Abstract

Women with cervical cancer, especially those with advanced disease, appear to experience suffering that is more prevalent, complex, and severe than that caused by other cancers and serious illnesses, and approximately 85% live in low- and middle-income countries where palliative care is rarely accessible. To respond to the highly prevalent and extreme suffering in this vulnerable population, we convened a group of experienced experts in all aspects of care for women with cervical cancer, and from countries of all income levels, to create an essential package of palliative care for cervical cancer (EPPCCC). The EPPCCC consists of a set of interventions, medicines, simple equipment, social supports, and human resources, and is designed to be safe and effective for preventing and relieving all types of suffering associated with cervical cancer. It includes only inexpensive and readily available medicines and equipment, and its use requires only basic training. Thus, the EPPCCC can and should be made accessible everywhere, including for the rural poor. We provide guidance for integrating the EPPCCC into gynecologic and oncologic care at all levels of health care systems, and into primary care, in countries of all income levels.

INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer, a preventable disease, is the fourth most common cancer in women globally and disproportionately afflicts the poor. The International Agency for Research on Cancer estimates that, in 2018, 570,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer and 311,000 women died of it. More than 85% of cases occurred in low- or middle-income countries (LMICs) or among socieconomically disadvantaged communities in high-income countries, and it was the most common cause of cancer-related death in sub-Saharan Africa.1 We described the geographic distribution of cervical cancer and of cervical cancer mortality in more detail elsewhere.2 The WHO Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem, adopted by the 73rd World Health Assembly in August 2020, outlines a comprehensive roadmap toward elimination within the current century that entails achievement of the 90-70-90 targets associated with three main pillars of the strategy: (1) primary prevention through human papillomavirus vaccination, (2) timely screening (by age 35 years and again by age 45 years), and (3) treatment of precancerous lesions and management of invasive cervical cancer, including palliative care.3

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Based on our previous study of the major types, prevalence, severity, and duration of suffering associated with cervical cancer and thus of the need for palliative care, we created an essential package of palliative care for cervical cancer (EPPCCC).

Knowledge Generated

The EPPCCC consists of a set of interventions, medicines, simple equipment, and social supports that can be applied by any clinicians with basic palliative care training. It is designed to be safe, effective for preventing and relieving all types of suffering of inpatients and outpatients with cervical cancer, useful at all levels of health care systems, and affordable even in the poorest settings.

Relevance

By assuring accessibility of the EPPCCC for all patients with cervical cancer at all levels of health care systems, governments can improve patient outcomes, provide financial risk protection for patients and families, and reduce costs to the health care system.

Elsewhere, we also reported our finding that women who died of cervical cancer in 2017 (decedents), and women who had cervical cancer in 2017 but did not die that year (nondecedents), experienced suffering that was more prevalent, complex, and severe than that caused by other malignancies and serious illnesses.2 According to our estimates, decedents had a high prevalence of moderate or severe pain (84%), vaginal discharge (66%), vaginal bleeding (61%), or loss of faith (31%). Among both decedents and nondecedents, we estimated a high prevalence of clinically significant anxiety (63% and 50%, respectively), depressed mood (52% and 38%, respectively), and sexual dysfunction (87% and 83%, respectively). Moderate or severe financial distress was found to be prevalent among decedents, nondecedents, and family caregivers (84%, 74%, and 66%, respectively). More than 40% of decedents and nondecedents were abandoned by their intimate partners. In comparison, the Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief reported a lower average prevalence among decedent and nondecedent patients with cancer of many symptoms including moderate or severe pain (80% and 20%, respectively), bleeding (10% and 2%, respectively), anxiety (38% and 25%, respectively), and depressed mood (47% and 18%, respectively).4 The Lancet Commission did not estimate the prevalence of social or spiritual suffering or types of suffering especially prevalent among women with cervical cancer. We also found that most patients with cervical cancer experienced multiple types of moderate or severe physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering. In total, 258,649 decedents and 2,558,857 nondecedents needed palliative care in 2017, approximately 85% of whom were in LMICs where palliative care is rarely accessible.4–7 These data indicate that palliative care is indispensable for optimum care of women with cervical cancer and their family caregivers. The data also provide an evidence base for design of an essential package of palliative care for this population that can be provided even in the poorest settings.

We convened a group of experienced experts in all aspects of care for women with cervical cancer, and from countries of all income levels, to create an essential package of palliative care for cervical cancer (EPPCCC) based on our research on palliative care needs of women with cervical cancer.8 We proceeded by adapting the essential package of palliative care developed by the Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief4,9 and the WHO essential package of palliative care for primary health care10 to meet the specific needs of women with cervical cancer. The medicines in the EPPCCC were selected based on the 2019 WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for palliative care for adults and children11,12 and on the following criteria:

Necessary to prevent or relieve the specific symptoms or types of suffering most common among women with cervical cancer;

Safe prescription or administration requires a level of professional competency achievable by doctors, clinical officers, assistant doctors, or nurses with basic training in palliative care;

Offer the best balance in their class of accessibility on the world market, clinical effectiveness, safety, ease of use, and minimal cost.

What Is Palliative Care for Women With Cervical Cancer?

The WHO has defined palliative care as care that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.13 In our view, the essence of palliative care is prevention and relief of suffering, and the problems associated with life-threatening illness also may occur with non–life-threatening conditions. For example, women with early-stage, curable cervical cancer may suffer from abandonment, depression, or treatment-related acute pain, and long-term cervical cancer survivors may suffer from chronic pain. The specific types and severity of suffering vary by illness, geopolitical situation, socioeconomic conditions, and culture.14

Palliative care is a people-centered accompanying of patients and their families throughout the illness course, not only at the end of life. It should be integrated with and complement cervical cancer prevention, early diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship care, and it should be provided in all health care settings including hospitals, long-term care facilities, community health centers (CHCs), and in patients' homes.14–16 Doctors, nurses, psychologists, social workers, and community health workers (CHWs) who provide care for patients with cervical cancer should have at least basic training in palliative care that enables them to respond effectively to the specific types of suffering in their setting.9,17 Complex or refractory suffering can be relieved most effectively by specialists in palliative care or other disciplines.

Why Must Palliative Care Be Integrated Into Care and Treatment for Women With Cervical Cancer?

