Abstract

Objective

NFκB is the key modulator in inflammatory disorders. However, the key regulators that activate, fine-tune or shut off NFκB activity in inflammatory conditions are poorly understood. In this study, we aim to investigate the roles that NFκB-specific long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play in regulating inflammatory networks.

Design

Using the first genetic-screen to identify NFκB-specific lncRNAs, we performed RNA-seq from the p65-/- and Ikkβ -/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts and report the identification of an evolutionary conserved lncRNA designated mNAIL (mice) or hNAIL (human). hNAIL is upregulated in human inflammatory disorders, including UC. We generated mNAILΔNFκB mice, wherein deletion of two NFκB sites in the proximal promoter of mNAIL abolishes its induction, to study its function in colitis.

Results

NAIL regulates inflammation via sequestering and inactivating Wip1, a known negative regulator of proinflammatory p38 kinase and NFκB subunit p65. Wip1 inactivation leads to coordinated activation of p38 and covalent modifications of NFκB, essential for its genome-wide occupancy on specific targets. NAIL enables an orchestrated response for p38 and NFκB coactivation that leads to differentiation of precursor cells into immature myeloid cells in bone marrow, recruitment of macrophages to inflamed area and expression of inflammatory genes in colitis.

Conclusion

NAIL directly regulates initiation and progression of colitis and its expression is highly correlated with NFκB activity which makes it a perfect candidate to serve as a biomarker and a therapeutic target for IBD and other inflammation-associated diseases.

Keywords: chronic ulcerative colitis, inflammation, inflammatory bowel disease

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

NFκB is highly activated in IBD patients and associated with disease severity.

NFκB and p38 have been shown to be required for the expression of proinflammatory genes for full-blown inflammation.

NFκB activity can be shut off by dephosphorylation of active p65 by the Wip1 phosphatase leading to loss of its chromatin remodelling potential and consequently reduced transcription of NFκB targets.

A number of signalling regulators, including enzymes, adaptor proteins and non-coding RNAs such as miRNAs which regulate NFκB and p38 have been identified and characterised.

Several lncRNAs have been proposed to be induced on TNFα stimulation and dysregulated in human inflammatory diseases.

lncRNAs can interact with kinases and regulate their activity.

What are the new findings?

NAIL is the first lncRNA to be identified by a genetic screen, and its expression is absolutely NFκB dependent. This autoregulation is unique and not documented before.

NAIL forms a positive feedback loop with NFκB signalling, and its expression is enhanced in colitis.

NAIL regulates the development of colitis by regulating the expression of inflammatory cytokines and recruitment of effector cells to the site of inflammation.

NAIL simultaneously activates p38, a kinase and p65 a transcription factor. Such direct coordinated activation of two pathways has not been documented for any other lncRNA.

NAIL deactivates a phosphatase (Wip1) essential to activate NFκB and p38 signalling for full-blown inflammation in colitis.

Significance of this study.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The critical role of NAIL in Wip1-NFκB/p38 axis in the development of colitis serves as an attractive target for the development of future therapies against inflammatory diseases such as UC or human cancers such as colitis-associated colorectal cancer

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory diseases such as IBD stem from dysregulated immune responses, aberrant cytokine/chemokine secretion and alterations in intestinal barrier and microbiota.1 In IBD, intestinal microbiota releases enterotoxins that increase the permeability of intestinal mucosa, resulting in a state of intestinal inflammation caused by invasion of harmful bacteria and damaged intestinal epithelial cells.2 In UC patients, NFκB is activated in epithelial cells and mucosal macrophages that enhances the secretion of a broad panel of NFκB-regulated cytokines including TNFα, IL-1 and IL-6.3 Due to recurrent cycles of evoked inflammatory activation, IBD patients have been shown to be more susceptible to cytokine storm syndrome4 and cancer development. This is due to the hyperactive NFκB-dependent cytokine secretion which induces hyper proliferation of immune cells and excessive tissue damage, resulting in an accumulation of new cancer mutations.5 6

There are many regulators of NFκB, including kinases, ubiquitin ligases and miRNAs. Some of these have been identified as potential therapeutic targets.7 However, only ~1%–2% of the human genome encodes proteins, while 75%–90% is transcribed into non-coding RNAs;8 it is plausible that the key regulators that activate, fine-tune or shut off NFκB activity have yet to be discovered. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) constitute the majority of this rampant transcription of the mammalian genome.8 9

To identify lncRNAs that are directly and specifically regulated by NFκB, we performed RNA-seq from wild type (WT), p65 -/- and Ikkβ -/- mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) treated with TNFα for different time points (figure 1A, B). This screen revealed a novel, evolutionarily conserved lncRNA, Gm16685 in mouse and its human homolog (loc105375914), both of which are prominently and specifically activated by the p65 subunit of NFκB. We named this unannotated lncRNA as NFκB Associated Immunoregulatory Long non-coding RNA, NAIL. hNAIL is upregulated in many human inflammatory disorders including UC. To model NAIL’s function, we deleted the two conserved NFκB sites in the proximal mouse NAIL (mNAIL) promoter and generated a mouse model (mNAILΔNFκB ) in which NAIL gene is unresponsive to NFκB-dependent activation. mNAILΔNFκB mice displayed decreased expression of NFκB targets and consequently had reduced colitis. On inflammatory stimulation, NAIL is expressed, and sequester Wip1 phosphatase and prevent Wip1 from dephosphorylating, and deactivating active p65 and other Wip1 targets such as p38 necessary for full-blown inflammatory gene expression. These results provide the first evidence that lncRNAs can directly modulate phosphatase accessibility to its substrates which has important consequences in inflammation.

Figure 1.

Identification of lncRNAs regulated by NFκB signalling pathway. (A) NFκB signalling pathway and screening strategy used to identify NFκB-regulated lncRNAs. Crosses represent loss of the corresponding proteins (Ikkβ, Ikkγ, p65) using KO MEFs. (B) Heatmap of logCPM values of differentially expressed lncRNAs in WT, p65 -/- and Ikkβ -/- in immortalised MEFs exposed to TNFα for the indicated time points and analysed by paired-end RNA-sequencing. Gm16685 is shown with red arrow. (C) Schematic view of genetic loci of Gm16685 lncRNA (blue). Gm16685 is expressed from antisense direction to IL7 gene (red). NFκB binding motifs in the promoter region of Gm16685 shown as yellow highlighted sequences. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of Gm16685 transcript levels in immortalised WT MEFs exposed to TNFα for different time points as indicated. (E) RT-qPCR analysis of Gm16685 in WT (n=5), p65 -/- (n=8) and Ikkβ -/- (n=3) independent primary MEFs treated with TNFα for indicated time courses. P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (***p<0.001). (F) Gene expression profile of 24 inflamed and patient match non-inflamed samples. Differentially expressed genes are shown in heatmap. LOC105375914 is shown with red arrow. (G) Box plot shows upregulation of hNAIL (LOC105375914) expression in inflamed colon tissue of UC patients. KO, knock out; MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; WT, wild type.

Results

Identification and characterisation of Gm16685 (mNAIL); a novel lncRNA specifically regulated by NFκB signaling

Besides activating the NFκB pathway, TNFα receptor engagement also leads to activation of JNK, p38 and apoptotic pathways (figure 1A). Since NFκB activation is specifically impaired in p65 -/- and Ikkβ -/- MEFs (online supplemental figure 1A, B) downstream of TNF signalling, we employed these cells to identify NFκB-driven lncRNAs. Differentially expressed lncRNAs between WT, p65 -/- and Ikkβ -/- MEFs on TNFα stimulation were identified (figure 1B). To identify lncRNAs that were directly and specifically regulated by NFκB signalling, we selected the lncRNAs that were TNFα inducible in a time-dependent manner in WT but not in p65 -/- and Ikkβ -/- MEFs. We selected Gm16685, a novel lncRNA expressed in the antisense direction of interleukin-7 (IL7), for further functional and mechanistic studies (figure 1C). Gm16685 expression was dramatically upregulated in WT MEFs stimulated with TNFα (figure 1D). However, compared with WT MEFs, Gm16685 expression in p65 -/-, Ikkβ -/- and Ikkγ -/- immortalised MEFs was significantly dampened on TNFα stimulation (online supplemental figure 1C, D). Primary MEFs derived from WT, p65 -/- and Ikkβ -/- mice also showed that activation of Gm16685 occurred specifically in an Ikkβ-dependent and p65-dependent manner (figure 1E). Gm16685 expression was also induced by stimulation with TLR4 ligand, lipopolysaccharides (LPS) in WT immortalised MEFs (online supplemental figure 1E). Importantly, the antisense gene IL7 remained relatively unchanged on stimulation (online supplemental figure 1F), suggesting the specificity of induction of Gm16685 by p65 via Ikkβ. Taken together, these results suggest that Gm16685 expression is specifically activated by NFκB signalling, downstream of major inflammatory stimuli such as TNFα and LPS.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp001.pdf (149.6KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp002.pdf (387.3KB, pdf)

loc105375914 (hNAIL), an evolutionarily conserved human homolog of Gm16685 (mNAIL) is upregulated in UC

