Abstract

Over the last few decades, scientists and clinicians have often focused their attention on the unbound fraction of drugs as an indicator of efficacy and the eventual outcome of drug treatments for specific illnesses. Typically, the total drug concentration (bound and unbound) in plasma is used in clinical trials to assess a compound’s efficacy. However, the free concentration of a drug tends to be more closely related to its activity and interaction with the body. Thus far, measuring the unbound concentration has been a challenge. Several mechanistic models have attempted to solve this problem by estimating the free drug fraction from available data such as total drug and binding protein concentrations. The aims of this review are first, to give an overview of the methods that have been used to date to calculate the unbound drug fraction. Second, to assess the pharmacokinetic parameters affected by changes in drug protein binding in special populations such as pediatrics, the elderly, pregnancy, and obesity. Third, to review alterations in drug protein binding in some selected disease states and how these changes impact the clinical outcomes for the patients; the disease states include critical illnesses, transplantation, renal failure, chronic kidney disease, and epilepsy. And finally, to discuss how various disease states shift the ratio of unbound to total drug and the consequences of such shifts on dosing adjustments and reaching the therapeutic target.

Keywords: protein binding, drug distribution, dose-response, drug transport, special populations, disease state(s)

Introduction

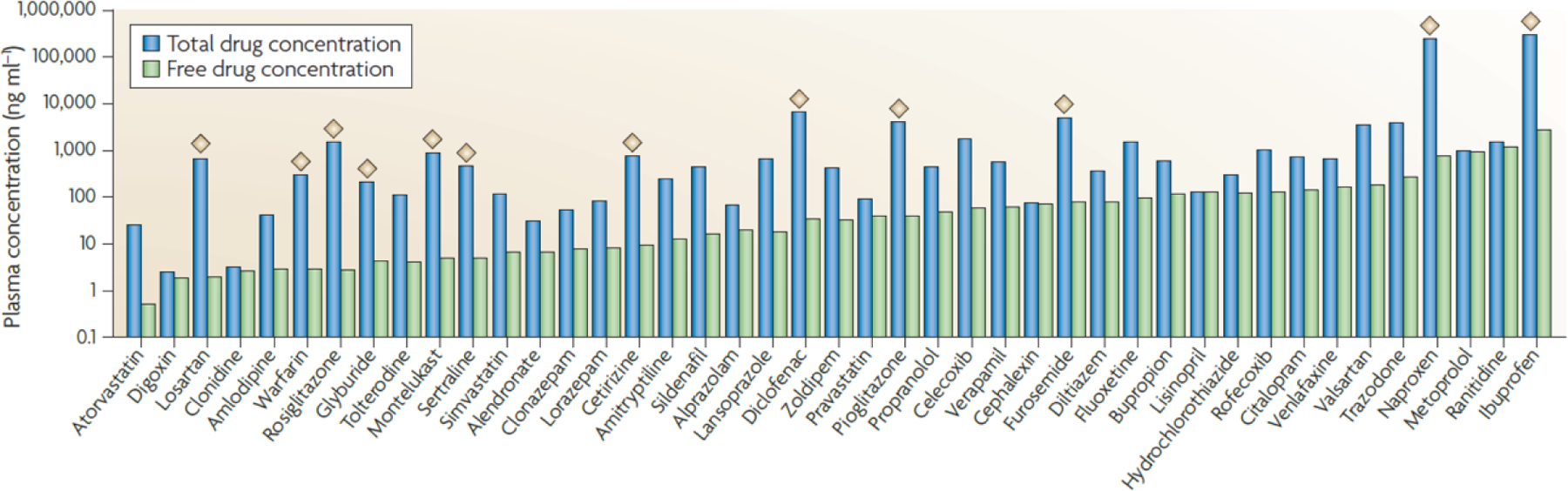

In vivo, drugs molecules can either be bound to plasma protein and to tissue proteins, be dissolved in lipids, or be in an unbound/free state. Furthermore, there is a pronounced variability in the degree to which drugs bind to proteins1 as shown in Figure 1 (in the order of increasing free concentrations in plasma). High plasma protein binding (PPB) is associated with moderately or highly lipophilic drugs, particularly acids. Despite the fact that binding of drugs to plasma proteins influences their disposition in the body, there seems to be a lack of agreement in the industry as to its importance: some drugs will proceed in development regardless of the unbound fraction whereas others are tuned to have PPB in an optimum range.2

Figure 1.

The plasma protein binding (PPB) of some of the top 100 most prescribed drugs. Many of the top 100 most prescribed drugs have greater than 98% PPB, as shown by approximately 2 log units difference in unbound and total plasma concentrations (indicated by the diamonds).2 Reproduced with permission from [2].

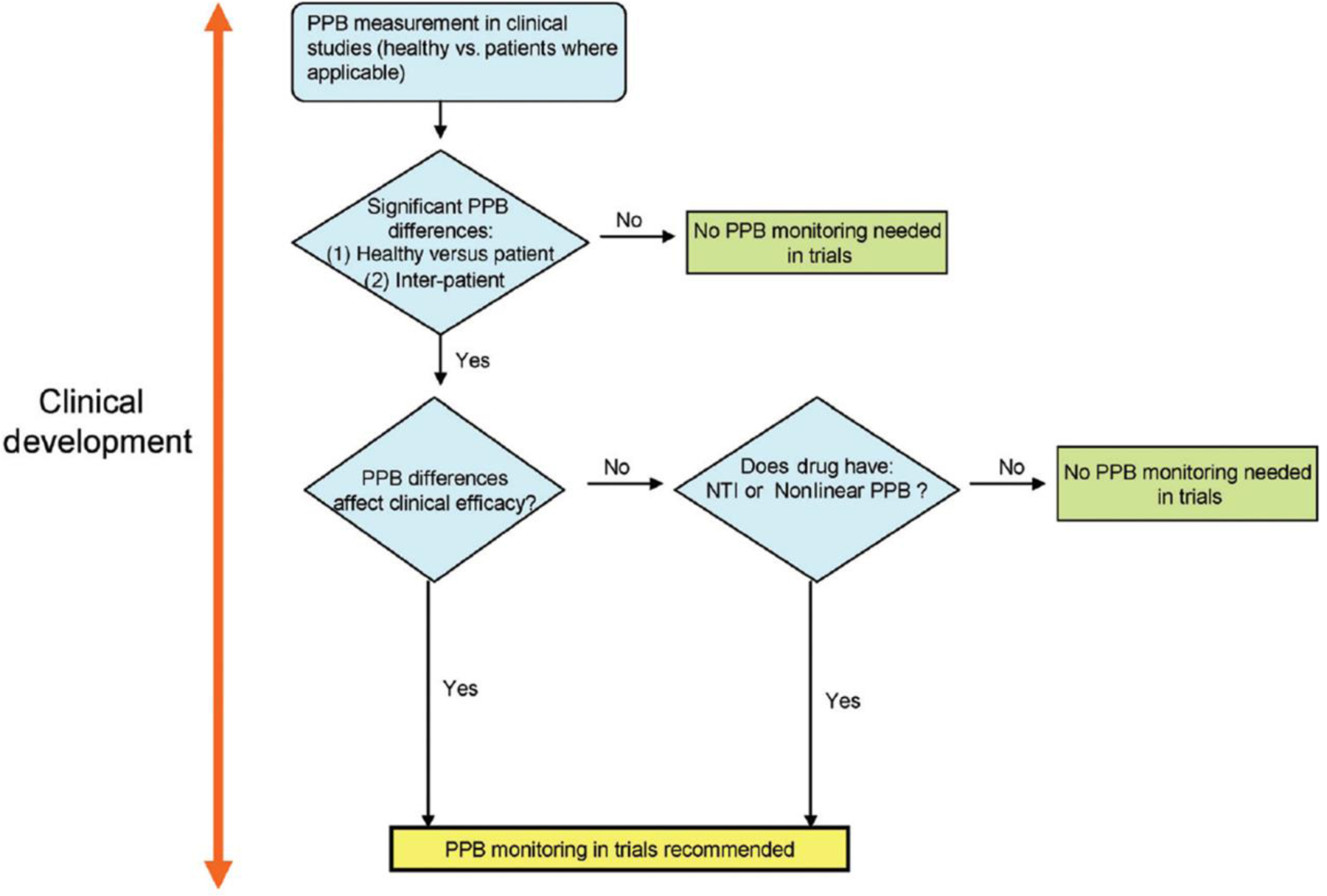

Evaluation of drug-protein binding and its influence on free drug concentrations has been an integral part of drug development. Its impact is evident in clinical study designs for drug interaction studies, special population studies, exposure-response analysis, and dose selection. Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) relationships can be explained by the free drug theory (FDT). Bohnert and Gan3 define FDT as the absence of energy-dependent processes; after steady state equilibrium has been attained, free drug concentration in plasma is equal to free drug concentration in tissue and only the free drug in the tissue is available for target receptor binding and therefore, pharmacologic activity.3 Although determination of free drug concentrations around receptors or enzymes is the most relevant, these are very difficult to measure; in clinical practice the free or total concentration in plasma is typically determined; subsequently, the concentration around receptors is considered to be proportional to the free plasma concentration. Free drug concentration and consequently PPB information amongst species is very useful in creating safety margins and guiding selection of first in human and human effective doses. Therefore, it is fundamental to understand the dissimilarities, if any, of PPB between healthy and patient populations; and if the PPB in a patient population is considerably altered, unbound fraction in plasma should be carefully clinically monitored (Figure 2).3 For older drugs, inter-patient variation in protein binding was mainly investigated after the drugs have been on the market; therefore, PPB-related dosing adjustment for these older drugs are mainly found in research publications. For recently developed drugs, for which protein binding was evaluated during development as described in Figure 2, the dosing guidelines typically include the information needed to deal with changes in PPB in the treated population. Nevertheless, even if PPB variability was investigated in clinical trials, the free drug concentration should still be monitored in patients with renal or hepatic impairment.

Figure 2.

Recommendation for evaluation of protein binding in the clinical development. The role of PPB on efficacy models needs to be rigorously evaluated and established throughout the preclinical and clinical development stages as suggested and outlined by this general scheme. PPB: plasma protein binding; NTI: narrow therapeutic index.3 Reproduced with permission from [3].