Medical and moral imperatives

The human right to the highest attainable standard of health entails a human right to pain relief and palliative care for anyone with serious illness-related suffering.18–20 The human right of palliative care is especially compelling for women with cervical cancer because their suffering often is more frequent, severe, complex, or refractory than that of people with other serious illnesses. This is true not only because of the physical symptoms of cervical cancer, adverse effects of treatment, and multisystem involvement of advanced disease, but also because cervical cancer disproportionately affects the poor who often lack access to prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment, who already have late-stage disease at diagnosis in nearly 80% of cases, who often lack financial resources to access treatment when it is available, and who are at risk for stigmatization in some places.

Human rights necessarily correspond to responsibilities of governments to respect these rights. In 2014, the World Health Assembly resolved that palliative care is an ethical responsibility of health systems. 15 It is a responsibility in part because it is feasible anywhere. Most suffering because of serious illnesses, including cervical cancer, can be relieved with inexpensive, safe, and effective medicines, equipment, therapies, and social supports provided by clinicians with basic palliative care training, including those working at community level where most patients are and wish to remain.9

Financial benefits for patients, their families, and health care systems

Well-planned integration of basic palliative care into public health care systems can improve their performance and promote universal health coverage (UHC) while also reducing costs.4 Data from high-income countries and upper-middle–income countries show that, when palliative care is integrated into health care systems and includes home care, it can reduce length of stay in hospitals and reduce unnecessary hospital admissions for symptom relief by enabling many patients to remain comfortable at home or in the community.9 Hence, palliative care can reduce hospital overcrowding and costs for overburdened health systems and provide financial risk protection for patients and their families.4,21–31 Within hospitals, the presence of a palliative care inpatient unit or consultation service also can improve patients' quality of life and reduce costs, not only by reducing length of stay but also by reducing use of expensive life-sustaining treatments and cancer chemotherapy near the end of life likely to be more harmful than beneficial.32–35 Although data on cost effectiveness of palliative care in low- and lower-middle–income countries is scant, it appears that the start-up costs necessary to integrate a basic package of palliative care services into health care systems—investment in policy development, essential medicine procurement, training, and increased staffing—may yield even better returns over time by reducing costs for health care systems, reducing dysfunctional overuse of hospitals and nonbeneficial interventions, improving patients' quality of life without shortening it, protecting patient's families from impoverishment, and improving satisfaction of family caregivers.4,26,36–38

UHC, as defined by WHO, requires that all individuals and communities receive the full spectrum of essential, quality health services they need, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care, without suffering financial hardship.39 Because palliative care is an essential part of UHC, UHC is achievable only if palliative care is fully integrated into health care systems so as to be universally accessible. In low-income settings where palliative care is not widely accessible, when further treatment of serious illnesses is no longer available, affordable, or desired, patients often are sent home with no further health care coverage. In these situations in particular, UHC is achievable only through implementation of community- and home-based palliative care.10,40,41

Thus, it is not only medically and morally imperative, but also financially advantageous, that at least a basic package of cost-effective palliative care be integrated with treatment of cervical cancer and universally accessible to women with cervical cancer at all levels of health care systems.9,10,15,42,43

ESSENTIAL PACKAGE OF PALLIATIVE CARE FOR CERVICAL CANCER

The EPPCCC—for all women with cervical cancer and their family caregivers—is intended to provide health care policymakers, planners, implementers, and managers from countries of all income groups, as well as clinicians and advocates for palliative care and cervical cancer care, with the information necessary to integrate appropriate palliative care into all levels of care for women with cervical cancer and their family caregivers.8 Specifically, the EPPCCC is designed:

To improve patient outcomes by preventing and relieving the most common and severe types of physical, psychological, social, and spiritual suffering associated with cervical cancer;

To be the minimum package that should be accessible in hospitals of all levels and at CHCs;

To be made universally accessible free of charge by public health care systems in LMICs yet also to reduce costs for health care systems by reducing hospital admissions and length of stay;

To provide financial risk protection for patients and their families; and

To promote UHC.

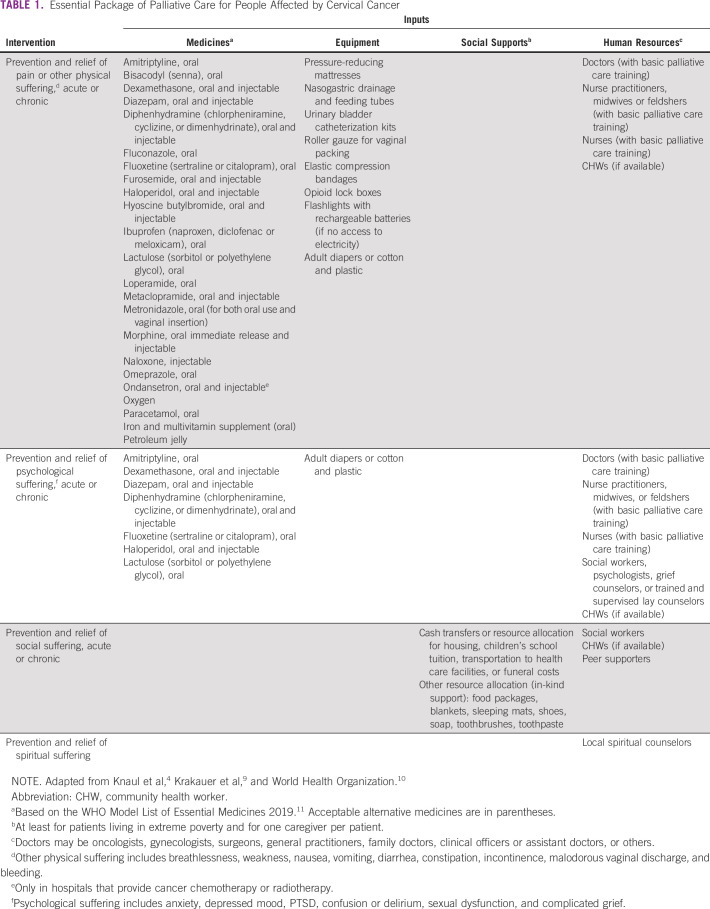

The EPPCCC consists of (Table 1):

A set of four interventions;

A set of safe, effective, inexpensive, off-patent, and widely available medicines;

Simple and inexpensive equipment;

Basic social supports; and

The human resources needed to provide the medicines, equipment, and social supports effectively and safely.

