Abstract

Connecting basic data about bats and other potential hosts of SARS-CoV-2 with their ecological context is crucial to the understanding of the emergence and spread of the virus. However, when lockdowns in many countries started in March, 2020, the world's bat experts were locked out of their research laboratories, which in turn impeded access to large volumes of offline ecological and taxonomic data. Pandemic lockdowns have brought to attention the long-standing problem of so-called biological dark data: data that are published, but disconnected from digital knowledge resources and thus unavailable for high-throughput analysis. Knowledge of host-to-virus ecological interactions will be biased until this challenge is addressed. In this Viewpoint, we outline two viable solutions: first, in the short term, to interconnect published data about host organisms, viruses, and other pathogens; and second, to shift the publishing framework beyond unstructured text (the so-called PDF prison) to labelled networks of digital knowledge. As the indexing system for biodiversity data, biological taxonomy is foundational to both solutions. Building digitally connected knowledge graphs of host–pathogen interactions will establish the agility needed to quickly identify reservoir hosts of novel zoonoses, allow for more robust predictions of emergence, and thereby strengthen human and planetary health systems.

Introduction

An irony of COVID-19 potentially originating from a bat-borne coronavirus1 is that the global lockdown to quell the pandemic also locked up physical access to much needed knowledge about bats. Basic data about the diversity, ecology, and geography of bat populations, as well as of other potential mammal hosts,1, 2 were suddenly vital to understanding the emergence and spread of SARS-CoV-2. However, with the world's bat experts unable to access their research laboratories, any undigitised or offline data were also locked down. In a matter of days, worldwide lockdowns drastically reduced the accessibility of scientific knowledge. In this digitally interconnected age, why was basic knowledge about species and their ecological interactions not already digitised, online, and openly accessible to all? What must be done to improve global access to public health-related biodiversity knowledge?

Understanding why biodiversity science was unprepared—and how to resolve this issue before the next crisis—has been a hot topic, spawning multiple taskforces in the biodiversity research community since the pandemic began.3, 4, 5 Of key interest has been mending the chasm in knowledge transfer from physical biocollections (which contain the preserved specimens, tissues, and associated material used to describe biodiversity) to biomedical scientists in fields such as infectious diseases, epidemiology, and virology. Most published biodiversity knowledge is effectively locked in textual, unstructured articles, and is thus isolated from efforts to synthesise global ecological interactions. These data exist in publications, but are digitally disconnected—creating a knowledge frontier that is preventing scientists from digitally discovering and using them. With human activities such as land conversion hastening the emergence of zoonoses,6 building interconnected networks of digital knowledge is increasingly urgent.

Illuminating biodiversity dark data

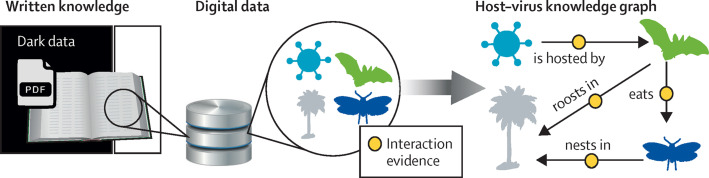

Physicists accept that dark matter exists, but they have difficulty measuring it. In the same way, biodiversity scientists are aware of large quantities of so-called dark data in publications, but have difficulty synthesising it, either because such data are old and rare (eg, in archival or grey literature), or new and locked (eg, behind paywalls, in digitally unreadable formats, or unlinked to other data). Traditionally, a particular research project might manually synthesise information from hundreds or thousands of articles in disparate formats over the course of years, yielding a comprehensive snapshot of written knowledge. Even today, gathering the widely scattered biodiversity data relevant to mammal host–virus interactions would take years, instead of the weeks needed to respond to a crisis like the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Remarkably, new articles continue to contribute to the dark data dilemma because the ubiquitous portable document format (PDF) requires substantial efforts to make ecological information, such as on host–virus interactions, extractable for reuse (hence the term PDF prison).7 To address global problems such as COVID-19, implementing new solutions, which build expansive digital knowledge, is imperative (figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

The evolution of biodiversity knowledge from analogue to digital

Extracting written knowledge from publications into databases is only the first step towards creating forms of digital, structured knowledge in which ecological interactions and evidence thereof are additionally annotated. Such knowledge graphs include levels of confidence in each annotation as derived from evidence sources, which enable high-throughput integrative modelling of complex ecological dynamics such as viral spillovers. Much written knowledge is undigitised and digitally disconnected, forming dark data from the perspective of synthetic knowledge graphs. PDF=portable document format.