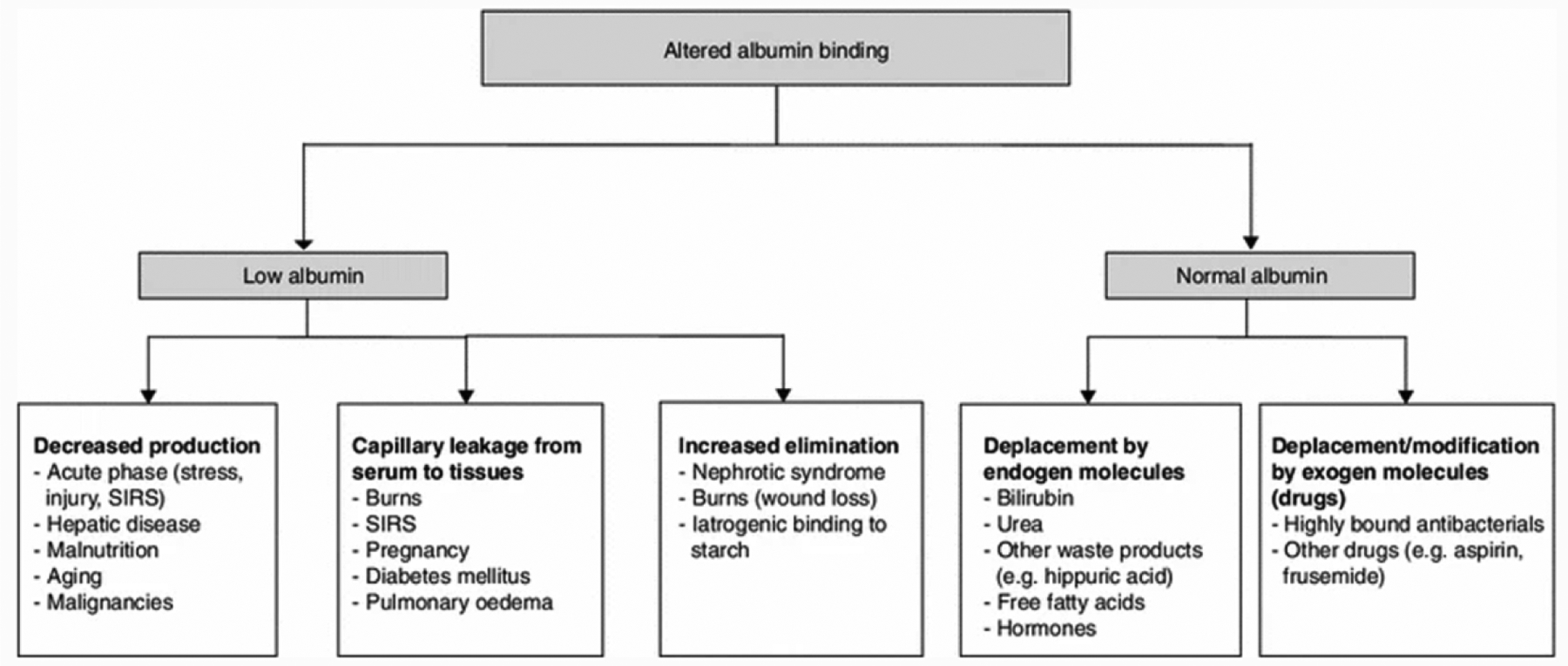

The common drug binding blood proteins are human serum albumin, lipoproteins, glycoproteins, and globulins. Several medications are highly bound to albumins and some patient presentations, such as burn injury patients, cancers, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, and renal disease are more likely to result in altered protein binding as outlined in Figure 3.1,4 Typically, only when the total drug concentration does not consistently and accurately reflect the unbound drug concentration at the PD target site, it is recommended to monitor both the total and free drug concentrations.1,3 It is essential for clinicians and academicians to acquire a high-level understanding of how to adjust drug dosing when there are changes affecting either drug clearance, volume of distribution, or protein binding. Ideally, free drug concentrations should always be measured rather than estimated, and they should be used to establish optimal clinical efficacy and minimal toxicity.4 Alternatively, for drugs titrated to effect, dosing can be adjusted based on the observed PD effect. When drug efficacy is not directly observable, a generic approach, where all patients receive the same dose, is applied because of the difficulties in assessing whether drug failure is happening.

Fig. 3.

Main factors responsible for alterations in drug-albumin binding. There are many patient presentations that will affect protein binding. The likelihood of altered protein binding is more common in some patient populations such as burn injury patients, cancer, diabetes mellitus, liver disease, and renal disease. SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome.4 Reproduced with permission from [4].

Nevertheless, some research articles express a different viewpoint on the importance of drug-protein binding. An article by Benet et al5, states that drug exposure would be a more relevant measure than individual PK parameters to assess drug-drug and disease-drug interactions. The authors further claim that protein binding may be clinically significant only for parenterally administered drugs with high extraction ratio (>70% bound to plasma proteins). Some examples of such drugs are lidocaine, midazolam, fentanyl, diltiazem, and propofol. Based on the therapeutic index (narrow) and kinetic-dynamic equilibrium time (short), changes in protein binding of a few orally administered drugs such as verapamil and propafenone, may yield a clinically significant response. The authors also recognized the importance of protein binding measurement in drug development and the usefulness of measuring unbound drug concentrations rather than total concentrations for narrow therapeutic index drugs.5 Even though Benet’s paper was very influential at the time of its publication, the pharmacokinetic model used in the paper was ultimately proved to be overly simplistic and to result in a mathematical artifact where the AUC incorrectly appears to be independent of the free fraction. According to Berezhkovskiy et al., new pharmacokinetic models, such as the parallel tube and the dispersion models, clearly show that the AUC and pharmacological activity of drugs are influenced by changes in plasma protein binding.6,7

A literature search was performed in PubMed using the words ‘unbound (free) drug’, ‘protein binding’, ‘dose adjustment’, ‘equations’, ‘pediatric’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘elderly’, ‘obesity’, ‘critical illness’, ‘renal failure’, ‘liver disease’, ‘transplant’, and ‘epilepsy’ to report selected scientific articles on unbound drug concentration and its effect on therapeutic efficacy in relevant special populations and disease states. The language was restricted to English. Table 1 summarizes the drugs analyzed in the articles that were retained in writing this paper. The objectives of this article are to look at the equations that to date have attempted to estimate unbound drug concentrations and to assess the impact of free drug concentration as opposed to total drug concentration monitoring. Additionally, this review explores if a dose adjustment is warranted in those special populations and diseases states when compared to patients with normal drug-protein binding levels.

Table 1.

Examples of studies where changes in drug-protein binding were investigated

| Special Populations / Disease States | Drug Investigated | Observation | Conclusion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric | Cefazolin | The median unbound cefazolin fraction is higher in neonates than in adults. | The authors recommend the assessment of cefazolin protein binding for optimization of neonatal cefazolin dosing. | Smits, A. (2012) [17] |

| Oxycodone | Neonates have slower clearance and older children have faster clearance when compared with adults. | The study showed that newborns should receive a lower dose of oxycodone IV while toddler, preschool, and school age children should receive a higher dose compared with adults to have similar exposure. | Zheng, L. (2019) [15] | |

| Vancomycin | The neonates population has a higher unbound vancomycin fraction compared to children and adults. | Future PK-PD research needs to integrate protein binding data to achieve dosing optimization of vancomycin. | Smits, A. (2018) [16] | |

| Elderly | Vancomycin | Renal clearance is significantly reduced in elderly individuals, even if serum creatinine remains constant. | Improved treatment outcome may be seen with vancomycin target AUC/MIC of 250–450 μg*h/mL. | Mizokami, F. (2013) [26] |

| Vancomycin | Vancomycin half-life and treatment outcome in elderly is influenced by severe hypoalbuminemia. | An AUC/MIC >450 μg*h/mL value is associated with nephrotoxicity in patients with severe hypoalbuminemia. | Mizuno, T. (2013) [27] | |

| Pregnancy | Prednisone and prednisolone | Prednisone and prednisolone are highly bound to CBG and albumin in plasma. CBG concentrations increase and albumin concentrations decrease during pregnancy. | Prednisone dose adjustment may not be required due to the lack of change in unbound prednisolone apparent oral clearance. | Ryu, PJ. (2018) [29] |

| Levothyroxine | Thyroxine binding protein levels are higher in pregnancy | An increased dose in levothyroxine from baseline is warranted in the majority of pregnant woman with a hypothyroid condition. | Soldin, OP. (2010) [30] | |

| Obesity | Daptomycin, ertapenem, ciprofloxacin, enoxaparin, dalteparin, glimepiride, sitagliptin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, norethisterone and ethinyl estradiol | Obesity has no impact on drug binding to albumin, however its impact on drug binding to alpha-1 acid glycoprotein is not clear. | Treatment regimens should be designed so that they account for any significant differences in volume of distribution and clearance in the obese. | Hanley, MJ. (2010) [31] |

| Alprazolam, cefazolin, daptomycin, lorazepam, midazolam, oxazepam, propranolol and triazolam | In the morbidly obese, most free drug concentrations were unchanged; in the daptomycin study, serum albumin concentrations were unchanged. The serum albumin concentrations were reduced in the propranolol study. | Serum protein concentrations seem unchanged except for AGP that appears elevated. Relevant PK changes have yet to be derived from these fluctuations. | Smit C. (2018) [36] | |

| Cefazolin | In morbidly obese individuals, unbound cefazolin subcutaneous tissue penetration is lower. | Cefazolin dose adjustments are required. Interstitial space fluid tissue concentration should guide cefazolin efficacy targets instead of unbound plasma concentration. | Brill, MJE. (2014) [37] | |

| Critical Illness | Beta-lactam antibiotics | Unbound beta-lactam concentrations are highly variable and unpredictable. | The authors observed a correlation between percent protein binding and plasma albumin concentrations only for flucloxacillin. | Wong, G. (2013) [41] |

| Daptomycin | Lower percentage of drug bound to serum protein in burn patients compared to healthy individuals. | An increased dose of daptomycin would be required in burn patients to compensate for the altered pharmacokinetics of the drug in thermal burn injury. | Mohr, JF. (2008) [44] | |

| Transplant Patients | Tacrolimus | The unbound tacrolimus in liver varies greatly from patient to patient; a 15-fold variation was observed. | Patients who experienced liver transplant rejection had lower unbound tacrolimus concentrations. | Zahir, H. (2004) [48] |