TABLE 1.

Essential Package of Palliative Care for People Affected by Cervical Cancer

Interventions

Prevention and relief of pain and other physical symptoms

In most cases, pain and other physical suffering can be adequately relieved with a set of safe, effective, and inexpensive medicines that can be prescribed responsibly by doctors, clinical officers, or assistant doctors with basic training in palliative care or by palliative care nurse specialists.

Morphine, in oral fast-acting and injectable preparations, is the most clinically important of the essential palliative care medicines and should be accessible by prescription for inpatients and outpatients with appropriate need at any hospital.44 In general, at least oral fast-acting morphine should be accessible by prescription at CHCs. All doctors who provide care for patients with cervical cancer, including primary care doctors, should complete at least basic palliative care training and, on that basis, receive legal authorization to prescribe oral and injectable morphine for inpatients and outpatients in any dose necessary to provide adequate relief as determined by the patients.10,15

Although ensuring access to morphine for anyone in need is imperative, it also is necessary to take reasonable precautions to prevent diversion and nonmedical use. Model guidelines for this purpose are available.45

Neuropathic pain is common in advanced cervical cancer and often cannot be adequately controlled with an opioid. In this situation, oral amitriptyline and oral or injectable dexamethasone can be used as adjuvants to improve analgesia if there are no absolute contraindications to their use. To reduce or eliminate malodorous vaginal discharge, the patient can be instructed to place a metronidazole tablet 250 mg intravaginally twice per day and advance it gently to minimize risk of bleeding. In addition, two metronidazole 250 mg tablets can be crushed to a fine powder and sprinkled onto the pads used to absorb vaginal discharge each time the pad is changed. Among the other essential palliative medicines are oral and injectable haloperidol and oral fluoxetine or another selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (see section below on prevention and relief of psychological suffering).

Essential equipment includes locked safe-boxes for opioids that should be secured to a wall or immovable object, elastic compression bandages for leg edema, and urinary bladder catheter kits to manage bladder dysfunction or outlet obstruction. Eco-friendly adult diapers, or cotton and large plastic bags to make adult diapers, also are essential to manage urinary or fecal incontinence because of vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas. In countries where plastic bags are prohibited as part of laudable environmental protection initiatives, specialized medical use should be permitted.

The necessary human resources depend primarily on the level and type of the health care delivery site and on the competency in palliative care of staff members rather than their professional designations. Any medical doctor, clinical officer, or assistant doctor with basic palliative care training should be able to prevent or relieve most pain and other physical suffering and to diagnose and treat uncomplicated anxiety disorders, depression, or delirium. In some places, nurse practitioners, midwives, or feldshers with basic palliative care training also can assume these tasks. CHWs can have a crucial role in palliative care by visiting patients and family caregivers frequently at home and reporting any problems (see section below on integration of palliative care for women with cervical cancer into primary care).

Prevention and relief of psychological suffering

Among women with cervical cancer, the high prevalence of anxiety, depressed mood, sexual dysfunction, and other psychological disorders, the suffering they cause, and the association of untreated psychological disorders with decreased treatment adherence necessitate assiduous efforts to prevent, promptly diagnose, and treat them.2,46–50 Family members of patients with cancer also may experience psychological distress because of fear of losing a loved one, caregiving burden, poverty because of loss of income and medical expenses, or prolonged grief disorder after the patient's death.51,52

A small set of screening tools, counseling techniques, and medicines should be used not only by palliative care specialists but also by oncologists, gynecologists, and primary care doctors. Two practical screening tools for psychological and other types of distress are the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale and the distress thermometer of the US National Comprehensive Cancer Network.53–55 Among the medicines in the EPPCCC are oral and injectable haloperidol and oral fluoxetine or another SSRI. Both have multiple essential uses in palliative care and are safe and easy to prescribe. For example, haloperidol is the first-line medicine in many cases for relief of nausea, vomiting, agitation, delirium, and anxiety. An SSRI, such as fluoxetine, is the first-line pharmacotherapy for depressed mood or persistent anxiety, both of which are common among women with cervical cancer and their family caregivers. Any doctor who provides primary care should be prepared and permitted to prescribe these medicines. Patients with severe or refractory psychiatric illnesses should be referred for specialist psychiatric care whenever possible.

Nonpharmacologic interventions for psychological distress include psychotherapy; supportive counseling; psychoeducation; relaxation, art, music, and movement therapies; and guided imagery techniques.56 The goals of these interventions are:

to improve coping skills and resilience,

to reduce emotional distress,

to reduce feelings of depression and anxiety,

to improve body image and to help the patient to regain self esteem,

to enhance personal growth,

to strengthen the personal and social resources of the patient and her caregivers, and

to improve quality of life

Not only doctors, nurses, psychologists, and social workers, but also CHWs can be trained to provide simple, culturally appropriate supportive counseling and even psychotherapy for depression.57–59

Treatment of psychological suffering may have the added benefit of improving control of the patient's pain, fatigue, nausea, or other physical symptoms. It also can facilitate advance care planning, discussion of goals of care and treatment options, and bereavement.56,60

Prevention and relief of social suffering

Social supports are especially important for women with cervical cancer in light of the finding of a high prevalence of financial difficulties, discrimination, stigmatization, social isolation, and abandonment in this population.2 Social support for patients and family caregivers living in poverty is needed to ensure that their most basic needs are met such as food, housing, and transport to health care facilities, and to promote dignity.9,10 These supports should include, as appropriate, basic food packages, housing or cash payments for housing, transportation vouchers for visits to clinics or hospitals for the patient and a caregiver, and in-kind support, such as blankets, sleeping mats, shoes, soap, toothbrushes, and toothpaste.61,62 This type of social support helps to ensure that patients can access and benefit from medical care and should be accessible by any patient, and not only those in need of palliative care or symptom control. Patients should be asked about perceived discrimination or stigmatization, and counseling should be made accessible by social workers with academic training or experience in addressing these problems. Provision also should be made for women facing discrimination in housing, employment, or education, and for those abandoned by their intimate partners or families, to access free or affordable legal services. Psychological and social supports should be closely coordinated. In addition, because culturally appropriate burial can be a major financial burden for families and inability to provide a funeral can become a chronic emotional burden, locally adequate funds for a simple funeral should be made accessible for families living in extreme poverty.