For data to form digital knowledge, they must first be published in datasets that are open access and conform to the FAIR principles: findable on the web, digitally accessible, interoperable among different computing systems, and thus reusable for later analyses. Satisfying all these criteria opens the door to highly useful knowledge graphs,8, 9 in which digital open data are meaningfully linked together on massive scales, forming knowledge that is collectively greater than its sum. As Tim Berners-Lee presciently wrote, in 2006, “it is the unexpected re-use of information which is the value added by the web”.10 Illuminating the zoonotic origins of COVID-19 is exactly the kind of unexpected reuse of data that biodiversity science was ill-prepared to address at the start of the pandemic. Furthermore, building a comprehensive host–virus knowledge graph will enable rapidly improving artificial intelligence algorithms (eg, in the fields of natural language processing11 and knowledge reasoning12) to flexibly learn from the structure of digital knowledge.

Key messages.

-

•

Biological taxonomy is the hub of knowledge for host-to-pathogen interactions

-

•

Current publishing methods lock up digital knowledge, hindering synthetic analyses

-

•

Liberating digital forms of host–pathogen knowledge is needed to prevent future spillovers

Taxonomy as the key to host–virus knowledge

Linking viruses to animal hosts, hosts to environments, and hosts to other hosts (figure 2A ) is the raw material needed to build a host–virus knowledge graph. However, meaningfully connecting host species, viral species, and their ecological traits requires mastery of a fundamental but undersold discipline: biological taxonomy. For at least three centuries, mainstream science has used the names of species—most often the genus and species pair of Linnaean taxonomy—to index research findings. Virtually all observations about organismal behaviours and functions, habitats, genomics, and pathogens are linked to species names via sections of publications called taxonomic treatments, in which authors describe the boundaries of species (and other taxa) based on physical evidence. Because that evidence—especially from preserved specimens and derived data such as DNA sequences—has improved along with the science of taxonomy through time, multiple names might have been used to refer to similar sets of organisms. Thus, making sense of biodiversity data requires keeping track of how the meaning of taxonomic names has changed historically (eg, with synonyms and varying name usages).

Figure 2.

Connecting digital knowledge of host–virus interactions

(A) The sharing of viruses among humans and other mammals is remarkably common, yet the ecological circumstances under which spillover occurs are poorly understood. (B) Digitally liberating ecological knowledge from locked publications requires building taxonomic intelligence—ie, how and why species names have been used through time—and then using that taxonomic passkey to liberate and connect dark interaction data hidden in publications. Alternatively, data can be created connected if new articles are published using computer-readable (semantic) tags for ecological interactions such as “has host” or “pathogen of”. Both pathways will enable newly comprehensive knowledge graphs that connect host–virus interactions with underlying evidence. Adapted from Soisook et al13 by permission of Museum and Institute of Zoology, Polish Academy of Sciences, from the work of Emily S Damstra with permission, and from BioRender with permission.

Keeping track of how species names have been used by different authors over time is something of a taxonomic passkey to open (otherwise locked) host-to-virus interactions in publications. By linking species names, evidence, and taxonomic treatments through time, creating taxonomic intelligence services14 that can flexibly convert named species data across different taxonomies becomes possible. For example, severe acute respiratory syndrome-like coronaviruses observed in horseshoe bats identified as Rhinolophus sinicus, in 2013,15 need to be aligned with the 2019 reclassification of portions of this species as Rhinolophus thomasi and Rhinolophus rouxii.16 However, updating the taxonomy of named data when taxonomic concepts have been split is not yet possible, except manually on small scales. Existing taxonomic infrastructures such as the Catalogue of Life have not prioritised building large-scale solutions to this problem, primarily because taxonomic changes are often very rapid. Even in a relatively well known group such as mammals, the global number of recognised species has changed by approximately 40% in the past 25 years,17 over which time the number of described viruses has increased by a staggering 400%.18 Keeping track of mammal-to-virus interactions relative to that taxonomic flux has not been incentivised in proportion to its importance in understanding the emergence of zoonotic diseases. Therefore, efforts to prioritise the building of taxonomic intelligence services must be made, which will then enable the extraction and meaningful linkage of named host-to-virus interaction data on planetary scales.