| Tacrolimus | The plasma concentration of unbound tacrolimus is altered by changes in blood composition. | For patients who have not achieved optimal tacrolimus dosing therapy, unbound tacrolimus plasma concentration should be monitored. | Sikma, MA. (2015) [49] | |

| Renal Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease | Various antibiotic classes | Patients with chronic kidney disease and end stage kidney disease are at higher risk of side effects from drugs due to altered pharmacokinetics. Renal failure complicates optimization of antibiotic therapy. | Knowledge of the pharmacodynamic properties of antibiotics is helpful in guiding clinicians in their decision to adjust or not drug dosing. | Eyler, RF. (2019) [52] |

| SGLT-2 inhibitors | The therapeutic effect of SGLT-2 inhibitors is reduced with a decrease in eGFR | In patients with moderate chronic kidney disease, doses of empagliflozin and dapagliflozin should not be reduced. Whereas, dose of canagliflozin should be reduced. | Scheen, AJ. (2015) [53] | |

| Plasma Exchange and Plasmapheresis | Various drug classes: antimicrobial, cardiotonic, antiviral agents and others | Low volume of distribution, regardless of the percentage of protein binding, is the pharmacokinetic parameter mostly influenced by plasma exchange procedure. | Drugs with low volume of distribution and high plasma protein binding are the most affected by plasma exchange. The authors suggest that the ceftriaxone dose be given after the exchange procedure. | Fauvelle, F. (2000) [57] |

| Rituximab | Rituximab was significantly cleared during plasmapheresis sessions. | The authors concluded that number of rituximab infusion sessions should be based on the amount of drug removed by plasmapheresis. | Puisset, F. (2013) [58] | |

| Epilepsy | Phenytoin | Phenytoin is highly bound to albumin. Changes in albumin concentrations or phenytoin binding affinity to albumin can impact free drug concentrations. | Free phenytoin concentration should be measured in case of hypoalbuminemia. It is not necessary in patients with normal albumin levels since the free portion is unchanged. | Montgomery, MC. (2019) [51] |

| Valproic acid | Low serum albumin correlates with elevated unbound valproic acid concentrations and clinical toxicity. | For therapeutic effect and decrease of drug toxicity, dosing of valproic acid should be guided by free drug plasma concentrations and not total drug concentrations. | Wallenburg, E. (2017) [60] | |

| Valproic acid | Even in the presence of normal or low total valproic acid concentrations, high unbound valproic acid concentrations can still occur. | High unbound valproic acid concentrations are associated with neurologic adverse effects. Dose adjustment should be based on unbound drug concentrations. | Doré, M. (2017) [61] |

Models for normalizing concentrations and estimating the free drug fraction

When it comes to individualized treatment, the traditional method to monitor total drug concentrations is often insufficient since drugs can reversibly bind to plasma proteins such as human serum albumin (HSA) and alpha-1 acid glycoprotein (AGP). A drug that is protein bound has limited distribution as it forms a large complex with the protein that cannot effortlessly cross cell or capillary membranes. As alternatives, the unbound or normalized drug concentrations are more pertinent parameters as they correlate much better with the amount of drug that can reach the target receptor and they provide a quantitative association between clinical PK and PD.1

Clinically, patients have demonstrated a broad variation in protein binding characteristics for a specific drug, which should be considered when dosing drugs with narrow therapeutic window.1 As such, it is critical to measure or at least estimate unbound plasma drug concentrations correctly and accurately.

Unbound concentrations can be difficult to measure and may be poorly understood by non-specialists. The unbound concentrations can also be calculated using the total concentration of drug and the concentration of binding proteins, but this required extra work for measuring protein concentrations. Several research and review articles deal with the technical aspects of methods for measuring free drug concentrations.8–10

Normalized total drug concentrations that take into account changes in protein binding can be obtained as an alternative to using free concentrations. For a certain free or total drug concentration value measured in a patient, the corresponding normalized total concentration can be defined as the concentration that would produce the same effect in an individual with typical drug-plasma protein binding and drug disposition. This way, the critical information necessary for individualized pharmacotherapy can be provided using equation 1, which can be used for drugs binding to any number of proteins with any number of binding sites.1

| (1) |

Where:

Ctn: normalized total concentration of drug (mol/L); Cf: free concentration of drug at equilibrium (mol/L); Bj: number of molecules of drug bound per molecule of jth protein in a mixture of binding proteins; Cmnj: normal total concentration of jth protein (mol/L) (j appears only as subscript).

When the drug binds to a single protein with one binding site, equation 1 can be simplified to equation 2.1 This equation is based on the quantified total drug concentration, the calculated or measured free concentration, and the ratio between normal and observed levels of protein.

| (2) |

Where:

R: ratio between normal and observed levels of protein; Cto: observed (measured) total concentration of drug (mol/L).

The unbound drug concentration can either be measured or determined based on the binding model and the total number of binding sites. This is an extra advantage of using normalized drug concentrations, since they can be calculated using either total or free drug concentrations. For drugs binding to a protein with a single binding site, equation 3 can be used.1

| (3) |

Where:

B: number of molecules of drug bound per molecule of protein; Cto: observed (measured) total concentration of drug (mol/L); Cf: free concentration of drug at equilibrium (mol/L); Cmo: observed (measured) total level of protein (mol/L); K: binding constant for binding of drug to a protein with a single binding site. Further details on practical applications and implications of these models can be found in the original research paper.1

Since in clinical practice the total drug concentration is considerably more monitored than the unbound drug concentration, the measured values of total concentration have been used thus far as the basis for the equations. The antiepileptic phenytoin exhibits a high level of PPB which can vastly change from patient to patient.1 Hence, it is generally recommended to individualize the dosage of phenytoin. The Winter-Tozer formula is one of the equations that is still broadly used to calculate the normalized phenytoin concentration (equation 4).11,12

| (4) |

Where:

0.1 is the normal fraction unbound (fu) of phenytoin and the binding protein is albumin; Ctn: normalized total concentration of drug (mol/L); Cto: observed (measured) total concentration of drug (mol/L); Cmo: observed (measured) total level of protein (mol/L); Cmn: normal total level of protein (mol/L). When using this formula, it is important to assess the kidney function of the patient as uremic toxins might displace phenytoin from albumin in severe renal dysfunction. The Winter-Tozer equation works only for phenytoin, presumes that the unbound fraction is concentration-independent, and overlooks nonlinear binding kinetics.11 On the other hand, equation 1 does not have any of these limitations.

Ter Heine et al. formulated a different equation for calculating the free drug fraction that is applicable in cases of nonlinear drug-protein binding (equation 5).11

| (5) |

Where:

Fu: free fraction; Cfree: free concentration; Ctotal: total concentration (mg/L); Bmax: maximum bound concentration (mg/L); KD: dissociation constant (mg/L).

If the unbound concentration is insignificant in comparison to KD, then the free fraction is independent of the unbound concentration. Additionally, if the free concentrations have a similar order of magnitude as KD, a positive association will ensue between the unbound concentration and the free fraction.11

In their model, Ter Heine et al. used the unbound drug concentration as the dependent variable which was predicted from the total drug and serum albumin concentrations.11 Clinically, the equations can be applied to calculate normalized drug concentration in patients with changes in their albumin and AGP levels. Such patients include the elderly, the pediatrics, and trauma patients. This clinical application of the equations would be of significant importance for drugs in the classes of antimicrobials, antiretrovirals, antiepileptics, and immunosuppressants.1

Hackbarth et al.13 argued that differences exist in the accuracy of calculated free testosterone when using the various proposed equations. The authors further advance that the calculations should consider gender and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) as factors influencing the results. The researchers suggested a new formula to accurately calculate unbound testosterone (fT) as a function of total testosterone, SHBG, and estimated or measured albumin (equation 6).13

| (6) |

Where:

ka is the association constant of testosterone binding to albumin (L/mol), ks is the association constant of testosterone binding to SHBG (L/mol), [SHBG] is the concentration of SHBG (mol/L), [alb] is the concentration of albumin (converted from g/L to mol/L using a molecular weight of 69,000 g/mol) and [TT] is the concentration of total testosterone (mol/L).

Special populations

Pediatric

At birth, hyperbilirubinemia is normal as the body increases production and decreases excretion of indirect bilirubin. In neonates, bilirubin displacement or high free fatty acids decreases albumin binding. As the baby ages, albumin levels rise and attain adult levels before the age of five months. Drug elimination in neonates and in adults differentiate on the basis of their physiological characteristics such as low glomerular filtration rate (GFR), large extracellular fluid volume, and liver function immaturity associated with greater occurrence of indirect hyperbilirubinemia. Hypoalbuminemia, as well as growth restriction and congenital cardiopathy also contribute to the differentiation in drug disposition between the two groups.

Hepatic extraction ratio (EH) is an intrinsic attribute of a drug. EH depends on the major physiological and biological components of the system. These components play a crucial role in the interindividual variability of clearance. The elimination of a drug depends on its binding affinity to a specific protein and the significance of the enzymatic pathway, which, in turn, is contingent to the ontogeny of PPB as well as enzyme concentration. Several studies have shown that age is an important factor in plasma protein levels. As an individual ages, investigators noted an increase in plasma proteins concentration and a decrease of unbound fractions of drugs in the blood. The EH is comprised of three age-dependent factors: fraction of unbound drug in blood (fu.B), hepatic intrinsic clearance of unbound drug (CLu.int,H), and hepatic blood flow (QH). It is predicted that age-related physiological changes in these parameters will result in variation in the EH of drugs as the person ages. Some of these changes can cause drugs, such as midazolam, to shift from high extraction to low extraction status. Thus, a high extraction drug may not be as such in neonates. Age dependent changes of the EH can be greatly affected by the ontogeny of plasma protein in the case of drugs that are highly bound and have low extraction.14

The fast changes in drug removal have been characterized as fundamental for pediatric drug dosing design. Conventional pediatric dosing approaches that solely rely on body weight or age do not fully take into consideration organ target and clearance maturation.15–17