Determining which lncRNAs are evolutionarily conserved highlights the functional importance of such transcripts in fundamental biological processes.10 To identify human orthologue of Gm16685 (mNAIL), we converted genome coordinates of Gm16685 (chr3:7612705–7690001) in mouse (mm10) to human (hg38) genome coordinates by using UCSC liftOver with default parameters. Human lncRNA, loc105375914 (hNAIL) (chr8:78804578–78937681) overlapped with the converted region (chr8:78804472–78902467), hence, loc105375914 was considered as candidate orthologue of mouse Gm16685. Although lncRNAs have poor sequence conservation, their promoter regions are generally more conserved.11 Hence, we performed multiple sequence alignment using promoter sequence of the mouse Gm16685 and sequences of 31 other species at the same region with reference to UCSC comparative genomic track (online supplemental figure 2A). Promoter motifs enrichment analysis identified NFκB as the most significantly enriched motif across all orthologues (online supplemental figure 2B). Most importantly, the RNA binding protein (RBP) binding motifs predicted using RBPmap server (http://rbpmap.technion.ac.il/) showed that >80% of RBPs predicted to bind Gm16685 are also predicted to bind the human loc105375914 lncRNA (online supplemental figure 2C) suggesting that hNAIL and mNAIL are most likely functionally conserved.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp003.pdf (643.7KB, pdf)

Analyses of publicly available p65 (RelA) ChIP-seq data12 13 from mouse dendritic cells, macrophages stimulated with LPS and human adipocytes and fibroblasts stimulated with TNFα demonstrated that p65 binds to the promoter regions of Gm16685 and loc105375914 in a stimulus-dependent manner (online supplemental figure 2D, E). Additionally, RNA Polymerase 2 (Pol2) ChIP-seq data14 15 from these human adipocytes and fibroblasts revealed that loc105375914 expression is driven by RNA Pol2 in conjunction with NFκB (online supplemental figure 2E). Two p65 (RelA) binding motifs located upstream of Gm16685 are highly conserved across species, suggesting that these motifs might be functionally important for regulation and subsequent transcription of Gm16685 across species. Furthermore, NAIL does not have coding potential as shown by computational analyses (online supplemental figure 2F) and 3’ Flag tagging strategy (online supplemental figure 2G).

Hyperactivation of NFκB is a functional determinant in the development of inflammatory diseases such as UC that causes inflammation in the colonic mucosa.16 Since loc105375914 is transcriptionally regulated by NFκB, we analysed transcriptomes of 24 inflamed and matched non-inflamed sections from human UC patients. In inflamed colons, we observed dramatic upregulation of NFκB target genes including TNFα and IL1β (figure 1F) which are known to be key regulators of intestinal inflammation.17 As compared with non-inflamed controls, loc105375914 expression is significantly upregulated in the inflamed colons (figure 1G), suggesting that loc105375914 expression highly correlates with NFκB activity and may serve as a biomarker for IBDs. Collectively, these results indicate that loc105375914 is a conserved human homolog of Gm16685, and both their expressions are specifically driven by NFκB signalling in response to inflammatory and microbial triggers across species and cell types. Hereafter, we will refer to Gm16685 as mNAIL and loc105375914 as hNAIL (NFκB Associated Immunoregulatory Long non-coding RNA).

mNAILΔNFκB mice display loss of mNAIL activation by NFκB and dampened inflammation

We generated mNAILΔNFκB mice wherein two conserved NFκB binding motifs upstream of mNAIL were removed using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 genome editing (figure 2A). mNAILΔNFκB mice were born alive in normal Mendelian ratios and had no overt phenotypes (figure 2B). Deletion of the NFκB motifs was confirmed by genotyping PCR (figure 2C) and Sanger sequencing (figure 2D). Three independent mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB primary MEF clones showed that mNAIL expression was abolished in the mNAILΔNFκB clones, whereas the expression level of IL7 gene was unaffected on TNFα treatment (figure 2E, F). We also observed decreased expression of NFκB targets TNFα and IL1β levels on TNFα treatment in mNAILΔNFκB MEFs compared with mNAILWT MEFs (figure 2G, H). Depletion of mNAIL by two independent siRNAs showed reduced NFκB target gene expression (figure 2I, J) and significant reduction in phosphorylation of p65 and p38 (figure 2K). To exclude the possibility that the observed phenotypes might stem from genome editing and its off target effects on IL7 or it neighbouring genes, we first analysed the expression of IL7 across different tissues in mice using NCBI fragments per kilobase of exon per million reads (FPKM) data. Since IL7 is highly expressed in thymus, spleen and colon tissues (online supplemental figure 3A), we analysed its expression in thymus between mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB groups and observed no significant difference in RNA and protein levels (online supplemental figure 3B, C). Although we did not observe any disruption of IL7 expression (RNA and protein level), we knocked-down IL7 gene using siRNA to investigate the impact of IL7 on NFκB signalling. Depletion of IL7 did not affect NFκB activation as judged by expression of TNFα (online supplemental figure 3D–F). Taken together, these results suggest that editing the two conserved NFκB sites in the NAIL promoter specifically dampens inducibility of NAIL in response to inflammatory stimuli and that NAIL in turn regulates NFκB targets genes in vivo.

Figure 2.

mNAILΔNFκB mice display decreased activation of NFκB and inflammation. (A) Schematic view of mNAIL lncRNA promoter targeting with CRISPR-Cas9 editing. NFκB binding motifs are shown in yellow in the promoter region of mNAIL. (B) mNAIL mice were generated using standard methods (refer to ‘Materials and methods’ section). mNAIL mice were born in normal Mendelian ratio (table below) and unchallenged mice appear normal. (C) Genotyping PCR results of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice. PCR products from mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB alleles are shown. (D) Sanger sequencing results of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB cells. (E–H) mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB MEFs (n=3) were treated with TNFα for the indicated time points. Expression analysis was performed by RT-qPCR for (E) mNAIL, (F) IL7, (G) TNFα and (H) IL1β genes. (I–K) WT MEFs were transfected with si-Control, si-NAIL #1 and si-NAIL #2 siRNAs. After 48 hours post-transfection, cells were treated with or without TNFα and harvested for gene expression analysis. Graphs show the gene expression analysis of (I) mNAIL and (J) TNFα by RT-qPCR. Actin was used as a control. Error bars indicate mean±SD of three independent experiments. P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; n.s., not significant). (K) Cells lysate were analysed with western blot for the indicated proteins. MEFs, mouse embryonic fibroblasts; WT, wild type.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp004.pdf (311.4KB, pdf)