Prevention and relief of spiritual suffering

Spiritual distress is prevalent in advanced cancer,63 yet available evidence suggests that this distress typically is not adequately addressed.64–66 Serious illness and related suffering may catalyze meaning-making but also a questioning of religious belief and of the meaning of life.67,68 Illness and suffering may be interpreted as divine punishment or a result of bad magic.69,70 Stigma associated with disease of the genitals, malodorous vaginal discharge, or concurrent HIV infection may evoke feelings of humiliation, guilt, or shame.71,72 This suffering or shame may lead to moral despair, anger with a higher power, loss of faith, or loss of the ability to find meaning in life. Family caregivers also may experience spiritual despair.73,74

Hospitals of all levels, CHCs, and palliative care or hospice teams should establish and maintain collaborative relationships with local spiritual counselors representing the main religious or spiritual communities in the catchment area who can be called upon to provide spiritual support when requested by a patient or family. Any doctor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker, regardless of spiritual orientation, can screen for spiritual distress by asking patients with serious illnesses about sources of meaning and hope and connectedness with others.75 If there is concern about spiritual distress based on the screening, or if the patient requests spiritual counseling, a local spiritual care provider can be consulted. A doctor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker should speak with the potential spiritual provider in advance to explain the emotional delicacy of such situations and to minimize the risk of inadvertent exacerbation of a patient's feelings of guilt or shame from spiritual counseling. Ideally, the spiritual provider first should conduct a more thorough spiritual assessment using an existing assessment model adapted to local culture.76–79 Based on the assessment, an appropriate plan of spiritual care can be developed. Sometimes, this may entail involvement of traditional healers. Spiritual support may help some patients or their family caregivers to make meaning of the illness, to cope better, to feel less afraid or ashamed, or to feel more at peace.70,80–82

Integrating Palliative Care Into Standard Practice of Gynecologic Oncology

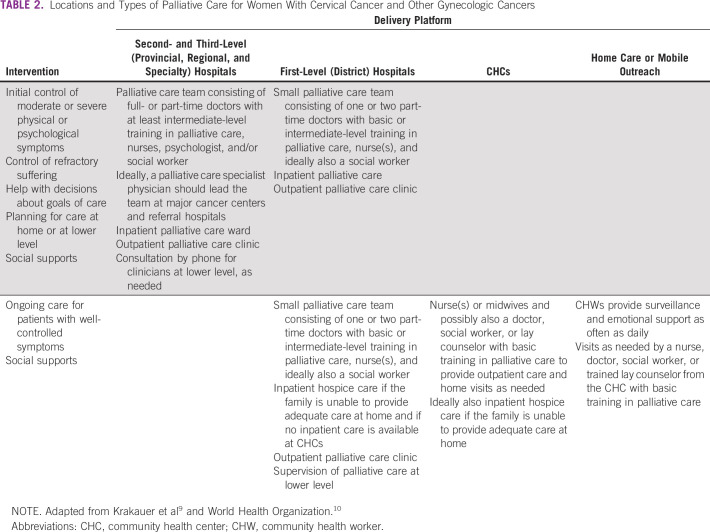

Locations of care

The EPPCCC should be accessible wherever women with cervical cancer seek or receive care as shown in Table 2.15,83 In LMICs, where cervical cancer typically is diagnosed at an advanced stage at a provincial or regional general hospital or cancer center (second- or third-level hospital), all such hospitals should have a palliative care department or team with capacity to assess all newly diagnosed inpatients and outpatients for physical, psychological, social, or spiritual suffering. These teams also should be able to initiate palliative care, to integrate it with disease-modifying treatments early as part of the overall treatment plan, to create a plan for continued palliative care at lower levels or at home for outpatients and for inpatients before discharge, and to control refractory symptoms that cannot be controlled at lower levels.84,85 When difficult decisions about goals of care must be made, palliative care team members should be prepared to assist.

TABLE 2.

Locations and Types of Palliative Care for Women With Cervical Cancer and Other Gynecologic Cancers

All district (first-level) hospitals should have at least one or two doctors and nurses with at least basic palliative care training who are assigned to provide basic palliative care with the EPPCCC as one of their responsibilities. WHO has published a model training curriculum in basic palliative care for doctors, clinical officers, or assistant doctors lasting 30-40 hours.10,86 With this training, they will be capable of addressing the needs of inpatients and outpatients with uncomplicated palliative care needs. These needs include adjustment in doses of opioid analgesics or other medicines to control symptoms that are uncomplicated but changing because of disease progression or treatment side effects. For dying patients whose symptoms are adequately controlled but whose families are unable to care for them at home, these teams also can provide inpatient end-of-life (hospice) care if the CHCs nearest the patient's home are unable to do so. Palliative care teams at district level also have a crucial role in supervising and providing backup for palliative care providers at community level.

At least two clinicians at every CHC—ideally at least one doctor and one other clinician—also should have at least basic palliative care training, and as soon as possible, all primary care clinicians should have this training. Per WHO, basic palliative care training lasting at least 30 hours should enable trainees to provide basic outpatient symptom control and supervise CHWs who visit patients at home.10

Standard operating procedures should be in place to assure easy communication and smooth transfer of patients between levels of the health care system.10

Basic and more advanced courses in palliative care are offered in some LMICs in all regions by hospitals, universities, or nongovernmental organizations. A directory of palliative care training programs is maintained by the International Association for Hospice and Palliative care.87 However, the need for all levels of palliative care training in LMICs remains high, and specialist training program are available only in a few countries. Likewise, even basic palliative care services and many essential palliative medicines, including morphine, remain unavailable to most inpatients and outpatients in LMICs.6

Assessment for physical, psychological, social, or spiritual suffering is indicated at the time of diagnosis of cervical cancer of any stage, and palliative care should be initiated based on the assessment.10 In LMICs, pain, vaginal discharge, vaginal bleeding, anxiety, depression, sexual dysfunction, or social distress often are present at the time of diagnosis and require palliation, regardless of the treatment plan and whether or not cure is possible.2 As the treatment plan is formulated, palliative care also entails helping patients and possibly their families, as appropriate, to understand the illness and treatment plan, helping to assure that the patient has the resources to adhere to the treatment, providing emotional support, and sometimes helping to reach an agreement between the patient, family, and treatment team on the optimum goal(s) of care in light of the clinical situation and the patient's values.