Cefazolin is a first-generation cephalosporin that binds to HSA in plasma. Its free fraction in plasma varies widely among newborn infants, emphasizing the importance of monitoring the free concentration of cefazolin in pediatric patients.18 A study conducted by Smits et al. stated that the unbound cefazolin fraction was higher in neonates than the values reported in adults.17 They attributed the difference in unbound drug fraction to hypoalbuminemia, cefazolin total plasma concentration, indirect bilirubinemia, and postmenstrual age (PMA). Compared to older children and adults, neonates often present with lower albuminemia. The concept of drug protein binding saturability also applies to neonates. In this population, the maximum cefazolin protein binding capacity is attained sooner than in any other population. The association constant of bilirubin for albumin was reported to be 100 to 1000 times higher than for most drugs. Thus, this greater affinity for albumin results in bilirubin displacing bound cefazolin from plasma albumin and consequently there is an increase in the unbound cefazolin concentration as well as an increase in the indirect bilirubin level.19 Although distribution and clearance should be considered when proposing a dose adjustment in therapy, the higher cefazolin unbound fraction in neonates could warrant a lower dose to provide similar therapeutic effect as in adults.17 Vancomycin, in plasma, is bound to HSA and immunoglobulin A (IgA). Total drug concentration and albumin are important predictors of unbound vancomycin level in pediatrics. A second study by Smits et al. revealed that the median fraction of free drug reported in children and adults is lower than the values reported in neonates and young infants. However, despite this knowledge, the optimal vancomycin therapeutic dose target in neonates remains unknown. Dosing of vancomycin in this group is complicated by both a diminished renal tubular function and a lower overall GFR, which make their effect on drug protein binding difficult to predict.16

Dosing of pain medications in the pediatric population represents a unique challenge, especially when complicated by the management of high-risk opioids. Historically and currently, oxycodone has been the drug of choice in pediatric patients to manage their pain. The bolus intravenous formulation has been the standard route of administration for younger children though recently, oral formulations have been approved for children 11 years old and older. The PK in children is generally comparable to that in adults following an intravenous dose administration. Nonetheless, the drug clearance in neonates is slower while the clearance in older infants is slightly faster. This can be explained by the fact that the clearance process is systematically adjusted with the ontogeny of enzymes and organs. Accordingly, to reach similar drug exposure, oxycodone dosing should be based on protein binding, clearance, and the age stage with newborn receiving the lowest dose while toddler, preschool and school-age children getting higher dose compared with adults.15

These different studies suggest that a new approach of drug dosing design is warranted in the pediatric population; one that is not solely based on age and weight but incorporate other factors such as drug binding capacity, drug clearance and targeted organ maturity.

Elderly

From 2006 to 2016, the USA elderly population, age 65 and over, increased from 37.2 million to 49.2 million, a 33% increase. It is projected that it will double in number, reaching 98 million people by 2060.20 As the body ages, significant alterations in body composition occur. In advanced age, total body water decreases as body fat increases, the apparent volume of distribution (Vd) of polar drugs will decrease and that of non-polar drugs will increase. Other changes that can be noted in advanced age are a decrease in serum albumin concentration levels and an increase in AGP concentrations. In an article by Wallace et al.,21 the authors concluded that protein binding of vancomycin remained relatively constant in the elderly. However, these body changes are not normally credited to age per se, but instead to pathophysiological changes or disease states. Chronic diseases such as hypertension or chronic heart diseases can cause a decline in kidney function. This decrease in kidney function in turn can impair drug clearance which would necessitate some sort of dosage reduction.21,22

Furthermore, another study by Cooper et al. found that old age yields a small but statistically significant decrease in serum albumin in noninstitutionalized, seemingly healthy individuals. The decrease was approximately 4% per decade. The authors also noted that the decline in albumin level is not noticeable until people reach 70 years of age. The presence of undetected chronic disease in subjects 70 and older could also explain the fall in serum albumin. During an illness the liver produces acute-phase proteins instead of albumin, thus provoking a decrease in albumin levels. On younger subjects (<70) a statistical correlation could not be demonstrated. The authors concluded that any decrease in albumin level that is clinically relevant is certainly due to disease, acute or chronic. Hence, hypoalbuminemia is regarded as an indicator of disease as opposed to a normal aging occurrence.23

An article by Chin et al. stated that aging was linked to a decrease in clearance of drugs that are renally cleared as well as for drug that have flow-limited metabolism. This association is less apparent for drugs that have limited metabolization capacity, especially drugs with high protein binding, in which no steady alteration in total clearance has been established. Aging may cause an increase in unbound fraction (fu) which could offset a decrease in intrinsic clearance. The authors also noted that as people age, there was a decrease in plasma albumin concentrations; however, the change was minimal. The researchers also shown that the fu for both lorazepam and oxazepam rose with declining plasma albumin concentration levels. Still, the change remained small.24

The senior population, age 75 and older is the most susceptible group to acquire methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections, as well as hospital-acquired pneumonia.25 When infected, they are at high risk of developing severe hypoalbuminemia, defined as a serum albumin <2.5 g/dL, independently of their baseline nutritional state, which will result in increased free drug concentrations.26 The individuals in this population often present with significantly reduced renal clearance, decreased body fluid volume and large PK/PD parameter differences.25,26

Treatment of MRSA often include vancomycin, which is a known nephrotoxic drug. Therefore, patients with poor renal function who are treated with vancomycin are prone to have an elevated AUC and are at risk of higher mortality rate.25 Since vancomycin is mainly eliminated via the kidneys, it is uncertain if, in the elderly patients, targeting higher blood concentrations will result in an increased efficacy of the drug and/or increase the risk of nephrotoxicity.25 It is a well-known fact that vancomycin treatment outcome depends on specific patient characteristics. It is also well recognized that hypoalbuminemia can greatly influence treatment, leading to poor outcome.26 However, the correlation between changes in free drug concentration and vancomycin treatment outcome is still unknown.26

In patients with severe hypoalbuminemia, the fraction experiencing nephrotoxicity after vancomycin administration was significantly higher in the group with an area under the curve over the minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) values of >450 h. Comparatively, for patients with non-severe hypoalbuminemia, the fraction suffering from nephrotoxicity was considerably higher in the group with AUC/MIC values less than 250 h.26 Vancomycin guidelines recommend a target AUC/MIC for vancomycin of >400 h. However, according to the study by Mizokami et al, in the elderly, and initial empirical treatment for MRSA pneumonia, a range AUC/MIC of 250–450 h would be more suitable, until a vancomycin MIC is established.25 The difference between the guidelines and the findings of the study is not well understood. In the senior population with severe hypoalbuminemia, when free concentrations are higher, vancomycin has a longer half-life than in patients with non-severe hypoalbuminemia.26 This is in contrast with Benet’s paper claiming little clinical significance of changes in drug-protein binding.

Vancomycin dose should be adjusted based on the determined MIC. An alternative to vancomycin is recommended in elderly patients with poor renal function. Also, pharmacists should individually adjust vancomycin dosage in senior patients with low body weight and severe hypoalbuminemia,25,26 although unfortunately no clear quantitative guidelines are available.

Many factors can influence protein binding and age is one of them. Regrettably, the results of most of the studies do not agree on the degree that drug protein binding is affected by age. Elderly patients suffer from many disease states making an assessment based on age alone difficult. Although, what the studies do agree on is that the effect of changes in protein binding with age is determined by the extent of the alteration on the PK properties of the drug and on its therapeutic index. In the elderly population, only for a few drugs, such as naproxen, salicylate, and valproate does the free fraction undergo a 50% or more increase.21

Pregnancy

It is common knowledge that the plasma concentrations of some drugs can either increase or decrease during pregnancy. During the second trimester and throughout the remaining of the pregnancy, albumin concentrations undergo a steady decline. At the time of delivery, albumin concentrations are usually approximately 70–80% of normal values. There are only two types of highly protein-bound drugs that are predominantly hepatically eliminated for which changes in protein binding are clinically significant. First are the drugs with low extraction ratio. Total plasma concentration levels are used to monitor treatment efficacy. However, relying on total plasma concentrations will underestimate unbound, and therefore active drug plasma concentrations. Second are the high extraction ratio drugs with narrow therapeutic window that are not administered orally. During pregnancy, when albumin level is decreased, there is a significant increase in the AUC of unbound drugs, which can increase the pharmacological effect.27

Evidence suggests that an increased clearance and decreased concentrations of high extraction ratio drugs may be the results of both an increase in total liver blood flow and a decrease in protein binding. A change in drug clearance considerably affects steady-state concentrations of drugs and, as seen in observational studies, pregnancy also affects metabolic enzymes, of which the most common families are the cytochrome P450 (CYP) and uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT). As such, it increases the activity of CYP3A4, CYP2D6, CYP2C9 CYP2A6, UGT1A4 and UGT2B7 and decreases the activity of CYP1A2 and CYP2C19. To avoid a possible concentration-dependent toxicity during pregnancy, it may be prudent to decrease the dose of drugs that are primarily metabolized by these last two enzymes. In addition, a dose increase may be warranted for drugs predominantly affected by an increase in metabolic enzymes to prevent under-therapeutic effect.27

Anderson G.D. reports that GFR increased approximately 50% in the first trimester in healthy women studied during each trimester and 8–12 weeks post-delivery. The GFR continued to increase throughout the remaining of the pregnancy compared with postnatal values. The author also noted that drugs that are mainly renally excreted unchanged seem to necessitate a 20–65% dose adjustment all through the pregnancy to maintain pre-pregnancy drug concentration levels.27

During early pregnancy, prednisone is one of the medications that is the most commonly prescribed. Furthermore, prednisone and its active metabolite prednisolone, during pregnancy, have dose dependent pharmacokinetics. In plasma, they are highly bound to both corticosteroid binding globulin (CBG) and albumin. During gestation, CBG concentrations increase by 2–3-fold and albumin concentrations decrease by approximately 15%. The apparent oral clearance, the unbound apparent oral clearance, the apparent oral volume of distribution and the unbound fraction of prednisone increase as concentration rises. A plausible explanation for the increase in unbound fraction is a saturation of PPB at higher concentration levels. The percent bound of both prednisone and prednisolone rises as CBG concentrations increase. However, for pharmacokinetic reasons such as an absence of change in the apparent oral clearance of free prednisolone, dose adjustment of prednisone may not be required during prenatal period.28

In a study by Soldin, O.P.,29 the author demonstrated, using tandem mass spectrometry, a rise in free thyroxine (FT4) serum concentrations very early in pregnancy followed by a decrease in FT4 during the remaining of the pregnancy. These two parameters are important because they mirror the physiology of FT4 in gestation. Hypothyroidism during pregnancy presents a unique challenge to clinicians. Pregnancy brings metabolic changes and therapeutic targets that are not addressed in the dosing regimen designed for nonpregnant patients. The clearance of thyroid hormones is also modified as increasing volume of distribution and thyroxine (T4) requirements, which are associated with alterations in the metabolism of bound and free T4, continue all through pregnancy. The author noted that during the first trimester, T4 concentrations increased by approximately 45%. The concentrations remain at comparable level until delivery. Soldin, O.P. also made several other observations of changes that occur during pregnancy such as higher concentration levels of triiodothyronine (T3), slower mean oral clearance, longer mean serum half-life and a significantly higher AUC. Furthermore, the significant decrease in FT4 serum concentrations is the result of an increased number T4 binding sites. Thus, in pregnancy, levothyroxine dose adjustments are often required for women diagnosed with hypothyroidism. These women usually see an increase in their dosing regimens.29

The physiological and metabolic changes occurring during pregnancy and outlined by the articles authored by Anderson, G.D., Ryu et al and Soldin, O.P., suggest dosage adjustments are required especially for pregnant women with established hypothyroidism. However, even though prednisone and prednisolone exhibit dose dependent pharmacokinetics in pregnancy, a dose adjustment is not always necessary.