mNAILΔNFκB mice display reduced colitis and colon inflammation

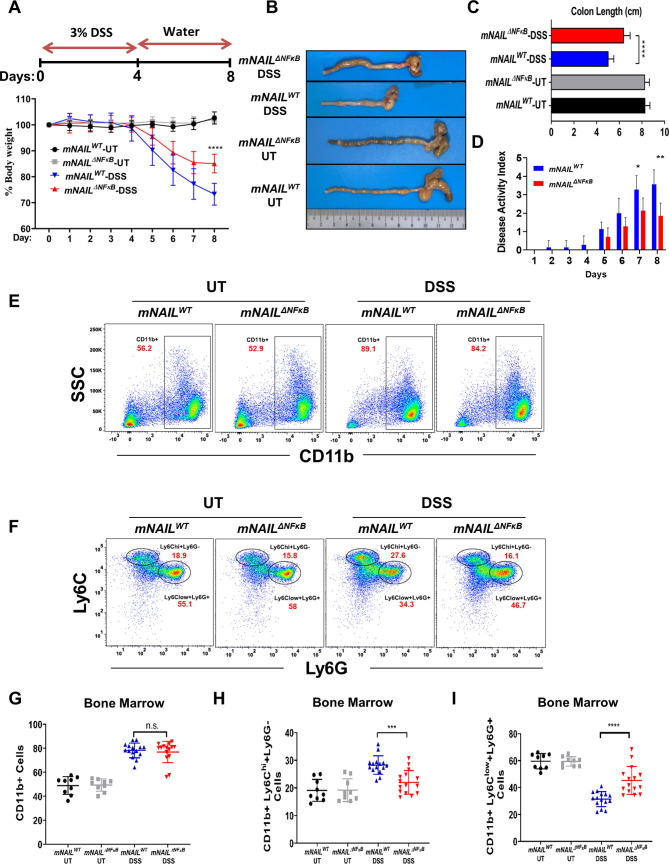

mNAILΔNFκB mice display reduced colitis and colon inflammation mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice were given 3% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) to induce acute colitis (figure 3A). Initial body weights of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice were similar, however, on DSS treatment, mNAILΔNFκB mice displayed less severe body weight loss when compared with mNAILWT counterparts (figure 3A). On DSS treatment, colon shortening was significantly less pronounced in mNAILΔNFκB mice and the disease activity index (DAI) was lower when compared with mNAILWT counterparts (figure 3B–D). These results were suggestive of reduced inflammation in mNAILΔNFκB mice.

Figure 3.

mNAILΔNFκB mice are resistant to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis. (A) Scheme of DSS-induced colitis model is shown on the top panel. mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice were treated as shown in top panel. Body weight measurements from mice monitored for 8 days (bottom panel). (B and C) Colon length of DSS-treated mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice measured at day 8. (D) Disease activity index was recorded daily. (E) Bone marrow cells were isolated from the DSS-treated mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice at day 8 and were stained for CD11b (PE), Ly6c (BV711) and Ly6g (FITC) cell surface markers. Cells were analysed by FACS and gated as CD11b+cells. Representative FACS data were shown for mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with or without DSS. (F) CD11b+cells were further gated for Ly6c and Ly6g markers. (G–I) Quantification of CD11b+, CD11b+Ly6Chi+Ly6G−, CD11b+Ly6Clow+Ly6G+cells gated in (E) and (F). Error bars indicate mean±SD of three independent experiments (UT: n=9, DSS: n=15). P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; n.s., not significant). DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; SSC, side scatter; side scatter; UT, untreated; WT, wild type.

DSS treatment has been shown to alter the myeloid precursor population in the bone marrow which directly correlates with the degree of inflammation in the colon.18 19 Especially, monocytes derived from the CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G− immature myeloid cells have been shown to enter tissues under inflammatory conditions and express high levels of proinflammatory cytokines in colitis.20–22 Given that myeloid cells are the predominant cells that infiltrate the inflamed tissues and the precursors are made in bone marrow,23 we analysed the myeloid populations in the bone marrow of mNAILΔNFκB mice. As expected, both mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice showed increased CD11b+population, on DSS treatment (figure 3E–G). Next, we analysed CD11b positive subpopulations CD11b+Ly6chi+Ly6g− and CD11b+Ly6cLow+Ly6g+ in bone marrow (figure 3F). DSS induced increase in Ly6Chi activator cell population was significantly more pronounced in mNAILWT mice (figure 3H). Conversely, compared with mNAILWT mice, elevated levels of Ly6clowLy6g+cells were seen in mNAILΔNFκB mice (figure 3I). To further investigate if NAIL has any role on the stem cell population in the bone marrow, we analysed the progenitor cells in the bone marrows of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with or without DSS24 (online supplemental figure 4A). Cells were initially gated as LIN- cells and based on the c-KIT and Sca-1 expression, the long-term and short-term hemateopoietic stem cell populations (KL, KSL and K-low_S-low) were selected. KL cells were further gated based on their CD16/32 and CD34 expression to identify megakaryocyte–erythrocyte, common myeloid progenitor and granulocyte-macrophage progenitors. To identify the common lymphoid progenitors population, we further gated K-low_S-low cells based on their IL7ra expression. Representative FACS data and quantification of all samples (online supplemental figure 4A–E) are shown for mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice. No difference was observed in the stem cells and precursor cells population between mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice suggesting that NAIL does not alter the stem cell and progenitor populations. Instead, our data suggest that mNAIL is a key determinant for the differentiation of precursor cells into CD11b+Ly6 c or Ly6g sub-types during inflammation.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp005.pdf (470KB, pdf)

mNAIL expression is functionally regulated in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM)

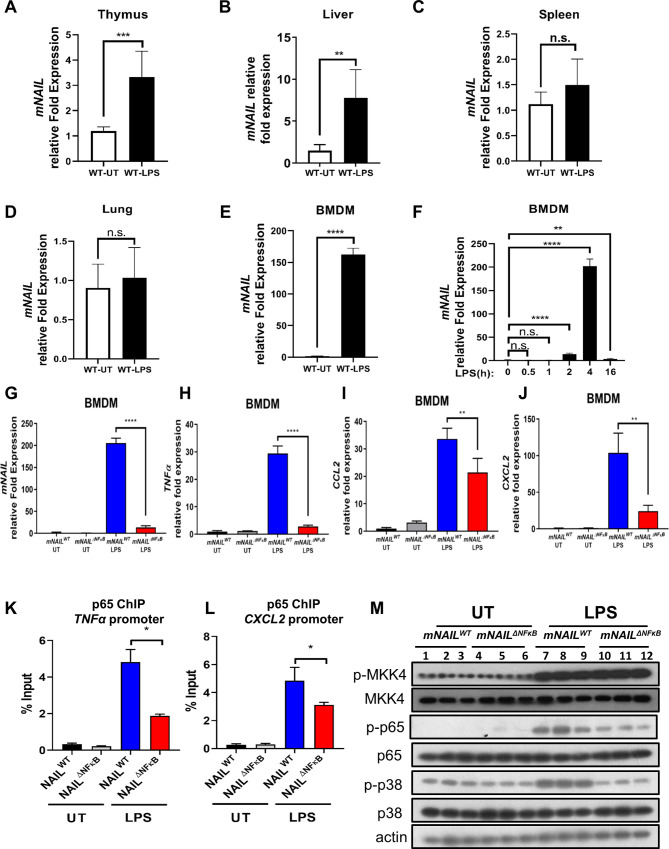

To identify the major site of mNAIL expression in vivo, we dissected the response of mNAIL in different cell types and tissues including thymus, liver, spleen, lung and BMDM using the systemic LPS-induced endotoxemia model (figure 4A–E). We observed mild induction of mNAIL in thymus and liver (figure 4A, B) but not in spleen and lung tissues (figure 4C, D). Strong induction of mNAIL in BMDMs was observed (figure 4E, F). We observed dampened induction of NFκB targets TNFα, CCL2 and CXCL2 on LPS challenge in mNAILΔNFκB BMDM (figure 4G–J). ChIP-qPCR results showed that the absence of mNAIL resulted in dramatic reduction of p65 occupancy at the promoters of these well-known NFκB target genes (figure 4K, L) suggesting that loss of NAIL impacts DNA binding and hence transcription by NFκB. We observed significant reduction in phospho-p65 and phospho-p38 levels in the absence of mNAIL in the BMDMs (figure 4M). We did not observe any change for an irrelevant protein phospho-MKK4 suggesting the specificity of NAIL acting on the phosphorylation of p65 and p38 (figure 4M). Crucially, myeloid lineage specific knock outs (KO) of p65 and p38 display reduced inflammatory responses and body weight differences in DSS model, highly resembling the observations in mNAILΔNFκB mice.23 25 26 To determine the molecular basis of this function of NAIL, we performed RNA-seq using colon tissues of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice with or without DSS treatment (figure 5A). Only a few genes were differentially expressed in the untreated (UT) group, reiterating that the deletion of two NFκB sites in the proximal promoter of mNAIL does not cause any global alterations in the transcriptome due to genome editing artefacts (online supplemental figure 5). However, DSS treatment caused vast changes in gene expression, with a majority of genes down-regulated in mNAILΔNFκB mice (figure 5A). Gene ontology analysis revealed that the majority of differentially expressed and downregulated genes in mNAILΔNFκB colons belong to inflammatory pathways regulated by NFκB (online supplemental figure 5B). To validate the RNA-seq results, we performed gene expression analysis of NFκB target genes and observed reduced expression of TNFα, IL1β and CCL2 genes in colon tissues of mNAILΔNFκB mice as compared with mNAILWT group (figure 5B–E). Similar to gene expression results, TNFα and IL1β protein levels were reduced in the colon tissues (figure 5F, G). We also observed reduced level of phospho-p65 and phospho-p38 in colons of DSS-treated mNAILΔNFκB as compared with mNAILWT group (figure 5H).