During treatment with radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or surgery, palliative care entails continued relief of any disease-related symptoms but also prevention and relief of any adverse effects of treatment, some of which may persist for months or years after treatment is completed. It also entails continued psychological, social, and spiritual support as needed to maximize the patient's ability to cope with the illness and adhere to treatment.

All gynecologists who care for patients with cervical cancer and all oncologists should have intermediate-level palliative care training (defined by WHO as 60-80 hours) and be capable of integrating palliative care with disease treatment along with nurses and psychologists or social workers.10 Provision of effective palliative care does not always require much time from busy oncologists or gynecologists but rather a recognition of its importance and adequate training. Plans should be made for palliative care teams at major cancer centers in LMICs to be led as soon as possible by palliative care specialists skilled at relieving even complex and refractory symptoms. Elsewhere, we describe an augmented package of palliative care that should be made available whenever feasible at major cancer centers for specialists in palliative medicine and other disciplines to treat the most severe or refractory suffering.85 Palliative care specialists also should participate in person or virtually in tumor board discussions. However, most palliative care can and should be provided by other medical specialists and by primary care clinicians.

Integration of palliative care for women with cervical cancer into primary care

All 194 WHO member states have agreed that palliative care is an essential function of primary care and should be integrated with disease prevention and treatment and rehabilitative services.10,15,88,89 Thus, all primary care doctors and other primary care clinicians, including family medicine specialists, should be required to undergo at least basic palliative care training (30-40 hours). With this training, and with the EPPCCC, primary care clinicians at district (first-level) hospitals and CHCs will be able to provide integrated, people-centered health services for women suffering from or at risk for cervical cancer including human papillomavirus vaccination, cervical cancer screening, relief of uncomplicated disease-related symptoms and adverse effects of treatment, psychosocial and adherence support, and basic end-of-life care.89-92 Standard operating procedures should be in place to enable primary care clinicians to consult colleagues at higher levels about difficult cases and to transfer patients when necessary.10 Doctors and other clinicians at CHCs also can supervise CHWs or volunteers who visit patients in need of palliative care at home.10 With as little as 3 to 6 hours of training, CHWs or volunteers not only can provide important emotional support, but also recognize uncontrolled symptoms and improper use of medicines, identify unfulfilled basic needs for food, shelter, or clothing, and generally serve as the eyes and ears of their clinician-supervisors at a CHC by alerting them via mobile phone to such problems.9,10 Where there are no CHWs, provision should be made for clinicians from CHCs to visit patients at home. Health care systems also should plan to enable busy clinicians from CHCs to make home visits when a visit may enable a patient to remain comfortable at home rather than go to the hospital.

End-of-life care

When any further disease-modifying treatment is deemed unlikely to provide benefit in the context of the patient's values, or likely would be more harmful than beneficial, a conversation about goals of care with the patient and/or family is necessary. The prognostic understanding of the patient or family should be explored gently and corrected as needed and as culturally appropriate, and it should be explained that care to maximize comfort and quality of life may be the best that medicine can offer under the circumstances. Whether this situation occurs in the hospital or in the community, good end-of-life care should include

Aggressive relief of pain and any other physical or psychological symptoms;

Anticipation of symptoms that might worsen or develop in the future, and preparation of a plan to protect the patient from resultant suffering;

Decisions about location of care and under what circumstances, if any, transfer to higher or lower level should be considered;

Psychological, social, or spiritual support as needed.

If there is agreement on comfort as the sole goal of care for a patient in the hospital, and if one or more symptoms are not well controlled, the patient should remain in the hospital or in an inpatient hospice or palliative care facility at least until a regimen is found to maintain comfort. For patients likely to die within a few days or on the way home, discharge should be considered only if the patient insists after understanding the risks or if dying at home appears to be of over-riding importance according to the patient's values. When discharge is being considered, the home situation should be carefully assessed to make sure that adequate palliative care can be provided in the home and that the well-being of family caregivers would not be jeopardized.93 An alternative would be for terminally ill patients whose symptoms are well controlled but whose families cannot care for them at home to be allowed to receive end-of-life care at a CHC that is staffed around the clock. This would enable the family to visit without having the burden of providing 24-hour care and would be less expensive than having the patient in a hospital.9,10

Women with advanced cervical cancer are at risk for various sudden and/or severe symptoms including pain crisis, bowel obstruction, and massive vaginal hemorrhage with exsanguination. When planning the location of end-of-life care, the risk of these or other severe complications should be considered carefully with the patient and/or family. Elsewhere, we describe interventions to prevent or control massive hemorrhage as part of an augmented package of palliative care for women with cervical cancer that should be made available as soon as feasible in major cancer centers.85 However, where such interventions are not available or desired, or if the patient insists on going home despite uncontrolled symptoms or high risk of sudden or severe suffering, every effort still should be made to inform and equip community-based primary care clinicians to provide the best possible palliation. In particular, if there is a significant risk of massive hemorrhage, community providers and family members should be instructed to have many dark towels available to catch the blood and given the following guidance on how to respond when bleeding occurs:

A primary care provider should go to the patient's home and reassure the patient and family members that the situation will be managed.

Any CHW or volunteer who knows the family should go to the home to offer accompaniment to the patient and family through the event.

The dark towels should be used to catch the blood and replaced when soaked.

An intravenous (IV) or subcutaneous catheter should be placed promptly, and any pain or anxiety of the patient should be treated aggressively with IV or subcutaneous opioid and benzodiazepine.

Any dyspnea or chest pain that occurs as the patient exsanguinates should be relieved aggressively with IV opioid.

Vaginal packing with roller gauze may be considered but often exacerbates discomfort.