Obesity

Obesity, a well-identified global health problem, is defined as a body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2.30 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016, 13% of the global population aged 18 and over was obese.31 Likewise, in 2017–2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published data stating the age-adjusted prevalence of obesity in the U.S. adults was 42.4%.32

Obesity is no longer defined only in terms of demography. Other factors such as social, economic, behavioral, and genetic come into play, and they must be considered as they are involved in the rise in obesity. Epidemiological studies found a link between obesity and several health conditions notably hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, major depression, and certain types of cancer. Some of these health issues in obese individuals can be explain by reduced tissue perfusion and altered cardiac structure and function. However, more research is needed to fully understand the impact of obesity on PPB and the PK/PD of most drugs.30

The distribution and clearance of certain drugs seems to be altered in obese persons while absorption is not affected.30 Obese and non-obese people share similar tissue concentrations but differ in drug plasma concentrations and the volume of distribution (Vd) of lipophilic drugs. PPB is amid the processes that influences Vd, however, the impacts of obesity on PPB is unclear as current data implies that in this subgroup population, variations in Vd are drug-specific and are credited to pharmacologic attributes of a particular drug.33 The passage of drugs into tissue compartments can be influenced by alterations in the concentrations of PPB and consequently affect their therapeutic effect.34 The balance between a drug’s affinity for plasma proteins and tissue compartments will dictate the amount of a drug in the plasma, although, in a clinical setting, tissue binding cannot be directly measured as it is the case for plasma binding.34 On one hand, in an article by Smit et al.,35 the authors reported no difference in albumin and total protein concentrations in obese and non-obese individuals; on the other hand, Cheymol et al.34 described a slightly higher concentration of AGP in obese people due enhanced secretion. Nonetheless, relevant PK changes have yet to be derived from this finding. Therefore, drug binding to albumin is not impacted by obesity while drug binding to AGP has shown conflicting results.30,35

Smit et al. compiled studies describing the impact of certain drugs on Vd and clearance in obese and non-obese subjects in relation to protein binding. Drugs such as alprazolam, cefazolin, daptomycin, lorazepam, midazolam, oxazepam, propranolol and triazolam were studied. The studies did not reveal a change in unbound concentrations of these drugs in morbidly obese patients. Furthermore, unaltered serum albumin concentrations for the same group were also reported in the daptomycin study. However, reduced albumin concentrations were observed in the propranolol study while the AGP serum concentrations remained unchanged. The results of the latter study may seem contradictory to previous findings, but propranolol is mainly bound to AGP, which is in line with the results. Obese children who were given clindamycin exhibited a decrease in Vd when AGP and albumin serum concentrations were increased. Unfortunately, the authors of the clindamycin study did not measure the drug unbound concentrations; therefore, it is unclear if free concentrations were affected.35

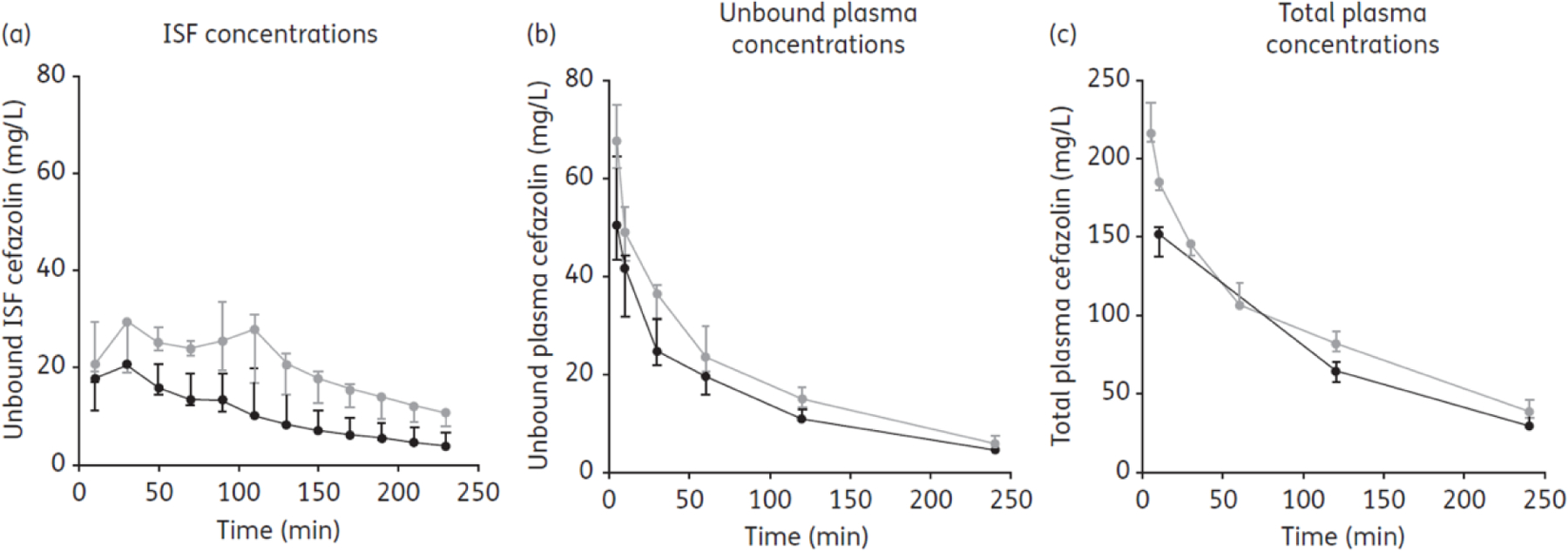

Brill et al.36 conducted their research on subcutaneous tissue distribution of cefazolin. This drug is considered the prophylactic antibiotic of choice for postoperative surgical site infection. Obesity is an additional risk factor for infection following surgery as the antibiotic must distribute in the interstitial space fluid (ISF) of the subcutaneous adipose tissue to produce an effect. Cefazolin is highly bound to proteins and to be effective in the ISF, the unbound drug concentration needs to be above the MIC of the target microbes.36 Figure 4 shows the median and interquartile range (IQR) of observed cefazolin concentrations for morbidly obese and non-obese patients. The authors report a lower subcutaneous adipose tissue penetration of the drug in morbidly obese individuals which can be explained by a lower blood flow in the tissue and a larger volume of distribution. Therefore, the authors suggest ISF tissue concentrations as the PK/PD index in lieu of the unbound plasma concentration as the marker for cefazolin efficacy in morbidly obese patients.36 Extrapolating from this study, it can be concluded that since there is a decrease in drug tissue distribution with an increase in body weight, an increase in cefazolin dosing is required in obese patients.

Fig. 4.

Observed cefazolin concentrations in morbidly obese patients. The area under the time–unbound concentration curve (fAUC0–4h) for subcutaneous ISF was significantly lower in morbidly obese patients (n = 7) in comparison with non-obese patients (n = 7), P < 0.05. In contrast, the fAUC0–4h for unbound plasma cefazolin concentrations did not differ significantly between the patient populations (P > 0.05). The observed unbound cefazolin ISF penetration ratio, expressed as fAUCtissue/fAUCplasma, was 0.70 (range 0.68–0.83) in morbidly obese patients as opposed to 1.02 (range 0.85–1.41) in non-obese patients (P < 0.05). Morbidly obese: black symbols and line. Non-obese: grey symbols and line. ISF: interstitial space fluid.37 Reproduced with permission from [37].

An article by May et al.37 the authors came to this conclusion when dose adjustment is warranted in the obese population: obese patients required various models of dose adjustment, contingent to the drug being lipophilic or hydrophilic. For hydrophilic drugs, the fat-free or lean body mass calculator is recommended and as for lipophilic compounds, the total body weight is suggested to calculate the individual therapeutic dose. However, the authors stated this conclusion only pertains to drugs used to treat chronic illnesses.37 Limited information on the impact of obesity on protein binding is available as only a few research articles published drug unbound concentrations. Considering the lack of strong evidence in the adequate therapeutic dosage in obese patients, May et al. suggest adopting, as a general guide, total body weight for highly lipophilic drug dose calculation in short term treatments and lean body mass for hydrophilic molecules or for chronic treatment. That is, until more vigorous data become available.37

Disease states

Critically ill patients

In this section, the PK of the critically ill patients, the malnourished patients, and the thermal burn injury patients will be discussed in relation to drug protein binding.