Figure 4.

mNAIL is expressed mainly in myeloid cells and its expression amplifies activation of NFκB and inflammation. (A–E) LPS (5 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally into C57BL/6N WT mice (n=6). (A) Thymus, (B) liver, (C) spleen and (D) lung tissues were collected after 4 hours and expression analysis was performed by RT-qPCR for mNAIL gene. (E, F) Bone marrow cells isolated from WT mice (n=6) and differentiated into bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) for 7 days. BMDM cells were treated with or without LPS (200 ng/mL) for 4 hours. (E) Graph shows the mNAIL expression analysis by qPCR. (F) Time kinetics of mNAIL expression is shown in LPS-stimulated BMDM cells. Data were normalised to actin. (G–J) Bone marrow cells isolated from mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice (n=6) and differentiated into BMDM for 7 days. BMDM cells were treated with or without LPS (200 ng/mL) for 4 hours. Graph shows the gene expression analysis of (G) mNAIL, (H) TNFα, (I) CCL2 and (J) CXCL2 by qPCR. Data were normalised to actin. (K–L) mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB BMDM cells were treated with or without LPS, and ChIP analysis was performed for p65 (n=3). Graph shows the ChIP-qPCR analysis of p65 occupancy on the (K) TNFα and (L) CXCL2 promoters. Error bars indicate mean±SD of three biological replicates. P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; n.s., not significant). (M) Western blot shows the total and phosphorylated p65, p38 and MKK4 in BMDM cells treated with or without LPS. Each replicate is labelled as #1, #2 and #3. UT, untreated; WT, wild type.

Figure 5.

mNAIL regulates expression of inflammatory genes in colitis. (A) Heat map shows the genes that are differentially expressed between mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with DSS. Genes were first filtered for differential genes on DSS treatment between mNAILWT untreated (UT) and DSS to identify DSS-dependent genes. Next, this gene list was used to identify the differentially expressed genes between mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with DSS. Differentially expressed genes were identified based on the criteria of 2 log2-fold difference with false discovery rate<0.05. (B–E) Expression analysis was performed by RT-qPCR for (B) mNAIL, (C) TNFα (D) IL1β and (E) CCL2 genes in the colon tissues of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with or without DSS at day 8 (n=15). (F–G) Protein levels of TNFα and IL1β cytokines were measured in colon samples by ELISA. Error bars indicate mean±SD of three independent experiments. P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (**p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001). (H) Total protein lysates isolated from the colon tissues of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with or without DSS at day 8 were analysed for phosphorylated and total p65 and p38. Actin was used for normalisation. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; UT, untreated; WT, wild type.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp006.pdf (339.4KB, pdf)

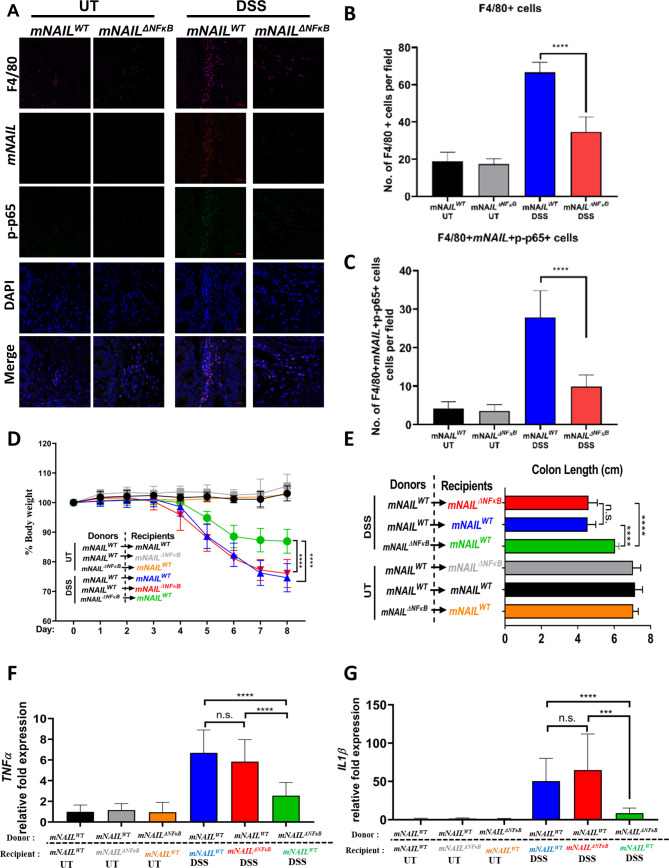

Colons from DSS-treated mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice at day 8 were stained with mNAIL-specific fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) probe, p-p65 and p-p38 antibodies and analysed using confocal microscopy. We only detected basal mNAIL expression and did not observe any positive staining for p-p65 and p-p38 in the UT colon sections of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice. On DSS stimulation, infiltration of F4/80 cells increased in mNAILWT colons. Costaining of F4/80 and mNAIL showed that the infiltrated macrophages are the major source of mNAIL expression in DSS-treated colons (figure 6A–C-right-panel). Furthermore, only mNAIL expressing F4/80+ cells showed dramatic increase in p-p65 (figure 6A) and p-p38 (online supplemental figure 6A). Similar to our western blot analysis (figure 5H), we observed a dampened induction of p-p65 and p-p38 in the mNAILΔNFκB mice as compared with mNAILWT mice treated with DSS (figure 6A–C and online supplemental figure 6B). Finally, H&E staining of the colon tissues suggested more severe pathology in mNAILWT mice compared with mNAILΔNFκB mice (online supplemental figure 6C, D). These results, together with our previous western blot analysis, suggest that mNAIL expression in colon-infiltrating macrophages regulates phosphorylation of p65 and p38 and hence inflammatory programme in these immune cells.

Figure 6.

mNAIL acts via immune cells to regulate inflammation. (A) Colon sections of the DSS-treated mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice at day 8 were stained with mNAIL specific FISH probe, F4/80 and p-p65 antibodies. Tissue slides were analysed for the indicated molecules by confocal microscopy. (B) Graph shows quantification of the number of F4/80+ cells from A. (C) Graph shows quantification of the number of F4/80+p-p65+cells from A. Error bars indicate mean±SD of three independent fields examined per mouse (n=3 per group). ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; n.s., not significant. P values were calculated by two-tailed Student’s t-test method. (D) mNAILWT or mNAILΔNFκB bone marrow reconstituted mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice were treated with DSS for 8 days. Graph shows the body weight measurements from mice monitored for 8 days (E) and the colon length at day 8. Graphs show gene expression analysis of (F) TNFα and (G) IL1β in the colon tissues of different bone marrow reconstituted groups treated with DSS for 8 days by qPCR. Data are normalised to actin. Error bars indicate mean±SD of two independent experiments (total n=12). P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; n.s., not significant). DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; UT, untreated; WT, wild type.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp007.pdf (361.4KB, pdf)

Indeed, the reduced infiltration of immune cells in mNAILΔNFκB mice, which was also observed in p38 myeloid specific KO mice,23 can be explained by the reduction in expression of CCL2 gene (figure 5E), a key mediator of monocyte recruitment to the inflamed tissue.21 In line with our finding, in colitis model of p38 but not in p65 KO mice, it has been shown that expression of chemokines such as CCL2, CCL3 and CXCL10 was reduced as compared with WT mice which resulted in reduced infiltration of immune cells.23 25 CCR2–CCL2 dimerisation is very important for Ly6Chi cells in bone marrow which give rise to macrophages that are later recruited to inflamed area.27 Much like DSS-treated mNAILΔNFκB mice, the colitis model of p38 KO mice show reduced levels of Ly6Chi cells in bone marrow which results in less F4/80 infiltration to the colon.23