When a decision is made that the sole goal of care will be comfort, some women may find meaning or solace in preparing a simple legacy for their children or other family members such as a letter or memory box. Local volunteer spiritual supporters should be sought to provide culturally appropriate spiritual support if requested by the patient, and bereavement support should also be made accessible.10,94

In conclusion, based on available data of palliative care needs among women with cervical cancer, we created an EPPCCC that consists of safe, effective, readily available, and inexpensive medicines, simple equipment, and social supports that can and should be administered as part of standard gynecologic, oncologic, and primary care by clinicians with at least basic training in palliative care. Integration of the EPPCCC into care for women with cervical cancer should be part of the overall integration of palliative care into health care systems as urged by WHO that is indispensable to achievement of UHC. However, women with cervical cancer appear to bear an unusually high burden of suffering that calls for a vigorous response from public health officials, gynecologists, oncologists, and primary care providers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to the following for helpful comments on drafts of the paper: Sally Agallo Kwenda, Esther Cege-Munyoro, Liliana de Lima, Lailatul Ferdous, Rei Haruyama, Kim Hulscher, Elizabeth Mattfeld, Diana Nevzorova, MR Rajagopal, Julie Torode, and Linda Van Le.

Eric L. Krakauer

Employment: (I) My wife is employed by Inform Diagnostics and Foundation Medicine

Xiaoxiao Kwete

Employment: Yaozhi Co Ltd

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Expat Inc

Research Funding: Roche

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: (I) My husband Patrick Kwete has a patent called Personalized Medical Treatment Provision Software (https://patents.google.com/patent/US20130080425A1/en)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Expat Inc

Shekinah N. Elmore

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Teladoc

Consulting or Advisory Role: Best Doctors Inc, Wild Type

Annette Hasenburg

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Med Update, Pfizer, Roche, Streamedup!, Tesaro, MedConcept, LEO Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: PharmaMar, Tesaro, Roche, AstraZeneca, LEO Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline/MSD

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, MedConcept, Roche, Streamedup!, Tesaro, MedUpdate, Pfizer

Mihir Kamdar

Leadership: Amorsa Therapeutics

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amorsa Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Medtronic, Fern Health

Cristiana Sessa

Consulting or Advisory Role: Basilea

Ted Trimble

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Inovio Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Frantz Viral Therapeutics

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

E.F., C.V., and E.L.K. are staff members or consultants of the WHO. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the decisions, policy, or views of the WHO.

SUPPORT

Funding was provided by the WHO and Unitaid.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Eric L. Krakauer, Xiaoxiao Kwete, Gauhar Afshan, Lawrence F. Borges, Raimundo Correa, Nahla Gafer, Annekathryn Goodman, Cherian Varghese, Elena Fidarova

Administrative support: Khadidjatou Kane, Elena Fidarova

Provision of study materials or patients: Khadidjatou Kane, Raimundo Correa, Mamadou Diop, Nahla Gafer, Maryam Rassouli

Collection and assembly of data: Eric L. Krakauer, Khadidjatou Kane, Xiaoxiao Kwete, Nahla Gafer, Annette Hasenburg, Mihir Kamdar, Suresh Kumar, Maryam Rassouli, Elena Fidarova

Data analysis and interpretation: Eric L. Krakauer, Khadidjatou Kane, Xiaoxiao Kwete, Lisa Bazzett-Matabele, Danta Dona Ruthnie Bien-Aimé, Sarah Byrne-Martelli, Stephen Connor, C. R. Beena Devi, Mamadou Diop, Shekinah N. Elmore, Nahla Gafer, Surbhi Grover, Annette Hasenburg, Kelly Irwin, Mihir Kamdar, Quynh Xuan Nguyen Truong, Tom Randall, Cristiana Sessa, Dingle Spence, Ted Trimble, Elena Fidarova

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by the authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/go/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Eric L. Krakauer

Employment: (I) My wife is employed by Inform Diagnostics and Foundation Medicine

Xiaoxiao Kwete

Employment: Yaozhi Co Ltd

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Expat Inc

Research Funding: Roche

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: (I) My husband Patrick Kwete has a patent called Personalized Medical Treatment Provision Software (https://patents.google.com/patent/US20130080425A1/en)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Expat Inc

Shekinah N. Elmore

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Teladoc

Consulting or Advisory Role: Best Doctors Inc, Wild Type

Annette Hasenburg

Honoraria: AstraZeneca, Med Update, Pfizer, Roche, Streamedup!, Tesaro, MedConcept, LEO Pharma

Consulting or Advisory Role: PharmaMar, Tesaro, Roche, AstraZeneca, LEO Pharma, GlaxoSmithKline/MSD

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca, MedConcept, Roche, Streamedup!, Tesaro, MedUpdate, Pfizer

Mihir Kamdar

Leadership: Amorsa Therapeutics

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Amorsa Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Medtronic, Fern Health

Cristiana Sessa

Consulting or Advisory Role: Basilea

Ted Trimble

Consulting or Advisory Role: Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Inovio Pharmaceuticals

Research Funding: Frantz Viral Therapeutics

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arbyn M Weiderpass E Bruni L, et al. : Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health 8:e191-e203, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krakauer EL Kwete X Kane K, et al. : Cervical cancer-associated suffering: Estimating the palliative care needs of a highly vulnerable population. JCO Glob Oncol 7:862-872, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization : World Health Assembly adopts global strategy to accelerate cervical cancer elimination, WHO. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/19-08-2020-world-health-assembly-adopts-global-strategy-to-accelerate-cervical-cancer-elimination#:∼:text=The%20World%20Health%20Assembly%20has,detected%20early%20and%20managed%20effectively