Critically ill patients are any individuals in the intensive care unit (ICU) who require urgent medical or surgical treatment.38 Quality of care in critically ill patients is dependent on adequate drug therapy. In these patients, plasma protein concentration levels can be influenced by their concurrent disease states. Acute stress or trauma can trigger, on the one hand, a decrease in albumin concentration because of a rise in vasculature permeability and breakdown of proteins. The same conditions also trigger an increase in AGP concentrations.39

The free drug concentration will be increased in patients with hypoalbuminemia for drugs that are highly protein bound. Even if the total drug level does not change, this increase in free drug level will lead to an increase in pharmacological effects. For example, valproic acid concentrations increase six- to seven-fold in patients in the ICU compared to healthy people as the antiepileptic drug class is categorized as highly bound to albumin. However, drugs bound to AGP will have decreased pharmacological effects, as AGP increases in patients in the ICU. As an example, the Vd and CL of morphine decreased by at least 40% and >60% respectively. Unbound drug concentrations are greater in critical illness as drugs used in treatment compete for protein-binding sites. Drugs are classified as having either high or low extraction ratios. Only the drugs in the first category exhibit clinically relevant consequences after alterations to PPB. Protein-binding changes are not likely to result in clinically significant variations in hepatic clearance for drugs with low extraction ratios.39

There is a possibility that the GRF in critically ill patients exceeds the normal values, between 120 to 130 mL/min/1.73 m2, defined in healthy individuals. This implies that the clearance of renally eliminated drugs can increase. Additionally, renal blood flow and renal drug clearance may be increased in conditions like sepsis, trauma, surgery, and burns. Patients with augmented renal clearance might benefit from an increase in total daily dose to maintain the same therapeutic effects as in patients with normal elimination.39

Morbidity and mortality rates amid critically ill patients are persistently high due to infections contracted while in the ICU. In these patients, adequate antibiotic therapy is complicated by their multifaceted disease processes, resulting in subtherapeutic or toxic concentrations if standard dosing is administered. Beta-lactam antibiotic variations in protein binding and therefore possible adverse effects are common, as approximately 40% of critically ill patients experience hypoalbuminemia.40

A study conducted by Wong et al. revealed that in patients with critically illnesses, PPB of beta-lactams varies greatly. Only for certain agents does a correlation exist with albumin concentration. From the same study, the authors did not find a significant association between the unbound fraction of ceftriaxone and albumin concentration levels. However, one was found between free flucloxacillin and albumin concentration.40

Sharma et al38 define malnutrition as an acute, subacute, or chronic state of nutrition in which varying degrees of overnutrition or undernutrition, with or without inflammatory state, have led to a change in body composition and diminished function. Malnutrition in the critically ill may negatively affect the recovery of patients as it leads to reduced function, modification in body composition and is linked to worsening outcomes. Malnutrition can also be responsible for increasing the threat of complications and the patient being readmitted to the hospital. In critically ill individuals, patients suffering from malnutrition range from 38% to 78%.38

In the catabolic stress stage of critical illness, protein is the primary source of energy. The breakdown of amino acid sources in skeletal muscle, connective tissue, and gastrointestinal tract forms proteins that are utilized for energy or other metabolic activities. The loss of lean body mass resulting from net protein catabolism can add to organ dysfunction and poor health outcome. Critically ill patients are known to be protein deficient; however, how much protein is needed remains unclear.38

Enteral nutrition (EN) and parenteral nutrition (PN) may result in changes in drug-protein binding. When compared with PN, early administration of EN was found to decrease infectious complications and reduce the length of stay in the ICU. However, for numerous reasons, EN may be contraindicated, not well tolerated or inadequate in some patients. When EN is poorly tolerated, PN can serve as a substitute to optimize energy needs. In this scenario, PN is associated with better outcomes and lesser hospital acquired infections. In practice, it is important to avoid lengthy starvation and initiating PN too early during patient care as both can be harmful to the patient. Therefore, initiation of PN, in terms of time and indication should be carefully considered.38

In the acute and convalescent phase following burn or traumatic injury, variations in the quantity of proteins and the ability of drugs to bind to those proteins can be remarkably altered.41 The PK of burn victims varies from patient to patient. Fluid replacement, fluid shifts between body compartments and surgery impact the PK of patients with critical illnesses. These changes are unpredictable, increasing the need for individualized drug dose adjustments.42

Burn wound infections and bacteremia are risks linked with thermal burn injury patients. These infections are mostly caused by gram-positive organisms. A study by Mohr et al. on the PK of daptomycin in patients with thermal burn injury showed a lowering in the AUC and an increase of the Vd and total CL of daptomycin. They also suffer from loss of protein across their burn wounds. Daptomycin is highly protein bound. Throughout the early postburn stage, the loss of protein in the wounds may cause the bound drug to be eliminated faster. To achieve therapeutic effect, the daptomycin dose should be increased for burn patients.42,43

Transplant patients

The statistics of the Health Resources and Services Administration,44 a U.S. government information site on organ donation and transplantation, show that 39,718 transplants were performed in 2019. The most common solid organs transplanted were the kidney (23,401) followed by the liver (8,896) and the heart (3,552).

Transplant patients must be maintained on long term therapeutic regimens such as immunosuppressives, antihypertensives, antibiotics, antifungal45 and antiviral agents, and other drugs, which render drug therapy optimization very challenging.46 After transplantation, in addition to an increase in AGP plasma concentration, the physiological functions of the transplanted organ go through noticeable alterations. Drug absorption and disposition are PK processes that are directly or indirectly implicated in each of the three primarily transplanted organs, i.e., kidney, liver, and heart. Following transplantation, drug absorption, distribution, and elimination can experience a time-dependent transition going from the state of organ failure to that of normal function. If the transplantation is successful, drug absorption in transplant and healthy patients will be comparable. Several biochemical markers also go through time-dependent modifications. These markers include serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, serum bilirubin and liver enzymes. Furthermore, since these biochemical markers cannot accurately represent the function of the organs during the postoperative period, they cannot be considered during drug dosing adjustment.46

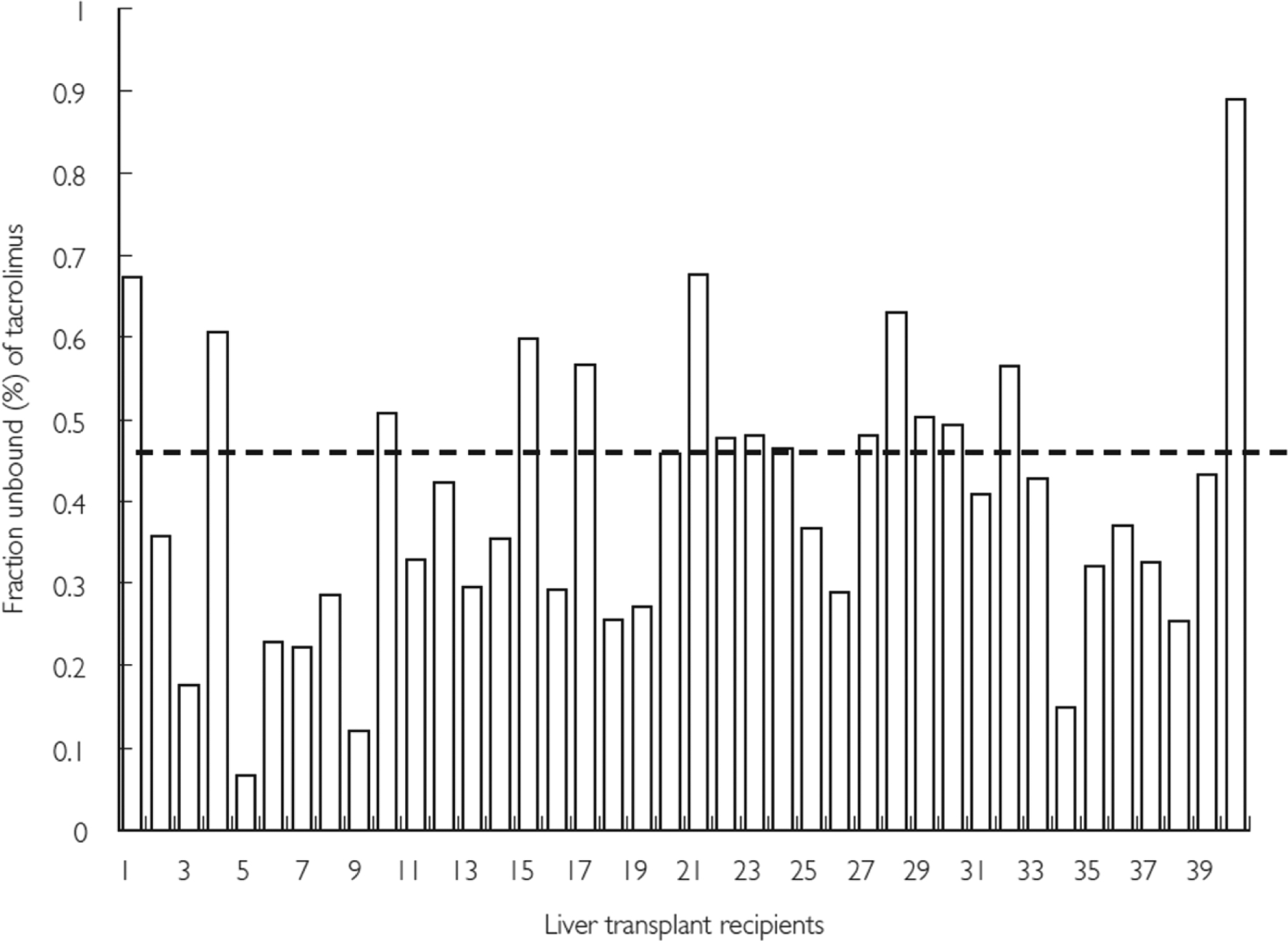

A study by Zahir et al.47 on the variability of distribution of tacrolimus in liver transplant led to several observations. A rise in hematocrit and erythrocyte triggers an increase in the percentage of tacrolimus linked with the red blood cell (RBC) fraction in blood. Similarly, a surge in lymphocyte count also correlates with an increase in the percentage of tacrolimus. Apart from albumin concentration, lipoprotein deficient serum (LPDS), total protein concentration and AGP are all associated with an increase in the percentage of tacrolimus. Similar trends exist with an increase in both LPDS, total protein concentration, AGP, and total cholesterol concentration. Tacrolimus is highly bound to plasma proteins. Its unbound portion in plasma typically ranges between 0.3–2% and relates to AGP and HDL-cholesterol concentrations. Figure 5 shows the large variability in tacrolimus plasma protein binding, which warrants individualized dosing adjustments. The unbound fraction has a 15-fold variation among liver transplant recipients. Additionally, male recipients tend to exhibit considerably greater unbound fraction than female recipients.47,48

Fig. 5.

Variability in in vitro plasma protein binding of tacrolimus in individual liver transplant recipients. In liver transplant recipients the unbound fraction of radiolabeled tacrolimus in plasma was found to be 0.47 ± 0.18% and there was a 15-fold variation (range 0.07–0.89%) in the fraction unbound (%) of tacrolimus in these patients. A significantly higher fraction unbound was observed in male recipients (n = 23) compared with female recipients (n = 17) (0.5 ± 0.1% vs 0.4 ± 0.1%; P = 0.003, Student’s t-test). Dashed line indicates average fraction unbound in total cohort (0.47 ± 0.18%).48 Reproduced with permission from [48].