Importantly, our results showed that mNAIL is not induced in intestinal epithelial cells and there is no difference in TNFα expression between mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice (online supplemental figure 7A, B). These results showed that BMDMs are possibly the major source of mNAIL expression and phenotypes seen may stem from these cells, we performed bone marrow transplantation followed by DSS stimulation (figure 6D). We irradiated mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice and transplanted bone marrow cells isolated from mNAILWT or mNAILΔNFκB mice (figure 6D). mNAILWT or mNAILΔNFκB bone marrow reconstituted mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB animals were treated with DSS and body weight was measured for 8 days. As compared with mNAILWT bone-marrow transplanted mNAILWT group (blue), mNAILWT bone-marrow reconstituted mNAILΔNFκB mice (red) showed similar degree of body weight loss, reduction in colon length and expression of TNFα and IL1β (figure 6D–G). However, when compared with mNAILWT bone-marrow transplanted mNAILWT group (blue) or mNAILWT bone-marrow transplanted mNAILΔNFκB group (red), mNAILΔNFκB bone marrow reconstituted mNAILWT group (green) displayed lesser reduction in body-weight and colon length and showed lower expression of TNFα and IL1β (figure 6D–G).

gutjnl-2020-322980supp008.pdf (412.9KB, pdf)

Taken together, these results suggest that the differences in mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice in the DSS model stem from the immune cells, particularly from the infiltrated myeloid cells. These results also suggest that mNAILΔNFκB mice exhibit impaired NFκB and p38 activity leading to reduced inflammation in colon on DSS treatment. Reduced inflammatory cytokines such as CCL2 in mNAILΔNFκB mice explain the reduced precursor cell population in bone marrow of these mice.28 Reduction in inflammatory cytokines expression in mNAILΔNFκB mice may be attributed to reduced activation of p38 and p65, which are well-known upstream events that positively cooperate to regulate transcription of inflammatory genes in response to inflammatory stimuli.

NAIL sequesters Wip1 phosphatase away from its substrates p65 and p38

It has been previously shown that Wip1 phosphatase negatively regulates inflammatory gene expression by dephosphorylating p6529 and p38.30 Indeed, decreased activation of p65 and p38 was seen in the absence of mNAIL (figures 4M and 5H). As numerous signalling pathways can be activated by TNFα stimulation, we comprehensively analysed most immediate downstream pathways which are activated on TNF receptor ligation (online supplemental figure 7C). Based on the fact that p65 and p38 phosphorylation were specifically affected in NAIL expressing cells, we hypothesised that Wip1 phosphatase, which affects these two substrates,31 might be a major effector of NAIL. Indeed, enzyme sequestration is a well-known regulatory mechanism on controlling cellular events.32–34 To test this, we checked Wip1-p65 interaction in colons of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with and without DSS and BMDMs treated with and without LPS. We found more Wip1 is bound to p65 in mNAILΔNFκB colon and BMDM cells even on stimulation and hence, p65 activation is defective (figure 7A, B and online supplemental figure 7D–F). We also found that in mNAILΔNFκB MEFs and BMDM cells, si-Wip1 rescued IL1β and TNFα expression and phosphorylation levels of p65 and p38 proteins, further suggesting that Wip1 is a key determinant of NAIL action (online supplemental figure 8). Taken together, these results suggest that NAIL can exert its function in trans by sequestering Wip1 phosphatase away from p65 or other Wip1 substrates like p38. It is possible that other substrates of Wip1 may also play a role in the described phenomenon consequent to the induction of NAIL. Given that this induction is dependent on the p65 subunit of NFκB, NAIL could be the key factor required for full-blown inflammatory responses in an evolutionarily conserved fashion.

Figure 7.

mNAIL sequesters Wip1 phosphatase away from its substrate in vivo. (A) Colon tissues were collected from mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice (n=4) treated with and without DSS for 8 days. (A) p65 protein was immunoprecipitated and coprecipitated proteins were analysed by western blot. Actin was used as a loading control. Each replicates are indicated as #1, #2, #3 and #4. (B) Graph shows quantification of coprecipitated Wip1 from A) (total n=4). Error bars indicate mean±SD of four replicates. P values were calculated using Student’s t-test method (**p<0.01; ***p<0.001). (C) Summary of phenotypes of p65, p38 myeloid specific knock mice, Wip1 null mice and mNAILΔNFκB in DSS model. Model based on our studies. (D) In the colitis model, in the presence of NAIL, activation of p38 and p65 is coordinated in a timely manner. On intestinal damage and release of microbiota to the colon, myeloid progenitor cells differentiate into immature myeloid cells which give rise to macrophages that infiltrate inflamed colon and express inflammatory genes. In the absence of NAIL, Wip1 prevents phosphorylation of p65 and p38 which leads to defects in generation of immature myeloid cells, reduction of recruitment of macrophages and deregulated expression of inflammatory genes. In the absence of TNFα or other inflammatory stimuli, Wip1 phosphatase is bound to p65 and its other targets such as p38. On activation of NFκB by TNFα, p65 is released from IκB proteins and p65 accumulates in the nucleus to activate target genes such as the NAIL lncRNA. Phosphorylation of p65 (p–p65) by a number of kinases mainly (IKKs) in the cytoplasm is critical for it to effectively bind to a subset of target genes, and subsequently, recruit p300 histone acetyltransferase for activating chromatin remodelling and for effectively kick-starting NFκB target gene expression. Meanwhile, NAIL lncRNA stimulated due to activation of p65 and squelches Wip1 phosphatase away from p65 or other Wip1 targets such as p38 thereby temporally regulating the kinetics of p65 and p38 phosphorylation and hence activation of genes dependent downstream of these important pathways. In the absence of NAIL, p65 and other Wip1 targets (p38) are avidly bound by Wip1 even after stimulation and this leads to reduced p-p65 and p-p38 levels and also reduced p300 recruitment to target genes along with lesser interaction of p38 and NFκB targets, resulting in decreased expression of the inflammatory genes. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; UT, untreated; WT, wild type.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp009.pdf (357.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

It is very well established that intestinal microbiota plays a key role in the development of UC. A multitude of regulatory checkpoints, regulated mainly by NFκB and p38, collectively coordinate the intensity and duration of the inflammatory response.35 36 In normal conditions, mucosal immune system acts as an effective defence system against gut microbiota while maintaining the balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses. This balance, in UC, is highly impaired and shifted towards hyperactive proinflammatory side, causing increased number of immune cells and high levels of cytokine secretion.3 While the impact of NFκB and p38 on initiating inflammatory responses is well established, how the proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory responses are kept in balance is unclear. Hence, understanding how these signalling pathways are controlled is of great clinical value towards developing novel drug targets for therapeutic intervention in inflammatory diseases.

This study represents the first of its kind, where mouse genetic tools were used to identify novel lncRNAs that are directly and specifically regulated by NFκB signalling. We identified NAIL (anti-sense direction to IL7 gene) as the only evolutionarily conserved lncRNA across mice and humans. NAIL is specifically induced by inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and TLR4 ligand LPS in a p65-dependent fashion across cell types.

CRISPR-mediated deletion of NFκB binding motifs upstream of NAIL led to the loss of its expression and decreased inflammation in vivo and in vitro. NAIL-deficient cells showed a reduction of p38 and p65-transactivation and subsequent decline in expression of key p38 and NFκB target genes. NFκB and p38 have been shown to be required for the expression of proinflammatory and chemoattractant genes including Cxcl1, Cxcl2, TNFα and IL1β 30 for full-blown inflammation. Most notably, loss of NAIL phenocopies p38 or p65 loss in vivo in DSS model as published by other laboratories23 25 37 (figure 7C). Our in vitro BMDM experiments (figure 4G–M) and in vivo DSS model clearly demonstrated that infiltrated macrophage cells are the major source of mNAIL expression and infiltration of F4/80+ cells are dampened in mNAILΔNFκB colons (figure 6A, B). Furthermore, only NAIL expressing F4/80+ cells showed dramatic increase in p-p65, suggesting that NAIL acts in mainly through immune cells for its mechanism of action (figure 6A–C). Indeed, bone marrow reconstitution experiment further proved this point as the DSS phenotype observed in mNAILΔNFκB mice was rescued on reconstitution of mNAILWT bone marrow into irradiated mNAILΔNFκB mice. Therefore, we can conclude that these phenotypic effects stem from the immune cells, particularly the infiltrated myeloid cells (figure 6D–G). Interestingly, unlike p38 KO mice, p65 KO mice do not show defects in the infiltration of macrophage cells to the inflamed colon, which clearly highlights that simultaneous activation of both these pathways is critical for successful mounting of inflammation.