Towards a host–virus knowledge graph

Thankfully, two decades of work in the digital knowledge arena8, 10, 14, 19, 20 have established the foundations for a two-pronged approach to building host–virus knowledge (figure 2B). As a first step, dark data need to be liberated from existing publications. These efforts are being led by Plazi, a pioneering platform for literature digitisation, extraction, and linking, to create new flows of digital data from printed books, archives, and otherwise locked publications.19 For example, services offered by Plazi have, in the past year, indexed taxonomic names (Synospecies tool) and images (Ocellus tool) from taxonomic treatments spanning from Linnaeus' initial publication of Systema Naturae (1758) to the Handbook of the Mammals of the World series (2009–19),21 making them freely available on the Biodiversity Literature Repository.22 Once digitally indexed, taxonomic data can be annotated and connected to biocollection-based evidence to formally align taxonomic names with their biological meanings. This liberated taxonomic knowledge allows for more robust literature searches and subsequent name translation of host–virus interaction data. Such efforts have already discovered reliable data on 1146 host–virus interactions from selected publications.23 The second step is for new articles to be published without creating more dark data. Exemplary in this area are efforts led by Pensoft—the publisher of biodiversity journals such as ZooKeys—to publish using computer-readable semantic annotations during the normal publishing process,24 allowing immediate indexing afterwards.25 For example, Pensoft responded to COVID-19 by beginning to index text such as “has host” and “pathogen of” to assist with mining biotic interactions from article texts and tables, which has captured over 2000 biotic interactions now annotated as article metadata.26 Such digital enhancements greatly streamline the process of data extraction because new articles already contain digital text, linking terms, and thus a native form of digital knowledge.

Building a singular host–virus knowledge graph requires a central hub wherein to find relevant data, resolve disparate taxonomies, and connect the resulting insights. Promising progress by the Global Biotic Interactions database GloBI—an open-access ecological network across all taxonomic groups20—has resulted in new pipelines for ecological data to flow from sources of both previously existing19, 21 and newly published literature.26 From April to October, 2020, only, these pipelines resulted in more than 53 000 host–virus data points being added to the Global Biotic Interactions database.27 These associations involve 19% more valid species of mammals than were identified in a 2017 host–virus synthesis (897 species vs 754 species).28 Such a drastic initial result illustrates the potential for broad-scale data linking to yield new insights. Yet, these are small steps compared with what could eventually comprise a comprehensive and taxonomically nimble graph of not only host–virus, but host–pathogen and broader ecological knowledge. What interconnected relationships might be illuminated when such knowledge is freely available to the world's scientists and public health specialists?

Beyond the PDF: knowledge that is created connected

We have outlined ways to interconnect—and thus liberate—previously dark host–pathogen interactions from publications. However, doing so is expensive and, therefore, infeasible at scale if publishers continue to publish under the current framework. Therefore, we recommend three immediate policy changes. First, major journals should switch to publishing formats that are not only open access and conform to FAIR principles, but also semantically tagged with terms relevant to broad-scale ecological interactions (especially host–pathogen and host–host relationships). Second, academic institutions should incentivise (eg, via tenure evaluations or by paying open-access fees) publishing in such created-connected journals. Finally, investments in data generation should be balanced with infrastructure enhancements for data reuse, incentivising the construction of increasingly complete biodiversity knowledge graphs. Taxonomists, ecologists, data scientists, and policy makers all hold essential roles in this paradigm shift towards digital knowledge.