- 4.Knaul FM Farmer PE Krakauer EL, et al. : Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief: An imperative of universal health coverage. Lancet 391:1391-1454, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark D Baur N Clelland D, et al. : Mapping levels of palliative care development in 198 countries: The situation in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage 39:794-807, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connor SR. (ed): Global Atlas of Palliative Care (ed 2). London, United Kingdom, Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance and Geneva: World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on-end-of-life-care [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization : Assessing National Capacity for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Report of the 2019 Global Survey. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/ncd-ccs-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization : WHO Framework for Strengthening and Scaling-Up of Services for the Management of Invasive Cervical Cancer. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003231 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krakauer EL Kwete X Verguet S, et al. : Palliative care and pain control, in Jamison DT Gelband H Horton S, et al. (eds): Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition, Volume 9: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. Washington, DC, World Bank, 2018, pp 235-246. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/28877/9781464805271.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization : Integrating Palliative Care and Symptom Relief Into Primary Health Care: A WHO Guide for Planners, Implementers and Managers. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274559 [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization : WHO Model List of Essential Medicines—21st List, 2019. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHOMVPEMPIAU2019.06 [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization : WHO Model List of Essential Medicines for Children—7th List, 2019. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHOMVPEMPIAU201907 [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization : WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2002. https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krakauer EL: Palliative care, toward a more responsive definition, in MacLeod RD, Block L. (eds): Textbook of Palliative Care. Cham, Switzerland, Springer Nature, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization : World Health Assembly Resolution 67.19: Strengthening of Palliative Care as a Component of Comprehensive Care Throughout the Life Course. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2014. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shulman LN Mpunga T Tapela N, et al. : Bringing cancer care to the poor: Experiences from Rwanda. Nat Rev Cancer 14:815-821, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization : Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2016. https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brennan F: Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage 33:494-499, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lohman D, Schleifer R, Amon JJ: Access to pain treatment as a human right. BMC Med 8:8, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization : Amended Constitution of the World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2006. http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albanese TH Radwany SM Mason H, et al. : Assessing the financial impact of an inpatient acute palliative care unit in a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Palliat Med 16:289-294, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chalkidou K Marquez P Dhillon PK, et al. : Evidence-informed frameworks for cost-effective cancer care and prevention in low, middle, and high-income countries. Lancet Oncol 15:e119-e131, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis MP Temel JS Balboni T, et al. : A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses. Ann Palliat Med 4:99-121, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DesRosiers T Cupido C Pitout E, et al. : A hospital-based palliative care service for patients with advanced organ failure in sub-Saharan Africa reduces admissions and increases home death rates. J Pain Symptom Manage 47:786-792, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanson LC Usher B Spragens L, et al. : Clinical and economic impact of palliative care consultation. J Pain Symptom Manage 35:340-346, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hongoro C, Dinat N: A cost analysis of a hospital-based palliative care outreach program: Implications for expanding public sector palliative care in South Africa. J Pain Symptom Manage 41:1015-1024, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosoiu D, Dumitrescu M, Connor SR: Developing a costing framework for palliative care services. J Pain Symptom Manage 48:719-729, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postier A Chrastek J Nugent S, et al. : Exposure to home-based pediatric palliative and hospice care and its impact on hospital and emergency care charges at a single institution. J Palliat Med 17:183-188, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabow MW: What are the arguments that show outpatient palliative care is beneficial to medical systems? in Goldstein NE, Morrison RS. (eds): Evidenced-Based Practice of Palliative Care. Amsterdam, the Netherlands, Elsevier, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith S Brick A O'Hara S, et al. : Evidence on the cost and cost effectiveness of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat Med 28:130-150, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramsey SD Bansal A Fedorenko CR, et al. : Financial Insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 34:980-986, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung HM Kim J Heo DS, et al. : Health economics of a palliative care unit for terminal cancer patients: A retrospective cohort study. Support Care Cancer 20:29-37, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.May P, Normand C, Morrison RS: Economic impact of hospital inpatient palliative care consultation: Review of current evidence and directions for future research. J Palliat Med 17:1054-1063, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morrison SR Penrod JD Cassel BJ, et al. : Cost savings associated with US hospital palliative care consultation programs. Arch Intern Med 168:1783-1790, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith TJ, Cassel JB: Cost and non-clinical outcomes of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 38:32-44, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elsayem A Swint K Fisch MJ, et al. : Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: Clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol 22:2008-2014, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ratcliff C Thyle A Duomai S, et al. : Poverty reduction in India through palliative care: A pilot project. Indian J Palliat Care 23:41-45, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reid EA Kovalerchik O Jubanyik K, et al. : Is palliative care cost effective in low-income and middle-income countries? A mixed methods systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 9:120-129, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization : Universal Health Coverage (UHC). Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krakauer EL: Just palliative care: Responding responsibly to the suffering of the poor. J Pain Symptom Manage 36:505-512, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krakauer EL Wenk R Buitrago R, et al. : Opioid inaccessibility and its human consequences: Reports from the field. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 24:239-243, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization : Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer as a Public Health Problem. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240014107 [Google Scholar]

- 43.World Health Organization : WHO Report on Cancer: Setting Priorities, Investing Wisely and Providing Care for All. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-report-on-cancer-setting-priorities-investing-wisely-and-providing-care-for-all [Google Scholar]