From these observations, the authors concluded that for healthy and transplant subjects, the primary reservoir for tacrolimus is the RBC; however, in the transplant recipients there is a wide variation in the fraction of total drug linked to these cells. The percent of tacrolimus associated with RBC increases with the rise in erythrocytes and hematocrit as tacrolimus has concentration-dependent nonlinear binding to RBC. Albumin and AGP predominantly constitute the LPDS fraction and are associated to tacrolimus. In the initial post-transplant period, changes in these proteins may account for the differences in free tacrolimus concentration. Furthermore, the portion of tacrolimus contained in lipoprotein fractions may be influenced by the variability in lipoprotein concentrations. This can affect drug dosages and clinical outcomes because of the potential change in free drug fraction. A decrease in AGP follows the early post-transplant period but depending on the amount of time passed after the transplantation, lipoprotein concentrations can also differ.47

An article by Sikma et al.48 on the PK and toxicity of tacrolimus in heart and lung transplant patients reveals that following the transplantation, recipients experience frequent significant clinical changes which in turn result in variations in free plasma tacrolimus concentrations. Excess unbound drug can lead to tacrolimus toxicity and damage to the kidneys.48

Furthermore, albumin, lipoprotein, and AGP concentrations are regularly altered after transplantation, thus contributing to the variation of tacrolimus blood distribution. Both liver and renal failure cause hypoalbuminemia; there is a reduction in the proteins produced by the liver and loss of protein by the kidney. As for lipoprotein concentrations, due to increased breakdown and decreased synthesis in the postoperative period, levels diminish quickly and may fall to as low as 50% of normal. The drop in HDL concentrations rises the free plasma concentration of tacrolimus as HDL is the main binding site of the drug. AGP concentrations tend to behave the opposite way. In the acute phase when there is inflammation the protein level increases resulting in a decrease in unbound drug.48

Following transplantation, even though the blood composition of the recipient is altered, the total blood protein concentration may not be affected. In disease states such as anemia and hypoalbuminemia, the clearance of tacrolimus in the liver was found to be greater due to an enhancement of the uptake of the drug into the liver.48

Renal failure and chronic kidney disease

The PPB of drugs is typically decreased in cases of renal failure. Additionally, the fraction of drug excreted can be unaffected, or it can increase in individuals with chronic renal failure. Furthermore, in patients with uremia, drugs that are acidic show a decrease in PPB as opposed to basic drugs for which binding remains unchanged or decreases.49 Montgomery et al. reported that when compared with people with normal kidney function, there was no change in protein binding in patients suffering from mild and moderate kidney disease but adequate albumin concentrations.50

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end stage kidney disease (ESKD) could present with changes in PK processes including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. These alterations make optimization of antibiotic dosing very difficult as these individuals are at greater risks of side effects. Moreover, patients on an antibiotic regimen and on dialysis are further exposed, especially during off-dialysis sessions. Dialyzed patients have their system cleared of the antibiotics on dialysis days however, the drugs accumulate in their body with little or no clearance during the two to three days following dialysis.51

For patients with kidney disease and on beta-lactam antibiotics, if a dose adjustment is needed, decreasing the dose while keeping the dosing interval is preferable as this class of antibiotic exhibit time-dependent activity. Because of the beta-lactam prolonged half-life in patients with CKD, PD target achievement is more attainable due to the lengthier time above the MIC. Penicillins are usually well tolerated in these patients, but the increase in kidney secretion of penicillins may complicate dosing.51

Vancomycin clearance was found to be increased in dialyzed patients using high-flux dialysis filters. To attain pre-dialysis trough concentrations in patients getting vancomycin in the final hour of dialysis, increased maintenance doses would be required. Daptomycin is 86% protein bound in dialysis patients and it has a low volume of distribution. A 50% increase in the daptomycin dose has been suggested in the three-day intradialytic period to reach AUC:MIC targets. However, greater risks of skeletal muscle toxicity have been linked with higher drug exposure. For linezolid, a dose adjustment is not recommended since only 30% of the drug is removed during dialysis.51

In the elderly with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), there is a high risk for CKD. Sodium glucose cotransporters type 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are one of the drug classes used to treat T2DM. This class of drugs works by increasing urine excretion of glucose. The Cmax of dapagliflozin elevates as the kidney function slowly declines since the drug is not significantly excreted renally. Therefore, in patients with CKD, total exposure is greater. Transient creatinine changes and minor increases in renal adverse events are linked with dapagliflozin. Compared to subjects with healthy renal function, the AUC and Cmax of canagliflozin is unchanged in patients with ESKD; however, they marginally and modestly increase with mild and moderate to severe CKD, respectively. Canagliflozin is insignificantly removed via dialysis. When CKD increases in severity, the PD response to the drug lowers. Empagliflozin, a third drug in the SGLT2 inhibitor class, exhibits plasma concentrations that change in individuals with CKD. The AUC values of empagliflozin are expanded in patients with various degrees of CKD and ESKD. This increase is associated with a decrease in renal clearance. In patients with CKD, dose adjustment of empagliflozin is typically not needed because the rise in drug exposure is limited.52

Because SGLT2 inhibitors are minimally cleared renally, PK parameters and drug exposure are only slightly affected in renal disease. In patients with moderate CKD, a reduction in the daily dose of dapagliflozin and empagliflozin is not recommended although it is recommended to reduce the maximum dose for canagliflozin. These recommendations are based on observed alterations in systemic exposure.52

Liver diseases

Changes related to the liver may differ widely from person to person. The metabolism and elimination of many drugs are some of the functions that the liver is implicated in. It is also involved in the synthesis of several key proteins that affect the way the body handles the drugs.53

In a 2018 report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)54 stated that 4.5 million of adults living in the United States have had a diagnosis of liver disease, which represents 1.8% of the American adult population.

The most common types of diseases of the liver are alcohol-related liver disease, cirrhosis, hepatitis C, liver cancer and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

People possess a substantial liver reserve, especially where drug metabolism is affected. Consequently, patients with liver disease may not require a drug dose adjustment until the disease becomes severe. Furthermore, individuals with liver disease may experience increased exposure of many drugs due to decreased PPB, lowered first-pass and other metabolism and reduced elimination. Thus, drugs with narrow therapeutic index need the most consideration when instituting dosages for individuals with severe liver disease. Several drugs are contraindicated or come with a warning in these patients. Starting and maintenance doses adjustment may be required to prevent dose-dependent adverse effects. As such, both initial and maintenance doses need a reduction in doses for drug taken orally that are high hepatic extraction. Whereas only the maintenance dose may be adjusted for drugs with low hepatic extraction. Some examples of drugs that are high hepatic extraction are morphine, midazolam, and metoprolol. Drugs that are low hepatic extraction are paracetamol, doxycycline, and alprazolam. The elimination of high hepatic extraction drugs that are administered orally is slow down in people with liver cirrhosis. This leads to a clinically significant rise in these patients’ maximal plasma concentration levels and bioavailability. To a lesser extent, elimination is also decreased for drug with low hepatic extraction.53

Liver disease is an inherent factor that may impact the absorption, disposition, metabolism, and elimination of anticancer drugs that are administered orally. Cabozantinib is an oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor (RTKs). It is extremely protein bound in plasma and is a cytochrome P450 3A (CYP3A) substrate. And since the hepatobiliary pathway seems to be the major path of elimination for cabozatinib and its metabolites, liver dysfunction is speculated to increase the plasma concentrations of the drug due to lower PPB. A study by Nguyen et al.55 reveals that subject with moderately impaired hepatic function had higher drug unbound fraction compared to mildly impaired or normal individuals. The authors noted a 29% decrease in cabozantinib Cmax in the moderate-hepatic-impairment cohort and thought it may be associated with lower serum albumin levels. Furthermore, lower serum albumin concentrations were observed in patients with lower drug plasma Cmax values. Hence, a reduction in albumin levels may potentially increase cabozantinib free drug fraction, heighten total drug clearance and decrease total plasma exposure of the drug. However, the authors do not recommend a lower starting dose of cabozantinib for individuals with mild or moderate hepatic impairment.55

Plasmapheresis

Plasmapheresis can be performed by treating and returning the patient’s own plasma (autologous plasmapheresis), or by replacing plasma with blood products (plasma exchange, PE). PE mainly treats systemic maladies such as autoimmune diseases. PE works by removing endogenous and xenobiotic molecules. The amount of free drug flowing in the body will dictate how efficacious the procedure will be in terms of drug elimination as PE can remove between 0.5–30% of the dose administered to the patient. The two essential factors influencing drug removal by PE are Vd and PPB: the higher the drug PPB and the lower its Vd, the more successful the procedure. For low Vd drugs, a large fraction of the drug stays in the central compartment and PE withdraws a significant volume of plasma, effectively removing drugs with high PPB.56

PE greatly affects the PK of ceftriaxone since >10% of the dose is eliminated by the exchange, as ceftriaxone is highly bound to albumin and has a low Vd. Based on these findings, it would be appropriate to administer the ceftriaxone dose once the procedure is over. Antiviral drugs are typically not significantly affected by PE; their PPB level is less than 25% and their Vd greatly fluctuates. For drugs that are considerably affected by the PE procedure (high PPB), one of these three dose adjustments are recommended: administer a loading dose before the PE session, give a dose equivalent to the amount lost after the procedure, or arrange for the dose to be given after the exchange. If the drug is administered by continuous infusion, it is suggested to increase the drug flow to compensate for the rise in clearance by PE.56

Autologous plasmapheresis is used in a variety of disorders to extricate harmful antibodies from circulation. However, it can also remove therapeutic antibodies. It is imperative to evaluate the effect of the procedure on the PK of rituximab as every one of the solutes in the plasma can be eliminated. Puisset et al. demonstrated that rituximab had a 261-fold increase in clearance by plasmapheresis.57 If the procedure is done within 72-hour of the first infusion of rituximab, approximately 50% of the drug will be removed; therefore, this increased drug elimination should be considered in selecting the number of infusions to schedule. The standard of care calls for two consecutive weekly infusions. The authors recommend an extra infusion to compensate for the loss of the drug due to plasmapheresis.57

Epilepsy

In 2015, about 3.4 million of Americans had active epilepsy, which is about 1.2% of the population.58 Epilepsy is not a single disease but a heterogeneous condition with various causes of many seizure types. The condition is usually well controlled with medication but some patients need frequent dosing adjustments, some of which are related to changes in PPB.58