The value added by digitally connected knowledge is tremendous, both for its potential to build non-linear insights and to expand the capacity of biodiversity researchers worldwide, especially in low-income and middle-income countries.29 Limitations to accessing biodiversity information in these countries are diverse and include gaps in geographical knowledge, poor data sharing among and between scientists and policy makers, inaccessible information formats, and scarce financial resources. Efforts are therefore needed not only to increase biodiversity monitoring, but also to support the capacity of local scientific and citizen communities to mobilise the resulting data into digital knowledge infrastructures. Pandemics show that human societies are inextricably linked, regardless of wealth; consequently, building a biodiversity knowledge base will benefit all.

Continuing to waste resources by rediscovering biodiversity knowledge is counterproductive. Unprecedented reliability of knowledge about biological interactions is now required to address multiple socioecological challenges, from COVID-19 to biodiversity loss and uncontrolled climate change, each of which exists on scales too massive and too detailed for any single individual to observe alone. The COVID-19 pandemic shows that siloed science does not serve society as efficiently as does open, interconnected science. Multiple novel solutions, including vaccines and treatments, are beginning to free the world from this pandemic. However, the solution for our limited access to ecological knowledge is already here. Much of the technology needed to liberate and connect biodiversity data across all biota is already available—what is most lacking is the collective will to do so.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Included datasets were identified between April 14 and Oct 6, 2020, through CETAF-DiSSCo Taskforce activities and subsequently indexed by Global Biotic Interactions. A full list of sources indexed through the Global Biotic Interactions database is provided with the archived data at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4068958.

Data sharing

All data liberated as a result of these efforts are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4068958.

Declaration of interests

LP is employed by Pensoft Publishers. MG and DA are affiliated with Plazi. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

NSU is supported by the Biodiversity Knowledge Integration Center at Arizona State University and the US National Institutes of Health (grant number 1R01AI151144-01A1). DMR is supported by the US National Science Foundation (RAPID 2032774) and the US National Institutes of Health (grant number 1R01AI151144-01A1). NMF and BS are supported by the Arizona State University President's Special Initiative Funds. QJG is supported by the SYNTHESYS+ Research and Innovation action grant Horizon 2020-EU.1.4.1.2823827. DA is supported by the Arcadia Fund. DP is supported by the US National Science Foundation Advancing Digitization of Biodiversity Collections Program grant number DBI-1547229. MPMV is supported by the Special Research Fund of Hasselt University (grant number BOF20TT06). JHP is supported by the US National Science Foundation award Collaborative Research: Digitization TCN: Digitizing collections to trace parasite-host associations and predict the spread of vector-borne disease (award numbers DBI:1901932 and DBI:1901926). NSU, DMR, BS, AS, JHP, and DA are supported by the US National Institutes of Health (1R21AI164268-01). We thank Ana Casino, Dimitris Koureas, and Wouter Addink for organising the Consortium of European Taxonomic Facilities-Distributed System of Scientific Collections COVID-19 Taskforce that resulted in this Viewpoint, Esther Florsheim for valuable conversations, and BioRender, Pipat Soisook, and Emily Damstra for access to images or illustrations.

Contributors

NSU, JHP, DP, QJG, NBS, and DA outlined this Viewpoint. JHP, MG, DA, LP, and NSU worked on the methods and created software for data liberation. JHP, DA, and LP curated the resulting data. NSU and JHP validated the resulting data to check for redundancy. NSU and DA wrote the initial draft. NSU created the figures with help from CB-S. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

References

- 1.Boni MF, Lemey P, Jiang X. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Microbiol. 2020;5:1408–1417. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0771-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xia X. Extreme genomic CpG deficiency in SARS-CoV-2 and evasion of host antiviral defense. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37:2699–2705. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CETAF-DiSSCo COVID-19 Taskforce Communities taking action. https://cetaf.org/covid19-taf-communities-taking-action

- 4.ViralMuse Task Force. iDigBio Wiki. https://www.idigbio.org/wiki/index.php/ViralMuse_Task_Force No authors listed.