Our findings clearly explain that NAIL sequesters Wip1 away from p65 and p38 simultaneously to enable an orchestrated response that leads to (a) differentiation of precursor cells into immature myeloid cells in bone marrow, (b) recruitment of macrophages to inflamed area and (c) expression of inflammatory genes. Indeed contrary to NAIL, p65 or p38 null mice, Wip1 null animals show enhanced inflammation37 (figure 7C). As inflammatory responses and phenotypes observed in NAIL loss of function mice are inverse of what is seen in Wip1 KO mice and they phenocopy the combination of the phenotypes observed in p38 and p65 KO models, it is apparent that NAIL is the missing link that explains the coactivation of the two essential pathways, NFκB and p38, by Wip1 in inflammation.

In physiological conditions, regulation of inflammatory control includes multiple layers of responses. As in the example of DSS-induced colitis model, the first response is the damage in the epithelial barrier which evokes maturation and recruitment signals in bone marrow.38 On sensing the damage signals and penetration of the microbiota to the colon, myeloid progenitor cells differentiate into immature myeloid cells which later on give rise to macrophages that are recruited to the inflamed areas in colon39 and express inflammatory genes (figure 7D). Indeed, p38 has been shown to regulate the differentiation of the myeloid progenitor cells into immature myeloid cells and later on via regulating the required chemoattractans that lead to infiltration of the macrophages into the inflamed colon.23 40 41 In the next stage, on activation of NFκB pathway, these cells express the proinflammatory cytokines for full-blown inflammatory response.42 As these two important pathways, p38 and NFκB, have to be coactivated in a timely manner,43 NAIL acts as a bridge to coordinate the activity of these two essential pathways in colitis.

In chronic diseases such as IBD, immunosuppressive drugs are used to partially block NFκB activity.3 Finer dissection of the role of NAIL in chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer may present new insights to design better and more selective anti-inflammatory drugs. Such NAIL inhibitors could also be more efficacious since they simultaneously target both NFκB and p38 signalling. As compared with non-inflamed controls, NAIL expression is significantly enhanced in the inflamed colon tissues (figure 1G) suggesting that NAIL expression is highly correlated with NFκB activity and may serve as a biomarker and therapeutic target for IBDs and other diseases with inflammation as an underlying cause.

Methods

BMDMs isolation and stimulation

BMDMs were isolated from femurs and tibias of sibling 8–10-week-old mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice. Cells were plated on bacteriological plastic plates in DMEM with 30% L929 conditioned medium for 4 days. On day 4, remove non-attached cells and wash with prewarmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and add fresh medium. On day 7, cells were dissociated using 5 mM PBSethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and cell scraper. Differentiated BMDMs were stained by CD11b and F4/80 antibodies. Differentiated BMDMs were stimulated with LPS (200 ng/mL) for the indicated time points for protein isolation, RNA isolation and chromatin immunoprecipitation.

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and analysis

Total RNA was isolated by using Trizol from immortalised WT and p65 and Ikkβ KO (-/-) MEFs that have been described previously.44 Cells were either stimulated with 10 ng/mL TNFα for 45 and 90 min or vehicle control. RNA-seq library was prepared by Illumina Truseq Total RNA sequencing kit according to manufacturer instructions. Paired-end sequencing was performed using Illumina Nextseq, 2×76 bp. Base quality assessment of raw sequence was performed using FastQC v0.11.8 and Trimmomatic v0.321 was used to filter low quality bases and adapter sequences. By using HISAT2 V.2.1, spliced alignment was performed on the quality trimmed sequences against Mus musculus (mm10) genome index which consist of transcriptome splicing information. Stranded alignment (first-strand) was applied and the alignment was finally coordinate sorted using Samtools V.1.8. Gene-level expression counts were quantified (strand-specific read counting) using featureCounts (subread-V.1.6.2 package) by reference to the gene annotation obtained from Ensembl (V.96) database.

Differential genes expression analysis was performed by first removal of genes with very low reads count using filterByExp() function in edgeR V.3.26.4 package. Library sizes were recalculated after the filtering. Genes with fold change ≥ 2 and a false discovery rate (FDR)<0.05 were identified as significant differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Differentially expressed lncRNAs were extracted with reference to GENCODE lncRNA annotation of respective genomes.

RNA was isolated from the colon tissues of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with or without DSS. RNA-Seq library was prepared by Illumina Truseq Total RNA sequencing kit according to manufacturer instructions. Paired-end sequencing was performed using Illumina Hiseq, 2×150 bp. DEGs were identified by comparing DSS-treated mNAILΔNFκB versus DSS-treated mNAILWT and DSS-treated mNAILWT versus UT mNAILWT .

RNA sequencing data of UC patients were obtained from NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), SRP125961 (GEO: GSE107593). Raw sequences were subjected to the same analysis process above and were aligned to Homo sapiens (GRCh38) genome index. DEGs were identified with the same threshold (fold change ≥ 2, FDR<0.05).

RNA isolation and real-time qPCR

Total RNA was extracted by Trizol and column purified using RNeasy Mini Kit for gene expression analysis. 1 µg RNA was used as a template for reverse transcription reaction using Maxima first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). Then, real-time PCR was performed from diluted cDNAs using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad). Relative gene expression was analysed by ∆∆CT method by normalising experimental Ct values to β-actin. Primers are indicated in the online supplemental table 1.

gutjnl-2020-322980supp010.pdf (111.3KB, pdf)

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted using Totex buffer (20 mM Hepes at pH 7.9, 0.35M NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM EGTA, 50 mM NaF and 0.3 mM NaVO3) supplemented with complete protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Immunoblotting was performed with following antibodies: anti-p-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182) 3D7 (Cell signalling; #9215S), anti-p38 (Santa Cruz; #sc-728), anti-p-p65 (Ser536) (Cell signalling; #3031 L), anti-p65 (Santa Cruz; #sc-8008), anti-actin (Sigma; #A2066), anti-HSP90α/β (F-8) (Santa Cruz; #sc-13119), p-IKKα/β (Ser176/180) (Cell signalling; #2697S), IKKα/β (H-470) (Santa Cruz; #7607) (online supplemental table 1).

ELISA analysis

Total protein was extracted from the colon tissues and TNFα and IL1β protein levels were quantified using Quantikine ELISA kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed as previously described.45 Briefly, 20 µg of total protein was incubated in reaction buffer (50% glycerol, 200 mM Hepes, pH 7.9, 4 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 4 mM DTT), 2 µg polydI-dC, 1% NP40 and [γ-32P] radiolabelled DNA probe for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were separated on 6% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel, and the gel was dried and exposed to BAS-IP Image plate (Fuji) for scanning with Typhoon FLA 7000 (GE Healthcare). Radiolabelled probes: NF-κB:5′-TCAACAGAGGGGACTTTCCGAGAGGCC-3′, AP-1:5′-CGCTTGATGACTCAGCGGGAA-3′.

Flow cytometry analysis

Bone marrow cells were isolated from mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice treated with and without DSS for 8 days. Cells were treated with ammonium-chloride-potassium (ACK) lysis buffer (Lonza) to eliminate red blood cells. Cells (~1×106 cells) were incubated with CD11b (PE), Ly6C (BV711) and Ly6G (FITC) fluorescence conjugated antibodies for 20 min at room temperature. To identify the stem cell populations, cells were stained with Lineage antibody cocktail (APC), c-KIT (PercpCy5.5), Sca-1 (FITC), CD34 (PE), IL7ra (PeCy7) and CD16/32 (APCcy7) (BD Biosciences) After antibody incubation, cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 1% FBS and 2 mM EDTA and acquired using FACS LSR2 instrument (Becton Dickenson). Data were analysed using Flow Jo software.

