survive the virus? New York Times, April 8. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/opinion/coronavirus-slums.html.

- Mansuri G., Rao V. World Bank Policy Research Report; Washington D.C.: 2013. Localizing development. [Google Scholar]

- Parth, M. N. (2020). Social distancing during the coronavirus? Not when a family of six shares one room. Los Angeles Times, April 7. Retrieved from https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2020-04-07/social-distancing-family-one-room.

- Ostrom E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Development. 1996;24(6):1073–1087. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh P., Fu K., Parikh H., McRobie A., George G. Infrastructure provision, gender, and poverty in Indian slums. World Development. 2015;66:468–486. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rains E., Krishna A. Precarious gains: Social mobility and volatility in urban slums. World Development. 2020;132:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Risbud N. Indian Human Settlements Programme; New Delhi: 1988. Socio-physical evolution of popular settlements and government supports. [Google Scholar]

- Risbud N. In: Inclusive urban planning: State of the urban poor report 2013. Mathur O.P., editor. Oxford University Press; New Delhi: 2014. Experience of security of tenure toward inclusion. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 2002. City Requiem, Calcutta. [Google Scholar]

- Roy A. Why India cannot plan its cities. Planning Theory. 2009;80(1):76–87. doi: 10.1177/1473095208099299. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snell-Rood C. University of California; Berkeley: 2015. No one will let her live: Women’s struggle for well-being in a Delhi slum. [Google Scholar]

- Social Science in Humanitarian Action Key considerations: Covid-19 in Informal urban settlements. 2020. https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/15185/SSHAP_COVID-19_Key_Considerations_Informal_Settlements-final.pdf?sequence=15&isAllowed=y Retrieved from.

- Sur, P., & Mitra, E. (2020). Social Distancing is a Privilege of the Middle Class. For India’s Slum Dwellers, it will be Impossible. CNN, March 30. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/30/india/india-coronavirus-social-distancing-intl-hnk/index.html

- Thachil T. Does Police Repression Spur Everyday Cooperation? Evidence from Urban India. Journal of Politics. 2020;82(4):1474–1489. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat (2020). UN-Habitat Covid-19 Response Plan. Retrieved from https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020/04/final_un-habitat_covid-19_response_plan.pdf.

- UN-Habitat (1982). Survey of Slum and Squatter Settlements. Dublin: Tycooly International.

- Weinstein L. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis: 2014. The durable slum. [Google Scholar]

- Williams G., Devika J., Aandahl G. Making space for women in urban governance? Leadership and claims-making in a Kerala slum. Environment and Planning A. 2015;47(5):1113–1131. doi: 10.1177/0308518X15592312. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.