- 5.Research Data Alliance RDA COVID-19. https://www.rd-alliance.org/groups/rda-covid19

- 6.Faust CL, McCallum HI, Bloomfield LSP. Pathogen spillover during land conversion. Ecol Lett. 2018;21:471–483. doi: 10.1111/ele.12904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agosti D, Catapano T, Sautter G, Egloff W. The Plazi workflow: the PDF prison break for biodiversity data. Biodivers Inf Sci Stand. 2019;3 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penev L, Dimitrova M, Senderov V. OpenBiodiv: a knowledge graph for literature-extracted linked open data in biodiversity science. Publ MDPI. 2019;7:38. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page R. Towards a biodiversity knowledge graph. Res Ideas Outcomes. 2016;2 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berners-Lee T. Linked data. July 27, 2006. https://www.w3.org/DesignIssues/LinkedData.html

- 11.Burgdorf A, Pomp A, Meisen T. Towards NLP-supported semantic data management. May 14, 2020. https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.06916

- 12.Bellomarini L, Sallinger E, Vahdati S. In: Knowledge graphs and big data processing. Janev V, Graux D, Jabeen H, Sallinger E, editors. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2020. Chapter 6 reasoning in knowledge graphs: an embeddings spotlight; pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soisook P, Karapan S, Srikrachang M. Hill forest dweller: a new cryptic species of Rhinolophus in the ‘pusillus Group’ (Chiroptera: Rhinolophidae) from Thailand and Lao PDR. Acta Chiropt. 2016;18:117–139. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bisby FA. The quiet revolution: biodiversity informatics and the internet. Science. 2000;289:2309–2312. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ge X-Y, Li J-L, Yang X-L. Isolation and characterization of a bat SARS-like coronavirus that uses the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2013;503:535–538. doi: 10.1038/nature12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgin CJ. Rhinolophus sinicus K Andersen 1905. Oct 31, 2019. https://zenodo.org/record/3808964

- 17.Burgin CJ, Colella JP, Kahn PL, Upham NS. How many species of mammals are there? J Mammal. 2018;99:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses ICTV historical taxonomy releases. https://talk.ictvonline.org/taxonomy/p/taxonomy_releases

- 19.Agosti D, Egloff W. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:53. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poelen JH, Simons JD, Mungall CJ. Global biotic interactions: an open infrastructure to share and analyze species-interaction datasets. Ecol Inform. 2014;24:148–159. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agosti D. Time for an interim review of Plazi's Covid-19 related activities. July 17, 2020. http://plazi.org/news/beitrag/time-for-an-interim-review-of-plazis-covid-19-related-activities/3e26b3bc95a4b39f0a2a9d7fccee8b19/

- 22.Agosti D, Catapano T, Sautter G. Biodiversity Literature Repository (BLR), a repository for FAIR data and publications. Biodivers Inf Sci Stand. 2019;3 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenodo Coronavirus-host community. https://zenodo.org/communities/coviho/?page=1&size=20

- 24.Penev L, Catapano T, Agosti D, Georgiev T, Sautter G, Stoev P. Implementation of TaxPub, an NLM DTD extension for domain-specific markup in taxonomy, from the experience of a biodiversity publisher. Journal Article Tag Suite Conference Proceedings 2012. National Center for Biotechnology Information. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK100351/

- 25.Senderov V, Simov K, Franz N. OpenBiodiv-O: ontology of the OpenBiodiv knowledge management system. J Biomed Semantics. 2018;9:5. doi: 10.1186/s13326-017-0174-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitrova M, Poelen J, Zhelezov G, Georgiev T, Agosti D, Penev L. Semantic publishing enables text mining of biotic interactions. Biodivers Inf Sci Stand. 2020;4 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poelen J, Upham N, Agosti D. CETAF-DiSSCo/COVID19-TAF biodiversity-related knowledge hub working group: indexed biotic interactions and review summary. Zenodo. Oct 6, 2020. [DOI]

- 28.Olival KJ, Hosseini PR, Zambrana-Torrelio C, Ross N, Bogich TL, Daszak P. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature. 2017;546:646–650. doi: 10.1038/nature22975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagaraj A, Shears E, de Vaan M. Improving data access democratizes and diversifies science. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:23490–23498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2001682117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data liberated as a result of these efforts are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4068958.