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation

Custom Stellaris RNA FISH probes were designed against mNAIL by utilising the Stellaris RNA FISH Probe Designer (Biosearch Technologies, Petaluma, CA). FISH was performed using the mNAIL Stellaris FISH Probe set labelled with Quasar 570, according to the manufacturer’s instructions available online at www.biosearchtech.com/stellarisprotocols with slight modification. Briefly, colon tissues were sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm using a microtome and mounted onto a microscope slide. Tissue sections were immersed in 100% xylene for 10 min and an additional 5 min with fresh 100% xylene. Next, slides were immersed in 100% ethanol for 20 min followed by incubation in 95% ethanol for 10 min. Subsequently, antigen retrieval by citrate buffer was performed (slides were heated in a microwave submersed in 1X citrate unmasking solution until boiling was initiated and kept for 20 min at a subboiling temperature (95°−98°C)). After allowing the slides to cool down on bench top for 20 min, slides were washed in dH2O three times for 5 min each and blocked with blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)) for 1 hour at room temperature. Subsequently, blocking solution was removed and Alexa Fluor 647 antimouse F4/80 antibody (Clone:BM8, Cat# 123122, Biolegend) diluted in blocking solution and added onto slides for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were washed with 1X PBS three times for 5 min. Tissue sections were permeabilised in 70% ethanol for at least 1 hour at room temperature. After washing slides with 1X PBS twice for 2–5 min, slides were incubated with hybridisation buffer (SMF-HB1-10, Stelleris) containing NAIL probe (125 nM) and antibodies (1:1000 dilution, phospho-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) Rabbit mAb, Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate, clone: 93H1, Cat#4886, CST or phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) Rabbit mAb, Alexa Fluor 488 Conjugate, clone: 3D7, #41768, CST) in a humidified chamber (150 mm tissue culture plate sealed with parafilm; a single water-saturated paper towel placed alongside the inner chamber edge) for overnight in the dark at 37°C. After incubation, slides were immersed in Wash Buffer A (SMF-WA1-60, Stellaris) in the dark at 37°C for 30 min to allow the submerged coverglass fall off from the slides. Finally, Wash Buffer A was removed, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added to counterstain the nuclei and slides were covered with a coverglass for imaging by using ZEISS LSM800 microscopy.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

BMDM cells derived from mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB cells were stimulated with LPS (200 ng/mL) for 4 hours. Cells were crosslinked on the plate with disuccinimidyl glutarate (DSG) (1.5 mM) (Thermo Fischer Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking. After removing DSG, cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min and the reaction was quenched with a final concentration of 0.125M glycine. After lysis, cell lysates were sonicated of an average size of 150–600 bp fragments and precleared with Protein A/G sepharose beads for 1 hour. After centrifugation, 2% input was stored as an input. Lysates (~4 million cells) were incubated with 4 µg p65 (Santa-Cruz, sc-372) antibody overnight at 4°C on a rotator. Immune complexes were immunoprecipitated with protein A/G sepharose beads and samples were eluted in a final volume of 60 µL after reverse crosslinking overnight. ChIP-qPCR was performed using TNFα and CXCL2 promoter-specific primers. Enrichment was calculated by % input method.

Immunoprecipitation assay

Cells were harvested and lysed in IP lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)]. Protein concentration was measured by Bradford method. p65 was immunoprecipitated after incubating cell lysate with p65 antibody for 6 hours and an additional 2 hours with Protein G Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The beads were washed three times with washing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N′, N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100) and immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted by boiling the beads in 2X loading sample buffer (LDS) (Invitrogen) for 10 min. Immunoblotting was performed as described above with the following antibodies: anti-Wip1 antibody (1:1000 Cell signalling; #11901), anti-p65 antibody (1:1000, Santa Cruz; sc-8008).

Generation of mice

We designed crRNAs targeting 5′-TAGGGTTTAAAAGCGCATCC-3′ and 5′-AGTCTGGGAGTTTCCGATCC-3′ in the 5′UTR of Gm16685, then generated NAILΔNFκB mice by introducing the CAS9/tracrRNA/crRNAs complex into the oocytes with electroporation, as described previously.46 In brief, CARD HyperOva (0.1 mL, Kyudo, Tosu, Saga, Japan) was injected into the abdominal cavity of C57BL/6N females [Japan SLC (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan)] followed by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) (five units, ASKA Pharmaceutical). After 14 hours of hCG injection, the oocytes were collected from the ampulla of the oviduct and then were used for in vitro fertilisation.47 The fertilised eggs were electroporated with the CAS9/tracrRNA/crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex, and then transplanted into the ampulla of the oviduct of pseudopregnant females. After 19 days, offspring were obtained by natural birth or Caesarean section. We genotyped the offspring by PCR with KOD-Fx neo (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan) and a primer set (Fw: 5′-TTAGATTTGATCAGGGAGC-3′, Rv: 5′-TCAGTGGTTTTCAGCCACTT-3′) and direct sequencing. The PCR condition was 94°C for 3 min, denaturing at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s, elongation 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles total, followed by 72°C for 2 min. Briefly, we obtained 22 pups from 89 treated zygotes and seven out of 12 analysed pups carried the 80 or 82 bp deletion. We crossed these mice to WT animals for two generations to purify 80 bp deletion mutants and also decrease the risks of off-target cleavage. Then heterozygous mutants were crossed to obtain homozygous 80 bp deletion mutant mice which was confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Subsequently, KO mouse was crossed back to WT to obtain heterozygous animals which were used as breeders to generate littermate WT, HT and KO groups for experiments.

Animal studies and ethical requirements

DSS model was conducted as previously described.48 Briefly, mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB mice were fed with 3% DSS in drinking water for 4 days and replaced with normal water for another 4 days. Body weight was measured daily and mice were sacrificed at day 8. Colon (distal) and bone marrow tissues were harvested and used for downstream analysis including RNA, protein and flow cytometry analysis. Intestinal epithelial cells were isolated for gene expression analysis from the colon tissues as reported previously.49 DAI was assessed by using the evaluation system: (i) body weight loss (no weight loss was scored as 0 points, weight loss of 1%–5% as one point, 5%–10% as two points, 10%–20% as three points and more than 20% as four points);50 stool consistency (0 point was given for well-formed pellets, two points for pasty and semiformed stools that did not stick to the anus and four points for liquid stools that remained adhesive to the anus). For histological scoring, the sections were graded in a blind manner by two independent investigators with a range from 0 to 3 for the amount of inflammation, depth of inflammation and with a range from 0 to 4 for the amount of crypt damage. For bone marrow transplantation, single cell suspension of bone marrow cells was obtained from the tibia and femur of mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB 8–10 weeks old (male) donor mice. 3×106 bone marrow cells were injected via the tail vein into mNAILWT and mNAILΔNFκB lethally irradiated (9.5 Grey) 8–10 weeks old recipient (male) mice. Two weeks’ post-transplantation, the mice were placed on the DSS-induced colitis model.

All animal studies were conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at A*STAR (Singapore). All procedures were approved under the IACUC protocol ID # 181 396.

Statistical analysis

Two-tailed Student’s t-test was performed for statistical analysis of between two groups. PRISM software V.7 was used to plot graphs and for statistical analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Eun Myoung Shin for the electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis of NFκB knock out cells. We are thankful to Dr Chen Li Chew for suggestions and critical reading and Sumita Ananthkrishnan for proof-reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

SCAınıl and LW contributed equally.

Contributors: SCA, BU and VT conceived the study and designed the experiments. LW and BU performed mechanistic experiments with the help of QFN. SCA, LW performed mouse DSS modelling experiments with the help of QFN, TN and MI generated mNAIL-ΔNFκB mice. JYHC performed RNA-seq and bioinformatics analyses. VT directed the study and wrote the paper with LW and SCA.