Valproic acid as a broad-spectrum antiepileptic is also effective in patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Furthermore, it is approved as a migraine prophylaxis agent. The valproic acid blood concentration varies considerably from patient to patient as it exhibits high and saturable protein binding. To illustrate its fluctuating free blood levels, at a total concentration of 50 mg/L 93% of valproic acid is bound to albumin; however, PPB decreases to 70% at a total concentration of 150 mg/L.59 Because of a steady-state ratio of about 10% between the free and total concentrations of valproic acid, in most case, it is acceptable to measure its total concentrations. However, even if the total concentration of valproic acid is within therapeutic range, some patients may experience drug toxicity because of an increased free concentration.59

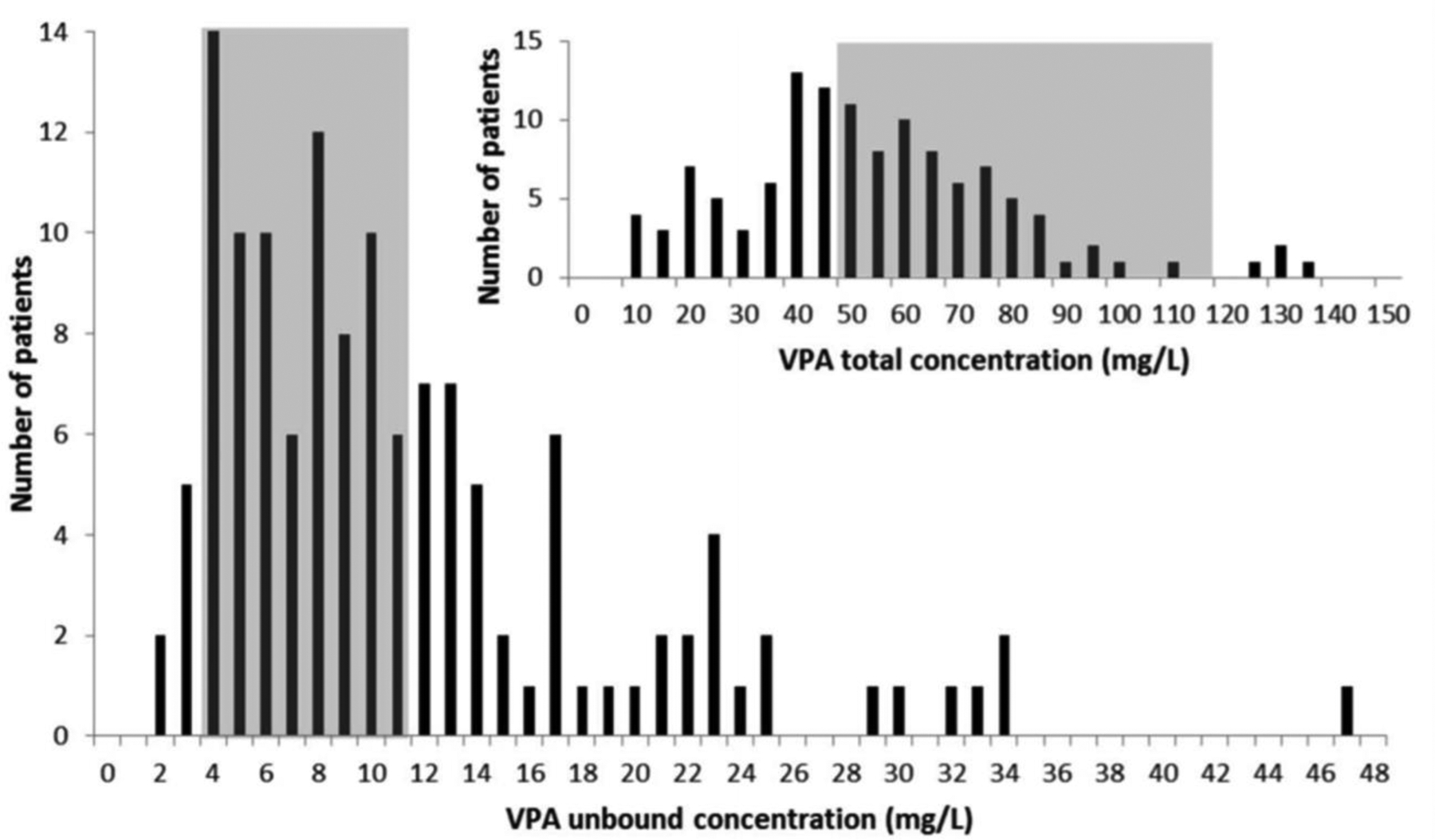

A study by Wallenburg et al.,59 depicted in figure 6, demonstrated that even though only 5% of the subjects had valproic acid total concentrations above the therapeutic range, 37% of the patients experienced elevated unbound drug concentrations. There is a weak correlation between the efficacity of valproic acid and its total plasma concentration; however, there is a good relationship between valproic acid concentrations and the incidence of side effects. Increased unbound drug concentrations are linked with low albumin levels. Neurological adverse effects correlate with free valproic acid rather than total concentrations. However, the unbound therapeutic range of valproic acid remains unknown,59,60 making it difficult to create a model for adjusting dosing regimens.

Fig. 6.

Valproic acid (VPA) unbound concentrations versus total concentrations (small graph). Total VPA concentrations were measured in 121 patients, with a median concentration of 52 mg/L (11–139 mg/L). Six of these 121 patients (5.0%) had elevated total VPA concentrations (i.e., 100 mg/L). This is in contrast with the 37% of patients who had elevated unbound VPA concentrations. The median-free fraction was 19.3% (8.4%–81.7%). VPA: valproic acid.60 Reproduced with permission from [60].

A different study by Doré et al. found that the higher tissue penetration of valproic acid was associated with an increase in Vd of free valproic acid in individuals with low albumin. The unbound drug primarily distributes in the central nervous system (CNS) and the patient may experience adverse neurological symptoms such as drowsiness, lethargy, and confusion. As the drug serum concentration rises, the clearance of free valproic acid declines. Therefore, in selected patients on valproic acid therapy, it is important to measure the unbound drug concentration.59,60

Phenytoin, like valproic acid, has multiple therapeutic indications: focal onset and generalized tonic-clonic seizures, status epilepticus, and prevention of seizures after traumatic brain injury or neurosurgery. Phenytoin has high binding to albumin and a narrow therapeutic window, with only approximately 10% of the drug available for pharmacological activities. In patients with traumatic brain injury, alterations in phenytoin protein binding and metabolism influence free and total concentrations. These changes cause total concentrations of the drug to misrepresent the more relevant free concentrations.50 Accordingly, unbound phenytoin concentrations should be used to adjust dosing regimens in critically ill patients.

A study by Montgomery et al. concluded that in individuals with normal albumin concentrations, total phenytoin concentrations tend to mirror free concentrations. Thus, estimating or measuring unbound drug concentration is superfluous for patients with normal serum protein levels. For people with estimated unbound phenytoin levels, a dosage adjustment will depend on signs of toxicity and seizure control.50

Conclusion

This paper examined general approaches for estimating unbound drug concentrations, assessed factors influencing drug protein binding, and discussed whether a drug dose adjustment is required to compensate for changes in protein binding in special patient populations and in certain disease states.

The original Winter-Tozer equation was one of the first to calculate free drug concentrations. However, this equation is limited to linear binding range as opposed to the newer proposed formula that can be used to calculate normalized concentrations for drugs binding to several proteins. In the pediatric population, a drug dose adjustment based on the albumin concentration level is recommended for cefazolin, vancomycin, and oxycodone because the free drug concentrations are higher in this population than in adults. In the elderly population, the dose of vancomycin should be adjusted according to the renal function if patients are diagnosed with hypoalbuminemia. Prednisone dose adjustment during pregnancy may not be necessary even though the albumin concentration decreases in pregnancy. The same recommendation cannot be made for pregnant women with hypothyroidism, since levothyroxine necessitates a dose adjustment. For obese patients, cefazolin does require a dose adjustment for greater drug tissue penetration.

In critically ill patients, drugs with high extraction ratio typically require a dose adjustment regardless of their PPB level. Enteral and parenteral nutrition should be adjusted in response to protein needs. In the critically ill with thermal burn injury, an increase in the dose of daptomycin is recommended. A dose adjustment of tacrolimus in transplant patients is recommended. In patients with kidney dysfunction, it is recommended to adjust the dose of penicillins. Likewise, dose adjustment of vancomycin and daptomycin for patients on dialysis is required, but it is not needed for linezolid. For patients with moderate kidney dysfunction, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin do not require dose adjustment. Canagliflozin does require a dose adjustment. For patients going through plasma exchange procedure, a supplementary ceftriaxone dose is recommended after the exchange. But antiviral drugs do not require any dose adjustment. Patients on rituximab need a dose adjustment when going through plasmapheresis. Valproic acid doses are adjusted based on toxicity and the control of seizures, while the dosing of phenytoin should be changed based on albumin levels.

Since over 40% of the United States adult population is obese and the trend is going upward, more research is needed in how to adequately treat this subgroup of the population in which the protein and lipid levels are unusual. However, evidence-based research on drug protein binding and its effect on dose adjustment in the obese population is rarely studied. The obese and morbidly obese groups are often not represented in clinical trials and therefore, little information is known about the PK and therapeutic dose of many of the medications used in the treatment of these patients.

As pharmacology is heading more and more toward individualized medicine and treatment, researchers, physicians, academicians, and clinicians need a thorough understanding of drug protein binding and how protein levels differ with body types and health conditions; how to effectively dose medications, especially for treatment of chronic diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the US National Institutes of Health (1R15GM126510). The authors’ work was independent of the funders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declarations of interest

- none

References

- 1.Musteata FM 2012. Calculation of Normalized Drug Concentrations in the Presence of Altered Plasma Protein Binding. Clin Pharmacokinet 51(1):55–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith DA, Di L, Kerns EH 2010. The effect of plasma protein binding on in vivo efficacy: misconceptions in drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov 9(12):929–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohnert T, Gan LS 2013. Plasma Protein Binding: From Discovery to Development. J Pharm Sci 102(9):2953–2994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts JA, Pea F, Lipman J 2013. The Clinical Relevance of Plasma Protein Binding Changes. Clin Pharmacokinet 52(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]