- 44.World Health Organization : WHO Guidelines for the Pharmacological and Radiotherapeutic Management of Cancer Pain in Adults and Adolescents. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2019. https://www.who.int/ncds/management/palliative-care/cancer-pain-guidelines/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Joranson D, Maurer M, Mwangi-Powell F. (eds): Guidelines for Ensuring Patient Access to, and Safe Management of, Controlled Medicines. Kampala, Uganda, African Palliative Care Association, 2010. https://www.africanpalliativecare.org/images/stories/pdf/patient_access.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen RW, Quinlivan JA: Preventing anxiety and depression in gynaecological cancer: A randomised controlled trial. BJOG 109:386-394, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sedjo RL, Devine S: Predictors of non-adherence to aromatase inhibitors among commercially insured women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 125:191-200, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osann K Hsieh S Nelson EL, et al. : Factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: Implications for clinical care and clinical trials. Gynecol Oncol 135:266-272, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang YL Liu L Wang XX, et al. : Prevalence and associated positive psychological variables of depression and anxiety among Chinese cervical cancer patients: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 9:e94804, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huffman LB Hartenbach EM Carter J, et al. : Maintaining sexual health throughout gynecologic cancer survivorship: A comprehensive review and clinical guide. Gynecol Oncol 140:359-368, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sklenarova H Krümpelmann A Haun MW, et al. : When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 121:1513-1519, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kleine AK Hallensleben N Mehnert A, et al. : Psychological interventions targeting partners of cancer patients: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 140:52-66, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schildmann EK Groeneveld EI Johannes Denzel J, et al. : Discovering the hidden benefits of cognitive interviewing in two languages: The first phase of a validation study of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale. Palliat Med 30:599-610, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donovan KA Grassi L McGinty HL, et al. : Validation of the distress thermometer worldwide: State of the science. Psychooncology 23:241-250, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riba MB Donovan KA Andersen B, et al. : Distress management, version 3.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 17:1229-1249, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weis J, Hasenburg A: Psychological support, in Ayhan A, Reed N, Gultekin M. (eds): Textbook of Gynaecological Oncology (ed 3). Copenhagen, Denmark, Gunes Publishing, 2016, pp 1495-1499 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Belkin GS Unützer J Kessler RC, et al. : Scaling up for the “bottom billion”; “5×5” implementation of community mental health care in low-income regions. Psychiatr Serv 62:1494-1502, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patel V: Where There Is No Psychiatrist: A Mental Health Care Manual. London, United Kingdom, Gaskell, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weobong B Weiss HA McDaid D, et al. : Sustained effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the healthy activity programme, a brief psychological treatment for depression delivered by lay counsellors in primary care: 12-month follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. PLoS Med 14:e1002385, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rogers JL, Perry LM, Hoerger M: Summarizing the evidence base for palliative oncology care: A critical evaluation of the meta-analyses. Clin Med Insights Oncol 14:1179554920915722, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carrillo JE Carrillo VA Perez HR, et al. : Defining and targeting health care access barriers. J Health Care Poor Underserved 22:562-575, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Syed ST, Gerber BS, Sharp LK: Traveling towards disease: Transportation barriers to health care access. J Community Health 38:976-993, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delgado-Guay MO Hui D Parsons HA, et al. : Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 41:986-994, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balboni MJ Sullivan A Amobi A, et al. : Why is spiritual care infrequent at the end of life? Spiritual care perceptions among patients, nurses, and physicians and the role of training. J Clin Oncol 31:461, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rushton L: What are the barriers to spiritual care in a hospital setting? Br J Nurs 23:370-374, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Farahani AS Rassouli M Salmani N, et al. : Evaluation of health-care providers' perception of spiritual care and the obstacles to its implementation. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 6:122-129, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ahmad F, Binti Muhammad M, Abdullah AA: Religion and spirituality in coping with advanced breast cancer: Perspectives from Malaysian muslim women. J Relig Health 50:36-45, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mabena N, Moodley P: Spiritual meanings of illness in patients with cervical cancer. South Afr J Psychol 42:301-311, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pargament KI Smith BW Koenig HG, et al. : Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig 37:710-724, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maree JE, Holtslander L, Maree JE: The experiences of women living with cervical cancer in Africa. A metasynthesis of qualitative studies. Cancer Nurs 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000812[epub ahead of print on March 24, 2020] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Mabena N, Moodley P: Spiritual meanings of illness in patients with cervical cancer. South Afr J Psychol 42:301-311, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nyblade L Stockton M Travasso S, et al. : A qualitative exploration of cervical and breast cancer stigma in Karnataka, India. BMC Womens Health 17:58, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Puchalski CM, Guenther M: Restoration and re-creation: Spirituality in the lives of healthcare professionals. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 6:254-258, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nemati S, Rassouli M, Baghestani AR: The spiritual challenges faced by family caregivers of patients with cancer: A qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract 31:110-117, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.King SD Fitchett G Murphy PE, et al. : Determining best methods to screen for religious/spiritual distress. Support Care Cancer 25:471-479, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lucas AM: Introduction to the discipline for pastoral care giving. J Health Care Chaplain 10:1-33, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shields M, Kestenbaum A, Dunn LB: Spiritual AIM and the work of the chaplain: A model for assessing spiritual needs and outcomes in relationship. Palliat Support Care 13:75, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Monod S Martin E Spencer B, et al. : Validation of the spiritual distress assessment tool in older hospitalized patients. BMC Geriatr 12:13, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fitchett G Hisey Pierson AL Hoffmeyer C, et al. : Development of the PC-7, a quantifiable assessment of spiritual concerns of patients receiving palliative care near the end of life. J Palliat Med 23:248-253, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hatamipour K Rassouli M Yaghmaie F, et al. : Spiritual needs of cancer patients: A qualitative study. Indian J Palliat Care 21:61, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ahmadi F, Hussin NAM, Mohammad MT: Religion, culture and meaning-making coping: A study among cancer patients in Malaysia. J Relig Health 58:1909-1924, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Delgado-Guay MO Parsons HA Hui D, et al. : Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 30:455-461, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.World Health Organization : WHO Report on Cancer: Setting Priorities, Investing Wisely and Providing Care for All. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330745 [Google Scholar]

- 84.Temel JS Greer JA Muzikansky A, et al. : Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 363:733-742, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Krakauer EL Kane K Kwete X, et al. : Augmented Package of Palliative Care for Women With Cervical Cancer: Responding to Refractory Suffering. JCO Glob Oncol 7:886-895, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.World Health Organization : Planning and Implementing Palliative Care Services: A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/250584 [Google Scholar]

- 87.International Association for Hospice and Palliative care. https://hospicecare.com/global-directory-of-education-programs/

- 88.World Health Organization : Why Is Palliative Care and Essential Function of Primary Health Care? Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2018. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/palliative.pdf?sfvrsn=ecab9b11_2 [Google Scholar]

- 89.World Health Organization : Declaration of Astana. Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2018. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 90.Devi BCR, Tang TS, Corbex M: Setting up home-based palliative care in countries with limited resources: A model from Sarawak, Malaysia. Ann Oncolog 19:2061-2066, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Herce ME Elmore SN Kalanga N, et al. : Assessing and responding to palliative care needs in rural sub-Saharan Africa: Results from a model intervention and situation analysis in Malawi. PLoS One 9:e110457, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Palazuelos D, Farmer PE, Mukherjee J: Community health and equity of outcomes: The partners in health experience. Lancet Glob Health 6:491-493, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shepperd S, Wee B, Straus Sharon E: Hospital at home: Home-based end of life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev:CD009231, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hudson P Remedios C Zordan R, et al. : Guidelines for the psychosocial and bereavement support of family caregivers of palliative care patients. J Palliat Med 15:696-702, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]