Funding: VT lab is supported by NRF-CRP17-2017-02 grant and core funding from IMCB A*STAR. This research is supported by the Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council (NMRC/OFYIRG/18MAY-0008 to SCA). BU was supported by the SINGA scholarship awarded by A*STAR, Singapore. Ikawa lab. is supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)/Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants (JP18K14612 to TN and JP17H01394 to MI).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. RNA sequencing data of MEF cells (GSE157476 - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157476) and RNA-sequencing data of mice colon tissues (GSE138235- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE138235) were deposited in GEO open access repository.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2014;14:329–42. 10.1038/nri3661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen Z-H, Zhu C-X, Quan Y-S, et al. Relationship between intestinal microbiota and ulcerative colitis: mechanisms and clinical application of probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:5–14. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atreya I, Atreya R, Neurath MF. NF-kappaB in inflammatory bowel disease. J Intern Med 2008;263:591–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohn HM, Dave M, Loftus EV. Understanding the cautions and contraindications of immunomodulator and biologic therapies for use in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:1301–15. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karin M, Greten FR. NF-kappaB: linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5:749–59. 10.1038/nri1703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Connor PM, Lapointe TK, Beck PL, et al. Mechanisms by which inflammation may increase intestinal cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:1411–20. 10.1002/ibd.21217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruland J. Return to homeostasis: downregulation of NF-κB responses. Nat Immunol 2011;12:709–14. 10.1038/ni.2055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derrien T, Johnson R, Bussotti G, et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res 2012;22:1775–89. 10.1101/gr.132159.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrow J, Frankish A, Gonzalez JM, et al. GENCODE: the reference human genome annotation for the encode project. Genome Res 2012;22:1760–74. 10.1101/gr.135350.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diederichs S. The four dimensions of noncoding RNA conservation. Trends Genet 2014;30:121–3. 10.1016/j.tig.2014.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Shishkin AA, Zhu X, et al. Evolutionary analysis across mammals reveals distinct classes of long non-coding RNAs. Genome Biol 2016;17:19. 10.1186/s13059-016-0880-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garber M, Yosef N, Goren A, et al. A high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation approach reveals principles of dynamic gene regulation in mammals. Mol Cell 2012;47:810–22. 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.07.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barish GD, Yu RT, Karunasiri M, et al. Bcl-6 and NF-kappaB cistromes mediate opposing regulation of the innate immune response. Genes Dev 2010;24:2760–5. 10.1101/gad.1998010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt SF, Larsen BD, Loft A, et al. Acute TNF-induced repression of cell identity genes is mediated by NFκB-directed redistribution of cofactors from super-enhancers. Genome Res 2015;25:1281–94. 10.1101/gr.188300.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin F, Li Y, Dixon JR, et al. A high-resolution map of the three-dimensional chromatin interactome in human cells. Nature 2013;503:290–4. 10.1038/nature12644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogler G, Brand K, Vogl D, et al. Nuclear factor kappaB is activated in macrophages and epithelial cells of inflamed intestinal mucosa. Gastroenterology 1998;115:357–69. 10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70202-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schreiber S, Nikolaus S, Hampe J. Activation of nuclear factor kappa B inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1998;42:477–84. 10.1136/gut.42.4.477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang R, Ito S, Nishio N, et al. Dextran sulphate sodium increases splenic Gr1(+)CD11b(+) cells which accelerate recovery from colitis following intravenous transplantation. Clin Exp Immunol 2011;164:417–27. 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04374.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trottier MD, Irwin R, Li Y, et al. Enhanced production of early lineages of monocytic and granulocytic cells in mice with colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:16594–9. 10.1073/pnas.1213854109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity 2003;19:71–82. 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00174-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bain CC, Scott CL, Uronen-Hansson H, et al. Resident and pro-inflammatory macrophages in the colon represent alternative context-dependent fates of the same Ly6Chi monocyte precursors. Mucosal Immunol 2013;6:498–510. 10.1038/mi.2012.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, et al. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity 2012;37:1076–90. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Youssif C, Cubillos-Rojas M, Comalada M, et al. Myeloid p38α signaling promotes intestinal IGF-1 production and inflammation-associated tumorigenesis. EMBO Mol Med 2018;10. 10.15252/emmm.201708403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayle A, Luo M, Jeong M, et al. Flow cytometry analysis of murine hematopoietic stem cells. Cytometry A 2013;83:27–37. 10.1002/cyto.a.22093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waddell A, Ahrens R, Tsai Y-T, et al. Intestinal CCL11 and eosinophilic inflammation is regulated by myeloid cell-specific RelA/p65 in mice. J Immunol 2013;190:4773–85. 10.4049/jimmunol.1200057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otsuka M, Kang YJ, Ren J, et al. Distinct effects of p38alpha deletion in myeloid lineage and gut epithelia in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:1255–65. 65 e1-9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bain CC, Mowat AM. Macrophages in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Immunol Rev 2014;260:102–17. 10.1111/imr.12192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gschwandtner M, Derler R, Midwood KS. More than just attractive: how CCL2 influences myeloid cell behavior beyond chemotaxis. Front Immunol 2019;10:2759. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chew J, Biswas S, Shreeram S, et al. WIP1 phosphatase is a negative regulator of NF-kappaB signalling. Nat Cell Biol 2009;11:659–66. 10.1038/ncb1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim C, Sano Y, Todorova K, et al. The kinase p38 alpha serves cell type-specific inflammatory functions in skin injury and coordinates pro- and anti-inflammatory gene expression. Nat Immunol 2008;9:1019–27. 10.1038/ni.1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donehower LA. Phosphatases reverse p53-mediated cell cycle checkpoints. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111:7172–3. 10.1073/pnas.1405663111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng S, Ollivier JF, Soyer OS. Enzyme sequestration as a tuning point in controlling response dynamics of signalling networks. PLoS Comput Biol 2016;12:e1004918. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2006;7:85–96. 10.1038/nrm1837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blüthgen N, Bruggeman FJ, Legewie S, et al. Effects of sequestration on signal transduction cascades. Febs J 2006;273:895–906. 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schonthaler HB, Guinea-Viniegra J, Wagner EF. Targeting inflammation by modulating the Jun/AP-1 pathway. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70(Suppl 1):i109–12. 10.1136/ard.2010.140533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-κB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol 2011;12:695–708. 10.1038/ni.2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Zhang C, Chang F, et al. Wip 1 inhibits intestinal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Immunol 2016;310:63–70. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2016.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gorjifard S, Goldszmid RS. Microbiota-myeloid cell crosstalk beyond the gut. J Leukoc Biol 2016;100:865–79. 10.1189/jlb.3RI0516-222R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sartor RB. Mechanisms of disease: pathogenesis of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;3:390–407. 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verma A, Deb DK, Sassano A, et al. Activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates the suppressive effects of type I interferons and transforming growth factor-beta on normal hematopoiesis. J Biol Chem 2002;277:7726–35. 10.1074/jbc.M106640200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geest CR, Buitenhuis M, Laarhoven AG, et al. p38 MAP kinase inhibits neutrophil development through phosphorylation of C/EBPalpha on serine 21. Stem Cells 2009;27:2271–82. 10.1002/stem.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Medzhitov R, Horng T. Transcriptional control of the inflammatory response. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9:692–703. 10.1038/nri2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bradbury CM, Markovina S, Wei SJ, et al. Indomethacin-induced radiosensitization and inhibition of ionizing radiation-induced NF-kappaB activation in HeLa cells occur via a mechanism involving p38 MAP kinase. Cancer Res 2001;61:7689–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tergaonkar V, Bottero V, Ikawa M, et al. Ikappab kinase-independent IkappaBalpha degradation pathway: functional NF-kappaB activity and implications for cancer therapy. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:8070–83. 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8070-8083.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shin EM, Hay HS, Lee MH, et al. Dead-Box helicase DP103 defines metastatic potential of human breast cancers. J Clin Invest 2014;124:3807–24. 10.1172/JCI73451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Noda T, Sakurai N, Nozawa K, et al. Nine genes abundantly expressed in the epididymis are not essential for male fecundity in mice. Andrology 2019;7:644–53. 10.1111/andr.12621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tokuhiro K, Ikawa M, Benham AM, et al. Protein disulfide isomerase homolog PDILT is required for quality control of sperm membrane protein ADAM3 and male fertility [corrected]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:3850–5. 10.1073/pnas.1117963109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helke K, Angel P, Lu P, et al. Ceramide synthase 6 deficiency enhances inflammation in the DSS model of colitis. Sci Rep 2018;8:1627. 10.1038/s41598-018-20102-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Macartney KK, Baumgart DC, Carding SR, et al. Primary murine small intestinal epithelial cells, maintained in long-term culture, are susceptible to rotavirus infection. J Virol 2000;74:5597–603. 10.1128/JVI.74.12.5597-5603.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishii KJ, Koyama S, Nakagawa A, et al. Host innate immune receptors and beyond: making sense of microbial infections. Cell Host Microbe 2008;3:352–63. 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2020-322980supp001.pdf (149.6KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp002.pdf (387.3KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp003.pdf (643.7KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp004.pdf (311.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp005.pdf (470KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp006.pdf (339.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp007.pdf (361.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp008.pdf (412.9KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp009.pdf (357.7KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322980supp010.pdf (111.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. RNA sequencing data of MEF cells (GSE157476 - https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE157476) and RNA-sequencing data of mice colon tissues (GSE138235- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE138235) were deposited in GEO open access repository.